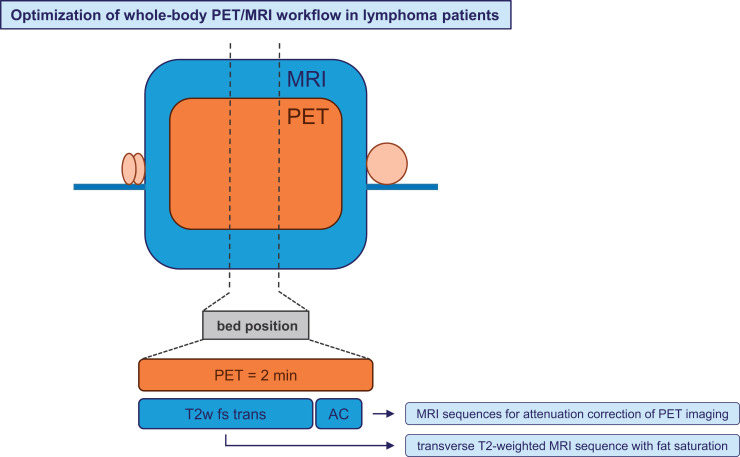

Visual Abstract

Keywords: PET/MRI, MRI sequences, Hodgkin lymphoma, whole-body imaging

Abstract

18F-FDG PET/MRI might be the diagnostic method of choice for Hodgkin lymphoma patients, as it combines significant metabolic information from PET with excellent soft-tissue contrast from MRI and avoids radiation exposure from CT. However, a major issue is longer examination times than for PET/CT, especially for younger children needing anesthesia. Thus, a targeted selection of suitable whole-body MRI sequences is important to optimize the PET/MRI workflow. Methods: The initial PET/MRI scans of 84 EuroNet-PHL-C2 study patients from 13 international PET centers were evaluated. In each available MRI sequence, 5 PET-positive lymph nodes were assessed. If extranodal involvement occurred, 2 splenic lesions, 2 skeletal lesions, and 2 lung lesions were also assessed. A detection rate was calculated dividing the number of visible, anatomically assignable, and measurable lesions in the respective MRI sequence by the total number of lesions. Results: Relaxation time–weighted (T2w) transverse sequences with fat saturation (fs) yielded the best result, with detection rates of 95% for nodal lesions, 62% for splenic lesions, 94% for skeletal lesions, and 83% for lung lesions, followed by T2w transverse sequences without fs (86%, 49%, 16%, and 59%, respectively) and longitudinal relaxation time–weighted contrast-enhanced transverse sequences with fs (74%, 35%, 57%, and 55%, respectively). Conclusion: T2w transverse sequences with fs yielded the highest detection rates and are well suited for accurate whole-body PET/MRI in lymphoma patients. There is no evidence to recommend the use of contrast agents.

For lymphoma patients, 18F-FDG PET/MRI might be the diagnostic method of choice (1,2), as it combines significant metabolic information from PET with excellent soft-tissue contrast from MRI and avoids radiation exposure from CT (3,4). Using PET/MRI, a reduction in the radiation dose from diagnostic imaging and, hence, a reduction in the risk of potential negative radiation effects can be achieved, particularly in pediatric patients needing several examinations (5,6).

Examination time plays an important role in whole-body PET/MRI. Regionalized MRI sequences may provide excellent resolution and tissue contrast, among other desired features, but are typically rather time-consuming. Longer examination times may decrease compliance and will call for a higher amount of anesthetics in younger children (7,8). The application of suitable whole-body MRI sequences hence represents a trade-off between imaging quality and examination time.

Ten years after introduction into clinical routine, PET/MRI systems are established and different imaging protocols have been developed for the same indication over time (9).

The EuroNet-PHL-C2 (C2) study (10) was an international multicenter treatment optimization trial for pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma patients of all stages. PET/MRI was the preferred option for whole-body imaging in the C2 study, if locally available. Within the C2 study, central reference reading of all imaging data was mandatory. Imaging data were stored on a central server of the Pediatric Hodgkin Network (11), enabling comparison of PET/MRI scans from different centers.

Using PET/MRI instead of PET/CT, MRI has to perform at least equivalently to CT. First, lymphoma lesions must be visible in the respective MRI sequence; that is, sufficient image resolution and sufficient contrast to background need to be ensured. Second, lesions need to be anatomically assignable to the different body regions for staging and radiation therapy planning (12). Third, an exact size measurement of lesions must be possible for staging (13) and response assessment (14).

