Abstract

Advances in structural analysis by cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography have revealed the tertiary structures of various chromatin-related proteins, including transcription factors, RNA polymerases, nucleosomes, and histone chaperones; however, the dynamic structures of intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) in these proteins remain elusive. Recent studies using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), together with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, are beginning to reveal dynamic structures of the general transcription factor TFIIH complexed with target proteins including the general transcription factor TFIIE, the tumor suppressor p53, the cell cycle protein DP1, the DNA repair factors XPC and UVSSA, and three RNA polymerases, in addition to the dynamics of histone tails in nucleosomes and histone chaperones. In complexes of TFIIH, the PH domain of the p62 subunit binds to an acidic string formed by the IDR in TFIIE, p53, XPC, UVSSA, DP1, and the RPB6 subunit of three RNA polymerases by a common interaction mode, namely extended string-like binding of the IDR on the positively charged surface of the PH domain. In the nucleosome, the dynamic conformations of the N-tails of histones H2A and H2B are correlated, while the dynamic conformations of the N-tails of H3 and H4 form a histone tail network dependent on their modifications and linker DNA. The acidic IDRs of the histone chaperones of FACT and NAP1 play important roles in regulating the accessibility to histone proteins in the nucleosome.

Keywords: NMR, Nucleosome, Intrinsically disordered protein, General transcription factor, TFIIH

Introduction

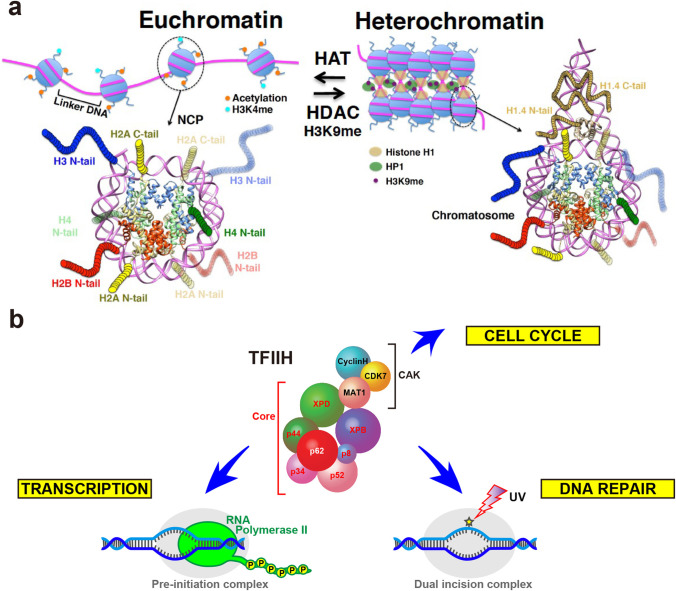

In eukaryotes, there are two classes of chromatin structure: gene-active euchromatin and gene-inactive heterochromatin, as outlined in Fig. 1a. In euchromatin, DNA is exposed to solvent, enabling it to access various factors including transcription factors and RNA polymerases; in heterochromatin, in contrast, DNA is compactly folded into tandem arrays of nucleosomes. Each nucleosome, the repeating unit of chromatin, consists of a nucleosome core particle (NCP) comprising two histone H2A/H2B heterodimers and one (H3/H4)2 tetramer wrapped around by about 146-bp DNA (Luger et al. 1997), and several lengths of linker DNA. The N-terminal tail (N-tail) of each histone is an intrinsically disordered region (IDR) and subject to post-translationally modifications, such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, which are responsible for epigenetic regulations. In euchromatin, most N-tail IDRs of histones H3 and H4 are acetylated by histone acetyl transferases (HATs) and their interactions with DNA are weakened, while in heterochromatin, almost all histone N-tail IDRs are deacetylated by histone deacetylase (HDAC) and lysine 9 of histone H3 tail IDR is specifically methylated (H3K9me). This modification is a target of heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) containing N-tail and central IDRs, which bridges neighboring nucleosomes with H3K9me to form a condensed state of nucleosomes. Linker histone H1 containing N- and C-tail IDRs further binds to each nucleosome to form chromatosome (Thoma and Koller 1977; Simpson 1978) (Fig. 1a). To activate gene expression, transcription activators bind to specific enhancers, where they recruit coactivators with HATs by using their IDRs. In addition, histone chaperones loosen the chromatin structure by using their IDRs, leading to assemblies of general transcription factors and RNA polymerase II, which also contains IDRs from two subunits, RPB1 and RPB6. To form heterochromatin, transcription repressors bind to specific silencers, where they recruit corepressors with HDACs by using their IDRs and the histone H3K9 methylase. Lastly, the telomeres at the ends of each chromosome adopt a different type of heterochromatin formed by the telomeric protein complex shelterin, which includes TRF1, TRF2, and RAP1.

Fig. 1.

Euchromatin and heterochromatin. a Structures of the nucleosome core particle (NCP), chromatosome, and histone tails. The NCP and chromatosome structures are modified from PDB ID 2CV5 and 7K5Y, respectively. H1.4, H2A, H2B, H3, H4, and DNA are colored tan, yellow, red, blue, green, and orchid, respectively. Colored circular chains denote the histone tails, which are not observed in the structure and are modeled without experimental data. The N-tails of H1.4, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, and the C-tails of H1.4 and H2A protrude from the NCP and chromatosome. Orange, cyan, tan, green, and purple ovals indicate acetylation, H3K4me (methylation at Lys4 of histone H3), histone H1, HP1, and H3K9me (methylation at Lys9 of histone H3), respectively. H3K9me and HP1 binding are critical for the formation of transcriptionally inactive chromatin (heterochromatin), while lysine acetylation of histone tails and H3K4me are enriched in transcriptionally active chromatin (euchromatin). HAT (histone acetyltransferase) and HDAC (histone deacetylase) regulate chromatin structure. b Roles and subunit composition of the multifunctional general transcription factor TFIIH

By using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) coupled with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in some cases, we have obtained structures of the transcription activators Myb (Ogata et al. 1992, 1994, 1995, 1996; Tanikawa et al. 1993; Morikawa et al. 1995; Zheng et al. 1996; Oda et al. 1997a, 1997b; Sasaki et al. 2000) and ATF2 (Nagadoi et al. 1999); the repressor REST/NRSF (Nomura et al. 2005; Higo et al. 2011); the general transcription factor TFIIE (Okuda et al. 2000, 2004, 2008); the telomeric proteins TRF1 (Nishikawa et al. 1998, 2001; Hanaoka et al. 2005), TRF2 (Hanaoka et al. 2005), and RAP1 (Hanaoka et al. 2001); and the prokaryote transcription factors PhoB (Okamura et al. 2000, 2007; Yamane et al. 2008, 2010), OmpR (Okamura et al. 2000), and PurR (Nagadoi et al. 1995). Such nuclear protein structures are useful in the design of drug candidates to treat several diseases. In particular, overexpression of REST/NRSF, which mediates transcriptional repression by recruiting the corepressor mSin3 via REST N-tail IDR together with HDAC and the histone H3K9 methylase, is related to several neuropathies. Based on the complex structure of mSin3 bound to the N-terminal repressor IDR domain of REST/NRSF (Nomura et al. 2005), we have developed several compounds (Ueda et al. 2017; Kurita et al. 2018; Hayami et al. 2021) that inhibit the interaction of REST/NRSF with mSin3 to treat diseases caused by REST/NRSF upregulation, such as medulloblastoma (Kurita et al. 2018), neuropathic pains and fibromyalgia (Ueda et al. 2017).

More recently, we have been using NMR and MD simulations to probe the dynamic structures of the IDRs of chromatin-related proteins that cannot be solved by X-ray crystallography or cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM). Here, we summarize our studies on the dynamic structures of (1) the general transcription factor TFIIH during interactions with various target proteins via their IDRs; (2) the heterochromatin-related proteins Chp1 and HP1 containing IDRs; (3) histone N-tail IDRs in NCPs, nucleosomes, and chromatosomes; and (4) the histone chaperones FACT and NAP1, both of which are responsible for chromatin formation by using their IDRs.

Polymorphic functions of TFIIH

The general transcription factor TFIIH is a multifunctional macromolecular protein complex (molecular mass ~ 500 kDa) involved not only in transcription (Conaway and Conaway 1989) but also in DNA repair (Schaeffer et al. 1993) and the cell cycle (Roy et al. 1994) (Fig. 1b). Seven of the 10 TFIIH subunits — XPB, XPD, p62, p52, p44, p34, and p8/TTDA — form the Core subcomplex (Fig. 2a). The other three subunits — CDK7, Cyclin H, and MAT1 —form the cdk-activating kinase (CAK) subcomplex. These two subcomplexes function cooperatively or individually, depending on the TFIIH recruiting site. Three of the TFIIH subunits have enzymatic activity. The Core subunits XPB and XPD possess DNA-dependent ATPase activity: the DNA translocase activity (3′ → 5′) of XPB and the DNA helicase activity (5′ → 3′) of XPD are required for the formation of a DNA bubble around transcription start sites and damaged sites (Feaver et al. 1993), where they scan for a transcription start site (Murakami et al. 2015) and perform lesion verification (Sugasawa et al. 2009). Mutations in the genes encoding XPB, XPD, and p8/TTDA cause autosomal recessive disorders, xeroderma pigmentosum, Cockayne syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy (Lehmann 2003). The CAK subunit CDK7 has kinase activity, which is used for phosphorylating the C-terminal IDR domain of RNA polymerase II and other transcription factors in order to facilitate transition from transcription initiation to elongation (Lu et al. 1992). In nucleotide excision repair (NER), the CAK subcomplex dissociates from the Core subcomplex and is not involved in the repair process (Svejstrup et al. 1995); however, it participates in cell cycle control (Fesquet et al. 1993; Poon et al. 1993).

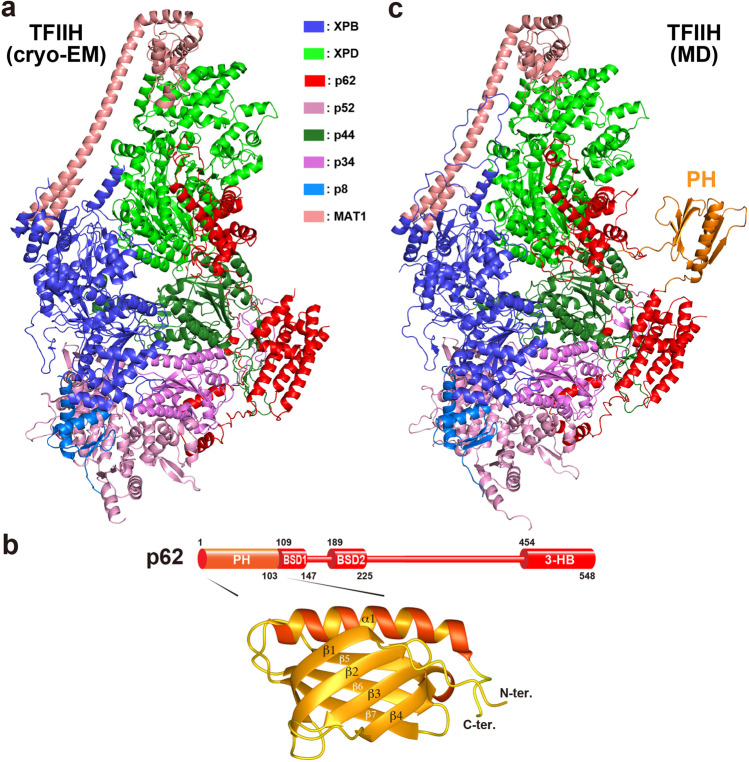

Fig. 2.

