Abstract

Objectives

To characterize the prevalence, severity, correlation with initial symptoms, and role of vaccination in patients with COVID-19 with smell or taste alterations (STAs).

Methods

We conducted an observational study of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron admitted to three hospitals between May 17 and June 16, 2022. The olfactory and gustatory functions were evaluated using the taste and smell survey and the numerical visual analog scale at two time points.

Results

The T1 and T2 time point assessments were completed by 688 and 385 participants, respectively. The prevalence of STAs at two time points was 41.3% vs 42.6%. Furthermore, no difference existed in the severity distribution of taste and smell survey, smell, or taste visual analog scale scores between the groups. Patients with initial symptoms of headache (P = 0.03) and muscle pain (P = 0.04) were more likely to develop STAs, whereas higher education; three-dose vaccination; no symptoms yet; or initial symptoms of cough, throat discomfort, and fever demonstrated protective effects, and the results were statistically significant.

Conclusion

The prevalence of STAs did not decrease significantly during the Omicron dominance, but the severity was reduced, and vaccination demonstrated a protective effect. In addition, the findings suggest that the presence of STAs is likely to be an important indicator of viral invasion of the nervous system.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Olfactory and gustatory dysfunction, Anosmia, Dysgeusia

Introduction

The Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19, was first identified in late November 2021 and has since spread rapidly worldwide. To date, this variant remains the dominant variant in the global pandemic [1]. Since the pandemic outbreak, anosmia and dysgeusia have been shown to be key symptoms of the SARS-CoV-2 infection [2]. Some patients still have not recovered these senses almost a year later, and for a proportion of those who have, the sense of smell has been distorted [3]. The prevalence of olfactory dysfunction reported in previous studies ranged from 3.2% to 98.3% and that of gustatory dysfunction ranged from 5.6% to 62.7% in previous studies [4]. However, the few studies that used objective assessment methods demonstrated a higher prevalence than self-reported assessment methods [4]. Furthermore, within the respiratory tree, nasal epithelial cells display the highest expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor-angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 [5], and the virus may extend directly to the olfactory bulb through the nasal mucosa, indicating that the severity may be worse than believed. The wide variation in prevalence is related to the high heterogeneity in previous studies [6]; the actual prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction after acute infection is largely unclear. In addition, there has been a lack of investigation into the correlation between other symptoms and vaccine protection. With the increasing burden of people with chronic smell or taste dysfuncion [7] and with the potential correlation with nervous system damage in patients with COVID-19 [8], this is certainly becoming a significant health issue. Thus, more information on the olfactory and gustatory dysfunction after SARS-CoV-2 infection is urgently needed, especially in a vast number of patients with mild symptoms.

Our primary objective was to systematically and comprehensively characterize the prevalence, severity, correlation with initial symptoms, and the role of vaccination in patients with COVID-19 with smell or taste alterations (STAs) through a large cross-sectional survey.

Method

Study design and participants

We conducted an observational study of patients with mild SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants (aged ≥18 years) who were admitted to the No. 380 Changzhong Road mobile cabin hospital, the Fifth Middle School mobile cabin hospital, and the East Campus of the Middle School affiliated with Shanghai International Studies University mobile cabin hospital between May 17 and June 16, 2022. We assessed the olfactory and gustatory functions at two time points: any day of hospitalization with a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test (T1) and the day of discharge with a negative PCR test (T2). The participants volunteered to take the assessment at any point in time and completed a series of electronic questionnaires. Based on the survey results, we established a dataset on the health status of adults infected with SARS-CoV-2 and divided them into the STAs group and no smell and taste alterations (no-STAs) group to identify the risk and protective factors for these changes. In addition, we investigated the timing, severity, and characteristics of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in the STAs group. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Shanghai Fourth People's Hospital affiliated with Tongji University (2022061-001). Electronic informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Assessment of participants

