Abstract

Introduction

Syringomyelia (SM) is a debilitating spinal cord disorder in which a cyst, or syrinx, forms in the spinal cord parenchyma due to congenital and acquired causes. Over time syrinxes expand and elongate, which leads to compressing the neural tissues and a mild to severe range of symptoms. In prior omics studies, significant upregulation of betaine and its synthesis enzyme choline dehydrogenase (CHDH) were reported during syrinx formation/expansion in SM injured spinal cords, but the role of betaine regulation in SM etiology remains unclear. Considering betaine’s known osmoprotectant role in biological systems, along with antioxidant and methyl donor activities, this study aimed to better understand osmotic contributions of synthesized betaine by CHDH in response to SM injuries in the spinal cord.

Methods

A post-traumatic SM (PTSM) rat model and in vitro cellular models using rat astrocytes and HepG2 liver cells were utilized to investigate the role of betaine synthesis by CHDH. Additionally, the osmotic contributions of betaine were evaluated using a combination of experimental as well as simulation approaches.

Results

In the PTSM injured spinal cord CHDH expression was observed in cells surrounding syrinxes. We next found that rat astrocytes and HepG2 cells were capable of synthesizing betaine via CHDH under osmotic stress in vitro to maintain osmoregulation. Finally, our experimental and simulation approaches showed that betaine was capable of directly increasing meaningful osmotic pressure.

Conclusions

The findings from this study demonstrate new evidence that CHDH activity in the spinal cord provides locally synthesized betaine for osmoregulation in SM pathophysiology.

Supplementary Information

The online version of this article contains supplementary material available 10.1007/s12195-022-00749-5.

Keywords: Post-traumatic syringomyelia, Syrinx, Betaine, Choline dehydrogenase (CHDH), Osmotic pressure, Osmoregulation

Introduction

Betaine, also known as trimethylglycine, is a natural substance widely present in animals, plants, and microorganisms.10 It is a specific type of zwitterion [(CH3)3N+ CH2 COO−] possessing a positively charged quaternary ammonium cation on one side and negatively charged carboxylate anion at another side of the molecule.63 Betaine plays a pivotal role in biological systems due to its significant functions as a methyl donor and as an osmoprotectant. Specifically, betaine is known to play a vital role primarily in the liver and kidney by donating methyl groups to the transmethylation process that utilizes the betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase enzyme to form methionine from homocysteine.54 Additionally, betaine is an essential osmoprotectant that mainly functions in the liver, kidney, and brain.32,61 Betaine can be actively uptaken or accumulated by cells without disrupting cellular integrity and function. Betaine also protects cells, proteins, enzymes against osmotic stress31 by regulating cell volume.35

Since betaine is naturally present in a wide variety of foods humans consume, dietary betaine intake plays an important role in betaine content in the human body, which is accumulated in mainly the kidney, liver, and brain.10,57 Besides dietary intake, betaine can be synthesized endogenously from choline using the enzymes choline dehydrogenase (CHDH) (present in mammals, bacteria, and fungi), choline monooxygenase (present in plants), and choline oxidase (in certain bacteria).53 CHDH (EC 1.1.99.1) is found in the inner membrane of mitochondria, which catalyzes the oxidation of choline into betaine aldehyde then betaine in a later step. The enzymatic activity of CHDH has been detected primarily in the kidney and liver, but lower activity has also been reported in the blood, spleen, heart, and brain.19 Despite the relatively higher concentration of betaine in the brain compared to other organs, osmoregulation in the central nervous system (CNS) and the contribution of betaine has not been well characterized, unlike in plant and bacterial cells,6,7,43,60 and mammalian kidney and liver cells.32,38,61,64

Syringomyelia (SM) is a type of spinal cord disorder in which a fluid-filled cavity/cyst, also known as a syrinx, forms in the spinal cord tissue due to traumatic injuries or other neurological disorders.2,5 Over time the syrinx expands/elongates in the spinal cord compressing the surrounding neural tissue resulting in chronic progressive pain, stiffness in the back, shoulder, hands, and neurological deficits.52 SM is treated with mainly surgical interventions such as decompression, shunting, duraplasty, however, these treatments are associated with long-term high failure rates worsening the quality of life and state of mind of the patients.52 Hence, there is a need for efforts to reveal the molecular and cellular events that occur and are responsible for syrinx formation and expansion, to ultimately design nonsurgical pharmaceutical-based treatment options for SM. Interestingly, our systems biology study of a post-traumatic model of syringomyelia (PTSM) in the rat revealed an upregulation of betaine along with osmoregulated betaine transporter betaine/GABA transporter 1 (BGT1) after 3 and 6 weeks post-injury.41,49 Building on this work our more recent molecular study41 suggested that syrinx expansion may be due in part to extracellular fluid disturbances and subsequent accumulation initiated spinal cord injury, which is exacerbated by a cellular protective response of upregulation of potent osmolytes including betaine alongside associated transporters and channels such as BGT1, Aquaporin 1 (AQP1), Aquaporin 4 (AQP4), potassium (K+) chloride (Cl−) cotransporter 4 (KCC4). Additionally, exogenously provided betaine maintained cell size of rat astrocytes in hypertonic and hypotonic conditions in vitro, indicating a potential role for betaine regulation in the osmotically disturbed PTSM injured spinal cord.48

In this study, we primarily aimed to investigate the role of endogenously synthesized betaine via CHDH in osmoregulation as tied to SM. We first demonstrated the expression and locale of the CHDH enzyme in rat injured spinal cord tissues in vivo. Using a cell culture system, we evaluated the expression of CHDH and its capability to synthesize betaine in astrocytes and HepG2 cells, as a control for CHDH, under different osmotic stresses. Specifically, three different osmotic conditions, isotonic, hypotonic, and hypertonic, were used to investigate betaine synthesis via conversion of exogenously provided choline. To investigate the direct osmotic contributions of betaine, we simulated the osmotic pressure using force field information from the literature4,9,59 and then experimentally validated it in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Rat Model of Post-traumatic Syringomyelia (PTSM)

