Abstract

Nanotechnology is one of the most important and relevant disciplines today due to the specific electrical, optical, magnetic, chemical, mechanical and biomedical properties of nanoparticles. In the present study we demonstrate the efficacy of Cuphea procumbens to biogenerate silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with antibacterial and antitumor activity. These nanoparticles were synthesized using the aqueous extract of C. procumbens as reducing agent and silver nitrate as oxidizing agent. The Transmission Electron Microscopy demonstrated that the biogenic AgNPs were predominantly quasi-spherical with an average particle size of 23.45 nm. The surface plasmonic resonance was analyzed by ultraviolet visible spectroscopy (UV–Vis) observing a maximum absorption band at 441 nm and Infrared Spectroscopy (FT IR) was used in order to structurally identify the functional groups of some compounds involved in the formation of nanoparticles. The AgNPs demonstrated to have antibacterial activity against the pathogenic bacteria Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, identifying the maximum zone of inhibition at the concentration of 0.225 and 0.158 µg/mL respectively. Moreover, compared to the extract, AgNPs exhibited better antitumor activity and higher therapeutic index (TI) against several tumor cell lines such as human breast carcinoma MCF-7 (IC50 of 2.56 µg/mL, TI of 27.65 µg/mL), MDA-MB-468 (IC50 of 2.25 µg/mL, TI of 31.53 µg/mL), human colon carcinoma HCT-116 (IC50 of 1.38 µg/mL, TI of 51.07 µg/mL) and melanoma A-375 (IC50 of 6.51 µg/mL, TI of 10.89 µg/mL). This fact is of great since it will reduce the side effects derived from the treatment. In addition, AgNPs revealed to have a photocatalytic activity of the dyes congo red (10–3 M) in 5 min and malachite green (10–3 M) in 7 min. Additionally, the degradation percentages were obtained, which were 86.61% for congo red and 82.11% for malachite green. Overall, our results demonstrated for the first time that C. procumbens biogenerated nanoparticles are excellent candidates for several biomedical and environmental applications.

Subject terms: Cancer, Nanoscience and technology

Introduction

Nanotechnology is currently widely used in different areas1 such as solar energy conversion2, catalysis3, medicine4, and water treatment5. Some specific applications of nanotechnology in biotechnology6 and biomedicine7 include additives for textile industry8, food packaging9, 10, protein immobilization11, and development of optoelectronic materials12. Due to its versatility, there is an increasing interest in designing new methods for nanoparticle synthesis and modification or functionalization of its surface to improve their effectiveness. Green synthesis has shown a great potential because it is inexpensive and easy to reproduce method. Moreover, it has several applications because chemical elements in their nanometric or nanoparticle (NP) form have different properties than those properties manifested on the micro or macroscopic scale or even in their ionic form13–15. One of the most widely used nanoparticles, both at the industry and biomedical level, are silver and gold nanoparticles. Specifically silver nanoparticles play an important role in the field of biology and medicine16, 17 due to their attractive antimicrobial, antibacterial, antifungal18, 19, anticoagulant20, thrombolytic20, antidiabetic21, antioxidant22 and antiviral properties13.

Silver nanoparticles can be generated through several methods23, but the most common include physical, chemical and biological components. Although it is true that the green synthesis has three main components: a metal precursor24, a reducing agent25 and a stabilizing agent26, it could be said that it is a derivative of both methods (chemical and biological). One of the fundamental pillars of biosynthesis is to obtain extracts with high antioxidant power such as polyphenols24, reduced sugars, nitrogenous bases and amino acids; capable of reducing cations in a metal salt solution. Silver nanoparticles show great reactivity with enzymes, DNA and RNA27, caused by the interactions with thiol, carboxylate, phosphate, hydroxyl, imidazole, indole or amine groups, triggering a series of reactions that prevent the formation of microbial processes1. It is important to recognize that there is a wide variety of biological resources that can be used for green or ecological synthesis, such as microorganisms (bacteria28, 29, fungi29, algae30), plants and their derivatives31, animal metabolites and even organic waste32, which opens up a range of possibilities to generate nanoparticles as well as to apply them in various areas.

Recently, AgNPs have been widely used to degrade organic dyes through redox potential techniques and photocatalytic reaction under solar radiation33. In addition, AgNPs are used as an antimicrobial agents for a wide range of microorganisms and their use as cytotoxic agent against cancer cells has also become popular in recent years34. Some plant extracts have a potent antibacterial activity against a variety of bacteria, including E. coli and S. aureus6. These findings highlight the importance of synthesizing nanoparticles from plant extracts. The proposed mechanism of action of AgNPs includes the attraction between positive charge of Ag ions and negative charge of the bacterial membrane which results in the alteration of the cell membrane. Moreover, Ag ions affect the activity of vital enzymes including those related to DNA replication. The anticancer activity of AgNPs has been related to the induction of cell apoptosis through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)34.

The genus Cuphea comprises more of 260 species that are native to the Americas distributed from Mexico to Brazil. Cuphea procumbens specie has oil35 rich in medium chain fatty acids and are used in traditional (folk) medicine for their antioxidant, antihypertensive, cytotoxic, antiprotozoal and hypocholesterolemia activities36. It is a peculiar herbaceous plant native to southern Mexico, which grows in a rudimentary way in cultivated fields with moist soil, roadsides, low fields prone to flooding, on the banks of rivers and in other disturbed swampy sites, it is important to note that C. procumbens is not an endangered species. On the other hand, C. procumbens is well known as a cancer herb37. As its name suggests, this plant has been used in the treatment of various cancers for its pain reliver properties and anti-inflammatory activities38. This plant has anti-inflammatory properties and it is often used to reduce the swelling caused by injuries39. Analgesic properties of C. procumbens can be used to relieve headaches or other types of pain. The phytochemical analysis of this plant has shown the presence of alacaloids, flavonoids and glycosides in extract fractions. Several studies indicate that some flavonoids have pro-oxidant actions at high doses but at low doses they have anti-inflammatory, antiviral or antiallergic effects40. Thus, we decided to synthesize AgNPs using C. procumbens extracts to potentiate the beneficial effects of this plant. We designed a protocol to obtain AgNPs that could be used in three main applications including degradation of dyes, antibacterial tests and antitumor agents.

