Abstract

Background

Investigating the association between infectious agents and non-communicable diseases is an interesting emerging field of research. Intestinal parasites (IPs) are one of the causes of gastrointestinal complications, malnutrition, growth retardation and disturbances in host metabolism, which can play a potential role in metabolic diseases such as diabetes. The aim of the present study was to investigate the prevalence of IPs in diabetic patients and the association between IPs and diabetes.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted from January 2000 to November 2022in published records by using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases as well as Google scholar search engine; Out of a total of 29 included studies, fourteen cross-sectional studies (2676 diabetic subjects) and 15 case-control studies (5478 diabetic/non-diabetic subjects) were reviewed. The pooled prevalence of IPs in diabetics and the Odds Ratio (OR) were evaluated by CMA V2.

Results

In the current systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of IPs in diabetic patients was 26.5% (95% CI: 21.8–31.7%) with heterogeneity of I2 = 93.24%; P < 0.001. The highest prevalence based on geographical area was in Region of the Americas (13.3% (95% CI: 9.6–18.0)).There was significant association between the prevalence of intestinal parasites in diabetic cases compared to controls (OR, 1.72; 95% CI: 1.06–2.78).

Conclusion

In line with the high prevalence of IPs in diabetic patients, significant association was found however, due to the limitations of the study, more studies should be conducted in developing countries and, the prevalence of IPs in diabetics should not be neglected.

Keywords: Intestinal parasites, Diabetes, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

DeclarationsList of abbreviations

- IPs

intestinal parasites

- OR

odd ratio

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- PRISMA

preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa scale

- NR

not reported

Authors' contributions

MZ and SB were responsible for designing the study.All studies were screened by SB and FF. Studies data were extracted by SB and KP and double-checked by MF, all data analyzed by HS. The MZ and SB resolved disputes or controversial obstacles.

1. Introduction

It is estimated that around 3.5 billion people worldwide suffer from intestinal parasites (IPs), especially in developing countries where have poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) [1,2]. These non-aggressive and widespread infections are a health problem that inflicts significant economic losses in addition to significant mortality; the high prevalence of these infections is due to transmission through contaminated water and food sources in areas with poor hygiene [3]. The most widespread infections have been reported with medically important protozoa such as cryptosporidium spp., Giardia sp. and Entamoeba histolytica, hence the most isolated helminth species are Strongyloides stercoralis, Trichuris trichiura, Ascaris lumbricoides, and hookworms eggs [4,5]. Parasitic infections are contagious, but evidence shows that they can contribute to asthma and allergies, autoimmune diseases, metabolic non-communicable disorders such as obesity, diabetes, and so on [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10]].

Diabetes is a major chronic non-communicable metabolic disorder in which the body is unable to produce or use insulin and thereby, hyperglycemia occurs; insufficient insulin production or defect in insulin acquisition are known as type 1 and type 2 diabetes, respectively [11]. According to the diabetes facts and figures, nearly 463 million people live with diabetes, which is assessed to reach 700 million in 2045 [12]. Clinical complications can manifest as severe thirst, frequent urination, weight loss, fatigue, and sensation loss [13]. Many of the factors associated with diabetes are mentioned, some of which have been proven and others of which are debatable [14]. In the past, genetics, nutrition, overweight, family history, and pregnancy (gestational diabetes) could be implicated, and in recent cases, urbanization and stress, as well as infectious agents, have been discussed [15]. Diabetes can be considered as an underlying disease that may make a person vulnerable and prone to infections or other diseases [16,17].

In recent decades, numerous studies have investigated the association between infectious agents and allergies, metabolic diseases, and autoimmune diseases and they have concluded that some infectious agents, such as Helicobacter pylori, Hepatitis C virus, and Toxoplasma gondii are associated with diabetes [[18], [19], [20]]. On the other hand, it has been proven that infectious agents such as parasites are able to alter certain enzymes and metabolic factors in the infected host [21]. In the present meta-analysis, the results of studies that investigated the prevalence of IPs in diabetics were used to assess the association between the prevalence of IPs and diabetes. Despite the limited number of included studies, our findings can be considered in health decisions and diabetes prevention programs in underdeveloped and developing areas.

The main question is whether there is a significant relationship between diabetes and the prevalence of intestinal parasites? In other words, does diabetes act as an underlying factor and predispose the host to parasitic infections? Finding the answer to this question is the main goal of this study.

2. Methods

2.1. Preliminary research/idea validation and eligibility criteria

A preliminary search was conducted to ensure the validity of the proposed idea (association of intestinal parasites and diabetes), and to avoid duplication of the proposed topic, as well as to ensure that a sufficient number of studies were available for analysis.

Eligible studies in terms of abstract and title were screened by two independent researchers. In the next step, to remove duplicate records, all studies were imported into the Endnotes X8 software. Overall included studies met all of the four criteria: 1) Original studies and brief reports, all in English text or abstract with no restrictions regarding the geographical area, patients gender, age, and race were published up to November 30, 2022, 2) Case-control, cross-sectional, and hospital based studies with diabetes and intestinal parasites, 3) The populations studied for diabetes or intestinal parasites were comparable, 4) All full-text and/or abstracts that have a data about the only intestinal parasites examination in diabetic patients.

