Abstract

Objective

Early postnatal care service usage in developing countries is one of the healthcare service usage problems among postnatal women, which is related to extensive maternal and neonatal complications and mortality. Identification of the prevalence of early postnatal care services usage and associated factors among postnatal women is imperative to develop intervention measures to mitigate their complications and public health impact, which is not well known in Ethiopia, particularly in the selected study area. Thus, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of early postnatal care services usage and associated factors among postnatal women of Wolkite town, southeast Ethiopia.

Design

A community-based cross-sectional study design was conducted among 301 postnatal women from 15 May to 15 June 2021.

Measurements

Data were collected using a pretested structured questionnaire. The collected data were cleaned and entered in EpiData V.3.1 and then exported to SPSS V.23 for analysis. Finally, a multivariate logistic regression model was fitted to identify the factors associated with early postnatal care services usage. The p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The finding showed that the prevalence of early postnatal care services usage was 23.3% (95% CI 18.9% to 27.9%). Wanted pregnancy (adjusted OR (AOR)=4.17, 95% CI 1.93 to 9.03), had over four histories of pregnancy (gravida >4) (AOR=2.90, 95% CI 1.18 to 7.11) and had spontaneous vertex delivery (AOR=2.18, 95% CI 1.07 to 9.39) were statistically significant factors of early postnatal care service usage.

Conclusion

This study has shown that the prevalence of early postnatal care services usage was slightly low when compared with other studies. Thus, community-based health promotion should be an important recommendation to increase early postnatal care service usage among postnatal mothers to improve the level of awareness of early postnatal check-up schedules; done by healthcare providers.

Keywords: OBSTETRICS, HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT, HISTORY (see Medical History), Gynaecological oncology, Health & safety, Health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study includes mothers with birth within 1 year of the survey from the community to assess the prevalence of early postnatal care services usage and associated factors and compares them with other studies.

The limitation of this study related to the survey types and nature of the cross-sectional study, which did not draw inferences and show cause-and-effect relations among variables.

The sample size of this study was small, even if calculated by the scientific method.

The study is further limited because it is based on retrospective information provided by the survey respondents, which may be subject to recall bias.

However, such bias had tried to minimise some extent by restricting the study to mothers with birth within 1 year of the survey.

Introduction

Globally, approximately 810 women die every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth complications, 94% of the women’s death occur in low-income and middle-income countries.1 According to the WHO report, over 60% of the global maternal deaths occur in the postpartum period.2 Three-fourths of the maternal mortality occurred within the first week of delivery. The first 6 weeks (42 days) after giving birth is known as the postpartum period.3 4 The first week (7 days) is an intense time and requires much care for women and newborn babies. Early postnatal care (EPNC) refers to healthcare services provided to the mother and newborn baby by healthcare professionals within the first weeks after giving birth.2 5

Globally, 30% of the mothers follow postnatal care, thus 13% of the postnatal follow-up in sub-Saharan Africa.6 Research findings also showed that the prevalence of EPNC usage varied to a certain extent among regions in Africa. For instance, Uganda,7 and South Sudan,8 reported 15.4% and 11.4%, respectively. It also noted variations in research conducted in Ethiopia, like Southern Ethiopia at Hawassa Zuria,9 and Wonago district,10 North Ethiopia,11 reported 29.7%,13.7% and 34.3%, respectively.

Globally, every year, 3 million infants die in the first week of life, and 900 000 die in the next 3 weeks.12 13 According to a UNICEF report in Ethiopia, nearly 240 babies will die each day before reaching their first month of life.14 The Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2019 report, revealed that the neonatal mortality rate of the country is 29 deaths per 1000 live births,15 16 neonatal deaths occur at birth and early postnatal period due to inadequacy of care.17 18

In developing countries, different factors decrease EPNC services usage like home delivery, illiteracy, low income and cultures.19 20 This makes the EPNC services programme the weakest of all reproductive and child health programmes. Because of low adherence to recommended PNC regimens, women in sub-Saharan Africa posed a significant risk to infant and maternal morbidities and mortality.21

Despite the establishment of several global and national initiatives to improve maternal and child health, maternal mortality and mortality is continued as a global challenge.3 Early PNC (EPNC) service is the most important maternal and child healthcare service to detect early maternal and newborn danger signs and complications by healthcare providers.22

