Abstract

FLT3 mutations are the most common genetic aberrations found in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and associated with poor prognosis. Since the discovery of FLT3 mutations and their prognostic implications, multiple FLT3-targeted molecules have been evaluated. Midostaurin is approved in the U.S. and Europe for newly diagnosed FLT3 mutated AML in combination with standard induction and consolidation chemotherapy based on data from the RATIFY study. Gilteritinib is approved for relapsed or refractory FLT3 mutated AML as monotherapy based on the ADMIRAL study. Although significant progress has been made in the treatment of AML with FLT3-targeting, many challenges remain. Several drug resistance mechanisms have been identified, including clonal selection, stromal protection, FLT3-associated mutations, and off-target mutations. The benefit of FLT3 inhibitor maintenance therapy, either post-chemotherapy or post-transplant, remains controversial, although several studies are ongoing.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia, FLT3, midostaurin, gilteritinib, crenolanib, quizartinib

1. Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a complex malignancy with an array of possible cytogenetic or chromosomal aberrations. The most frequently identified mutation is FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) [1]. About 25% of adult patients with AML will have FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) and 10% will have FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain (FLT3-TKD) point mutations or deletions [2]. Patients with FLT3-mutated AML have a poor prognosis compared to those with wild-type (WT) FLT3. Although patients with FLT3-mutated and WT-FLT3 AML achieve similar response rates to traditional chemotherapy, FLT3-mutated AML patients are more likely to relapse, even after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) [3, 4].

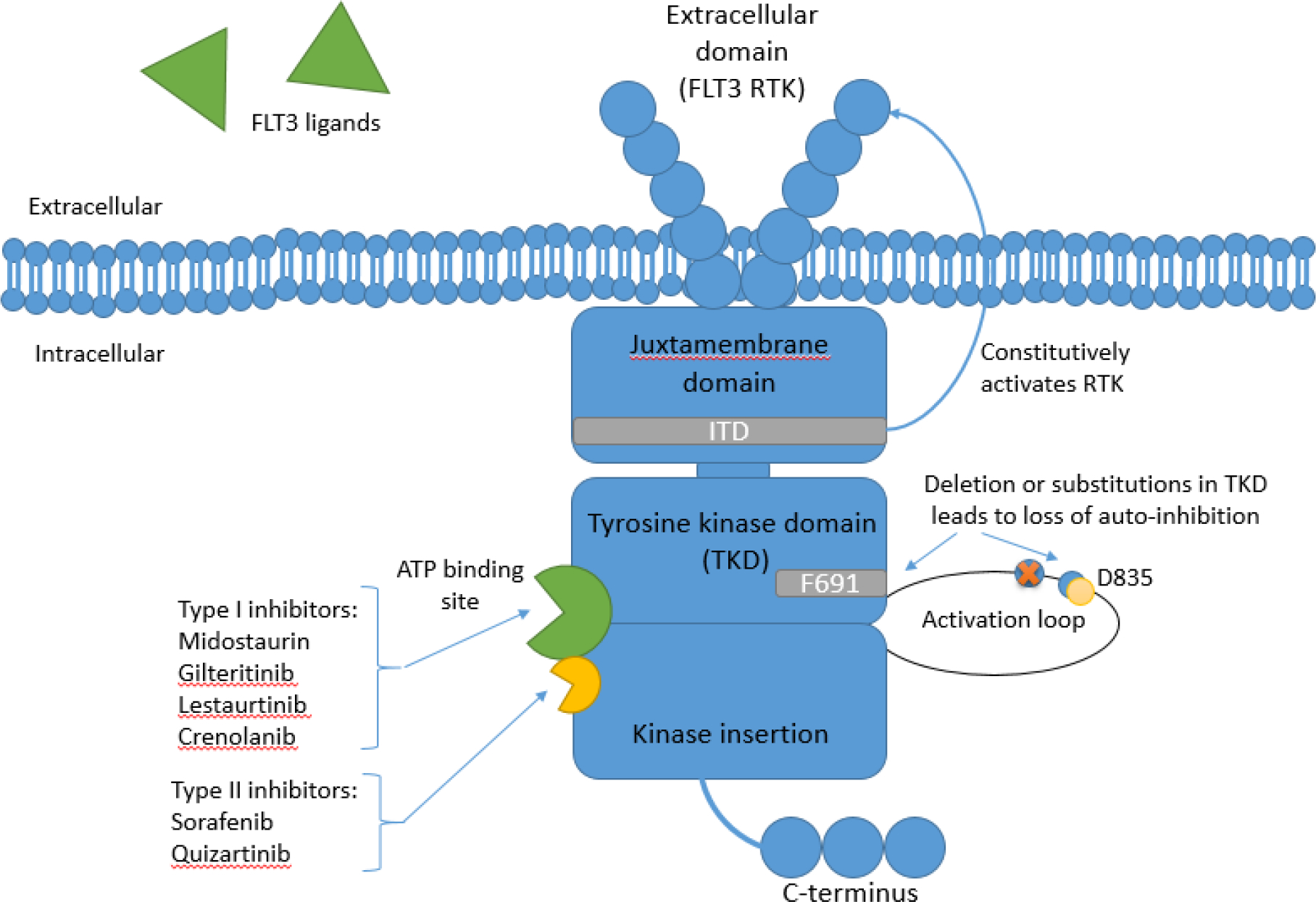

The FLT3 gene on chromosome 13q12 transcribes the FLT3 transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK). FLT3 is expressed on lineage-restricted myeloid and lymphoid progenitor cells and is activated by FLT3 ligand (FL). FLT3 comprises of five domains as seen in figure 1: extracellular, juxtamembrane, tyrosine kinase (TK), kinase insertion, and a C-terminal intracellular domain [2]. It is embedded in several signaling pathways responsible for the life cycle of a cell from differentiation to apoptosis. FL is found in a membrane-bound or in soluble form, produced by bone marrow stroma cells [5]. Normally, after FL binds to FLT3 extracellular domain, the RTK is dimerized and subsequently phosphorylated, becoming activated. This further activates downstream signaling cascades such as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and rat sarcoma (RAS) signal-transduction cascades, leading to hematopoietic cell maturation and proliferation [6]. Soluble FL concentration is usually very low but can increase exponentially in response to aplasia, thus activating FLT3 only when necessary via negative-feedback [7].

