Abstract

A boy in early adolescence presented with a 1-week history of visual acuity impairment in his right eye (RE). Fundus examination of the RE revealed an elevated yellow-greyish lesion in the inferior temporal juxtafoveolar area. Findings on optical coherence tomography, fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography angiography were compatible with active choroidal neovascularisation (CNV). In the absence of a primary ocular pathology and a potential systemic secondary cause, it was assumed an idiopathic aetiology of CNV. The child was treated with intravitreal injections of aflibercept, showing good anatomical and functional responses. No complications were recorded after the injections. CNV in children is a rare ocular condition that can lead to permanent visual acuity impairment. Although the therapeutic approach remains controversial, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor intravitreal injections represent a safe and effective therapeutic option for CNV in children.

Keywords: Eye, Paediatrics (drugs and medicines), Macula, Retina, Paediatric prescribing

Background

Choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) is a rare cause of central visual loss in children, particularly with subfoveal lesions, which is the most frequent location.1–3

CNV is characterised by the growth of new blood vessels from the choroid that invade through defects on Bruch’s membrane extending into the subretinal space or the sub-retinal pigment epithelium (sub-RPE) space.4 Blood and fluid leaking from CNV lead to the death of photoreceptor cells.1

The most common causes of CNV in adults are exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and myopic fundus changes, which are rare in children.3 Unlike adults, the aetiology of paediatric CNV remains imprecise. Children often present with an underlying ocular disease that affects the integrity of the vulnerable area between the retina and choroid.2 However, the CNV aetiology is unclear in many cases.1 Inflammatory CNV has been reported to be the most common type of CNV in children and adolescents.3 Reported inflammatory causes of CNV in children and adolescents include ocular histoplasmosis syndrome, ocular toxoplasmosis, rubella retinopathy, sarcoidosis, ocular toxocariasis, Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome, chronic uveitis and serpiginous choroiditis.1 3 Some optic nerve anomalies are also associated with paediatric CNV, including optic nerve head drusen, optic nerve coloboma, optic nerve pit and morning glory syndrome.1 5 Chronic papilloedema and malignant hypertension can rarely cause peripapillary CNV.1 Paediatric CNV can also develop in several retinal dystrophies, including Best’s disease, Stargardt’s disease, Leber congenital amaurosis, retinitis pigmentosa, choroideraemia, North Carolina macular dystrophy, reticular dystrophy, butterfly-shaped dystrophy and gyrate atrophy.1 3 5 6 Other possible aetiologies include traumatic choroidal rupture, high myopia, angioid streaks and choroidal osteoma.2 3 Rarely, CNV has also been associated with handheld laser-induced maculopathy.7 CNV is considered idiopathic when there are no identifiable predisposing factors or ocular diseases, and these cases are usually unilateral.1

Presenting symptoms include blurred vision, central scotoma and metamorphopsia. Some cases can be asymptomatic and diagnosed during a routine eye examination.2 Younger children may not be able to complain, which can result in a later diagnosis at more advanced stages.

Few studies have been published about CNV in the paediatric population, and its therapeutic approach is controversial.2 3 5 8 9 Treatment options include photodynamic therapy (PDT), focal laser coagulation or intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections. Anti-VEGF agents have been increasingly used in several paediatric retinal and uveitic diseases, including CNV, with minimal side effects reported.10 However, no evidence-based treatment protocol exists for paediatric CNV, and there is limited information regarding the long-term safety profile in children. Due to the rarity of CNV in children, prospective randomised clinical trials are unexpected. Therefore, it is important to report individual data regarding children treated for CNV to collect more information about aetiological factors, clinical characteristics, treatment options and outcomes.

We report a case of a child with idiopathic CNV who was successfully treated with intravitreal injections of aflibercept.

Case presentation

A boy in early adolescence presented to the ophthalmology department with a 1-week history of visual acuity impairment in his right eye (RE). He denied ocular pain, myodesopsia, photopsia or recent trauma. The child was otherwise healthy. Ophthalmological history was irrelevant.