The aim of our study was to identify the most suitable whole-body MRI sequence for pretreatment PET/MRI. Therefore, all available MRI sequences were assessed in terms of detection, anatomic assignment, and size measurement of lymphoma lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

C2 study patients (EudraCT number NCT02684708) with a pretreatment PET/MRI scan acquired between October 2015 and December 2019 were included in our study. A total of 13 study centers performed PET/MRI. Ten patients per center were assessed in our evaluation.

C2 study patients or their guardians gave written informed consent and acknowledged the evaluation of imaging data for research purposes. The ethics committee of the University of Leipzig approved this retrospective study, and the requirement to obtain additional informed consent was waived.

Imaging Protocol for C2 Study Patients

For staging of C2 study patients, a whole-body PET/MRI or PET/CT scan ranging from skull base to mid thigh, a chest CT in end inspiration for lung assessment, and an abdominal ultrasound for liver and spleen assessment were required. All imaging had to be performed according to the C2 trial recommendations, which nevertheless allowed a variance in chosen sequences and imaging parameters according to local standards.

Assessment

PET/MRI scans were assessed in random order by a radiologist and a nuclear physician, both of whom were experienced in lymphoma assessment, with 15 y and 10 y of expertise, respectively. Decisions were made by consensus.

For each scan, the PET/MRI device and software data, patient data, and examination parameters were recorded. The Hermes 3-dimensional viewer (version 2.2.0.104) was used for PET/MRI assessment.

MRI Sequences

All available MRI sequences in coronal or transverse orientation were analyzed. Each MRI sequence was assigned to one of the following sequence categories: longitudinal relaxation time–weighted (T1w) with contrast enhancement (ce) and fat saturation (fs), T1w without ce and with fs, T1w without ce or fs (nonfs), transverse relaxation time–weighted (T2w) with fs, T2w nonfs, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), Dixon in-phase, Dixon out-of-phase, Dixon relative water fraction, and Dixon relative fat fraction. Each category was subdivided into transverse and coronal orientations.

The Dixon sequences were based mainly on a T1w 3-dimensional turbo multigradient echo sequence.

Evaluation of Lymphoma Lesions

The reference in our study was PET-positive lymphoma lesions (15). To exclude false-positive lesions, only PET-positive lesions confirmed by the central review board of the C2 study were considered for evaluation.

To avoid overemphasizing patients with extensive lymphoma involvement, we decided to limit the number of reference lesions. Five lymph nodes and 2 extranodal lesions per organ (spleen, skeleton, and lung) were assessed per patient. Reference lesions had to be between 0.5 and 2.0 cm in diameter. This range was chosen since lymph nodes smaller than 0.5 cm are not considered in any staging protocol and are difficult to identify with PET and MRI. On the other hand, lymphoma lesions larger than 2.0 cm are well detectable, even in less-suited MRI sequences.

The reference lesions were assessed if they were visible, anatomically assignable, and measurable in the respective MRI sequence. Visibility was defined as sufficient image resolution and sufficient lesion-to-background contrast for lesion detection. Anatomic assignment meant that body region boundaries were visible and that lymphoma lesions could clearly be assigned to a specific body region; for example, the clavicle was visible for differentiation between supraclavicular and infraclavicular lymph nodes. Measurable meant that reference lesions could be delineated for exact size measurement in 2 perpendicular planes.

For each MRI sequence, a detection rate was calculated, dividing the number of visible, assignable, and measurable lesions by the total number of lesions.

For lung assessment, 2 different conditions were applied. Reference lesions were lymphoma lesions detected on chest CT in end inspiration and had to be between 0.2 and 1.0 cm in diameter. These conditions were chosen since lung involvement in the C2 study was defined as at least 3 lung lesions of 0.2 cm or larger in diameter detected on CT.

To estimate the influence of artifacts on lung assessment, MRI sequences were assessed for false-positive lung lesions. Lesions visible on MRI without a correlate on CT were considered false-positive.

RESULTS

Patient Data

In total, 210 C2 study patients from 13 PET centers underwent pretreatment PET/MRI between October 2015 and December 2019. The number assessed in our study was 84, that is, up to 10 patients per center. The number of PET-positive lymph node lesions analyzed was 390. Sixty-six patients had extranodal involvement; splenic, skeletal, and lung lesions were seen in 42, 23, and 32 patients, respectively. We assessed 76 splenic, 44 skeletal, and 61 lung lesions (Figs. 1 and 2).

