Abstract

Research on adults’ self-reported attachment styles, investigated mostly in social and personality psychology, has rarely been bridged with research on parenting, studied mostly in developmental psychology. We proposed that parents’ attachment insecurity (avoidance and anxiety) has an indirect association with their power-assertive control, mediated through their negative representations, or Internal Working Models (IWM) of the child. In 200 community families from a Midwestern state (mothers, fathers, and children), we collected multi-method, parallel data for mother- and father-child relationships. When children were infants, parents completed self-reports of their own attachment styles. When children were toddlers, we assessed parents’ IWMs of the child in an interview and observed parental power-assertive control in structured, naturalistic discipline contexts in the laboratory. Mothers’ avoidance showed a unique association with their IWM of their child. Consequently, there was an indirect association from the mother’s avoidance to negative IWM to power-assertive control. Mothers’ anxiety was associated directly with more power-assertive control. Fathers’ avoidance and anxiety were also associated with their IWMs, but there were no unique associations, and the impact on parenting was limited. Forging a rapprochement between social and personality research on adults’ attachment and developmental research on parenting, this work elucidates a potential mechanism of the intergenerational transmission of adaptive and maladaptive parenting in families.

Keywords: Adult attachment styles, Five-Minute Speech Sample, Internal Working Model, parenting, power-assertive control

For several decades, Bowlby’s (1969/1982) attachment theory has remained one of the most heuristically fertile, influential, and productive conceptual frameworks, informing not only the study of children’s socio-emotional development, but also the study of parental caregiving (Jones et al., 2015; Sroufe, 2016). Parents’ attachment organization, often seen as originating in their own early relationship experiences, has been considered a powerful force that shapes the caregiving of their own young children. In developmental psychology and psychopathology, parents’ attachment – referred to as “state of mind regarding attachment” – has been mostly assessed using Adult Attachment Interview. An impressive body of research, matured to the point of generating multiple systematic and meta-analytic reviews (Feeney & Woodhouse, 2016; van IJzendoorn, 1995; Putallaz et al., 1998), has demonstrated meaningful links between parents’ attachment and their parenting behavior, with findings mostly supporting Bowlby’s theory. Of note, overwhelming majority of those studies have examined the caregiving qualities linked to children’s safe haven and secure base, such as responsiveness, emotional availability, sensitivity, or warmth; very few have investigated control, another key parenting quality.

A more recent, but vigorously growing body of research on adults’ attachment has emerged in social and personality psychology (Crowell et al., 2016; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Although also inspired by Bowlby’s theory, that research reflects the methodological and conceptual foci typical to those disciplines. Consequently, adults’ attachment – referred to as “attachment styles” – has been typically measured with self-reports. Although adults’ self-reported attachment styles have been considered mostly in the context of romantic relationships, research on their implications for other social relationships and roles, including parenting, has been growing.

Specifically, family researchers have been increasingly interested in the intergenerational transmission of parenting and psychopathology (Kerr & Capaldi, 2019), with adult attachment as a key mechanism. Adult attachment style emerges, in part, in the context of one’s own early caregiving experiences (Fraley et al., 2013; Haydon et al., 2012). Adults who experienced insensitive, unresponsive parenting and parental unavailability tend to develop insecure attachment styles (Fraley et al., 2013; Haydon et al., 2012), which may impact their functioning in the family and lead to negative parenting behaviors.

In an excellent recent review, Jones, Cassidy, and Shaver (2015) emphasized the importance of research that integrates self-reported parental attachment styles with observational – preferably longitudinal – research on parenting. Having reviewed the extant studies, they outlined future research directions critical for elucidating and advancing our understanding of the implications of parents’ self-reported attachment styles on their parenting. They called for studies that go beyond the main effects and examine mediation or moderation models. They further argued for including parents’ emotions and cognitions, including internal representations of the child, as potential mediators between self-reported attachment and observed parenting behavior. They also pointed out that few, if any observational research had included fathers, with most studies focused on mothers.

We would also add another important goal for future research: The need to address an asymmetry in the studied dimensions of parenting. As mentioned earlier, research on links between parents’ attachment and their caregiving focuses almost exclusively on behaviors related to children’s safe haven and secure base. Relatively few studies of parents’ attachment and their parenting have examined control and discipline. Those studies have typically depicted secure, or autonomous parents as relying on more adaptive discipline than insecure parents (e.g., Adam et al., 2004; Lo et al., 2019; Verschueren et al., 2006), although Negrão et al. (2016) found that maternal security was associated with psychological control in a small sample of high-risk mothers. Jones et al. (2015) reported only a handful of studies that had examined the relations between self-reported attachment styles and parental control and discipline, typically also self-reported. Findings from these studies are mixed and inconclusive. Several studies found that parents who reported more insecurity (avoidance and/or anxiety) engaged in more harsh parenting (e.g., Berlin et al., 2011; Cowan et al., 2019; Coyl et al., 2010; Millings et al., 2013), but some studies failed to find a relation (Kilmann et al., 2009), and in some cases, the findings changed when family-level variables, such as social support, were included (Coyl et al., 2010). The mixed nature of the findings may be due to the diversity of attachment and parenting measures, complex effects of the family system’s dimensions (e.g., inter-parental relationship) included in some studies but not the others, and cultural and socioeconomic differences among the samples.

The relative dearth of research on control and discipline in attachment literature is unfortunate, particularly with regard to early parenting. The beginning of the second year marks the onset of parental demands, requests, and prohibitions, with the parent and child navigating the rapidly emergent, often stressful, affectively charged, and highly salient issues of compliance, autonomy, and resistance (Kuczynski & De Mol, 2015; Sroufe, 2016). Those processes likely have very distinct dynamics in parent-child relationships that differ in their attachment histories (Kochanska et al., 2019). Already classic research on attachment, early control, and compliance revealed that in secure dyads, compared to insecure, mothers showed less interference, were gentler, and children were more compliant (Londerville & Main, 1981).

In the current work, we draw from an ongoing longitudinal investigation, Children and Parents Study (CAPS). CAPS, informed by the attachment theory and socialization research frameworks, presents a unique opportunity to integrate an investigation of adults’ self-reported attachment, their representations of their children, and their parenting styles. CAPS involves a large group of community parents and children, who entered the study when children were infants. Multiple measures (self-reports, interviews, observations) target parents’ personality traits, including their self-reported attachment styles and qualities of parenting. Parents’ internal representations, or Internal Working Models (IWMs) of the child, are of special interest as one of the key mechanisms that guide parenting.