All experimental surgical and non-surgical manipulations in rats (including those mentioned later) were conducted according to the University of Akron Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). The PTSM surgery was conducted as described in our previous work.12,41,48,50 Briefly, injection of, 2 µL of 24 mg/mL quisqualic acid (QA) (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY) and 5 µL of 250 mg/mL kaolin (Avantor, Center Valley, PA, USA), was performed on the right dorsal spinal cord tissue and subarachnoid space respectively after laminectomy at C7 to T1 spinal level of 10 week old male Wistar rats (Fig. 1a). 6 weeks post-injury, rats were sacrificed using saline and 4% paraformaldehyde perfusion procedure and the spinal cords were dissected for further analysis as described in.17

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic representation of PTSM rat injury model including the injection of kaolin and quisqualic acid at the C7-T1 level. (b) CHDH expression colocalized with mitochondrial VDAC1 in astrocytes from injured PTSM spinal cords (representative images from 3 PTSM injured rats). The asterisk (*) indicates syrinx location in the spinal cord tissue.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The dissected spinal cords (from 3 PTSM injured rats) were embedded in optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Tissue-Tek). Embedded spinal cord tissues were then transversely cryo-sectioned at 15 µm thickness using a cryostat (Leica CM 1850, Wetzlar, Germany) and stored at 4 °C until staining. The sections were co-stained for CHDH (sc-393885, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX, USA) with CNS-specific cells including astrocytes (GFAP marker, Iowa, USA), neurons (β3 tubulin TUJ1 marker, Iowa, USA), and oligodendrocytes (RIP marker, Iowa, USA). We also co-stained for VDAC1 (sc-390996, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX, USA), a mitochondrial marker, to study colocalization with CHDH enzyme expression. The secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-mouse, Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit, Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-mouse (all from Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were used for detection. 10 µM of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) solution was applied to stain cell nuclei. After staining was completed, coverslips were mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Images were taken using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope (Melville, NY, USA) as previously.1,18

Cell Culture

For cell experiments, rat Astrocytes (DI TNC1 (ATCC® CRL2005™)) were cultured and maintained in high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-G—streptomycin. Also, the HepG2 cell line (Hep G2 [HEPG2] (ATCC® HB8065™)) was used for experiments. HepG2 cells were cultured and maintained in low glucose DMEM and supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-G—streptomycin. Both cell types were maintained in an incubator at 37 °C under 5% CO2/95% air. Cells were cultured, passaged, and used for the required experiments under standard sterile conditions in a Class IIA biosafety cabinet in a dedicated culture room.

CHDH Expression In Vitro Model in Rat Astrocytes and HepG2 Cells Using Immunocytochemistry (ICC)

The expression of CHDH under three different osmotic conditions (isotonic, hypertonic, and hypotonic) was determined in both cell lines (DI TNC1 and HepG2) using ICC. The isotonic condition is the regular cell media (293 ± 1.2 mmol/kg for rat astrocytes, and 317 ± 2.4 mmol/kg for HepG2 media). Hypertonic media was prepared by adding 0.5% NaCl salt into the cell culture media (492 ± 2 mmol/kg for rat astrocytes, and 504 ± 1.5 mmol/kg for HepG2 media), whereas hypotonic media was prepared by diluting cell media with an equal amount sterile DI water (169.3 ± 1.7 mmol/kg for rat astrocytes, and 161.3 ± 0.5 mmol/kg for HepG2 media). For CHDH expression experiments, both cell lines were cultured in 24 well plates with a glass coverslip at the bottom until full morphological cell growth. The cells were incubated with one of three different osmotic media overnight. The cells were then washed with 1X phosphate buffer solution (PBS) solution and fixed with paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min followed by washing with 1X PBS 3 times. The staining of cells was conducted as per standard immunochemistry protocols for CHDH using anti-CHDH Antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), and for VDAC1 using Anti-VDAC1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) to colocalize the CHDH in mitochondria. The cell nuclei were stained with a 10 µM DAPI stain. The coverslips from the wells were mounted on glass slides using ProLong™ Gold Antifade. Images were taken using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope (Melville, NY, USA).

Betaine Synthesis by CHDH Under Osmotic Stress

DI TNC1 rat astrocytes and HepG2 hepatocyte cell lines were utilized to understand betaine synthesis from exogenously provided choline by CHDH under different osmotic stress conditions (isotonic, hypotonic, hypertonic). For betaine synthesis experiments, both cell lines were seeded (~ 250,000 cells/well) in 6 well plates for 48 h. Cells were incubated with one of the three osmotic media conditions with and without choline (100 µM) overnight allowing cells to respond to the osmotic stress. After overnight incubations, supernatants and cell pellets were collected for the determination of betaine and choline using the liquid chromatography-mass spectrophotometer (LC–MS) technique described below. Percentage choline consumption was calculated based on the utilized choline by the cells as compared to the control group without cells.

Betaine and Choline Quantification Using Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrophotometer (LC–MS)

LC–MS was used to quantify betaine and choline from the collected supernatant and cell pellet samples after extracting small molecules using a modified Bligh and Dyer extraction method. After extracting small molecules from the samples, they were dried using a Centrivap (Labconco) and resuspended in an 80:10:10 water: acetonitrile: methanol solution. Waters Acquity Ultrahigh Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) system equipped with detector Waters Synapt G-1 Quadrupole Time of Flight (Q-ToF) High Definition Mass Spectrometry (HDMS) instrument was used to perform analysis with Acquity UPLC Protein BEH C4 (2.1 mm × 150 mm, 1.7 µm) column. For runs the mobile phase A was water and mobile phase B was 50:50 acetonitrile: methanol. The gradient proceeded at a flow rate of 200 μL/min as follows: 20% B from 0 to 3 min, 100% B over 2 min. After separation, samples were analyzed on a Waters Synapt G-1 Quadrupole Time of Flight (Q-ToF) High Definition Mass Spectrometry (HDMS) instrument in positive ionization mode. The source parameters were as mentioned, capillary voltage (kV) = 2.5, desolvation gas temperature (°C) = 300, desolvation gas flow (L/hr) = 700. Selective Reaction Mode (SRM) monitoring one transition per analyte for Betaine: 140.07 → 96.08 and for Choline: 104.11 → 59.07. Fragmentation was induced by applying 12 eV in the transfer cell.