Even though there is a high prevalence of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality during the early postnatal period, it has done inadequate studies in underdeveloped and developing countries in Africa. In Ethiopia, there are different sociocultural beliefs and sociodemographic variations that affect healthcare services usage that creates evidence gaps between and within the population. However, the prevalence of EPNC services usage and associated factors among postnatal women were not well known in Ethiopia. Therefore this study should fill the evidence gap on EPNC service usage among postnatal mothers. Identification of factors associated with EPNC service usage among postnatal mothers is imperative to develop intervention strategies and measures to mitigate its public health impact. Thus, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of EPNC services usage and associated factors among postnatal women of Wolkite town.

Methods and materials

Study design and setting

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted from 15 May to 15 June 2021, at Wolkite Town, southern Ethiopia. Wolkite is the capital city of the Gurage zone. Wolkite town is located 158 km southwest of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. According to the 2007 Census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia, Wolkite town, has a total population of 28 856 of whom 15 068 were men and 13 788 women23 residents served by one public hospital, three health centres and nine private clinics.

Source and study population

Postnatal mothers aged 18 years with a birth within the last 12 months living in the town, and its selected subcities, were the source and study populations. We excluded individuals who gave birth over 12 months and were critically ill during the data collection period for the study.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the study

Sample size determination

The minimum sample size required for the study was determined by using a single population proportion formula with assumptions of 95% CI, 0.05 margin of error and established prevalence (p=23.7%) of EPNC service usage and its associated factors among mothers in Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama regional state, Ethiopia,9 with adding a 10% non-response rate. Based on the above assumption consideration the final sample size became (n=306).

Sampling techniques

We got the list of women who gave birth in the last 12 months from delivery registers and cross-checked it with the community health information system of health posts. Wolkite town has 11 kebeles, from that 4 were selected using the lottery method, and then a sample was allocated proportionally to the selected kebeles. After the proportional allocation of the sample for the selected kebeles, we employed a systematic random sampling technique to include 301 participants. The sampling fraction (K) was N/n=904/306=3. Then, the lottery method was employed to identify the first postnatal mother to be interviewed and three were drawn from whom the interview started. Postnatal women were identified, and we held an interview every three intervals. Five study participants were non-respondents after three consecutive home visits.

Data collection instruments and procedures

The data collection tool was prepared in English after reviewing related literature and translated into the Amharic language. The questionnaire comprised sociodemographic characteristics, obstetrics characteristics, service-related characteristics and sources of knowledge about EPNC (online supplemental Annex 1). Data were collected using a pretested structured interviewer-administered questionnaire. To assure the quality of data: Four diploma midwives had trained for data collection and two BSc midwives were assigned as a supervisor under the supervision of the principal investigator. Filled questionnaires were daily checked for completeness and consistency. Cronbach’s alpha value, which was 0.78, checked the reliability of the questionnaire.

bmjopen-2022-061326supp001.pdf (81KB, pdf)

Study variables and data measurement

The dependent variable was EPNC usage. Independent variables were as follows: sociodemographic characteristics (age, marital status, religion, ethnicity, educational level, occupational status, husband’s educational status, husband’s occupation, estimated monthly income and family size), obstetrics characteristics (gravidity, parity, having antenatal care (ANC) visit, number of visits, place of last ANC visit, course of pregnancy, place of delivery, delivery attendant, mode of delivery, birth outcome, any history of neonatal death, wantedness of pregnancy, getting advice on importance of PNC, maternal complication during postnatal period and newborns complication during pregnancy), service-related characteristics (means of transportation, decision-maker on maternity care, getting help for health services, maternity waiting room, duration of stay) and sources of knowledge (know the advantages of PNC, know the recommended postnatal visits, know the correct timing of PNC, knows that PNC is free service, knows at least one components of the service, knows at least one newborn danger signs, know consequences of not receiving recommended PNC, place where PNC is delivered).

