Abstract

Lysosomal acid ceramidase (AC) has been reported to determine multivesicular body (MVB) fate and exosome secretion in different mammalian cells including coronary arterial endothelial cells (CAECs). However, this AC-mediated regulation of exosome release from CAECs and associated underlying mechanism remain poorly understood. In the present study, we hypothesized that AC controls lysosomal Ca2+ release through TRPML1 channel to regulate exosome release in murine CAECs. To test this hypothesis, we isolated and cultured CAECs from WT/WT and endothelial cell-specific Asah1 gene (gene encoding AC) knockout mice. Using these CAECs, we first demonstrated a remarkable increase in exosome secretion and significant reduction of lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene compared to those cells from WT/WT mice. ML-SA1, a TRPML1 channel agonist, was found to enhance lysosome trafficking and increase lysosome-MVB interaction in WT/WT CAECs, but not in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. However, sphingosine, an AC-derived sphingolipid, was able to increase lysosome movement and lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene, leading to reduced exosome release from these cells. Moreover, Asah1 gene deletion was shown to substantially inhibit lysosomal Ca2+ release through suppression of TRPML1 channel activity in CAECs. Sphingosine as an AC product rescued the function of TRPML1 channel in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. These results suggest that Asah1 gene defect and associated deficiency of AC activity may inhibit TRPML1 channel activity, thereby reducing MVB degradation by lysosome and increasing exosome release from CAECs. This enhanced exosome release from CAECs may contribute to the development of coronary arterial disease under pathological conditions.

1. Introduction

Since the late 1960s, numerous studies have shown that extracellular vesicles (EVs) originate from different subcellular membrane compartments and are released into the interstitial space. After many debates about the characterization and classification of EVs, a general consensus has been recently reached to describe three distinct populations of EVs, including apoptotic bodies, microvesicles, and exosomes, and most cell types in humans can release different vesicles into the interstitial space (Crescitelli et al., 2013; Lazaro-Ibanez et al., 2014). Exosomes, the smallest EV with approximately 40–140 nm in diameter, are formed through the endocytic process and released from intracellular multivesicular bodies (MVBs) through an active process (Rajagopal & Harikumar, 2018). EVs or exosomes have been extensively studied for their biogenesis and related function in cell-to-cell communication and in the pathogenesis of different diseases including cardiovascular diseases (Boulanger, Loyer, Rautou, & Amabile, 2017; Chistiakov, Orekhov, & Bobryshev, 2015; Hessvik & Llorente, 2018; Perrotta & Aquila, 2016). There are numerous studies about endothelial cell (EC)-derived exosomes as a biomarker for endothelial function or injuries in different cardiovascular or systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus, and hyperhomocysteinemia. These circulating exosomes may also be an interesting prognostic marker to identify patients at risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (Nozaki et al., 2009; Sinning et al., 2011). Moreover, evidence is accumulating that EVs including exosomes are critical to transport, secret or release various mediators such as ET-1, PGs, microRNAs, bioactive lipids, IL-1β, and even enzymes such as NOX, cyclooxygenases, and caspase-1 from ECs (Davenport et al., 2016; Deng et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2019; Ju et al., 2014; Subra et al., 2010; Yuan, Bhat, Lohner, Zhang, & Li, 2019). However, the regulatory mechanisms of exosome release from ECs under physiological and pathological conditions remain poorly understood.

Based on findings in previous studies, lysosome function may determine the MVB fate through lysosome-dependent degradation of MVBs (Boulanger et al., 2017; Chistiakov et al., 2015; Futter, Pearse, Hewlett, & Hopkins, 1996; Hessvik & Llorente, 2018). It was shown that inhibition of lysosome function with different alkaline agents or lysosomal v-ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin A or chloroquine increased exosome secretion in different cells such as neurons, epithelial cells, and vascular cells (Alvarez-Erviti et al., 2011; Vingtdeux et al., 2007; Wei et al., 2013). Mutations of VPS4 gene required for MVB maturation and fusion with lysosome increased the levels of EV-associated proteins within cells (Hasegawa et al., 2011). In addition, there is evidence that MVBs may be fused with autophagosomes to form amphisomes and subsequently fuse with lysosomes to terminate MVB fate (Baixauli, Lopez-Otin, & Mittelbrunn, 2014; Fader, Sanchez, Furlan, & Colombo, 2008; Murrow & Debnath, 2015). However, most of these previous studies were based on an assumption that lysosomes are passively receiving MVBs to fuse for degradation of these vesicles or their content. In fact, there is considerable evidence that lysosomes have trafficking function within different cells (Bhat, Li, et al., 2020; Bhat, Yuan, Cain, Salloum, & Li, 2020; Bhat, Yuan, Camus, Salloum, & Li, 2020; Yuan et al., 2019). In this regard, our recent studies have demonstrated that acid ceramidase (AC) controls lysosomal Ca2+ release through transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 (TRPML1) channel to regulate lysosome trafficking in different types of cells (Bhat, Li, et al., 2020; Li, Huang, et al., 2020; Li et al., 2019). Together, these findings raised the possibility that lysosomes may actively traffic and fuse to MVBs to determine MVB fate and exosome secretion in ECs. Meanwhile, AC activity and TRPML1 channel-mediated Ca2+ release may be importantly involved in the lysosomal regulation of exosome release in ECs.

In the present study, we hypothesized that AC controls lysosomal Ca2+ release through TRPML1 channel to regulate exosome release in murine coronary arterial endothelial cells (CAECs). To test this hypothesis, we examined whether exosome release from CAECs is enhanced by Asah1 gene knockout. Also, we determined whether Asah1 gene deletion affects lysosome trafficking and lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs. Moreover, we examined the effects of Asah1 gene deletion and AC-associated sphingolipids on TRPML1 channel activity in these cells. Finally, we tested whether dynein is involved in the lysosomal regulation of exosome release in CAECs. Our results suggest that AC controls lysosome trafficking and lysosome-MVB interaction to determine MVB fate and exosome release in CAECs through TRPML1-dynein signaling pathway. Asah1 gene defect inhibits TRPML1 channel activity and thereby amplifies exosome release, which may contribute to the development of coronary arterial disease under pathological conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Isolation and culture of CAECs from mouse coronary artery

Isolation of mouse CAECs was carried out and characterized as previously described (Kobayashi, Inoue, Warabi, Minami, & Kodama, 2005; Li, Han, et al., 2013). Briefly, the heart was excised and put into a petri-dish filled with ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit (KH) solution. The cleaned heart with intact aorta was filled with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) using a 25-gauge needle. The opening of the needle was inserted deep into the heart close to the aortic valve. The aorta was tied with the needle as close to the base of the heart as possible. The pump was started with a 20-mL syringe containing warm HBSS at a rate of 0.1 mL/min, and the heart was then flushed for 15 min. HBSS was replaced with warm enzyme solution (1 mg/mL collagenase type I, 0.5 mg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor, 3% BSA, and 2% antibiotic-antimycotic), which was flushed through the heart at a rate of 0.1 mL/min. Perfusion fluid was collected at 30-, 60-, and 90-min intervals. At 90 min, the heart was cut with scissors, and the apex was opened to flush out the cells that collected inside the ventricle. After centrifugation of the cell suspension at 1000 rpm for 10 min, the cell pellet was resuspended with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium and cultured on a 2% gelatin-coated flask at 37 °C before use in experiments.

2.2. GCaMP3 Ca2+ imaging

At 18–24 h after nucleofection with GCaMP3-ML1, CAECs were used for experiments (Li et al., 2019). The fluorescence intensity at 470 nm (F470) was recorded with a digital camera (Nikon Diaphoto TMD Inverted Microscope). Metafluor imaging and analysis software were used to acquire, digitize and store the images for offline processing and statistical analysis (Universal Imaging, Bedford Hills, NY, USA). Lysosomal Ca2+ release was measured under a “low” external Ca2+ solution, which contained 145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM EGTA, and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4).

2.3. Isolation of lysosomes from CAECs

After treatment with vacuolin-1 (1 μM) for 2h, isolation of lysosomes was performed (Schieder, Rotzer, Bruggemann, Biel, & Wahl-Schott, 2010). After washing CAECs with pre-cooled PBS, pre-cooled homogenization buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris, pH = 7.4) was used for detachment of CAECs by a cell scraper. The cell suspension in glass-grinding vessel was homogenized using a Teflon pestle operated at 900 rotations per minute (rpm). The homogenate was then transferred to a 1.5 mL microfuge test tube and centrifuge at 14,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation, the middle part of supernatant was transferred to a 10-mL polycarbonate centrifuge tube. An equal volume of 16 mM CaCl2 was added to precipitate lysosomes. After being shaken on a rotary shaker at 100 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was centrifuged at 25,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C in an ultracentrifuge. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in one volume of ice cold washing buffer (150 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris, pH = 7.4). The suspension was centrifuged at 25,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C in an ultracentrifuge. After the supernatant was discarded, the pellet containing lysosomes was resuspended in 40 μL of washing buffer, which was used for whole-lysosome patch clamp recording. All steps were performed on ice to minimize the activation of intracellular phospholipases and proteases that could damage the lysosomes. Lysosomes were used for electrophysiological recordings within 3 h of isolation to keep lysosomes fresh. To confirm the purity of isolated lysosomes, CytoPainter lysosome staining kit (abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) was used to stain the lysosomes in CAECs before lysosome isolation. The dye working solution was added to the culture medium and incubated at 37 °C for 2h. After lysosome isolation, the green fluorescence at Ex/Em = 490/525 nm of samples were detected using Guava Easycyte Mini Flow Cytometry System (Guava Technologies, Hayward, CA, USA). The data were analyzed using Guava acquisition and analysis software (Guava Technologies, Hayward, CA, USA).