We propose a model of associations between parents’ self-reported attachment styles and their control behavior in discipline interactions with their toddlers. Specifically, we propose an indirect association between mothers’ and fathers’ insecure attachment, self-reported when children were infants, and power-assertive control observed at toddler age, with the parent’s negative IWM of the child hypothesized as the linking mechanism.

Studies of adult attachment styles have utilized various measures, with some assessing dichotomous security/insecurity categories and some focused on continuous dimensions of insecure attachment (avoidance and anxiety; Jones et al., 2015). Avoidance and anxiety are often positively correlated among adults (Fraley et al., 2013) and thus are sometimes combined into one dimension of insecurity, with higher scores on both dimensions reflecting lower security and higher insecurity (Fraley, 2012). However, studies on parental attachment sometimes have revealed different effects of avoidance and anxiety, although the findings are mixed (Jones et al., 2015). Theoretically, avoidance has been considered a “deactivational” type of attachment, in which one dismisses the need for intimacy and avoids close relationships, whereas anxiety has been linked to “hyperactivational”, poorly regulated strategies that may include seeking or forcing extra confirmation from relationships (Berant et al., 2005). These differences likely would influence how the parent mentalizes and responds to the child’s behavior. For instance, compared with anxiety, avoidance may be more closely related to parents’ lack of interest in and biased mentalization of their children because avoidant parents tend to become detached from relationships. As such, in this study, we measured avoidance and anxiety as two distinct dimensions and examined their similarities and differences in terms of their associations with IWM and parenting.

To assess power-assertive control, we observed mothers and fathers interacting with their young toddlers in naturalistic, structured contexts in the laboratory, designed to be “saturated” with discipline and control issues typical of their daily lives. To assess parents’ IWMs of the child, we drew from a large and rapidly growing body of literature on multiple aspects of parents’ internal representations that account for the links between the parent’s attachment and their caregiving (Dykas et al., 2011; Fonagy & Target, 1997; van IJzendoorn, 1995; Katznelson, 2014; Kerr et al., 2019; Kochanska et al., 2019; Luyten et al., 2017; McMahon & Bernier, 2017; Meins, 1999; Sharp & Fonagy, 2008; Slade, 2005; Rostad & Whitaker, 2016; Verhage et al., 2016). Parents’ IWMs have been conceptualized from various perspectives – as reflective functioning, mind-mindedness, mentalization, attributions, or relational schemas – and assessed as explicit or implicit constructs, emphasizing both cognitive and affective components.

We measured parents’ IWMs of the child using the Five-Minute Speech Sample (FMSS) interview, a well-established and increasingly broadly used paradigm in developmental research (see comprehensive reviews, Sher-Censor, 2015; Weston et al., 2017). FMSS captures two dimensions of the parent’s narrative: criticism and warmth. The coding targets the implicit and explicit aspects of the cognitive and emotional content, thus aligning well with the construct of IWMs as informed by attachment theory. Because of our interest in negative, hostile IWMs as linking parents’ insecurity to their power assertion, we focused on parental criticism, or a negative relational schema, an implicit negative attitude, which specifically captures a negative representation of the child and the parent-child relationship (Bullock & Dishion, 2007; Greenlee et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2013).

To summarize, in the proposed study, parents’ self-reported attachment insecurity, avoidance and anxiety, assessed when children were infants, were modeled as the predictors. Parents’ power-assertive control, also observed at toddler age, was the outcome variable. All data were parallel for mother-child and father-child dyads. Parents’ negative IWM of the child, assessed in the FMSS interview at toddler age, was the proposed mechanism accounting for the link between parents’ attachment and their power-assertive control.

Method

Participants

Two-parent community families with infants (N = 200, 96 girls, born in 2017 and 2018) volunteered for CAPS. Statistical literature has suggested that the sample size is sufficient for achieving > .8 power for detecting indirect effects that are constituted of small-to-medium sized paths (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). The families came from a Midwestern state in US, an area that included a college town, small cities, and rural communities. They responded to broadly distributed flyers, posters, social media, and mass emails. To be eligible, both parents of a biological, typically developing infant had to be willing to participate and speak English during sessions, and the family had to plan to stay in the area for the next five years.

The families represented a range of educational background: 14.5% of mothers and 24.0% of fathers had no more than a high school education, 46.5% of mothers and 43.5% of fathers had an associate or college degree, and 39.0% of mothers and 32.5% of fathers had a postgraduate education. The median household income was $85,000 (SD = $44,530, range = $4,000 to $320,000). In terms of race, 88.5% of mothers and 88.5% of fathers were White, 1.5% of mothers and 3.0% of fathers African American, 5.5% of mothers and 3.5% of fathers Asian, and 4.5% of mothers and 3.5% fathers multiracial. Three (1.5%) fathers did not disclose their race. In terms of ethnicity, 4.5% of mothers and 1.5% of fathers identified as Latino, with the rest identifying as non-Latino (95.0% of mothers and 98.5% of fathers) or not reporting their ethnicity (0.5% of mothers). When asked to describe the child’s race, parents identified 82.5% children as White, 2.5% as African American, 3.0% as Asian, and 10.5% as multiracial. Three (1.5%) families did not disclose the race of the child. Eleven (5.5%) of the children were identified as Latino, 94.0% as non-Latino, or were missing ethnicity information (0.5%). In 20% of the families, at least one parent was non-White or Latino. Demographic data were entered using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Iowa (Harris, Taylor, Minor et al., 2019). The University of Iowa IRB approved the study (CAPS, 201701705); the parents completed informed consents at the entry to the study. We report how we determined our sample size and all measures in the study. No data were excluded from the study. Study materials and further information about this study is available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Overview of Design

The data reported in this article came from the assessments conducted when children were 7–9 months old (parents’ self-reported attachment) and when they were 15–17 months old (parents’ negative IWMs of the child and their power-assertive control). At 15–17 months, each mother-child dyad and each father-child dyad participated in a 2–2.5-hour, carefully scripted laboratory session, conducted by a female experimenter (E). The session encompassed a broad range of paradigms and contexts (play, snack, chores, free time, standard tasks, etc.). The laboratory includes a naturalistically furnished Living Room and a sparsely furnished Play Room. In the Living Room, there is a low table with extremely attractive toys and objects. E designated those toys as off limits to the child at the outset and asked the parent to enforce the prohibition throughout the session. At the end of the session, E conducted FMSS interview with the parent.