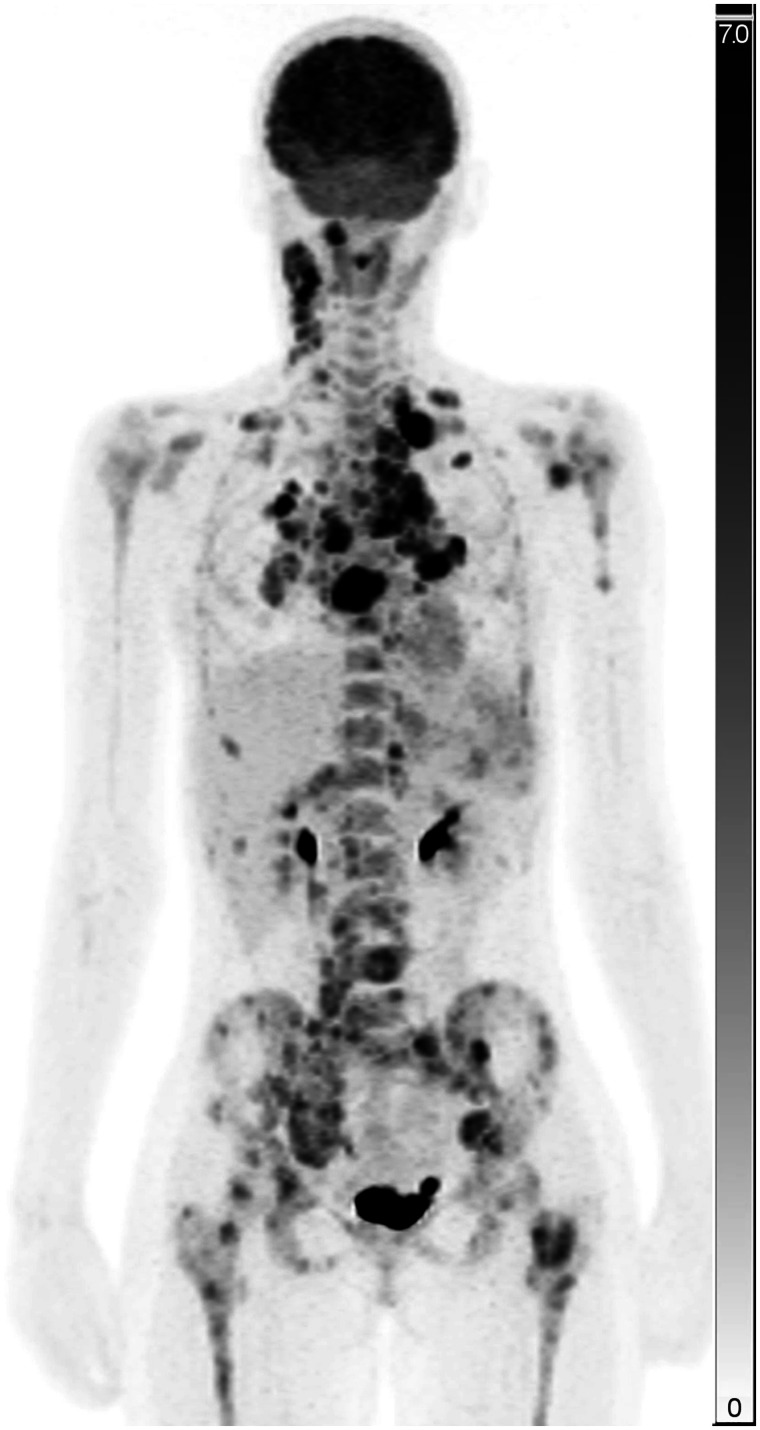

FIGURE 1.

Maximum-intensity projection of PET image of study patient with nodal, splenic, skeletal, and lung lesions. Scale bars represent SUV (unitless).

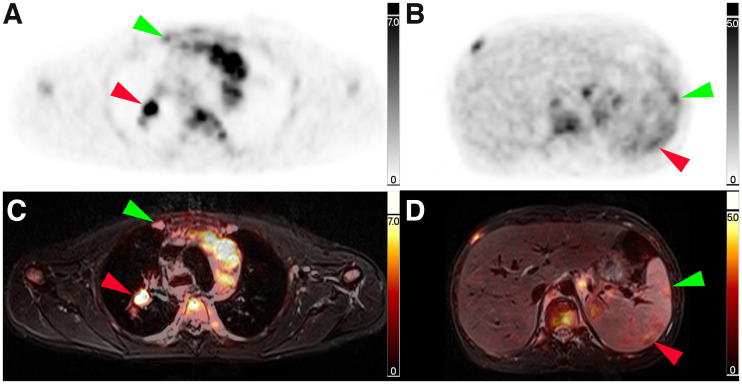

FIGURE 2.

