Abstract

Silicone wristbands act as passive environmental samplers capable of detecting and measuring concentrations of a variety of chemicals. They offer a noninvasive method to collect complex exposure data in large-scale epidemiological studies. We evaluated the inter-method reliability of silicone wristbands and urinary biomarkers in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study. A subset of study participants (n=96) provided a urine sample and wore a silicone wristband for 7 days at approximately 12 gestational weeks. Women were instructed to wear the wristbands during all their normal activities. Concentrations of urinary compounds and metabolites in the urine and parent compounds in wristbands were compared. High detection rates were observed for triphenyl phosphate (76.0%) and benzophenone (78.1%) in wristbands, although the distribution of corresponding urinary concentrations of chemicals did not differ according to whether chemicals were detected or not detected wristbands. While detected among only 8.3% of wristbands, median urinary triclosan concentrations were higher among those with detected wristbands (9.04 ng/mL) than without (0.16 ng/mL). For most chemicals slight to fair agreement was observed across exposure assessment methods, potentially due to low rates of detection in the wristbands for chemicals where observed urinary concentrations were relatively low as compared to background concentrations in the general population. Our findings support the growing body of research in support of deploying silicone wristbands as an important exposure assessment tool.

Keywords: silicone wristbands, passive monitors, pregnancy, personal exposure, biomarkers, exposome

1. Introduction

The exposome refers to the total exposure to exogenous and endogenous factors from conception to death, and is critical in understanding the development of diseases (Rappaport, 2011; Rappaport and Smith, 2010; Vineis et al., 2013; Wild, 2005). One common challenge in conducting large-scale epidemiological studies is assessing environmental exposures with a method that is cost-efficient, easy to deploy, and provides meaningful information. Recently, silicone “exposome wristbands” have been developed to act as passive environmental samplers, offering a noninvasive and cost-effective method for measuring human exposures to a wide range of organic compounds in consumer products and industrial chemicals, such as flame retardants, plasticizers, and pesticides (Aerts et al., 2018; Anderson et al., 2017; Bergmann et al., 2017; Dixon et al., 2019; Doherty et al., 2021; Donald et al., 2016; Kile et al., 2016; O’Connell et al., 2014). Several studies have evaluated the silicone wristband for its technical use including temperature, storage, transport, and analytic reliability (Anderson et al., 2017; O’Connell et al., 2014). However, questions remain as to optimal applications for public health research and the specific chemicals or classes of chemicals wristbands are best suited to detect and quantify. Chemicals and their metabolites measured in urine samples are widely used to quantify environmental exposures (Butt et al., 2014; Cooper et al., 2011; Gong et al., 2015), and many epidemiologic studies use urinary biomarkers of exposure to assess environmental contaminants, even with known variability and challenges in sample collection. In recent years, paired silicone wristbands and urine samples have been analyzed to compare and validate the chemicals and metabolites detected across methods (Dixon et al., 2018; Gibson et al., 2019; Hammel et al., 2020; Hammel et al., 2016; Hammel et al., 2018; Levasseur et al., 2020; Quintana et al., 2019; Quintana et al., 2020). Previous studies conducted in urban settings demonstrate good reliability for organophosphate esters (OPEs) (Gibson et al., 2019), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)(Dixon et al., 2018), and chemicals from secondhand smoke including nicotine, cotinine, and tobacco-specific nitrosamines detected in both wristbands and urine samples (Quintana et al., 2019; Quintana et al., 2020). These studies used urinary chemicals or metabolites as the gold standards to compare the chemicals detected in the wristbands to evaluate the reliability of the method.

In a previous study we analyzed silicone wristbands worn by 255 women in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study (NHBCS) for one week. Wristbands reflected a median of 23 chemicals (range: 12, 37) per woman; specifically chemicals from commerce and personal care products were most common, including several phthalates, synthetic scents (e.g., galaxolide, lilial), and benzophenone (Doherty et al., 2020). In the present study, we evaluated the reliability of measurements from silicone wristbands in the NHBCS and corresponding urinary biomarkers for key toxicants within a population of rural pregnant women.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study population.

Participants included a subset of women enrolled in the NHBCS, ongoing since 2009 (Gilbert-Diamond et al., 2011; Gilbert-Diamond et al., 2016). Briefly, pregnant women between 18 and 45 years old were enrolled during their prenatal care at participating study clinics. Extensive information was collected on lifestyle, diet, and demographic factors through questionnaires and prenatal medical record review. All participants provided written informed consent, and this study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College.

