Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to identify commonly used classification systems by cleft providers around the world, including the perceived indications and limitations of each system.

Design

A cross-sectional survey.

Participants

A total of 197 registrants from three international cleft/craniofacial meetings.

Interventions

Participants were sent a web-based questionnaire concerning cleft classification systems.

Main Outcome Measures

Frequency of commonly used classification systems, their perceived indications and limitations.

Results

A total of 197 respondents from 166 different centers completed the questionnaire. Healthcare professionals from all disciplines responded, with the most frequent respondents being plastic surgeons (38.1%), maxillofacial surgeons (28.4%) and orthodontists (23.9%). Eighteen different classification systems were in use. The most frequently used systems were the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) (35.5%), LAHSHAL (34.0%), and Veau (32.5%) classification systems. Most respondents (32.5%) indicated that anatomical and morphological characteristics are essential components of a classification system. However, respondents indicated that their current classification systems lacked sufficient description of cleft extension and severity.

Conclusions

Great variety in the use of classification systems exists among craniofacial specialists internationally. The results recommend the usage of the LAHSHAL classification of OFCs, due to its comprehensiveness, relatively high implementation rate globally, convenience of usage and complementarity with the ICD-10 system. Moreover, it can overcome deficiencies inextricably linked to ICD-10, such as incapacity to describe laterality and clefts of the alveolus. More international exposure to the merits of using the LAHSHAL classification system would be highly recommended.

Keywords: Classification system, cleft lip, cleft palate, orofacial cleft, survey

Introduction

Orofacial clefts (OFCs) are the most common type of craniofacial anomaly, occurring in approximately 1:700 live births (Calzolari et al., 2007; Mossey and Modell, 2012; Mai et al., 2019; World Health Organization, 2021a). OFCs can have a profound impact on a person's quality of life, which can lead to problems with feeding, speech (eg velopharyngeal insufficiency), hearing (eg recurring otitis media), dentition (eg tooth decay), neurodevelopmental disorders, psychological aspects and socialization (Gomes et al., 2009; Wehby and Cassell, 2010; Smallridge et al., 2015; Waylen et al., 2015; Tillman et al., 2018). The physiological severity of these problems is not correlated with the severity and location of the cleft. However, accurate cleft classification is essential for predicting treatment need, planning clinical interventions and evaluating treatment outcomes. Consequently, classifying clefts in a clear, easy to understand and concise manner is a key element of cleft care.

Cleft classification also plays an important role in studying the epidemiology of OFCs. OFCs are etiologically heterogeneous, and untangling the interactions of environmental and genetic risk factors leading to OFCs requires accurate classification of cleft type (Dixon et al., 2011). More specific classification systems enable greater subgrouping of clefts, which can facilitate identification of the causes and biologic mechanisms for OFCs. The value of cleft classification to epidemiology is perhaps best illustrated by the different recurrence risks for cleft lip alveolus, cleft lip alveolus and palate and cleft palate, which is a key difference used in genetic counseling (Sivertsen et al., 2008; Grosen et al., 2010). A standardized, accurate phenotypic classification of clefts is thus crucial to understand the epidemiology of OFCs.

During the history of cleft care, many classification systems have been developed and implemented. New classification systems have often been developed to classify clefts more accurately or to overcome limitations of existing systems. For example, the Veau classification system was developed as a response to the Brophy classification system, since Brophy was considered too complex and impractical (Allori et al., 2017). Another classification system is that of Fogh-Andersen, which was designed from an embryological point of view (Fogh-Andersen, 1971; Allori et al., 2017). Fogh-Andersen found that the alveolar process as a marking point was too arbitrary and suggested to use the incisive foramen instead. In 1989, the LAHSHAL recording system or registration system was designed for paraphrasing cleft lip and palate in which a distinction could be made between unilateral and bilateral clefts and to describe the extent of clefting (ie total vs subtotal clefts) (Kriens, 1989). While each of these classification systems provided value, none achieved universal acceptance among providers.

More recently, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) system has been promoted for both epidemiology and reimbursement (World Health Organization, 2021b). The ICD system is used in the WHO Global Burden of Disease (GBD) project, which has made reporting by ICD codes required for most governmental health registries (Truelsen et al., 2015; World Health Organization, 2021c). Healthcare payers in both Europe and North America have also mandated use of the ICD system for reimbursements. These two forces have led to broad implementation of the ICD system, despite concerns with its lack of specificity, mutual exclusivity, and comprehensiveness for classifying OFCs.