Eligible participants were invited to complete an electronic questionnaire using a mini app under the guidance of trained clinicians. Information on age, sex, level of education, date of first positive antigen or PCR test result, initial symptom, vaccination status, the taste and smell survey (TSS), and numerical visual analog scale (VAS) was recorded. The T2 time point questionnaire included some of the same questions and an additional section on the days of hospitalization. The TSS is a 14-item validated questionnaire originally developed to evaluate chemosensory changes in patients infected with HIV [9] and has since been widely used to assess STAs in various types of patients [10,11]. These items require patients to indicate any self-perceived changes in their sense of smell or taste and assess whether they have noticed any changes in smell or the four main tastes (sweet, salty, bitter, and sour). Participants also expressed their perception of olfactory and gustatory changes separately using free descriptors and estimated the perceived intensity on the VAS from 0 (completely normal) to 10 (complete loss). Patients were divided into “STAs” and “no-STAs” groups according to their reports. Patients were categorized into the STAs group if they (i) responded positively to any of the four items with yes/no responses regarding taste or smell changes; (ii) indicated a change in intensity of any of the sensations of sweet, salty, bitter, and sour tastes and sense of smell; and (iii) reported any VAS score greater than zero. In addition, we graded the severity of the disease in the STAs group. Responses from the TSS can be used to generate a score from 0 to 16: 0-4 = no to mild STAs, 5-9 = moderate STAs, and 10-16 = severe STAs [11]. VAS assessment was stratified by a score of 0-3 as no to mild, 4-6 as moderate, and 7-10 as severe.

Outcomes

Our primary outcomes were the prevalence and severity of STAs, the effect of personal factors (age, sex, and education), correlation with initial symptoms after acute infection, and assessment of the impact of vaccination.

Our secondary outcomes were the time-of-onset distribution of STAs, characteristics of altered smell or taste, and length of hospitalization. The time-of-onset distribution was calculated between the date of completing the form and the date of the first positive antigen or PCR test result for patients at the T1 time point.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.3. Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]), whereas categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. For the comparison of continuous variables, Welch t-test and the Mann-Whitney U test were conducted, as appropriate. To compare categorical variables, we used the chi-square test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. To explore the association between taste and smell abnormalities and demographic and clinical characteristics, we used a multivariable adjusted logistic regression model. We used the “MASS” package of R to conduct stepwise regression of both directions and finally obtained a model with the smallest Akaike information criterion.

Results

A total of 688 and 385 participants completed T1 and T2 time point assessments respectively and were included in the final analysis. They were admitted to the mobile cabin hospital because of positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR results between May 17 and June 16, 2022. All participants completed reports through electronic questionnaires.

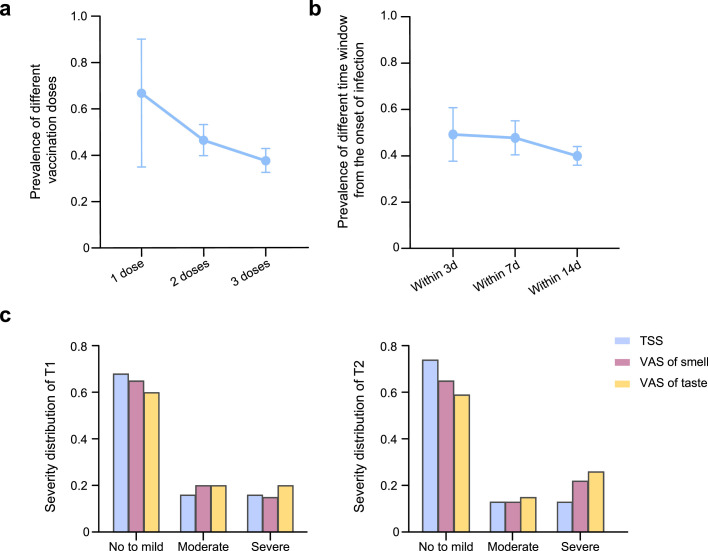

The demographic data and clinical features of the T1 time point group participants are summarized in Table 1 . The median age was 46 years (IQR, 32-58 years), the median duration of infection was 10 days (IQR, 7-13 days), and 308 were women (44.8%). The most frequently reported initial symptoms were fever (243 [35.3%]), headache (105 [15.3%]), cough (39 [5.7%]), and throat discomfort (35 [5.1%]); however, some patients were also temporarily asymptomatic (230 [33.4%]). In addition, the median length of hospitalization was 12 days (range, 10-16 days) according to the T2 time point data. A total of 613 patients in group T1 had received an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, and the prevalence in patients who had received different doses were as follows: one dose (66.7%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 34.9-90.1%), two doses (46.4%, 95% CI 39.8-53.2%), and three doses (37.5%, 95% CI 32.5-42.8%). With an increase in vaccine doses, the prevalence showed a downward trend (Figure 1 a). We calculated the time to the onset of olfactory and gustatory changes in the patients, and the prevalence of symptoms within 3 days from the onset of infection was 49.4% (95% CI 37.8-61.0%), with a gradual decrease thereafter (Figure 1b). We then compared the STAs between T1 and T2 (Table 2 ). The prevalence of STAs in the T1 group was 41.3% (95% CI 37.6-45.1%), which was not significantly different from that in the T2 group (42.6%, 95% CI 37.6-47.7%, P = 0.72). In addition, there was no difference in the severity distribution of TSS, smell, or taste VAS scores between the two time points (P = 0.22, P = 0.51, and P = 0.62, respectively), and most patients showed mild changes (Figure 1c).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features of T1 timepoint group participants.

