Abstract

Introduction

Hereditary cholestasis is a heterogeneous group of liver diseases that mostly show autosomal recessive inheritance. The phenotype of cholestasis is highly variable. Molecular genetic testing offers an useful approach to differentiate different types of cholestasis because some symptoms and findings overlap. Biallelic variants in USP53 have recently been reported in cholestasis phenotype.

Methods

In this study, we aimed to characterize clinical findings and biological insights on a novel USP53 splice variant causing cholestasis phenotype and provided a review of the literature. We performed whole-exome sequencing and then confirmed it with Sanger sequencing. In addition, as a result of in silico analyses and cDNA analysis, we showed that the USP53 protein in our patient was shortened.

Results

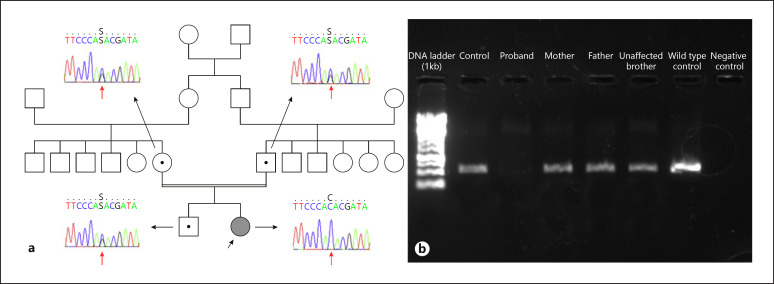

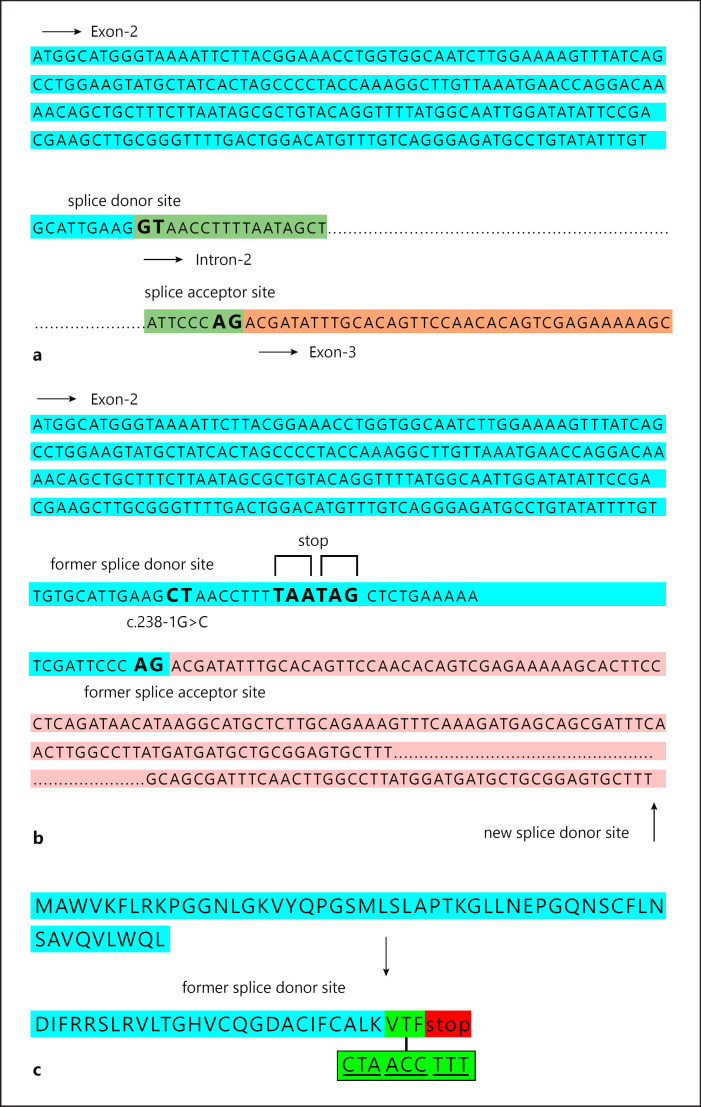

We report a novel splice variant (NM_019050.2:c.238–1G>C) in the USP53 gene via whole-exome sequencing in a patient with cholestasis phenotype. This variant was confirmed by Sanger sequencing and was a result of family segregation analysis; it was found to be in a heterozygous state in the parents and the other healthy elder brother of our patient. According to in silico analyses, the change in the splice region resulted in an increase in the length of exon 2, whereas the stop codon after the additional 3 amino acids (VTF) caused the protein to terminate prematurely. Thus, the mature USP53 protein, consisting of 1,073 amino acids, has been reduced to a small protein of 82 amino acids.

Conclusion

We propose a model for the tertiary structure of USP53 for the first time, and together with all these data, we support the association of biallelic variants of the USP53 gene with cholestasis phenotype. We also present a comparison of previously reported patients with USP53-associated cholestasis phenotype to contribute to the literature.

Keywords: USP53, Cholestasis, Homology modeling, Whole-exome sequencing, Genotype-phenotype correlation

Introduction

Cholestasis is a condition characterized by disruption of hepatobiliary production and biliary excretion resulting from the entry of bile compounds into the systemic circulation. Hereditary cholestasis is a heterogeneous group of liver diseases that mostly show autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Clinical findings include intrahepatic cholestasis, pruritus, and jaundice. The severity of cholestasis is highly variable. It may present with a variable phenotype ranging from progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) that starts in early infancy and progresses to end-stage liver disease, to benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC), which is a milder, intermittent, mostly nonprogressive form of cholestasis [Sticova et al., 2018]. Molecular genetic testing offers a useful approach to differentiate different types of cholestasis due to overlapping symptoms and findings. Pathogenic variants in the ATP8B1, ABCB11, ABCB4, TJP2, NR1H4, and MYO5B genes have been identified in the etiology of a wide spectrum from PFIC to BRIC affecting children and adults [Wang et al., 2016; Nicastro et al., 2019; Amirneni et al., 2020].

Among the recently identified new loci associated with cholestasis, the USP53 gene is located on chromosome 14q24.3 and encodes a non-protease homologue of the ubiquitin-specific peptidase which is predicted to play a role in the regulation of protein degradation [Quesada et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2020b]. Studies have shown that the USP53 protein is expressed in the liver, brain, kidney, and inner ear [Kazmierczak et al., 2015; Maddirevula et al., 2019]. USP53 is a tight junction protein that interacts with other tight junction proteins 1 and 2 (TJP1 and TJP2). TJPs are cytoplasmic proteins that bind intrinsic membrane tight junction proteins to the cytoskeleton [Roehlen et al., 2020].

In this study, we report a novel homozygous splice variant in the USP53 gene in a patient with PFIC phenotype who responded dramatically to rifampicin. We present the clinical, histological, and ultrastructural features of our patient and a model for the USP53 tertiary structure for the first time, together with previously reported USP53-related cholestasis patients.