Determination of Osmotic Pressure Using Vapor Pressure Osmometer

A vapor pressure osmometer (Wescor Inc.) was employed to determine the osmolality of betaine solutions at different concentrations. 10 μl of the liquid solution was required to determine osmolality using this technique. The osmotic pressure was calculated from the osmolality using the following equation derived from the kinetic and thermodynamic models34,51:

| 1 |

where is osmotic pressure in mmHg, is the volume of the solution in liter, is the number of moles of the solute, is the gas constant, and is the absolute temperature in Kelvin. This equation is analogous to the ideal gas equation and can be rewritten as . The osmotic coefficient is a quantity used to characterize the deviation of a solvent from ideal behavior. It is based on nature and molality i.e. ionic strength of the solute and temperature. For quantification of deviation of ideality, osmotic coefficient () was applied and osmotic pressure equation took a form of . The osmotic coefficient is determined by the degree to which solutes ionically dissociate in the solution. Hence the osmotic coefficient is considered as 1 for solutes that dissociate in the solution completely.14 Also, it is considered approximately 1 for nonelectrolytes such as glucose and urea51 hence we considered the osmotic coefficient for betaine solution as 1. Finally, the osmotic pressure was determined from the following equation:

| 2 |

Simulation

Structure Preparation and Equilibrium

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed to study the effect of the weight fraction of betaine [C5H11NO2] in water on the osmotic pressure of the solution. The weight fractions (w) in the range of 0.0015 to 0.5 were obtained by dispersing betaine in water. The generalized assisted model building with energy refinement (AMBER) force field (GAFF)4,9,59 was used to provide parameters inter-and intra-molecular interactions for betaine molecules, and the TIP3P (3-site rigid non-polarizable mode) model was used for water interactions.33,40,47 The AM1-BCC (AM1 stands for a group of Mulliken-type charges which are obtained from semi-empirical quantum–mechanical calculations and BCC is an abbreviation for bond charge correction) method was applied to assign partial atomic charges by semiempirical quantum mechanics calculations and bond charge corrections.29,30 The cutoff distance for the nonbonded interactions was set to 12 Å. Meanwhile, the long-range Lennard–Jones and electrostatic interactions were calculated using the tail correction approximation and the particle–particle–particle–mesh (PPPM) algorithm, respectively.23 The periodic boundary conditions were applied in all directions. The Nosé-Hoover thermostat was utilized to keep the temperature at T = 300 K and the barostat to maintain the pressure and P = 1 atm.26,45,56 A time step of 1 fs was used to integrate the equations of motion. All the simulations were performed using Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS) package.46

Firstly, the betaine-water mixtures were equilibrated for 2 ns to ensure that the mixture reached equilibrium by monitoring the density and total energy in an isothermal–isobaric ensemble (constant number of molecules, pressure, and temperature ensemble, i.e., NPT). Secondly, once the equilibrium is reached, averaged density values for mixtures with different weight fractions of betaine were determined. The configurations of the studied systems at the end of the equilibrium simulations were collected for the performing diffusion and osmotic pressure calculations.

Molecular Motion and Diffusion of Betaine

The motion of the water and betaine molecules were monitored in a constant number of molecules, volume, and temperature ensemble (NVT) for a duration of 5 ns. The coordinates of each molecule were collected every 10 ps, and then the mean squared displacement (MSD) of the center of mass (CoM) of these molecules was determined over 2.5 ns correlation time according to Eq. (2):

| 3 |

where r is the position vector of CoM of a molecule of betaine or water, N is the total number of molecules, and t is the time. The selected time scale of 10 ps is sufficient to capture the diffusive regime for both molecules. Once in the diffusive regime, the Einstein’s relationship was used to extract the diffusion coefficient D as

| 4 |

Osmotic Pressure

The osmotic pressure of betaine in water was calculated based on the method proposed by Luo and Roux.39 In this method, the simulation box is partitioned into two regions with two semi-impermeable walls. Water can move freely, but betaine molecules are confined between two walls and experience a harmonic force in the form of F = kzez, where k is a force constant, z is the distance of the betaine from the wall, and ez the unit vector in the perpendicular direction to the wall surface. Note that the cutoff distance of this force is set to 6 Å. Using this applied potential, the total force acted on the walls by betaine molecules was determined over a period of 2 ns in an NVT ensemble. The osmotic pressure was calculated according to:

| 5 |

where is the average force exerted to the walls, and A is the surface area of the wall.

Statistical Analysis

We tested the specific hypotheses of the above-mentioned experiments using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post-hoc testing. For all statistical tests, different letters or asterisks (*) indicated on respective graphs denote statistical significance with a p-value lesser than 0.05. Statistical tests were conducted using MINITAB.

Results

CHDH Channel Expression and Colocalization in the PTSM Injured Rat Spinal Cord

We localized the expression of CHDH in PTSM injured spinal cords using IHC for astrocytes (Fig. 1b), neurons, and oligodendrocytes (Fig. S1). Since CHDH is a mitochondrial enzyme, we co-stained cells CHDH and VDAC1 mitochondrial marker to confirm its subcellular localization. Figure 1b shows that syrinxes were primarily surrounded by astrocytes with increased CHDH expression, which reduced with distance from the syrinx. CHDH was visibly expressed in astrocytes and further confirmed by colocalization in the mitochondria with VDAC1 positive staining. The expression level of CHDH in astrocytes appeared to be higher via visualization than in neurons and oligodendrocytes as shown in Figure S1. Thus, rat astrocytes were selected for further in vitro analyses.