Figure 1.

the FLT3 tyrosine kinase comprimses of five domains: extracellular receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), juxtamembrane domain, tyrosine kinase domain (TKD), kinase insertion domain, and a C-terminus intracellular domain. Internal tandum duplication (ITD) mutation is located in the juxtamembrane domain and causes a gain-of-function of the RTK. Deletions or mutations in the TKD results in a loss of auto-inhibition. The most common TKD mutation involving residue D835 is located in the activation loop of the TKD and may lead to lower binding affinity of type II inhibitors. Mutation involving the “gate-keeper” residue F691 is also located within TKD and may lead to resistance to both type I and II inhibitors. Both ITD and TKD mutations lead to constitutive activation of downstream proliferative signaling cascades. Type I inhibitors bind to both the active and inactive conformation of FLT3 at the ATP binding site, while type II inhibitors bind to a site adjacent to the ATP binding site in the inactive conformation only.

AML cells overexpress FLT3 RTKs, and both FLT3 mutations lead to activation of the tyrosine kinase by causing FL-independent dimerization, ultimately resulting in aberrant proliferation of malignant cells. The FLT3-ITD mutation in AML was incidentally discovered in 1996 when researchers were investigating mRNA levels of FLT3 as a potential minimal residual disease (MRD) marker [8]. In 2001, point mutations and deletions at the D835 residue and surrounding codons in the tyrosine kinase domain were discovered [9]. The ITD mutation was later found to constitutively activate the tyrosine kinase function by causing a gain-of-function of the RTK by inhibiting the negative regulatory function of the juxtamembrane domain (figure 1). It is related to increased disease relapse and lower overall survival [10]. FLT3-TKD point mutations cause single amino-acid substitutions in the activation loop, resulting in loss of auto-inhibition (figure 1). The most common is an aspartic acid substitution with tyrosine or histidine at residue 835 [9]. Both ultimately leads to constitutive activation of downstream proliferative signaling cascades [10, 11].

1.1. FLT3 mutations in leukemogenesis

The molecular pathogenesis of AML is complex and distinguishing founder mutations from driver mutations can be difficult, especially in the context of increased genetic testing for other indications [12, 13, 14, 15]. Additionally, AML can be clonally heterogenous and evolves over the disease course under the selective pressure of chemotherapy [14]. For example, DNMT3 mutations have been found in chemotherapy-resistant clones and can lead to clonal expansion and eventually disease relapse [14,16].

The effect and prognostic impact of FLT3 mutations in AML is variable and depends on the allelic ratio and the co-occurrence of other mutations, especially NPM1 [17, 18, 19, 20]. By comparing paired bone marrow samples from the time of diagnosis and relapse, FLT3-ITD mutations and high allelic ratios have been identified as driver mutations and associated with increased leukemic burden and higher white blood cell counts at presentation [20, 21]. Additionally, emergence of FLT3 mutations has been linked to the evolution of myelodysplastic syndrome into secondary AML supporting its role in the regulation of cell proliferation [22]. This suggests that FLT3 mutations (as well as other signaling or NPM1 mutations) are a later event in leukemogenesis, while mutations in epigenetic regulators such as DNMT3A, ASXL1, and TET2 tend to occur as early founder mutations and are found in preleukemic progenitor clones including clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate significance (CHIP) [18, 23, 24].

Whether FLT3 mutations are driver or passenger mutations has remained controversial. The notion of FLT3 as passenger mutations was derived from clinical studies that showed limited efficacy of single-agent therapy with midostaurin and the addition of lestauritinib to chemotherapy in AML patients [25, 26]. Additionally, isolated FLT3-ITD mutations in transgenic mice were insufficient to induce leukemia [27]. Conversely, the role of FLT3 mutations as potential disease drivers is supported by the high incidence of FLT3 mutations in AML patients and the emergence of additional mutations leading to FLT3 inhibitor resistance [15, 28, 29]. Similar conclusions can be drawn from a recent randomized study of post-HSCT maintenance therapy with the multi-kinase inhibitor sorafenib in FLT3-ITD mutated AML patients, which showed that some patients only relapsed after sorafenib discontinuation suggesting that a residual clone was suppressed by sorafenib [30]. However, the therapeutic benefit seen with multikinase inhibitors such as sorafenib or midostaurin could suggest that subclones with other driver mutations are inhibited as well. Serial assessment of the specific FLT3 mutations along the disease course and a better understanding of resistance mechanisms and the activation of alternative signalling pathways will be of great interest and is discussed in greater detail in subsequent parts of this manuscript.

1.2. Prognostic and clinical impact of FLT3 mutations

About 25% of all adult patients with AML will have FLT3-ITD but can be seen in more than 30% of patients who are 55 and older [2]. FLT3 mutations can be found co-existing with other mutations such as PML-RARA, RUNX1, NPM1, and DNMT3A. While FLT3 mutations allow uncontrolled proliferation, these other mutations may impair differentiation or self-renewal [2, 31, 32]. Thus, concomitant mutations may influence the prognostic impact of FLT3 mutations.