The sessions were videotaped through one-way mirror for later coding. Two separate teams, comprised of professional research assistants, a graduate student, and several undergraduate students coded behavioral data on control in two contexts (toy cleanup and control in naturalistic interactions, see below). The training of the coders involved first, working together to achieve consensus, and then coding independently between 15% and 20% of cases sampled for reliability. After reliability was achieved, the coders realigned every few months, coding together several cases, to prevent observers’ drift. Kappas, weighted kappas, and intra-class correlations (ICCs) were used to compute reliability, as appropriate.

Measures

Parents’ Self-reported Attachment (In)Security to Their Own Parents

Parents completed the Experiences in Close Relationships—Relationship Structures Questionnaire (ECR-RS; Fraley et al., 2011), a well-established method for assessing attachment orientation across various relationships. Each mother and father responded to 9 items that describe their relationships with their own mother (or mother-like figure) and own father (or father-like figure). Six items assess avoidance (e.g.,” I don’t feel comfortable opening up to this person”) and three items assess anxiety (e.g., “I’m afraid that this person may abandon me”). For each item, parents indicated the extent to which they agreed with the item (1= strongly disagree; 7= strongly agree). Cronbach’s alphas indicated that the avoidance and anxiety scales were highly internally coherent (listed for own mother figure first and own father figure second). For avoidance, data were as follows: mothers, .93, .93; fathers, .92, .92. For anxiety, data were as follows: mothers, .84, .85; fathers, .93, .94.

Parents’ avoidance and anxiety scores with their own mother and father correlated significantly. For mothers, the correlation for avoidance (across own mother/father) was r(190) = .40, p < .001, and for anxiety, r(190) = .49, p < .001. The respective correlations for the fathers were r(190) = .44, p < .001, and for anxiety, r(190) = .49, p < .001. Therefore, for each parent, we averaged the scores across their own mother and father to create two composites, one for avoidance toward own parents and one for anxiety toward own parents.

Parents’ Negative Internal Working Model (IWM) of the Child

Paradigm and coding.

Having established a good rapport with the parent, E conducted a brief interview with them (FMSS) when the child was not in the room. E asked the parent to talk about the child and their relationship with the child for 5 minutes, and then focused quietly on her paperwork and provided no additional prompts. The parent’s speech was audio-recorded.

The recorded FMSS interviews were coded off-site by a professional coder, with Dr. Bullock serving as the master coder, using Family Affective Attitudes Rating Scale (FAARS; Bullock & Dishion, 2007; Bullock et al., 2005). FAARS captures two dimensions of the parent’s narrative: criticism and warmth. We focused on parental criticism, or a negative relational schema, an implicit negative representation of the child and the parent-child relationship (Bullock & Dishion, 2007; Greenlee et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2013). Criticism is based on 6 items (parent is critical of child behavior or traits, comments on the negative relationship with child, uses negative humor or sarcasm, assumes or attributes negative intentions to child, reports conflict with child). Coder rates each item on a scale from 1 to 9, with 1 = no evidence during the interview, to 9 = clear, multiple examples. We followed the standard reliability instructions (Bullock et al., 2005), broadly adopted in published research. Those instructions specify that ratings within 2 points are considered an agreement; 80% agreement is the standard required for successful completion of training. The agreement in this study was 96%; ICC was .75.

Data aggregation.

We standardized and averaged the items to obtain the composite of negative IWM of the child for each parent. One item (“reporting of conflict with/anger or hostility toward the child,” which captures severe conflicts and hostility) exhibited high skewness and kurtosis for both parents (> 95% of mothers and fathers had a rating of 1), lowered internal consistency and was therefore dropped. Cronbach’s alphas for the 5 remaining items were modest but acceptable: .59 for mothers and .52 for fathers. Item-total correlations ranged from .23 to .41 for mothers and from .21 to .33 for fathers.

Parents’ Power-Assertive Control

Paradigms and coding.

Parents’ power-assertive control was coded in naturalistic and carefully scripted contexts, “saturated” with discipline issues typical for the toddler age. One context involved an interaction focused on a toy cleanup (10 min). The parent asked the child to clean up toys after play and put them in a large basket. The other context involved naturalistic, but scripted interactions (15 minutes, encompassing introduction to the Living Room, including the initial prohibition pertaining to the prohibited attractive objects, free time, and snack prohibition, when the parent placed snacks, drinks, plates, and napkins on a table in preparation for a snack, and asked the child to wait for several minutes). Note that in contrast to the cleanup, parental control could involve multiple issues (e.g., the prohibition to touch the off-limits toys, the directive to delay the snack, etc.).

Coders rated parental control for each 30-sec segment in the cleanup and 20-sec segment in naturalistic interactions, using a rating that reflected the increasing amount of power or pressure. The codes ranged from 1 = no control (no interaction, purely social exchange, play), to 2 = gentle guidance (gentle, subtle, polite, pleasant control), to 3 = control (firm, no-nonsense, relatively assertive control), to 4 = power-assertive, negative, harsh control (control delivered in forceful, impatient, threatening, angry manner). The detailed conventions clearly specified verbal, affective, and physical markers of each rating, based on extensive past research (e.g., Kochanska et al., 2012), to capture even subtle fluctuations in the amount of parental pressure. Consider the following 2 minutes (6 segments) as a fictional example of the cleanup context. Segment 1. Mother: “Ok, honey, please put these toys in the basket” (gentle guidance). Segment 2. Mother: “This lawnmower is just like ours at home!” (no mention of cleanup as the child is playing with the toy lawnmower; no control). Segment 3. Mother (firmly): “But now we need to put it in the basket; now, please” (placing basket decisively in front of child, turning child face for attention; control). Segment 4. Mother (in a raised, somewhat angry voice): “No, no – I told you – no more play – it needs to go in there” (takes the toy forcibly away from child; power-assertive control). Segment 5. Mother: “Ok, now let’s put away these animals – good job!” (gentle guidance). Segment 6. Mother: “No sweetie, we are not playing anymore” (chanting the popular song, “cleanup, cleanup, everybody everywhere”; gentle guidance).

Reliability, weighted kappas, were .65 and .67 for the cleanup and .85 and .86 for the naturalistic interaction. Two different teams coded the two contexts; each team included a master coder and two additional coders.

Data aggregation.

