Abstract

Infection with tissue-migrating helminths is frequently associated with intense granulocyte infiltrations. Several host-derived factors are known to mediate granulocyte recruitment to the tissues, but less attention has been paid to how parasite-derived products trigger this process. Parasite-derived chemotactic factors which selectively recruit granulocytes have been described, but nothing is known about which cellular receptors respond to these agents. The effect of products from the nematodes Ascaris suum, Toxocara canis, and Anisakis simplex on human neutrophils were studied. We monitored four parameters of activation: chemotaxis, cell polarization, intracellular Ca2+ transients, and priming of superoxide anion production. Body fluids of A. suum (ABF) and T. canis (TcBF) induced strong directional migration, shape change, and intracellular Ca2+ transients. ABF also primed neutrophils for production of superoxide anions. Calcium mobilization in response to A. suum-derived products was completely abrogated by pretreatment with pertussis toxin, implicating a classical G protein-coupled receptor mechanism in the response to ABF. Moreover, pretreatment with interleukin-8 (IL-8) completely abrogated the response to ABF, demonstrating desensitization of a common pathway. However, ABF was unable to fully desensitize the response to IL-8, and binding to CXCR1 or CXCR2 was excluded in experiments using RBL-2H3 cells transfected with the two human IL-8 receptors. Our results provide the first evidence for a direct interaction between a parasite-derived chemotactic factor and the host's chemotactic network, via a novel G protein-coupled receptor which interacts with the IL-8 receptor pathway.

Neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes have evolved in the immune system as a first line of defense against invading pathogens. Remarkable numbers of eosinophils or neutrophils infiltrate lesions caused by tissue-invading parasites, as seen, e.g., in anisakiasis (57) and schistosomiasis. A series of chemokines and low-molecular-weight attractants are known to mediate recruitment of granulocytes to the site of infection (56), but less attention has been paid to the role of parasite-derived products in inflammatory infiltration. Indeed the question of whether host innate cells bear “danger” receptors for parasite products has barely been explored. In parasitic infections, there can be phenomenal intensity and selectivity of granulocyte recruitment, such as the eosinophilic phlegmons (large granulomatous infiltrations of eosinophils with marked submucosal oedema) caused by Anisakis simplex (anisakiasis or eosinophilic gastroenteritis) (17, 28, 30, 31) and Ancylostoma caninum (eosinophilic enteritis) (52, 70). Since most of the damage caused by tissue-invading parasites can be attributed to the recruited inflammatory cells, a clear picture of the mechanisms mediating granulocyte recruitment and activation is of pivotal importance to the understanding and management of pathology.

The intensity and selectivity of inflammatory recruitment suggest that granulocytes are not simply responding to tissue injury caused by migrating larvae, but are actively targeting or being targeted by the parasites in question. Numerous parasite-derived chemotactic factors (PDCFs) have been reported to recruit, often selectively, neutrophils (neutrophil chemotactic factors [NCFs]) or eosinophils (eosinophil chemotactic factors [ECFs]) (20, 26, 43, 46–48, 51, 67, 68). Few of those, however, have been identified and cloned (20, 45). Moreover, no study has yet addressed the nature of the host cell receptors involved in this process despite the recognized importance of innate system receptors. Here, we present the first evidence that a neutrophil chemokine or related receptor may be involved in this response. Previous studies addressing granulocyte chemotaxis induced by PDCFs used granulocyte preparations with various degrees of purity from peritoneal exudate cells of guinea pigs treated with oyster glycogen or horse serum (26, 67, 68). From these studies, it is not clear to what extent the cells used were immunologically primed or contaminating cells played a role as a secondary source of chemotactic factors.

Chemoattractants have been divided into two categories by Haines et al. (23). The main category is represented by the classical chemoattractants such as formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP), platelet-activating factor (PAF), leukotriene B4 (LTB4), and C5a. The isolation of interleukin-8 (IL-8) (59) over a decade ago heralded a new group of chemoattractant molecules, the chemoattractant cytokines (chemokines) (4, 5, 54, 58), and their receptors (37, 42, 58, 72). Both classical chemoattractants and chemokines act on target cells through seven-transmembrane-domain receptors that are coupled to heterotrimeric G proteins (42). Their engagement by an agonist results in a panoply of possible functional cellular responses, most of which are rapid and transient, e.g., a characteristic rise in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) (4), polymerization and depolymerization of actin filaments (15, 73), generation of reactive oxygen species (16), and bioactive lipids (e.g., PAF and LTB4) (6, 55), priming of superoxide anion production (e.g., by PAF and tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]) (19, 29), and transendothelial migration (64). The second category is represented by the so-called pure chemoattractants and includes substance P (23), fibrinopeptide B (62), transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) (23, 53), and Fas ligand (FasL) (44, 61). These chemoattractants are active at extremely low concentrations (TGFβ1 at femtomolar and FasL at pico- to nanomolar concentrations) (44, 61) and do not elicit a transient [Ca2+]i increase or any degranulation (44, 53) or superoxide anion production at any concentration (23, 62). With respect to their receptors, pure chemoattractants bind to G protein-coupled receptors (substance P) (23) as well as to different receptors such as Fas (CD95 and Apo-1), the receptor for FasL (44). In this study, we demonstrate for the first time that the previously described NCF from Ascaris suum (68) exerts classical-like activities on human neutrophils, since its effects on target cells include pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive Ca2+ mobilization, shape change, priming of superoxide anion production, and in vitro chemotaxis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites and extracts.

Parasite body fluids were obtained from the adult stages of A. suum (Ascaris body fluid [ABF]) and Toxocara canis (T. canis body fluid [TcBF]) from naturally infected pigs and dogs, respectively. Body fluid was collected by an incision in the cuticle. The body fluids were then microcentrifuged at 16,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min, and the supernatants were stored at −70°C. Third-stage larvae of Anisakis simplex were obtained by dissection of fresh, unfrozen mackerel (Scomber scombrus) or herring (Clupea harengus) from the North Sea. Somatic extracts of A. simplex (AnX) were obtained by snap-freezing the larvae in liquid nitrogen and grinding them to a fine powder in a mortar; 10 g of powder was extracted with 20 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) at room temperature for 30 min. The extracts were then microcentrifuged at 16,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min, and the supernatants were stored at −70°C. All protein concentrations were determined with the Coomassie Plus protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) as directed.

Purification of granulocytes.

Neutrophils or eosinophils were purified from freshly drawn peripheral blood of healthy donors (71). Briefly, granulocytes were obtained via a two-stage protocol consisting of dextran sedimentation and a three-step isotonic discontinuous Percoll gradient (55, 70, and 81%) centrifugation. The cells derived from the 55 to 70% interface were 95 to 99% neutrophils. Eosinophils were purified from the neutrophil-rich interface by a negative immunomagnetic selection step using sheep anti-mouse immunoglobulin G Dynabeads, coated with murine anti-CD16 (3G8; kind gift of J. Unkeless, Mount Sinai Medical School, New York, N.Y.). Final purities were 95 to 99% for neutrophils and >99% for eosinophils, as assessed by cytospins stained with Diff-Quik (Dade Diagnostika, Unterschleissheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Viability (trypan blue dye exclusion) was at least 99% for both cell types. All buffers used during purification were Ca2+- and Mg2+-free.

Chemotaxis experiments.