The European LeukemiaNet (ELN) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) both use FLT3-ITD allelic burden as a factor for risk stratification and prognosis. Patients with mutated NPM1 and a low allele ratio of less than 0.5 is considered favorable. Nevertheless, the role of transplant is controversial in these patients, with one study showing improved outcomes in patients with very low allelic burden [33]. On the other hand, those with a high allele ratio of 0.5 or greater and NPM1 mutation are categorized as intermediate risk; and those with wild-type NPM1 and FLT3-ITD are categorized as poor risk [19, 34]. It is important to note that there is no consensus on the FLT3-ITD allele ratio threshold, and studies have conflicting results on the impact of the allele ratio on response rate, relapse, and survival [35, 36, 37, 38, 39]. Furthermore, inter-assay variability exists, and some laboratories may not readily report the allele ratio. If unavailable, the presence of FLT3-ITD mutation is automatically considered high risk, unless co-existing with NPM1 mutation, of which is considered intermediate risk. FLT3-TKD does not seem to confer the same prognostic effects as FLT3-ITD mutation [40].

Many studies have shown that FLT3-ITD is an independent prognostic marker associated with high leukemic burden and leukocytosis, poor overall survival (OS), and early relapse [8, 9, 21, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45]. One meta-analysis of four studies including 1160 patients showed that FLT3-mutated AML had worse disease-free survival (DFS) and OS compared to WT-FLT3. TKD was comparable to ITD in DFS, but better in OS [46].

1.3. Targeting FLT3 in AML

Newly diagnosed AML is generally polyclonal with any percent of the malignant cells harboring one or both of the FLT3 mutations. It is theorized that relapsed or refractory (R/R) FLT3-mutated AML may become oligoclonal due to the selective exposure of these cells to FL. After chemotherapy, serum FL level can increase by two to three-log folds in response to aplasia. [42]. This pool of FL may feed the residual FLT3-mutated AML cells after chemotherapy, helping them survive. After repeated exposure to chemotherapy, selective exposure of FLT3-mutated blasts to FL may yield a FL-dependent population at relapse with a higher FLT3 allelic burden compared to initial diagnosis or found to have new FLT3 mutations [47]. Therefore, first generation FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) with some off-target activity are theorized to be more efficacious in newly diagnosed patients, and the more targeted second generation FLT3 inhibitors are theorized to be more efficacious in the R/R setting [48].

Most FLT3 inhibitors are highly protein bound and achieving effective plasma concentration is important for clinical efficacy. Therefore, the plasma inhibitory activity (PIA) assay was developed to evaluate the efficacy of these drugs. The PIA assay cultures FLT3-mutated cells in plasma from patients administered the drug. Instead of traditional serum drug concentrations, phosphorylation status of FLT3-mutated cells is evaluated for efficacy [49]. Using the PIA assay, the first-generation FLT3 inhibitors have generally failed to show adequate suppression of phosphorylation at targeted blood concentrations as monotherapy [2]. Thus, some first-generation FLT3 inhibitors were further studied in combination regimens, and second-generation FLT3 inhibitors were developed with more FLT3 sensitivity and selectivity.

Currently, two FLT3 inhibitors have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AML indications: midostaurin and gilteritinib. Quizartinib, while still under investigation in the U.S., is also approved in Japan. Others have been studied or are currently under investigation for AML indications, including sorafenib, tandutinib, lestaurtinib, and crenolanib. These drugs differ in kinase selectivity, activity, and potency. In-depth discussion of these drugs are below. Characteristics of these drugs are summarized in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of FLT3 inhibitors

| Drug | Sorafenib | Midostaurin | Tandutinib | Lestaurtinib | Gilteritinib | Quizartinib | Crenolanib |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical name | BAY43-9006 | PKC412 | CT53518, MLN-518 | CEP701 | ASP2215 | AC220 | CP868596 |

| Generation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Class type | II | I | II | I | I | II | I |

| Other targets | RAF, RET, KIT, VEGFR, PDGFR | PKC, KDR, KIT, VEGFR, PDGFR | PDGFR, KIT | TRK, JAK2, PKC, KDR, PDGFR | AXL, LTK, ALK | KIT | PDGFR |

| FLT3 kinase inhibition IC50 | 58 | 6.3 | 220 | 3 | 0.29 | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| Dose | 400 mg BID | 50 mg BID | 500mg BID | 80mg BID | 120 mg QD | 60mg QD | 100 mg TID or 200 mg/m2/d divided in 3 doses |

| Major therapeutic use and approval (if applicable) | Monotherapy for post-transplant maintenance (off-label) | In combination with chemotherapy for ND AML (Approved by FDA and EMA*) | Withdrawn | Withdrawn | Monotherapy for R/R AML (Approved by both FDA and EMA) | Monotherapy for R/R AML (Approved in Japan only) | Under evaluation |

| Major trial supporting therapeutic use | SORMAIN | RATIFY | ADMIRAL | QuANTUM-R | Phase 3 trials ongoing | ||

| Notable toxicities | Fatigue, hypertension, diarrhea, rash, hand-foot-syndrome | Severe cytopenias, N/V | Diarrhea, pancreatitis, peripheral neuropathy, headache | Severe cytopenias, QTc prolongation, nausea | Peripheraledema, differentiation syndrome, nausea |

Midostaurin is approved in combination with standard daunorubicin and cytarabine induction and high-dose cytarabine consolidation chemotherapy by both FDA and EMA. EMA also approved midostaurin as maintenance monotherapy for patients in complete response following induction and consolidation chemotherapy.