Material and Methods

Detailed physical examination, biochemical parameters, and abdominal ultrasound of the patient were performed for the etiology of cholestasis. Liver biopsy was performed during follow-up. Sequential genetic studies were conducted. All studies were performed as part of routine clinical care.

Liver Biopsy

Histopathological examination was performed by preparing 4-micron sections from the liver biopsy material and applying hematoxylin-eosin, PAS (Periodic Acid–Schiff), PAS Diastase, Masson trichrome, Reticulin, and Iron stains.

Whole-Exome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood of the patient after the completion of a consent form. DNA was isolated from sterile 2-mL EDTA peripheral blood samples using PureLinkTM Genomic DNA Mini Kit. Then, the measurement of the quality of the DNA obtained was made with “Qubit” device. Qualified DNA samples were enzymatically randomly digested after sample quality control (QC). The ends of these DNA fragments collected with magnetic beads were repaired (end repair) and adenine was added to the 3′ ends. In the next step, adapters and barcodes were added to the fragments based on ligation and the first PCR step was started.

In order to get rid of the unbound fragments, a purification was made after the first PCR step had been done. For enrichment, hybridization was performed with a capture kit with a 36-Mb target region. Then, unhybridized fragments were washed and the second PCR step was started. The second PCR stage was creating DNA Nanoball (DNB) on the same chain by turning the DNA into a round chain with a stage thus minimizing PCR errors. A splint oligo was also used to make the DNA circular. Each created DNB was placed in spots on the flow cell on the DNBSEQ G-400 sequencing platform. The sequencing process occurred on the flow cell, and the reaction solution containing modified dNTPs marked with different dyes was loaded into the flow cell. After the sequencing, firstly, raw sequencing data were inspected using FASTQC to perform quality control checks and then was processed with fastp v0.20.1 to remove adaptors and low-quality bases. Resulting high-quality “.fastq” files were aligned to a reference human genome (hg19, GRCh37) with bwa-mem v0.7.17 algorithm with default parameters. The obtained SAM files were converted to sorted and indexed BAM files with Sambamba v 0.8.0. Read duplicates in alignment files were marked using Picard v2.23.0 using MarkDuplicates option. Then, realignment around known indels and base quality score recalibration was performed using GATK toolkit v.3.7.0. By using GATK BaseRecalibrator, base quality recalibration was performed with known Sites files (dbSNP151, Mills and 1000 genome indels, and known indels) from the GATK hg19 resource bundle. Single nucleotide variants and small insertions and deletions were called by GATK haplotype caller version 3.7. Variant annotation was performed with ANNOVAR with the following public datasets: 1000 Genomes Project, Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC v.0.3.1), the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD, v3.1), CADD v3.0, ClinVar, UCSC, and dbNSFP4. Some variants (SNP, indels) were reviewed manually using the Integrative Genomics (IGV v2.10, Broad Institute). Coverage of each variant was calculated using BEDTools v 2.30.0 with the “-d” parameter to calculate the per base depth and then the percentage of bases with at least 20, 30, 50, and 100× coverage were calculated.

Sanger Sequencing

Specific primers were designed for the segregation studies within the family for the UPS53 variant of interest. After completion of the consent forms from the patient, parents, and healthy elder brother for segregation studies, genomic DNA was isolated as described above. Sanger sequencing was performed on the Applied Biosystems® Sanger Sequencing 3500 Series Genetic Analyzer using standard PCR and sequencing protocols.

Reverse Transcription PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated using an available kit (RiboExTM Total RNA isolation kit) from peripheral blood samples of the index patient, unaffected sibling, and parents using the manufacturer's guidelines. FastGene® Scriptase Basic kit and random hexamers were used for cDNA synthesis. PCR reactions were performed using custom-designed primers (F: TCTTACGGAAACCTGGTGGC and R: ACATATTTTCAAAGCACTCCGCA), and PCR products were loaded into 1% agarose gel.

Sequence Data and Splicing Analyses

USP53 (HGNC ID:29255) sequence information of Homo sapiens was obtained from the NCBI database (NM_019050.2). NM_019050.2:c.238–1G>C mutation data was generated with the MegaX bioinformatics tool [Kumar et al., 2018]. Splicing analyses were performed with MutationForecaster® [Mucaki et al., 2013; Caminsky et al., 2014].

Homology Modeling of Wild-Type and Mutant USP53

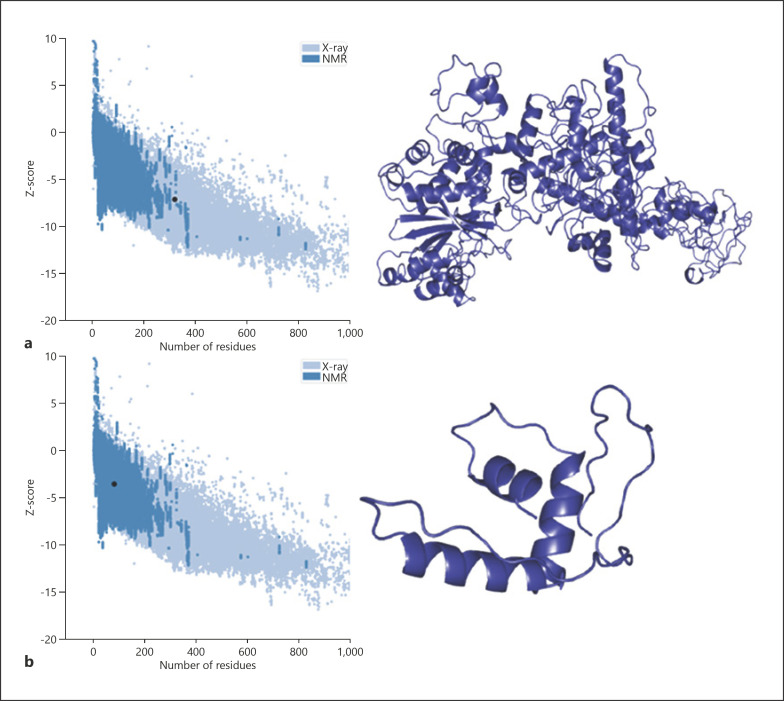

Human USP53 protein sequence information was obtained from the Uniprot database (Q70EK8). Three-dimensional models of wild-type and mutant USP53 proteins were generated by the method of homology modeling using ProMod3 and trRosetta [Waterhouse et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2020]. 3MHS (RCSB protein data bank code) was selected as template. ProSA was used for structural validation and model of wild-type and mutant USP53 proteins [Wiederstein and Sippl, 2007]. Secondary structure components (random coils, beta strands, alpha helices) of the USP53 protein were defined by using PSIPRED [Buchan et al., 2013]. Superimpose and conformational analyses of wild-type and mutant proteins were performed with PyMOL (ver2.4.1).

