Abstract

Herein we report the discovery of a novel biaryl amide series as selective inhibitors of hematopoietic protein kinase 1 (HPK1). Structure–activity relationship development, aided by molecular modeling, identified indazole 5b as a core for further exploration because of its outstanding enzymatic and cellular potency coupled with encouraging kinome selectivity. Late-stage manipulation of the right-hand aryl and amine moieties surmounted issues of selectivity over TRKA, MAP4K2, and STK4 as well as generating compounds with balanced in vitro ADME profiles and promising pharmacokinetics.

Keywords: HPK1, tyrosine kinase inhibition, selectivity profile, MAP4K2, STK4

Immune checkpoint inhibition has emerged as a highly effective strategy in cancer treatment, with durable responses observed across a variety of tumor types.1 Nevertheless, a significant proportion of patients do not respond effectively to immune checkpoint blockade or develop resistance after an initial response. Thus, additional targets that can modulate the immune response synergistically with checkpoint inhibitors are of great interest.2 One such target is hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 (HPK1/MAP4K1),3−5 a serine/threonine kinase of the Ste20 family that is involved in the downregulation of T-cell and B-cell antigen receptor signaling.6 HPK1 acts through phosphorylation of SLP76 and has an immunosuppressive function across a variety of cell types, including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as dendritic cells.7,8 HPK1 knockout mice showed increased T-cell activation, improved antitumor immunity, and increased propensity for autoimmune disease, all suggesting a critical role of HPK1 in immune modulation.6 Recent studies with single-point kinase active-site mutants have shown that the promising results with knockout mice can be recapitulated by inhibiting kinase activity,9−11 suggesting that a small-molecule ATP-competitive approach to HPK1 inhibition could lead to effective immune activation. Intrigued by the possibilities of HPK1 blockade, we and others12−17 initiated a program to develop small-molecule ATP-competitive inhibitors of HPK1.

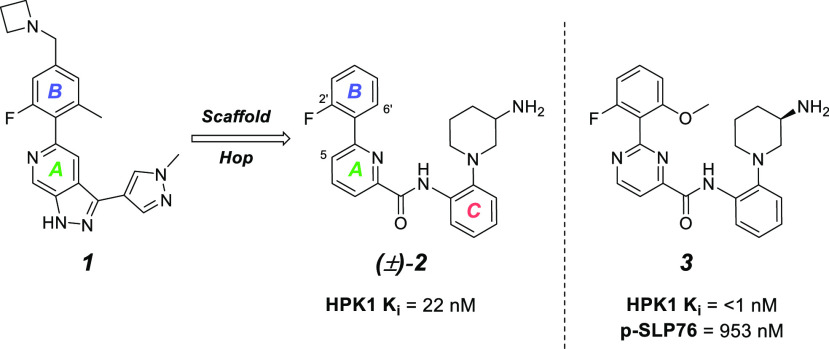

The preceding paper described the identification of a series of 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-c]pyridines, culminating in the discovery of compound 1 (Figure 1). In an effort to identify additional leads from a structurally distinct scaffold, we reanalyzed the screen of our in-house compound collection in light of the structure–activity relationship (SAR) uncovered in the identification of 1. In particular, compound (±)-2 caught our attention, as it had satisfactory preliminary binding potency in a homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF)-based binding assay but no clear traditional hinge binder. When tested in an in-house kinase panel, (±)-2 had promising selectivity. Furthermore, when tested in an HTRF-based cellular assay measuring the phosphorylation of SLP76 in Jurkat cells, (±)-2 displayed micromolar potency (p-SLP76 IC50 = 4.6 μM). Based on these promising results, (±)-2 was selected for follow-up studies.

Figure 1.

Scaffold hop from 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-c]pyridine to a picolinamide-based core.