AML: acute myeloid leukemia; BID: twice daily; EMA: European Medicines Agency; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; ND: newly diagnosed; N/V: nausea/vomiting; QD: daily; R/R: relapsed or refractory; TID: three times a day

2. First-Generation FLT3 Inhibitors

The first generation FLT3 inhibitors evaluated were any TKIs that exhibited FLT3 inhibition. These included sorafenib, tandutinib, sunitinib, midostaurin, and lestaurtinib. As monotherapy, the results of these agents were largely disappointing with low efficacy and high adverse effects [50, 51, 52, 53, 54]. Therefore, a few were further studied as combination therapies.

2.1. Sorafenib

Sorafenib was initially developed as a Raf1 targeted drug for the MAPK (RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK) pathway. Since then, it was found to inhibit multiple RTKs including FLT3, RET, KIT, VEGFR, and PDGFR by directly blocking auto-phosphorylation. It has been studied in several advanced solid tumors including renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and thyroid carcinoma [55].

FLT3-ITD mutated AML cells showed significant response to sorafenib in in vitro and ex vivo studies [56, 57, 58]. Phase 1 study of 50 patients with R/R AML, including 28 with FLT3-ITD and 6 with both ITD and TKD, were given sorafenib monotherapy. Of those with FLT3-ITD mutation, complete response and complete response with incomplete hematologic recovery (CR/CRi) were achieved in five patients. An additional 17 patients showed significant reduction in bone marrow or peripheral blood blasts. However, duration of response was transient [50]. Therefore, although sorafenib has shown single-agent activity in FLT3-ITD mutated AML, further studies of sorafenib are as combination therapy with other agents [59, 60, 61, 62, 63].

Sorafenib was added to standard therapy in the SORAML phase 2 study in patients 60 years or younger with newly diagnosed AML. 134 patients, including 23 (17%) patients with FLT3-ITD, were randomized to be given chemotherapy plus sorafenib, compared to 133 patients without sorafenib. Five-year event-free survival (EFS; 41% versus 27%; p=0.011) and relapse-free-survival (RFS; 53 versus 36%; p=0.035) were improved with sorafenib versus placebo; but 5-year OS was similar (61 versus 53%; p=0.282) [64]. Another phase 2 single-arm study of 61 newly diagnosed AML patients, including 17 with FLT3-ITD mutation, were given sorafenib with chemotherapy. Results showed no statistically significant differences in response rate, DFS, or OS in patients with or without FLT3-ITD [60]. Grade 3 or 4 events more commonly seen with sorafenib included fever, diarrhea, bleeding, cardiac events, hand-foot-syndrome, and rash [62]. Most recently, another phase 2 study (ALLG AMLM16) of sorafenib in combination with intensive chemotherapy in newly diagnosed FLT3-ITD mutated AML also did not show a survival benefit. EFS was not improved with the addition of sorafenib. OS seems to be improved with sorafenib in those with higher FLT3-ITD allelic ratio or receiving transplant in first CR, but study was not powered to detect a statistical significance [65].

Sorafenib has also been studied in combination with hypomethylating agents in patients with FLT3-ITD mutations. Phase 2 studies of sorafenib with azacitidine in FLT3-mutated AML have been conducted in both R/R [59] and newly diagnosed disease [63]. These studies show promising efficacy and safety profiles but will need phase 3 trials to further confirm benefit. Similarly, phase 1/2 study of the combination of sorafenib, vorinostat, and bortezomib in FLT3-ITD mutated AML patient showed promising results but need further confirmatory studies [66]. A phase 3 study (NCT01371981) is evaluating the combination of sorafenib with bortezomib and chemotherapy versus sorafenib plus chemotherapy in newly diagnosed AML patients with FLT3-ITD mutations who are younger than 29 years. This study is closed to accrual with results pending.

2.2. Midostaurin

Midostaurin (N-benzoyl-staurosporine) is a synthetic indolocarbazole derived from Streptomyces staurosporeus bacterium and was originally developed to improve the therapeutic efficacy of staurosporine, a pan-kinase inhibitor, as a protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor [67, 68, 69]. Later, it was found to have activity against multiple tyrosine kinase receptors including PKC-α, FLT3, c-KIT, VEGFR, and PDGFR [67, 70, 71].

Midostaurin has been investigated in several disease states due to its multi-kinase inhibition. As a PKC inhibitor, midostaurin failed to demonstrate efficacy in early phase trials as monotherapy in low-grade lymphoproliferative disorders and metastatic melanoma [72, 73], and as combination therapy in various solid cancers [74, 75]. Similarly, its activity as a VEGFR inhibitor in preclinical studies was not translated into therapeutic efficacy, and further development was halted due to toxicities [76, 77, 78, 79]. However, in vitro and mouse models of midostaurin and its metabolites showed activity against FLT3-mutated cell lines [80, 81]. Additional in vitro studies showed a synergistic effect when midostaurin was used in combination with other anti-leukemic agents (cytarabine, anthracyclines, etoposide, cyclophosphamide and vincristine) and produced a significantly improved cytotoxic effect on FLT3-mutated leukemic cell lines [82]. It was also found to be more potent in FLT3-mutated cells compared to wild type, by inducing G1 arrest leading to apoptosis in FLT3-mutated AML, compared to cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase in FLT3-WT AML [83]. Therefore, midostaurin was further studied mainly as a FLT3 inhibitor.

Midostaurin was initially studied in R/R FLT3-mutated AML or high-grade myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). A phase 2 trial of midostaurin monotherapy in 20 patients showed decreases in peripheral and bone marrow blast counts, although no CR was observed [84]. A subsequent larger phase 2B trial of 95 patients with R/R FLT3-mutated AML and MDS showed similar results with blast reduction but no CR [51]. The lack of complete or durable response with midostaurin monotherapy led to subsequent combination studies with midostaurin plus cytarabine and anthracyclines [26, 85, 86].

