Key Teaching Points.

-

•

Cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) infection and Twiddler’s syndrome are associated with adverse morbidity and mortality outcomes, with key risk factors including patients having undergone multiple/complex procedures.

-

•

The use of TYRX envelope has been shown in prior studies to reduce the risk of CIED infections as well as Twiddler’s syndrome, although not in the 2 cases we have described.

-

•

In our cases, the use of TYRX has been associated with the formation of yellow viscous fluid, which in turn could promote hypermobility of the device and leads in the pocket and cause Twiddler’s syndrome.

Introduction

Cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) infection occurs in 1%–4% of all procedures and remains a feared complication.1, 2, 3, 4 It is associated with adverse mortality and morbidity outcomes with significant healthcare expenditure and is of particular concern at time of generator replacements or for patients considered at higher risk of infection.5, 6, 7

The TYRX absorbable antibacterial envelope (Medtronic, Mounds View, MN) was designed to reduce infection rates as an adjunct to careful operative technique. Constructed of a multifilament mesh coated by a polymer containing rifampin and minocycline, the large pore mesh envelope breaks down and is fully absorbed into the body at approximately 9 weeks, while eluting the antibiotics. Minimum inhibitory concentrations within the pocket can be reached in 2 hours following implant and maintained for at least 7 days.8 The primary objective of minimizing infection with its antimicrobial property was demonstrated in the World-wide Randomized Antibiotic Envelope Infection Prevention (WRAP-IT) trial.9

A secondary indication for its use is securing the CIED into the desired position, preventing excessive movement that can contribute to lead retraction/dislodgement of the leads within the pocket.10 Mechanisms for this phenomenon have been classified as Reel, Ratchet, and Twiddler’s syndrome.11 Complications associated with the TYRX envelope have scarcely been reported. We present 2 cases where lead retraction and Twiddler’s syndrome phenomena have occurred despite its use, together with finding unusual and unexpected pocket fluid.

Case report

Case 1

A 73-year-old white woman with a nonischemic cardiomyopathy underwent single-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation as primary prevention in 2011. Her body mass index was 33. This lead was repositioned a year later because of late dislodgement.

Elective generator replacement was undertaken in 2019. Since the initial implantation, left bundle branch block (QRS duration 153 ms) had developed and, in addition, increasing high-frequency noise on the ICD lead was noted. As a result, ICD system extraction and reimplantation with a cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D) was undertaken in January 2020. The procedure was uncomplicated; however, the atrial lead recurrently displaced, requiring reintervention, and was replaced. Given the early reintervention, a TYRX envelope was used. The suture sleeves were checked and were secured on the lead and on the prepectoral fascia; the generator was also sutured to the prepectoral fascia. There was no wound issue and normal lead parameters on subsequent follow-up.

Phrenic nerve stimulation occurred in February 2021, which had not previously been an issue. Despite having attempted electrical reprogramming, phrenic nerve capture continued. Her chest radiograph demonstrated evidence of macro lead dislodgement and retraction (Figure 1) and device interrogation showed a marked increase in the left ventricular lead impedance and threshold. Her left ventricular ejection fraction and symptomatic status remained unchanged despite CRT support. A decision was made to simplify her CIED system, extract the CRT-D, and reimplant with a single-chamber ICD only, which was undertaken a month later. There had been no clinical suspicion for infection, the pocket appearing normal, and no evidence systemically of infection.