Results

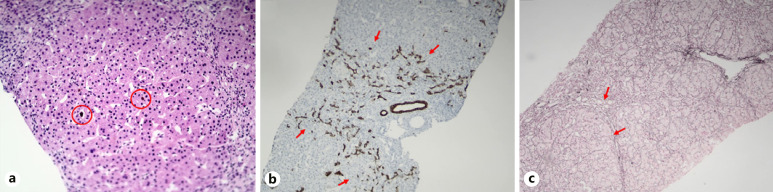

A 21-month-old Syrian girl was presented to our pediatric emergency department at 4 months of life with the complaints of sudden onset jaundice and pruritus. She was the second child of consanguineous parents (first cousin marriage) with a healthy elder brother. The patient was born at 38th gestational week with a birth weight of 2,500 g and unknown birth height and head circumference. Routine newborn metabolic and hearing screenings were unremarkable. She had no history of neonatal jaundice. The physical examination at hospital admission revealed jaundice without organomegaly and there was no family history of liver disease. Biochemical tests showed normal renal function and electrolytes. She was anemic (hemoglobin 9.4 g/dL) and had cholestasis (total bilirubin 5.09 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 4.46 mg/dL) with a normal γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) level (32 U/L). Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 53 U/L (upper limit normal [ULN]: 54); alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 29 U/L (ULN: 56); alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 622 U/L (ULN: 469), and albumin 3.2 g/dL; INR: 1.05; total cholesterol level was 161 mg/dL. The viral serology for hepatotropic viruses was negative, and serum alpha-1 antitrypsin and metabolic screening tests were all normal. The patient was treated with oral ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) (20 mg/kg/day), cetirizine, and fat-soluble vitamins (vitamin K, 1 mg/kg, 3 times per day; vitamins A and D, 1,500 U per day; vitamin E 10 mg/kg/day). At 2-month follow-up visit, liver function tests were gradually elevated. Jaundice and pruritus were not alleviated and moreover, hepatosplenomegaly was identified at a 5-month follow-up. Liver biopsy was performed at 9 months of age. Histopathological examination showed canalicular cholestasis, sparse giant cell formation, periportal ductular proliferation, porto-portal, porto-central, and centrilobular fibrosis, complete and incomplete nodule formation, and mild portal inflammation (Fig. 1). Serum bile acid levels (123 µmol/L, ULN: 41) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP, 341 ng/mL, ULN: 27) levels were elevated.

Fig. 1.

Histopathological findings in our patient. a H&E staining, ×20, bile plugs and canalicular cholestasis. b CK19 (cytokeratin-19) staining, ×10, periportal ductular proliferation. c Reticulin staining, ×10, bridging fibrosis, incomplete nodule formation.

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) type 1 and 2 were considered in the differential diagnosis because of having progressive cholestasis with normal GGT level, resistant pruritus, and rapid progression to cirrhosis in infancy. Since there was a strong suspicion of PFIC-2 due to the high level of serum AFP and not having extrahepatic manifestations, ABCB11 sequencing was performed, but no disease-causing variant was detected. Then, sequence analysis of the ATP8B1 gene for PFIC-1 was performed and no disease-causing variant was also found. In order to identify etiology of the disease, whole-exome sequencing (WES) from the index patient was performed. We did not identify any cholestasis-related disease-causing variant in OMIM and HPO. However, a c.238–1G>C homozygous splice variant in the USP53 gene (NM_019050.2) was singled out. Sanger sequencing, carried out for segregation and confirmation purposes, revealed that the patient is homozygous and both parents and the healthy elder brother are heterozygous as expected with a recessive disease trait (Fig. 2a). cDNA study amplifying exon 1–4 did not reveal any product in the patient which confirms the truncation of exon 3 in our subject (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

a Pedigree of the family and Sanger sequencing images of the proband, parents, and the healthy brother. b PCR amplification of cDNA targeting exon 1–4. While there is no band in the proband, a clear band is visible in the control samples, parents, and unaffected sibling.

The variant has not been reported in the relevant scientific literature, ClinVar or in the gnomAD exomes and genomes (available at https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org). Computational verdict-based databases such as BayesDel_addAF, DANN, EIGEN, FATHMM-MKL, MutationTaster, and scSNV-Splicing evaluated this variant as damaging. Within all these data and according to the ACMG guideline [Richards et al., 2015], this variant was considered as pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP3). Mutation prediction scores and publicly available database frequency of the variant are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Predictions of pathogenicity of USP53 c.238–1G>C

| Transcript ID | NM_019050.2 |

|

| |

| dbSNP | Novel |

|

| |

| Variant | c.238–1G>C |

|

| |

| Variant location | Intron 5 |

|

| |

| Variant type | Splicing |

|

| |

| MutationTaster | Disease-causing, protein features (might be) affected by splice site changes |

|

| |

| varSEAK | Class 5 (exon skipping, loss-of-function for authentic splice site) |

|

| |

| dbscSNV ADA score | 0.9999 |

|

| |

| gnomAD (exomes and genomes) | Not detected |

|

| |

| ClinVar | Not reported |

|

| |

| dbNSFP EIGEN | Pathogenic |

|

| |

| DANN score | 0.9952 |

|

| |

| GERP score | NR: 6.01; RS: 6.01 |

|

| |

| ACMG classification | Pathogenic |

|

| |

| ACMG pathogenicity criteria | PVS1, PM2, PP3 |

gnomAD, Genome Aggregation Database; ACMG, The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; dbscSNV, a comprehensive database of all potential human SNVs within splicing consensus regions and their functional annotations; ClinVar, clinically relevant variation; dbNSFP, database developed for functional prediction and annotation of all potential non-synonymous single-nucleotide variants; DANN, a deep learning approach for annotating the pathogenicity of genetic variants; GERP, Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling.

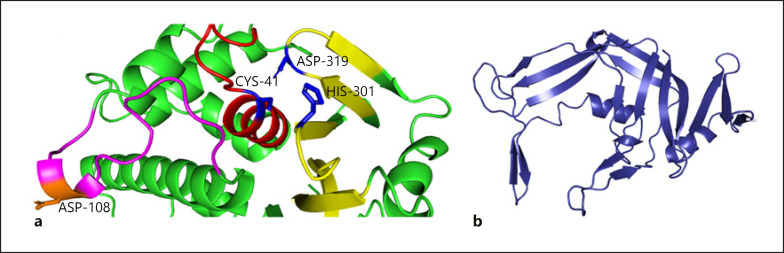

A positional change in splicing after c.238–1G>C variation detected in intron 2 splice donor site of USP53 is given in Figure 3a. This variant moved the splice donor site in intron 2 to the splice donor site in intron 3 (Fig. 3b). The change in the splice region resulted in an increase in the length of exon 2, whereas the stop codon after the additional 3 amino acids (VTF) caused the protein to terminate prematurely (Fig. 3c). Thus, the mature USP53 protein, consisting of 1,073 amino acids, has been reduced to a small protein of 82 amino acids. The tertiary structure of USP53 is unknown. In this study, we propose a model for the USP53 tertiary structure for the first time. The protein model of wild-type USP53 had a Z-score of −7.05. The wild-type model was within the limits of X-ray quality (Fig. 4a). The Z-score of the homology model of the 82 amino acid protein that emerged after the splicing variant that we found was −3.59. The mutant model was within the limits of NMR quality (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 3.

a Organizational representation of the splicing site before NM_019050.2:c.238–1G>C mutation. Blue color: exon 2 sequence, green color: intron 2 sequence, pink color: exon 3 sequence. b Organizational representation of the splicing site after NM_019050.2:c.238–1G>C variant. Blue color: exon 2, pink color: exon 3. c Representation of the amino acid sequence of the early-terminating USP53 protein after mutation. Blue color: region of exon 2 before mutation, green color: representation of 3 amino acids added after mutation (pre-early termination).