Chemotaxis assays were performed in a 96-well modified Boyden chamber (Neuro Probe, Gaithersburg, Md.). Positive and negative controls in the bottom wells as well as the granulocyte suspension in the upper wells were in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom) with 0.3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom). The polyvinylpyrrolidone-free polycarbonate membranes (Neuro Probe) had a 3-μm pore diameter. As pointed out by Wilkinson (74), a source of error with this technique is the potential aggregation of cells during migration, resulting in adhesion to the lower surface of the filter rather than to the bottom wells. Therefore, both the cells adhering to the lower surface of the filter and the cells migrating to the bottom wells were measured as described below. Neutrophil suspension (200 μl, 107/ml) was added to the top wells, and the chemotaxis chamber was incubated at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2 for 45 min. The chemotaxis chamber was then carefully disassembled, and the upper side of the filter was washed with PBS, scraped with a cell scraper to remove adherent cells, fixed with methanol, and stained with Diff-Quik. The stained filters were measured in a 96-well spectrophotometer at 550 nm. The cells that had migrated into the bottom wells were counted in five high-power fields with a light microscope in a modified Neubauer hematocytometer. All treatments in each chemotaxis experiment were performed in triplicate. Chemotaxis was expressed as the chemotactic index (C.I.), defined as the number of cells migrating in the presence of the sample divided by the number of cells migrating in the presence of medium only.

Measurement of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration.

Ca2+ mobilization was measured with Fura-2 according to the following protocol. Purified neutrophils or eosinophils were resuspended at a density of 107/ml in Ca2+-Mg2+-free HBSS–0.3% BSA without phenol red and incubated in a waterbath at 37°C (for all RBL-2H3 experiments at room temperature) in the presence of 2 μM Fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.), followed by two washes in the above medium. Stable transfectant RBL-2H3 cell lines expressing the human CXCR1 or CXCR2 receptor (generously provided by Ingrid Schraufstätter, La Jolla Institute for Experimental Medicine) were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Sigma), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin, (100 μg/ml), gentamicin (50 μg/m), and G418 (0.5 mg/ml) (Promega, Madison, Wis.). The Fura-2-loaded cells were then resuspended at a density of 2 × 106/ml in optical methacrylate (PMMA) disposable cuvettes (Kartell; Merck, Poole, United Kingdom) in 2.5 ml of HBSS–0.3% BSA with Ca2+ and Mg2+. Ca2+ mobilization into the cytosol was monitored at 340 and 380 nm (excitation) and 510 nm (emission) with a spectrofluorimeter (FluoroMax; Spex Industries, Edison, N.J.) using the dM3000 Software (Spex Industries). Ca2+ concentrations were calculated using the Grynkiewicz equation (22). For PTX inhibition experiments, purified cells were incubated for 90 min at 37°C at a density of 107/ml in HBSS–0.3% BSA in the presence of PTX (2 μg/ml) (Alexis Corp., San Diego, Calif.) before loading with Fura-2.

Measurement of neutrophil polarization.

Shape change was assessed using a modification of the method described by Kitchen et al. (34): 90 μl of a 106/ml suspension of neutrophils in HBSS–0.3% BSA was incubated at 37°C in a shaking waterbath for 15 min in the presence of 10 μl of buffer or sample. The cells were then fixed by adding 100 μl of 2.5% glutaraldehyde in saline. Samples were analyzed for shape change by flow cytometry (EPICS Profile II; Coulter Electronics, Luton, United Kingdom). Percent shape change was determined by analyzing the whole cell population and gating on the mean forward light scatter of the non-shape-changed cells.

Superoxide anion production and priming experiments.

Superoxide anion production of neutrophils was assessed with dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR123) as described by Stocks et al. (65). Cells were incubated at a density of 106/ml in HBSS–0.3% BSA with 1 μM DHR123 (Molecular Probes) for 5 min at 37°C before adding a stimulus or buffer. The cells were then incubated for 12 min at 37°C in a shaking waterbath and immediately placed on ice. For the priming experiments, cells were incubated for 10 min at 37°C prior to incubation with DHR123. Superoxide anion production was analyzed by flow cytometry (EPICS Profile II) by detecting fluorescence in the green channel due to the conversion of DHR123. Data were expressed as mean fluorescence intensity of the totality of cells in the sample. For the priming experiments, any potential lipopolysaccharide (LPS) contaminants in ABF were removed with polymyxin B-Sepharose (Detoxi-Gel AffinityPak Prepacked columns; Pierce and Warriner, Cheshire, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

S-300HR gel filtration.

ABF (1 ml) was spun at 16,000 × g in a microcentrifuge for 10 min and applied at 5 mg/ml with 5% glycerol to the column (flow rate, 0.33 ml/min). Following the elution of the void volume, 40 to 45 fractions (2 ml/fraction) were collected. Protein eluting from the column was monitored by absorbance at 280 nm.

Statistics.

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of n separate experiments, performed in duplicate or triplicate. The paired t test was used for comparison of different treatments, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

A. suum and T. canis but not A. simplex induce a strong chemotactic response in human neutrophils.

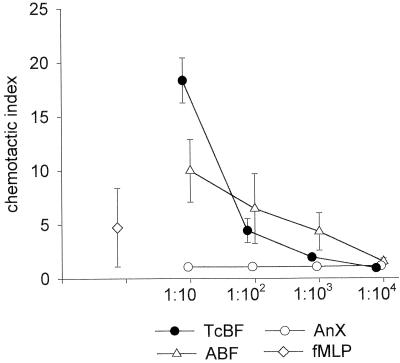

The induction of chemotaxis in unprimed, high-purity populations of neutrophils obtained from peripheral blood of healthy human donors was tested using a 96-well chemotaxis chamber, and the extent of migration was assessed by counting the cells that migrated to the bottom wells. ABF and TcBF both induced a strong dose-dependent chemotactic response within the protein concentration range from 500 μg/ml to 500 ng/ml (Fig. 1). Checkerboard titration experiments with ABF confirmed that the enhanced neutrophil migration was chemotactic rather than chemokinetic (data not shown). Somatic extracts of A. simplex (AnX), however, did not elicit a measurable chemotactic response in the same protein concentration range.

FIG. 1.

In vitro chemotaxis of human neutrophils induced by products of ascarid nematodes. TcBF and ABF but not AnX, induced strong and dose-dependent granulocyte migration. Isolated neutrophils (107/ml) were added to the top wells of a multiwell chemotaxis chamber, and serial dilutions were added of the samples to the bottom wells. Protein concentrations were 500 μg/ml (1:10) to 500 ng/ml (1:104) for TcBF and ABF and 1,000 μg/ml (1:10) to 1,000 ng/ml (1:104) for AnX. fMLP was used at 10 nM, as higher concentrations led to strong aggregation of the neutrophils in the filter concurrent with a loss of migration to the bottom wells. Values represent the mean ± SD of three separate experiments with different donors performed in triplicate. SD values falling within the symbols are not shown.

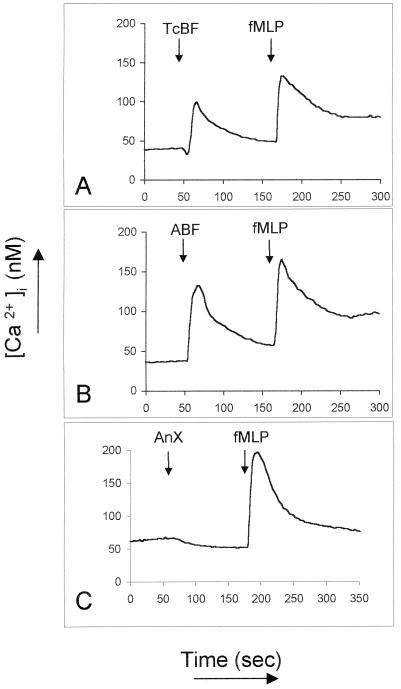

ABF and TcBF induce transient intracellular Ca2+ ion elevations in neutrophils.

