Abstract

Since 2018, US foreign policy elites have portrayed China as the gravest threat to their country. Why was China predominantly cast as an ideological threat, even though other discursive formulations, such as a geopolitical threat, were plausible and available? Existing major IR theories on threat perpcetions struggle to address these questions. In this article, we draw from rhetoric and public legitimation scholarship to argue that the mobilization of adjacent policy debates was key to mainstream the representation of China as an ideological threat. By mobilizing debates on Russia and the soft power and sharp power concepts, a minority view in US foreign policy with a longstanding ambition to get tough on China established a seemingly natural link between liberal internationalism and an ideologically threatening China. Liberal foreign policy elites who originally opposed a realpolitik view of China could now subsume a geopolitical threat into an ideological one reminiscent of US-Soviet Cold War rivalry. This constituted a necessary catalyst to align most foreign policy elites to understand China as the gravest threat to the United States, at a time when China’s capabilities and behaviour, coupled with a deep sense of insecurity regarding America’s place in the world, provided the necessary backdrop.

Keywords: Discourse, Geopolitics, Ideology, Rhetoric, Threat, US-Chinese relations, Soft power, Sharp power, Russia

Introduction

For the last thirty years, the rise of China and its implications for global order, peace and prosperity has attracted much commentary. While there have always been voices in the United States and elsewhere who have predicted conflict with China, most commentators have been cautiously optimistic that as long as its rise is carefully managed, China can be peacefully integrated as a great power into the existing world order. Since around 2018, however, we have witnessed the emergence of an unprecedented consensus among US foreign policy elites that China’s peaceful rise is no longer possible, and that the country instead poses the most serious threat to the national security of the United States (see e.g. The White House 2017; McCourt 2022; Blinken 2022).

One feature stands out in this discourse: the notion that China constitutes not merely a military, political or economic threat, but also an ideological threat to Western liberal democracies and global order.1 On numerous occasions, observers have noted how China2 ‘infiltrates’, ‘disunites’ and ‘infects’ the political and societal structures of democracies. For instance, in testimony before the US Congress in early 2018, Ely Ratner – since then appointed as Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs – argued that ‘the Chinese Communist Party [CCP] is succeeding in undermining basic democratic values in the United States’ (Ratner 2018). Former Secretary of State Michael Pompeo likewise suggested that ‘Communist China’ threatens ‘the future of free democracies around the world’ (Pompeo 2020, for other instances, see Brady 2017; FBI 2022). By now, commentators often characterise China’s relations with the West and especially with the United States as a clash between two incompatible ideological systems: a ‘new Cold War’ (Layne 2020; ‘Anonymous’ 2021).

The sudden and widespread acceptance of depicting China as constituting chiefly an ideological threat to US national security is surprising. First, although the Chinese government has undoubtedly become more assertive internationally, there is little concrete evidence that it launched an explicit and comprehensive campaign to shape the world or America in its own image (Weiss 2021; Zhao 2022, p. 3). Second, many aspects of China’s international behaviour have been re-evaluated as ideologically driven, even though such behaviour has in the past neither been considered ideological (or particularly threatening), such as for instance its pursuit of soft power. Finally, the dominant representation of China as an ideological threat is striking given that other discursive formulations—such as a geopolitical or economic threat—are equally plausible, and have been common among sceptics of China’s intentions and a ‘peaceful’ rise (e.g., Grygiel and Mitchell 2017; Ebbighausen 2020; Yan 2020; Allison 2017).

Our aim in this article is to investigate how, why and with what consequence US foreign policy elites have embraced the depiction of China as an ideological threat. Major International Relations (IR) theories might either point to China’s growing material power, assertiveness abroad and repression at home, or shifts in political culture and identity formulations, to explain the emergence of a new consensus that China constitutes the most dangerous threat to US security (e.g. in the tradition of Mearsheimer 2001; Walt 1985; Turner 2014; Pan 2012). Yet, we argue that such existing theories on ‘threats’ or the ‘China threat’ do not pay sufficient attention to the specific form that threat representations can take, and are therefore unable to explain why the representation of China as an ideological threat became the dominant feature of the China threat discourse, and how this was successful in persuading US foreign policy elites of the severity of the general threat China poses to US security.

To explain why, how and with what consequence the ideological China threat narrative was able to win out over other plausible representations of the China threat, this article draws on literature on foreign policy change and public legitimation. This literature allows us to examine the conditions and processes through which threat representations become persuasive and dominant (e.g. Goddard and Krebs 2015; Jackson 2006; Krebs and Jackson 2007: Dueck 2008).

Based on an analysis of media and think tank reports, academic work and interviews in the United States, we find that the successful mobilisation of rhetoric resources from adjacent policy debates was key to mainstream the representation of China as an ideological threat. Specifically, a minority of US foreign policy elites who had for a long time advocated the recognition of China as a threat to US national security (sometimes referred to as ‘China hawks’) exploited coinciding debates on Russia’s role in the US and the soft/sharp power concepts. Doing so allowed this minority to persuade liberal audiences that China constituted an ideological threat to the United States all along. In the past, most US foreign policy elites shared a belief in liberal international values, and therefore maintained guarded optimism regarding the possibilities of China’s peaceful rise. This optimism in turn had obstructed a broader consensus on China as the most important threat to US national security.

By mobilising rhetoric from the broader policy arena, the minority view successfully crafted a seemingly natural fit between an attachment to liberal international values and an ideologically threatening China. This made it possible to subsume a geopolitical threat into an ideological one, which effectively lifted the reluctance among liberal foreign policy elites to embrace a realpolitik perspective on great power politics. Consequently, US-Chinese relations were reconfigured into an ideological conflict akin to the Cold War competition with the Soviet Union. As a consequence of such processes, the representation of China as an ideological threat became a catalyst for aligning US foreign policy elites in their understanding of China as the gravest threat to the United States. This took place precisely at a time when China’s growing capabilities as well as its international and domestic behaviour was providing the necessary real-world context.

The article first discusses the literature on threat perceptions, and the China threat specifically, before introducing our analytical framework centred on rhetoric and public legitimation. The subsequent empirical sections analyse the mobilisation of rhetorical resources, how this has made the ideological China threat representation possible and how this in turn has played a key role in reaching the consensus that China constitutes a critical threat to the United States.

Threats and their representation

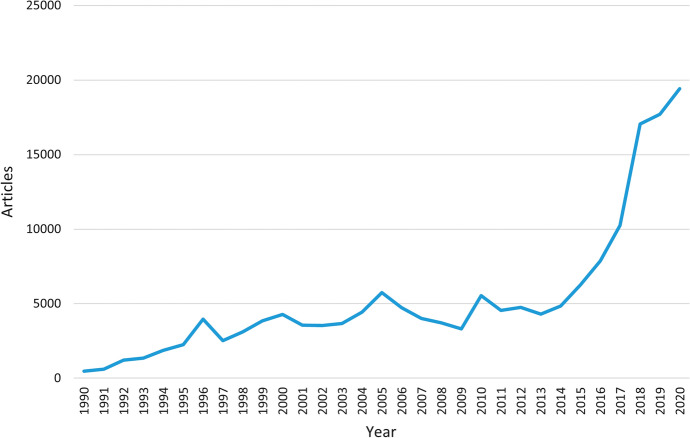

Since around 2017, there has been a sharp increase in the number of news articles that include the words ‘China’ and ‘threat’ in close proximity.3

Figure 1.

Keywords "China" & "Threat" in proximity

In principle, major IR theories are able to shed some light on why policy elites might see China, or its government, as a threat to global peace and prosperity. Offensive realism maintains that threat perceptions depend on power capabilities; the more power a state accumulates, the more threatening it appears to others (e.g. Mearsheimer 2001). Balance-of-threat theories incorporate a state’s intentions as an additional factor that shapes threat perceptions (e.g. Walt 1985). Power transition scholarship assesses the rising state’s level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the international order to assess its potential threat (Tammen et al. 2001), while other scholarship looks more closely at a state’s regime type, domestic behaviour or international rhetoric to deduce its intentions or level of satisfaction with the global order, and thus its potential threat to that order (e.g. Goddard 2018; Cooley et al. 2019). Constructivist research on threats has focused on how images and narratives about China around the world intertwine with domestic politics, political culture or identity formulations, including the (mis-)recognition of state identity and status (e.g. Turner 2014; Rogelja and Tsimonis 2020; Gries and Jing 2019; Pan 2012; Murray 2018). From this perspective, states are represented as threatening not just because their behaviour or intentions are objectively threatening, but because identity constructions are stabilised by the existence of a threatening ‘other’.

