Abstract

The liver exhibits the highest recovery rate from acute injuries. However, in chronic liver disease, the long-term loss of hepatocytes often leads to adverse consequences such as fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer. The Wnt signaling plays a pivotal role in both liver regeneration and tumorigenesis. Therefore, manipulating the Wnt signaling has become an attractive approach to treating liver disease, including cancer. Nonetheless, given the crucial roles of Wnt signaling in physiological processes, blocking Wnt signaling can also cause several adverse effects. Recent studies have identified cancer-specific regulators of Wnt signaling, which would overcome the limitation of Wnt signaling target approaches. In this review, we discussed the role of Wnt signaling in liver regeneration, precancerous lesion, and liver cancer. Furthermore, we summarized the basic and clinical approaches of Wnt signaling blockade and proposed the therapeutic prospects of cancer-specific Wnt signaling blockade for liver cancer treatment.

Keywords: WNT signaling pathway, Liver regeneration, Liver diseases, Hepatocellular carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Liver regeneration has been extensively studied [1-3]. In vivo studies have shown that partial hepatectomy or chemical injury activates extracellular and intracellular signaling pathways, leading to liver regeneration. Hepatocyte loss during chronic liver diseases triggers compensatory proliferation of the surviving hepatocytes [4-6]. Apart from liver regeneration in physiological conditions, genotoxic risk factors might lead them to convert to neoplasia. Hepatitis virus, alcohol abuse, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and aflatoxin-B1 exposure are also the main etiological factors to induce the development of precancerous lesions in the liver. Liver cancer is one of the top 10 lethal cancers worldwide. Its estimated death rate in 2021 is 6% in males and 4% in females [7]. Liver cancer consists of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), hepatoblastoma (HB), and several other rare tumors (angiosarcoma, intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct, and mucinous cystic neoplasm). HCC is the most common primary liver cancer frequently developed with chronic liver disease, such as cirrhosis caused by hepatitis virus infection [8].

Among various signaling pathways associated with liver biology [9-12], Wnt signaling is involved in all stages of liver disease progression, from liver injury to inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and tumorigenesis. Several Wnt ligands are secreted by various hepatic cells, including hepatocytes, stellate cells, Kupffer cells, biliary epithelial cells, and sinusoidal endothelial cells [13-16]. Based on the oncogenic roles of Wnt signaling in cancer, several components and regulators of Wnt signaling have been proposed as the druggable targets to improve the current therapeutic efficacy in the liver cancer treatment [17].

Herein, we review the roles of Wnt signaling in liver regeneration and liver tumorigenesis and the therapeutic targets of Wnt signaling in liver cancer treatment.

Wnt SIGNALING

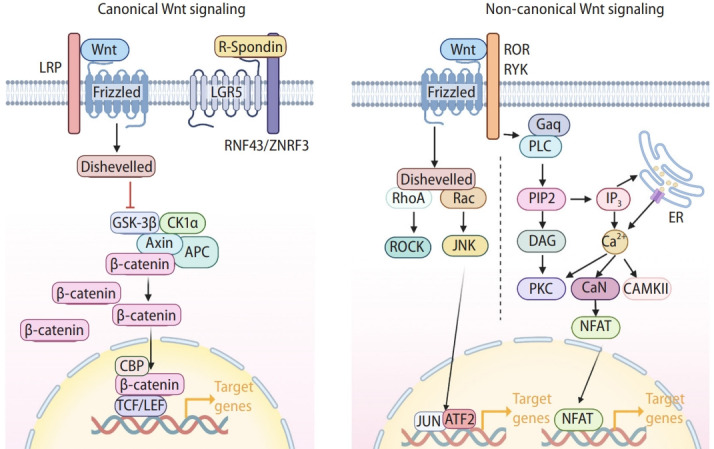

Wnt signaling is evolutionarily conserved and orchestrates various cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, polarity, stemness, and lineage plasticity [18,19]. Consequently, Wnt signaling plays a pivotal role in organogenesis, tissue homeostasis, tissue regeneration, and tumorigenesis [20-25]. The Wnt signaling is triggered by the binding of the Wnt ligands to the frizzed (FZD) receptors. The mammals have 19 Wnt ligands and 10 FZD receptors [26], resulting in the complexity and specificity in Wnt signaling activation. Based on the involvement of β-catenin, a key component of Wnt signaling, Wnt signaling is generally classified into canonical (β-catenin-mediated) and non-canonical (β-catenin-independent) Wnt signaling (Fig. 1). In the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway, the protein destruction complex (casein kinase 1 [CK1], glycogen synthase kinase 3 [GSK3], adenomatous polyposis coli [APC], and axis inhibition proteins [AXINs]) targets the β-catenin protein for degradation via CKI1 and GSK3-mediated sequential phosphorylation at the N-terminus (Ser-45, Thr-41, Ser-37, and Ser-33) of β-catenin followed by β-TrCP, an E3 ligase, recruitment. Conversely, binding of the canonical Wnt ligands to the FZD receptors and LRP5/6 co-receptors activates dishevelled (DVL), which inhibits the protein destruction complex. As a result, β-catenin protein is stabilized and translocated into the nucleus to transactivate the canonical Wnt target genes by replacing the co-repressors associated with the T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (TCF/LEF) with the co-activators. Non-canonical Wnt signaling pathways include the planar cell polarity pathway (involved in c-Jun N-terminal kinase [JNK] activation, small GTPase activation, and cytoskeletal rearrangement), and the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway (activating phospholipase C [PLC] and protein kinase C [PKC]) [18,19].

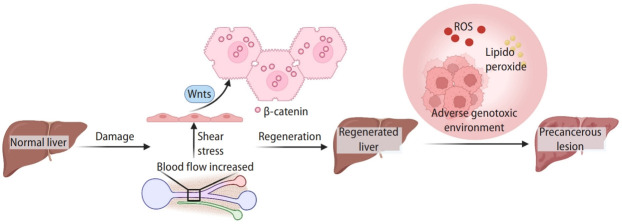

Figure 1.

Wnt signaling. Illustration of canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling. The hallmark of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway is the stabilization and nuclear translocation of β-catenin. In the absence of Wnt ligands, cytoplasmic β-catenin is degraded by the destruction complex (Axin, APC, GSK3β, and CK1α). Upon Wnt ligand binding to Frizzled receptors (FZDs) and LRP, the destruction complex is inhibited, β-catenin protein is stabilized in the cytosol and translocated into the nucleus. Nuclear β-catenin then recruits transcriptional coactivator CREBBP to transactivate target genes in conjunction with TCF/LEF transcription factors. Additionally, FZDs are ubiquitinated by ZNRF3 and RNF43 E3 ligases, which are inhibited by R-spondin binding to LGR5, increasing the cells’ sensitivity to Wnt ligands. In Wnt/PCP signaling, Wnt ligands bind to FZDs or their co-receptors (ROR and RYK) to trigger a cascade reaction, involving the small GTPases RhoA and Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate (Rac), then activating Rho-associated protein kinases (ROCKs) and JUN N-terminal kinases (JNK), respectively. These lead to cytoskeletal rearrangements and/or transcriptional responses such as ATF2. In Wnt/Ca2+ signaling, the activation of phospholipase C (PLC) triggers the release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which promotes the transcription of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) through several intermediate steps. Created with BioRender.com. LRP, lipoprotein receptor-related protein; LGR5, leucine-containing repeat G-protein-coupled receptor 5; RNF43, ring finger protein 43; ZNRF3, zinc and ring finger 3; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; CK1α, casein kinase 1α; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; CBP, CREB binding protein; TCF/LEF, T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor; ROR, receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor; RYK, receptor tyrosine kinase; ARF2, activating transcription factor 2; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; PKC, protein kinase C.

Wnt SIGNALING IN LIVER REGENERATION

Upon partial hepatectomy or acute liver injury, the number of hepatocytes is drastically reduced. Various signaling pathways (epidermal growth factor [EGF], hepatocyte growth factor [HGF], Wnt/β-catenin, and Notch) stimulate the hepatocytes in the G0 phase to proliferate, compensating tissue loss and restoring the physiological functions of the liver [27-29]. During liver regeneration, endothelial cells under shear stress produce Wnts to activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling in hepatocytes. Additionally, the organ precisely senses the size of the regenerating liver and adjusts its size to 100% [2].