Structure of the Core of human TFIIH. a Cryo-EM structure of human TFIIH [PDB ID 6NMI]. b Domain organization of the p62 subunit of human TFIIH. PH, pleckstrin homology domain; BSD (BTF2-like transcription factors, synapse-associated proteins and DOS2-like proteins) domain; 3-HB, 3-helix bundle. c MD simulation model of human TFIIH built by using a combination of cryo-EM [PDB ID 6NMI] and NMR [PDB ID 7BUL] structures

The N-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of the Core subunit p62 is important in recruiting TFIIH to transcription start sites and sites of DNA damage (Fig. 2b, c). It contains ~ 100–120 amino acids and comprises a β barrel structure formed by two crossed antiparallel β sheets, consisting of four and three β strands, and a C-terminal α-helix that caps the β barrel and stabilizes it (Shaw 1996) (Fig. 2b). Although PH domains are well known to bind phosphoinositide (Hirata et al. 1998), the p62 PH domain binds to specific transcription or NER factors that guide TFIIH to the site requiring transcription or repair. A hallmark of the interactions of the p62 PH domain is that all of its target proteins bind through a highly acidic IDR (Fig. 3).

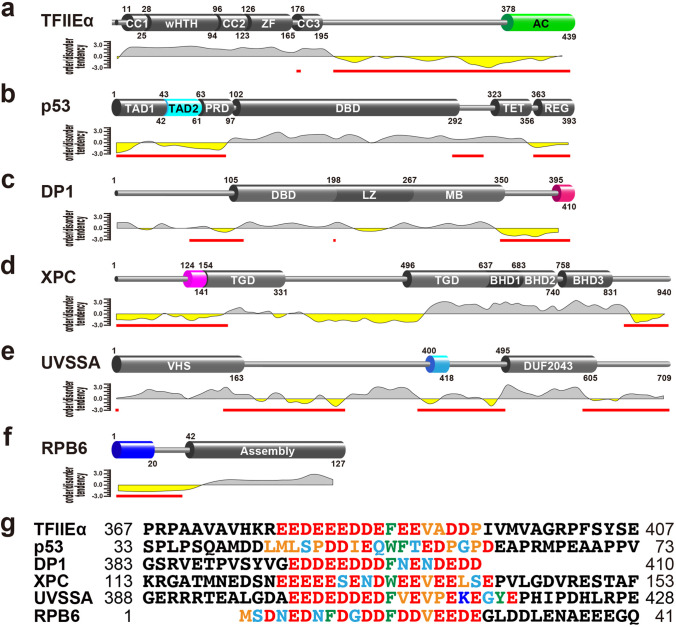

Fig. 3.

TFIIH p62 target proteins. a–f Domain organization of target proteins. p62 PH domain-binding regions are highlighted in color. The ordered/disordered tendency and predicted IDRs (red bars), calculated by IDEAL (Fukuchi et al. 2012), are indicated below. a TFIIEα. CC, coiled-coil domain; wHTH, winged helix-turn-helix domain; ZF, zinc-finger domain; AC, acidic domain. b p53. TAD, transactivation domain; PRD, proline-rich domain; DBD, DNA-binding domain; TET, tetramerization domain; REG, regulatory domain. c DP1. DBD, DNA-binding domain; LZ, leucine zipper domain; MB, marked box domain. d XPC. TGD, transglutaminase-homology domain; BHD, β-hairpin domain. e UVSSA. VHS, (Vps-27, Hrs, and STAM) domain; DUF2043 (domain of unknown function) domain. f RPB6. Assembly, assembly domain. g Amino acid sequence alignment of the binding regions of TFIIH p62 target proteins

Among the PH domains of p62 in many eukaryotic organisms, the structures of human and budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) have been extensively examined for the past two decades. Structures of the PH domain of S. cerevisiae Tfb1 have been determined in complex with various target proteins (Di Lello et al. 2006; Langlois et al. 2008; Mas et al. 2011; Lafrance-Vanasse et al. 2012, 2013; Chabot et al. 2014; Cyr et al. 2015; Lecoq et al. 2017), as well as in its free form (Di Lello et al. 2005) by NMR; in this review, however, we focus on the PH domain of human p62. Human p62 comprises 548 residues arranged in four structural domains: an N-terminal PH domain; two BSD (BTF2-like transcription factors, synapse-associated proteins, and DOS2-like proteins) domains, BSD1 and BSD2; and a C-terminal three-helix bundle (Fig. 2b). The initial solution structure of the isolated PH domain of human p62 was solved by NMR (Gervais et al. 2004).

Interaction of TFIIH with TFIIEα

The general transcription factor TFIIE is a heterodimer consisting of α and β subunits that recruits TFIIH during the last step of formation of the preinitiation complex and regulates the enzymatic activities of TFIIH. TFIIEα binds strongly to p62 (Yamamoto et al. 2001) and the long C-terminal acidic IDR of TFIIEα is essential for its interaction with TFIIH from the crowded preinitiation complex (Ohkuma et al. 1995). The specific binding of the C-terminal acidic domain of human TFIIEα (Fig. 3a, g) to the N-terminal PH domain of p62 has been elucidated through solution structures of the isolated acidic domain (Fig. 4a) and its complex bound to the p62 PH domain (Fig. 4b) (Di Lello et al. 2008; Okuda et al. 2008). The acidic domain adopts a globular structure consisting of two β-strands and three α-helices. The core structures of both the TFIIEα acidic domain and the p62 PH domain remain unchanged in their free and complexed states; however, the N-terminal acidic IDR of the TFIIEα acidic domain wraps around a basic surface of the p62 PH domain, forming an extended string like conformation, in the complexed state. This unique arrangement is here named an “acidic string IDR.”

Fig. 4.

Structures of the free form of target proteins and their complexes with the TFIIH p62 PH domain. a–g Twenty best NMR structures, h Model of the NMR structure ensembles represented as a ribbon diagram. a, b TFIIEα acidic domain (green) [PDB ID 2RNQ] and its complex with p62 PH domain [PDB ID 2RNR]. c Complex of p53 TAD2 (cyan) with p62 PH domain [PDB ID 2RUK]. d Complex of DP1 acidic string (deep pink) with p62 PH domain [PDB ID 5GOW]. e Complex of XPC acidic string (magenta) with p62 PH domain [PDB ID 2RVB]. f Complex of UVSSA acidic string (sky blue) with p62 PH domain [PDB ID 5XV8]. g, h RPB6 (blue) [PDB ID 7DTH] and its complex with p62 PH domain [PDB ID 7DTI]. The TFIIH p62 PH domain is colored orange. For clarity, some N- and C-terminal residues of XPC and UVSSA have been omitted

The positively charged surface of the PH domain is formed by multiple lysine (Lys18, Lys19, Lys51, Lys54, Lys60, Lys62, and Lys104) and arginine (Arg16 and Arg105) residues (Fig. 5a). Notably, most of these positive surface-forming basic residues make extensive electrostatic interactions with nine consecutive acidic residues and two subsequent acidic residues from the acidic string IDR, together with three acidic residues from the C-tail of the acidic domain (Fig. 5a, c). The binding surface of the PH domain possesses two shallow pockets, “pocket 1” and “pocket 2” (Fig. 5b). Pocket 1 on the second β-sheet is formed by Lys54, Ile55, Ser56, Lys60, Gln64, Leu65, Gln66, and Asn76, while pocket 2 is formed by Gln53 and Ile55 on the β5 strand and Lys93 and Gln97 on the α1 helix. Phe387 and Val390 in the acidic string IDR are accommodated in pockets 1 and 2, respectively (Fig. 5i). In pocket 1, Phe387 of the acidic string IDR makes hydrophobic interactions with the aliphatic portions of Lys54 and Lys60, and amino-aromatic interactions (Burley and Petsko 1986) with the side-chain amino groups of Gln64, Gln66, and Asn76 of the PH domain. Val390 of the acidic string IDR in pocket 2 makes extensive hydrophobic contacts with Ile55 and the aliphatic regions of Gln53, Lys93, and Gln97 of the PH domain. The insertion of these two residues is particularly crucial, because the binding activity of TFIIEα is severely reduced when Phe387 is replaced by alanine or glutamate, and Val390 is replaced by alanine or lysine (Okuda et al. 2008).

Fig. 5.

Binding surface of the TFIIH p62 PH domain. a, b Free form. a Basic residues that make electrostatic interactions with a target protein are marked by dotted lines. b Residues that construct pockets 1 and 2 are shown. c–n Complex of the p62 PH domain with a target protein. The binding surface is shown with c–h and without i–n electrostatic potential. The target protein is represented as a ribbon diagram (colored as in Fig. 4) with side-chains of acidic amino acids c–h and pocket-inserted amino acids i–n. TFIIEα c, i; p53 d, j; DP1 e, k; XPC f, l; UVSSA g, m; RPB6 h, n. In d, pS and pT indicate phosphorylated serine and threonine residues, respectively

Interaction of TFIIH with the tumor suppressor p53

The tumor suppressor protein p53 has a transcription activation domain (TAD) in the N-terminal region (Fig. 3b, g). TADs consist of two homologous subdomains, TAD1 and TAD2, which are IDRs, although they both hold helical propensity (Lee et al. 2000). The complex structures of TAD IDRs bound to various binding partners, determined by NMR and X-ray crystallography (Kussie et al. 1996; Bochkareva et al. 2005; Di Lello et al. 2006; Popowicz et al. 2008; Feng et al. 2009; Rajagopalan et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2010; Rowell et al. 2012; Ha et al. 2013; Krois et al. 2016; Ecsédi et al. 2020) reveal a common interaction mode of TAD IDR, involving the formation of an amphipathic α-helix in a coupled folding and binding manner. This has also been observed in the complex of unphosphorylated human p53 TAD2 IDR bound to the PH domain of yeast Tfb1 (Di Lello et al. 2006). Interestingly, however, phosphorylated human p53 TAD2 IDR forms an extended string-like conformation when bound to the human p62 PH domain (Okuda and Nishimura 2014) (Fig. 4c).

