Abstract

Coimmunization with peptide constructs from catalytic (CAT) and glucan-binding (GLU) domains of glucosyltransferase (GTF) of mutans streptococci has resulted in enhanced levels of antibody to the CAT construct and to GTF. We designed and synthesized a diepitopic construct (CAT-GLU) containing two copies of both CAT (B epitope only) and GLU (B and T epitope) peptides. The immunogenicity of this diepitopic construct was compared with that of individual CAT and GLU constructs by immunizing groups of Sprague-Dawley rats subcutaneously in the salivary gland vicinity with the CAT-GLU, CAT, or GLU construct or by treating rats by sham immunization. Levels of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody to GTF or CAT in the CAT-GLU group were significantly greater than in GLU- or CAT-immunized groups. Immunization with CAT-GLU was compared to coimmunization with a mixture of CAT and GLU in a second rodent experiment under a similar protocol. CAT-GLU immunization resulted in serum IgG and salivary IgA responses to GTF and CAT which were greater than after coimmunization. Immunization with the diepitopic construct and communization with CAT and GLU constructs showed proliferation of T lymphocytes to GTF. Immunization with either the CAT or GLU construct has been shown to elicit significant protection in a rodent dental caries model. Similarly in this study, the enhanced response to GTF after immunization with the CAT-GLU construct resulted in protective effects on dental caries. Therefore, the CAT-GLU diepitopic construct can be a potentially important antigen for a caries vaccine, giving rise to greater immune response than after immunization with CAT, GLU, or a mixture of the two.

Dental caries is a widespread infectious disease. Slightly less than half of U.S. children aged 5 to 17 have caries on coronal surfaces of their permanent dentition (12). Untreated and nursing bottle caries are prevalent in underprivileged children and in native Americans (7). Caries in these populations would be most amenable to public health measures (such as vaccine), as would caries in numerous other countries. Previous studies have described the molecular pathogenesis of the disease and its primary association with the mutans group of streptococci (11, 13). Initial colonization of the pellicle appears to be related to the mutans streptococcal adhesin PAc (28). These microorganisms can accumulate on teeth in the presence of sucrose. This accretion is facilitated by extracellular glucan, which is synthesized from sucrose by a group of enzymes collectively called glucosyltransferases (GTF) (11), and by the presence of mutans streptococcal glucan-binding protein (35). The most significant antigen involved in accumulation seems to be GTF (32), which is composed of two functional domains, i.e., a catalytic domain and a glucan-binding domain (17).

Structurally, portions of the GTF protein appear to resemble α-amylase, sharing a similar (α/β)8 barrel domain in the amino-terminal half of the molecule (16). This domain is important in the catalytic activities of these enzymes (16). GTF appears to contain several candidate catalytic subdomain sites, as indicated by site-directed mutagenesis (34) and sequence alignment with catalytically similar enzymes (5, 16, 34). The carboxy termini of the GTF molecules from mutans streptococci have differing numbers of highly conserved, structurally similar repeat regions which have been associated with carbohydrate binding (19, 25). Passive or active immunization of adults with either PAc or GTF as antigen can modify natural infection (15, 26). Antibody to the GTF appears to interfere with amassing of mutans streptococci in dental plaques (26).

Synthetic peptides can give rise to immune response in association with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on antigen-presenting cells after specific recognition by T cells (1). However, such peptides have a short half-life and are poorly immunogenic. Numerous strategies have been used to enhance peptide immunogenicity, including constructing multiple epitopes on branched lysine residues during peptide synthesis (29). These constructs are called multiple antigenic peptides (MAP).

Immunization of Sprague-Dawley rats with MAP constructs designated CAT (27) from the catalytic domain (27) or GLU (25) from the glucan-binding domain of GTF can provide immune response to GTF and result in protection in experimental dental caries (30). Other studies indicated that CAT contained a B-cell epitope and GLU contained a B-cell and potent T-cell epitopes (31). We also demonstrated that coimmunization with an admixture of CAT and GLU resulted in enhanced response to GTF compared to immunization with the individual components and protection from experimental dental caries in rodents (33). In the present study, we design a diepitopic construct in which two copies each of the CAT and GLU peptides were combined on a lysine backbone. This diepitopic construct was then evaluated for immunogenicity in comparison with CAT and GLU constructs, given separately and together.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Sprague-Dawley rats (devoid of mutans streptococci) raised in our facility, weaned at approximately 20 days, and fed a high-sucrose diet (Diet 2000), as previously described (33), were used in all experiments.

Peptide constructs.

A CAT construct, a GLU construct, and a diepitopic construct containing two copies of CAT and two copies of GLU on a lysine backbone (CAT-GLU) were used in this study. The CAT peptide was synthesized (AnaSpec Inc., San Jose, Calif.) as a MAP construct (27). The CAT peptide (DANFDSIRVDAVDVNDALLQ) contains an aspartic acid shown to be involved in the catalytic reaction of GTF with sucrose (18). The CAT construct was prepared using the stepwise solid-phase method on a core matrix of three lysines to yield four identical 21-mer peptides per molecule. Repeating sequences within the C-terminal third of the GTF molecule have been associated with binding of glucan (19, 35). The sequence of a 22-mer GLU peptide TGAQTIKGQKLYFKANGQQVKG, derived from the repeat region of Streptococcus downei GTF-I (25) was 86% homologous with a Streptococcus sobrinus GTF-I sequence (6). Both the CAT and GLU peptide constructs were synthesized (AnaSpec) on a core matrix of three lysines to yield four identical peptides per molecule (purity, >90%). A diepitopic CAT-GLU construct containing two copies each of CAT and GLU on a lysine backbone was also synthesized (AnaSpec) to yield a MAP molecule (purity, >80%) with two identical CAT peptides and two identical GLU peptides.

GTF enzymes.

GTF enzymes from S. sobrinus strain 6715 were obtained as previously described (25) after bacterial growth in glucose-containing defined medium, followed by a series of chromatography steps on Sephadex G-100 (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, N.J.) in 3 M guanidine HCl and fast protein liquid chromatography on Superose 6 (Pharmacia) in 6 M guanidine (25, 33). The GTF contained GTF-I, GTF-U, and GTF-S, as described elsewhere (4, 33), and was used for inhibition assays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) measurements of antibody activity.

Experimental protocols.

Two experiments were performed to evaluate the immunogenicity of the diepitopic CAT-GLU construct, and a third experiment was conducted to evaluate the effects of immunization with CAT-GLU on dental caries pathogenesis.

Experiment 1.

The first experiment was designed to compare immune responses to the CAT-GLU construct and the CAT and GLU constructs. Four groups of Sprague-Dawley male rats (devoid of mutans streptococci; n = 6 to 12) were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) in the salivary gland vicinity (sgv). The initial injections were in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) and included buffer (sham), the CAT construct (50 μg/rat), the GLU construct (50 μg/rat), or the diepitopic CAT-GLU antigen (100 μg/rat, equivalent to 50 μg of each monoepitopic construct). Seven days later, these groups were injected with doses described above in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA) or alum (for some sham-immunized animals). Blood and saliva were taken for immunological assays at 14, 21, 28, 35, and 49 days after the first injection. Animals were bled from the tail vein, and saliva was collected after injection of pilocarpine (1.0 mg/100 g of body weight; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) under ether anesthesia. The experiment was terminated 94 days after the initial infection.

Experiment 2.

The second experiment was designed to compare immune responses to the CAT-GLU construct and to coimmunization with a mixture of CAT and GLU constructs (CAT/GLU). Six groups of Sprague-Dawley male rats (n = 6 or 7) were injected twice s.c. in the forelimbs, the scruff of the neck, and the sgv. The initial injections were in CFA and included buffer (sham immunized), the CAT construct (50 μg), the GLU construct (50 μg), a mixture of the CAT (50 μg) and GLU (50 μg) constructs in adjuvant (coimmunized group), the diepitopic CAT-GLU antigen (100 μg), or GTF (25 μg). The second injection, 7 days later with doses described above, was in IFA. The experiment proceeded for 25 additional days until termination. Blood and saliva were taken for immunological assays, and serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) and saliva IgA antibody levels were tested.

Experiment 3.

The third experiment was designed to evaluate the effects of antibody to the diepitopic CAT-GLU construct on GTF function and on dental caries. Six groups of 9 female 20- to 23-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats were injected twice s.c. in the sgv at a 7-day interval. The initial injections were in CFA with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (two sham-immunized groups), the CAT construct (50 μg/rat), the GLU construct (50 μg/rat), the diepitopic CAT-GLU construct (100 μg/rat), or GTF (25 μg/rat). The second injection, 7 days later with the amounts above, was in IFA. Prior to infection (23 days after the first injection), animals were bled. Then, all groups but one sham-immunized group were orally infected three times with 108 viable cells of streptomycin-resistant S. sobrinus strain 6715 on experimental days 23, 24, and 25. Infection, verified in rats by systematic tooth swabbing and plating on mitis-salivarius agar containing streptomycin, proceeded for 62 days, at which time the experiment was terminated and blood and saliva were collected.

ELISA.

Antigens used for serum ELISA were 0.5 μg of CAT, 0.5 μg of GLU, 0.15 μg of S. sobrinus GTF, and 1 μg of CAT-GLU per well. At 2-h intervals, rabbit anti-rat IgG (isotype specific) was added followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG-alkaline phosphatase (BioSource International, Camarillo, Calif.). Antigens used for saliva ELISA were 1 μg of CAT, 1 μg of GLU, 0.3 μg of S. sobrinus GTF, and 1 μg of CAT-GLU per well. At 2-h intervals, the following were added: monoclonal mouse anti-rat α chain (Zymed Laboratories Inc., South San Francisco, Calif.), biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy and light chains; Zymed), and alkaline phosphatase-avidin (ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, Ohio). Serum and saliva ELISAs were developed with p-nitrophenylphosphate (Sigma) and read on a photometric scanner (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, Vt.) at 405 nm; results were expressed as ELISA units (EU) calculated relative to titration of the appropriate reference standard serum for each isotype. ELISAs to GTF, CAT, GLU, and CAT-GLU antigens were performed on sera diluted 1:100 and saliva diluted 1:4.

GTF inhibition assay.

Rat sera were evaluated for the ability to inhibit glucan synthesis by GTF in a modified filter assay (30). Serum (1 μl) and the immunizing S. sobrinus GTF were combined in a final volume of 100 μl in 0.02 M PBS and 0.02% sodium azide (PBSA; pH 6.5) and incubated for 2 h in a 37°C shaking water bath. To this was added 100 μl of PBSA containing 0.85 mg of sucrose and 22 nCi of [14C]glucose-sucrose (approximately 50,000 cpm) in the absence of primer, and the mixture was reincubated for 1.5 h. The samples were then filtered for insoluble glucan on Whatman GF/F glass fiber filters, washed with PBSA, air dried, and counted by liquid scintillation spectrometry (30). Percent inhibition of enzyme activity was calculated from the mean of sham control counts per minute incorporation, considered 100%.

Lymphocyte proliferation.

At the termination of experiment 2, single-cell suspensions of lymphocytes dissected from pooled cervical, axillary, and brachial lymph nodes of each animal were tested for proliferative responses as described elsewhere (33). Briefly, viable cells (5 × 105) per well were cultured in 96-well flat bottom tissue culture plates in 0.2 ml of complete RPMI 1640 with 2 mM l-glutamine, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, 12.5 mM HEPES, 10% fetal calf serum, and penicillin-streptomycin (100 U-100 μg/ml) at 37°C in 5% CO2. All parameters were tested at least in triplicate. Stimulation was with 2 μg of GTF/well for 4 days. [3H]thymidine (0.5 μCi/well) was added 24 h before harvest and counting by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

Caries assessment.

The extent and depth of carious lesions in all rat molar teeth (caries score) were microscopically evaluated by a modified Keyes method as previously described (30). The caries scores were determined separately on smooth and sulcal dental surfaces and then combined to obtain a total caries score.

RESULTS

Serum IgG immune response to S. sobrinus GTF after immunization with diepitopic CAT-GLU.

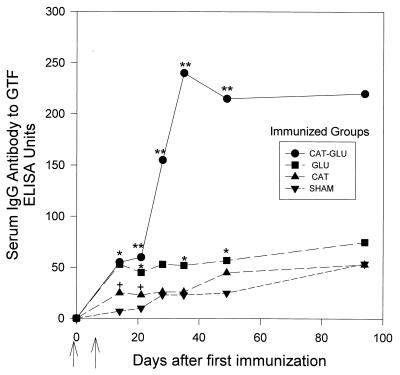

In experiment 1, the serum IgG antibody response to GTF was determined after immunization with CAT-GLU and compared to the response to immunization with the individual CAT and GLU constructs over a period of 94 days. The CAT-GLU-immunized group had mean IgG antibody levels significantly (5- to 10-fold) higher compared to the groups immunized with the CAT or GLU construct alone. This increase was demonstrated over the duration of the experiment (Fig. 1). In addition, both the CAT- and GLU-immunized groups demonstrated antibody to GTF significantly elevated above the control levels.

FIG. 1.

Serum IgG antibody response to GTF after immunization with the CAT, GLU, or CAT-GLU peptide construct antigen or sham immunization. Serum was taken 14, 21, 28, 35, 49, and 94 days after the first immunization (indicated by the first arrow); a second injection was given 7 days later in IFA (indicated by the second arrow). Each point represents the mean antibody level of at least six rats. The standard error ranged from 7 to 23% of the IgG antibody levels to GTF. ∗∗, the CAT-GLU-immunized group was significantly greater than the sham, CAT, and GLU groups, P < 0.001, SNK test. ∗, the GLU-immunized group was significantly greater than the sham group, at least P < 0.01, t test. +, the CAT-immunized group was significantly greater than sham group, at least P < 0.05, t test.

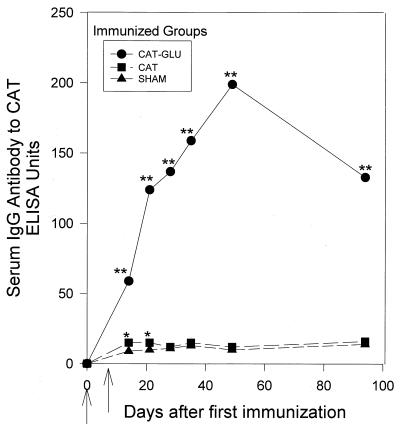

The serum IgG antibody response to the CAT construct after immunization with the diepitopic CAT-GLU is shown in Fig. 2. The CAT-GLU-immunized group showed significantly elevated IgG antibody to the CAT construct (P < 0.001), demonstrating a markedly increased CAT response above the level of IgG antibody elicited by CAT immunization alone (Fig. 2). Antibody responses to GLU in the GLU-immunized group and the CAT-GLU group were both significantly elevated on all sampling days (at least P < 0.05). However, no significant differences in antibody level to GLU were observed between these two groups (not shown).

FIG. 2.

Serum IgG antibody response to the CAT construct after immunization with CAT or CAT-GLU or sham immunization (GLU-immunized group not tested). Serum was taken 14, 21, 28, 35, 49, and 94 days after the first immunization (indicated by the first arrow); a second injection was given 7 days later in IFA (indicated by the second arrow). Each point represents the mean antibody level of at least six rats. The standard error ranged from 4 to 23% of the IgG antibody levels to GTF. ∗∗, the CAT-GLU-immunized group was significantly greater than the sham or CAT groups, P < 0.001, SNK test. ∗, the CAT-immunized group was significantly greater than the sham group, P < 0.05, t test.

The mean salivary IgA antibody levels (day 28) in the CAT-GLU-immunized group (171 ± 39 EU [mean ± standard error]) were also significantly elevated (at least P < 0.05; Student-Newman-Keul multiple-comparisons [SNK] test) to the CAT antigen compared to the CAT-immunized (84 ± 12 EU) or sham (58 ± 12 EU) group. Thus, both serum IgG and salivary IgA antibody levels to CAT were significantly elevated above those after CAT immunization alone, but antibody to GLU was not elevated above the level after GLU immunization alone.

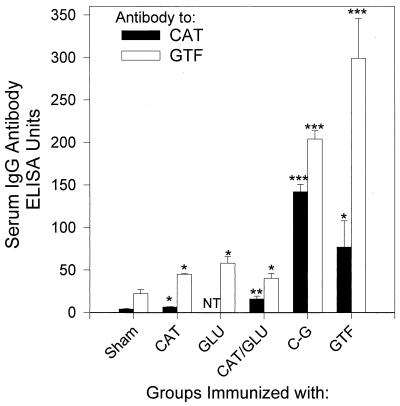

Response to immunization with CAT-GLU compared with response to immunization with GTF or coimmunization.

In experiment 2, the response to immunization with the CAT-GLU construct was compared with the response to immunization with the CAT or GLU construct alone or to CAT/GLU coimmunization or GTF immunization (Fig. 3). As in experiment 1, the CAT-GLU immunization resulted in significant enhancement of the response to GTF. The serum IgG antibody levels to GTF in the CAT-GLU-immunized group were the highest among all groups (except GTF), confirming that the diepitopic construct elicited significantly higher levels of antibody than either of the monoepitopic constructs (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Serum IgG antibody levels to the CAT construct were also significantly higher in the CAT-GLU-immunized group than in the other groups (Fig. 3). In addition, the CAT/GLU-coimmunized group had IgG levels to CAT which were elevated compared with the CAT construct-immunized group. However, immunization with CAT-GLU resulted in significantly greater levels of antibody to GTF or CAT than in the animals coimmunized with the constructs.

FIG. 3.

Serum IgG antibody response to the CAT construct or to GTF from rats immunized with CAT, GLU, CAT/GLU (C/G), the CAT-GLU diepitopic construct (C-G), GTF, or PBS (sham). Data shown are from sera taken 32 days after the first immunization. Bars represent the mean of at least six rats serum IgG antibody levels taken at this time; brackets indicate standard error of the mean. ∗∗∗, the mean antibody levels to GTF of the C-G and GTF groups were statistically significantly greater than that of the sham, CAT, GLU, or C/G group, P < 0.001, as determined by SNK analysis. ∗∗, the mean antibody level of the C/G group to CAT was greater than those of the sham and CAT groups, at least P < 0.02, t test. ∗, the mean antibody level was statistically significantly greater than that for the sham group, at least P < 0.05, t test.

Effect of immunization with CAT-GLU on salivary IgA antibody to GTF or CAT.

Salivary IgA antibody levels to GTF were significantly elevated in the CAT-GLU- and GTF-immunized groups (Table 1). Salivary IgA antibody levels to the CAT construct were significantly higher in the CAT-GLU-immunized group than in the other CAT-immunized or CAT/GLU-coimmunized group in experiment 2. Thus, immunization with CAT-GLU also elicited significantly enhanced IgA antibody in saliva to the CAT component (Table 1), which was significantly greater than that induced by the CAT/GLU mixture (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of salivary IgA antibody responses to GTF or CAT after immunization with the diepitopic construct CAT-GLU or coimmunization with CAT/GLU

| Immunized group | Mean salivary IgA antibody response (EU) ± SEa to:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| GTF | CAT | |

| Sham | 41 ± 7 | 26 ± 8 |

| CAT | 55 ± 13 | 20 ± 5 |

| CAT/GLU | 75 ± 15 | 17 ± 4 |

| CAT-GLU | 102 ± 15∗ | 46 ± 11∗∗ |

| GTF | 179 ± 43∗∗∗ | 36 ± 9 |

Determined on 1:4-diluted saliva from six to seven rats per group. ∗, Significantly different from sham and CAT groups, at least P < 0.05, t test; ∗∗, different from CAT/GLU and/or CAT groups, at least P < 0.05, t test; ∗∗∗, significantly greater than all other groups, at least P < 0.05, SNK test.

Effects of CAT-GLU immunization on proliferative responses to GTF.

Lymphocyte proliferation to GTF was also investigated after coimmunization with monoepitopic constructs or after immunization with the diepitopic construct CAT-GLU (Table 2). Proliferation to GTF by lymphocytes from the GTF-immunized group (P < 0.001), the CAT-GLU group (P < 0.01), and the CAT/GLU group (P < 0.02) was significantly elevated compared to control cultures of lymphocytes without GTF. Proliferation by the GLU-immunized group was also elevated (P < 0.04). Thus, the CAT-GLU and CAT/GLU groups produced significant T-cell responses to GTF.

TABLE 2.

Lymphocyte proliferation to GTF after immunization with the CAT or GLU construct, coimmunization with CAT/GLU, or immunization with diepitopic CAT-GLU construct

| Immunized group | Proliferative response to GTF (mean cpm ± SE)a |

|---|---|

| Sham | 2,679 ± 1,722 |

| CAT | 2,976 ± 1,470 |

| GLU | 3,151 ± 1,060∗ |

| CAT/GLU | 4,836 ± 2,649∗ |

| CAT-GLU | 7,431 ± 4,622∗∗ |

| GTF | 42,461 ± 4,995∗∗∗ |

Tritiated thymidine incorporation in each group (six to seven rats per group) after incubation of lymphocytes with GTF. The value for controls (n = 39) incubated in the absence of GTF was 1,374 ± 266 cpm. ∗, Significantly different from control, at least P < 0.04, t test; ∗∗, significantly different from control, P < 0.01, t test; ∗∗∗, significantly different from all other groups, P < 0.001, SNK test.

Effects of CAT-GLU immunization on GTF function.

We also compared functional inhibition of GTF by serum from immunized animals (Table 3). Serum from animals immunized with GTF or CAT-GLU showed statistically significant inhibition of insoluble glucan synthesis by GTF (Table 3). The CAT-GLU group showed significantly greater inhibitory activity than the CAT/GLU group (experiment 2). Serum from animals immunized with GTF demonstrated significant inhibition of insoluble glucan synthesis catalyzed by GTF. The CAT-GLU group (experiment 3) demonstrated significantly greater inhibition than the GLU, CAT, and sham groups, indicating that the diepitopic construct elicited enhanced inhibition of GTF function.

TABLE 3.

Inhibition of insoluble glucan synthesis catalyzed by GTF

| Immunized group | Mean % inhibition ± SE of glucan incorporation from [14C]glucose-labeled sucrose into IGa

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Expt 2 | Expt 3 | |

| Sham | 2.9 ± 2.4 | 3.5 ± 1.6 |

| CAT | 8.9 ± 2.2 | 6.5 ± 3.0 |

| GLU | 10.4 ± 4.0 | 8.4 ± 2.3 |

| CAT/GLU | 9.9 ± 3.0 | ND |

| CAT-GLU | 12.7 ± 2.6∗ | 18.5 ± 2.1∗∗ |

| GTF | 59.5 ± 1.7∗∗∗ | 60.6 ± 4.3∗∗∗ |

Experiment 2, 32 days after first injection; experiment 3, 23 days after first injection. ∗, significantly different from sham group, at least P < 0.05, t test. ∗∗, significantly different from sham, CAT, and GLU groups, at least P < 0.05, SNK test; ∗∗∗, significantly different from all other groups, P < 0.001, SNK test. ND, not done.

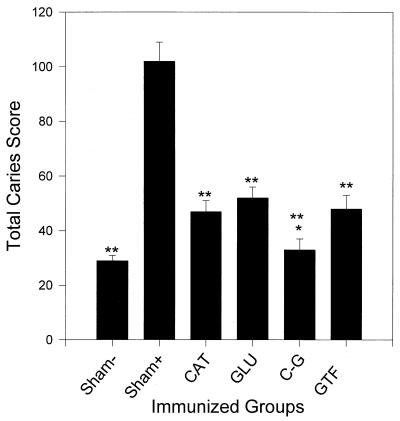

Effects of CAT-GLU immunization on dental caries.

In experiment 3, serum IgG antibody levels to GTF and to CAT were evaluated before infection of control and immunized animals (Table 4). Antibody levels to GTF and CAT after immunization with CAT, GLU with and particularly with CAT-GLU and GTF were significantly elevated in this experiment prior to infection with S. sobrinus. To further assess the functional significance of enhanced levels of antibody to GTF as a result of CAT-GLU immunization, we evaluated the dental caries after CAT or GLU immunization and after CAT-GLU or GTF immunization. Following S. sobrinus infection, the groups immunized with GTF or relevant peptide demonstrated significantly reduced caries compared to sham-immunized infected animals (Fig. 4). Uninfected sham-immunized animals demonstrated the lowest caries scores. The CAT-GLU-immunized group demonstrated significantly lower dental caries scores than either of the other immunized groups.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of serum IgG antibody responses to GTF or CAT in experiment 3 after immunization with CAT-GLU or GTFa

| Immunized group | Mean serum IgG antibody response (EU) ± SEa to:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| GTF | CAT | |

| Sham | 65 ± 9 | 4 ± 1 |

| CAT | 117 ± 24∗ | 10 ± 3∗ |

| GLU | 122 ± 28∗ | 6 ± 1 |

| CAT-GLU | 226 ± 43∗∗ | 207 ± 44∗∗∗ |

| GTF | 355 ± 25∗∗∗ | 13 ± 4∗ |

Serum was taken from nine animals/group prior to infection (day 23). ∗, Significantly different from sham, at least P < 0.05, t test; ∗∗, significantly different from all other groups except GTF, at least P < 0.05, SNK test; ∗∗∗, significantly different from all other groups, at least P < 0.01, SNK test.

FIG. 4.

Dental caries scores of animals immunized and infected (62 days) with S. sobrinus. Bars show the mean total caries scores including smooth and sulcal surfaces and the standard errors for nine rats/group. Differences are statistically significant at the following levels compared with the sham-immunized infected group by one-way analysis of variance and SNK test: ∗∗, P < 0.001 compared to the sham-immunized and infected (Sham+) group; ∗, at least P < 0.05 compared to the CAT or GLU group by SNK test.

DISCUSSION

In these experiments, we found that serum IgG antibody to GTF was significantly elevated after immunization with the synthetic diepitopic construct CAT-GLU. The antibody levels to GTF after immunization with CAT-GLU exceeded those after immunization with the monoepitopic peptide constructs tested (CAT or GLU) that had been previously shown to confer protection from experimental dental caries (30). Such antibody might be considered a surrogate of potential protective effects. Immunization with CAT-GLU also induced salivary IgA antibody to GTF and produced significant T-cell proliferative responses to GTF. The CAT construct itself did not elicit significant T-cell proliferation (31). Antibodies elicited by immunization with the CAT-GLU diepitopic construct demonstrated significant functional inhibition of the ability of GTF to synthesize insoluble glucan from sucrose (approximately 13 to 19% [Table 3]). The CAT-GLU diepitopic construct was more efficient in eliciting an immune response to GTF than either of the monoepitopic constructs tested and also was more effective than coimmunization with the same synthetic peptide constructs. The combination of T- and B-cell epitopes on the same construct appears to satisfy host requirements for linked recognition to generate response to these epitopes. The appearance of these epitopes on the same molecule seems to greatly enhance the immune response to the parent GTF molecule. Simultaneous expression of T- and B-cell epitopes on the same carrier may enhance the antibody response by facilitating direct T-cell–B-cell interaction (2). Thus, the T-cell epitope presented by antigen-presenting cells may activate a T cell to provide bystander help to adjoining B cells producing antibody to the GTF enzyme epitopes (22). Alternatively, and more likely, a mature specific B cell may recognize the B-cell epitope peptide (CAT) portion of the diepitopic construct. This B cell may present both the B-cell epitope peptide and the T-cell epitope peptide, each in association with MHC class II molecules directly to a specific T cell for the production of membrane-bound and secreted cytokine molecules that activate the B cell (10). Also, MHC class II molecules on naive B cells can directly bind diepitopic peptide constructs and present these to antigen-specific T cells (8).

T- and B-cell epitopes combined as a MAP system are efficient immunogens (14). Furthermore, the response to epitopes on the same molecule is far greater than to the same epitopes administered together on separate molecular constructs (3, 21, 22). The construct containing branched complementary peptides from the two major regions of functional significance of GTF gives rise to antibody with potent activity to limit GTF function. Branched synthetic peptide constructs containing T- and B-cell determinants elicit higher antibody levels than the same determinants in a linear conformation (9). This may be attributed to the more efficient presentation of branched synthetic peptide constructs than linear synthetic peptide constructs by dendritic cells and naive B cells to specific T cells and to the resistance of branched constructs to degradation by serum proteases (8). Above, we have explored the necessity for contributions from T- and B-cell epitopes which are required to greatly enhance antibody to a major catalytic site of the enzyme (18). It is conceivable that functional inhibition and in vivo protection can be attributed to the antibody initiated by a diepitopic construct which in particular resulted in increased antibody to CAT and also to the parent GTF molecule. The contiguous and branched nature of these functional epitopes on the same MAP construct which led to increased antibody to important enzyme sites could account for a portion of the enhanced functional inhibition. The binding of antibody to two major functional domains of GTF might be expected to result in potentiated inhibition of enzyme function. The existence of such functional inhibition would appear to render protection from experimental dental caries. However, the degree of inhibition of insoluble glucan synthesis by serum from animals immunized with the CAT-GLU construct is lower than that demonstrated by serum from animals immunized with GTF (Table 3). Nevertheless, protective effects were still observed (Fig. 4). Consideration of increasing the degree of glucan synthesis inhibition raises the possibility of inclusion of additional epitopes to form multiepitopic vaccines which may result in induction of antibody to further inactivate the enzyme. In addition to the CAT and GLU epitopes, we have supported the identity of several catalytic domain regions which when expressed as monoepitopic peptide constructs gave rise to antibody mediating inhibition of GTF activity and/or protection from experimental dental caries (23, 24). These catalytic domain peptides, such as AND (24) and HDS (23), might be considered for inclusion in multiepitopic vaccines. While such multiepitopic vaccines are conceptually quite promising, it is difficult to synthesize more than a diepitopic MAP construct. Novel strategies will have to be explored to determine the full potential of multiepitopic combinations of mutans streptococcal epitopes as subunit vaccines to interfere with dental caries infection.

In this study, we examined the effects of sera from immunized animals on GTF from S. sobrinus. Among the mutans streptococci of humans, S. mutans is known to be most frequently isolated (13). While it would have been of interest to examine the effects of the sera on S. mutans GTF in these experiments, we have investigated this question previously (31). Serum antibody elicited by immunization with S. sobrinus GTF or with CAT or GLU constructs significantly inhibited soluble glucan synthesis by S. mutans GTF to levels similar to those in serum from S. mutans GTF-immunized animals (31). Therefore, it seems reasonable to consider that similar cross-inhibitory effects on S. mutans GTF might also be observed after immunization with the diepitopic construct.

Recently it has been demonstrated that the T- and B-cell viral synthetic epitopes from hemagglutinin of the PR8 influenza virus, although not immunogenic by themselves, were immunogenic when assembled as a contiguous dipeptide (3). Also, mice primed with PR8 virus developed significant antiviral neutralizing antibodies after challenge with the T-B dipeptide. It was suggested that the contiguity of T- and B-cell epitopes might provide sufficient signaling to trigger T-cell–B-cell cooperation in vivo. T- or B-cell epitopes alone were unable to efficiently stimulate T and B memory cells.

In a previous study of coimmunization with a mixture of the CAT and GLU epitopes (33), which were presented as a covalently linked diepitopic construct in the present investigation, we suggested that the basis of increased antibody to a B-cell epitope (CAT) when mixed with a peptide containing a T-cell epitope (GLU) could be attributed to bystander help from cytokines of specific GLU T cells found near the presenting cells. In the experiments described herein, with the contiguous T- and B-cell epitopes, B-cell recognition of CAT in particular on the diepitopic moiety can result in receptor-mediated endocytosis and separate MHC class II-associated display of CAT and GLU. Linked recognition of MHC-GLU by an antigen-specific armed T cell and CD40-CD40 ligand engagement can give rise to activation of CAT-specific B cells (10). The hypothesis suggests that a diepitopic construct initiating linked recognition would induce elevated reactivity with the B-cell epitope (CAT) and conceivably with portions of the parent GTF molecule. Also, the direct T-cell–B-cell interaction indicates that antibody levels to the parent compound would be higher after immunization with the diepitopic construct than after coimmunization with a mixture of epitopes enhancing B-cell activation through bystander T-cell effects. Thus, in the experiments described herein, immunization with the CAT-GLU diepitopic construct gave rise to significantly greater antibody levels than after coimmunization with the components. The diepitopic construct synthesized and tested affirms the importance of combining relatively contiguous T- and B-cell epitopes in a variety of methods. Recently such subunit diepitopic peptides have generated viral neutralizing antibodies (3) and provided immune reactivity with the major merozoite surface protein of Plasmodium falciparum (20).

Our strategy has been to use peptide portions from functionally significant regions of GTF (CAT and GLU) individually and in combination as monoepitopic and now as diepitopic subunit vaccine candidates. Herein the diepitopic constructs from functionally significant regions also contained T- and B-cell epitopes (31) from different portions of GTF. The diepitopic structures so constructed had profound immunogenicity, inducing significant immune response which interfered with GTF-mediated glucan synthesis in vitro and protecting rodents from experimental dental caries. Thus, this approach has great promise for the design of effective subunit dental caries vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant DE-04733 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