Fig. 4.

Tertiary structure model of wild-type and mutant USP53. a Quality score plot of wild-type USP53 homology model and homology model of wild-type USP53. b Quality score plot of mutant USP53 homology model and homology model of mutant USP53.

Discussion

Considering the genetic etiology of pediatric cholestasis in the literature, the diagnostic yield of genetic tests varies between 25 and 50% [Alhebbi et al., 2021]. This rate has been increasing with the discovery of novel genes associated with cholestasis in recent years, after the prevalence of genetic testing has increased. Next-generation sequencing technologies are a promising tool for discovering new genes related to pediatric cholestasis. For example, in a study on pediatric cholestatic liver disease in 2019, it was suggested that 5 novel loci and candidate genes were identified in the etiology of the disease. These genes are KIF12, PPM1F, USP53, LSR, and WDR83OS [Maddirevula et al., 2019].

Biallelic variants in USP53 have recently been reported in cholestasis phenotype. Up to now, a total of 31 cases from 24 families have been reported in 8 articles in the literature showing that the USP53 gene is associated with cholestasis and/or some additional phenotypes [Maddirevula et al., 2019; Cheema et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020b; Alhebbi et al., 2021; Bull et al., 2021; Porta et al., 2021; Shatokhina et al., 2021; Vij and Sankaranarayanan, 2021]. Despite the identification of 24 families in the literature, there is no OMIM entry for a USP53-related phenotype. Detailed clinical, laboratory, and genetic findings of all cases reported in the literature including ours (total 32 cases) are summarized in Tables 2, 3, 4. A total of 19 different variants have been reported in these patients. Of these variants, 6 were frameshift, 5 were nonsense, 4 were missense, 2 were indel, 1 was splice, and 1 was a small deletion. Also, 1 family with 3 affected individuals had large copy number variation (CNV) involving exon 1 of USP53. When the patients were clinically evaluated, 3 of the reported USP53 cases had additional hearing loss. In mice, studies have shown that USP53 co-locates with TJP2 and contributes to tight junction structures, at least in the ear [Kazmierczak et al., 2015]. Pathogenic variants detected in the TJP2 gene have been shown to be associated with hypercholanemia, normal or low GGT intrahepatic cholestasis, hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as deafness [Carlton et al., 2003; Kazmierczak et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2020a]. However, we recommend that cases with variants in USP53 should be monitored for hearing loss and that aminoglycoside antibiotics should be avoided to prevent potential further damage. Alhebbi et al. [2021] reported an 18-month-old patient with a homozygous frameshift USP53 variant (c.951delT [p.Phe317fs]), in whom speech and gross motor delay were accompanying. In the same article, 4 siblings from another family had the same variant but these patients had no speech or developmental delay. Although no other genetic variant in another locus that may explain the mental and motor delay in the patient was reported, the absence of developmental delay in all other cases in the literature suggests a possible secondary genetic etiology, i.e., multilocus pathogenic variation in that patient [Pehlivan et al., 2019; Mitani et al., 2021]. However, as the number of cases identified in the USP53 gene increases, we will have more accurate genotype-phenotype correlations.

Table 2.

Summary of clinical, histological, and genetic findings of all reported USP53 cases in the literature

| Porta et al. [2021] |

Zhang et al. [2020b] |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our patient | P1 | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | |

| Gender | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Male |

|

| |||||||||

| Age | 21 months | 4 months | 12 months 21 days | 4 months 15 days | 8 months 25 days | 9 months 25 days | 4 months 18 days | 6 months | 8 months |

|

| |||||||||

| Ethnicity | Syrian | Brazilian | Chinese | Chinese | Chinese | Chinese | Chinese | Chinese | Chinese |

|

| |||||||||

| Consanguinity | Yes | No | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| |||||||||

| Age of onset | 4 months | 10 days | 3 days | 2 days | 6 months | 5 months | 1 month | 5 months | 7 months |

|

| |||||||||

| Initial symptom | Jaundice, pruritus | Cholestasis, jaundice | Jaundice | Jaundice | Jaundice | Jaundice | Jaundice | Jaundice | Jaundice |

|

| |||||||||

| Other symptoms | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| |||||||||

| Laboratory AST, IU/L | First/Last 53/52 | 130 (N:30) | 215 | 71 | 121 | 84 | 51 | 41 | 225 |

|

| |||||||||

| ALT, IU/L | 29/24 | 69 (N:35) | 184 | 70 | 103 | 32 | 28 | 26 | 18 |

|

| |||||||||

| ALP, IU/L | 622/396 | 330 | 548 | 636 | 543 | 342 | 283 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| GGT, IU/L | 32/15 | 37 (N:19) | 23 | 72 | 34 | 39 | 40 | 27 | 22 |

|

| |||||||||

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 5.09/0.93 | 8.98 | 23 | 90 | 212 | 308 | 275 | 85 | 153 |

|

| |||||||||

| Direct bilirubin, mg/dL | 4.46/0.86 | 6.69 | 19 | 65 | 159 | 167 | 216 | 72 | 137 |

|

| |||||||||

| Serum bile acid levels, µmol/L | 123 | 216 (N:10) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Abdomen USG | Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly | Hepatomegaly and cholelithiasis | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| |||||||||

| Liver biopsy | Canalicular cholestasis, sparse giant cell formation, periportal ductular proliferation, porto-portal, porto-central and centrilobular fibrosis, complete and incomplete nodule formation and mild portal inflammation | Marked cholestasis, giant cell transformation, portal septal fibrosis, periportal ductular proliferation | NA | NA | Lobular disarray and hepatocellular cholestasis and rosetting, with canalicular cholestasis, giant-cell change of hepatocytes | Lobulardisarray and hepatocellular cholestasis and rosetting, with canalicular cholestasis | NA | Lobular disarray and hepatocellular cholestasis and rosetting, with canalicular cholestasis, giant-cell change of hepatocytes, cirrhosis | Lobulardisarray and hepatocellular cholestasis and rosetting, with canalicular cholestasis, giant-cell change of hepatocytes, portal-tract fibrosis and mixed acute and chronic inflammation |

|

| |||||||||

| Hearing | Normal | NA | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Hearing loss | NA |

|

| |||||||||

| Treatment | UDCA and rifampicin | UDCA and rifampicin cholecystectomy operation | UDCA and Cholestyramine | UDCA | UDCA | UDCA and Cholestyramine | UDCA | UDCA and Cholestyramine | UDCA and Cholestyramine |