Human p53 TAD IDR contains seven serine and two threonine residues within residues 1–61, and their phosphorylation has been implicated in the activation of p53 upon cellular stress (Sakaguchi et al. 2000). Regarding TAD2 IDR, phosphorylation of Ser46 and Thr55 is involved in regulating the apoptotic activity of p53 (Oda et al. 2000) and in G1 cell cycle progression (Li et al. 2004), respectively. Unphosphorylated TAD2 IDR does not form a stable complex with the PH domain in solution, but phosphorylation of Ser46 and Thr55 markedly increases its binding affinity (Di Lello et al. 2006). Phosphorylated TAD2 IDR bound to the human PH domain runs along a positively charged path on the PH domain surface comprising Lys18, Lys19, Lys51, Lys54, Lys60, Lys62, His78, Lys104, and/or Arg105 (Fig. 5a, d), similar to the acidic string IDR of TFIIEα (Okuda and Nishimura 2014) (Fig. 5a, c). In addition, Trp53 of phosphorylated TAD2 IDR is snugly inserted into pocket 1 and makes amino-aromatic interactions with Gln64, Gln66, and Asn76 of the PH domain (Fig. 5j). Gln52 of phosphorylated TAD2 IDR participates in these amino-aromatic interactions, while Phe54 lies outside pocket 1 but makes hydrophobic contacts with Ile55 and Pro57 of the PH domain. As mentioned above, this interaction contrasts with the complex of unphosphorylated p53 TAD2 IDR bound to the yeast Tfb1 PH domain, where TAD2 IDR inserts Phe54 into pocket 1, forming an amphipathic α-helix (Di Lello et al. 2006). Upon binding to the human p62 PH domain, in contrast, helix formation does not occur even for unphosphorylated TAD2 IDR (Okuda and Nishimura 2014). Thus, TAD2 IDR of p53 discerns structural differences in the surface between human and yeast PH domains and dramatically changes its conformation to the best fit. MD simulations imply that p53 TAD2 IDR might bind to the human p62 PH domain in an “induced fit” manner, but use “conformation selection” or a combination mode to bind to the yeast Tfb1 PH domain (Zhao et al. 2020). It should be noted, however, that yeast has no homologue of p53. As far as we know, this is the first case of TAD2 IDR binding without α-helix formation, demonstrating much higher conformational malleability of p53 TAD2 IDR than previously appreciated.

Interaction of TFIIH with the cell cycle controller DP1

The transcription factor DP1 forms a heterodimer with E2F1 that coordinates gene expression during G1/S cell cycle progression. E2F1 has long been known to interact with p62 via its TAD IDR (Pearson and Greenblatt 1997), but there were no reports of a TAD IDR in DP1 (Fig. 3c). We previously noticed, however, that DP1 contains a sequence similar to the acidic string IDR of TFIIEα in its C-terminal region, which had an unknown function at that time (Fig. 3g). An NMR binding assay showed that E2F1 TAD IDR weakly interacts with the p62 PH domain, while the acidic string IDR of DP1 binds with much higher affinity, suggesting that DP1 has TAD activity (Okuda et al. 2016a). The DP1 acidic string IDR forms a twisted U-shaped conformation on the surface of the PH domain (Fig. 4d). Almost all the acidic residues in the DP1 acidic string IDR interact electrostatically with Arg16, Lys18, Lys19, Lys51, Lys54, Lys60, Lys62, His78, Lys104, and Lys106 of the PH domain (Fig. 5a, e). The aromatic ring of Phe403 in the DP1 acidic string IDR occupies pocket 1 in the PH domain (Fig. 5k). In cells, the transcriptional activity of E2F1–DP1 is reduced when Phe403 of DP1 replaced with alanine, a mutation that significantly decreases the binding activity of a DP1 peptide to the PH domain in vitro. These findings indicate that the acidic string IDR of DP1 contributes to the transcriptional activity of E2F1–DP1 as a TAD, and plays a vital role in TFIIH recruitment.

Interaction of TFIIH with the NER factor XPC

The p62 PH domain also plays a vital role in recruiting TFIIH to sites of DNA damage during NER, a ubiquitous and versatile DNA repair system for protecting the genome from risks such as chemical mutagens, hazardous metabolic byproducts, and ultraviolet (UV) radiation that may induce base lesions. Mammalian NER is initiated either by a damage recognition subpathway called global genome repair (GGR) (Sugasawa et al. 1998) or by transcription-coupled repair (TCR) (Mellon et al. 1987).

XPC (xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group C) is an important factor in GGR, and mutations in the XPC gene cause an autosomal recessive disorder, xeroderma pigmentosum (Legerski and Peterson 1992). In GGR, XPC together with RAD23B and CETN2 detects DNA helix-distorting lesions on the whole genome (Masutani et al. 1994; Shivji et al. 1994; Araki et al. 2001). XPC then recruits TFIIH to the lesion by interacting with the p62 and XPB subunits (Yokoi et al. 2000). A structural study on budding yeast proteins revealed that the N-terminal acidic segment of Rad4, a homologue of XPC, binds to the Tfb1 PH domain with high affinity (Lafrance-Vanasse et al. 2013). Human XPC also strongly binds to the p62 PH domain by the corresponding acidic segment IDR (Fig. 3d). The acidic string IDR of XPC extensively makes electrostatic contacts with Lys18, Lys19, Lys51, Lys54, Lys60, Lys62, His78, Arg89, Lys102, and Lys104 by using every acidic amino acid within residues 124–141 (Fig. 3g, Fig. 4e, Fig. 5a, f), and stabilizes itself by anchoring Trp133 and Val136 into pockets 1 and 2, respectively, of the PH domain (Okuda et al. 2015) (Fig. 5l). In cells expressing mutant XPC with alanine substitution at Trp133 or Trp133/Val136, sensitivity to UV is substantially increased, the interaction of TFIIH with XPC and its recruitment to sites of UV-induced DNA damage is largely abolished, and the removal of UV-induced photoproducts from genomic DNA is deficient. Thus, the p62 PH domain plays a predominant role in leading TFIIH to the site where XPC is bound.

Interaction of TFIIH with the TCR factor UVSSA

In the TCR subpathway, an elongating RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) encounters a lesion on the transcribed DNA strand of actively transcribed genes. The resultant stalled RNAPII is displaced or backtracked by the TCR-initiation complex, comprising CSB, CSA, UVSSA, and USP7, and TFIIH is subsequently loaded onto the damaged site. Of the TCR-specific proteins, only UVSSA (UV-specific scaffold protein A) incorporates a sequence similar to the acidic string IDRs of XPC and TFIIEα in the central IDR (Okuda et al. 2017) (Fig. 3e, g). UVSSA is known to be crucial in TCR (Nakazawa et al. 2012; Schwertman et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2012), and mutations in the UVSSA gene cause UVsS complementation group A (UVSS-A), a rare autosomal recessive genodermatosis (Fujiwara et al. 1981; Itoh et al. 1994, 1995).

An ITC experiment has shown that the UVSSA acidic string IDR binds exothermically to the p62 PH domain with a Kd of 71 nM (Okuda et al. 2017). This binding affinity is equivalent to that of XPC (Kd = 60–140 nM) and TFIIEα (Kd = 95 nM), and higher than that of p53 (Kd = 960 nM) and DP1 (Kd = 980 nM). The UVSSA acidic string IDR uses all acidic residues in the region 400–418 to interact electrostatically with Arg16, Lys18, Lys19, Lys54, Lys60, Lys62, His78, Lys102, and Lys104 of the PH domain (Fig. 4f, Fig. 5a, g), and inserts Phe408 and Val411 into pockets 1 and 2, respectively (Okuda et al. 2017) (Fig. 5m). This interaction mechanism strikingly resembles that of the XPC acidic string IDR with the p62 PH domain, although XPC inserts a tryptophan not a phenylalanine residue into pocket 1 (Fig. 5l). TCR activity in cells, evaluated via the recovery of RNA synthesis after UV irradiation, was found to be markedly diminished in UVSSA-deficient cells expressing UVSSA mutated at either of the two pocket-inserted residues, Phe408 or Val411. In particular, alanine substitution at Phe408 caused a marked reduction, whereas tryptophan substitution to resemble XPC did not have such a large effect. Regarding Val411, substitution with glutamate and asparagine to mimic p53 and DP1, respectively, diminished TCR activity similar to alanine substitution. The results of immunoprecipitation using full-length UVSSA and p62 were also well correlated with the in vitro binding activities measured for the mutants. Therefore, a common mechanism of TFIIH recruitment is shared by UVSSA in TCR and XPC in GGR.

Interaction of TFIIH with RNA polymerases

In eukaryotic transcription, three RNA polymerases, RNAPI, RNAPII, and RNAPIII, are responsible for synthesizing the different types of RNA: RNAPI for ribosomal RNA; RNAPII for messenger RNA and most small nuclear RNAs; and RNAPIII for transfer RNA and other small RNAs (Roeder and Rutter 1969; Adman et al. 1972). The three RNA polymerases are multi-subunit complexes comprising five common subunits and several specific subunits, with more than 12 subunits in total (Sklar et al. 1975; Valenzuela et al. 1976). Recently, a novel interaction between a common tail of RNA polymerases and the PH domain of p62 has been discovered (Okuda et al. 2022).

The RPB6 subunit is shared by all three RNA polymerases (Buhler et al. 1980; Bréant et al. 1983) (Fig. 6). The N-tail of RPB6 is a short flexible IDR of unknown function (del Río-Portilla et al. 1999) (Fig. 3f) that is invisible in the crystal (Cramer et al. 2000) and cryo-EM (He et al. 2016) structures (Fig. 6). The visible structured core — comprising about two-thirds of the molecule — is highly conserved in various species. Although the N-tail IDRs of RPB6 are generally divergent (Minakhin et al. 2001), those in vertebrate species contain highly conserved regions resembling acidic string IDRs (Okuda et al. 2022) (Fig. 3g). Indeed, human RPB6 interacts with the PH domain of TFIIH by the acidic string IDR in its flexible N-tail (Fig. 4g, h), making electrostatic contacts with Lys18, Lys19, Lys54, Lys60, Lys62, His78, Arg89, and Lys104 (Fig. 5a, h), while Phe13 and Val16 fit into pockets 1 and 2, respectively, in the PH domain (Fig. 5n).