Results

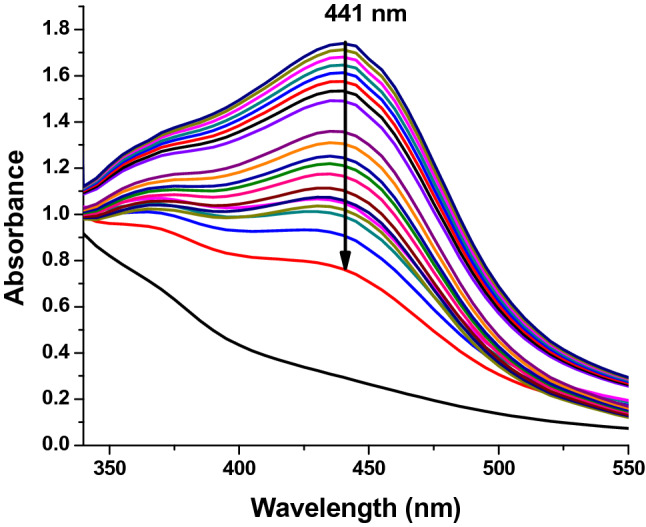

In the process of nanoparticle synthesis one of the characteristic effects is the color change from light brown to dark brown, which suggests the formation of AgNPs through extracellular activity41. Figure 1 shows UV spectral analysis at different time intervals. The UV–vis spectrum of the silver nanoparticles shows the monitoring of the formation of nanoparticles in a period of 6 h, recording the activity every 20 min. The UV–Vis spectrum indicated the presence of a strong and broad band in a range from 350 to 450 nm, and specifically showing a maximum absorption peak at 441 nm, which is attributed to the Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)42. This is due to the nucleation and growth of nanoparticles produced as a result of the reduction of silver ions present in the solution43.

Figure 1.

UV–vis absorption kinetic spectra of C. procumbens synthesized silver nanoparticles every 20 min for 6 h.

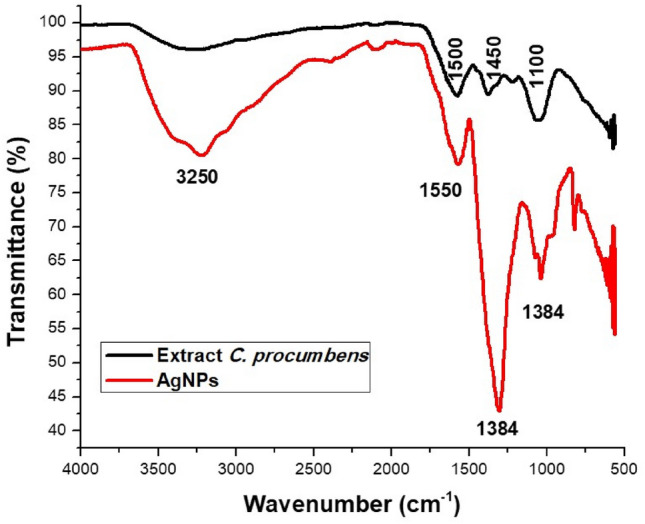

The aqueous extract of C. procumbens has bioorganic compounds bound to the surface of the AgNPs which were identified by FT-IR spectroscopy (Fig. 2) The strong absorption peaks of the leaf extract of C. procumbens were observed at 1500, 1450 and 1100 cm−1. The change in vibration around 1450 cm−1 of C. procumbens suggested the presence of aliphatic –CH and aromatic-OH groups such as hydroxy flavones and hydroxy xanthones39. The vibration around 1100 cm−1 was attributed to the primary amine C-N stretching vibrations of aliphatic amines, the presence of N–H stretching of amine groups, aliphatic C–H stretchings44, C–N stretching of amines/proteins and C–H stretchings, respectively and according to other authors.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of C. procumbens extract and AgNPs.

The FTIR spectra of AgNPs also showed peaks at 3250, 1550, 1384, 1100 cm−1 due to O–H stretching of polyphenols , C=C or C=O stretch of carboxylic acids14, amide stretching, C–O stretching, C–N stretching of amine proteins27, alkene C=C stretchings, =C–H bending and bending vibration of C–H stretching18, respectively.

The peaks at 1550 and 1450 cm−1 are characteristic of primary amide stretches45. These functional groups are representative of the amide or polyphenol groups of C. procumbens, which are responsible for the formation and stabilization of AgNPs.

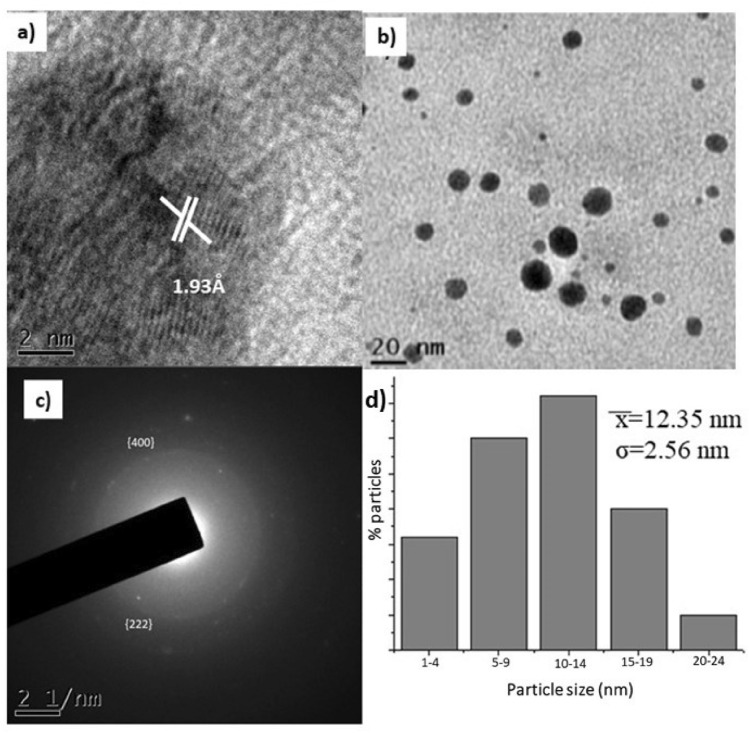

In the TEM micrographs we can observe that through a high-resolution analysis (HRTEM) in Fig. 3a, the crystalline structure of the AgNPs was corroborated with the measurements of the interplanar distance of 1.93 Å, which corresponds to the [200] plane. Regarding Fig. 3b it is clearly shown that biogenic AgNPs are predominantly nearly spherical. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) (Fig. 3c), indicated that the measurements of the family of crystalline planes correspond to the metal Ag and to the FCC (Face Centered Cubic) crystalline structure, which we corroborate from JCPDS card 00-004-0783. The size distribution histogram of AgNPs ranged from ∼2–24 nm ( = 12.35 nm, σ = 2.56 nm, Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) micrographs; (a) corresponding high-resolution analysis by Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM), (b) analysis biogenerated AgNPs (c) Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED), and (d) average nanoparticle diameter histogram.

