Abstract

Close and frequent follow-up of heart failure (HF) patients improves clinical outcomes. Mobile telemonitoring applications are advantageous alternatives due to their wide availability, portability, low cost, computing power, and interconnectivity. This study aims to evaluate the impact of telemonitoring apps on mortality, hospitalization, and quality of life (QoL) in HF patients. We conducted a registered (PROSPERO CRD42022299516) systematic review of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) evaluating mobile-based telemonitoring strategies in patients with HF, published between January 2000 and December 2021 in 4 databases (PubMed, EMBASE, BVSalud/LILACS, Cochrane Reviews). We assessed the risk of bias using the RoB2 tool. The outcome of interest was the effect on mortality, hospitalization risk, and/or QoL. We performed meta-analysis when appropriate; heterogeneity and risk of publication bias were evaluated. Otherwise, descriptive analyses are offered. We screened 900 references and 19 RCTs were included for review. The risk of bias for mortality and hospitalization was mostly low, whereas for QoL was high. We observed a reduced risk of hospitalization due to HF with the use of mobile-based telemonitoring strategies (RR 0.77 [0.67; 0.89]; I2 7%). Non-statistically significant reduction in mortality risk was observed. The impact on QoL was variable between studies, with different scores and reporting measures used, thus limiting data pooling. The use of mobile-based telemonitoring strategies in patients with HF reduces risk of hospitalization due to HF. As smartphones and wirelessly connected devices are increasingly available, further research on this topic is warranted, particularly in the foundational therapy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10741-022-10291-1.

Keywords: Heart failure, Telemonitoring, Mobile applications, Smartphones, mHealth, Self-management

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a global health problem that has a negative impact on the quality of life (QoL) of patients [1]. An overall prevalence of 1–2% is estimated, which increases with age, being the most frequent mortality cause in patients older than 65 years [2–4]. Most patients with HF are hospitalized at least once a year [5].

Close and frequent follow-up of these patients by multidisciplinary teams has demonstrated to reduce mortality and hospitalizations due to acute HF [6–8]. However, it is difficult to ensure strict monitoring, so alternative strategies such as telemonitoring are gaining ground [9]. This approach allows to obtain and provide information on patient’s health status though a virtual interface, assist care, reduce the frequency of adverse outcomes, improve QoL, speed up access to healthcare, reduce transportation costs, and reduce face-to-face visits [10, 11].

Telemonitoring strategies have improved medication adherence and re-admission rates [12]. Strategies focusing on treatment optimization and self-care seem to be more successful reducing mortality and hospitalizations due to heart failure, compared to those that aim at early detection and management of acute events, probably due to false alerts [13]. Home-based telemonitoring have proven to be an efficient method of educating and motivating the patients [14]. Smartphone-based apps for telemonitoring in HF are advantageous due to their wide availability, portability, low-cost, computing power, and interconnectivity [15, 16]. A growing number of smartphone-based apps with differential complexities are now available [17–20], with variable feedback strategies, including in some cases 24 h support for emergency event detection and management. However, few studies have evaluated their benefits in clinical outcomes, as shown in previous systematic reviews [16, 21–27].

In this systematic review of RCTs, we evaluated mobile-based telemonitoring strategies in patients with HF, assessing their impact on mortality, hospitalization, and QoL, when compared to standard care.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review followed Cochrane methodology [28]. Protocol was approved by the institutional committee (approval code: 005–2022) and registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), #CRD42018107855. This report is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [29].

Eligibility criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating adults (> 18 years old) with HF and comparing telemonitoring strategies using mobile applications with usual care, published between 2000 and 2021. A clear HF definition had to be defined (universal definition [30] or an explicit definition from a national or international guideline). We defined telemonitoring mobile application as a tool that should (1) register at least one relevant clinical variable for follow-up (i.e., symptoms, weight, heart rate, blood pressure); (2) offer an interface using any kind of mobile device; and (3) ask the patient to register clinical variables during follow-up. Studies should provide detailed description of clinical decisions derived from registered information (i.e., feedback), and measure at least one effectiveness outcome (mortality, hospitalization, or impact on QoL). For QoL, we included studies reporting any of the following: EQ-5D-5L [31], SF-36 [32], KCCQ [33], and MLHFQ [34]. We excluded non-randomized studies, reviews, abstracts, letters to the editor, case reports, case series, before and after studies, studies with follow-up of less than a month, studies focusing on multiple diseases, and studies using implantable devices or invasive monitoring.

Search strategy and information sources

A comprehensive literature search was conducted (full search strategy and terms described in Supplemental Appendix). Electronic databases, including PubMed (MEDLINE), EMBASE (Elsevier), BVSalud (LILACS), and Cochrane Reviews from January 1st, 2000, through December 31st, 2021, were searched. We included studies in English and Spanish. Terms used were “heart failure”, “Smartphone”, “telemedicine”, “mobile applications”, “mHealth”, plus filter “randomized controlled trial”, their synonyms and combinations using Boolean terms. We further searched for useful articles using a “snowball strategy” by reviewing references of included articles and searching grey literature. All duplicates and overlapping results were identified and removed in title screening phase.

Study selection

Study selection was performed by two independent researchers (MRdT, NHL, or JBC) using online application Abstrackr [35]. We reviewed full texts of relevant citations and further screened for eligibility. Disagreements between individual judgments were resolved by consensus or with a third evaluator (OMM), based on recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews [28] and PRISMA statement checklist [29].

Data collection process

Data was collected in standardized electronic form including study design, inclusion criteria, participant demographics and baseline characteristics (i.e., age, gender, basal functional class according to New York Heart Association classification [36], HF etiology, Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction [LVEF]), HF definition, telemonitoring software type, retrieved variable type, input methodology by patient, output variables for patient and physician, feedback availability, and follow-up time. Outcomes registered were all-cause mortality, mortality due to HF, all-cause or due to HF hospitalizations, and QoL. We did not adjust units for analysis. Data from included studies was collected by two investigators (MRdT, NHL, or JBC). Disagreements were resolved by consensus or with a third evaluator (OMM).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers (MRdT, NHL, or JBC) independently assessed all documents using RoB2 tool. An experienced third reviewer (OMM, AG, or DF) resolved disagreements between individual judgments. All studies were ranked in five different domains yielding results of low risk of bias, some concerns of bias, or high risk of bias. Risk of bias was determined by outcome. Mortality and hospitalization were not likely to be influenced by blinding, whereas measurement of QoL, despite being performed using standardized tools, relies on patients’ subjectivity. Evaluation of evidence certainty for each outcome was performed using GRADE tool [37].

Data synthesis and analysis

Data synthesis was performed for each evaluated outcome. We reported quantitative variables as median and interquartile range, and dichotomic variables as proportions. If sufficient information was available, we calculated relative risks for all-cause or HF-specific mortality, hospitalization outcomes, and QoL using a random effects model for meta-analysis. We performed subgroup analyses for follow-up time (< 1-year vs. > 1-year), patient feedback (immediate vs delayed), and software type. Data analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4. Finally, we generated summary and evaluation tables of retrieved evidence, including certainty of evidence for each outcome, using GRADEpro Tool.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