2.2. Assessment of Environmental Exposures with Silicone Wristbands.

Between March 2017 and December 2018, a subset of 100 women were selected for urinary environmental phenol and organophosphate flame retardant assessment. Women provided a urine sample at an in-person visit at approximately 12 gestational weeks (Gilbert-Diamond et al., 2011) and were given a silicone wristband (MyExposome, Inc., Corvallis, OR). Collection of urine at the beginning of the week of observation assumes that exposure patterns for the chemicals of interest are relatively stable over short intervals of time (i.e., 1–2 weeks), which is consistent with what is known about intraindividual variability in urine concentrations for the majority of chemicals of interest (Bastiaensen, M. et al. 2021; Braun, J. M., et al. 2013; Nassan, F. L. et al. 2019; Romano, M. E., et al. 2017; Smith, K.W. et al. 2012; Stacy, S. L. et al. 2017). Participants were instructed to wear the wristband for 7 days while performing their normal activities, including sleeping and showering. Chemicals are stable within the wristband even with handwashing and showering activities (Anderson K.A. et al. 2017; Doherty B.T. et al. 2020; O’Connell, S.G. et al. 2014). After wearing the wristbands for ~7 days, participants sealed the wristbands in polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) bags and mailed them to the NHBCS office. Studies of changes in temperature, storage and transport of the wristbands indicate that chemical concentrations are robust and stable for various conditions, including ambient temperatures (Anderson et al., 2017). Additional details of the wristband deployment have been previously published (Doherty et al., 2020).

MyExposome (Corvallis, OR) performed an analytical screen of 1,530 chemicals from the wristbands using previously described methods (Anderson et al., 2017; O’Connell et al., 2014). Samples were stored at 4°C prior to solid phase extraction (SPE) (Cleanert S C18, Agela Technologies, Torrance, CA, USA), eluted with acetonitrile and solvent exchanged to iso-octane (OA-SYS N-EVAP 111, Organomation Associates, Berlin,MA, USA). Chemicals included polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), flame retardants, pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and volatile organic chemicals (VOCs). Detailed information on the full analyte list and quantitative methods are available in prior publications(Bergmann et al., 2018) and online (http://www.myexposome.com/fullscreen). The current research focused on eight selected non-persistent endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) measured in the wristbands: bisphenol A (BPA), triclosan (TCS), benzophenone, 2,4-dichlorophenol (2,4-DCP), and four OPEs (triphenyl phosphate, triethyl phosphate, tributyl phosphate and tris(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate). These chemicals were selected because they correspond to measured urinary concentrations of the chemicals themselves (BPA, TCS, 2,4-DCP) or metabolites of OPEs. Metabolism of benzophenones are complex, and benzophenone, benzophenone-1 (BP-1), and benzophenone-3 (BP-3) were anticipated to share common exposure sources that included multiple UV-filter ingredients (Liao and Kannan, 2014; Suzuki et al., 2005).

2.3. Assessment of Environmental Exposures via Urine Samples.

Urine samples were collected in a pre-labeled screw-top, 120 mL polypropylene container, stored upright at 4°C until aliquoting within 24 hours. A handheld refractometer with automatic temperature compensation (ATAGO® PAL-10S) was used for the measurement of specific gravity (SG). Aliquoted samples were stored at −80 °C. Samples were sent on dry ice to the Children’s Health Exposure Analysis Resource laboratory at the Wadsworth Center (Albany, NY) for analysis. Urinary BPA, TCS, 2,4-DCP, BP-3, and BP-1 were measured by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (SCIEX TRIPLE QUAD 5500 coupled with SHIMADZU NEXERA LC-30AD), and urinary OPE metabolites, diphenyl phosphate (DPHP), diethyl phosphate (DEP), di-n-butyl phosphate (DNBP), bis(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate (BEHP), were measured by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (API QTRAP 4500 coupled with Agilent HPLC 1260). Detailed analytical methodology has been described elsewhere (Li et al., 2018; Rocha et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). Urinary concentrations below the limit of quantitation (LOQ) were imputed as LOQ/√2 (Hornung and Reed, 1990). Urinary concentrations were SG normalized to account for urine dilution (Duty et al., 2005). We calculated these concentrations using the following formula: Pc= P[SGref-1/SGi-1], where Pc is the SG-standardized urinary concentration (μg/L), P is the concentration of compound quantified in the urine sample (μg/L), SGref is the median SG within the study population and SGi is the measured SG in each sample.