Corresponding transverse slice positions of PET and PET/MRI. (A and C) Transverse thoracic slice with PET-positive right-sided internal mammary lymph node (green arrow) and PET-positive right-sided hilar lymph node (red arrow). (B and D) Transverse abdominal slice with 2 PET-positive splenic lesions (green and red arrow).

All 13 study centers conducted the examinations on dedicated 3-T PET/MRI scanners. Eleven centers used a Biograph mMR scanner (Siemens Healthineers); one center, a Signa PET/MR scanner (GE Healthcare); and one center, an Ingenuity TF PET/MR scanner (Philips Healthcare).

The mean and the median examination times for a PET/MRI scan ranging from skull base to mid thigh were 47 min (±18 min) and 44 min, respectively.

On average, 8 different MRI sequences were available per patient (Supplemental Table 1; supplemental materials are available at http://jnm.snmjournals.org).

Lymph Node Involvement

T2w fs transverse sequences yielded the best result of all MRI sequence categories for the detection of lymph node lesions, with a detection rate of 95% (155/164), followed by T2w nonfs transverse sequences (186/217, or 86%), T1w ce fs transverse sequences (126/171, or 74%), and T2w fs coronal sequences (111/201, or 55%) (Table 1; Fig. 3).

TABLE 1.

Detection Rates of MRI Sequence Categories for Lymphatic, Splenic, Skeletal, and Lung Lesions

| Sequence category | Orientation | Lymph nodes | Spleen | Skeleton | Lung |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2w fs | Transverse | 95% | 62% | 94% | 83% |

| T2w nonfs | Transverse | 86% | 49% | 16% | 59% |

| T1w ce fs | Transverse | 74% | 35% | 57% | 55% |

| T2w fs | Coronal | 55% | 24% | 93% | 50% |

| T1w without ce nonfs | Coronal | 47% | 33% | 25% | 14% |

| Dixon out-of-phase | Transverse | 42% | 0% | 16% | 56% |

| Dixon relative water fraction | Transverse | 42% | 7% | 33% | 49% |

| Dixon in-phase | Transverse | 35% | 5% | 8% | 43% |

| DWI | Transverse | 34% | 37% | 71% | 33% |

| T1w without ce fs | Transverse | 34% | 50% | 25% | 56% |

| T1w ce fs | Coronal | 29% | 0% | — | 100% |

| Dixon relative fat fraction | Transverse | 23% | 0% | 7% | 8% |

| Dixon relative water fraction | Coronal | 19% | 0% | 14% | 21% |

| Dixon relative fat fraction | Coronal | 13% | 0% | 0% | 5% |

| T1w without ce nonfs | Transverse | 12% | 7% | 50% | — |

| Dixon out-of-phase | Coronal | 11% | 0% | 4% | 22% |

| Dixon in-phase | Coronal | 9% | 9% | 5% | 24% |

| T2w nonfs | Coronal | 0% | 27% | 0% | 100% |

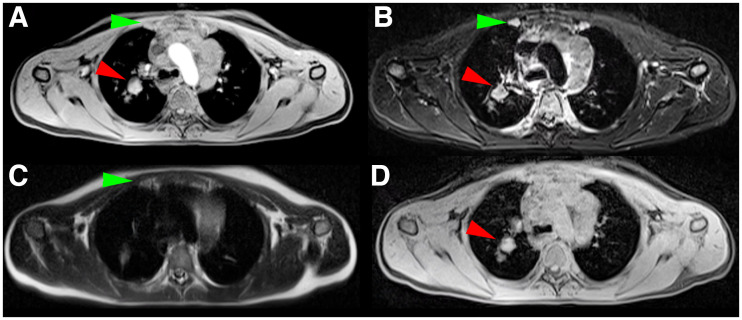

FIGURE 3.

Identical transverse slice positions of different MRI sequences (same slice position as in Figs. 2A and 2C). (A) T1w MRI sequence with ce. (B) T2w MRI sequence with fs. (C) T2w nonfs MRI sequence. (D) Dixon relative water fraction distribution. PET-positive right-sided internal mammary lymph node (green arrow) is visible in A, B, and C. PET-positive right-sided hilar lymph node (red arrow) is visible in A, B, and D.

Regarding the MRI sequence level, the T2w TSE fs transverse sequence achieved detection rates above 90% in all 6 centers performing this sequence. Overall, 145 of 150 lesions (97%) were visible, assignable, and measurable. The second best result was seen for the T2w half-Fourier single-shot turbo spin-echo nonfs transverse sequence, with detection rates above 90% in 6 of 8 centers as well as rates of 80% and 62% in the other 2 centers. Overall, 186 of 217 lesions (86%) were visible, assignable, and measurable.