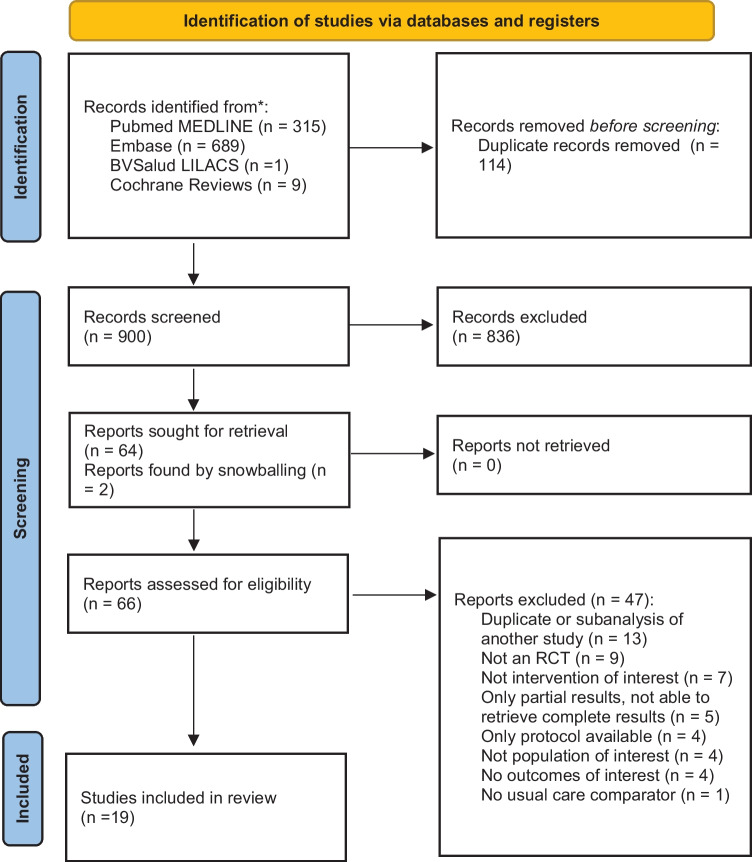

We found 900 references, 66 were reviewed in full text and 19 were finally included in the analysis [22, 25, 38–59]. Selection process is described in Fig. 1. Patient characteristics for each study are presented in Table 1. All included studies were published in English. Most (68%) included less than 100 patients per arm. Mean age was between 48 and 80 years old, with higher proportion of men. Twelve (63%) studies reported HF etiology, ischemic being the most frequent. Fourteen (74%) studies reported mean LVEF: 85% of studies included patients with reduced ejection fraction heart failure. Eleven studies (57%) reported mortality, 13 (68%) hospitalization, and 11 (57%) evaluated QoL. Most studies (63%, n = 12) had patient follow-up of less than a year.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA

Table 1.

Description of the studies

| Study | Intervention/Comparator | Patients, n | Age in years, Mean (SD or IQR) | Men, n (%) | NYHA, n (%) | LVEF, Median (SD or IQR) | Main etiology of HF, n (%) | Follow-up time to outcome in months, median | Main inclusion criteria Definition HF Recent Hx others |

Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Scherr et al. [22] |

I: home-based TM with MPh (MOBITEL) C: UC |

I: 54 C:54 |

I: 65 (62–72) C:67 (61–72) |

I: 40 (74) C: 39 (72) |

I: II 7 (13), III 33 (61), IV 14 (26) C: II 7(13), III 37 (68.5), IV 10(18.5) |

I: 25 (20–38) C: 29 (21–36) |

I: HT 29 (54) C: HT (24 (44) |

6 |

ESC 2005 Guideline OMT according to ESC 2005 guidelines (ACEI/ARA-II, BB and diuretic) |

Decompensated HF with Hx > 24 h in the last 4 weeks | > 18 and < 80 years |

CV Mort HHF # Days for HHF |

| 2. Vuorinen et al. [38] |

I: TM with MPh App C: UC HF Clinic, edu, Self-care, self-monitoring suggestions Telephone follow-up for edu and self-care |

I: 47 C:47 |

I: 58.3 (11.6) C: 57.9 (11.9) |

I: 39 (83) C:39 (83) |

I: II 19 (40), III 27 (58), IV 1 (2) C: II 17 (36), III 28 (60), IV 2 (4) |

I: 27.3 (4.9) C: 28.6 (5) |

NR | 6 |

Systolic heart failure, NYHA ≥ 2 LVEF ≤ 35% |

< 6 mo since last visit | 18–90 years | # Days for HHF |

| 3. Kraai et al. [40] |

I: DMS guided by ICT with CDMS + TM C: DMS guided by ICT with CDMS - Computerized system for auto support. of optimization of tx. according to physiological values and medical history - edu + counseling |

I: 94 C: 83 |

I: 69 (12) C: 69 (11) |

I: 66 (70) C: 62 (75) |

I: II 21 (23) III 51 (57) IV 18 (20) C: II 18 (22) III 49 (60) IV 15 (18) |

I: 27 (9.9) C: 28 (9) |

I: Isq 45 (48) C: 35 (42) |

9 |

HF based on fluid retention sx / sto Diuretic tx requirement Evidence of structural heart disease, LVEF ≤ 45% |

Admission to ICU/CCU or cardiology floor or HF outpatient clinic | ≥ 18 years |

All cause mort HHF All cause Hx Change in HR -QoL (MLHFQ) |

| 4. Hägglund et al. [41] |

I: HIS OPTILOGG (tab) C: UC (Not HF Clinic) |

I: 32 C: 40 |

I: 75 (8) C:76 (7) |

I: (66) C: (70) |

I: II (38) II (62) C: II (18) III (82) |

NR | NR | 3 |

ESC 2012 guideline NYHA II-IV Diuretic Tx |

Current Hx | Referred to primary care (exclusion of HF Clinic follow-up) | HR-QoL (KKCQ and Swedish version of SF-36) |

| 5. Pekmezaris et al. [42] |

I: TM with American TeleCare Life View + weekly televisits C: Comprehensive outpatient management with monthly follow -up, management based on AHA 2013 guidelines |

I: 46 C: 58 |

I: 48.4 (15.2; 19–93) C: 61.1 (15; 26–90) |

I: 26 (57) C: 35 (60) |

I: II 13 (28) III 33 (72) C: II 18 (31) III 40 (69) |

NR | NR | 3 |

Primary Dx of HF NYHA I-III |

Recent Hx discharge |

≥ 18 years MMSE score ≥ 21 |

HHF All cause Hx HR-QoL (MLHFQ) |

| 6. Koehler et al. [43] |

I: Remote TM with PDA C: UC |

I: 354 C: 356 |

I: 66.9 (10.8) C: 66.9 (10.5) |

I: 285 (80.5) C: 292 (82) |

I: II 176 (49.7) III 178 (50.3) C: II 180 (50.6) III 176 (49.9) |

I: 26.9 (5.7) C: 27 (5.9) |

I: Isq 202 (57.1) C: Isq 194 (54.5) |

26 (12–28) |

Stable ambulatory chronic HF, optimal treatment according to guidelines NYHA II-III LVEF ≤ 35% |

Hx in the last 24 months or LVEF < 25% | ≥ 18 years |

All cause mort CV mort HHF All cause Hx # days for HHF # days all cause Hx HR -QoL (SF 36) |

| 7. Galinier et al. [46] |

I: TM + personalized edu (info package + calls every 3 weeks) C: UC |

I: 482 C:455 |

I: 70.0 (12.4) C: 69.7 (12.5) |

I: 354 (73.4) C: 323 (71.0) |

I: I 29 (6.1) II 210 (44.2) III 182 (38.3) IV 54 (11.4) C: I 32 (7.1) II 196 (43.4) III 185 (40.9) IV 39 (8.6) |

I: 39.3 (14.5) C: 38.1 (15.2) |

: Isq 232 (48.2) C: Isq 211 (46.5) |

18 | NR | Hx due to acute HF in ≤ 12 months |

≥ 18 years Access to telephone line or GPRS network |

All cause mort CV mort All cause Hx HHF HR—QoL (SF-36) |

| 8. Gjeka et al. [47] |

I: TM via smartP + VH app + personalized edu C: UC |

I: 47 C: 15 |

I: 68.1 C: 70 |

I: 23 (48.9) C: 10 (66.7) |

NR | NR | NR | 1.5 | Primary or secondary Dx of HF, Stage C, NYHA III-IV | NR | NR |

HHF All cause Hx |

| 9. Pedone et al. [48] |

I: Multiparametric TM with smartP + phone support C: UC (edu, monthly follow-up, telephone availability 2 h/day during the week) |

I: 47 C: 43 |

I: 79.9 (6.8) C: 79.7 (7.8) |

I: (30.2) C: (46.8) |

I: II (31.9) III (57.4) IV (10.6) C: II (32.6) III (55.8) IV (11.6) |

I: 44.4 (12.7) C: 48.2 (13.5) |

NR | 6 | Dx based on echocardiography, NT- proBNP | De novo HF in hx or as 1st dx in outpatient clinic | ≥ 65 years |

All cause mort All cause Hx |

| 10. Sahlin et al. [49] |

I: HIS—OPTILOGG (tab) close loop C: UC (HF Clinic, trimestral visits) |

I: 58 C: 60 |

I: 80 (8) C: 77 (11) |

I: 39 (67) C: 32 (53) |

I: I 6 (11) II 36 (63) III 15 (26) IV 0 (0) C: I 2 (3) II 39 (65) III 19 (32) IV 0 (0) |

NR |

I: Isq 26 (45) C: HT 27 (45) |

8 | ESC 2016 guidelines | HHF ≤ 12mo | NR |

All cause mort HHF All cause Hx # days for HHF # days all cause Hx |

| 11. Koehler et al. [25] |

I: TM Tab Physio-Gate PG 1000 + edu.(interactive and telephone) C: UC according to ESC 2016 guidelines |