Studies that did not meet any of these conditions were excluded, including in-vivo and in-vitro studies, letters to the editor, reviews, thesis/dissertations, case report studies, as well as reports with confusing and/or unclear data, disproportionate population surveys, and reports that biasedly examined non-intestinal parasites (blood, tissue, etc.) in diabetic patients.

2.2. Search strategy

In this study, a systematic search was conducted for the association of diabetes and intestinal parasites in English published records in the Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science databases as well as Google scholar search engine between Jan 01, 2000, and Nov 30, 2022, following PRISMA ’preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses’ guidelines which developed by Moher et al. [22,23]. The following terms were used alone or in combination to search the databases: “Intestinal parasites' OR ‘Parasitic infections’ OR ‘Parasite”, AND “Prevalence’ OR ‘Epidemiology’” AND “Diabetes' OR ‘Diabetes mellitus’ OR ‘Diabetic patients’ ”. In addition, references of all eligible articles were manually searched to find related studies that may have been missed during search process.

2.3. Study selection and data extraction

All studies entered with the mentioned eligibility criteria were screened by SB and FF. After the initial evaluation and ensuring the existence of extractable data, data were extracted by SB and double-checked and analyzed by HS. The MZ and FF resolved disputes or controversial obstacles. The extracted data included the authors, geographical area (including country and city), sample population, sample type, type of diagnostic method used for parasite detection, and positive cases of intestinal parasites in diabetic patients. In cross-sectional studies, the total sample was considered the general population, and in case-control studies, patients with diabetes were considered as the study population.

2.4. Quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist were used to assess the quality of the potential case-control and cross-sectional studies. NOS contains ten questions with four answering options include, yes, no, unknown, and not available. The maximum score a study can obtain is ten (one star for each item) [24]. Studies with a total score of 6 ≤ were acceptable and included our study. According to the JBI ten-question scale, each study can achieve a maximum of ten points (one point for each question) [25], in this study, any study whose total score is ≤ 3 is considered as a low-quality study and not included in the analysis.

2.5. Data synthesis and statistical analysis

We pooled the intestinal parasitic infections (IPIs) prevalence in diabetic patients using the random-effect model intended to perform the meta-analysis in comprehensive meta-analysis software (CMA V2.2, Bio stat). As well, we applied the random-effects meta-analysis framework as we expected variability in the prevalence estimates from different studies. Subgroup analysis was conducted based on study type, studies geographical area (WHO categorized regions and countries), and diagnostic methods. The heterogeneity of results between studies was checked using Cochran's Q statistic (P < 0.10) and was quantified using the I2 and t2 statistic. A combination of the visual inspection of funnel plots, and Egger's test [26] were performed to investigate the presence and the effect of publication bias. Two-tailed statistics and the significance level of less than 0.05 were considered for all analyses, except the heterogeneity test with a significance level of less than 0.1.

3. Results

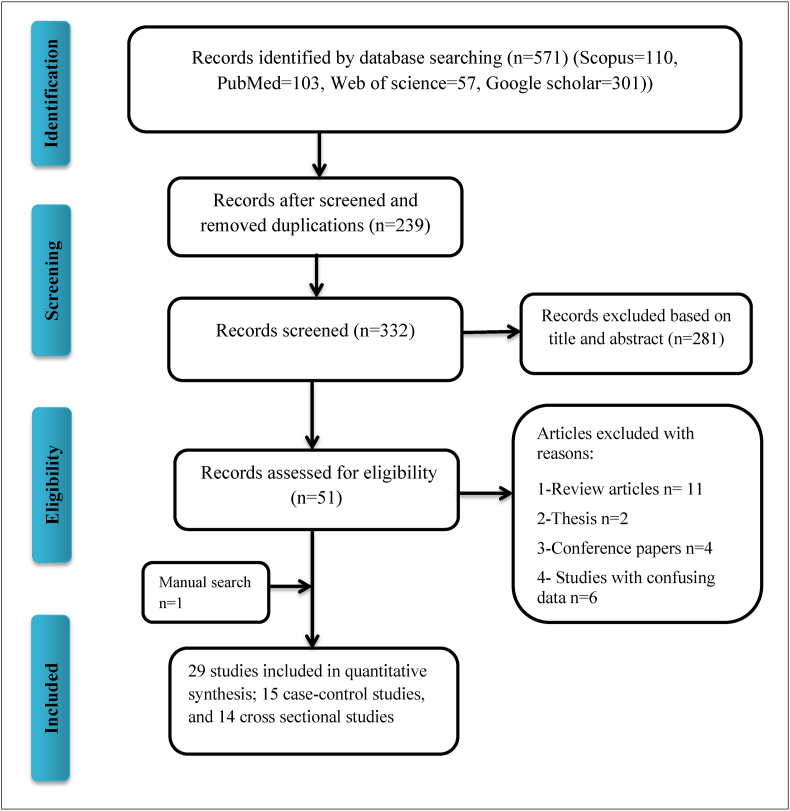

The process of literature search and study selection based on the PRISMA flow chart is shown in Fig. 1. Overall, 571 potentially relevant articles were recognized from the initial search. Of these, 520 articles were excluded after removing duplicates, screening the titles and abstracts, and the full text of the remaining 51 articles was achieved from different sources. Lastly, 29 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search for studies included in the meta-analysis.

