Abstract

Objectives

Population-based chronic disease surveillance systems were likely disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The objective of this study was to examine the immediate and ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the claims-based incidence of dementia.

Methods

We conducted a population-based time series analysis from January 2015 to December 2021 in Ontario, Canada. We calculated the monthly claims-based incidence of dementia using a validated case ascertainment algorithm drawing from routinely collected health administrative data. We used autoregressive linear models to compare the claims-based incidence of dementia during the COVID-19 period (2020–2021) to the expected incidence had the pandemic not occurred, controlling for seasonality and secular trends. We examined incidence by source of ascertainment and across strata of sex, age, community size and number of health conditions.

Results

The monthly claims-based incidence of dementia dropped from a 2019 average of 11.9 per 10 000 to 8.5 per 10 000 in April 2020 (32.6% lower than expected). The incidence returned to expected levels by late 2020. Across the COVID-19 period there were a cumulative 2990 (95% CI 2109 to 3704) fewer cases of dementia observed than expected, equivalent to 1.05 months of new cases. Despite the overall recovery, ascertainment rates continued to be lower than expected among individuals aged 65–74 years and in large urban areas. Ascertainment rates were higher than expected in hospital and among individuals with 11 or more health conditions.

Conclusions

The claims-based incidence of dementia recovered to expected levels by late 2020, suggesting minimal long-term changes to population-based dementia surveillance. Continued monitoring of claims-based incidence is necessary to determine whether the lower than expected incidence among individuals aged 65–74 and in large urban areas, and higher than expected incidence among individuals with 11 or more health conditions, is transitory.

Keywords: COVID-19, dementia, public health, geriatric medicine

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The population-based design enables examination of the research question over a large and representative population.

The validated case ascertainment algorithm used in the study draws on health system encounters from multiple sectors.

However, chronic disease ascertainment dates derived from health administrative data may not align with the date of clinical diagnosis.

Introduction

Dementia case ascertainment algorithms based on health administrative data are regularly used in population-based research and chronic disease surveillance.1–3 By tracking the incidence and prevalence of diseases over time, chronic disease surveillance systems provide critical information for public health planning and evaluation.4 In the absence of national registries or screening programmes, administrative databases are a vital source of data on the epidemiology of chronic diseases.5 Claims-based case ascertainment methods for dementia combine information gathered from routinely collected health records, including physician encounters, hospital admissions and dementia-specific medication use, to identify individuals who are likely to have been diagnosed with dementia. The performance of these algorithms varies by setting and jurisdiction, but they typically achieve high positive predictive value with reasonable sensitivity.6 While these algorithms have clear utility, there are also known challenges as the methods depend on interactions with the health system which can be used to identify dementia diagnoses.7 Accurate ascertainment requires equitable and consistent access to health services and recording of relevant diagnoses.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a wide-ranging impact on health service use, including reductions in care volumes across settings,8 rapid uptake of virtual care9 and changes in the most common reasons for which healthcare was sought.10 Examining changes in the claims-based incidence of dementia will yield insight into the disruptions of the pandemic on physician diagnoses of dementia. The extent and longevity of any impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on claims-based incidence of dementia has important implications for the future use of population-based dementia estimates. The objective of this study was to examine how the claims-based incidence of dementia changed across the COVID-19 period in Ontario, Canada, both immediately at the start of the pandemic as well as over time. We examined differences in the claims-based incidence across contributing data sources (physician encounters, hospital admissions, medications) and across sociodemographic strata of age, sex, community size and health conditions.

Methods

Setting and study design

We conducted a time series analysis using population-based health administrative data sets in Ontario, Canada. Ontario has a population of approximately 15 million individuals, including more than 2 million over the age of 65 years.11 Ontario’s health system includes publicly funded universal health insurance for medically necessary services, including physician care, hospital-based care and medication coverage for individuals aged 65 years and older. According to Canadian guidelines,12 routine cognitive screening of asymptomatic individuals for mild cognitive impairment or dementia is not recommended, but the assessment of cognition, activities of daily living and neuropsychiatric symptoms is indicated when there are clinically significant concerns for a cognitive disorder. In Ontario, there are no incentives for clinicians to screen for dementia.13

Population

Our population was an open cohort of older adults aged 65 years and older at risk of dementia. We included older adults living in both community and congregate care settings.