I: 765 C: 773 |

I: 70 (11) C: 70 (10) |

I: 533 (70) C: 537 (69) |

I: I 3 (0) II 400 (52) III 359 (47) IV 3 (0) C: I 8 (1) II 396 (51) III 367 (47) IV 2 (0) |

I: 41 (13) C: 41 (13) |

I: Isq 301 (39) C: Isq 323 (42) |

12 |

NYHA II-III FEVI ≤ 45% o ≥ 45% with diuretic |

HHF ≤ 12mo | NR |

All cause mort CV mort HHF # days lost due to hx HR -QoL (MLHFQ) |

| 12. Dang et al. [51] |

I: TM through MPh for case assistance C: UC in HF Clinic (monthly contact and resource use questionnaire) |

I: 42 C: 19 |

I: 53 (9.4) C: 60.3 (9) |

I: 28 (66.7) C: 11 (57.9) |

I: I 19 (45.2) II 16 (38.1) III 7 (16.7) C: I 10 (52.6) II 7 (36.8) III2 (10.5) |

NR | NR | 3 | NR | Ambulatory with Hf dx |

≥ 18 years Anticipated survival ≥ 6mo |

HR-QoL (MLHFQ, and SF-36) |

| 13. Soran et al. [52] |

I: PC-based home DMS (Alere DayLink HFMS) C: UC (Specialized edu for pt and Dr.; telephone follow-up 1 m and 3 m, face-to-face 6 m; Sto and scale self- monitoring) |

I: 160 C: 155 |

I: 76.9 (7.1) C: 76 (6.8) |

I: (31.3) C: (39.4) |

I: II (57.5) III (42.5) C: II (59.3) III (40.7) |

I: 24.3 (8.8) C: 23.8 (8.7) |

I: Isq (56.9) C: Isq (53.5) |

6 |

Dx 1st or 2nd HF LVEF ≤ 40% Sto of HF (dyspnea, orthopnea, NPD, fatigue, edema) OMT according to HFSA 2006 |

Hx ≤ 6 m |

≥ 65 years Medicare beneficiary |

CV mort HHF # days all cause Hx HR -QoL (KCCQ) |

| 14. Clays et al. [53] |

I: Personal Mobile CDMS (HeartMan) C: UC According to guidelines, HF cardiologist and HF nurse |

I: 34 C: 22 |

I: 61.8 (11) C: 65.2 (9.6) |

I: 26 (76.5) C: 17 (77.3) |

I: II 26 (83.9) III 5 (16.1) C: II 20 (90.9) III2 (9.1) |

I: 32.7 (5.9) C: 31.3 (6.9) |

I: Isq 19 (55.9) C: Isq 11 (57.9) |

6 |

HF NYHA II-III LVEF ≤ 40% |

Outpatient and stable No Hx in ≤ 1mo |

≥ 18 years Adequate cognitive fun |

HR -QoL (MLHFQ) |

| 15. Dorsch et al. [59] |

I: Mobile app (ManageHF4Life) for self-management C: UC Edu, appointment 2 weeks, periodic calls by nurse |

I: 42 C: 41 |

I: 60.2 (9) C: 62 (9) |

I: 28 (67) C: 26 (63) |

I: I 1 (2) II 10 (24) III 23 (55) IV 8 (19) C: I 0 (0) II 5 (12) III 27 (66) IV 9 (22) |

I: 37.2 (20) C: 38.8 (19) |

I: Isq 19 (45) C: Isq 29 (71) |

3 | LVEF ≤ 40% or > 40% + RAE > 40 mm, BNP > 200 pg/mL or NT- proBNP > 800 pg/mL) | Hx or recently discharged due to HF decompensation | ≥ 45 years | HR -QoL (MLHFQ) |

| 16. Boyne et al. [54] |

I: TM and edu device C: UC (2005 ESC Guidelines) |

I: 197 C: 185 |

I: 71 (11.9) C: 71.9 (10.5) |

I: 115 (58) C: 111 (60) |

I: II 110 (56) III 79 (40) IV 8 (4) C: II 109 (59) III 74 (40) IV 2 (1) |

I: 36 (28–50) C: 35 (26–42) |

I: Isq 99 (50.3) C: Isq 91 (49.2) |

12 | ≥ 1 episodic edema requiring diuretics + FEVI ≤ 40% o diastolic disfunction | NR |

≥ 18 years Tx by HF cardiologist and nurse |

All cause mort HHF All cause Hx # days all cause Hx |

| 17. Kashem et al. [56] |

I: TM w-App (InSight Telehealth System) C: UC (Advanced cardiomyopathies and HF program) (Delivery of TM equipment: scale, BPM, pedometer) |

I: 24 C: 24 |

I: 53 (10) C:54 (11) |

I: (72) C: (76) |

I: II (42) III (58) IV (0) C: II (43) III (52) IV (5) |

I: 25 (3) C: 26 (3) |

I: Dil. (56) C: Isq (43) |

12 |

AHA 2001 guidelines NYHA II-IV |

≥ 1 Hx and ≤ 6 m | Internet access and basic computer skills |

Hx all cause # days All cause Hx |

| 18. Wagenaar et al. [57] |

I: UC + attention pathway adjusted to e- health (TM with e-Vita interactive platform) C1: UC + Website (Heartfailurematters.org) - Reminders to use it C2: UC (cardiologist + nurse) |

I: 150 C1: 150 C2: 150 |

I: 66.6 (11) C1: 66.7 (10.4) C2: 66.9 (11.6) |

I: 113 (75.3) C1: 112 (74.7) C2: 109 (72.7) |

I: I 69 (48.9) II 46 (32.6) III 17 (12.1) IV 9 (6.4) C1: I 57 (39.6) II 53 (36.8) III 17 (11.8) IV 17 (11.8) C2: I 57 (39.9) II 55 (38.5) III 24 (16.8) IV7 (4.9) |

I: 35.6 (11.2) C1: 35.2 (11.1) C2: 36.2 (10) |

NR | 12 |

ESC 2016 guideline ≥ 3mo since Dx |

NR |

≥ 18 years Able to fill out questionnaires and take BP and weight measurements Internet access |

All cause mort HF mort CV mort Hx HF # Days for HHF HR-QoL (MLHFQ) |

| 19. Wita et al. [58] |

I: TM with App in tab C: UC (Cardiology Clinic) |

I: 28 C: 32 |

I: 65.1 (11.7) C: 66.9 (9.3) |

I: 23 (82.1) C: 24 (75) |

NR |

I: 26.6 (7) C: 26.1 (6.7) |

I: Isq 13 (46.4) C: Isq 16 (50) |

24 | HF with reduced LVEF, candidates for CRT according to ESC 2013 guidelines | NR | NR |

All cause mort HHF |

SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range, NYHA New York Heart Association, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, HF heart failure, Hx hospitalizations, C comparator, I intervention, Tx treatment, TM telemonitoring, MPh mobile phone, UC usual care, HT hypertensive, mo months, def definition, ESC European Society of Cardiology, OMT optimal medical therapy, ACEi angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB-II angiotensin II receptor antagonist, BB beta blocker, wk weeks, mort mortality, CV cardiovascular, HHF hospitalization for heart failure, reHx rehospitalization, pt patient, WHF worsening heart failure, NR not reported, DMS disease management system, ICT information and communication technology, CDMS computerized decision making system, auto automated, edu education, Isq ischemic, Sx/sto signs and symptoms, ICU intensive care unit, CCU coronary care unit, HR-QoL health-related quality of life, MLHFQ Minnesota Living with HF Questionnaire, HIS home intervention system, tab tablet, KCCQ Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, AHA American Heart Association, Dx diagnosis, EHFScB-9 European Heart Failure Self-Care Behavior Scale, SF-36 Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, DHFKS Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale, MMSE Fol-stein Mini-Mental Status Examination, PHQ-4 Patient Health Questionnaire-4, PDA personal digital assistant, GPRS general packet radio service, smartP smartphone, VH Veta health, NT-proBNP N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide, SECD self-efficacy for managing chronic disease, HDS Health Distress Scale, CP communication with physicians, FVN visual fatigue numeric, SBVN shortness of breath visual numeric, HFSE-30 Heart Failure Self-Efficacy Scale-30, EHFSC European Heart Failure Self-Care Behavior Scale, PC personal computer, HFMS heart failure monitoring system, Dr doctor, PND dyspnea paroxysmal nocturnal, HFSA Heart Failure Society of America, SCHFI Self-Care of Heart Failure Index, RAE right atrial enlargement, Dil dilated, VAS visual analog scale, LV GLS left ventricle global longitudinal strain

