Abstract

To develop a new strategy to control candidiasis, we examined in vivo the anticandidal effects of a synthetic lactoferrin peptide, FKCRRWQWRM (peptide 2) and the peptide that mimics it, FKARRWQWRM (peptide 2′). Although all mice that underwent intraperitoneal injection of 5 × 108 Candida cells with or without peptide 2′ died within 8 or 7 days, respectively, the survival times of mice treated with 5 to 100 μg of intravenous peptide 2 per day for 5 days after the candidal inoculation were prolonged between 8.4 ± 2.9 and 22.4 ± 3.6 days, depending on the dose of peptide 2. The prolongation of survival by peptide 2 was also observed in mice that were infected with 1.0 × 109 Candida albicans cells (3.2 ± 1.3 days in control mice versus 8.2 ± 2.4 days in the mice injected with 10 μg of peptide 2 per day). In the high-dose inoculation, a combination of peptide 2 (10 μg/day) with amphotericin B (0.1 μg/day) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (0.1 μg/day) brought prolonged survival. With a combination of these agents, 60% of the mice were alive for more than 22 days. Correspondingly, peptide 2 activated phagocytes inducing inducible NO synthase and the expression of p47phox and p67phox, and peptide 2 increased phagocyte Candida-killing activities up to 1.5-fold of the control levels upregulating the generation of superoxide, lactoferrin, and defensin from neutrophils and macrophages. These findings indicated that the anticandidal effects of peptide 2 depend not only on the direct Candida cell growth-inhibitory activity, but also on the phagocytes' upregulatory activity, and that combinations of peptide 2 with GM-CSF and antifungal drugs will help in the development of new strategies for control of candidiasis.

Candida albicans is a common commensal organism that occasionally causes opportunistic infections (38). As shown by the increased number of fungal infections in AIDS, the frequency of candidiasis has rapidly increased during the last 2 decades (7, 8, 45, 48). In addition to AIDS, immunosuppression is induced by treatments of solid malignant tumors, lymphoproliferative disorders, and organ transplantation. In immunocompromised patients, Candida cells easily invade the host's organs and multiply, causing lethal damage to the lungs, kidneys, liver, and intestines.

The prevention and treatment of candidal infection have therefore become important for immunocompromised patients. Although the host's defense system against Candida cells has not yet been completely clarified, it has been reported that both humoral and cellular immunities contribute to protection against Candida cells (14, 51). In the former, antibodies to Candida cell antigens enhance phagocytosis of neutrophils and macrophages (30, 36). Salivary proteins, such as secretory immunoglobulin A, secretory components, histatins, lysozyme, lactoferrin, transferrin, lactoperoxidase, mucins, and defensins have also been nominated as the humoral agents that prevent Candida cell adhesion and growth in the oropharyngeal cavity (21, 33, 34, 49, 50, 54, 57, 59, 63), whereas cellular agents, such as neutrophils, macrophages, and T and NK cells, play important roles in the front line against Candida cells, exhibiting phagocytosis and killing (17, 32). For sufficient phagocytosis, opsonization of Candida cells is required (26, 42). However, macrophages can trap nonopsonized blastoconidia by using their mannose receptors (18). To kill the trapped blastoconidia sufficiently, neutrophils and macrophages generate reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) and nitric oxide (NO) (16, 19, 58). The generation of ROI and NO is regulated by multiple cytokines (9, 13). Among them, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferons, and prostaglandins strongly induce NO synthase (NOS) (11, 22, 46) and activate other enzymes associated with ROI generation (27, 39, 41). However, the virulence of blastoconidia is correlated with their resistance to phagocytes (24). It has been reported that Candida cells with high levels of hyphal wall protein 1 (HWP1) and C. albicans drug resistance proteins 1 and 2 (CDR1 and -2) were resistant not only to antifungal drugs, but also to phagocytes (15, 43, 52).

Clinically, there are two types of candidiasis: body surface candidiasis, including mucocutaneous candidiasis, and deep (organ) candidiasis. Surface candidal infection is relatively easily cured, but deep candidiasis is highly resistant to antifungal drug therapy (37). To prevent and control candidal infection, extensive efforts to develop excellent antifungal drugs have been undertaken (1). If a drug that possesses high antifungal activity also shows phagocyte-activating activity, a new aspect of treatment of fungal infections will open up. Such agents are likely to be obtained by following the example provided by physiologically secreted antimicrobial proteins. Recently, it has been reported that some lactoferrin peptides exhibit a potent anti-Candida cell activity (61). Along with these approaches, we synthesized a short lactoferrin peptide, FKCRRWQWRM, and examined its influences on blastoconidia and phagocytes. We found that the peptide possessed superior activities in both kinds of cells, suggesting its usefulness for the treatment of candidiasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peptide preparation.

The lactoferrin peptide (FKCRRWQWRM; peptide 2) and the peptide it mimics (FKARRWQWRM; peptide 2′) were synthesized by Iwaki Glass Biolab Co. (Chiba, Japan) by the solid-phase method with Fmoc (9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl) as the Nα-amino-protecting group. These peptides were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography on a reverse-phase C18 column. The level of purity was >95%, as analyzed from its peak integration with high-performance liquid chromatograms at 214 nm.

Blastoconidial manipulations.

C. albicans TIMM0134 was supplied by the Department of Microbiology, Kochi Medical School, Kochi, Japan, and C. albicans KSC1 was isolated from the oral cavity of a patient with oral candidiasis, which was classified serotype A according to the criteria of Fukazawa et al. (20a). Both strains were grown in Sabouraud's dextrose agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C. The Candida cells were cultured at 37°C in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium for 16 to 20 h, and blastoconidial cells were used in all experiments.