For each context – the cleanup and naturalistic interactions– all instances of each code were added, and then weighed to reflect the amount of power for the whole context, such that the tally of “no control” was multiplied by 1, the tally of “gentle guidance” by 2, the tally of “control” by 3, and the tally of “power-assertive control” by 4. Those figures were then added, divided by the number of coded segments, and standardized. The scores correlated across the observed contexts (cleanup and naturalistic interaction): for mothers, r(191) = .38, p < .001, and for fathers, r(184) = .24, p = .001. Consequently, the (standardized) scores were averaged into one overall power-assertive control score for each parent. The composite of power-assertive control has demonstrated good construct validity in previous studies, with robust positive correlations with child difficulty and negative correlations with positive forms of parenting (e.g., Kochanska et al., 2012).

Child Defiance (Covariate)

Paradigms and coding.

We observed children’s defiance with each parent in the same contexts, in the same segments as parents’ control. It was defined as overt opposition or noncompliance, accompanied by poorly controlled anger (e.g., fussing, crying, whining, arching back, throwing toys, kicking, temper tantrum, deliberately and angrily taking toys out of the basket). Reliability, kappas, were .71 and .73 for toy cleanup and 82 and .84 for naturalistic interaction.

Data aggregation.

For each context, all instances of defiance were tallied and divided by the number of segments when parental control was present. Children’s defiance scores correlated across the toy cleanup and the naturalistic interactions; for the child with the mother, r(191) = .35, p < .001, and for the child with the father, r(184) = .24, p = .001. Consequently, they were standardized and aggregated into an overall defiance score for the child with each parent. The descriptive data and Ns for all constructs are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data for All Constructs

| Mother-Child Dyad | Father-Child Dyad | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Construct | M | SD | N | M | SD | N |

| Assessment at 7–9 Months | ||||||

| Parent Attachment | ||||||

| Avoidance | 2.99 | 1.42 | 197 | 3.26 | 1.31 | 198 |

| Anxiety | 1.59 | 0.9 8 | 197 | 1.65 | 1.00 | 198 |

| Assessment at 15–17 Months | ||||||

| Parent Negative IWM of Childa | 0.00 | 0.61 | 194 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 186 |

| Parent Power-Assertive Control | ||||||

| Cleanup | 2.20 | 0.27 | 193 | 2.36 | 0.35 | 186 |

| Naturalistic Interaction | 1.78 | 0.31 | 193 | 1.73 | 0.28 | 186 |

| Overall Power-Assertive Controlb | 0.00 | 0.83 | 193 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 186 |

| Child Defiance | ||||||

| Cleanup | 0.11 | 0.16 | 193 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 186 |

| Naturalistic Interaction | 0.16 | 0.17 | 193 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 186 |

| Overall Defianceb | 0.00 | 0.82 | 193 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 186 |

Notes.

Average of 5 standardized items.

Average of standardized scores across cleanup and naturalistic interaction. IWM = Internal Working Model.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We first examined the correlations among the constructs, separately for mother- and father-child dyads and across the dyads (Table 2). In both mother- and father-child dyads, parents’ avoidant and anxious attachments to their own parents were associated with their more negative IWMs of the child. Parents with more negative IWMs relied on more power-assertive control. Across parents, mothers’ attachment to their own parents was not related to fathers’ attachment. Similarly, mothers’ and fathers’ IWMs of their child were not intercorrelated. However, mothers’ and fathers’ power-assertive control scores were correlated positively. In addition, the parent’s power-assertive control correlated positively with the child’s defiance.

Table 2.

Correlations among all Constructs

| Parent Avoidant Attachment to Own Parents | Parent Anxious Attachment to Own Parents | Parent Negative IWM of Child | Parent Power-Assertive Control | Child Defiance to Parent | Family Income | Parental Education | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Avoidant Attachment to Own Parents | −.01 | .60**** | .24**** | .01 | .06 | −.23*** | −.17** |

| Parent Anxious Attachment to Own Parents | .52**** | .08 | .17** | .14+ | .09 | −.22*** | −.16** |

| Parent Negative IWM of Child | .17** | .20*** | .13+ | .22*** | .17** | −.11 | −.09 |

| Parent Power-Assertive Control | .07 | .06 | .16* | .35**** | .28**** | −.11 | −.21*** |

| Child Defiance to Parent | .04 | −.02 | .06 | .27**** | .37**** | −.06 | −.08 |

| Family Income a | .00 | −.09 | −.02 | −.07 | −.06 | – | .38**** |

| Parental Education b | .01 | −.01 | .05 | −.16* | −.08 | .20*** | .41**** |

Notes. The values above the diagonal are for mothers and children, the values below the diagonal are for fathers and children, and the values on the diagonal are across mother- and father-child dyads. IWM = Internal Working Model.

Rated on a scale of 1 to 8.

Rated on a scale of 1 to 5.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .025.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We then inspected the relations between demographic variables and the variables of interest. Parents used more power-assertive control toward boys than girls, t(188.42) = 4.15, p < .001, and t(184) = 2.52, p = .013, for mothers and fathers, respectively. Boys also displayed more defiance toward their mothers than girls, t(177.28) = 2.44, p = .017. In addition, parents’ educational levels correlated negatively with their power-assertive control. Mothers’ educational levels also correlated negatively with their attachment insecurity to their parents. Further, family income related negatively with mothers’ attachment insecurity.

We also compared the means of the constructs for mother- and father-child dyads (using non-standardized scores to enable us to detect potential differences). Compared to fathers, mothers had higher scores on negative IWMs of the child, t(185) = 3.22, p = .001, used more power assertion in naturalistic interactions, t(185) = 2.01, p = .046, but less power assertion in toy cleanups, t(185) = −5.36, p < .001.

Next, we inspected the missing data. Families that participated at both times and those that participated only at 7–9 months did not differ in their characteristics, with one exception: Compared with mothers who participated at both times, mothers who did not return at 15–17 months reported lower avoidant and anxious attachments to their own parents, t(6.87) = 4.71 and t(190) = 8.40, respectively, ps < .01. Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test indicated that data were missing completely at random, χ2(50) = 48.17, p = .547.