|

| |||||||||

| Situation of after the treatment | At last follow-up (21 months) no jaundice, mild pruritus, and normal transaminases and no organomegaly | At last follow-up (18 months), no jaundice, moderate pruritus, and normal transaminases | Mildly elevated transaminases. Alive with native liver at 2 years | Normal transaminases. Alive with native liver at 3 years 6 months | Normal transaminases. Alive with native liver at 5 years | Mildly elevated transaminases. Alive with native liver at 17 months | NA | Normal transaminases. Alive with native liver at 1 year 3 months; cochlear implant at 1 year 3 months | Mildly elevated transaminases. Alive with native liver at 1 year 1 month |

|

| |||||||||

| USP53 (Transcript) | ΝM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | ΝM_019050.2 | ΝM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 |

|

| |||||||||

| Nucleotide change | c.238–1G>C | c.1687_1688delinsC | c.1012C>T | c.169C>T/c.831_832insAG | c.569+2T>C/c.878G>T | c.581delA/c.1012C>T | c.1012C>T/c.1426C>T | c.395A>G/c.l558C>T | c.297G>Tc.1012C>T |

|

| |||||||||

| Protein change | p:? | p.Ser563Profs*25 | p.Arg338Ter | p.Arg57Ter/p.Val279GlufsTer16 | p:?/p.Gly293Val | p.Arg195GlufsTer38/p.Arg338Ter | p.Arg338Ter/p.Arg476Ter | p.His132Arg/p.Arg520Ter | p.Arg99Ser/p.Arg338Ter |

|

| |||||||||

| Variant type | Splice | Indel | Nonsense | Nonsense/indel | Splice/missense | Frameshift/nonsense | Nonsense | Missense/nonsense | Missense/nonsense |

|

| |||||||||

| ACMG classification | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic/pathogenic | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic | Pathogenic/pathogenic | Pathogenic/pathogenic | Likely pathogenic/pathogenic | Likely pathogenic/pathogenic |

Table 3.

Summary of clinical, histological, and genetic findings of all reported USP53 cases in the literature

| Bull et al. [2021] |

Alhebbi et al. [2021] |

Shatokhina et al. [2021] |

Vij and Sankaranarayanan [2021] |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P1 | P2 | P1 | P1 | |

| Gender | Female | Male | Female | Female | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female | Male | Male |

|

| |||||||||||

| Age | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2y | 7 mo |

|

| |||||||||||

| Ethnicity | Turkish | Turkish | Turkish | Middle eastern | Middle eastern | North African | South Asian | Saudi | Saudi | Dagestan | India |

|

| |||||||||||

| Consanguinity | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Age of onset | 3 months | 2 months | 5 months | 7 years | Neonatal | 15 years | 4 years | 4 months | 15 months | Neonatal | 6 months |

|

| |||||||||||

| Initial symptom | Cholestasis | Cholestasis | Cholestasis | Cholestasis | Cholestasis | Cholestasis | Cholestasis | Coagulopathy, normal GGT cholestasis | Cholangiopathy, normal GGT cholestasis | Prolonged jaundice | Jaundice and pruritus |

|

| |||||||||||

| Other symptoms | NA | Heart failure | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Itching | Intractable itching | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Laboratory AST, IU/L | 163 | 222 | 103 | NA | 38 | 74 | 46 | 37 | 82 | 133.5 | 48 |

|

| |||||||||||

| ALT, IU/L | 169 | 61 | NA | 22 | 78 | 84 | 30 | 97 | 185 | 33 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| ALP, IU/L | 553 | 6,316 | 1,596 | 1,471 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| GGT, IU/L | 41 | 62 | 46 | NA “normal” | 35 | 25 | 34 | 23 | 35 | 54 | 20.6 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 6.6 | 5.2 | 18.4 | NA | 3.9 | 3.4 | 6.3 | 172 (µmol/L) | 159 | 253 (mmol/L) | 10.76 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Direct bilirubin, mg/dL | 6.1 | 3.8 | 14.6 | NA | 1.9 | 2.8 | 158 (µmol/L) | 132 | 124.5 | 7.62 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Serum bile acid levels, µmol/L | 219 | ND | ND | NA | 37 | ND | 15 | 115 | NA | NA | 225 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Abdomen USG | Splenomegaly | NA | Splenomegaly | NA | Splenomegaly | Splenomegaly | NA | NA | NA | Hepatosplenomegaly | NA |

|

| |||||||||||

| Liver biopsy | Porto-septal fibrosis, biliary rosette formation | Porto-septal fibrosis hepatocyte giant cell change canalicular and hepatocellular cholestasis and mild lobular activity | NA | NA | Porto-portal bridging fibrosis | Porto-septal fibrosis | NA | NA | Ductular proliferation and inflammation suggestive of biliary atresia | NA | Lobular bilirubinostasis with fibrosis |

|

| |||||||||||

| Hearing | Normal | Normal | Normal | NA | NA | Not done | NA | None | Deafness | Normal | Normal |

|

| |||||||||||

| Treatment | None | None | Rifampicin, UDCA. Relapses off rifampicin | UDCA | Rifampicin | None | Rifampicin, UDCA and cholestyramine | NA | NA | UDCA | Vitamin supp, cholestyramine |

|

| |||||||||||

| Situation of after the treatment | 11 years, normal transaminases and bile acids | 8 years, normal transaminases and bile acids | 2 years, normal transaminases | 10 years, normal transaminases | 13 years, normal transaminases, mildly elevated bile acids | 18 years, normal transaminases | 21 years, as above | Alive with native liver (2 years) | Alive, post-liver transplant (24 years) | 3 years, normal transaminases | Alive |

|

| |||||||||||

| USP53 (Transcript) | ΝM_01050.2 | NM_019,050.2 | ΝM_019050.2 | ΝM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Nucleotide change | Deletion of 1st coding exon | Deletion of 1st coding exon | Deletion of 1st coding exon | c.145–11_167del | c.145–11_167del | c.725C>T | c.510delA | c.951delT | c.951delT | c.1017_1057del | c.822+1delG |

|

| |||||||||||

| Protein change | p:? | p:? | p:? | p:? | p:? | p.Pro242Leu | p.Ser171ArgfsTer62 | p.Phe317fs | p.Phe317fs | p.Cys339Trpfs | p:? |

|

| |||||||||||

| Variant type | Gross del | Gross del | Gross del | Gross del | Gross del | Missense | Frameshift | Frameshift | Frameshift | Frameshift | Splice |

|

| |||||||||||

| ACMG classification | ? | ? | ? | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | VUS | Likely pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic |

Table 4.