RATIFY was an international, placebo controlled randomized phase 3 trial that enrolled 717 adult patients with newly diagnosed FLT3-mutated AML. Patients were randomized to receive midostaurin or placebo with 7+3 induction (daunorubicin and cytarabine), followed by consolidation with HDAC (high dose cytarabine) for up to 4 cycles, followed by maintenance with midostaurin monotherapy for 12 months. The addition of midostaurin significantly improved median OS (74.7 vs 25.6 months, P=0.009) and EFS (8.2 months vs 3.0 months, P=0.002) compared to placebo. Even though protocol specified complete remission (CR) rate (within 60 days) was not significantly different compared to placebo (58.9% vs 53.5%, P=0.15), expanded CR (during treatment and 30 days after treatment discontinuation) rate was significantly higher in midostaurin arm (68% vs 61%, P=0.04). Overall, midostaurin was well tolerated with no significant differences in most hematologic and gastrointestinal side effects. More patients in the midostaurin arm had grade 3 or higher anemia and rash [85].

Almost 40% of patients in RATIFY did not achieve protocol specified CR and 50% patients who were in CR relapsed. Schmalbrock and colleagues evaluated clonal evolution of FLT3-ITD positive AML to study resistance mechanism [87]. A total of 54 patients with FLT3-ITD AML from the RATIFY and AMLSG 16–10 trial who received treatment with midostaurin and had either refractory disease or had relapsed were included in the study. During disease progression and in refractory patients almost 50% patients were FLT3-ITD negative but developed mutations in other signaling pathways such as MAPK. In patients who were FLT3-ITD positive, 11 patients had resistant ITD clones and 32% patients had no FLT3-ITD mutations. In these patient population failure in treatment is thought to be due to either having inadequate levels of midostaurin or resistance mechanism that bypassed FLT3 inhibition.

To note, the RATIFY study had significantly more patients with FLT3-TKD (23%) compared to the general population. Post-hoc analysis of the RATIFY trial in patient with FLT3-TKD treated with midostaurin showed significantly improved EFS, trend towards improved DFS, and a similar OS. Furthermore, patients with NPM1 mutation or core binding factor (CBF) rearrangements in addition to FLT3-TKD showed a significantly better OS compared to those with WT-NPM1 or CBF negative FLT3-TKD AML [88].

Midostaurin has been studied in combination with hypomethylating agents in several phase 1 or 2 studies in untreated patients with AML [89, 90, 91]. However, the combination is not well tolerated, and overall efficacy seems comparable to hypomethylating agent alone.

2.3. Lestaurtinib and Tandutinib

Lestaurtinib and tandutinib are both oral first-generation multi-kinase inhibitors including FLT3 [92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99]. Both have been historically studied in patients with FLT3-mutated AML. Due to negative studies in phase 2 or phase 3 trials, their development in AML weas eventually discontinued [52, 53, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106]. Trial data of lestaurtinib and tandutinib are summarized in the supplementary appendix.

3. Second Generation FLT3 Inhibitors

First-generation FLT3 inhibitors were impeded by off-target effects, poor tolerability, lack of clinical benefit as monotherapy, suboptimal potency, and/or resistance mechanisms [45, 107]. These various roadblocks experienced with first-generation TKIs were instrumental in steering the clinical development of second-generation FLT3-targeted drugs. Second-generation FLT3 inhibitors, including gilteritinib, quizartinib, and crenolanib, were developed to target FLT3 specifically, and thus are more selective with less-off-target toxicity and higher potency [20].

3.1. Gilteritinib

Gilteritinib is an orally administered small molecule inhibitor of several tyrosine kinases, including FLT3, AXL, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). It is a pyrazine carboxamide scaffold drug structure that effectively inhibits FLT3, AXL, and ALK wild type and mutated cells [44, 108]. It is the second FDA approved FLT3 inhibitor, indicated as monotherapy for the treatment of R/R FLT3-mutated AML. Gilteritinib has a category 1 recommendation in the NCCN guidelines for the above indication [34].

In vivo studies showed that gilteritinib is present in excess in tumor cells of interest following oral administration [44]. In preclinical studies, gilteritinib demonstrated highly selective inhibitory activity against cells with FLT3-ITD and TKD mutations (specifically FLT3-D835Y and FLT3-ITD-D835Y point mutations) and weaker activity against c-KIT. Preclinical data also demonstrated highly selective inhibition of AXL, which has a role in activating FLT3 and contributes to FLT3 inhibitor resistance [44, 109]. In both cellular and mouse models, gilteritinib decreased FLT3 phosphorylation levels along with its downstream targets supporting single-agent anti-leukemic activity [44, 45].

The phase 3 ADMIRAL trial included 371 patients with R/R FLT3-mutated AML treated with gilteritinib compared to salvage chemotherapy. Patients were randomized 2:1 with 246 patients treated with gilteritinib 120 mg by mouth daily and 109 patients treated with salvage chemotherapy. Median OS was significantly improved in the gilteritinib arm (9.3 vs 5.6 months; Hazard Ratio (HR) for death: 0.64; p<0.001). Patients treated with gilteritinib achieved more CR/CRi (34% vs 15.3%) with a median duration of 11 months, and improved EFS (2.8 vs 0.7 months) compared to salvage chemotherapy [45]. Gilteritinib was also shown to be more tolerable than chemotherapy, with less grade 3 or higher and serious adverse effects (SAEs) than those receiving salvage chemotherapy. Most frequent adverse effects (AEs) of grade 3 or higher in the gilteritinib group included febrile neutropenia (45.9%), anemia (40.7%), and thrombocytopenia (22.8%). To note, 88% of patients treated in the ADMIRAL study did not receive prior FLT3 inhibitors raising the question of its efficacy following prior treatment with FLT3 inhibitors [45].