Regarding the characterization of the size, it was found by DLS (dynamic light scattering) that the hydrodynamic size is 23.45 nm, while the polydispersity index (PDI) was 0.242.

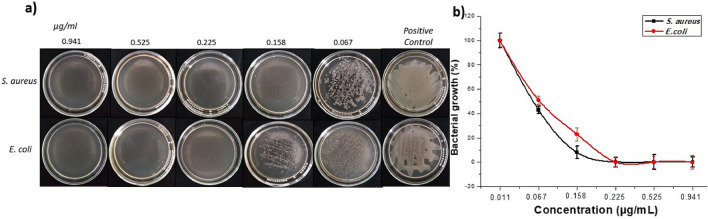

The results of the "broth microdilution" test are shown in Fig. 4, to evaluate the antibacterial activity of the AgNPs, the pathogenic strains of E. coli and S. aureus were used. AgNPs were effective against both strains. In E. coli. the maximum zone of inhibition was at a concentration of 0.225 µg/ml. while for S. aureus it was 0.158 µg/mL, as shown in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Antimicrobial assay; (a) Antimicrobial test of silver nanoparticles against E. coli and S. aureus (b) Graph of microbial growth with respect to different concentrations of nanoparticles.

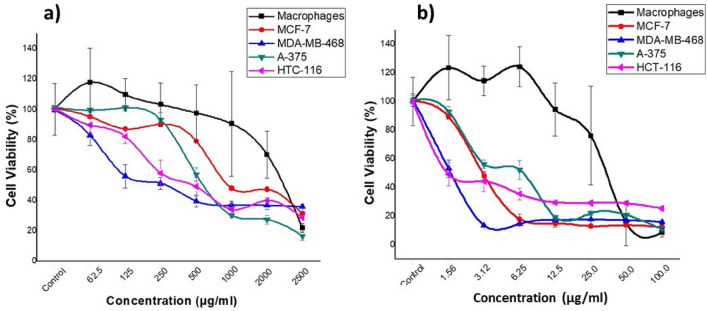

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration and maximum effective concentration of AgNPs.

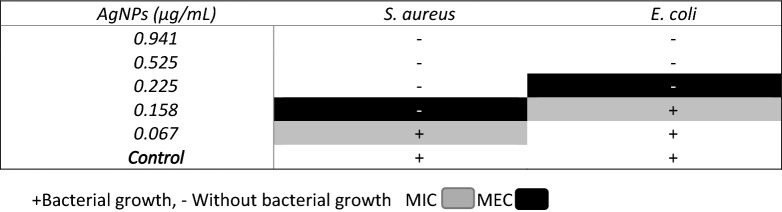

To evaluate the antitumor effect of AgNPs and C. procumbens extracts, cell viability assays were performed with colon cancer cell lines (HCT-116), melanoma (A-375), breast cancer (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468) and macrophages (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 6 and Table 2, AgNPs effectively reduced cell viability in all cancer cell lines, AgNPs effectively reduced cell viability in all cancer cell lines, with values of 1389, 6.515, 2.556, 2250 for HCT-116, A-375, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468 cell lines, respectively.

Figure 5.

Graphs of the percentage of cell viability with respect to different concentrations of: (a) extracts of C. procumbens and (b) silver nanoparticles (AgNPs).

Figure 6.

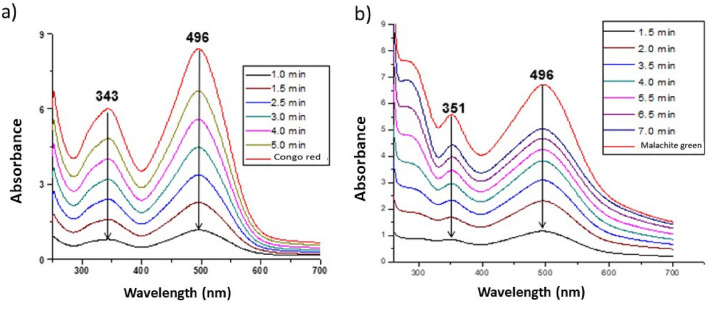

Study of kinetics of the (a) congo red and (b) malachite green dye degradation by the synthesized AgNPs.

Table 2.

Antiproliferative activities (IC50 (µg/mL)) of AgNPs and C. procumbens extracts in cancer cell lines and macrophages. All the experiments were performed in triplicate.

| Treatment | MCF-7 | MDA-MB-468 | A-375 | HCT-116 | Macrophages | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | r2 | IC50 | r2 | IC50 | r2 | IC50 | r2 | IC50 | r2 | |

| Agnps | 2.566 | 0.9345 | 2.250 | 0.9132 | 6.515 | 0.9928 | 1.389 | 0.8903 | 70.950 | 0.9454 |

| C. Procumbens extract | 687.5 | 0.9678 | 314.5 | 0.9793 | 935.4 | 0.9298 | 492.5 | 0.8980 | 71.344 | 0.9239 |

The percentage of viability decreased with increasing concentrations of the plant extract (Fig. 5a). The IC50 of the extract are higher than IC50 of AgNPs (Table 2). As expected the AgNPs potentiated the effect (Fig. 5b) as it has been observed by other research groups46. Likewise, the therapeutic index values indicated that the effect of the AgNPs is higher than the extract alone (Table 3).

Table 3.

