Abstract

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) has proven to be easier to implement than PCR for point-of-care diagnostic tests. However, the underlying mechanism of LAMP is complicated and the kinetics of the major steps in LAMP have not been fully elucidated, which prevents rational improvements in assay development. Here we present our work to characterize the kinetics of the elementary steps in LAMP and show that: (i) strand invasion / initiation is the rate-limiting step in the LAMP reaction; (ii) the loop primer plays an important role in accelerating the rate of initiation and does not function solely during the exponential amplification phase and (iii) strand displacement synthesis by Bst-LF polymerase is relatively fast (125 nt/s) and processive on both linear and hairpin templates, although with some interruptions on high GC content templates. Building on these data, we were able to develop a kinetic model that relates the individual kinetic experiments to the bulk LAMP reaction. The assays developed here provide important insights into the mechanism of LAMP, and the overall model should be crucial in engineering more sensitive and faster LAMP reactions. The kinetic methods we employ should likely prove useful with other isothermal DNA amplification methods.

INTRODUCTION

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) is a powerful nucleic acid amplification method that uses 4–6 primers with a strand-displacing DNA polymerase to generate concatemeric amplicons from DNA or RNA targets (1). Similar to PCR, LAMP performs exponential amplification of nucleic acid targets, but in contrast to PCR both primer invasion and amplification occur at a single temperature. LAMP has proven especially important in healthcare and food industries, where rapid point-of-care nucleic acid detection is necessary but complex, specialized lab equipment such as PCR machines are not readily accessible (2–4).

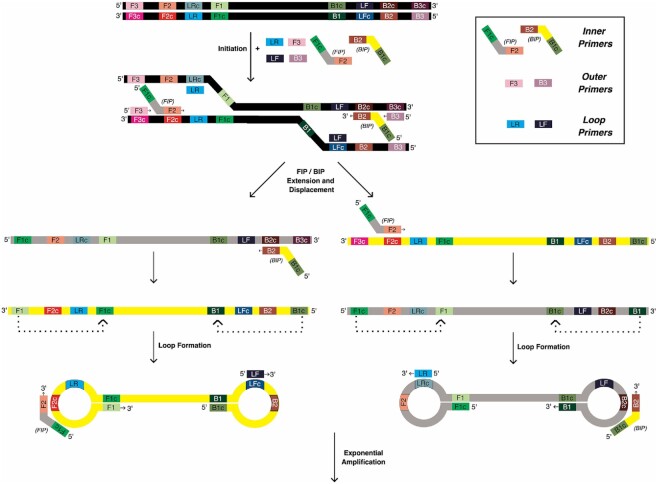

Exponential isothermal amplification in LAMP is made possible by the ability of the uniquely designed forward and backward inner LAMP primers, FIP and BIP, to promote formation of foldback stem–loop structures in the LAMP amplicons (1), as illustrated in Figure 1. Each inner primer is designed by juxtaposing two distinct regions of the target sequence: the 3′-end region primes the first stage of amplification and is also responsible for binding new amplicons during the exponential phase. Meanwhile, the 5′-end fragment promotes formation of the foldback structures that facilitate self-priming and further binding of new primers. Amplification is aided by two outer primers, F3 and B3, that are thought to initiate the exponential phase of amplification by binding upstream of the inner primers to support strand displacement DNA synthesis so that the displaced strand can fold into the characteristic double stem–loop dumbbell-like structure that includes a self-priming 3′-end and single-stranded loops. The loops in turn can bind new inner primers that initiate further strand displacement DNA synthesis, ultimately leading to formation of large concatemeric amplicons.

Figure 1.

LAMP Overview. Three primers (shown as small colored boxes) for each side of the target DNA to be amplified (black) are added with Bst polymerase and incubated at 65°C to start the reaction. During initiation, the primers anneal to their respective complementary regions in the target DNA, leading to extension of the forward and backward internal primers (FIP and BIP, shown with grey and yellow middle regions, respectively), which are then displaced by outer primers F3 and B3. Amplification of the displaced products in the opposite direction by the other internal primer results in structures that fold back to form loops, providing multiple opportunities for extension, ultimately leading to large concatemer formation and exponential amplification of the starting DNA.

Due to the isothermal and continuous nature of amplification, LAMP is typically faster than PCR and yields 109 to 1010 copies within an hour. This process can be accelerated by adding additional loop binding primers (LP), stem primers, or swarm primers (5), with some LAMP assays being completed within 10 min. With the ability to detect single digit template copies, LAMP is also considered one of the most sensitive nucleic acid amplification methods rivaling PCR. Furthermore, since LAMP uses 4–6 primers complementary to 6–8 regions on target nucleic acids, it shows high target specificity, although spurious amplicons resulting from unintended primer interactions can also arise. To overcome the possibility of non-specific amplification, we have previously engineered hemiduplex, oligonucleotide strand displacement (OSD) probes that ‘light up’ upon the initiation of strand displacement by single-stranded loops in LAMP amplicons (6).

A better understanding of the underlying kinetics of LAMP amplification would greatly assist with the design of assays, which currently are optimized primarily through trial-and-error. Numerous PCR kinetic models that have provided better insight into its amplification mechanisms and parameters which have facilitated device engineering and process improvement (7–9). In contrast, kinetic analysis of the multistep LAMP process has only begun to be investigated (10,11). It is generally believed that LAMP amplification is initiated when sporadic breathing of double-stranded templates (at an amplification temperature of ca. 63–65°C) allows strand invasion by LAMP primers; however, to date there have been no kinetic studies to quantify the rates of primer invasion or strand displacement synthesis in the LAMP reaction. Herein we present our work to characterize the elementary steps of the LAMP reaction through pre-steady-state kinetic analysis. We have broken the reaction down into a series of experiments that mimic fundamental steps in the amplification reaction in order to collectively describe the overall process. We propose a kinetic model that is consistent with both our kinetic data and bulk LAMP progress curves.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and reagents

All chemicals used in this study were of at least 99% purity and were purchased from either Sigma Aldrich or ThermoFisher Scientific.

