Abstract

While lung cancer risk among smokers is dependent on smoking dose, it remains unknown if this increased risk reflects an increased rate of somatic mutation accumulation in normal lung cells. Here we applied single-cell whole genome sequencing of proximal bronchial basal cells from 33 subjects aged between 11 and 86 years with smoking histories varying from never smoking to 116 pack years. We found an increase in the frequency of single-nucleotide variants and small insertions and deletions with chronological age in never-smokers with mutation frequencies significantly elevated among smokers. When plotted against smoking pack-years, mutations followed the linear increase in cancer risk only until about 23 pack years, after which no further increase in mutation frequency was observed, pointing towards individual selection for mutation avoidance. Known lung cancer-defined mutation signatures tracked with both age and smoking. No significant enrichment for somatic mutations in lung cancer driver genes was observed.

Lung cancer as the leading cause of all-cancer mortality has been strongly linked to cigarette smoking 1–4. Chemical carcinogens in cigarette smoke, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), elicit DNA damage resulting in cancer-causing mutations 5–7.

Epidemiological studies have estimated the risk of lung cancer with total lifetime smoking dose, duration, intensity, and timing of cessation 1. It has been reported that 70% of smoking-related mortality occurs among those of advanced age, with 80–90% of lifelong smokers never developing lung cancers 8,9. Interpreting these observations from population cohorts in terms of the molecular and genetic mechanisms is essential, but largely limited by the lack of comprehensive molecular risk assessment, including molecular evaluation for early carcinogenesis.

While tumor cells from lung cancers from smokers typically contain tens of thousands of somatic mutations inherited from the stem/progenitor cells and accumulated during tumor progression 6,10–12, the landscape of somatic mutations in normal human proximal bronchial basal cells (PBBCs), the leading candidate progenitor cell for squamous cell carcinoma based on airway topography and cell markers 13–16, has rarely been studied. The main challenge in such studies is the random and sparse nature of somatic mutations, which are different from cell to cell. To identify somatic mutations and accurately estimate their frequency in normal tissues, single-cell whole-genome sequencing is necessary, because each single cell acquires its unique set of somatic mutations during the lifetime. In a recent study, mutation burden was quantified in normal bronchial epithelium by culturing single cells into clones, which were then subjected to whole genome sequencing and mutation identification using conventional sequencing and variant calling approaches. Analysis of 16 individuals revealed compound effects of cigarette smoking and aging on the mutation frequency 17. However, to quantitatively evaluate the effects of both aging and smoking dose on the mutation burden, systematic analysis of a larger cohort comprised of both never-smokers of varying ages and smokers with a wide range of different lifetime smoking doses is needed.

Recently we and others developed accurate methods for the quantitative, genome-wide analysis of mutations in single cells 18–20. This avoids long-term clonal expansion, which is time-consuming and may introduce additional mutations. Here, we utilized this method to generate single-cell, genome-wide somatic mutation profiles of normal human bronchial epithelia from 14 never-smokers at the age range of 11 to 86 years (yrs.) and 19 smokers of 44 to 81 yrs. Thus, we were able to quantitatively analyze mutational burden in single bronchial epithelial cells arising from progressive age and lifetime exposure to tobacco smoke to dissect the respective effects of these two key carcinogenesis factors.

Results

Mutation frequencies and spectra in single nuclei

To characterize mutation profiles, PBBCs were obtained from a total of 31 subjects in the course of bronchoscopy procedures, typically performed for lung nodule evaluation (e.g., possibility of cancer), for concern over opportunistic/exotic infections, or for exploring structural anomalies, and other clinical indications. The subjects included 12 adults without smoking history (‘never-smokers’), 19 smokers, including 7 former smokers and 12 current smokers. To extend the cohort for studying the effect of age we commercially obtained two additional PBBC samples from 2 teenage donors (Lonza). Of the 19 smokers, 14 were diagnosed with lung cancers, while only 1 never-smoker was a lung-cancer patient. Samples of airway epithelium were obtained from brushings of main lobar bronchi by fiberoptic bronchoscopy and subjected to short-term propagation in culture for 3–4 weeks for growth selection of PBBCs and were then snap-frozen at −80°C. A subset of 14 uncultured samples from lung cancer case and cancer-free subjects were evaluated by cytomorphology, to assure there were no overtly malignant cells in the initial samples. For each subject, nuclei were isolated from the frozen PBBC pellets and mutation frequencies and spectra determined for 3–8 individual nuclei as described previously for single cells 18,20. Among all sequenced nuclei, 26.6 ± 9.3 % of the genome was surveyed at a depth of ≥20× with a sensitivity for single nucleotide variants (SNVs) of 0.68 ± 0.12 and small insertions and deletions (INDELs) of 0.40± 0.07, respectively (Methods, Supplementary Table 2). The entire procedure is schematically depicted in Figure 1a (see also Methods).

Fig. 1 |. Mutation accumulation in PBBCs with age in never-smokers.

a, Schematic representation of the isolation, processing and analysis of PBBCs from human lung. b-c, SNV and INDEL frequency of never-smokers versus age. Each data point indicates the mutation frequency per nucleus from each individual. d-e, SNV and INDEL frequency from never-smokers (n=14) versus age. Each data point indicates the median value and the minimal and maximal range of mutation frequency of 3–5 nuclei from each individual. P values were obtained by likelihood ratio tests using negative binomial mixed effect models.

Age-related accumulation of mutations in PBBCs in never-smokers

To investigate mutation frequency in PBBCs as a function of age, somatic mutations including SNVs and INDELs were quantitatively analyzed in single PBBC nuclei from the never-smokers and corrected for genome coverage and sensitivity (Figure 1b–c, Extended Data Figure 1). The median number of SNVs per nucleus in the subjects was found to vary between 464 ± 108 (11 yrs.) and 2739 ± 778 (86 yrs), which roughly corresponds to a rate of 28 mutations per cell per year (P = 3.9 × 10−3, generalized linear mixed-effect model, GLME; Figure 1d). Although lacking statistical significance, median number of INDELs per nucleus in the subjects was also found to increase with age, from 59 ± 18 (11 yrs.) to 304 ± 94 (86 yrs.), which corresponds to approximately 2 INDELs per cell per year (P = 0.28, GLME; Figure 1e). Of note, the median number of SNVs per nucleus in PBBCs from the youngest donor was in the same range as we previously reported for young subjects in B lymphocytes 20 or liver hepatocytes 18. However, during aging, the rate of mutation accumulation in PBBCs was approximately half of that in hepatocytes, and roughly similar to what has been observed for human B lymphocytes 20.