To initiate our efforts, we modeled 2 in the active site of the HPK1 protein. Our modeling was based on the hypothesis that the carbonyl of the amide binds to the hinge, as exemplified in a recent crystal structure of an IRAK1 inhibitor (PDB entry 6BFN(18)). Docking of (R)-2 in HPK1 (PDB entry 6CQF(19)) using a similar binding mode is shown in Figure 2a. The R isomer is shown based on observed data (vide infra), but initial modeling did not suggest a clear preference for one isomer. In this model, 2 displays a monodentate interaction with the hinge region of HPK1, in which the amide carbonyl forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone N-H of Cys-94. The o-fluorophenyl group extends into a lipophilic pocket under the P-loop. Finally, the primary amine forms a hydrogen bond with Asp-101. An overlay of (R)-2 and our lead 1 (Figure 2b) suggests that the fluorophenyl and fluoromethylphenyl rings overlap significantly, whereas the interaction with Asp-101 is unique, representing a promising area for further exploration.

Figure 2.

(A) Docking model of compound 2 in complex with HPK1. The R isomer is shown. Color coding: green, P-loop; yellow, hinge; red, catalytic loop. (B) Overlay of compounds 1 (magenta) and (R)-2 (cyan).

The previously disclosed SAR in the P-loop region of 1 revealed that enzyme potency was extremely sensitive to the dihedral angle between rings A and B (see Figure 1 for labeling). While the exact substitution pattern for maximum potency was empirical, substantial improvements could be realized. Specifically, 2′,6′-disubstitution of ring B frequently led to improved potency and general kinase selectivity. Furthermore, a recently disclosed HPK1 crystal structure (PDB entry 7L25(12)) suggested that the pyridine nitrogen in the pyrazolopyridine core in 1 formed a water-mediated hydrogen bond with Asp-155 of HPK1. By applying these findings to our new core, we discovered that pyrimidine 3 possessing a fluoromethoxyphenyl substituent as ring A and pyrimidine as ring B (Figure 1, right) exhibited the greatest potency gain in this series. Compound 3 showed greatly improved (>20-fold) enzyme potency in the primary binding assay relative to our initial racemic hit (±)-2 and displayed ∼1 μM potency in the cellular assay.

We next examined the interaction with Asp-101 in an attempt to further improve the cellular and enzymatic potency. A preliminary SAR study evaluated a focused set of replacements for the aminopiperidine as well as a set of small substituents around ring C. Gratifyingly, compound 4 adorned with 3-aminopyrrolidine and fluoro substitution maintained enzyme potency while greatly improving selectivity in our in-house panel, albeit with significant activity remaining for TRKA (Table 1, entry 1). Next, a number of ring C alternatives were evaluated (Table 1). The key finding of SAR studies in this binding pocket was the identification of 1H-indazole 5a (entry 2), which improved the cellular potency without any detriment to the kinase selectivity. Addition of fluoro substitution further boosted the enzyme and cellular potency (compound 5b, entry 3). The corresponding 2H-indazole isomer (entry 4) was also potent and offered similar selectivity but exhibited reduced chemical stability. Additional heterocycles (entries 5–7) showed improved potency but suffered from decreased kinase selectivity (see Table S1 for full information). In light of its balanced potency, chemical stability, and kinase selectivity, we selected indazole 5b for further study.

Table 1. SAR Study of Replacements for Ring C.

Measured at [ATP] = 1 mM.

Examination of compound 5b in a broader 58-member kinase panel at 1 mM ATP (see the Supporting Information) showed a promising off-target profile. Besides TRKA, 5b showed <1 μM potency against only four additional kinases (LCK, 846 nM; PKCD, 391 nM; MAP4K2, 21 nM; STK4, 30 nM). We were particularly concerned with STK4, which can counter the effects of HPK1 in vivo.20,21 We were also cognizant of the need for selectivity within the MAP4K family, as many of its members are also involved in the immune response and also have the potential to counter effects of HPK1 inhibition.22 We thus set out to further delineate the structure–selectivity profile of the indazole scaffold. We chose to use TRKA as a surrogate for general kinome selectivity and MAP4K2 as a surrogate for MAP4K family selectivity. These two kinases, along with STK4, became a standard counterscreen for promising compounds.

