Abstract

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, the causative agent of porcine pleuropneumonia, contains a periplasmic Cu- and Zn-cofactored superoxide dismutase ([Cu,Zn]-SOD, or SodC) which has the potential, realized in other pathogens, to promote bacterial survival during infection by dismutating host-defense-derived superoxide. Here we describe the construction of a site-specific, [Cu,Zn]-SOD-deficient A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 mutant and show that although the mutant is highly sensitive to the microbicidal action of superoxide in vitro, it remains fully virulent in experimental pulmonary infection in pigs.

The gram-negative bacterium Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae causes porcine pleuropneumonia, a highly contagious infection of pigs that is responsible for substantial economic losses worldwide. First described in 1957, A. pleuropneumoniae infection has become more frequent in recent years, particularly where animals are subjected to intensive breeding conditions (29, 33). Infection is highly host specific, and organisms spread from one animal to another via respiratory droplets (27, 33). The disease is characterized by increasingly severe pulmonary distress leading to death after 24 to 48 h or to chronic infection resulting in a failure to thrive (14, 33). No effective vaccine strategy has yet been devised to prevent infection. In the process of elucidating the sequence of critical interactions between organism and host that lead to severe disease, capsule, lipopolysaccharide, RTX-like toxins (ApxI to ApxIVA), lipoproteins, secreted proteases, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) have been identified as potential determinants of virulence (9, 12, 18, 26, 28, 32). This defines at once the potential of purified gene products or knockout mutant A. pleuropneumoniae strains for use as subunit or live-attenuated vaccines, respectively, and the recent development of genetic systems for A. pleuropneumoniae (15, 25, 37, 40) now allows these possibilities to be formally investigated.

The gene sodC, which encodes the copper- and zinc-cofactored SOD ([Cu,Zn]-SOD) of A. pleuropneumoniae, was previously identified, cloned, and sequenced in this laboratory (17, 18). SODs are metalloproteins that catalyze the dismutation of the highly reactive superoxide radical anion to hydrogen peroxide and oxygen (22). This is the first step in a series of reactions which prevent the accumulation of cytotoxic oxygen free radicals and nitrogen free radicals generated by the reduction of molecular oxygen. SODs are classified according to the metalloprotein at their active site, and three major forms have been identified in bacteria. Iron- and manganese-cofactored SODs are located in the cytoplasm and serve to remove superoxide anions generated during the course of aerobic respiration (10). In contrast, in all cases where location has been determined experimentally, bacterial [Cu,Zn]-SODs have been shown to be periplasmic (18; reference 31 and references therein). As superoxide is unable to cross the cytoplasmic membrane (13), it has been suggested that [Cu,Zn]-SOD provides protection from superoxide generated outside the cell. During the course of infection, many bacterial pathogens are exposed to high levels of activated oxygen species generated by inflammatory cells during the respiratory burst. The theoretical capacity of bacterial [Cu,Zn]-SODs to dismutate exogenous superoxide suggests a role for these enzymes in pathogenesis. In support of this hypothesis, Neisseria meningitidis and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains deficient in [Cu,Zn]-SOD production are attenuated in the mouse model of infection (5, 8, 41). However, the picture is not clear-cut. For example, two groups have presented conflicting evidence for the role of [Cu,Zn]-SOD in the growth and multiplication of Brucella abortus in BALB/c mice (19, 38). To investigate the role of [Cu,Zn]-SOD in the pathogenesis of A. pleuropneumoniae infection and to assess the live-vaccine potential of a [Cu,Zn]-SOD-deficient mutant, we have constructed a sodC mutant of A. pleuropneumoniae strain 4074 by allele exchange. We investigated the impact of this mutation on virulence in experimental infections of the natural host, the pig.

Construction of A. pleuropneumoniae sodC mutant.