2.4. Whole-lysosome patch clamp recording

CAECs were treated with vacuolin-1 (1 μM) for 2 h to increase the size of lysosomes. Using a planar patch clamp system, Port-a-Patch (Nanion Technologies), the whole-lysosome electrophysiology was performed on isolated lysosomes from CAECs (Schieder et al., 2010). The bath solution contained 60 mM KMSA, 60 mM KF, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2, 2 mM CaMSA was added immediately before starting the measurements to avoid precipitation of CaF2). The luminal solution contained 70 mM KMSA, 60 mM CaMSA, 2 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 4.6). The planar patch-clamp technology was combined with a pressure control system and microstructured glass chips containing an aperture of around 1 μm diameter (resistances of 10–15 MΩ) (Nanion Technologies). Currents were recorded using an EPC-10 patch-clamp amplifier and PatchMaster acquisition software (HEKA). Data were digitized at 40 kHz and filtered at 2.8 kHz. The membrane potential was held at −60 mV, and 500 ms voltage ramps from −200 to +100 mV were applied every 5 s. All recordings were obtained at room temperature (21–23 °C) and all recordings were analyzed using PatchMaster (HEKA) and Origin 6.1 (OriginLab). The salt-agar bridges were used to connect the reference Ag/AgCl wire to the bath solution to minimize voltage offsets. Ag/AgCl-coated electrodes were chloridated in bleach solution approximately 15 min until a black AgCl-layer was obvious on the silver wire. The liquid junction potential was corrected.

2.5. Structured illumination microscopy

After treatments followed by fixation, the cells were incubated with rabbit anti-Rab7a antibody (1:100; Abcam Biotechnology, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and rat anti-Lamp-1 antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) overnight at 4 °C. After washing the slides, Alexa 488-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200; Life Technologies, CA, USA) and Alexa 594-labeled anti-rat secondary antibody (1:200; Life Technologies, CA, USA) were added to the cell slides and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were then washed, stained with DAPI, and mounted. A Nikon fluorescence microscope in the structured illumination microscopy (SIM) mode was used to obtain images. Image Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA) was employed to analyze colocalization, expressed as the Pearson correlation coefficient (Li, Huang, Li, Ritter, & Li, 2021).

2.6. Nanoparticle tracking analysis

Nanoparticle tracking analysis measurements were performed with a NanoSight NTA3.2 Dev Build 3.2.16 (Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK), equipped with a sample chamber with a 638-nm laser and a Viton fluoroelastomer O-ring. The samples were injected in the sample chamber with sterile syringes (BD, New Jersey, USA) until the liquid reached the tip of the nozzle. All measurements were performed at room temperature. The screen gain and camera level were 10 and 13, respectively. Each sample was measured at standard measurement, 30 s with manual shutter and gain adjustments. Three measurements of each sample were performed. 3D figures were exported from the software. Particles sized between 50 and 100 nm were calculated (Li et al., 2019).

2.7. Dynamic analysis of lysosome movement in CAECs

CAECs cultured in 35 mm dish were incubated with 50 nM LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 2h. The confocal fluorescent microscopic recording was conducted with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Fluoview FV1000, Olympus, Japan). The fluorescent images for lysosomes in CAECs were continuously recorded at an excitation/emission (nm) of 555/565 by using XYT recording mode with a speed of 1 frame/10 s for 10 min. Lysosome tracking was performed in Image J using manual tracking plugin as described in previous studies (Jahreiss, Menzies, & Rubinsztein, 2008; Xu et al., 2013). Ten lysosomes were chosen at random for each cell. These lysosomes were then tracked manually, while the program calculated velocity of lysosome trafficking for each frame.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All of the values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Significant differences among multiple groups were examined using t-test or ANOVA followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

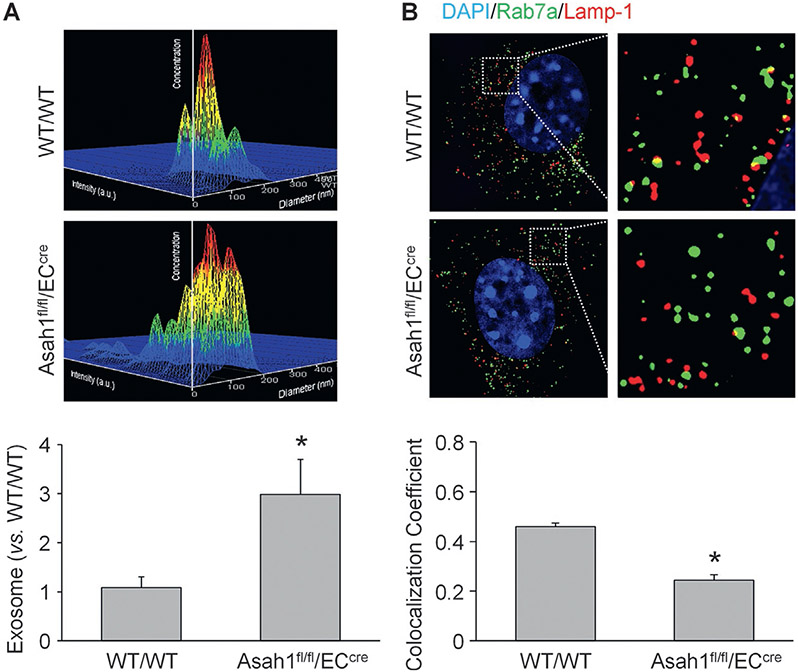

3.1. Elevation of exosome release and reduction of lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene

We isolated and cultured CAECs from WT/WT and endothelial cell-specific Asah1 gene (gene encoding AC) knockout (Asah1fl/fl/ECcre) mice. By nanoparticle tracking analysis, we first measured exosome release from CAECs with or without Asah1 gene. In Fig. 1A, the representative 3-D histograms showed that the exosome concentration in culture medium of WT/WT CAECs was lower than CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. The summarized data suggest that Asah1 gene deletion remarkably increased exosome release from CAECs. Moreover, we observed the interaction of lysosomes (Lamp-1, a lysosome marker stained with red fluorescence) and MVBs (Rab7a, a MVB marker stained with green fluorescence) in CAECs with or without AC function by super-resolution microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1B, considerable amount of lysosome-MVB interaction was observed in the cytosol of WT/WT CAECs. Asah1 gene knockout, however, decreased the encounter and fusion of lysosomes and MVBs in CAECs. The summarized data demonstrated that colocalization of Rab7a and Lamp-1 was significantly reduced by Asah1 gene knockout in CAECs.

Fig. 1.

Elevation of exosome release and reduction of lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. (A) Representative images and summarized data showing that exosome release from CAECs was remarkably elevated in by Asah1 gene deletion (n = 6). The x axis is diameter (nm); the y axis is concentration; the z axis is intensity (a.u.). (B) Representative images and summarized data showing that lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs was significantly attenuated by Asah1 gene deletion (n = 3). * p < 0.05 vs. WT/WT group.