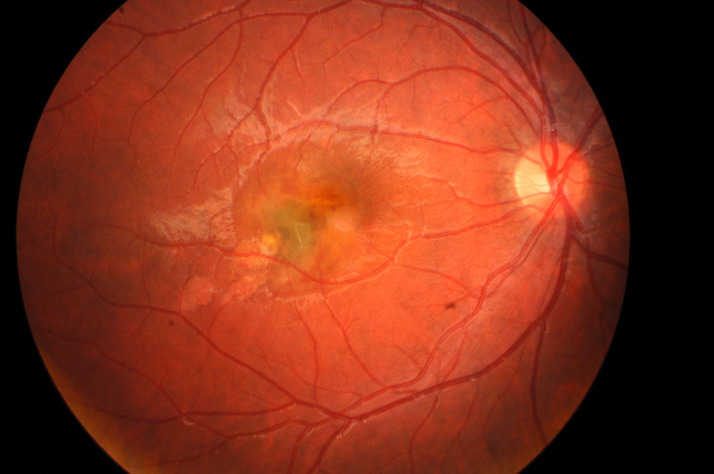

His uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) was 20/200 in the RE and 20/20 in the left eye (LE). Objective refraction was +0.25 dioptres (D) in the RE and +0.25 D in the LE. Further ophthalmological examination revealed isocoria, absence of relative afferent pupillary defect and no alterations in light pupillary reflexes or ocular movements. The anterior segment and intraocular pressure were bilaterally normal. Fundus examination of the RE revealed an elevated yellow-greyish lesion in the inferior temporal juxtafoveolar region of the macula and alteration of the foveal reflex (figure 1); LE fundus was normal.

Figure 1.

Initial retinography of the right eye showing choroidal neovascularisation in the inferior temporal juxtafoveolar area.