EPNC usage

In this study, if a mother had at least one postnatal care check-up for the last delivery by skilled healthcare providers within 7 days after delivery, ‘Yes for early postnatal care utilization, otherwise no’.7 23 24

Skilled healthcare providers

Include (nurses, midwives, health officers, health extension workers and doctors).25

Data management and analysis

Data were cleaned and entered into EpiData V.3.1 and exported to SPSS V.23 for analysis. The data was cleaned by running frequency, checking missing values and the presence of outliers. We summarised the proportions of categorical variables by using mean with SD based on the distribution of data for continuous variables. Normality was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The factors associated with the dependent variable were analysed using binary logistic regression. Bivariate analysis, crude OR with 95% CI, was used to see the association between the outcome variable with each independent variable. Variables with a p value of ≤0.25 in the bivariate analysis were selected for the multivariable logistic regression model. Multicollinearity was checked to see the linear correlation among the independent variables. Model goodness of fitness was tested by Hosmer-Lemeshow statistics. The strength of the association between dependent and independent variables was assessed using an adjusted OR (AOR) with a 95% CI. The p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 301 study participants were involved in this study, with a response rate of 98.4%. the majority of the respondents 280 (93.0%) were married, 144 (47.8%) of the respondents were Orthodox religion followers, 275 (91.4%) were Gurage by ethnicity, 142 (47.2%) had no formal education, more than two-thirds, 188 (62.5%) of the participants were housewife, more than two-fifth, 129 (42.9%) of husbands of the respondents had no formal education, almost three-fourth, 225 (74.8%) of the respondents were farmers and nearly one-half, 149 (49.5%) of the respondents had income below the mean level (597.4 birrs). The minimum and maximum numbers of family sizes were 2 and 8, respectively, with a mean of 4± (SD of 1) (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of early postnatal care services usage among postnatal women in Wolkite town, southeast Ethiopia, 2021 (n=301)

| Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Age of the mother | ||

| Less than 20 | 22 | 7.3 |

| 20–34 | 206 | 68.4 |

| >35 | 73 | 24.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 280 | 93 |

| Unmarried | 13 | 4.3 |

| Divorced | 6 | 2.0 |

| Widowed | 2 | 0.7 |

| Religion | ||

| Orthodox | 144 | 47.8 |

| Muslim | 122 | 40.5 |

| Protestant | 31 | 10.3 |

| Catholic | 4 | 1.3 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Gurage | 275 | 91.4 |

| Amhara | 24 | 8.0 |

| Oromo | 2 | 0.7 |

| Educational status | ||

| No formal education | 142 | 47.2 |

| Grade 1–8 | 70 | 23.3 |

| Secondary 9–12 | 77 | 25.6 |

| College and above | 12 | 4.0 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Housewife | 188 | 62.5 |

| Civil servant | 11 | 3.7 |

| Merchant | 76 | 25.2 |

| Daily labourer | 18 | 6.0 |

| Farmer | 8 | 2.7 |

| Husband’s educational status | ||

| No formal education | 129 | 42.9 |

| Grade 1–8 | 108 | 35.9 |

| Secondary 9–12 | 53 | 17.6 |

| College and above | 11 | 3.7 |

| Husband’s occupation | ||

| Farmer | 225 | 74.8 |

| Civil servant | 13 | 4.3 |

| Merchant | 55 | 18.3 |

| Daily labourer | 8 | 2.7 |

| Monthly income | ||

| Below average (597.4 ETB) | 149 | 49.5 |

| More than average (597.4 ETB) | 152 | 50.5 |

| Family size | ||

| Less than average (4) | 154 | 51.2 |

| More than average (4) | 147 | 48.8 |

ETB, Ethiopian birr.

Obstetrics-related characteristics

Among the respondents, almost two-fifths, 119 (39.5%) had been pregnant for the first time and more than four-fifths, 268 (89.0%) had ANC visits. Of the ANC attendants, 83 (30.9%) have one ANC visit and 80 (29.8%) have four and above visits. Regarding the place of the last ANC visit, 208 (77.6%) was at the health centre. Related to the course of pregnancy, almost two-fifths, 112 (37.2%) of the respondents had a complicated pregnancy, four-fifths, 236 (78.4%) of the respondents were given birth at a health centre and most of the respondents, 284 (94.4%) were attended by health professionals. According to the mode of delivery, more than four-fifths, 254 (84.4%) of the respondents were delivered by spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD) (table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetrics characteristics of early postnatal care services usage among postnatal women in Wolkite town, Gurage zone, southeast Ethiopia, 2021 (n=301)

| Variables | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Gravidity | 1 | 119 | 39.5 |