The success of the 3-aminopyrrolidine at modulating the off-target profile prompted us to examine in-depth the amine substitution at R2 (Table 2). 4-Aminopiperidine and unsubstituted piperazine (entries 1 and 2) did not provide improvements in the TRKA selectivity; however, we found that the judicious placement of a methyl group on the piperazine could greatly improve the selectivity. The (R)-methyl at the 2-position (entry 3) increased the selectivity against TRKA 10-fold relative to 5b (entry 3, Table 1). Reasoning that a conformational effect was at play, we next assayed a number of rigid bicyclic frameworks, of which diazobicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (compound 6d, entry 4) led to a noteworthy improvement against TRKA (2 μM), STK4 (178 nM), and MAP4K2 (84 nM). We observed a similar result with pyrrolidine substitution. Introduction of methyl at the 5-position (entry 6) led to a >10-fold reduction of TRKA potency relative to 5b. Hydroxymethyl substitution (compound 6g, entry 7) proved to be remarkable for kinase selectivity, with >10 μM potency against TRKA as well as selectivity over MAP4K2 (530 nM) and STK4 (201 nM). The observed improvement was a harmonious effect between the two substituents, as removing either the hydroxymethyl (Table 1, entry 3) or amine (Table 2, entry 8) led to compounds with greatly diminished selectivity. When the hydroxyl group was removed to provide methyl-substituted compound 6f, the selectivity was similarly diminished. Furthermore, the particular orientation of substituents was key, as neither constitutional nor stereochemical isomers of 6g achieved similar levels of potency or selectivity (entries 10–12), with the exception of 6i (entry 9), in which the amine and hydroxy functionalities are transposed. The combination of these results suggests the possibility that an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the cis-disposed amine and hydroxyl substituents enforces a conformation that is desirable for selectivity. Both compounds 6d and 6g were tested in an in house 58-member kinase panel and showed remarkable improvements in selectivity relative to 5b, with only STK4 and MAP4K2 showing activity <1 μM (see the Supporting Information).

Table 2. Amine-Based R2 Substituents and Effects on Enzymatic Potency and TRKA Selectivity.

Measured at [ATP] = 1 mM.

Compounds 6d, 6g, and 6i represented a new standard for selectivity against off-target kinases in the series and indeed the project, but they also showcased the difficulties of obtaining a balanced overall profile for indazole-containing compounds. In particular, ADME properties proved especially difficult to balance. Compound 6i suffered from extensive inhibition of CYP 2D6 (IC50 = 110 nM) as well as time-dependent inhibition of CYP 3A4. Compound 6d exhibited acceptable permeability (Caco-2 permeability = 4.8 × 10–6 cm/s) and moderate turnover in human liver microsomes (0.7 L h–1 kg–1) but suffered from reduced cellular potency in the presence of human whole blood (hWB) (p-SLP76 hWB IC50 = 1.2 μM), poor solubility (17 μg/mL, SGF buffer), and moderate inhibition of the hERG channel (74% at 5 μM). Compound 6g, on the other hand, possessed improved hWB potency (IC50 = 400 nM), good solubility (350 μg/mL, SGF buffer) and no inhibition of the hERG channel but suffered from high turnover in human liver microsomes (>1.1 L h–1 kg–1). Extensive additional SAR studies of the indazole series failed to lead to a suitable compound balanced in potency, selectivity, and ADME profile. We were therefore prompted to re-evaluate our earlier SAR in light of the progress achieved in the indazole series. Specifically, we were drawn back to compound 4 (Table 1, Entry 1). Having now established a number of approaches to modulate the TRKA selectivity and improve the potency, we decided to revisit the structurally distinct phenyl analogues.