Mutation frequency in PBBCs of smokers

Next, we studied mutation accumulation with age in PBBCs of smokers. Figure 2a and b show the median numbers of SNVs and INDELS per nucleus, respectively, in smokers and non-smokers. Similar to never-smokers, mutation frequencies in cells from smokers increased with age, albeit at a significantly higher rate, estimated as 91 SNVs per cell per year (P = 3.5 × 10−2, GLME), an excess of 63 SNVs per cell per year over never-smokers (P=2.1 × 10−2, GLME, Figure2a). For INDELS, a significant increase with age was observed among all subjects (P = 4.8× 10−2, GLME). However, the higher INDEL frequency in smokers of 44 to 81 years as compared to never-smokers of the same age was not statistically significant (P = 0.51) (Figure 2b).

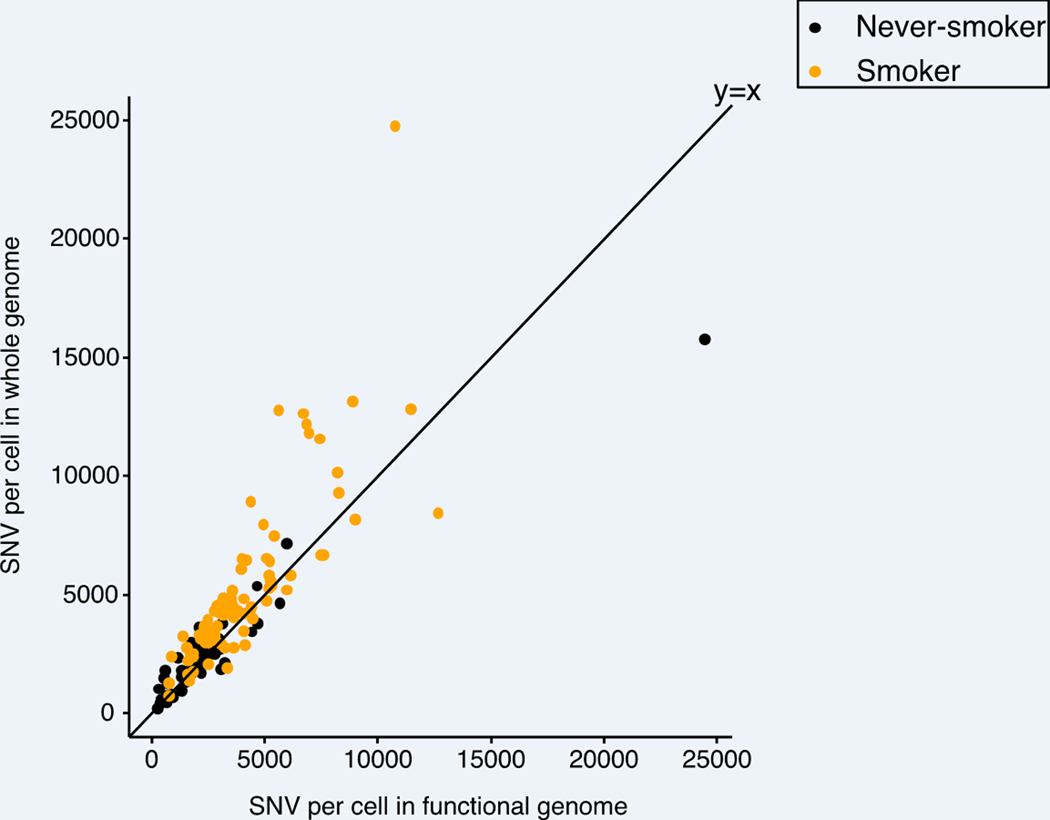

Fig. 2 |. Mutation accumulation in PBBCs of smokers.

a-b, Elevated SNV (INDEL) frequency in relation to age among smokers (n=19). Each data point indicates the median value and the minimal and maximal range of mutation frequency of 3–8 nuclei per subject. P values were obtained by a likelihood ratio tests using negative binomial mixed effect models. c, SNV frequency versus smoking pack-years across all individuals (n=33). Each data point indicates the median value and the minimal and maximal range of mutation frequency of 3–8 nuclei per subject. Subject 1320 with its high clonality of mutations is marked and gray dash line indicates the change point of piece-wise linear regression without including 1320. d, SNV frequency of different groups of individuals according to the smoking pack-years, with boxes indicating median values and interquartile ranges of the never (n=14), light (n=6), moderate (n=6), and heavy (n=7) smoking group, respectively. e, SNV frequency in the functional genome and genome overall of transcribed lung exome based on human lung dataset of GTEx 28,29. Each data point represents the median number of SNVs per subject in the functional genome (x axis) and whole genome (y axis) of never-smokers (orange) and smokers (black).

To gain better insight into the relationship between smoking and mutational burden we analyzed mutation frequency in normal PBBCs as a function of cumulative smoking dose, i.e., self-reported pack-years defined as twenty cigarettes smoked each day for one year 21–23. Figure 2c and d show the median mutation frequencies per nucleus for the different subjects.

Among the data points one outlier is obvious, with all 6 nuclei from this subject showing a very high number of mutations, i.e., 12437 ± 602 SNVs per cell. This subject was a light smoker (6 pack-years) at the age of 81 and also a newly diagnosed, untreated cancer patient (Subject ID 1320). All 6 nuclei of this subject were found to share multiple mutations, in contrast to all other subjects (Extended Data Figure 2a). Further analysis of mutations in these 6 nuclei revealed that among 1950 SNVs called in at least one cell, with the same position also surveyed in all other cells (minimum position coverage ≥5× and without filtering for allelic bias; see also Methods), 1433 were shared between at least two nuclei and 1090 were shared between at least 5 nuclei and 39 SNVs were shared between all 6 nuclei sequenced for this subject (Extended Data Figure 2b).

These shared SNVs between four nuclei (at ≥20× depth and after filtering for allelic bias) included mutations in the DNA repair gene encodes polynucleotide kinase-phosphatase (PNKP) 24, as well as in reported cancer driver genes MYCN, FGD5, CACNA1D, FAT3 (Supplementary Table 4) 25. These observations in this outlier individual, all in cytologically normal basal cells, strongly suggest that these cells originated from a single clone, potentially premalignant, possessing both an inherent susceptibility to mutations and advantageous growth characteristics due to mutations in cancer driver genes.