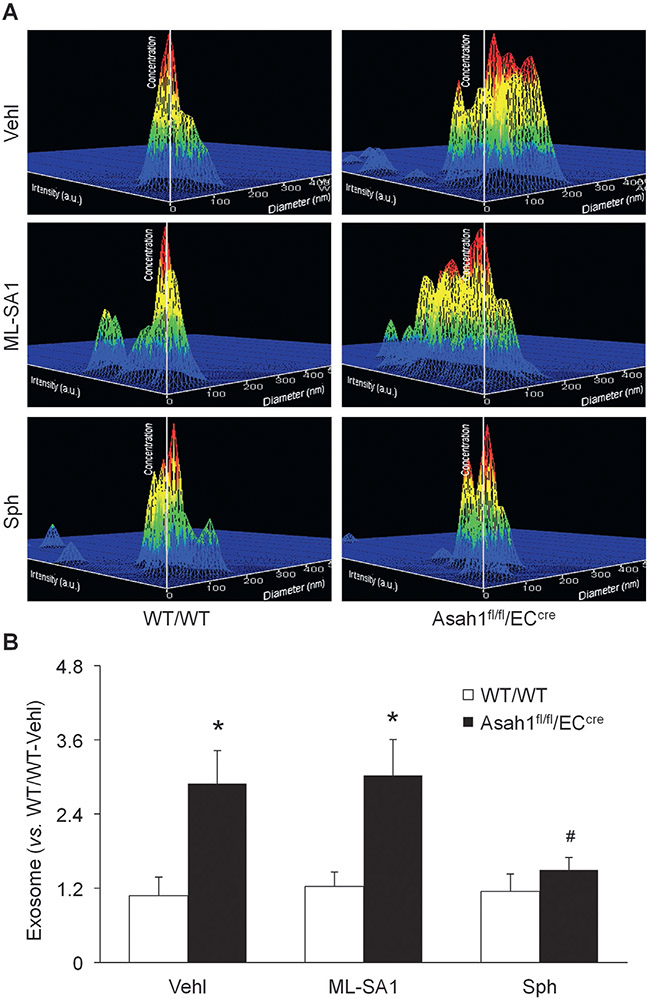

3.2. Inhibition of exosome release from CAECs lacking Asah1 gene by sphingosine

Given that TRPML1 channel governs lysosomal Ca2+ release to regulate lysosomal functions such as trafficking (Li, Huang, et al., 2020; Li et al., 2019), we hypothesized that AC may control TRPML1 channel activity to regulate lysosome trafficking and fusion to MVBs and thereby determine exosome release from CAECs. To test this hypothesis, we treated CAECs of WT/WT and Asah1fl/fl/ECcre mice with vehicle, ML-SA1, or sphingosine for 24h before nanoparticle tracking analysis. As shown in Fig. 2, Asah1 gene knockout remarkably amplified exosome release from CAECs. ML-SA1, a TRPML1 channel agonist, failed to alter the elevation of exosome secretion from CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. Sphingosine as the product of ceramide metabolism by AC, however, substantially reduced exosomes released into culture medium by CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. In WT/WT CAECs, ML-SA1 and sphingosine had no significant effects on exosome release.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of exosome release from CAECs lacking Asah1 gene by sphingosine. (A) Representative images showing exosomes released into the culture medium of CAECs of WT/WT and Asah1fl/fl/ECcre mice under different conditions. The x axis is diameter (nm); the y axis is concentration; the z axis is intensity (a.u.). (B) Summarized data showing that sphingosine (10 μM), but not ML-SA1 (10 μM), inhibited exosome secretion from CAECs lacking Asah1 gene (n = 6). * p < 0.05 vs. WT/WT group. # p < 0.05 vs. Vehl group. Vehl, vehicle; Sph, sphingosine.

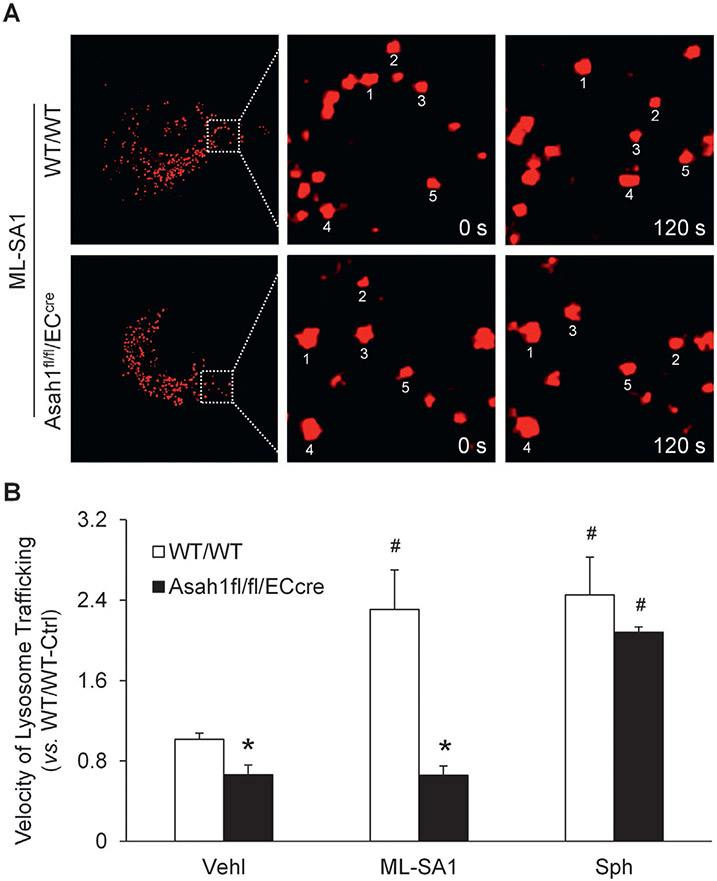

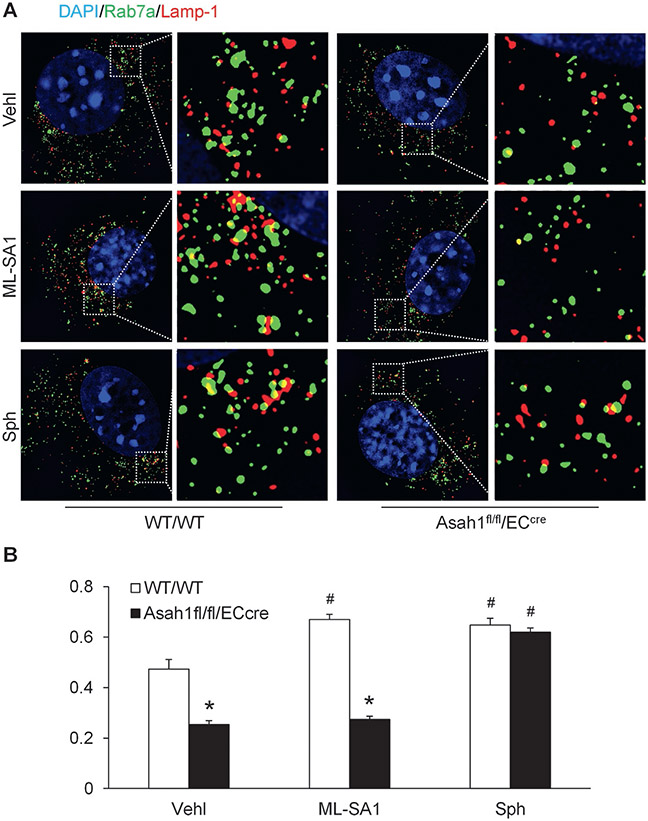

3.3. Regulation of lysosome trafficking and lysosome-MVB interaction by ML-SA1 and sphingosine in CAECs

To examine the role of TRPML1 channel in the regulation of lysosome function and exosome release in CAECs, we tested whether lysosome trafficking is controlled by TRPML1 channel in these cells. LysoTracker Red DND-99 was loaded into live CAECs and the lysosome movement was continuously monitored for 10 min under different conditions. After treatment with ML-SA1, lysosome movement was obviously faster in WT/WT CAECs compared to CAECs lacking Asah1 gene (Fig. 3A). The summarized data suggested that Asah1 gene deletion significantly inhibited lysosome trafficking in CAECs. ML-SA1 enhanced lysosome trafficking in WT/WT CAECs but failed to affect lysosome movement in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. However, sphingosine enhanced lysosome trafficking in CAECs of both WT/WT and Asah1fl/fl/ECcre mice (Fig. 3B). By super-resolution microscopy, we found that ML-SA1 significantly increased lysosome-MVB interaction in WT/WT CAECs, but not in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. Nevertheless, sphingosine enhanced lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs regardless of Asah1 gene expression (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Effects of ML-SA1 and sphingosine on lysosome trafficking in CAECs. (A) Representative images showing that ML-SA1 enhanced lysosome trafficking in WT/WT CAECs, but not CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. (B) Summarized data showing velocity of lysosome trafficking in CAECs of WT/WT and Asah1fl/fl/ECcre mice under different conditions (n = 3–4). * P < 0.05 vs. WT/WT group. # P < 0.05 vs. Vehl group.

Fig. 4.

Regulation of lysosome-MVB interaction by ML-SA1 and sphingosine in CAECs. (A) Representative images showing lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs of WT/WT and Asah1fl/fl/ECcre mice under different conditions. (B) Summarized data showing lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs of WT/WT and Asah1fl/fl/ECcre mice under different conditions (n = 3). * P < 0.05 vs. WT/WT group. # P < 0.05 vs. Vehl group.