Enzymes

Bst-LF was prepared as previously described (12). Briefly, N-terminal 6x His tagged full-length sequence of the Bst-LF (PDB ID:3TAN) was expressed using the plasmid pAtetO-Bst-LF (Addgene ID: 145799). The plasmid was transformed into BL21(DE3) E. coli and a single colony was picked and grown in Superior Broth™ (Athena Enzyme Systems: 0105) at 37°C overnight. The next day 5 ml of the overnight culture was inoculated into 500 ml of Superior Broth™ and grown at 37°C with shaking at 230 RPM until the OD600 reached 1.0. Protein expression was induced by adding aTc (Anhydrous Tetracycline) to 100 ng/ml and protein was expressed at 18°C overnight with shaking at 230 RPM. The induced cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 4000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in Resuspension Buffer (50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 1× protease inhibitor tablet; Thermo Scientific; A32965) at 10 ml buffer per gram of Escherichia coli, and sonicated for a total of 4 min with a Branson 450 Digital Sonifier at 40% strength, 1 s on/4 s off cycle. The lysate was then clarified by centrifugation at 35 000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was then poured onto a gravity flow Ni-NTA column (Immobilized metal affinity column, Ni-NTA Sepharose; HisPur™ Ni-NTA Resin, Thermo Fisher, Cat:88222, added 2 mL of resin per 30 ml of cell lysate). The column was washed with 1 column volume of Wash Buffer (50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM imidazole) and eluted with 5 column volumes of Elution Buffer (50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole; 5 ml). The purified enzyme was dialyzed into Dialysis Buffer (40 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1% Igepal CO-630) and loaded on a 10 ml HiTrap Heparin HP affinity column (Cytiva) using an FPLC (AKTA pure, GE healthcare). Bound protein was eluted with a NaCl gradient in Elution Buffer ranging from 100 mM to 2 M over 5 column volumes. The eluted enzyme was dialyzed into Storage Buffer (50% glycerol, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl, 0.1% Tween-20, 0.1% Igepal CO-630, 1 mM DTT) and quantified by Bradford assay and SDS-PAGE Supplementary Figure S1.

LAMP-OSD data

LAMP-OSD data used for fitting in KinTek Explorer were generated by amplifying different amounts of GAPDH plasmid DNA using Bst-LF DNA polymerase in ‘cellular’ reagent format (13,14). Cellular reagent is a molecular biology reagent delivery system that uses dried bacteria, such as E. coli, which have been engineered to overexpress proteins of interest, directly as reagent packets in typical molecular and synthetic biology and diagnostic reactions. Most conventional and engineered enzymes, such as DNA and RNA polymerases, reverse transcriptases, ligases and restriction enzymes, can be produced as cellular reagents that upon rehydration in water can be directly substituted for their pure counterparts in standard protocols. By obviating the need for protein purification or constant cold chain, cellular reagents provide a low cost locally sustainable alternative to pure reagents. Briefly, 25 μl LAMP-OSD reactions in 1× isothermal buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) (20 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 8.8) containing 1.6 μM each of BIP and FIP primers, 0.4 μM each of B3 and F3 primers, and 0.8 μM of the loop primer, 0.8 M betaine, 0.8 mM dNTPs, 2 mM additional MgSO4, 100 nM of OSD reporter, and Bst-LF enzyme in the form of ‘cellular’ reagents, which are comprised of 2 × 107 BL21 E. coli bacteria that were induced to overexpress Bst-LF and then dried overnight in the presence of a desiccant. OSD probes were prepared for use in LAMP assays by annealing 100 nM fluorophore-labeled OSD reporter strands with a 2- to 5-fold excess of the quencher-labeled OSD strands by incubation at 95°C for 1 min followed by cooling at the rate of 0.1°C/sec to 25°C. Amplification kinetics was recorded in real-time by incubating these LAMP-OSD reactions in a LightCycler 96 real-time PCR machine (Roche, NC, USA) maintained at 65°C and measuring OSD fluorescence at intervals of 3 min.

Preparation of oligonucleotides for kinetic assays

Synthetic oligonucleotides were custom synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). Shorter oligonucleotides (<50 nt) labeled on the 5′ end with 6-FAM or Cy3 were ordered with standard desalting while longer oligos (>50 nt) were ordered with PAGE purification. Oligos were resuspended in Annealing Buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) and their concentration was determined by absorbance at 260 nm using the extinction coefficients given in Table 1. Oligos were stored at –20°C. Template oligos were annealed by mixing the two strands at a 1:1 molar ratio in Annealing Buffer, heating to 95°C, and cooling slowly to room temperature over the course of 1 h. FAM labeled primers and unlabeled templates were annealed by mixing the labeled primer and unlabeled template at a 1:1.1 molar ratio in Annealing Buffer, heating to 95°C, then cooling to room temperature over the course of 1 h. Annealed oligos were stored at –20°C.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Template | Oligo name | Sequence 5′—3′ (length in bp) | ∑260nm (M−1 cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | FAM-FIP | [6-FAM]-CGCCAGTAGAGGCAGGGATGAGGGAAACTGTGGCGTGAT (39) | 413,560 |

| FAM-F3 | [6-FAM]-GCCACCCAGAAGACTGTG (18) | 194,860 | |

| FAM-LR | [6-FAM]-TGTTCTGGAGAGCCCCGCGGCC (22) | 217,260 | |

| LT-1 | TTGGCAGCGCCAGTAGAGGCAGGGATGATGTTCTGGAGAGCCCCGCGGCCATCACGCCACAGTTTCCCGGAGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAG (100) | 940,500 | |

| LT-1C | CTGCCACCCAGAAGACTGTGGATGGCCCCTCCGGGAAACTGTGGCGTGATGGCCGCGGGGCTCTCCAGAACATCATCCCTGCCTCTACTGGCGCTGCCAA (100) | 912,700 | |

| LT-2 | CTCTCCAGAACATCATCCCTGCCTCTACTGGCGCTGCCAA (40) | 355,100 | |

| HT-1 | CCTTGGCAGCGCCAGTAGAGGCAGGGATGAGGGAAACTGTGGCGTGATGGCCGCGGGGCTCTCCAGAACATCATCCCTGCCTCTACTGGCGCTGCCAAGG (100) | 936,500 | |

| A. aegypti | FAM-BIP | [6-FAM]-TAGGTATAGACGTAGATACTCGAGCATTCCTGTAGGAACAGCAATA (46) | 492,660 |

| FAM-B3 | [6-FAM]-TTGAGTTCCGTGTAAAGTTG (20) | 215,760 | |

| FAM-LF | [6-FAM]-GCTTATTTTACTTCAGCAACTATAAT (26) | 269,860 | |

| HT-1 | TAGGTATAGACGTAGATACTCGAGCATTCCTGTAGGAACAGCAATAATTATAGTTGCTGAAGTAAAATAAGCTCGAGTATCTACGTCTATACCTA (95) | 963,300 | |

| LT-1 | TAGGTATAGACGTAGATACTCGAGCTTATTTTACTTCAGCAACTATAATTATTGCTGTTCCTACAGGAATTAAAATTTTTAGTTGATTAGCAACTTTACACGGAACTCAA (110) | 1,086,500 | |

| LT-1C | TTGAGTTCCGTGTAAAGTTGCTAATCAACTAAAAATTTTAATTCCTGTAGGAACAGCAATAATTATAGTTGCTGAAGTAAAATAAGCTCGAGTATCTACGTCTATACCTA (110) | 1,102,500 | |

| - | Cy3 Internal Standard | [Cy3]-CCGTGAGTTGGTTGGACGGCTGCGAGGC (28) | 266,800 |