The above theories form the basis for most commentary on China’s rise and can explain aspects of increased threat perceptions. For instance, observers have highlighted China’s growing gross domestic product (GDP) as an indicator of its overall growth in power, or its military modernisation and militarisation of the South China Sea as examples of its malign intentions (Stokes 2020; Hutzler 2019; Wong 2019). Jonathan E. Hillman, Hal Brands and Jake Sullivan have presented the Asia Infrastructure and Investment Bank or the Belt and Road Initiative as indicators that China is seeking to establish alternative institutions due to its dissatisfaction with the liberal international order and its role in it (Public Hearing before US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2020, Brands and Sullivan 2020). Fallows (2016) and Wolf (2018) have suggested that the repression of civil society, the increased concentration of power in the hands of Xi Jinping and the Chinese leaders’ assertive foreign policy rhetoric give an impression of what a more powerful China might mean for the world. Other commentary has highlighted the usefulness of a ‘China threat’ in the US domestic context, be it to justify growing military budgets, find a shared enemy or common ground in one of the few areas where bipartisan cooperation is still feasible, or stoke populism for domestic political purposes (Feffer 2021; Hartung 2021; Dollar and Hass 2021; Luo 2021; Yuan and Fu 2020).

While many of these factors certainly play a role, it is important to note that China’s domestic repression and international assertiveness existed well before the emergence of the new consensus (Jerdén 2014). While policy elites tend to defer action when faced with potential but uncertain future threats (Edelstein 2017), it is surprising that the consensus on China’s malign intentions did not emerge far earlier. Arguably, existing theories might explain a slow build-up in threat perceptions, but less so when and especially how such threat perceptions tip into a broad consensus.4

More importantly, existing theories cannot address why China has been cast predominantly as an ideological threat. This could be a consequence of the literature’s focus on why a state may or may not constitute a threat (or is perceived as such), while showing less interest in distinguishing between different forms of threat representations, or why and how one representation assumes dominance. Of course, the dominance of one representation (the ideological one) does not imply the absence of alternatives (such as a geopolitical one), or unequivocal agreement among all observers. Nonetheless, the representation of the China threat predominantly through an ideological lens is surprising for three reasons.

First, compared to the early decades of the People’s Republic, China’s international behaviour is less ideological and – at least in some aspects – less strategically oriented. There is so far little evidence that the 21st century CCP is actively seeking to promote its form of governance abroad, or aiming to strategically undermine the functioning of democracies. As such, many of the concerns regularly cited – such as the appeal of China’s model to authoritarian states or democratic erosion – are predominantly a by-product of the CCP’s governance success at home or preoccupation with domestic regime stability, rather than part of an explicit and comprehensive Chinese strategy to shape the world in its own image (Weiss 2021; Zhao 2022, p. 3).

Second, there has been a re-evaluation of many aspects of China’s behaviour that had not previously been considered particularly ideological – or even threatening. While Xi has expanded foreign ‘united front’ work (Brady 2017), the deployment of such efforts as well as China’s ‘soft power’ campaigns have a long and well-documented heritage (Shambaugh 2013; Lee 2020). For example, an issue that has become a concern recently is China’s Confucius Institutes, which are accused of spreading propaganda under the guise of teaching Chinese language and culture (Jakhar 2019). However, 350 of these institutes, many of them in Western countries, have been established around the world for almost a decade (Shambaugh 2013, p. 245). While they drew some criticism at an earlier time, Confucius Institutes were not as anywhere near as controversial as they have become in recent years.

The idea of an ideologically driven China threat is not entirely new: it was present in the United States in the early years of the Cold War and in the West more generally during the Cultural Revolution (Lovell 2019). However, the idea faded into the background following China’s gradual rapprochement with capitalist powers in the late 1970s (Turner 2014, pp. 121–126). Despite disillusionment after the Tiananmen massacre, the China discourse was characterised by military and economic dangers and opportunities, which meant that the ideological dimension took a back seat (Nymalm 2019; Yang and Liu 2012). While observers were far from oblivious of the Chinese government’s oppressive rule at home, concerns about the party state’s international ideological influence were more limited. Although some observers highlighted ideological differences to predict political tensions between China and the United States (as e.g. reported in Broomfield 2003), China was not seen as a grave threat to the flourishing of liberal democracy in Western countries. Krauthammer (1995), for instance, noted that while China needed to be contained, there was ‘no ideological component to this struggle’. If there was talk of an ideological challenge from China in the 2000s, it chiefly revolved around alternative models of economic development (Ramo 2004). However, this was seen as problematic for new and struggling democracies, and not for the long-established democracies of the West. This makes the recent return of an ideological threat from China to Western liberal democracies all the more striking.

Third, it is unclear why the ideological dimension of the China threat became dominant given that other interpretations are in principle equally plausible and also enjoy support among ‘hawkish’ foreign policy observers and elites. The shifting balance of power in China’s favour, coupled with its behaviour in recent years, provide ample reason for China’s potential threat to the United States to be seen predominantly through a geopolitical lens (such as in Grygiel and Mitchell 2017; Ebbighausen 2020; Yan 2020; Allison 2017). In a similar fashion, China’s economic success and ambition at home and abroad, as well as US economic turmoil since the late 2000s could be expected to engender a view of China as chiefly an economic competitor or threat. Indeed, US-China ‘great-power competition’ – a phrase which had become increasingly central in US foreign policy circles around 2017 (Wyne 2022) – is entirely plausible without a distinct ideological element.

All things considered, while existing IR theories on threats can help to make sense of why China has been increasingly perceived as the most severe security threat to the United States, they struggle to address when and in particular how the ideological representation of the China threat has become the most dominant.

Rhetoric and public legitimation

To understand the emergence of a consensus among US foreign policy elites that China constitutes an ideological threat, we draw from scholarship on public legitimation and rhetoric in foreign policy. As this scholarship focuses on how foreign policy is legitimated through the mobilisation of rhetoric (especially Goddard and Krebs 2015; Jackson 2006; Krebs and Jackson 2007), our framework can be used to examine how specific threat representations become possible, which we base on the assumption that such legitimation processes are characterized by similar patterns.

Legitimation scholarship rejects the notion that reality comes with self-evident meanings and instead emphasises the role of rhetoric in shaping such meanings. Therefore, it is closest to constructivist perspectives on threat representations. Moreover, the tradition treats legitimation as a form of political struggle between competing articulations of foreign policy priorities (Goddard and Krebs 2015, p. 17). Compared to work that focuses predominantly on the discursive content of threat representations, the framework draws attention to the interplay of conditions and factors that enable one articulation to assume dominance.

In principle, there are several broader factors that enhance the likelihood of a successful public legitimation process. First, not all threat representations are equally likely to persuade. There are significant constraints on what can be plausibly claimed – if a given representation of the world or an event seems too alien, it is unlikely to gain support (Weldes 1996, p. 286; Goddard and Krebs 2015, p. 13). Moreover, timing is also an important element; moments of change, turmoil or insecurity constitute critical junctures that can provide debate participants with windows of opportunity through which they can present novel articulations of specific threat representations (Barnett 1999, p. 15; Goddard and Krebs 2015, pp. 28–29; Krebs 2015, pp. 32–36). The broader political context is also important in so far as actors contend to prioritise different policy topics, and to define the national interest or the most severe security threats in what can best be seen as a political arena. In such an arena, some settings tend to be seen as more exclusive and hence more authoritative (e.g. congressional hearings as compared to blog posts) (see e.g. Mitzen 2015; Snyder 2015). Similarly, who promulgates and who listens to specific articulations shapes the possibilities for successful legitimation, as some speakers might be especially authoritative (or weak) vis-à-vis particular audiences (Goddard and Krebs 2015, pp. 27–28; Jackson 2006, p. 28; Smith 2021, p. 4; Senn 2017, p. 610; Krebs and Jackson 2007, p. 47; see also Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, pp. 118–119).