Since classic chemotactic factors such as C5a and chemokines induce [Ca2+]i transients upon engagement of their receptors (3, 22), we asked whether ABF and TcBF, in addition to their chemotactic effect on neutrophils, also mobilize Ca2+ ions in Fura-2-loaded cells. As shown in Fig. 2, both ABF and TcBF induced a rapid, strong, and transient elevation of [Ca2+]i in neutrophils when used at 50 μg/ml. The intensity of the Ca2+ mobilization was dose dependent and still detectable with ABF diluted 1:104 (total protein concentration of 5 μg/ml; data not shown). ABF also mobilized Ca2+ in purified peripheral blood eosinophils, although more weakly (data not shown), and in the human monocytic cell line THP-1, which is known to bear one or more IL-8 receptors (data not shown). Consistent with its lack of chemotactic activity on neutrophils, AnX did not increase [Ca2+]i up to a protein concentration of 250 μg/ml.

FIG. 2.

Mobilization of [Ca2+]i in human neutrophils by products of ascarid nematodes. TcBF and ABF (50 μg/ml) but not AnX (250 μg/ml) induced rapid and strong Ca2+ transients in the cytosol of purified neutrophils. Each experiment was repeated with at least three different donors with comparable results.

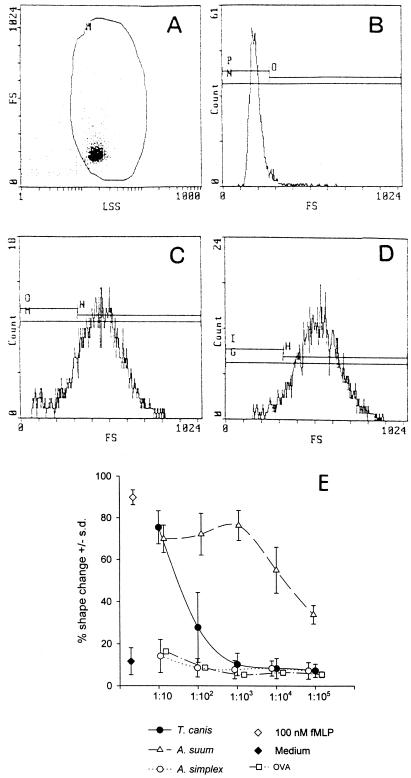

ABF and TcBF induce rapid and reversible shape change in neutrophils.

A very dramatic effect elicited in target cells upon binding of chemotactic factors to their receptors is the phenomenon of cell polarization. Within a few minutes, a cell that has encountered an appropriate chemotactic stimulus changes from a spherical to a highly polarized morphology (24). The shape change can be visualized under a light microscope (10) or more conveniently assessed by recording the increase in the forward angle light scatter in a flow cytometer (10, 63). Figures 3A to D show representative flow cytometry histograms of untreated neutrophils (A and B) or neutrophils treated with 100 nM fMLP (C) or ABF at 50 μg/ml (D) for 15 min, demonstrating the strong shape change of neutrophils incubated with parasite products. Figure 3E shows the effect of serial dilutions of ABF, TcBF, and AnX on the shape of neutrophils, expressed as the percentage of cells affected. A nonchemotactic protein (chicken ovalbumin) was included to control for nonspecific effects of high protein concentrations. Neither ovalbumin (from 5 mg/ml to 50 ng/ml) nor AnX had a significant effect on the shape of neutrophils, whereas ABF and TcBF caused strong and dose-dependent shape change comparable to the intensity caused by 100 nM fMLP. ABF-induced shape change could be detected with dilutions of up to 1:106 (corresponding to approximately 50 ng of total protein per ml) but was only detectable at higher concentrations with TcBF (500 and 50 μg/ml). Shape change induced by ABF was rapid, beginning within seconds and peaking within 5 to 15 min, depending on the donor, and reverting to basal level within 30 to 60 min (data not shown). This profile is very similar to the time course of shape change elicited by PAF (34) and IL-8 (F. H. Falcone and A. G. Rossi, unpublished data) and clearly different from the time course of shape change caused by, e.g., TNF-α or LPS (34).

FIG. 3.

Flow cytometry histograms illustrating the shape change of unprimed isolated neutrophils induced by different samples. Neutrophils were incubated with the stimuli at 37°C and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde after 15 min. The autofluorescence or forward scatter of the cells was monitored on a Coulter EPICS II flow cytometer; plots show forward scatter (FS) against log side scatter (LSS). (A and B) Unprimed, unstimulated neutrophils; (C) ABF (500 μg/ml); (D) 100 nM fMLP. (E) ABF and TcBF but not AnX induce strong and reversible shape change in neutrophils. Dose-response curves obtained with the parasite products and controls. Shown are the results of three independent experiments performed in duplicate with different donors, expressed as mean percentage of cells that have undergone shape change ± SD. Also shown are 100 nM fMLP and the background shape change of unstimulated neutrophils. Protein concentrations were: ABF, TcBF, and AnX, 500 μg/ml (1:10) to 50 ng/ml (1:105); ovalbumin (OVA), 5 mg/ml (1:10) to 500 ng/ml (1:105).

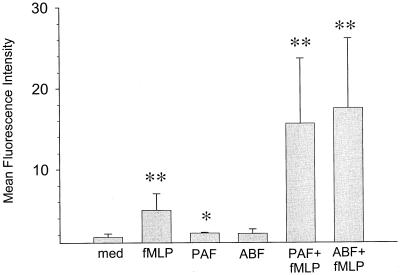

ABF effectively primes neutrophils for fMLP-induced superoxide production.

Several factors, such as IL-8, are known to induce an oxidative burst in neutrophils, evident in the production of superoxide anion (32). The induction of the oxidative burst, however, depends on the state of preactivation (priming) of the neutrophils by inflammatory factors such as PAF, TNF-α, and LPS (49). While these factors do not themselves stimulate an oxidative burst, they considerably increase this response upon a second stimulation, e.g., with fMLP (19, 29). We therefore asked whether ABF, in addition to causing Ca2+ mobilization, shape change, and directional movement of neutrophils, can also prime neutrophils for enhanced superoxide anion production. Figure 4 shows the results of the oxidative burst analysis with DHR123. Treatment of neutrophils with 10 nM PAF or ABF (50 μg/ml) led to only a slight increase in superoxide anion production which was not significantly higher than in the unstimulated control. fMLP at 10 nM led to a 2.9-fold increase. Priming with 10 nM PAF 15 min prior to exposure to 10 nM fMLP led to a ninefold increase over the spontaneous oxidative activity. A similar increase (10.2-fold) was obtained when neutrophils were preincubated with ABF (50 μg/ml), showing that ABF, without inducing an oxidative burst itself, can efficiently prime neutrophils for superoxide anion production. ABF retained its priming efficiency after treatment with a polymyxin B-Sepharose column, excluding putative contamination with LPS as a possible source of priming (data not shown). Maximal (92-fold) increase was obtained with 100 nM phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (not shown).

FIG. 4.

ABF primes purified neutrophils for superoxide anion production. Cells were incubated at 37°C with the putative priming factors or buffer (med) for 10 min, loaded for 5 min with DHR123, and incubated for 12 min with the following stimuli: 100 nM PAF, 100 nM fMLP, ABF (500 μg/ml), or 100 nM PMA. Superoxide anion production was then measured. Values represent the mean total fluorescence ± SD for five independent duplicate determinations with different donors. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.001.