Therapeutic indexes (µg/mL) for AgNPs and C. procumbens extract for different tumor cell lines compared to the macrophage cell line.

| Treatment | MCF-7 | MDA-MB-468 | A375 | HCT-116 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AgNPs | 27.65 | 31.53 | 10.89 | 51.07 |

| C. procumbens extract | 0.103 | 0.226 | 0.076 | 0.144 |

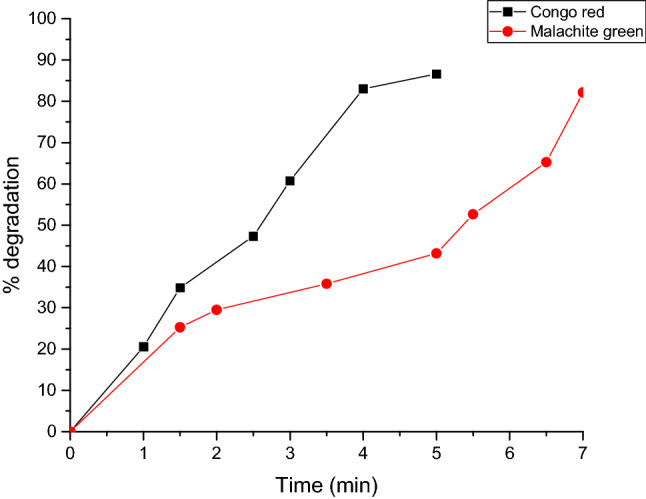

The ability of the AgNPs to degrade congo red and malachite green dye of the synthesized AgNPs is presented in Fig. 6. Congo red and malachite green are non-biodegradable and toxic azo dyes that can be degraded through the use of NPs. The degradation reaction of congo red and malachite green was monitored by UV–Vis spectrophotometer. Congo red in water showed a band at 496 nm and an electron transition of 343 nm associated with the azo group. While the malachite green degradation reaction showed an SPR band at 496 nm and an electron transition of 351 nm. From these graphs, it is observed that the absorption peak of the dye molecules gradually decreased over time. The absorption peak disappeared and the color of the solution changed from red to colorless.

Regarding the degradation percentages, we observed a value of 86.61% for congo red and 82.11% for malachite green, observing a significant decrease in dye degradation from the first contact (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Graph of the percentage of degradation of the dye Congo red and malachite green with respect to time.

Discussion

According to the potential the AgNPs can be used in three main application including degradation of dyes, antibacterial tests and antitumor agents. The formation of AgNPs was monitored47, observing a change in color of the reaction mixture that began to change from a light yellow to dark brown after 6 h, which indicated the generation of AgNPs, due to the participation of a redox reaction of silver metal Ag+ ions in silver Ag° nanoparticles through the active molecules present in the extract of C. procumbens48. This color is attributed to the excitation of SPR49. A characteristic and well-defined SPR band for silver nanoparticles was obtained at around λ 441 nm7.

FTIR measurements of biosynthesized AgNPs were performed to identify possible biomolecules responsible for the stabilization of AgNPs. Previous studies have revealed that carbonyl, amide, and amino groups show a tendency to bond with metal particles. This helps to form a layer on the metallic nanoparticles, which ensures their stabilization and agglomeration. The amide and other functional groups in the extract can probably influence the interaction of AgNPs with peptides or carbohydrates, thus stabilizing them. The smaller size and crystal structure of AgNPs have excellent antimicrobial potential50. TEM analysis of the particles provides information on size and formation. The mean sizes of polydispersed silver AgNPs have been shown to be 20 nm. TEM images of silver nanoparticles have shown that the morphology of silver nanoparticles was predominantly quasi-spherical with a mean diameter of 12.3 nm and a standard deviation 2.56 nm. These results are similar to those obtained by other authors using the same methodology51–53. This is due to the bioreduction from various compounds in the medium, as commonly occurs in green synthesis. In addition, it is possible to corroborate the crystal structure of the AgNPs, in fact it coincided with what is specified by card 00-004-078354 with an analysis corresponding to the micrographs of HRTEM and SAED, with this analysis it is determined that AgNPs are indeed composed of the element Ag (FCC). The data obtained from the DLS measurements of hydrodynamic size and polydispersity index (PDI) were 23.45 nm and 0.242 respectively. As can be seen there is a difference of 11.15 nm ± 2.56, this is due to that only the nanoparticle count was made through a small part of the copper grid while the DLS technique is more precise and takes into account the sample in solution without eliminating the medium in which the nanoparticles are suspended. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) values of AgNPs against E. coli and S. aureus were obtained to determine the lowest concentration of AgNPs that can cause the inhibition of the growth of the bacteria E. coli and S. aureus. Cultures of E. coli and S. aureus without nanoparticle treatment were used as controls; AgNPs showed the highest activity against E. coli with a MIC value of 0.225 mg/mL, while for S. aureus the MIC value was 0.158 mg/mL. This indicates that the AgNPs biogenerated in this study were more selective towards Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli) than Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus) (Fig. 4).

AgNPs activity is highly dependent on AgNPs concentration. This is in accordance with what was reported in a previous work55. The interface between bacteria and AgNPs can generally be described by the following approaches: first, nanoparticles possess an extremely large surface area that provides better contact and interaction with bacterial cells18. Second, their interactions may be between positively charged membrane proteins present on the surface of bacteria and negatively charged AgNPs56. Furthermore, the attraction of these NPs to the surface of the cell membrane depends on the particle's surface area. The smaller size of the AgNPs will offer a better surface area that can interact and penetrate the membrane of the cell surface. This will provide a significant bactericidal effect and cause bacterial cell death56.

Likewise, it is possible to observe a very important principle; apparently our generated nanoparticles, unlike the extract, exert their antiproliferative effect on tumor cells with much lower concentrations that go unnoticed by macrophages. This fact is of great importance as it could prevent many of the side effects of current cancer treatments. It may be due to that AgNPs are going to sites with greater energetic activity, such as tumors or cancer cells57.