Inoculation of Candida cells and treatment of mice.

Specific-pathogen-free inbred CBA/N female mice 8 weeks old were intraperitoneally challenged with 5 × 108 or 1 × 109 blastoconidia. From the day of the challenge, peptide 2 (5 to 100 μg/mouse), peptide 2′ (100 μg/mouse), GM-CSF (Peprotech EC Ltd, London, United Kingdom) (0.1 μg/mouse), amphotericin B (0.1 μg/mouse), combination of these, or saline was injected intravenously for 5 days. Five mice were used in each treatment.

Separation of macrophages and neutrophils.

On the 5th day after the start of treatment, 2 ml of 1% thioglycolate was injected intraperitoneally. Neutrophils and macrophages were separated from each peritoneal lavage obtained at 10 and 72 h after the injection of the thioglycolate solutions, respectively. The purity of each population was examined microscopically, and >95% purity was ascertained from the morphology.

Nitrite assay.

The separated peritoneal macrophages (105/well) were cultured in 96-well plates (Corning, Corning, N.Y.) by using Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 IU of penicillin per ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin per ml. To stimulate the macrophages, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (from Escherichia coli; Sigma, St Louis, Mo.) was added to DMEM to a concentration of 1 μg/ml. After 24 h of cultivation, the culture supernatants were collected, and the nitrite concentration in each supernatant was assayed by the Griess reaction. Briefly, equal volumes of 2% sulfanilamide in 10% phosphoric acid and 0.2% naphthylethylene diamine dihydrochloride were mixed to prepare the Griess reagent. The reagent (100 μl) was added to equal volumes of the supernatant, and the mixture was then incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The A550 of the formed chromophore was measured with a plate reader. The nitrite content was calculated with sodium nitrite as a standard.

O2− generation assay.

O2− generation was assayed by the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction method. In a 5% CO2 atmosphere, neutrophils (105/well) or peritoneal macrophages (105/well) were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in Hanks buffered saline solution containing 1 mg of NBT per ml, with or without 10−9 M phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), 10−7 M N-formyl methionyl leucyl phenylalanine (FMLP), 2.5 mg of opsonized zymosan (OZ) per ml, or heat-treated dead blastoconidia (106 cells/ml, 100°C, 30 min). The optical density at 550 nm in each well was examined with a plate reader.

Phagocytosis of neutrophils and macrophages.

C. albicans blastoconidia were labeled with 0.5 μg of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-concanavalin A (Con A) (Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (56). The FITC-labeled C. albicans cells were cocultured with effectors (neutrophils or macrophages) at a ratio of 10:1 for 1 h at 37°C. Phagocytosing cells were detected by a FACScan fluorescence-activated cell sorter (Beckton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.), and the peak intensity of the fluorescence level (arbitrary units) was determined as the phagocytic index.

Candida killing.

C. albicans blastoconidia were labeled with 51Cr (Na2CrO4) for 1 h at 37°C at a concentration of 100 μCi per 108 cells. The blastoconidia were then washed three times and used as the targets. The effectors were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, and the effectors, neutrophils or macrophages, were mixed with the 51Cr-labeled blastoconidia to give an effector/target ratio of 1:10 in a final volume of 0.2 ml/flat-bottom well. The mixtures were then incubated for 4 h at 37°C, and the isotope activity in 0.1 ml of the supernatant from each well was counted with a gamma counter. The percentage of cytotoxicity was calculated with the following formula: % cytotoxicity = [experimental release (cpm) − spontaneous release (cpm)/maximal release (cpm) − spontaneous release (cpm)] × 100, where spontaneous release is the isotope activity in the target cells incubated without effectors, and maximal release is the isotope activity in the supernatant after treatment of the blastoconidia with 0.1% Triton X-100. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate assays.

Western blotting.

After the mouse treatment indicated above, separated neutrophils and peritoneal macrophages were lysed with TNE lysis buffer (1M Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 0.5 M EDTA, 10% Nonidet P-40), and the total protein level in each sample was determined by Lowry's method. The protein level in each lysate was adjusted to 50 μg/20 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer, and the lysate samples were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting, which was performed with anti-p47phox, anti-p67phox, and anti-iNOS antibodies (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, Ky.)

Lactoferrin release from neutrophils.

Lactoferrin levels in the culture supernatants were assayed by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, microwells were coated overnight with 400-fold-diluted rabbit anti-human lactoferrin serum (Nordic Immunological Laboratories, Tilburg, The Netherlands). After blocking nonspecific reactions with PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), the samples and serially diluted standard lactoferrin were poured into the microwells and left overnight at 4°C. After a thorough washing, alkaline phosphatase-conjugated, affinity-purified rabbit anti-human lactoferrin antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratory, West Grove, Pa.) was added to each well, and the wells were incubated for 90 min at 37°C and washed. A phosphatase substrate (Sigma) was then added, and the developed color was read at 405 nm on an ELISA reader. The findings were calculated from the standard curve.

Measurement of defensin concentration.

A 10-μl aliquot of the supernatant was assayed by reversed-phase HPLC on a C18 column (4.6 by 250 nm; Nacalai Tesque, Osaka, Japan). HPLC was performed with a 20-min linear gradient from solvent A (0.05% trifluoroacetic acid [TFA], 10% acetonitrile) to solvent B (0.05% TFA and 50% acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 1.0 ml per min. Defensin was quantified by comparing the peak heights of the eluted defensin derived from the samples with that of a synthetic human defensin-1 standard (Protein Research Foundation, Osaka, Japan).