In addition to these broader factors, rhetoric scholarship also examines the skill of speakers as an important element for successful legitimation. Specifically, speakers need to establish a seemingly natural fit between their argument (or representation of the world) and the existing commitments and views of the target audience (Jackson 2006, pp. 27–28; Krebs and Jackson 2007, p. 45). Whether such world views emerge through legitimation processes, or whether the ability of actors to frame and nest their arguments with pre-existing interests is prevalent, is a point of contention (Goddard and Krebs 2015, p. 15). Nonetheless, what matters is the recognition that actors need to carefully craft their rhetoric to resonate so that the audience moves along with the specific representation of the world. These broadly held world views do not need to be fully formalised, but often act as a filter that enables or constrains the arguments that one can possibly make (Dueck 2008, p. 4).

In more concrete terms, speakers need to forge articulations (such as threat representations) out of the rhetorical resources (topoi or rhetorical commonplaces) available in a community of discourse (Jackson 2006, pp. 28–45; see also Krebs and Jackson 2007, pp. 44–47; Shotter 1993; Smith 2021, p. 4; Goddard and Krebs 2015, pp. 29–30; Snyder 2015, p. 174). Such resources can be thought of as the broadly available, vaguely shared raw material on which all public legitimation participants must draw to engage in debate. This material can consist of broad dispositions such as ‘democracy’ or ‘anti-communism’ as in Jackson (2006, p. 70), but can also arguably be slogans, memes, metaphors or concepts such as ‘Major Country Diplomacy’ or ‘rules-based international order’ (Smith 2021; Breuer and Johnston 2019). Just like two interlocutors need some common ground in order to communicate, debate would be impossible without some shared rhetorical resources. The meaning of a specific resource is never fixed but open to contestation and concretisation.

To forge articulations and convince others of the validity of their interpretation of reality, participants in policy debates can utilize different rhetorical strategies (Jackson 2006, pp. 28–45). They might try to fix their preferred meaning of a commonplace (specifying), or challenge an opponent’s formulation, for instance by undermining the legitimacy of the speaker, distracting the audience or challenging the accuracy of the claims advanced by the opponent (breaking). Other options are to apply an established resource, such as widely available narratives, metaphors or analogies, to a new situation; to introduce a commonplace on the fringes or outside of the debate; or to develop a new commonplace (joining). That said, deploying existing rhetoric resources with which audiences are already familiar is far easier than developing entirely novel articulations (Krebs and Jackson 2007, p. 45). Paying attention to the broader political arena in which different policy concerns compete is therefore crucial; we can assume that this context at any given time provides a substantial supply of rhetoric resources familiar to the audience that skilled speakers can draw on to develop more specific representations in a concrete debate.

In this rendition of the role of rhetoric in politics, state behaviour provides a necessary background context that allows for the emergence of different representations and policies. However, which representation persists depends on the more specific mobilization of rhetoric resources. Dueck (2008), for instance, demonstrates that Soviet behaviour during the Cold War provided an important, albeit indeterminate background context that could have supported different policy options for US foreign policymakers – such as rollback, spheres of influence or cooperation. Nonetheless, containment was able to establish itself despite these other plausible options. For our purposes, we can assume that China’s international and domestic conduct over the years have provided a necessary background condition for the general interpretation of a threatening China without which the more specific representation of an ideological threat – brought about through the mobilisation of rhetoric – would not have been possible.

China’s rapid rise, moreover, combined with concerns about America’s future that became particularly salient under the Trump administration, can be seen as a critical juncture that has opened the discursive space, and thus enabled the emergence of novel articulations, such as China as an ideological threat. At the same time, diverging representations of reality – such as what kind of threat China is – do arguably not compete simply among themselves, but exist in a broader political arena where issues vye for the interest of policymakers and broader publics. Therefore, it is necessary to be attentive to how representations of China interact with adjacent policy debates. For instance, it is reasonable to assume that directing attention to the China threat can constitute a rhetorical strategy to divert attention from different policy issues. It is here that rhetoric scholarship is particularly helpful, since most of the literature on representations of China treats policy debates on China as a special case that warrants undivided analytical attention. While this can often be warranted for reasons of research interest, it has meant that adjacent policy issues and their influence on the China debate have been left out of the analysis (see e.g. Pan 2012; Turner 2014).

With our analytical framework, it becomes possible to examine why and how China was represented as an ideological threat to the United States despite the availability and plausibility of other discursive formulations. We have designed a qualitative study of the China discourse in the United States since about 2016. The study proceeded inductively, and gathered threat representations uttered in both more as well as less institutionalised settings, such as congressional hearings, public speeches, newspaper articles and think tank events. We searched common databases and websites (such as govinfo, factiva, the US State Department, the White House and the US Department of Defense) for threat representations, collected publications by influential US foreign policy think tanks and engaged in several months of fieldwork in Washington DC in the spring and summer of 2018. During the fieldwork, we conducted participant-observation at think tank events and did 20 interviews with individuals who we identified as key debate participants. These anonymous interviews were crucial for our own background understanding of the topic, especially to learn more about the strategic use of rhetoric. To increase transparency, we have wherever possible relied on publicly accessible sources for this article. Our analysis is focused on the threat representations advanced by US foreign policy elites and we have not delved into the general public’s image of China.

Based on our analysis, we find that the mobilisation of rhetorical resources from the broader political arena has been crucial to enabling the representation of China as an ideological threat. This in turn has enabled the emergence of a broad consensus on the China threat at this specific point in time. In particular, the mobilisation of debates on two topics – Russia and the soft power concept – proved to be key to the outcome. This is not to say that other rhetoric formulations that facilitate the representation of China as an ideological threat were absent in the broader discourse. For instance, officials, scholars and journalists sometimes refer to the Chinese concepts of ‘all-under-Heaven’ and ‘Xi Jinping thought’ as examples of alternative Chinese visions of world order (e.g. US Government Publishing Office 2018). However, these notions are mostly discussed in the context of Xi Jinping’s efforts to centralize power, or his growing personality cult, and less as a direct ideological challenge to the West (see e.g. Tepperman 2018; Hunt 2017). Even when commentators point to the Communist nature of the regime to underscore its threat to the United States, they tend to first mobilise the Russia or soft power debates (e.g. O'Brien 2020; DemDigest 2018). In what follows, we demonstrate in more detail how the mobilisation of coinciding debates has unfolded.

From Russia to China

A key factor allowing US foreign policy elites to cast China as an ideological threat was the emergence of a discourse around 2014 that portrays Russia as a grave threat to Western democracies. This temporally preceding debate provided ample rhetorical material on which actors who sought to present China as a general threat could draw to successfully forge a representation of China as an ideological threat.

Unlike Western fears of China, fears of the Soviet Union had an ideological element throughout the Cold War period, alongside geopolitical concerns. Of special relevance to our study, many accounts described how the Soviet Union took advantage of open societies to undermine the ‘Free World’ through so-called information or influence operations that relied on deceit and infiltration (Shultz et al. 1984; Borchgrave and Moss 1980). Central to the belief in the effectiveness of Soviet interference was a recurrent lack of self-confidence in the capacity of Western societies to prevail in an ideological competition with an authoritarian opponent. Following the break-up of the Soviet Union, however, acute concerns over authoritarian interference receded. Victory in the Cold War not only removed the main adversary, but also bolstered confidence in the robustness of Western political systems. Nonetheless, the rhetorical resource of ‘authoritarian interference’ remained a familiar rhetoric resource.