Indirect Effect Models for Mother-Child and Father-Child Dyads

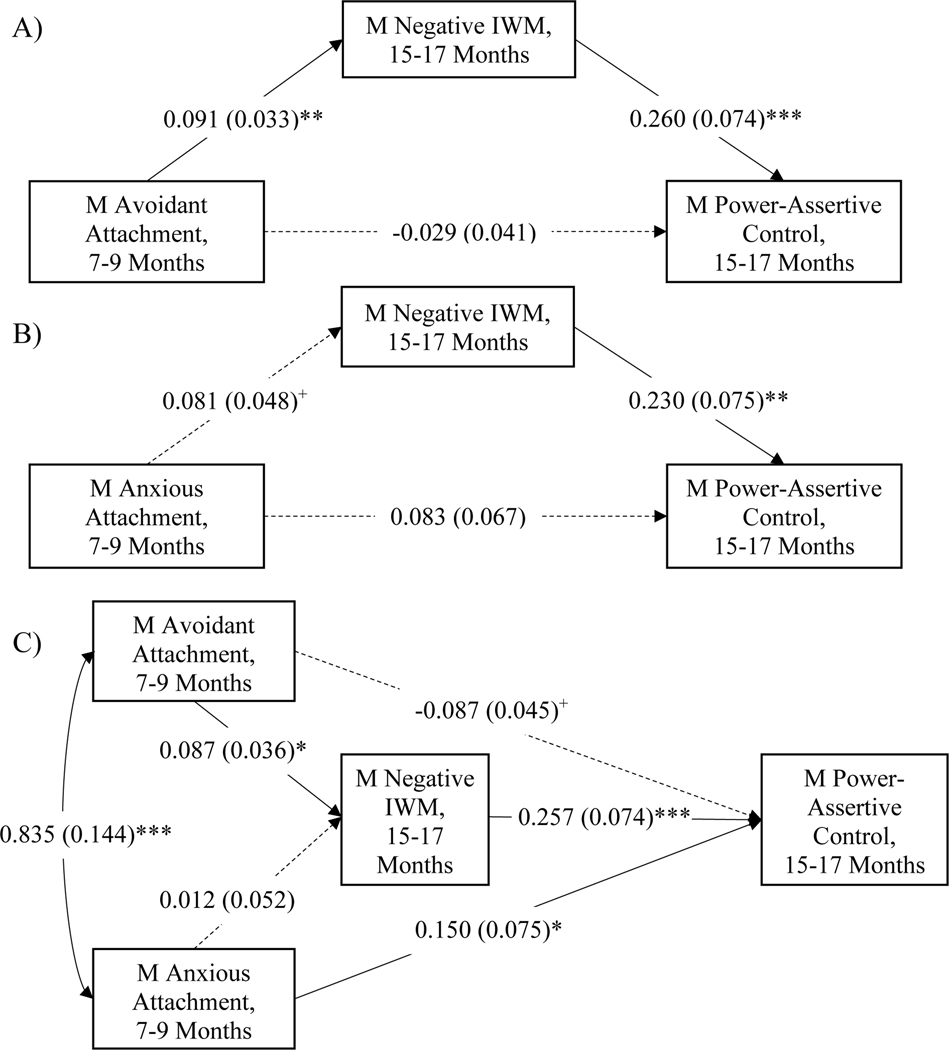

We examined the proposed indirect effects separately for mother– and father–child dyads. Specifically, we modeled parents’ attachment insecurity reported at 7–9 months as the predictor, parental negative IWMs of the child at 15–17 months as the mediator, and observed power-assertive control at 15–17 months as the outcome variable. To examine the contributions of each type of attachment insecurity (avoidance, anxiety), we inspected three sets of models. In the first two models, we separately examined the effects of parents’ avoidant and anxious attachment to their own parents, respectively. In the third model, we included both avoidant and anxious attachments to examine their unique contributions to IWM and parenting (see Figures 1 and 2 for model configuration). We included child gender, the corresponding parent’s educational level, family income, and the child’s defiance toward the parent as covariates in the models, as suggested by the preliminary analysis.

Figure 1.

The indirect effects from the predictor, the mother’s attachment insecurity to their own parents at 7–9 months, to the mediator, the mother’s negative IWM at 15–17 months, to the outcome, the mother’s power-assertive control at 15–17 months. Panel A: Mother’s avoidant attachment as the sole predictor. Panel B: Mother’s anxious attachment as the sole predictor. Panel C: Both avoidant and anxious attachment are included as predictors. Although not depicted, the child’s gender, the mother’s educational level, family income, and the child’s defiance toward the mother were included as covariates for both the mediator and the outcome. Solid lines represent significant effects and dashed lines represent nonsignificant effects. Unstandardized coefficients are reported. Standard errors are in the parentheses. M = Mother. IWM = Internal Working Model. +p < .10. *p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Figure 2.

The indirect effects from the predictor, the father’s attachment insecurity to their own parents at 7–9 months, to the mediator, the father’s negative IWM at 15–17 months, to the outcome, the father’s power-assertive control at 15–17 months. Panel A: Father’s avoidant attachment as the sole predictor. Panel B: Father’s anxious attachment as the sole predictor. Panel C: Both avoidant and anxious attachment are included as predictors. Although not depicted, the child’s gender, the father’s educational level, family income, and the child’s defiance toward the father were included as covariates for both the mediator and the outcome. Solid lines represent significant effects and dashed lines represent nonsignificant effects. Unstandardized coefficients are reported. Standard errors are in the parentheses. F = Father. IWM = Internal Working Model. +p < .10. *p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

We examined the indirect effects in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2020), using the codes adapted from Stride et al. (2015), which follows the approach of the PROCESS framework (Hayes, 2018) and allows for unbiased missing data treatment using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method. To account for the non-normal sampling distribution of indirect associations and provide accurate estimations and maximized power for the moderate sample size, we used the nonparametric resampling method (percentile bootstrap; 10,000 resamples) to derive the 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the indirect effect.

Mother-child dyads.

In mother-child dyads (models depicted in Figure 1), mothers’ avoidant attachment to their own parents, when analyzed alone (Figure 1A), was associated positively with their negative IWM of their child. Mothers’ negative IWM, in turn, was associated positively with their power-assertive control. Consequently, the indirect association from avoidance to IWM to power-assertive control was present, B = 0.024, SE = 0.011, bootstrapped 95% CI [0.005, 0.047].

However, mothers’ anxious attachment, when analyzed alone (Figure 1B), was not associated significantly with their negative IWM of their child. Mothers’ negative IWM was associated positively with their power-assertive control. The indirect association from anxiety to IWM to power-assertive control was absent, B = 0.019, SE = 0.012, 95% CI [−0.001, 0.047].