2.4. Statistical Analysis.

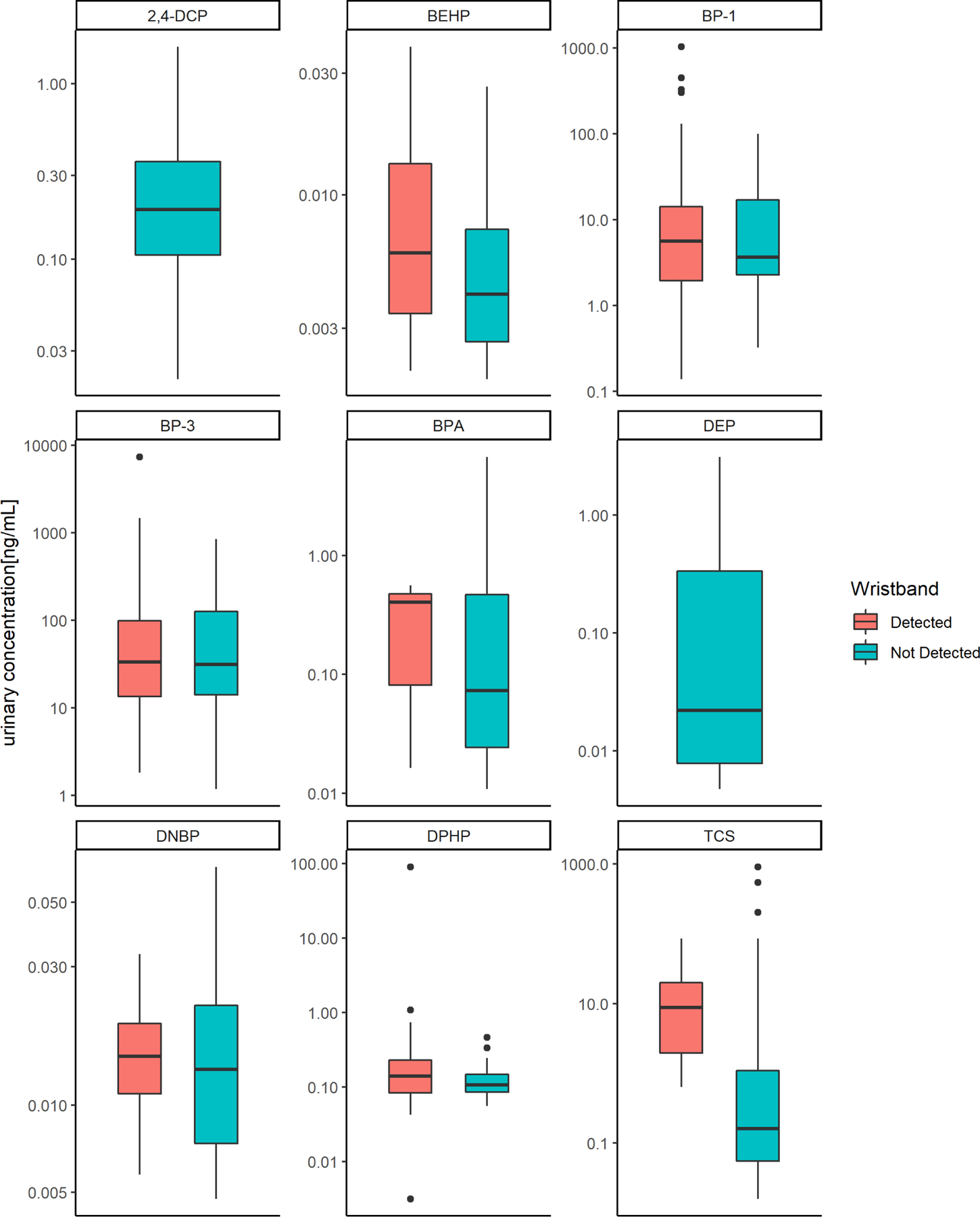

Descriptive statistics were calculated for participant characteristics including maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, race, parity, highest level of attained education, gestational age at the start of wearing the wristband, and number of days wearing the wristband. We compared the urinary chemical concentrations in the cohort to data from women in the U.S. general population using survey weighted data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) cycle closest to the study period (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). We examined the distribution of chemical concentrations in the wristbands and concentrations of urinary compounds and metabolites and calculated the median, 25th and 75th percentile. We visually compared the distribution of concentrations of relevant urinary compounds in the group with compounds detected in the wristband versus not detected using box and whisker plots and conducted non-parametric Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests (Mann Whitney U tests) to compare the two groups. For chemicals frequently detected in the wristbands (≥70%) we calculated Spearman rank correlation coefficients between concentrations of chemicals in the wristband and concentrations of relevant urinary compounds or metabolites. Cohen’s kappa coefficients were calculated to compare the level of agreement between relative categorical rankings of high concentrations of wristband chemicals and corresponding urinary compounds (McHugh, 2012). For chemicals infrequently detected in the wristbands (<20%), Cohen’s kappa coefficients were calculated comparing SG-standardized urinary concentrations divided into categories ≤75th percentile (low) and >75th percentile (high) and detection status for corresponding wristband compounds. For chemicals detected in ≥70% of wristbands, it was possible to divide both wristband and urinary chemical concentrations at the 75th percentile.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Population Characteristics.