| 2–4 | 106 | 35.2 | |

| >5 | 76 | 25.2 | |

| Parity | 1 | 119 | 39.5 |

| 2–4 | 106 | 35.2 | |

| >5 | 76 | 25.2 | |

| Having ANC visit | Yes | 268 | 89.0 |

| No | 33 | 11.0 | |

| Number of visits | One | 83 | 31 |

| Two | 55 | 20.5 | |

| Three | 50 | 18.6 | |

| Four and above | 80 | 29.8 | |

| Place of ANC visit | Health centre | 208 | 77.6 |

| Hospital | 51 | 19 | |

| Health post | 9 | 3.3 | |

| Course of pregnancy | Complicated | 112 | 37.2 |

| Uncomplicated | 189 | 62.8 | |

| Place of delivery | Health centre | 236 | 78.4 |

| Hospital | 50 | 16.6 | |

| Health post | 6 | 2.0 | |

| Home | 9 | 3.0 | |

| Delivery attendant | Health professionals | 284 | 94.4 |

| Health extension workers | 15 | 5.0 | |

| Others | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Mode of delivery | SVD | 254 | 84.4 |

| Instrumental delivery | 16 | 5.3 | |

| CS | 31 | 10.3 | |

| Birth outcome | Live birth | 292 | 97 |

| Stillbirth | 9 | 3.0 | |

| Any history of neonatal death | Yes | 10 | 3.3 |

| No | 291 | 96.7 | |

| Wantedness of pregnancy | Wanted | 222 | 73.8 |

| Unwanted | 79 | 26.2 | |

| Getting advice on the importance of PNC | Yes | 167 | 55.5 |

| No | 134 | 44.5 | |

| Maternal complications during the postnatal period | Yes | 55 | 18.3 |

| No | 246 | 81.7 | |

| Newborns complication during pregnancy | Yes | 84 | 27.9 |

| No | 217 | 72.1 |

ANC, antenatal care; CS, caesarean section; PNC, postnatal care; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

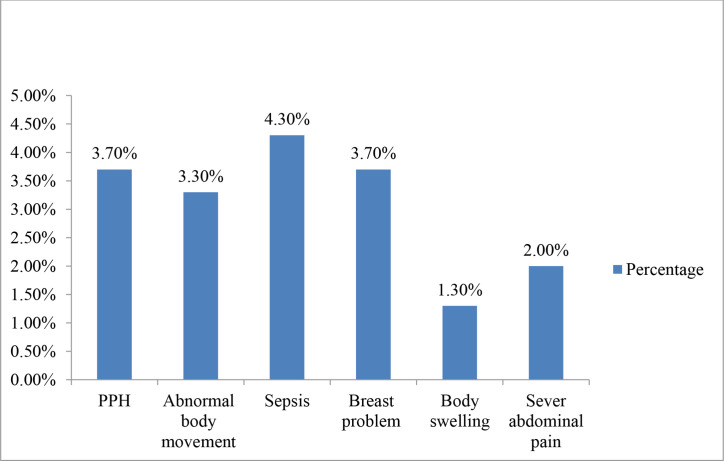

Maternal complications

Among the respondents, 18.3% had maternal complications during the early postnatal period. Of the complications 4.3% were sepsis, and 3.7% were postpartum haemorrhage (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Types of maternal complication among postnatal women in Wolkite town, southeast Ethiopia, 2021 (n=301). PPH, postpartum haemorrhage.

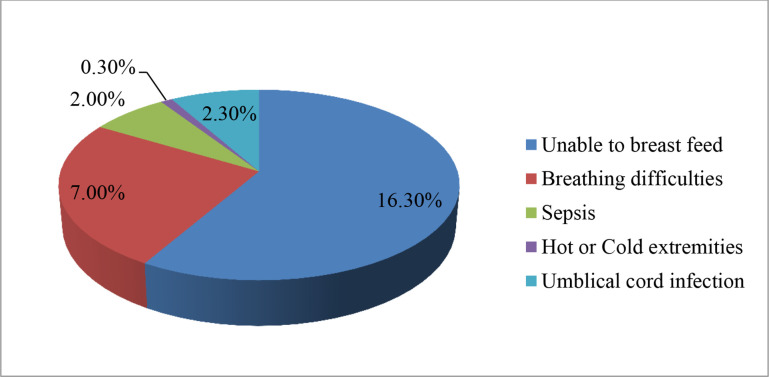

Newborn complications

Among the respondents, 27.9% had newborn complications during the early postnatal period. Of the complications, 16.3% were unable to breast feed, and 7% were having breathing difficulties (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Types of newborn complications during the postnatal period among postnatal women in Wolkite town, southeast Ethiopia, Ethiopia, 2021 (n=301).