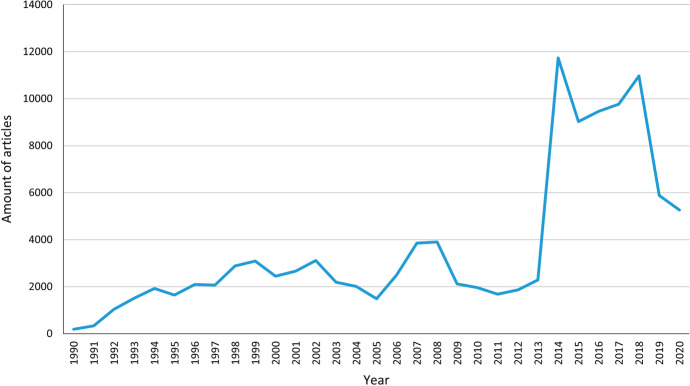

Several decades later, this resource was reactivated and joined to the successor state of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation. Especially following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, news reports portraying Russia as a threat spiked (Figure 2),5 and the concept of Russian information warfare became widely spread (see e.g. Giles 2016; Kragh and Åsberg 2017). Combined with Russia’s interference in the US presidential election in 2016, the authoritarian interference notion came back into mainstream political and media discussion, thereby making it available as a rhetoric resource for the China debate at a critical point in time.

Figure 2.

Keywords "Russia" & "Threat" in proximity

A 2014 report, which suggested that Russia was taking advantage of the freedom of information in Western societies to undermine democratic processes, was key to popularising this idea. The report suggested that the West was grossly unprepared, and that this lack of preparedness was paving the way for the emergence of an ‘anti-Western authoritarian Internationale’ (Pomerantsev and Weiss 2014, p. 6).

There was a certain irony as such arguments spread. While the conservative right had challenged anyone who seemed too sympathetic to the Soviet Union or socialism during the Cold War (Storrs 2012), these roles were reversed following the emergence of the new ideological Russia threat. Domestic criticism of US President Donald J. Trump increasingly centred on allegations of collusion with Russia, and denouncing Moscow’s attempts at interference effectively became the position of commentators with an attachment to liberal international values. Terms strikingly similar to those used during the heyday of US anti-communism became increasingly common among Trump’s often liberal critics, as when he was described as a Russian ‘asset’ or ‘agent’ by former acting FBI Director Andrew McCabe, or ‘a useful idiot’ by Former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright (Sullivan and Jarrett 2019; Griffiths 2016). The growing familiarity with the rhetoric of Russian interference and its promotion by authoritative figures facilitated an acceptance among liberal and left thinkers that authoritarian influence operations might constitute lethal threats to open democracies – a central reconfiguration of an audience susceptible to the notion of foreign interference.

‘Russian interference’ therefore provided a useful rhetoric resource for the representation of China as an ideological threat. The more audiences became familiar with and attached to the notion of Russian interference, the easier it became to mobilise this resource and adapt it to the China debate. In other words, a rhetoric resource from an adjacent debate in the political arena was joined with the more specific representation of China as an ideological threat.

Four lines of argument – resemblance, complementarity, learning and threat magnitude – were central to this linking of the rhetorical commonplace into the China discussion, which ultimately implied a coupling, or conflation, of Russia with China. The first argument is one of a resemblance between China’s and Russia’s goals and tactics, where observers, typically those who sought to draw attention to China’s overall threat, noted that China and in particular its government was also making use of the openness of Western societies to attack them from within. Rogin, writing for the Washington Post, argued that ‘behind the scenes the US government is preparing for the possibility that the Chinese government will decide to weaponize the influence network inside the United States that it has been building for years. Although Beijing has not yet employed Russian-style ‘active measures’, it has these capabilities at the ready’ (Rogin 2018a; for a similar argument, see Brands and Yoshihara 2018; Lawler 2019). Later on, he quotes an anonymous official in the Trump administration to equip his representation with further authority: ‘We’ve seen a lot of preparatory work by the Chinese….These Chinese activities are all about influencing our democratic processes’.

Similarly, during a public seminar honouring a speech by former US President Ronald Reagan in defence of liberty and democratic values, Peter Mattis, an analyst who would go on to work in Congress on human rights legislation related to China, recollected the following exchange from a Congressional hearing:

One of the participants in a House Armed Services Committee hearing on this subject, when he was asked about where are we on the (…) Russia problem or the China problem, the speaker on the Russia problem said, ‘well we’ve probably sort of flunked a few grades, but we’re back in, you know early part of high school or middle school’, to which the person speaking on China responded, ‘I think we’re still struggling to enter kindergarten’. (Heritage Foundation 2018)

The ‘discovery’ of a resemblance between Russia and China allowed observers to draw attention to aspects of China’s international role that had previously been little discussed. This brought a re-specifying of the meaning of China’s international profile as not only threatening in general, but also, more specifically, threatening in an ideological sense. This became a crucial link in the re-emergence of an ideological China threat to Western democracies.

The second joining of the authoritarian interference commonplace stresses a complementarity between China’s and Russia’s influence activities. By emphasising the match between Chinese and Russian activities and how they present an ideological challenge to the flourishing of democracies, it becomes increasingly difficult to discuss Russian interference without China in tow. As an article in the widely circulated Foreign Affairs notes:

Russian and Chinese foreign policy tactics are converging in new and synergistic ways. Russian foreign policy is confrontational and brazen. China, so far, has used a subtler and more risk-averse strategy, preferring stability that is conducive to building economic ties and influence. Although these two approaches are different and seemingly uncoordinated, taken together, they are having a more corrosive effect on democracy than either would have single-handedly. (Kendall-Taylor and Shullman 2018)

The third argument highlights how China is learning from Russia’s experiences. The ideological Russia threat holds that Moscow has developed a new and powerful strategy for undermining Western democracies by adapting Soviet-era tactics to today’s circumstances. Here, some observers concerned with the China threat claim to have identified a process of policy learning: China adopts tried and tested Russian tactics of more overt and risky interference which amounts to an ideological challenge to the United States. This is exemplified in this 2018 quote from Peter Mattis: ‘Beijing’s methods also appear to be evolving over the last year to incorporate Russian techniques, if its operations on Taiwan can be viewed as the leading edge’ (Mattis 2018). As the Alliance for Securing Democracy, a bipartisan advocacy group, writes,

China’s more confrontational posture on COVID-19 represents a clear departure from its past behaviour and signals a move toward a more Russian style of information manipulation. (…) Chinese officials and state-backed media’s messaging patterns on the Uighurs in Xinjiang reflect many of the classic elements of Russian disinformation, with a uniquely Chinese twist. (Alliance For Securing Democracy 2020)

Sometimes, China is described as outdoing its teacher, such as in this example from the Brookings Institution:

China has been studying Russian activities for quite a number of years and learning from its experiences. They are getting better than the Russians in many ways. Russians still rely very much on bots…that are propagating disinformation, whereas the Chinese still seem to be using human beings, which means that the content can react more quickly to situations. (Brookings Institution 2018)

The notion that China, or rather the CCP, studies Russia's experience certainly strikes a chord with anyone familiar with modern Chinese history.6 After all, the historical development of the People’s Republic cannot be understood without underscoring the lessons – successes as well as failures – drawn from the Soviet legacy. By incorporating the learning argument, observers can further strengthen the association between Russia and China in terms of an ideological threat.

The final argument revolves around threat magnitude and describes China’s influence activities and ideological threat as a bigger danger than those of Russia. As Rogin writes: ‘Russian political interference is the short-term emergency, but Chinese political interference is the long-term challenge’ (Rogin 2018b). The reasons for China’s edge are said to lie in its greater resources and farsightedness, and in the fact that its tactics are better suited to exploiting the weaknesses in the targeted societies. As an analysis from the Hudson Institute notes, ‘Russia’s interference and election meddling dominate the headlines and Washington’s attention. But beneath the radar, another country’s interference is expanding, dwarfing Russia’s short-term disruption’ (Parello-Plesner 2021). Pouring huge resources into international influence provides tactical advantages: ‘Unlike Russia, with its relatively quick interference operations, the ‘CCP builds varied and long-term relationships’ (Parello-Plesner 2021). By relying on widespread concerns about Russian interference, and by arguing that Russia’s ideological threat is dwarfed by China, proponents hope to convince their audiences that China is a worse ideological threat that requires a harder policy response.