To model the mutation frequency as a function of pack years, we used a negative binomial mixed effect model with or without the outlier subject 1320 (see Methods). Without the outlier, the mutation frequency increased linearly up to 23 pack-years (95% CI:10–51 pack-years), then remained constant. This was statistically significant against the null model (P = 4.5 × 10−3) and against the linear model with no change point (P = 4.1 × 10−3), while the linear model showed no statistical significance against the null model (P = 0.11), in agreement with the non-linear effect of pack-years in the analysis implemented with an order-4 (i.e. cubic) B-spline fit (Figure 2c, Extended Data Figure 3, see also Methods). When the outlier subject was included, the non-linear increase of mutation frequency was essentially the same, but our statistical model lacked the power to determine the switch point precisely at 23 pack years. Irrespective, the results clearly show that mutation frequencies in PBBCs of heavy smokers (>60 pack years) was not higher than in moderate (20.1–60 pack years) smokers (P = 0.11, GLME) 26 (Figure 2d). Applying the same approach to the INDELs, we found the same change point at 23 pack-years, but no statistical significance when compared to the null model (P=0.74) (Extended Data Figure 4a–b). This loss of a dose response relationship in the heavier smokers was surprising and seems to suggest that accumulating mutations alone cannot entirely explain the increased lung cancer risk as a function of pack years. We also examined a possible effect of smoking cessation (quit years) on mutation frequency, in addition to the effect of age and pack-years, but within study power limits found no statistically significant effect on either SNV (P = 0.22, GLME) or INDEL (P = 0.76, GLME) frequencies (Extended Data Figure 5a–b).

To determine the potential functional impact of smoking-associated mutations we compared the rate of mutation accumulation in the functional genome of smokers with that in the genome overall. The functional lung genome was defined as the transcribed lung exome 27–29 plus its gene regulatory sequences, i.e., open chromatin regions 30. We found that both age- and smoking-related mutations accumulated more slowly in the functional genome than in the non-functional genome (P = 1.09 × 10−39, GLME) (Figure 2e), (Extended Data Figure 6). This finding can be explained by enhanced genome surveillance and more effective DNA repair in the functional parts of the genome 31.

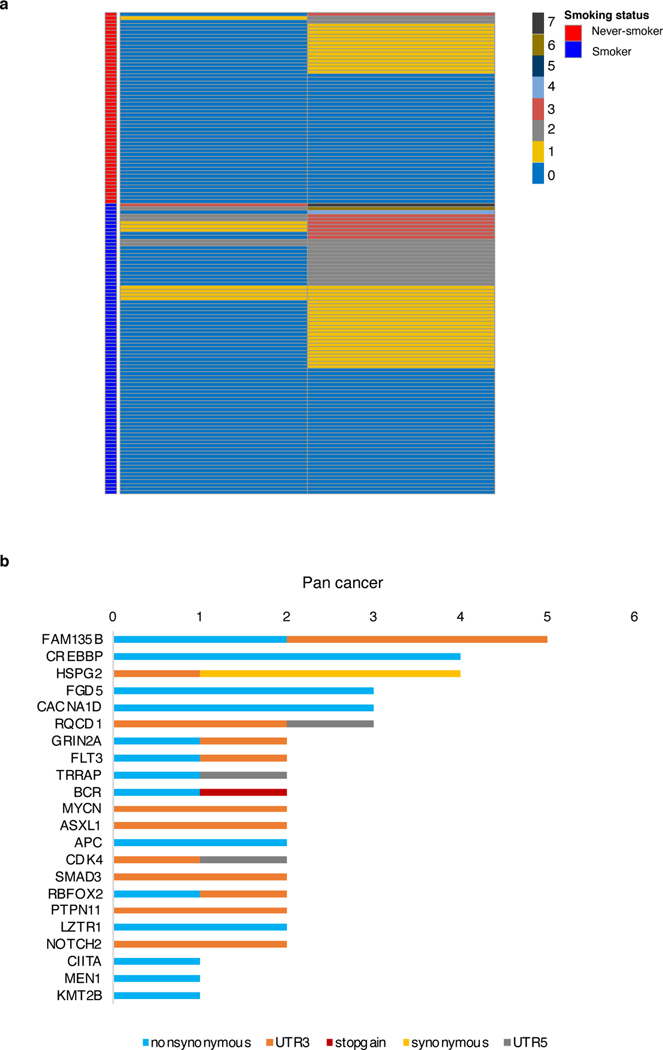

Mutations in cancer driver genes

While somatic mutations are generally random they can be amplified based on a selective advantage to their host cell, a process amply documented for cancer but also described for other diseases, such as COPD 32. Hence, we analyzed our data set for somatic mutations in known lung cancer and pan-cancer driver genes 25. Among all the 100,656 observed somatic mutations in nuclei from both smokers and non-smokers, including the 6 outlier nuclei, 21 mutations were in lung cancer driver genes occurring in 11% of nuclei and 111 occurring in 50% of all nuclei, in pan-cancer driver genes (Figure 3a and Extended Data Figure 7a–b and Supplementary note and Supplementary Table 5). However, permutation tests with random sets of genes demonstrated that there is no statistically significant enrichment for mutations in lung cancer (P = 0.73) or pan-cancer (P = 0.81) driver genes (Figure 3b). Hence, while as mentioned above, in the 6 outlier cells, shared mutations in cancer driver genes suggest clonal selection for a growth advantage, no evidence for such selection is observed for any of the other nuclei, either from smokers or non-smokers.

Fig. 3 |. Cancer driver mutations in normal PBBC nuclei.

a, Total number of nuclei with mutations and number of unique mutations in lung cancer driver genes across the sample set (n = 134). b, Mutation frequency in cancer driver genes and randomly chosen genes of the same size. Red diamonds indicate the genome coverage normalized mutation frequency of driver genes with the cancer set indicated above. Boxes indicate median values and interquartile ranges of mutation rate results of a randomly selected identical number of genes for corresponding cancer driver gene set for 200 repeats (n=200).