Service-related characteristics

Among the respondents, more than two-thirds, 190 (63.1%) of the respondents travelled by foot to the health facility, while more than two-fifths, 141 (46.8%) of respondents decided by themselves to have early PNC. More than two-thirds, 228 (75.7%) of the respondents were getting help from their husbands about health services. Of those who used the maternity waiting room, 50 (16.6%) stayed for less than a week and 40 (13.3%) stayed for 1 week (table 3).

Table 3.

Service-related characteristics of early postnatal care services usage among postnatal women in Wolkite town, Gurage zone, southeast Ethiopia, 2021 (n=301)

| Variables | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Means of transportation | Foot | 190 | 63.1 |

| Vehicles | 111 | 36.9 | |

| Decision-maker on maternity care | Herself | 141 | 46.8 |

| Husband | 49 | 16.3 | |

| Joint decision | 111 | 36.9 | |

| Getting help for health services | Husband | 228 | 75.7 |

| Relatives | 65 | 21.6 | |

| Families | 8 | 2.7 | |

| Maternity waiting room | Yes | 90 | 29.9 |

| No | 211 | 70.1 | |

| Duration of stay (n=90) | Less than 1 week | 50 | 55.6 |

| For 1 week | 40 | 44.4 |

Sources of knowledge about early postnatal care.

Sources of knowledge about EPNC

Among the respondents, 220 (70.9%) have information about EPNC services. Most of the respondents, 150 (68.2%) acquired information about EPNC usage from television. Nearly one-fifth, 81 (26.9%) of the respondents did not know the advantages of postnatal care, and four-fifth, 243 (80.7%) of the respondents were aware of recommended postnatal visits. Nearly four-fifths, 256 (85.0%) of the respondents did not know the correct time of early PNC service usage. Nearly one-half, 133 (44.2%) of the respondents knew that EPNC was a free service, and nearly two-thirds, 188 (62.5%) of the respondents did not know at least one component of the service (table 4).

Table 4.

Knowledge about early postnatal care services usage among postnatal women in Wolkite town, southeast Ethiopia, 2021 (n=301)

| Variables | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Know the advantages of PNC | Yes | 220 | 73.1 |

| No | 81 | 26.9 | |

| Know the recommended postnatal visits | Yes | 58 | 19.3 |

| No | 243 | 80.7 | |

| Know the correct timing of PNC | Yes | 45 | 15.0 |

| No | 256 | 85.0 | |

| Knows that PNC is a free service | Yes | 133 | 44.2 |

| No | 168 | 55.8 | |

| Knows at least one component of the service | Yes | 113 | 37.5 |

| No | 188 | 62.5 | |

| Knows at least one newborn danger signs | Yes | 150 | 49.8 |

| No | 151 | 50.2 | |

| Know the consequences of not receiving recommended PNC | Yes | 48 | 15.9 |

| No | 253 | 84.1 | |

| Place where PNC is delivered | Yes | 102 | 33.9 |

| No | 199 | 66.1 |

PNC, postnatal care.

Factors associated with EPNC service usage among participants

On bivariate analysis monthly income, gravidity, parity, the desire of pregnancy, ANC follow-up, mode of delivery, any newborn illness/complication, obstetrics complication and knowledge of PNC were candidates for multivariate analysis. On multivariable analysis gravidity, the desire for pregnancy and mode of delivery were statistically significant in the final model (table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with early postnatal care services usage among postnatal women in Wolkite town, southeast Ethiopia, 2021 (n=301)

| Variables | EPNC usage | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Yes | No | ||||

| Estimated monthly income | |||||

| Below average | 43 | 106 | 1 | 1 | |

| >Average | 75 | 77 | 2.40 (1.49 to 3.87) | 1.22 (0.67 to 2.23) | 0.517 |

| Gravidity | |||||

| 1 | 31 | 88 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2–4 | 41 | 65 | 1.79 (1.02 to 3.15) | 1.22 (0.54 to 2.77) | 0.629 |