Application characteristics are presented in Table 2. Regarding telemonitoring software, most involved preinstalled or web apps through a smartphone (37%, n = 7), while two (10%) included web apps not specifically designed for smartphones. Other studies included wireless tablets (21%, n = 4) or proprietary devices (31%, n = 6).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the applications

| Study | App Name/Device | Own device or downloadable application (OS) | Monitoring equipment delivered | Monitoring data | Data entry method (patient role) | Patient output | Doctor output | FdB Availability | Other fun. and observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Scherr et al. [22] | MOBITEL |

MPh w-App (Nokia 3510) IBI |

Basic electronic display Auto BPM + HR |

Weight BP HR DoM Freq: QD |

Man | None |

Continuous access to data via secured website Alarm by Email automatically if OOGM set individually or if ∆ > 2 kg TxMod: Yes. Manual, proposed by Dr |

Physician could establish MPh contact for confirmation of parameters and TxMod 24 h technical service |

Processing and graphic construction of data Data encryption, access restricted to authorized users |

| 2. Vuorinen et al. [38] | App developed by VTT Technical Research Center in Finland |

App pre-downloaded in MPh IBI |

scale BPM |

Weight BP HR Sto Overall condition Freq. ≥ 1 / week |

Man | Alarm if OOGM |

web access If OOGM, sto or changes➔ nurse contact pt to consult |

Immediate to pt through app | NR |

| 3. Kraai et al. [40] | Health- monitor |

Interactive monitor Collects data from monitoring devices via bluetooth |

scale Auto BPM ECG |

Weight BP Freq: QD ECG (every 2 weeks) Sto (Only if OOGM) |

Auto Man. Sto |

If OOGM ➔cuest de Sto Alarm. hydrosaline restriction If OOGM + Sto present = alert that you will be contacted by nurse |

Alerts by the CDMS to optimize treatment according to collected data Alarm through MPh and email if OOGM |

Contact by nurse In < 2 h in case of alarm | NR |

| 4. Hägglund et al. [41] | OPTILOGG | wl Tab | wl scale |

QD weight Sto (VAS of general condition) every 5 days |

Auto Man. Sto |

4 views: 1. Summary of weight, dosage, improvement tips 2. Disease info and lifestyle tips 3. Graphic representation of changes in weight, medication and well-being 4. HF clinic contact details and technical support Self-care tips TxMod in case of ∆ > 2 kg in 3 days Alert to consult if weight gain and no response to diuretic |

None Optional: Pt provides HIS to appointment with summary |

Telephone call by the patient to the HF clinic or technical service |

Daily weigh-in reminder Manual search for healthy lifestyle tips |

| 5. Pekmezaris et al. [42] | American TeleCare LifeView _ | Computerized monitoring device connected via wl broadband card or telephone |

Scale Rest NR |

BP SO2 Weight HR Freq. Q.D |

Man | NR |

Checked every 24 h during the week and every 72 h on weekends If OOGM, nurse notified the treating physician for TxMod or consultation to the ER |

Via telephone by nursing in case of OOGM | NR |

| 6. Koehler et al. [43] | NR | PDA with touchscreen, mobile network and bluetooth connection |

scale BPM 3-lead ECG *Accelerometer (not all) Emergency response system (Direct communication button with speaker) |

BP Weight ECG Sto Walk 6 min (only subgroup that received accelerometer Freq. Q.D |

Auto Man. Sto |

Health status identified by color code Schedule with measurements |

w-App with patient records and graphical interface Alarm according to individual parameters If health deterioration ➔call by treating Dr. In critical cases, emergency assistance |

24-h telephone emergency system Medical support 24 h / 7 days |

Data encryption |

| 7. Galinier et al. [46] | NR | Device for answering questions of sto | scale |

Weight Sto Freq. Q.D |

Auto Man. Sto |

NR | Visible alarm for nurses who contacted patients and could indicate assistance with a Dr | Contact with nurse on weekdays | Analysis by expert system with generation of alerts and prediction of decompensation |

| 8. Gjeka et al. [47] | VH: Veta Health | App downloaded in smart MPh with bluetooth |

Bluetooth BPM Bluetooth pulse oximeter Scale (Not delivered) |

Weight HR SO2 Sto Freq. Q.D |

Auto Man. for Sto and Weight |

Pop-up notifications, emails, symptom questionnaires Medication Reminders View measurement trends and edu content |

Web portal with access to all pt data Alarm if OOGM ➔coordinator (not Dr.) contacts pt and defines relevance of medical consultation |

Immediate contact with pt if OOGM |

Analysis of info for production in actionable format Deterioration risk assessment |

| 9. Pedone et al. [48] | NR |

w app smart P Android |

Basic BPM Pulse- oximeter |

Weight QD BP BID CF BID SO2 TID Sto |

Auto Man. for Sto |

Alarm for TM Alarm if OOGM |

w app daily assessment Alarm If OOGM, ➔contact pt, adherence check, early appointment, emergency room referral |

Phone support business hours to report sto or technical help | NR |

| 10. Sahlin et al. [49] | OPTILOGG | Tab. wl | scale |

Weight Sto DoM Freq. Q.D |

Auto Man. for Sto |

Alarm of deterioration for TxMod and contact with Dr | Optional if pt contributes to consultation |

Telephone support if deterioration Technical support business hours |

Interactive edu |

| 11. Koehler et al. [25] |

Physio-Gate PG 1000 Fontane Software |

wl Tab with mobile network connection Analysis system for intelligent TM |

scale BPM Pulse- oximeter ECG 3 channels |

Weight BP HR rhythm analysis SO2 Sto (health status scale 1–5) Freq. Q.D |

Auto Man. for Sto |

Availability of MPh (Doro) delivered for emergent contact |

Access by telemedical staff to the telemedical analysis system Fontane: Direct communication with pt and treating physician, TxMod, coordinate face-to-face visit or hx Access to electronic record by treating physician |

Medical support and pt management 24 h / 7d |

Algorithm to identify critical or missing values Classification in high /low risk with TM data + MR- proADM values every 3 mo Interactive edu Confidentiality |

| 12. Dang et al. [51] | Model FG 630 (MPh) | Questionnaire via web-browser message in MPh | NR |

Weight Sto (9 questions) Freq. Q.D |

Man |

Reminder to fill out questionnaire Alarm if risk of deterioration ➔contact coordinator |

Access via website to data Alarm if risk of deterioration ➔contact pt |

Coordinator establishes contact if deterioration risk Monthly telephone contact |

NR |

| 13. Soran et al. [52] | Alere DayLink HFMS | Proprietary monitor: Sto monitor system with telephone line connection | Digital scale |

Weight Sto Freq. Q.D |

Auto Man for Sto |

NR |

Access to computerized database with graphic trends Alarm if OOGM |

Daily review (365d) by nurse If OOGM: Contact pt to verify Contact a Dr. for TxMod, recommend consultation |

NR |

| 14. Clays et al. [53] | HeartMan | CDMS app on smartP (Nokia 6 TA_1021) |

scale BPM Wrist Sensor (HeartMan BITTIUM) Pill Organizer (PutTwo) |

Weight BP HR temperature FR Acceleration Freq. Q.D |

Auto |

Reminder measurements, medications and appointments Graphic presentation of data Alarm if OOGM to contact Dr |

Data and graphics web interface | Technical support business days 9am-4 pm |

Edu Exercise schemes and personalized lifestyle recommendations Psychological support (mindfulness, CBT) |

| 15. Dorsch et al. [59] | ManageHF4Life | Self-management app for smartP |

scale (Fitbit Charge 2) |

Weight Sto Freq. Q.D *TM of other variables, optional |

Auto Man for Sto |

Color-coded health status indicator (based on weight and sto) with self-management recommendations Measurement Reminder |

NR | NR | Edu |

| 16. Boyne et al. [54] | Health Buddy | Own device with display and 4 buttons | NR | Sto | Man | Dialogues of edu, behavior and sto, adaptable to the pt |