Kinetic experiments

All experiments were performed at 65°C in 1× isothermal buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 8.8 at 25°C), supplemented with 1 M betaine (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and an additional 2 mM MgSO4. Unless otherwise stated, concentrations given in the main text and figure legends are concentrations after mixing. EDTA was used to quench the reaction in all experiments and the final concentration of EDTA after quenching was at least 0.2 M. Slow reactions were performed by hand mixing one solution with another at a 1:1 ratio to start the reaction then aliquots were removed into EDTA to collect time points. Fast reactions were analyzed by rapid quench on a KinTek RQF-3 instrument (KinTek Corp., Austin, TX, USA) with a circulating water bath set to 65°C. Unless otherwise noted, all experiments were performed with 0.6 M EDTA in the quench syringe and Isothermal buffer without magnesium in the drive syringes. Quenched samples were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis as previously described (15). Briefly, using a 96-well plate, 1.25 μl of quenched sample was diluted into 10 μl of HiDi Formamide (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing the Cy3 labelled internal standard for sizing (Table 1). Pre-run electrophoresis was carried out at 15 kV for 3 min, then samples were injected at 3.6 kV at 65 ºC for 4–30 s (depending on the concentration of fluorescent oligo in the sample) on an ABI3130xl instrument equipped with a 36 cm array and nanoPOP-6 polymer (Molecular Cloning Laboratories, San Francisco, CA, USA). After injection, the voltage was stepped up to a run voltage of 15 kV over 40, 15 s steps and electrophoresis was carried out for 25 min. Experiments were carried out at least three separate occasions to ensure reproducibility; the best data set is shown.

Data fitting and analysis/figure preparation

Electropherograms were analyzed with GeneMapper software 5 for peak integration and sizing/quantification was performed with a program we previously developed. (15) Preliminary conventional data fitting was performed in the software using built-in analytic functions. The equation for a linear function is y = A0 + bt, where A0 is the y value at time zero, b is the rate and t is time. The equation for a single exponential is y = A0 + A1(1 – exp(–b1t)), where A0 is the y-value at time zero, A1 is the amplitude, b1 is the decay rate and t is time. The equation for a double exponential is y = A0 + A1(1 – exp(–b1t)) + A2(1 – exp(–b2t)), where A0 is the y-value at time zero, A1 and A2 are the amplitudes of the first and second phases, b1 and b2 are the decay rates of the first and second phases, and t is time. The equation for a single exponential burst is y = A0 + A1(1 – exp(–b1t)) + b2t, where A0 is the y value at time zero, A1 is the amplitude of the exponential phase, b1 and b2 are decay rates of the exponential and linear phase, respectively, and t is time. Diagrams in the figures were prepared with Inkscape v1.2 (www.inkscape.org). KinTek Explorer software (www.kintekexplorer.com) was used in preparing figures showing kinetic data.

Data in Figures 3 and 4 were fit using a simple model for processive DNA synthesis using KinTek Explorer simulation and data fitting software v11 (www.kintekexplorer.com) (16–18) as described previously (19,20). Briefly, starting by equilibrating DNA binding with the enzyme, we then add nucleotides and model each step in processive synthesis, showing the rise and fall of each intermediate. The lines in each figure show the best fit derived by nonlinear regression based on the numerical integration of the rate equations.

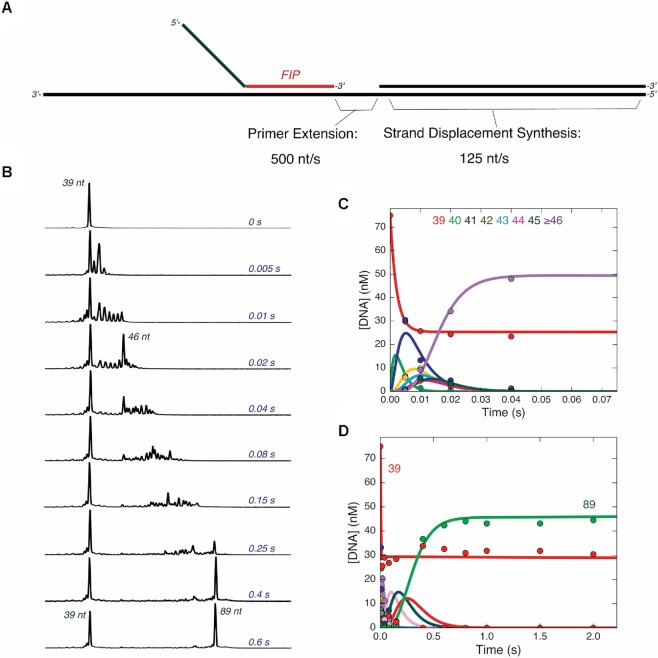

Figure 3.

Primer extension and strand displacement synthesis are fast. (A) Schematic of template DNA and primers used to measure extension. The DNA template is shown in black, consisting of LT-1 annealed to LT-2. The gap between the 3′ end of FIP and the 5′ end of LT-2 is 10 nt. (B) Rapid quench time course of strand displacement synthesis on linear DNA template. A solution of 75 nM FAM-FIP/LT-1/LT-2 and 400 nM Bst-LF polymerase was mixed with 400 μM dNTPs to start the reaction in the quench flow. Samples were quenched with EDTA and analyzed by capillary electrophoresis. For each electropherogram for each individual time point, retention time is given on the x-axis with increasing retention times from left to right, and fluorescence intensity the y-axis. Lengths of products corresponding to major peaks are shown in red. Reaction times are given on the right-hand side of the electropherograms in blue. Pausing at the 46 nt product occurs ∼3 bases before the start of the double stranded region. (C) Time course of primer extension reaction on single stranded template region. A plot of the concentration of each species from 39 to greater than or equal to 46 nt are shown, corresponding to the products formed during the primer extension reaction on the single stranded region of the template. Solid lines through the data are best fit curves to the fit by numerical integration of the rate equations in KinTek Explorer, giving an average rate of extension of 500 nt/s. (D) Time course of strand displacement synthesis reaction. A plot of the concentration of species from 39 to full length 89 nt product are shown, fit by simulation in KinTek Explorer represented by the solid curves going through the data points. The average rate of strand displacement synthesis derived from the fitting is approximately 125 nt/s.