Several animal models (rat, mouse, and zebrafish) were utilized for liver regeneration study [30-33]. The partial hepatectomy is the classic strategy to create the murine liver regeneration model [30]. Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)is a frequently used chemical to induce liver injury in rats and mice.34 Meanwhile, several dietary-induced liver injury models are also commonly used [35]. Biliary injury and regeneration can be induced by the 1,4-dihydro-2,4,6-trimethyl-pyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (DDC) diet [35]. Besides murine models, zebrafish emerged as a potent model for drug screening of liver generation [32,33]. Partial hepatectomy, drug-induced liver injury, and nitroreductase-mediated hepatocyte ablation were employed to establish the zebrafish liver injury model [32,33,36,37].

Transient activation of the canonical Wnt signaling is indispensable for liver regeneration (Fig. 2) [13,15,27]. In rat models, overexpressed Wnt1 and nuclear β-catenin are predominantly accumulated in remaining parenchymal cells after 70% partial hepatectomy. The level of β-catenin increased within 5 minutes after hepatectomy, accompanied by its nuclear translocation and subsequent target gene expression for hepatocyte proliferation [27]. Significantly, genetic ablation of β-catenin/Ctnnb1 impairs liver regeneration of mice from partial hepatectomy [38]. The liver-specific Ctnnb1 knock-out (KO) delayed DNA synthesis and hepatocyte proliferation in mice after partial hepatectomy. Conversely, activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling accelerates liver regeneration in the zebrafish model [39]. It was also shown that liver damage upregulated leucine-containing repeat G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) and AXIN2 in the hepatocytes [40]. LGR5 is a marker of actively dividing stem and progenitor cells in Wnt-driven self-renewing tissues [41]. LGR5 interacts with FZD and lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6) to enhance phosphorylation of LRP6, which in turn enhances the Wnt/β-catenin signaling [42]. While Lgr5 is not expressed in healthy adult livers, after liver damage, Lgr5+ cells appear near the bile ducts, consistent with strong activation of the Wnt signaling [41]. AXIN2 is another Wnt downstream target gene transactivated by β-catenin [43]. Like AXIN1, AXIN2 combined with other destruction complex components degrades β-catenin, serving as a negative feedback regulator of the Wnt signaling [44].

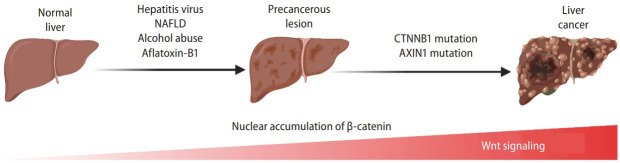

Figure 2.

Wnt signaling in liver regeneration. In normal liver, most hepatocytes are polyploid with random chromosomal deletions. Upon liver injury, the increased narrow portal vein pressure stimulates the initiating signals for liver regeneration. The activation of Wnt signaling is crucial in liver regeneration. Moreover, in chronic liver injury, the ROS and lipid peroxide are the risk factors damaging the reproducing hepatocytes, leading to precancerous lesion development. Created with BioRender.com. ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Other than core components of Wnt signaling, additional regulators of Wnt signaling were implicated in liver regeneration. Recently, our group identified the transmembrane protein 9 (TMEM9) gene as an amplifier of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. TMEM9 is a type I transmembrane protein primarily localized in lysosomes and multivesicular bodies (MVBs). While the ablation of TMEM9 inhibits the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling, β-catenin transactivates TMEM9, leading to hyperactivation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling [45]. Interestingly, TMEM9 is highly expressed in hepatocytes around the central vein (CV) of regenerating liver [46]. TMEM9 hyperactivates Wnt/β-catenin signaling to promote liver regeneration through lysosomal degradation of APC protein [46]. Tmem9 KO impairs CCl4-induced liver regeneration with downregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling [46].

In addition to the role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in regeneration, sustained activation of the Wnt signaling is associated with the progression of chronic liver diseases and liver tumorigenesis (Fig. 2). Additionally, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxide are the risk factors for the development of the precancerous lesion in the liver [47,48]. However, the crosstalk between Wnt signaling and ROS has not been fully revealed in the liver. It was reported that β-catenin can be further stabilized by ROS [49]. Meanwhile, lipid peroxidation products mainly generated by ROS activate the canonical Wnt pathway through oxidative stress [50]. Therefore, it is likely the potential crosstalk between Wnt signaling and ROS might contribute to liver cancer development.

Accumulating evidence suggests that many chronic liver diseases contribute to liver cancer development, described below.

Wnt SIGNALING IN PRECANCEROUS LIVER LESION

Hepatitis virus

Globally distributed hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are the crucial triggers of HCC initiation. Both HBV and HCV can induce chronic infections and are essential pathogenic factors in cirrhosis and liver cancer (Fig. 3) [51,52]. The epidemiological data show that more than 70% of patients with liver cancer have HBV infection, 10–20% have HCV infection, and a significant proportion of patients have both HBV and HCV infection [53-55].

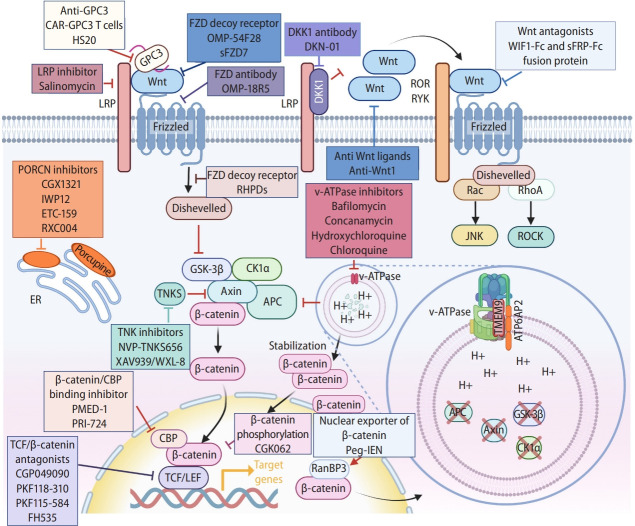

Figure 3.

Wnt signaling in liver cancer. Dynamic activation of β-catenin and Wnt signaling-related gene mutations from risk factor exposure to final liver cancer. With the precancerous lesions induced by hepatitis virus, NAFLD, alcohol assumption, or aflatoxin-B1, genetic and epigenetic alteration (e.g., mutations in the CTNNB1 or AXIN1 genes) lead to the accumulation and nuclear translocation of β-catenin, resulting in initiating liver cancer development. Created with BioRender.com. NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

After infection, the DNA of HBV is integrated into the host genome, inducing genomic instability and transactivation of cancer-related genes, which culminates in the formation of early cancer cell clones. Mechanistically, HBV contributes to HCC development through direct and indirect means [56]. Direct mechanisms include virus mutations, HBV DNA integration, growth regulatory genes activation by HBV-encoded proteins [57]. Indirect mechanisms include the activation of cellular oncogenes associated with HBV DNA integration, genetic instability induced by viral integration or the regulatory protein HBx, and the development of liver disease mediated by immune enhancement due to viral proteins [58].

Both hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) and HBx modulate the expressions of genes involved in Wnt signaling activation. HBsAg activates the transcription factor LEF1 of the Wnt signaling [59]. The X protein encoded by the hepatitis B virus has a vital role in stimulating viral gene expression and replication, critical for maintaining chronic carrier status. HBx, a 17 kDa multifunctional protein, upregulates the expression of Wnt ligands (WNT1 and WNT3), the receptor (FZD2 and FZD7), a component of the destruction complex (GSK3β), E-cadherin, and Wnt1-inducible-signaling pathway protein 1 (WISP1), a suppressor of Wnt antagonists (secreted frizzled-related protein 1 [SFRP1] and SFRP5). On the other hand, the Wnt signaling key components (β-catenin and AXIN1) are highly mutated in HBV-associated HCC. Loss-of-function (LOF) mutations of the AXIN1 are observed in HBV-HCC patients. In HBV and/or HCV-associated HCC patients, the most frequent mutation in the CTNNB1 gene is enriched in the exon 3 encoding the N-terminal phosphorylation sites [60-62]. These aberrantly controlled genes in Wnt signaling subsequently promote and lead to the development of HCC [63-65].

The oncogenic mechanism of HCV in liver cancer is mainly mediated by Wnt/β-catenin signaling hyperactivation via the core protein and two nonstructural proteins, NS3 and NS5A [66]. The core protein (HCV core antigen) is a significant component of HCV. It regulates hepatocyte transcription and promotes Wnt/β-catenin signaling by upregulating Wnt ligands (WNT1 and WNT3A), FZD receptors, and LRP5/6 [67,68]. Additionally, at the early stage of HCV infection, the secreted Wnt antagonists, SFRP2 and Dickkopf 1 (DKK1), are downregulated by their promoter hypermethylation [69,70]. HCV core protein also promotes hypermethylation of the CDH1 gene promoter region [71], destabilizing the cadherin-catenin-actin complex for β-catenin release and activation [72]. NS5A stabilizes β-catenin via activating phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT, leading to GSK3β inactivation followed by inhibiting the protein-destruction complex-mediated β-catenin degradation for Wnt target gene activation. At the early stage of viral infection, HCV-activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling also promotes liver fibrosis by enhancing the activation and survival of hepatic stellate cells [17,73,74].