It is important to recognize that the biogenerated AgNPs have a powerful antitumor effect on cell lines from various tissues, highlighting its effect on the colon cancer line HCT-116 (IC50 = 1.389; TI = 51.07). This effect is comparable with those obtained with C. colosynthis extracts58. Moreover, our results showed that IC50 values exceed the effect of other plants as a reducing agent. For example Sijo Francis presents values of 15.68 μg/mL for AgNPs synthesized based on E. scaber on the A-375 cancer cell line46. Similarly, Jannathul Firdhouse M. & Lalitha P. reported IC50 values of 3.04 μg/mL for AgNPs biosynthesized with Alternanthera sessilis against the MCF-7 cancer cell line that are higher doses that the ones we obtained59. Other studies also showed the IC50 of d Fumaria parviflora extract and AgNPs- d Fumaria parviflora against MDA-MB-468 cancer cells were observed at 100 µg/mL and 80 µg/mL respectively60. Therefore, it is assumed that the potentiated effect of the nanoparticles is due to the component of the C. procumbens extracts (Table 2) that is working as a reducing and stabilizing agent of the AgNPs. We observed that the concentration of the extract used for the biogeneration of nanoparticles is sufficient to generate antitumor activity, bioreduce nanoparticles and stabilize them. It should be noted that these results depend greatly on the concentration of metabolites present in the extracts and on the concentrations of the precursor salt used61. If we compare with recent studies of AgNPs synthesized by chemical methods, such as the nanoparticles synthesized by Al-Khedhairy, AA and Wahab, R.62 in which they report an IC50 value of 9.85 µg/mL, as we can see the IC50 values are more lower than even the values provided by a chemical synthesis. That makes our research generate greater interest. We attribute this important property to the potentiation of the effect of the AgNPs and the aqueous extract of C. procumbens as a whole.

The importance of our work relies in the therapeutic index (TI) obtained, since its value was high for all tumor cell lines treated with AgNPs compared to the extract (Table 3). The best TI was achieved with HCT-116 and MDA-MB-468 (TI = 51.07 and 31.53 respectively). In the specific case of the MCF-7 cell line, a value of 27.65 was obtained. and it was compared with Melia dubia63 and Cassia fistula64, which present a therapeutic index of 16.02 and 9.23 respectively,. Additionally, human lung epithelial carcinoma cells (A549) and human breast epithelial cells (HBL100) have been studied through the therapeutic index with silver nanoparticles obtained with plant extracts, obtaining a therapeutic index of 2.63. In human cervical cancer (HeLa) cells, metal nanoparticles generated from green synthesis have had therapeutic indices of ≤ 2.565. In addition, we have seen that a similar concentration of the extract and the AgNPs induces inhibition of 50% of macrophage proliferation. Hence, we suspect that tumor cells are less susceptible to damage from flavonoids present in the aqueous extract of C. procumbens, while AgNPs enhance its antitumor effect. This is due to the rapid proliferation of cancer cells, since they require high levels of energy, so they can be more sensitive and have important physiological changes66.

Congo red is a diazo-anionic dye67. This colorant, in addition to affecting the aesthetics, the transparency of the water and the solubility of oxygen in the bodies of water, has been reported as highly toxic for living beings because it causes carcinogenesis, mutagenesis, teratogenesis, respiratory damage, allergies and problems during pregnancy68. The congo red or salt of 3,3'- (4,4'-biphenylenebis (azo) bis (4-amino) disodium naphthylene sulfonic acid is prepared by a tetradiazotization with benzidine and naphthylsulfonic acid. The covalent bonds in the molecule confer stability, which together with the complex molecular structure they make biodegradation and photodegradation difficult. Congo red in an aqueous solution (distilled water) shows a Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) band at 496 nm (π → π) and the electronic transition at 351 nm (north → π) is associated with the azo group. In Fig. 6a it is observed that the absorption peak of the dye molecules gradually decreases in a time dependent manner. The solution fades from red to colorless. Malachite green is a cationic triphenylmethane dye that is widely used in various fields as a parasiticide. The catalytic degradation of the malachite green organic dye was controlled by the change in the absorbance of ultraviolet light. In addition, the degradation capacity in liquid medium was evaluated (Fig. 6b)69. According to the literature, the photocatalytic activity33 of NPs depends on the shape, size and crystalline structure of particles69. To our knowledge, this is the first time that biosintethized AgNPs are able to degrade this colorant at a low concentration. Our results are really very promising, compared to other authors such as Lateef and Akande70, who only reach 80% degradation with 20 µg/mL70, which is interesting because the concentration of nanoparticles used in our study is much lower. Even other authors report that using NaBH4 manage to degrade colorants in a longer period of time71, comparing our results it is important to highlight that we are not using any type of additional catalyst72, nor radiation or exposure to light, in addition to applying other techniques73.

Methods

Biosynthesis

Preparation of the extract of C. procumbens

For the elaboration of the aqueous extract, leaves of C. procumbens were collected in the month of May in the municipality of Villa Victoria, State of Mexico, Mexico, handling of plants were carried out in accordance with Mexican guidelines and regulations, washed thoroughly with distilled water, allowed to dry at room temperature for 15 days, chopped finely and ground, in 100 mL of sterile distilled water, 0.5 g of the treated leaves of C. procumbens were added and heated to boiling point for 5 min. Then was filtered the extract through Whatman No. 1 filter paper (size of 25 µm pore). A second filtration step was carried out using Amicon Ultra-15 30 kDa tubes. To purify the aqueous extract, we performed a second filtration step using an Amicon 30 kDa ultrafiltration unit. The ultrafiltration units were centrifuged at 300 rpm for 10 min.

Synthesis of silver nanoparticles

For the synthesis of nanoparticles, a 0.001 M aqueous solution of Silver Nitrate AgNO3 (Sigma-Aldrich) and an aqueous solution of C. procumbens extract were used. With a volume-to-volume ratio of 1:1, that is, 5 mL of aqueous extract of C. procumbens as reducing agent and 5 mL of silver nitrate precursor salt as oxidizing agent. The silver ions were reduced to metallic silver within 6 h, showing a color change from light to dark brown.

Characterization of AgNPs

UV–Vis spectroscopy

UV–Vis spectroscopic analysis was performed to monitor the formation of AgNPs using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (VE-5100UV spectrophotometer, USA)28. UV–Vis adsorption spectra were measured in a 1 cm quartz cuvette using 2 mL of the synthesized AgNPs solution. The samples were measured in wavelength ranges between 350 and 750 nm.

Catalytic degradation of congo red and malachite green dye

An aqueous solution of the malachite green and congo red dyes (10–3 M) was prepared. Then 0.1 ml of AgNPs (0.941 µg/mL) solution was added to 2 mL of the dye solution. The dye degradation experiments were carried out under shaking and irradiation of a solar simulator (ScienceTech SF150B). The degradation of the solution was followed by measuring the absorption band characteristic of dye, using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (VE-5100UV spectrophotometer, USA). To obtain the percentage of degradation: the dyes and the AgNPs were kept in linear agitation during the degradation period, additionally Eq. (1) was used.

| 1 |

where A0 is the initial absorbance of the dye and At is the absorbance of the dye at a specific time.