Thus, the new ideological China threat argument builds on an old rhetoric resource that can be traced back to the beginnings of the communist challenge to democracy. This authoritarian interference commonplace was reactivated around 2014 and updated in debates on Russia’s actions, when actors who sought to persuade foreign policy elites to recognise China as a threat latched on to these arguments to present China as an ideological threat. This connection in turn provides an important insight into the specific timing of the representations of the China threat. Without the preceding Russia debate, much of the key rhetoric material would not have been as readily available.

Slowly but steadily, such arguments made their way up to the highest levels of government. During a 2018 interview, just before he became US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo argued with respect to covert influence operations that ‘[t]he Chinese have a much bigger footprint upon which to execute that mission than the Russians do’ (BBC News 2018), thereby echoing the notion of a difference in threat magnitude. In a similar vein, referring to influencing campaigns, the then-Vice President, Mike Pence, noted in 2018 that ‘what the Russians are doing pales in comparison to what China is doing across this country’ (Pence 2020).

Of course, this form of rhetoric mobilisation also played a central role in US domestic political debates since it served to break the argument that Trump’s election success had been actively helped by Russian interference. Hence, representing China as ideologically threatening became popular among conservative observers, even if it is unclear whether they actively believed in their representations or were instead seeking to distract from other issues in the wider political arena.

The notion of an ideological China threat was enabled through the mobilisation of rhetoric resources from the adjacent Russia debate for an audience that had grown increasingly worried about ideological challenges to democracy. In the ultimate example of how the mobilisation of rhetoric resources from the Russia debate has shaped the China debate, China has now assumed the Soviet Union’s position in increasingly common references to a ‘new Cold War’ between the United States and China (‘Anonymous’ 2021; Layne 2020). In other words, the new ideological China threat has assumed a life on its own. At the time of writing, the idea that the Chinese government is behind a comprehensive strategy that constitutes a serious threat to Western democracy has become an established social fact in many policy, media and think tank circles – even without the need for explicit reminders of how this relates to the analogous threat from Russia. This is exemplified for instance through President Biden’s call to ‘rally the nations of the world to defend democracy globally [and] to push back the authoritarianism’s advance’, by which he predominantly meant China (The White House 2021).

From soft power to sharp power

As this section will demonstrate, the second rhetorical resource that US foreign policy elites mobilised in the new ideological China threat discourse is the concept of soft power. Soft power, or the ability to get other countries to want what you want through attraction, has become one of the most pervasive political concepts of the past 30 years. Developed by Joseph Nye at the end of the 1980s, anyone with even a mild interest in international relations is now familiar with the term. It is this familiarity coupled with the concept’s notorious vagueness that makes soft power a typical example of a widely available rhetorical resource. In public debates, participants can exploit a widespread weak attachment to the concept and apply it to new situations in the hope that the audience follows along.

The soft power concept has been particularly popular in two distinct contexts. First, observers who value diplomacy, multilateralism, international institutions and democratic values – that is, observers with an attachment to liberal international values – embraced the concept early on, as such issues were typically portrayed as important sources of soft power (Winkler 2019). Second, soft power has also been influential in authoritarian states, including China (Barr et al. 2015). This has in the past led to significant confusion and unease among many Western observers who struggled to understand not only how the concept could have become so popular despite its ‘liberal democratic bias’, but also how to assess China’s soft power strategies and their effects (Keating and Kaczmarska 2019; Barr et al. 2015).

By far the most common understanding was that China and its government was embracing soft power to offset perceptions of its rise as a threat and to demonstrate its ‘peaceful’ or ‘soft’ nature (Wang 2008; Kurlantzick 2008). Nonetheless, so the argument goes, despite the significant funds poured into establishing its soft power credentials, China, and especially the CCP, ultimately do not understand what the concept is really about – or that it would have to do away with its authoritarian impulses in order to wield soft power. A common conclusion is that most of China’s soft power efforts have been so artless and clumsy that there is little to worry about (Gill and Huang 2006; Cho and Jeong 2008; Nye 2013). Another response cautiously regarded China’s interest in soft power as a positive development and a sign of its potential socialisation into the international order. After all, if China is aiming for ‘genuine’ soft power, this indicates an interest in participating in the international order on conditions set by the West. Thus, hopes were high that by encouraging Chinese students to study abroad, consume Hollywood movies and learn about the democratic way of life, China would eventually become more like a Western democracy, or at least move in a positive direction (Shambaugh 2005, personal interview #2 by co-author, 5 June 2018; Zoellick 2005; Glaser and Murphy 2009).

Around 2016, however, a decisively different understanding of authoritarian states’ soft power emerged. A group of scholars and analysts, who shared a long-standing interest in the promotion and defence of democracy, started to describe China’s soft power push as a dangerous appropriation of the concept for malign purposes. Specifically, they suggested that the concept had been ‘hijacked’ as it had allowed authoritarian actors to develop deceitful influence activities, such as China’s Confucius Institutes, under the pretence of soft power (Walker 2016). Efforts to develop this argument culminated in a 2017 report by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), a key organization in promoting the resilience of democracy (Cardenal et al. 2017).

The sharp power concept coined in the report, and more fully defined as ‘authoritarian influence efforts [to] pierce, penetrate, or perforate the information environments in the targeted countries’ (Walker and Ludwig 2017, p. 13), became a key component and driver of the re-emerging ideological China threat. In response to the report, numerous think tank events were organised and many publications emerged to discuss the new concept (The Economist 2017; Brookings Institution 2018; Heritage Foundation 2018; Stimson Center 2018). In the United States, China’s ‘sharp power’ was the subject of a congressional hearing in 2017 (US Government Publishing Office 2017), central to a letter by a bipartisan group of Senators urging the Trump administration to be more vigilant about China (Cortez Masto et al. 2018) and referred to in several bills to Congress, such as the 2018 ‘Countering the Chinese Government and Communist Party’s Political Influence Operations Act’.7 In only a few years, the concept had come to play a key role in policy debates that cast China as an ideological threat. How can the success of the concept and its place in the new discourse be explained?

Sharp power is a new rhetorical resource forged out of the established soft power commonplace; that is, a novel resource created by joining an established resource to a new context. A major part of its success lies in how advocates of sharp power were able to rely on the popularity of soft power to introduce a new concept that seemed familiar but also distinct enough to warrant a new term. Hence, the central point of departure in reports, interviews and events on ‘sharp power’ was to establish the fact that the term had been coined in order to satisfy the need for a new vocabulary to describe the phenomenon of authoritarian influence operations, in the hope that no one would any longer mistake one for the other (Walker and Ludwig 2017, p. 13). ‘Sharp power’ was thus presented as a natural and necessary addition to the soft power concept that, once embraced, implies an understanding of China as an ideological threat. In so doing, it also relied on the increasingly available rhetoric resource of Russian interference as a form of sharp power. The two debates were thus fused together still further.

Advocates of the new concept might just as well have talked in terms of ‘authoritarian influence operations’ and argued that they amount to an ideological threat from China. By calling the phenomenon ‘sharp power’, however, it was possible to appeal to audiences with a prior attachment to soft power that had in the past struggled to make sense of China’s seemingly conscious soft power push. As one expert who had been particularly involved with the soft power debate remarked:

…we all said China was weak in its soft power. But we still called it soft power. (…) I think it’s important to not talk about what China is doing as similar to what we have called soft power. And you know, somebody had to come up with a term to describe what China is doing. (…) So everybody latched on to this one. I’m happy to use it because (…) to me, it’s clarifying (personal interview #3 by co-author, 6 June 2018).

The sharp power concept thus provides a way to deal with China’s professed interest in soft power while at the same time affirming the value and relevance of ‘genuine’ soft power. ‘Authoritarian soft power’ was therefore decoupled from ‘benign soft power’, which meant that what the Chinese government is doing could finally be distinguished from what the West stands for. That such an analytical step was prudent and necessary was corroborated by none other than Nye himself, who ‘thoroughly applauded’ the NED report (Pacific Council on International Policy 2018, see also Nye 2018). Nye’s endorsement provided crucial authority for the appropriateness of the sharp power concept, which actors active in the debate also pointed out (personal interview #4 by co-author, 20 June 2018).