Summary of clinical, histological, and genetic findings of all reported USP53 cases in the literature

| Alhebbi et al. [2021] |

Cheema et al. [2020] |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | |

| Gender | Female | Male | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Ethnicity | Saudi | Saudi | NA | NA | NA | NA | Pakistani | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Consanguinity | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age of onset | 5 months | 1 year | 18 months | 6 months | 18 years | 16 years | 8 months | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Initial symptom | Tetany, BRIC | Normal GGT cholestasis | BRIC | Jaundice, itching, pruritus, normal GGT cholestasis | BRIC, cholangiopathy | BRIC | Jaundice, itching, and pigmented stools | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Other symptoms | Hypocalcemia, intractable itching | Intractable itching | Itching, speech and developmental delay | Itching | Itching | Itching, hypothyroidism | Hypoalbuminemia, hypoproteinemia, intrahepatic cholestasis, leukocytosis, prolonged prothrombin time, thrombocytosis | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Laboratory AST, IU/L | 29 | 352 | 61 | 69 | 45 | 80 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| ALT, IU/L | 25 | 136 | 51 | 36 | 45 | 63 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| ALP, IU/L | 4,432 | 2,557 | 719 | 504 | 939 | 727 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| GGT, IU/L | 39 | 30 | 24 | 23 | 39 | 23 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 26 | 402 | 155 | 146 | 876 | 179 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Direct bilirubin, mg/dL | 20 | 298 | 85 | 142 | 680 | 128 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Serum bile acid levels, µmol/L | 79 | 163 | 155 | 353 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Abdomen USG | NA | NA | Enlarged left echogenic kidney | NA | Gallstone | NA | Hepatomegaly | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Liver biopsy | NA | NA | Mild lobular and portal inflammation and stage 2 fibrosis with septae formation | NA | Bland cholestasis, florid ductular proliferation, cholestasis, cholate stasis, feathery degeneration of hepatocytes, septal fibrosis, and mixed inflammatory infiltration | Canalicular cholestasis with early ductular proliferation, but no fibrosis | Intrahepatic cholestasis | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Hearing | Deafness | None | None | None | None | None | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Treatment | NA | NA | UDCA | UDCA and rifampicin | Steroids, UDCA and cholestyramine, azathioprine | Prednisolone, thyroxin | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Situation of after the treatment | Alive with native liver (17 years) | Alive with native liver (6 years) | Alive with native liver (7 years) | Alive with native liver (1 years) | Alive with native liver (35 years) | Alive with native liver (18 years) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| USP53 (Transcript) | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_01,050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 | NM_019050.2 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Nucleotide change | c.951delT | c.951delT | c.951delT | c.1744C>T | c.1744C>T | c.1744C>T | c.1524T>G | c.169C>T | c.475_476delCT | c.822+1delG | c.951delT | c.1214dupA |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Protein change | p.Phe317fs | p.Phe317fs | p.Phe317fs | p. Arg582* | p. Arg582* | p. Arg582* | p.Tyr508* | p.Arg57* | p.Leu159fs | p:? | p.Phe317fs | p.Asn405fs |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Variant type | Frameshift | Frameshift | Frameshift | Nonsense | Nonsense | Nonsense | Nonsense | Nonsense | Frameshift | Splice | Frameshift | Frameshift |

|

| ||||||||||||

| ACMG classification | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic |

It has been reported in the literature that patients with USP53-related cholestasis generally respond to medical treatment. However, liver transplantation was performed in only one case who had intractable itching that did not respond to medical treatment. It was also stated that the case may not have had a chance to be treated with rifampicin 20 years ago. In the same article, it was reported that intractable itching during BRIC episodes was also reported in 2 other adult patients that led to depression and suicide attempts [Alhebbi et al., 2021].

Due to intractable itching that did not respond to antihistamines, our patient was also started on rifampicin. At the 3-months follow-up, ALT, AST and bilirubin levels returned to normal and itching improved dramatically. Although early fibrosis has been described, cholestasis is transient in most patients with variants in USP53 [Porta et al., 2021]. Our patient also had porto-portal, porto-central, and centrilobular fibrosis as a result of liver biopsy performed at the age of 9 months. We recommend patients should be monitored closely to assess progression to fibrosis.

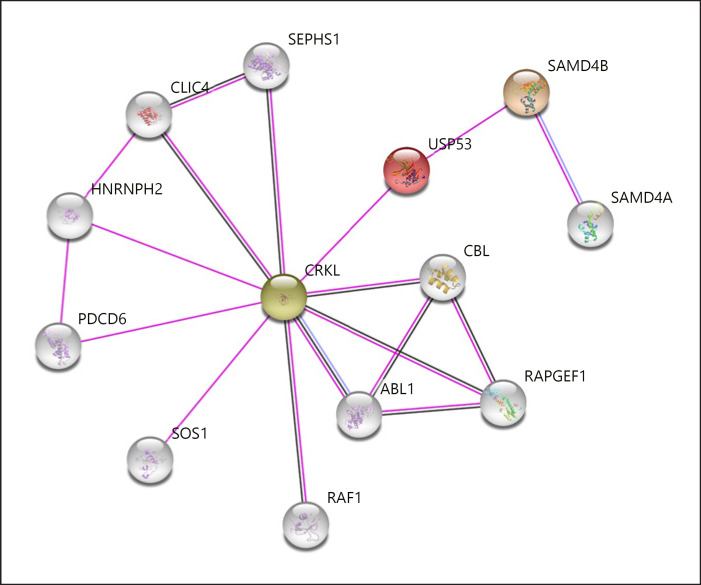

USP53, a member of the ubiquitin specific proteases involved in the deconjugation of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like protein adducts, is a cysteine protease with complex organizational structures and different functional properties [Wing, 2003]. All known USPs contain 3 basic domains called Cys-box, QQD-box, and Her-box important for their catalytic activity [Amerik et al., 1997; Wilkinson, 1997; D'Andrea and Pellman, 1998]. The generated model demonstrated the successful formation of the conserved catalytic triad in all other known USPs (Fig. 5a). Asp108 is located near the catalytic triad of Cys41, His301, and Asp319 and may be responsible for substrate stability. Apart from this core catalytic domain, the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of the protein may be important for substrate specificity and cellular localization. Although conserved Rossman fold-like structures in the N-terminal region reveal an irregular formation, they may provide data on the secondary functions of USP53 (tight junction, interaction with multiple substrates, and additional regulatory roles) (Fig. 5b). The protein sequence of USP53, which terminated early with mutation, brought about the loss of protein structure including functional properties. The functional deficiency of USP53 will also disrupt the metabolic and regulatory processes with which it interacts. The elucidation of the molecular basis of cholestasis will be possible with a detailed analysis of the USP53 interaction map (Fig. 6). The relationship between USP53 and Crk-like protein (CRKL) in the interaction network created by considering the experimental data is remarkable. CRKL acts as a control interface that mediates intracellular signal transduction in many processes including transcriptional repression, apoptotic mechanisms, ensuring membrane integrity, and substance transport. Chloride intracellular channel protein 4 co-expressed with CRKL maintains basolateral membrane polarity, induces endothelial cell proliferation, and creates selective ion channels [Berryman and Goldenring, 2003; Littler et al., 2005; Tung et al., 2009]. Programmed cell death protein 6 is a calcium sensor protein involved in processes such as endoplasmic reticulum-golgi vesicular transport and membrane repair. Activation with calcium triggers the formation of 3 different hydrophobic pockets that allow interaction with different protein groups, thus enabling translocation [Inuzuka et al., 2010; Takahashi et al., 2015; McGourty et al., 2016]. Tyrosine-protein kinase ABL1 co-expressed with CRKL plays a key role in many vital cellular processes such as cytoskeletal remodeling, cell motility, cell adhesion, receptor endocytosis, autophagy, apoptosis, and response to DNA damage [Yuan et al., 1997; Raina et al., 2005; Yogalingam and Pendergast, 2008]. Another Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor-1 co-expressed with CRKL is important in establishing basal endothelial barrier function [Pannekoek et al., 2011]. SAMD4B, which represses the translations of activator protein-1, tumor protein-53, and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A, and E3-ubiquitin-protein ligase CBL, which acts as a negative regulator of many signaling pathways, are genes that interact directly or indirectly with USP53 [Baez and Boccaccio, 2005].