Alcohol abuse

Alcohol is a well-known risk factor for liver cancer. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is a chronic liver disease caused by long-term alcohol consumption (Fig. 3). ALD is characterized by the fatty liver at the beginning, then progressed to alcoholic hepatitis, liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis, which is pathologically associated with the precancerous lesions of HCC. In vivo, ethanol (EtOH) is metabolized into the reactive metabolite acetaldehyde, promoting liver tumorigenesis. Mice administered with the chemical carcinogen, diethylnitrosamine (DEN), for 7 weeks and the subsequent EtOH feeding for 16 weeks exhibited the increased total number of cancer foci and liver tumors [75]. Also, these tumors showed a 3- to 4-fold increase in the expression of proliferation markers and an increased expression of β-catenin, compared to non-tumor hepatocytes [75]. In a rat model of chronic liver disease, EtOH-treated liver was accompanied by the increased proliferation of hepatocytes, depletion of retinol and retinoic acid storage, augmented expression of phospho-GSK3β at the cell membrane, significant upregulation of soluble Wnt ligands (Wnt2 and Wnt7a), accumulation of nuclear β-catenin, and upregulation of β-catenin target genes (cyclin D1/CCND1, c-Myc/MYC, WISP1, and matrix metallopeptidase [MMP7]). These data suggest that long-term EtOH consumption activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling and increases hepatocyte proliferation, promoting liver tumorigenesis [75]. Additionally, ROS accumulation, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-ĸB)-dependent vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 upregulation, and activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling also contribute to EtOH-induced liver tumorigenesis [76-80].

NAFLD

The increasing prevalence of NAFLD was caused by an over-nourished lifestyle [81,82]. NAFLD is characterized by fat accumulation in the liver, evolving to end-stage liver diseases such as cirrhosis and HCC (Fig. 3) [83]. The main risk factors of NAFLD include central obesity, overnutrition, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome [84]. In severe NAFLD, many tissue repair-related genes (TMEM204, FGFR2, matrix molecules, and matrix remodeling factors) were hypomethylated at their promoters and overexpressed. Conversely, genes in specific metabolic pathways (lipid metabolism, cytochrome P450 family, multidrug resistance, and fatty acid anabolic pathways) were hypermethylated and silenced [85]. Hyperinsulinemia is one of the risk factors of NAFLD [86]. SOX17 plays a vital role in regulating insulin secretion. Sox17 KO mice display high susceptibility to high-fat diet-induced hyperglycemia and diabetes [87]. SOX17 directly interacts with the TCF/LEF transcription factor to repress the transcription of Wnt signaling target genes. The methylation of the SOX17 promoter is a frequent event in human cancers. Epigenetic silencing of SOX17 contributes to the aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling [88], accelerating progression from NAFLD to HCC. Besides, β-catenin inhibits the expression of CCAAT enhancer-binding protein α (CEBPA) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARG), which in turn inhibits the preadipocyte differentiation [89]. As the co-receptor of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling, LRP6 induces lipid accumulation in the liver via insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1)/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)/sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor (SREBF) 1/2 signaling. Intriguingly, inhibiting the non-canonical Wnt signaling reduces lipid accumulation and inflammation [90]. Therefore, while reducing the effects of NAFLD risk factors, inhibition of the Wnt signaling is also essential for attenuating the development of NAFLD and preventing the initiation of HCC.

Aflatoxin-B1 exposure

Among the aflatoxins, aflatoxin type B1 (AFB1) primarily targets the liver as a highly potent hepatotoxin and hepatocarcinogen (Fig. 3). AFB1 impairs DNA repair processes, resulting in severe DNA mutagenesis, and also inhibits DNA and RNA metabolism. This pathological event ultimately leads to excessive liver lipid accumulation, liver enlargement, bile duct epithelial hyperplasia, and liver cancer. The potency of aflatoxin to cause liver cancer is significantly enhanced in the presence of HBV infection. Under chronic HBV infection, cytochrome P450s could metabolize inactive AFB1 to mutagenic AFB1-8,9-epoxide. Also, the infection leads to hepatocyte necrosis and regeneration, producing oxygen and nitrogen reactive species and increasing the incidence of AFB1-induced mutagenesis [91]. Clinical studies have shown that CTNNB1 mutations are present in approximately one-quarter of HCC in areas with low aflatoxin B1 exposure. Interestingly, these CTNNB1 mutations were similar to those previously reported in the human HCC [92].

Wnt SIGNALING IN LIVER CANCER

HCC

HCC is a common and fatal malignancy worldwide [93]. Regardless of the risk factors mentioned above, aberrant hyperactivation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is observed in 95% of HCCs [94]. The most common genetic mutations of the Wnt signaling in HCC are the gain-of-function mutations in the CTNNB1 gene encoding β-catenin [61,95], which is somewhat distinct from colorectal cancer where Wnt/β-catenin signaling hyperactivation is mainly driven by the APC gene inactivation [96]. Missense mutations of CTNNB1 exon 3 were observed in 18.1% of HCC cases. Missense mutations at codons 32, 33, 38, or 45 of the CTNNB1 gene lead to the unphosphorylation of the N-terminus of β-catenin for its stabilization, nuclear translocation, and target gene transactivation [60]. Secondly, the LOF mutations in the AXIN1 gene were observed in 5–19% of HCC cases [97]. CTNNB1 and AXIN1 mutations occur in patients with advanced HCC (Fig. 3) [98-100]. Importantly, hyperactivation of the Wnt signaling is considered a hallmark of advanced HCC [101]. It should also be noted that mutations in the CTNNB1 and AXIN1 genes lead to different HCC subtypes accompanied by distinct clinical and pathological features. CTNNB1 mutations are associated with less aggressive HCC, including chromosomally stable and highly differentiated tumors [102], with a better prognosis [95]. In contrast, AXIN1 mutations occur more frequently in more aggressive HCC tumors characterized by hypodifferentiated tumor cells and chromatin instability [102]. Consistently, the HCC tumors with CTNNB1 mutations or AXIN1 mutations showed different target gene expression [61,95,103].

CCA

CCA is ranked as the second most common hepatobiliary cancer after HCC. CCA originates mainly from differentiated bile duct epithelial cells [104]. CCA is often diagnosed at an advanced stage with a poor prognosis. Current chemotherapy has not improved the survival rate of unresectable CCA patients. Clinical and preclinical studies have shown that activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling occurs throughout the initiation and progression of CCA. Wnt ligands (WNT2, WNT7b, and WNT10A) and TCF4 are upregulated in CCA, accompanied by nuclear translocation of β-catenin [105,106]. The progression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) was observed in CCA, represented by the disrupted epithelial cell-cell junctions and mesenchymal characteristics [107-109]. Wnt/ β-catenin signaling is one of the critical pathways promoting the EMT transition [110,111]. In CCA cells, suppression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling increased E-cadherin and downregulated vimentin [112,113], suggesting that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling is associated with EMT during CCA tumorigenesis. β-catenin interacts with E-cadherin to form the cadherin-catenin-actin complex, maintaining epithelial cell adhesion, cytoskeleton, and integrity. During CCA development, the decreased E-cadherin releases β-catenin, resulting in β-catenin accumulation and nuclear translocation [111]. Then, β-catenin activates the transcription of twist, snails, and ZEB1 to induce the EMT process in CCA cells [111].

HB

HB is a rare malignant tumor found in infants and children [114]. The preclinical and clinical studies showed the hyperactivation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in HB. In HB cases, β-catenin was found to be increased in the cytoplasm and nucleus of the tumor cells [115,116]. While CTNNB1 mutations are limited in the exon 3 in embryonal HB, the CTNNB1 mutations in fetal HB encompass exon 3 and 4 [117]. Meanwhile, missense, deletion, or insertion mutations in the AXIN1 gene were detected in 8% of HB cases [118].

