Abstract

Background

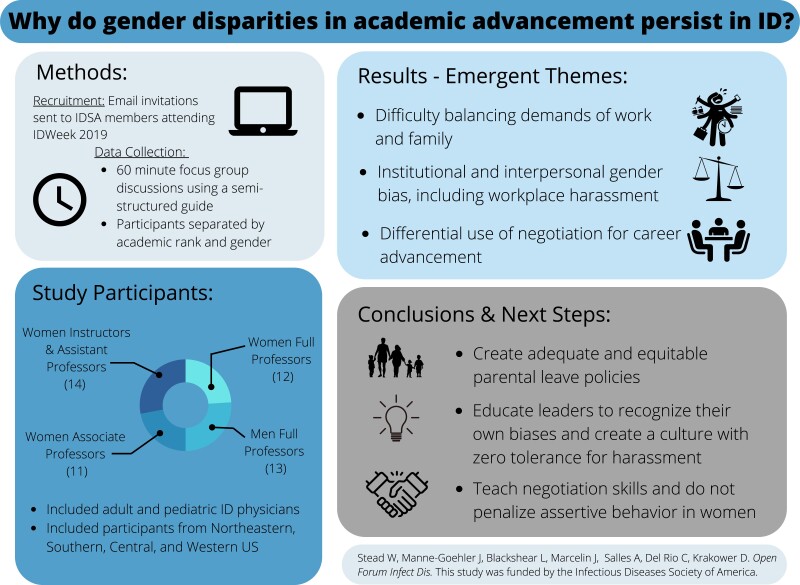

Gender inequities in academic advancement persist in many specialties, including Infectious Diseases (ID). Prior studies of advancement disparities have been predominantly quantitative, utilizing large physician databases or surveys. We used qualitative methods to explore ID physicians’ experiences and beliefs about causes and ways to mitigate gender inequities in advancement.

Methods

We conducted semistructured focus group discussions with academic ID physicians in the United States at IDWeek 2019 to explore perceived barriers and facilitators to academic advancement. Participants were assigned to focus groups based on their academic rank and gender. We analyzed focus group transcripts using content analysis to summarize emergent themes.

Results

We convened 3 women-only focus groups (1 for instructors/assistant professors, 1 for associate professors, and 1 for full professors) and 1 men-only focus group of full professors (total N = 50). Our analyses identified several major themes on barriers to equitable academic advancement, including (1) interpersonal and institutional gender bias, (2) difficulty balancing the demands of family life with work life, and (3) gender differences in negotiation strategies.

Conclusions

Barriers to gender equity in academic advancement are myriad and enduring and span the professional and personal lives of ID physicians. In addition to swift enactment of policy changes directed at critical issues such as ending workplace harassment and ensuring adequate parental leaves for birth and nonbirth parents, leaders in academic medicine must shine a bright light on biases within the system at large and within themselves to correct these disparities with the urgency required.

Keywords: achievement, advancement, bias, gender differences, medical faculty

Quantitative data repeatedly show a gender gap in academic advancement in ID. This qualitative exploration of barriers to advancement identifies key themes perpetuating disparities, including institutional and interpersonal gender bias, difficulty balancing work and family, and gender differences in negotiation.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

There is a large and persistent gap in achievement and advancement between men and women faculty in academic medicine, including in Infectious Diseases (ID) [1–5]. In a 2014 study of 2016 academic ID physicians in the United States, there was an 8% adjusted disparity in the rate of advancement to full professorship among women compared with men after adjustment for key demographic and achievement-related metrics [1, 6]. A more recent study of 559 098 graduates of US medical schools over 35 years similarly showed women were less likely than men to be promoted to the rank of associate or full professor [5]. Moreover, in both of these studies, gender differences in promotions within academic medicine did not diminish over time and were not smaller in later residency graduation cohorts than in earlier cohorts [1, 5]. These findings suggest a persistent and pervasive gender gap in advancement in academic medicine and highlight the urgency to identify the underlying causes of these disparities so that effective strategies can be developed to mitigate them [7].