FTIR analysis

FTIR spectrums of the biogenic AgNPs and plant extracts were obtained in a Perkin Elmer spectrophotometer (L16000300 Spectrum Two LiTa, Llantrisant, UK), using the potassium bromide (KBr) pellet method. The samples were measured in wavelength ranging between 500 and 4000 cm−1.

TEM analysis

Morphology and size distribution of AgNPs were investigated using a JEOL-2100 High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscope (HR-TEM). Samples were prepared by placing a drop of AgNPs, dispersed in solution, followed by solvent evaporation.

Characterization of the size and zeta potential

The hydrodynamic mean diameter of the AgNPs was determined by photon correlation spectroscopy (PCS), using a 4700 C light-scattering device (Malvern Instruments, London, UK) working with a He–Ne laser (10 mW). The diffusion coefficient measured by the dynamic light scattering was used to calculate the size of the AgNPs by means of the Stokes–Einstein equation. The homogeneity of the size distribution is expressed as polydispersity index (PDI), which was calculated from the analysis of the intensity autocorrelation function (Zeta-Sizer Nano Z, Malvern Instruments, UK).

Broth dilution test

Experiments on antimicrobial or antifungal activity were performed as described by the Institute for Clinical and Laboratory Standards (Wikler, 2009). AgNPs were tested against human pathogenic strains such as S. aureus ATCC25293 and E. coli ATCC25922 by determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and the minimum effective concentration (MEC) following the broth microdilution method (Kim and Anthony, 1981). Bacteria were cultured to prepare 0.5 McFarland standards. Mueller–Hinton broth medium (100 µl) was placed in each well and 100 µl AgNPs was added and then serial dilutions were made starting from the first row. A negative control (broth and microorganisms) and a sterile control (broth only) were used. Each well was then aseptically inoculated with 5 µl of the microorganism suspension (the final concentration was approximately 5 × 105 CFU/mL). Assays were performed in triplicate for each concentration and strain. The inoculated microplates were incubated at 37° C with continuous shaking at 200 rpm for 24 h. Subsequently, the colonies were counted and the MIC and MEC were determined.

Cell viability assay

Breast cancer (MCF-7, MDA-MB-468), colon cancer (HCT-116), Melanoma (A-375) cell lines and macrophages were obtained from the Biobank (Sistema Sanitario Publico Andaluz, Granada, Spain). Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The cells (5 × 103 cells) were seeded in 96-well plates at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and 24 h later, the cells were treated with different concentrations of biosynthesized AgNPs and incubated for 3 days. Then, the medium was removed and the cells were washed with PBS. Subsequently, 100 μL of 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2, 5-diphenyl-2-tetrazoyl bromide (MTT) (at a concentration of 0.2 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for three hours. After this time, the MTT reagent was removed, and the formazan crystals formed were dissolved by adding 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) per well and analyzed at 570 nm in a multi-well ELISA plate reader. The inhibitory concentration 50 (IC50) was calculated with the GraphPad Prism program (GraphPad 6 Software San Diego, CA, EE. UU). All the experiments were plated in triplicate and were carried out at least twice. In addition, non-treated cells were used as controls. The therapeutic index was calculated for both the extracts and the AgNPs, from Eq. (2). The therapeutic index is expressed numerically as a ratio between the dose of the drug that causes death (lethal dose or DL) or a deleterious effect in a proportion "x" of the sample and the dose that causes the desired therapeutic effect (effective dose or DE) in the same or greater proportion "y" of the sample.

| 2 |

Statistic analysis

The data collection from the different biological studies represents the mean ± standard deviation. The two-tailed Student's t-test was used to compare the differences between two groups. A two-tailed p value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Conclusions

Biogenerating silver nanoparticles from natural products such as the aqueous extract of C. procumbens is an environmentally friendly method, does not produce unwanted contaminants and is very easy to reproduce. Our results show that biogenerated AgNPs has potential as a microbial agent, anticancer agent, and also opens the possibility for the degradation of specific dyes. It is a simple procedure with several advantages such as cost-effectiveness, biocompatibility for medical applications, as well as large-scale commercial production. These results give us an opening to continue investigating the applications that we will surely be reporting in future works.

Acknowledgements

To the Mexican Council of Science and Technology (COMECYT) for the "Financing for Research of Women Scientists" of the Fund for Scientific Research and Technological Development of the State of Mexico and the FEDER Operational Program 2020/Junta de Andalucía-Consejería de Economía y Conocimiento/ Project (B-CTS-562-UGR20).

Author contributions

Writing—preparation of the original draft and Experimentation, M.G.G.-P. and A.R.T.B., review and edition-methodology-microbiology test; M.G.G.-P., formal analysis in the synthesis of nanoparticles-broth microdilution test; S.A.N.-M.; statistical analysis; E.M.-M., writing—preparation of the original draft and discussion, E.M.-M., re-search-interpretation, discussion of MTT test; J.A.M. and H.B.; Design of the reduction agent and the nanoparticle synthesis, discussion proposal M.G.G.-P. and R.A.M.-L.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

María G. González-Pedroza, Email: mggonzalezp@uaemex.mx

Houria Boulaiz, Email: hboulaiz@ugr.es.

Raúl A. Morales-Luckie, Email: rmoralesl@uaemex.mx

References

- 1.Morales-Díaz AB, Juárez-Maldonado A, Morelos-Moreno Á, González-Morales S, Benavides-Mendoza A. Biofabricación de nanopartículas de metales usando células vegetales o extractos de plantas. Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas. 2016;7:1211–1224. doi: 10.29312/remexca.v7i5.247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyoshi JH, et al. Essential oil characterization of Ocimum basilicum and Syzygium aromaticum free and complexed with β-cyclodextrin. Determination of its antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antitumoral activities. J. Inclus. Phenomena Macrocycl. Chem. 2022;102:117–132. doi: 10.1007/s10847-021-01107-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gama-Lara, S. A. et al. Synthesis, characterization, and catalytic activity of platinum nanoparticles on bovine-bone powder: A novel support. J. Nanomater.2018 (2018).

- 4.Zhang, L. G., Leong, K. & Fisher, J. P. 3D Bioprinting and Nanotechnology in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (Academic Press, 2022).