Dementia case ascertainment

We used the dementia case definition from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System.14 The validated algorithm identifies individuals likely diagnosed with dementia using administrative records from physician encounters, hospital admissions and use of dementia-specific medications. Individuals are considered to have been likely diagnosed with dementia when they meet any one of the following criteria: (1) three separate physician encounters with a dementia International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision (ICD-9)/ICD-10 code, with at least 30 days separating each encounter; (2) a single hospital admission with a dementia ICD-9/ICD-10 code; or (3) a single dispensation of a dementia-specific medication (ie, cholinesterase inhibitors). The ascertainment date is identified as the earliest of the hospital admission date, the medication dispensation date or the last date of the physician encounter sequence. In Ontario, the algorithm was found to outperform other claims-based formulations and achieved a sensitivity of 79.3%, a specificity of 99.1% and a positive predictive value of 80.4%.15 A full definition of the algorithm including all ICD-9/ICD-10 codes and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical codes is listed in online supplemental table 1. The lookback window in the administrative data to exclude individuals with prevalent dementia from the incidence calculation extended back to 1996.

bmjopen-2022-067689supp001.pdf (66.6KB, pdf)

Data sources

Diagnosis codes from physician encounters and hospital admissions were extracted from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database and the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s Discharge Abstract Database, respectively. Medication use was captured from the Ontario Drug Benefit database. Ontario’s insurable population was identified using the Registered Persons Database. These data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analysed at ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences). ICES is an independent, non-profit research institute whose legal status under Ontario’s health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyse healthcare and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement.

Claims-based incidence of dementia

We calculated the monthly claims-based incidence of dementia per 10 000 individuals among older adults (65+ years) in Ontario at risk of dementia between January 2015 and December 2021. The incidence was calculated as the number of new ascertainments in a month, divided by the population at risk of dementia at the start of the month, divided by the count of days in the month, multiplied by 30.

Statistical analysis

We fit autoregressive linear regression models to the monthly claims-based dementia incidence.16 Seasonality was controlled for using an indicator variable for each month17 and long-term trend via a linear term on the number of months since beginning of the time series. The model was fit on the pre-COVID-19 pandemic period (2015–2019). This model was used to generate what the expected incidence of claims-based dementia would have been during the COVID-19 period (2020–2021) had the pandemic not occurred. We calculated relative and absolute differences between observed and expected claims-based dementia incidences. We characterised the initial decline in claims-based incidence by comparing the observed and expected incidences at the month of the lowest observed incidence in 2020. We calculated the difference between the counts of observed and expected dementia case ascertainments by applying the difference between the observed and expected incidences to the population at risk each month. We examined cumulative differences in the count of observed and expected dementia case ascertainments within calendar years and across the entire COVID-19 period. We constructed 95% CIs around the cumulative differences in case ascertainments during the COVID-19 period using a 5000-replicate block bootstrap18 with a block size of 3 months. To facilitate comparison across strata of different sizes, we expressed the cumulative difference in case ascertainments in terms of the number of months of new ascertainments they represent based on 2019 figures.

We stratified the main analysis by data source (physician encounters, hospital admissions, medications) to identify whether certain sources were more strongly affected by the pandemic. We additionally stratified by age (65–74, 75–84, 85+), sex (male vs female), community size (large urban, small urban, rural) and count of health conditions (0–5, 6–10, 11+) to explore differential effects across sociodemographic strata. Community size was defined using the Rurality Index of Ontario.19 Health condition count was defined using the Canadian Institute for Health Information Population Health Grouper,20 which includes 226 health conditions that can be ascertained via administrative data sources. All analyses were performed using R 4.0.3.21

Sensitivity analysis

To examine whether the changes in claims-based incidence were related to a shifting population composition, we repeated the main analyses using incidence rates that were standardised to the age-sex distribution of Ontario in January 2015. We also repeated the main analysis among only the community-dwelling older adult population to examine to what degree changes were due to the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on long-term care homes.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved at the conduct of this study due to limited time and resources. We have invited patients and stakeholders to help us develop and carry out our knowledge dissemination strategy.