The cloned sodC gene was interrupted by the insertion of a kanamycin resistance cassette (Kanr) at the unique EcoNI site located 144 bp downstream from the sodC initiation codon. Briefly, a 3.4-kb EcoRI-EcoRV fragment containing A. pleuropneumoniae sodC was excised from pJSK150 (18) and cloned into pBluescript to generate plasmid pJSK155. A 1.3-kb HincII fragment containing Kanr from plasmid pB16 (pB16 is a precursor to pB51 [35] and contains the Tn903 Kanr gene flanked on either side by a polylinker containing various restriction sites including the HincII site) was then cloned into pJSK155 that had been linearized with EcoNI and Klenow treated to generate blunt ends. The resultant plasmid, designated pJSK333, was transferred into A. pleuropneumoniae strain 4074 (serotype 1) by electroporation (15, 24). As the ColE1 origin of plasmid pJSK333 does not function in A. pleuropneumoniae, kanamycin-resistant transformants can only arise following recombination between the mutant sodC allele and wild-type sodC sequences by single or double crossover. After 48 h of growth, three kanamycin-resistant transformants were isolated on selective brain heart infusion plates supplemented with 10% Levinthal's base (1). Southern blot and PCR analysis with sodC-specific oligonucleotide primers demonstrated that in all cases the mutant sodC::Kan allele had replaced the wild-type sodC gene on the chromosome in a double crossover event (data not shown). As sodC is expressed as a monocistronic unit (21), insertion of the antibiotic cassette would not be expected to exert a polar effect on the activity of neighboring genes. One isolate, SK564, was used in subsequent experiments.

SOD expression in wild type and sodC mutants of A. pleuropneumoniae.

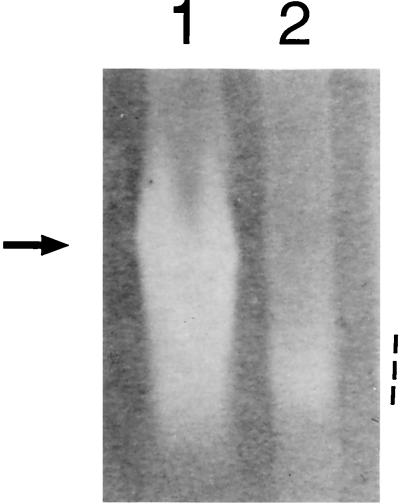

To verify that [Cu,Zn]-SOD production was abrogated in strain SK564, wild-type and SK564 mutant strains were grown aerobically in liquid culture until the stationary phase of growth. Whole-cell sonicates were separated electrophoretically on nondenaturing gels and stained for SOD activity as described previously (18). Two bands of SOD activity were observed when wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae was grown under nutrient-replete, aerobic conditions (Fig. 1) (17). Mn-SOD activity, manifested as a diffuse, achromatic zone at a position of relatively high mobility, was present in both wild-type and SK564 mutant extracts (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, [Cu,Zn]-SOD activity was present only in wild-type extracts (the prominent achromatic band in Fig. 1, lane 1) and was absent from extracts derived from the sodC::Kan strain, SK564 (Fig. 1, lane 2).

FIG. 1.

SOD activity of whole-cell sonicates of A. pleuropneumoniae strains 4074 (wild type, lane 1) and SK564 (sodC::Kan, lane 2). Each lane contained approximately 40 μg of total protein. [Cu,Zn]-SOD activity in the wild-type extract is indicated by the arrow. The more diffuse Mn-SOD activity, present in both lanes, is indicated by the dashed line.

Effect of sodC mutation on susceptibility to exogenous superoxide in vitro.

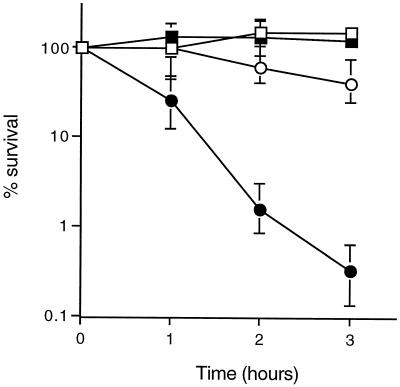

The A. pleuropneumoniae wild type and sodC mutant strain SK564 were exposed to exogenous superoxide generated by the oxidation of xanthine as described previously (8). Production of superoxide in solution was initiated by the addition of 0.1 U of xanthine oxidase/ml, and bacterial survival was monitored by estimation of viable counts at hourly intervals over a 3-h period. The viability of wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae was unaffected by superoxide in vitro (100% survival or greater) (Fig. 2). In contrast, sodC mutant bacteria were highly susceptible to the microbicidal action of superoxide; 99% of mutant bacteria were killed after 3 h of incubation in the presence of xanthine oxidase (Fig. 2). Thus, the A. pleuropneumoniae [Cu,Zn]-SOD plays a crucial role in the detoxification of exogenously generated superoxide, allowing bacteria to survive challenge with superoxide in vitro. These results are comparable to those obtained with other organisms; Salmonella serovar Typhimurium and N. meningitidis mutants lacking [Cu,Zn]-SOD were strikingly more susceptible than otherwise isogenic wild-type bacteria to superoxide generated in solution by the xanthine-xanthine oxidase system (5, 8, 41).