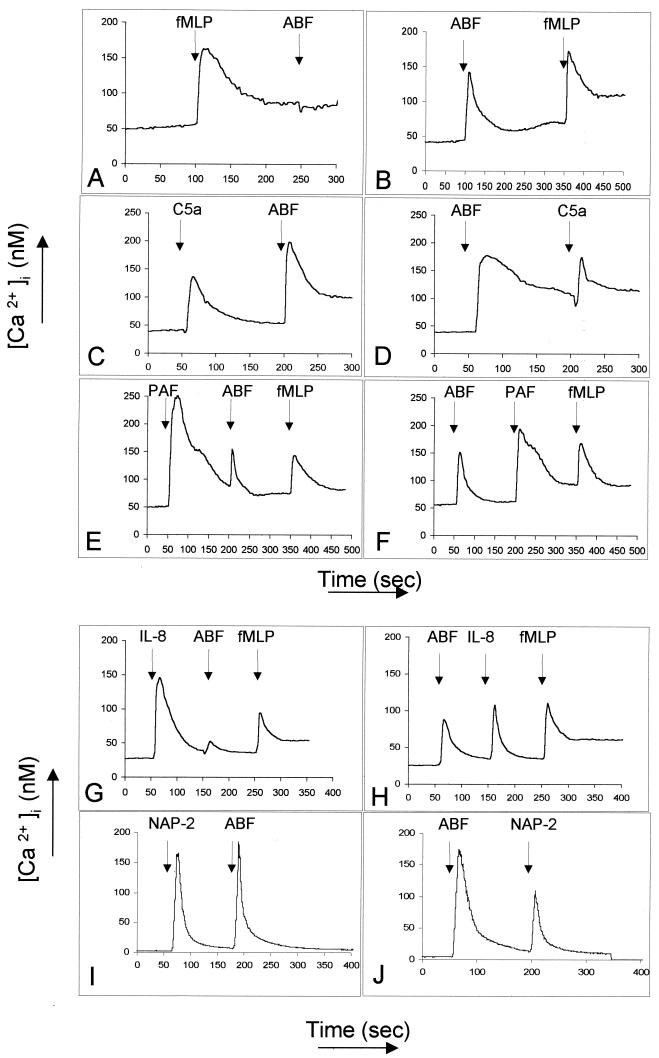

fMLP and IL-8 desensitize the Ca2+ mobilization induced by ABF.

Our next set of experiments were designed to characterize the putative receptor mediating the effects of ABF on neutrophils. These experiments exploit the phenomenon of receptor cross-desensitization. Homologous desensitization is caused by a decreased affinity of the receptor-ligand complex for G proteins and its subsequent internalization in an arrestin-dependent process, resulting in a lower response upon restimulation with the same stimulus (3). Heterologous desensitization is not dependent on receptor internalization and occurs when a receptor loses responsiveness as a consequence of a ligand's binding to a different receptor (3). Figure 5 illustrates different combinations of chemoattractant stimuli relevant to neutrophils with ABF. When neutrophils are first stimulated with 100 nM fMLP, the increase in [Ca2+]i in response to ABF is completely abrogated (Fig. 5A), whereas 10 nM C5a (Fig. 5C and D) and 100 nM PAF (Fig. 5E and F) do not affect the response significantly. Interestingly, 100 nM recombinant IL-8 almost totally desensitized the response to ABF (50 μg/ml) (Fig. 5G). ABF (50 μg/ml) partially desensitized the responses to 100 nM IL-8 (Fig. 5H) and 100 nM PAF (Fig. 5F) but not to 10 nM C5a (Fig. 5D) or 100 nM fMLP (Fig. 5B), and 100 nM neutrophil activation protein 2 (NAP-2), which is known to bind with high affinity to the chemokine receptor CXCR2 and to CXCR1 with 200-fold-lower affinity (36), did not desensitize the response to ABF (50 μg/ml) (Fig. 5I). Interestingly, pretreatment with ABF (50 μg/ml) led to a partial (about 30%) but consistent desensitization of the response to 100 nM NAP-2 (Fig. 5J). When used in lower concentrations, fMLP (≤5 nM) failed to desensitize the response to ABF (Fig. 6B). We also found that ABF and TcBF cross-desensitized each other's induction of Ca2+ mobilization in neutrophils (data not shown). Taken together, the desensitization studies point to interactions between the receptors for fMLP (fMLP-R) and IL-8 (CXCR1 and CXCR2) in the Ca2+ mobilization response to ABF. To further explore this possibility and to assess the potential role of other receptors, we performed a second set of experiments using specific receptor antagonists.

FIG. 5.

Cross-desensitization experiments with ABF (50 μg/ml) and the main chemotactic factors for neutrophils. Ca2+ influx was monitored with Fura-2-loaded neutrophils. (A) Desensitization of the response to ABF by 100 nM fMLP. (B) There was no cross-desensitization between 10 nM C5a and ABF (C and D), and 100 nM PAF also failed to desensitize the response to ABF as well as to 100 nM fMLP (E and F). (G) Desensitization of ABF-induced Ca2+ influx by IL-8. (H) Partial desensitization of the response to IL-8 by ABF. (I) Pretreatment with 100 nM NAP-2. (J) Partial (∼30%) desensitization of the response to 100 nM NAP-2 by ABF. Comparable results were obtained in at least three separate experiments with different donors.

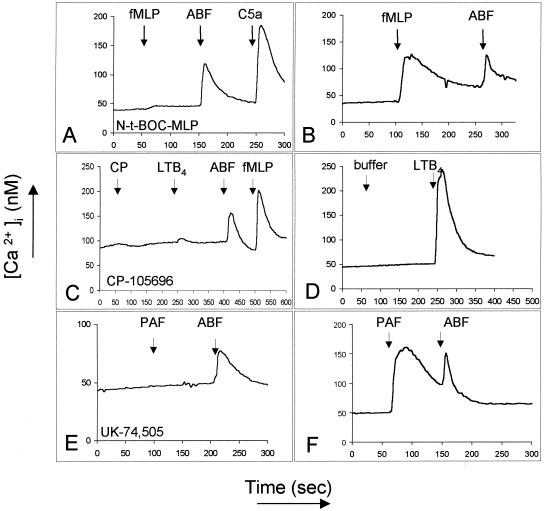

FIG. 6.

Receptor-antagonist experiments with ABF (50 μg/ml) and specific antagonists of the receptors for fMLP (5 mM Nt-BOC-MLP, 5 min of incubation), LTB4 (5 μM CP-105,696, 3 min of incubation), and PAF (1 μM UK-74,505, 5 min of incubation). These experiments were repeated at least three times with different donors and comparable results.

Specific antagonists of fMLP-R, PAF-R, and LTB4-R do not inhibit ABF-induced Ca2+ mobilization.

Figure 6 shows the results of incubation of neutrophils with specific antagonists. Neutrophils incubated with 5 mM N-t-BOC-MLP for 5 min prior to stimulation lost responsiveness to 10 nM fMLP but still responded fully to ABF (Fig. 6A and B). A 3-min incubation with 5 μM CP-105,696 (kind gift from Henry Showell, Pfizer, Groton, Conn.), a specific antagonist of the LTB4-R (36), blocked the response to 10 nM LTB4 but not to ABF or fMLP (Fig. 6C). A 5-min incubation with the PAF-R antagonist UK-74,505 (2) (kind gift of J. Parry, Pfizer, Sandwich, U.K.) at 1 μM, shown in Fig. 6E, also failed to inhibit the response to ABF. These results exclude a role of the receptors for fMLP, PAF and LTB4 in ABF-induced Ca2+ mobilization. Taken together, the desensitization and receptor antagonist studies suggest that the effect of ABF on neutrophils may be mediated via one of the receptors for IL-8, i.e., CXCR1 or CXCR2.