From the initial 100 participants selected, the total number of women available for analysis was 96 due to missing urine samples or insufficient urine volume for analysis (n=4). The participants were 30 years old (std=5) on average and tended to be college or post-graduate educated (67%) and non-Hispanic white (88.5%) (Table 1). Women began wearing the wristband at mean of 12 gestational weeks (std=3) and wore the wristband for the complete 7-day period (std=2) with little exception. Compared to women in the U.S. general population, the median concentrations of urinary chemicals and metabolites of interest were orders of magnitude less in the NHBCS for DPHP (NHBCS=0.129 ng/mL vs. NHANES=0.890 ng/mL), DEP (NHBCS=0.022 ng/mL vs. NHANES=2.15 ng/ml), BPA (NHBCS=0.073 ng/mL vs. NHANES=1.0 ng/mL), and TCS (NHBCS=0.209 ng/mL vs. NHANES=3.2 ng/mL), and moderately less for DNBP (NHBCS=0.013 ng/mL vs. NHANES=0.24 ng/mL) and 2,4-DCP (NHBCS=0.192 vs. NHANES=0.500 ng/mL). BP-3 concentrations were comparable in the cohort and NHANES (NHBCS=32.5 ng/mL vs. NHANES=21.2 ng/mL). Measurements in NHANES were not available for BP-1 or BEHP (Table 2). Observed differences may reflect the more favorable overall environmental quality in our study’s rural setting as compared to urban environments (Messer et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics in study of prenatal poly-substance exposome via silicone wristband and urinary biomarkers (n=96)

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Mean (std) | |

| Maternal enrollment age (years) | 30.4 (4.6) |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1 (6.7) |

| Gestational age at start of wristband (weeks) | 12.0 (3.0) |

| Number of days wearing wristband | 7.1 (1.9) |

| n (%) | |

| Parity | |

| Nulliparous | 50 (55.0) |

| 1–2 | 40 (44.0) |

| 3+ | 1 (1.0) |

| Highest Level of Education | |

| Less than college | 25 (33.4) |

| College graduate | 32 (42.6) |

| Post-graduate | 18 (24.0) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 85 (88.5) |

| Median (IQR) | |

| Urine specific gravity (12 weeks) | 1.013 (1.007–1.020) |

Missing data on maternal BMI (n=3), parity (n=5), and education (n=21)

Table 2:

Concentrations of chemicals in silicone wristbands and corresponding urinary chemicals or metabolites at 12 gestational weeks (n=96)

| Chemical in Silicone Wristband | Detected n (%) | NHBCS Median (IQR) [ng/g]a | Relevant Urinary Chemical/Metabolite | Detected n (%) | NHBCS Median (IQR) [ng/mL]b | NHANES Median [ng/mL]c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triphenyl phosphate | 73 (76.0) | 561 (273–1150) | Diphenyl phosphate | 95 (99.0) | 0.129 (0.084–0.218) | 0.890 |

| Triethyl phosphate | 0 (0.0) | - | Diethyl phosphate | 38 (39.6) | 0.022 (0.008–0.347) | 2.15 |

| Tributyl phosphate | 11 (11.5) | 191 (126–695) | Di-n-butyl phosphate | 14 (14.6) | 0.013 (0.008–0.022) | 0.240 |

| Tris(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate | 18 (18.8) | 1590 (924–4010) | Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate | 2 (2.0) | 0.004 (0.003–0.008) | N/A |

| Bisphenol A | 3 (3.1) | - | Bisphenol A | 47 (49.0) | 0.073 (0.024–0.475) | 1.00 |

| Benzophenone | 75 (78.1) | 317 (181–535) | Benzophenone-3 | 95 (99.0) | 32.54 (13.89–102.93) | 21.2 |

| Benzophenone-1 | 92 (95.8) | 5.26 (2.04–15.65) | N/A | |||

| Triclosan | 8 (8.3) | 268 (158–299) | Triclosan | 56 (58.4) | 0.209 (0.068–1.490) | 3.20 |

| 2,4-Dichlorophenol | 0 (0.0) | - | 2,4-Dichlorophenol | 90 (93.8) | 0.192 (0.106–0.360) | 0.500 |

Silicone wristband chemicals that were not detected (zero concentration) were treated as missing for calculation of median and percentiles.