Although these differences are increasingly well recognized, the barriers responsible for delayed advancement among women faculty remain incompletely understood. The literature to date has begun to explore work-related factors such as ineffective mentorship and disparate institutional and salary support, as well as personal and cultural factors such as childcare and domestic responsibilities. However, these studies are limited in that they examine only single factors or are designed in such a way as to be unable to capture the complex sources of these disparities [8–14]. The preponderance of this literature has been quantitative, measuring repeatedly the existence and magnitude of gender disparities; however, there has been only limited qualitative exploration of the perceived causes of this disparity [15–19]. The objective of this study was to identify and characterize perceptions about why gender disparities in academic advancement persist in ID by asking ID faculty members to share their perceptions and experiences with the advancement process. To do this, we conducted a series of focus groups with ID faculty, because this offered a way for participants to share rich personal perspectives on the drivers of gender-related gaps in promotion and the impact of these inequities on their professional careers. We previously reported on findings relating to policy implications from these focus groups as part of a mixed-methods study on gender disparities in academic promotion with Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) members [20]. In this study, we report on a broader suite of themes from these focus group discussions in an effort to enrich understanding of the fullest spectrum of factors contributing to gender disparities in academic advancement in ID.

METHODS

We conducted four 60-minute, in-person focus groups with ID faculty members during IDWeek 2019 as previously described [20]. Participants were recruited through the IDSA using email invitations targeted to members registered to attend IDWeek. To best capture perspectives of ID faculty members from diverse professional backgrounds, we asked potential participants to share their academic affiliation and current academic rank. We did not collect age, race, or ethnicity of participants given our primary focus on gender.

We used purposive sampling to enroll women from medical schools in each of the 4 geographic regions of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), including those both on and off the US News and World Report's Honor Roll. We recruited faculty from every rank (Instructor, Assistant Professor [AP], Associate Professor [ACP], Full Professor). We assigned participants to focus groups based on their academic rank to allow for a session exclusively for instructors/APs, one for ACPs, and a third session for full professors. We also conducted a fourth focus group with only men who were full professors at US academic medical centers to capture additional perspectives about barriers to advancement and solutions. Although we recognize there are multiple genders and that people who identify as gender minorities may face unique barriers to career advancement, throughout this manuscript we limit our discussion to men and women because this is how our participants identified. We chose to organize focus groups by rank to minimize social desirability bias across rank (ie, to allow for both junior and senior faculty members to speak freely about barriers to advancement). Each focus group participant was assigned a number by which they were identified in the group discussion.

A member of the study team facilitated each discussion using a semistructured interview guide consisting of open-ended questions designed to generate discussion about perceived barriers to academic advancement and proposed policy solutions (Supplementary materials). Discussions were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. A scribe was present during each focus group to keep a written record of participant responses by number, allowing for clarification of discussions that were difficult to understand on audiorecording.

Qualitative data were analyzed using content analysis to summarize and highlight emergent themes [21]. Two members of the research team used an inductive process to develop a topic codebook guided by our research objectives. One of these researchers then applied codes to sections of raw data for all study transcripts and the other researcher reviewed the application of codes in detail, and any disagreements in coding were resolved through discussion. Thereafter, these researchers independently reviewed the coded transcripts to determine emerging themes and then together agreed upon final themes. The study was determined to be exempt by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Fourteen Instructors/APs, 11 ACPs, and 12 Full Professors participated in the respective women faculty focus groups. There were 13 participants in the men Full Professor (MFP) group. All women focus groups included both Pediatric and Adult ID faculty participants. Details of focus group participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Without access to race or ethnicity data, we are unable to perform intersectional analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Focus Group Participants

| Gender and Level of Advancement | Number of Focus Group Participants | AAMC Region (Northeast, Central, Western, Southern) | US News and World Report Top 20 Hospitals | Pediatric Infectious Diseases | Adult Infectious Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assistant Professor or Instructor Women | 14 | 4 NE 3 Central 3 Southern 4 Western |

6 | 1 | 13 |

| Associate Professor Women | 11 | 4 NE 1 Central 6 Southern |

4 | 5a | 6 |

| Full Professor Women | 12 | 4 NE 1 Central 6 Southern 1 Western |

3 | 1 | 11 |

| Full Professor Men | 13 | 8 NE 2 Central 2 Southern 1 Western |

6 | 0 | 13 |

Abbreviations: AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; NE, Northeast.

Group includes 1 Medicine-Pediatrics Infectious Diseases participant.

Focus group discussions generated main emergent themes regarding barriers to academic advancement of women in ID summarized in Table 2. The spectrum of emergent themes was broad and included work-related barriers, such as limited sponsorship opportunities and lack of effective promotions advising, and also more personal and cultural barriers to advancement. Work-related themes included inadequate advising and unachievable metrics for academic promotion, ineffective sponsorship of junior faculty, and lack of advocacy for change from those in positions of power, which we reported elsewhere [20]. In addition to specific work-related barriers, several new themes emerged and were also believed to contribute substantially to disparities in academic advancement. These themes included (1) contribution of gender bias, both on an interpersonal and an institutional level, to delayed advancement (2) difficulty balancing the demands of family life with work life, and (3) perceived differences in negotiation strategies and effectiveness between genders.