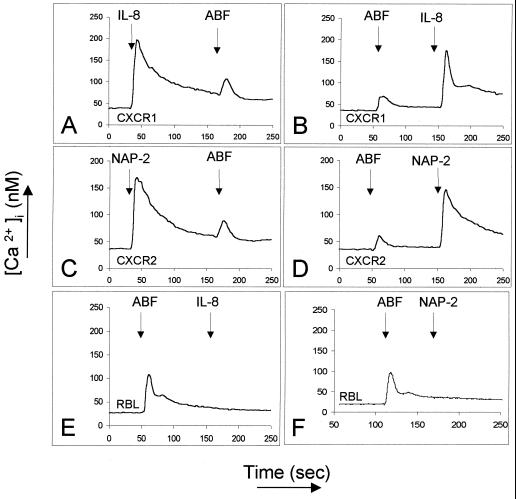

[Ca2+]i transients in CXCR1 and CXCR2 transfectants are not desensitized by IL-8 or NAP-2.

To further investigate the putative role of the IL-8 receptors in Ascaris-dependent chemotaxis, we monitored the mobilization of intracytosolic Ca2+ fluxes in RBL-2H3 cells transfected with either CXCR1 or CXCR2. As shown in Fig. 7, RBL cells transfected with CXCR1 responded to IL-8 (10 nM, Fig. 7A), whereas RBL-2H3 cells transfected with CXCR2 responded to NAP-2 (100 nM, Fig. 7C). Nontransfected RBL-2H3 cells did not respond to either chemokine. Unexpectedly, nontransfected RBL-2H3 cells showed a weak but consistent response to ABF, implicating a novel, endogenous receptor present on the rat cells (Fig. 7E and F). Significantly, there was no cross-desensitization between ABF and IL-8 (Fig. 7A and B) on CXCR1 transfectants or between ABF and NAP-2 (Fig. 7C and D) on CXCR2 transfectants, excluding these receptors from being the target of the NCF in ABF on human neutrophils. In addition, it was found that extended trypsin treatment of the transfectant cell lines (45 min at 37°C) completely ablated the response to ABF but did not reduce the response to IL-8 or NAP-2 (data not shown), lending further support to the proposition that a distinct receptor may mediate Ascaris-dependent chemotaxis in human neutrophils.

FIG. 7.

Ca2+ mobilization by ABF in RBL-2H3 cell lines stably transfected with human CXCR1 (A and B) or CXCR2 (C and D). ABF induces a weak Ca2+ mobilization (via an endogenous receptor) in nontransfected as well as in transfected cell-lines (A to F), which is not desensitized by IL-8 (10 nM, A and B) or NAP-2 (100 nM, C and D). The nontransfected RBL cell line does not respond to the human chemokines (E and F). These experiments were repeated at least four times with comparable results.

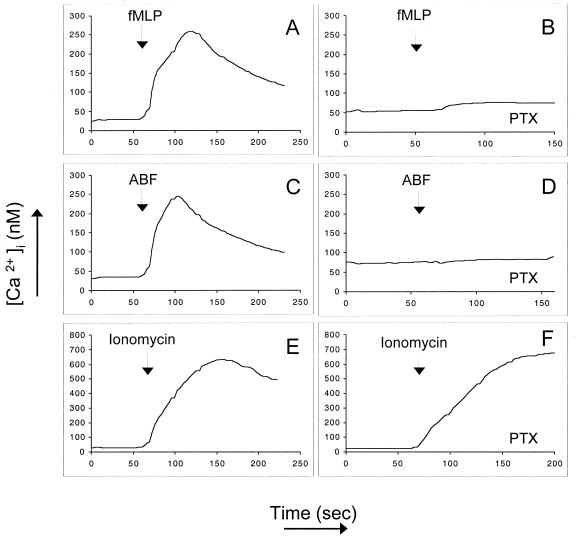

Inhibition of Ca2+ mobilization in neutrophils by PTX treatment.

Since classical chemotactic receptors are coupled to heterotrimeric, pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins, we investigated the effect of treatment with PTX (2 μg/ml) on ABF-induced mobilization of Ca2+. Figure 8 shows purified neutrophils stimulated with 10 nM fMLP without (Fig. 8A) or after PTX treatment (Fig. 8B), which leads to a total inhibition of Ca2+ mobilization. ABF-induced Ca2+ mobilization (Fig. 8C) was also totally abrogated by PTX (Fig. 8D). Pretreatment with PTX, however, did not affect the influx of Ca2+ induced by 10 nM ionomycin, showing that the cells are still fully responsive (Fig. 8E and 8F).

FIG. 8.

Effect of pretreatment with PTX (2 μg/ml) on ABF-induced mobilization of Ca2+. Neutrophils were stimulated with 10 nM fMLP without (A) or with PTX pretreatment (B). ABF-induced Ca2+ mobilization (C) was totally abrogated by PTX (D). Pretreatment with PTX did not affect the Ca2+ influx induced by 100 nM ionomycin (E and F). The data are representative of three experiments with the same results.

Fractionation of Ascaris body fluid.

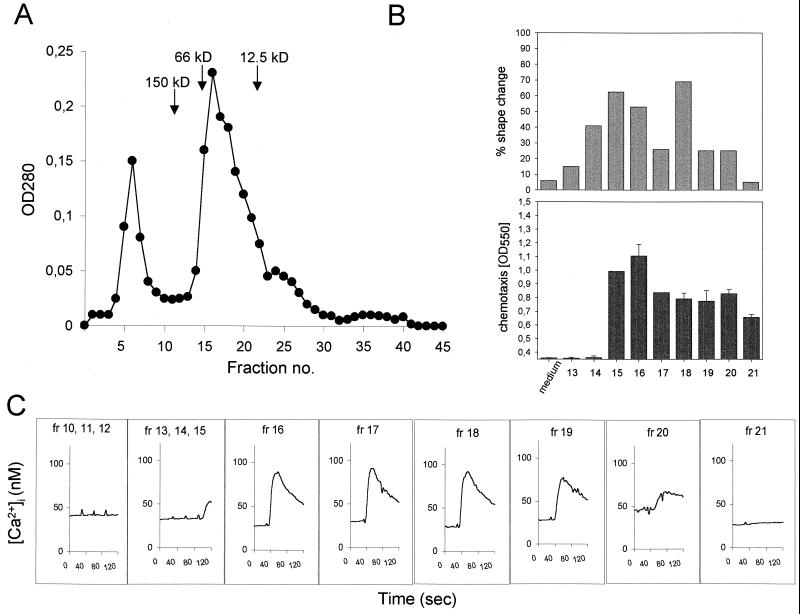

Previous work performed with ABF led to the identification and biochemical characterization of separate molecular entities attracting neutrophils and eosinophils (68). Both NCF and ECF had an approximate size of 30 kDa. The neutrophil chemotactic fraction could be further separated into two distinct NCFs by isoelectric focusing (pIs of 5.2 and 7.6), which are possibly isoforms. We have performed a preliminary separation of ABF by size exclusion chromatography and tested whether, upon separation, Ca2+ mobilization, shape change, and chemotactic activity were coincident with a particular fraction. Activity in all three parameters was found exclusively in 5 of 45 fractions corresponding to an apparent mass ranging between 12.5 and 66 kDa (Fig. 9). These results precisely match the distribution of chemotactic activity described by Tanaka et al. (68). Since up to 50% of the protein of ABF is known to be made up by ABA-1, a retinoid and fatty acid-binding protein with a mass of 14.4 kDa (33), we asked whether ABA-1 could induce comparable immunologic effects in purified human neutrophils. ABA-1 is also known to occur as a dimer with an approximate mass of 30 kDa and has a predicted isoelectric point of 7.55. Both physicochemical characteristics of ABA-1 are very close to the properties of one of the two NCFs described by Tanaka et al. (68). Since a homologue of ABA-1 in Dirofilaria immitis is chemotactic for neutrophils (11, 45) and the primary amino acid sequence of a variant of ABA-1 contains an ELR motif (41), which is well known to play an important role in neutrophil chemotaxis (25), ABA-1 is the top candidate as a putative NCF. We therefore tested parasite-derived purified (by size exclusion chromatography with fast protein liquid chromatography) and recombinant (obtained as described [39]) ABA-1 (both kindly provided by M. W. Kennedy, Glasgow, U.K.) in the Ca2+ mobilization and chemotaxis assays. Neither form of ABA-1 elicited Ca2+ mobilization (tested at 20 μg/ml; data not shown) in purified neutrophils or showed significant dose-dependent chemotactic activity in our in vitro assay (range, 500 μg/ml to 500 ng/ml), except for a comparably small increase in neutrophil migration with the highest concentration of the parasite-derived ABA-1 (C.I = 2; data not shown). The fact that only 500 μg of purified but not recombinant ABA-1 per ml induced neutrophil chemotaxis without eliciting measurable Ca2+ mobilization seems to indicate that the increased migration of neutrophils was caused by contaminants of similar size (which were known to be present) in the preparation rather than by ABA-1 itself.