Mutation signatures

Next, we analyzed our data set for somatic mutational signatures associated with aging or smoking (see Methods). Analysis of the Single Base Substitution (SBS) signatures found in PBBCs of smokers revealed the presence of SBS4, which was virtually absent from never smokers (Figure 4a). SBS4 has previously been demonstrated as the predominant signature in lung tumors from smokers (3, 5, 8). Although the number of mutations attributed to SBS4 was significantly higher in smokers (P = 6.7 × 10−19, by Linear mixed effect models, LME) (Figure 4b), it was not correlated with age (P = 0.40, LME). Mutations attributed to SBS5 were found to significantly correlate with smoking status (P = 2.2 ×10−2, LME), but showed a much stronger correlation with chronological age (P = 4.1 × 10−6, LME) (Figure 4c). The other 14 signatures extracted from all subjects, smokers and never-smokers are associated with various molecular mechanisms (Figure 4a, Extended Data Figure 8a–f and Supplementary note).

Fig. 4 |. Mutational signatures and smoking.

a, (Left) Mutation spectra of single nuclei from never-smokers and smokers and (Right) stacked bar plot showing the proportional contribution of mutational signatures to SNVs across all nuclei measured from never-smokers and smokers, extracted using a hierarchical Dirichlet process (HDP). b, Median number of SNVs attributed to SBS4 signatures versus the age of individuals. Each data point indicates the median value and the minimal and maximal range of 3–8 nuclei from each individual attributed to SBS4 colored by smoking status. P values were obtained by likelihood ratio tests using linear mixed effect models (see Methods). c, Median number of SNVs attributed to SBS5 signatures versus the age of the individuals. Each data point indicates the median value and the minimal and maximal range of 3–8 nuclei from each individual attributed to SBS5 colored by smoking status. P values were obtained by likelihood ratio tests using linear mixed effect models (see Methods).

Signatures of INDELs matched those extracted from lung cancers or normal lung cells from smokers 17,33, as well as those generated in vitro by exposure of cells to PAHs 5,17. INDELs in smokers were particularly enriched for ID3, an INDEL signature of single-base deletions of cytosines (guanines) related to smoking among lung cancer tissues (Extended Data Figure 9a–b and Supplementary figure 4). These findings indicate that the molecular mechanisms of aging- and smoking-associated mutagenesis in normal tissues are similar to that in tumors. This is not surprising since tumors have been used as surrogates for the mutation spectra in the normal cells from which they originated.

Germline susceptibility

Susceptibility to lung cancer has been associated with germline genetic variation 34–38. To evaluate the possible effects of genetic background on mutagenesis in PBBCs we tested all studied subjects for the presence of germline variants previously associated with solid cancers and listed in the Clinvar database 39. Out of 31 subjects, 16 were diagnosed with cancer (14 diagnosed with lung cancer, 1 with prostate cancer, 1 with breast cancer). We also found a total of 17 carrying at least one of six identified genetic variants associated with risk of solid cancers (lung, breast, colon, sarcoma, lymphoma, prostate cancers). Among these 17 subjects, 13 were diagnosed with cancer (11 lung cancer, 1 prostate and 1 breast cancer). This enrichment of risk variants in cancer cases was statistically significant (P = 0.00156, Fisher exact test, two-sided) (Extended Data Figure 10 and Supplementary Table 7). Interestingly, two carriers (smokers) of cancer relevant polymorphisms in AKR1C2 (encoding aldo/keto reductase) critical for the detoxification of PAHs 40–42 demonstrated a more than 2-fold increase of the SBS4 signature fraction in their mutational burden (P = 2.2 × 10−16, Grubbs’s test) (Supplementary Table 6). This suggests a possible role of AKR1C2 variant in compromising detoxification of tobacco smoke in carriers, increasing susceptibility to smoking-induced mutagenicity.

Discussion

Cancer risk increases exponentially with age, likely as a consequence of the accumulation of mutations in somatic cells that subsequently become subject to rounds of selection and further mutation 43–45. The increased risk of lung cancers and various other cancers in smokers would then logically follow from an enhanced rate of somatic mutations due to the known mutagenic compounds in cigarette smoke 46. While mutation frequency has been found higher in lung tumors as compared to most other tumors, which likely reflects the mutation burden of the lung cell that gave rise to the tumor, increased mutations in normal human lung of smokers and non-smokers as a function of age has never been demonstrated. This is due to the difficulty of measuring somatic mutations in normal cells, which requires a single-cell approach 47. In this paper we present a single-cell analysis of somatic mutation in human lung cells as a function of both age and smoking status.

To avoid the chance of inadvertently including contaminating tumor cells with normal PBBCs we sampled only cytologically normal human PBBCs taken from a contralateral site during bronchial brushing, distant from the tumor of lung cancer case subjects. Additionally, our direct single-cell approach after only brief culture avoids such inadvertent contamination, and mutations introduced during long-term sub-culture 48. Hence, our current data on somatic mutation frequency solely interrogates cytologically normal human bronchial cells. Importantly, our cohort comprised 33 subjects for somatic mutation analysis, i.e., 14 never-smokers from teenagers to 86 years and 19 smokers with varying smoking dose from 5.6 to 116 pack-years. The results unequivocally demonstrate that mutations in human lung accumulate with age with higher levels in PBBCs of smokers.

In contrast to the only previous study in which mutations were studied in normal human lung from smokers 17, we did not observe a statistically significant selection for mutations in cancer driver genes such as Notch1, which are often found in lung cancer cells 17,49, either in non-smokers or smokers. This is not unexpected, since mutations are random and with only 3–8 nuclei per individual analyzed only mutations subjected to extensive clonal expansion could have been detected. Indeed, the extensive overlap between mutations found uniquely in outlier subject 1320 underscores the rarity of such selection. Among the 6 sequenced nuclei from this subject, shared mutations were found to occur in cancer driver genes. Of course, additional mutations in cancer driver genes might well be present and could possibly be detected by ultra-high-depth sequencing of bulk DNA, as has been demonstrated 50,51.

Interestingly, PBBCs of this same subject 1320 were also found to bear a very high mutation burden (i.e., 12437 ± 602 SNVs per cell). This could be due to minor defects in genes involved in genome maintenance, with a shared mutation in the DNA repair gene encoding polynucleotide kinase-phosphatase (PNKP) a possible candidate.