| No. of patients | Prevalence, % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 46.0 (32.0-58.0) | .. |

| Days of the infection lasted, median (IQR), d | 10.0 (7.0-13.0) | .. |

| Sex, no. (%) | .. | .. |

| Male | 380 (55.2%) | 40.5 (35.5-45.7) |

| Female | 308 (44.8%) | 42.2 (36.6-47.9) |

| Education, no. (%) | .. | .. |

| College or higher | 211 (30.7%) | 31.8 (25.5-38.5) |

| High school or lower | 477 (69.3%) | 45.5 (41.0-50.1) |

| Initial symptom, no. (%) | .. | .. |

| None yet | 230 (33.4%) | 33.5 (27.4-40.0) |

| Fever | 243 (35.3%) | 44.9 (38.5-51.3) |

| Headaches | 105 (15.3%) | 51.4 (41.5-61.3) |

| Cough | 39 (5.7%) | 25.6 (13.0-42.1) |

| Throat discomfort | 35 (5.1%) | 31.4 (16.9-49.3) |

| Muscle pain | 7 (1.0%) | 85.7 (42.1-99.6) |

| Fatigue | 5 (0.7%) | 40.0 (5.3-85.3) |

| Smell or taste alteration | 15 (2.2%) | 73.3 (44.9-92.2) |

| Others | 9 (1.3%) | 44.4 (13.7-78.8) |

| Dose of vaccination, No./total (%) | .. | .. |

| One dose | 12/613 (2.0%) | 66.7 (34.9-90.1) |

| Two doses | 224/613 (36.5%) | 46.4 (39.8-53.2) |

| Three doses | 377/613 (61.5%) | 37.5 (32.5-42.8) |

Figure 1.

Prevalence and severity grading in different conditions.

(a) Among the 613 vaccinated patients, the prevalence of smell or taste alterations decreased with increasing number of vaccination doses. (b) Prevalence in different time windows from the onset of infection: within 3 days (49.4%, 95% CI 37.8-61.0%), within 7 days (47.9%, 95% CI 40.5-55.3%), and within 14 days (40.0%, 95% CI 36.0-44.1%). (c) No difference in the severity distribution of TSS, smell, or taste VAS scores was observed between the two timepoints, and most patients showed mild changes.

TSS, Taste and Smell Survey; VAS, visual analog scale.

Table 2.

Severity distribution of TSS, smell, or taste VAS assessment.

| T1 (n = 284) | T2 (n = 164) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (95% CI) | 41.3% (37.6%-45.1%) | 42.6% (37.6%-47.7%) | 0.72 |

| TSS severity, no. (%) | .. | .. | 0.22 |

| No to mild | 194 (68%) | 121 (74%) | .. |

| Moderate | 45 (16%) | 22 (13%) | .. |

| Severe | 45 (16%) | 21 (13%) | .. |

| VAS (Olfactory), no. (%) | .. | .. | 0.51 |

| No to mild | 185 (65%) | 107 (65%) | .. |

| Moderate | 57 (20%) | 21 (13%) | .. |

| Severe | 42 (15%) | 36 (22%) | .. |

| VAS (Gustatory), no. (%) | .. | .. | 0.62 |

| No to mild | 171 (60%) | 97 (59%) | .. |

| Moderate | 56 (20%) | 24 (15%) | .. |

| Severe | 57 (20%) | 43 (26%) | .. |

TSS, taste and smell survey; VAS, visual analog scale.