Table 2.

Summary of Main Emergent Themes From Focus Group Analysis

| Gender bias contributes to delayed academic advancement for womena |

| Balancing demands of family with academic advancement is difficulta |

| Women are less likely than men to use negotiation to advance themselvesa |

| University metrics for promotion are not consistent with academic physician achievements |

| Taking on divisional/departmental “citizenship tasks” may delay junior faculty advancement |

| Policy change must come from “the top” (people/organizations in positions of leadership/privilege) |

| Advising and transparency about promotions criteria by objective/expert advisors is crucial |

| Sponsorship facilitates academic advancement |

| Women in positions of leadership or at higher levels of advancement should help junior women |

Themes addressed in present manuscript. Other themes listed represent organizational/work-specific barriers to academic advancement reported previously with associated policy change recommendations [20].

Theme 1: Gender Bias Contributes to Delayed Academic Advancement for Women

Gender bias as a barrier to the academic advancement of women was a major theme in all focus groups, although this was addressed significantly more often by women focus groups than by the men focus group. We categorized gender bias examples as either institutional or interpersonal [22]. This framework was chosen to (1) shift focus away from the intentionality of the individual(s) enacting bias (ie, implicit vs explicit bias), which was difficult to determine with our study design, and to (2) highlight that bias, particularly when implicit, can come from individual behaviors or be structural and directly embedded in the system itself.

Descriptions of institutional gender bias are outlined in Table 3, including examples of academic recruitment and hiring practices that were believed to put women at a disadvantage as they sought faculty jobs and tried to ascend the academic advancement ladder. Examples included women being disproportionately excluded from pursuing tenure tracks due to stereotyped concerns by institutional leaders that women might not be able to keep up with the expected timelines, as well as inadequate representation of women on recruitment and promotions committees at many academic institutions, even as their numbers overall increased among academic faculty. Participants also identified examples of gender bias in institutional policies that were inhospitable to parents and believed to affect women disproportionately such as required meetings scheduled during typical school drop-off or pick-up times and absent or poorly maintained lactation rooms. Inadequate parental leave policies, affecting both birth parents (defined as the parent who gives birth to a child) and nonbirth parents, were also repeatedly mentioned with potential to delay academic advancement disproportionately for women (who are most commonly the birth parent) because many have to make up missed clinical work or Relative Value Units targets upon return, which may be disruptive to scholarly pursuits. Inadequate parental leave for nonbirth parents was also identified by focus group participants as discriminatory toward men (who are most commonly the nonbirth parent) and believed to establish an early, and often perpetuated, dynamic by which women assume the greater burden of childcare from the time of the child's birth, having potential downstream, longer term impact on their scholarly productivity.

Table 3.

Qualitative Analysis of Major Themes From Focus Group Responses, Narrative Comments Were Grouped Through an Inductive Thematic Analysis, and Representative Comments Were Selected for Each Theme (N = 50 Participants)

| Themes | Representative Comments |

|---|---|

| Gender Bias Contributes to Delayed Academic Advancement for Women | |

| Institutional Gender Bias | |

| Hired but Hamstrung—Recruitment Bias | MFP—We have two tracks and almost all the women were on the non-tenure track…So there was some sort of implicit bias when they were hired…they were placed on this non-tenure track because they couldn’t keep up with the clock WFP—When something happens that's egregious, when there's a…department chair search committee and there are no women, I think that has to be called out |

| Family “Unfriendly” Policies | AP—I had my children after I became faculty, but I was expected to have the exact same productivity the year I took maternity leave…there was no pro-rating of RVUs or clinical time… I took 8 weeks off because I could not possibly squeeze anything else inside of that calendar year and still meet my metrics. AP—If you choose to nurse, you have a full clinic schedule, there's no pumping time…so you have to make your patients wait…there's no place for you to pump in the clinic. When I would get to the hospital, the pumping room was so disgusting that I would not go in there ACP—We are required to attend…but the faculty meeting was 7:30 in the morning…I have two kids that [have] 8:30 drop off…so that's never going to work. |