It is prudent to make a difference between registration and classification of clefts. For example, the ICD-10 classification, although described as a “classification”, is actually a registration process for coding and categorization of disease as opposed to being designed for the primary purpose of classification per se. This article makes no particular distinction between registration and classification systems.

As a result of great variety in possible classification systems, craniofacial specialists often use different classification systems. This hampers mutual understanding, communication and treatment outcome comparison among specialists and prevents the development of a uniform prevalence/incidence system. The aim of this article is to describe which classification systems are used globally, including their perceived indications and limitations. Furthermore, it aims to make a recommendation on which system is most suitable for global implementation so development of a global prevalence system and improvement of scientific data comparison is achievable.

Methods

This study was a cross-sectional survey. A questionnaire was sent to 2140 registrants of the 2015 Cleft Craniofacial meeting in Gothenburg, Sweden, the 2017 13th International Cleft Meeting in Chennai, India, and the 2019 European Cleft Palate Craniofacial Association (ECPCA) meeting in Utrecht, the Netherlands. The questionnaire was also sent to American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association (ACPA) members through the ACPA member portal and to members of the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) Action and members of the European Cleft and Craniofacial Initiative for Equality in Care (ECCE).

The questionnaire comprised a combination of 20 multiple choice and open-ended questions investigating the use of cleft classification systems and specific reasons why craniofacial specialists opt for these classification systems (Supplementary data file 1). The respondents were asked to specify the limitations of their preferred system and to identify the elements they believed were essential in the ideal cleft classification system. The questionnaire was designed and distributed using SurveyMonkey, an online survey application. Responses were gathered anonymously. A reminder was sent 14 days after the initial invitation.

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist was adhered to while preparing this manuscript. Numbers and percentages are obtained from SurveyMonkey and bar charts were designed using SPSS (Statistical Program for Social Sciences, version 26; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software. Approval of the Institutional Review Board was received.

Results

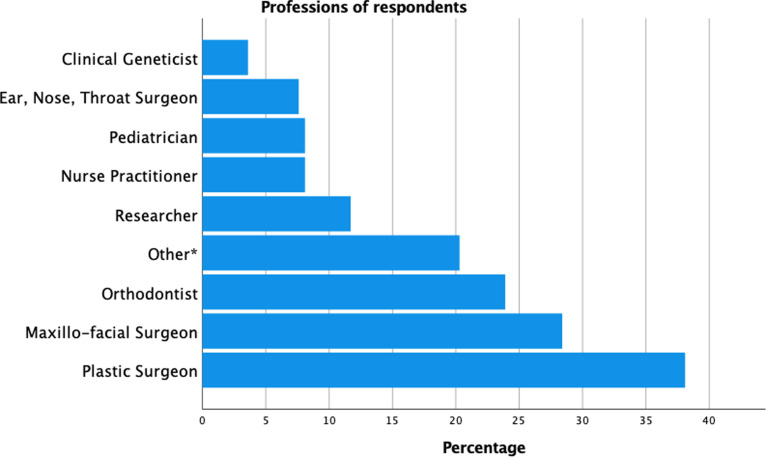

A total of 197 respondents from 166 cleft centers and 61 countries completed the questionnaire between September 1, 2020 and October 31, 2020. Most respondents originated from Europe (50.0%), Asia (21.8%) and North America (13.2%) (Supplementary data file 2). Respondents included providers from a range of functions with the most frequent being plastic surgeons (38.1%), maxillofacial surgeons (28.4%), and orthodontists (23.9%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of professions among respondents. † Note that the sum of the number of professions is greater than 197 and subsequently exceeds 100%. The reason for this is that quite often respondents answered the survey on behalf of their entire cleft care team and filled in multiple professions.