CHDH Expression in Rat Astrocytes and HepG2 Cells Under Osmotic Stress

Next, CHDH expression and betaine synthesis from CHDH under different osmotic conditions were studied in vitro using rat astrocytes and HepG2 cells. The ICC results showed that CHDH was expressed at a higher level when HepG2 cells were exposed to hypertonic and hypotonic conditions as compared to isotonic conditions(p < 0.05) (Fig. 2a). When rat astrocytes were incubated with different osmotic conditions, we found similar trends where significantly increased CHDH expression was observed in the hypertonic group as compared to the hypotonic and isotonic groups (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2b). CHDH enzyme colocalized with the mitochondrial protein VDAC1 in both cell lines, as shown in Fig. 2 and Figure S2.

Figure 2.

CHDH expression in (a) HepG2 cells and (b) rat astrocytes. Representative ICC images for CHDH expression (red) colocalized with mitochondrial VDAC1 (green) in isotonic, hypotonic, and hypertonic conditions. Quantification of CHDH expression presented in fluorescence intensity normalized with DAPI fluorescent intensity. Different letters indicate p < 0.05, as determined by the one-factor ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc. n = 3, mean ± SD.

Betaine Synthesis via CHDH Under Osmotic Stress

Further, we investigated potential betaine synthesis by CHDH in both cell lines, (DI TNC1 rat astrocytes and HepG2) under three osmotic conditions. The cells were exposed to isotonic, hypotonic, and hypertonic conditions with and without exogenous choline and incubated overnight to allow cells to respond to these osmotic stress conditions. We analyzed the cell pellets and supernatant samples after small-molecule metabolite extraction for betaine (Fig. 3a) and choline (Fig. 3b) to determine betaine synthesis and choline consumption with response to osmotic stress (Figs. 3c, 3d). From the analysis of betaine in cell pellets, betaine synthesis was significantly (p < 0.05) higher as opposed to isotonic, hypotonic, and control groups. Also, higher choline was detected in cells from the hypertonic group, which was significantly different than other experimental groups indicating the intracellular transfer of choline from the extracellular phase as a response to the hypertonic media for betaine synthesis via CHDH in vitro. From the supernatant analysis, we observed significantly higher levels of betaine in the hypotonic group and the hypertonic group as compared to both the isotonic and control groups (p < 0.05). Moreover, choline consumption evaluated from the supernatant samples was significantly higher in hypotonic and hypertonic groups as compared to isotonic and control groups (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Betaine synthesis by CHDH in a cellular model. Standard curve and extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) of (a) betaine and (b) choline using LC–MS. Endogenous betaine synthesis from choline by CHDH in (c) HepG2 cells and (d) rat astrocytes was observed under different osmotic stress conditions. Different letters indicate statistical significance with p < 0.05, as determined by the one-factor ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc. n = 3, mean ± SD.

The Potential Osmotic Contribution of Betaine via an Experimental Approach

After confirming betaine synthesis via CHDH in DI TNC1 rat astrocytes and HepG2 hepatocytes under osmotic stress, we next decided to try and determine the osmotic contribution of betaine using experimental and simulation approaches. For the experimental approach, we employed a vapor pressure osmometer to analyze the osmolality of betaine solution in water with different concentrations as shown in Fig. 4a. Somewhat expectedly, increased betaine concentration resulted in a linear increase in osmolality in the solution. The considerable increase in the estimated osmotic pressure with betaine concentration in aqueous conditions was reported in Fig. 4b.

Figure 4.

Experimental Determination of the Osmotic contribution of betaine. (a) The osmolality of the betaine solution in water at different concentrations were determined using a vapor pressure osmometer. (b) Osmotic pressure was determined using an empirical correlation.

The Osmotic Contribution of Betaine via a Simulation Approach

Atomistically detailed MD simulations of various mixtures of betaine and water were performed to characterize the osmotic pressure trends with the change of weight fraction of betaine in solution. Here, we conducted a simulated estimation of the density, diffusion, and osmotic pressure of betaine in water at different concentrations (Fig. 5). Figure 5a shows the density of the solution as a function of the betaine weight fraction. The density of the mixture increases as a function of the betaine content. It was observed in Fig. 5b that betaine molecules aggregate and form an almost separated phase at extremely high concentrations.

Figure 5.

(a) Averaged density of betaine in water solution as a function of weight fraction of betaine. (b) 3D visualization of simulation box with mixtures of betaine molecules (red) and water molecules (blue) for three representative weight fractions.

The aggregation of betaine in water can also be confirmed by calculating diffusion coefficients of betaine. Betaine has a lower diffusion coefficient in comparison to water. With aggregation, betaine molecules exhibit limited diffusivity since they show mostly pure betaine diffusion. At lower concentrations of betaine, the molecules diffuse in the water phase, where faster dynamics are expected (see Fig. 6a). Figure 6c shows osmotic pressure as a function of the weight fraction of betaine in water. It can be observed that for both model and experiment, the osmotic pressure increases with betaine content. Moreover, the fitted lines for the model and the experiment have a slope of 0.98 on a log–log scale suggesting a linear relationship between osmotic pressure and weight fraction.

Figure 6.

(a) Diffusion coefficient of water and betaine as a function of weight fraction of betaine. (b) Simulation box snapshot of the mixture with two regions: I (water) and II (betaine + water) used in osmotic pressure calculation. The yellow arrows describe the normal force direction that is applied by betaine molecules on membrane walls. (c) The osmotic pressure as a function of weight fraction of betaine in water in experiments and simulations. The lines show the fitted power-law models for the osmotic pressure. The error bars are not visible as they are smaller than the symbol size.