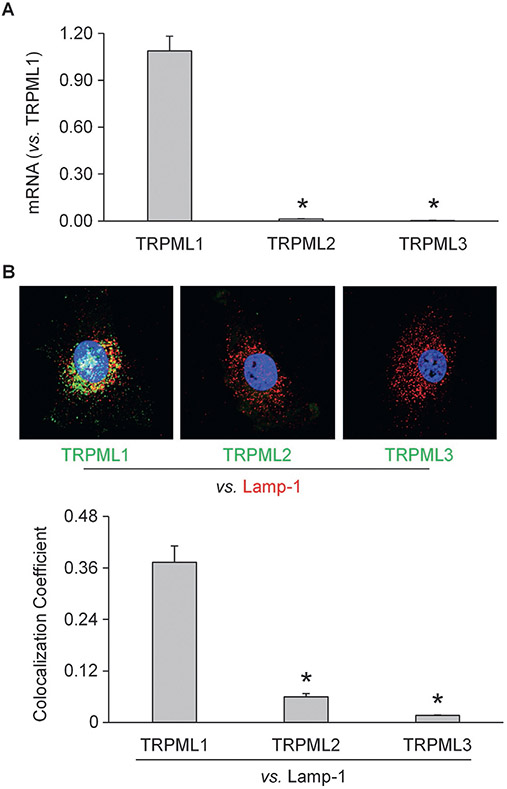

3.4. Characterization of TRPML channels in CAECs

To further address the critical role of lysosomal TRPML1 in AC-mediated regulation of lysosome trafficking and exosome secretion, we characterized this channel in mouse CAECs. By RT-PCR, we found that the expression level of TRPML1 was remarkably higher than TRPML2 and TRPML3 in cultured CAECs (Fig. 5A). To further confirm our findings, confocal microscopy demonstrated that TRPML1 was abundantly expressed in CAECs and highly colocalized with Lamp-1, a lysosome marker. On the contrary, the expressions of TRPML2 and TRPML3 and their colocalizations with Lamp-1 were markedly lower than TRPML1 (Fig. 5B). These experiments provided the first evidence showing the expression of TRPML1 in murine CAECs.

Fig. 5.

Characterization of TRPML channels in CAECs. (A) Summarized data showing relative mRNA levels of TRPML1, TRPML2, and TRPML3 in murine CAECs detected by RT-PCR (n = 6). (B) Representative images and summarized data showing that TRPML1, but not TRPML2 or TRPML3, was abundantly expressed in murine CAECs (n = 4). * p < 0.05 vs. relative mRNA level of TRPML1 (Fig. 2A) or colocalization coefficient of TRPML1 and Lamp-1 (Fig. 2B).

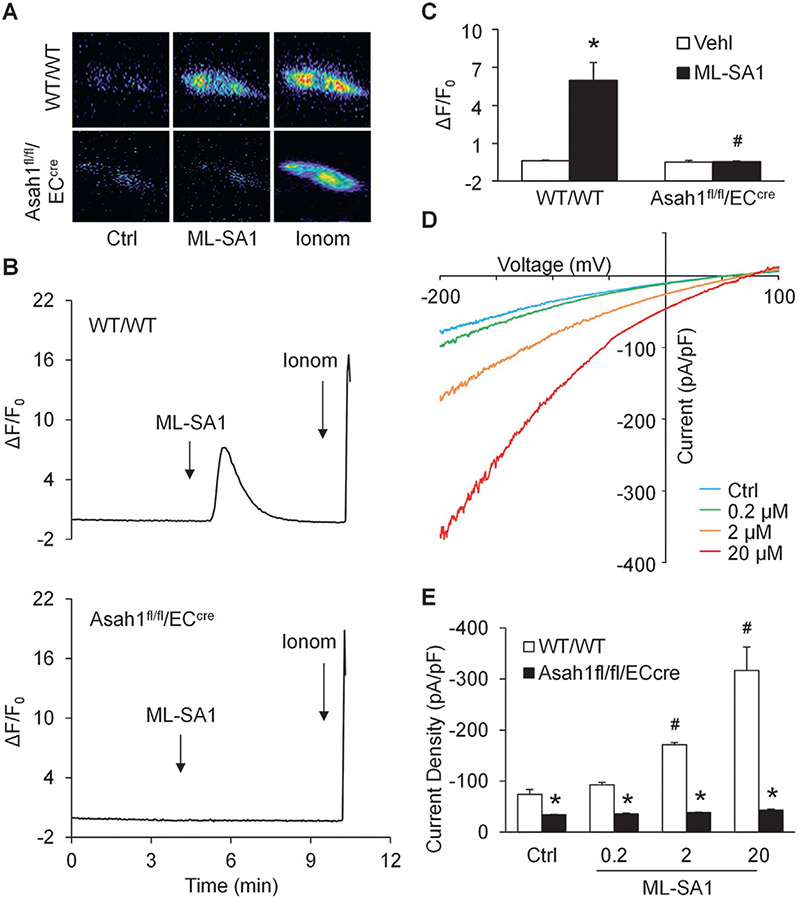

3.5. Blockade of TRPML1 channel by Asah1 gene deletion in CAECs

To specifically detect lysosomal Ca2+ release through TRPML1 channel, nucleofection of GCaMP3-ML1 plasmid into CAECs was performed to express GCaMP3, a single-wavelength genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator, on the cytoplasmic amino terminus of TRPML1 in these cells as described in our previous studies (Li, Huang, et al., 2020; Li et al., 2019). A fluorescent microscopic imaging system was used to dynamically and continuously monitor the GCaMP3 fluorescence signal (F470) in CAECs. The intensity of Ca2+-induced GCaMP3 fluorescence indicated the amount of Ca2+ released through lysosomal TRPML1 channel. As shown in Fig. 6A, the GCaMP3 fluorescence detected in WT/WT CAECs was dim under control condition. ML-SA1 remarkably increased the GCaMP3 fluorescence in WT/WT CAECs, but not in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. Fig. 6B showed that addition of ML-SA1 to the extracellular solution induced a rapid elevation of GCaMP3 fluorescence in WT/WT CAECs, which was followed by a large signal increase caused by late addition of ionomycin, a Ca2+ ionophore. In contrast, ML-SA1 failed to augment GCaMP3 fluorescence in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene, while ionomycin still induced a dramatic elevation of GCaMP3 fluorescence in these cells. The summarized data suggested that Asah1 gene deletion impaired lysosomal Ca2+ release through TRPML1 channel in CAECs (Fig. 6C). To further confirm our findings, we isolated lysosomes from CAECs of WT/WT and Asah1fl/fl/ECcre mice for whole-lysosome patch clamping. After treatment with vacuolin-1, lysosomes were enlarged and then isolated from CAECs for experiments as described in our previous studies (Li, Huang, et al., 2020; Li et al., 2019). It was found that bath application of ML-SA1 induced whole-lysosome TRPML1 channel-mediated Ca2+ currents of WT/WT CAECs in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6D). However, there was no significant elevation observed in lysosomal Ca2+ currents after addition of ML-SA1 into bath solution of lysosomes isolated from CAECs lacking Asah1 gene (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

Blockade of TRPML1 channel by Asah1 gene deletion in CAECs. (A) Representative images showing that ML-SA1 (20 μM) induced TRPML1 channel-mediated Ca2+ release in WT/WT CAECs, but not CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. (B) Representative curves showing that ML-SA1 induced elevation of GCaMP3 signal in WT/WT CAECs, but not in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. (C) Summarized data showing that Asah1 gene deletion blocked TRPML1-mediated Ca2+ release induced by ML-SA1 in CAECs (n = 4–5). (D) Representative whole lysosome currents of WT/WT CAECs enhanced by ML-SA1 in different doses. (E) ML-SA1 enhanced TRPML1 channel activity of lysosomes isolated from WT/WT CAECs in a concentration-dependent manner. However, ML-SA1 failed to enhance TRPML1 channel activity of lysosomes isolated from CAECs lacking Asah1 gene (n = 3). * p < 0.05 vs. Vehl group (Fig. 3D) or WT/WT group (Fig. 3F), # p < 0.05 vs. WT/WT group (Fig. 3D) or Ctrl group (Fig. 3F). Ctrl, control; Ionom, ionomycin; Vehl, vehicle.