Urinary chemical concentrations for NHBCS are specific-gravity standardized. Urinary concentrations below the limit of quantitation (LOQ) were imputed as LOQ/√2 and included in calculation of median and percentiles.

Urinary chemical concentrations reported from NHANES in females 2015–2016, except diethyl phosphate (2011–2012), diphenyl phosphate (2013–2014) and di-n-butyl phosphate (2013–2014) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

3.2. Identification of Chemicals in Silicone Wristbands and Urine Samples.

Triphenyl phosphate (76.0%) and benzophenone (78.1%) were frequently detected in wristbands; whereas, tributyl phosphate (11.5%), tris(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate (18.8%), BPA (3.1%) and TCS (8.3%) were infrequently detected (Table 2). Triethyl phosphate and 2,4-DCP were not detected in the wristbands. Notably, both of the frequently detected compounds in the wristband reflect parent exposures for which dermal exposure is known to be the predominate exposure route. Urinary DPHP, 2–4-DCP, BP-3 and BP-1 were detected in >90% of samples. Lower detection rates (40–60%) were observed for urinary DEP, BPA, and TCS. DNBP (15%) and BEHP (2.0%) were infrequently detected in urine (Table 2). The UV-blocker, benzophenone was frequently detected in the wristbands, as were urinary BP-3 and BP-1. Exposure to benzophenones occurs primarily from dermal contact with personal care products (Liao and Kannan, 2014), and to a lesser degree through inhalation of vapors from surface coatings or fragrances, or ingestion from foods via either a flavor ingredient or migrated from packaging printed with UV-cured ink (Liao and Kannan, 2014; National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2021a). Triphenyl phosphate was also frequently detected in wristbands, as was its urinary metabolite DPHP. Triphenyl phosphate is used as a flame retardant, plasticizer in consumer products, and as an additive to lubricating oil, hydraulic fluids, and some nail polishes (National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2021b; Young et al., 2018). Exposure to triphenyl phosphate occurs largely through dermal contact with products, but also through ingestion of contaminated food, or water or inhalation of contaminated air (Wang and Kannan, 2018; Young et al., 2018). Chemicals such as BPA that were infrequently detected in the wristband but frequently detected in urine are chemicals more likely to come primarily from ingestion and dermal exposure routes to a lesser extent (e.g., from thermal receipts) (Liao and Kannan, 2011).

3.3. Comparison of Chemical Identification Methods.

Overall, median urinary concentrations were higher among those with detectable levels in their wristband for all chemicals; triethyl phosphate and 2,4-DCP were not detected in the wristbands (Figure 1). The distributions of urinary concentrations overlapped, and the differences were not statistically significant for the majority of comparisons. However, we observed a higher median urinary TCS concentration (9.0 ng/mL; IQR: 1.8–22.4) among women with detectable wristband TCS compared to the median of urinary TCS (0.16 ng/mL; IQR: 0.05,−1.10) among those with TCS not detected in their wristbands (Wilcoxon rank sum test p-value=0.0009, Figure 1). TCS was detected in 8 of the wristbands (8.3%) and not detected in the remaining 88 wristbands, warranting some caution in the interpretation of this finding. TCS is used as an antimicrobial agent in some soaps, personal care products, and toothpastes (Rodricks et al., 2010). Dermal contact from soaps and other personal care products and ingestion (via toothpaste) are the primary routes of exposure to triclosan (Allmyr et al., 2006; Dann and Hontela, 2011). In 2016, triclosan was banned in over-the-counter handwashing soaps (FDA 2016) and in 2017 it was further banned from any over-the-counter antiseptic products (FDA, 2017). As such, the infrequent detection of triclosan in the wristbands versus frequent detection in urine samples in the NHBCS may reflect an increased importance of ingestion as an exposure route for triclosan in this contemporary population and a shift away from dermal exposure as a primary exposure route as the chemical is phased out of soaps. In a cohort from North Carolina, concentrations of environmental phenols were compared across paired hand wipes, wristbands, and spot urine samples among young children (Levasseur et al., 2020). Triclosan in dust correlated to hand wipes, wristbands, and urinary triclosan concentrations, which also suggested sources of exposure beyond dermal personal care products may be important. Median concentrations of both wristband (787 ng/g) and urinary triclosan (5.7ng/mL) observed among these children were substantially greater than the median concentrations observed in the present study (wristband=268 ng/g; urine=0.209 ng/mL).

Figure 1: Urinary chemical concentrations by detection of chemical in wristband.