| Interpersonal Gender Bias | |

| Assertiveness Interpreted as Aggression—Price of Gender Norm Violations | AP —I get positive reinforcement if I stick in the female role and be nice and sweet and say yes to everything, but then I worry I’m not going to advocate for myself, I’m not going to be assertive…because I don’t get the same sort of societal positive reinforcement when I act outside gender norms |

| Harassment in the Workplace | WFP—I’ve actually been kissed. I had someone blow on my neck during rounds. I got trapped by a dean in his apartment WFP—Two women…were completely intellectually abused by their mentors…their mentors took credit for their work and in both situations the men were their bosses ACP—A colleague…was having her mid-tenure review in a male dominated department….and one of the committee members said, “I’m sorry, you’re just going to have to speak up. I’m just not hearing you” and midway through her talk, finally stopped and said “well I guess we all know it's a known fact that women's voices don’t …come across as authoritative…so that's why I can’t hear you” |

| Balancing Demands of Family With Academic Achievement Is Difficult | |

| Delaying Childbearing Until After Training | AP—I delayed having a family to the point where I’m 34 now, so it's a dangerous zone for me, because I wanted to progress in my career…and now I don’t know if I’m going to be able to sustain what I’ve built on and that's a big fear for me. |

| Less Travel for Career-Related Opportunities | MFP—At the highest levels (of advancement) there is requirement for international travel-international recognition. It's very hard for people who are the major caregivers in their household, you know? Right or wrong, women are more likely to be running the households than men. |

| Disproportionate Care for Sick and Aging Parents | MFP—caring for the sick parents falls disproportionately on women too. So it's like a double whammy to get through having the children…and then they get hit with a sick parent |

| Part-Time Employment Affects Advancement Opportunities | AP—I have a colleague who went to part time because she wanted to be the one to pick up her kids, which basically meant still working…still trying to direct things. She's not part-time in the least. All that happened is the hospital has gotten away with not having to pay her as much. |

| Women Are Less Likely Than Men to Use Negotiation to Advance Themselves | |

| Less Negotiation for Compensation/Positions | AP—As we were negotiating for our first jobs, the only advice my female co-fellows and I were given was from one female attending who told us when she was going for a job, she was told that since her husband was a cardiologist, she didn’t need to be paid as much, so they kind of gave her half a salary. |

| Less Negotiation for Career Advancement Resources | WFP—It's clearly harder for women, women get grants at NIH at the same rate as men, but they ask for less money so they are funded less well. They don't look for retention packages at the same rate, so once they're in a system, they don't get all those financial bonuses |

| Less Likely to Self-Nominate | ACP—Women tend to look at the (promotion) checklist and we don’t think we’re ready until we check every box off. The guys are just like “It's time to go!” |

| Fear That Negotiation Is Aggressive Behavior | WFP—I don’t think women negotiate on their own best behalf because they get hung up about modesty issues, about looking too aggressive when the reality is that you should negotiate and the only power you have is before you sign. |

Abbreviations: ACP, Associate Professor; AP, Assistant Professor; MFP, men Full Professor; RVUs, Relative Value Units; WFP, women Full Professor.

Examples of interpersonal gender bias also arose frequently in the focus groups and included several stories of clear-cut harassment, both sexual and professional (Table 3). It is notable that examples of interpersonal gender bias in the form of explicit harassment emerged more often in the women full professor (WFP) group than in the early careerwomen focus groups, perhaps reflecting WFP careers spanning times when sexual and other forms of harassment against women were more tolerated in the workplace. It is interesting to note that examples of explicit harassment were not mentioned at all in the MFP focus group. In addition to explicit examples of interpersonal gender bias, focus group participants also shared stories of perceived downstream negative consequences for women when they behaved, or witnessed women colleagues behaving, outside of stereotyped gender norms. Many of these stories shared the central element of a woman's attempt at assertiveness, which was interpreted as aggression, and the negative impact of this behavior on her overall image and work relationships with colleagues and/or supervisors.

Theme 2: Balancing Demands of Family With Academic Achievement Is Difficult

Difficulty balancing demands of family with academic achievement was also one of the top themes in all focus groups, although this was disproportionately addressed by the women instructor/AP compared with the other groups, perhaps as a function of the age and life stage of this particular group. Beyond the concept that women faculty may spend disproportionately more time on dependent care than their men colleagues, our focus group participants added unique and specific insights to further expound upon this issue.