Discussion

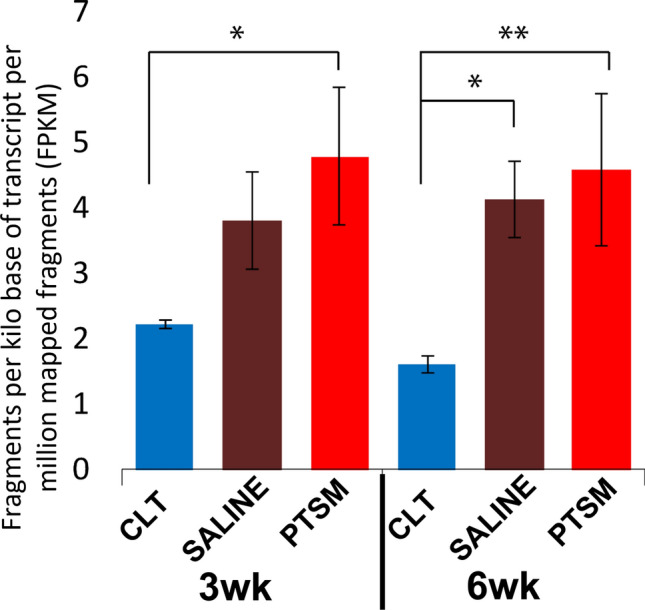

The lack of understanding of basic pathophysiological mechanisms underlying PTSM limits current therapeutic strategies, hence clinicians mostly rely on surgical interventions that result in high failure rates and surgical complications worsening patient quality of life. Understanding molecular events/activities associated with SM pathology is pivotal to strategizing the development of non-surgical treatment options to overcome challenges associated with clinical interventions for SM. In previous studies, the potential involvement of water channels/aquaporins (e.g., AQP1, AQP4),20–22,41 ion channels (e.g., KCC4, Kir4.1), other small molecule channels (e.g., BGT1)41,42 along with upregulation of various osmolytes such as betaine, taurine, and creatine, have been studied. In our study,41 we demonstrated dysregulation of channels BGT1, KCC4, and AQP1 during syrinx expansion in the injured spinal cord, as well as alterations in small molecule osmolytes such as betaine, taurine, and creatine. Betaine acts as a potent osmolyte in biological systems and we retrospectively investigated metabolic pathways associated with this compound by using the transcriptomics data from the previous study.41 Interestingly, we found that CHDH was significantly upregulated in injured spinal cords after 3 and 6 weeks, as shown in Fig. 7. This finding motivated us to further investigate the active role of locally synthesized betaine via CHDH and their osmotic contribution to SM pathogenesis in this newest report. Furthermore, ICC imaging suggested that upregulated CHDH was primarily expressed in the vicinity of syrinxes where reactive astrocytes proliferated (Fig. 1b), as part of a well-known endogenous response mechanism to spinal cord injury (SCI).16 These findings led us to select rat astrocytes for further subsequent in vitro experiments. Since the enzymatic activity of CHDH has been established previously in liver-derived hepatocytes,19,53 we selected the HepG2 cell line as a positive control for our in vitro studies.

Figure 7.

CHDH upregulation via mRNA transcriptomic data obtained from our previous study 41. CHDH expression in control (CTL), Saline, and PTSM injured spinal cords at 3 and 6 wks. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 as determined by the one-factor ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc, n = 4 for CTL, n = 8 for PTSM and Saline. Mean ± SD.

in vitro findings regarding CHDH expression demonstrated that CHDH was upregulated in rat astrocytes and HepG2 hepatocytes when they were exposed to hypertonic and hypotonic extracellular solutions, but not in isotonic solutions (Figs. 2, S2). Also, the colocalization of CHDH with the mitochondrial marker (VDAC1) has been shown here which aligns with the findings in the literature previously.28

Results also demonstrated their ability to synthesize betaine via CHDH when exogenous choline was provided (Figs. 3c, 3d). The increased CHDH expression under osmotic stress indicates that both cell lines are capable of maintaining osmoregulation to overcome an osmotic gradient between the intracellular and extracellular phase by generating osmolyte betaine using substrate choline via upregulation of enzyme CHDH. Betaine biosynthesis via CHDH under osmotic stress in marine animals,11,58 and microorganisms,37,55 has been reported in the literature. Few studies have focused on mammalian responses, however, one notable study showed that CHDH activity was upregulated for betaine synthesis under hypertonic conditions in mouse liver-derived hepatocytes during cell volume homeostasis.24 In another study, reduced levels of betaine were correlated in CHDH knock-out mice, which also escalated schizophrenia-related molecular perturbations that resulted in reduced cognitive performance.44

Interestingly, we found significant betaine levels in supernatant samples from cultures of rat astrocytes and HepG2 hepatocytes from the hypotonic group as compared to the other osmotic conditions (p < 0.05), which indicates betaine synthesis as well as active transport through its corresponding channel, osmoregulatory solute carrier BGT1, into the surrounding media to elevate osmolality of extracellular phase for cell size/volume homeostasis. This aligns with the result of our previous study implicating BGT-1 during cell volume homeostasis.48 Therefore, the findings from this study suggest that hypotonic extracellular osmotic conditions upregulate CHDH and BGT1 to endogenously synthesize betaine and its transport from intracellular to extracellular phase, respectively (Figs. 2, 3C, 3D). Whereas, in extracellular hypertonic conditions, CHDH alone contributed measurably to betaine synthesis to elevate the intracellular osmolality (Figs. 2, 3C, D). Although we have previously studied the cell osmoregulatory activities of betaine and its transporter BGT1, the role of locally synthesized betaine via CHDH and its expression in response to osmotic stressors was previously unexplored for CNS pathologies. Hence, this study provides a unique understanding of locally synthesized betaine via CHDH in astrocytes under osmotic stress and suggesting a potential involvement in SM pathophysiology. It is worth highlighting that general attention on betaine and CHDH in the last decade has increased greatly due to their involvement in various other diseases and pathologies 53 such as obesity, diabetes, vascular diseases, as well as fatty liver conversion due to alcohol consumption,36 homocystinuria,62 hyperhomocysteinemia,25 Alzheimer's disease,8 obesity,13 schizophrenia,44 autism,27 cancer,63 mainly due to its methyl donor and antioxidant properties. Despite also acting as a potent osmolyte, its osmolyte effects in vivo have not been fully explored especially concerning fluid-associated pathologies like SM.

With data in hand suggesting in vivo CHDH upregulation coinciding with PTSM and in vitro confirmation of betaine synthesis via CHDH, we were interested to determine and quantify the capability of betaine to create biologically relevant osmotic impact using both experimental and in silico approaches. An experimental approach using an osmometer demonstrated that betaine was capable of directly increasing osmotic pressure as the concentration of betaine increased (Fig. 4) indicates the osmotic potency of betaine molecules in aqueous conditions.

To study how betaine content affects the characteristic properties of the modeled mixture, density values were obtained via averaging density from a 2 ns long NPT simulation of a previously relaxed system (see Fig. 5a). Apart from the evident increase of mixture density with betaine content, the density values reach plateau values at ρ = 1.03 ± 0.02 g/cm3 at lower weight fractions. It is due to the very small number of betaine molecules that no longer quantitatively contribute to the overall density. Another property of the mixture was the solubility of betaine with its weight fraction increase in water. When dispersing betaine at different concentrations, it was observed that increasing the concentration leads to phase separation as seen in Fig. 5b.

The MSD values were obtained from the centers of mass coordinates for 5 ns long NVT simulation after relaxation (Eq. 3). Then, the diffusion coefficients were determined using Eq. 4 in the diffusive regime of the MSD plots. In Fig. 6a it can be observed that the diffusion coefficients of betaine start and remain at a constant value up to w = 0.05, and further decrease rapidly with an increase of the weight fractions. The diffusion coefficient dramatic decrease at high betaine content is in agreement with phase separation starting to occur in the mixtures (Fig. 5b). This phenomenon likely occurs due to betaine-betaine interactions becoming more favorable with an increase of betaine concentration and the inherent entropic effect of large molecules. Both processes contribute to slower dynamics and betaine molecules aggregate and create water-rich and betaine-rich regions. Molecules in the betaine phase are restricted in movement because of their large size and, hence, lower mobility than water. As water molecules are of much smaller size, they show higher values of diffusion throughout the tested weight fractions of betaine in mixtures. Note that at a high concentration of betaine, the diffusion coefficient of water also slightly decreases. Once density and diffusion coefficients were collected to characterize the mixtures, the osmotic pressure calculations were performed at T = 300 K and P = 1 atm. First, the simulation box was extended to place harmonic wall membranes and relaxed for another 2 ns to reach a steady state. Then, the weight fraction of betaine in water was adjusted accordingly to the volume within the walls. The normal force exerted by betaine molecules on the walls was obtained as an average of forces collected every 10 ps over 2 ns time. The schematic of force working on harmonic walls is represented in Fig. 6b. The osmotic pressure values were calculated from the force data using Eq. 5. The increase of osmotic pressure values with weight fraction of betaine in water is shown in Fig. 6c. The results resemble the behavior that was observed in experiments.

Our simulation approach confirmed these experimental results and suggested thermodynamic underpinnings for the observed data (Fig. 6c). The experimental and simulation data were fitted to power-law model and showed a linear behavior. Even though the simulation overestimated the osmotic pressure of betaine in water, the predicted trend remained similar to those seen experimentally. It is important to note that the force field parameters that were utilized in this work are determined for pure liquids. Therefore, the difference between the simulation data and experiments, which we speculate is due to the force field parameters, is manifested in the slope (on linear scale) of osmotic pressure versus weight fraction. Moreover, obtaining the osmotic pressure at concentrations lower than a weight fraction of 0.017 led to incomplete data to enable statistical normal force calculations. In order to achieve an accurate result at very low weight fractions, a significant increase in the number of molecules is required which is computationally challenging. Despite these limitations, the linear increase of osmotic pressure with betaine concentration in water was observed in both experimental and simulation approaches.

Based on these results in whole, we can speculate that following PTSM injury cells closest to the syrinx locally synthesized betaine via CHDH in an attempt to counteract osmotic disturbances. Furthermore, the responsible cell population is likely mainly reactive astrocytes adjacent to syrinxes (Fig. 1). Importantly, our newest observations align with previously reported results concerning betaine osmoregulation with significant CHDH activity in other organs of the body such as the liver and kidney.3,15,19,53,57 Also, our previous results concerning the CNS using in vivo41 and in vitro models48 along with the current findings support the potential involvement of betaine regulation in SM pathophysiology. The imbalance of betaine regulation processes in the locally injured area due to primary injury and secondary insults, thereafter, could contribute to excess fluid accumulation in the spinal cord tissue and syrinx formation and expansion over time. Our results continue to suggest that betaine osmoregulation is utilized mainly by reactive astrocytes adjacent to an injury area and is likely used as a response to protect themselves from a disturbed osmotic environment at the expense of excess fluid accumulation at the injury site. To further investigate the effect of synthesized betaine via CHDH on syrinx development, a comprehensive study using CHDH inhibitors or knockout controls for CHDH with a PTSM animal model would be a pivotal next step in future experimentation. Moreover, the other known and unknown molecular and cellular events during secondary insult post-SCI might create a desirable environment for fluid/water to accumulate in the injured spinal cord tissue hence further investigation is required to reveal these molecular and cellular events in the SM environment.

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated that the CHDH enzyme was upregulated in spinal cord tissue 6 weeks post-injury in a rat PTSM model. CHDH expression was mainly observed in the mitochondria of reactive astrocytes adjacent to the syrinx. in vitro work further confirmed upregulation of CHDH in astrocytes exposed to osmotic stress, either hypotonic or hypertonic, indicating the ability of astrocytes to participate in osmoregulation events. When exogenous choline was provided as a substrate to astrocytes under osmotic stress, betaine synthesis via choline was observed, which attests to the osmoprotectant role of betaine in biological systems. We further evaluated the osmotic contribution of betaine in water using experimental and simulation approaches confirming the ability of betaine to increase osmotic pressure. The findings from this study demonstrate the osmotic contribution of locally synthesized betaine and implicate the importance of betaine osmoregulation in SM pathophysiology. However, extensive cellular and molecular work using additional in vitro and in vivo studies are required in the future to further reveal syrinx formation/expansion mechanisms as tied to fluid osmoregulation. We speculate that this information will help guide the development of new non-surgical treatment options to overcome the challenges associated with the most common surgical treatments for SM to improve outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Figure S1. CHDH expression in neurons and oligodendrocytes from PTSM injured rat spinal cords. CHDH expression colocalized with VDAC1 in neurons (Tuj1+) and oligodendrocytes (RIP+) from injured PTSM spinal cords. The asterisk (*) indicates syrinx. (TIF 32,872 kb)

Figure S2. CHDH expression. Representative ICC images (with each channel shown separately) for CHDH expression (red) colocalized with mitochondrial VDAC1 (green) in isotonic, hypotonic, and hypertonic conditions. (TIF 14,104 kb)

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported partially by Column of Hope, Conquer Chiari, and the University of Akron. The authors would like to thank Ms. Delora Grace Allen for their assistance in cell culture and sample preparation. We thank Dr. Ravindra Gudneppenvar and Dr. Michael Konopka for their support for the use of a confocal microscope. Also, we would like to acknowledge Dr. Mahmoud Farrag and Dr. Hannah J Baumann for their guidance and feedback throughout the research project.