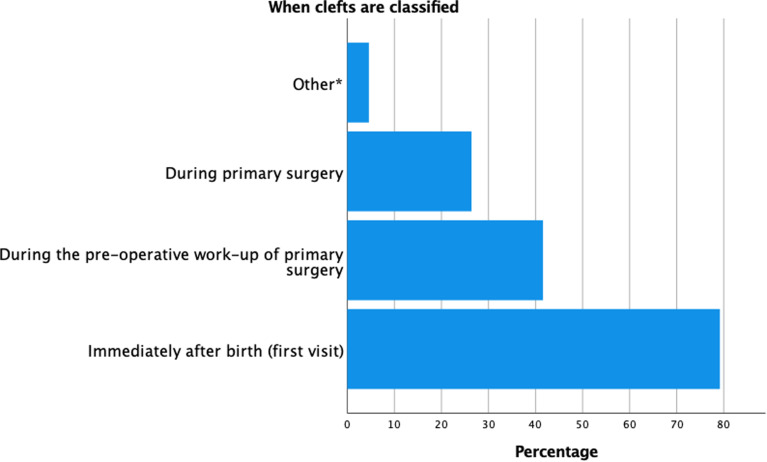

The majority of respondents noted that the registration/classification was done multiple times during cleft management. Seventy-nine percent of the respondents classified clefts at the first visit, 41.6% during the pre-operative work-up, and 26.4% re-evaluated the classification during primary surgery (Figure 2). Fifty-four percent of the respondents noted that the classification is mainly performed by a specific specialist, primarily by plastic surgeons, maxillofacial surgeons or cleft surgeons. Furthermore, according to 81.2% of respondents, classification was done for both clinical and research purposes. Forty-two percent of the respondents stated that they also classify clefts for a national registration and 25.4% classified for reimbursement purposes.

Figure 2.

Timing of classifying clefts among respondents.

Abbreviations: SABG; secondary alveolar bone grafting.

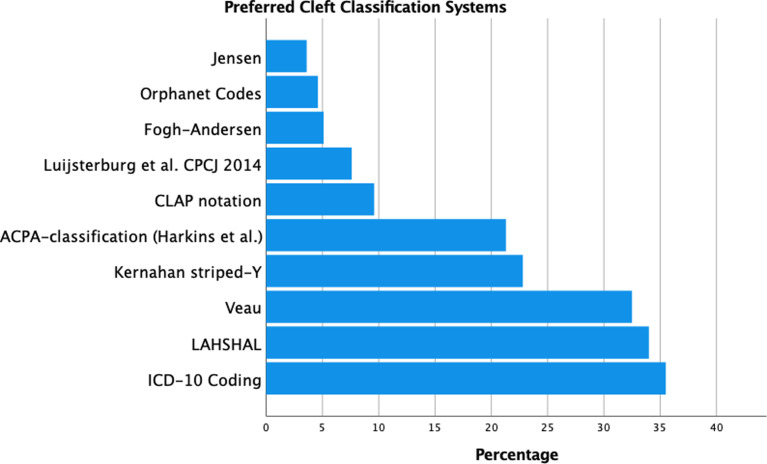

The most frequently employed classification systems were ICD-10 (35.5%), followed by LAHSHAL (34%), Veau (32.5%), Kernahan's striped-Y (22.8%) and the ACPA classification (Harkins et al., 1962) (21.3%) (Figure 3). A great variety existed in which classification systems were preferred both nationally and internationally, as shown in Table 1. Respondents from the United Kingdom were most homogenous in classifying clefts: 93.3% (14/15) respondents from the UK stated that they used LAHSHAL, since this was required for their national registry (CRANE, 2021). Multiple respondents reported that ICD-10 was required for reimbursement and registration purposes. Besides the ten classification systems proposed in our survey, respondents also indicated that another eight classification systems were used (Supplementary data file 3).

Figure 3.

Preferred classification systems among respondents. It was possible for the participants to choose multiple systems. Abbreviations: ACPA; American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association; ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision.

Table 1.

Systems Used in Countries With Five or More Respondents. Expressed in Number of Respondents.a.

| LAHSHAL | Veau | Fogh-Andersen | Kernahan's striped-Y | ACPA (Harkins et al.) | CLAP notation | ICD-10 | Orphanet codes | Jensen | Luijsterburg et al., CPCJ 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India (n = 24) | 3 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 1 | . | 1 | 2 |

| USA (n = 19) | 3 | 13 | . | 1 | 8 | 5 | 13 | . | 1 | . |

| UK (n = 15) | 14 | 1 | . | . | 1 | 1 | 1 | . | . | 1 |

| Germany (n = 10) | 8 | . | 1 | . | . | . | 6 | 1 | . | . |

| Netherlands (n = 10) | 1 | 4 | . | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | . | . | 7 |

| Sweden (n = 9) | . | 3 | 1 | 2 | . | . | 6 | 1 | . | . |

| Indonesia (n = 8) | 3 | 2 | . | 1 | . | 2 | 4 | . | . | 1 |

| Switzerland (n = 6) | 6 | . | 1 | . | 1 | . | . | 1 | . | . |

| Egypt (n = 5) | 1 | . | . | 4 | 1 | . | . | . | . | . |

| France (n = 5) | . | 3 | . | . | . | . | 2 | 3 | . | 1 |

Abbreviations: ACPA: American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association; CLAP: cleft lip, alveolus and palate; CPCJ: Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal; ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision; LAHSHAL: lip, alveolus, hard palate, soft palate, hard palate, alveolus, lip.