| More than 4 | 46 | 30 | 4.35 (2.35 to 8.06) | 2.90 (1.18 to 7.11) | 0.020 |

| Parity | |||||

| Primiparous | 35 | 84 | 1 | 1 | |

| Multiparous | 41 | 65 | 1.51 (0.87 to 2.64) | 1.18 (0.51 to 2.76) | 0.699 |

| Grand Multiparous | 42 | 34 | 2.97 (1.63 to 5.40) | 1.09 (0.46 to 2.62) | 0.844 |

| Desire of pregnancy | |||||

| Yes | 103 | 119 | 3.69 (1.98 to 6.87) | 4.17 (1.93 to 9.03) | 0.0001 |

| No | 15 | 64 | 1 | 1 | |

| Having ANC follow-up | |||||

| Yes | 111 | 157 | 2.63 (1.10 to 6.26) | 0.39 (0.12 to 1.28) | 0.121 |

| No | 7 | 26 | 1 | 1 | |

| Course of pregnancy | |||||

| Complicated | 60 | 52 | 2.61 (1.61 to 4.23) | 1.57 (0.85 to 2.92) | 0.151 |

| Uncomplicated | 58 | 131 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mode of delivery | |||||

| SVD | 107 | 147 | 2.38 (1.04 to 6.01) | 2.18 (1.07 to 9.39) | 0.038 |

| CS | 11 | 36 | 1 | 1 | |

| Any newborn illness/complication | |||||

| Yes | 42 | 42 | 1.85 (1.11 to 3.09) | 1.59 (0.84 to 2.99) | 0.155 |

| No | 76 | 141 | 1 | 1 | |

| Obstetrics complication | |||||

| Yes | 41 | 14 | 6.43 (1.01 to 9.48) | 9.12 (0.34 to 12.53) | 0.0001 |

| No | 77 | 169 | 1 | 1 | |

| Knowledge on PNC | |||||

| Poor | 45 | 115 | 1 | 1 | |

| Good | 73 | 68 | 2.74 (1.70 to 4.42) | 1.86 (0.99 to 3.49) | 0.051 |

*P value<0.05.

†P value≤0.01.

ANC, antenatal care; AOR, adjusted OR; COR, crude OR; CS, caesarean section; EPNC, early postnatal care; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Multivariable analysis

Of the total participants, 76 (25.2%) had more than four pregnancies and were 2.90 times (AOR: 2.90; 95% CI 1.18 to 7.11) more likely to use EPNC when compared with women who had less than or equal to four pregnancies. On the other hand, participants who have the desire for pregnancy were 4.17 times (AOR: 4.17; 95% CI 1.93 to 9.03) more likely when compared with those who have not the desire for pregnancy. On the other hand, participants who gave birth by SVD were 2.18 times (AOR: 2.18; 95% CI 1.07, 9.39) more likely when compared with those who gave birth by caesarean section.

Discussion

EPNC service usage in developing countries is one of the healthcare service usage problems among postnatal women, which is related to extensive maternal and neonatal complications and mortality.1 2,6 Prior studies have noted the importance of early postnatal check-ups in improving maternal survival.7 8 This study was intended to identify the prevalence of EPNC services usage and associated factors among postnatal women in Wolkite, Ethiopia.

This study revealed that 23.3% (95% CI 18.9% to 27.9%) of women received EPNC. This result is lower than the study reported in some African countries such as Myanmar (72.1%),26 Zambia (63%),27 Builsa district (62%),28 Hadiya zone (51.4%),29 Uganda (50%),7 Assela town (37.5%),30Adigrat town (34.3%)11and Debremarkos town (33.5%).31 However, it is higher than the findings of studies conducted in China (17%),32 Tanzania (10.4%),33 South Sudan (11.4%)and 8 Debremarkos town in Ethiopia (16.2%).31 The difference might be due to the analysis type employed in the studies and the sociocultural background of the participants.

In this study, wanted pregnancy was found to be an associated factor of EPNC services usage. This finding is nearly similar to the studies conducted in Tanzania and Benin.33 34 The various advantages of public enlightenment could explain this in planning for pregnancy. The difference between studies might be sample size; the sample size of this study was small, even if it was scientifically calculated; which might make variables insignificant.