MANIPULATING Wnt SIGNALING

Porcupine (PORCN)

PORCN is a membranous protein mainly localized in the endoplasmic reticulum. PORCN mediates the palmitoylation of Wnt ligands, an essential process for Wnt ligands secretion and ligand-frizzled receptor binding [119-121]. Genetic and pharmacological blockade of PORCN reduces palmitoylation and inhibits the secretion of Wnt ligands, suppressing Wnt signaling [122]. The clinical trials showed promising results of PORCN inhibitors in HCC treatment. ETC159, CGX1321, and RXC004 have entered phase I clinical trials, and IWP12 is still in the preclinical studies (Fig. 4) [123]. In mouse models, Porcn KO induces embryonic lethality [124,125]. Porcn inhibition could cause adverse effects on bone homeostasis [126].

Figure 4.

Manipulating Wnt signaling. Illustration of components and processes of Wnt signal transduction as druggable targets for liver cancer treatment. See the text for detail. Created with BioRender.com. GPC3, glypican-3; LRP, lipoprotein receptor-related protein; FZD, frizzed; DKK1, Dickkopf 1; ROR, receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor; RYK, receptor tyrosine kinase; PORCN, porcupine; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; CK1α, casein kinase 1α; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; TCF, T-cell factor; CBP, CREB binding protein; LEF, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor; peg-IFN, pegylated-Interferon-α2a; RanBP3, Ran-binding protein 3.

Wnt ligands

In physiological conditions, Wnt signaling is activated by binding of secreted Wnt ligands to LRP5/6 coreceptors and FZD receptors [127]. Thus, targeting Wnt ligands by chemicals or neutralizing antibodies efficiently inhibits Wnt signaling. Based on the high expression of WNT1 in human HCC cell lines and tissues. Anti-WNT1 neutralizing antibody showed its growth inhibitory effect on HCC cell lines but not on normal hepatocytes, with reduced β-catenin’s transcriptional activity (Fig. 4) [128].

Wnt antagonists

SFRPs, WIFs, and DKKs are the secreted Wnt signaling antagonists [129,130]. SFRP-1 and Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (WIF1) inhibit Wnt signaling by directly binding to Wnt ligands [131]. The fusion proteins WIF1-Fc and SFRP1-Fc were constructed by adding the Fc fragment of human immunoglobulin (Ig) G1 to WIF1 and SFRP1, respectively (Fig. 4) [132]. The fusion proteins exert potent anti-tumor activity by downregulating E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1), cyclin D1, and c-Myc, increasing apoptosis of HCC cells and impairing tumor vascularization. DKK1 was initially considered a β-catenin-dependent tumor suppressor [130,133]. Several studies have shown that DKK1 promotes tumor cell proliferation, which may be due to DKK1-induced endocytosis of LRP and subsequent activation of the Wnt/PCP signaling pathway [134,135]. DKN-01 is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting DKK1 in phase I/II clinical trial for HCC (Fig. 4). Phase I investigated the safety of DKN-01 as a single agent and in combination with sorafenib to treat HCC. Phase II explores the anti-tumor activity and safety of DKN-01 in patients with advanced HCC.

FZD receptors

The FZD receptors are promising therapeutic targets for HCC. The anti-FZD antibody can effectively reduce the HCC tumor growth by blocking the activation of FZD receptors on the Wnt signaling [136]. FZD decoy receptor OMP-54F28 (ipafricept) is a recombinant fusion protein that binds to a human IgG1 Fc fragment of FZD8 [137,138], which acts synergistically with chemotherapeutic agents (Fig. 4) [139]. A phase 1b dose-escalation clinical trial evaluated the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of OMP-54F28 when combined with sorafenib. Secreted FZD7 (sFZD7) is the extracellular domain of FZD7, expressed and purified from Escherichia coli. sFZD7 binding to WNT3 decreased the transcriptional activity of β-catenin/TCF4 and inhibited the growth of HepG2, Hep40, and Huh7 [140]. In combination with doxorubicin, sFZD7 inhibited the expression of c-Myc/MYC, Cyclin D1/CCND1, and Survivin/BIRC5, reduced the phosphorylation levels of AKT and ERK1/2, inhibited the growth of Huh7 xenograft tumors, and acted as a chemosensitizer [140]. OMP-54F28 is entering phase I clinical trials, while sFZD7 remains in preclinical studies (Fig. 4).

FZD antibody OMP-18R5 (vantictumab) is a monoclonal antibody directly binding to FZD receptors, which blocks the binding of Wnt ligands to FZD 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8 [141], which inhibits β-catenin-mediated transactivation (Fig. 4). In patient-derived xenograft models, OMP-18R5 combined with chemotherapeutic agents synergistically inhibited the development of several cancers.141,142 However, like PORCN inhibitors, OMP-18R5 has the same risk of impairing bone homeostasis [143]. In a dose-escalation clinical trial of OMP-18R5, one patient developed bone degeneration, controllable with zoledronic acid. The skeletal toxicity appeared to be manageable and reversible [144].

LRP co-receptors

Salinomycin (SAL), isolated from Streptomyces albus, is a monocarboxylic polyether ionophore antibiotic [145,146]. SAL blocks Wnt-induced LRP phosphorylation and leads to LRP protein degradation, destabilizing the Wnt/FZD/LRP complex and inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Fig. 4) [147]. SAL effectively inhibits β-catenin expression in HepG2/C3a cell line [148]. SAL also inhibits the migration and invasiveness of liver cancer stem cells through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling suppression [149].

Tankyrase (TNKS)

TNKS mediates PARsylation and subsequent degradation of AXIN via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, which in turn disrupts the β-catenin destruction complex [150]. Subsequently, the released β-catenin enters the nucleus to transactivate Wnt target genes [151,152]. TNKS is overexpressed in many cancers, including HCC, gastric cancer, and colorectal cancer [153-155]. The TNKS inhibitors XAV939, WXL-8, and NVP-TNKS656, attenuated Wnt/β-catenin signaling and inhibited the growth of HCC cells (Fig. 4) [155-157]. Moreover, TNKS inhibitors also suppressed HCC metastasis and invasion [157]. However, there are no relevant clinical trials for TNKS inhibitors in HCC.

Nuclear export of β-catenin

As shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1, pegylated-Interferon-α2a (peg-IFN), the first-line therapy for the HCV-infected [158], attenuates the recurrence of HCC (Fig. 4) [159]. Mechanistically, peg-IFN upregulates the expression of Ran-binding protein 3 (RanBP3) [160], which enhances the nuclear export of β-catenin [160]. Thus, it is likely that peg-IFN-induced β-catenin nuclear export is a mechanism delaying HCC and improving survival in HCV patients.

Table 1.

Targeting Wnt signaling in liver cancers

| Agent | Target | Phase | Trial identifier | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DKN-01 | DKK1 | Phase I/II | NCT03645980 | Protein |

| OMP-18R5 | FZD1, 2, 5, 7, and 8 | Phase I | NCT01345201 | Protein |

| sFZD7 | FZD7 | Preclinical | NA | Protein |

| RHPDs | FZD7 | Preclinical | NA | Protein |

| OMP-54F28 | FZD8 | Phase I | NCT02069145 | Protein |

| Salinomycin | LRP5/6 | Preclinical | NA | Natural compounds |

| CGX1321 | PORCN | Phase I | NCT03507998 | Small molecule inhibitors |

| IWP12 | PORCN | Preclinical | NA | Small molecule inhibitors |

| ETC-159 | PORCN | Phase I | NCT02521844 | Small molecule inhibitors |

| RXC004 | PORCN | Phase I | NCT03447470 | Small molecule inhibitors |

| NVP-TNKS656 | Tankyrase | Preclinical | NA | Small molecule inhibitors |

| XAV939/WXL-8 | Tankyrase | Preclinical | NA | Small molecule inhibitors |

| CGP049090 | TCF/β-catenin | Preclinical | NA | Natural compounds |

| PKF118-310 | TCF/β-catenin | Preclinical | NA | Natural compounds |

| PKF115-584 | TCF/β-catenin | Preclinical | NA | Natural compounds |

| FH535 | TCF/β-catenin | Preclinical | NA | Small molecule inhibitors |

| Peg-IFN | TCF/β-catenin | Phase II | NCT00610389 | Protein |

| WIF1-Fc and sFRP-Fc | Wnt ligands | Preclinical | NA | Protein |

| Anti-Wnt1 | Wnt1 | Preclinical | NA | Protein |

| CGK062 | β-catenin phosphorylation | Preclinical | NA | Small molecule inhibitors |

| PMED-1 | β-catenin/CBP | Preclinical | NA | Small molecule inhibitors |

| PRI-724 | β-catenin/CBP | Phase I/II | NCT01302405 | Small molecule inhibitors |

| Hydroxychloroquine | v-ATPase | Phase II | NCT03037437 | Small molecule inhibitors |

| Chloroquine | v-ATPase | Preclinical | NA | Small molecule inhibitors |

| Bafilomycin | v-ATPase | Preclinical | NA | Small molecule inhibitors |

| Concanamycin | v-ATPase | Preclinical | NA | Small molecule inhibitors |

| CAR-GPC3 T cell | GPC3 | Phase I | NCT02932956 | Cells |

| Anti-GPC3 antibody | GPC3 | Phase II | NCT01507168 | Protein |

| CIK with anti-GPC3 | GPC3 | Phase II | NCT03146637 | Cells |

DKK1, Dickkopf 1; FZD, frizzed; NA, not available; PORCN, porcupine; TCF, T-cell factor; peg-IFN, pegylated-Interferon-α2a; CBP, CREB binding protein; v-ATPase, vacuolar-type ATPase.