The median is represented by the bold line within the box and whisker plot. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were performed to compare differences between groups by detection status: BEHP p-value=0.09, BP-1 p-value=0.89, BP-3 p-value=0.93, BPA p-value=0.77, DNBP p-value=0.61, DPHP p-value=0.29, TCS p-value=0.0009. Abbreviations: 2,4-DCP=2,4-dichlorophenol, BPA-=bisphenol A; BEHP= bis(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate, BP-1=benzophenone-1; BP-3=benzophenone-3; DNBP= di-n-butyl phosphate, DEP= diethyl phosphate, DPHP=diphenyl phosphate, TCS=triclosan

Triphenyl phosphate and benzophenone were frequently detected in the wristbands but little to moderate correlations were observed with urinary analytes in paired samples. Benzophenone in the wristband was not correlated with urinary BP-1 (rho=0.04; p=0.72) or BP-3 (rho=−0.09; p=0.45), suggesting that exposure sources may have been distinct in this population, or that urinary concentrations of BP-1 and BP-3 potentially reflect a broader range of exposure sources (e.g., sunscreen or cosmetics applied to the face, lip balm, or food sources). Concentrations of triphenyl phosphate in the wristband were moderately correlated with urinary DPHP concentrations (rho=0.29; p=0.01). In a small study of 10 adults, DPHP in spot urine was not correlated with triphenyl phosphate is wristbands (Hoffman et al., 2021). Although, DPHP is a main metabolite of triphenyl phosphate, other parent OPEs metabolize to DPHP as well (Hoffman et al., 2021; Li et al., 2019), potentially explaining our observed moderate rather than strong correlation.

Levels of agreement across categories of urinary and wristband chemical measurements generally showed little to no agreement between the two. For instance, categories of benzophenone (wristband) compared to BP-1 (urine) and to BP-3 (urine) both had Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.06 (95%CI −0.15, 0.26), agreement considered as none to slight. However, we did observe fair agreement between high concentrations of triphenyl phosphate in the wristband and diphenyl phosphate in urine (Cohen’s kappa coefficient= 0.22; 95%CI 0.01, 0.44). Although not observed in the current analysis, other studies have found some OPE measurements in wristbands to be correlated and predictive of concentrations with corresponding compounds in urine samples (Gibson et al., 2019; Hammel et al., 2020; Hammel et al., 2016).

3.4. Role of Silicone Wristbands as an Exposure Assessment Tool.

Overall, the chemicals of interest detected in the wristbands were also evident in urine samples (either as parent compounds or metabolites thereof), although the agreement across concentration in urine versus wristband varied from slight to fair across the surveyed chemicals. Our findings highlight the utility of these easy-to-deploy silicone wristbands as an exposure assessment method to screen for contaminants that may be of concern in any given population and to identify environmental exposures among study participants (Doherty et al., 2021). Urinary chemical concentrations in the NHBCS were generally lower than those observed in NHANES, which may reflect the rural location of our study, where fewer commercial products are used and overall environmental quality is more favorable than urban settings (Messer et al., 2014). A lower prevalence of these exposures may have contributed to the lack of strong agreement across exposure assessment methods, as the urinary measurements may be more precise for capturing low levels of exposure. Notably, both benzophenone and triphenyl phosphate are chemicals for which dermal contact is a particularly important exposure route (Liao and Kannan, 2014; National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2021a; Wang and Kannan, 2018; Young et al., 2018), which potentially makes these chemicals more amenable to detection using a passive monitoring device as opposed to a biospecimen measurement that more fully reflects systemic exposure (Doherty et al., 2021). Our findings demonstrate the importance of considering what is known about the importance of different potential exposure routes for a given chemicals of interest and the overall population levels of exposure when considering wristbands as an assessment tool. Despite the limitations of passive monitors, they continue to be relevant in settings where the non-invasive advantage of wristbands over traditional biospecimens may be beneficial (Doherty et al., 2021), such as when studying pediatric populations (Kile et al., 2016) or when exposure to complex mixtures is of specific interest (Dixon et al., 2019).