Cross sectional and case-control studies investigating the prevalence of IPs in diabetics as well as controls that were published between Jan 1, 2000, and Nov 30, 2022 included 29 records conducted in 4 different geographical areas; among them, seven studies were from African region, twelve reports from Eastern Mediterranean region, three studies were from Region of the Americas, similarly three papers related to the South-east Asia region and one study from European and Western pacific regions (Table 1, Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of studies characteristics with IPs prevalence in diabetic patients based on cross-sectional studies.

| Author name | Pub year | Research period | WHO regions | Country | City/State | sample type | Method | Total sample | Pos sample | Parasite type (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alemu et al. [27] | 2018 | 2017–2017 | African region | Ethiopia | Arba Minch | Stool | direct wet mount | 215 | 42 | Cryptosporidium spp. (18), Ascaris lumbricoides (8), Hookworms(4),Trichuris trichuria(4),Giardia lamblia(6), Teania spp(2) |

| Ambachew et al. [28] | 2020 | 2018–2018 | African region | Ethiopia | Amhara | Stool | Formal-ether, microscopic | 234 | 45 | Ascaris lumbricoides (15), Entamoeba histolytica/dispar (9), Hookworms (9) |

| Engidaw and Feysa [29] | 2020 | 2019–2019 | African region | Ethiopia | Debre Tabo | NR | NR | 265 | 69 | IPs |

| Sisu et al. [30] | 2021 | 2021–2021 | African region | Ghana | Bolgatanga | Stool | Formal-ether, microscopic | 152 | 19 | Giardia lamblia (9), E. histolytica (4), C. parvum (3), Entamoeba. coli (3), A. lumbricoides (1) and hookworm (1) |

| Baqai et al. [31] | 2005 | 2003–2003 | Eastern Mediterranean | Pakistan | Karachi | Stool | Kinyoun method | 20 | 5 | Cryptosporidium spp. |

| Ali et al. [32] | 2018 | 2017–2018 | Eastern Mediterranean | Iraq | Kirkuk | Stool | Microscopic examination | 419 | 62 | Blastocystis hominis(22),C. parvum(8), E. histolytica/dispar(11),G. lamblia(16),Iodamoeba butschlii(1), Strongyloides stercoralis(1),Hymenolepis nana(3) |

| AL-Mousawi and Neamah [33] | 2021 | 2020–2021 | Eastern Mediterranean | Iraq | Najaf | Stool | sedimentation, modified Ziehl Neelsen stain | 372 | 137 | E. histolytica (47), G. lamblia (39), A. lumbricoides (19), T.vaginalis (12), T.gondii (11), C.parvum (9) |

| Nami et al. [34] | 2022 | 2015–2019 | Eastern Mediterranean | Libya | Benghazi | Stool | direct wet mount, Ziehl-Neelsen staining | 200 | 80 | Blastocystis hominis(1), E.histolytica/dispar (10), G.lamblia (10), E.coli (21), C.parvum (17), E.hartmani (9), Isospora.belli (5), D.fragilis (3), A.lumbricoides (0), Enterobius.vermicularis (1) |

| Machado et al. [4] | 2018 | 2011–2012 | Region of the Americas | Brazil | Taguatinga | Stool | Formal-ether, microscopic | 156 | 102 | E. coli(43), Endolimax nana(23), Giardia lamblia(16), E. hartmanni(10), A. lumbricoides(12), Teania spp.(3), Hookworms(2), H. nana(1), S. stercoralis(1), E. vermicularis(1), Schistosoma mansoni(1). |

| Calderon de la Barca et al. [35] | 2020 | 2016–2018 | Region of the Americas | Mexico | Sonora | Stool | PCR | 37 | 28 | Cryptosporidium spp., Cyclospora spp., Blastocystis spp. |

| Bora et al. [36] | 2016 | 2015–2016 | South-east Asia | India | India | Stool | Microscopic examination | 17 | 3 | E. histolytica/E. dispar, Hookworms, S. stercoralis, Teania spp., G. lamblia, T. trichiura |

| Chandi et al. [37] | 2020 | 2019–2019 | South-east Asia | India | Bhilai | Stool | Microscopic examination | 110 | 15 | E. histolytica/dispar(8),C. parvum(5), A. lumbricoides(2)G. lamblia(1)a |

| Popruk et al. [38] | 2020 | 2019–2020 | South-east Asia | Thailand | Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya | Stool | Nested-PCR | 130 | 16 | Blastocystis spp. |

| Htun et al. [39] | 2018 | 2016–2016 | Western pacific region | Laos | Four areas | Stool | Formal-ether, microscopic | 349 | 100 | Opishorchis viverrini (90), Minute intestinal flukes (18), Paragonimus spp. (1), Hookworms (14), S. stercoralis (6), Teania spp. (13)a |

In these studies, more than one parasite was detected in some participants, NR: Not Reported, DM: Diabetes Mellitus, T1, 2D; Type 1, 2 Diabete.