Fig. 5.

a Cartoon illustration of the catalytic site of wild-type USP53. Red color: cysteine-box, yellow: histidine-box, magenta: QQD-box, blue color: residues of catalytic triad. b Cartoon illustration of the irregular Rossman solid-like beta sheet formation located in the N-terminal domain region of wild-type USP53.

Fig. 6.

Relationship network of the USP53 gene [Szklarczyk et al., 2019]. Purple line: experimentally determined, black line: co-expression, blue line: protein homology.

As detailed above, USP53 has critical roles in many important processes for the cell, especially substance transport, membrane permeability, membrane stability, apoptotic processes, repair, and regulation at the transcriptional/translational level. Loss of UPS53 function due to c.238–1G>C variation may cause disruption or deterioration in these processes. The disruption that will occur in the mechanisms that regulate the transport and passage of various biological components and the deterioration in the mechanisms that will control these malfunctions will reveal a process that results in the passage of bile into the systemic circulation, as in cholestasis. In particular, weaknesses that affect membrane stability, cell adhesion, and the stability of tight junctions can result in leakage of bile salts into the plasma. The C-terminal domain of USP53 interacts with the TJP1 and TJP2 heterodimer associated with cholestasis risk [Sambrotta et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2020a]. TJP2 belongs to a family of membrane-associated guanylate cyclase homologs involved in the organization of tight junctions. Tight junctions in hepatocytes are important in separating bile from plasma and the canalicular membrane area from the sinusoidal membrane area. TJP2 is hypothesized to affect the tight junction structure by binding to claudins and occluding. It has been suggested that weakness in tight junctions may result in leakage of bile salts into the plasma and high serum bile salt concentrations [Jesaitis and Goodenough, 1994; McCarthy et al., 2000; Carlton et al., 2003]. The c.238–1G>C variant abolishes the USP53-TJP2 interaction, which can result in weakening of tight junctions and leakage of bile salts into the plasma.

Conclusion

In this study, where we propose a model for the tertiary structure of USP53 for the first time, together with all these data, we support the association of biallelic variants of USP53 with cholestasis phenotype. Although the USP53 gene has not yet been associated with any phenotype in OMIM, we propose to include USP53 in next-generation sequencing panels used to investigate the genetic etiology of hereditary cholestasis. In addition, we recommend re-analysis of cholestatis patients who have undergone exome sequencing and for whom no genetic diagnosis has been established.

Statement of Ethics

All authors were compliant and followed ethical guidelines according to JIMD requirements. Samples from the patients were obtained in accordance with the Helsinki Declarations. The patient's parents gave permission to participate in this study and to publish their data. Informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents. This study was approved by ethics committee of Basaksehir Cam and Sakura City Hospital (KAEK/2021.11.270). All authors gave consent for the article to be published in Molecular Syndromology.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

There was no funding.

Author Contributions

A.G. designed the study, analyzed, and interpreted genetic data. A.G., Ö.K.Ş., and B.Y.Ö. collected clinical and laboratory data. A.G. and M.D. drafted the manuscript. E.A. helped in bioinformatic analyses. Ö.K.Ş. and E.A. helped to write the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the family members for their kind cooperation in this study.

Funding Statement

There was no funding.