Investigations

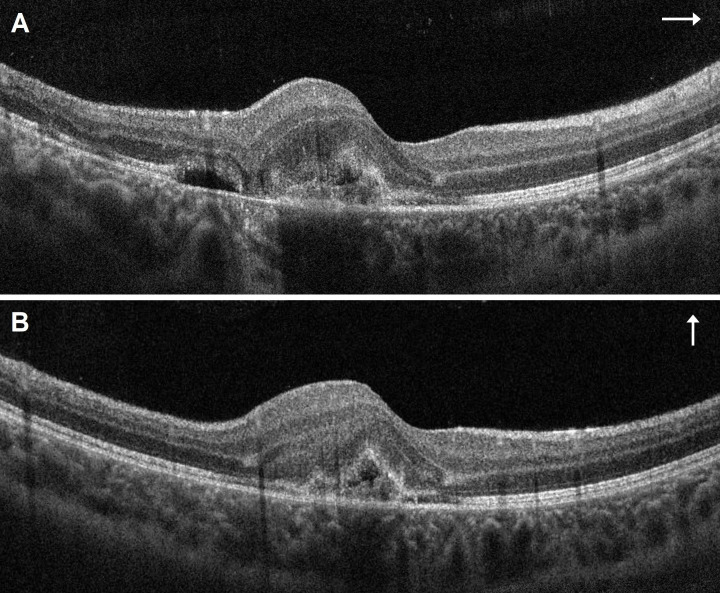

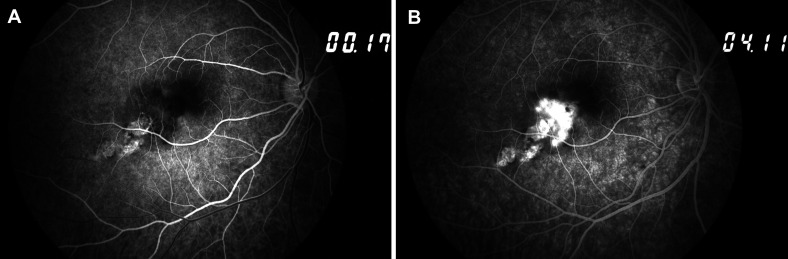

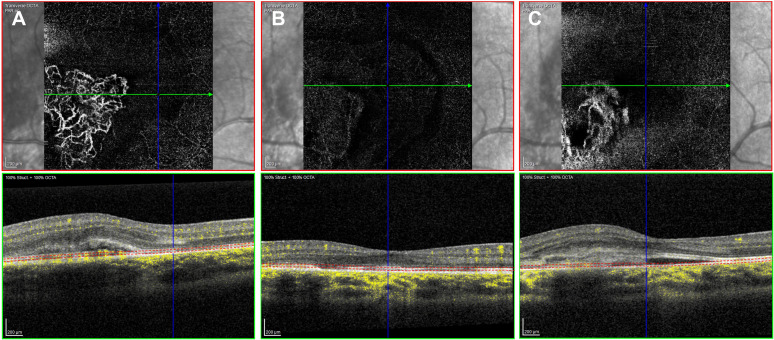

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging revealed a juxtafoveolar subretinal lesion with medium reflectivity and adjacent subretinal and intraretinal fluid in the RE (figure 2A, B), suggesting the presence of active type 2 CNV. Fundus fluorescein angiography (FA) revealed an early, well-defined hyperfluorescence during the arteriovenous phase and intense progressive leakage, compatible with classic active CNV (figure 3A, B). En face OCT angiography (OCTA) imaging demonstrated a glomerulus-shaped vascular complex in the outer retina (figure 4A).

Figure 2.

Initial spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the right eye: linear horizontal (A) and vertical (B) transfoveolar scan showing a significant thickening and increased volume of the macular area, a juxtafoveolar subretinal lesion with medium reflectivity, and associated subretinal and intraretinal fluid (type 2 choroidal neovascularisation).

Figure 3.

Initial fundus fluorescein angiography of the right eye showing early hyperfluorescence (A) and intense late leakage (B), corresponding to a classic active choroidal neovascularisation.

Figure 4.

En face optical coherence tomography angiography at presentation (A), showing a glomerulus-shaped active type 2 choroidal neovascularisation in the right eye. Regression of the vascular network 2 months after the second aflibercept intravitreal injection (B). Recurrence 4 months after treatment (C) (Courtesy of Ângela Carneiro, MD, PhD).

Systemic investigation for infectious and inflammatory causes was performed, including complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C reactive protein, renal function markers, angiotensin-converting enzyme, interferon-gamma release assay test and serologies for syphilis, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus and borrelia, which were all unremarkable except for an isolated slight elevation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (63.00 IU/L). A thoracic radiography was also performed and showed no alterations. A full body physical examination was performed by a paediatrician, detecting no relevant findings. The child presented no systemic signs or symptoms.

Differential diagnosis

OCT, FA and OCTA imaging allowed the diagnosis of unilateral active type 2 CNV in the RE. In the absence of a primary ocular pathology and a potential systemic secondary cause, it was initially assumed an idiopathic aetiology of CNV. Later during follow-up time, after an exhaustive systemic and ophthalmological history review, the patient described that he used to play with a handheld laser when he was about 6 years old. The child and his mother were unaware if there was accidental ocular exposure. The power of the laser was also unknown. This raised the hypothesis that the aetiology of CNV could be secondary to handheld laser-induced macular injury, which turned out to be the main differential diagnosis. CNV and disruption of the outer retinal layers have been described following laser injury.7 11 12 Like idiopathic CNV,1 3 5 8 laser-related CNV also tends to be unilateral,8 12–16 so both diagnoses are in accordance with our case. However, the unknown ocular exposure, the unknown power of the laser and the period of several years until clinical presentation make this hypothesis difficult to substantiate since it is based on assumptions.