Care Desktop PC platform Access to answers and risk profiles |

Wrong answers ➔immediate correction Sto or high risk ➔contact by nurse |

Generation of risk profiles according to responses Take HR and BP during face-to-face meetings |

| 17. Kashem et al. [56] | InSight Telehealth System | w-App |

Scale Digital BPM Pedometer |

Weight BP HR Steps a day Sto (5 questions) Freq. Q.D |

Man |

Web access with unique ID Visualization of TM, laboratory and medication data Could send short messages to the Dr |

Web access to database of 10–15 patients at a time |

Nurse: web message reply in < 1 day Dr.: Could receive standard or individualized messages In an emergency, pt had to call a Dr. / hospital |

Encryption of data transfer |

| 18. Wagenaar et al. [57] | e-Vita | w-App for custom TM |

Scale BPM |

Weight BP HR Freq. Q.D Co-morbidities Medicines Freq. monthly |

Man | NR |

e-Vita Platform Alarm if OOGM or if no data registration |

Nurse: Contact pt if OOGM—> query sto, TxMod, indicate consultation | NR |

| 19. Wita et al. [58] | NR (Developed by Meditel Company in Poland) | App in tab |

Scale BPM 3-lead ECG |

Weight BP Sto Freq. Q.D ECG every week |

Man | NR | Management based on trends of previous week parameters | Possibility of teleconsultation | NR |

app application, os operating system, FdB feedback, fun functionalities, w-App web application, MPh mobile phone, IBI issued bt investigators, BPM sphygmomanometer, auto automated, HR heart rate, BP blood pressure, freq frequency, DoM dosing of medication, Q.D. once a day, man manual, OOGM out of goal measurements, ∆ change, pt patient, TxMod treatment modification, ECG electrocardiogram, Sto symptoms, quiz questionnaire, Nrs nursing, CDMS computerized decision making system, HIS home intervention system, Tab tablet, wl wireless, SO2 oxygen saturation, info information, VH Veta health, smartP smartphone, BID 2 times a day, TID 3 times a day, MR-proADM mid regional pro-adrenomedullin, msg message, HFMS heart failure monitoring system, CBT cognitive behavioral therapy

Most frequently monitored variables were weight (95%, n = 18), symptoms (79%, n = 15), blood pressure (57%, n = 11), and heart rate (42%, n = 8). Regarding data entry method, manual input was most frequent (95%, n = 18), although ten of the studied strategies (53%) reported both, manual and automatic interface using wirelessly connected external equipment (e.g., scales, blood pressure monitors, etc.). Most (n = 18) had a feedback plan; however, only 3 (16%) explicitly stated having immediate (< 2 h) support. Only 4 (21%) declared having 24 h availability.

Risk of bias assessment

RoB2 domain scores for each included study are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. Only two (10%) RCTs were ranked as low risk of bias [49, 54, 55], whereas twelve (63%) presented at least some concerns of bias with regard to outcomes such as mortality and/or hospitalization.

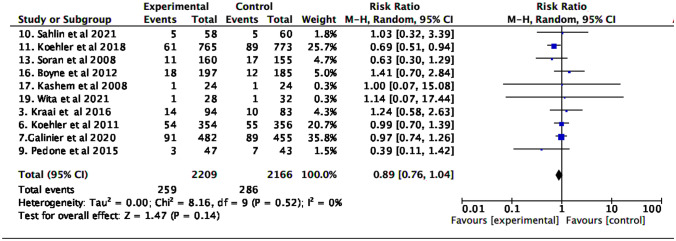

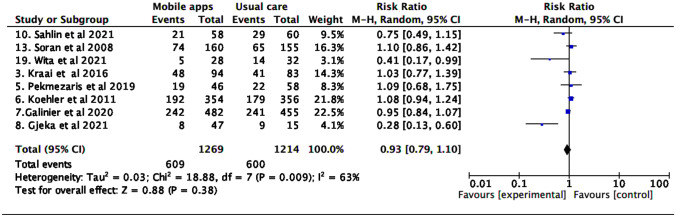

All-cause and HF-specific mortality

In the global analysis, no differences were found in the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

All-cause mortality

Fig. 3.

Cardiovascular mortality

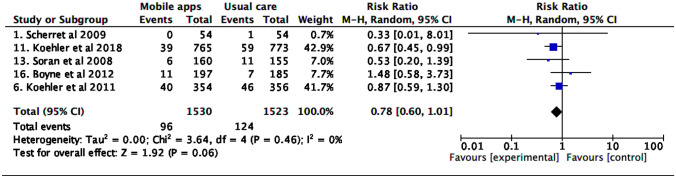

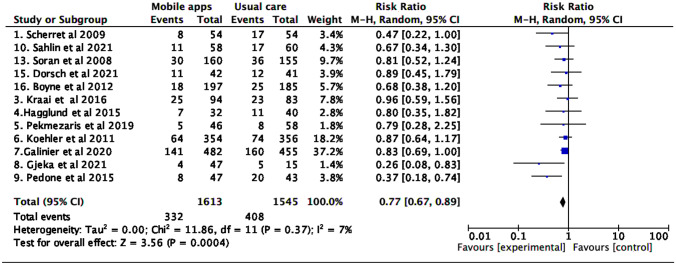

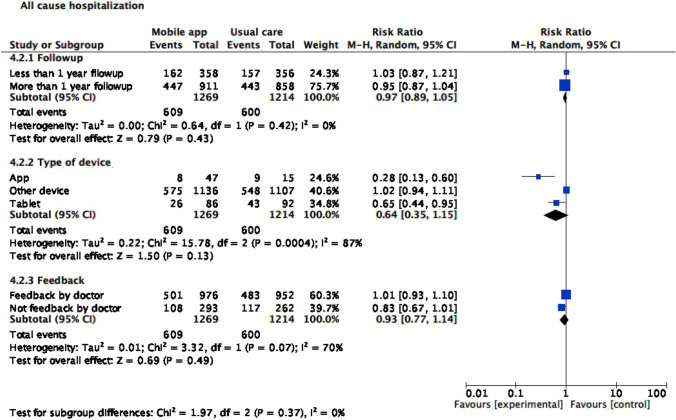

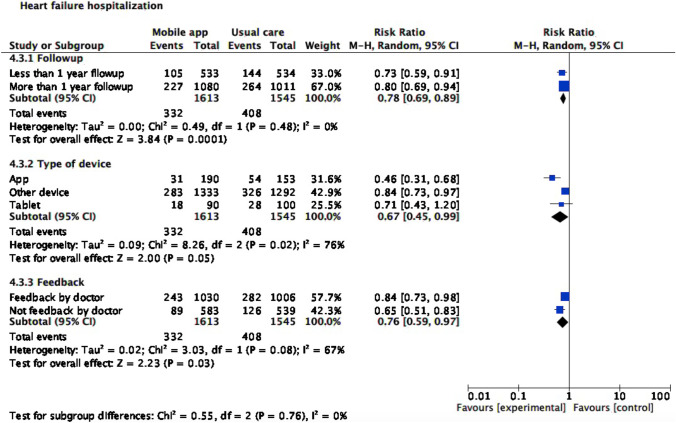

All-cause and HF-specific hospitalization rate

Tele monitoring strategies using mobile applications reduced HF hospitalization (RR 0.77 [0.67; 0.89], I2 7%). No differences were found in the risk of all-cause hospitalization (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 4.

Heart failure hospitalization

Fig. 5.

All-cause hospitalization

Quality of life

Several scores to evaluate QoL were used in included studies (n = 11) (Table 3). Most frequently used tools were MLHQ [34] (64%, n = 7), SF-36 [32] (18%, n = 2), KCCQ [33] (9%, n = 1), and EQ-5D [31] (9%, n = 1). Due to heterogeneity in effect measurement report, pooled analysis was not possible. No improvement in QoL was observed in studies using MLHQ [25, 40, 42, 53, 57, 59, 60] or EQ-5D [54], whereas studies applying SF-36 [43, 46] and KCCQ [41] reported statistically significant improvement. Noteworthy, one study was not included as it only reported QoL previous to intervention [52]; further, two studies [60, 61] measured QoL using two different tools, but only presented complete data for one tool.

Table 3.