When we included mothers’ avoidant and anxious attachments in the same model (Figure 1C), only avoidance, but not anxiety, was associated with their negative IWM of the child. Mothers’ negative IWM was associated positively with their power-assertive control. Consequently, the indirect association from mothers’ avoidance to IWM to power-assertive control was present, B = 0.022, SE = 0.012, 95% CI [0.003, 0.048], but the indirect association from anxiety to IWM to power-assertive control was not, B = 0.003, SE = 0.014, 95% CI [−0.024, 0.032]. Instead, mothers’ anxiety was associated directly with their power-assertive control.

Father-child dyads.

In father-child dyads (models depicted in Figure 2), fathers’ avoidant attachment, when analyzed alone (Figure 2A), was associated positively with their negative IWM of their child. A similar association with negative IWM was found for fathers’ anxious attachment to their own parents (Figure 2B). In both models, fathers’ negative IWM of their child was not associated with their power-assertive control. As such, the indirect associations from fathers’ attachment to IWM to power-assertive control were not supported.

Interestingly, when we included fathers’ avoidant and anxious attachments in the same model (Figure 2C), their unique associations with their negative IWM were not significant. The association between fathers’ IWM and power-assertive control remained nonsignificant. The indirect associations from fathers’ avoidant/anxious attachment to IWM to power-assertive control were absent, B = 0.008, SE = 0.009, 95% CI [−0.005, 0.031], and B = 0.017, SE = 0.016, 95% CI [−0.006, 0.055], respectively.

Discussion

Over the recent decades, research on relations between adults’ attachment and their parenting has grown exponentially in developmental psychology and psychopathology. Most of it, however, has relied on the AAI as the methodological approach to adult attachment. Only relatively recently, scholars have begun to bridge research in personality psychology that utilizes adults’ self-reports of attachment styles with research on parenting (Berlin et al., 2011; Cowan et al., 2019; Coyl et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2015), arguing that parental attachment security may impact their parenting through their internal representations, or IWMs, of their child (Cassidy et al., 2013; Dykas et al., 2011; Greenberg et al., 1993; van IJzendoorn, 1995; Jones et al., 2015; Luyten et al., 2017; Meins, 1999; Sharp & Fonagy, 2008). Aligning with this theoretical agenda, in the present study, we drew from rich short-term longitudinal data collected from both mother-child and father-child dyads using various robust measures (questionnaires, interviews, and behavioral observations) to inspect the pathways from parental attachment insecurity to their negative IWMs of their child to their power-assertive control.

The current work makes several contributions to the field. It serves the goal of forging bridges between attachment theory frameworks within developmental psychology and psychopathology and those in social and personality psychology. It informs our understanding of the contributions of adult attachment to individuals’ functioning in the key roles as parents.

For mothers, we found support for the proposed indirect effect through IWM. Mothers who reported more insecure attachment styles when the children were infants expressed more negative views – or the negative IWM – of the child and their relationship with the child at toddler age. In turn, their negative IWMs of the child were positively associated with their power-assertive control directed at their toddlers. These findings are consistent with the theoretical notion of IWMs’ role in bridging the association between parental attachment styles and parenting behavior (Dykas et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2015; Meins, 1999; Sroufe, 2016). When parents internalize and represent their own histories of insecure attachments from past and current relationships, they may apply a similar negative lens when they interpret their child’s behavior, which may, in turn, increase their reliance on power-assertive parenting.

However, such an indirect association was only present for avoidant attachment, but not anxious attachment. Theoretically, adults with high avoidant attachment scores tend to deactivate relationship-related emotions and avoid closeness (Borelli et al., 2017), which may limit their ability to develop close relationships with their children and to understand children’s mental states. Consistent with our findings, avoidant adults perceive parenting and parenthood as less enjoyable and satisfying, and have more difficulty identifying infants’ emotions; avoidance has also been associated with fewer parental references to providing a safe haven of safety and secure base for the child and less sense of one’s own availability to offer comfort to the child (“secure base script”; Borelli et al., 2017; Leerkes & Siepak, 2006). Interestingly, we also found a significant direct association between anxious attachment and maternal power-assertive control, not through IWM. This may be because anxious mothers have more difficulty regulating their negative emotions and tend to engage in more conflicts with their child (Selcuk et al., 2010).

For fathers, we found a partly similar pattern in that both their avoidant and anxious attachments with their own parents were associated with their negative IWMs of their children. Yet when we analyzed fathers’ avoidant and anxious attachments in the same model, neither of them produced significant unique effects. Because the avoidant and anxious dimensions of attachment tend to overlap, they may not always produce unique effects – at least, in the case of fathers in our study, what matters seems to be their general attachment insecurity, rather than the specific insecurity dimension. In addition, the associations between fathers’ IWMs of their children and their power-assertive control were only marginal, suggesting that fathers’ representation of the child, although related to the schema they developed through previous relationship history, may not translate into their power-assertive control. It is still possible, however, that fathers’ IWMs of the child may impact other aspects of their parenting, such as warmth, responsiveness, or intrusiveness, not examined in our analyses.

It is worth noting that although we were able to support the proposed indirect effects to some degree by demonstrating that insecure attachment history is associated with negative IWM of the child, which then may be associated with power-assertive parenting, the zero-order correlations between parents’ attachment styles and their power-assertive control were nonsignificant. The associations between attachment history and control can be complex, as control is a multidimensional construct. Power assertion is only one aspect of control; other dimensions include consistency, structuring, management of conflict, etc. For instance, insecure parents may also engage less when interacting with their children, or withdraw in the face of conflict, which may be negatively associated with their power-assertive control. In other words, it is possible that parents’ insecurity is associated with their dysfunctional control both positively though heightened power assertion and negatively through retreat, a pattern found in depressed mothers (Kochanska et al., 1987), resulting in an overall association of zero. Future studies should examine such possibilities by deploying more fine-grained and microscopic observations of parent-child control and discipline encounters.

Despite the complexities, we believe that the focus on parental control and discipline is a strength of this investigation. As discussed earlier, attachment-informed studies tend to focus on the parenting dimensions most pertinent to the attachment system: provision of secure base and safe haven. Consequently, the typical parenting measures include responsiveness, sensitivity, or emotional availability. This asymmetry has created a gap, as we often miss important parenting dimensions pertinent to control, highly salient in the toddler age and beyond (Sroufe, 2016).