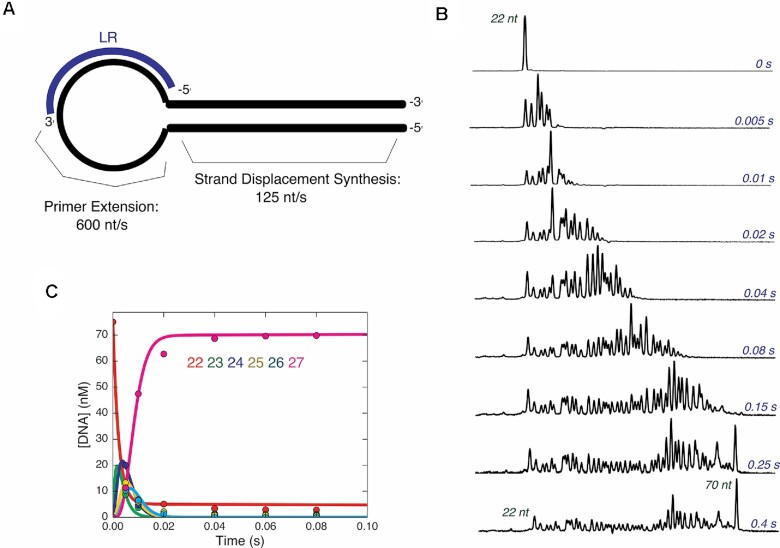

Figure 4.

Synthesis from loop primer is also fast. (A) Schematic of template DNA and primer used to measure loop primer extension. The hairpin template HT-1 is shown in black, and the FAM labeled loop primer LR is shown in blue, annealed in its approximate position in the loop region of the DNA template. (B) Rapid quench time course of strand displacement synthesis on hairpin DNA template. A solution of 75 nM FAM-LR/HT-1 and 400 nM Bst-LF polymerase was mixed with 400 μM dNTPs to start the reaction. The reaction was quenched with EDTA at various times and products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis. For each electropherogram for each individual reaction time point, retention time is given on the x-axis with increasing retention times from left to right, and fluorescence intensity the y-axis. Electropherograms from different time points are shown with sizes of prominent peaks shown in red and time points are given in blue on the right-hand side of the electropherograms. (C) Time course of primer extension reaction in single stranded hairpin region. A solution of 75 nM FAM-LR/HT-1 and 400 nM Bst-LF polymerase was mixed with 400 μM dATP, dTTP and dCTP to start the reaction in the quench flow. After various reaction times, samples were quenched with EDTA and analyzed by capillary electrophoresis. A plot of the concentration of each species from 22 to 27 nt is shown. The average rate of polymerization in this region of the template was 600 nt/s. This fast rate of polymerization in the single-stranded region is more accurately resolved in this experiment than in the experiment in (B) where all nucleotides were added.

Modeling the bulk OSD-LAMP data in Figure 5 was done in KinTek Explorer using the following minimal model as an input. Each line represents a step in the model and the forward reaction goes from left to right while the reverse reaction goes from right to left as written.

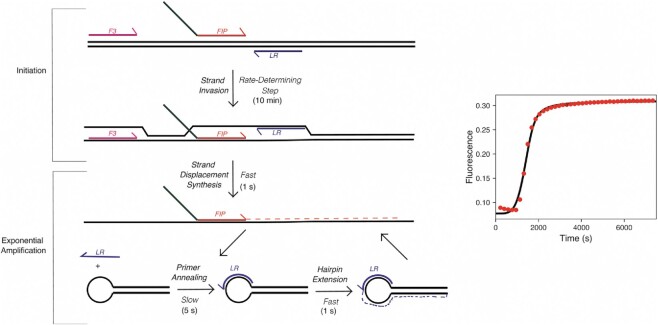

Figure 5.

Primer annealing is slow but not rate limiting while enzyme binding is fast. (A) Schematic of reaction to measure primer annealing kinetics. The hairpin template HT-1 is shown in black and the FAM-LR primer is shown in blue. Bst-LF polymerase is shown in grey surface representation from pdbid: 7k5t. (B) Time course of primer annealing, monitored by extension of LR. A solution of 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 or 0.4 μM HT-1 and 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 μM Bst-LF polymerase was mixed with 50 nM FAM-LR and 400 μM dATP, dCTP and dTTP to start the reaction. At various times the reaction was quenched with EDTA and products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis. Each concentration of template DNA is shown as a different color of data points from red at the lowest to yellow at the highest concentration. Data at each concentration are shown fit to a single exponential function. (C) Observed rate of primer annealing versus concentration of template DNA. The rates are shown fit to a linear function, giving a second order rate constant for primer binding of approximately 0.2 μM−1 s−1. (D) Schematic of reaction to measure polymerase binding to annealed primer/template kinetics. The hairpin template annealed to the FAM-LR primer are shown in black and blue, respectively. Bst-LF polymerase is shown in grey surface representation from pdbid: 7k5t. (E) Time course of polymerase binding to primer/template monitored by primer extension. A solution of 0.1–0.4 μM Bst-LF polymerase was mixed with 50 nM HT-1/FAM-LR and 400 μM dATP, dCTP and dGTP to start the reaction. At various times the reaction was quenched with EDTA and products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis. Data at a single enzyme concentration are shown since the time course of product formation does not change with increasing enzyme concentration on this timescale. Data are shown fit to a single exponential burst equation.

(1) S1 = S2

(2) S2 = P1

(3) P1 + N = P1N

(4) P1N = P1 + P2

(5) P2 + N = P2N

(6) P2N = P2 + P3

(7) P3 + N = P3N

(8) P3N + N = P3NN

(9) P3NN = P3 + P4

S1 and S2 correspond to starting materials that do not produce a fluorescence signal in the assay. All species with a P indicate products containing loops to which the OSD probes hybridize and provide a fluorescent signal in the assay. N corresponds to nucleotide binding/addition steps which we model as occurring in only two steps for simplicity. The observable function used to relate the concentration of species to a measurable signal in the reaction was defined as the sum of all P species, with an offset to account for an initial starting fluorescence value and a fluorescence scaling factor. Namely, the observable signal was modeled mathematically by the function: a1 + (b1 * (P1 + P1N + P2 + P2N + P3 + P3N + P3NN + P4)), according to the model described above. The a1 term scales the observable signal to match the starting fluorescence of the data and the b1 term scales the magnitude of the signal change going from the starting material to product. Reactions numbered 1, 2, 4, 6 and 9 were modeled as irreversible by setting reverse rate constant to 0 because in the presence of nucleotides and low concentrations of pyrophosphate, the polymerase reaction is essentially irreversible (21). Nucleotide binding rate constants (k3, k5, k7, k8) were locked at 10 μM−1 s−1 as reasonable estimates for this second order rate constant based on previous DNA polymerase studies (22–24). The reverse rates (k-3, k-5, k-7, k-8) were allowed to float as independent parameters in the fitting to afford estimates of equilibrium binding constants, i.e. K3 = k3/k-3. Initial concentrations of species were as follows: S1 = 1 × 10−7 μM; N = 1 μM. N was set at 400-fold lower concentration than used in the experiment as amplicons were approximately 400 nt in length so 1 N incorporation was used to represent 400 nucleotides incorporated into the product as an approximation. Rates for k4 and k6 were locked at 100 s−1 so that they did not limit the overall rate of the reaction. A reasonable fit to the data was obtained with k1 = 1 × 10−7 s−1, k2 = 0.02 s−1, k-3, k-5 and k-7 = 10.7 s−1, k-8 = 0.05 s−1 and k9 = 1 s−1, as shown in Figure 6. Here, we define a reasonable fit as one where the simulated curve goes through the center of the data points, supported by χ2 analysis (18). While the parameters in the model were not well constrained by the data, this particular model was chosen as it provided the bestfit with the least number of steps that can still describe the data. The simulation shows that the minimal model can account for the data with reasonable estimates of the net rate constants based on measurements of fundamental steps in the amplification reaction.