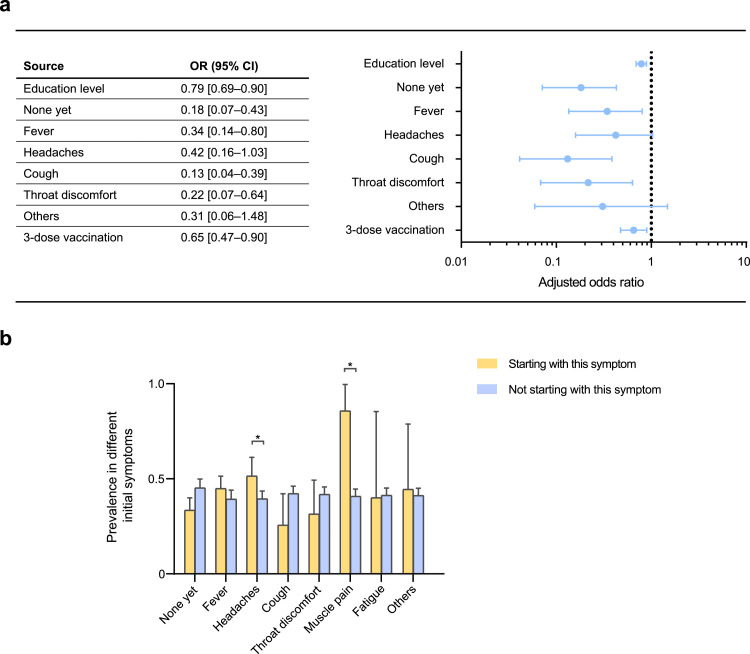

We then considered patients without STAs as controls, deriving an odds ratio (OR) to assess differences in the prevalence of various factors (Figure 2 a). Among all the factors assessed, we found that individuals with higher education (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.69-0.90); three-dose vaccination (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47-0.90); no symptoms yet (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.07-0.43); or initial symptoms of cough (OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.04-0.39), throat discomfort (OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.07-0.64), and fever (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.14-0.80) were significantly less prevalent. Moreover, there were significant differences in the education level (P = 0.001) and distribution of initial symptoms (P <0.001) between the two groups (Table 3 ). Therefore, we analyzed the prevalence according to different initial symptoms. The results demonstrated that the prevalence of olfactory and gustatory changes was significantly higher in patients with initial symptoms of headache (51.4% vs 39.5%, P = 0.03) and muscle pain (85.7% vs 40.8%, P = 0.04) than in those without such first symptoms (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Education, initial symptoms, vaccination in patients with altered taste and smell.

(a) Risk factors for altered smell or taste. (b) Prevalence of participants with different initial symptoms; and those who had headache (51.4% vs 39.5%, P = 0.03) and muscle pain (85.7% vs 40.8%, P = 0.04) as initial symptoms showed significantly higher prevalence.

Table 3.

Differences in demographic and clinical features between no-STAs and STAs participants.

| no-STAs (n = 404) | STAs (n = 284) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 46.0 (32.8- 59.0) | 46.0 (32.0-56.0) | 0.58 |

| Sex, no. (%) | .. | .. | 0.71 |

| Male | 226 (56%) | 154 (54%) | .. |

| Female | 178 (44%) | 130 (46%) | .. |

| Education, no. (%) | .. | .. | 0.001 |

| College or higher | 260 (64%) | 144 (76%) | .. |

| High school or lower | 217 (36%) | 67 (24%) | .. |

| Initial symptom, no. (%) | .. | .. | <0.001 |

| None yet | 153 (38%) | 77 (27%) | .. |

| Fever | 134 (33%) | 109 (38%) | .. |

| Headaches | 51 (23%) | 54 (19%) | .. |

| Cough | 29 (7%) | 10 (4%) | .. |

| Throat discomfort | 24 (6%) | 11 (4%) | .. |

| Muscle pain | 1 (0.2%) | 6 (2%) | .. |

| Fatigue | 3 (0.7%) | 2 (0.7%) | .. |

| Smell or taste alteration | 4 (1%) | 11 (4%) | .. |

| Others | 5 (1%) | 4 (1%) | .. |

| Days of the infection lasted, median (IQR), d | 11.0 (8.0-13.0) | 10.0 (6.0-13.0) | 0.58 |

| Dose of vaccination, median (IQR), No. | 3.0 (2.0-3.0) | 2.0 (2.0-3.0) | 0.08 |

STAs, smell or taste alterations.