Author Contributions

DDP and NDL planned experimental designs, DDP executed experiments, cell culture, IHC, ICC, images acquisition, conducted image analysis, and data analysis, prepared the manuscript. DL and FK conducted a simulation and prepared a manuscript for that part. SRA assisted in cell culture and maintenance that are used in in vitro studies. NDL, LPS, DDP, DL, and FK revised the manuscript and participated in data discussion and data interpretation. DDP and NDL participated in the production of the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Animal Study

All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed and approved by University of Akron Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abri S, Attia R, Pukale DD, Leipzig ND. Modulatory contribution of oxygenating hydrogels and polyhexamethylene biguanide on the antimicrobial potency of neutrophil-like cells. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022;8(9):3842–3855. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.2c00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal A, Shetty M, Pandit L, Shetty L, Srikrishna U. Post-traumatic syringomyelia. Indian J. Orthop. 2007;41:398–400. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.37006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlow P, Marchbanks RM. The effects of inhibiting choline dehydrogenase on choline metabolism in mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1985;34:3117–3122. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90156-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayly CI, et al. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:5179–5197. doi: 10.1021/ja00124a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brodbelt AR, Stoodley MA. Post-traumatic syringomyelia: a review. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2003;10(4):401–408. doi: 10.1016/S0967-5868(02)00326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cánovas D, Vargas C, Csonka LN, Ventosa A, Nieto JJ. Osmoprotectants in Halomonas elongata: High-affinity betaine transport system and choline-betaine pathway. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:7221–7226. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7221-7226.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cánovas D, Vargas C, Csonka LN, Ventosa A, Nieto JJ. Synthesis of glycine betaine from exogenous choline in the moderately halophilic bacterium Halomonas elongata. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998;64:4095–4097. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.10.4095-4097.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chai GS, et al. Betaine attenuates Alzheimer-like pathological changes and memory deficits induced by homocysteine. J. Neurochem. 2013;124:388–396. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheatham TE, Cieplak P, Kollman PA. A modified version of the cornell et al. force field with improved sugar pucker phases and helical repeat. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1999;16:845–862. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1999.10508297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig SAS. Betaine in human nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;80(3):539–49. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delgado-Gaytán MF, Gómez-Jiménez S, Gámez-Alejo LA, Rosas-Rodríguez JA, Figueroa-Soto CG, Valenzuela-Soto EM. Effect of salinity on the synthesis and concentration of glycine betaine in osmoregulatory tissues from juvenile shrimps Litopenaeus vannamei. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A. 2020;240:110628. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.110628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrag M, Pukale D, Leipzig N. Micro-computed tomography utility for estimation of intraparenchymal spinal cord cystic lesions in small animals. Neural Regen. Res. 2021;16:2293–2298. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.310690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao X, Zhang H, Guo XF, Li K, Li S, Li D. Effect of betaine on reducing body fat—a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2480. doi: 10.3390/nu11102480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodhead LK, MacMillan FM. Measuring osmosis and hemolysis of red blood cells. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2017;41(2):298–305. doi: 10.1152/advan.00083.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossman EB, Hebert SC. Renal inner medullary choline dehydrogenase activity: characterization and modulation. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 1989;256(1):F107–F112. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.1.F107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ham TR, Leipzig ND. Biomaterial strategies for limiting the impact of secondary events following spinal cord injury. Biomed. Mater. 2018;13:024105. doi: 10.1088/1748-605X/aa9bbb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ham TR, Pukale DD, Hamrangsekachaee M, Leipzig ND. Subcutaneous priming of protein-functionalized chitosan scaffolds improves function following spinal cord injury. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2020;110:110656. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2020.110656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamrangsekachaee M, Baumann HJ, Pukale DD, Shriver LP, Leipzig ND. Investigating mechanisms of subcutaneous preconditioning incubation for neural stem cell embedded hydrogels. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022;5(5):2176–84. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.2c00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haubrich DR, Gerber NH. Choline dehydrogenase. Assay, properties and inhibitors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1981;30:2993–3000. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(81)90265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemley SJ, Bilston LE, Cheng S, Chan JN, Stoodley MA. Aquaporin-4 expression in post-traumatic syringomyelia. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:1457–1467. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemley SJ, Bilston LE, Cheng S, Chan JN, Stoodley MA. Aquaporin-4 expression in post-traumatic syringomyelia. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:1457–1467. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hemley SJ, Bilston LE, Cheng S, Stoodley MA. Aquaporin-4 expression and blood-spinal cord barrier permeability in canalicular syringomyelia: laboratory investigation. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2012;17:602–612. doi: 10.3171/2012.9.SPINE1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hockney, R.W., and J.W. Eastwood. Computer Simulation Using Particles. crc Press. 1988 [cited 2021 Jun 16]. Available from: https://books.google.com/books/about/Computer_Simulation_Using_Particles.html?id=nTOFkmnCQuIC.