Figure 6.

Model for main kinetic steps in the LAMP reaction. Left: Schematic of LAMP reaction broken into kinetically significant steps. Template DNA is shown in black while F3, FIP, and LR primers are shown in pink, red and green, and blue, respectively. Approximate times to complete each step of the reaction are given next to each step. Right: Simulation of observed fluorescence in bulk LAMP reaction based on kinetic parameters determined in this study. Bulk LAMP OSD data are given in the red data points while the fit by simulation is given by the black line through the data points. The model, rate constants, and starting concentrations used in fitting are given in the materials and methods section.

RESULTS

Investigating primer invasion and initiation in LAMP

We began our studies by investigating the initiation phase of the LAMP reaction. As described above and in Figure 1, the primer FIP invades the dsDNA template and is then extended by the polymerase, which sets off a series of additional reactions that result in concatemer formation and exponential amplification. While this reaction can occur at either end of the growing amplicon, as a model system we chose to investigate reactions that occurred on only one half of a typical LAMP reaction. Herein we refer to initiation as encompassing FIP/BIP primer invasion and the subsequent extension steps that must occur prior to exponential amplification. A model DNA template and primers (F3, FIP and LR) were based on a LAMP assay for GAPDH that had previously been used to characterize improved Bst polymerase variants (12). We also tested our assays with a template and primers that had significantly lower GC contents, previously employed in a LAMP assay designed to detect A. aegypti in mosquito populations ((25);Supplemental Figures S3–S6).

We began by mixing a solution of 5′-[6-FAM] labelled FIP and dNTPs with a double-stranded linear template LT1/LT-1C (defined in Figure 2A and Table 1). Bst-LF polymerase was included in the reaction at 65°C. Samples were collected at various time points by stopping the reaction with EDTA, and products were resolved and quantified by capillary electrophoresis via fluorescence detection of the FAM-labeled FIP primer. The resulting electropherograms are shown in Figure 2B.

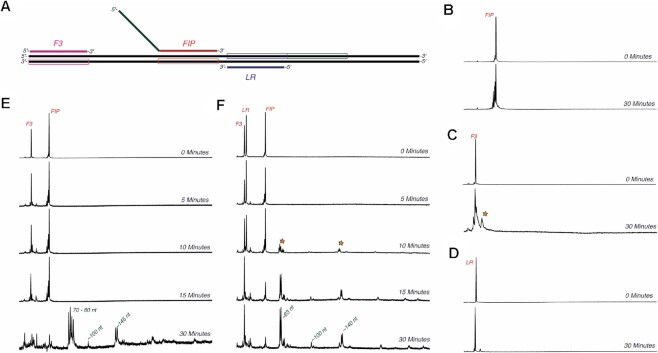

Figure 2.

Multiple primers are required for efficient LAMP initiation. (A) Schematic of template DNA and primers used to measure initiation. The strand that each primer anneals to is shown in the box around the template DNA (black) in the same color as the corresponding primer. FIP is shown annealed to the red region, however the tail of FIP in green can also anneal to the green boxed region next to the LR annealing region. (B) Initiation reaction with template DNA and FIP. Initiation reactions in (B)–(F) were performed by mixing a solution of 1 μM indicated primer(s), 250 nM template DNA LT-1/LT-1C and 600 nM Bst-LF polymerase with 400 μM dNTPs to start the reaction. Samples were quenched by mixing with EDTA. Reaction times are given in blue on the right side of each electropherogram. For each electropherogram in panels (B)–(D), retention time is given on the x-axis with increasing retention times from left to right, and fluorescence intensity the y-axis. No extension was observed on the timescale of the experiment. (C) Initiation reaction with template DNA and F3. Extension by up to 10 nt (marked with an orange star) was observed after a 30-min incubation. (D) Initiation reaction with template DNA and LR. Extension by up to 5 nt was observed after a 30-min incubation. (E) Initiation reaction with F3 and FIP. Minor extension of F3 by up to 10 nt was observed up to 15 min. Extension to full length extension products was observed after 30 min. Sizes of products are given in green next to the corresponding peaks in the electropherogram. (F) Initiation reaction with F3, LR and FIP. Extension to full length products (marked with an orange star) was observed after 10 min when all three primers were added to the reaction.

Surprisingly, after a 30-min incubation, no extension of FIP was observed. Similar experiments with F3 and LR primers were performed (Figure 2C and D), and yielded similar results, but with F3 showing extension of up to only 10 bases, much shorter than the expected full-length product (89 nt). Of course, since LAMP is typically performed with multiple primers in the same reaction, we next monitored extension of FAM-labelled primers when both F3 and FIP were added to the linear DNA template (Figure 2E). In this experiment, extension to full length products were finally observed after 30 min.

Since our model LAMP GAPDH reaction also includes a loop primer, we repeated the experiment with all 3 primers: LR, F3 and FIP, and the results are shown in Figure 2F. Full-length product formation was observed after only 10 min. Control experiments without added template (Supplementary Figure S2) showed that most of these products did not form in the absence of template, and so the observed product peaks were likely specific amplification products. This was somewhat surprising, in that in the original paper the proposed mechanism suggested that loop primers should participate only in the exponential phase of amplification (26), and not necessarily during initiation. To test the generality of our findings, we also measured initiation on a template previously used to detect A. aegypti from mosquito samples (25) (Supplementary Figure S3). Full-length extension from BIP was observed after a 30-min incubation, but most of the product formed corresponded to erroneous amplification, as the major peak was also detected when no template was added (Supplementary Figure S4). It should be noted that background amplification in the absence of template is a common problem for LAMP (27,28). Adding the B3 primer accelerated the reaction to the point where a full-length product was observed after 10–15 min, although with low amplitude. When all three primers were added, a product peak corresponding to full-length product was observed after only 5 min. Taken together these results show that the strand invasion/initiation reaction of LAMP is slow but is greatly accelerated by addition of all three primers to the half-reaction.

It should be noted that the observed reaction patterns align with what is also seen in a bulk LAMP reaction: when all primers are present a product is seen after 5 min, and this product is then rapidly, exponentially amplified on a 15- to 30-min timescale. To relate the single turnover experiments in this paper to bulk GAPDH LAMP amplifications involving multiple turnovers, we ultimately created a model in KinTek Explorer which reasonably accounts for the main aspect of LAMP amplification curves as described below.