Gilteritinib is also currently studied in combination therapies with other agents in R/R FLT3-mutated AML. Preclinical in vivo studies of gilteritinib or midostaurin in combination with venetoclax showed synergistic effects and potently induced apoptosis [110]. It is being evaluated in combination with venetoclax in a phase 1 study (NCT03625505). Recently, results of the expansion cohort of this phase 1 study in 41 FLT3-mutated patients with R/R AML showed 85.4% composite complete remission (CRc) rate, compared to 52% CRc (using the same response parameters) in the ADMIRAL trial. In those with prior FLT3 TKI exposure, CRc was 82.1% [111]. Gilteritinib is also being explored with venetoclax plus azacitidine in a phase 1/2 study (NCT04140487). Gilteritinib is also being evaluated in combination with atezolizumab (NCT03730012) and CC-90009 (NCT04336982) in exploratory studies.

Results seen in the R/R setting encourages the use of gilteritinib as first-line treatment. The phase 3 LACEWING study (NCT02752035) evaluated gilteritinib in combination with azacitidine versus azacitidine alone in newly diagnosed FLT3-mutated AML patients who are ineligible for intensive induction chemotherapy, stratified by mutation status (FLT3-ITD alone, FLT3-TKD alone, Both FLT3-ITD and TKD). Preliminary data from the safety cohort of gilteritinib in combination with azacitidine demonstrated a CRc of 67% (10/15) and a median duration of remission of 10.4 months in the ten patients with CRc [112]. However, the LACEWING trial failed to meet primary endpoint of OS at planned interim analysis. Further enrollment is current halted, and the trial will likely be terminated. One phase 1 study evaluated gilteritinib in combination with induction and consolidation chemotherapy in newly diagnosed AML (NCT02236013). Results showed the combination to be well tolerated with a 70% mutational clearance rate in FLT3-ITD mutated patients who achieved CRc (16/23) [113]. Based on these phase 1 results, a randomized phase 3 trial (HOVON 156 AML) of gilteritinib versus midostaurin in combination with induction and consolidation treatment for FLT3-mutated AML is currently ongoing (NCT04027309).

Additionally, a phase II trial of 25 patients (12 newly diagnosed, 13 R/R) is investigating triplet combination therapy with decitabine, venetoclax and a FLT3 inhibitor. FLT3 inhibitors include gilteritinib (n=10), sorafenib (n=10), and midostaurin (n=5). The rate of CRc was 92% for newly diagnosed patients and 62% in the R/R population. The study found that the results in the newly diagnosed study population (2-year OS of 80%) was similar to previous reports of sorafenib, quizartinib, and gilteritinib with an ORR of 67–92% and median OS of 8.3–18.6 months. This study concluded that frontline triplet therapy with a FLT3 inhibitor, venetoclax, and decitabine is safe and effective for elder patients with newly diagnosed or R/R FLT3-mutated. Larger studies with a higher sample size would be important to confirm these findings [114].

3.2. Quizartinib

Quizartinib (AC220), a unique and highly selective bis-aryl urea compound, is a second-generation small molecule TKI developed explicitly to target FLT3-mutated AML. It is currently approved in Japan for the treatment of R/R FLT3-ITD mutated AML but is not approved by the FDA.

Quizartinib demonstrated potent and highly selective FLT3 activity in both FLT3-ITD mutated and WT-FLT3 cell lines in cellular assays and xenograft models [115, 116, 117]. The phase 1 dose-escalation study evaluated quizartinib in 76 patients with R/R AML irrespective of FLT3-ITD mutation status. Results showed a higher ORR in patients with FLT3-ITD mutations compared to those with wild type, at 53% versus 14%, respectively. The dose-limiting toxicity was grade 3 QT interval prolongation. This study showed that quizartinib has clinical activity in patients with R/R AML, especially in those with a FLT3-ITD mutation [118]. A subsequent phase 2 trial confirmed the single-agent efficacy of quizartinib in R/R FLT3-ITD mutated AML, with 46–56% of patients with FLT3-ITD achieving CRc compared to 30–36% in FLT3-ITD negative patients [119]. The phase 2 study met its pre-determined efficacy endpoint of cCR at interim analysis and ended early.

Approval in Japan was largely based on the phase 3 randomized trial QuANTUM-R that evaluated quizartinib monotherapy versus standard of care salvage chemotherapy in R/R FLT3-ITD mutated AML. After a median follow-up of 23.5 months, Overall survival was longer for quizartinib than for chemotherapy (6.2 months [95% CI: 5.3–7.2] vs 4.7 months [4.0–5.5]; HR for death: 0.76 [0.58–0.98]; p=0.02). Three times as many patients in the quizartinib arm underwent HSCT than those in the salvage chemotherapy arm, suggesting that quizartinib could be useful as bridging therapy to HSCT [120]. However, as transplant decisions were provider-driven, a benefit could only be hypothesized but not definitely established. Safety profile reported in the phase 3 study is consistent with prior studies. The most common AEs in the quizartinib arm were nausea, QT interval prolongations, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events associated with quizartinib were febrile neutropenia, sepsis, QT prolongation, and nausea [120].