This study revealed that having over four previous pregnancies was among the factors associated with EPNC services usage. This shows that former pregnancies shared the experience of attending early postnatal checkups. This finding differed from that of the studies conducted in Debre Birhan,35 and Mekele city,36 that study shows that mothers having one previous pregnancy used early PNC services on time. Sociocultural differences study participants between the studies might attribute the differences between the studies. This may affect the decision power of women to use this service in some communities.

This study revealed that SVD was among the factors associated with EPNC services usage. Similarly, a study conducted by Debre Birhan and Debremarkos shows that clients who have previous experience with SVD were more likely to use EPNC services.31 35 The difference between the studies might be attributed to sampling techniques and cultural differences of study participants; those studies used a simple random sampling technique.

Strengths and limitations

This study includes mothers with birth within 1 year of the survey from the community to assess the prevalence of EPNC services usage and associated factors and compare them with other studies.

It may relate the limitation of this study to the survey types and nature of the cross-sectional study, which did not draw inferences and show cause-and-effect relations among variables. The sample size of this study was small, even if it was scientifically calculated. The study is further limited because it is based on retrospective information provided by the survey respondents, which may be subject to recall bias. However, such bias was tried to minimise some extent by restricting the study to mothers with birth within 1 year of the survey.

Conclusions

This study illustrates the prevalence of EPNC services usage and the associated factors among postnatal women. This study revealed that the prevalence of EPNC services usage was slightly low when compared with other studies. Wanted pregnancy, having over four previous pregnancies (gravida >4) and SVD were significantly associated with EPNC services usage.

This study result revealed that almost all study participants’ place of delivery was in a health institution, and only 15% of the respondents know the correct follow-up schedules for early postnatal checkups, which is in contrast to the place of delivery. Thus, community-based health promotion should be an important recommendation to increase EPNC service usage among postnatal mothers to improve the level of awareness of early postnatal check-up schedules; done by healthcare providers.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Planning: YY, MD, SA, MS. Methodology: YY, MD, SA. Data curation: FW, SG, AB. Formal analysis: YY, MD, SA. Investigation: YY, MD, SA. Software: YY, MD. Supervision: FW, SG, AB. Validation: YY, MD, SA. Visualisation: MD, SA, SG. Writing—review and editing: YY, MD.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Extra data can be accessed via https://zenodo.org/record/7404686%23.Y4819r1KjIV.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval: We got ethical clearance from the institutional review board of Wolkite University College of Medicine and Health Science with the reference number RCSUILC/021/2021. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.WHO . Trends in maternal mortality, 2018. Available: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/793971568908763231/pdf/Trends-in-maternal-mortality-2000-to-2017-Estimates-by-WHO-UNICEF-UNFPA-World-Bank-Group-and-the-United-Nations-Population-Division.pdf

- 2.WHO . Who recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . World bank group, and the United nations population division. trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015. estimates by who, UNICEF. Geneva: UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization WH . Health in 2015: from MDGs, millennium development goals to SDGs, sustainable development goals, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . Postnatal care for mothers and newborns highlights from the world Health organization 2013 guidelines, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odukogbe A-TA, Afolabi BB, Bello OO, et al. Female genital mutilation/cutting in Africa. Transl Androl Urol 2017;6:138–48. 10.21037/tau.2016.12.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. USAID'S. Determinants of early postnatal care attendance in Uganda, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izudi J, Akwang GD, Amongin D. Early postnatal care use by postpartum mothers in Mundri East County, South Sudan. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:442. 10.1186/s12913-017-2402-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoseph S, Dache A, Dona A. Prevalence of early Postnatal-Care service utilization and its associated factors among mothers in Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama regional state, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Obstet Gynecol Int 2021;2021:1–8. 10.1155/2021/5596110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tefera Y, Hailu S, TilahunaR. A community-based cross-sectional study. In: Early postnatal care service utilization and its determinants among women who gave birth in the last 6 months in Wonago district South Ethiopia, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebreslassie Gebrehiwot T, Mekonen HH, Hailu Gebru T, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of early postnatal care service use among mothers who had given birth within the last 12 months in Adigrat town, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, 2018. Int J Womens Health 2020;12:869–79. 10.2147/IJWH.S266248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO . Who technical consultation on postpartum and postnatal care, 2018. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70432/WHO_MPS_10.03_eng.pdf;jsessionid=977EC87BBE162C1694EBAB559E4D335A?sequence=1 [PubMed]