Kinetic analysis of strand displacement synthesis

After LAMP is initiated, strand displacement synthesis during exponential amplification occurs throughout increasingly large concatemers. We investigated the kinetics of primer extension and strand displacement within both single-stranded and double-stranded regions (Figure 3). In these experiments, FIP was annealed to a linear template leaving a 10 nt single-stranded gap prior to encountering a double-stranded DNA region. The extension and displacement reaction proved to be orders of magnitude faster than the primer invasion initiation reaction, so the experiment was performed in a quench flow instrument to resolve the kinetics of polymerization during a single turnover. Polymerase extends the primer in the single-stranded region at rates of ∼500 nt per second up to 3 nt before hitting the double stranded region, at which point the rate slowed to an average of 125 nt/s as strand displacement synthesis ensued. To our knowledge, these are the first single turnover kinetic experiments on Bst-LF at its optimal temperature of 65°C, where it should act as a fast and processive polymerase. Results with the A. aegypti linear template proved comparable (Supplementary Figure S5). Our data establish that primer extension and strand displacement activities are not rate-limiting for product formation in LAMP.

Hairpin primer extension is also fast

Next, we investigated whether extension from the loop primers would be rate-limiting. Due to the odd structure and lack of similar experiments in the literature, it was unknown if a hairpin structure would affect the rate of polymerization. Quench flow experiments were performed by mixing dNTPs with a solution GAPDH FAM-LR/HT-1 (Table 1) that had been preincubated with Bst-LF (Figure 4). The average rate of polymerization through single-stranded region was around 600 nt per second while the strand displacement rate was around 125 nucleotides per second on average, comparable to what was previously observed with the linear template. Some stalling was observed in regions of high GC content (as demonstrated by intermediate peaks that formed then slowly disappeared on the timescale of the experiment). This experiment was repeated with the A. aegypti hairpin template (Supplementary Figure S6), which again showed fast polymerization kinetics, although the amplitude of product formation was lower than was seen for the GAPDH substrates, likely due to low GC content (27%) of the loop primer, which could affect the fraction of primer annealed to the template under our conditions leading to a lower amount of product formed.

Primer binding is slow but not rate-limiting

Since polymerization with both linear templates and hairpins was fast even during strand displacement synthesis, we next investigated whether primer or polymerase binding steps limited the overall rate of the reaction (Figure 5). We first measured the kinetics of primer extension under conditions where annealing to a single-stranded loop template could be rate-limiting (Figure 5A). The primer/loop species would be similar to the substrate formed after F3 elongation and strand displacement leading to the exponential amplification phase. A solution containing Bst polymerase and hairpin template DNA (in molar excess) was mixed with FAM-LR and dNTPs to initiate polymerization, and the kinetics of extension were monitored as above. Primer extension in these experiments should be fast, as shown above (Figure 3), and thus observed kinetics should be rate-limited by annealing of the primer to the single-stranded loop region. A linear increase in the rate of product formation was observed as a function of increasing template DNA concentrations, with a second order rate constant of ∼0.2 μM−1 s−1 (Figure 5B, C). With this second order rate constant and the concentration of primers typically used in LAMP reactions, the net pseudo-first-order rate of primer annealing to the single stranded loop is considerably slower than rates of polymerization. However, the rate of primer binding is still much faster than rates of primer invasion and initiation (Figure 2), in which the primer invades a double stranded template region on a 5–10 min timescale. We also tested primer annealing rates on a linear, single stranded template, and had similar results (Supplementary Figure S7).

Although primer binding in these experiments might limit the observed rate, another possibility is that polymerase interactions with the primer/template complex are slow and the order of binding (enzyme or primer first) is not known. To measure the net rate of polymerase binding to the annealed primer/template DNA, we mixed solutions of Bst polymerase at different concentrations with a solution containing pre-annealed primer/template. The concentration of Bst-LF polymerase was in excess and therefore should have determined the observed rate if polymerase binding was indeed rate-limiting. As seen in Figure 5E, the observed reaction occurred at a rate that was too fast to resolve on the timescale of the experiment, indicating that Bst-LF binding was much faster than the rate of primer binding, as measured in Figure 5B and C. Interestingly, the amplitude of the fast phase of product formation in Figure 5E was around 70% of what would have been expected for full product turnover, despite a large excess of enzyme. Thus, the polymerase may be bound at sites other than the 3′ end of the primer 30% of the time and would then slowly dissociate to allow binding at the primer terminus for efficient extension.

DISCUSSION

DNA amplification in LAMP is initiated when the FIP and BIP primers bind to their complementary sequences in their target nucleic acid sequences. Hybridization of FIP and BIP can be hampered when the target is double-stranded DNA or in structured RNA. While random breathing of structured nucleic acids at a typical LAMP amplification temperature (65°C) can potentially provide sufficient access to single-stranded regions for FIP and BIP primer binding, our data suggest that other LAMP primers, such as F3 and B3 (Figure 1), are crucial for efficient strand invasion by FIP and BIP. Similarly, the inclusion of additional primers (LF and LR) that target loop sequences in the amplicon stem–loop structures (26) have been shown to improve the speed and efficiency of LAMP.

The need for improved strand invasion is also apparent from studies that show improvements in the speed and efficiency of LAMP with the addition of stem primers that bind to the amplicon stem region (between the FIP and BIP binding sites; (29)) and swarm primers that target regions opposite FIP and BIP (5). Overall, our data suggest a critical role for any of a variety of accessory primers in enhancing primer invasion of double-stranded targets, presumably by facilitating strand separation of duplex DNA or RNA.

Our study has now demonstrated that the initial primer invasion step is in fact a key, rate-limiting step and that target invasion by a single primer is very inefficient. First, based on kinetic measurements on linear templates, the rate of unimpeded synthesis relative to strand displacement synthesis was reduced only by a factor of 5, and thus the rate of processive synthesis under either mode was not rate-limiting. Similarly, polymerization kinetics through hairpins was very fast and processive. The values observed are consistent with the role of Bst DNAP as an enzyme that is adept at strand displacement. Although T7 DNA polymerase with an active proofreading exonuclease cannot efficiently do strand displacement synthesis, the exonuclease-deficient variant, Sequenase, shows a ∼20 fold reduction in the rate of polymerization going from unimpeded synthesis to strand displacement synthesis (30). HIV reverse transcriptase is inhibited 100- to 1000-fold when encountering hairpins in RNA or DNA templates (at 37°C) but slowly reads through the hairpins in a reaction is dependent on the spontaneous melting of base pairs ahead of the polymerase (31,32). Our new data extend the understanding of strand displacement synthesis for DNA polymerases, which remain largely under characterized (33).