References

- 1.Alhebbi H, Peer-Zada AA, Al-Hussaini AA, Algubaisi S, Albassami A, AlMasri N, et al. New paradigms of USP53 disease: normal GGT cholestasis, BRIC, cholangiopathy, and responsiveness to rifampicin. J Hum Genet. 2021;66((2)):151–159. doi: 10.1038/s10038-020-0811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amerik A, Swaminathan S, Krantz BA, Wilkinson KD, Hochstrasser M. In vivo disassembly of free polyubiquitin chains by yeast Ubp14 modulates rates of protein degradation by the proteasome. EMBO J. 1997;16((16)):4826–4838. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amirneni S, Haep N, Gad MA, Soto-Gutierrez A, Squires JE, Florentino RM. Molecular overview of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26((47)):7470–7484. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i47.7470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baez MV, Boccaccio GL. Mammalian Smaug is a translational repressor that forms cytoplasmic foci similar to stress granules. J Biol Chem. 2005;280((52)):43131–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berryman MA, Goldenring JR. CLIC4 is enriched at cell-cell junctions and colocalizes with AKAP350 at the centrosome and midbody of cultured mammalian cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2003;56((3)):159–172. doi: 10.1002/cm.10141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchan DW, Minneci F, Nugent TC, Bryson K, Jones DT. Scalable web services for the PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W349–57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt381. (Web Server issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bull LN, Ellmers R, Foskett P, Strautnieks S, Sambrotta M, Czubkowski P, et al. Cholestasis Due to USP53 Deficiency. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021;72((5)):667–673. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caminsky N, Mucaki EJ, Rogan PK. Interpretation of mRNA splicing mutations in genetic disease: review of the literature and guidelines for information-theoretical analysis. F1000Res. 2014;3:282. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.5654.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlton VE, Harris BZ, Puffenberger EG, Batta AK, Knisely AS, Robinson DL, et al. Complex inheritance of familial hypercholanemia with associated mutations in TJP2 and BAAT. Nat Genet. 2003;34((1)):91–96. doi: 10.1038/ng1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheema H, Bertoli-Avella AM, Skrahina V, Anjum MN, Waheed N, Saeed A, et al. Genomic testing in 1019 individuals from 349 Pakistani families results in high diagnostic yield and clinical utility. NPJ Genom Med. 2020;5:44. doi: 10.1038/s41525-020-00150-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Andrea A, Pellman D. Deubiquitinating enzymes: a new class of biological regulators. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;33((5)):337–352. doi: 10.1080/10409239891204251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inuzuka T, Suzuki H, Kawasaki M, Shibata H, Wakatsuki S, Maki M. Molecular basis for defect in Alix-binding by alternatively spliced isoform of ALG-2 (ALG-2DeltaGF122) and structural roles of F122 in target recognition. BMC Struct Biol. 2010;10:25. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-10-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jesaitis LA, Goodenough DA. Molecular characterization and tissue distribution of ZO-2, a tight junction protein homologous to ZO-1 and the Drosophila discs-large tumor suppressor protein. J Cell Biol. 1994;124((6)):949–961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.6.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kazmierczak M, Harris SL, Kazmierczak P, Shah P, Starovoytov V, Ohlemiller KK, et al. Progressive Hearing Loss in Mice Carrying a Mutation in Usp53. J Neurosci. 2015;35((47)):15582–98. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1965-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35((6)):1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Littler DR, Assaad NN, Harrop SJ, Brown LJ, Pankhurst GJ, Luciani P, et al. Crystal structure of the soluble form of the redox-regulated chloride ion channel protein CLIC4. FEBS J. 2005;272((19)):4996–5007. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maddirevula S, Alhebbi H, Alqahtani A, Algoufi T, Alsaif HS, Ibrahim N, et al. Identification of novel loci for pediatric cholestatic liver disease defined by KIF12, PPM1F, USP53, LSR, and WDR83OS pathogenic variants. Genet Med. 2019;21((5)):1164–1172. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy KM, Francis SA, McCormack JM, Lai J, Rogers RA, Skare IB, et al. Inducible expression of claudin-1-myc but not occludin-VSV-G results in aberrant tight junction strand formation in MDCK cells. J Cell Sci. 2000;113((Pt 19)):3387–3398. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.19.3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGourty CA, Akopian D, Walsh C, Gorur A, Werner A, Schekman R, et al. Regulation of the CUL3 Ubiquitin Ligase by a Calcium-Dependent Co-adaptor. Cell. 2016;167((2)):525–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitani T, Isikay S, Gezdirici A, Gulec EY, Punetha J, Fatih JM, et al. High prevalence of multilocus pathogenic variation in neurodevelopmental disorders in the Turkish population. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108((10)):1981–2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mucaki EJ, Shirley BC, Rogan PK. Prediction of mutant mRNA splice isoforms by information theory-based exon definition. Hum Mutat. 2013;34((4)):557–565. doi: 10.1002/humu.22277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicastro E, Di Giorgio A, Marchetti D, Barboni C, Cereda A, Iascone M, et al. Diagnostic Yield of an Algorithm for Neonatal and Infantile Cholestasis Integrating Next-Generation Sequencing. J Pediatr. 2019;211:54.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pannekoek WJ, van Dijk JJ, Chan OY, Huveneers S, Linnemann JR, Spanjaard E, et al. Epac1 and PDZ-GEF cooperate in Rap1 mediated endothelial junction control. Cell Signal. 2011;23((12)):2056–2064. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pehlivan D, Bayram Y, Gunes N, Coban Akdemir Z, Shukla A, Bierhals T, et al. The Genomics of Arthrogryposis, a Complex Trait: Candidate Genes and Further Evidence for Oligogenic Inheritance. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105((1)):132–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porta G, Rigo PSM, Porta A, Pugliese RPS, Danesi VLB, Oliveira E, et al. Progressive Familial Intrahepatic Cholestasis Associated With USP53 Gene Mutation in a Brazilian Child. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021;72((5)):674–676. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000003110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quesada V, Díaz-Perales A, Gutiérrez-Fernández A, Garabaya C, Cal S, López-Otín C. Cloning and enzymatic analysis of 22 novel human ubiquitin-specific proteases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314((1)):54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raina D, Pandey P, Ahmad R, Bharti A, Ren J, Kharbanda S, et al. c-Abl tyrosine kinase regulates caspase-9 autocleavage in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2005;280((12)):11147–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17((5)):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roehlen N, Roca Suarez AA, El Saghire H, Saviano A, Schuster C, Lupberger J, et al. Tight Junction Proteins and the Biology of Hepatobiliary Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21((3)) doi: 10.3390/ijms21030825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrotta M, Strautnieks S, Papouli E, Rushton P, Clark BE, Parry DA, et al. Mutations in TJP2 cause progressive cholestatic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2014;46((4)):326–328. doi: 10.1038/ng.2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shatokhina O, Semenova N, Demina N, Dadali E, Polyakov A, Ryzhkova O. A Two-Year Clinical Description of a Patient with a Rare Type of Low-GGT Cholestasis Caused by a Novel Variant of USP53. Genes (Basel) 2021;12((10)):1618. doi: 10.3390/genes12101618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sticova E, Jirsa M, Pawłowska J. New Insights in Genetic Cholestasis: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:2313675. doi: 10.1155/2018/2313675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47((D1)):D607–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi T, Kojima K, Zhang W, Sasaki K, Ito M, Suzuki H, et al. Structural analysis of the complex between penta-EF-hand ALG-2 protein and Sec31A peptide reveals a novel target recognition mechanism of ALG-2. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16((2)):3677–3699. doi: 10.3390/ijms16023677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tung JJ, Hobert O, Berryman M, Kitajewski J. Chloride intracellular channel 4 is involved in endothelial proliferation and morphogenesis in vitro. Angiogenesis. 2009;12((3)):209–220. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9139-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vij M, Sankaranarayanan S. Biallelic Mutations in Ubiquitin-Specific Peptidase 53 (USP53) Causing Progressive Intrahepatic Cholestasis. Report of a Case With Review of Literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2021:10935266211051175. doi: 10.1177/10935266211051175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang NL, Lu YL, Zhang P, Zhang MH, Gong JY, Lu Y, et al. A Specially Designed Multi-Gene Panel Facilitates Genetic Diagnosis in Children with Intrahepatic Cholestasis: Simultaneous Test of Known Large Insertions/Deletions. PLoS One. 2016;11((10)):e0164058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, Studer G, Tauriello G, Gumienny R, et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46((W1)):W296–303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W407–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. (Web Server issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkinson KD. Regulation of ubiquitin-dependent processes by deubiquitinating enzymes. FASEB J. 1997;11((14)):1245–1256. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.14.9409543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wing SS. Deubiquitinating enzymes--the importance of driving in reverse along the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35((5)):590–605. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J, Anishchenko I, Park H, Peng Z, Ovchinnikov S, Baker D. Improved protein structure prediction using predicted interresidue orientations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117((3)):1496–1503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914677117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yogalingam G, Pendergast AM. Abl kinases regulate autophagy by promoting the trafficking and function of lysosomal components. J Biol Chem. 2008;283((51)):35941–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804543200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan ZM, Huang Y, Ishiko T, Kharbanda S, Weichselbaum R, Kufe D. Regulation of DNA damage-induced apoptosis by the c-Abl tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94((4)):1437–1440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J, Liu LL, Gong JY, Hao CZ, Qiu YL, Lu Y, et al. TJP2 hepatobiliary disorders: Novel variants and clinical diversity. Hum Mutat. 2020a;41((2)):502–511. doi: 10.1002/humu.23947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J, Yang Y, Gong JY, Li LT, Li JQ, Zhang MH, et al. Low-GGT intrahepatic cholestasis associated with biallelic USP53 variants: Clinical, histological and ultrastructural characterization. Liver Int. 2020b;40((5)):1142–1150. doi: 10.1111/liv.14422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.