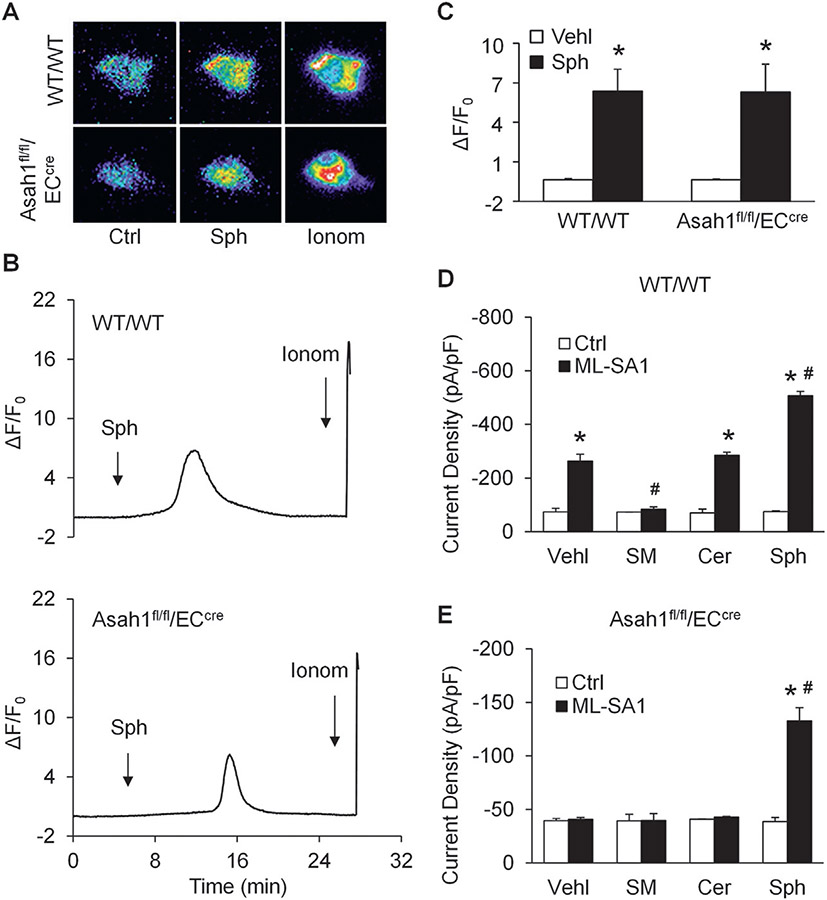

3.6. Rescue of TRPML1 channel activity by sphingosine in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene

Next, we examined the effect of sphingosine on TRPML1 channel activity. By GCaMP3 Ca2+ imaging, sphingosine was found to induce lysosomal Ca2+ release through TRPML1 channel in CAECs of both WT/WT and Asah1fl/fl/ECcre mice, indicating that sphingosine rescued TRPML1 channel activity in CAECs lacking the Asah1 gene (Fig. 7A-C).

Fig. 7.

Rescue of TRPML1 channel activity by sphingosine in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. (A) Representative images showing that sphingosine (20 μM) induced TRPML1 channel-mediated Ca2+ release in CAECs regardless of Asah1 gene expression. (B) Representative curves showing that sphingosine induced elevation of GCaMP3 signal in CAECs regardless of Asah1 gene expression. (C) Summarized data showing that sphingosine induced TRPML1-mediated Ca2+ release in CAECs regardless of Asah1 gene expression (n = 3–4). (D) Summarized data of the effects of various sphingolipids on whole lysosome currents of lysosomes isolated from WT/WT CAECs (n = 4). (E) Summarized data of the effects of various sphingolipids on whole lysosome currents of lysosomes isolated from CAECs lacking Asah1 gene (n = 4). * p <0.05 vs. Vehl group (Fig. 4D) or WT/WT group (Fig. 4E and F), # p < 0.05 vs. Ctrl group (Fig. 4E and F). Ctrl, control; Ionom, ionomycin; Vehl, vehicle; Sph, sphingosine; Cer, ceramide; SM, sphingomyelin.

To further dissect the actions of AC-associated sphingolipids on the opening of TRPML1 channel, whole-lysosome patch clamping was performed to measure ML-SA1-induced whole-lysosome TRPML1 channel-mediated Ca2+ currents of CAECs with or without Asah1 gene in the presence of AC-associated sphingolipids to determine their regulatory roles on TRPML1 channel activity. We demonstrated that sphingomyelin, ceramide, and sphingosine had different effects on whole-lysosome TRPML1 channel-mediated Ca2+ currents of WT/WT CAECs, with inhibition by sphingomyelin, no effects by ceramide, but enhancement by sphingosine. Although both sphingomyelin and ceramide had no effects on whole-lysosome TRPML1 channel-mediated Ca2+ currents of CAECs lacking Asah1 gene, sphingosine remained to increase TRPML1 channel activity in these lysosomes (Fig. 7D and E).

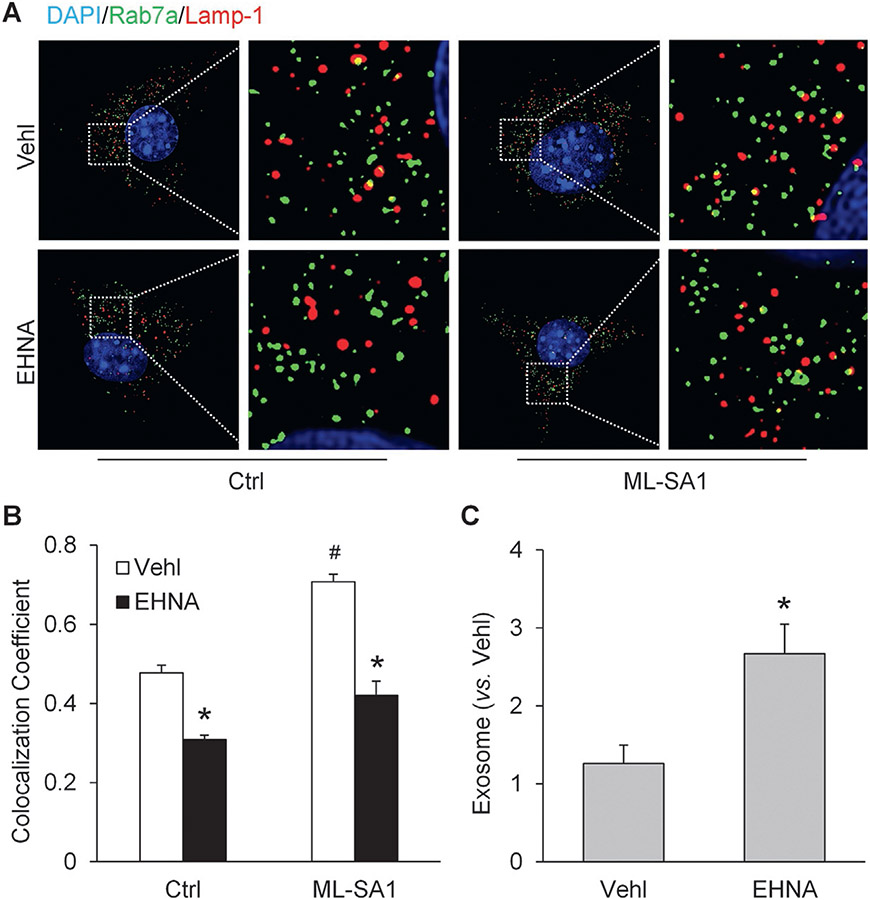

3.7. Contribution of dynein activity to lysosomal regulation of exosome release in CAECs

We also tested whether dynein plays an important role in the lysosomal regulation of exosome release in CAECs. Super-resolution microscopy showed that EHNA, a dynein inhibitor, significantly reduced lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs. Moreover, the elevation of lysosome-MVB interaction by ML-SA1 was substantially inhibited by EHNA (Fig. 8A). Correspondingly, we found that inhibition of dynein activity by EHNA remarkably elevated exosome release from CAECs (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Contribution of dynein activity to lysosomal regulation of exosome release in CAECs. (A) Representative images showing lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs under different conditions. (B) Summarized data showing lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs under different conditions (n = 3). (C) Summarized data showing that EHNA (30 μM) increased exosome release from CAECs (n = 5). * p < 0.05 vs. Vehl group, # p < 0.05 vs. Ctrl group. Vehl, vehicle; Ctrl, control; EHNA, erythro-9-(2-hydroxy-3-nonyl)adenine.