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors wish to thank our ECHO colleagues, the medical, nursing and program staff, as well as the children and families participating in the ECHO cohorts. We acknowledge the contribution of the following ECHO program collaborators: ECHO Coordinating Center: Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, North Carolina: Benjamin DK, Smith PB, Newby KL. We would also like to acknowledge and thank the following: Michelle Schreiner, Richard Scott, Clarisa Caballero-Ignacio, Michael Barton, Jessica Scotten, Holly Dixon, Kaci Graber, Caoilinn Haggerty, the NHBCS study team and participants.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) program, Office of The Director, National Institutes of Health (NIH), under Award Numbers U2C OD023375 (Coordinating Center), U24 OD023382 (Data Analysis Center), U24 OD023319 (PRO Core), and UH3 OD023275, NIH National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences award numbers P42 ES007373 and P01 ES022832), and NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences P20 GM104416. BTD was supported by the Training Program for Quantitative Population Sciences in Cancer via the National Cancer Institute (NCI, R25 CA134286). KAA was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS, P42 ES016465 and P30 ES030287).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

KA, an author of this research, discloses a financial interest in MyExposome, Inc., which is marketing products related to the research being reported. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by OSU in accordance with its policy on research conflicts of interest.

Declaration of interests

☒The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Kim Anderson, an author of this research, discloses a financial interest in MyExposome, Inc., which is marketing products related to the research being reported. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by OSU in accordance with its policy on research conflicts of interest.

References

- Aerts R, et al. , 2018. Silicone Wristband Passive Samplers Yield Highly Individualized Pesticide Residue Exposure Profiles. Environ Sci Technol 52, 298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allmyr M, et al. , 2006. Triclosan in plasma and milk from Swedish nursing mothers and their exposure via personal care products. Sci Total Environ 372, 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KA, et al. , 2017. Preparation and performance features of wristband samplers and considerations for chemical exposure assessment. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 27, 551–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaensen M et al. 2021. Short-term temporal variability of urinary biomarkers of organophosphate flame retardants and plasticizers. Environ Int 146, 106147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann AJ, et al. , 2017. Multi-class chemical exposure in rural Peru using silicone wristbands. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 27, 560–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann AJ, et al. , 2018. Development of quantitative screen for 1550 chemicals with GC-MS. Anal Bioanal Chem 410, 3101–3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, et al.2013. Personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 24(5), 459–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt CM, et al. , 2014. Metabolites of organophosphate flame retardants and 2-ethylhexyl tetrabromobenzoate in urine from paired mothers and toddlers. Environ Sci Technol 48, 10432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fourth Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, Updated Tables 2019 https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/pdf/FourthReport_UpdatedTables_Volume1_Jan2019-508.pdf, 2019.