Extranodal Involvement

The highest detection rate for splenic lesions was observed for T2w fs transverse sequences, at 62% (23/37), followed by T2w nonfs transverse sequences (25/51, or 49%) and DWI transverse sequences (10/27, or 37%) (Table 1; Fig. 4).

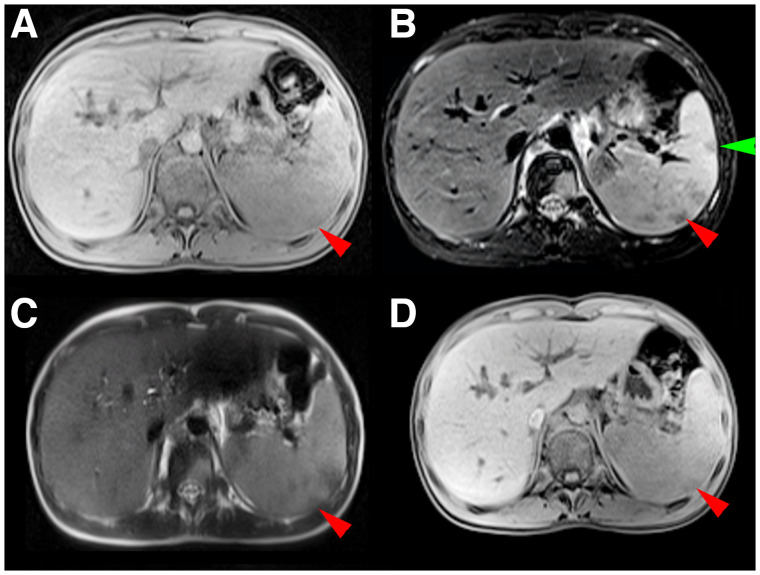

FIGURE 4.

Identical transverse slice positions of different MRI sequences (same slice position as in Figs. 2B and 2D). (A) T1w MRI sequence with ce. (B) T2w MRI sequence with fs. (C) T2w nonfs MRI sequence. (D) Dixon relative water fraction distribution. Dorsal splenic lesion (red arrow) is visible in A–D; ventral lesion, only in B (green arrow).

For skeletal lesions, the highest detection rate was seen for T2w fs transverse sequences, at 94% (17/18), followed by T2w fs coronal sequences (26/28, or 93%) and DWI transverse sequences (10/14, or 71%). T2w nonfs transverse sequences yielded a detection rate of only 16% (6/38) (Table 1).

All lung lesions were detected in T2w nonfs coronal sequences (5/5) and T1w ce fs coronal sequences (8/8). However, the small number of lesions in both sequences limits the meaningfulness of this result. The next-best ratios were seen for T2w fs transverse sequences (19/23, or 83%) and T2w nonfs transverse sequences (30/51, or 59%) (Table 1; Supplemental Fig. 1). False-positive lung lesions were seen in most MRI sequences. T2w fs transverse and T2w nonfs transverse sequences demonstrated false-positive lung lesions in 10 of 12 and 18 of 27 patients, respectively. Only 4 MRI sequence categories were free of false-positive lung lesions: DWI transverse, T1w ce fs coronal, T2w fs coronal, and T2w nonfs coronal.

Overall, the highest detection rates were achieved by T2w fs transverse sequences, at 95%, 62%, 94%, and 83% for lymphatic, splenic, skeletal, and lung lesions, respectively. In this sequence, 18 of the 242 lesions assessed were not visible (2 lymphatic, 12 splenic, and 4 lung lesions). Twelve of these 18 lesions were also not visible in any other MRI sequence. Six lesions (2 lymphatic, 2 splenic, and 2 lung lesions) were visible in at least one other sequence.

The next best sequences were T2w nonfs transverse (86%, 49%, 16%, and 59%, respectively) and T1w ce fs transverse (74%, 35%, 57%, and 55%, respectively). The best coronal sequence was a T2w fs sequence, with detection rates of 55%, 24%, 93%, and 50%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The PET/MRI examination time in pediatric patients should be as short as reasonably achievable to decrease anesthesia time in younger children (16) and increase compliance in adolescents. On the other hand, MRI sequences need to provide all information for a qualified assessment (17,18).

Whole-body PET/MRI is well suited for a fast overview, as would be used, for example, in lymphoma patients or in the search for an inflammation focus. The full potential of MRI is far from being exhausted in this procedure, but regionalized MRI sequences on individual body parts are time-consuming. Whole-body PET/MRI is a compromise between short examination time and adequate image quality.

In our study, the mean examination time for a PET/MRI scan ranging from skull base to mid thigh was 47 min, and examination times of more than 1 h were not uncommon. Faster PET acquisition protocols reporting a duration of 2 min per bed position have been published (19,20). Thus, a purposeful choice of MRI sequences is important to decrease PET/MRI examination time.