General characteristics of studies evaluating Quality of Life

| Trial | Score used | Follow-up, months | Group | Number of patients | Initial score, media (SD) | Final score, media (SD) | Change, media (SD) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3. Kraai et al. [40] | MLHFQ | 9 | TM | 60 | 47.2 (20.6) | − 13.97 (22.311) | 0.63 | |

| Usual care | 58 | 46.3 (25.1) | − 14.63 (25.14) | |||||

| 5. Pekmezaris et al. [42] | MLHFQ | 3 | TM | 46 | 62.7 | 36.3 | 0.50 | |

| Usual care | 58 | 59.9 | 27.8 | |||||

| 11. Koehler et al. [25] | MLHFQ | 12 | TM | 649 | − 3.08 | 0.26 | ||

| Usual care | 624 | − 1.98 | ||||||

| 12. Dang et al. [51] | MLHFQ | 3 | TM | 36 | 46.7 (25.6) | 42.8 (27) | − 3.94 (26.2) | 0.43 |

| Usual care | 16 | 44.1 (24.4) | 44.8 (26.4) | 0.75 (16) | ||||

| 14. Clays et al. [53] | MLHFQ | 6 | CDMS | 34 | 32.1 (22.9) | − 1 (14.4) | 0.50 | |

| Usual care | 22 | 30 (13.5) | − 1.7 (13.8) | |||||

| 15. Dorsch et al. [59] | MLHFQ | 3 | App | 42 | 55.6 (3.5) | 44.2 (4) | 0.78 | |

| Usual care | 41 | 59.2 (3.4) | 45.9 (4) | |||||

| 18. Wagenaar et al. [57] | MLHFQ | 12 | Website | 150 | 24 (31) | 28.3 | ||

| E-Health | 150 | 23 (27.8) | 25.5 | |||||

| Usual care | 150 | 23 (32.5) | 26.5 | |||||

| 6. Koehler et al. [43] | SF-36* | 26 | TM with PDA | 354 | 54.3 (1.2) | 53.8 (1.4) | 1.7 | 0.01 |

| Usual care | 356 | 49.9(1.2) | 51.7 (1.4) | 0.3 | ||||

| 7. Galinier et al. [46] | SF-36** | 18 | TM | 482 | 37.4 (18.8) | 11.1 (21.8) | 0.03 | |

| Usual care | 455 | 39 (19.2) | 7.3(21.7) | |||||

| 16. Boyne et al. [54] | EQ-5D | 12 | Device with TM | 179 | 0.64 (0.3) | 0.65 (0.2) | 0.01 | 0.83 |

| Usual care | 173 | 0.61 (0.3) | 0.63 (0.3) | 0.02 | ||||

| 4. Hägglund et al. [41] | KCCQ’s | 3 | Wireless tablet | 32 | 50 | 65.1 | < 0.05 | |

| Usual care | 40 | 42.7 | 52.1 |

MLHFQ SF-36 short Form-36, KCCQ Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, SD standard deviation, TM telemonitoring, CDMS computerized decision making system, app application, PDA personal digital assistant

*SF 36 Physical component

**SF 36 Vitality score

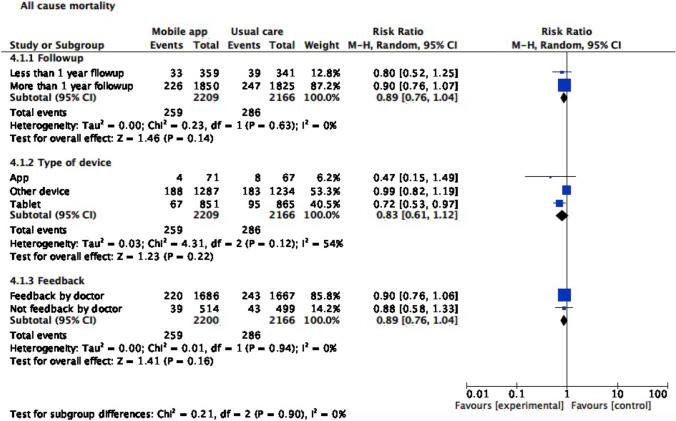

Subgroup analysis

For subgroup analyses (Figs. 6, 7, and 8), we stratified studies by follow-up length (less or more than a year), device type (Smartphone application, tablet, or other device), and feedback (by physician or not). With regard to mortality, tablet use was associated with lower all-cause mortality risk (RR 0.72, CI 95% 0.53, 0.97). Smartphone application or another device as monitoring strategy was associated with lower risk of both all-cause (RR 0.28, CI 95% 0.13,0.60 for smartphone application; RR 0.65, CI 95% 0.44,0.95 for tablet) and cardiovascular hospitalization (RR 0.46, CI 95% 0.31,0.68 for smartphone application; RR 0.84, CI 95% 0.73,0.97 for another device). Meanwhile, cardiovascular hospitalization was reduced in the intervention group, regardless of follow-up length (RR 0.78, CI 95% 0.69, 0.89) and feedback type (RR 0.76, CI 95% 0.59, 0.97).

Fig. 6.

All-cause mortality subgroup analysis

Fig. 7.

All-cause hospitalization subgroup analysis

Fig. 8.

Heart failure hospitalization subgroup analysis

GRADE

Supplementary Table 1 describes the summary of findings and evidence certainty evaluation. Certainty of evidence for both all-cause mortality and cardiovascular hospitalization was moderate, whereas for cardiovascular mortality and all-cause hospitalization was low. Certainty of evidence for QoL differed between applied tool, with high certainty level for EQ-5D (only one study), moderate for SF-36, and low for MLHFQ and KCCQ’s.

Discussion

This systematic review evaluated impact of telemonitoring strategies using mobile applications for patients with HF. We found their use reduces HF hospitalization risk (RR 0.77, [0.67; 0.89]) with low heterogeneity. No significant differences were found for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause hospitalization. Regarding QoL, several scores have been evaluated with different reporting strategies limiting pooled analysis; their impact was divergent between studies. Most studies presented at least some concerns of bias.

Most strategies that reduce hospitalization risk in patients with HF rely on pharmacologic approach [1, 62]. Nonetheless, adherence to therapy and guidelines’ recommendations are suboptimal [63, 64]. As illustrated by our results, mobile-based software for telemonitoring patients with HF may positively impact this risk. Previous meta-analyses [65, 66] including studies of home-based monitoring for patients with HF, showed these strategies reduce re-admission events, due to earlier detection of decompensation and therapeutic intervention; in addition, it promotes treatment adherence. In addition, telemonitoring strategies can reduce the frequency of unnecessary hospital visits, which has been of great importance during Covid-19 pandemic [11].

Smartphone-based apps for telemonitoring in HF are beneficial due to their wide opportunity, cheapness, and computational power [15, 16]. Current evidence suggests positive impact on treatment adherence and reduction in HF hospitalization [12, 16, 22–24]. We recently published a pilot study in 20 patients followed for 6 months at our institution using real-time telemonitoring smartphone App (“ControlVit”), in which we found that 91% of patients who used the App did not present any hospitalization event [12].

In 2016, Cajita MI et al. published a systematic literature review exploring impact of mobile phone-based interventions in patients with HF, which included 9 studies (5 were RCTs), reporting inconclusive findings regarding mortality, readmissions, hospitalization duration, QoL, and self-care [26]. The readmission risk assessment included only three studies and less than half of the patients included in the present review, possibly explaining differences with our results. Further, a more recent pooled analysis by Son YJ et al. reported mobile-based interventions had significant impact on in-hospital management duration. Nonetheless, authors did not find differences in all-cause mortality, readmissions, emergency department visits, or QoL 27. In contrast to our study, the most frequent intervention was voice-call feedback, in which an interface for telemonitoring interaction was lacking; thus, evaluated interventions were rather different.

Noteworthy, our results did not show a definite impact on mortality. Few interventions have demonstrated to reduce mortality in this patient group. Out of 19 included studies, we found that only one RCT showed reduction in mortality. Koehler et al. [25] evaluated telemonitoring using a wirelessly connected tablet, in which variables such as symptoms, vital signs and heart rate were retrieved. We hypothesize the positive impact was because feedback was available 24 h/7 days. Further, this strategy was based on an algorithm identifying critical values and able to classify patients in different risk strata [25]. New studies are needed to assess whether the potential benefits of closer feedback and automated algorithms are consistent.

Regarding evidence quality, we found most RCTs presented at least some concerns of bias. This phenomenon may be explained by a couple of reasons. As measure of QoL relies on patient’s subjectivity, it yields a high-risk of bias in the evaluation process. This limitation is less important for main outcomes such as mortality and readmission. Most studies (4/5) were considered as low risk of bias RCTs with regard to those outcomes. Remaining studies had mainly limitations on their randomization, as information concerning concealing was lacking, or due to baseline differences between study arms.