Examples outlined in Table 3 included delaying childbearing until posttraining and the resultant downstream career advancement consequences of balancing childcare with clinical and research productivity demands, especially of academic junior faculty positions. Young faculty parents were also identified as less likely to travel for academic conferences, speaking engagements, and job opportunities, all of which could negatively impact academic advancement. Caring for sick parents was also raised as a burden of family care that may affect later career women disproportionately to their male counterparts. Accepting “part-time” employment with the goal of better balancing childcare and work demands was also mentioned as a career choice more often sought by women, leading to potential negative impact on academic advancement because faculty working less than full-time equivalent are often perceived as less academically invested.

Theme 3: Women Are Less Likely Than Men to Use Negotiation to Advance Themselves

A final theme discussed frequently in all focus groups, although especially prominent in our women ACPs compared with other groups, was the impact of gender differences in negotiation strategies upon academic advancement. Focus group participants shared many examples suggesting women faculty negotiate less overall than men and also, when they do negotiate, may do so less effectively because these skills may be less often taught and/or modeled for women. Specific examples outlined in Table 3 included ineffective negotiation for financial compensation, startup and retention packages, but also ineffective negotiation for vital resources such as research support, personnel, and protected time, which could be especially important to academic advancement opportunities. Women were also perceived as less likely to nominate themselves for awards and other career opportunities than their male counterparts.

DISCUSSION

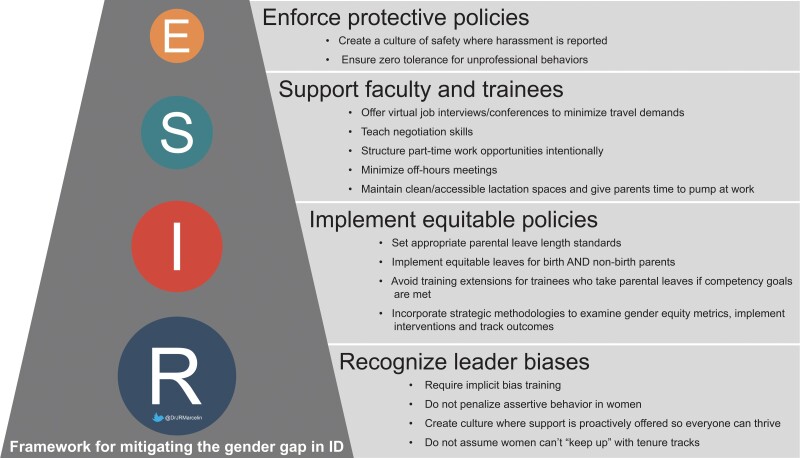

Given the clear and persistent evidence that women are not advancing in academic medicine and ID as successfully as men, it is critical to highlight the underlying barriers leading to this problem and identify solutions. This study took place before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which has likely further exacerbated these disparities by decreasing academic and research productivity among women, especially those with young children, because they take on a disproportionate burden of caregiving and home schooling [23, 24]. Our rich focus group discussions among IDSA members raised several important themes and examples of barriers that could be addressed by both large institutional and cultural change and also smaller scale interventions. A framework summarizing these changes is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Framework for mitigating the gender gap in ID.

In our study, gender bias was identified in all focus groups as a major barrier to the advancement of women in academic ID. Previous work in this area has also identified gender bias as an impediment to women's salary equity and professional advancement [8, 16]. Although we are not able to address this with our data, Black, Latina, and Indigenous women likely face even more of these obstacles than do White women [25]. Our women focus group participants had encountered bias both within their professional interpersonal interactions and as a structural force embedded within their systems of work. Thus, building a culture conducive to gender equity in academic medicine requires interventions both on the institutional and interpersonal levels [22, 26, 27]. Large-scale initiatives such as institutional workshops teaching intentional gender bias behavioral change [28] and innovative programs introduced at a national level by professional organizations [29, 30] have shown positive effects at reducing gender bias and improving advancement disparities. Although large-scale cultural and institutional change is urgently needed to overcome hundreds of years of firmly rooted gender bias, even smaller scale local changes such as clean and convenient lactation rooms for nursing parents and ensuring women are proportionately represented on search and promotions committees can make a positive difference. In addition, explicit harassment, both sexual and professional, was frequently cited by women as being extremely disruptive and obstructive to their careers, a finding consistent with recent work of others, suggesting a need to replace existing policies around harassment with more effective ones [31, 32]. Without taking urgent action to curb harassment, gender-based disparities will persist.