We initially ascertained that the SAR trends discovered on the indazoles would transfer to the phenyl series. Installing the most promising amine substituents provided compounds 7a and 7b (Table 3, entries 1 and 2). Both maintained enzymatic potency against HPK1 comparable to that of their indazole congeners while effectively reducing the TRKA potency. We next performed an extensive SAR study of the right-hand-side phenyl ring, which is summarized in Table 3 as a series of matched pairs. First, substitution at R4 was especially beneficial to the potency, particularly with heteroaromatic substitution (entry 4). Furthermore, while unsubstituted biaryl systems potently inhibited TRKA, ortho substitution at the R4 aryl ring successfully reversed this trend (entry 4 vs 5). Finally, the effect of fluoro substitution at R5 was more complex. Analogous to the indazole series, removal of fluorine with R4 = H led to a slightly improved hERG inhibition profile at the expense of enzyme potency (entry 1 vs 3). However, for compounds with R4 ≠ H, the benefits for hERG inhibition remained, but the potency was improved (entry 5 vs 6). Therefore, we moved forward without fluorine substitution.

Table 3. Right-Hand-Side Optimization of Potency, Selectivity, and ADME Properties.

Measured at [ATP] = 1 mM.

Measured at 30 μM compound concentration (see the SI for more details). NR = not reported.

The diazobicyclo[2.2.1]heptane fragment improved the potency and selectivity for TRKA; however, similar gains against STK4 and MAP4K2 remained recalcitrant. In addition, the hWB potency remained poor, and hERG channel inhibition was frequently observed. Gratifyingly, the more polar 3-amino-5-hydroxymethylpyrrolidine (Table 3, entry 7) greatly improved the hWB potency and improved the hERG inhibition. Replacing 2-methylpyridyl with the more polar 4-cyanopyridyl at R4 further improved HPK1 inhibition in hWB while providing a balanced selectivity profile against STK4 and MAP4K2 (entry 8). Other heterocycles proved to be even more selective. Moving the pyridine nitrogen in 7h to the 2-position (entry 9) further increased the selectivity for both MAP4K2 and STK4, while some 2,5-disubstituted pyrazoles (e.g., 7j; entry 10) pushed the activity of both kinases to >1 μM. Unfortunately, 7j and similar pyrazoles generally suffered from low permeability (Caco-2 permeability < 0.3 × 10–6 cm/s). Investigation of pyrazole regioisomers identified compound 7k, which possessed improved permeability (Caco-2 permeability = 1.6 × 10–6 cm/s) at the expense of some kinase selectivity.

We next examined the pharmacokinetics (PK) of 7b, 7h, 7i, and 7k (Table 4). In rat, after a 1.0 mg/kg iv dose, compounds 7h, 7i, and 7k had clearance in excess of hepatic blood flow. After a 3.0 mg/kg oral dose, Cmax of 170–270 nM and AUC of 800–1100 nM*h were observed. Meanwhile, 7b had low clearance, moderate volume of distribution, and an AUC in excess of 8 μM*h. In mouse, when dosed at 30 mg/kg bid, 7b covered mouse WB IC50 for 16 h, while a 75 mg/kg bid dose of 7h maintained IC50 coverage for ∼6 h. Finally, to further examine the kinase selectivity of exemplary compounds produced in this campaign, we tested 7b and 7h in a broader 376-member kinase panel from Reaction Biology Corporation. Both showed remarkable selectivity, and in particular, 7h showed only one other kinase inhibited >50% at a concentration of 20 nM (MAP4K3, IC50 = 32 nM at [ATP] = 1 mM)23 and only six kinases at <1 μM in a 1 mM ATP assay. Compound 7b inhibited three kinases >50% at 100 nM concentration and three additional kinases <1 μM at 1 mM ATP (see the Supporting Information for full details).