- 5.Benakashani F, Allafchian A, Jalali S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Capparis spinosa L. leaf extract and their antibacterial activity. Karbala Int. J. Mod. Sci. 2016;2:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.kijoms.2016.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asimuddin M, et al. Azadirachta indica based biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and evaluation of their antibacterial and cytotoxic effects. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2020;32:648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2018.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibrahim HM. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using banana peel extract and their antimicrobial activity against representative microorganisms. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2015;8:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jrras.2015.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah, M. A., Pirzada, B. M., Price, G., Shibiru, A. L. & Qurashi, A. Applications of nanotechnology in smart textile industry: A critical review. J. Adv. Res. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Pushparaj K, et al. Nano-from nature to nurture: A comprehensive review on facets, trends, perspectives and sustainability of nanotechnology in the food sector. Energy. 2022;240:122732. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2021.122732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibri Albarracín, V. N. Aplicaciones de la nanotecnología para el envasado de alimentos. (2022).

- 11.Tsriwong, K. & Matsuda, T. Recent Advances in Enzyme Immobilization Utilizing Nanotechnology for Biocatalysis. Organ. Process Res. Develop. (2022).

- 12.Frohna K, et al. Nanoscale chemical heterogeneity dominates the optoelectronic response of alloyed perovskite solar cells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022;17:190–196. doi: 10.1038/s41565-021-01019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashraf A, et al. Synthesis, characterization, and antibacterial potential of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Coriandrum sativum L. J. Infect. Public Health. 2019;12:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balavijayalakshmi J, Ramalakshmi V. Carica papaya peel mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its antibacterial activity against human pathogens. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 2017;15:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jart.2017.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fatimah I. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using extract of Parkia speciosa Hassk pods assisted by microwave irradiation. J. Adv. Res. 2016;7:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Tawil RS, et al. Silver/quartz nanocomposite as an adsorbent for removal of mercury (II) ions from aqueous solutions. Heliyon. 2019;5:e02415. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdel-Raouf N, Al-Enazi NM, Ibraheem IBM, Alharbi RM, Alkhulaifi MM. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by using of the marine brown alga Padina pavonia and their characterization. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019;26:1207–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh A, Gaud B, Jaybhaye S. Optimization of synthesis parameters of silver nanoparticles and its antimicrobial activity. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2020;3:232–236. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yassin MA, et al. Characterization and anti-Aspergillus flavus impact of nanoparticles synthesized by Penicillium citrinum. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017;24:1243–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azeez, M. A. et al. 1 edn 012043 (IOP Publishing).

- 21.Botha, S., Badmus, J. A. & Oyemomi, S. A. Photo-assisted bio-fabrication of silver nanoparticles using Annona muricata leaf extract: Exploring the antioxidant, anti-diabetic, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic activities (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Lateef, A. et al. 1 edn 012042 (IOP Publishing).

- 23.Kalaivani R, et al. Synthesis of chitosan mediated silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) for potential antimicrobial applications. Front. Lab. Med. 2018;2:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.flm.2018.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao H, Yang H, Wang C. Controllable preparation and mechanism of nano-silver mediated by the microemulsion system of the clove oil. Results Phys. 2017;7:3130–3136. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2017.08.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kharat SN, Mendhulkar VD. Synthesis, characterization and studies on antioxidant activity of silver nanoparticles using Elephantopus scaber leaf extract. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2016;62:719–724. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur P. Biosynthesis of nanoparticles using eco-friendly factories and their role in plant pathogenicity: A review. Biotechnol. Res. Innov. 2018;2:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biori.2018.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das B, et al. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles destroy multidrug resistant bacteria via reactive oxygen species mediated membrane damage. Arab. J. Chem. 2017;10:862–876. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh M, et al. Bioprospects of endophytic bacteria in plant growth promotion and Ag-nanoparticle biosynthesis. Plants. 2022;11:1787. doi: 10.3390/plants11141787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alavi, M. Bacteria and fungi as major bio-sources to fabricate silver nanoparticles with antibacterial activities. Expert Rev. Anti-infective Therapy, 1–10 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Adelere, I. A. & Lateef, A. Microalgal nanobiotechnology and its applications—A brief overview. Microb. Nanobiotechnol., 233–255 (2021).

- 31.Elegbede, J. A. & Lateef, A. Microbial enzymes in nanotechnology and fabrication of nanozymes: A perspective. Microb. Nanobiotechnol., 185–232 (2021).