Difficulty balancing demands of family with academic achievement has been noted in several studies and is true of all genders, but this is likely to be more detrimental to career advancement for women, who often carry a disproportionate share of childcare responsibilities [33, 34]. As we found in our study with ID physicians, women may attempt to mitigate or postpone this conflict by delaying attempts at pregnancy and childbirth, sometimes at increased risk to the health of their infants and themselves or at the expense of an opportunity to have children at all [35, 36]. Several focus group participants described “waiting until training is done” to attempt to have children only to find the demands of junior faculty roles were also extremely strenuous.

In light of our study findings and the prior literature, it is difficult to overstate the crucial importance of implementing adequate and equitable parental leave policies for both birth and nonbirth parents. The current practice at some academic medical centers of expecting faculty parents to take brief and inadequate leaves or to “make up” clinical, administrative, or research work upon their return, while also shouldering the heavy burdens of infant care, makes it extremely difficult to be productive in scholarly pursuits. A recent study also showed a majority of US ID fellowship program directors misinterpret American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) leave policies, which could lead to shortened parental leaves and unnecessary fellowship training extensions [37]. Improving and standardizing parental leave policies during residency or fellowship training and for faculty members could encourage physicians to start or grow families at times that meet their personal needs, as opposed to driving them towards delayed parenting and its potentially adverse consequences. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and various specialty licensing boards have an opportunity and the power to guide innovation in this area by setting standards for minimum trainee parental leave lengths, a strategy the American Board of Medical Specialties adopted in 2021 and the ACGME codified in its institutional requirements effective July 2022, suggesting all trainees should have at least 6 weeks of leave [38, 39]. However, beyond setting minimum leave lengths that are variably applied, specialty licensing boards should allow training program directors to have independence in structuring individualized leaves based on trainee competence rather than arbitrary time limits and/or procedure numbers [40, 41]. Furthermore, efforts to address inequities in typical leave length policies for birth versus nonbirth parents could allow both parents more opportunity to share in infant care duties, which may also have downstream positive effects on women's academic productivity during this busy and exhausting time. In addition, academic institutions need to revisit their promotional processes and criteria to support all faculty and trainees who decide to grow families, and not penalize them for this choice, so that women can be appropriately and equitably represented at all levels of the academic hierarchy.

In addition to delaying childbirth, our findings suggest that women parents in ID may also travel less for professional conferences, presentations, or job interviews, decreasing their opportunities for national or international exposure often necessary for academic advancement to the highest levels. This issue could be addressed by offering more virtual conferences or interviews, opportunities that have become more common during the COVID-19 pandemic. Onsite childcare services at conferences could also help parents who wish to attend in person do so more easily [42]. Finally, parents who attempt to balance family and work demands by exploring part-time faculty roles need highly structured and specifically defined job descriptions, so they do not end up getting paid less to do the same amount of work. Innovative academic job descriptions that allow parents the flexibility to work from home while still remaining effectively full-time for academic purposes should be developed. More importantly, parents who explore or adopt part-time work should not be assumed to be less interested in academic advancement because part-time work and academic aspirations are not mutually exclusive.

Many have written about gender differences in both the willingness to negotiate and the success of negotiation strategies when used by women compared with men across many industries, and our study supports these differences also exist in academic ID [43]. Women who do not effectively negotiate miss opportunities for career advancement resources such as research assistants and grants, salary increases, and self-nominated positions or awards, all of which may delay academic advancement. This barrier could be addressed by innovative curricula at the institutional and professional society levels to teach effective negotiation skills to trainees and junior faculty. Nonetheless, some gender-based difficulty negotiating may relate to women's fear of being perceived as “aggressive,” and the social penalties associated with behavior outside of traditional gender norms, and this will not be rectified by simple negotiation curricula. In addition to resisting the tendency to differentially penalize assertiveness in women, leaders should focus efforts on creating equitable systems in the first place, where the burden is not on individuals to fight for the support they need. Rather, supports need to be proactively offered, creating a culture in which everyone can thrive. Finally, leaders should utilize a strategic approach to measure gender equity metrics, implement interventions, and track outcomes, and they should be held accountable for lack of improvements [44].

Our qualitative study design has limitations, including that we were unable to conduct an exhaustive exploration of all barriers to academic advancement given limited time and resources to engage busy ID physicians. Although participants came from different regions of the United States and all stages of academic advancement, focus group volunteers were invited from a convenience sample of IDWeek 2019 attendees and may not represent the full spectrum of ID academic faculty opinions. Focus group participants from the Northeast and Southern United States were overrepresented relative to other regions, with substantially more adult than pediatric ID faculty. In addition, we were unable to assess the impact of intersectionality on academic advancement, although racial disparities in advancement have been identified by other studies [45–48]. Our sampling strategy did allow us to capture multiple perspectives across the academic hierarchy and by gender. Finally, an additional strength of our study was that the themes identified in our focus groups likely have broad applicability to other specialties within academic medicine.