A new drug approval (NDA) for quizartinib in adult patients with R/R FLT3-ITD mutated AML was filed by Daiichi Sankyo in 2019 based on the findings of the phase 3 QuANTUM-R study. In August 2019, a final decision was made in an 8–3 vote by the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) to reject the NDA for quizartinib [121, 122]. The FDA performed a separate efficacy analysis and found OS to be different from what was reported, with median OS of 26.9 weeks in the quizartinib arm compared to 20.4 weeks in the salvage chemotherapy arm (HR=0.77; P=.019). Furthermore, survival benefit was only significant when compared to low-intensity salvage therapy (LDAC) and not compared to high-intensity chemotherapy (MEC, FLAG-Ida, etc) [121, 122, 123]. In the end, the FDA found that although there was an evident benefit with use of quizartinib monotherapy, there were enough disparities in the review to raise concerns over the phase 3 data. As of now, quizartinib is only approved in Japan [124]. The denial of its FDA approval in 2019 necessitates further studies to be conducted in R/R FLT3-ITD mutated AML. The phase 2 Q-HAM study (NCT03989713) will evaluate quizartinib in combination with salvage chemotherapy (mitoxantrone plus HDAC) in R/R FLT3-ITD mutated AML patients. Other trials with quizartinib in R/R AML are summarized in table 2.

Table 2:

Ongoing clinical trials of FLT3 inhibitors

| Drug | NCT | Phase | FLT3 Status | Setting (ND vs R/R) | Treatment | Maintenance? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crenolanib | NCT02400255 | 2 | FLT3-mutated | maintenance | Crenolanib following HSCT | Yes |

| Crenolanib | NCT03250338 | 3 | FLT3-mutated | R/R | Crenolanib vs placebo plus salvage chemotherapy | |

| Crenolanib | NCT03258931 | 3 | FLT3-mutated | ND | Crenolanib vs midostaurin administered following induction chemotherapy and consolidation therapy | Midostaurin vs crenolanib post-HCT; MRD+ disease |

| Gilteritinib | NCT02310321 | 1/2 | FLT3-mutated | ND | Gilteritinib in combination with induction and consolidation chemotherapy | |

| Gilteritinib | NCT02752035/LACEWING | 2/3 | FLT3-mutated | ND | Gilteritinib vs azacitidine vs gilteritinib/azacitidine combination | |

| Gilteritinib | NCT02927262 | 3 | ITD only | maintenance | Gilteritinib vs placebo for up to 2 years following induction and consolidation chemotherapy | Yes |

| Gilteritinib | NCT02997202/BMT CTN 1506 | 3 | ITD only | maintenance | Gilteritinib vs placebo following HSCT | Yes |

| Gilteritinib | NCT03182244 | 3 | FLT3-mutated | R/R | Gilteritinib vs salvage chemotherapy | |

| Gilteritinib | NCT03625505 | 1 | Regardless | R/R | Gilteritinib plus venetoclax | |

| Gilteritinib | NCT03730012 | 1/2 | FLT3-mutated | R/R | Gilteritnib plus atezolizumab | |

| Gilteritinib | NCT03836209 | 2 | FLT3-mutated | ND | Gilteritinib vs midostaurin in combination with induction and consolidation chemotherapy | |

| Gilteritinib | NCT04027309/HOVON156 | 3 | FLT3-mutated | ND | Gilteritinib vs midostaurin in combination with induction and consolidation chemotherapy, plus maintenance | Yes |

| Gilteritinib | NCT04140487 | 1/2 | FLT3-mutated | ND or R/R | Gilteritinb in combination with azacitidine and venetoclax | |

| Gilteritinib | NCT04293562 | 3 | Regardless | ND | Standard therapy including gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) compared to CPX-351 with GO, and the addition of Gilteritinib for patients with FLT3 mutations | |

| Midostaurin | NCT00819546 | 1 | Regardless | R/R | Midostaurin plus mtor inhibitor (Everolimus) | |

| Midostaurin | NCT02078609 | 1 | Regardless | R/R | Midostaurin plus Pim kinase inhibitor (LGH447) | |

| Midostaurin | NCT03512197 | 3 | Wild-typeonly | ND | Midostaurin vs placebo in combination with induction and consolidation chemotherapy | |

| Midostaurin | NCT03900949 | 1 | FLT3-mutated | ND | Midostaurin in combination with induction chemotherapy plus gemtuzumab ozogamicin | |

| Midostaurin | NCT04097470/HO-155 | 2 | Regardless | ND | Midostaurin plus decitabine vs decitabine alone | |

| Midostaurin | NCT04385290/MOSAIC | 1/2 | FLT3-mutated | ND | Midostsaurin in combination with gemtuzumab ozogamicin | |

| Midostaurin | NCT04496999 | 1 | FLT3-mutated | R/R | Midostaurin plus HDM2 inhibitor (HDM201) | |

| Quizartinib | NCT01892371 | 1/2 | Regardless | NDorR/R | Quizartinib plus azacitidine or cytarabine | |

| Quizartinib | NCT02668653/QuANTUM-First | 3 | ITD only | ND | Quizartinib vs Placebo in combination with induction and consolidation chemotherapy, plus maintenance post-chemotherapy and post-HSCT | Yes |

| Quizartinib | NCT03135054 | 2 | ITD only | ND | Quizartinib in combination with omacetaxine mepesuccinate | |

| Quizartinib | NCT03552029 | 1 | ITD only | ND | Quizartinib plus MDM2 inhibitor (Milademetan) | |

| Quizartinib | NCT03661307 | 1/2 | ITD only or ITD/TKD comutations | ND or R/R | Quizartinib plus decitabine and venetoclax | |

| Quizartinib | NCT03723681 | 1 | Regardless | ND | Quizartinib in combination with induction and consolidation chemotherapy | |

| Quizartinib | NCT03735875 | 1b/2 | ITD only | R/R | Quizartinib plus venetoclax | |

| Quizartinib | NCT03989713/Q-HAM | 2 | ITD only | R/R | Quizartinib in combination with salvage chemotherapy | |

| Quizartinib | NCT04047641 | 2 | Regardless | ND, R/R | Quizartinib in combination with cladribine, idarubicin, and cytarabine | |