- 13.Countdown to 2030 Collaboration . Countdown to 2030: tracking progress towards universal coverage for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health. Lancet 2018;391:1538–48. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30104-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNICEF. . Maternal and newborn health disparities in Ethiopia, UNICEF for every child, 2017. Available: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/country_profiles/Ethiopia/country%20profile_ETH.pdf [Accessed 28 Nov 2018].

- 15.CSAE . Central statistics agency of Ethiopia, Ethiopia demographic and health survey. 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO . Global strategies for women, children, and adolescents 2016-2030. 2016, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, et al. Evidence-Based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet 2005;365:977–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO/UNICEF . Home visits for the newborn child: a strategy to improve survival, 2010;. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70002/WHO_FCH_CAH_09.02_eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 28 Nov 2018]. [PubMed]

- 19.DiBari JN, Yu SM, Chao SM, et al. Use of postpartum care: predictors and barriers. J Pregnancy 2014;2014:1–8. 10.1155/2014/530769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Organization WH . Every newborn: an action plan to end preventable deaths, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO . Who recommendations on maternal health: guidelines Approved by the who guidelines review Committee, 2017. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259268/WHO-MCA-17.10-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 28 Nov 2018].

- 22.WHO . Technical consultation on postpartum and postnatal care, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AN T, D N, A T. Early postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in the last 12 months in Aseko district, Arsi zone, South East Ethiopia in 2016. J Womens Health Care 2017;06. 10.4172/2167-0420.1000358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ndugga P, Namiyonga NK, Sebuwufu D. Determinants of early postnatal care attendance: analysis of the 2016 Uganda demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:163. 10.1186/s12884-020-02866-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.EDHS . Ethiopia demographic and health survey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mon AS, Phyu MK, Thinkhamrop W. Women and its determinants: a cross-sectional study, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chungu C, Makasa M, Chola M, et al. Place of delivery associated with postnatal care utilization among childbearing women in Zambia. Front Public Health 2018;6:94. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakeah E, Aborigo R, Sakeah JK, et al. The role of community-based health services in influencing postnatal care visits in the Builsa and the West Mamprusi districts in rural Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:295. 10.1186/s12884-018-1926-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belachew T, Taye A, Belachew T. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among mothers in Lemo Woreda, Ethiopia. J Womens Health Care 2016;5:2167–420. 10.4172/2167-0420.1000318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Amane Tumbure1 DA, Elile Fantahun1, Megersa Negusu1. Assessment of postnatal care service utilization and associated factors in Asella town, Arsi zone, Oromiya regional state, Ethiopia. Global Journal of Reproductive medicine 2018;6. 10.19080/GJORM.2018.06.555678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Limenih MA, Endale ZM, Dachew BA. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among women who gave birth in the last 12 months prior to the study in Debre Markos town, northwestern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Med 2016;2016:1–7. 10.1155/2016/7095352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.You H, Chen J, Bogg L, et al. Study on the factors associated with postpartum visits in rural China. PLoS One 2013;8:e55955. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanté AM, Chung CE, Larsen AM, et al. Factors associated with compliance with the recommended frequency of postnatal care services in three rural districts of Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:341. 10.1186/s12884-015-0769-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dansou J, Adekunle AO, Arowojolu AO. Factors associated with the compliance of recommended first postnatal care services utilization among reproductive age women in Benin Republic: an analysis of 2011/2012 BDHS data. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 2017;6:1161–9. 10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20171378 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akibu M, Tsegaye W, Megersa T, et al. Prevalence and determinants of complete postnatal care service utilization in northern Shoa, Ethiopia. J Pregnancy 2018;2018:1–7. 10.1155/2018/8625437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gebrehiwot G, Medhanyie AA, Gidey G, et al. Postnatal care utilization among urban women in northern Ethiopia: cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health 2018;18:78. 10.1186/s12905-018-0557-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-061326supp001.pdf (81KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Extra data can be accessed via https://zenodo.org/record/7404686%23.Y4819r1KjIV.