We acknowledge some drawbacks of our study. First, most studies were performed before widespread sacubitril/valsartan and iSGLT2 use, which has been one the most important advances in HF management, as it reduces mortality and hospitalization risk across the whole heart failure spectrum [1, 62, 67]. We were unable to ascertain pharmacologic treatment and patient adherence. Thus, our results may differ during foundation therapy era, as several novel agents have become first-line therapy in HF management armamentarium [1, 62]. Nonetheless, smartphone-based telemonitoring implementation is a low-cost and widely available strategy warranting further exploration in high-quality RCTs. Second, the fact we included different strategies for telemonitoring, using not only smartphone-based apps, but external devices and web-based forms, may be considered a limitation for comparisons. We recognize the heterogeneity among included mHealth interventions. However, our telemonitoring definition finds common basic characteristics, illustrating a process in which there is (1) patient input, (2) data processing, and (3) output allowing both feedback and decision-making. As smartphone availability is increasing and access to wirelessly connected external devices (e.g., smartwatch, scales) is spreading, impact of such devices on real-time data input and decision-making should be explored. For instance, data from Apple Watch® has been shown to be useful in arrhythmia detection [68]. Seeking to minimize this possible bias, we performed a subgroup analysis to assess possible heterogeneity secondary to device type without significant differences. Third, interpretation and data pooling for QoL was limited due to the use of different tools. As interest on impact of patient-reported outcomes is increasing, a call is warranted to establish a preferred tool and to standardize reporting of this outcome. This will allow data pooling in meta-analysis. In addition, novel approaches for composite outcomes analysis, such as win ratio [69], allow inclusion of QoL scores in RCTs. This approach should be considered in data analysis of RCTs evaluating telemonitoring. Fourth, follow-up times were uneven between studies, thus limiting data interpretation. Future studies on smartphone app telemonitoring should consider a minimum and ideally longer follow-up time. We acknowledge that differences in inclusion criteria and HF definition across studies make it challenging to determine in which HF subpopulations we can expect a positive effect on HF hospitalization. HF definitions have evolved over time, and future RCTs should probably include the recently proposed universal definition [30], allowing a more homogenous set of patients.

Conclusion

HF is a burdensome entity from an individual and a societal perspective. Despite widespread mobile device availability and its frequent use by patients at-risk or with established HF, mobile-based telemonitoring of HF patients is still a growing area of research. To the best of our knowledge, we offer the most comprehensive and updated systematic review on this topic, demonstrating reduction in HF hospitalization risk in patients using this strategy. Reduction in mortality risk was not statistically significant, warranting further exploration in high-quality RCTs in the foundational therapy era. Future studies on this topic should allow a better assessment of QoL.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank Pontificia Universidad Javeriana for supplying technological resources used in our construction of this original research. No other funding was received.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, material preparation, data collection, and analysis. The manuscript was drafted by Martín Rebolledo Del Toro, Nancy Muriel Herrera Leaño, and Julián Esteban Barahona-Correa; all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Colombia Consortium.

Data availability

All data will be available at request to the authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This is an observational retrospective study, considered as an investigation without risk. The protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee (approval code: 005–2022).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Martín Rebolledo Del Toro and Nancy M. Herrera Leaño contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(36):3599–3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon SD, Dobson J, Pocock S, et al. Influence of nonfatal hospitalization for heart failure on subsequent mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116(13):1482–1487. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.696906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miró Ò, García Sarasola A, Fuenzalida C, et al. Departments involved during the first episode of acute heart failure and subsequent emergency department revisits and rehospitalisations: an outlook through the NOVICA cohort. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(10):1231–1244. doi: 10.1002/EJHF.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(12):1123–1133. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2013.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barasa A, Schaufelberger M, Lappas G, Swedberg K, Dellborg M, Rosengren A. Heart failure in young adults: 20-year trends in hospitalization, aetiology, and case fatality in Sweden. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(1):25–32. doi: 10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHT278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeda A, Martin N, Taylor RS, Taylor SJC (2019) Disease management interventions for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019(1). 10.1002/14651858.CD002752.PUB4/MEDIA/CDSR/CD002752/IMAGE_N/NCD002752-CMP-003-09.PNG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Wan TTH, Terry A, Cobb E, McKee B, Tregerman R, Barbaro SDS (2017) Strategies to modify the risk of heart failure readmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 4:233339281770105. 10.1177/2333392817701050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.van Spall HGC, Rahman T, Mytton O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of transitional care services in patients discharged from the hospital with heart failure: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19(11):1427–1443. doi: 10.1002/EJHF.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flodgren G, Rachas A, Farmer AJ, Inzitari M, Shepperd S (2015) Interactive telemedicine: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(9). 10.1002/14651858.CD002098.PUB2/MEDIA/CDSR/CD002098/IMAGE_N/NCD002098-CMP-002-08.PNG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Brahmbhatt DH, Cowie MR. Remote management of heart failure: an overview of telemonitoring technologies. Card Fail Rev. 2019;5(2):86–92. doi: 10.15420/CFR.2019.5.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleland JGF, Clark RA, Pellicori P, Inglis SC. Caring for people with heart failure and many other medical problems through and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic: the advantages of universal access to home telemonitoring. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(6):995–998. doi: 10.1002/EJHF.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Achury Saldaña DM, Gonzalez RA, Garcia A, Mariño A, Aponte L, Bohorquez WR. Evaluation of a Mobile Application for Heart Failure Telemonitoring. Comput Inform Nurs. 2021;39(11):764–771. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inglis SC, Clark RA, Dierckx R, Prieto-Merino D, Cleland JGF. Structured telephone support or non-invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure. Heart. 2017;103(4):255–257. doi: 10.1136/HEARTJNL-2015-309191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frederix I, Caiani EG, Dendale P, et al. ESC e-Cardiology Working Group Position Paper: Overcoming challenges in digital health implementation in cardiovascular medicine. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(11):1166–1177. doi: 10.1177/2047487319832394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allida S, Du H, Xu X, et al (2020) mHealth education interventions in heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020(7). 10.1002/14651858.CD011845.PUB2/MEDIA/CDSR/CD011845/IMAGE_N/NCD011845-CMP-001.05.SVG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Wali S, Demers C, Shah H et al (2019) Evaluation of heart failure apps to promote self-care: systematic app Search. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7(11):e13173. 10.2196/13173, https://mhealth.jmir.org/2019/11/e13173. Accessed 27 Dec 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Ware P, Ross HJ, Cafazzo JA, Boodoo C, Munnery M, Seto E (2020) Outcomes of a heart failure telemonitoring program implemented as the standard of care in an outpatient heart function clinic: pretest-posttest pragmatic study. J Med Internet Res 22(2):e16538. 10.2196/16538. https://www.jmir.org/2020/2/e16538. Accessed 27 Dec 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Koole MAC, Kauw D, Winter MM, et al. First real-world experience with mobile health telemonitoring in adult patients with congenital heart disease. Neth Hear J. 2019;27(1):30–37. doi: 10.1007/S12471-018-1201-6/FIGURES/4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster M. HF app to support self-care among community dwelling adults with HF: a feasibility study. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;44:93–96. doi: 10.1016/J.APNR.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aamodt IT, Lycholip E, Celutkiene J et al (2019) Health care professionals’ perceptions of home telemonitoring in heart failure care: cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res 21(2). 10.2196/10362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Varnfield M, Karunanithi M, Lee CK, et al. Smartphone-based home care model improved use of cardiac rehabilitation in postmyocardial infarction patients: results from a randomised controlled trial. Heart. 2014;100(22):1770–1779. doi: 10.1136/HEARTJNL-2014-305783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scherr D, Kastner P, Kollmann A et al (2009) Effect of home-based telemonitoring using mobile phone technology on the outcome of heart failure patients after an episode of acute decompensation: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 11(3):e1252. 10.2196/JMIR.1252. https://www.jmir.org/2009/3/e34. Accessed 27 Dec 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Neubeck L, Lowres N, Benjamin EJ, Freedman SB, Coorey G, Redfern J. The mobile revolution—using smartphone apps to prevent cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(6):350–360. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creber RMM, Maurer MS, Reading M, Hiraldo G, Hickey KT, Iribarren S (2016) Review and analysis of existing mobile phone apps to support heart failure symptom monitoring and self-care management using the mobile application rating scale (MARS). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 4(2):e5882. 10.2196/MHEALTH.5882. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2016/2/e74. Accessed 27 Dec 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Koehler F, Koehler K, Deckwart O, et al. Efficacy of telemedical interventional management in patients with heart failure (TIM-HF2): a randomised, controlled, parallel-group, unmasked trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1047–1057. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31880-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cajita MI, Gleason KT, Han HR. A systematic review of mhealth-based heart failure interventions. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31(3):E10–E22. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Son YJ, Lee Y, Lee HJ. Effectiveness of mobile phone-based interventions for improving health outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1749. doi: 10.3390/IJERPH17051749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J et al (2019) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 1–694. 10.1002/9781119536604 (Published online January 1)