β-catenin-mediated gene transactivation

The small molecule ICG-001 inhibits the interaction between β-catenin and CREB binding protein (CREBBP/CBP) for suppression of β-catenin-mediated gene transactivation (Fig. 4) [161]. A phase Ib/IIa clinical trial of the ICG-001 derivative, PRI-724, targeting HCC has been terminated [162]. Similar to ICG-001, PMED-1 disrupts β-catenin-CREBBP interaction and suppresses β-catenin target gene activation [163]. PMED-1 inhibits HCC cell proliferation but not normal human hepatocytes [163].

PKF118-310, PKF115-584, and CGP049090 are small-molecule inhibitors targeting the β-catenin-TCF complex (Fig. 4) [164]. These antagonists displayed the dose-dependent cytotoxicity in HepG2, Hep40, and Huh7 cell lines, with reduced cytotoxicity (10%) to normal hepatocytes. PKF118-310, PKF115- 584, and CGP049090 downregulated β-catenin target genes (MYC, CCND1, and Survivin/BIRC5) and inhibited the growth of HepG2 xenografts [164,165]. Similar to the mechanism of PKF118-310, PKF115-584, and CGP049090, FH535 inhibits β-catenin-mediated gene transactivation by interrupting the recruitment of nuclear receptor coactivator 2 (NCOA2)/GRIP1 to the β-catenin transcriptional complex [166]. It was shown that FH535 inhibits HCC cell proliferation by reducing cancer cell stemness [165].

β-catenin phosphorylation

CGK062 promotes PKCα-mediated phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser33/Ser37, which degrades β-catenin by the proteasome (Fig. 4) [167]. Consistently, CGK062 inhibited the expression of β-catenin target genes (CCND1, MYC, and AXIN2) and suppressed the growth of Wnt/β-catenin-activated HCC cells [167].

Cancer-specific targeting of Wnt signaling

Given the pivotal role of Wnt signaling in the homeostasis and regeneration of multiple organs [168-170], broad-spectrum Wnt signaling inhibitors cause detrimental effects on the normal cells and organs. Therefore, cancer-specific Wnt signaling regulators may be attractive for Wnt signaling blockade therapy. TMEM9, an amplifier of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, promotes lysosomal protein degradation via v-ATPase, resulting in APC downregulation [46]. TMEM9 is highly expressed in liver regeneration and HCC. Genetic ablation of TMEM9 inhibits HCC tumorigenesis with downregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling [46]. Similarly, v-ATPase inhibitors, bafilomycin and concanamycin [171,172], also inhibit Wnt/β-catenin signaling without toxicity to normal cells and animals (Fig. 4, Table 1) [45,46]. Thus, molecular targeting of the TMEM9-v-ATPase axis can be used as cancer-specific Wnt/β-catenin blockade.

Glypican-3 (GPC3) is a proteoglycan binding to the FZD receptor and stimulates Wnt ligands-FZD interaction, resulting in the Wnt signaling activation (Fig. 4) [173]. GPC-3 is specifically expressed in HCC but not in normal human liver tissue [174]. The ectopic expression of GPC3 promotes the proliferation of HCC cells [175]. HS20 (an anti-GPC3 monoclonal antibody) suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling via inhibiting the interaction of Wnt3a with the GPC3 [176]. In xenograft mouse models, HS20 inhibited HCC progression without apparent concomitant toxicity [176]. To date, including CAR-GPC3 T cells or anti-GPC3 antibodies, 33 clinical trials related to GPC3 for HCC treatment were registered (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Concluding remarks

Wnt signaling activation plays a pivotal role in liver regeneration, metabolic zonation, liver diseases, and liver cancer. Aberrantly hyperactivated Wnt signaling promotes liver tumorigenesis and progression, often in conjunction with liver diseases. Although direct targeting of Wnt signaling sounds attractive as cancer therapy, given the crucial roles of Wnt signaling in tissue homeostasis and regeneration, severe adverse effects from Wnt blockade are inevitable. Nonetheless, an in-depth understanding of the biology of Wnt signaling in liver cancer and exploring cancer-specific Wnt signaling regulators are expected to identify molecular targets specific to liver cancer, which may overcome the current limitations of Wnt signaling inhibitors, and further improve therapeutic strategies of liver cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

We apologize for not including all relevant studies in the field due to limited space. This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP200315 to J.I.P.) and the National Cancer Institute (CA193297 and CA256207 to J.I.P.).

Abbreviations

- AFB1

aflatoxin type B1

- ALD

alcoholic liver disease

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- AXIN

axis inhibition protein

- CCA

cholangiocarcinoma

- CCl4

carbon tetrachloride

- CEBPA

CCAAT enhancer-binding protein α

- CK1

casein kinase 1

- CREBBP/CBP

CREB binding protein

- CV

central vein

- DDC

1

- DEN

diethylnitrosamine

- DKK1

Dickkopf 1

- DVL

dishevelled

- E2F1

E2F transcription factor 1

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- EtOH

ethanol

- FZD

frizzed

- GPC3

glypican-3

- GSK3

glycogen synthase kinase 3

- HB

hepatoblastoma

- HBsAg

hepatitis B virus surface antigen

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- IGF1

insulin-like growth factor 1

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- KO

knock-out

- LGR5

leucine-containing repeat G-protein-coupled receptor 5

- LOF

loss-of-function

- LRP6

lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCP

monocyte chemoattractant protein

- MMP7

matrix metallopeptidase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- MVBs

multivesicular bodies

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NCOA2

nuclear receptor coactivator 2

- NF-ĸB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- peg-IFN

pegylated-Interferon-α2a

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PORCN

porcupine

- PPARG

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- RanBP3

Ran-binding protein 3

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SAL

salinomycin

- SFRP1

secreted frizzled-related protein 1

- sFZD7

secreted FZD7

- SREBF

sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor

- TCF/LEF

T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor

- TMEM9

transmembrane protein 9

- TNKS

tankyrase

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- WF1

Wnt inhibitory factor 1

- WISP1

Wnt1-inducible-signaling pathway protein 1

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

G.Z. and J.I.P. wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Clinical and Molecular Hepatology website (http://www.e-cmh.org).

Additional clinical trials related with peg-IFN, hydroxychloroquine and CAR-GPC3 T cell in liver cancers