4. Discussion

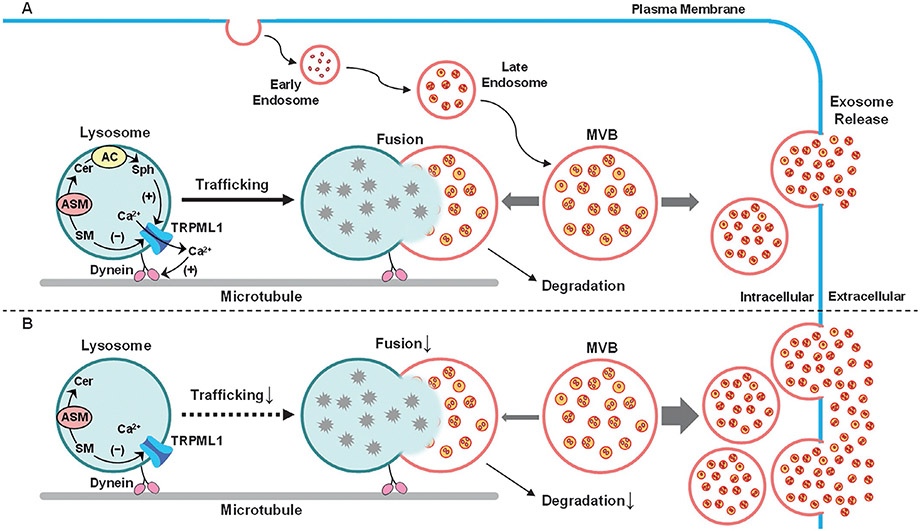

The major goals of the present study were to determine whether lysosomal AC deficiency enhances exosome release through inhibition of lysosome-dependent MVB degradation in CAECs and to explore the mechanisms by which AC regulates lysosome trafficking, lysosome-MVB interaction, and exosome secretion in these cells. It was found that Asah1 gene deletion inhibited lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs, which was accompanied by enhancement of exosome release from these cells. We further demonstrated that lysosomal TRPML1 channel was blocked in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. Interestingly, sphingosine as the product of ceramide metabolism by AC rescued TRPML1 channel activity in CAECs with AC deficiency. Moreover, we found that AC-dependent TRPML1 channel activity importantly contributed to lysosome trafficking and lysosomal regulation of exosome release in CAECs. Inhibition of dynein activity also affected lysosome-MVB interaction and exosome secretion in these cells, which confirmed that lysosomal regulation of exosome secretion was attributed to lysosome trafficking (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Regulation of exosome release by AC-TRPML1-dynein signaling pathway in CAECs. (A) Exosomes in CAECs are formed as intraluminal vesicles of MVBs via endocytic process. MVBs can fuse with and deliver content to lysosomes for degradation or fuse with plasma membrane to release intraluminal vesicles as exosomes, which is regulated by lysosome trafficking and fusion to MVBs, a mechanism constitutively controlling the fate of MVBs. The AC-associated sphingolipids such as sphingosine and sphingomyelin gate TRPML1 channel activity, which drives lysosome trafficking to and fusion with MVBs for degradation preventing exosome secretion in a dynein-dependent manner. (B) If AC in CAECs is defective or deficient, lysosome trafficking, lysosome-MVB interaction, and lysosome-dependent MVB degradation may be inhibited, leading to enhancement of exosome release. MVB, multivesicular body; Sph, sphingosine; Cer, ceramide; SM, sphingomyelin; TRPML1, transient receptor potential-mucolipin 1.

As a lysosomal enzyme, AC determines tissue or cellular ceramide levels under physiological and pathological conditions (Coant, Sakamoto, Mao, & Hannun, 2017; Li, Kidd et al., 2020). It has been reported that mutations in the AC gene (ASAH1) or deficiency of lysosomal AC activity (metabolism of ceramide to sphingosine) in human cells are a major genetic or pathogenic mechanism for the development of Farber disease, which results in derangement of metabolic homeostasis (Masuko et al., 2009; Schuchman, 2016), EC dysfunction, and vascular injury (Feng et al., 2019; Sikora et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2019). Recently, we have demonstrated that AC controls exosome secretion from CAECs and thereby regulates exosome-mediated release of NLRP3 inflammasome products from these cells during hyperglycemia (Yuan et al., 2019). EC-specific Asah1 gene deletion aggravates hyperglycemia-induced arterial inflammatory response through amplification of inflammatory exosome release from CAECs (Yuan et al., 2019). However, the molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of exosome release by AC remains poorly understood. In the present study, we demonstrated that decreased lysosome-MVB interaction was associated with elevated exosome release in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene. Our findings indicate that the lysosome determines MVB fate and controls exosome release in CAECs. In this regard, it has been reported that inhibition of lysosome function with different alkaline agents or lysosomal v-ATPase inhibitor, bafilomycin A, or chloroquine can increase exosome secretion in different cells such as neurons, epithelial cells, and vascular cells (Alvarez-Erviti et al., 2011; Vingtdeux et al., 2007; Wei et al., 2013). Mutations of VPS4 gene required for MVB maturation and fusion with lysosome increased the levels of EV-associated proteins within cells (Hasegawa et al., 2011). In addition, there is evidence that MVBs may be fused with autophagosomes to form amphisomes and subsequently fuse with lysosomes to terminate MVB fate (Baixauli et al., 2014; Fader et al., 2008; Murrow & Debnath, 2015). Although our findings suggest that AC may play a vital role in the lysosomal regulation of exosome secretion in CAECs, it remains unknown how AC regulates lysosome function and thereby determines lysosome-MVB interaction and exosome release in these cells.

It has been reported that MVBs and lysosomes are concentrated near the microtubule-organizing center in the juxtanuclear region of the cell, suggesting that both MVBs and lysosomes need to traffic along microtubules to encounter, kiss and fuse (Bright, Reaves, Mullock, & Luzio, 1997; Futter et al., 1996; Mullock, Bright, Fearon, Gray, & Luzio, 1998; Ward, Pevsner, Scullion, Vaughn, & Kaplan, 2000). In fact, there is considerable evidence that lysosomes have trafficking function within different cells (Bhat, Li, et al., 2020; Bhat, Yuan, Cain, et al., 2020; Bhat, Yuan, Camus, et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2019). In our previous studies, we found that lysosome trafficking is a main regulatory mechanism of autophagic flux and exosome secretion in vascular smooth muscle cells and renal podocytes, which may depend upon the Ca2+ bursts from lysosomes (Bhat, Li, et al., 2020; Li et al., 2019). It has been shown that Ca2+ enters lysosomal compartment by H+/Ca2+ exchange under resting condition and is released through TRPML1 channels in response to endogenously produced NAADP (Churchill et al., 2002; Dell’Angelica, Mullins, Caplan, & Bonifacino, 2000; Galione, 2006; Zhang et al., 2006; Zhang, Xia, & Li, 2010) or other factors like PIPs (PI(3,5)P2) and irons (Dong et al., 2008; Dong et al., 2010; Li et al., 2016). Based on these previous studies, we hypothesized that AC controls lysosome trafficking and fusion to MVBs via regulation of lysosomal Ca2+ release through TRPML1 channel. We first demonstrated that TRPML1, but not TRPML2 or TRPML3, was abundant in CAECs. Then, we found that ML-SA1 as a TRPML1 channel agonist activated lysosomal Ca2+ release through TRPML1 channel in CAECs. Moreover, lysosome trafficking and lysosome-MVB interactions were enhanced by ML-SA1 in these cells. However, Asah1 gene deletion blocked these actions of ML-SA1 on CAECs. To our knowledge, these results provide the first evidence that regulation of TRPML1 channel-mediated Ca2+ release by AC may serve as a critical mechanism determining exosome release from ECs. In some previous studies, the Ca2+ released from lysosomes has been found to drive lysosome moving to meet with other cellular vesicles such as endosomes, MVBs, autophagosomes, and sarcoplasmic reticulum (Churchill et al., 2002; Kinnear et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2006, 2010; Zhang, Jin, Yi, & Li, 2009; Zhang & Li, 2007). In other cells such as breast cancer cells, epithelial cells and neurons, the Ca2+-dependent lysosome trafficking has also been observed (Dong et al., 2010; Glunde et al., 2003; Li et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2012; Trajkovic et al., 2006). In addition to TRPML1 channel, other channels such as two-pore channels may also be implicated in lysosomal Ca2+ release, but they may form hybrids with TRPML1 and need accessory proteins to exert their action (Guse, 2012; Li, Zhang, Abais, Ritter, & Zhang, 2013).

After confirmation of deficient TRPML1 channel activity as an important mechanism, we went on to address how AC controlled TRPML1 channel-mediated Ca2+ release and how Asah1 gene deletion blocked TRPML1 channel in CAECs. The lysosomal TRPML1 channel activity has been shown to be regulated by sphingolipids. Accumulated sphingomyelin was found to inhibit lysosomal TRPML1 channel activity and reduce lysosomal Ca2+ release, blunting lysosome trafficking that leads to lysosomal storage disease as shown in Niemann-Pick disease and other diseases, including minimal change disease in the kidney (Li et al., 2019; Piccoli et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2012). Sphingosine, the product of ceramide metabolism by AC, enhanced lysosomal Ca2+ release through TRPML1 channel and promoted lysosome trafficking in some epithelial cells (Li et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2012). We tested whether deficiency of TRPML1 channel activity was attributed to altered ceramide metabolism by AC. We found that sphingosine activated TRPML1 channel-mediated Ca2+ release in CAECs with or without Asah1 gene, suggesting that sphingosine production by AC is essential for the normal function of TRPML1 channel. Correspondingly, sphingosine recovered lysosome trafficking and lysosome-MVB interaction in CAECs lacking Asah1 gene, leading to reduction of exosome release from these cells. Moreover, we found that TRPML1 channel activity was inhibited by sphingomyelin but not affected by ceramide, the substrate of AC. To our knowledge, there have been no reports on the role of sphingolipids in the regulation of TRPML1 channel activity in ECs. Our results provide direct evidence that AC-dependent production of sphingosine critically contributes to TRPML1 channel activation and consequent lysosomal regulation of exosome secretion in ECs. In studies using other cell types, it has been shown that the spontaneous elevation of intracellular sphingosine levels via caged sphingosine leads to a significant and transient calcium release from lysosomes, which is independent of sphingosine-1-phosphate, extracellular calcium level, and ER calcium level (Hoglinger et al., 2015). Moreover, we have demonstrated that Asah1 gene deletion induces ceramide accumulation and sphingosine reduction in podocytes (Li, Huang, et al., 2020). Our findings together with these previous results provide strong evidence that reduced production of sphingosine due to AC deficiency leads to inhibition of TRPML1 channel-mediated Ca2+ release, thereby enhancing exosome release in CAECs due to deficient lysosome trafficking and attenuated lysosome-MVB interaction.