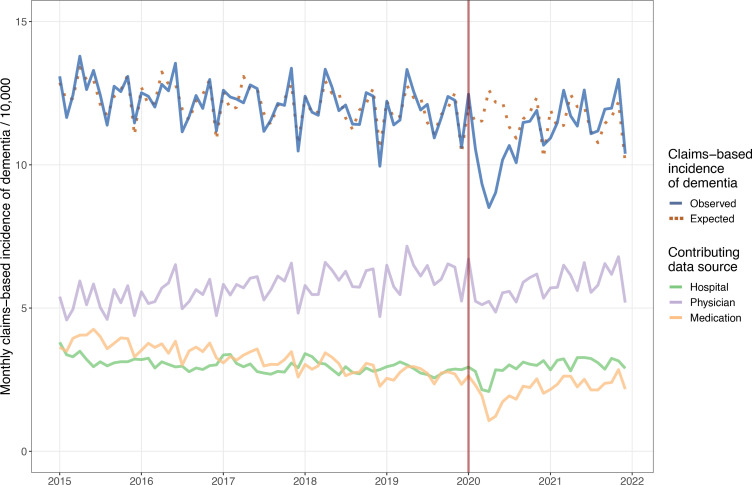

Results

The population of the older adults at risk of dementia varied from 2 030 431 (January 2015) to 2 569 017 (December 2021). The monthly claims-based incidence of dementia declined slightly across the pre-COVID-19 period from an average of 12.5 cases per 10 000 in 2015 to 11.9 cases per 10 000 in 2019. Physician encounters were the most common source of case ascertainment across the entire time series, representing approximately 50% of new cases. Claims-based incidence dropped sharply during the first months of the COVID-19 period reaching a nadir of 8.5 per 1000 in April 2020 (32.6% less than expected) (table 1). By late 2020, the observed incidence had returned to the prepandemic expected incidence but did not appreciably rebound above expected levels (figure 1).

Table 1.

Observed and expected claims-based dementia incidences with relative and absolute differences, January 2020 to December 2021, Ontario, Canada

| Month | Observed incidence | Expected incidence | Relative difference (%) | Absolute difference in cases*† | Cumulative difference in cases since January 2020 | Cumulative difference in months of expected cases‡ |

| January 2020 | 12.5 | 12.1 | 3 | 95 | 95 | 0.03 |

| February 2020 | 10.5 | 11.5 | −8 | −225 | −130 | −0.05 |

| March 2020 | 9.3 | 11.5 | −19 | −540 | −670 | −0.23 |

| April 2020 | 8.5 | 12.6 | −33 | −1012 | −1682 | −0.59 |

| May 2020 | 9.0 | 12.2 | −26 | −781 | −2463 | −0.86 |

| June 2020 | 10.2 | 12.2 | −17 | −501 | −2964 | −1.04 |

| July 2020 | 10.7 | 11.3 | −6 | −162 | −3125 | −1.09 |

| August 2020 | 10.1 | 10.9 | −8 | −213 | −3338 | −1.17 |

| September 2020 | 11.5 | 11.6 | −1 | −30 | −3369 | −1.18 |

| October 2020 | 11.5 | 11.8 | −3 | −77 | −3446 | −1.21 |

| November 2020 | 11.9 | 12.4 | −4 | −114 | −3560 | −1.25 |

| December 2020 | 10.7 | 10.3 | 4 | 110 | −3450 | −1.21 |

| January 2021 | 10.9 | 11.9 | −8 | −253 | −3703 | −1.30 |

| February 2021 | 11.5 | 11.3 | 1 | 42 | −3661 | −1.28 |

| March 2021 | 12.6 | 11.4 | 11 | 311 | −3350 | −1.17 |

| April 2021 | 11.7 | 12.5 | −6 | −191 | −3541 | −1.24 |

| May 2021 | 11.3 | 12.0 | −6 | −174 | −3714 | −1.30 |

| June 2021 | 12.6 | 12.0 | 5 | 148 | −3567 | −1.25 |

| July 2021 | 11.1 | 11.2 | −1 | −20 | −3587 | −1.26 |

| August 2021 | 11.2 | 10.8 | 4 | 105 | −3482 | −1.22 |

| September 2021 | 11.9 | 11.4 | 4 | 129 | −3353 | −1.17 |

| October 2021 | 12.0 | 11.7 | 3 | 78 | −3275 | −1.15 |

| November 2021 | 13.0 | 12.2 | 6 | 205 | −3070 | −1.07 |

| December 2021 | 10.4 | 10.1 | 3 | 80 | −2990 | −1.05 |

| 2020 Cumulative difference in cases (95% CI) | −3450 (−3753 to −3078) | |||||

| 2021 Cumulative difference in cases (95% CI) | 460 (49 to 957) | |||||

| 2020–2021 Cumulative difference in cases (95% CI) | −2990 (−3704 to -2109) | |||||

*Calculated as difference between observed and expected incidences multiplied by population at risk of dementia, rounded to whole number.

†Rounded to whole number.

‡Based on monthly average of new ascertainments in 2019.

Figure 1.

Claims-based incidence of dementia in Ontario, Canada between 2015 and 2021 by data source.