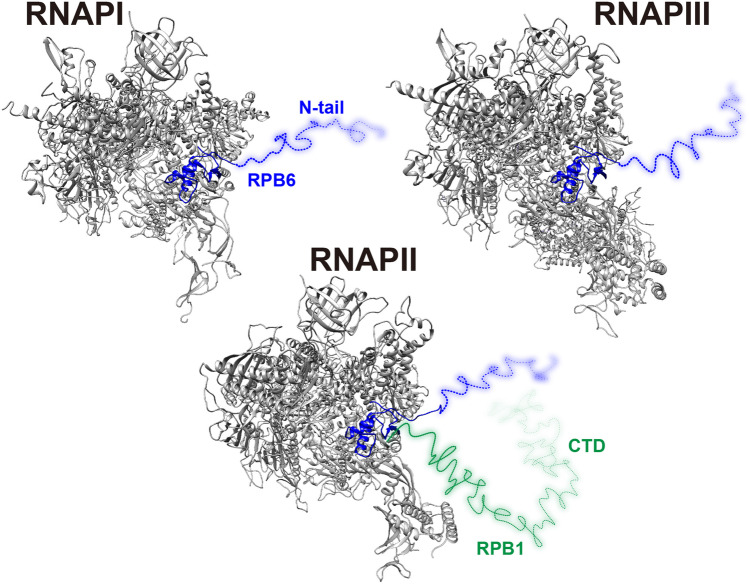

Fig. 6.

Cryo-EM structures of three human RNA polymerases: RNAPI [PDB ID 7OBB], RNAPII [PDB ID 5IY7], and RNAPIII [PDB ID 7A6H]. The invisible RPB6 N-tail and RPB1 C-terminal domain (CTD) are drawn freehand as blue and green broken lines, respectively

In ITC experiments, alanine substitution of Phe13 and Val16, but not Phe8, diminished the binding affinity of RPB6 for the PH domain (Okuda et al. 2022). Further reduction was not caused by the double substitution of Phe13 and Val16; however, substitution of both Phe8 and Phe13 completely abolished the interaction, suggesting that — in the absence of Phe13 — Phe8 can fit into pocket 1 with reduced binding activity. Both the Phe8/Phe13 double mutation and complete deletion of the acidic string IDR (N-terminal 20 residues) resulted in cell growth defects associated with a significant reduction in the transcription of RNAPI-, RNAPII-, and RNAPIII-transcribed genes, as well as defects in TCR of RNAPI- and RNAPII-transcribed genes. Collectively, these observations demonstrate that TFIIH is engaged in all RNA polymerase systems through the RPB6–TFIIH p62 interaction.

Principles of TFIIH recognition of nuclear proteins

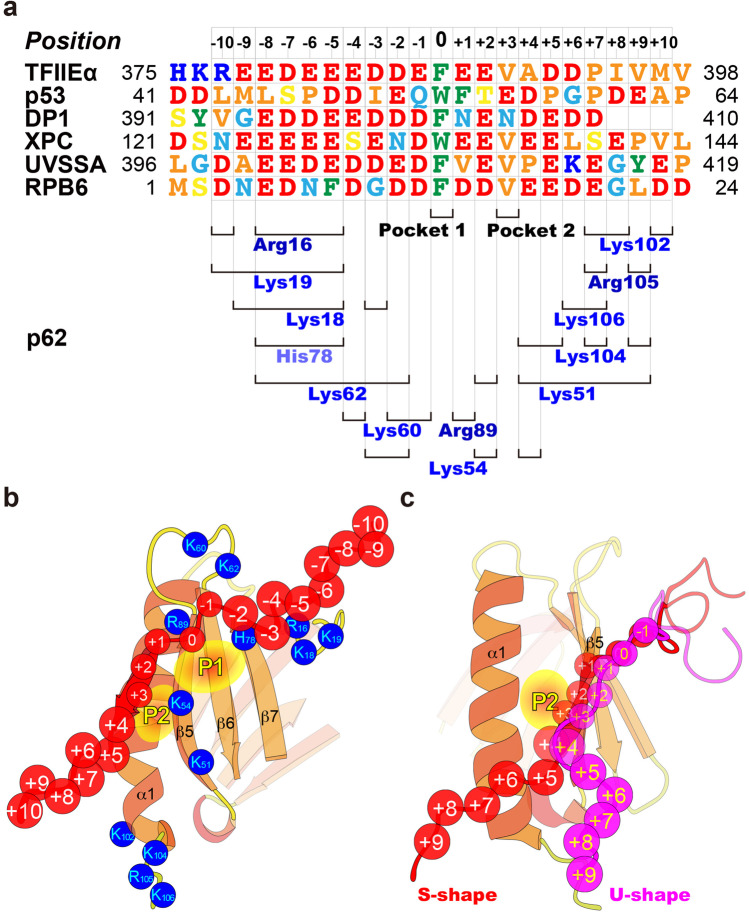

The six available structures of TFIIH complexes unveil common rules governing recognition of the p62 PH domain of TFIIH. For convenience, we number the positions of residues in the acidic string IDR of the target protein based on designation of the aromatic amino acid inserted into pocket 1 in the PH domain as residue “0” (Fig. 7a, b).

Fig. 7.

Definition of residue position in acidic strings of TFIIH p62 target proteins. a Positions of residues in the sequence. Serine and threonine residues that are phosphorylated in vivo are colored yellow. The positions of pocket-inserted amino acids and the approximate location of acidic amino acid responsible for electrostatic interactions with each basic amino acid of the p62 PH domain are shown below the alignment. b Position of acidic string residues in the complex structure. Basic residues of the p62 PH domain that electrostatically interact with an acidic string are colored blue. c S-shaped and U-shaped acidic strings. In b, c, the circle size (small and large) of each residue position represents spatial dispersion in the NMR ensemble structures. P1 and P2 indicate pocket 1 and pocket 2, respectively, in the p62 PH domain

Rule 1: The TFIIH-binding site of a target protein is located in an acidic IDR. Except for TFIIEα, the target proteins use a continuous acidic IDR for binding (Fig. 3). In the case of TFIIEα, the N-terminal tail IDR (residues 381–394) alone exhibits moderate binding ability, but both the core structure and flexible tail IDR are necessary for strong binding (Okuda et al. 2008). Sequence continuity of the IDR is not always essential for binding to TFIIH.

Rule 2: Numerous acidic residues interact electrostatically with most of the basic residues on the binding surface of the PH domain. It seems likely that there is a relatively loose region of acidic residues that interact electrostatically with each of basic residues of the PH domain (Fig. 7a). With respect to acidity, p53 is less acidic than the other target proteins: it has 7 acidic amino acids, while the others contain 12 or 13 located in positions –10 to + 10 (Fig. 7a). However, p53 compensates for this insufficient acidity with the dual phosphorylation of serine at position –7 (Ser46) and threonine at position + 2 (Thr55), as mentioned above. XPC contains two serine residues at position –4 (Ser129) and + 7 (Ser140), which are phosphorylated in vivo (Olsen et al. 2006). In the complex, Ser129 is in the vicinity of Lys60 and Lys62 of the PH domain of TFIIH, and phosphorylation augments the binding affinity (Okuda et al. 2015). Phosphorylation of these residues and the enhanced interaction of the p53 TAD2 and the XPC acidic string IDRs with the p62 PH domain can be monitored simultaneously and in real-time by NMR (Okuda and Nishimura 2015). Serine and threonine residues, especially those that are phosphorylated in vivo, should be considered as binding-affinity adjustable residues. In UVSSA, substitution of the acidic residues Glu401 (position –7), Glu410 (position + 2), and Glu413 (position + 5) with alanine, lysine, and arginine did not markedly decrease the TCR activity of each mutant (Okuda et al. 2017), suggesting that the net charge of an acidic string IDR is important for binding to the PH domain of TFIIH.

Rule 3: A phenylalanine or tryptophan at position 0 inserts into pocket 1 in the PH domain. All target proteins insert the aromatic ring of phenylalanine or tryptophan at position 0 into pocket 1 of the PH domain in the same orientation (Fig. 5i–n, Fig. 7a, b). Substitution of these aromatic residues with alanine or another amino acid leads to marked or complete loss of binding ability, which correlates well with transactivation activity and NER activity, as mentioned above. In combination with extensive electrostatic interactions, insertion of phenylalanine or tryptophan at position 0 into pocket 1 in a fixed direction is necessary for enhancing binding specificity (Okuda et al. 2016b). It will be interesting to examine whether the other aromatic amino acid tyrosine can replace these residues.

Rule 4: An extended string-like conformation is formed in a binding-coupled manner. An extended string-like conformation is optimal for both making electrostatic interactions with the widely distributed basic residues and inserting into the two pockets in the PH domain. Notably, in cross-species complexes, human p53 TAD2 (Di Lello et al. 2006), Herpes simplex virion protein 16 (VP16) TAD (Langlois et al. 2008), erythroid Krüppel-like factor (EKLF) TAD1, NF-кB subunit p65/RelA TAD1 (Lecoq et al. 2017), and Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2) TAD (Chabot et al. 2014) all form an α-helix on the basic surface of the PH domain of budding yeast Tfb1. As discussed in a study on p53 TAD2 IDR (Okuda and Nishimura 2014), such different conformations of the bound form are due to discordance in the binding surface of the PH domain between human p62 and yeast Tfb1.

Rule 5: Insertion of a residue at position + 3 into pocket 2 in the PH domain determines the path of the C-terminal half of the acidic string IDR. The bound form of the acidic string IDR can be classified into two types, S-shaped and U-shaped, which differ in the path of the C-terminal half of the acidic string IDR on the p62 PH domain (Fig. 7c). In the S-shaped acidic string IDRs of TFIIEα, XPC, UVSSA, and RPB6, the residue at position + 3 is a valine (Fig. 7a), which inserts into pocket 2 between the β5 strand and the C-terminal α1 helix in the PH domain, allowing the acidic string IDR to form a β-addition motif with the β5 strand and following regions to interact with the α1 helix of the PH domain (Fig. 4b, e, f, h, Fig. 7c). In the U-shaped acidic string IDRs of p53 and DP1, Glu56 only partially inserts, and Asn406 not even partially inserts, into pocket 2 (Fig. 5j, k), which is unlikely to be sufficient to bring the following region of the acidic string IDR into contact with the α1 helix in the PH domain (Fig. 4c, d, Fig. 7c). Notably, valine substitution of Asn406 of the DP1 acidic string IDR increases the binding affinity and suggests that the C-terminal half of the acidic string IDR approaches the α1 helix in the PH domain (Okuda et al. 2016a).

TFIIH is a multifunctional protein complex recruited at various sites necessary for transcription, DNA repair, and cell cycle around DNA through specific interactions with other numerous functional proteins. A common recruiting mechanism of TFIIH seems to be evolved during necessary functions for TFIIH rather than evolving individual recruiting mechanism of TFIIH in each individual function around DNA. The common rules for the interaction thus have now been obtained. We speculate that the p62 PH domain is ideal as an interaction domain responsible for the common rules in TFIIH because of its dynamical behavior in a whole TFIIH architecture as shown below.