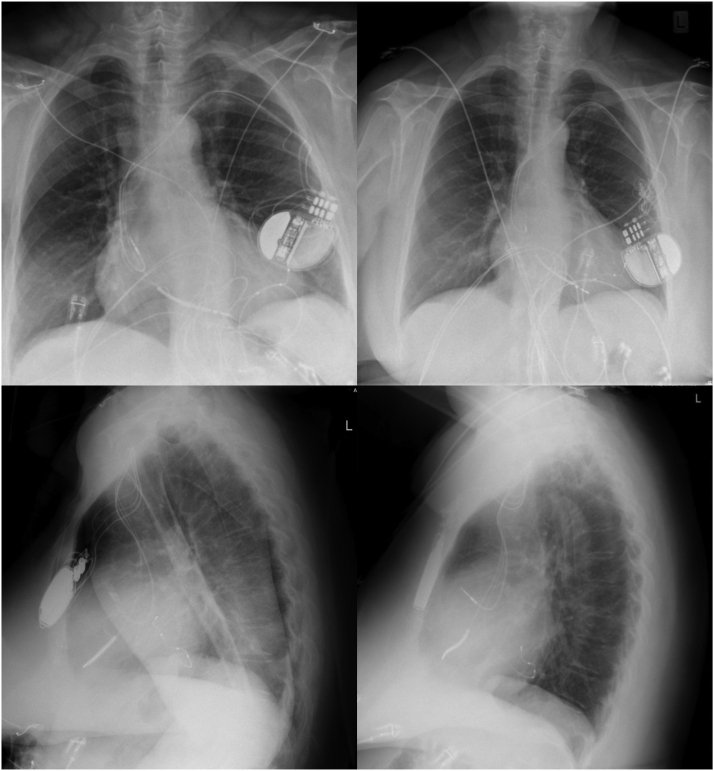

Figure 1.

Case 1: Chest radiographs showing device and leads positioning immediately after implant (left) and evidence of Twiddler’s syndrome 3 weeks later (right).

At this procedure, yellow viscous fluid in the pocket was seen together with tangled leads (Figure 2). The system was extracted entirely. None of the pocket tissue biopsy swabs or device or lead specimens returned positive direct culture, although results at 6 weeks with enrichment culture noted Micrococcus luteus and Corynebacterium species isolated on 1 specimen only. This was managed as an incidental finding of uncertain clinical significance. No antimicrobial treatment was given. A right-sided single-chamber ICD was implanted, and no further problems have been noted during the follow-up to date.

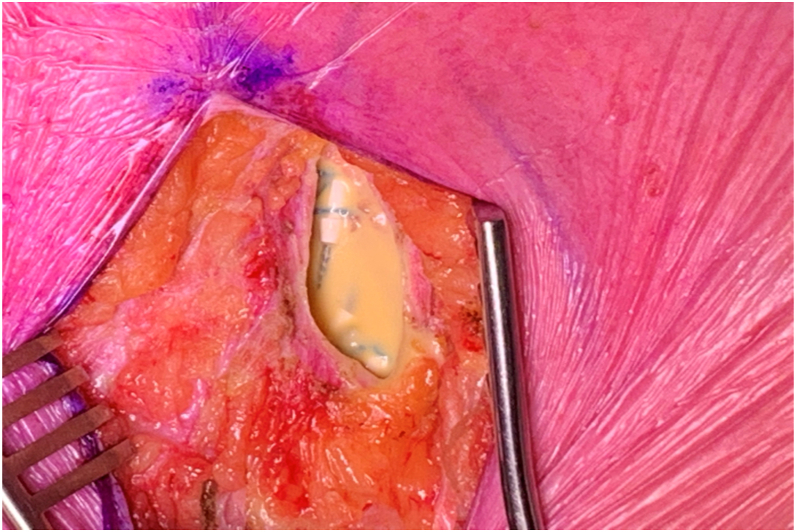

Figure 2.

Case 1: Yellow viscous fluid seen in the device pocket during lead extraction.

Case 2

A 55-year-old white woman presented with disseminated, progressive nodular sarcoidosis with recurrent ventricular tachycardia. Sotalol was commenced and she underwent a secondary-prevention dual-chamber ICD implantation in February 2007 with Medtronic Sprint Fidelis ICD lead. Her body mass index was 31.

In 2013 she required a prolonged hospitalization for treatment of ventricular tachycardia (VT) and she was given infliximab infusions in addition to her 20 mg oral prednisone immunosuppression as well as standard cardiac treatments. Her cardiac medications at the time included metoprolol and candesartan. Normal lead parameters and appropriate ICD function was noted during the storm and there was no evidence of infection seen.

Further VT storm occurred in 2018. Despite evidence of active cardiac sarcoid on a positron emission tomography / computed tomography scan, immunosuppressive and antiarrhythmic therapy did not settle her ventricular arrhythmias. Her therapy included methylprednisolone, prednisone, methotrexate, and infliximab in conjunction with high-dose beta blocker and amiodarone. As a result she underwent VT ablation, which included bipolar ablation across the basal anterior interventricular septum. This combination of therapy suppressed the ventricular arrhythmias.

In January 2020 she required elective ICD generator replacement for battery depletion. At this time chronic immunosuppressive therapy included prednisone and methotrexate. Her left ventricular ejection fraction remained 30%–35%. A TYRX envelope was used to reduce her risk of CIED related infection. Her generator was not sutured to the fascia.

At follow-up 2 months post generator change, repeat chest radiography showed her leads to have become entangled within the pocket (Figure 3). There was no clinical suspicion for infection. She underwent elective ICD extraction in October 2021. Given the progression cardiac condition and previous treatments, there was concern for future atrioventricular conduction abnormalities; therefore reimplantation with CRT-D was planned.

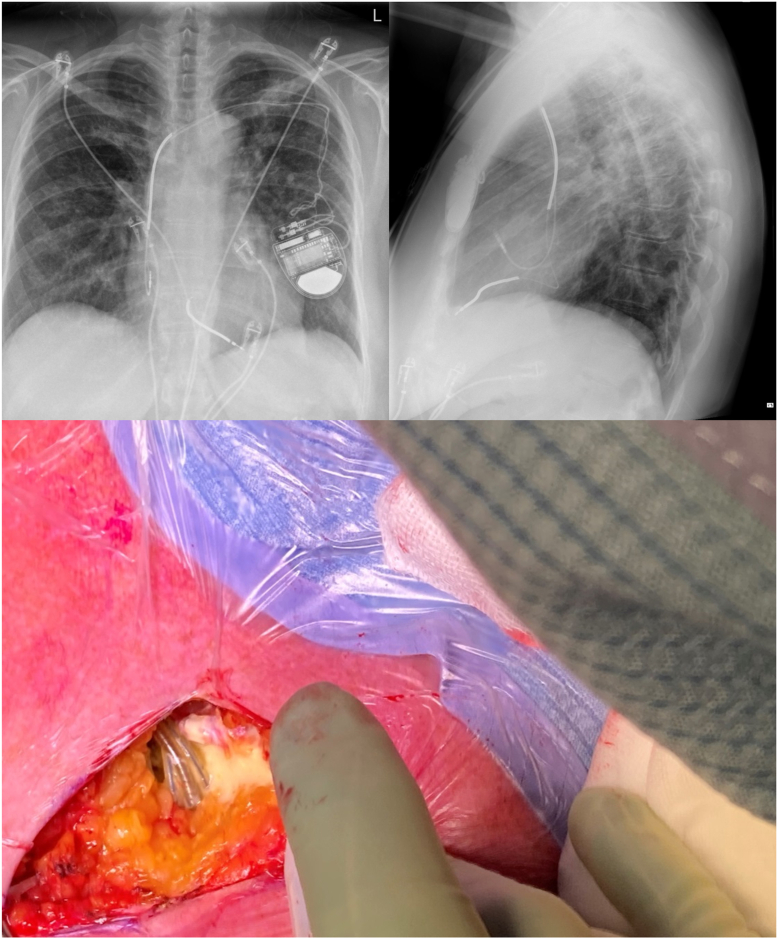

Figure 3.

Case 2: Chest radiographs showing evidence of Twiddler’s syndrome (top) and yellow viscous fluid seen in the pocket during lead extraction (bottom).

Intraprocedurally, there was yellow viscous fluid within the device pocket (Figure 3), but otherwise no clinical evidence of infection. There was no subsequent microorganism grown from the pocket swabs, biopsies, leads, generator, or fluid. She underwent ipsilateral CRT-D implantation during this same procedure using the same prepectoral pocket. The postprocedure period was unremarkable, with good wound healing, and there has been no concern for infection during subsequent clinical follow-up.