Between January 2020 and December 2021, there were a cumulative 2990 (95% CI 2109 to 3704) fewer case ascertainments observed than expected, a gap equivalent to 1.05 months of cases based on 2019 averages. The vast majority of the fewer-than-expected ascertainments were accumulated between February 2020 and June 2020. Across 2021 as a whole, there were slightly more cases observed than expected (460 cases, 95% CI 49 to 957). In each of the final 5 months of the time series, the observed count exceeded the expected count by 3%–6% (table 1).

All data sources exhibited drops in claims-based incidence during the first months of the pandemic, with medication use demonstrating the largest relative decrease (59.4%) in April 2020, compared with 26.9% for physician encounters, and 27.4% for hospital admissions (figure 2, table 2). After the initial decline, ascertainments in the hospital setting recovered the quickest, followed by medication use. Throughout 2021, observed case ascertainment from physician encounters continued to lag behind expected ascertainments, while observed ascertainments in the other settings exceeded the expected number of cases.

Figure 2.

Claims-based incidence of dementia in Ontario, Canada between 2015 and 2021 by sex, age, and community size, and count of health conditions.

Table 2.

Changes in the claims-based dementia incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic with cumulative differences between observed and expected cases, by data source, sex, age, community size and chronic condition count in Ontario, Canada

| Measure | Overall | Data source | ||

| Physician encounters | Hospital admissions | Medication use | ||

| 2019 Average incidence/10 000 | 11.9 | 6.2 | 2.9 | 2.7 |

| 2020 Nadir incidence/10 000 | 8.5 | 4.9 | 2.1 | 1.1 |

| Per cent drop in incidence at nadir versus expected (%) | 32.6 | 26.9 | 27.4 | 59.4 |

| 2020 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | −1.21 (−1.32, −1.08) | −1.63 (−1.53, 1.41) | 0.32 (−0.03, 0.72) | −1.78 (−2.19, −1.38) |

| 2021 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | 0.16 (0.01, 0.32) | −1.23 (−1.52, −0.94) | 1.90 (1.43, 2.45) | 1.51 (0.96, 2.04) |

| 2020–2021 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | −1.05 (−1.31, −0.77) | −2.86 (−3.36, −2.35) | 2.23 (1.38, 3.17) | −0.27 (−1.23, 0.66) |

| Measure | Overall | Sex | ||

| Male | Female | |||

| 2019 Average incidence/10 000 | 11.9 | 10.7 | 12.9 | |

| 2020 Nadir incidence/10 000 | 8.5 | 7.4 | 9.4 | |

| Per cent drop in incidence at nadir versus expected (%) | 32.6 | 34.6 | 31.1 | |

| 2020 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | −1.21 (−1.32, −1.08) | −1.06 (−1.23, −0.88) | −1.32 (−1.47, −1.16) | |

| 2021 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | 0.16 (0.01, 0.32) | 0.32 (0.10, 0.55) | 0.04 (−0.16, 0.26) | |

| 2020–2021 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | −1.05 (−1.31, −0.77) | −0.73 (−1.13, −0.33) | −1.28 (−1.63, −0.90) | |

| Measure | Overall | Age | ||

| 65–74 | 76–85 | 85+ | ||

| 2019 Average incidence/10 000 | 11.9 | 3.6 | 15.6 | 48.4 |

| 2020 Nadir incidence/10 000 | 8.5 | 2.7 | 10.6 | 36.0 |

| Per cent drop in incidence at nadir versus expected (%) | 32.6 | 30.1 | 36.0 | 30.0 |

| 2020 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | −1.21 (−1.32, −1.08) | −1.39 (−1.64, −1.17) | −1.19 (−1.36, −0.99) | −1.08 (−1.28, −0.89) |

| 2021 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | 0.16 (0.01, 0.32) | −0.29 (−0.59, −0.02) | 0.40 (0.16, 0.65) | 0.16 (−0.09, 0.41) |

| 2020–2021 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | −1.05 (−1.31, −0.77) | −1.67 (−2.26, −1.16) | −0.49 (−1.20, −0.35) | −0.92 (−1.38, −0.49) |

| Measure | Overall | Community size | ||

| Large urban | Small urban | Rural | ||

| 2019 Average incidence/10 000 | 11.9 | 12.4 | 10.9 | 11.0 |

| 2020 Nadir incidence/10 000 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 7.7 | 7.1 |

| Per cent drop in incidence at nadir versus expected (%) | 32.6 | 32.4 | 31.0 | 38.8 |