Beyond attracting liberal international audiences, sharp power also became integral to the new ideological China threat by way of its ‘hardening’ of the soft power concept. While soft power had always been popular among adherents to liberal internationalism, the concept had been largely disregarded or even attacked by realists. For them, a belief in soft power was utterly naive – just like liberal internationalism itself (Ferguson 2003; Layne 2010). From the outset, the policy of facilitating China’s integration into the Western-led international order had been seen as highly problematic. This approach merely bought China time to rise under the pretence of peaceful intentions until it could become powerful enough to challenge the West outright (Hornung 2020; Thayer and Friend 2018). Realists therefore regarded soft power as one of many distractions that had preoccupied those observing Chinese current affairs as a profession – the so called ‘China watchers’ – for too long, which meant that they had been blind to how rapidly China had become a threat across all dimensions:

China has put in place policies to make itself into a great powerful country at the expense of others and particularly at the expense of the United States.... [By the time] the US really figured out what the Chinese were doing they were so far along it was impossible to really stop them. And the diplomatic strategy that we opted for was very ineffective. The Chinese have continued to implement that strategy with very little push back from anywhere. (…) The Chinese love dialogue. You know they’ll get you in a room and they will talk to you forever and you will come out at the end of the day with no understanding, no agreement. (personal interview #3 by co-author, 6 June 2018)

In this context, sharp power resonates since it confirms the view that the ‘kumbaya sentiment’ of many China watchers had made a mess of the West’s China policy in the past (personal interview #1 by co-author, 1 June 2018).

China was also seen as exploiting the United States’ willingness to wield its soft power. According to this argument, a naive belief in the effectiveness of soft power had led the United States to open its doors wide to Chinese students and businesses, some of which were able to infiltrate, exploit and undermine the very structures that enabled such openness. In the words of FBI Director Christopher Wray, the open US research and development environment means that China should be considered a ‘whole-of-society threat’ (Redden 2018), a point that a congressional staffer involved in the sharp power letter also repeatedly emphasised (personal interview #6 by co-author, 24 August 2018). Because sharp power stresses the alleged problems with the original concept of soft power, sharp power has provided a sense of gratification for observers who can point out how they had told everyone about the dangers, albeit to no avail. As one of soft power’s major critics, Niall Ferguson, notes:

I also agree wholeheartedly that it was naive to assume – as the past three [US] administrations tended to – that including Russia and China ‘in international institutions and global commerce would turn them into benign actors and trustworthy partners.’8 A new report on China’s ‘sharp power’ by the National Endowment for Democracy shows just how wrong this was (Ferguson 2019).

Sharp power therefore provided a way for realists to voice their criticism of soft power. At the same time, they have been able to rely on the familiar language of international institutions and public diplomacy to present its features as dangerous if placed in the wrong hands. In this way, sharp power ‘hijacks’ the notion of soft power, taking an idea originally entrenched in liberal internationalism, appropriating it and giving it a realist twist. Furthermore, while sharp power emerges as something different to soft power, it legitimises the existence of genuine soft power. This makes the rhetoric more acceptable to liberal internationalists. Hence, the sharp power concept engages two different groups that each embrace the concept for very different reasons but, in so doing, agree that China’s sharp power constitutes an ideological threat – specifically to the United States.

The mobilisation of rhetoric resources from the broader political arena, i.e. the joining of familiar material from the Russia debate to China, and from the soft power debate to sharp power, had one crucial consequence: it reduced the size of the old division between observers warning of the China threat and those who stressed the opportunities linked to China’s rise. In the past, this division between ‘hawks’ and ‘doves’ had stood in the way of creating a foreign policy consensus on China, and the China policy oscillated between periods of greater or declining optimism (Turner 2014; Pan 2012). Now that China’s international and domestic behaviour provided a necessary background and foreign policy elites found themselves at a critical juncture due to the uncertainty over the role of the United States in the world, debate participants who sought to create a common understanding that China constitutes the United States’ most severe security threat were able to persuade diverse audiences of their position, as they could present the China threat as an ideological one.

Rather than perceiving US-Chinese relations as merely a geopolitical conflict, the dominant perspective has thus assumed an ideological dimension, as illustrated in common references to a ‘new Cold War’ (see e.g. ‘Anonymous’ 2021; Layne 2020). The ideological dimension became a crucial catalyst to drive the overall perception of China over into one of a severe security threat. In terms of timing, the existence of a critical juncture was important, but so was the availability of rhetorical resources from the broader political arena that could be mobilised from around 2016.

When President Biden assumed office in early 2021, he faced a novel status quo brought about through the previous mobilisation of rhetoric. This curtailed the ability of his administration to represent China in any other light than an ideological threat to US interests and the world. The rhetoric resource of China as an ideological threat had become so familiar and widespread that it was inserted into all kinds of public debate, such as when presenting the need to invest in domestic infrastructure to ensure, in Biden’s words, that China doesn’t ‘eat our lunch’ (BBC News 2021). By now, the end of the ‘engagement policy’ has become a fait accompli, and we are experiencing a new era of ‘strategic competition’ that is likely to be characterized by an ever-increasing volatility of US-China relations (McCourt 2022).

Conclusion: ideologizing geopolitics?

The aim of this article was to examine how, why and to what consequence US foreign policy elites have embraced the representation of China as an ideological threat, in particular given that other discursive formulations of the China threat, such as a geopolitical argument, were available. The article has found that the mobilisation of rhetoric resources from the broader policy debate was crucial for ‘hawkish’ observers of China to establishing a seemingly natural fit between a commitment to liberal international values and a concern with China’s ideological outreach. Specifically, this made it possible to conceptualise China’s international behaviour as ideologically challenging as well as geopolitically problematic, which was a key step in the overall emergence of the perception of China as a severe threat to the United States. This representation of China as an ideological threat was possible as China’s repressive and assertive behaviour provided a necessary backdrop, while the aftermath of Trump’s election constituted a critical juncture that provided a window of opportunity for actors to advance novel discursive formulations. The broader political arena thus provided familiar rhetorical material that skilful actors could draw on to represent China as an ideological threat, thereby bridging a former divide between US foreign policy elites with an attachment to liberal international values, and those with more realist perspectives on China’s rise.

The findings of this paper beg the question whether it is even possible for US foreign policy elites to interpret threats to the United States and the international order in purely geopolitical terms, or whether threats can only be ‘seen’ once they are ‘ideologized’. If this was the case, it would suggest that US foreign policy might be characterized by a ‘geopolitical blindness’; as long as US foreign policy elites by and large believe that potential geopolitical rivals are playing by the rules of the US-led international order (e.g., Japan, UK or Germany), or can be coaxed towards liberal democracy, as was the case with rising China until the mid-2016, such states are just not seen as geopolitical threats. If so, the ideological China threat would not simply be one among several competing discursive formulations of the China threat, but perhaps the only possible representation of the China threat that could persuade US foreign policy elites to think of China as threatening, something which in turn became possible only at this point in time through the successful mobilisation of rhetoric resources from adjacent policy debates.

Moreover, if geopolitical threats indeed do not ‘exist’ unless rendered ideological, it would suggest that US foreign policy, and specifically its continued embrace of primacy as the central element of US grand strategy, was not simply a consequence of geopolitical realities, such as anarchy or the distribution of material capabilities, or a pursuit of economic or civilizational goals. Instead, our work here ties in with recent studies on grand strategy that point to the role of a shared, axiomatic belief in both exceptionalism and primacy as driving US grand strategy (Porter 2018; Wertheim 2020; Thompson 2015). Future research could examine ideological threats and their role in the domestic and international justification of US primacy.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the International Studies Association (ISA) annual meeting in Toronto in 2019, as well as internal workshops at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs and the Swedish Defence University in 2019 and 2020. We would like to thank the participants for their useful comments on those occasions, especially Arita Holmberg; Charlotte Wagnsson; Karl Gustafsson; Linus Hagström; Magnus Christiansson; Mikael Weissmann; Nina Krickel-Choi; Steven F. Jackson; Tim Rühlig; Tom Lundborg and Viking Bohman. Our thanks also extend to the three anonymous reviewers from the Journal of International Relations and Development who have provided extremely helpful and extensive comments. The article has received funding from the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation (MMW2013.0162), the Swedish Research Council (2021-06652), and the Swedish Ministry of Defense.