In our study, the optimal whole-body MRI sequence category for PET/MRI were T2w fs transverse sequences. Almost all lymphatic, skeletal, and lung lesions were visible, assignable, and measurable. Splenic lesions had a moderate detection rate of 62%, which was, however, the best result of all MRI sequences available in our study. T2w fs transverse sequences were performed in only 7 of the 13 centers participating in our study. The second best result was seen for T2w nonfs transverse sequences. The good performance of T2w transverse sequences in whole-body PET/MRI is in line with published results (3,16,19). However, an issue with T2w transverse sequences was the high false-positive rate of lung lesions, influencing the accuracy of lung evaluation.

In our study, T1w sequences applied after contrast agent administration were not on a par with T2w sequences. Similar findings were also reported by other research groups (21,22). Considering potential side effects of MRI contrast agents (23,24), we cannot unreservedly recommend their use in pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma patients.

Attenuation correction is mandatory for PET imaging and usually done with Dixon sequences, initially providing in-phase and out-of-phase images as well as allowing calculation of distributions of relative water and fat fractions (25,26). One could argue for the use of only Dixon sequences for whole-body MRI in lymphoma patients. However, in our study, Dixon sequences were less suitable for the detection of lymphoma lesions and clearly inferior to T2w sequences.

The detection rate of transverse DWI sequences was only 34%. DWI relies on detection of the random brownian motion of water molecules in the respective tissues (27). The assessment of DWI in our study probably underestimates their true potential since anatomic boundaries and morphologic landmarks are hardly visible in DWI. Thus, despite their potential to provide additional information for lesion staging, DWI sequences are not suitable for anatomic assignment of lymphoma lesions. This is a main reason for the low detection rate of DWI sequences in our study; 68% of all PET-positive lesions were visible using DWI technique, which is in line with previously reported rates of between 62% and 77% (2,9,28). This result might be ascribed to the fact that PET and DWI do not depict the same pathologic mechanism (29,30).

T2w fs transverse sequences and MRI sequences for attenuation correction of PET imaging together can be acquired within the 2 min required for PET imaging per bed position. Thus, a PET/MRI examination from skull base to mid thigh in less than 20 min is possible. Compared with the average examination time of 47 min in our study patients, this is significantly less than half.

Almost all coronal sequences yielded lower detection rates than the corresponding transverse sequences. Thus, transverse sequences seem to be more suitable for whole-body cross-sectional image assessment. However, the viewing habits of the readers could also have influenced our results.

Splenic involvement was difficult to assess on MRI, with best detection rates being slightly above 60%, achieved with T2w fs sequences. Detection of splenic lesions with whole-body MRI sequences is known to be challenging, with reported sensitivities ranging between 57% and 86% (31,32). This challenge might be ascribed to artifacts due to breathing or cardiac motion or anisotropic physiologically restricted diffusion patterns of normal splenic parenchyma in DWI (33). The additional application of spleen-specific MRI sequences might be beneficial in lymphoma patients with suspected splenic involvement. The detection of splenic lesions on CT is challenging as well, with published sensitivities and specificities of 33%–94% and 0%–100%, respectively (34,35). Ultrasound is a sensitive method for the detection of splenic involvement (36). However, the quality of ultrasound examinations is physician-dependent, and central reference evaluation is not possible.

Skeletal lesions were well detectable in T2w fs sequences, in both transverse and coronal orientations. These results are in line with published data (37,38). T2w nonfs transverse sequences showed a low detection rate of only 16%. An explanation could be the increasing fat signal in the bone marrow of adolescents. Thus, edemalike bone marrow changes, as a sign of skeletal involvement, might be masked by a hyperintense fat signal.

Detection of lung lesions in whole-body MRI is challenging (3,39). Although good detection rates were observed for 2 coronal sequences and 1 transverse MRI sequence, false-positive lung lesions were a main issue in most sequences. One reason might be artifacts due to cardiac or respiratory motion (40). Another reason is that even small lesions of 0.2 cm were considered as lung involvement. Such small lesions are difficult to detect on MRI. CT is the gold standard for lung evaluation (41). However, lung-specific MRI sequences have shown promising results (42).

Our study had some limitations. T2w fs transverse sequences yielded the best results of all sequences in our study. However, 7% (18/242) of all lesions—mainly splenic lesions—were not visible. Six of these 18 lesions were visible in at least one other MRI sequence.

Most study centers used a PET/MRI scanner from one vendor, which might bias our results in terms of the vendor-specific scanner properties and sequences.

Another limitation is the lack of information on false-positive lesions on MRI. Theoretically, MRI sequences with good detection rates could compromise their performance by an increased rate of false-positive lesions. This effect was observed for T2w transverse sequences in lung assessment.

CONCLUSION

T2w fs transverse sequences yielded the highest detection rates and are well suited for accurate whole-body PET/MRI in lymphoma patients. There is no evidence to recommend the use of contrast agents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients and their families who participated in the C2 trial and all recruiting physicians and participating centers for providing the PET/MRI data of their patients.

DISCLOSURE

Our study was supported by grants from the foundation “Mitteldeutsche Kinderkrebsforschung.” Martin Hüllner received grants from GE Healthcare, from the Alfred and Annemarie von Sick Legacy for Translational and Clinical Cardiac and Oncologic Research, and from the Clinical Research Priority Program (CRRP) “Artificial Intelligence in Oncologic Imaging” of the University of Zurich. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

KEY POINTS

QUESTION: What is the most suitable whole-body MRI sequence for PET/MRI in Hodgkin lymphoma patients?

PERTINENT FINDINGS: On the basis of our multicenter evaluation of pretreatment PET/MRI scans of 84 C2 study patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, T2w transverse sequences with fs are the most suitable for simultaneous whole-body PET/MRI. There was no evidence to recommend the use of contrast agents.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE: An optimized PET/MRI acquisition protocol would decrease anesthesia time in younger children and increase compliance in adolescents and adults.

REFERENCES

- 1. Verhagen MV, Menezes LJ, Neriman D, et al. 18F-FDG PET/MRI for staging and interim response assessment in pediatric and adolescent Hodgkin lymphoma: a prospective study with 18F-FDG PET/CT as the reference standard. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:1524–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Herrmann K, Queiroz M, Huellner MW, et al. Diagnostic performance of FDG-PET/MRI and WB-DW-MRI in the evaluation of lymphoma: a prospective comparison to standard FDG-PET/CT. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spick C, Herrmann K, Czernin J. 18F-FDG PET/CT and PET/MRI perform equally well in cancer: evidence from studies on more than 2,300 patients. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:420–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferdová E, Ferda J, Baxa J. 18F-FDG-PET/MRI in lymphoma patients. Eur J Radiol. 2017;94:A52–A63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang B, Law MW, Khong PL. Whole‐body PET/CT scanning: estimation of radiation dose and cancer risk. Radiology. 2009;251:166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shah DJ, Sachs RK, Wilson DJ. Radiation-induced cancer: a modern view. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e1166–e1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gatidis S, Gueckel B, La Fougère C, Schmitt J, Schaefer JF. Simultaneous whole-body PET-MRI in pediatric oncology: more than just reducing radiation? [in German]. Radiologe. 2016;56:622–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kirchner J, Deuschl C, Grueneisen J, et al. 18F-FDG PET/MRI in patients suffering from lymphoma: how much MRI information is really needed? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:1005–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kirchner J, Deuschl C, Schweiger B, et al. Imaging children suffering from lymphoma: an evaluation of different 18F-FDG PET/MRI protocols compared to whole-body DW-MRI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:1742–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Second international inter-group study for classical Hodgkin lymphoma in children and adolescents. U.S. National Library of Medicine website. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02684708. Published February 18, 2016. Updated May 13, 2021. Accessed October 31, 2022.