It should be noted that the Bst enzyme had some difficulties with sequences that had either high or low GC content, albeit for different reasons. While high GC content primers anneal very efficiently to the single-stranded regions of template DNA, high GC content during strand displacement synthesis in the double-stranded region next to a loop caused stalling of the polymerase as it struggled to unwind the upstream duplex. In contrast, low GC content reduces efficient annealing of the primer from which the polymerase extends and limits the amount of product that is formed even though strand-displacement synthesis is faster. This tradeoff in GC content and the efficiency of different steps of the reaction underscore the importance of optimal GC content in primer design, even in the presence of 1M Betaine. While optimal LAMP primer design frequently must be determined via iterative feedback with experiments, GC contents that are either too high (>65%) or too low (<30%) may inhibit polymerization. The assays reported here can help to find the optimal GC content.

Second, measurements to determine whether primer annealing to a single-stranded template or polymerase binding to a pre-annealed primer/template could limit the rate of turnover in the exponential phase of LAMP revealed that primer annealing (with a second order rate constant of 0.2 μM−1 s−1) is much slower than polymerase binding. Although the second-order rate constant is seemingly slow, recent estimates of average primer hybridization rates determined by a graphene biosensor are almost identical to our measurement (34). Our observed rate of primer annealing to a single-stranded region is at least 50- to 100-fold faster than the rate primer invasion of a double-stranded template, so primer annealing does not limit the overall rate of the amplification reaction. Forming single-stranded templating regions for primer binding is therefore a key feature in fast amplification during the exponential phase of the reaction.

A recent study developed a kinetic model for the exponential phase of LAMP, but did not detail the steps involved in initiating amplification (35). Similarly, others have proposed more complicated models based on investigating the distribution of different concatemer lengths and the effect on exponential amplification (11). Another study used digital LAMP (dLAMP) to determine the role of non-specific amplification and in turn optimize conditions to achieve more specific amplification (10). Our study extends this work, by breaking the reaction down into simple steps and advancing a fundamental kinetic scheme for LAMP. The value of this approach can be seen in comparison with a study that optimized LAMP to detect 35Sp and NOSt in transgenic maize, which found that loop primers were able to substitute for displacing primers thereby corroborating our results (36).

Overall, we have broken down the LAMP reaction into its major kinetic steps, as summarized in Figure 6. To demonstrate the connection between our kinetic experiments and the fluorescence readout from the OSD probes (6) in the bulk LAMP reaction we set up a simulation in KinTek Explorer (16,17) using the model laid out in the Materials and Methods section. The first initiation steps were made to be rate-limiting, followed by exponential amplification from the products of initiation. Initial concentrations were set up to mimic the conditions used in the bulk LAMP assay, with a femtomolar concentration of input template DNA. The output observable was defined to represent the amount of product formed and was related to the OSD assay by the number of loops to which the OSD probe binds to. Although the fitted rate constants are not uniquely defined by the data, the agreement between the data and the model show that we have captured the essence of a complicated series of reactions in a few simple kinetic steps.

This model provides a ready way to begin to understand and improve LAMP reactions. For example, it predicts that heat denaturation of template nucleic acid should provide better access to the rate-limiting primer invasion step. In this regard, we have previously shown that LAMP can be accelerated by performing amplification with improved polymerase variants at a higher temperature (72–74°C) (12). Similarly, the acceleration of LAMP by chaotropes (urea, guanidinium) that denature DNA secondary and tertiary structures (37,38), might be partly due to facilitation of primer invasion during both initiation and in the formation of foldback structures during exponential amplification (i.e. binding of FIP, BIP, LF and LR). Phosphorothioate modifications are thought to enhance LAMP, particularly at lower temperatures, by improving the formation of stem loops from duplex ends and enhancing subsequent primer binding (39). In fact, the inclusion of both chaotropes and phosphorothioate primers enables LAMP to proceed even at low temperatures, such as 40°C, where the rate-limiting barrier of primer invasion would be otherwise very difficult to overcome (39).

While our kinetic model retrodicts many empirical achievements, it also provides a potential route forward to a more quantitative understanding of how to design LAMP amplicons and primers for more facile amplification. Unlike PCR, where primer design has been relegated to predictive algorithms, the generation of optimal LAMP primers still currently relies heavily on experimental trials. As we further include kinetic data on the formation of foldback structures, we will work towards a more complete, and predictive, kinetic model.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The expression plasmid (pAtetO_6xHis-Bst-LF) used in this study has been deposited to Addgene (https://www.addgene.org/145799/) with the full sequence of the plasmid.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Tyler L Dangerfield, Department of Molecular Biosciences, College of Natural Sciences, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA.

Inyup Paik, Department of Molecular Biosciences, College of Natural Sciences, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA; Center for Systems and Synthetic Biology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA.

Sanchita Bhadra, Department of Molecular Biosciences, College of Natural Sciences, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA; Center for Systems and Synthetic Biology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA.

Kenneth A Johnson, Department of Molecular Biosciences, College of Natural Sciences, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA.

Andrew D Ellington, Department of Molecular Biosciences, College of Natural Sciences, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA; Center for Systems and Synthetic Biology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Support for this work at the University of Texas at Austin was received from the Welch Foundation [F-1654]; National Institutes of Health [1R01EB027202-01A1, 3R01EB027202-01A1S1 to A.D.E.]; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [NIH R01AI163336, NIH R01AI110577 to K.A.J.]. Funding for open access charge: Welch Foundation [F-1654]; National Institutes of Health [1R01EB027202-01A1, 3R01EB027202-01A1S1 to A.D.E.]; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [NIH R01AI163336, NIH R01AI110577 to K.A.J.].