Biographies

Stephanie Christine Winkler

has a PhD in International Relations from Stockholm University and is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Economic History and International Relations at Stockholm University. She has most recently published in the Cambridge Review of International Affairs. Her research interests include the role of concepts in International Relations, power shift theories, United States, China and Japan as well as the soft power concept. Her work with this article was supported by the Swedish Research Council (2021–06652), the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation (MMW2013.0162) and the Swedish Ministry of Defense’s Transatlantic and European Security project.

Björn Jerdén

is Director of the Swedish National China Centre at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs (UI). His research has recently appeared in The China Review, Internasjonal Politikk, and Review of International Studies. His work with this article was supported by the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation (MMW2013.0162).

Footnotes

‘Ideology’ can best be understood as an essentially contested concept, a ‘polysemic word which for some even connotes more than one concept, bound in various ways to different disciplines’ (Freeden 2008, p. 13). For our purpose, we rely on a brief and historically informed understanding of ‘ideology’ as a competing world view and way of life, expressed through specific political, social, economic and cultural arrangements, that claims and promotes the universal applicability of its ideology (for a similar rendition, see Westad 2005, esp. pp. 4-5).

In the China discourse examined in this paper, China, or the Chinese people, are often conflated with the state/Chinese Communist Party (see e.g. Redden 2018). Although we are highly critical of this, the purpose of this paper is not to scrutinize the conflation in greater detail.

The search was carried out of the Factiva database by selecting the source category ‘US sources’ and entering ‘chin* NEAR5 threat*’, which returned results where China (or Chinese) and threat (or threatening) appear within five words. The trend illustrated in figure 1 is not simply driven by a general increase in reporting on China, as a similar pattern is visible for articles that mention China and threat within five words compared to the total articles on China. Of course, an increase in the number of articles containing these words does not imply agreement on what precisely the China threat is or even whether there is one. Nonetheless, no one would be trying to refute the trope if there was not a general sentiment that the China threat was rising.

For a sociological analysis on the new consensus specifically focussed on the professional struggles in the China expert community, see McCourt (2022).

Same approach as noted in note 2.

As also emphasised repeatedly during the interviews, especially personal interview #3 by co-author, 6 June 2018; personal interview #4 by co-author, 20 June 2018; personal interview #5 by co-author, 27 June, 2018.

A bipartisan bill sponsored by Marco Rubio, the ‘Countering the Chinese government and Communist Party’s political influence operations act’, was introduced to the Senate on 28 June 2018 (S. 3171) and reintroduced on 13 February 2019 (S. 480).

Ferguson is referring to The White House (2017).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- ‘Anonymous’ (2021) The Longer Telegram: Toward a new American China strategy, Atlantic Council, 28 January, available at https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/content-series/atlantic-council-strategy-paper-series/the-longer-telegram/ (22 March, 2021).

- Alliance For Securing Democracy (2020) The Alliance for Securing Democracy Expands Hamilton 2.0 Dashboard to Include China, 3 March, available at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/the-alliance-for-securing-democracy-expands-hamilton-2-0-dashboard-to-include-china/ (15 February, 2021).

- Allison Graham. Destined for war: Can America and China escape Thucydides’s trap? New York: Houghton Mifflin; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett Michael. Culture, Strategy and Foreign Policy Change. European Journal of International Relations. 1999;5(1):5–36. doi: 10.1177/1354066199005001001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barr, Michael, Valentina Feklyunina and Sarina Theys, eds (2015) ‘Introduction: The Soft Power of Hard States’ Politics 35(3–4). 10.1111/1467-9256.12210.

- BBC News (2021) ‘Biden Warns China Will ‘Eat our lunch’ on Infrastructure Spending’, 12 February, available at https://www.bbc.com/news/business-56036245 (7 June, 2021).

- BBC News (2018) ‘CIA Chief Says China ‘As Big a Threat to US’ as Russia’, 30 January, available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-42867076 (30 January, 2018).

- Blinken, Anthony J. 2022. The Administration’s Approach to the People’s Republic of China, available at https://www.state.gov/the-administrations-approach-to-the-peoples-republic-of-china/ (6 January 2022).

- Borchgrave, Arnaud de and Robert Moss (1980) The Spike, New York: Crown Publishers.

- Bourdieu Pierre, Wacquant Loïc J. D. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Brady and Anne-Marie (2017) ‘Magic Weapons. China’s Political Influence Activities Under Xi Jinping’, 18 September, Wilson Center, available at https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/magic-weapons-chinas-political-influence-activities-under-xi-jinping (22 February, 2021).

- Brands, Hal and Sullivan, Jake (2020) China Has Two Paths to Global Domination, In Foreign Policy, 22 May, available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/22/china-superpower-two-paths-global-domination-cold-war/.

- Brands, Hal and Yoshihara, Toshi (2018) ‘How to Wage Political Warfare’, The National Interest, 16 December, available at https://nationalinterest.org/feature/how-wage-political-warfare-38802 (15 February, 2021).

- Breuer Adam, Johnston Alastair Iain. Memes, Narratives and the Emergent US–China Security Dilemma. Cambridge Review of International Affairs. 2019;32(4):429–455. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2019.1622083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brookings Institution (2018) A Conversation About China’s Sharp Power and Taiwan, Washington, DC, available at https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.hudson.org/files/publications/JonasFINAL.pdf (2 November, 2020).

- Broomfield Emma V. Perceptions of Danger. The China Threat Theory. Journal of Contemporary China. 2003;12(35):265–284. doi: 10.1080/1067056022000054605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenal, Juan Pablo, Jacek Kucharczyk, Grigorij Mesežnikov and Gabriela Pleschová (2017) ‘Sharp power. Rising authoritarian influence’, International Forum for Democratic Studies/National Endowment for Democracy, 5 December, available at https://www.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Sharp-Power-Rising-Authoritarian-Influence-Full-Report.pdf (21 October, 2020).

- Cho Young Nam, Jeong Jong Ho. China’s Soft Power: Discussions, Resources, and Prospects. Asian Survey. 2008;48(3):453–472. doi: 10.1525/as.2008.48.3.453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley Alexander, Nexon Daniel, Ward Steven. Revising order or challenging the balance of military power? An alternative typology of revisionist and status-quo states. Review of International Studies. 2019;45(04):689–708. doi: 10.1017/S0260210519000019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez Masto, Catherine; Michael F. Bennet, Sherrod Brown, Christopher A. Coons, Ted Cruz, Cory Gardner et al. (2018) Open Letter to the Trump Administration, Washington, DC, 8 June, available at https://www.cortezmasto.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Chinese%20Influence%20Operations%20Letter%20-%20with%20Footnotes%20.pdf (10 July, 2018).

- DemDigest (2018) Blunting China’s sharp power: strengthening Xi's rule 'not just a power grab'?, available at https://www.demdigest.org/blunting-chinas-sharp-power-strengthening-communist-party-rule-not-just-power-grab/ (23 August, 2022).

- Dollar, David and Ryan Hass (2021) ‘Getting the China challenge Right’, Brookings Institution, 25 January, available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/getting-the-china-challenge-right/ (29 July, 2021).

- Dueck, Colin (2008) Reluctant Crusaders: Power, Culture and Change in American Grand Strategy, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ebbighausen, Rodion (2020) ‘Mearsheimer: The US Won’t Tolerate China as Peer Competitor’, Deutsche Welle, 23 September, available at https://www.dw.com/en/chinas-rise-and-conflict-with-us/a-55026173 (23 September, 2020).

- Edelstein, David M. (2017) Over the Horizon. Time, Uncertainty, and the Rise of Great Powers, Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press.

- Fallows, James (2016) ‘China’s Threat to the US’, The Atlantic, 15 November, available at https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/12/chinas-great-leap-backward/505817/ (22 July, 2021).