FIG. 9.

Distribution of stimulatory activities in size exclusion chromatography fractions of ABF. Shown are the chromatogram with the calibration standards (A), the percent shape change (as described above), and chemotactic (obtained from the fixed and stained cells that migrated through and adhered to the bottom side of the filter) activities in the single fractions (B), and the Ca2+ mobilization (C) from Fura-2-loaded cells. All three activities coincided in fractions 15 to 20. OD, optical density.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that unprimed, purified human neutrophils respond rapidly to nematode body fluid constituents by in vitro chemotaxis, shape change, and Ca2+ mobilization. Furthermore, the most active extract, ABF, very effectively primed neutrophils for superoxide anion production.

The results of the cross-desensitization and receptor antagonist experiments indicated a possible involvement of either CXCR1 or CXCR2 in ABF-dependent neutrophil recruitment. The observed cross-desensitization by high concentrations of fMLP was not caused by homologous desensitization, since the receptor antagonist studies excluded this receptor from being the target of the NCF in ABF. Rather, fMLP is known to act as a strong (heterologous) desensitizer of Ca2+ mobilization induced by IL-8 (3). The desensitization of ABF-induced Ca2+ mobilization by 100 nM fMLP also rules out the involvement of the receptor FPRL1 as the putative receptor for the NCF in our study. FPRL1 has recently been shown to be a receptor for the acute-phase protein serum amyloid A (SAA) (66). Due to the apparently low affinity of FPLR1 for fMLP, only very high concentrations of fMLP (10 μM to 1 mM) are able to desensitize the response to SAA (66). Since our study demonstrated a total desensitization of neutrophils to ABF with 10 or 100 nM fMLP, we think that this result rules out a possible involvement of FPLR1.

Several results led us to assume an involvement of CXCR1 or CXCR2. PAF, when used as the first signal, did not desensitize the Ca2+ mobilization induced by ABF, but when ABF was given first, the response to PAF was partially desensitized. Such a partial (10 to 24%) desensitization of PAF signalling by IL-8 has been described before (3). The effective induction of Ca2+ mobilization by ABF in THP-1 cells is also consistent with a role of CXCR1 or CXCR2, since a receptor for IL-8 has been described in these cells (21, 27). The Ca2+ mobilization in eosinophils is better explained by the activity of the ECF rather than the NCF in ABF, since Petering et al. have recently shown that eosinophils do not express receptors for IL-8 (50). The observation that ABF did not significantly increase superoxide anion production would point to CXCR2 rather than CXCR1 as the putative target receptor, since superoxide anion production induced directly by IL-8 is mediated by CXCR1 but not CXCR2 (32). In this context, the strong effect of ABF is consistent with the known effective priming of neutrophils pretreated with IL-8 (14). Nevertheless, although all our initial results indicated a possible involvement of CXCR2 (or CXCR1), the experiments with the transfected cell lines led us to reject this hypothesis. The strong cross-desensitization between IL-8 and ABF and the weaker (but consistent) desensitization of the neutrophil response to NAP-2, however, suggest that A. suum may directly affect neutrophils via a receptor that interacts with both IL-8 receptors but not with the receptors for fMLP, FPRL1, LTB4, or C5a and only weakly with the receptor for PAF. Thus, our results raise the interesting possibility that human neutrophils may express a receptor which may enable the immune system to detect, target, and ultimately destroy tissue-migrating helminth larvae. Along these lines, the observed priming for superoxide production by parasitic products such as those contained in ABF may serve to enhance the immune response to the intruding parasite or alternatively support scavenger-like functions such as the removal of damaged or dead parasites. Future work will aim to test whether secreted products can activate neutrophils by the same mechanism, or if the reaction is dependent upon body fluid components released only by dead or dying organisms.

What is the biological significance of neutrophil attraction by parasitic products? It is widely accepted that neutrophils are of paramount importance as a first line of defense against bacteria. This is demonstrated by the hereditary disease chronic granulomatous disease (60), in which a defect in the leukocyte oxidase results in a severe deficiency in immunity to several, especially catalase-positive, pathogens (40). Neutrophils are highly responsive to fMLP and related formylated peptides. N-Formylpeptides are bacterial products, and it can therefore be assumed that the main receptor for these products, fMLP-R (7, 8) (or FPR for formylpeptide receptor), plays an important role in antibacterial defense. This view is strongly supported by a recent study by Gao et al. (18), showing that FPR−/− mice display a significantly higher mortality than their wild-type counterparts when challenged with Listeria monocytogenes. It is therefore likely that an analogous recognition mechanism has evolved to mediate responses to multicellular parasites, i.e., helminths. The association between helminth infection and eosinophils has been known for over a century (9), but the role of neutrophils has been less well appreciated. Indeed, the recruitment of eosinophils may itself be indirect and mediated by neutrophils. Neutrophils have the ability to release ECFs upon diverse stimuli, including parasite-derived factors (12, 13, 35, 48), and have been proposed to be mediators of eosinophil recruitment, e.g., in infection with Schistosoma japonicum (46).

A note of caution has to be made regarding the interpretation of our priming experiments. Bacterial endotoxin (LPS) is the classical priming agent for neutrophils (1, 49), and we cannot completely exclude the presence of minute amounts of LPS or other bacterial contaminants in ABF, causing some fraction of its priming effect. Treatment of ABF with polymyxin B-Sepharose did not affect its efficiency as a priming agent. Furthermore, priming of neutrophils by LPS is strongly dependent on the presence of mediators found exclusively in serum or plasma (49) (e.g., LPS-binding protein [69] and septin [75]), which were absent in our assays. We therefore think that putative bacterial contaminants cannot be responsible for the strong priming of neutrophils by ABF.

In summary, we show for the first time how a PDCF contained in ABF induces not only chemotaxis but also strong activation of human neutrophils (calcium mobilization, shape change, and priming of superoxide production) in vitro. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the first report of an NCF activity in T. canis. Our data indicate that these effects are mediated by a receptor which interacts strongly with CXCR1 and weakly with CXCR2 and PAF-R, but is distinct from these receptors and from the receptors for LTB4, C5a, fMLP (FPR), and SAA (FPRL1). The strong and specific interaction with the IL-8 receptor pathway and the PTX sensitivity suggest that the target receptor is a member of the serpentine, heterotrimeric G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Future work will address the molecular identity of this receptor on human neutrophils.

We expect that the techniques used in this study, in combination with the advances in parasite genome sequencing and the rapidly increasing knowledge about the chemokine network, will enable a more thorough understanding of granulocyte recruitment in helminth infections. The understanding of the underlying mechanisms, in addition to suggesting new therapeutic approaches for the treatment of acute parasite-induced pathology, may also impact directly on our understanding of the mechanism of allergic or inflammatory diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Fa 359/1-1), the Wellcome Trust, and the Medical Research Council (G9016491).