Specific roles of the acidic string IDRs in the recognition of TFIIH

Although the atomic structure of human TFIIH has remained unsolved due to a lack of high-quality crystals, marked technical advances in cryo-EM have largely enabled the Core subcomplex to be visualized (Greber et al. 2017, 2019) (Fig. 2a). Nevertheless, the PH domain of p62 is invisible, suggesting the dynamic behavior of this domain in TFIIH (Fig. 2a, Fig. 8a). Concordantly, the solution NMR structure of the N-terminal region of human p62 (residues 1–158, p621–158), including both the PH domain and the BSD1 domain of p62 (which is clearly visible in the cryo-EM structure), indicates that each domain behaves independently (Okuda et al. 2021) (Fig. 8b). Furthermore, the 15 N relaxation rates R1 and R2, 15 N–{1H} NOE, and amide proton solvent exchange rates highlight the high mobility of the interdomain linker (residues 104–108), which causes the dynamic behavior of the PH and BSD1 domains in solution.

Fig. 8.

Dynamical movement of the p62 PH domain in TFIIH. a Cryo-EM structure of human TFIIH [PDB ID 6NMI]. b NMR structure (20 best structures) of human p621-158 [PDB ID 7BUL]. c MD simulation models of human TFIIH built by combining the cryo-EM [PDB ID 6NMI] and NMR [PDB ID 7BUL] structures. Six structures are shown. d MD simulation model of the complex of human TFIIH with XPC. e Docking structural model of the complex of human RNAPII with TFIIH. The model was built by combining the cryo-EM structure of human RNAPII [PDB ID 5IY7], the MD model of human TFIIH Core (shown in Fig. 2c), and the NMR structure of the complex of human RPB6 with the p62 PH domain [PDB ID 7DTI]. In a–d, p62 is colored black; the PH domain is colored orange, red, pink, cyan, green, and marine blue; the interdomain linker is colored yellow; and the BSD1 domain is colored gray. XPC is colored magenta. In e, RNAPII is colored cyan; RPB6 is colored blue; TFIIH is colored yellow; and p62 PH domain is colored orange

The NMR structure of p621–158 has been docked into the cryo-EM structure of human TFIIH and the docked structure subjected to MD simulations. In these simulations, the PH domain moves dynamically around the surface of the Core subcomplex (Fig. 8c); however, its spatial distribution is limited owing to the short interdomain linker. In MD simulations of TFIIH docked to the p62 target proteins TFIIEα, p53, DP1, XPC, and UVSSA, the intermolecular interactions are maintained, and the relative positions and orientations of the PH domain and the target protein change with respect to the whole TFIIH protein (Fig. 8d). A docking structural model of the complex of human TFIIH with RNAPII bound via the interaction of the p62 PH domain and the RPB6 N-tail IDR can be built in a similar way (Okuda et al. 2022) (Fig. 8e). These results may explain the necessity of an IDR in recognition of the PH domain of p62 in TFIIH. A completely free state of the PH domain would be advantageous for approach by the target protein, but would simultaneously provide a chance for many irrelevant proteins to access TFIIH. Instead, proper spatial restriction would selectively allow access to intrinsically disordered target proteins, while preventing the approach of structured proteins. This hypothesis is not applicable to yeast Tfb1, which has an interdomain linker of ~ 50 residues. Further studies are needed to explain species-specific differences in the dynamics of the PH domain in TFIIH.

Chp1 and HP1 in heterochromatin

Heterochromatin, a folded and condensed higher-order structure of chromatin, is critical for genomic stability and transcriptional silencing (Fig. 1a), and H3K9me is an essential hallmark of its formation. Chromatin-related proteins often contain a small chromodomain (CD) of about 60 amino acids, consisting of a three-stranded β sheet together with a C-terminal α helix; the CD is known as a methylated histone lysine binding domain, in addition to having other functions (Okuda et al. 2007, 2020; Shimojo et al. 2008). Yeast Chp1, which contains a CD in its N-terminus, plays a role in RNA-induced transcriptional silencing (RITS) by binding to both H3K9me and non-coding RNA to facilitate RNAi-mediated heterochromatin assembly. The Chp1 CD alone can bind to H3K9me, as revealed by X-ray crystallography (Schalch et al. 2009); however, in the structure of the Chp1 N-tail IDR together with the CD bound to H3K9me, the binding surface for non-coding RNA is formed by a short helix in the N-tail IDR (Ishida et al. 2012). This is reminiscent of the histone H4/H2A acetyltransferase of budding yeast, Esa1 (essential Sas-related acetyltransferase 1), which is presumed to contain an N-terminal CD from its amino acid sequence. In the solution structure of Esa1, the presumed CD is a tudor domain consisting of a β-barrel structure, and the N-tail IDR together with this domain forms an RNA-binding surface, and not the domain alone (Shimojo et al. 2008). We also revealed that the RNA-binding ability of Esa1 is essential by examining RNA-binding deficient mutants, which were lethal.

In mammalian cells, there are three isoforms of heterochromatin protein 1, HP1α, HP1β, and HP1γ, all of which contain an N-terminal CD that binds to H3K9me and a C-terminal chromoshadow domain that stabilizes higher-order chromatin structure by bridging neighboring nucleosomes containing H3K9me. The HP1 N-tails before the CD are IDRs and less conserved among the three isoforms as compared with the CD itself. In particular, HP1α contains four successive serine residues in the N-tail IDR, all of which are phosphorylated in vivo. This phosphorylation strongly enhances the affinity of the HP1α CD for H3K9me and increases the nucleosome-binding specificity of HP1α (Sadaie et al. 2008; Nishibuchi et al. 2014). It also promotes the formation of liquid–liquid phase separation of HP1α in vitro (Larson et al. 2017; Strom et al. 2017). NMR, small-angle-X-ray-scattering, and MD studies on the N-terminal domain of HP1α comprising the CD and the N-tail IDR have shown that the unphosphorylated N-tail IDR dynamically fluctuates to hinder binding between histone H3K9me and the CD, while the phosphorylated N-tail IDR extends to allow H3K9me binding to the CD and enhances the association via electrostatic interactions with the basic residues of the H3 N-tail IDR that follow H3K9me (Shimojo et al. 2016).

Histone tail IDR dynamics in nucleosomes

Although X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM methods have provided detailed structures of the NCP, nucleosome, and chromatosome, they cannot produce atomic resolution structures of histone tails, including the N-tail IDRs of H2A, H2B, H3, H4, and H1, and the C-tail IDRs of H2A and H1 (Luger et al. 1997; Zhou et al. 2015; Bednar et al. 2017). During transcription, replication, recombination, DNA repair, and epigenetic regulation, histones — mostly histone tails — are subject to post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination (Fischle et al. 2003; Stewart-Morgan et al. 2020; Peng et al. 2020, 2021). NMR studies are now documenting the dynamics and PTMs of histone tail IDRs in the NCP, nucleosome, and chromatosome. NMR has shown that, in the nucleosome, the phosphorylated H3 N-tail IDR is released from linker-DNA to enhance its acetylation by the acetyltransferase Gcn5 (Liokatis et al. 2016; Stützer et al. 2016), and the H3 N-tail IDR in the NCP interacts robustly but dynamically with core-DNA (Morrison et al. 2018).

NMR has also revealed that tetra-acetylation of the H4 N-tail IDR in the nucleosome alters the dynamic structure of the H3 N-tail IDR on linker-DNA, leading to enhanced acetylation of the H3 N-tail IDR by Gcn5 (Furukawa et al. 2020). Recently, NMR studies have facilitated comparisons of the dynamics of the H3 N-tail IDRs between the nucleosome with linker-DNA and the 145-bp NCP (Furukawa et al. 2022). In the nucleosome with unmodified H4 N-tail IDRs, the H3 N-tail IDR dynamically contacts both linker-DNA and core-DNA; in the 145-bp NCP with unmodified H4 N-tail IDRs, however, the H3 N-tail IDR robustly but dynamically contacts core-DNA, probably buried in two DNA gyres. After H4 acetylation, the acetylated H4 N-tail IDRs in both the NCP and the nucleosome are dynamically released from their core-DNA-contact state. In the NCP with H4 N-tail IDR acetylation, the H3 N-tail IDR still contacts core-DNA; in the nucleosome with the H4 N-tail IDR acetylation, however, the H3 N-tail IDR shifts to contact mainly linker-DNA. These observations suggest that there is mutual interaction between the H3 and H4 N-tail IDRs in the nucleosome. Interestingly, H3K14 in both the NCP with acetylated H4 N-tail IDRs and that with unacetylated H4 N-tail IDRs is less accessible to the acetyltransferase Gcn5 than the H3 N-tail IDR in the nucleosome with unacetylated H4 N-tail IDR. Acetylation of the H4 N-tail IDR in the nucleosome enhances further the acetylation of H3K14.

NMR and MD simulations have also been used to solve the whole structure of the isolated H2A/H2B heterodimer, together with the dynamic character of the H2A N- and C-tail IDRs and the H2B N-tail IDR (Moriwaki et al. 2016). These tail IDRs adopt characteristic dynamic ensembles of fluctuating conformations. The H2A C-tail IDR dynamics are greatly affected by the presence of linker-DNA in the nucleosome, whereas the dynamic structures of H2A and H2B N-tail IDRs are similar in the NCP and the nucleosome, and thus independent of the presence of linker-DNA. However, both the H2A N-tail and the H2B N-tail IDRs adopt two distinct conformations: one H2A N-tail IDR locates in the major groove, while the other locates in the minor groove of core-DNA; and one H2B N-tail IDR buried between the two DNA gyres extends towards the entry/exit side of DNA, while the other extends towards the reverse side (Ohtomo et al. 2021). There is also a correlation between the H2A N-tail and H2B N-tail IDR conformations (Ohtomo et al. 2021; Tsunaka et al. 2022b).

NMR studies show that each histone tail IDR adopts a characteristic dynamic conformation and the dynamics of the tail IDRs influence each other, indicating the existence of a regulatory histone tail IDR network even on a nucleosome (Furukawa et al. 2020, 2022; Tsunaka et al. 2022a). Furthermore, the linker histone H1 asymmetrically affects the dynamics of the histone tail IDR network in the nucleosome: one H3 N-tail IDR adopts the conformation contacting core-DNA observed in the NCP due to the steric hindrance of H1 on linker-DNA, while the other H3 N-tail IDR contacts linker-DNA as in the conventional nucleosome without H1 (Furukawa et al 2022).

Histone chaperones

Histone chaperones are ATP-independent proteins that function as a modulator of chromatin configuration and organization. They interact with highly basic histone proteins and support histone deposition, sliding, replacement, and eviction within nucleosomes (Hammond et al. 2017; Scott and Campos 2020; Huang et al. 2020). They have large stretches of IDRs, which mostly consist of acidic and/or basic residues. In particular, two histone chaperones, FACT (facilitates chromatin transcription) and NAP1 (Nucleosome assembly protein 1), are essential for chromatin remodeling at the boundary between heterochromatin and euchromatin (Nakayama et al. 2012; Shimada et al. 2019).