Discussion

The TYRX absorbable antibacterial envelope is primarily indicated as an adjunct to reduce the risk of CIED infection. It is also promoted as a method to improve device stabilization within the pocket to reduce the risk of migration, erosion, and Twiddler’s syndrome.10

We present 2 cases where Twiddler’s syndrome occurred despite the use of TYRX. We suspect the observed unusual yellow viscous fluid relates to the degradation of TYRX. The viscous fluid could potentially act as a lubricating medium that in turn could promote device mobility and subsequent lead retraction to occur within the CIED pocket. Both cases had yellow viscous fluid present within the pocket and no clinical evidence of pocket infection. Furthermore, both had procedures with this finding more than a year after the procedure in which TYRX had been implanted. Both patients had well-established CIED pockets, and neither underwent capsulectomy at the time of the procedure when TYRX was used.

Both cases had procedures performed by experienced operators; both patients were female without anatomical issues or previous surgery in the ipsilateral arm or breast. Thus we speculate the most likely cause of the yellow viscous fluid is the failure of complete absorption of the components of the TYRX envelope. In retrospect, chemical analysis would likely have been helpful in clarifying its etiology. If a similar type of fluid is encountered in future we recommend this be undertaken. We suspect this to have been a consequence of the envelope being implanted into mature, fibrous, and therefore relatively avascular pockets. The subsequent presence of fluid allowed the device generator and leads to be more mobile (hypermobile) within the pocket. We hypothesize that, over time, this increased mobility enhanced the ability of the leads to become dislodged and retracted.

These particular issues have not previously been reported as outcomes in the literature, to our knowledge. The WRAP-IT trial did not find any difference in the non-infection-related complications between the control and TYRX groups, noting that lead dislodgement rates were similar.

Conclusion

These cases describe Twiddler’s syndrome despite the use of the TYRX envelope in 2 women with complex CIED histories and multiple prior procedures. This was associated with a yellow, sterile fluid within the pocket. We speculate this fluid was related to the TYRX envelope. In turn, we also speculate this fluid may have led to Twiddler’s syndrome by allowing greater movement of the generator and leads. This association does not prove causation, though it does generate a hypothesis that we urge be considered in future registry and clinical trial data of this product.

Footnotes

Funding Sources: None.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest to declare for all authors.

References

- 1.Han H.C., Hawkins N.M., Pearman C.M., Birnie D.H., Krahn A.D. Epidemiology of cardiac implantable electronic device infections: incidence and risk factors. Europace. 2021;23:iv3–iv10. doi: 10.1093/europace/euab042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clementy N., Carion P.L., de Leotoing L., et al. Infections and associated costs following cardiovascular implantable electronic device implantations: a nationwide cohort study. Europace. 2018;20:1974–1980. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polyzos K.A., Konstantelias A.A., Falagas M.E. Risk factors for cardiac implantable electronic device infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2015;17:767–777. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krahn A.D., Longtin Y., Philippon F., et al. Prevention of arrhythmia device infection trial: The PADIT Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3098–3109. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sohail M.R., Henrikson C.A., Braid-Forbes M.J., Forbes K.F., Lerner D.J. Mortality and cost associated with cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1821–1828. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed F.Z., Fullwood C., Zaman M., et al. Cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) infections are expensive and associated with prolonged hospitalisation: UK retrospective observational study. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eby E.L., Bengston L.G.S., Johnson M.P., Burton M., Hinnenthal J. Economic impact of cardiac implantable electronic device infections: cost analysis at one year in a large U.S. health insurer. J Med Econ. 2020;23:698–705. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2020.1751649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kay G., Eby E.L., Brown B., et al. Cost-effectiveness of TYRX absorbable antibacterial envelope for prevention of cardiovascular implantable electronic device infection. J Med Econ. 2018;21:294–300. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1409227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarakji K.G., Mittal S., Kennergren C., et al. Antibacterial envelope to prevent cardiac implantable device infection. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1895–1905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osoro M., Lorson W., Hirsch J.B., Mahlow W.J. Use of an antimicrobial pouch/envelope in the treatment of Twiddler's syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;41:136–142. doi: 10.1111/pace.13259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez-Acosta L., Romero Garrido R., Farrais-Villalba M., Hernández Afonso J. Reel syndrome: a rare cause of pacemaker malfunction. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]