The most interesting finding in our study may be the observation that the dose dependency of the mutation frequency in smokers levels off around 23 pack-years, with mutational burdens in heavy smokers not significantly different from those in much lighter smokers. This phenomenon is not related to cancer incidence because mutation frequency in subjects with cancer was not significantly different from those who were cancer-free. It is tempting to explain this result from an increased resilience of some individuals to mutation induction, for example, through more accurate or robust DNA repair or replication. While there is evidence that DNA repair activities varies among normal individuals, which could be related to differences in cancer risk 52, no such evidence is as yet available for DNA repair accuracy, i.e., the capacity to repair damage at minimal mutation burden.

Alternatively, it is possible that increased resilience to mutation accumulation is caused by individual variation in detoxification of mutagenic compounds in tobacco smoke. This would affect the amount of DNA damage that can give rise to mutations through error-prone repair or replication. We did indeed find two carriers of polymorphisms in AKR1C2 critical for the detoxification of PAHs, which demonstrated a more than 2-fold increase of the SBS4 signature fraction in their mutational burden.

Single-cell somatic mutation analysis of human lung in smokers and non-smokers across a wide age range confirms the model that smoking increases lung cancer risk by increasing the frequency of somatic mutations, as hypothesized but never experimentally confirmed. Importantly, our results provide a possible explanation as to why most smokers never get lung cancer. Indeed, our observation of mutation frequencies leveling off in heavy smokers strongly suggests intrinsic factors to attenuate lung cancer risk by reducing mutations, for example by increasing DNA repair accuracy or reducing DNA damage by optimizing detoxification of tobacco smoke. This study provides a rational basis to further evaluate the nature of these intrinsic lung cancer risk factors that modulate mutation susceptibility of normal bronchial cells.

Methods

Data reporting.

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications 17–19. The experiments were randomized and the investigators were blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Subjects.

The 31 clinical subjects were recruited at Montefiore Medical Center among those individuals undergoing bronchoscopy for clinical purposes. Bronchoscopy was typically performed for lung nodule evaluation (e.g., possibility of cancer), for concern over opportunistic/exotic infections, or for exploring structural anomalies, and other clinical indications. By written informed consent, under protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee at Einstein-Montefiore, consenting subjects permitted pre-procedure interview, four additional research-directed bronchial brushings, and electronic medical record verification of clinical, imaging, and pathologic data. For the patients with carcinomas (squamous cell carcinomas or carcinoma in situ, as well as those with adenocarcinomas), a brush biopsy of normal bronchial tissue was taken from a contralateral site, distant from the tumor of clinical concern. Additionally, a representative sampling of 14 subjects revealed 12/14 with normal cytopathology, and 2/14 remaining subjects with mild atypia, per highly experienced, donor phenotype-blinded cytopathologist. There were no overt dysplastic or malignant cells in any of these 14 samples. Normal PBBCs of two healthy teenage subjects were obtained commercially from Lonza Walkersville Inc (Supplementary Table 1).

Isolation of PBBC single nuclei.

After fiberoptic bronchoscopy endobronchial brush biopsies were added to Airway Epithelial Cell Basal Medium supplemented with Bronchial Epithelial Cell Growth factors (BEGK, ATCC) for transportation to the lab. Biopsies were spun down, resuspended in 0.05% trypsin-EDTA and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. Cells were spun down and resuspended in BEGK, assessed the viability by trypan blue. PBBCs were cultured in BEGK with penicillin (10 units/ml)-streptomycin (10 μg/ml)-Amphotericin B (25 ng/ml) in 6-well plates at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The medium was replaced every other day. After reaching confluency, cells were transferred into T75 flasks and grown until 80% confluence. They were then trypsinized, spun down as pellet and stored in −80 °C for nuclei isolation.

Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (15 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 15 mM NaCl, 60 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 250 mM sucrose, 0.2% Igepal-CA630, 1 mM DTT, 1 × proteinase inhibitor) and incubated on ice for 5 min, spun down and washed twice with the lysis buffer described above without the detergent (Igepal-CA630). Nuclear pellets were suspended in PBS at room temperature for single nuclei collection. Single nuclei were collected using CellRaft arrays (Cell Microsystems, Durham, NC) as described previously 18,47, except that we used an automated system (CellRaft AIR System). Individual nuclei attached to the raft were collected into 0.2-ml PCR tubes containing 2.5 μl of PBS, then snap-frozen on dry ice and kept at −80°C until further use.

Single nuclei whole-genome amplification (WGA).

Single nuclei from each subject were subjected to WGA using the single-cell multiple displacement procedure (SCMDA) described previously 18,47. In parallel, 1 ng of human genomic DNA and DNA-free PBS solution, were processed as positive and negative controls, respectively. MDA products were purified using AMPureXP beads (Beckman Coulter) and quantified with the Qubit High Sensitivity dsDNA kit (Invitrogen Life Sciences). To verify sufficient and uniformly amplified single-nuclei MDA products, we performed the eight-target locus-dropout test as described previously 47. Samples with at least 6 out of 8 identified as been uniformly amplified in reference of control with template as genomic DNA 47 were further subjected to library preparation and WGS.

Genomic DNA extraction.

Human bulk genomic DNA was collected from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or PBBCs of the same subject using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA concentration was quantified using Qubit kit and DNA quality was evaluated as previously described 47.

Library preparation and WGS.

The sequencing libraries for Illumina platform were generated with NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England BioLabs) using 200–400 ng of DNA as an input. The libraries were sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq S4 sequencing platform to 30× coverage depth with 2×150 paired-end mode. Sequencing was outsourced to Novogene Inc.

Alignment for WGS.

Sequencing reads were aligned to the human reference genome as previously described 18. In brief, paired-end sequencing reads were trimmed to remove adapter and low-quality reads by Trim Galore (version 0.4.1) and then mapped to the human reference genome (GRCh37, including decoy contigs) using BWA(mem; version 0.7.10)53. PCR duplication were marked using Samtools (version 0.1.19) 54. Realignment of reads and recalibrations of base quality scores were performed using Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, version 3.5.0) 18,55.

Calling somatic SNVs and INDELs.

Somatic mutations were called using SCcaller (version 1.2; https://github.com/biosinodx/SCcaller) 47. The identification of mutation was based on presence of at least 4 reads containing the mutation in genome regions with at least at least 20 × and 30× sequencing depth for SNVs and INDELs, respectively. Potential amplification artifacts were filtered out based on assessment of allelic bias determined by heterozygous SNPs on autosomes identified as described 20. A variant quality score ≥25 was chosen as a minimal for INDEL calling. A somatic mutation was considered to be shared between two single nuclei from the same individual when it appeared in at least 1 read in the other single nucleus (minimum read depth ≥5× and mapping quality score≥20).