We thank William King for preparation of GTF and Jan Schafer for expert secretarial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Babbitt B P, Allen P M, Matuseda E, Haber G, Unanue E R. Binding of immunogenic peptides to Ia histocompatibility molecules. Nature (London) 1985;31:359–361. doi: 10.1038/317359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau J, Bazan F, Blanchard D, Briere F, Galizzi J P, Vankooten C, Liu Y J, Rousset F, Saeland S. CD40 antigen and its ligand. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:881–922. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brumeanu T-D, Casares S, Bot A, Bot S, Bona C A. Immunogenicity of a contiguous T-B synthetic epitope of the A/PR/8/34 influenza virus. J Virol. 1997;71:5473–5480. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5473-5480.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colby S M, Russell R R B. Sugar metabolism by mutans streptococci. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;83:805–885. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.83.s1.9.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devulapalle K S, Goodman S D, Gao Q, Hemsley A, Mooser G. Knowledge-based model of a glucosyltransferase from the oral bacteria group of mutans streptococci. Protein Sci. 1997;6:2489–2493. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devulapalle K S, Mooser G. Subsite specificity of the active site of glucosyltransferases from Streptococcus sobrinus. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11967–11971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edelstein B L, Douglass C W. Dispelling the myth that 50 percent of US school children have never had a cavity. Public Health Rep. 1995;110:522–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzmaurice C J, Brown L E, Kronin V, Jackson D C. The geometry of synthetic peptide-based immunogens affects the efficiency of T cell stimulation by professional antigen presenting cells. Int Immunol. 2000;12:527–535. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzmaurice C J, Brown L E, McInerney T L, Jackson D C. The assembly and immunological properties of non-linear synthetic immunogens containing T cell and B cell determinants. Vaccine. 1996;14:553–560. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00217-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foy T M, Aruffo A, Bajorath J, Bulhmann J E, Noelle R J. Immune regulation by CD40 and its ligand GP 39. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:591–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamada S, Slade H D. Biology, immunology, and carogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol Rev. 1980;44:331–350. doi: 10.1128/mr.44.2.331-384.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaste L M, Selwitz R H, Oldakowski R J, Brunelle J A, Winn D M, Brown L J. Coronal caries in the primary and permanent dentition of children and adolescents 1–17 years of age: United States, 1988–1991. J Dent Res. 1996;75(Special no.):631–641. doi: 10.1177/002203459607502S03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loesche W J. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:353–380. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.353-380.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu Y A, Clavijo P, Galantino M, Shen Z Y, Liu W, Tam J P. Chemically unambiguous peptide immunogen: preparation, orientation and antigenicity of purified peptide conjugated to the multiple antigen peptide system. Mol Immunol. 1991;28:623–630. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(91)90131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma J K-C, Smith R, Lehner T. Use of monoclonal antibodies in local passive immunization to prevent colonization of human teeth by Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1274–1278. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.5.1274-1278.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacGregor E A, Jespersen H M, Svenssen B. A circularly permuted α-amylase type αβ barrel structure in glucan-synthesizing glucosyltransferases. FEBS Lett. 1996;378:263–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01428-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monchois V, Lakey J H, Russell R R B. Secondary structure of Streptococcus downei GTF-I glucan sucrase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;177:243–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mooser G, Hefta S, Paxton R J, Shively J E, Lee T D. Isolation and sequence of an active-site peptide containing a catalytic aspartic acid from two Streptococcus sobrinus α-glucosyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8916–8922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mooser G, Wong C. Isolation of a glucan-binding domain of glucosyltransferase (1,6-α-glucan synthase) from Streptococcus sobrinus. Infect Immun. 1988;56:880–884. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.4.880-884.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parra M, Hui G, Johnson A H, Berzofsky J A, Roberts T, Quakyi I A, Taylor D W. Characterization of conserved T- and B-cell epitopes in Plasmodium falciparum major merozoite surface protein 1. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2685–2691. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2685-2691.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Partidos C D, Obeid O E, Steward M W. Antibody responses to nonimmunogenic synthetic peptides induced by co-immunization with immunogenic peptides. Immunology. 1992;77:262–266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw D M, Stanley C M, Partidos C D, Steward M W. Influence of the T-helper epitope on the titre and affinity of antibodies to B-cell epitopes after coimmunization. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:961–968. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90121-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith D J, Heschel R L, King W F, Taubman M A. Antibody to glucosyltransferase induced by synthetic peptides associated with catalytic regions of α-amylases. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2638–2642. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2638-2642.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith D J, Shoushtari B, Heschel R H, King W F, Taubman M A. Immunogenicity and protective immunity induced by synthetic peptides associated with a catalytic subdomain of mutans group streptococcal glucosyltransferase. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4424–4430. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4424-4430.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith D J, Taubman M A, Holmberg C F, Eastcott J, King W F, Ali-Salaam P. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of a synthetic peptide derived from a glucan-binding domain of mutans streptococcal glucosyltransferase. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2899–2905. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2899-2905.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith D J, Taubman M A, King W. Oral immunization of humans with S. sobrinus glucosyltransferase. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2262–2269. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2562-2569.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith D J, Taubman M A, King W F, Eida S, Powell J R, Eastcott J. Immunological characteristics of a synthetic peptide associated with a catalytic domain of mutans streptococcal glucosyltransferase. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5470–5476. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5470-5476.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi I, Okahashi N, Matsushita K, Tokuda M, Kanamoto T, Munekata E, Russell M W, Koga T. Immunogenicity and protective effect against oral colonization by Streptococcus mutans of synthetic peptides of a streptococcal surface protein antigen. J Immunol. 1991;146:332–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tam J P. Synthetic peptide vaccine design: synthesis and properties of a high density multiple antigen peptide system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:660–666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taubman M A, Holmberg C J, Smith D J. Immunization of rats with synthetic peptide constructs from the glucan-binding or catalytic region of mutans streptococcal glucosyltransferase protects against dental caries. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3088–3093. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3088-3093.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taubman M A, Holmberg C, Smith D J, Eastcott J. T and B cell epitopes from peptide sequences associated with glucosyltransferase function. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;76:S95. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taubman M A, Smith D J. Effects of local immunization with glucosyltransferase fractions from Streptococcus mutans on dental caries in rats and hamsters. J Immunol. 1977;118:710–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taubman M A, Smith D J, Holmberg C J, Eastcott J W. Coimmunization with complementary glucosyltransferase peptides results in enhanced immunogenicity and protection against dental caries. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2698–2703. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2698-2703.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsumori H, Minami T, Kuramitsu H K. Identification of essential amino acids in the Streptococcus mutans glucosyltransferases. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3391–3396. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3391-3396.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong C, Hefta S A, Paxton R J, Shively J E, Mooser G. Size and subdomain architecture of the glucan-binding domain of sucrose: 3-α-d-glucosyltransferase from Streptococcus sobrinus. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2165–2170. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2165-2170.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]