Treatment

The case was discussed between paediatric ophthalmology and retina sections. Existing literature shows that anti-VEGF agents have increasingly been used for the treatment of CNV in children with favourable safety and efficacy profiles.2 9 10 17–19 Since there was no standardised treatment protocol for anti-VEGF injections for CNV in children, the anti-VEGF agent, the frequency of the injections and the interval between injections were chosen on the individual’s clinical response and the physician’s experience basis. Initially, we chose to treat the child with intravitreal injections of aflibercept (Eylea, 2 mg in 0.05 mL) at monthly intervals, considering that it is approved for the treatment of other forms of CNV in adults, namely neovascular AMD and myopic CNV, and considering the great experience of our centre in its use. The usual adult dosage was used since the child’s weight was >50 kg. The clinical situation and our off-label treatment proposal were explained to both the child and his mother, namely the lack of evidence-based standard procedures for idiopathic CNV in children. Both parties agreed with all measures. Written consents were signed by the child and his mother after explaining the procedure and clarifying their concerns. The intravitreal injections were performed under standard aseptic conditions in the operating room under brief general anaesthesia. No complications were recorded after the injections. The child was not enrolled in any clinical trial.

Outcome and follow-up

The child maintained a regular follow-up that included repeated UCVA evaluation, fundus examination, and OCT and OCTA imaging.

Two weeks after the first intravitreal injection of aflibercept, the RE showed both functional and anatomical good responses. UCVA improved from 20/200 to 20/25, and there was a pronounced reduction of macular oedema according to the OCT, with a reduction of the maximal macular thickness in the juxtafoveolar region from 493 μm to 371 µm. Two weeks after the second injection, UCVA remained unchanged, but there was complete resolution of the subretinal and intraretinal fluid according to the OCT, with a further reduction of the maximal macular thickness in the juxtafoveolar region to 338 µm. Since the two initial injections had been sufficient for achieving disease regression, we chose to discontinue the treatment and observe. Two months after the second injection, there was further improvement of UCVA to 20/20. Residual macular pigmentary alterations were visible on the fundus examination. OCTA reassessment revealed regression of the vascular network (figure 4B).

Four months after treatment, despite being asymptomatic, the child showed UCVA of 20/32 in the RE during a follow-up visit. RE fundus examination revealed a newfound perifoveal haemorrhage, and OCT imaging confirmed the recurrence of active CNV, with subretinal fluid and increased perifoveal thickness (482 µm). OCTA imaging demonstrated a recurring vascular complex in the outer retina (figure 4C). Then, he was treated with five more aflibercept injections, the first three at monthly intervals and the last two at 6 weeks intervals. The treatment was, once again, both anatomically and functionally effective. UCVA improved to 20/20 shortly after the new course of injections. Complete subretinal fluid resorption was observed, and macular thickness returned to normal values (319 µm of maximal macular thickness in the juxtafoveolar area). A stabilisation took place in long-term follow-up (>12 months). The LE remained unaffected through the follow-up period.

Discussion

Paediatric CNV is a rare ocular condition that exhibits several differences from CNV found in adults. Similar to our case, most cases reported in children are type 2 CNV, having features of classic CNV lesions on FA.2 3 Type 2 CNV typically occurs with a solitary or few ingrowth foci from a focal defect in Bruch’s membrane, which is more associated with localised disease processes.3 4 In contrast, most cases of CNV found in adults with AMD have multiple ingrowth foci, as these older patients often show diffuse retinal changes such as thickening and calcification of Bruch’s membrane or diffuse disruption of the RPE, which are absent in children.2 4 8 9 Therefore, paediatric CNV usually presents a more favourable prognosis with a high rate of spontaneous regression.3

Frequently, the aetiology of paediatric CNV is unclear and considered idiopathic.1 In our case, after an exhaustive anamnesis and complete ophthalmological and systemic examinations, the only clue for a potential cause was the possible exposure to a handheld laser several years before, which was not confirmed. Several reports have described the OCT findings of handheld laser-induced macular injury, including vertical hyper-reflective bands corresponding to retinal streaks, ellipsoid and external limiting membrane disruption, hyporeflective cavities, CNV, subhyaloid haemorrhage, macular hole and epimacular membrane formation.7 11 12 External retinal layers disruption was observed in our patient’s OCT imaging. These findings could possibly be secondary to laser injury, which was complicated by CNV formation. This hypothesis cannot be dismissed. Nevertheless, it does not alter the therapeutic approach.