CONCLUSIONS

The gender gap in academic advancement is a pervasive and significant problem in ID, which has not improved despite more women having entered the field over the last several decades, a finding wholly consistent with the inequities in academic medicine more broadly in the United States. Interpersonal and institutional gender bias (including harassment), difficulty balancing demands of family with academic advancement, and differences in negotiation strategies are key factors that should be the focus of policy interventions and cultural change. National and institutional leaders in ID should develop and implement policies and demand systemic change at the highest levels to correct this persistent disparity with the urgency it requires.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) for their guidance and support at IDWeek 2019. We also thank Drs. Vimal Jhaveri and Colleen Kershaw for their assistance during focus group sessions. We also give special thanks to Dr. Cynthia Sears for her support and encouragement for this project. Finally, we sincerely thank all of our focus group participants who so generously shared their time and their stories.

Author contributions. W. S., J. M.-G., and D. K. contributed to study concept, design, and supervision, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. L. B. contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. J. R. M., A. S., and C. d. R. contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Financial support. This work was funded by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Contributor Information

Wendy Stead, Division of Infectious Diseases, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Beth Israel Lahey Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Jennifer Manne-Goehler, Medical Practice Evaluation Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Division of Infectious Diseases, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Leslie Blackshear, Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Beth Israel Lahey Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Jasmine R Marcelin, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Arghavan Salles, Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine, Stanford University Department of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA; Senior Research Scholar, Clayman Institute for Gender Research, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, USA.

Carlos del Rio, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Douglas Krakower, Division of Infectious Diseases, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Beth Israel Lahey Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Manne-Goehler J, Kapoor N, Blumenthal DM, et al. Sex differences in achievement and faculty rank in academic infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70:290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marcelin JR, Manne-Goehler J, Silver JK. Supporting inclusion, diversity, access, and equity in the infectious disease workforce. J Infect Dis 2019; 220(Suppl 2):S50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, et al. Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA 2015; 314:1149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE, et al. Gender differences in academic medicine: retention, rank, and leadership comparisons from the national faculty survey. Acad Med 2018; 93:1694–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Richter KP, Clark L, Wick JA, et al. Women physicians and promotion in academic medicine. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:2148–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blumenthal DM, Olenski AR, Yeh RW, et al. Sex differences in faculty rank among academic cardiologists in the United States. Circulation 2017; 135:506–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM. The state of women in academic medicine 2018–2019: Exploring pathways to equity. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020. pp 1–49. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/2018-2019-state-women-academic-medicine-exploring-pathways-equity#:~:text=The%20State%20of%20Women%20in%20Academic%20Medicine%202018%2D2019%3A%20Exploring,in%20similar%20proportions%20since%202003.