- 29.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/J.JCLINEPI.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bozkurt B, Coats AJS, Tsutsui H, et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition o. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(3):352–380. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/S11136-011-9903-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ware JEJ, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(5):1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rector TS (1987) Patient’s self-assessment of their congestive heart failure: II. Content, reli-ability and validity of a new measure-The Minnesota Living with Heart Failure. Heart Fail. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10005523133/. Accessed 16 June 2022

- 35.Wallace BC, Small K, Brodley CE, Lau J, Trikalinos TA (2012) Deploying an interactive machine learning system in an Evidence-based Practice Center: Abstrackr. IHI’12 - Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT International Health Informatics Symposium. 819–823. 10.1145/2110363.2110464

- 36.New York Heart Association (1994) The criteria committee for the New York heart association. Nomenclature and Criteria for Diagnosis of Diseases of the Heart and Great Vessels. Little, Brown & Co, Boston, MA, USA. (9th ed.):253–255

- 37.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A (2013) GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group. https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html. Accessed 8 Dec 2021

- 38.Vuorinen AL, Leppänen J, Kaijanranta H et al (2014) Use of home telemonitoring to support multidisciplinary care of heart failure patients in Finland: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 16(12). 10.2196/JMIR.3651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Lycholip E, Thon Aamodt I, Lie I, et al. The dynamics of self-care in the course of heart failure management: data from the IN TOUCH study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1113–1122. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S162219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kraai I, de Vries A, Vermeulen K, et al. The value of telemonitoring and ICT-guided disease management in heart failure: Results from the IN TOUCH study. Int J Med Inform. 2016;85(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/J.IJMEDINF.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hägglund E, Lyngå P, Frie F, et al. Patient-centred home-based management of heart failure. Findings from a randomised clinical trial evaluating a tablet computer for self-care, quality of life and effects on knowledge. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2015;49(4):193–199. doi: 10.3109/14017431.2015.1035319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pekmezaris R, Nouryan CN, Schwartz R, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing telehealth self-management to standard outpatient management in underserved black and Hispanic patients living with Heart Failure. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(10):917–925. doi: 10.1089/TMJ.2018.0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koehler F, Winkler S, Schieber M, et al. Impact of remote telemedical management on mortality and hospitalizations in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure: The telemedical interventional monitoring in heart failure study. Circulation. 2011;123(17):1873–1880. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.018473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koehler J, Stengel A, Hofmann T, et al. Telemonitoring in patients with chronic heart failure and moderate depressed symptoms: results of the Telemedical Interventional Monitoring in Heart Failure (TIM-HF) study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(1):186–194. doi: 10.1002/EJHF.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koehler F, Winkler S, Schieber M, et al. Telemedicine in heart failure: pre-specified and exploratory subgroup analyses from the TIM-HF trial. Int J Cardiol. 2012;161(3):143–150. doi: 10.1016/J.IJCARD.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galinier M, Roubille F, Berdague P, et al. Telemonitoring versus standard care in heart failure: a randomised multicentre trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(6):985–994. doi: 10.1002/EJHF.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gjeka R, Patel K, Reddy C, Zetsche N (2021) Patient engagement with digital disease management and readmission rates: the case of congestive heart failure. Health Informatics J 27(3). 10.1177/14604582211030959 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Pedone C, Rossi FF, Cecere A, Costanzo L, Antonelli IR. Efficacy of a physician-led multiparametric telemonitoring system in very old adults with heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(6):1175–1180. doi: 10.1111/JGS.13432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sahlin D, Rezanezad B, Edvinsson ML, Bachus E, Melander O, Gerward S. Self-care management intervention in heart failure (SMART-HF): a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Card Fail. 2022;28(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/J.CARDFAIL.2021.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koehler F, Koehler K, Prescher S, et al. Mortality and morbidity 1 year after stopping a remote patient management intervention: extended follow-up results from the telemedical interventional management in patients with heart failure II (TIM-HF2) randomised trial. Lancet Digital Health. 2020;2(1):e16–e24. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30195-5/ATTACHMENT/2C5A13F3-ADC4-4190-8315-6A3974A5F1DA/MMC1.PDF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dang S, Karanam C, Gómez-Marín O. Outcomes of a mobile phone intervention for heart failure in a minority county hospital population. Telemed J E Health. 2017;23(6):473–484. doi: 10.1089/TMJ.2016.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soran OZ, Piña IL, Lamas GA, et al. A randomized clinical trial of the clinical effects of enhanced heart failure monitoring using a computer-based telephonic monitoring system in older minorities and women. J Card Fail. 2008;14(9):711–717. doi: 10.1016/J.CARDFAIL.2008.06.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clays E, Puddu PE, Luštrek M, et al. Proof-of-concept trial results of the HeartMan mobile personal health system for self-management in congestive heart failure. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84920-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boyne JJJ, Vrijhoef HJM, Crijns HJGM, de Weerd G, Kragten J, Gorgels APM. Tailored telemonitoring in patients with heart failure: results of a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(7):791–801. doi: 10.1093/EURJHF/HFS058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gingele AJ, Ramaekers B, Brunner-La Rocca HP, et al. Effects of tailored telemonitoring on functional status and health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. Neth Hear J. 2019;27(11):565. doi: 10.1007/S12471-019-01323-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kashem A, Droogan MT, Santamore WP, Wald JW, Bove AA. Managing heart failure care using an internet-based telemedicine system. J Card Fail. 2008;14(2):121–126. doi: 10.1016/J.CARDFAIL.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wagenaar KP, Broekhuizen BDL, Jaarsma T, et al. Effectiveness of the European Society of Cardiology/Heart Failure Association website “heartfailurematters.org” and an e-health adjusted care pathway in patients with stable heart failure: results of the “e-Vita HF” randomized controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(2):238–246. doi: 10.1002/EJHF.1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wita M, Orszulak M, Szydło K, et al. The usefulness of telemedicine devices in patients with severe heart failure with an implanted cardiac resynchronization therapy system during two years of observation. Kardiol Pol. 2022;80(1):41–48. doi: 10.33963/KP.A2021.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dorsch MP, Farris KB, Rowell BE, Hummel SL, Koelling TM (2021) The effects of the ManageHF4Life mobile app on patients with chronic heart failure: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 9(12):e26185. 10.2196/26185, https://mhealth.jmir.org/2021/12/e26185. Accessed 27 Dec 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Dang S, Karanam C, Gómez-Orozco C, Gómez-Marín O. Mobile phone intervention for heart failure in a minority urban county hospital population: usability and patient perspectives. Telemed J E Health. 2017;23(7):544–554. doi: 10.1089/TMJ.2016.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Melin M, Hägglund E, Ullman B, Persson H, Hagerman I. Effects of a tablet computer on self-care, quality of life, and knowledge: a randomized clinical trial. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;33(4):336–343. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):E895–E1032. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Greene SJ, Ezekowitz JA, Anstrom KJ et al (2022) Medical therapy during hospitalization for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the VICTORIA registry. J Card Fail. 10.1016/J.CARDFAIL.2022.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, et al. Medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the CHAMP-HF registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(4):351–366. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2018.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bui AL, Fonarow GC. Home monitoring for heart failure management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(2):97–104. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2011.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Comín-Colet J, Verdú-Rotellar JM, Vela E, et al. Eficacia de un programa integrado hospital-atención primaria para la insuficiencia cardiaca: análisis poblacional sobre 56.742 pacientes. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2014;67(4):283–293. doi: 10.1016/J.RECESP.2013.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McDonald M, Virani S, Chan M, et al. CCS/CHFS heart failure guidelines update: defining a new pharmacologic standard of care for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37(4):531–546. doi: 10.1016/J.CJCA.2021.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perez Mv, Mahaffey KW, Hedlin H, et al. Large-scale assessment of a smartwatch to identify atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(20):1909–1917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA1901183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Redfors B, Gregson J, Crowley A, et al. The win ratio approach for composite endpoints: practical guidance based on previous experience. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(46):4391–4399. doi: 10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHAA665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data will be available at request to the authors.