Conflict of interest statement. K.A.J. is president of KinTek Corporation, which provided the RQF-3 rapid quench flow instrument and KinTek Explorer software used in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Notomi T., Okayama H., Masubuchi H., Yonekawa T., Watanabe K., Amino N., Hase T.. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000; 28:E63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Obande G.A., Banga Singh K.K.. Current and future perspectives on isothermal nucleic acid amplification technologies for diagnosing infections. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020; 13:455–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao X., Li Y., Wang L., You L., Xu Z., Li L., He X., Liu Y., Wang J., Yang L.. Development and application of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification method on rapid detection Escherichia coli O157 strains from food samples. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2010; 37:2183–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krõlov K., Frolova J., Tudoran O., Suhorutsenko J., Lehto T., Sibul H., Mäger I., Laanpere M., Tulp I., Langel Ü.. Sensitive and rapid detection of Chlamydia trachomatis by recombinase polymerase amplification directly from urine samples. J. Mol. Diag. 2014; 16:127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martineau R.L., Murray S.A., Ci S., Gao W., Chao S.H., Meldrum D.R.. Improved performance of loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays via swarm priming. Anal. Chem. 2017; 89:625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jiang Y.S., Bhadra S., Li B., Wu Y.R., Milligan J.N., Ellington A.D.. Robust strand exchange reactions for the sequence-specific, real-time detection of nucleic acid amplicons. Anal. Chem. 2015; 87:3314–3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aach J., Church G.M.. Mathematical models of diffusion-constrained polymerase chain reactions: basis of high-throughput nucleic acid assays and simple self-organizing systems. J. Theor. Biol. 2004; 228:31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen J.J., Li K.T.. Analysis of PCR kinetics inside a microfluidic DNA amplification system. Micromachines (Basel). 2018; 9:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mehra S., Hu W.S.. A kinetic model of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005; 91:848–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rolando J.C., Jue E., Barlow J.T., Ismagilov R.F.. Real-time kinetics and high-resolution melt curves in single-molecule digital LAMP to differentiate and study specific and non-specific amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 48:e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaur N., Thota N., Toley B.J.. A stoichiometric and pseudo kinetic model of loop mediated isothermal amplification. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020; 18:2336–2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paik I., Ngo P.H.T., Shroff R., Diaz D.J., Maranhao A.C., Walker D.J.F., Bhadra S., Ellington A.D.. Improved bst DNA polymerase variants derived via a machine learning approach. Biochem. 2021; 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bhadra S., Pothukuchy A., Shroff R., Cole A.W., Byrom M., Ellefson J.W., Gollihar J.D., Ellington A.D.. Cellular reagents for diagnostics and synthetic biology. PLoS One. 2018; 13:e0201681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bhadra S., Nguyen V., Torres J.A., Kar S., Fadanka S., Gandini C., Akligoh H., Paik I., Maranhao A.C., Molloy J.et al.. Producing molecular biology reagents without purification. PLoS One. 2021; 16:e0252507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dangerfield T.L., Huang N.Z., Johnson K.A.. High throughput quantification of short nucleic acid samples by capillary electrophoresis with automated data processing. Anal. Biochem. 2021; 629:114239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson K.A., Simpson Z.B., Blom T.. FitSpace Explorer: an algorithm to evaluate multidimensional parameter space in fitting kinetic data. Anal. Biochem. 2009; 387:30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnson K.A., Simpson Z.B., Blom T.. Global Kinetic Explorer: a new computer program for dynamic simulation and fitting of kinetic data. Anal. Biochem. 2009; 387:20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson K.A. Kinetic Analysis for the New Enzymology: Using computer simulation to learn kinetics and solve mechanisms. 2019; Austin, USA: KinTek Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kati W.M., Johnson K.A., Jerva L.F., Anderson K.S.. Mechanism and fidelity of HIV reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992; 267:25988–25997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jin Z., Leveque V., Ma H., Johnson K.A., Klumpp K.. Assembly, purification, and pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of active RNA-dependent RNA polymerase elongation complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2012; 287:10674–10683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shock D.D., Freudenthal B.D., Beard W.A., Wilson S.H.. Modulating the DNA polymerase β reaction equilibrium to dissect the reverse reaction. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017; 13:1074–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dangerfield T.L., Johnson K.A.. Conformational dynamics during high-fidelity DNA replication and translocation defined using a DNA polymerase with a fluorescent artificial amino acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2021; 296:100143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dangerfield T.L., Kirmizialtin S., Johnson K.A.. Conformational dynamics during misincorporation and mismatch extension defined using a DNA polymerase with a fluorescent artificial amino acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2022; 298:101451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dahlberg M.E., Benkovic S.J.. Kinetic mechanism of DNA polymerase I(Klenow fragment): identification of a second conformational change and evaluation of the internal equilibrium constant. Biochemistry. 1991; 30:4835–4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bhadra S., Riedel T.E., Saldana M.A., Hegde S., Pederson N., Hughes G.L., Ellington A.D.. Direct nucleic acid analysis of mosquitoes for high fidelity species identification and detection of Wolbachia using a cellphone. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018; 12:e0006671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nagamine K., Hase T., Notomi T.. Accelerated reaction by loop-mediated isothermal amplification using loop primers. Mol. Cell. Probes. 2002; 16:223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Minero G.A.S., Nogueira C., Rizzi G., Tian B., Fock J., Donolato M., Strömberg M., Hansen M.F.. Sequence-specific validation of LAMP amplicons in real-time optomagnetic detection of dengue serotype 2 synthetic DNA. Analyst. 2017; 142:3441–3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ooi K.H., Liu M.M., Moo J.R., Nimsamer P., Payungporn S., Kaewsapsak P., Tan M.H.. A sensitive and specific fluorescent RT-LAMP assay for SARS-CoV-2 detection in clinical samples. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022; 11:448–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gandelman O., Jackson R., Kiddle G., Tisi L.. Loop-mediated amplification accelerated by stem primers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011; 12:9108–9124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhu Y., Trego K.S., Song L., Parris D.S.. 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA polymerase modulates its strand displacement activity. J. Virol. 2003; 77:10147–10153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Suo Z., Johnson K.A.. RNA secondary structure switching during DNA synthesis catalyzed by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Biochemistry. 1997; 36:14778–14785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Suo Z.C., Johnson K.A.. DNA secondary structure effects on DNA synthesis catalyzed by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998; 273:27259–27267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Malik O., Khamis H., Rudnizky S., Marx A., Kaplan A.. Pausing kinetics dominates strand-displacement polymerization by reverse transcriptase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:10190–10205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xu S., Zhan J., Man B., Jiang S., Yue W., Gao S., Guo C., Liu H., Li Z., Wang J.et al.. Real-time reliable determination of binding kinetics of DNA hybridization using a multi-channel graphene biosensor. Nat. Commun. 2017; 8:14902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Savonnet M., Aubret M., Laurent P., Roupioz Y., Cubizolles M., Buhot A.. Kinetics of isothermal dumbbell exponential amplification: effects of mix composition on LAMP and its derivatives. Biosensors (Basel). 2022; 12:346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hardinge P., Kiddle G., Tisi L., Murray J.A.H.. Optimised LAMP allows single copy detection of 35Sp and nost in transgenic maize using bioluminescent Assay in real time (BART). Sci. Rep. 2018; 8:17590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raghunathan S., Jaganade T., Priyakumar U.D.. Urea-aromatic interactions in biology. Biophys. Rev. 2020; 12:65–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Paik I., Bhadra S., Ellington A.D.. Charge engineering improves the performance of bst DNA polymerase fusions. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022; 11:1488–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cai S., Jung C., Bhadra S., Ellington A.D.. Phosphorothioated primers lead to loop-mediated isothermal amplification at low temperatures. Anal. Chem. 2018; 90:8290–8294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The expression plasmid (pAtetO_6xHis-Bst-LF) used in this study has been deposited to Addgene (https://www.addgene.org/145799/) with the full sequence of the plasmid.