FIG. 2.

Effect of the sodC mutation on survival of A. pleuropneumoniae exposed to superoxide in vitro. Survival of wild type bacteria (squares) and sodC mutant bacteria (circles) in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1 mM xanthine (open symbols) and in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1 mM xanthine and 0.1 U of xanthine oxidase/ml (filled symbols) is shown. Data (means and ranges for duplicate experiments) are percentages of the starting cell density (range, 1 × 108 to 2.5 × 108 CFU/ml).

Virulence of SodC-defective A. pleuropneumoniae.

In the cases of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium and N. meningitidis sodC mutants, susceptibility to exogenous superoxide in vitro correlates with susceptibility to killing by superoxide-mediated host defense mechanisms and to attenuation of virulence in mouse models of infection (5, 8, 41). As challenge with A. pleuropneumoniae is known to elicit a vigorous respiratory burst of oxygen free radical production from porcine neutrophils (7), we investigated the effect of sodC mutation on the course of A. pleuropneumoniae infection in the natural (porcine) host. Two groups of seven 4-week-old, conventionally weaned piglets determined to be A. pleuropneumoniae free by bacteriological and serological analyses were inoculated intratracheally (30) with a range of doses of either strain 4074 (group B) or strain SK564 (group A), as detailed in Table 1. No significant difference was seen at any dose. Both animals receiving the high dose (ca. 2 × 107 CFU) and one of two animals given the intermediate dose (ca. 2 × 105 CFU) but no animal given the low dose (ca. 4 × 103 CFU) in group A or B developed clinical signs of respiratory disease within 36 h (Table 1). Surviving animals were euthanized after 42 h.

TABLE 1.

Virulence of wild type (strain 4074) and sodC::Kan mutant (strain SK564) of A. pleuropneumoniae in experimental porcine infection

| Group | Strain | Viable count (ml−1) | No. of pigs with finding/no. tested

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory signs | Pulmonary lesions | Reisolation from lung | |||

| A | sodC::Kan | 2 × 107 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| 2 × 105 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1/2 | ||

| 4 × 103 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | ||

| B | Wild type | 2.3 × 107 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| 2.3 × 105 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1/2 | ||

| 4.7 × 103 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | ||

Hemorrhagic pulmonary lesions and fibrinous pleurisy typical of A. pleuropneumoniae infection were demonstrated in all animals showing clinical signs of disease. The reisolation of A. pleuropneumoniae confirmed the etiology of the lesions in each case (Table 1), and the identity of the bacterial isolates as the mutant or wild-type strain was confirmed by PCR establishing the absence (wild type) or presence (mutant) of the Kanr cassette (data not shown). No lesions were observed in animals without clinical signs, and no bacteria were recovered from the lungs of these animals. The pathology of the lesions in pigs infected with the sodC mutant strain was indistinguishable from that of lesions caused by the parent strain, 4074, with extensive infiltration of alveolar spaces by inflammatory cells and areas of edema, fibrinous exudate, and hemorrhage (data not shown). Thus, in contrast to results for Salmonella serovar Typhimurium and N. meningitidis—and despite a demonstrable, pivotal role of [Cu,Zn]-SOD in resistance to exogenous superoxide in vitro—we could not identify a clinically significant role for [Cu,Zn]-SOD in the pathogenesis of A. pleuropneumoniae infection.

Plainly, a sodC mutant of otherwise wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae that retains wild-type virulence would not be suitable as a live vaccine strain to prevent porcine pleuropneumonia. We infer from the contrast between the unimpaired virulence of a sodC-defective strain of A. pleuropneumoniae and the attenuation of corresponding mutants of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium and N. meningitidis a fundamental difference in the way that these pathogens interact with phagocytic cells.

A. pleuropneumoniae causes disease predominantly as an extracellular pathogen, with little evidence for a significant intracellular phase (3, 6). Pulmonary defense against A. pleuropneumoniae is mediated by resident alveolar macrophages and by migratory neutrophils that are recruited to the lung alveoli as early as 3 h after the onset of infection (20, 34). Although infection elicits a vigorous neutrophil and alveolar macrophage response in vitro with a substantial respiratory burst of oxygen free-radical production (7), these cells are rapidly killed by the bacteria. This toxicity is principally mediated by the secreted bacterial cytolytic toxins ApxI and ApxII (3, 15, 39), toxins which also inhibit neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis (36). Only in the absence of Apx toxins or in the presence of convalescent-stage pig serum are significant numbers of A. pleuropneumoniae internalized by neutrophils, and evidence suggests that once internalized the bacteria are rapidly killed (2, 3). Thus, while our in vitro data demonstrate the potential for [Cu,Zn]-SOD to facilitate bacterial survival in an oxygen free radical-rich environment, this survival mechanism appears to be redundant (at least during acute experimental infection) in the presence of the potent Apx toxins. In contrast, the pathogenetic sequence of infection with either N. meningitidis or Salmonella serovar Typhimurium includes subversion of the antibacterial action of phagocytic cells and their colonization rather than destruction, in a necessary prelude to tissue invasion and/or chronic intracellular infection (16, 23). In these circumstances, it seems plausible that bacterial [Cu,Zn]-SOD may play a more critical role in the interactive biology of host and pathogen.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Meningitis Research Foundation, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, and the Wellcome Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander H E. The Haemophilus group. In: Dubosand R J, Hirdch J G, editors. Bacterial and mycotic infections of man. London, England: Pittman Medical Publishing Co.; 1965. pp. 724–741. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruijsen T L M, Van Leengoed L A M G, Dekker-Nooren T C E M, Schoevers E J, Verheijden J H M. Phagocytosis and killing of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae by alveolar macrophages and polymorphonuclear leukocytes isolated from pigs. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4867–4871. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4867-4871.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cullen J M, Rycroft A N. Phagocytosis by pig alveolar macrophages of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 2 mutant strains defective in haemolysin II (ApxII) and pleurotoxin (ApxIII) Microbiology. 1994;140:237–244. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-2-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis B J. Disc electrophoresis. II. Method and application to human serum proteins. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1964;121:404–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1964.tb14213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Groote M A, Ochsner U A, Shiloh M U, Nathan C, McCord J M, Dinauer M C, Libby S J, Vazquez-Torres A, Xu Y, Fang F C. Periplasmic superoxide dismutase protects Salmonella from products of phagocyte NADPH-oxidase and nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13997–14001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dom P, Haesebrouck F, Ducatelle R, Charlier G. In vivo association of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 2 with the respiratory epithelium of pigs. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1262–1267. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1262-1267.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dom P, Haesebrouck F, Kamp E M, Smits M A. Influence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 2 and its cytolysins on porcine neutrophil chemiluminescence. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4328–4334. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4328-4334.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrant J L, Sansone A, Canvin J R, Pallen M J, Langford P R, Wallis T S, Dougan G, Kroll J S. Bacterial copper- and zinc-cofactored superoxide dismutase contributes to the pathogenesis of systemic salmonellosis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:785–796. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5151877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frey J. Virulence in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and RTX toxins. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:257–261. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88939-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fridovich I. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:97–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller T E, Thacker B J, Mulks M H. A riboflavin auxotroph of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae is attenuated in swine. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4659–4664. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4659-4664.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerlach G-F, Anderson C, Klashinsky S, Rossi-Campos A, Potter A A, Willson P J. Molecular characterization of a protective outer membrane lipoprotein (OmlA) from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1. Infect Immun. 1993;61:565–572. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.565-572.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassan H M, Fridovich I. Paraquat and Escherichia coli. Mechanism of production of extracellular superoxide radical. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:10846–10852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inzana T J. Virulence properties of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Microb Pathog. 1991;11:305–316. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansen R, Briaire J, Smith H E, Dom P, Haesebrouck F, Kamp E M, Gielkens A L, Smits M A. Knockout mutants of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 that are devoid of RTX toxins do not activate or kill porcine neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1995;63:27–37. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.27-37.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones B D, Falkow S. Salmonellosis: host immune responses and bacterial virulence determinants. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:533–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroll J S, Langford P R, Wilks K E, Keil A D. Bacterial [Cu,Zn]-superoxide dismutase: phylogenetically distinct from the eukaryotic enzyme, and not so rare after all! Microbiology. 1995;141:2271–2279. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-9-2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langford P R, Loynds B M, Kroll J S. Cloning and molecular characterization of Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5035–5041. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5035-5041.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latimer E, Simmers J, Sriranganathan N, Roop II R M, Schurig G G, Boyle S M. Brucella abortus deficient in copper/zinc superoxide dismutase is virulent in BALB/c mice. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liggett A D, Harrison L R, Farrell R L. Sequential study of lesion development in experimental haemophilus pleuropneumonia. Res Vet Sci. 1987;42:204–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loynds B M, Langford P R, Kroll J S. recF in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:615. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.3.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCord J M, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymatic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein) J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNeil G, Virji M, Moxon E R. Interactions of Neisseria meningitidis with human monocytes. Microb Pathog. 1994;16:153–163. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller J F, Dower W J, Tompkins L S. High-voltage electroporation of bacteria: genetic transformation of Campylobacter jejuni with plasmid DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:856–860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.3.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulks M H, Buysse J M. A targeted mutagenesis system for Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Gene. 1995;165:61–66. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00528-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Negrete-Abascal E, Tenorio V R, Serrano J J, Garcia C, de la Garza M. Secreted proteases from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 degrade porcine gelatin, hemoglobin and immunoglobulin A. Can J Vet Res. 1994;58:83–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolet J. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. In: Leaman A D, Straw B E, Mengeling S, D'Allaire S, Taylor D J, editors. Diseases of swine. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1992. pp. 401–408. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paradis S-E, Dubreuil D, Rioux S, Gottschalk M, Jacques M. High-molecular-mass lipopolysaccharides are involved in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae adherence to porcine respiratory tract cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3311–3319. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3311-3319.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pattison I H, Howell D G, Elliot J. A Haemophilus-like organism isolated from pig lung and the associated pneumonic lesions. J Comp Pathol. 1957;67:320–329. doi: 10.1016/s0368-1742(57)80031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rycroft A N, Williams D, McCandlish I A, Taylor D J. Experimental reproduction of acute lesions of porcine pleuropneumonia with a haemolysin-deficient mutant of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Vet Rec. 1991;16:441–443. doi: 10.1136/vr.129.20.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.San Mateo L R, Hobbs M M, Kawula T H. Periplasmic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase protects Haemophilus ducreyi from exogenous superoxide. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:391–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schaller A, Khun R, Kuhnert P, Nicolet J, Anderson T J, MacInnes J I, Segers R P A M, Frey J. Characterization of apxIVA, a new RTX determinant of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Microbiology. 1999;145:2105–2116. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-8-2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sebunya T N K, Saunders J R. Haemophilus pleuropneumoniae infections in swine: a review. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983;182:1331–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sibille Y, Reynolds H Y. Macrophages and polymorphonuclear neutrophils in lung defense and injury. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:471–501. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.2.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szabo M, Maskell D, Butler P, Love J, Moxon R. Use of chromosomal gene fusions to investigate the role of repetitive DNA in regulation of genes involved in lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7245–7252. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7245-7252.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarigan S, Slocombe R F, Browning G F, Kimpton W. Functional and structural changes of porcine alveolar macrophages induced by sublytic doses of a heat-labile, hemolytic, cytotoxic substance produced by Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Am J Vet Res. 1994;55:1548–1557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tascon R I, Vazquez-Boland J A, Gutierrez C B, Rodriguez-Barbosa J I, Rodriguez-Ferri E F. The RTX haemolysins ApxI and ApxII are major virulence factors of the swine pathogen Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae: evidence from mutational analysis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tatum F M, Detilleux P G, Sacks J M, Halling S M. Construction of Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase deletion mutants of Brucella abortus: analysis of survival in vitro in epithelial and phagocytic cells and in vivo in mice. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2863–2869. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2863-2869.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Udeze F A, Kadis S. Effects of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae hemolysin on porcine neutrophil function. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1558–1567. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1558-1567.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ward C K, Lawrence M L, Veit H P, Inzana T J. Cloning and mutagenesis of a serotype-specific DNA region involved in encapsulation and virulence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5a: concomitant expression of serotype 5a and 1 capsular polysaccharides in recombinant A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3326–3336. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3326-3336.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilks K E, Dunn K L R, Farrant J L, Reddin K M, Gorringe A R, Langford P R, Kroll J S. Periplasmic superoxide dismutase in meningococcal pathogenicity. Infect Immun. 1998;66:213–217. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.213-217.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]