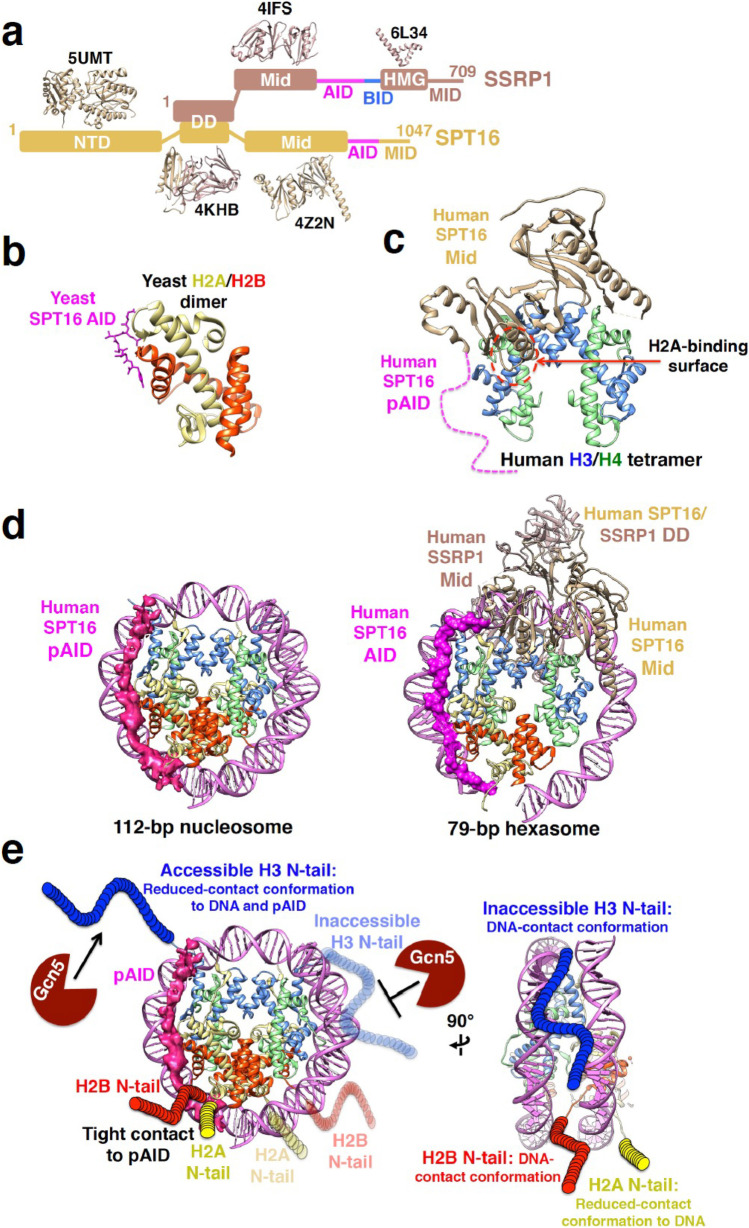

Histone chaperone FACT

FACT is an evolutionarily conserved histone chaperone that plays important roles in DNA transcription, repair, and replication (Piquet et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2018; Jeronimo et al. 2021; Safaric et al. 2022). It modulates both disassembly and reassembly of the nucleosome through its interaction with the nucleosome and nucleosomal components (Zhou et al. 2020; Formosa and Winston 2020; Jeronimo and Robert 2022). More importantly, FACT has been shown to play a role in chromatin maintenance by repressing histone turnover (Sandlesh et al. 2020; Holla et al. 2020; Takahata et al. 2021; Murawska et al. 2021).

Human FACT is composed of two subunits: structure-specific recognition protein-1 (SSRP1) and suppressor of Ty 16 (SPT16) (Fig. 9a) (Zhou et al. 2020). The domain structure of SPT16, which is highly conserved in different organisms, comprises three structural domains, an N-terminal domain (NTD), a dimerization domain (DD), and a middle domain (Mid), as well as an acidic ID (AID) segment and a mixed charge ID region (MID) abundant with negatively and positively charged residues at the C-terminus (Fig. 9a). The SSRP1 subunit comprises three structural domains, DD, Mid, and a high mobility group domain (HMG), in addition to an AID region, an HMG-flanking basic ID (BID) segment, and a MID region at the extreme C-terminus (Fig. 9a). Two high-speed atomic force microscopy studies simultaneously visualized the string-like structure of the ID regions of SSRP1 and SPT16 in the FACT complex on a mica surface in solution (Miyagi et al. 2008; Hashimoto et al. 2013). More recently, several studies have provided insight into how FACT IDRs interact with nucleosomal components.

Fig. 9.

Structures of FACT with histones and nucleosomes. a Domain structure of SSRP1 and SPT16 subunits in human FACT. Representative structures are shown with their PDB IDs. NTD, N-terminal domain; DD, dimerization domain; Mid, middle domain; AID, acidic intrinsically disordered region; BID, basic intrinsically disordered region; HMG, high mobility group domain; MID, mixed charge intrinsically disordered region. SSRP1, SPT16, AID, and BID are colored rosy-brown, tan, pink, and blue, respectively. b Crystal structure of AID of yeast SPT16 binding to yeast H2A/H2B dimer (PDB ID 4WNN). In all panels, the angle of each histone structure is fixed. H2A and H2B are colored yellow and red, respectively. c Crystal structure of the Mid-pAID region of human SPT16 binding to human (H3/H4)2 tetramer (PDB ID 4Z2M). Dotted pink line indicates the pAID segment, which is not observed in the structure and is modeled without experimental data. H3 and H4 are colored blue and green, respectively. d Cryo-EM structures of pAID of human SPT16 binding to 112-bp nucleosome (right, EMD-9639 and PDB ID 2CV5 modified) and the truncated mutant of human FACT binding to 79-bp hexasome (left, PDB ID 6UPK). pAID is shown as deep pink density. DNA is colored orchid. e Histone tail conformation in the complex of human SPT16 pAID with 112-bp nucleosome (right, EMD-9639 and PDB ID 2CV5). Colored circular chains denote histone H3, H2A, and H2B N-tails, which are not observed in the EM structure. The conformation of each histone tail is modeled based on the NMR data

For example, the AID segment of yeast SPT16 binds to a yeast H2A/H2B dimer, as shown by X-ray crystallography (Fig. 9b) (Kemble et al. 2015). The phosphorylated AID (pAID) segment of human SPT16 interacts with an H2B N-tail IDR that is exposed from nucleosomal DNA by a double-strand break (Tsunaka et al. 2016). The pAID segment is also required for the formation of a complex of human FACT with a human (H3/H4)2 tetramer (Tsunaka et al. 2016); the crystal structure of the complex shows that the pAID-adjacent Mid domain of human SPT16 correctly interacts with the H2A-binding surface of the (H3/H4)2 tetramer (Fig. 9c). These observations suggest a model in which steric collision in the nucleosome displaces the H2A/H2B dimer from the nucleosome. This model is consistent with a study in which human SPT16 was shown to displace H2A/H2B dimers from the nucleosome together with DNA stretching (Chen et al. 2018); the study further showed that a FACT mutant with deletion of Mid and AID of SPT16 hardly displaced the H2A/H2B dimer from nucleosome, suggesting that Mid and AID are crucial for this displacement function of FACT.

Cryo-EM studies of the AID segment of SPT16 show that it forms an extended string-like structure that imitates DNA in the unwrapped nucleosome by shielding the DNA-binding surface of H2A, H2B, and H3 (Fig. 9d) (Mayanagi et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2020; Farnung et al. 2021). The cryo-EM structures suggest that replacing DNA with AID maintains the structure of the NCP, thereby impeding histone loss. It has also been shown that the AID–nucleosome complex depends on the phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues in AID (Mayanagi et al. 2019). Recently, three serine and threonine sites in AID of SPT16 have been shown to be phosphorylated in Arabidopsis (Michl-Holzinger et al. 2022). Phenotypic analyses of spt16-mutant plants demonstrated that expression of wild-type SPT16 partially complemented the mutant phenotype, whereas expression of a phosphorylation site mutant barely had an effect. This suggests that phosphorylation of SPT16 is important for its impact on growth and development in Arabidopsis. Furthermore, some genes were shown to require phosphorylation of AID in order to establish the correct nucleosome occupancy at their transcriptional start site, highlighting the biological significance of AID phosphorylation.

An NMR analysis of the pAID segment has revealed that, in the unwrapped nucleosome, the replacement of DNA with pAID alters the conformational ensemble of the adjacent H3 N-tail IDR, but has little to no effect on the other tail IDR (Tsunaka et al. 2020). In addition, Lys14 acetylation of the pAID-adjacent H3 N-tail IDR by Gcn5 is facilitated relative to that in the canonical nucleosome. This suggests that one H3 N-tail IDR becomes more accessible in the presence of pAID, while the other H3 N-tail IDR is inaccessible because of its interaction with two DNA gyres (Fig. 9e). The accessible conformation of IDR facilitates interactions with various chromatin-associated proteins, such as PHD (Plant homeodomain) readers and histone-modified enzymes, which otherwise would not be accessible. In turn, the interactions with chromatin-associated proteins recruit further factors for downstream processes.

A recent NMR study has shown that FACT also modulates the conformations of the H2A and H2B N-tail IDRs in the unwrapped nucleosome (Tsunaka et al. 2022b). Whereas the H3 N-tail IDR adopts an accessible conformation on the pAID-binding side, the H2A and H2B N-tail IDRs maintain the nucleosomal structure with tight contacts to pAID (Fig. 9e). This suggests an appealing model in which the contacts of the H2A and H2B N-tail IDRs with pAID compensate for the reduced contact of the H3 N-tail IDR to pAID. In addition, the replacement of DNA with pAID alters the conformations of the distal N-tail IDRs in the unwrapped nucleosome from those in the canonical nucleosome. Overall, therefore, FACT seems to modulate chromatin signaling and accessibility of the H2A, H2B, and H3 N-tail IDRs within the unwrapped nucleosome.

Single-molecule analysis has shown that mono-ubiquitination at Lys119 in the H2A C-tail IDR of the nucleosome impedes both FACT binding on the nucleosome and nucleosome disassembly, but H2A ubiquitination hardly affects the chaperone function of FACT in nucleosome assembly (Wang et al. 2022). In addition, deubiquitination of the ubiquitinated nucleosome rescues the function of FACT in nucleosome disassembly to facilitate gene transcription. Therefore, it seems likely that the biological function of FACT is regulated by ubiquitination of the H2A C-tail IDR in the nucleosome.