Based on the findings, we also analyzed the characteristics of the patients’ STAs. Among patients with altered taste, the most common report was impairment of a single taste quality (40 [36.4%]), followed by impairment of all the four taste qualities (38 [34.5%], Supplementary Table 1), and the most frequently changed taste was salty (91 [82.7%]). The patients tended to become less sensitive, whether it was to the smell or any of the salty, sweet, sour, or bitter tastes (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the most detailed cross-sectional study of individuals with STAs after acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, systematically and comprehensively describing the epidemiological status and characteristics of olfactory and gustatory changes in these patients. The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction reported in previous studies varied widely depending on the assessment methods, variation in virus strains, and the population selected. However, a meta-analysis of 24 studies, including 8438 patients with COVID-19 from 13 countries, showed that the pooled proportions of patients presenting with olfactory and gustatory dysfunction were 41.0% and 38.2%, respectively, which is very similar to our results [4]. In addition, as reported in previous studies, although STAs are rarely reported as the initial symptoms, most patients develop these symptoms in the early stages of infection [12]. A recent study showed that the loss of smell was less common in participants infected during Omicron prevalence than during Delta prevalence [13], which may be related to the fact that a simple self-reporting method would yield a lower prevalence [4]. However, the Omicron variant showed a milder severity than the epidemic in 2020, when more than half of the patients had anosmia or severe olfactory impairment.

We did not observe that the prevalence of STAs was significantly affected by sex or age nor did it affect the length of hospitalization. However, higher education status and three vaccination doses presented significant protective effects. Educational attainment is known to be consistently and significantly associated with individual health outcomes and risks, possibly because well-educated individuals have a higher sense of personal control and lower levels of emotional or physical distress [14]. In addition, despite the increased incidence of Omicron variant breakthrough infections and reduction in the protective effect of the vaccine [15,16], our data show that three-dose vaccination can still significantly reduce the occurrence of STAs, and with increasing doses of vaccination, the prevalence tends to decrease.

One surprising finding of our study is that there seems to be a specific association between the initial symptoms after acute infection and changes in smell or taste. Among the first symptoms collected, we found that patients with cough, throat discomfort, or fever as their initial symptoms were significantly less likely to have STAs. However, patients with headaches as their initial symptom were more likely to have an altered taste and smell. This was in accordance with a previous study in which more individuals in the headache group of patients with COVID-19 had dysosmia [17]. The mechanism for this discrepancy is largely unclear, and we suspect that this is because patients with cough, throat discomfort, and fever as their initial symptoms are more likely to experience an invasion of the respiratory system through the pharynx, resulting in an infection after exposure to SARS-CoV-2, whereas patients with headache as their initial symptom may experience more viral invasion into the nervous system [18,19]. In addition to affecting the respiratory tract, SARS-CoV-2 invades various other organs, including the nervous system [20]. Within the respiratory tree, nasal epithelial cells have the highest expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 [21], and it is hypothesized that the virus extends directly to the olfactory bulb through the nasal mucosa [22]. Although SARS-CoV-2-related olfactory dysfunction may involve non-neuronal cell impairment instead of direct involvement with olfactory sensory neurons [23,24], the participation of non-neural structures may worsen the signals from olfactory neurons and lead to neuroinflammatory responses in the brain [25]. In addition, cellular deficits that may contribute to lasting neurological symptoms were identified in a mouse model of infection induced by intranasal injection of SARS-CoV-2 [26], and there was a significant tissue damage in regions that were functionally connected to the primary olfactory cortex in the brain of patients with COVID-19 [8]. These pieces of evidence suggest that altered olfaction and gustation may be valid indications of SARS-CoV-2 invading the nervous system through the nasal cavity [25].

The genome of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron has a large number of deletions and mutations compared with the original sequence [27], which are known to increase transmissibility [28]. However, the effects of most other Omicron mutations remain unclear. Although the Omicron variant has been reported to be less severe [29], the huge patient base resulting from its high contagiousness will expose more people to complications and sequelae, including olfactory and gustatory dysfunction, and still requires public health attention. Moreover, the consideration of STAs as part of the screening and diagnostic approaches for COVID-19 could help improve the early detection rate of cases and further curtail the spread of the virus. Notably, owing to the high heterogeneity of studies on olfactory and gustatory dysfunction after SARS-CoV-2 infection, a difference in prevalence was observed, which has blurred our understanding of it. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop norms to reduce heterogeneity among studies, such as validated assessment tools, broadly recognized symptom questionnaires, and specific follow-up time points.