Note that several participants responded to this question with multiple classification systems. Therefore, the total of each column exceeds the participants per country.

When asked which information was most essential when using a preferred cleft classification, 32.5% of the respondents indicated that anatomical and morphological characteristics were essential in the classification process (Table 2). Furthermore, almost 20% of the respondents stated that the extension and severity of the cleft were decisive for their preferred system. These variables were essential since they influence both the timing and choice of treatment, according to 26% of the respondents. The differentiation of incomplete versus complete clefts, submucous clefts and whether the alveolus was affected, were also of importance for planning suitable treatment. Other applications for classification were research, clear documentation and registration, and the evaluation of treatment results.

Table 2.

Essential Data and Manners in Which Way This Data is Essential According to Respondents.

| Essential data | N |

|---|---|

| Anatomical and morphological characteristics | 64 |

| Severity/extension of cleft | 39 |

| The data influences timing and choice of treatment and surgery | 52 |

| The data is important for research purposes | 23 |

| The data is essential for documentation/registration | 14 |

| The data is essential for evaluating treatment results | 9 |

When asked to identify limitations of their current cleft classification system, a frequent limitation of the previously mentioned classification systems was the imprecise description of the anatomical and morphological cleft characteristics (ie the severity and extension of the cleft) (Table 3). Furthermore, commonly used systems often did not include submucous clefts, Simonart's bands and nasal deformities. Another limitation cited was the fact that some clefts also failed to fit precisely into one of the categories of the used system. Due to these previously mentioned limitations, 8.6% (n = 17) of respondents would not recommend their used classification system to other cleft caregivers.

Table 3.

Recurring Limitations per Classification System. The Numbers Represent the Number of Respondents Addressing a Limitation to a Particular System.

| Anatomical description is too imprecise | SMCP not included | Lack of graphic information | Cleft does not fall neatly in categories | Too elaborate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAHSHAL | 21 | 7 | 1 | 1 | . |

| Veau | 24 | 3 | 2 | 1 | . |

| Fogh-Andersen | 2 | . | . | . | . |

| Kernahan's striped-Y | 12 | 2 | . | . | . |

| ACPA | 13 | . | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CLAP | 5 | . | 1 | . | . |

| Jensen | 1 | . | . | 1 | . |

| ICD-10 | 21 | . | 1 | . | . |

| Orphanet Codes | 2 | . | . | 1 | . |

| Luijsterburg | 1 | . | . | 1 | 1 |

Abbreviations: ACPA: American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association; CLAP: cleft lip, alveolus and palate; ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision; LAHSHAL: lip, alveolus, hard palate, soft palate, hard palate, alveolus, lip; SMCP: submucous cleft palate.

An ideal classification should have a more precise description of the severity and extension of the cleft, according to 71 respondents (36.2%). Another important feature of an ideal classification is that the classification system is easy to use, which was mentioned by 43 respondents (21.8%). Twenty-one (34.4%) countries of a total of 61 countries within our respondents have a national registry for OFCs (Supplementary data file 4). In the United States of America, registry is state-dependent. Furthermore, 19.3% did not use a local or hospital registry.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates great heterogeneity among clinicians involved in cleft care when they classify OFCs. A total of 197 clinicians from 166 centers around the globe completed the questionnaire. Respondents used eighteen different cleft registration or classification systems. Frequently cited limitations of existing systems were imprecise description of cleft extension and severity, failure to include submucous cleft palate, and difficulty in precisely classifying all clefts within the provided categories of a system.

As is mentioned in the introduction of this article, it is important to make a difference between registration and classification of clefts. Since systems that only register or register and classify are both commonly used for seemingly the same purposes, we did not distinguish between the two systems since we were only interested in the way OFC diagnoses were collected.