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were duplicated, and each value is shown as the mean ± standard deviation. The significance of differences between sets of data was determined by Student's t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Effects of peptide 2 on survival periods of Candida cell-injected mice.

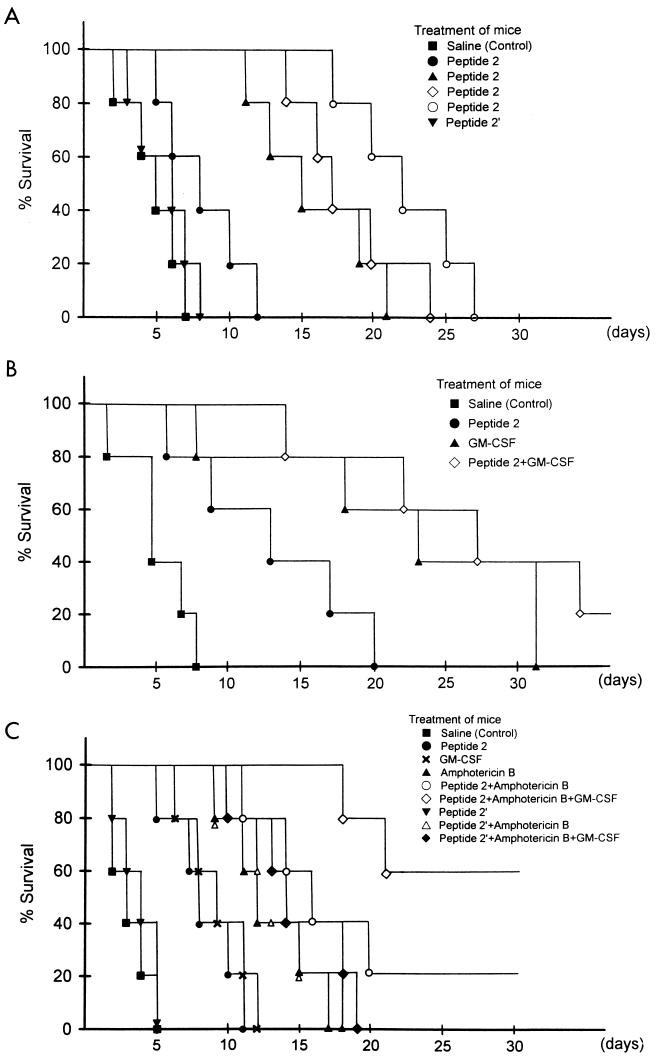

Peptide 2 dose-dependently prolonged the survival periods of Candida-infected mice (Fig. 1A). Although all control mice died within 8 or 7 days after the inoculation of 5 × 108 blastoconidia with or without 100 μg of peptide 2′ per mouse per day, mice administered 5, 10, 20, or 100 μg of peptide 2 per mouse per day, showed prolonged survival, and their survival times were 8.4 ± 2.9, 16.2 ± 3.7, 18.8 ± 3.4, and 22.4 ± 3.6 days, respectively. Compared with 10 μg of peptide 2 per mouse, a dose of 0.1 μg of GM-CSF per mouse per day more strongly suppressed lethality in mice inoculated with blastoconidia (Fig. 1B). Sixty percent of the mice administered GM-CSF survived longer than 3 weeks, while more than half of peptide 2-treated mice died within 10 days after Candida cell inoculation. When mice were treated with both GM-CSF and peptide 2, 40% of the Candida-inoculated mice survived longer than 4 weeks, and 20% survived until the end of the experiment, respectively. Furthermore, the cooperation of peptide 2 with amphotericin B and GM-CSF was observed in mice inoculated with 109 blastoconidia (Fig. 1C). Although the survival time of control mice was less than 5 days, the survival time of mice treated with peptide 2 and amphotericin B (0.1 μg/per mouse per day) was prolonged to 11 days in the mice with the shortest survival time. When Candida (109 cells)-inoculated mice were concomitantly treated with the three agents peptide 2, GM-CSF, and amphotericin B, the rate of lethality for the mice was strongly decreased; all mice survived for 18 days, and 6 of 10 mice survived until the end of the study. Peptide 2′ did not show such effects in combination with GM-CSF and amphotericin B.

FIG. 1.

Influence of peptide 2, GM-CSF, and amphotericin B on survival of Candida cell-injected mice. (A) Each mouse was intraperitoneally challenged with 5 × 108 blastoconidia and intravenously treated with saline, 5 (●), 10 (▴), 20 (◊), or 100 (○) μg of peptide 2 per day or 100 μg of peptide 2′ per day (▾) for 5 days from the day of challenge. (B) After inoculation with 5 × 108 blastoconidia, each mouse was treated with peptide 2 (10 μg/day), GM-CSF (0.1 μg/day), or both together for 5 days. (C) After inoculation with 109 blastoconidia, each mouse was treated with peptide 2 (10 μg/day), peptide 2′ (100 μg/day), GM-CSF (0.1 μg/day), amphotericin B (0.1 μg/day), peptide 2 plus amphotericin B, peptide 2′ plus amphotericin B, peptide 2 plus amphotericin B plus GM-CSF, or peptide 2′ plus amphotericin B plus GM-CSF for 5 days.

Enhancement of phagocytosis of neutrophils and macrophages by peptide 2.