Another interesting finding of the present study is that the enhancement of lysosome-MVB interaction by ML-SA1 was prevented by inhibition of dynein activity in CAECs. Also, elevation of exosome release was associated with inhibition of dynein activity in these cells. As a motor protein, dynein mediates the movement of organelles, including lysosomes, from the plus end to the minus end of microtubules, which is known as retrograde transport (Pu, Guardia, Keren-Kaplan, & Bonifacino, 2016). Interaction with dynactin and formation of dynein-dynactin complex are required for the association of dynein and lysosome (Burkhardt, Echeverri, Nilsson, & Vallee, 1997; Lin & Collins, 1992). More recently, it has been reported that ALG-2, a lysosomal Ca2+-sensor, promotes interaction of TRPML1 channel with dynein–dynactin complex to regulate centripetal transport of lysosomes in response to lysosomal Ca2+ release through the TRPML1 channel (Li et al., 2016). Based on these previous studies, our findings further confirm that lysosome trafficking is essential for the lysosomal regulation of exosome release in ECs, which depends on the normal activity of AC, TRPML1 channel, and dynein. Activation of TRPML1 channels contributes to the lysosomal regulation of exosome secretion through dyneinependent lysosome trafficking and fusion to MVB in these cells. The lysosome-MVB fusion may lead to MVB degradation and thereby maintain the speed of exosome release from ECs under control.

In summary, the present study revealed a new regulatory mechanism of exosome release from ECs. The functional deficiency of AC and consequent dysregulation of AC-TRPML1-dynein signaling pathway in CAECs may represent a novel early event in the pathogenesis of coronary arterial disease. These results provide the impetus for development of new therapeutic strategies targeting AC activity for prevention or treatment of coronary arterial disease associated with lysosome dysfunction and elevation of exosome release in CAECs under different pathological conditions, such as hypercholesterolemia, hyperhomocysteinemia, and hyperglycemia.