Table 4. Rodent Pharmacokinetics for Lead Compounds.

| iva |

pob |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | Cl (L h–1 kg–1) | hepatic ER (%) | Vss (L/kg) | t1/2 (h) | Cmax (nM) | AUC (nM*h) | F (%) |

| 7b | 0.56 | 20 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 1930 | 8600 | 47 |

| 7h | 4.16 | 130 | 11.0 | 2.5 | 202 | 792 | NR |

| 7i | 5.2 | 160 | 9.3 | 1.7 | 277 | 1110 | NR |

| 7k | 5.85 | 180 | 12.0 | 1.7 | 170 | 800 | NR |

1 mg/kg dose.

3 mg/kg dose. NR = not reported.

In conclusion, we have presented a medicinal chemistry campaign aimed at highly potent and selective HPK1 inhibitors. Molecular modeling and overlays with a previously reported series allowed us to rapidly improve the HPK1 potency and identify indazole 5b as a promising initial lead. We also identified a new selectivity pocket centered on an interaction with Asp-101 of HPK1. Focused SAR in this region identified a number of structural motifs with excellent kinome selectivity. Applying the lessons learned in this region to a simplified phenyl scaffold achieved a balanced ADME profile and provided excellent hWB potency (e.g., 7h). We discovered that aryl substitution at the R4 position of the phenyl scaffold could further bolster the selectivity to provide compounds with all desired off-targets showing >1 μM potency (e.g., 7k). We also identified R4-truncated aryls (e.g., 7b), which possess excellent rodent PK. Coupled with the preceding publication, we have identified a structurally and pharmacologically varied set of compounds to investigate HPK1 biology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kamna Katiyar, Hong Chang, Ronald Klabe, Qian Zhang, Robert Landman, Stephanie Wezalis, Peidi Hu, Ruth Young Sciame, Yaoyu Chen, Yingnan Chen, Hui Wang, Michelle Pusey, Zhenhai Gao, and Jonathan Rios-Doria for their assistance in performing biological and ADME assays and PK assessments of the compounds described herein. We also thank Scott Leonard, James Hall, and Laurine Gayla for NMR support and Yingrui Dai, Karl Blom, Ronald Magboo, Jim Doughty, and Min Li for analytical support.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- TRKA

tropomyosin receptor kinase A

- LCK

lymphocyte-specific protein kinase

- PKCD

protein kinase C delta type

- MAP4K2

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 2

- STK4

serine/threonine protein kinase 4

- ADME

absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion

- hERG

human ether a-go-go

- iv

intravenous

- po

per os

- AUC

area under the curve

- Cmax

maximum concentration

- F

oral bioavailability

- t1/2

half-life

- Vss

volume of distribution at steady state

- Cl

systemic clearance

- CYP

cytochrome P450

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00241.