We thank Ingrid Schraufstätter (La Jolla Institute for Experimental Medicine, La Jolla, Calif.) for the generous donation of the human IL-8-receptor transfectants. Nontransfected RBL-2H3 were kindly provided by Helmut Haas (Research Center, Borstel, Germany) and Anthony Upton (University of Sheffield, United Kingdom). Human platelet-derived, purified NAP-2 was kindly provided by Ernst Brandt and Andreas Ludwig (Research Center, Borstel). We also thank Seamas C. Donnelly, Ian Dransfield, Ellen Drost, Marie-Hélène Ruchaud-Sparagano (Rayne Laboratory, Edinburgh, United Kingdom) for their kind support and advice and Jill Brown (University of Nottingham, United Kingdom) and Jenny Purcell (University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom) for providing the ABF and the adult A. suum parasites, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aida Y, Pabst M J. Priming of neutrophils by lipopolysaccharide for enhanced release of superoxide: requirement for plasma but not for tumor necrosis factor-α. J Immunol. 1990;145:3017–3025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alabaster V A, Keir R F, Parry M J, de Souza R N. UK-74,505, a novel and selective PAF antagonist, exhibits potent and long lasting activity in vivo. Agent Actions Suppl. 1991;34:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali H, Richardson R M, Haribabu B, Snyderman R. Chemoattractant receptor cross-desensitization. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6027–6030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baggiolini M. Chemokines and leukocyte traffic. Nature. 1998;392:565–568. doi: 10.1038/33340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Human chemokines: an update. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betz S J, Henson P M. Production and release of platelet-activating factor (PAF): dissociation from degranulation and superoxide production in the human neutrophil. J Immunol. 1980;125:2756–2763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulay F, Tardif M, Brouchon L, Vignais P. The human N-formylpeptide receptor: characterization of two cDNA isolates and evidence for a new subfamily of G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochemistry. 1990;29:11123–11133. doi: 10.1021/bi00502a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulay F, Tardif M, Brouchon L, Vignais P. Synthesis and use of a novel N-formyl peptide derivative to isolate a human N-formyl peptide receptor cDNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;168:1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91143-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown T R. Studies on trichinosis, with especial reference to the increase of the eosinophilic cells in the blood and the muscle, the origin of these cells and their diagnostic importance. J Exp Med. 1898;3:315–347. doi: 10.1084/jem.3.3.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole A T, Garlick N M, Galvin A M, Hawkey C J, Robins R A. A flow cytometric method to measure shape change of human neutrophils. Clin Sci (Colch) 1995;89:549–554. doi: 10.1042/cs0890549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culpepper J, Grieve R B, Friedman L, Mika-Grieve M, Frank G R, Dale B. Molecular characterization of a Dirofilaria immitis cDNA encoding a highly immunoreactive antigen. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;54:51–62. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90094-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czarnetzki B M. Eosinophil chemotactic factor release from neutrophils by Nippostrongylus brasiliensis larvae. Nature. 1978;271:553–554. doi: 10.1038/271553a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Czarnetzki B M, Konig W, Lichtenstein L M. Eosinophil chemotactic factor (ECF). I. Release from polymorphonuclear leukocytes by the calcium ionophore A23187. J Immunol. 1976;117:229–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels R H, Finnen M J, Hill M E, Lackie J M. Recombinant human monocyte IL-8 primes NADPH-oxidase and phospholipase A2 activation in human neutrophils. Immunology. 1992;75:157–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eggleton P, Penhallow J, Crawford N. Differences in basal and formyl-Met-Leu-Phe-stimulated F-actin content of human blood neutrophil subpopulations separated by continuous-flow electrophoresis. Biochem Soc Trans. 1991;19:1129–1130. doi: 10.1042/bst0191129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsner J, Hochstetter R, Kimmig D, Kapp A. Human eotaxin represents a potent activator of the respiratory burst of human eosinophils. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1919–1925. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldmeier H, Poggensee G. Human anisakiasis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management. Hospimedica. 1991;9:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao J L, Lee E J, Murphy P M. Impaired antibacterial host defense in mice lacking the N-formylpeptide receptor. J Exp Med. 1999;189:657–662. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gay J C, Beckman J K, Zaboy K A, Lukens J N. Modulation of neutrophil oxidative responses to soluble stimuli by platelet-activating factor. Blood. 1986;67:931–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granger B L, Warwood S J, Hayai N, Hayashi H, Owhashi M. Identification of a neutrophil chemotactic factor from Tritrichomonas foetus as superoxide dismutase. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;89:85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grob P M, David E, Warren T C, De Leon R P, Farina P R, Homon C A. Characterization of a receptor for human monocyte-derived neutrophil chemotactic factor/interleukin-8. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:8311–8316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien R Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haines K A, Kolasinski S L, Cronstein B N, Reibman J, Gold L I, Weissmann G. Chemoattraction of neutrophils by substance P and transforming growth factor-β1 is inadequately explained by current models of lipid remodeling. J Immunol. 1993;151:1491–1499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haston W S, Wilkinson P C. Visual methods for measuring leukocyte locomotion. Methods Enzymol. 1988;162:17–38. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)62060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hebert C A, Vitangcol R V, Baker J B. Scanning mutagenesis of interleukin-8 identifies a cluster of residues required for receptor binding. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18989–18994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horii Y, Owhashi M, Fujita K, Nakanishi H, Ishii A. A comparative study on eosinophil and neutrophil chemotactic activities of various helminth parasites. Parasitol Res. 1988;75:76–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00931196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horuk R, Yansura D G, Reilly D, Spencer S, Bourell J, Henzel W, Rice G, Unemori E. Purification, receptor binding analysis, and biological characterization of human melanoma growth stimulating activity (MGSA): evidence for a novel MGSA receptor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:541–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsiu J G, Gamsey A J, Ives C E, D'Amato N A, Hiller A N. Gastric anisakiasis: report of a case with clinical, endoscopic, and histological findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:1185–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingraham L M, Coates T D, Allen J M, Higgins C P, Baehner R L, Boxer L A. Metabolic, membrane, and functional responses of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes to platelet-activating factor. Blood. 1982;59:1259–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwasaki K, Torisu M. Anisakis and eosinophil. II. Eosinophilic phlegmon experimentally induced in normal rabbits by parasite-derived eosinophil chemotactic factor (ECF-P) Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1982;23:593–605. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(82)90322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones R E, Deardorff T L, Kayes S G. Anisakis simplex: histopathological changes in experimentally infected CBA/J mice. Exp Parasitol. 1990;70:305–313. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(90)90112-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones S A, Wolf M, Qin S, Mackay C R, Baggiolini M. Different functions for the interleukin 8 receptors (IL-8R) of human neutrophil leukocytes: NADPH oxidase and phospholipase D are activated through IL-8R1 but not IL-8R2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6682–6686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy M W, Brass A, McCruden A B, Price N C, Kelly M S, Cooper A. The ABA-1 allergen of the parasitic nematode Ascaris suum: fatty acid and retinoid binding function and structural characterization. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6700–6710. doi: 10.1021/bi00020a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitchen E, Rossi A G, Condliffe A M, Haslett C, Chilvers E R. Demonstration of reversible priming of human neutrophils using platelet-activating factor. Blood. 1996;88:4330–4337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konig W, Czarnetzki B M, Lichtenstein L M. Eosinophil chemotactic factor (ECF). II. Release from human polymorphonuclear leukocytes during phagocytosis. J Immunol. 1976;117:235–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liston T E, Conklyn M J, Houser J, Wilner K D, Johnson A, Apseloff G, Whitacre C, Showell H J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the leukotriene B4 receptor antagonist CP-105,696 in man following single oral administration. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;45:115–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Locati M, Murphy P M. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: biology and clinical relevance in inflammation and AIDS. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:425–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ludwig A, Petersen F, Zahn S, Gotze O, Schroder J M, Flad H-D, Brandt E. The CXC-chemokine neutrophil-activating peptide-2 induces two distinct optima of neutrophil chemotaxis by differential interaction with interleukin-8 receptors CXCR-1 and CXCR-2. Blood. 1997;90:4588–4597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McSharry C, Xia Y, Holland C V, Kennedy M W. Natural immunity to Ascaris lumbricoides associated with immunoglobulin E antibody to ABA-1 allergen and inflammation indicators in children. Infect Immun. 1999;67:484–489. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.484-489.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meischl C, Roos D. The molecular basis of chronic granulomatous disease. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1998;19:417–434. doi: 10.1007/BF00792600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore J, McDermott L, Price N C, Kelly S M, Cooper A, Kennedy M W. Sequence-divergent units of the ABA-1 polyprotein array of the nematode Ascaris suum have similar fatty-acid- and retinol-binding properties but different binding-site environments. Biochem J. 1999;340:337–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy P M. The molecular biology of leukocyte chemoattractant receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:593–633. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niwa A, Asano K, Ito A. Eosinophil chemotactic factors from cysticercoids of Hymenolepis nana. J Helminthol. 1998;72:273–275. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00016552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ottonello L, Tortolina G, Amelotti M, Dallegri F. Soluble Fas ligand is chemotactic for human neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Immunol. 1999;162:3601–3606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Owhashi M, Futaki S, Kitagawa K, Horii Y, Maruyama H, Hayashi H, Nawa Y. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel neutrophil chemotactic factor from a filarial parasite. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:1315–1320. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90048-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Owhashi M, Kirai N, Horii Y. Eosinophil chemotactic factor release from neutrophils induced by stimulation with Schistosoma japonicum eggs. Parasitol Res. 1997;83:42–46. doi: 10.1007/s004360050205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Owhashi M, Horii Y, Ishii A. Eosinophil chemotactic factor in schistosome eggs: a comparative study of eosinophil chemotactic factors in the eggs of Schistosoma japonicum and S. mansoni in vitro. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:359–366. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Owhashi M, Horii Y, Ishii A. Isolation of Schistosoma japonicum egg-derived neutrophil stimulating factor: its role on eosinophil chemotactic factor release from neutrophils. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1985;78:415–420. doi: 10.1159/000233924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pabst M J. Priming of neutrophils. In: Hellewell P G, Williams T J, editors. Immunopharmacology of neutrophils. London, U.K: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 195–221. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petering H, Gotze O, Kimmig D, Smolarski R, Kapp A, Elsner J. The biologic role of interleukin-8: functional analysis and expression of CXCR1 and CXCR2 on human eosinophils. Blood. 1999;93:694–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Potter K A, Leid R W. Isolation and partial characterization of an eosinophil chemotactic factor from metacestodes of Taenia taeniaeformis (ECF-Tt) J Immunol. 1986;136:1712–1717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prociv P, Croese J. Human eosinophilic enteritis caused by dog hookworm Ancylostoma caninum. Lancet. 1990;335:1299–1302. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91186-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reibman J, Meixler S, Lee T C, Gold L I, Cronstein B N, Haines K A, Kolasinski S L, Weissmann G. Transforming growth factor β1, a potent chemoattractant for human neutrophils, bypasses classic signal-transduction pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6805–6809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rollins B J. Chemokines. Blood. 1997;90:909–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rossi A G, MacIntyre D E, Jones C J, McMillan R M. Stimulation of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes by leukotriene B4 and platelet-activating factor: an ultrastructural and pharmacological study. J Leukocyte Biol. 1993;53:117–125. doi: 10.1002/jlb.53.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rossi A G, Hellewell P G. Mechanisms of neutrophil accumulation in tissues. In: Hellewell P G, Williams T J, editors. Immuno-pharmacology of neutrophils. London, U.K: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sakanari J A, McKerrow J H. Anisakiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:278–284. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.3.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Mackay C R. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in T-cell priming and Th1/Th2-mediated responses. Immunol Today. 1998;19:568–574. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schroder J M, Mrowietz U, Morita E, Christophers E. Purification and partial biochemical characterization of a human monocyte-derived, neutrophil-activating peptide that lacks interleukin 1 activity. J Immunol. 1987;139:3474–3483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Segal A W. The NADPH oxidase and chronic granulomatous disease. Mol Med Today. 1996;2:129–135. doi: 10.1016/1357-4310(96)88723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seino K, Iwabuchi K, Kayagaki N, Miyata R, Nagaoka I, Matsuzawa A, Fukao K, Yagita H, Okumura K. Chemotactic activity of soluble Fas ligand against phagocytes. J Immunol. 1998;161:4484–4488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Senior R M, Skogen W F, Griffin G L, Wilner G D. Effects of fibrinogen derivatives upon the inflammatory response: studies with human fibrinopeptide B. J Clin Investig. 1986;77:1014–1019. doi: 10.1172/JCI112353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sklar L A, Oades Z G, Finney D A. Neutrophil degranulation detected by right angle light scattering: spectroscopic methods suitable for simultaneous analyses of degranulation or shape change, elastase release, and cell aggregation. J Immunol. 1984;133:1483–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith W B, Gamble J R, Clark-Lewis I, Vadas M A. Interleukin-8 induces neutrophil transendothelial migration. Immunology. 1991;72:65–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stocks S C, Ruchaud-Sparagano M-H, Kerr M A, Grunert F, Haslett C, Dransfield I. CD66: role in the regulation of neutrophil effector function. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2924–2932. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Su S B, Gong W, Gao J L, Shen W, Murphy P M, Oppenheim J J, Wang J M. A seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1, mediates the chemotactic activity of serum amyloid A for human phagocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:395–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tanaka J, Torisu M. Anisakis and eosinophil. I. Detection of a soluble factor selectively chemotactic for eosinophils in the extract from Anisakis larvae. J Immunol. 1978;120:745–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tanaka J, Baba T, Torisu M. Ascaris and eosinophil. II. Isolation and characterization of eosinophil chemotactic factor and neutrophil chemotactic factor of parasite in Ascaris antigen. J Immunol. 1979;122:302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vosbeck K, Tobias P, Mueller H, Allen R A, Arfors K E, Ulevitch R J, Sklar L A. Priming of polymorphonuclear granulocytes by lipopolysaccharides and its complexes with lipopolysaccharide binding protein and high density lipoprotein. J Leukocyte Biol. 1990;47:97–104. doi: 10.1002/jlb.47.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Walker N I, Croese J, Clouston A D, Parry M, Loukas A, Prociv P. Eosinophilic enteritis in northeastern Australia: pathology, association with Ancylostoma caninum, and implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:328–337. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199503000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ward C, Chilvers E R, Lawson M F, Pryde J G, Fujihara S, Farrow S N, Haslett C, Rossi A G. NF-κB activation is a critical regulator of human granulocyte apoptosis in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4309–4318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wells T N, Power C A, Proudfoot A E. Definition, function and pathophysiological significance of chemokine receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:376–380. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Westlin W F, Kiely J M, Gimbrone M A., Jr Interleukin-8 induces changes in human neutrophil actin conformation and distribution: relationship to inhibition of adhesion to cytokine-activated endothelium. J Leukocyte Biol. 1992;52:43–51. doi: 10.1002/jlb.52.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wilkinson P C. Assays of leukocyte locomotion and chemotaxis. J Immunol Methods. 1998;216:139–153. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wright S D, Ramos R A, Patel M, Miller D S. Septin: a factor in plasma that opsonizes lipopolysaccharide-bearing particles for recognition by CD14 on phagocytes. J Exp Med. 1992;176:719–727. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.3.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]