The therapeutic approach to paediatric CNV remains controversial. It depends on the presence of underlying ocular diseases, as well as the activity and location of CNV.2 Since spontaneous regression is very common in paediatric CNV, observation may be a reasonable approach in some cases. However, Rishi et al noticed that the visual outcome in eyes with successfully treated subfoveal CNV was better than in eyes with spontaneously regressed subfoveal CNV.3 Laser photocoagulation is not suitable for juxtafoveal treatment because of the risk of inadvertent foveal injury, and the most frequent location of CNV in children is subfoveal.1–3 PDT can be a treatment option for subfoveal CNV in young patients. No significant systemic adverse effects are known, and functional results are consistently good; however, pronounced RPE alterations and atrophy can occur in some cases.1 Since the establishment of anti-VEGF agents for the treatment of several retinal vasculopathies in adults, they have also been increasingly used in children, with minimal immediate local and systemic effects observed.10 Some studies have reported that fewer injections of anti-VEGF agents are needed to control paediatric CNV compared with adults.2 6

No evidence-based treatment protocol has been established for children with CNV. In the current case report, two initial aflibercept injections were sufficient for CNV regression. However, recurrence of active disease occurred 4 months after the last injection, for which five more aflibercept injections were administered at gradually extended intervals. The usual adult dosage of aflibercept intravitreal injection was used, and no local or systemic complications were recorded during the follow-up time (>12 months). Excellent functional and anatomical responses were observed, with our patient exhibiting an improvement from an initial UCVA of 20/200 to a final UCVA of 20/20. These results are in accordance with other studies. Barth et al did not record any complications of treatment with intravitreal anti-VEGF agents (bevacizumab in five patients and ranibizumab in three patients).2 One patient received intravitreal aflibercept as a second-line treatment after intravitreal ranibizumab had failed. An average of 5.4±2.9 injections were needed to control the disease. Kozak et al studied 45 eyes from 39 children with CNV treated with anti-VEGF agents (bevacizumab in 40 eyes and ranibizumab in 5 eyes).17 No systemic or ocular complications were reported during the mean follow-up period of 14.1 months. Median visual acuity significantly improved from 20/150 to 20/100. Only nine eyes (20%) showed no improvement in visual acuity after treatment. In most patients (60%), a single anti-VEGF injection was sufficient to halt or stabilise the disease. Favourable outcomes were also reported in several case reports using intravitreal injections of bevacizumab18 and ranibizumab9 19 for the treatment of children presenting active CNV. None of these reported any drug-related ocular or systemic side effects.

Although anti-VEGF agents in children seem to be effective and innocuous at least at immediate and intermediate follow-up time, long-term data on the safety profile are lacking. VEGF is a key mediator of normal angiogenesis and is also involved in the regulation of vessel permeability and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier. The long-term consequences of inhibiting these functions with anti-VEGF treatments during paediatric age need to be further evaluated.3 The logistics involved in the administration of multiple intravitreal injections in children, which in most cases will require general anaesthesia, are also a concern.1

The current case report suggests that the use of anti-VEGF agents, namely aflibercept, can be a safe and effective therapeutic option for paediatric CNV. However, larger studies with longer follow-up times are required to assess the long-term efficacy and safety profile.

Learning points.

Paediatric choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) typically involves classic type 2, subfoveal membranes.

Paediatric CNV usually has a more favourable prognosis than CNV found in adults.