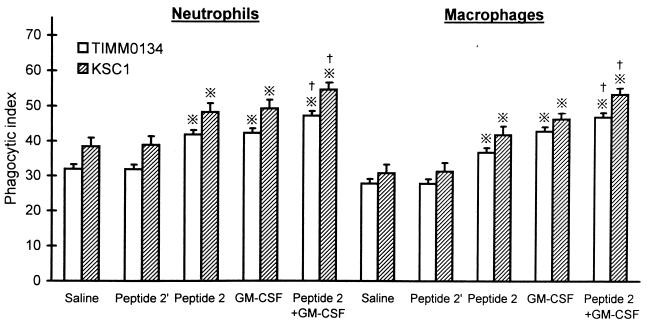

Neutrophils and macrophages phagocytosed FITC-labeled Candida cells more markedly when the donor mice were treated with peptide 2 (Fig. 2). The phagocytic activities of neutrophils and macrophages obtained from control mice were 32.1 ± 0.9 and 29.8 ± 0.8, respectively, while those of peptide 2-treated mice were 42.3 ± 1.8 and 38.6 ± 1.9, respectively (P < 0.01). The levels of phagocytosis in the peritoneal infiltrates of GM-CSF-treated mice were similar to those in the peptide 2-treated mice, and the phagocytic activities of both kinds of phagocytes, which were obtained from mice treated with both peptide 2 and GM-CSF, were higher than those of phagocytes obtained from peptide 2 or GM-CSF-treated mice (P < 0.05). However, peptide 2′ did not upregulate the phagocytic activities.

FIG. 2.

Enhancement of phagocytosis of neutrophils and macrophages by peptide 2 and GM-CSF. Peritoneal neutrophils and macrophages were obtained from mice after treatment with saline, peptide 2 (10 μg per mouse per day), GM-CSF (0.1 μg per mouse per day), or both together for 5 days, and their phagocytic indices were assayed as described in Materials and Methods. Peptide 2′ was given at 100 μg per mouse per day. ※, P < 0.01 versus saline (control) and peptide 2′; †, P < 0.05 versus peptide 2 and GM-CSF.

Influence of peptide 2 on Candida-killing activities of neutrophils and macrophages.

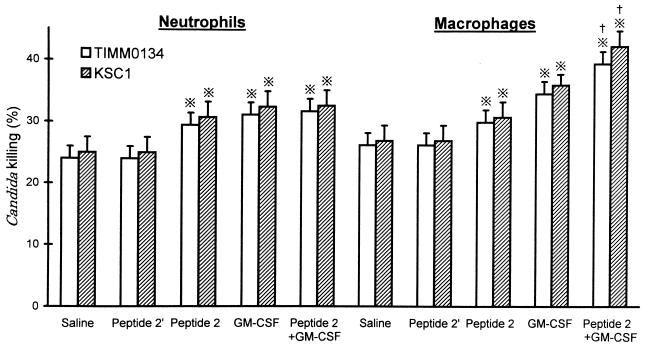

Although peptide 2′ did not increase the Candida-killing activities of phagocytes, both neutrophils and macrophages obtained from peptide 2-treated mice showed higher Candida-killing activities than those from control mice (Fig. 3). The Candida (TIMM0134)-killing activities of neutrophils and macrophages from peptide-2-injected mice were 31.3% ± 3.1% and 33.6% ± 2.6%, respectively, while those in control mice were 21.7% ± 2.8% and 23.6% ± 2.5%, respectively. With the combination of peptide 2 and GM-CSF, the Candida-killing activity of macrophages from mice that were treated with both peptide 2 and GM-CSF was significantly higher than that of macrophages from mice treated with peptide 2 or GM-CSF alone.

FIG. 3.

Enhancement of Candida-killing activities of neutrophils and macrophages by peptide 2 and GM-CSF. Peritoneal neutrophils and macrophages were obtained from mice as described in the legend to Fig. 2, and the phagocytes obtained were incubated with 51Cr-2 labeled blastoconidia to give an effector/target ratio of 1:10 for 4 h at 37°C. Killing activity was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. Peptide 2′ was given at 100 μg per mouse per day, peptide 2 was given at 10 μg per mouse per day, and GM-CSF was given at 0.1 μg per mouse per day. ※, P < 0.01 versus saline (control) and peptide 2′; †, P < 0.05 versus peptide 2 and GM-CSF.

O2− generation and expression of p47phox and p67phox in neutrophils.

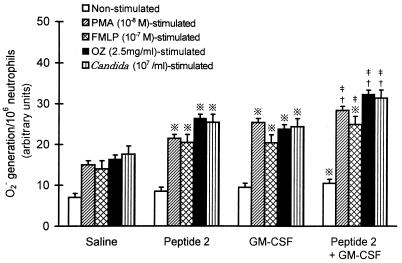

The generation of O2− from neutrophils was enhanced by in vivo treatment of mice with peptide 2 as well as GM-CSF (Fig. 4). O2− generation was clearly increased when neutrophils obtained from peptide 2-treated mice were stimulated with PMA, FMLP, OZ, or Candida cells. The upregulatory effect of in vivo treatment was also observed in GM-CSF, and the upregulated O2− levels were similar to those obtained with peptide 2. When mice underwent injection of both peptide 2 and GM-CSF, further increases in O2− generation from neutrophils were observed.

FIG. 4.

Enhancement of neutrophil O2− generation by peptide 2 and GM-CSF. Peritoneal neutrophils obtained from mice were stimulated with each indicated reagent for 1 h, and their O2− generation was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Peptide 2 was given at 10 μg per mouse per day, and GM-CSF was given at 0.1 μg per mouse per day. ※, P < 0.01; †, P < 0.001 versus saline (control); ‡, P < 0.05 versus peptide 2 and GM-CSF.