- FBI (2022) Director Wray Addresses Threats Posed to the U.S. by China, available at https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/director-wray-addresses-threats-posed-to-the-us-by-china-020122 (22 November, 2022).

- Feffer, John (2021) ‘China and the Perils of Bipartisanship’, Foreign Policy in Focus, available at https://fpif.org/china-and-the-perils-of-bipartisanship/ (29 July, 2021).

- Ferguson, Niall (2003) ‘Think again: Power’, Foreign Policy 134: 18–24, available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/3183518.

- Ferguson, Niall (2019) ‘Speak Less Softly but do not Forget the Big Stick’, The Globe and Mail, 28 December, available at https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/speak-less-softly-but-do-not-forget-the-big-stick/article37442146/ (21 October, 2020).

- Freeden Michael. Ideologies and political theory. A conceptual approach, Oxford: Clarendon Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Keir (2016) ‘Russia’s ‘new’ tools for confronting the West: Continuity and innovation in Moscow’s exercise of power’, Chatham House, 24 March, available at https://www.chathamhouse.org/2016/03/russias-new-tools-confronting-west-continuity-and-innovation-moscows-exercise-power (21 October, 2020).

- Gill Bates, Huang Yanzhong. Sources and Limits of Chinese ‘Soft Power’. Survival. 2006;48(2):17–36. doi: 10.1080/00396330600765377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Bonnie S. and Melissa E. Murphy (2009) ‘Soft Power with Chinese Characteristics: The ongoing debate’ in Carola McGiffert, ed., Chinese Soft Power and its Implications for The United States: Competition and Cooperation in The Developing World, a report of the CSIS smart power initiative. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies. (20 February, 2021).

- Goddard Stacie E. When Right Makes Might: Rising Powers and World Order. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard Stacie E, Krebs Ronald R. Rhetoric, Legitimation, and Grand Strategy. Security Studies. 2015;24(1):5–36. doi: 10.1080/09636412.2014.1001198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gries Peter, Jing Yiming. Are the US and China fated to fight? How narratives of ‘power transition’ shape great power war or peace. Cambridge Review of International Affairs. 2019;32(4):456–482. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2019.1623170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, Brent (2016) ‘Albright: Trump Fits the Mold of Russia’s ‘Useful Idiot’’, Politico, 24 October, available at https://www.politico.com/story/2016/10/trump-russia-useful-idiot-madeleine-albright-230238 (28 December, 2022).

- Grygiel, Jakub J. and A. Wess Mitchell (2017) The Unquiet Frontier, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hartung, William (2021) ‘Exaggerating Challenge from China Threatens US Security’, Forbes, 22 June, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/williamhartung/2021/06/22/exaggerating-challenge-from-china-threatens-us-security/?sh=28ef168b5d19 (29 July, 2021).

- Heritage Foundation (2018) Sharp Power: The Growing Challenge to Democracy, Panel Discussion, 29 November, Washington, DC, available at https://www.heritage.org/event/sharp-power-the-growing-challenge-democracy (21 October, 2020).

- Hornung, Jeffrey W. (2020) ‘Don’t Be Fooled by China’s Mask Diplomacy’, Rand Corporation, 5 May, available at https://www.rand.org/blog/2020/05/dont-be-fooled-by-chinas-mask-diplomacy.html (21 October, 2020).

- Hunt, Katie (2017) China's 19th party congress: What you need to know', CNN politics, 17 October (23 August, 2022).

- Hutzler, Charles (2019) ‘China’s Growing Power, and a Growing Backlash’, The Wall Street Journal, 17 December, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-growing-power-and-a-growing-backlash-11576630800 (28 December 2022).

- Jackson Patrick Thaddeus. Civilizing the Enemy: German Reconstruction and the Invention of the West. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jakhar, Pratik (2019) ‘Confucius Institutes: The Growth of China’s Controversial Cultural Branch’, BBC News, 9 July, available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-49511231 (18 February, 2021).

- Jerdén Björn. The Assertive China Narrative: Why It Is Wrong and How So Many Still Bought into It. The Chinese Journal of International Politics. 2014;7(1):47–88. doi: 10.1093/cjip/pot019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keating Vincent Charles, Kaczmarska Katarzyna. Conservative Soft Power: Liberal Soft Power Bias and the ‘Hidden. Attraction of Russia’, Journal of International Relations and Development. 2019;22(1):1–27. doi: 10.1057/s41268-017-0100-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Taylor, Andrea and David Shullman (2018) ‘How Russia and China Undermine Democracy’, Foreign Affairs, 2 October, available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-10-02/how-russia-and-china-undermine-democracy (15 February, 2021).

- Kragh Martin, Åsberg Sebastian. Russia’s strategy for influence through public diplomacy and active measures: the Swedish case. Journal of Strategic Studies. 2017;40(6):773–816. doi: 10.1080/01402390.2016.1273830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krauthammer, Charles (1995) ‘Why We Must Contain China’, Time, 31 July, available at http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,983245,00.html (1 October, 2021).

- Krebs, Ronald R. (2015) Narrative and the Making of US National Security, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Krebs Ronald R, Jackson Patrick Thaddeus. Twisting Tongues and Twisting Arms. European Journal of International Relations. 2007;13(1):35–66. doi: 10.1177/1354066107074284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurlantzick, Joshua (2008) Charm Offensive. How China’s Soft Power is Transforming the World, New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

- Lawler, Dave (2019) ‘Russia and China form a front’, Axios, 1 June, available at https://www.axios.com/russia-china-security-threat-69567dd1-b618-4ef4-8852-4f09bb432327.html (15 February, 2021).

- Layne, Christopher (2010) ‘The Unbearable Lightness of Soft Power’ in Inderjeet Parmar and Michael Cox, eds, Soft Power and US Foreign Policy: Theoretical, Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, 51–82. London: Routledge.

- Layne Christopher. Preventing the China-US Cold War from Turning Hot. The Chinese Journal of International Politics. 2020;13(3):343–385. doi: 10.1093/cjip/poaa012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Eliza W. Y. United Front, Clientelism, and Indirect Rule: Theorizing the Role of the ‘Liaison Office’ in Hong Kong. Journal of Contemporary China. 2020;29(125):763–775. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2019.1704996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell Julia. Maoism: A Global History. London: The Bodley Head; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Nina (2021) ‘The American Victims of Washington’s Anti-China Hysteria’, New Republic, 20 May, available at https://newrepublic.com/article/162429/yellow-peril-rhetoric-selling-war-with-china (29 July, 2021).

- Mattis, Peter (2018) ‘Contrasting China’s and Russia’s Influence Operations’, War on the Rocks, 16 January, available at https://warontherocks.com/2018/01/contrasting-chinas-russias-influence-operations/ (15 February, 2021).

- McCourt, David M. (2022) ‘Knowledge Communities in US Foreign Policy Making: The American China Field and the End of Engagement with the PRC’, Security Studies: 1–41. 10.1080/09636412.2022.2133629.

- Mearsheimer John. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: W. W. Norton and Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mitzen Jennifer. Illusion or Intention? Talking Grand Strategy into Existence. Security Studies. 2015;24(1):61–94. doi: 10.1080/09636412.2015.1003724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray Michelle. The struggle for recognition in international relations: status, revisionism, and rising powers. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, Joseph S. (2013) ‘What China and Russia Don’t Get About Soft Power’, Foreign Policy 29(10) (17 October 2020).

- Nye, Joseph S. (2018) How Sharp Power Threatens Soft Power', Foreign Affairs, 2018, available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-01-24/how-sharp-power-threatens-soft-power (8 October, 2021).

- Nymalm Nicola. The Economics of Identity: Is China the New ‘Japan Problem’ for the United States? Journal of International Relations and Development. 2019;22(4):909–933. doi: 10.1057/s41268-017-0126-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, Robert C. (2020) Remarks delivered by National Security Advisor Robert C. O'Brien, The Arizona Commerce Authority in Phoenix, Arizona (06 June 2020) in Robert C. O'Brien, ed., Trump on China. Putting America First.