Estimating mutation frequencies.

The frequency of somatic SNVs / INDELs per nucleus was estimated with the normalization of genomic coverage and sensitivity.

The surveyed genome per single nucleus was calculated as the number of nucleotides with mapping quality ≥40 and coverage depth ≥20× for SNVs and ≥30× for INDELs which are also found in bulk. The sensitivity of de novo mutation calling in the single nuclei was estimated as the ratio of the number of heterozygous SNPs detected in single nuclei to the total number of heterozygous SNPs detected in bulk DNA, at a minimum sequencing depth of 20× in bulk and 20× and 30× in single cells for SNV and INDEL, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). For INDEL, we also required quality score of SNPs in single cells ≥25. The relative standard error of correction was calculated as

Annotation of functional genomes.

All identified mutations were annotated according to the gene definitions of GRCh37.87 as previously described 18. In brief, mutations found in the functional genome (transcribed genes, promoters, and open chromatin regions) were annotated by ANNOVAR 56. The open chromatin regions were defined by ENCODE transcription factor binding regions and ATAC sequencing data in lung tissue (experiment name: ENCSR647AOY) and determined by MACS2 18,30. ATAC sequencing reads were adapter- and low-quality-trimmed (Trim Galore, version 0.3.7), mapped to GRCh37 (Bowtie2, version 2.2.3; option: -X 2000), followed with the duplicated reads removal (Picard tool, version 1.119). The transcribed genes were defined as those with expression level ≥1 TPM from GTEx (https://gtexportal.org/) 28,29, or as an alternative by scRNA-seq in human lung basal cell in all samples 27.

Germline variant analysis.

Germline variants were identified as thouse with more than 4 variant-supporting reads at the depth >= 5x and GATK quality score >= 30. Filtering for germline SNVs (QD < 2.0, FS > 60.0, MQ < 40.0, MQRankSum < −12.5, ReadPosRankSum < −8.0, SOR > 3.0) and INDEL (QD < 2.0, FS > 200.0, ReadPosRankSum < −20.0, SOR > 10.0) was set as recommended by GATK. The list of clinically annotated variants was obtained from ClinVar (clinvar_20200923.vcf.gz, downloaded from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/ on 24 September 2020) 57.

Identifying mutation signatures.

Identified mutations in all subjects were pooled into two groups: Never-smoker and Smoker, and plotted with integrated spectra of 6 mutation types, respectively 58. Group-specific mutational signatures as well as identified de novo identified 4 signatures in PBBCs from each subject were extracted via hierarchical Dirichlet process (HDP, https://github.com/nicolaroberts/hdp). The identified signatures with ≥0.90 cosine similarity with reported signatures from version 3.0 of the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer COSMIC database (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/signatures/) 33,59 were considered as the same signatures. The identified SBS signatures were further fit in young (age <50 years old) and old (age >50 years old) never-smoker group using ‘fit_to_signatures_bootstrapped’ function with ‘regular’ method.

Analysis of cancer driver gene variants.

To test whether the difference between mutation frequency of cancer driver genes and other genes were statistically significant, we conducted a permutation test with resampling. We randomly selected list of genes equal in size to cancer driver gene set and calculated the mutation frequency. We repeated the resampling process 200 times and compared the obtained results to the mutation frequency in cancer driver genes. To search and identify mutated genes been under the positive selection in proximal bronchial basal cells, we applied the dN/dS method 60. We performed exome-wide dN/dS analysis and also analyzed global dN/dS ratios for driver genes reported in lung cancer and pan-cancers 25 using dNdScv (Supplementary Table 3). Genes with q value < 0.05 were reported as positively selected driver genes (Supplementary Table 4, 5).

Statistical methods.

We used a negative binomial random effect model to estimate the effects of age and smoking status on the somatic mutation frequency, with the number of observed mutations as the response, offsetting by the surveyed genome multiplying the sensitivity measure as described above, and the individual donor were treated as the random effects. The statistical significance was assessed using likelihood ratio tests. Negative binomial random effect model was estimated using function glmer.nb of R package lme4 61.

The change point model evaluating the presence of a threshold/plateau was evaluated under the same framework of negative binomial random effect model as described above, with age as a covariate. To find the optimal change point, we performed a grid search over pack-years between 10–116 with increment of 1, using the smallest deviance as the optimization criteria. The statistical significance between the optimal change-point model with the null model (with age effect only) was assessed by a likelihood ratio test with degree of freedom of two, reflecting the two extra parameters, slope before the change point and after the change points.

The effect of pack-years was also tested by incorporating an order-4 (i.e. cubic) B-spline of one knot into the negative binomial mixed effect model with age as a covariate, where the cubic spline is represented by a total of 5 linearly independent basis. The knot was placed in the middle of the interval of 0–116 pack-years. A likelihood ratio test was used to compare the B-spline model against the null model and the linear model with 4 and 3 degrees of freedom, respectively

To compare the mutation frequency in the functional genome with that of the non-functional genome, Poisson mixed effect model was used with the number of observed mutations as the response, offset by the size of surveyed genome multiplying the sensitivity, functional vs non-functional as the explanatory variable, and cells as the random effects.

Linear mixed effect models were used for analyzing the effect of smoking status and age on attributed mutation number of signatures SBS4 and SBS5, with log-transformation of SBS4 (SBS5) attributed mutation number are used as the response, with subjects as the random effects. The statistical significance of smoking and aging were obtained used likelihood ratio test comparing the model with both factors to the model with only one of the two.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability.

WGS data are available at dbGap (accession number: phs002758.v1.p1) and can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs002758.v1.p1. Somatic-mutation calls, including single-base substitutions and indels from all 134 samples have been deposited on SomaMutDB: http://vijglab.einsteinmed.org/static/vcf/lung_Huang.et.al.Naturegenetics.tar.gz.

Code availability.

Sequencing reads were filtered to remove adapter and low-quality reads by Trim Galore (version 0.4.1), mapped to the human reference genome (GRCh37, including decoy contigs) using BWA (mem; version 0.7.10), with PCR duplication removed by Samtools (version 0.1.19) Realignment of reads and recalibrations of base quality scores were performed by Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, version 3.5.0). Somatic mutations were called using SCcaller (version 1.2; https://github.com/biosinodx/SCcaller). MASS (version 7.3–53) and lme4 (1.1–26) was employed for statistical analysis in R (4.0.3 GUI 1,73 Catalina build 7892). Custom codes for statistical analysis, permutation analysis, are available through GitHub (https://github.com/Zhenqiu85/Lung_Smoke_analysis).