Although this work makes useful contributions, it also has several limitations. The data on parents’ IWMs and their parenting were concurrent. Consequently, the inferences about potential causal associations are very limited and open to alternative interpretations. As of this writing, we are following up the CAPS families, and longitudinal data will be available in the future.

ECR-RS was the only measure of parents’ insecurity reported in this article. As Jones et al. (2015) persuasively argued, ideally, researchers would obtain multiple measures of parents’ attachment, particularly given the relatively limited concordance between ECR-RS and AAI (Roisman et al., 2007).

Internal coherence of the measure of parents’ negative IWMs of the child was relatively modest. This was likely caused by the children’s very young age (15–17 months). Most extant studies that have used parental FMSS and FAARS coding have involved older toddlers, preschoolers, youths in middle childhood, and adolescents.

Finally, our families were a typical low-risk community sample. At the entry to the study, all families included two parents, and all infants were typically developing. Mothers’ and fathers’ avoidance and anxiety were relatively low, and so were their scores on negative IWMs of the child. Their parenting was overall adaptive and skillful, and children were generally compliant and cooperative. Future studies should involve high-risk families. Furthermore, ethnic diversity was limited (although note that 20% of the families included a non-White parent).

Despite those limitations, this work elucidates important and not yet well understood implications of adults’ self-reported attachment styles on their parenting, and it proposes mechanisms that may account for those effects. In particular, we highlight the importance of parents’ secure attachment, as well as parental IWMs as one potential mechanism linking parental attachment to parenting. This focus dovetails with the emerging interest in interventions that target parents’ attachment security and representations of their children (Adkins et al., 2018; Jones et al., 2021; Suchman et al., 2017). Consequently, this research has implications for both basic research on attachment and caregiving and for translational research, promoting adaptive parenting through prevention and intervention.

Acknowledgments:

This work was funded by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant R01 HD091047 to Grazyna Kochanska), and additionally supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR002537). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank the entire Child Lab team for their contributions, Grace Bullock and Jenene Petersen for coding Five-Minute Speech Samples, and the participating families for their commitment to our research. This study was not preregistered and was not published elsewhere previously. Study materials and further information about this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request. No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adam EK, Gunnar MR, & Tanaka A. (2004). Adult attachment, parent emotion, and observed parenting behavior: Mediator and moderator models. Child Development, 75(1), 110–122. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00657.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkins T, Luyten P. & Fonagy P. (2018). Development and preliminary evaluation of family minds: A mentalization-based psychoeducation program for foster parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(8), 2519–2532. 10.1007/s10826-018-1080-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berant E, Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, & Segal Y. (2005). Rorschach correlates of self-reported attachment dimensions: Dynamic manifestations of hyperactivating and deactivating strategies. Journal of Personality Assessment, 84(1), 70–81. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8401_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Whiteside-Mansell L, Roggman LA, Green BL, Robinson J, & Spieker S. (2011). Testing maternal depression and attachment style as moderators of Early Head Start’s effects on parenting. Attachment & Human Development, 13, 49–67. 10.1080/14616734.2010.488122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borelli JL, Burkhart ML, Rasmussen HF, Brody R, & Sbarra DA (2017). Secure base script content explains the association between attachment avoidance and emotion-related constructs in parents of young children. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(2), 210–225. 10.1002/imhj.21632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1969/1982). Attachment and loss. (Vol. 1, 2nd ed.) New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, & Munholland KA (2008). Internal working models in attachment relationships: Elaborating a central construct in attachment theory. In Cassidy J. & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 102–130). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock B, & Dishion T. (2007). Family process and adolescent problem behavior: Integrating relationship narratives into understanding development and change. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(3), 396–407. 10.1097/chi.0b013e31802d0b27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock B, Schneiger A, & Dishion T. (2005). Manual for coding five-minute speech samples using the Family Affective Rating Scale (FAARS). Eugene, OR: Child and Family Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Jones JD, & Shaver PR (2013). Contributions of attachment theory and research: A framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development and Psychopathology, 25(42), 1415–1434. 10.1017/s0954579413000692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP, Pruett MK, & Pruett K. (2019). Fathers’ and mothers’ attachment styles, couple conflict, parenting quality, and children’s behavior problems: An intervention test of mediation. Attachment & Human Development, 21(5), 532–550. 10.1080/14616734.2019.1582600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyl DD, Newland LA, & Freeman H. (2010). Predicting preschoolers’ attachment security from parenting behaviours, parents’ attachment relationships and their use of social support. Early Child Development and Care, 180(4), 499–512. doi: 10.1080/03004430802090463 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell JA, Fraley RC, & Roisman GI (2016). Measurement of individual differences in adult attachment. In Cassidy J. & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 598–635). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dykas MJ, Ehrlich KB, & Cassidy J. (2011). Links between attachment and social information processing: Examination of intergenerational processes. In Benson JB (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 40, pp. 51–94). San Diego, CA: Elsevier. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386491-8.00002-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney BC, & Woodhouse SS (2016). Caregiving. In Cassidy J. & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 827–851). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, & Target M. (1997). Attachment and reflective function: their role in selforganization. Development and Psychopathology, 9(4), 679–700. 10.1017/s0954579497001399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC (2012). Information on the experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (ECR-R) Adult Attachment Questionnaire. Retrieved December 12, 2020 from http://labs.psychology.illinois.edu/~rcfraley/measures/ecrr.htm [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Heffernan ME, Vicary AM, & Brumbaugh CC (2011). The experiences in close relationships—Relationship Structures Questionnaire: A method for assessing attachment orientations across relationships. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 615–625. 10.1037/a0022898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Roisman GI, Booth-LaForce C, Owen MT, & Holland AS (2013). Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(5), 817–838. doi: 10.1037/a0031435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, & MacKinnon DP (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Speltz ML, & Deklyen M. (1993). The role of attachment in the early development of disruptive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology, 5(1–2), 191–213. doi: 10.1017/s095457940000434x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee JL, Winter MA, Everhart RS, & Fiese B. (2019). Parents’ child-related schemas: Associations with children’s asthma and mental health. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(3), 270–279. 10.1037/fam0000494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, & Duda SN (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon KC, Collins WA, Salvatore JE, Simpson JA, & Roisman GI (2012). Shared and distinctive origins and correlates of adult attachment representations: The developmental organization of romantic functioning. Child Development, 83(5), 1689–1702. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01801.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn M. (1995). Adult attachment representations, parental responsiveness, and infant attachment: A meta-analysis on the predictive validity of the adult attachment interview. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 387–403. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Cassidy J, & Shaver PR (2015). Parents’ self-reported attachment styles: A review of links with parenting behaviors, emotions, and cognitions. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(1), 44–76. 10.1177/1088868314541858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Stern JA, Fitter MH, Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, & Cassidy J. (2021). Attachment and attitudes toward children: effects of security priming in parents and nonparents. Attachment & Human Development, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2021.1881983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katznelson H. (2014). Reflective functioning: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(2), 107–117. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DCR, & Capaldi DM (2019). Intergenerational transmission of parenting. In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Being and becoming a parent (pp. 443–481). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. 10.4324/9780429433214-13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr ML, Buttitta KV, Smiley PA, Rasmussen HF, & Borelli JL (2019). Mothers’ real-time emotion as a function of attachment and proximity to their children. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(5), 575–585. 10.1037/fam0000515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmann PR, Vendemia JC, Parnell MM, & Urbaniak GC (2009). Parent characteristics linked with daughters’ attachment styles. Adolescence, 44(175), 557–568. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A212105875/HRCA?u=anon~175e0ad2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Boldt LJ, & Goffin KC (2019). Early relational experience: A foundation for the unfolding dynamics of parent-child socialization. Child Development Perspectives, 13(1), 41–47. DOI: 10.1111/cdep.12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Kim S, & Koenig Nordling J. (2012). Challenging circumstances moderate the links between mothers’ personality traits and their parenting in low-income families with young children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(6), 1040–1049. 10.1037/a0030386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Kuczynski L, Radke-Yarrow M, & Darby Welsh J. (1987). Resolutions of control episodes between well and affectively ill mothers and their young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 15(3), 441–456. DOI: 10.1007/BF00916460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski L, & de Mol J. (2015). Dialectical models of socialization. In Lerner RM (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (pp. 1–46). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, & Siepak KJ (2006). Attachment linked predictors of women’s emotional and cognitive responses to infant distress. Attachment & Human Development, 8(01), 11–32. 10.1080/14616730600594450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo CK, Chan KL, & Ip P. (2019). Insecure adult attachment and child maltreatment: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 20(5), 706–719. doi: 10.1177/1524838017730579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londerville S, & Main M. (1981). Security of attachment, compliance, and maternal training methods in the second year of life. Developmental Psychology, 17(3), 289–299. 10.1037/0012-1649.17.3.289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luyten P, Mayes LC, Nijssens L, & Fonagy P. (2017). The parental reflective functioning questionnaire: Development and preliminary validation. PloS one, 12(5), e0176218. 10.1371/journal.pone.0176218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon CA, & Bernier A. (2017). Twenty years of research on parental mind-mindedness: Empirical findings, theoretical and methodological challenges, and new directions. Developmental Review, 46, 54–80. 10.1016/j.dr.2017.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meins E. (1999). Sensitivity, security and internal working models: Bridging the transmission gap. Attachment & Human Development, 1, 325–342. DOI: 10.1080/14616739900134181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, & Shaver PR (2016). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Millings A, Walsh J, Hepper E, & O’Brien M. (2013). Good partner, good parent: Responsiveness mediates the link between romantic attachment and parenting style. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 170–180. doi: 10.1177/0146167212468333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2020). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Negrão M, Pereira M, Soares I, & Mesman J. (2016). Maternal attachment representations in relation to emotional availability and discipline behaviour. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(1), 121–137. DOI: 10.1080/17405629.2015.1071254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putallaz M, Costanzo PR, Grimes CL, & Sherman DM (1998). Intergenerational continuities and their influences on children’s social development. Social Development, 7(3), 389–427. DOI: 10.1111/1467-9507.00074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Holland A, Fortuna K, Fraley R, Clausell E, & Clarke A. (2007). The Adult Attachment Interview and self-reports of attachment style: An empirical rapprochement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 678–697. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostad WL, & Whitaker DJ (2016). The association between reflective functioning and parent-child relationship quality. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(7), 2164–2177. 10.1007/s10826-016-0388-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selcuk E, Gunaydin G, Sumer N, Harma M, Salman S, Hazan C, . . . Ozturk A. (2010). Self-reported romantic attachment style predicts everyday maternal caregiving behavior at home. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.05.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sher-Censor E. (2015). Five Minute Speech Sample in developmental research: A review. Developmental Review, 36, 127–155. 10.1016/j.dr.2015.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A. (2005). Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment & Human Development, 7(3), 269–281. DOI: 10.1080/14616730500245906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, & Fonagy P. (2008). The parent’s capacity to treat the child as a psychological agent: Constructs, measures and implications for developmental psychopathology. Social Development, 17(3), 737–754. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00457.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Dishion TJ, Moore KJ, Shaw DS, & Wilson MN (2013). Effects of video feedback on early coercive parent–child interactions: The intervening role of caregivers’ relational schemas. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(3), 405–417. 10.1080/15374416.2013.777917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA (2016). The place of attachment in development. In Cassidy J. & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed., pp. 997–1011). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stride CB, Gardner S, Catley N. & Thomas F. (2015). Mplus code for the mediation, moderation, and moderated mediation model templates from Andrew Hayes’ PROCESS analysis examples. Retrieved http://www.offbeat.group.shef.ac.uk/FIO/mplusmedmod.htm [Google Scholar]

- Suchman N, DeCoste C, McMahon T, Dalton R, Mayes L, & Borelli J. (2017). Mothering From the Inside Out: Results of a second randomized clinical trial testing a mentalization-based intervention for mothers in addiction treatment. Development and Psychopathology, 29(2), 617–636. doi: 10.1017/S0954579417000220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhage ML, Schuengel C, Madigan S, Fearon RM, Oosterman M, Cassibba R, ... & van IJzendoorn MH (2016). Narrowing the transmission gap: A synthesis of three decades of research on intergenerational transmission of attachment. Psychological Bulletin, 142(4), 337–366. 10.1037/bul0000149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschueren K, Dossche D, Marcoen A, Mahieu S, & Bakermans-Kranenburg M. (2006). Attachment representations and discipline in mothers of young school children: An observation study. Social Development, 15(4), 659–675. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2006.00363.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weston S, Hawes DJ, & Pasalich DS (2017). The five minute speech sample as a measure of parent–child dynamics: Evidence from observational research. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(1), 118–136. 10.1007/s10826-016-0549-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]