- 8. Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176:1294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Holliday E, Griffith KA, De Castro R, et al. Gender differences in resources and negotiation among highly motivated physician-scientists. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30:401–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hechtman LA, Moore NP, Schulkey CE, et al. NIH funding longevity by gender. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115:7943–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boiko JR, Anderson AJM, Gordon RA. Representation of women among academic grand rounds speakers. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177:722–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, et al. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:344–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manne-Goehler J, Freund KM, Raj A, et al. Evaluating the role of self-esteem on differential career outcomes by gender in academic medicine. Acad Med 2020; 95:1558–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rajasingham R. Female contributions to Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline publications. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:893–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zakaras JM, Sarkar U, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Not just surviving, but thriving: overcoming barriers to career advancement for women junior faculty clinician-researchers. Acad Psychiatry 2021; 45:180–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barnes KL, McGuire L, Dunivan G, et al. Gender bias experiences of female surgical trainees. J Surg Educ 2019; 76:e1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Murphy M, Record H, Callander JK, et al. Mentoring relationships and gender inequities in academic medicine: findings from a multi-institutional qualitative study. Acad Med 2022; 97:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Isaac C, Byars-Winston A, McSorley R, et al. A qualitative study of work-life choices in academic internal medicine. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2014; 19:29–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ross MB, Glennon BM, Murciano-Goroff R, et al. Women are credited less in science than men. Nature 2022; 608:135–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manne-Goehler J, Krakower D, Marcelin J, et al. Peering through the glass ceiling: a mixed methods study of faculty perceptions of gender barriers to academic advancement in infectious diseases. J Infect Dis 2020; 222(Suppl 6):S528–S534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collingridge P. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jana T, Mejias A. Erasing Institutional Bias: How to Create Systemic Change for Organizational Inclusion. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dahlberg ML, Higginbotham E, eds. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Careers of Women in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2021. doi: 10.17226/26061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Krukowski RA, Jagsi R, Cardel MI. Academic productivity differences by gender and child age in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2021; 30:341–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Balzora S. When the minority tax is doubled: being Black and female in academic medicine. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 18:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Westring A, McDonald JM, Carr P, et al. An integrated framework for gender equity in academic medicine. Acad Med 2016; 91:1041–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morgan AU, Chaiyachati KH, Weissman GE, et al. Eliminating gender-based bias in academic medicine: more than naming the “elephant in the room”. J Gen Intern Med 2018; 33:966–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carnes M, Devine PG, Baier Manwell L, et al. The effect of an intervention to break the gender bias habit for faculty at one institution: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Acad Med 2015; 90:221–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee LK, Platz E, Klig J, et al. Addressing gender inequities: creation of a multi-institutional consortium of women physicians in academic emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med 2021; 28:1358–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ovseiko PV, Chapple A, Edmunds LD, et al. Advancing gender equality through the Athena SWAN Charter for Women in Science: an exploratory study of women's and men's perceptions. Health Res Policy Syst 2017; 15:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jenner S, Djermester P, Prügl J, et al. Prevalence of sexual harassment in academic medicine. JAMA Intern Med 2019; 179:108–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pololi LH, Brennan RT, Civian JT, et al. Us, too sexual harassment within academic medicine in the United States. Am J Med 2020; 133:245–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carr PL, Ash AS, Friedman RH, et al. Relation of family responsibilities and gender to the productivity and career satisfaction of medical faculty. Ann Intern Med 1998; 129:532–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Levinson W, Tolle SW, Lewis C. Women in academic medicine. Combining career and family. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:1511–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marshall AL, Arora VM, Salles A. Physician fertility: a call to action. Acad Med 2020; 95:679–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marshall AL, Salles A. Supporting physicians along the entire journey of fertility and family building. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5:e2213342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gardiner C DL, Finn K, McDonald FS, Melfe M, Melia M, Stead W. Paying for parenthood: misinterpretation of ABIM leave policies may lead to unnecessary extension of ID fellowships in IDWeek 2021. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 8(Suppl 1):54. [Google Scholar]

- 38. American Board of Medical Specialties . American Board of Medical Specialties policy on parental, caregiver and medical leave during training. Available at: https://www.abms.org/policies/parental-leave/. Accessed January 10, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Institutional Requirements . Available at: https://www.acgme.org/designated-institutional-officials/institutional-review-committee/institutional-application-and-requirements/. Accessed August 4, 2022.

- 40. Marshall AL, et al. Parental health in fellowship trainees: fellows’ satisfaction with current policies and interest in innovation. Womens Health (Lond) 2020; 16:1745506520949417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Altieri MS, Salles A, Bevilacqua LA, et al. Perceptions of surgery residents about parental leave during training. JAMA Surg 2019; 154:952–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sheffield V, Marcelin JR, Cortes-Penfield N. Childcare options, accommodations, responsible resources, inclusion of parents in decision-making, network creation, and data-driven guidelines (CARING) at infectious disease week (IDWeek): parental accommodations and gender equity. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72:2220–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Babcock L, Laschever S. Women Don’t Ask: The High Cost of Avoiding Negotiation and Positive Strategies for Change. New York, New York: Bantam Books, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Spector ND, Asante PA, Marcelin JR, et al. Women in pediatrics: progress, barriers, and opportunities for equity, diversity, and inclusion. Pediatrics 2019; 144: e20192149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kaplan SE, Raj A, Carr PL, et al. Race/ethnicity and success in academic medicine: findings from a longitudinal multi-institutional study. Acad Med 2018; 93:616–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fang D, Moy E, Colburn L, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in faculty promotion in academic medicine. JAMA 2000; 284:1085–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Mouratidis RW. Where are the rest of us? Improving representation of minority faculty in academic medicine. South Med J 2014; 107:739–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nunez-Smith M, Ciarleglio MM, Sandoval-Schaefer T, et al. Institutional variation in the promotion of racial/ethnic minority faculty at US medical schools. Am J Public Health 2012; 102:852–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.