- 32.Adelere IA, Lateef A. A novel approach to the green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles: The use of agro-wastes, enzymes, and pigments. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2016;5:567–587. doi: 10.1515/ntrev-2016-0024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saravanan C, et al. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using bacterial exopolysaccharide and its application for degradation of azo-dyes. Biotechnol. Rep. 2017;15:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Brahim JS, Mohammed AE. Antioxidant, cytotoxic and antibacterial potentials of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using bee’s honey from two different floral sources in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020;27:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaedler MI, et al. Redox regulation and NO/cGMP plus K+ channel activation contributes to cardiorenal protection induced by Cuphea carthagenensis (Jacq.) JF Macbr. in ovariectomized hypertensive rats. Phytomedicine. 2018;51:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cardenas-Sandoval B, López-Laredo A, Martínez-Bonfil B, Bermudez-Torres K, Trejo-Tapia G. Avances en la fitoquímica de Cuphea aequipetala, C. aequipetala var hispida y C. lanceolata: Extracción y cuantificación de los compuestos fenólicos y actividad antioxidante. Revista mexicana de ingeniería química. 2012;11:401–413. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krepsky PB, Isidório RG, de Souza Filho JD, Côrtes SF, Braga FC. Chemical composition and vasodilatation induced by Cuphea carthagenensis preparations. Phytomedicine. 2012;19:953–957. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mendoza Uribe G, La Rodríguez-López JL. nanociencia y la nanotecnología: una revolución en curso. Perfiles latinoamericanos. 2007;14:161–186. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hassan SK, et al. Antitumor activity of Cuphea ignea extract against benzo (a) pyrene-induced lung tumorigenesis in Swiss Albino mice. Toxicol. Rep. 2019;6:1071–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gyawali R, et al. Phytochemical studies traditional medicinal plants of Nepal and their formulations. Int. J. Biol. Pharm. Allied Sci. 2014;3:189–203. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alsammarraie FK, Wang W, Zhou P, Mustapha A, Lin M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using turmeric extracts and investigation of their antibacterial activities. Colloids Surf. B. 2018;171:398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katta V, Dubey R. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tagetes erecta plant and investigation of their structural, optical, chemical and morphological properties. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021;45:794–798. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thanh NT, Maclean N, Mahiddine S. Mechanisms of nucleation and growth of nanoparticles in solution. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:7610–7630. doi: 10.1021/cr400544s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sathishkumar R, et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by bloom forming marine microalgae Trichodesmium erythraeum and its applications in antioxidant, drug-resistant bacteria, and cytotoxicity activity. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2019;23:1180–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jscs.2019.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fafal T, Taştan P, Tüzün B, Ozyazici M, Kivcak B. Synthesis, characterization and studies on antioxidant activity of silver nanoparticles using Asphodelus aestivus Brot. aerial part extract. South Afr. J. Bot. 2017;112:346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2017.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Francis S, Joseph S, Koshy EP, Mathew B. Microwave assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaf extract of Elephantopus scaber and its environmental and biological applications. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018;46:795–804. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1345921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nadaf NY, Kanase SS. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by Bacillus marisflavi and its potential in catalytic dye degradation. Arab. J. Chem. 2019;12:4806–4814. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmed S, Ahmad M, Swami BL, Ikram S. A review on plants extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications: A green expertise. J. Adv. Res. 2016;7:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Husseiny SM, Salah TA, Anter HA. Biosynthesis of size controlled silver nanoparticles by Fusarium oxysporum, their antibacterial and antitumor activities. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2015;4:225–231. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prakash P, Gnanaprakasam P, Emmanuel R, Arokiyaraj S, Saravanan M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from leaf extract of Mimusops elengi, Linn. for enhanced antibacterial activity against multi drug resistant clinical isolates. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2013;108:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kokturk M, et al. Investigation of the oxidative stress response of a green synthesis nanoparticle (RP-Ag/ACNPs) in zebrafish. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022;200:2897–2907. doi: 10.1007/s12011-021-02855-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parmar S, et al. Recent advances in green synthesis of Ag NPs for extenuating antimicrobial resistance. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:1115. doi: 10.3390/nano12071115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kordy MGM, et al. Phyto-capped Ag nanoparticles: green synthesis, characterization, and catalytic and antioxidant activities. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:373. doi: 10.3390/nano12030373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moudir N, et al. Preparation of silver powder used for solar cell paste by reduction process. Energy Procedia. 2013;36:1184–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2013.07.134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lakshmanan G, Sathiyaseelan A, Kalaichelvan P, Murugesan K. Plant-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles using fruit extract of Cleome viscosa L.: assessment of their antibacterial and anticancer activity. Karbala Int. J. Mod. Sci. 2018;4:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.kijoms.2017.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramesh A, Devi DR, Battu G, Basavaiah K. A Facile plant mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles using an aqueous leaf extract of Ficus hispida Linn. F. for catalytic, antioxidant and antibacterial applications. South Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2018;26:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.sajce.2018.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haas OC, Burnham KJ, Mills JA. On improving physical selectivity in the treatment of cancer: A systems modelling and optimisation approach. Control. Eng. Pract. 1997;5:1739–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0661(97)10029-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shawkey AM, Rabeh MA, Abdulall AK, Abdellatif AO. Green nanotechnology: Anticancer activity of silver nanoparticles using Citrullus colocynthis aqueous extracts. Adv. Life Sci. Technol. 2013;13:60–70. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Firdhouse J, Lalitha P. Apoptotic efficacy of biogenic silver nanoparticles on human breast cancer MCF-7 cell lines. Prog. Biomater. 2015;4:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s40204-015-0042-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sattari R, Khayati GR, Hoshyar R. Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles capped by biomolecules by Fumaria parviflora extract as green approach and evaluation of their cytotoxicity against human breast cancer MDA-MB-468 cell lines. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020;241:122438. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.122438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patra S, et al. Green synthesis, characterization of gold and silver nanoparticles and their potential application for cancer therapeutics. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2015;53:298–309. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Al-Khedhairy AA, Wahab R. Silver nanoparticles: An instantaneous solution for anticancer activity against human liver (HepG2) and breast (MCF-7) cancer cells. Metals. 2022;12:148. doi: 10.3390/met12010148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kathiravan V, Ravi S, Ashokkumar S. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Melia dubia leaf extract and their in vitro anticancer activity. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014;130:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.03.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanan NA, et al. Cytotoxicity of plant-mediated synthesis of metallic nanoparticles: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:1725. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sukirtha R, et al. Cytotoxic effect of Green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Melia azedarach against in vitro HeLa cell lines and lymphoma mice model. Process Biochem. 2012;47:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2011.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raynaud S, et al. Antitumoral effects of squamocin on parental and multidrug resistant MCF7 (human breast adenocarcinoma) cell lines. Life Sci. 1999;65:525–533. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fu, Y. & Viraraghavan, T. Removal of Congo Red from an aqueous solution by fungus Aspergillus niger. Int. Res, 239–247 (2002).

- 68.Bhattacharyya, K. & Sharma, A. Azadirachta indica leaf powder as an effective biosorbent for dyes: A case study with aqueous Congo Red solutions. J. Environ. Manag. 217–229 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Chand K, et al. Green synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic application of silver nanoparticles synthesized by various plant extracts. Arab. J. Chem. 2020;13:8248–8261. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lateef A, et al. Phytosynthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using miracle fruit plant (Synsepalum dulcificum) for antimicrobial, catalytic, anticoagulant, and thrombolytic applications. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2016;5:507–520. doi: 10.1515/ntrev-2016-0039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bogireddy NKR, Anand KKH, Mandal BK. Gold nanoparticles—Synthesis by Sterculia acuminata extract and its catalytic efficiency in alleviating different organic dyes. J. Mol. Liq. 2015;211:868–875. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2015.07.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raj S, Singh H, Trivedi R, Soni V. Biogenic synthesis of AgNPs employing Terminalia arjuna leaf extract and its efficacy towards catalytic degradation of organic dyes. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66851-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gupta N, Singh HP, Sharma RK. Metal nanoparticles with high catalytic activity in degradation of methyl orange: An electron relay effect. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2011;335:248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.molcata.2010.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.González-Pedroza MG, et al. Silver nanoparticles from Annona muricata peel and leaf extracts as a potential potent, biocompatible and low cost antitumor tool. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:1273. doi: 10.3390/nano11051273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.