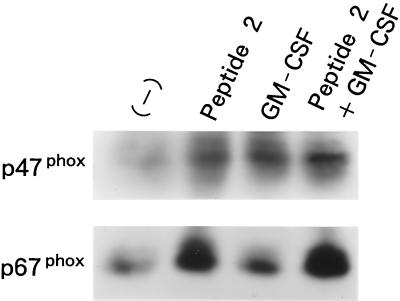

Concomitant with the increase in O2− generation by in vivo treatment with peptide 2, the expression of p47phox and p67phox was increased (Fig. 5). p47phox expression was also enhanced by GM-CSF, but upregulation of p67phox expression by the cytokine was not observed. In addition, no additive effect of peptide 2 and GM-CSF on the expression of the NADPH oxidase components was observed.

FIG. 5.

Influence of peptide 2 and GM-CSF on p47phox and p67phox expression in neutrophils. Peritoneal neutrophils obtained from mice that were treated with peptide 2 (10 μg per mouse per day) and GM-CSF (0.1 μg per mouse per day) were lysed with TNE lysis buffer, and the lysates were electrophoresed and transferred to PVP membranes. The membranes were then immunoblotted with each antibody to p47phox and p67phox.

Nitrite generation and iNOS expression in macrophages.

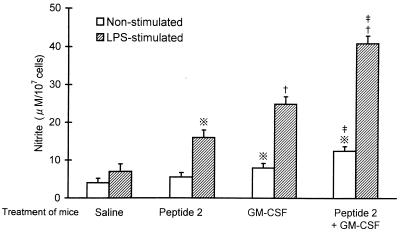

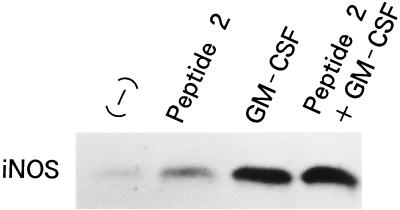

Nitrite generation from macrophages was enhanced by in vivo treatment of mice with peptide 2 and GM-CSF and further enhanced by both agents (Fig. 6). LPS-stimulated and nonstimulated macrophages from control mice generated low levels of nitrite, 7.3 ± 1.2 and 3.7 ± 1.1 μM/105 cells, respectively. Macrophages obtained from mice treated with peptide 2, GM-CSF, and peptide 2 and GM-CSF together generated 5.0 ± 1.1, 8.1 ± 1.3, and 13.6 ± 1.8 μM nitrite per 105 cells without any stimulation, and they generated 18.5 ± 2.6, 25.4 ± 3.1, and 42.5 ± 3.6 μM nitrite per 105 cells with LPS stimulation, respectively. Concomitant with the upregulation of nitrite generation, iNOS expression in macrophages was increased by both agents (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

Influence of peptide 2 and GM-CSF on nitrite generation by peritoneal macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages obtained from mice treated with peptide 2 (10 μg per mouse per day) and GM-CSF (0.1 μg per mouse per day) were cultured in the presence or absence of 1 μg of LPS per ml for 24 h, and nitrite generated from the macrophages was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. ※, P < 0.01; †, P < 0.001 versus saline (control); ‡, P < 0.05 versus peptide 2 and GM-CSF.

FIG. 7.

Influence of peptide 2 and GM-CSF on iNOS expression in macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages obtained from mice were lysed with TNE lysis buffer, and the lysates were electrophoresed and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were then immunoblotted with antibody to iNOS. Peptide 2 was given at 10 μg per mouse per day, and GM-CSF was given at 0.1 μg per mouse per day.

Release of lactoferrin and defensin from neutrophils.

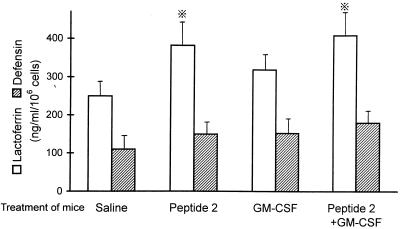

Lactoferrin release from neutrophils was upregulated by in vivo treatment of mice with peptide 2, although GM-CSF only weakly increased lactoferrin release (Fig. 8). The levels of released lactoferrin in control and peptide 2-treated mice were 253 ± 44 and 396 ± 61 ng/ml, respectively. The release of defensin was slightly increased by peptide 2 and GM-CSF, but the increases were not significant.

FIG. 8.

Upregulation of lactoferrin and defensin release from neutrophils by peptide 2 and GM-CSF. Peritoneal neutrophils were obtained from mice that were treated with peptide 2 (10 μg per mouse per day) and GM-CSF (0.1 μg per mouse per day) or untreated, and they were cultured in DMEM containing 2% FBS for 24 h at 37°C. Lactoferrin and defensin levels in the culture supernatants were assayed as described in Materials and Methods. ※, P < 0.05 versus saline (control).

DISCUSSION

Fungal infections, especially candidiasis, have gradually increased during the past few decades, corresponding with the increase in immunosuppression due to viral infections, organ transplantation, and cancer treatments (7, 45, 48). With the increase in candidiasis, highly virulent strains of C. albicans resistant to antifungal agents have appeared, and their lethality has become a serious matter in immunocompromised patients (35). For the control of infections with highly virulent C. albicans strains, potent antifungal drugs are required. However, synthesized antifungal chemicals possess generally severe inverse effects, such as impairment of liver and kidney functions (31, 47). Therefore, new strategies are required for development of physiologically adapted antifungal agents and combined treatments with multiple kinds of agents.