As respondents note, the anatomical description and the description of the extension or severity of the cleft are both the main components and greatest limitations at the same time for the majority of systems. For example, the Veau classification differentiates between the soft and hard palate but does not take into account cleft lip/alveolus and the morphological severity of palatal clefts (Veau, 1932). The ICD-10 system has been greatly improved compared to the ICD-9 system concerning the extensiveness of the anatomical varieties of clefts, but it does not allow for the documentation of morphological severity [i.e. completeness], laterality, the presence of asymmetry in the case of bilateral cleft lip/alveolus, microforms, or for clefts of the alveolus [Wang et al., 2014; Allori et al., 2016; McBride et al., 2016]. A system which solves at least one of these problems, the laterality problem, is the Kernahan striped-Y classification system [Kernahan, 1971]. Though, it cannot be used for verbal communication or description in the text format nor can it be used for computer archiving [Kernahan, 1973]. It was commonly used in the era of paper-based medical records, but its usage seems to have has diminished considerably with the advent of electronic health records [EHRs].

Kriens made some valuable suggestions about an ideal classification system. He stated that the following were pre-requisites in an ideal recording system or index for CLP: it should be: 1. Simple, so as to be accepted. 2. Concise, for accurate recording. 3. Flexible, to account for even rare presentations. 4. Exact, to facilitate research and statistics. 5. Morphological, to be able to visually assess. 6. Graphic, for clarity and to avoid ambiguity (Kriens, 1989). In an attempt to reach this ideal classification system, Kriens developed the LAHSHAL system.

LAHSHAL is a palindrome which is based upon the anatomy of the patient and proceeds from the right side towards the left side, designed to facilitate the recording during clinical examination. Each column of the acronym is filled as follows to confirm whether that part of the anatomy is involved. A capital letter is noted when an anatomic structure is completely clefted while a lowercase letter is noted when the cleft is only incomplete. Furthermore, some symbols can be used to describe other deviations. Namely, an asterisk (*) is noted when minimal clefting (eg, lesser-form cleft lip, notched alveolus, submucous cleft palate) occurs, and a dot (•/.) means that the anatomic feature is unaffected. A plus sign can be noted in the L column when a skin band (ie a Simonart's band) is present. Note in table 3 that a number of participants indicated that the LAHSHAL lacks anatomic specificity. However, not all clinicians are fully aware of the potential of this extremely elaborate classification system. Due to its extensiveness, over 12 000 combinations can be made when using the LAHSHAL system for OFCs. As such, it is extremely detailed but as a result of this it has a steep learning curve to implement it in clinical practice. Finally, the LAHSHAL system lends it well to use in electronic health records.

McBride et al., have suggested that ideally, a coding system for OFCs should be precise, logical, reproducible, accurate, and sufficiently descriptive (McBride et al., 2016). They suggest that it must be precise enough to differentiate between subphenotypes; it should be user-friendly and accurate to be used globally between various health care professionals and epidemiologists with little need for training. It should also be sufficiently descriptive to differentiate laterality and completeness to facilitate the future of genetic and etiological research while being easily interpreted by users from different research and clinical backgrounds. In addition to these requirements, the coding system must remain relevant to the current globally recognized system of recording disease, the ICD-10 system. McBride et al., illustrated how LAHSHAL codes could be converted to ICD-10, and potentially be automated using an algorithm (McBride et al., 2016). Therefore, the LAHSHAL classification (or a variant) and the Luijsterburg et al., classification, as described in this manuscript, are potentially useful tools and could be a complement to the ICD-10 system.

Several limitations of this study have to be addressed. A total of 197 respondents among 2140 invitations completed our survey. Some healthcare professionals received multiple invitations when they attended more than one congress. It was not clearly mentioned whether a respondent had to respond individually or on behalf of their entire cleft team. Consequently, the response rate is unknown. Furthermore, participation bias is inseparable with cross-sectional survey studies, which hinders making global recommendations. This survey demonstrated that LAHSHAL and Luijsterburg et al., were most used. Since the usage of Luijsterburg et al., is limited to Europe, we recommend LAHSHAL as optimal classification system. Another limitation of the survey is that no distinction was made between state, regional registries and national registries. For example, in the USA, some states have state registries although a national registry does not exist. Therefore, we excluded the USA from this specific question. Moreover, this questionnaire involved only clinicians involved in the care of patients with OFCs. Policy makers, hospital staff members involved in the financial reimbursement and insurance companies were not involved in the survey despite their role in the cleft care process.