Table 2.

Summary of studies characteristics with IPs prevalence in diabetic patients based on case-control studies.

| First author | Pub year | WHO regions | Country | Parasites detection method(s) | Total diabetic cases | IPs positive No | Total control | IPs positive No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akhlaghi et al. [40] | 2005 | Eastern Mediterranean | Iran | Formalin-ether/acid-fast staining | 250 | 39 | 250 | 25 |

| Akinbo et al. [41] | 2013 | African region | Nigeria | Formalin-ether | 150 | 28 | 30 | 0 |

| Bafghi et al. [42] | 2015 | Eastern Mediterranean | Iran | Formalin-ether | 250 | 61 | 250 | 58 |

| Elnadi et al. [43] | 2015 | Eastern Mediterranean | Egypt | Modified Ziehl-Neelsen Acid | 100 | 25 | 100 | 7 |

| Mohtashamipour et al. [44] | 2015 | Eastern Mediterranean | Iran | Formalin-ether/acid-fast and trichrome staining | 118 | 31 | 118 | 8 |

| Poorkhosravani et al. [45] | 2019 | Eastern Mediterranean | Iran | Baermann and trichrome staining | 254 | 32 | 247 | 46 |

| Tangi et al. [46] | 2016 | African region | Cameroon | Formalin-ether/acid-fast staining | 150 | 15 | 85 | 20 |

| Nazligul et al. [47] | 2001 | European region | Turkey | Parasitology method | 200 | 94 | 1024 | 724 |

| Rady et al. [48] | 2019 | Eastern Mediterranean | Egypt | Parasitology method | 413 | 86 | 260 | 52 |

| Al-heety et al. [49] | 2020 | Eastern Mediterranean | Iraq | PCR | 40 | 17 | 30 | 1 |

| Waly et al. [50] | 2021 | Eastern Mediterranean | Egypt | Parasitology method | 100 | 44 | 100 | 32 |

| Almugadam et al. [51] | 2021 | Eastern Mediterranean | Sudan | Parasitology method | 150 | 31 | 150 | 16 |

| Maori et al. [52] | 2021 | African region | Nigeria | Parasitology method | 138 | 70 | 46 | 4 |

| de Melo et al. [53] | 2021 | Region of the Americas | Brazil | PCR | 99 | 34 | 76 | 23 |

| Bebia et al. [54] | 2022 | African region | Nigeria | Parasitology method | 190 | 48 | 110 | 12 |

3.1. The pooled prevalence of IPs in diabetic patients

Based on the random-effects model, the pooled prevalence of IPs in diabetic patients was estimated to be 26.5% (95% CI: 21.8–31.7%). The sub-total prevalence of IPs in diabetic patients showed that based on studies WHO categorized regions, the highest and lowest prevalence were in Region of the Americas and South-east Asia region, respectively (13.3% (95% CI: 9.6–18.0) vs. 58.6 (95% CI: 34.0–79.5)). In the present study, 5278 subjects (2676 in cross-sectional and 5478 in case-control studies) were studied. (Summarized in Table 3).

Table 3.

Pooled and subgroup prevalence results of IPs in diabetic patients based on geographic region and diagnostic method.

| Variables | Studies NO | Samples NO | Pooled prevalence (95% CI) | Heterogeneity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | t2 | ||||

| WHO Regions | |||||

| African region | 9 | 1644 | 21.4 (15–29.6) | 91.42 | 036 |

| Ethiopia | 3 | 714 | 21.7 (17.5–26.5) | 53.60 | 0.03 |

| Ghana | 1 | 152 | 12.5 (8.1–18.8) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Cameroon | 1 | 150 | 10.0 (6.1–15.9) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Nigeria | 3 | 478 | 30.2 (15.2–51.0) | 94.56 | 0.57 |

| Sudan | 1 | 150 | 20.7 (14.9–27.9) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Eastern Mediterranean region | 12 | 2536 | 25.4 (19.9–31.8) | 90.99 | 0.29 |

| Iran | 4 | 872 | 19.1 (13.4–26.3) | 82.49 | 0.15 |

| Iraq | 3 | 831 | 29.2 (14.0–51.2) | 96.19 | 0.63 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 20 | 25.0 (10.8–47.8) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Libya | 1 | 200 | 40.0 (33.4–46.9) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Egypt | 3 | 613 | 28.9 (17.1–44.4) | 90.79 | 0.32 |

| European region | 1 | 200 | 47.0 (40.2–53.9) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Turkey | 1 | 200 | 47.0 (40.2–53.9) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Region of the Americas | 3 | 292 | 58.6 (34.0–79.5) | 93.01 | 0.73 |

| Mexico | 1 | 37 | 75.7 (59.5–86.8) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Brazil | 2 | 255 | 50.0 (22.1–77.9) | 95.56 | 0.78 |

| South-east Asia | 3 | 257 | 13.3 (9.6–18.0) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| India | 2 | 127 | 14.2 (9.1–21.5) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Thailand | 1 | 130 | 12.3 (7.7–19.1) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Western pacific region | 1 | 349 | 28.7 (24.2–33.6) | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Laos | 1 | 349 | 28.7 (24.2–33.6) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Diagnostic methoda | |||||

| Microscopic | 24 | 2411 | 24.9 (20.1–30.5) | 93.67 | 0.44 |

| Molecular | 4 | 306 | 38.5 (17.1–65.4) | 93.61 | 1.18 |

| Pooled prevalence | 29 | 5278 | 26.5% (95% CI: 21.8–31.7%) | 93.24 | 0.44 |

In one report, the diagnosis method was not reported.

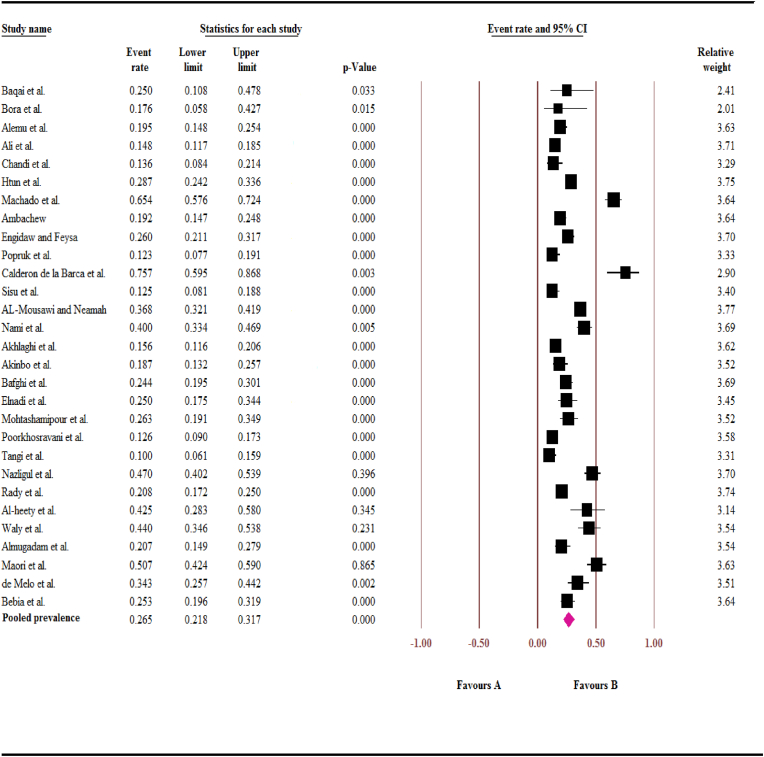

Substantially high heterogeneity was observed between different studies (I2 = 93.24%; t2 = 0.44, P < 0.001). Fig. 2 depicts the results in forest plot format.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of intestinal parasites pooled prevalence in diabetic patients.

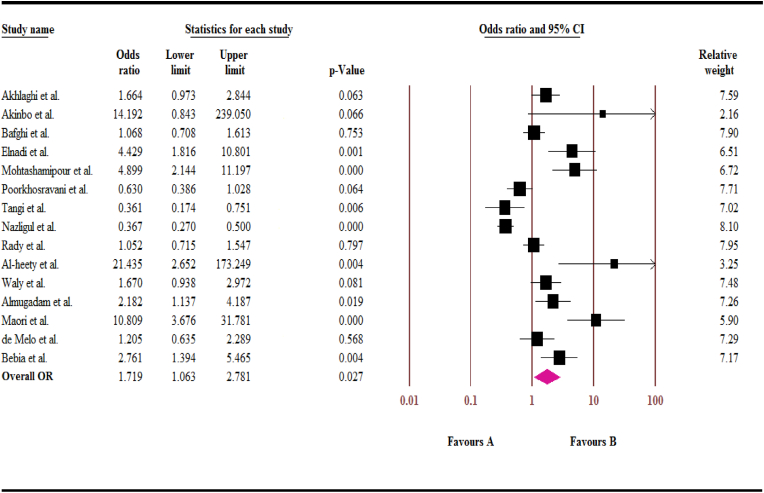

3.2. The overall odd ratio of IPs in diabetic patients based on case-control studies

As shown in Fig. 3, we found that despite the high prevalence of IPs in diabetic patients, according to case-control studies, there was statistically significant association between the case and control groups (OR, 1.72; 95% CI: 1.06–2.78) (I2 = 89.01%; t2 = 0.72).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of odds ratios for the intestinal parasites in diabetic patients, based on case-control studies.

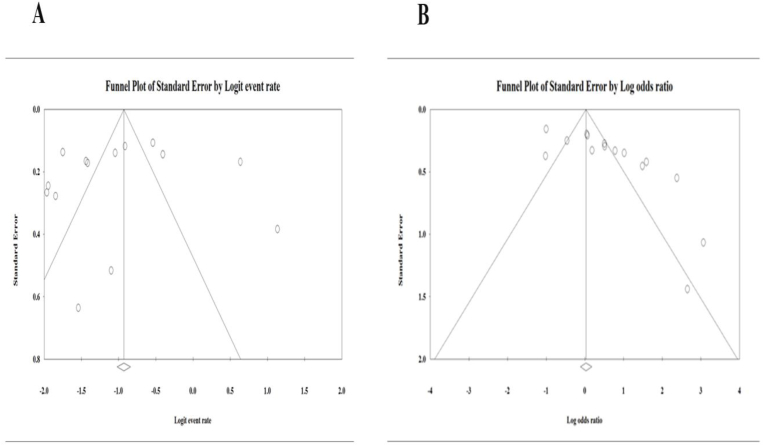

3.2.1. Publication bias

A funnel plot was used to identify the potential publication bias. In present study, studies with cross-sectional (Fig. 4 A) and case-control (Fig. 4 B) design respectively. Also, according to Egger's regression test, significant and no significant publication bias was found in studies presenting results for case-control (P = 0.00) and cross-sectional (P = 0.50) design respectively.

Fig. 4.

Publication bias using funnel plots. (A) Publication bias in studies with cross-sectional design (B) Publication bias in studies with a case-control design.

4. Discussion

In the last two decades, extensive studies have been conducted on the associations of infectious agents and diabetes. These studies were two-dimensional; some of them have evaluated the prevalence of infectious agents in diabetics while the rest of them have investigated the frequency of diabetes in people with infections. Toxoplasma gondii and Strongyloides stercoralis infections were among the parasitic diseases that have been studied in diabetics but none of the studies have provided a comprehensive summary of intestinal parasites in diabetic people. The present study is the first report in this field. According to our results, the overall pooled odds ratio of IPs was significant in diabetic patients compared to non-diabetic controls (OR, 1.72; 95% CI: 1.06–2.78).

IPs infections generally occur in poor hygiene and contamination of the water and food sources, which we see in underdeveloped and developing countries [55]. The included studies were also conducted in such areas that had a moderate to low human development index. It seems that the spread and transmission of many IPs infections have been controlled by improving the environment, sanitary disposal of human waste, mass treatment and providing safe drinking water in most of the developed regions of the world. Most of the included reports were from areas with lower sanitation and underdeveloped countries. In this regard, the highest prevalence was related to the Region of the Americas and the Mexico country which is very remarkable. It is noteworthy that approximately 80% of people with diabetes living in low- and middle-income countries. Therefore, it is interesting to investigate the association of these two health problems in the mentioned area [56]. As we know, diabetes is classified into two main types. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune response in which the immune system attacks the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas; this type is also known as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. In type 2 diabetes, the body is unable to use the insulin produced and is not able to control blood sugar at normal levels. The incidence of type 1 and 2 diabetes rates are 5%–10% and 90%–95%, respectively [57]. Diabetes is thought to be a long-lasting, chronic complication that gradually causes dysfunction and malfunctions in the various organs as well as blood pressure; therefore, it makes a person susceptible to a wide range of diseases, especially infectious diseases [58].

IPs are responsible for disorders extending from self-limiting discomforts to serious danger condition like malnutrition, growth retardation, and anemia. As well, nearly 40 million worldwide disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) disabilities have been associated with diseases caused by IPs [51]. According to our search finding, the most isolated parasites were Ascaris lumbercoides, Entamoeba species, Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia lamblia and Strongyloides stercoralis in cross-sectional studies. The technique used to isolate parasites in most studies, was parasitological methods such as Formal-Ether sedimentation and staining methods. It should be noted that the sensitivity of microscopic detection is low and there is a possibility of missing parasites. Hence, the estimated prevalence represents the tip of the iceberg and the true prevalence may be much higher. In contrast to molecular methods, they have high sensitivity and specificity, in the four included studies, the prevalence was higher than the microscopic method (38.5% (95% CI: 17.1–65.4) vs. 24.9% (95% CI: 20.1–30.5). Several studies have examined a particular special parasite in diabetics. Majidiani et al. did not observe the significant association between Toxoplasma gondii and type 1 diabetes, but ex vivo studies are controversial [7]. However, the number of studies conducted on people with type 1 diabetes has been limited due to its nature and low prevalence. Nosaka et al. found a significant association between Toxoplasma gondii and type 2 diabetes (OR, 2.32; 95% CI 1.66–3.24, P < 0.001) they concluded that if Toxoplasma gondii was shown to be involved in chronic inflammation leading to diabetes, it should be considered as a factor in the early prognosis of diabetes [59] which was in line with the results of the present study. In accordance with the findings of the present study, this hypothesis can also be generalized to IPs; this means that IPs due to their high prevalence in diabetics can play a risk factor for diabetes. Significant heterogeneity can be due to differences in operators, the small number of studies, geographical areas as well as differences in applied methods sensitivity/specificity.

The limitations that this meta-analysis study has faced include 1) the small number of studies in this field, especially on a limited geographical scale, 2) Existence of different techniques for detecting parasites in diabetics who were not homogeneous in terms of sensitivity and specificity, 3) The orientation of some studies in the diagnosis of only one parasite and ignoring other parasitic organisms that were easily detectable, 4) The included studies had insignificant details of the demographic characteristics of the participants such as age, sex, type of diabetes status, etc.

Conclusion: The present meta-analysis study indicates a remarkable prevalence of IPs in diabetic individuals; the association between IPs and diabetes was found to be significant, therefore, the prevalence of IPs in diabetics should not be neglected. It is suggested that future studies with larger sample sizes and more details and Homogeneity of case and control group be designed.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study design including its ethical aspects was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences (IR.ABZUMS.REC.1399.230).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

All authors of this manuscript declare that we have seen and approved the submitted version of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data associated with this manuscript are included in the article.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgments

None.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Zibaei, Email: Zibaeim@sums.ac.ir.

Saeed Bahadory, Email: Saeed.Bahadory@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Gizaw Z., et al. Childhood intestinal parasitic infection and sanitation predictors in rural Dembiya, northwest Ethiopia. Environ Health Prev Med. 2018;23(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s12199-018-0714-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yemata G., et al. 2020. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated factors among diarrheal outpatients in South gondar zone, Northwest, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramana K. Intestinal parasitic infections: an overview. Ann Trop Med Publ Health. 2012;5(4):279. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado E.R., et al. Host-parasite interactions in individuals with type 1 and 2 diabetes result in higher frequency of Ascaris lumbricoides and Giardia lamblia in type 2 diabetic individuals. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/4238435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Ruiter K., et al. Helminths, hygiene hypothesis and type 2 diabetes. Parasite Immunol. 2017;39(5) doi: 10.1111/pim.12404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zibaei M., et al. Human Toxocara infection: allergy and immune responses. Anti-Inflammatory Anti-Allergy Agents Med Chem. 2019;18(2):82–90. doi: 10.2174/1871523018666181210115840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majidiani H., et al. Is chronic toxoplasmosis a risk factor for diabetes mellitus? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Braz J Infect Dis. 2016;20(6):605–609. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zavala G., et al. Intestinal parasites: associations with intestinal and systemic inflammation. Parasite Immunol. 2018;40(4) doi: 10.1111/pim.12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hays R., et al. Does Strongyloides stercoralis infection protect against type 2 diabetes in humans? Evidence from Australian Aboriginal adults. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;107(3):355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khatami A., et al. Two rivals or colleagues in the liver? Hepatit B virus and Schistosoma mansoni co-infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb Pathog. 2021;154 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.104828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musselman D.L., et al. Relationship of depression to diabetes types 1 and 2: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Biol Psychiatr. 2003;54(3):317–329. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Federation I. eighth ed. 2017. IDF diabetes Atlas. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yagihashi S., Yamagishi S.-I., Wada R. Pathology and pathogenetic mechanisms of diabetic neuropathy: correlation with clinical signs and symptoms. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77(3):S184–S189. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petry C.J. Gestational diabetes: risk factors and recent advances in its genetics and treatment. Br J Nutr. 2010;104(6):775–787. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510001741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Group S.-T.D.P.S. Presence of diabetes risk factors in a large US eighth-grade cohort. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(2):212–217. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vieira M.N., Lima-Filho R.A., De Felice F.G. Connecting Alzheimer's disease to diabetes: underlying mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Neuropharmacology. 2018;136:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casqueiro J., Casqueiro J., Alves C. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus: a review of pathogenesis. Indian J Endocrinol Metabol. 2012;16(Suppl1):S27. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.94253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeon C.Y., et al. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with an increased rate of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):520–525. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Negro F., Alaei M. Hepatitis C virus and type 2 diabetes. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2009;15(13):1537. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y.-X., et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection in diabetes mellitus patients in China: seroprevalence, risk factors, and case-control studies. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/4723739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth E.J., et al. 1988. The enzymes of the glycolytic pathway in erythrocytes infected with Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tawfik G.M., et al. A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Trop Med Health. 2019;47(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s41182-019-0165-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munn Z., et al. The development of software to support multiple systematic review types: the Joanna Briggs Institute system for the unified management, assessment and review of information (JBI SUMARI) JBI Evid Implement. 2019;17(1):36–43. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egger M., Davey-Smith G., Altman D. John Wiley & Sons; 2008. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alemu G., Jemal A., Zerdo Z. Intestinal parasitosis and associated factors among diabetic patients attending Arba Minch Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3791-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ambachew S., et al. The prevalence of intestinal parasites and their associated factors among diabetes mellitus patients at the University of Gondar Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. J Parasitol Res. 2020:2020. doi: 10.1155/2020/8855965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engidaw M.T., Feyisa M.S. Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among adult diabetes mellitus patients at Debre Tabor General Hospital, Northcentral Ethiopia. Diabetes, Metab Syndrome Obes Targets Ther. 2020;13:5017. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S286365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sisu A., et al. Intestinal parasite infections in diabetes mellitus patients; A cross-sectional study of the Bolgatanga municipality, Ghana. Scientific African. 2021;11 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baqai R., Anwar S., Kazmi S. Detection of Cryptosporidium in immunosuppressed patients. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2005;17(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ali O.S., Mohammad S.A., Salman Y.J. Incidence of some intestinal parasites among diabetic patients suffering from gastroenteritis. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2018;7(8):3695–3708. [Google Scholar]

- 33.hussein Al-Mousawi A., Neamah B.A.H. A study on intestinal parasites among diabetic patients in Najaf governorate of Iraq and its effect on some blood parameters. Iranian Journal of Ichthyology. 2021;8:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Younis E. Helicobacter pylori infections among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Benghazi, Libya. J Gstro Hepato. 2022;8:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calderón de la Barca A.M., et al. Enteric parasitic infection disturbs bacterial structure in Mexican children with autoantibodies for type 1 diabetes and/or celiac disease. Gut Pathog. 2020;12(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13099-020-00376-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bora I., et al. Study of intestinal parasites among the immunosuppressed patients attending a tertiary-care center in Northeast India. Int J Med Sci Publ Health. 2016;5(5):924–929. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chandi D.H., Lakhani S.J. Prevalence of parasitic infestation in diabetic patients in tertiary care hospital. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2020;9(2):1434–1441. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Popruk N., et al. Prevalence and subtype distribution of Blastocystis infection in patients with diabetes mellitus in Thailand. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17(23):8877. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17238877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Htun N.S.N., et al. Association between helminth infections and diabetes mellitus in adults from the Lao People's Democratic Republic: a cross-sectional study. Infectious Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40249-018-0488-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akhlaghi L., et al. Survey on the prevalence rates of intestinal parasites in diabetic patients in Karaj and Savodjbolagh cities. Razi J Med Sci. 2005;12(45):23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akinbo F.O., et al. Intestinal parasitic infections among diabetes mellitus patients. Biomarkers Genom Med. 2013;5(1–2):44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fattahi Bafghi A., Afkhami-Ardekani M., Dehghani Tafti A. Frequency distribution of intestinal parasitic infections in diabetic patients–Yazd 2013. Iran J Diabetes Obes. 2015;7(1):33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elnadi N.A., et al. Intestinal parasites in diabetic patients in Sohag University hospitals, Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2015;45(2):443–449. doi: 10.12816/0017597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mohtashamipour M., et al. Intestinal parasitic infections in patients with diabetes mellitus: a case-control study. J Res Clin Med. 2015;3(3):157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poorkhosravani Z., et al. Frequency of intestinal parasites in patients with diabetes mellitus compared with healthy controls in Fasa, Fars Province, Iran. Hormozgan Med J. 2019;23(2) 2018. e91284-e91284. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tangi F.B., et al. Intestinal parasites in diabetes mellitus patients in the Limbe and Buea municipalities, Cameroon. Diabetes Res Open J. 2016;2(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nazligul Y., Sabuncu T., Ozbilge H. Is there a predisposition to intestinal parasitosis in diabetic patients? Diabetes Care. 2001;24(8):1503–1504. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1503-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rady H.I., et al. Parasites and Helicobacter pylori in Egyptian children with or without diabetes with gastrointestinal manifestations and high calprotectin level. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2019;49(1):243–248. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-heety M.S., Al-Ani S.F., Jasem M.A. Molecular and parasitological study on selected opportunistic intestinal parasites in immunocompromised patients. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2020;14(4) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waly W.R., et al. Intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors in diabetic patients: a case-control study. J Parasit Dis. 2021;45(4):1106–1113. doi: 10.1007/s12639-021-01402-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Almugadam B.S., et al. Association of urogenital and intestinal parasitic infections with type 2 diabetes individuals: a comparative study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05629-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maori L., et al. Intestinal parasitic infections among diabetes mellitus patients attending murtala Muhammad specialist hospital (Mmsh), Kano, Kano state. South Asian J Parasitol. 2021:6–14. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melo G.B.d., et al. Vol. 63. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo; 2021. (Blastocystis subtypes in patients with diabetes mellitus from the Midwest region of Brazil). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bebia G.P., et al. Prevalence of malaria and intestinal parasitic Co-infection among diabetic patients in Calabar. Global J Pure Appl Sci. 2022;28(2):193–200. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alum A., Rubino J.R., Ijaz M.K. The global war against intestinal parasites—should we use a holistic approach? Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(9):e732–e738. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Forouhi N.G., Wareham N.J. Epidemiology of diabetes. Medicine. 2010;38(11):602–606. [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Ornelas Maia A.C.C., et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with diabetes types 1 and 2. Compr Psychiatr. 2012;53(8):1169–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lilliu M.A., et al. Diabetes causes morphological changes in human submandibular gland: a morphometric study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2015;44(4):291–295. doi: 10.1111/jop.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nosaka K., Hunter M., Wang W. The association between Toxoplasma gondii and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of human case-control studies. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2020;44(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data associated with this manuscript are included in the article.