| 2020 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | −1.21 (−1.32, −1.08) | −1.46 (−1.25, −1.54) | −0.53 (−0.24, −0.81) | −0.89 (−1.43, −0.33) |

| 2021 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | 0.16 (0.01, 0.32) | −0.20 (−0.36, −0.02) | 0.94 (0.61, 1.30) | 0.04 (−0.69, 0.77) |

| 2020–2021 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | −1.05 (−1.31, −0.77) | −1.62 (−1.90, −1.26) | 0.41 (−0.20, 0.90) | −0.86 (−2.11, 0.44) |

| Measure | Overall | Health conditions | ||

| 0–5 | 6–10 | 11+ | ||

| 2019 Average incidence/10 000 | 11.9 | 6.5 | 14.8 | 42.1 |

| 2020 Nadir incidence/10 000 | 8.5 | 4.6 | 10.7 | 35.7 |

| Per cent drop in incidence at nadir versus expected (%) | 32.6 | 34.4 | 30.9 | 17.8 |

| 2020 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | −1.21 (−1.32, −1.08) | −1.92 (−2.19, −1.66) | −0.50 (−0.72, −0.26) | 1.00 (0.76, 1.23) |

| 2021 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | 0.16 (0.01, 0.32) | −0.68 (−0.35, 0.05) | 1.37 (1.10, 1.66) | 2.44 (2.14, 2.73) |

| 2020–2021 Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases (in months of new cases)* | −1.05 (−1.31, −0.77) | −2.30 (−2.87, −1.60) | 0.88 (0.38, 1.40) | 3.44 (2.90, 3.96) |

*Cumulative difference between observed and expected cases expressed in terms of the number of months of new cases based on 2019 figures.

Analysis across sociodemographic strata

Initial declines in claims-based incidence across sociodemographic strata were broadly similar, with the smallest drop at 30.0% less than expected among individuals aged 85+ and the largest drop at 38.8% less than expected among individuals living in rural locations (figure 2, table 2). Recoveries were uneven, however, and ascertainments in 2021 among individuals aged 65–74 and those residing in large urban locations tracked below expected levels, while ascertainments among those in small urban locations tracked significantly higher.

More differences were evident across strata defined by number of health conditions. The initial drop in the strata of 0–5 conditions was 34.4% compared with only 17.8% in the strata of those with 11+ conditions. Notably, while the claims-based incidence in the 0–5 condition group recovered much more slowly than the overall population, the incidence in the 11+ group exceeded the expected ascertainment counts even in 2020 and ended the 2020–2021 period with an excess of 3.44 months of ascertainments.

Sensitivity analysis

The standardised claims-based incidence rate remained similar to observed rate across the study period, drifting higher to a maximum difference of 0.18 in March 2021 (online supplemental table 2). Repeating the primary analysis using the standardised incidence rate yielded a cumulative difference of 1.04 (0.73, 1.30) months fewer ascertainments than expected, nearly identical to the main analysis (online supplemental table 3). Including only the community-dwelling population reduced the average 2019 incidence per 10 000 from 12.04 to 10.32. Replicating the primary analysis resulted in a cumulative difference of 0.89 (0.57, 1.23) months fewer ascertainments than expected across the pandemic period, slightly lower than the primary analysis.

Discussion

We found that the claims-based incidence of dementia in Ontario dropped sharply at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Claims-based incidence returned to expected levels by the end of 2020 but did not appreciably rebound above the expected levels. As a result, across the pandemic period there have been significantly fewer dementia ascertainments observed than expected. Although the overall incidence returned to normal levels, the recovery was uneven. Cases ascertained via physician encounters, among individuals 65–74 years of age, and in large urban areas have continued to lag expected counts. Cases ascertained in hospital and among individuals with 11 or more health conditions have exceeded expected counts.

The drop in the claims-based incidence of dementia in early 2020 mirrors the reductions in health service use that occurred in Ontario at the same time across multiple sectors, including outpatient physician visits, emergency department visits and hospital admissions.8 9 22 At the nadir in April 2020, hospitalisations and emergency department visits were approximately 50% lower than historical levels, while rates of outpatient physician services dropped by 40%. However, usage rates within all sectors returned to normal levels by the end of 2020. The observed claims-based incidence also returned to the expected incidence along the same timeline, which broadly suggests no major long-term changes to the performance of the case ascertainment algorithms. A temporary drop in the claims-based incidence due to lockdowns, avoidance of in-person visits and reduced access to community-based physician care may amount to a mere historical anomaly. However, the small, but enduring, ascertainment gap bears continued monitoring.