Experimental procedures for in vitro and in vivo studies; synthetic procedures and characterization of all compounds; detailed potency and ADME data; and kinase profiling for compounds 5b, 6d, 6g, 6j, 7b, and 7h (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): All of the authors are current or former employees of Incyte Corporation.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ribas A.; Wolchok J. D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 2018, 359 (6382), 1350–1355. 10.1126/science.aar4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D. S.; Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity 2013, 39 (1), 1–10. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M. C.; Qiu W. R.; Wang X.; Meyer C. F.; Tan T. H. Human HPK1, a novel human hematopoietic progenitor kinase that activates the JNK/SAPK kinase cascade. Genes Dev. 1996, 10 (18), 2251–64. 10.1101/gad.10.18.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawasdikosol S.; Zha R.; Yang B.; Burakoff S. HPK1 as a novel target for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol. Res. 2012, 54 (1–3), 262–5. 10.1007/s12026-012-8319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer F.; Tibbles L. A.; Anafi M.; Janssen A.; Zanke B. W.; Lassam N.; Pawson T.; Woodgett J. R.; Iscove N. N. HPK1, a hematopoietic protein kinase activating the SAPK/JNK pathway. EMBO J. 1996, 15 (24), 7013–7025. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb01093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shui J. W.; Boomer J. S.; Han J.; Xu J.; Dement G. A.; Zhou G.; Tan T. H. Hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 negatively regulates T cell receptor signaling and T cell-mediated immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8 (1), 84–91. 10.1038/ni1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Li J. P.; Chiu L. L.; Lan J. L.; Chen D. Y.; Boomer J.; Tan T. H. Attenuation of T cell receptor signaling by serine phosphorylation-mediated lysine 30 ubiquitination of SLP-76 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287 (41), 34091–100. 10.1074/jbc.M112.371062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzabin S.; Bhardwaj N.; Kiefer F.; Sawasdikosol S.; Burakoff S. Hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 is a negative regulator of dendritic cell activation. J. Immunol. 2009, 182 (10), 6187–94. 10.4049/jimmunol.0802631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si J.; Shi X.; Sun S.; Zou B.; Li Y.; An D.; Lin X.; Gao Y.; Long F.; Pang B.; Liu X.; Liu T.; Chi W.; Chen L.; Dimitrov D. S.; Sun Y.; Du X.; Yin W.; Gao G.; Min J.; Wei L.; Liao X. Hematopoietic Progenitor Kinase1 (HPK1) Mediates T Cell Dysfunction and Is a Druggable Target for T Cell-Based Immunotherapies. Cancer Cell 2020, 38 (4), 551–566. 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez S.; Qing J.; Thibodeau R. H.; Du X.; Park S.; Lee H. M.; Xu M.; Oh S.; Navarro A.; Roose-Girma M.; Newman R. J.; Warming S.; Nannini M.; Sampath D.; Kim J. M.; Grogan J. L.; Mellman I. The Kinase Activity of Hematopoietic Progenitor Kinase 1 Is Essential for the Regulation of T Cell Function. Cell Rep. 2018, 25 (1), 80–94. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Curtin J.; You D.; Hillerman S.; Li-Wang B.; Eraslan R.; Xie J.; Swanson J.; Ho C. P.; Oppenheimer S.; Warrack B. M.; McNaney C. A.; Nelson D. M.; Blum J.; Kim T.; Fereshteh M.; Reily M.; Shipkova P.; Murtaza A.; Sanjuan M.; Hunt J. T.; Salter-Cid L. Critical role of kinase activity of hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 in anti-tumor immune surveillance. PLoS One 2019, 14 (3), e0212670 10.1371/journal.pone.0212670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu E. C.; Methot J. L.; Fradera X.; Lesburg C. A.; Lacey B. M.; Siliphaivanh P.; Liu P.; Smith D. M.; Xu Z.; Piesvaux J. A.; Kawamura S.; Xu H.; Miller J. R.; Bittinger M.; Pasternak A. Identification of Potent Reverse Indazole Inhibitors for HPK1. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12 (3), 459–466. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vara B. A.; Levi S. M.; Achab A.; Candito D. A.; Fradera X.; Lesburg C. A.; Kawamura S.; Lacey B. M.; Lim J.; Methot J. L.; Xu Z.; Xu H.; Smith D. M.; Piesvaux J. A.; Miller J. R.; Bittinger M.; Ranganath S. H.; Bennett D. J.; DiMauro E. F.; Pasternak A. Discovery of Diaminopyrimidine Carboxamide HPK1 Inhibitors as Preclinical Immunotherapy Tool Compounds. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12 (4), 653–661. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan A. P.; Kumi G. K.; Allard C. W.; Araujo E. V.; Johnson W. L.; Zimmermann K.; Pearce B. C.; Sheriff S.; Futran A.; Li X.; Locke G. A.; You D.; Morrison J.; Parrish K. E.; Stromko C.; Murtaza A.; Liu J.; Johnson B. M.; Vite G. D.; Wittman M. D. Discovery of Orally Active Isofuranones as Potent, Selective Inhibitors of Hematopoetic Progenitor Kinase 1. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12 (3), 443–450. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan B. K.; Seward E.; Lainchbury M.; Brewer T. F.; An L.; Blench T.; Cartwright M. W.; Chan G. K. Y.; Choo E. F.; Drummond J.; Elliott R. L.; Gancia E.; Gazzard L.; Hu B.; Jones G. E.; Luo X.; Madin A.; Malhotra S.; Moffat J. G.; Pang J.; Salphati L.; Sneeringer C. J.; Stivala C. E.; Wei B.; Wang W.; Wu P.; Heffron T. P. Discovery of Spiro-azaindoline Inhibitors of Hematopoietic Progenitor Kinase 1 (HPK1). ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13 (1), 84–91. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q.; Chen N.; Tian X.; Zhou Y.; You Q.; Xu X. Hematopoietic Progenitor Kinase 1 in Tumor Immunology: A Medicinal Chemistry Perspective. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65 (12), 8065–8090. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchow S.; Korepanova A.; Panchal S. C.; McClure R. A.; Longenecker K. L.; Qiu W.; Zhao H.; Cheng M.; Guo J.; Klinge K. L.; Trusk P.; Pratt S. D.; Li T.; Kurnick M. D.; Duan L.; Shoemaker A. R.; Gopalakrishnan S. M.; Warder S. E.; Shotwell J. B.; Lai A.; Sun C.; Osuma A. T.; Pappano W. N. The HPK1 Inhibitor A-745 Verifies the Potential of Modulating T Cell Kinase Signaling for Immunotherapy. ACS Chem. Biol. 2022, 17 (3), 556–566. 10.1021/acschembio.1c00819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Qiao Q.; Ferrao R.; Shen C.; Hatcher J. M.; Buhrlage S. J.; Gray N. S.; Wu H. Crystal structure of human IRAK1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114 (51), 13507–13512. 10.1073/pnas.1714386114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P.; Sneeringer C. J.; Pitts K. E.; Day E. S.; Chan B. K.; Wei B.; Lehoux I.; Mortara K.; Li H.; Wu J.; Franke Y.; Moffat J. G.; Grogan J. L.; Heffron T. P.; Wang W. Hematopoietic Progenitor Kinase-1 Structure in a Domain-Swapped Dimer. Structure 2019, 27 (1), 125–133. 10.1016/j.str.2018.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salojin K. V.; Hamman B. D.; Chang W. C.; Jhaver K. G.; Al-Shami A.; Crisostomo J.; Wilkins C.; Digeorge-Foushee A. M.; Allen J.; Patel N.; Gopinathan S.; Zhou J.; Nouraldeen A.; Jessop T. C.; Bagdanoff J. T.; Augeri D. J.; Read R.; Vogel P.; Swaffield J.; Wilson A.; Platt K. A.; Carson K. G.; Main A.; Zambrowicz B. P.; Oravecz T. Genetic deletion of Mst1 alters T cell function and protects against autoimmunity. PLoS One 2014, 9 (5), e98151 10.1371/journal.pone.0098151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahpour H.; Appaswamy G.; Kotlarz D.; Diestelhorst J.; Beier R.; Schaffer A. A.; Gertz E. M.; Schambach A.; Kreipe H. H.; Pfeifer D.; Engelhardt K. R.; Rezaei N.; Grimbacher B.; Lohrmann S.; Sherkat R.; Klein C. The phenotype of human STK4 deficiency. Blood 2012, 119 (15), 3450–7. 10.1182/blood-2011-09-378158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang H.-C.; Wang X.; Tan T.-H. MAP4K Family Kinases in Immunity and Inflammation. Adv. Immunol. 2016, 129, 277–314. 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccone D.; Rocnik J.; Lazari V.; Linney I.; Briggs M.; Collis A.; Loh C.; Ashwell M.; Montana J.; Tummino P.; Kaila N. Abstract 942: HPK1, hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1, is a promising therapeutic target for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 942–942. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2020-942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.