The strengths of our study lie in the large sample size, comprehensive information collection, recognized disease severity groupings, and improved assessment methods to help understand the epidemiology of STAs in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in multiple ways. Through the combination of TSS and VAS, we comprehensively evaluated the changes in quality (distortion of smell or taste) and quantity (alteration in the strength of smell or taste), respectively [30]. We tried to avoid discrepancies in survey results by using simple “yes” or “no” self-reports because most patients are not aware of their dysfunction before testing [31].

Our study had several limitations. First, our study was conducted on patients with mild illness in mobile cabin hospitals, which limits the generalizability of the study findings of this particular population to severe patients. Second, despite the combination of the two assessment methods, our study may still have not been able to achieve the accuracy of objective assessment methods. According to statistics, most studies on olfactory and gustatory dysfunction have conducted self-rating assessments, and only a few studies have assessed smell and taste in patients with COVID-19 with psychophysical tests, which is one of the reasons for the high variability in the prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction [32]. Owing to practical constraints, the assessment method we finally adapted was still essentially subjective self-reporting, which may be biased to some degree owing to sociocultural factors and other reasons [33]. For greater objectivity, we may need to apply psychophysical assessment methods for further research in the future. Third, we did not track the complete progression of symptoms for each patient from admission to discharge, which prevented us from accurately assessing the short-term outcomes of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction. Fourth, this study was based on a cross-sectional survey, which was geographically limited and had no data on the follow-up process of the disease.

The prevalence of STAs in mild patients after acute SARS-CoV-2 infection did not significantly decrease because of infection with the Omicron variant, but the severity was reduced, whereas the vaccine demonstrated its protective effect. Patients with STAs did not recover significantly when they were discharged; therefore, we plan to conduct continuous follow-ups in this cohort to characterize the outcomes and long-term effects. In addition, the appearance of altered smell or taste is likely to be an important indication of viral invasion into the nervous system, and the possibility of early intervention to reduce the prevalence and protect neurological function needs to be further explored.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Medical Key Specialties Construction Plan (grant number: ZK2019B13), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 82271223); the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (grant number: 20ZR1442900); and the Shanghai Fourth People's Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University (grant numbers: sykyqd01901, SY-XKZT-2021-2001).

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Shanghai Fourth People's Hospital, affiliated with Tongji University (2022061-001). The study was registered at the China Clinical Trials Registration Center (ChiCTR2200060074).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all the participants and authors. This study was supported by the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai, and the Shanghai Fourth People's Hospital affiliated with Tongji University School of Medicine.

Author contributions

Lize X, Cheng L, and Yingna T were responsible for funding acquisition. Jian S, Qi J, and Enzhao Z were responsible for the formal analysis. Enzhao Z and Zisheng A did data curation. Lize X, Yingna T, Qidong L, Miaomiao F, Hui Z, Guanghui A, Silu C, Jian S, Guanghui X, and Yi L were responsible for resources. Qidong L, Miaomiao F, Hui Z, Guanghui A, Silu C, and Jinxuan T verified the underlying data. Qi J, Jian S, Enzhao Z, and Cheng L wrote the original draft. All authors contributed to the review and editing. All authors had access to all data in the study and the corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2023.01.017.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19—17-august-2022; 2022 [accessed 20 August 2022].