The aetiology of the persistent undercount in cases is likely multifactorial in nature. Given how closely the fall and rise of the claims-based incidence follows the broader rates of health service use, one likely contributor is change in health-seeking behaviour, patient access to healthcare services and delivery of health services during the pandemic and recovery. This is further supported by the observation of larger impacts in the younger and healthier groups that typically use less care. Younger individuals experienced greater relative reductions in health service use during the pandemic compared with older individuals, and therefore it may take more time for the ascertainment rates for younger individuals to regain their normal levels.23 Beyond changes in health service use, another likely contributing factor is higher relative mortality rates among individuals at higher risk of developing dementia.24 This effect would be most noticeable among population with the high COVID-related mortality, such as residents of long-term care homes. A mortality effect likely explains the differences we observed between the overall population and community-dwelling subset.

Notably, we found that ascertainments from physician encounters lagged expected counts throughout the entire pandemic period, despite the fact that overall physician visit volumes recovered to normal levels in 2020.23 This may be related to the rapid uptake of virtual care as the challenges of performing cognitive testing virtually may lead to fewer or delayed diagnoses of dementia as physicians adapt to new tools.25 26 For example, comorbid sensory impairment is a contraindication for remote cognitive screening.27 Additionally, virtual care may also be less accessible to older adults living with frailty or without a caregiver.28 Finally, ascertainments via physician encounters are more susceptible to disruption as the algorithm requires a specific number of visits within a specific time frame. An interruption in access may break the sequence of visits and delay ascertainment. The lower-than-expected incidence within large urban areas is at a glance surprising as individuals within these areas typically have the greatest access to healthcare.29 However, the shift to virtual visits was most pronounced in urban areas.9 Additionally, urban areas were under strict public health measures for longer periods of time and therefore individuals in these areas may have experienced longer delays in resuming normal health service use levels.30

While we observed fewer-than-expected cases within most strata, there were two subgroups for which we observed higher incidence—hospital ascertainments and individuals with 11 or more health conditions. The increase in the ascertainments in hospital is concordant with published reports that hospital admission rates for dementia and delirium increased or held study during the pandemic even as overall hospitalisation rates declined.2 31–33 The population with 11 or more health conditions is small, representing approximately 7% of the older adult population without dementia, but is highly comorbid, is at high risk of developing dementia and frequently uses the healthcare system.34 The higher incidence in this population may be partially a result of increased social isolation in those living alone and visitation restrictions in hospitals and congregate care settings. Conversely, for those living in multigenerational households, the increase in remote work during the pandemic may have afforded caregivers additional opportunity to observe cognitive or behavioural changes in older family members, leading them to seek formal evaluation. Additionally, there is emerging evidence that cognitive decline, including increased risk of developing dementia, is a long-term sequela of COVID-19 infection.35 Further cohort studies should focus on changes in dementia incidence in this highly comorbid population.

The unevenness of the rebound in claims-based incidence of dementia across various sociodemographic strata warrants ongoing monitoring to determine whether the incidence eventually reverts to the long-term averages. Research studies that rely on claims-based dementia ascertainment to generate cohorts or define outcomes need to carefully consider the impact of the pandemic on their research. Additionally, health system policymakers should carefully consider the impact of any future public health restrictions on individuals at elevated risk of developing dementia. In particular, ensuring family members and caregivers can visit patients in hospital and long-term care homes can reduce the risk of delirium and dementia associated with increased social isolation. Also, in-person healthcare visits for individuals with difficulty participating in virtual consultations should be preserved to protect access to care and diagnosis. A missed or delayed diagnosis of dementia reduces the time during which the person living with dementia can maintain control of decision-making and care planning and delays the initiation of interventions that may slow cognitive decline.36 37

Limitations

Case ascertainment via administrative data enables population-based chronic disease surveillance, but does not perfectly correspond to clinical diagnoses or necessarily represent the experience of the individual. For example, a physician may communicate a diagnosis to the patient without entering it into the administrative record. In addition, case detection via administrative data requires equitable access to care and thus may underperform among populations with impaired access. Ultimately, research using case ascertainment from administrative data cannot replace traditional cohort studies to capture the patient experience of people living with dementia. Additionally, distinguishing delirium from dementia can be challenging, particularly in acute care settings.38 Higher ascertainment rates in highly comorbid populations and in hospital settings may be in part due to diagnostic challenges. Finally, differences in the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic and the public health system response may result in differences in how population-based dementia estimates have changed across jurisdictions.