- 24.Hoffmann L, et al. Osmotic regulation of hepatic betaine metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. 2013;304(9):G835–G846. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00332.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoorn VS, Cmm L. Comparison of homocysteine-lowering drugs. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoover WG. Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A. 1985;31:1695–1697. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang F, et al. Betaine ameliorates prenatal valproic-acid-induced autism-like behavioral abnormalities in mice by promoting homocysteine metabolism. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019;73:317–322. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang S, Lin Q. Functional expression and processing of rat choline dehydrogenase precursor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;309:344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jakalian A, Bush BL, Jack DB, Bayly CI. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC Model: I. Method. J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:132–146. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(20000130)21:2<132::AID-JCC5>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jakalian A, Jack DB, Bayly CI. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: II. Parameterization and validation. J. Comput. Chem. 2002;23:1623–1641. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kempson SA, Vovor-Dassu K, Day C. Betaine transport in kidney and liver: use of betaine in liver injury. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2013;32(7):32–40. doi: 10.1159/000356622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kempson SA, Zhou Y, Danbolt NC. The betaine/GABA transporter and betaine: roles in brain, kidney, and liver. Front. Physiol. 2014;5:159. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khabaz F, Mani S, Khare R. Molecular origins of dynamic coupling between water and hydrated polyacrylate gels. Macromolecules. 2016;49:7551–7562. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b00938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiil F. Kinetic model of osmosis through semipermeable and solute-permeable membranes. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2003;177:107–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lang F. Mechanisms and significance of cell volume regulation. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007;26:613S–623S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lever M, Slow S. The clinical significance of betaine, an osmolyte with a key role in methyl group metabolism. Clin. Biochem. 2010;43:732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindberg Yilmaz J, Bülow L. Enhanced stress tolerance in Escherichia coli and Nicotiana tabacum expressing a betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase/choline dehydrogenase fusion protein. Biotechnol. Prog. 2002;18:1176–1182. doi: 10.1021/bp020057k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Z, et al. Betaine/GABA transporter-1 (BGT-1) deficiency in mouse prevents acute liver failure in vivo and hepatocytes apoptosis in vitro. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2020;1866:165634. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.165634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo Y, Roux B. Simulation of osmotic pressure in concentrated aqueous salt solutions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:183–189. doi: 10.1021/jz900079w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacKerell AD, et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohrman AE, et al. Spinal cord transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis after excitotoxic injection injury model of syringomyelia. J. Neurotrauma. 2017;34:720–733. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Najafi E, Stoodley MA, Bilston LE, Hemley SJ. Inwardly rectifying potassium channel 4.1 expression in post-traumatic syringomyelia. Neuroscience. 2016;317:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nyyssölä A, Leisola M. Actinopolyspora halophila has two separate pathways for betaine synthesis. Arch. Microbiol. 2001;176:294–300. doi: 10.1007/s002030100325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohnishi T, et al. Investigation of betaine as a novel psychotherapeutic for schizophrenia. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:432–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parrinello M, Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981;52:7182–7190. doi: 10.1063/1.328693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plimpton S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995;117:1–19. doi: 10.1006/jcph.1995.1039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Price DJ, Brooks CL. A modified TIP3P water potential for simulation with Ewald summation. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;121:10096–10103. doi: 10.1063/1.1808117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pukale DD, et al. Osmoregulatory role of betaine and betaine/γ-aminobutyric acid transporter 1 in post-traumatic syringomyelia. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021;12:3567–3578. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pukale, D.D. The Role of Betaine Focused Fluid Osmoregulation in Syringomyelia Post Spinal Cord Injury. [University of Akron]: University of Akron, 2022. Available from: http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=akron1649984964685017.

- 50.Pukale DD, Farrag M, Leipzig ND. Detection of locomotion deficit in a post-traumatic syringomyelia rat model using automated gait analysis technique. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0252559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rasouli M. Basic concepts and practical equations on osmolality: Biochemical approach. Clin. Biochem. 2016;49:936–941. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rusbridge C, Greitz D, Iskandar BJ. Syringomyelia: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2006;20:469–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2006.tb02884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salvi F, Gadda G. Human choline dehydrogenase: Medical promises and biochemical challenges. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013;537:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schofield Z, Reed MA, Newsome PN, Adams DH, Günther UL, Lalor PF. Changes in human hepatic metabolism in steatosis and cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2685–2695. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i15.2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scholz A, Stahl J, de Berardinis V, Müller V, Averhoff B. Osmotic stress response in Acinetobacter baylyi: identification of a glycine-betaine biosynthesis pathway and regulation of osmoadaptive choline uptake and glycine-betaine synthesis through a choline-responsive BetI repressor. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2016;8:316–322. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shinoda W, Shiga M, Mikami M. Rapid estimation of elastic constants by molecular dynamics simulation under constant stress. Phys. Rev. B. 2004;69:134103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.69.134103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slow S, Lever M, Chambers ST, George PM. Plasma dependent and independent accumulation of betaine in male and female rat tissues. Physiol. Res. 2009;58:403–410. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Treberg JR, Driedzic WR. The accumulation and synthesis of betaine in winter skate (Leucoraja ocellata) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A. 2007;147:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang J, Wolf RM, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA, Case DA. Development and testing of a general Amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wargo MJ. Choline catabolism to glycine betaine contributes to pseudomonas aeruginosa survival during murine lung infection. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e56850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wettstein M, Weik C, Holneicher C, Häussinger D. Betaine as an osmolyte in rat liver: metabolism and cell-to-cell interactions. Hepatology. 1998;27:787–793. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilcken DEL, Dudman NPB, Tyrrell PA. Homocystinuria due to cystathionine β-synthase deficiency-The effects of betaine treatment in pyridoxine-responsive patients. Metabolism. 1985;34:1115–1121. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(85)90156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao G, et al. Betaine in inflammation: mechanistic aspects and applications. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1070. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou Y, et al. The betaine-GABA transporter (BGT1, slc6a12) is predominantly expressed in the liver and at lower levels in the kidneys and at the brain surface. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2012;302:9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00464.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. CHDH expression in neurons and oligodendrocytes from PTSM injured rat spinal cords. CHDH expression colocalized with VDAC1 in neurons (Tuj1+) and oligodendrocytes (RIP+) from injured PTSM spinal cords. The asterisk (*) indicates syrinx. (TIF 32,872 kb)

Figure S2. CHDH expression. Representative ICC images (with each channel shown separately) for CHDH expression (red) colocalized with mitochondrial VDAC1 (green) in isotonic, hypotonic, and hypertonic conditions. (TIF 14,104 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.