Although the AID segment of the yeast SSRP1 homolog Pob3 has been shown to bind to the H2A/H2B dimer (Kemble et al. 2015), an earlier study failed to detect a similar interaction with AID of human SSRP1 (Winkler et al. 2011). The AID segment of human SSRP1 is phosphorylated (Li et al. 2005) and pAID forms a complex with the unwrapped nucleosome (Mayanagi et al. 2019). However, the degree of complex formation by SSRP1 pAID is lower than that by pAID of human SPT16 (Mayanagi et al. 2019). The phosphorylated pAID of Drosophila SSRP1 makes tight intramolecular interactions with its adjacent BID and the HMG domain, thereby impeding nucleosomal DNA binding (Tsunaka et al. 2009; Hashimoto et al. 2013). In addition, the DNA-binding affinity of BID and HMG in the nucleosome is decreased by phosphomimetic mutations of the unphosphorylated AID segment (Aoki et al. 2020). Therefore, we envisage that the DNA- and histone-binding function of SSRP1 may be suppressed by phosphorylation of its AID segment. On the other hand, the MID region at the C-terminus of human SSRP1 binds to DNA with a high propensity toward Z-DNA transition in cells and in vitro, implying that FACT accumulates in sites of DNA damage (Safina et al. 2017).

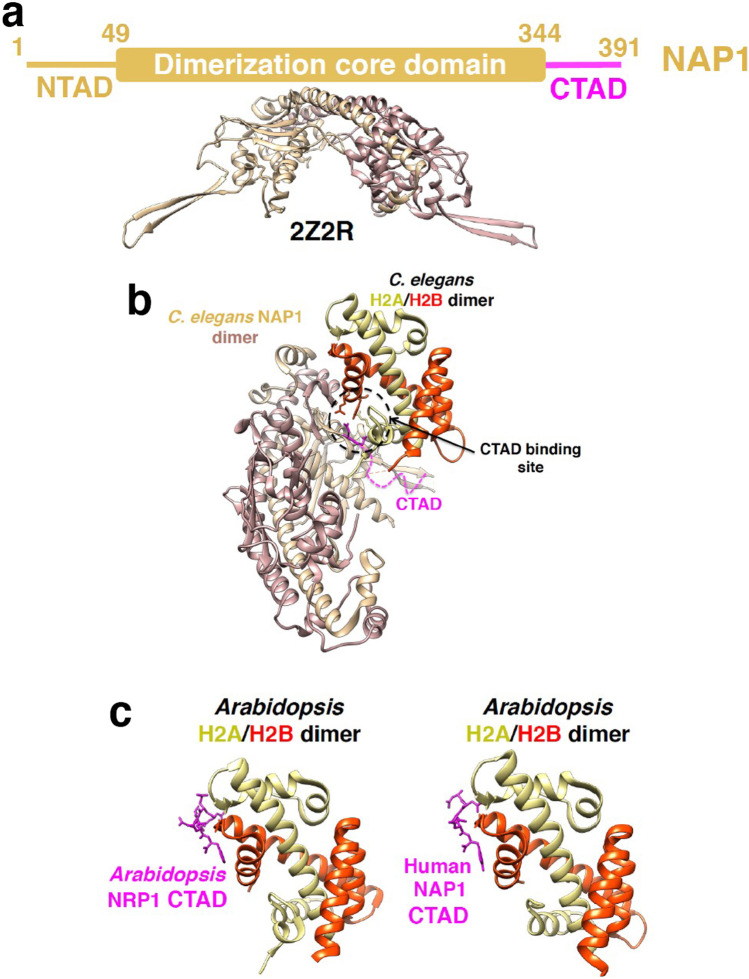

Histone chaperone NAP1

As another typical histone chaperone, NAP1 promotes nucleosome assembly (Park and Luger 2006) (Fig. 1a), interacts with newly synthesized H2A/H2B, mediates nuclear import, and displaces the old H2A/H2B dimer from the nucleosome (Mosammaparast et al. 2002; Miyaji-Yamaguchi et al. 2003). Unlike FACT, NAP1 forms homo-dimers and oligomers. Like FACT, NAP1 has a highly conserved domain architecture in different organisms, comprising a dimerization core domain and N- and C-terminal IDRs abundant with acidic residues (Fig. 10a) (Huang et al. 2020). The core domain of NAP1 is essential for histone binding and nucleosome assembly (McBryant et al. 2003; Gill et al. 2022).

Fig. 10.

Structures of the histone chaperone NAP1 complexed with histones. a Domain structure of human NAP1. NTAD, N-terminal acidic intrinsically disordered region; CTAD, C-terminal acidic intrinsically disordered region. NAP1 and CTAD are colored tan and pink, respectively. A representative core structure (PDB ID 2Z2R), colored tan and rosy-brown, is shown. b Crystal structure of the C. elegans NAP1 dimer, colored tan and rosy-brown, binding to C. elegans H2A/H2B dimer (PDB ID 6K00). CTAD is partially observed and colored pink. In all panels, the angle of the H2A/H2B structure is fixed. H2A and H2B are colored yellow and red, respectively. Dotted pink line indicates the invisible CTAD segment, which is modeled without experimental data. c Crystal structures of CTAD of Arabidopsis NRP1 binding to Arabidopsis H2A/H2B dimer (right, PDB ID 7BP6) and CTAD of human NAP1 binding to Arabidopsis H2A/H2B dimer (right, PDB ID 7BP4)

The C-terminal acidic ID (CTAD) region is not required for the nucleosome assembly activity of yeast Nap1 (McBryant et al. 2003; Park and Luger 2006), whereas CTAD of human NAP1 contributes to its histone binding and nucleosome assembly activity (Andrews et al. 2008; Okuwaki et al. 2010; Ohtomo et al. 2016). Our previous study found that CTAD of both human and yeast NAP1 directly interacts with the H2A/H2B dimer; however, the interaction of yeast CTAD is much weaker than that of human CTAD (Ohtomo et al. 2016). In addition, human CTAD promotes the interactions of two H2A/H2B dimers with the core domain of NAP1.

Three crystal structures of NAP1 core domains from yeast, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Arabidopsis in complex with one or two H2A/H2B dimers have revealed distinct and diverse binding modes of the core domain with histones (Aguilar-Gurrieri et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2019; Luo et al. 2020). In particular, the crystal structure of the C. elegans NAP1/H2A/H2B complex revealed that C. elegans NAP1 has a short CTAD that is partially involved in its histone binding surface (Fig. 10b) (Liu et al. 2019). We therefore consider that human CTAD may be longer than C. elegans CTAD to optimize histone binding.

Crystal structures of the CTADs of Arabidopsis NRP1 (NAP1-related protein 1) and human NAP1 with H2A/H2B show that CTAD has a conserved H2A/H2B-binding mode among NAP1 family proteins (Fig. 10c) (Luo et al. 2020). The H2A/H2B-binding site is similar to sites that interact with the AID regions of FACT (Fig. 9b) (Kemble et al. 2015) and two other histone chaperones, APLF (aprataxin and polynucleotide kinase–like factor) (Corbeski et al. 2018) and ANP32E (acidic nuclear phosphoprotein 32 kilodalton E) (Obri et al. 2014), indicating that the binding site on H2A/H2B is common to the acidic IDRs of histone chaperones. However, this site is different from the CTAD-binding site on H2A/H2B complexed with the C. elegans NAP1 core domain (Fig. 10b) (Liu et al. 2019), implying that CTAD of NAP1 may have multiple binding sites on H2A/H2B.

Similar to the phosphorylation of AID of FACT, the interaction between CTAD and H2A/H2B is regulated by polyglutamylation and polyglycylation modifications of CTAD (Regnard et al. 2000; Ikegami et al. 2008; Miller and Heald 2015). However, the biological function of CTAD of NAP1 is unknown, and thus needs further investigation in future studies.

Conclusion

In this review, we focused on the functional roles of IDRs in nuclear proteins such as target proteins of the general transcription factor TFIIH, the heterochromatin protein Chp1 and HP1, the histones, and the histone chaperone FACT and NAP1. Structural studies on these nuclear proteins highlight functional diversity of IDR. During the formation of the transcription preinitiation complex and the NER pre-incision complex, IDRs extended from these crowded complexes and regulatory element-bound proteins search TFIIH, taking advantage of high mobility. When binding to the PH domain of p62 in TFIIH, the target proteins’ IDRs form similarly an extended string-like conformation in a coupled folding and binding manner. In heterochromatin, HP1α’s IDR strikingly enhances the following CD’s H3K9me-binding ability and increases the nucleosome-binding specificity of HP1α by multiple phosphorylation. It also promotes the formation of liquid–liquid phase separation of HP1α. In the fundamental units of chromatin, NCPs, nucleosomes, and chromatosomes, the N-tail IDRs of histones, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 dynamically correlate each other; the N-tail IDRs of H2A and H2B adopt two different conformations: the entry/exit side and reverse side conformations of H2B N-tail IDR correlate to the major and minor groove conformations of H2A N-tail IDR, respectively independent of linker DNA, and acetylation of the H4 N-tail IDR correlates with the acetylation of the H3 N-tail IDR depending on linker DNA. So, histone tail IDRs have a dynamical network even on a single nucleosome. The histone chaperone FACT subunit SPT16’s extensively phosphorylated IDR forms an extended string-like structure to imitate DNA in the unwrapped nucleosome and shields the DNA-binding surface of histones H2A, H2B, and H3 to impede their loss, thereby modulating the conformational ensemble and accessibility of the H2A, H2B, and H3 N-tail IDRs within the unwrapped nucleosome. Another histone chaperone NAP1’s IDR promotes the interactions of two H2A/H2B dimers with the core domain of NAP1. As a whole each nuclear protein holds a rigid body architecture fixed on a basic platform such as DNA, however to interact with other proteins or modulate its function, the protruded IDRs from the rigid architecture play an essential function. In that sense DNA is a polyanionic flexible rod so that DNA binding region in a protein should hold a basic character, and then to regulate intramolecularly or intermolecularly the DNA binding function, an acidic IDR should be needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare sincere thanks to Dr. Haruki Nakamura for his valuable discussions during our study on NMR for DNA-protein interactions.

Funding

The researches were carried out with the support of Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on an NMR platform [07022019] (to Y.N.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan; and by Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery, Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) [Grant Number JP21am0101073 (to Y.N.)]; Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Research Fellow (JSPS KAKENHI 99J02846 to M.O.); Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (JSPS KAKENHI JP19770090 and JP21770121 to M.O.); Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (JSPS KAKENHI JP23570144, JP16K07277, and JP21K06035 to M.O., JP18K06064 and JP21K06021 to Y.T.).