Conclusion

Claims-based dementia incidence as estimated from routinely collected data fell early in the COVID-19 pandemic but returned to expected levels by late 2020. However, as of the end of 2021, there were still significantly fewer cumulative dementia cases observed than expected across the pandemic period. Rates of case ascertainment were lower than expected among individuals aged 65–74 years and in large urban areas even after health service use rebounded. Cases ascertained in hospital and among individuals with 11+ health conditions were higher than expected. Continued population-based monitoring of dementia incidence is necessary to identify whether these effects are transitory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank IQVIA Solutions Canada for use of their Drug Information File.

Footnotes

Twitter: @aaronjonesstats, @LaurenGriff1

Contributors: AJ, APC and LEG conceived the work. AJ developed the design and conducted all analyses. DK performed data curation. AJ wrote the initial draft. AJ, SEB, LCM, RLJ, DK, AM, APC and LEG contributed to the interpretation of the work and revised the work for critical intellectual content. AJ is responsible for the overall content as the guarantor.

Funding: This study received funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada (2021-HQ-000076). This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care.

Disclaimer: Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Ontario Ministry of Health. This document used data adapted from the Statistics Canada Postal CodeOM Conversion File, which is based on data licensed from Canada Post, and/or data adapted from the Ontario Ministry of Health Postal Code Conversion File, which contains data copied under licence from Canada Post and Statistics Canada. Parts of this material are also based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While legal data sharing agreements between ICES and data providers (e.g., healthcare organizations and government) prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS (email: das@ices.on.ca). The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

ICES is a prescribed entity under Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA). Section 45 of PHIPA authorises ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management, evaluation or monitoring of the allocation of resources to or planning for all or part of the health system. Projects that use data collected by ICES under section 45 of PHIPA, and use no other data, are exempt from REB review. The use of the data in this project is authorised under section 45 and approved by ICES Privacy and Legal Office.

References

- 1.Davis MA, Chang C-H, Simonton S, et al. Trends in US Medicare decedents' diagnosis of dementia from 2004 to 2017. JAMA Health Forum 2022;3:e220346. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones A, Maclagan LC, Watt JA, et al. Reasons for repeated emergency department visits among community-dwelling older adults with dementia in Ontario, Canada. J Am Geriatr Soc 2022;70:1745–53. 10.1111/jgs.17726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welberry HJ, Brodaty H, Hsu B, et al. Measuring dementia incidence within a cohort of 267,153 older Australians using routinely collected linked administrative data. Sci Rep 2020;10:8781. 10.1038/s41598-020-65273-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thacker SB, Stroup DF, Rothenberg RB. Public health surveillance for chronic conditions: a scientific basis for decisions. Stat Med 1995;14:629–41. 10.1002/sim.4780140520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lix LM, Yogendran MS, Shaw SY, et al. Population-Based data sources for chronic disease surveillance. Chronic Dis Can 2008;29:31–8. 10.24095/hpcdp.29.1.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkinson T, Ly A, Schnier C, et al. Identifying dementia cases with routinely collected health data: A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14:1038–51. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Festa N, Price M, Moura LMVR, et al. Evaluation of Claims-Based ascertainment of Alzheimer disease and related dementias across health care settings. JAMA Health Forum 2022;3:e220653. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bronskill SE, Maclagan LC, Maxwell CJ, et al. Trends in health service use for Canadian adults with dementia and Parkinson disease during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum 2022;3:e214599. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.4599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glazier RH, Green ME, Wu FC, et al. Shifts in office and virtual primary care during the early COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ 2021;193:E200–10. 10.1503/cmaj.202303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephenson E, Butt DA, Gronsbell J, et al. Changes in the top 25 reasons for primary care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic in a high-COVID region of Canada. PLoS One 2021;16:e0255992. 10.1371/journal.pone.0255992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ontario.ca . Ontario population projections. Available: http://ontario-v2.vpc.ont/page/ontario-population-projections [Accessed 24 Aug 2021].

- 12.Ismail Z, Black SE, Camicioli R, et al. Recommendations of the 5th Canadian consensus conference on the diagnosis and treatment of dementia. Alzheimers Dement 2020;16:1182–95. 10.1002/alz.12105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thavam T, Devlin RA, Thind A, et al. The impact of the diabetes management incentive on diabetes-related services: evidence from Ontario, Canada. Eur J Health Econ 2020;21:1279–93. 10.1007/s10198-020-01216-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canada PHA of . The Canadian chronic disease surveillance system – an overview, 2018. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/canadian-chronic-disease-surveillance-system-factsheet.html [Accessed 6 Jun 2022].