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Mutation frequency and correction deviation error.

SNV frequency of never-smokers versus age. Each data point indicates the mutation frequency per nucleus from each individual, with color intensity indicating relative standard error value (see Methods). The four cells of highest mutational burden were plotted separately with each data point representing median value with standard deviation errors.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Distribution of shared mutations in subject 1320.

a, Stacked bar plot showing the proportional contribution of shared SNVs between all sequenced 3–8 nuclei per subject. b, Upset plot showing the distribution of shared SNVs in six nuclei from subject 1320 (lower part). The bar chart (upper part) represents the number of SNVs shared by each nucleus combination.

Extended Data Fig. 3. An a prori semi-parametric B-spline model to test the non-linearity between mutation frequency and smoking pack-years.

Each data point indicates the SNV frequency of nuclei of individuals. The spline fit evaluated at the average age and the average of random effects, with the 95% confidence interval are shown by the gray line, with the piece-wise linear model fit as the blue line. P value for the spline model is 0.0043 compared to the linear model, and 0.0034 when compared to the null model (see Methods).

Extended Data Fig. 4. INDEL frequency and smoking dose.

a, INDEL frequency versus smoking pack-years across all individuals (n=33). Each dot indicates the median value and the minimal and maximal range of INDEL frequency of individuals. b, INDEL frequency of different group of individuals according to the smoking pack-years, with boxes indicating median number and interquartile range of the never (n=14), light (n=6), moderate (n=6), and heavy (n=7) smoking group, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Effects of smoking cessation on mutation frequency.

Median number of SNV and INDEL frequency among former smokers (n=7) and current smokers (n=12). a, each data point indicates the median value and the minimal and maximal range of SNV frequency of 3–8 nuclei per subject. b, each data point indicates the median value and the minimal and maximal range of INDEL frequency of 3–8 nuclei per subject. P values were obtained by likelihood ratio tests using negative binomial mixed effect model.

Extended Data Fig. 6. SNV frequency in the lung functional genome using scRNA-seq human lung data instead of GTEX.

Each data point represents the number of mutations per nucleus of in functional genome (x axis) and whole genome (y axis) of all subjects colored by smoking status.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Cancer driver mutations.

a, Distribution of driver gene mutations in single nuclei of subjects, with number of mutations and smoking status indicated by colors. b, Total number of single nuclei with unique mutations found in pan-cancer driver genes and number of unique mutations in pan-cancer driver genes across the sample set (n = 134), 22 of 85 driver genes shown (Supplementary Table 5).

Extended Data Fig. 8. Mutational signatures and smoking.

a, Mutation spectra of four novel signatures identified among never-smokers and smokers. The six substitution types are shown across the top. Within each substitution type, the trinucleotide context is shown as four sets of four bars, grouped by whether an A, C, G or T, respectively, is 5′ or 3′ to the mutated base. b-f, Absolute number of major signatures discovered from never-smokers (n=14) and smokers (n=19). Each dot indicates the median number of SNV frequency of each individual. Boxes indicate median values and interquartile ranges among each group. The quoted P values were obtained by likelihood ratio tests using linear mixed effect models. g, APOBEC signatures relative contribution versus SNV frequency of nuclei of never-smokers. Each data point represents a nucleus.

Extended Data Fig. 9. The INDEL mutation signature analysis.

a, Mutation spectra of INDEL in single nuclei from never-smokers (n=14) and smokers (n=19). The contributions of different types of INDELs are shown, grouped by whether variants are deletions or insertions; the size of the event; whether they occur at repeat units; and the sequence content of the INDEL. b, Stacked bar plot showing the proportional contribution of mutational signatures to INDELs across all nuclei (n=134) measured from never-smokers and smokers, four signatures (N1, ID1, ID3, ID4) were extracted by HDP.

Extended Data Fig. 10. Germline genetic variants associated with solid cancers.

A heat map showing 6 germline variants associated to solid cancers found in each subject per column, with the presence and absence colored. Variant IDs at the left of each row of the heatmap represent 6 different solid cancer associated single nucleotide polymorphisms found through Clinvar (Supplementary Table S7).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This study was supported by NIH grants U01 ES029519-01 (J.V., S.D.S), U01HL145560 (S.D.S, J.V.) AG017242 (J.V.) and AG056278 (J.V.). We thank A. Desai, D. Patel (Pulmonary Medicine) for bronchoscopy sample procurement; S. Khader for cytopathology; X. Hao for assisting with data analysis.

Footnotes

Competing interests

A.Y.M., X.D., and J.V. are cofounders of SingulOmics Corp. The remaining authors declare no other competing interests.

References:

- 1.Flanders WD, Lally CA, Zhu B-P, Henley SJ & Thun MJ Lung Cancer Mortality in Relation to Age, Duration of Smoking, and Daily Cigarette Consumption. Cancer Research 63(2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thurston SW, Liu G, Miller DP & Christiani DC Modeling lung cancer risk in case-control studies using a new dose metric of smoking. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention 14, 2296–2302 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberg AJ, Brock MV, Ford JG, Samet JM & Spivack SD Epidemiology of lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 143, e1S–e29S (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spivack SD, Fasco MJ, Walker VE & Kaminsky LS The molecular epidemiology of lung cancer. Crit Rev Toxicol 27, 319–65 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kucab JE et al. A Compendium of Mutational Signatures of Environmental Agents. Cell 177, 821–836.e16 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H. et al. Frequency of well-identified oncogenic driver mutations in lung adenocarcinoma of smokers varies with histological subtypes and graduated smoking dose. Lung Cancer 79, 8–13 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petljak M. et al. Characterizing Mutational Signatures in Human Cancer Cell Lines Reveals Episodic APOBEC Mutagenesis. Cell 176, 1282–1294.e20 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns DM Cigarette smoking among the elderly: Disease consequences and the benefits of cessation. Vol. 14 357–361 (American Journal of Health Promotion, 2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crispo A. et al. The cumulative risk of lung cancer among current, ex- and never-smokers in European men. British Journal of Cancer 91, 1280–1286 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexandrov LB et al. Mutational signatures associated with tobacco smoking in human cancer. Science (New York, N.Y.) 354, 618–622 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George J. et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature 524, 47–53 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imielinski M. et al. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell 150, 1107–1120 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaykhiev R. et al. Airway basal cells of healthy smokers express an embryonic stem cell signature relevant to lung cancer. Stem Cells 31, 1992–2002 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McQualter JL, Yuen K, Williams B. & Bertoncello I. Evidence of an epithelial stem/progenitor cell hierarchy in the adult mouse lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 1414–9 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukui T. et al. Lung adenocarcinoma subtypes based on expression of human airway basal cell genes. Eur Respir J 42, 1332–44 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rock JR et al. Basal cells as stem cells of the mouse trachea and human airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 12771–5 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods-only References:

- 17.Yoshida K. et al. Tobacco smoking and somatic mutations in human bronchial epithelium. Nature (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brazhnik K. et al. Single-cell analysis reveals different age-related somatic mutation profiles between stem and differentiated cells in human liver. Science Advances 6(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lodato MA et al. Aging and neurodegeneration are associated with increased mutations in single human neurons. Science 359, 555–559 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L. et al. Single-cell whole-genome sequencing reveals the functional landscape of somatic mutations in B lymphocytes across the human lifespan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116, 9014–9019 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Remen T, Pintos J, Abrahamowicz M. & Siemiatycki J. Risk of lung cancer in relation to various metrics of smoking history: A case-control study in Montreal 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services. BMC Cancer 18, 1–12 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siemiatycki J. Synthesizing the lifetime history of smoking. Vol. 14 2294–2295 (American Association for Cancer Research Inc., 2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas DC Invited Commentary: Is It Time to Retire the “Pack-Years” Variable? Maybe Not! American Journal of Epidemiology 179, 299–302 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jilani A. et al. Molecular cloning of the human gene, PNKP, encoding a polynucleotide kinase 3’-phosphatase and evidence for its role in repair of DNA strand breaks caused by oxidative damage. J Biol Chem 274, 24176–86 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martínez-Jiménez F. et al. A compendium of mutational cancer driver genes. 1–18 (Nature Research, 2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song K. et al. A quantitative method for assessing smoke associated molecular damage in lung cancers. Transl Lung Cancer Res 7, 439–449 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Travaglini KJ et al. A molecular cell atlas of the human lung from single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature 587, 619–625 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Consortium GT The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet 45, 580–5 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lonsdale J. et al. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Vol. 45 580–585 (Nat Genet, 2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerstein MB et al. Architecture of the human regulatory network derived from ENCODE data. Nature 489, 91–100 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martincorena I. & Campbell PJ Somatic mutation in cancer and normal cells. Science 349, 1483–9 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson GP & Bozinovski S. Acquired somatic mutations in the molecular pathogenesis of COPD. Trends Pharmacol Sci 24, 71–6 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexandrov LB et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature 578, 94–101 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broderick P. et al. Deciphering the impact of common genetic variation on lung cancer risk: a genome-wide association study. Cancer Res 69, 6633–41 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hung RJ et al. A susceptibility locus for lung cancer maps to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes on 15q25. Nature 452, 633–7 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiraishi K. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies two new susceptibility loci for lung adenocarcinoma in the Japanese population. Nat Genet 44, 900–3 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu C. et al. Genetic variants on chromosome 15q25 associated with lung cancer risk in Chinese populations. Cancer Res 69, 5065–72 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y. et al. Common 5p15.33 and 6p21.33 variants influence lung cancer risk. Nat Genet 40, 1407–9 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrison SM et al. Using ClinVar as a Resource to Support Variant Interpretation. Curr Protoc Hum Genet 89, 8 16 1–8 16 23 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rheinbay E. et al. Analyses of non-coding somatic drivers in 2,658 cancer whole genomes, PCAWG Drivers and Functional Interpretation Working Group 68, PCAWG Structural Variation Working Group. Nature 578, 67–67 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burczynski ME, Lin HK & Penning TM Isoform-specific induction of a human aldo-keto reductase by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), electrophiles, and oxidative stress: implications for the alternative pathway of PAH activation catalyzed by human dihydrodiol dehydrogenase. Cancer Res 59, 607–14 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fluck CE et al. Why boys will be boys: two pathways of fetal testicular androgen biosynthesis are needed for male sexual differentiation. Am J Hum Genet 89, 201–18 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nowell PC The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science 194, 23–28 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vijg J. Somatic mutations, genome mosaicism, cancer and aging. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development 26, 141–149 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rozhok AI & DeGregori J. The evolution of lifespan and age-dependent cancer risk. Trends Cancer 2, 552–560 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Obe G, Vogt WDH, H J. Mutagenic Activity of Cigarette Smoke, 223–246 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg., 1984). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dong X. et al. Accurate identification of single-nucleotide variants in whole-genome-amplified single cells. Nature Methods 14, 491–493 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blokzijl F. et al. Tissue-specific mutation accumulation in human adult stem cells during life. Nature 538, 260–264 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westhoff B. et al. Alterations of the Notch pathway in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 22293–8 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martincorena I. et al. Tumor evolution. High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science 348, 880–6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martincorena I. et al. Somatic mutant clones colonize the human esophagus with age. Science 362, 911–917 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nagel ZD, Chaim IA & Samson LD Inter-individual variation in DNA repair capacity: a need for multi-pathway functional assays to promote translational DNA repair research. DNA Repair (Amst) 19, 199–213 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li H. & Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. 25, 1754–1760 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McKenna A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang K, Li M. & Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 38, e164 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wright CF et al. Evaluating variants classified as pathogenic in ClinVar in the DDD Study. Genet Med 23, 571–575 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blokzijl F, Janssen R, van Boxtel R. & Cuppen E. MutationalPatterns: Comprehensive genome-wide analysis of mutational processes. Genome Medicine 10(2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bamford S. et al. The COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) database and website. British journal of cancer 91, 355–8 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martincorena I, Raine KM, Davies H, Stratton MR & Campbell PJ Universal Patterns of Selection in Cancer and Somatic Tissues. Cell 171, 1029–1041.e21 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bates D, M M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67, 1–48 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

WGS data are available at dbGap (accession number: phs002758.v1.p1) and can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs002758.v1.p1. Somatic-mutation calls, including single-base substitutions and indels from all 134 samples have been deposited on SomaMutDB: http://vijglab.einsteinmed.org/static/vcf/lung_Huang.et.al.Naturegenetics.tar.gz.