- 11. Kurch L, Mauz-Körholz C, Bertling S, et al. The EuroNet paediatric Hodgkin network: modern imaging data management for real time central review in multicentre trials. Klin Padiatr. 2013;225:357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mauz-Körholz C, Landman-Parker J, Balwierz W, et al. Response-adapted omission of radiotherapy and comparison of consolidation chemotherapy in children and adolescents with intermediate-stage and advanced-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma (EuroNet-PHL-C1): a titration study with an open-label, embedded, multinational, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:125–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Latifoltojar A, Humphries PD, Menezes LJ, et al. Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging in paediatric Hodgkin lymphoma: evaluation of quantitative magnetic resonance metrics for nodal staging. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49:1285–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barrington SF, Kluge R. FDG PET for therapy monitoring in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:97–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3059–3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schaefer JF, Berthold LD, Hahn G, et al. Whole-body MRI in children and adolescents: S1 guideline. Rofo. 2019;191:618–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hirsch FW, Sattler B, Sorge I, et al. PET/MR in children: initial clinical experience in paediatric oncology using an integrated PET/MR scanner. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43:860–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grueneisen J, Sawicki LM, Schaarschmidt BM, et al. Evaluation of a fast protocol for staging lymphoma patients with integrated PET/MRI. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Umutlu L, Beyer T, Grueneisen JS, et al. Whole-body [18F]-FDG-PET/MRI for oncology: a consensus recommendation. Nuklearmedizin. 2019;58:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hartung-Knemeyer V, Beiderwellen KJ, Buchbender C, et al. Optimizing positron emission tomography image acquisition protocols in integrated positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 2013;48:290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arendt CT, Beeres M, Leithner D, et al. Gadolinium-enhanced imaging of pediatric thoracic lymphoma: is intravenous contrast really necessary? Eur Radiol. 2019;29:2553–2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klenk C, Gawande R, Tran VT, et al. Progressing toward a cohesive pediatric 18F-FDG-PET/MR protocol: is administration of gadolinium chelates necessary? J Nucl Med. 2016;57:70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kanda T, Ishii K, Kawaguchi H, Kitajima K, Takenaka D. High signal intensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced T1-weighted MR images: relationship with increasing cumulative dose of a gadolinium-based contrast material. Radiology. 2014;270:834–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Radbruch A, Weberling LD, Kieslich PJ, et al. Gadolinium retention in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus is dependent on the class of contrast agent. Radiology. 2015;275:783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bezrukov I, Schmidt H, Gatidis S, et al. Quantitative evaluation of segmentation- and atlas-based attenuation correction for PET/MR on pediatric patients. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1067–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hofmann M, Bezrukov I, Mantlik F, et al. MR-based attenuation correction for whole-body PET/MR: quantitative evaluation of segmentation- and atlas-based methods. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1392–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kwee TC, Basu S, Torigian DA, Nievelstein RAJ, Alavi A. Evolving importance of diffusion‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging in lymphoma. PET Clin. 2012;7:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heacock L, Weissbrot J, Raad R, et al. PET/MRI for the evaluation of patients with lymphoma: initial observations. AJR. 2015;204:842–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Giraudo C, Karanikas G, Weber M, et al. Correlation between glycolytic activity on [18F]-FDG-PET and cell density on diffusion-weighted MRI in lymphoma at staging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;47:1217–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spijkers S, Littooij AS, Kwee TC, et al. Whole-body MRI versus an FDG-PET/CT-based reference standard for early response assessment and restaging of paediatric Hodgkin lymphoma: a prospective multicentre study. Eur Radiol. 2021;31:8925–8936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Littooij AS, Kwee TC, Barber I, et al. Accuracy of whole-body MRI in the assessment of splenic involvement in lymphoma. Acta Radiol. 2016;57:142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Punwani S, Cheung KK, Skipper N, et al. Dynamic contrast‐enhanced MRI improves accuracy for detecting focal splenic involvement in children and adolescents with Hodgkin disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43:941–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mayerhoefer ME, Karanikas G, Kletter K, et al. Evaluation of diffusion‐weighted MRI for pretherapeutic assessment and staging of lymphoma: results of a prospective study in 140 patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2984–2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Paes FM, Kalkanis DG, Sideras PA, Serafini AN. FDG PET/CT of extranodal involvement in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin disease. Radiographics. 2010;30:269–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. de Jong PA, Quarles van Ufford HM, Baarslag HJCT. 18F-FDG PET for noninvasive detection of splenic involvement in patients with malignant lymphoma. AJR. 2009;192:745–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Picardi M, Soricelli A, Pane F, et al. Contrast-enhanced harmonic compound US of the spleen to increase staging accuracy in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma: a prospective study. Radiology. 2009;251:574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Albano D, Patti C, Lagalla R, Midiri M, Galia M. Whole‐body MRI, FDG‐PET/CT, and bone marrow biopsy, for the assessment of bone marrow involvement in patients with newly diagnosed lymphoma. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;45:1082–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Krohmer S, Sorge I, Krausse A, et al. Whole-body MRI for primary evaluation of malignant disease in children. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74:256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schäfer JF, Gatidis S, Schmidt H, et al. Simultaneous whole-body PET/MR imaging in comparison to PET/CT in pediatric oncology: initial results. Radiology. 2014;273:220–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Albano D, La Grutta L, Grassedonio E, et al. Pitfalls in whole body MRI with diffusion weighted imaging performed on patients with lymphoma: what radiologists should know. Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;34:922–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Appenzeller P, Mader C, Huellner MW, et al. PET/CT versus body coil PET/MRI: how low can you go? Insights Imaging. 2013;4:481–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hirsch FW, Sorge I, Vogel-Claussen J, et al. The current status and further prospects for lung magnetic resonance imaging in pediatric radiology. Pediatr Radiol. 2020;50:734–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]