The aetiology of CNV in children frequently remains imprecise.

Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents have shown to be effective and safe for the treatment of CNV in children, but long-term safety data are needed.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors participated in the first evaluation, diagnosis or follow up of the patient. ARV wrote the manuscript and gathered the clinical information and images. CT, JL and MAO decided the treatment and supported the writing of the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained from parent(s)/guardian(s).

References

- 1.Sivaprasad S, Moore AT. Choroidal neovascularisation in children. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92:451–4. 10.1136/bjo.2007.124586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barth T, Zeman F, Helbig H, et al. Etiology and treatment of choroidal neovascularization in pediatric patients. Eur J Ophthalmol 2016;26:388–93. 10.5301/ejo.5000820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rishi P, Gupta A, Rishi E, et al. Choroidal neovascularization in 36 eyes of children and adolescents. Eye 2013;27:1158–68. 10.1038/eye.2013.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossniklaus HE, Green WR. Choroidal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;137:496–503. 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang T, Wang Y, Yan W, et al. Choroidal neovascularization in pediatric patients: analysis of etiologic factors, clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes. Front Med 2021;8:735805. 10.3389/fmed.2021.735805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philip S, Xu X, Laud KG, et al. Choroidal neovascularization in an adolescent with RDH12-associated retinal degeneration. Ophthalmic Genet 2019;40:362–4. 10.1080/13816810.2019.1655770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhavsar KV, Wilson D, Margolis R, et al. Multimodal imaging in handheld laser-induced maculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2015;159:227–31. 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veronese C, Maiolo C, Huang D, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography in pediatric choroidal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2016;2:37–40. 10.1016/j.ajoc.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krejčířová I, Autrata R, Vysloužilová D, et al. Idiopathic Chodoidal neovascular membrane in a 12-year-old girl. Cesk Slov Oftalmol 2019;74:249–52. 10.31348/2018/6/6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belin PJ, Lee AC, Greaves G, et al. The use of bevacizumab in pediatric retinal and choroidal disease: a review. Eur J Ophthalmol 2019;29:338–47. 10.1177/1120672119827773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alsulaiman SM, Alrushood AA, Almasaud J, et al. High-Power handheld blue laser-induced maculopathy: the results of the King Khaled eye specialist Hospital collaborative retina Study Group. Ophthalmology 2014;121:566–72. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujinami K, Yokoi T, Hiraoka M, et al. Choroidal neovascularization in a child following laser pointer-induced macular injury. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2010;54:631–3. 10.1007/s10384-010-0876-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu K, Chin EK, Quiram PA, et al. Retinal injury secondary to laser pointers in pediatric patients. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20161188. 10.1542/peds.2016-1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C, Li J, Chen X, et al. Laser-Induced choroidal neovascularization: a case report and some reflection on animal models for age-related macular degeneration. Medicine 2021;100:e26239. 10.1097/MD.0000000000026239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Z, Wen F, Li X, et al. Early subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to an accidental stage laser injury. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2006;244:888–90. 10.1007/s00417-005-0169-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nehemy M, Torqueti-Costa L, Magalhães EP, et al. Choroidal neovascularization after accidental macular damage by laser. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2005;33:298–300. 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.00993.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kozak I, Mansour A, Diaz RI, et al. Outcomes of treatment of pediatric choroidal neovascularization with intravitreal antiangiogenic agents: the results of the KKESH international collaborative retina Study Group. Retina 2014;34:2044–52. 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chhablani J, Jalali S. Intravitreal bevacizumab for choroidal neovascularization secondary to best vitelliform macular dystrophy in a 6-year-old child. Eur J Ophthalmol 2012;22:677–9. 10.5301/ejo.5000095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim R, Kim YC. Intravitreal ranibizumab injection for idiopathic choroidal neovascularization in children. Semin Ophthalmol 2014;29:178–81. 10.3109/08820538.2013.874470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]