- 15.Jaakkimainen RL, Bronskill SE, Tierney MC, et al. Identification of Physician-Diagnosed Alzheimer's disease and related dementias in population-based administrative data: a validation study using family physicians' electronic medical records. J Alzheimers Dis 2016;54:337–49. 10.3233/JAD-160105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.GEP B, Jenkins GM, Reinsel GC. Time series analysis: Forecasting and control. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall, 1994. http://www.gbv.de/dms/bowker/toc/9780130607744.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:348–55. 10.1093/ije/dyw098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lahiri SN. Theoretical comparisons of block bootstrap methods. The Annals of Statistics 1999;27:386–404. 10.1214/aos/1018031117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kralj B. Measuring Rurality - RIO2008_BASIC: Methodology and Results. Toronto: Ontario Medical Association, 2009. https://docplayer.net/91599736-Measuring-rurality-rio2008_basic-methodology-and-results.html [Google Scholar]

- 20.CIHI’s Population Grouping Methodology 1.3 — Overview and Outputs 2021;28. [Google Scholar]

- 21.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Axenhus M, Schedin-Weiss S, Tjernberg L, et al. Changes in dementia diagnoses in Sweden during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Geriatr 2022;22:365. 10.1186/s12877-022-03070-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CIHI . COVID-19’s impact on physician services |. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/en/covid-19-resources/impact-of-covid-19-on-canadas-health-care-systems/physician-services [Accessed 7 Jun 2022].

- 24.Wang Y, Li M, Kazis LE, et al. Clinical outcomes of COVID-19 infection among patients with Alzheimer's disease or mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement 2022;18:911–23. 10.1002/alz.12665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saxena S, Factora R, Hashmi A, et al. Assessing cognition in the era of COVID19: do we need methods to assess cognitive function virtually? Alzheimers Dement 2021;17 Suppl 8:e050074. 10.1002/alz.050074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watt JA, Lane NE, Veroniki AA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of virtual cognitive assessment and testing: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69:1429–40. 10.1111/jgs.17190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geddes MR, O'Connell ME, Fisk JD, et al. Remote cognitive and behavioral assessment: report of the Alzheimer Society of Canada Task force on dementia care best practices for COVID-19. Alzheimers Dement 2020;12:e12111. 10.1002/dad2.12111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L, Goodarzi Z, Jones A, et al. Factors associated with virtual care access in older adults: a cross-sectional study. Age Ageing 2021;50:1412–5. 10.1093/ageing/afab021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geographic variation in the supply and distribution of comprehensive primary care physicians in Ontario, 2014/15. Available: https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2017/Geographic-variation-in-physician-supply [Accessed 29 Jun 2022].

- 30.Canadian Institute for Health Information . COVID-19 intervention Timeline in Canada | CIHI. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/en/covid-19-intervention-timeline-in-canada [Accessed 29 Jun 2022].

- 31.Jones A, Mowbray FI, Falk L, et al. Variations in long-term care home resident hospitalizations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario. PLoS One 2022;17:e0264240. 10.1371/journal.pone.0264240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maclagan LC, Wang X, Emdin A, et al. Visits to the emergency department by community-dwelling people with dementia during the first 2 waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario: a repeated cross-sectional analysis. CMAJ Open 2022;10:E610–21. 10.9778/cmajo.20210301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Canadian Institute for Health Information . COVID-19’s effect on hospital care services. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/en/covid-19-resources/impact-of-covid-19-on-canadas-health-care-systems/covid-19s-effect-on-hospital [Accessed 18 Oct 2021].

- 34.Weir S, Steffler M, Li Y, et al. Use of the population grouping methodology of the Canadian Institute for health information to predict high-cost health system users in Ontario. CMAJ 2020;192:E907–12. 10.1503/cmaj.191297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y-H, Chen Y, Wang Q-H, et al. One-Year trajectory of cognitive changes in older survivors of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Neurol 2022;79:509–17. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gamble LD, Matthews FE, Jones IR, et al. Characteristics of people living with undiagnosed dementia: findings from the CFAS Wales study. BMC Geriatr 2022;22:409. 10.1186/s12877-022-03086-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, et al. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:306–14. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a6bebc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson TA, Gladman JRF, Harwood RH, et al. Challenges and opportunities in understanding dementia and delirium in the acute Hospital. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002247. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-067689supp001.pdf (66.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While legal data sharing agreements between ICES and data providers (e.g., healthcare organizations and government) prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS (email: das@ices.on.ca). The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.