References

- Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Schapira AH, Gardiner C, Sargent IL, Wood MJ, et al. (2011). Lysosomal dysfunction increases exosome-mediated alpha-synuclein release and transmission. Neurobiology of Disease, 42(3), 360–367. 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baixauli F, Lopez-Otin C, & Mittelbrunn M (2014). Exosomes and autophagy: Coordinated mechanisms for the maintenance of cellular fitness. Frontiers in Immunology, 5, 403. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat OM, Li G, Yuan X, Huang D, Gulbins E, Kukreja RC, et al. (2020). Arterial medial calcification through enhanced small extracellular vesicle release in smooth muscle-specific Asah1 gene knockout mice. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1645. 10.1038/s41598-020-58568-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat OM, Yuan X, Cain C, Salloum FN, & Li PL (2020). Medial calcification in the arterial wall of smooth muscle cell-specific Smpd1 transgenic mice: A ceramide-mediated vasculopathy. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 24(1), 539–553. 10.1111/jcmm.14761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat OM, Yuan X, Camus S, Salloum FN, & Li PL (2020). Abnormal lysosomal positioning and small extracellular vesicle secretion in arterial stiffening and calcification of mice lacking Mucolipin 1 gene. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(5), 1713. 10.3390/ijms21051713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger CM, Loyer X, Rautou PE, & Amabile N (2017). Extracellular vesicles in coronary artery disease. Nature Reviews. Cardiology, 14(5), 259–272. 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright NA, Reaves BJ, Mullock BM, & Luzio JP (1997). Dense core lysosomes can fuse with late endosomes and are re-formed from the resultant hybrid organelles. Journal of Cell Science, 110(Pt 17), 2027–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt JK, Echeverri CJ, Nilsson T, & Vallee RB (1997). Overexpression of the dynamitin (p50) subunit of the dynactin complex disrupts dynein-dependent maintenance of membrane organelle distribution. The Journal of Cell Biology, 139(2), 469–484. 10.1083/jcb.139.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN, & Bobryshev YV (2015). Extracellular vesicles and atherosclerotic disease. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 72(14), 2697–2708. 10.1007/s00018-015-1906-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill GC, Okada Y, Thomas JM, Genazzani AA, Patel S, & Galione A (2002). NAADP mobilizes Ca(2+) from reserve granules, lysosome-related organelles, in sea urchin eggs. Cell, 111(5), 703–708. 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coant N, Sakamoto W, Mao C, & Hannun YA (2017). Ceramidases, roles in sphingolipid metabolism and in health and disease. Advances in Biological Regulation, 63, 122–131. 10.1016/j.jbior.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crescitelli R, Lasser C, Szabo TG, Kittel A, Eldh M, Dianzani I, et al. (2013). Distinct RNA profiles in subpopulations of extracellular vesicles: Apoptotic bodies, microvesicles and exosomes. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 2(1), 20677. 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport AP, Hyndman KA, Dhaun N, Southan C, Kohan DE, Pollock JS, et al. (2016). Endothelin. Pharmacological Reviews, 68(2), 357–418. 10.1124/pr.115.011833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Angelica EC, Mullins C, Caplan S, & Bonifacino JS (2000). Lysosome-related organelles. The FASEB Journal, 14(10), 1265–1278. 10.1096/fj.14.10.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H, Sun C, Sun Y, Li H, Yang L, Wu D, et al. (2018). Lipid, protein, and MicroRNA composition within mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Cellular Reprogramming, 20(3), 178–186. 10.1089/cell.2017.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XP, Cheng X, Mills E, Delling M, Wang F, Kurz T, et al. (2008). The type IV mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1 is an endolysosomal iron release channel. Nature, 455(7215), 992–996. 10.1038/nature07311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XP, Shen D, Wang X, Dawson T, Li X, Zhang Q, et al. (2010). PI(3,5)P(2) controls membrane trafficking by direct activation of mucolipin ca(2+) release channels in the endolysosome. Nature Communications, 1, 38. 10.1038/ncomms1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fader CM, Sanchez D, Furlan M, & Colombo MI (2008). Induction of autophagy promotes fusion of multivesicular bodies with autophagic vacuoles in k562 cells. Traffic, 9(2), 230–250. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Q, Stork CJ, Xu S, Yuan D, Xia X, LaPenna KB, et al. (2019). Increased circulating microparticles in streptozotocin-induced diabetes propagate inflammation contributing to microvascular dysfunction. The Journal of Physiology, 597(3), 781–798. 10.1113/JP277312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futter CE, Pearse A, Hewlett LJ, & Hopkins CR (1996). Multivesicular endosomes containing internalized EGF-EGF receptor complexes mature and then fuse directly with lysosomes. The Journal of Cell Biology, 132(6), 1011–1023. 10.1083/jcb.132.6.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galione A (2006). NAADP, a new intracellular messenger that mobilizes Ca2+ from acidic stores. Biochemical Society Transactions, 34(Pt 5), 922–926. 10.1042/BST0340922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glunde K, Guggino SE, Solaiyappan M, Pathak AP, Ichikawa Y, & Bhujwalla ZM (2003). Extracellular acidification alters lysosomal trafficking in human breast cancer cells. Neoplasia, 5(6), 533–545. 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80037-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guse AH (2012). Linking NAADP to ion channel activity: A unifying hypothesis. Science Signaling, 5(221), pe18. 10.1126/scisignal.2002890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T, Konno M, Baba T, Sugeno N, Kikuchi A, Kobayashi M, et al. (2011). The AAA-ATPase VPS4 regulates extracellular secretion and lysosomal targeting of alpha-synuclein. PLoS One, 6(12), e29460. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessvik NP, & Llorente A (2018). Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 75(2), 193–208. 10.1007/s00018-017-2595-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoglinger D, Haberkant P, Aguilera-Romero A, Riezman H, Porter FD, Platt FM, et al. (2015). Intracellular sphingosine releases calcium from lysosomes. eLife, 4, e10616. 10.7554/eLife.10616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahreiss L, Menzies FM, & Rubinsztein DC (2008). The itinerary of autophagosomes: From peripheral formation to kiss-and-run fusion with lysosomes. Traffic, 9(4), 574–587. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju R, Zhuang ZW, Zhang J, Lanahan AA, Kyriakides T, Sessa WC, et al. (2014). Angiopoietin-2 secretion by endothelial cell exosomes: Regulation by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and syndecan-4/syntenin pathways. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(1), 510–519. 10.1074/jbc.M113.506899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnear NP, Wyatt CN, Clark JH, Calcraft PJ, Fleischer S, Jeyakumar LH, et al. (2008). Lysosomes co-localize with ryanodine receptor subtype 3 to form a trigger zone for calcium signalling by NAADP in rat pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Cell Calcium, 44(2), 190–201. 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Inoue K, Warabi E, Minami T, & Kodama T (2005). A simple method of isolating mouse aortic endothelial cells. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis, 12(3), 138–142. 10.5551/jat.12.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro-Ibanez E, Sanz-Garcia A, Visakorpi T, Escobedo-Lucea C, Siljander P, Ayuso-Sacido A, et al. (2014). Different gDNA content in the subpopulations of prostate cancer extracellular vesicles: Apoptotic bodies, microvesicles, and exosomes. Prostate, 74(14), 1379–1390. 10.1002/pros.22853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Han WQ, Boini KM, Xia M, Zhang Y, & Li PL (2013). TRAIL death receptor 4 signaling via lysosome fusion and membrane raft clustering in coronary arterial endothelial cells: Evidence from ASM knockout mice. Journal of Molecular Medicine (Berlin, Germany), 91(1), 25–36. 10.1007/s00109-012-0968-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Huang D, Bhat OM, Poklis JL, Zhang A, Zou Y, et al. (2020). Abnormal podocyte TRPML1 channel activity and exosome release in mice with podocyte-specific Asah1 gene deletion. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 1866(2), 158856. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2020.158856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Huang D, Hong J, Bhat OM, Yuan X, & Li PL (2019). Control of lysosomal TRPML1 channel activity and exosome release by acid ceramidase in mouse podocytes. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology, 317(3), C481–C491. 10.1152/ajpcell.00150.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Huang D, Li N, Ritter JK, & Li PL (2021). Regulation of TRPML1 channel activity and inflammatory exosome release by endogenously produced reactive oxygen species in mouse podocytes. Redox Biology, 43, 102013. 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Kidd J, Kaspar C, Dempsey S, Bhat OM, Camus S, et al. (2020). Podocytopathy and nephrotic syndrome in mice with podocyte-specific deletion of the Asah1 gene: Role of ceramide accumulation in glomeruli. The American Journal of Pathology, 190(6), 1211–1223. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Rydzewski N, Hider A, Zhang X, Yang J, Wang W, et al. (2016). A molecular mechanism to regulate lysosome motility for lysosome positioning and tubulation. Nature Cell Biology, 18(4), 404–417. 10.1038/ncb3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li PL, Zhang Y, Abais JM, Ritter JK, & Zhang F, (2013). Cyclic ADP-ribose and NAADP in vascular regulation and diseases. Messenger (Los Angel), 2(2), 63–85. 10.1166/msr.2013.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SX, & Collins CA (1992). Immunolocalization of cytoplasmic dynein to lysosomes in cultured cells. Journal of Cell Science, 101(Pt 1), 125–137. 10.1242/jcs.101.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuko K, Murata M, Suematsu N, Okamoto K, Yudoh K, Nakamura H, et al. (2009). A metabolic aspect of osteoarthritis: Lipid as a possible contributor to the pathogenesis of cartilage degradation. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 27(2), 347–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullock BM, Bright NA, Fearon CW, Gray SR, & Luzio JP (1998). Fusion of lysosomes with late endosomes produces a hybrid organelle of intermediate density and is NSF dependent. The Journal of Cell Biology, 140(3), 591–601. 10.1083/jcb.140.3.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrow L, & Debnath J (2015). ATG12-ATG3 connects basal autophagy and late endosome function. Autophagy, 11(6), 961–962. 10.1080/15548627.2015.1040976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki T, Sugiyama S, Koga H, Sugamura K, Ohba K, Matsuzawa Y, et al. (2009). Significance of a multiple biomarkers strategy including endothelial dysfunction to improve risk stratification for cardiovascular events in patients at high risk for coronary heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 54(7), 601–608. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta I, & Aquila S (2016). Exosomes in human atherosclerosis: An ultrastructural analysis study. Ultrastructural Pathology, 40(2), 101–106. 10.3109/01913123.2016.1154912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccoli E, Nadai M, Caretta CM, Bergonzini V, Del Vecchio C, Ha HR et al. (2011). Amiodarone impairs trafficking through late endosomes inducing a Niemann-pick C-like phenotype. Biochemical Pharmacology, 82(9), 1234–1249. 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.07.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu J, Guardia CM, Keren-Kaplan T, & Bonifacino JS (2016). Mechanisms and functions of lysosome positioning. Journal of Cell Science, 129(23), 4329–4339. 10.1242/jcs.196287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal C, & Harikumar KB (2018). The origin and functions of exosomes in Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology, 8, 66. 10.3389/fonc.2018.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieder M, Rotzer K, Bruggemann A, Biel M, & Wahl-Schott C (2010). Planar patch clamp approach to characterize ionic currents from intact lysosomes. Science Signaling, 3(151), pl3. 10.1126/scisignal.3151pl3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchman EH (2016). Acid ceramidase and the treatment of ceramide diseases: The expanding role of enzyme replacement therapy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1862(9), 1459–1471. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen D, Wang X, Li X, Zhang X, Yao Z, Dibble S, et al. (2012). Lipid storage disorders block lysosomal trafficking by inhibiting a TRP channel and lysosomal calcium release. Nature Communications, 3, 731. 10.1038/ncomms1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikora J, Dworski S, Jones EE, Kamani MA, Micsenyi MC, Sawada T, et al. (2017). Acid ceramidase deficiency in mice results in a broad range of central nervous system abnormalities. The American Journal of Pathology, 187(4), 864–883. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinning JM, Losch J, Walenta K, Bohm M, Nickenig G, & Werner N (2011). Circulating CD31+/Annexin V+ microparticles correlate with cardiovascular outcomes. European Heart Journal, 32(16), 2034–2041. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subra C, Grand D, Laulagnier K, Stella A, Lambeau G, Paillasse M, et al. (2010). Exosomes account for vesicle-mediated transcellular transport of activatable phospholipases and prostaglandins. Journal of Lipid Research, 51(8), 2105–2120. 10.1194/jlr.M003657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovic K, Dhaunchak AS, Goncalves JT, Wenzel D, Schneider A, Bunt G, et al. (2006). Neuron to glia signaling triggers myelin membrane exocytosis from endosomal storage sites. The Journal of Cell Biology, 172(6), 937–948. 10.1083/jcb.200509022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingtdeux V, Hamdane M, Loyens A, Gele P, Drobeck H, Begard S, et al. (2007). Alkalizing drugs induce accumulation of amyloid precursor protein by-products in luminal vesicles of multivesicular bodies. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 282(25), 18197–18205. 10.1074/jbc.M609475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DM, Pevsner J, Scullion MA, Vaughn M, & Kaplan J (2000). Syntaxin 7 and VAMP-7 are soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors required for late endosome-lysosome and homotypic lysosome fusion in alveolar macrophages. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 11(7), 2327–2333. 10.1091/mbc.11.7.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei YM, Li X, Xu M, Abais JM, Chen Y, Riebling CR, et al. (2013). Enhancement of autophagy by simvastatin through inhibition of Rac1-mTOR signaling pathway in coronary arterial myocytes. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry, 31(6), 925–937. 10.1159/000350111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Li XX, Xiong J, Xia M, Gulbins E, Zhang Y, et al. (2013). Regulation of autophagic flux by dynein-mediated autophagosomes trafficking in mouse coronary arterial myocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1833(12), 3228–3236. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X, Bhat OM, Lohner H, Zhang Y, & Li PL (2019). Endothelial acid ceramidase in exosome-mediated release of NLRP3 inflammasome products during hyperglycemia: Evidence from endothelium-specific deletion of Asah1 gene. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 1864(12), 158532. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.158532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Jin S, Yi F, & Li PL (2009). TRP-ML1 functions as a lysosomal NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ release channel in coronary arterial myocytes. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 13(9B), 3174–3185. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, & Li PL (2007). Reconstitution and characterization of a nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)-sensitive Ca2+ release channel from liver lysosomes of rats. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 282(35), 25259–25269. 10.1074/jbc.M701614200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Xia M, & Li PL (2010). Lysosome-dependent Ca(2+) release response to Fas activation in coronary arterial myocytes through NAADP: Evidence from CD38 gene knockouts. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology, 298(5), C1209–C1216. 10.1152/ajpcell.00533.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Zhang G, Zhang AY, Koeberl MJ, Wallander E, & Li PL (2006). Production of NAADP and its role in Ca2+ mobilization associated with lysosomes in coronary arterial myocytes. American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 291(1), H274–H282. 10.1152/ajpheart.01064.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]