Conclusions

Great variety of classification systems currently used exists among clinicians when confronted with patients with OFCs. Because future advances in our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of OFCs will require us to compare precisely phenotyped cohorts of patients with clefts, further research and involvement among geneticists and embryologists is needed to provide optimal comprehension of classifying clefts amongst all craniofacial specialists. Classifying clefts with a universally implemented classification system is essential for improved communication between craniofacial specialists and comparison of scientific data globally. According to the results of this study, LAHSHAL could be the most suited universal classification system, due to its extensiveness, relatively high implementation rate and convenient usage to complement the ICD-10 system. Potentially, this could make up for the deficiencies of the ICD-10 codes that do not indicate laterality, completeness, and clefts of the alveolus. For more international acceptance, standardization and better communication globally it is prudent to demonstrate to users the merits of the LAHSHAL classification system.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cpc-10.1177_10556656211057368 for Classification Systems of Cleft Lip, Alveolus and Palate: Results of an International Survey by Ruben Houkes, Johannes Smit and Peter Mossey, Peter Don Griot, Martin Persson, Amanda Neville, Edwin Ongkosuwito, Tom Sitzman, Corstiaan Breugem in The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-cpc-10.1177_10556656211057368 for Classification Systems of Cleft Lip, Alveolus and Palate: Results of an International Survey by Ruben Houkes, Johannes Smit and Peter Mossey, Peter Don Griot, Martin Persson, Amanda Neville, Edwin Ongkosuwito, Tom Sitzman, Corstiaan Breugem in The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-cpc-10.1177_10556656211057368 for Classification Systems of Cleft Lip, Alveolus and Palate: Results of an International Survey by Ruben Houkes, Johannes Smit and Peter Mossey, Peter Don Griot, Martin Persson, Amanda Neville, Edwin Ongkosuwito, Tom Sitzman, Corstiaan Breugem in The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-cpc-10.1177_10556656211057368 for Classification Systems of Cleft Lip, Alveolus and Palate: Results of an International Survey by Ruben Houkes, Johannes Smit and Peter Mossey, Peter Don Griot, Martin Persson, Amanda Neville, Edwin Ongkosuwito, Tom Sitzman, Corstiaan Breugem in The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal

Footnotes

Authors contributions: All authors were involved in the following aspects: (1) Made a substantial contribution to the concept or design of the work; or acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data. (2) Drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content. (3) Approved the version to be published. (4) Participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Institutional review board approval was obtained by the ‘Medisch Ethische Toetsingscomissie AMC’ of the Amsterdam University Medical Center/University of Amsterdam (W21_015#21.017).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Ruben Houkes https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0390-3822

Johannes Smit https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1199-2335

Tom Sitzman https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2173-923X

Corstiaan Breugem https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3587-7489

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Allori AC, Cragan JD, Cassell CH, Marcus JR. ICD-10-based expanded code set for use in cleft lip/palate research and surveillance. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2016;106(11):905-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allori AC, Mulliken JB, Meara JG, Shusterman S, Marcus JR. Classification of cleft Lip/palate: then and Now. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2017;54(2):175-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzolari E, Pierini A, Astolfi G, Bianchi F, Neville AJ, Rivieri F. Associated anomalies in multi-malformed infants with cleft lip and palate: an epidemiologic study of nearly 6 million births in 23 EUROCAT registries. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(6):528-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRANE: The Cleft Registry and Audit NEtwork. Available at: https://www.crane-database.org.uk/. Accessed July 5, 2021.

- Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, Murray JC. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(3):167-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogh-Andersen P. Epidemiology and etiology of clefts. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1971;7(7):50-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes AC, Neves LT, Gomide MR. Enamel defects in maxillary central incisors of infants with unilateral cleft lip. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2009;46(4):420-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosen D, Chevrier C, Skytthe A, Bille C, Mølsted K, Sivertsen A, Murray JC, Christensen K. A cohort study of recurrence patterns among more than 54,000 relatives of oral cleft cases in Denmark: support for the multifactorial threshold model of inheritance. J Med Genet. 2010;47(3):162-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkins CS, Berlin A, Harding RL, Longacre JJ, Snodgrasse RM. A classification of cleft lip and cleft palate. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1962;29:31-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernahan DA. The striped Y-a symbolic classification for cleft lip and palate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;47:469-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernahan DA. On cleft lip and palate classification. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;51(5):578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriens O. LAHSHAL: A Concise Documentation System for Cleft Lip, Alveolus and Palate Diagnosis in What is a Cleft Lip and Palate?: A Multidisciplinary Update. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1989: 30-34. [Google Scholar]

- Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, Meyer RE, Correa A, Alverson CJ, Lupo PJ, Riehle-Colarusso T, Cho SJ, Aggarwal D, et al. National population-based estimates for major birth defects, 2010–2014. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111(18):1420-1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride WA, McIntyre GT, Carroll K, Mossey PA. Subphenotyping and classification of orofacial clefts: need for orofacial cleft subphenotyping calls for revised classification. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2016;53(5):539-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossey PA, Modell B. Epidemiology of oral clefts 2012: an international perspective. Front Oral Biol. 2012;16:1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivertsen A, Wilcox AJ, Skjaerven R, Vindenes HA, Abyholm F, Harville E, Lie RT. Familial risk of oral clefts by morphological type and severity: population based cohort study of first degree relatives. Br Med J. 2008;336(7641):432-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallridge J, Hall AJ, Chorbachi R, Parfect V, Persson M, Ireland AJ, Wills AK, Ness AR, Sandy JR. Functional outcomes in the cleft care UK study – part 3: oral health and audiology. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2015;18(Suppl 2):25-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman KK, Hakelius M, Höijer J, Ramklint M, Ekselius L, Nowinski D, Papadopoulos FC. Increased risk for neurodevelopmental disorders in children with orofacial clefts. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(11):876-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truelsen T, Krarup LH, Iversen HK, Mensah GA, Feigin VL, Sposato LA, Naghavi M. Causes of death data in the global burden of disease estimates for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45(3):152-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veau V. Division palatine: Anatomie – chirurgie phonétique. Paris: Masson et Cie; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Wang KH, Heike CL, Clarkson MD, Mejino JLV, Brinkley JF, Tse RW, Birgfeld CB, Fitzsimons DA, Cox TC. Evaluation and integration of disparate classification systems for clefts of the lip. Front Physiol. 2014;5:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waylen A, Ness AR, Wills AK, Persson M, Rumsey N, Sandy JR. Cleft care UK study. Part 5: child psychosocial outcomes and satisfaction with cleft services. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2015;18(Suppl 2):47-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehby GL, Cassell CH. The impact of orofacial clefts on quality of life and healthcare use and costs. Oral Dis. 2010;16(1):3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Estimates 2016: Disease burden by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GHE2016_DALY_Global_2000_2016_.xls?ua=1. Accessed July 5, 2021b.

- World Health Organization. Global registry and database on craniofacial anomalies. Available at: https://www.who.int/genomics/anomalies/en/CFA-RegistryMeeting-2001.pdf/. Accessed July 5, 2021a.

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). Available at: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases/. Accessed July 5, 2021c.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cpc-10.1177_10556656211057368 for Classification Systems of Cleft Lip, Alveolus and Palate: Results of an International Survey by Ruben Houkes, Johannes Smit and Peter Mossey, Peter Don Griot, Martin Persson, Amanda Neville, Edwin Ongkosuwito, Tom Sitzman, Corstiaan Breugem in The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-cpc-10.1177_10556656211057368 for Classification Systems of Cleft Lip, Alveolus and Palate: Results of an International Survey by Ruben Houkes, Johannes Smit and Peter Mossey, Peter Don Griot, Martin Persson, Amanda Neville, Edwin Ongkosuwito, Tom Sitzman, Corstiaan Breugem in The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-cpc-10.1177_10556656211057368 for Classification Systems of Cleft Lip, Alveolus and Palate: Results of an International Survey by Ruben Houkes, Johannes Smit and Peter Mossey, Peter Don Griot, Martin Persson, Amanda Neville, Edwin Ongkosuwito, Tom Sitzman, Corstiaan Breugem in The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-cpc-10.1177_10556656211057368 for Classification Systems of Cleft Lip, Alveolus and Palate: Results of an International Survey by Ruben Houkes, Johannes Smit and Peter Mossey, Peter Don Griot, Martin Persson, Amanda Neville, Edwin Ongkosuwito, Tom Sitzman, Corstiaan Breugem in The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal