Abstract

Neutrophils are the main inflammatory cell present in lesions involving the central nervous system (CNS) during human and murine listeriosis. In this study, administration of the neutrophil-depleting monoclonal antibody RB6-8C5 during experimental murine listeriosis facilitated the multiplication of Listeria monocytogenes in the CNS. These data suggest that neutrophils play a key role in eliminating bacteria that gain access to the CNS compartment. In addition, we provide evidence that their migration into the CNS may be necessary for the subsequent recruitment of macrophages and activated lymphocytes.

Experimental murine listeriosis has long served as a general model for the study of cellular immunity to intracellular bacteria (14) and as an animal model for human listeriosis (1, 3, 12, 14). The early stages of listeriosis are characterized by a rapid influx of neutrophils and macrophages into the liver and the spleen, which are the organs where listeriae are trapped during systemic infection (14). The role of neutrophils in the early resistance of mice to Listeria monocytogenes infection has been studied using the antigranulocyte monoclonal antibody (MAb) RB6-8C5. Administration of this MAb renders mice severely neutropenic for 2 to 3 days after inoculation (5, 16, 17). Neutrophils were found to play a critical role in reducing the bacterial burden in the liver and spleen during the first 3 days postinfection (PI) (2, 4–7, 11, 16, 17). Neutropenic mice die rapidly after inoculation with a sublethal dose of L. monocytogenes, due to massive bacterial multiplication in various organs, especially in the liver and spleen.

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is a common feature of human listeriosis that accounts for the high mortality rate and neurological sequelae reported to occur in infected human beings (10). Neutrophils are the main inflammatory cell present in histopathological sections from the CNS lesions (i.e., meningitis, ventriculitis and choroiditis, and rhombencephalitis) that can develop during the course of human or experimental murine listeriosis (1, 3, 10, 13, 15). However, the role of neutrophils in the development or prevention of these CNS lesions is not well understood. CNS involvement occurs late after infection and has been reported to be highly dependent on the level and duration of bacteremia (3). Bacteremia in turn is induced by rapid bacterial multiplication in the liver and the spleen (3). A rapid influx of neutrophils into the subarachnoid space, after the arrival of L. monocytogenes in the CNS compartment, has been reported. This polymorphonuclear leukocyte recruitment process has been related to the enhanced expression of adhesion molecules (i.e., P-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 [ICAM-1]) in subarachnoid venules (13). Recruited neutrophils are thought to contribute to the elimination of L. monocytogenes, although they also could be involved in the development of progressive brain injury via the release of harmful mediators.

To elucidate the role of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of CNS lesions during experimental murine listeriosis, we depleted mice of neutrophils at a time when they had already emigrated into the liver and spleen but before CNS lesions became evident. To do this, 8- to 12-week-old female CD1 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Indianapolis, Ind.) were inoculated subcutaneously in the lumbar zone with 109 CFU of viable L. monocytogenes strain EGD. At 60 or 84 h PI, mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of 250 μg of the RB6-8C5 MAb. Control mice were injected intraperitoneally with rat immunoglobulin G instead of the RB6-8C5 MAb. Wright-stained blood smears were prepared to verify neutrophil depletion. Groups of mice were killed by halothane overdose on days 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8 PI. Samples of liver, spleen, and brain tissue were removed, homogenized, and plated on blood agar to estimate viable bacterial counts. In addition, blood collected from the vena cava was also plated to detect bacteremia. For histopathological evaluation, organ samples were removed, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and processed by routine procedures. Bacterial counts were analyzed using one-way analyses of variance. Tukey's tests were used to establish post hoc differences among different treatments for each day PI.

As previously reported, administration of the RB6-8C5 MAb to L. monocytogenes-infected mice significantly increased bacterial counts in the liver and spleen (Table 1). Mice inoculated with this neutrophil-depleting antibody at 60 h PI were unable to eliminate the listeriae from their livers and spleens. Mice so treated died or were euthanized because of their morbidity between days 4 and 6 PI. Mice inoculated with the RB6-8C5 MAb at 84 h PI also exhibited higher bacterial counts in the spleen and liver than did control animals, although these mice seemed better able to control the infection, as reflected by their progressively decreased bacterial levels until the end of the experiment.

TABLE 1.

Effect of RB6-8C5 MAb administration on the L. monocytogenes bacterial count in the spleens, livers, and brains of infected mice

| Days after challenge | Time of MAb RB6-8C5 treatment (h PI)b | Mean log10 CFU of L. monocytogenes ± SEMa in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen | Liver | Brain | ||

| 2 | — | 7.23 ± 0.95 | 6.10 ± 1.12 | 2.32 ± 1.17 |

| 4 | — | 8.41 ± 0.11 | 8.75 ± 0.15 | 4.99 ± 0.46 |

| 60 | 8.91 ± 0.19 | 8.19 ± 0.11 | 6.20 ± 0.71 | |

| 5 | — | 6.76 ± 1.0 | 6.17 ± 1.08 | 2.93 ± 1.04 |

| 60 | 8.68 ± 0.07 | 8.51 ± 0.13 | 4.79 ± 0.23 | |

| 84 | 7.75 ± 0.70 | 7.65 ± 0.63 | 4.42 ± 2.22 | |

| 6 | — | 3.43 ± 0.32c | 0c | 0.62 ± 0.62c |

| 60 | 8.64 ± 0.26cd | 7.95 ± 0.05cd | 3.98 ± 0.02cd | |

| 84 | 6.01 ± 1.07 | 4.97 ± 0.74e | 1.37 ± 0.83 | |

Groups of mice were inoculated with the RB6-8C5 MAb at 60 or 84 h after subcutaneous infection with L. monocytogenes. There were four animals per group.

—, no MAb treatment.

Mean for three mice.

Value differs significantly (P < 0.05) from that for the control.

Value differs significantly (P < 0.05) from those for the control and the 60-h treatment group.

As previously reported (4, 6, 7, 16), histopathological evaluation of the liver sections of mice treated with the RB6-8C5 MAb at 60 h PI revealed large areas of bacterial replication within hepatocytes, without apparent inflammatory cell infiltration. Splenic lesions in these mice consisted of a necrotizing splenitis with a marked lymphoid depletion. Large numbers of listeriae could be seen mainly located under the splenic capsule, as well as around splenic blood vessels. These severe lesions persisted through the end of the experiment. Hepatic lesions in animals inoculated with the RB6-8C5 MAb at 84 h PI exhibited small areas of bacterial replication with foci of granulomatous inflammation. On day 5 PI two animals of this group had lesions consisting almost entirely of foci of heavily infected hepatocytes with a paucity of inflammatory cells. These mice displayed less severe pyogranulomatous splenic lesions than mice that received the RB6-8C5 MAb at 60 h PI.

Thus, in our experimental model, neutrophils seem to be essential for limiting listerial multiplication in the liver and the spleen during the first 4 days of experimental listeriosis. After day 4 PI, acquired resistance may be sufficient to allow RB6-8C5 MAb-treated mice to survive, although they are not as efficient as control mice in limiting bacterial growth. Two of eight mice inoculated with the RB6-8C5 MAb in the present study developed hepatic and splenic lesions with signs of uncontrolled bacterial growth. This finding suggests that these mice were unable to control the infection before administration of the neutrophil-depleting RB6-8C5 MAb. Efficiently reducing the listerial burden in the liver and the spleen during the first 4 days of infection is likely to be crucial for the development of a protective adaptive immune response.

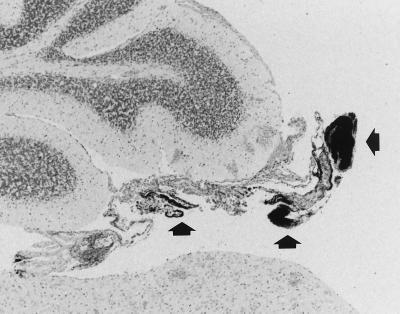

Bacteremia has been previously reported to be required for invasion of the CNS during experimental murine listeriosis (3). Bacteremia lasted through the end of the experiment (day 6 PI) in the RB6-8C5 MAb-treated groups (6.67 ± 0.85 and 2.88 ± 1.48 log10 CFU/ml, in the group depleted of neutrophils at 60 and 84 h PI respectively), whereas it was resolved after day 4 PI in the control group. Consistent with the prolonged bacteremia, CNS lesions were more numerous in the RB6-8C5 MAb-treated groups of mice. Of the mice inoculated with the RB6-8C5 MAb at 60 and 84 h PI, 55 and 50% respectively, had CNS lesions, compared to 16% of the controls. In addition to the increased frequency of CNS lesions in the RB6-8C5 MAb-treated mice, striking differences between the histopathological appearance of CNS lesions in RB6-8C5 MAb-treated mice and that of CNS lesions in control mice were also observed. Typical lesions in control mice consisted of pyogranulomatous meningitis with few intralesional bacteria. By contrast, two different lesional patterns were found in RB6-8C5 MAb-inoculated mice. Lesions observed at 36 h after RB6-8C5 MAb treatment consisted of large numbers of bacteria in the leptomeninges, with few inflammatory cells. Curiously, in all these cases, free listeriae were located mainly in the meningeal tissue of the choroid velum over the fourth ventricle (Fig. 1); the choroid plexus was not affected. In contrast to a recent report of large numbers of neutrophils associated with subarachnoid vessels in the hippocampal sulcus during experimental murine listeriosis (13), we observed only a few inflammatory cells, or listeriae, in the subarachnoid space in RB6-8C5 MAb-treated mice. On days 5 and 6 PI, two animals in each RB6-8C5 MAb-treated group had mild CNS lesions similar to those of control mice. These consisted of mild mononuclear meningitis without visible intralesional bacteria. Most of the inflammatory cells seen infiltrating the subarachnoid compartment of RB6-8C5 MAb-inoculated mice had the histological appearance of immature cells of the myelomonocytic lineage. These cells stained dimly positive by immunohistochemistry (data not shown) for the neutrophil differentiation antigen 7/4 (12). Because the RB6-8C5 MAb specifically binds to and depletes mature neutrophils (4), it is not surprising that immature cells of the myelomonocytic lineage were released from the bone marrow into the bloodstream. These immature cells would be expected to have less bactericidal capability, resulting in poorer control of bacterial growth in the subarachnoid space.

FIG. 1.

Large amounts of L. monocytogenes located in the meningeal tissue forming the choroid velum over the fourth ventricle 36 h after RB6-8C5 MAb treatment (arrowheads). The sample was Gram stained. Magnification, ×42.5 (original magnification, ×50).

An unexpected result of our study was that large numbers of listeriae were recovered from the brains of RB6-8C5 MAb-treated mice on day 4 PI, without any evidence of CNS lesions. We suggest that this reflects a greater level of bacteremia, resulting from the inability of RB6-8C5 MAb-treated mice to restrict listerial multiplication in the livers and the spleens and their impaired ability to clear listeriae once they reached the CNS. Intracellular listeriae were observed within circulating macrophages in blood smears from all the treatment groups. Furthermore, and as previously reported (9), listeriae were occasionally observed within circulating neutrophils in blood smears from control animals. Although L. monocytogenes can gain access to the CNS compartment within phagocytic cells (3, 8, 9, 15), in vitro studies have also shown that L. monocytogenes can invade and multiply within microvascular endothelial cells (18). We speculate that the depletion of blood neutrophils in RB6-8C5 MAb-treated mice allowed more listeriae to circulate freely in the bloodstream, perhaps facilitating endothelial invasion and multiplication within the brain compartment, leading in turn to lesion development.

The significance of our observation of large numbers of extracellular gram-positive rods in the roof of the fourth ventricle is unknown. The concomitant presence of inflammatory cells in the subarachnoid space, rather than at the site where most of the listeriae were present, suggests that L. monocytogenes and inflammatory cells may utilize different mechanisms to reach the CNS. Some of us recently reported that the arrival of inflammatory cells in the subarachnoid space is related to the increased expression of P-selectin and ICAM-1 in subarachnoid vessels, especially those located in the hippocampal sulcus (13). In the present study, we observed no significant difference in the endothelial expression of P-selectin and ICAM-1 by RB6-8C5 MAb-treated mice, compared to that of control mice (data not shown). In the absence of neutrophils, other inflammatory cells, with the exception of a few immature myelomonocytic cells, were not detected in the subarachnoid space. This finding suggests that the migration of neutrophils into the brain is a prerequisite for the subsequent recruitment of macrophages and activated lymphocytes. Deficient macrophage recruitment to other organs during experimental murine listeriosis in neutrophil-depleted mice has been reported previously (4, 5, 16).

In conclusion, the administration of the neutrophil-depleting RB6-8C5 MAb during experimental murine listeriosis enhanced the multiplication of L. monocytogenes and lesion formation in the CNS of infected mice. These data indicate that neutrophils are crucial for preventing the access or multiplication of L. monocytogenes in the CNS compartment. Furthermore, the initial emigration of neutrophils into the CNS may be necessary for the subsequent recruitment of macrophages and activated lymphocytes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Comisión Interdepartamental de Ciencia y Tecnología (CICYT), AGF93-C02-02, and by funds from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the School of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Wisconsin—Madison.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altimira J, Prats N, López S, Domingo M, Briones V, Dominguez L, Marco A. Repeated oral dosing with Listeria monocytogenes in mice as a model of central nervous system listeriosis in man. J Comp Pathol. 1999;121:117–125. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.1999.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelberg R, Castro A J, Silva M T. Neutrophils as effector cells of T-cell-mediated, acquired immunity in murine listeriosis. Immunology. 1994;83:302–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berche P. Bacteremia is required for invasion of the murine central nervous system by Listeria monocytogenes. Microb Pathog. 1995;18:323–336. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1995.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conlan J W, North R J. Neutrophils are essential for early anti-Listeria defense in the liver, but not in the spleen or peritoneal cavity, as revealed by a granulocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1994;179:259–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conlan J W. Critical roles of neutrophils in host defense against experimental systemic infections of mice by Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella typhimurium, and Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun. 1997;65:630–635. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.630-635.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czuprynski C J, Brown J F, Wagner R D, Steinberg H. Administration of antigranulocyte monoclonal antibody RB6-8C5 prevents expression of acquired resistance to Listeria monocytogenes infection in previously immunized mice. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5161–5163. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5161-5163.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czuprynski C J, Theisen C, Brown J F. Treatment with the antigranulocyte monoclonal antibody RB6-8C5 impairs resistance of mice to gastrointestinal infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3946–3949. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3946-3949.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drevets D A, Sawyer R T, Potter T A, Campbell P A. Listeria monocytogenes infects human endothelial cells by two distinct mechanisms. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4268–4276. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4268-4276.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drevets D A. Dissemination of Listeria monocytogenes by infected phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3512–3517. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3512-3517.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farber J M, Peterkin P I. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:476–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregory S H, Sagnimeni A J, Wing E J. Bacteria in the bloodstream are trapped in the liver and killed by immigrating neutrophils. J Immunol. 1996;157:2514–2520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsch S, Gordon S. Polymorphic expression of a neutrophil differentiation antigen revealed by monoclonal antibody 7/4. Immunogenetics. 1983;18:229–239. doi: 10.1007/BF00952962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.López S, Prats N, Marco A J. Expression of E-selectin, P-selectin, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 during experimental murine listeriosis. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1391–1397. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65241-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackaness G B. Cellular resistance to infection. J Exp Med. 1962;116:381–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prats N, Briones V, Blanco M, Altimira J, Ramos J A, Dominguez L, Marco A. Choroiditis and meningitis in experimental murine infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:744–777. doi: 10.1007/BF01989983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rakhmilevich A L. Neutrophils are essential for resolution of primary and secondary infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:827–831. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers H W, Unanue E R. Neutrophils are involved in acute, nonspecific resistance to Listeria monocytogenes in mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5090–5096. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5090-5096.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson S L, Drevets D A. Listeria monocytogenes infection and activation of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1658–1666. doi: 10.1086/314490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]