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adman R, Schultz LD, Hall BD. Transcription in yeast: separation and properties of multiple FNA polymerases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:1702–1706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.7.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Gurrieri C, Larabi A, Vinayachandran V, et al. Structural evidence for Nap1-dependent H2A–H2B deposition and nucleosome assembly. EMBO J. 2016;35:1465–1482. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews AJ, Downing G, Brown K, et al. A thermodynamic model for Nap1-histone interactions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32412–32418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805918200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki D, Awazu A, Fujii M, et al. Ultrasensitive change in nucleosome binding by multiple phosphorylations to the intrinsically disordered region of the histone chaperone FACT. J Mol Biol. 2020;432:4637–4657. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki M, Masutani C, Takemura M, Uchida A, Sugasawa K, Kondoh J, Ohkuma Y, Hanaoka F. Centrosome protein centrin 2/caltractin 1 is part of the xeroderma pigmentosum group C complex that initiates global genome nucleotide excision repair. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18665–18672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednar J, Garcia-Saez I, Boopathi R, et al. Structure and dynamics of a 197 bp nucleosome in complex with linker histone H1. Mol Cell. 2017;66:384–397. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochkareva E, Kaustov L, Ayed A, Yi GS, Lu Y, Pineda-Lucena A, Liao JC, Okorokov AL, Milner J, Arrowsmith CH, Bochkarev A. Single-stranded DNA mimicry in the p53 transactivation domain interaction with replication protein A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15412–15417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504614102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bréant B, Huet J, Sentenac A, Fromageot P. Analysis of yeast RNA polymerases with subunit-specific antibodies. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:11968–11973. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)44326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhler JM, Huet J, Davies KE, Sentenac A, Fromageot P. Immunological studies of yeast nuclear RNA polymerases at the subunit level. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:9949–9954. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)43484-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burley SK, Petsko GA. Amino-aromatic interactions in proteins. FEBS Lett. 1986;203:139–143. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabot PR, Raiola L, Lussier-Price M, Morse T, Arseneault G, Archambault J, Omichinski JG. Structural and functional characterization of a complex between the acidic transactivation domain of EBNA2 and the Tfb1/p62 subunit of TFIIH. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004042. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Dong L, Hu M, et al. Functions of FACT in breaking the nucleosome and maintaining its integrity at the single-nucleosome level. Mol Cell. 2018;71:284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway RC, Conaway JW. An RNA polymerase II transcription factor has an associated DNA dependent ATPase (dATPase) activity strongly stimulated by the TATA region of promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7356–7360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbeski I, Dolinar K, Wienk H, et al. DNA repair factor APLF acts as a H2A–H2B histone chaperone through binding its DNA interaction surface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:7138–7152. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P, Bushnell DA, Fu J, Gnatt AL, Maier-Davis B, Thompson NE, Burgess RR, Edwards AM, David PR, Kornberg RD. Architecture of RNA polymerase II and implications for the transcription mechanism. Science. 2000;288:640–649. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr N, de la Fuente C, Lecoq L, Guendel I, Chabot PR, Kehn-Hall K, Omichinski JG. A ΩXaV motif in the Rift Valley fever virus NSs protein is essential for degrading p62, forming nuclear filaments and virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:6021–6026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503688112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Río-Portilla F, Gaskell A, Gilbert D, Ladias JA, Wagner G. Solution structure of the hRPABC14.4 subunit of human RNA polymerases. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:1039–1042. doi: 10.1038/14923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lello P, Nguyen BD, Jones T, Potempa K, Kobor MS, Legault P, Omichinski JG. NMR structure of the amino-terminal domain from the Tfb1 subunit of TFIIH and characterization of its phosphoinositides and VP16 binding sites. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7678–7686. doi: 10.1021/bi050099s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lello P, Jenkins LM, Jones TN, Nguyen BD, Hara T, Yamaguchi H, Dikeakos JD, Appella E, Legault P, Omichinski JG. Structure of the Tfb1/p53 complex: insights into the interaction between the p62/Tfb1 subunit of TFIIH and the activation domain of p53. Mol Cell. 2006;22:731–740. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lello P, Miller Jenkins LM, Mas C, Langlois C, Malitskaya E, Fradet-Turcotte A, Archambault J, Legault P, Omichinski JG. p53 and TFIIEalpha share a common binding site on the Tfb1/p62 subunit of TFIIH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:106–111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707892105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecsédi P, Gógl G, Hóf H, Kiss B, Harmat V, Nyitray L. Structure determination of the transactivation domain of p53 in complex with S100A4 using annexin A2 as a crystallization chaperone. Structure. 2020;28:943–953.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnung L, Ochmann M, Engeholm M, Cramer P. Structural basis of nucleosome transcription mediated by Chd1 and FACT. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2021;28:382–387. doi: 10.1038/s41594-021-00578-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feaver WJ, Svejstrup JQ, Bardwell L, Bardwell AJ, Buratowski S, Gulyas KD, Donahue TF, Friedberg EC, Kornberg RD. Dual roles of a multiprotein complex from S. cerevisiae in transcription and DNA repair. Cell. 1993;75:1379–1387. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90624-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H, Jenkins LM, Durell SR, Hayashi R, Mazur SJ, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Miller M, Wlodawer A, Appella E, Bai Y. Structural basis for p300 Taz2-p53 TAD1 binding and modulation by phosphorylation. Structure. 2009;17:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fesquet D, Labbé JC, Derancourt J, Capony JP, Galas S, Girard F, Lorca T, Shuttleworth J, Dorée M, Cavadore JC. The MO15 gene encodes the catalytic subunit of a protein kinase that activates cdc2 and other cyclindependent kinases (CDKs) through phosphorylation of Thr161 and its homologues. EMBO J. 1993;12:3111–3121. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W, Wang Y, Allis CD. Histone and chromatin cross-talk. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:172–183. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formosa T, Winston F. The role of FACT in managing chromatin: disruption, assembly, or repair? Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:11929–11941. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara Y, Ichihashi M, Kano Y, Goto K, Shimizu K. A new human photosensitive subject with a defect in the recovery of DNA synthesis after ultraviolet-light irradiation. J Invest Dermatol. 1981;77:256–263. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12482447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuchi S, Sakamoto S, Nobe Y, Murakami SD, Amemiya T, Hosoda K, Koike R, Hiroaki H, Ota M. IDEAL:Intrinsically disordered proteins with extensive annotations and literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D507–D511. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa A, Wakamori M, Arimura Y, et al. Acetylated histone H4 tail enhances histone H3 tail acetylation by altering their mutual dynamics in the nucleosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:19661–19663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010506117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa A, Wakamori M, Arimura Y, et al. Characteristic H3 N-tail dynamics in the nucleosome core particle, nucleosome, and chromatosome. iScience. 2022;25:103937. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.103937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais V, Lamour V, Jawhari A, Frindel F, Wasielewski E, Dubaele S, Egly JM, Thierry JC, Kieffer B, Poterszman A. TFIIH contains a PH domain involved in DNA nucleotide excision repair. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:616–622. doi: 10.1038/nsmb782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill J, Kumar A, Sharma A. Structural comparisons reveal diverse binding modes between nucleosome assembly proteins and histones. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2022;15:20. doi: 10.1186/s13072-022-00452-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greber BJ, Nguyen THD, Fang J, Afonine PV, Adams PD, Nogales E. The cryo-electron microscopy structure of human transcription factor IIH. Nature. 2017;549:414–417. doi: 10.1038/nature23903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greber BJ, Toso DB, Fang J, Nogales E. The complete structure of the human TFIIH core complex. Elife. 2019;8:e44771. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha JH, Shin JS, Yoon MK, Lee MS, He F, Bae KH, Yoon HS, Lee CK, Park SG, Muto Y, Chi SW. Dual-site interactions of p53 protein transactivation domain with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins reveal a highly convergent mechanism of divergent p53 pathways. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:7387–7398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.400754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond CM, Strømme CB, Huang H, et al. Histone chaperone networks shaping chromatin function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:141–158. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanaoka S, Nagadoi A, Yoshimura S, Aimoto S, Li B, de Lange T, Nishimura Y. NMR structure of the hRap1 Myb motif reveals a canonical three-helix bundle lacking the positive surface charge typical of Myb DNA-binding domains. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:167–175. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanaoka S, Nagadoi A, Nishimura Y. Comparison between TRF2 and TRF1 on their telomeric DNA bound structures and DNA-binding activities. Protein Sci. 2005;14:119–130. doi: 10.1110/ps.04983705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Kodera N, Tsunaka Y, et al. Phosphorylation-coupled intramolecular dynamics of unstructured regions in chromatin remodeler FACT. Biophys J. 2013;104:2222–2234. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayami T, Kamiya N, Kasahara K, Kawabata T, Kurita JI, Fukunishi Y, Nishimura Y, Nakamura H, Higo J. Difference of binding modes among three ligands to a receptor mSin3B corresponding to their inhibitory activities. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6178. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85612-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Yan C, Fang J, Inouye C, Tjian R, Ivanov I, Nogales E. Near-atomic resolution visualization of human transcription promoter opening. Nature. 2016;533:359–365. doi: 10.1038/nature17970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higo J, Nishimura Y, Nakamura H. A Free-energy landscape for coupled folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein in explicit solvent from detailed all-atom computations. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:10448–10458. doi: 10.1021/ja110338e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata M, Kanematsu T, Takeuchi H, Yagisawa H. Pleckstrin homology domain as an inositol compound binding module. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1998;76:255–263. doi: 10.1254/jjp.76.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holla S, Dhakshnamoorthy J, Folco HD, et al. Positioning heterochromatin at the nuclear periphery suppresses histone turnover to promote epigenetic inheritance. Cell. 2020;180:150–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Dai Y, Zhou Z. Mechanistic and structural insights into histone H2A–H2B chaperone in chromatin regulation. Biochem J. 2020;477:3367–3386. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20190852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami K, Horigome D, Mukai M, et al. TTLL10 is a protein polyglycylase that can modify nucleosome assembly protein 1. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1129–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida M, Shimojo H, Hayashi A, Kawaguchi R, Ohtani Y, Uegaki K, Nishimura Y, Nakayama J. Intrinsic nucleic acid-binding activity of Chp1 chromodomain is required for heterochromatic gene silencing. Mol Cell. 2012;47:228–241. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Ono T, Yamaizumi M. A new UV-sensitive syndrome not belonging to any complementation groups of xeroderma pigmentosum or Cockayne syndrome: siblings showing biochemical characteristics of Cockayne syndrome without typical clinical manifestations. Mutat Res. 1994;314:233–248. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Fujiwara Y, Ono T, Yamaizumi M. UVs syndrome, a new general category of photosensitive disorder with defective DNA repair, is distinct from xeroderma pigmentosum variant and rodent complementation group I. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:1267–1276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeronimo C, Robert F. The histone chaperone FACT: a guardian of chromatin structure integrity. Transcription. 2022;13:16–38. doi: 10.1080/21541264.2022.2069995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeronimo C, Angel A, Nguyen VQ, et al. FACT is recruited to the +1 nucleosome of transcribed genes and spreads in a Chd1-dependent manner. Mol Cell. 2021;81:3542–3559. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemble DJ, McCullough L, Whitby FG, et al. FACT disrupts nucleosome structure by binding H2A–H2B with conserved peptide motifs. Mol Cell. 2015;60:294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Sturgill D, Sebastian R, et al. Replication stress shapes a protective chromatin environment across fragile genomic regions. Mol Cell. 2018;69:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krois AS, Ferreon JC, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Recognition of the disordered p53 transactivation domain by the transcriptional adapter zinc finger domains of CREB-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E1853–E1862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602487113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]