- Cooper EM, et al. , 2011. Analysis of the flame retardant metabolites bis(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (BDCPP) and diphenyl phosphate (DPP) in urine using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem 401, 2123–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dann AB, Hontela A, 2011. Triclosan: environmental exposure, toxicity and mechanisms of action. J Appl Toxicol 31, 285–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon HM, et al. , 2019. Discovery of common chemical exposures across three continents using silicone wristbands. R Soc Open Sci 6, 181836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon HM, et al. , 2018. Silicone wristbands compared with traditional polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure assessment methods. Anal Bioanal Chem 410, 3059–3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty BT, et al. , 2021. Use of Exposomic Methods Incorporating Sensors in Environmental Epidemiology. Curr Environ Health Rep 8, 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty BT, et al. , 2020. Assessment of Multipollutant Exposures During Pregnancy Using Silicone Wristbands. Frontiers in Public Health 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald CE, et al. , 2016. Silicone wristbands detect individuals’ pesticide exposures in West Africa. R Soc Open Sci 3, 160433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duty SM, et al. , 2005. Personal care product use predicts urinary concentrations of some phthalate monoesters. Environ Health Perspect 113, 1530–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA, Safety and Effectiveness of Health Care Antiseptics; Topical Antimicrobial Drug Products for Over-the-Counter Human Use In: FDA, (Ed.), 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson EA, et al. , 2019. Differential exposure to organophosphate flame retardants in mother-child pairs. Chemosphere 219, 567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert-Diamond D, et al. , 2011. Rice consumption contributes to arsenic exposure in US women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 20656–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert-Diamond D, et al. , 2016. Relation between in Utero Arsenic Exposure and Birth Outcomes in a Cohort of Mothers and Their Newborns from New Hampshire. Environ Health Perspect 124, 1299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong M, et al. , 2015. Phthalate metabolites in urine samples from Beijing children and correlations with phthalate levels in their handwipes. Indoor Air 25, 572–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammel SC, et al. , 2020. Comparing the Use of Silicone Wristbands, Hand Wipes, And Dust to Evaluate Children’s Exposure to Flame Retardants and Plasticizers. Environ Sci Technol 54, 4484–4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammel SC, et al. , 2016. Measuring Personal Exposure to Organophosphate Flame Retardants Using Silicone Wristbands and Hand Wipes. Environ Sci Technol 50, 4483–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammel SC, et al. , 2018. Evaluating the Use of Silicone Wristbands To Measure Personal Exposure to Brominated Flame Retardants. Environ Sci Technol 52, 11875–11885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, et al. , 2021. Monitoring Human Exposure to Organophosphate Esters: Comparing Silicone Wristbands with Spot Urine Samples as Predictors of Internal Dose. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 8, 805–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung RW, Reed LD, 1990. Estimation of Average Concentration in the Presence of Nondetectable Values. Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 5, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kile ML, et al. , 2016. Using silicone wristbands to evaluate preschool children’s exposure to flame retardants. Environ Res 147, 365–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur JL, et al. , 2020. Young children’s exposure to phenols in the home: Associations between house dust, hand wipes, silicone wristbands, and urinary biomarkers. Environ Int 147, 106317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li AJ, et al. , 2018. Urinary concentrations of environmental phenols and their association with type 2 diabetes in a population in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Environ Res 166, 544–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, et al. , 2019. A review on organophosphate Ester (OPE) flame retardants and plasticizers in foodstuffs: Levels, distribution, human dietary exposure, and future directions. Environ Int 127, 35–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C, Kannan K, 2011. Widespread occurrence of bisphenol A in paper and paper products: implications for human exposure. Environ Sci Technol 45, 9372–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C, Kannan K, 2014. Widespread occurrence of benzophenone-type UV light filters in personal care products from China and the United States: an assessment of human exposure. Environ Sci Technol 48, 4103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh ML, 2012. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 22, 276–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer LC, et al. , 2014. Construction of an environmental quality index for public health research. Environ Health 13, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassan FL, et al. 2019. Correlation and temporal variability of urinary biomarkers of chemicals among couples: Implications for reproductive epidemiological studies. Environ Int 123, 181–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information, PubChem Compound Summary for CID 8289, Benzophenone Vol. 2020, 2021a. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information, PubChem Compound Summary for CID 8289, Triphenyl phosphate 2021b. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell SG, et al. , 2014. Silicone wristbands as personal passive samplers. Environ Sci Technol 48, 3327–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell SG et al. , 2014. Improvements in pollutant monitoring: optimizing silicone for co-deployment with polyethylene passive sampling devices. Environ Pollut 2014;193:71–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana PJE, et al. , 2019. Nicotine levels in silicone wristband samplers worn by children exposed to secondhand smoke and electronic cigarette vapor are highly correlated with child’s urinary cotinine. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 29, 733–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana PJE, et al. , 2020. Nicotine, Cotinine, and Tobacco-Specific Nitrosamines Measured in Children’s Silicone Wristbands in Relation to Secondhand Smoke and E-cigarette Vapor Exposure. Nicotine Tob Res [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport SM, 2011. Implications of the exposome for exposure science. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 21, 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport SM, Smith MT, 2010. Epidemiology. Environment and disease risks. Science 330, 460–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha BA, et al. , 2018. Advanced data mining approaches in the assessment of urinary concentrations of bisphenols, chlorophenols, parabens and benzophenones in Brazilian children and their association to DNA damage. Environ Int 116, 269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodricks JV, et al. , 2010. Triclosan: a critical review of the experimental data and development of margins of safety for consumer products. Crit Rev Toxicol 40, 422–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano ME, et al. 2017. Variability and predictors of urinary concentrations of organophosphate flame retardant metabolites among pregnant women in Rhode Island. Environ Health 16(1), 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KW, et al. 2012. Predictors and variability of urinary paraben concentrations in men and women, including before and during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect 120(11), 1538–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy SL, et al.2017. Patterns, Variability, and Predictors of Urinary Triclosan Concentrations during Pregnancy and Childhood. Environ Sci Technol 51(11), 6404–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, et al. , 2005. Estrogenic and antiandrogenic activities of 17 benzophenone derivatives used as UV stabilizers and sunscreens. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 203, 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vineis P, et al. , 2013. Advancing the application of omics-based biomarkers in environmental epidemiology. Environ Mol Mutagen 54, 461–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kannan K, 2018. Concentrations and Dietary Exposure to Organophosphate Esters in Foodstuffs from Albany, New York, United States. J Agric Food Chem 66, 13525–13532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, et al. , 2019. Metabolites of organophosphate esters in urine from the United States: Concentrations, temporal variability, and exposure assessment. Environ Int 122, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild CP, 2005. Complementing the genome with an “exposome”: the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14, 1847–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AS, et al. , 2018. Phthalate and Organophosphate Plasticizers in Nail Polish: Evaluation of Labels and Ingredients. Environ Sci Technol 52, 12841–12850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]