REFERENCES

- 1.Clemens MM, McGill MR, Apte U. Mechanisms and biomarkers of liver regeneration after drug-induced liver injury. Adv Pharmacol. 2019;85:241–262. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michalopoulos GK. Hepatostat: liver regeneration and normal liver tissue maintenance. Hepatology. 2017;65:1384–1392. doi: 10.1002/hep.28988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko S, Russell JO, Molina LM, Monga SP. Liver progenitors and adult cell plasticity in hepatic injury and repair: knowns and unknowns. Annu Rev Pathol. 2020;15:23–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012419-032824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duncan AW, Taylor MH, Hickey RD, Hanlon Newell AE, Lenzi ML, Olson SB, et al. The ploidy conveyor of mature hepatocytes as a source of genetic variation. Nature. 2010;467:707–710. doi: 10.1038/nature09414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anti M, Marra G, Rapaccini GL, Rumi C, Bussa S, Fadda G, et al. DNA ploidy pattern in human chronic liver diseases and hepatic nodular lesions. Flow cytometric analysis on echoguided needle liver biopsy. Cancer. 1994;73:281–288. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940115)73:2<281::aid-cncr2820730208>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan AW, Hanlon Newell AE, Smith L, Wilson EM, Olson SB, Thayer MJ, et al. Frequent aneuploidy among normal human hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:25–28. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llovet JM, Zucman-Rossi J, Pikarsky E, Sangro B, Schwartz M, Sherman M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tortelote GG, Reis RR, de Almeida Mendes F, Abreu JG. Complexity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway: searching for an activation model. Cell Signal. 2017;40:30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia XH, Xiao CJ, Shan H. Facilitation of liver cancer SMCC7721 cell aging by sirtuin 4 via inhibiting JAK2/STAT3 signal pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:1248–1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, Gingold JA, Su X. Immunomodulatory TGF-β signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Trends Mol Med. 2019;25:1010–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czauderna C, Castven D, Mahn FL, Marquardt JU. Context-dependent role of NF-κB signaling in primary liver cancer-from tumor development to therapeutic implications. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1053. doi: 10.3390/cancers11081053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell JO, Monga SP. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in liver development, homeostasis, and pathobiology. Annu Rev Pathol. 2018;13:351–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-044010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng JH, She H, Han YP, Wang J, Xiong S, Asahina K, et al. Wnt antagonism inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G39–G49. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00263.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng G, Awan F, Otruba W, Muller P, Apte U, Tan X, et al. Wnt’er in liver: expression of Wnt and frizzled genes in mouse. Hepatology. 2007;45:195–204. doi: 10.1002/hep.21473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma R, Martínez-Ramírez AS, Borders TL, Gao F, Sosa-Pineda B. Metabolic and non-metabolic liver zonation is established non-synchronously and requires sinusoidal Wnts. Elife. 2020;9:e46206. doi: 10.7554/eLife.46206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monga SP. β-catenin signaling and roles in liver homeostasis, injury, and tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1294–1310. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell. 2017;169:985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheibner K, Bakhti M, Bastidas-Ponce A, Lickert H. Wnt signaling: implications in endoderm development and pancreas organogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2019;61:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinhart Z, Angers S. Wnt signaling in development and tissue homeostasis. Development. 2018;145:dev146589. doi: 10.1242/dev.146589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu S, Monga SP. Wnt/-catenin signaling and liver regeneration: circuit, biology, and opportunities. Gene Expr. 2021;20:189–199. doi: 10.3727/105221621X16111780348794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhan T, Rindtorff N, Boutros M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:1461–1473. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raslan AA, Yoon JK. WNT signaling in lung repair and regeneration. Mol Cells. 2020;43:774–783. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2020.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girardi F, Le Grand F. Wnt signaling in skeletal muscle development and regeneration. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2018;153:157–179. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackstadt R, Hodder MC, Sansom OJ. WNT and β-catenin in cancer: genes and therapy. Annu Rev Cancer Biol. 2020;4:177–196. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monga SP, Pediaditakis P, Mule K, Stolz DB, Michalopoulos GK. Changes in WNT/beta-catenin pathway during regulated growth in rat liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2001;33:1098–1109. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.23786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stolz DB, Mars WM, Petersen BE, Kim TH, Michalopoulos GK. Growth factor signal transduction immediately after two-thirds partial hepatectomy in the rat. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3954–3960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Köhler C, Bell AW, Bowen WC, Monga SP, Fleig W, Michalopoulos GK. Expression of notch-1 and its ligand Jagged-1 in rat liver during liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2004;39:1056–1065. doi: 10.1002/hep.20156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins GM, Anderson RM. Experimental pathology of the liver. 1. Restoration of the liver of the white rat following partial surgical removal. Arch Pathol. 1931;12:186–202. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikfarjam M, Malcontenti-Wilson C, Fanartzis M, Daruwalla J, Christophi C. A model of partial hepatectomy in mice. J Invest Surg. 2004;17:291–294. doi: 10.1080/08941930490502871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadler KC, Krahn KN, Gaur NA, Ukomadu C. Liver growth in the embryo and during liver regeneration in zebrafish requires the cell cycle regulator, uhrf1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1570–1575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610774104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curado S, Stainier DY, Anderson RM. Nitroreductase-mediated cell/tissue ablation in zebrafish: a spatially and temporally controlled ablation method with applications in developmental and regeneration studies. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:948–954. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teschke R, Vierke W, Goldermann L. Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) levels and serum activities of liver enzymes following acute CCl4 intoxication. Toxicol Lett. 1983;17:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(83)90054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Preisegger KH, Factor VM, Fuchsbichler A, Stumptner C, Denk H, Thorgeirsson SS. Atypical ductular proliferation and its inhibition by transforming growth factor beta1 in the 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine mouse model for chronic alcoholic liver disease. Lab Invest. 1999;79:103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oderberg IM, Goessling W. Partial hepatectomy in adult zebrafish. J Vis Exp. 2021;(170):10. doi: 10.3791/62349. 3791/62349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.North TE, Babu IR, Vedder LM, Lord AM, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR, et al. PGE2-regulated Wnt signaling and N-acetylcysteine are synergistically hepatoprotective in zebrafish acetaminophen injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17315–17320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008209107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sekine S, Gutiérrez PJ, Lan BY, Feng S, Hebrok M. Liver-specific loss of beta-catenin results in delayed hepatocyte proliferation after partial hepatectomy. Hepatology. 2007;45:361–368. doi: 10.1002/hep.21523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goessling W, North TE, Lord AM, Ceol C, Lee S, Weidinger G, et al. APC mutant zebrafish uncover a changing temporal requirement for wnt signaling in liver development. Dev Biol. 2008;320:161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.05.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun T, Pikiolek M, Orsini V, Bergling S, Holwerda S, Morelli L, et al. AXIN2+ pericentral hepatocytes have limited contributions to liver homeostasis and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26:97–107.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huch M, Dorrell C, Boj SF, van Es JH, Li VS, van de Wetering M, et al. In vitro expansion of single Lgr5+ liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration. Nature. 2013;494:247–250. doi: 10.1038/nature11826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carmon KS, Lin Q, Gong X, Thomas A, Liu Q. LGR5 interacts and cointernalizes with Wnt receptors to modulate Wnt/ β-catenin signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:2054–2064. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00272-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jho EH, Zhang T, Domon C, Joo CK, Freund JN, Costantini F. Wnt/beta-catenin/Tcf signaling induces the transcription of Axin2, a negative regulator of the signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1172–1183. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1172-1183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lustig B, Jerchow B, Sachs M, Weiler S, Pietsch T, Karsten U, et al. Negative feedback loop of Wnt signaling through upregulation of conductin/axin2 in colorectal and liver tumors. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1184–1193. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1184-1193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung YS, Jun S, Kim MJ, Lee SH, Suh HN, Lien EM, et al. TMEM9 promotes intestinal tumorigenesis through vacuolarATPase-activated Wnt/β-catenin signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:1421–1433. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0219-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jung YS, Stratton SA, Lee SH, Kim MJ, Jun S, Zhang J, et al. TMEM9-v-ATPase activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling via APC lysosomal degradation for liver regeneration and tumorigenesis. Hepatology. 2021;73:776–794. doi: 10.1002/hep.31305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kudo Y, Sugimoto M, Arias E, Kasashima H, Cordes T, Linares JF, et al. PKCλ/ι loss induces autophagy, oxidative phosphorylation, and NRF2 to promote liver cancer progression. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:247–262.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z, Li Z, Ye Y, Xie L, Li W. Oxidative stress and liver cancer: etiology and therapeutic targets. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:7891574. doi: 10.1155/2016/7891574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Funato Y, Michiue T, Asashima M, Miki H. The thioredoxinrelated redox-regulating protein nucleoredoxin inhibits Wntbeta-catenin signalling through dishevelled. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:501–508. doi: 10.1038/ncb1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou T, Zhou KK, Lee K, Gao G, Lyons TJ, Kowluru R, et al. The role of lipid peroxidation products and oxidative stress in activation of the canonical wingless-type MMTV integration site (WNT) pathway in a rat model of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia. 2011;54:459–468. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1943-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun HC, Zhang W, Qin LX, Zhang BH, Ye QH, Wang L, et al. Positive serum hepatitis B e antigen is associated with higher risk of early recurrence and poorer survival in patients after curative resection of hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2007;47:684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Weinbaum CM, Sabin M, Smith BD, Lesesne SB. Forecasting the morbidity and mortality associated with prevalent cases of pre-cirrhotic chronic hepatitis C in the United States. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang JD, Kim WR, Coelho R, Mettler TA, Benson JT, Sanderson SO, et al. Cirrhosis is present in most patients with hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roudot-Thoraval F. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2021;45:101596. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.101596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mavilia MG, Wu GY. HBV-HCV coinfection: viral interactions, management, and viral reactivation. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2018;6:296–305. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2018.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levrero M, Zucman-Rossi J. Mechanisms of HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2016;64(1 Suppl):S84–S101. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arbuthnot P, Kew M. Hepatitis B virus and hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Exp Pathol. 2001;82:77–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2001.iep0082-0077-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neuveut C, Wei Y, Buendia MA. Mechanisms of HBV-related hepatocarcinogenesis. J Hepatol. 2010;52:594–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tian X, Li J, Ma ZM, Zhao C, Wan DF, Wen YM. Role of hepatitis B surface antigen in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: regulation of lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:58. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Javanmard D, Najafi M, Babaei MR, Karbalaie Niya MH, Esghaei M, Panahi M, et al. Investigation of CTNNB1 gene mutations and expression in hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis in association with hepatitis B virus infection. Infect Agent Cancer. 2020;15:37. doi: 10.1186/s13027-020-00297-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zucman-Rossi J, Benhamouche S, Godard C, Boyault S, Grimber G, Balabaud C, et al. Differential effects of inactivated Axin1 and activated beta-catenin mutations in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;26:774–780. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Galy O, Chemin I, Le Roux E, Villar S, Le Calvez-Kelm F, Lereau M, et al. Mutations in TP53 and CTNNB1 in relation to hepatitis B and C infections in hepatocellular carcinomas from Thailand. Hepat Res Treat. 2011;2011:697162. doi: 10.1155/2011/697162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hsieh A, Kim HS, Lim SO, Yu DY, Jung G. Hepatitis B viral X protein interacts with tumor suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli to activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cancer Lett. 2011;300:162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feitelson MA, Duan LX. Hepatitis B virus X antigen in the pathogenesis of chronic infections and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1141–1157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lau CC, Sun T, Ching AK, He M, Li JW, Wong AM, et al. Viralhuman chimeric transcript predisposes risk to liver cancer development and progression. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:335–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moradpour D, Penin F. Hepatitis C virus proteins: from structure to function. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013;369:113–142. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-27340-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fukutomi T, Zhou Y, Kawai S, Eguchi H, Wands JR, Li J. Hepatitis C virus core protein stimulates hepatocyte growth: correlation with upregulation of Wnt-1 expression. Hepatology. 2005;41:1096–1105. doi: 10.1002/hep.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu J, Ding X, Tang J, Cao Y, Hu P, Zhou F, et al. Enhancement of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity by HCV core protein promotes cell growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Umer M, Qureshi SA, Hashmi ZY, Raza A, Ahmad J, Rahman M, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of Wnt pathway inhibitors in hepatitis C virus - induced multistep hepatocarcinogenesis. Virol J. 2014;11:117. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quan H, Zhou F, Nie D, Chen Q, Cai X, Shan X, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein epigenetically silences SFRP1 and enhances HCC aggressiveness by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene. 2014;33:2826–2835. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ripoli M, Barbano R, Balsamo T, Piccoli C, Brunetti V, Coco M, et al. Hypermethylated levels of E-cadherin promoter in Huh-7 cells expressing the HCV core protein. Virus Res. 2011;160:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jung YS, Wang W, Jun S, Zhang J, Srivastava M, Kim MJ, et al. Deregulation of CRAD-controlled cytoskeleton initiates mucinous colorectal cancer via β-catenin. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:1303–1314. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0215-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu Y, El-Serag HB, Jiao L, Lee J, Moore D, Franco LM, et al. WNT signaling pathway gene polymorphisms and risk of hepatic fibrosis and inflammation in HCV-infected patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takahara Y, Takahashi M, Zhang QW, Wagatsuma H, Mori M, Tamori A, et al. Serial changes in expression of functionally clustered genes in progression of liver fibrosis in hepatitis C patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2010–2022. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mercer KE, Hennings L, Ronis MJ. Alcohol consumption, Wnt/ β-catenin signaling, and hepatocarcinogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;815:185–195. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-09614-8_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim HS, Kim SJ, Bae J, Wang Y, Park SY, Min YS, et al. The p90rsk-mediated signaling of ethanol-induced cell proliferation in HepG2 cell line. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;20:595–603. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2016.20.6.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang F, Yang JL, Yu KK, Xu M, Xu YZ, Chen L, et al. Activation of the NF-κB pathway as a mechanism of alcohol enhanced progression and metastasis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:10. doi: 10.1186/s12943-014-0274-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang CF, Zhong YJ, Ma Z, Li L, Shi L, Chen L, et al. NOX4/ROS mediate ethanol-induced apoptosis via MAPK signal pathway in L-02 cells. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41:2306–2316. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang C, Ellis JL, Yin C. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling facilitates liver repair from acute ethanol-induced injury in zebrafish. Dis Model Mech. 2016;9:1383–1396. doi: 10.1242/dmm.024950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mandrekar P, Ambade A, Lim A, Szabo G, Catalano D. An essential role for monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in alcoholic liver injury: regulation of proinflammatory cytokines and hepatic steatosis in mice. Hepatology. 2011;54:2185–2197. doi: 10.1002/hep.24599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yuen MF, Tanaka Y, Fong DY, Fung J, Wong DK, Yuen JC, et al. Independent risk factors and predictive score for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wong VW, Chu WC, Wong GL, Chan RS, Chim AM, Ong A, et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and advanced fibrosis in Hong Kong Chinese: a population study using proton-magnetic resonance spectroscopy and transient elastography. Gut. 2012;61:409–415. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bhala N, Angulo P, van der Poorten D, Lee E, Hui JM, Saracco G, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis: an international collaborative study. Hepatology. 2011;54:1208–1216. doi: 10.1002/hep.24491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Farrell GC, van Rooyen D, Gan L, Chitturi S. NASH is an inflammatory disorder: pathogenic, prognostic and therapeutic implications. Gut Liver. 2012;6:149–171. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Murphy SK, Yang H, Moylan CA, Pang H, Dellinger A, Abdelmalek MF, et al. Relationship between methylome and transcriptome in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1076–1087. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chettouh H, Lequoy M, Fartoux L, Vigouroux C, DesboisMouthon C. Hyperinsulinaemia and insulin signalling in the pathogenesis and the clinical course of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2015;35:2203–2217. doi: 10.1111/liv.12903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jonatan D, Spence JR, Method AM, Kofron M, Sinagoga K, Haataja L, et al. Sox17 regulates insulin secretion in the normal and pathologic mouse β cell. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jia Y, Yang Y, Liu S, Herman JG, Lu F, Guo M. SOX17 antagonizes WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Epigenetics. 2010;5:743–749. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.8.13104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ackers I, Malgor R. Interrelationship of canonical and noncanonical Wnt signalling pathways in chronic metabolic diseases. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2018;15:3–13. doi: 10.1177/1479164117738442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang S, Song K, Srivastava R, Dong C, Go GW, Li N, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease induced by noncanonical Wnt and its rescue by Wnt3a. FASEB J. 2015;29:3436–3445. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-271171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kew MC. Synergistic interaction between aflatoxin B1 and hepatitis B virus in hepatocarcinogenesis. Liver Int. 2003;23:405–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2003.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Devereux TR, Stern MC, Flake GP, Yu MC, Zhang ZQ, London SJ, et al. CTNNB1 mutations and beta-catenin protein accumulation in human hepatocellular carcinomas associated with high exposure to aflatoxin B1. Mol Carcinog. 2001;31:68–73. doi: 10.1002/mc.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:589–604. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bengochea A, de Souza MM, Lefrançois L, Le Roux E, Galy O, Chemin I, et al. Common dysregulation of Wnt/frizzled receptor elements in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:143–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Boyault S, Rickman DS, de Reyniès A, Balabaud C, Rebouissou S, Jeannot E, et al. Transcriptome classification of HCC is related to gene alterations and to new therapeutic targets. Hepatology. 2007;45:42–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.21467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fodde R, Smits R, Clevers H. APC, signal transduction and genetic instability in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:55–67. doi: 10.1038/35094067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Khemlina G, Ikeda S, Kurzrock R. The biology of hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for genomic and immune therapies. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:149. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0712-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Satoh S, Daigo Y, Furukawa Y, Kato T, Miwa N, Nishiwaki T, et al. AXIN1 mutations in hepatocellular carcinomas, and growth suppression in cancer cells by virus-mediated transfer of AXIN1. Nat Genet. 2000;24:245–250. doi: 10.1038/73448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Park JY, Park WS, Nam SW, Kim SY, Lee SH, Yoo NJ, et al. Mutations of beta-catenin and AXIN I genes are a late event in human hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Liver Int. 2005;25:70–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhu M, Lu T, Jia Y, Luo X, Gopal P, Li L, et al. Somatic mutations increase hepatic clonal fitness and regeneration in chronic liver disease. Cell. 2019;177:608–621.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Marquardt JU, Seo D, Andersen JB, Gillen MC, Kim MS, Conner EA, et al. Sequential transcriptome analysis of human liver cancer indicates late stage acquisition of malignant traits. J Hepatol. 2014;60:346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rebouissou S, Nault JC. Advances in molecular classification and precision oncology in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020;72:215–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Abitbol S, Dahmani R, Coulouarn C, Ragazzon B, Mlecnik B, Senni N, et al. AXIN deficiency in human and mouse hepatocytes induces hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of β-catenin activation. J Hepatol. 2018;68:1203–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ. In: Zakim and Boyer’s Hepatology. 6th ed. Boyer TD, Manns MP, Sanyal AJ, editors. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012. Cholangiocarcinoma; pp. 1032–1044. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Boulter L, Guest RV, Kendall TJ, Wilson DH, Wojtacha D, Robson AJ, et al. WNT signaling drives cholangiocarcinoma growth and can be pharmacologically inhibited. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1269–1285. doi: 10.1172/JCI76452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen W, Liang J, Huang L, Cai J, Lei Y, Lai J, et al. Characterizing the activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in hilar cholangiocarcinoma using a tissue microarray approach. Eur J Histochem. 2016;60:2536. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2016.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Banales JM, Marin JJG, Lamarca A, Rodrigues PM, Khan SA, Roberts LR, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:557–588. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0310-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vaquero J, Guedj N, Clapéron A, Nguyen Ho-Bouldoires TH, Paradis V, Fouassier L. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cholangiocarcinoma: from clinical evidence to regulatory networks. J Hepatol. 2017;66:424–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nitta T, Mitsuhashi T, Hatanaka Y, Miyamoto M, Oba K, Tsuchikawa T, et al. Prognostic significance of epithelialmesenchymal transition-related markers in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: comprehensive immunohistochemical study using a tissue microarray. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1363–1372. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chaw SY, Abdul Majeed A, Dalley AJ, Chan A, Stein S, Farah CS. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) biomarkers--E-cadherin, beta-catenin, APC and vimentin--in oral squamous cell carcinogenesis and transformation. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:997–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Valenta T, Hausmann G, Basler K. The many faces and functions of β-catenin. EMBO J. 2012;31:2714–2736. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang GF, Qiu L, Yang SL, Wu JC, Liu TJ. Wnt/β-catenin signaling as an emerging potential key pharmacological target in cholangiocarcinoma. Biosci Rep. 2020;40:BSR20193353. doi: 10.1042/BSR20193353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Xue W, Dong B, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Yang C, Xie Y, et al. Upregulation of TTYH3 promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through Wnt/β-catenin signaling and inhibits apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2021;44:1351–1361. doi: 10.1007/s13402-021-00642-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Carrillo-Reixach J, Torrens L, Simon-Coma M, Royo L, Domingo-Sàbat M, Abril-Fornaguera J, et al. Epigenetic footprint enables molecular risk stratification of hepatoblastoma with clinical implications. J Hepatol. 2020;73:328–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gupta K, Rane S, Das A, Marwaha RK, Menon P, Rao KL. Relationship of β-catenin and postchemotherapy histopathologic changes with overall survival in patients with hepatoblastoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:e320–e328. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182580471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Crippa S, Ancey PB, Vazquez J, Angelino P, Rougemont AL, Guettier C, et al. Mutant CTNNB1 and histological heterogeneity define metabolic subtypes of hepatoblastoma. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:1589–1604. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201707814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.López-Terrada D, Gunaratne PH, Adesina AM, Pulliam J, Hoang DM, Nguyen Y, et al. Histologic subtypes of hepatoblastoma are characterized by differential canonical Wnt and notch pathway activation in DLK+ precursors. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:783–794. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Taniguchi K, Roberts LR, Aderca IN, Dong X, Qian C, Murphy LM, et al. Mutational spectrum of beta-catenin, AXIN1, and AXIN2 in hepatocellular carcinomas and hepatoblastomas. Oncogene. 2002;21:4863–4871. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shah K, Panchal S, Patel B. Porcupine inhibitors: novel and emerging anti-cancer therapeutics targeting the Wnt signaling pathway. Pharmacol Res. 2021;167:105532. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Liu J, Pan S, Hsieh MH, Ng N, Sun F, Wang T, et al. Targeting Wnt-driven cancer through the inhibition of porcupine by LGK974. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20224–20229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314239110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Madan B, Ke Z, Harmston N, Ho SY, Frois AO, Alam J, et al. Wnt addiction of genetically defined cancers reversed by PORCN inhibition. Oncogene. 2016;35:2197–2207. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Proffitt KD, Madan B, Ke Z, Pendharkar V, Ding L, Lee MA, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of the Wnt acyltransferase PORCN prevents growth of WNT-driven mammary cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:502–507. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wang W, Xu L, Liu P, Jairam K, Yin Y, Chen K, et al. Blocking Wnt secretion reduces growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines mostly independent of β-catenin signaling. Neoplasia. 2016;18:711–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Barrott JJ, Cash GM, Smith AP, Barrow JR, Murtaugh LC. Deletion of mouse porcn blocks Wnt ligand secretion and reveals an ectodermal etiology of human focal dermal hypoplasia/Goltz syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12752–12757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006437108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Liu W, Shaver TM, Balasa A, Ljungberg MC, Wang X, Wen S, et al. Deletion of porcn in mice leads to multiple developmental defects and models human focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome) PLoS One. 2012;7:e32331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Funck-Brentano T, Nilsson KH, Brommage R, Henning P, Lerner UH, Koskela A, et al. Porcupine inhibitors impair trabecular and cortical bone mass and strength in mice. J Endocrinol. 2018;238:13–23. doi: 10.1530/JOE-18-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.He X, Semenov M, Tamai K, Zeng X. LDL receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: arrows point the way. Development. 2004;131:1663–1677. doi: 10.1242/dev.01117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wei W, Chua MS, Grepper S, So SK. Blockade of Wnt-1 signaling leads to anti-tumor effects in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:76. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cruciat CM, Niehrs C. Secreted and transmembrane wnt inhibitors and activators. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a015081. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a015081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Niehrs C. Function and biological roles of the Dickkopf family of Wnt modulators. Oncogene. 2006;25:7469–7481. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kawazoe M, Kaneko K, Nanki T. Glucocorticoid therapy suppresses Wnt signaling by reducing the ratio of serum Wnt3a to Wnt inhibitors, sFRP-1 and Wif-1. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:2947–2954. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05554-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hu J, Dong A, Fernandez-Ruiz V, Shan J, Kawa M, MartínezAnsó E, et al. Blockade of Wnt signaling inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6951–6959. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Glinka A, Wu W, Delius H, Monaghan AP, Blumenstock C, Niehrs C. Dickkopf-1 is a member of a new family of secreted proteins and functions in head induction. Nature. 1998;391:357–362. doi: 10.1038/34848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Caneparo L, Huang YL, Staudt N, Tada M, Ahrendt R, Kazanskaya O, et al. Dickkopf-1 regulates gastrulation movements by coordinated modulation of Wnt/beta catenin and Wnt/PCP activities, through interaction with the Dally-like homolog Knypek. Genes Dev. 2007;21:465–480. doi: 10.1101/gad.406007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cha SW, Tadjuidje E, Tao Q, Wylie C, Heasman J. Wnt5a and Wnt11 interact in a maternal Dkk1-regulated fashion to activate both canonical and non-canonical signaling in Xenopus axis formation. Development. 2008;135:3719–3729. doi: 10.1242/dev.029025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Nambotin SB, Lefrancois L, Sainsily X, Berthillon P, Kim M, Wands JR, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of frizzled-7 displays anti-tumor properties in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2011;54:288–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Jimeno A, Gordon M, Chugh R, Messersmith W, Mendelson D, Dupont J, et al. A first-in-human phase I study of the anticancer stem cell agent ipafricept (OMP-54F28), a decoy receptor for wnt ligands, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:7490–7497. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Moore KN, Gunderson CC, Sabbatini P, McMeekin DS, MantiaSmaldone G, Burger RA, et al. A phase 1b dose escalation study of ipafricept (OMP54F28) in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in patients with recurrent platinumsensitive ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hoey T. Development of FZD8-Fc (OMP-54F28), a Wnt signaling antagonist that inhibits tumor growth and reduces tumor initiating cell frequency. AACR Annual Meeting; Washington DC, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Wei W, Chua MS, Grepper S, So SK. Soluble frizzled-7 receptor inhibits Wnt signaling and sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma cells towards doxorubicin. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Fischer MM, Cancilla B, Yeung VP, Cattaruzza F, Chartier C, Murriel CL, et al. WNT antagonists exhibit unique combinatorial antitumor activity with taxanes by potentiating mitotic cell death. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1700090. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1700090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]