Recently, the antibacterial activities of natural peptides such as defensins, histatins, gramicidins, granulysin, and lactoferrin have been investigated (6, 25, 28, 44). In these investigations, it was reported that lactoferrin possessed antibacterial activities against many kinds of bacteria, such as Helicobactor pylori, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrescens, and Staphylococcus epidermidis, as well as fungi, including C. albicans (2, 60, 62). In 1992, Bellamy et al. (5) synthesized a potent antifungal lactoferrin peptide consisting of 25 amino acid residues, lactoferricin B, which lacked iron-binding activity. Following their study, we synthesized a new lactoferrin peptide, named “peptide 2,” which consists of 10 amino acid residues (55). Compared with lactoferricin B, peptide 2 appeared to have a higher anticandidal activity in vitro (55). In the present study, we examined the in vivo effects of peptide 2.

Peptide 2 dose-dependently prolonged the survival periods of the Candida-inoculated mice in cooperation with GM-CSF and amphotericin B. Of the mice that were injected with a high dose (109 cells) of C. albicans, more than half (60%) survived when they underwent combined treatment with the three agents, although all mice without any antifungal treatment died within 5 days after injection of C. albicans. As reported previously, peptide 2 inhibits growth of C. albicans by suppressing glucose incorporation and DNA and protein syntheses (55). Differing from peptide 2, amphotericin B binds to the membrane sterols of fungal cells, causing impairment of their barrier function and loss of cell constituents (4). The difference in the antifungal actions of peptide 2 and amphotericin B suggests the cooperation of both agents. In fact, we ascertained previously that peptide 2 inhibited growth of amphotericin B-resistant strains (55). These previous and present study findings recommend a combined use of peptide 2, GM-CSF, and antifungal chemicals such as miconazole, fluconazole, and/or nystatin for control of infections with highly virulent Candida strains.

The in vivo cooperation of peptide 2 with GM-CSF against Candida cells indicates a role of peptide 2 in the activation of phagocytes. As expected, the killing activities of neutrophils and macrophages obtained from the mice treated with peptide 2 were increased to about 1.5-fold of those from untreated mice. Accordingly, the levels of O2− generated by neutrophils obtained from the peptide 2-injected mice were increased to about twofold those of controls. These upregulations were confirmed by the enhanced expression of the components of NADPH oxidase, p47phox and p67phox. In the upregulation of O2− generation, Peptide 2 appears to activate many signal pathways, including the protein kinase C pathway, because the enhanced O2− generation was observed in all O2− inducers, PMA, FMLP, and OZ. In addition to the increase in neutrophil O2− generation, iNOS expression and nitrite generation in macrophages were upregulated by peptide 2. These upregulations in neutrophils and macrophages appear to result from both the direct and indirect actions of peptide 2. Previously, we ascertained that peptide 2 primed in vitro neutrophils to generate O2− (55), and peptide 2 induced lactoferrin secretion from neutrophils and GM-CSF release from neutrophils and macrophages (data not shown). Therefore, the upregulation of O2− and nitrite generation by peptide 2 appears to have partially resulted from the priming and partially resulted from indirect induction via the autocrinal and paracrinal cytokines. In candidal infections, multiple kinds of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, gamma interferon, interleukin-2, GM-CSF, and interleukin-6, are generated from leukocytes, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells (3, 20). When peptide 2 is administered under such circumstances, the cytokine generation level is increased further, and activation of neutrophils and macrophages as well as NK cells and CD4+ T cells is expected.

GM-CSF is one of the cytokines that strongly activates neutrophils and macrophages (10, 40). GM-CSF enhances neutrophil chemotaxis by increasing diacylglycerol generation, enhances phagocytosis by increasing FcR III expression, and enhances killing via increasing O2− generation and cytokine release (12, 23, 29, 53). Therefore, combinations of GM-CSF with antifungal agents in fungal infections appear to be reasonable. The findings of the present study show that combined administration of GM-CSF with peptide 2 and amphotericin B strongly reduced the lethality of Candida-inoculated mice and suggest a new strategy for control of candidiasis.