- 2.Spinato G, Fabbris C, Polesel J, Cazzador D, Borsetto D, Hopkins C, et al. Alterations in smell or taste in mildly symptomatic outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. 2020;323:2089–2090. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall M. COVID's toll on smell and taste: what scientists do and don't know. Nature. 2021;589:342–343. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agyeman AA, Chin KL, Landersdorfer CB, Liew D, Ofori-Asenso R. Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95:1621–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sungnak W, Huang N, Bécavin C, Berg M, Queen R, Litvinukova M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med. 2020;26:681–687. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0868-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Izquierdo-Dominguez A, Rojas-Lechuga MJ, Mullol J, Alobid I. Olfactory dysfunction in the COVID-19 outbreak. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2020;30:317–326. doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pence TS, Reiter ER, DiNardo LJ, Costanzo RM. Risk factors for hazardous events in olfactory-impaired patients. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:951–955. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douaud G, Lee S, Alfaro-Almagro F, Arthofer C, Wang C, McCarthy P, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature. 2022;604:697–707. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04569-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heald AE, Pieper CF, Schiffman SS. Taste and smell complaints in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1998;12:1667–1674. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabadi A, Saadi M, Schey R, Parkman HP. Taste and smell disturbances in patients with gastroparesis and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:370–377. doi: 10.5056/jnm16132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGreevy J, Orrevall Y, Belqaid K, Wismer W, Tishelman C, Bernhardson BM. Characteristics of taste and smell alterations reported by patients after starting treatment for lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2635–2644. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re'em Y, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalmedicine. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menni C, Valdes AM, Polidori L, Antonelli M, Penamakuri S, Nogal A, et al. Symptom prevalence, duration, and risk of hospital admission in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 during periods of omicron and delta variant dominance: a prospective observational study from the ZOE COVID Study. Lancet. 2022;399:1618–1624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00327-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross CE, Van Willigen M. Education and the subjective quality of life. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:275–297. doi: 10.2307/2955371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accorsi EK, Britton A, Fleming-Dutra KE, Smith ZR, Shang N, Derado G, et al. Association between 3 doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and symptomatic infection caused by the SARS-CoV-2 omicron and delta variants. JAMA. 2022;327:639–651. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhlmann C, Mayer CK, Claassen M, Maponga T, Burgers WA, Keeton R, et al. Breakthrough infections with SARS-CoV-2 omicron despite mRNA vaccine booster dose. Lancet. 2022;399:625–626. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caronna E, Ballvé A, Llauradó A, Gallardo VJ, Ariton DM, Lallana S, et al. Headache: a striking prodromal and persistent symptom, predictive of COVID-19 clinical evolution. Cephalalgia. 2020;40:1410–1421. doi: 10.1177/0333102420965157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bobker SM, Robbins MS. COVID-19 and headache: a primer for trainees. Headache. 2020;60:1806–1811. doi: 10.1111/head.13884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sampaio Rocha-Filho PA, Voss L. Persistent headache and persistent anosmia associated with COVID-19. Headache. 2020;60:1797–1799. doi: 10.1111/head.13941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sungnak W, Huang N, Bécavin C, Berg M, Lung Biological Network HCA. SARS-CoV-2 entry genes are most highly expressed in nasal goblet and ciliated cells within human airways. Arxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaye R, Chang CWD, Kazahaya K, Brereton J, Denneny JC., 3rd COVID-19 anosmia reporting tool: initial findings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163:132–134. doi: 10.1177/0194599820922992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brann DH, Tsukahara T, Weinreb C, Lipovsek M, Van den Berge K, Gong B, et al. Non-neuronal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated anosmia. Sci Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan M, Yoo SJ, Clijsters M, Backaert W, Vanstapel A, Speleman K, et al. Visualizing in deceased COVID-19 patients how SARS-CoV-2 attacks the respiratory and olfactory mucosae but spares the olfactory bulb. Cell. 2021;184:5932–5949. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.10.027. e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meinhardt J, Radke J, Dittmayer C, Franz J, Thomas C, Mothes R, et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24:168–175. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernández-Castañeda A, Lu P, Geraghty AC, Song E, Lee MH, Wood J, et al. Mild respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection can cause multi-lineage cellular dysregulation and myelin loss in the brain. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.01.07.475453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karim SSA, Karim QA. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: a new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:2126–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02758-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Araf Y, Akter F, Tang YD, Fatemi R, Parvez MSA, Zheng C, et al. Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: genomics, transmissibility, and responses to current COVID-19 vaccines. J Med Virol. 2022;94:1825–1832. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang L, Li X, Gu X, Zhang H, Ren L, Guo L, et al. Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10:863–876. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00126-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hummel T, Whitcroft KL, Andrews P, Altundag A, Cinghi C, Costanzo RM, et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction. Rhin. 2016;54:1–30. doi: 10.4193/Rhino16.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moein ST, Hashemian SM, Mansourafshar B, Khorram-Tousi A, Tabarsi P, Doty RL. Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10:944–950. doi: 10.1002/alr.22587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trecca EMC, Cassano M, Longo F, Petrone P, Miani C, Hummel T, et al. Results from psychophysical tests of smell and taste during the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a review. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2022;42:S20–S35. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-suppl.1-42-2022-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trecca EMC, Fortunato F, Gelardi M, Petrone P, Cassano M. Development of a questionnaire to investigate socio-cultural differences in the perception of smell, taste and flavour. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2021;41:336–347. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-N0766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.