The mechanism of the antifungal activity and the pharmodynamics of peptide 2 have not yet been sufficiently explored. To establish a reasonable combined treatment of candidal infections with peptide 2 and other agents, the antifungal mechanism of peptide 2, including its influence on CDR1, CDR2, HWP1, and the enhanced filamentous growth 1 gene, which regulate candidal virulence, remains to be studied.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abruzzo G K, Flattery A M, Gill C J, Kong L, Smith J G, Pikounis V B, Balkovec J M, Bouffard A F, Dropinski J F, Rosen H, Kropp H, Bartizal K. Evaluation of the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872): efficacies in mouse models of disseminated aspergillosis, candidiasis, and cryptococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2333–2338. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilera O, Andres M T, Heath J, Fierro J F, Douglas C W. Evaluation of the antimicrobial effect of lactoferrin on Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, and Prevotella nigrescens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;21:29–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashman R B, Papadimitriou J M. Production and function of cytokines in natural and acquired immunity to Candida albicans infection. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:646–672. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.646-672.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barwicz J, Tancrede P. The effect of aggregation state of amphotericin-B on its interactions with cholesterol- or ergosterol-containing phosphatidylcholine monolayers. Chem Phys Lipids. 1997;85:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(96)02652-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellamy W, Takase M, Wakabayashi H, Kawase K, Tomita M. Antibacterial spectrum of lactoferricin B, a potent bactericidal peptide derived from the N-terminal region of bovine lactoferrin. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;73:472–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb05007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bercier J G, Al-Hashimi I, Haghighat N, Rees T D, Oppenheim F G. Salivary histatins in patients with recurrent oral candidiasis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28:26–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb01990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergmann O J. Oral infections and fever in immunocompromised patients with haematologic malignancies. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:207–213. doi: 10.1007/BF01965262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berrouane Y F, Herwaldt L A, Pfaller M A. Trend in antifungal use and epidermiology of nosocomial yeast infections in a university hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:531–537. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.531-537.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhagat K, Vallance P. Effects of cytokines on nitric oxide pathways in human vasculature. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1999;8:89–96. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199901000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchard D K, Michelini-Norris M B, Djeu J Y. Production of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by large granular lymphocytes stimulated with Candida albicans: role in activation of human neutrophil function. Blood. 1991;77:2259–2265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bories P N, Campillo B, Scherman E. Up-regulation of nitric oxide production by interferon-gamma in cultured peritoneal macrophages from patients with cirrhosis. Clin Sci. 1999;97:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capsoni F, Bonara P, Minonzio F, Ongari A M, Colombo G, Rizzardi G P, Zanussi C. The effect of cytokines on human neutrophil Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1991;34:115–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapple I L. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;24:287–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corrigan E M, Clancy R L, Dunkley M L, Eyers F M, Beagley K W. Cellular immunity in recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:574–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowen L E, Sanglard D, Calabrese D, Sirjusingh C, Anderson J B, Kohn L M. Evolution of drug resistance in experimental populations of Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1515–1522. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1515-1522.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decker T, Lohmann-Matthes M L, Baccarini M. Heterogeneous activity of immature and mature cells of the murine monocyte-macrophage lineage derived from different anatomical districts against yeast-phase Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1986;54:477–486. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.2.477-486.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deepe G S, Bullock W E. Immunological aspects of fungal pathogenesis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:567–579. doi: 10.1007/BF01967211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falipe I, Bochio E E, Martins N B, Pacheco C. Inhibition of macrophage phagocytosis of Escherichia coli by mannnose and mannan. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1991;24:919–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fierro I M, Barja-Fidalgo C, Cunha F Q, Ferreira S H. The involvement of nitric oxide in the anti-Candida albicans activity of rat neutrophils. Immunology. 1996;89:295–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filler S G, Pfunder A S, Spellberg B J, Spellberg J P, Edwards J E., Jr Candida albicans stimulates cytokine-production and leukocyte adhesion molecule expression by endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2609–2617. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2609-2617.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Fukazawa Y, Shinoda T, Tsuchiya T. Response and specificity of antibodies for Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:754–763. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.3.754-763.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gururaja T L, Levine J H, Tran D T, Naganagowda G A, Ramalingam K, Ramasubbu N, Levine M J. Candidacidal activity prompted by N-terminus histatin-like domain of human salivary mucin (MUC7)1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1431:107–119. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton L C, Warner T D. Interactions between inducible isoforms of nitric oxide synthase and cyclo-oxygenase in vivo: investigations using the selective inhibitors, 1400W and celecoxib. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:335–340. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanneman B, Kreutz M, Rehm A, Andreesen R. Effect of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor treatment on phenotype, cytokine release and cytotoxicity of circulating blood monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. Br J Haematol. 1998;102:1197–1203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasan K C, Mandell G, Coleman E, Wu G. Influence of fluconazole at subinhibitory concentrations on cell surface hydrophobicity and phagocytosis of Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;183:89–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb08938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haynes R J, Tighe P J, Dua H S. Antimicrobial defensin peptides of the human ocular surface. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:737–741. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.6.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagaya K, Fukazawa Y. Murine defense mechanism against Candida albicans infection. II. Opsonization, phagocytosis, and intracellular killing of C. albicans. Microbiol Immunol. 1981;25:807–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1981.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapp A, Zeck-Kapp G, Danner M, Luger T A. Human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: an effective direct activator of human polymorphonuclear neutrophilic granulocytes. J Investig Dermatol. 1988;91:49–55. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12463288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krensky A M. Granulysin: a novel antimicrobial peptide of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kudeken N, Kawakami K, Saito A. Mechanisms of the in vitro fungicidal effects of human neutrophils against Pencillium marneffei induced by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;119:472–478. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lal S, Mistuyama M, Miyaat M, Ogata N, Amako K, Komoto K. Pulmonary defence mechanism in mice. A comparative role of alveolar macrophages and polymorphonuclear cells against infection with Candida albicans. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1986;19:127–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamb K A, Washington C, Davis S S, Denyer S P. Toxicity of amphotericin B emulsion to cultured canine kidney cell monolayers. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1991;43:522–524. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1991.tb03529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehmann P F. Immunology of fungal infections in animals. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1985;10:33–69. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(85)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehrer R I, Ganz T, Szklarek D, Selsted M E. Modulation of the in vitro candidacidal activity of human neutrophil defensins by target cell metabolism and divalent cations. J Clin Investig. 1988;81:1829–1835. doi: 10.1172/JCI113527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenander-Lumikari M. Inhibition of Candida albicans by the peroxidase/SCN-/H2O2 system. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1992;7:315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1992.tb00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lopez-Ribot J L, McAtee R K, Perea S, Kirkpatrick W R, Rinaldi M G, Patterson T F. Multiple resistant phenotypes of Candida albicans coexist during episodes of oropharyngeal candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1621–1630. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maródi L, Tournay C, Káposzta R, Johnston R B, Jr, Moguilevsky N. Augmentation of human macrophage candidacidal capacity by recombinant human myeloperoxidase and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2750–2754. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2750-2754.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marr K A, White T C, van Burik J A, Bowden R A. Development of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans causing disseminated infection in a patient undergoing marrow transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:908–910. doi: 10.1086/515553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCullough M J, Ross B C, Reade P C. Candida albicans: a review of its history, taxonomy, epidemiology, virulence attributes, and methods of strain differentiation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;25:136–144. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(96)80060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikawa K, Akamatsu H, Maekawa N, Nishina K, Obara H, Niwa Y. Inhibitory effect of prostaglandin E1 on human neutrophil function. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1994;51:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(94)90193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Natarajan U, Randhawa N, Brummer E, Stevens D A. Effect of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor on candidacidal activity of neutrophils, monocytes or monocyte-derived macrophages and synergy with fluconazole. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:359–363. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-4-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niwa Y, Ozaki Y, Kanoh T, Akamatsu H, Kurisaka M. Role of cytokines, tyrosine kinase and protein kinase C in production of superoxide and induction of scavenging enzymes in human leukocytes. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;79:303–313. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pereira H A, Hosking C S. The role of complement and antibody in opsonization and intracellular killing of Candida albicans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1984;57:307–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prasad R, De Wergifosse P, Goffeau A, Balzi E. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel gene of Candida albicans, CDR1, conferring multiple resistance to drugs and antifungals. Curr Genet. 1995;27:320–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00352101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prenner E J, Lewis R N, McElhaney R N. The interaction of the antimicrobial peptide gramicidin S with lipid bilayer model and biological membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1462:201–221. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reiss E, Tanaka Y, Bruker G, Chazalet V, Coleman D, Debeaupuis J P, Hanazawa R, Latge J P, Lortholary J, Makimura K, Morrison C J, Murayama S Y, Naoe S, Paris S, Sarfati J, Shibuya K, Sullivan D, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. Molecular diagnosis and epidemiology of fungal infections. Med Mycol. 1998;36:249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riancho J A, Zarrabeitia M T, Fernandez-Luna J L, Gonzalez-Macias J. Mechanisms controlling nitric oxide synthesis in osteoblasts. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1995;107:87–92. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)03428-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez R J, Acosta D., Jr Comparison of ketoconazole- and fluconazole-induced hepatotoxicity in a primary culture system of rat hepatocytes. Toxicology. 1995;96:83–92. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(94)02911-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samaranayake L P. Oral mycosis in HIV infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:171–180. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90191-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shiraishi A, Arai T. Antifungal activity of transferrin. Sabouraudia. 1979;17:79–83. doi: 10.1080/00362177985380101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soukka T, Tenovuo J, Lenander-Lumikari M. Fungicidal effect of human lactoferrin against Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;69:223–228. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90650-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanizaki Y, Kitani H, Okazaki M, Mifune T, Mistunobu F. Humoral and cellular immunity to Candida albicans in patients with bronchial asthma. Intern Med. 1992;31:766–769. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.31.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsuchimori N, Sharkey L L, Fonzi W A, French S W, Edwards J E, Jr, Filler S G. Reduced virulence of HWP1-deficient mutants of Candida albicans and their interactions with host cells. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1997–2002. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.1997-2002.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tyagi S R, Winton E F, Lambeth J D. Granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor primes human neutrophils for increased diacylglycerol generation in response to chemoattractant. FEBS Lett. 1989;257:188–190. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81817-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ueta E, Tanida T, Doi S, Osaki T. Regulation of Candida albicans growth and adhesion by saliva. J Lab Clin Med. 2000;136:66–73. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2000.107304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ueta E, Tanida T, Osaki T. A novel bovine lactoferrin peptide, FKCRRWQWRM, suppresses Candida cell growth and activates neutrophils. J Pept Res. 2001;57:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2001.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ueta, E., T. Tanida, K. Yoneda, T. Yamamoto, and T. Osaki. Increase of Candida cell virulence by anticancer drugs and irradiation. Oral Microbiol. Immunol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Umazume M, Ueta E, Osaki T. Reduced inhibition of Candida albicans adhesion by saliva from patients receiving oral cancer therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:432–439. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.432-439.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vazquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Balish E. Peroxynitrite contributes to the candidacidal activity of nitric oxide-producing macrophages. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3127–3133. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3127-3133.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vidotto V, Polonelli L, Conti S, Ponton J, Vieta I. Factors influencing the expression in vitro of Candida albicans stress mannoproteins reactive with salivary secretory IgA. Mycopathologia. 1998;141:1–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1006820119823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wada T, Aiba Y, Shimizu K, Takagi A, Niwa T, Koga Y. The therapeutic effect of bovine lactoferrin in the host infected with Helicobacter pylori. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:238–243. doi: 10.1080/00365529950173627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wakabayashi H, Abe S, Okutomi T, Tansho S, Kawase K, Yamaguchi H. Cooperative anti-Candida effect of lactoferrin or its peptides in combination with azole antifungal agents. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:821–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu Y Y, Samaranayake Y H, Samaranayake L P, Nikawa H. In vitro susceptibility of Candida species to lactoferrin. Med Mycol. 1999;37:35–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-280x.1999.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yeh C K, Dodds M W, Zuo P, Johnson D A. A population-based study of salivary lysozyme concentrations and candidal counts. Arch Oral Biol. 1997;42:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(96)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]