| Quizartinib | NCT04107727 | 2 | Wild-typeonly | ND | Quizartinib vs placebo in combination with induction and consolidation chemotherapy | |

| Quizartinib | NCT04112589 | 1/2 | Regardless | R/R | Quizartinib in combination with FLAG-Ida (fludarabine, cytarabine, idarubicin, filgrastim) | |

| Quizartinib | NCT04128748 | 1/2 | Regardless | ND, R/R | Quizaritnib in combination with CPX-351 | |

| Quizartinib | NCT04209725 | 2 | ITD only | R/R | Quizartinib in combination with CPX-351 | |

| Quizartinib | NCT04676243/Q-SOC | 3 | ITD only | ND | Quizartinib in combination with daunorubicin/cytarabine or idarubicin/cytarabine vs physician’s choice | |

| Quizartinib | NCT04687761 | 1/2 | ITD only | ND | Quizartinib vs low-dose cytarabine or azacitidine plus venetoclax | |

| Sorafenib | NCT01578109 | pilot | ITD only | maintenance | Sorafenib as peri-transplant remission maintenance | Yes |

| Sorafenib | NCT01861314 | 1 | Regardless | ND or R/R | Sorafenib plus bortezomib, then decitabine | |

| Sorafenib | NCT02728050 | 1/2 | Regardless | ND | Sorafenib plus G-CLAM (filgrastim, Cladribine, Cytarabine, and Mitoxantrone) | |

| Sorafenib | NCT03132454 | 1 | Regardless | ND | Sorafenib plus CDK 4/6 inhibitor (Palbociclib) | |

| Sorafenib | NCT04752527 | 2 | ITD only | ND | Sorafenib plus venetoclax and azacitidine |

HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplant; ND: newly diagnosed; R/R: relapsed or refractory

In newly diagnosed FLT3-ITD mutated AML, a phase 1 study evaluated quizartinib in combination with cytarabine and daunorubicin (7+3) standard of care. Results showed promising efficacy and safety data [125], which prompted subsequent ongoing phase 2 trial (NCT04107727) and the phase 3 QuANTUM-First study (NCT02668653) to further evaluate this combination. The QuANTUM-First trial will also include up to three years of post-chemotherapy placebo-controlled quizartinib monotherapy therapy to evaluate its role as maintenance treatment. Another phase 3 trial (NCT04676243) will evaluate quizartinib with chemotherapy compared to physician’s choice. One phase 1/2 trial evaluated the combination of quizartinib with low dose cytarabine (LDAC) or azacitidine in various untreated and R/R myeloid diseases, including AML, MDS, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML). A FLT3-ITD mutation was required for the phase 2 portion of this study. Interim analysis showed an ORR of 67% (77% in the azacitidine cohort and 23% in the LDAC cohort) and a median survival of 14.8 months (not reached in azacitidine cohort and 7.5 months in LDAC cohort). Based on these results, it was concluded that quizartinib was active among patients with FLT3-ITD mutated AML/MDS/CMML without D835 mutation [126]. A phase 3 study would be needed to confirm these findings. Several phase 1 or 2 combination studies in newly diagnosed FLT3-ITD mutated AML patients with quizartinib are also ongoing, as summarized in table 2.

One area of ongoing investigation is doublet or triplet therapy with quizartinib and venetoclax in FLT3-mutated patients. The safety of decitabine and quizartinib doublet therapy was evaluated in a phase 1b/2 study in newly diagnosed or R/R AML patients (initially regardless of FLT3 status). After a median follow-up of 12 months, the median PFS in the six R/R AML patients was 5.7 months. Protocol was amended to triplet therapy with venetoclax. In the triplet group receiving decitabine, venetoclax, and quizartinib, CRc occurred in 9/10 patients and in 8/9 patients with R/R FLT3-ITD. Median OS was not reached, with the 6-month OS at 86%. The most common grade 3/4 toxicity included infection and neutropenic fever. The investigators concluded that the triplet combination was effective in R/R FLT3-ITD mutated AML [127].

3.3. Crenolanib

Crenolanib besylate (CP-868,596) is an investigational benzimidazole molecule originally developed as a platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) inhibitor, but was also found to inhibits FLT3 [128, 129]. Beyond its activity in epithelial and mesenchymal cell malignancies (activity in gastrointestinal stromal tumors), crenolanib also has antineoplastic activity in FLT3-mutated AML, with a potent and selective inhibition of both wild type and mutant forms of FLT3 including both ITD and D835 [129, 130].

In its earliest drug development phase, crenolanib was tested against a panel of D835 mutant leukemic cell lines. A superior cytotoxic effect was noted in comparison to other TKIs with FLT3 inhibiting potential, such as quizartinib and sorafenib. Compared to quizartinib, crenolanib had less inhibition of c-KIT. Preclinical studies also demonstrated less impact on bone marrow cell colony growth, potentially leading to less myelosuppression than quizartinib. Preclinical data and ongoing studies have also shown that adequate levels of crenolanib can be attained to effectively inhibit FLT3-ITD and certain mutations implicated in drug resistance, such as FLT3-D835 [131, 132].

Results from a phase 1 study provided insight regarding safety, maximum-tolerated dose, and pharmacokinetics of crenolanib. The most common dose-limiting toxicities included hematuria, increased ALT or γ-glutamyltransferase, nausea/vomiting, and insomnia. [130].

The safety and efficacy of crenolanib in R/R AML has been evaluated in two phase 2 trials. In one single-center phase 2 parallel group trial, crenolanib was given to R/R AML patients with FLT3-ITD or FLT3-TKD. Patients were either FLT3 TKI treatment naïve (cohort A) or had progressed on prior FLT3-targetted treatment (cohort B). An ORR of 47%, including 12% CR/CRi, was reported after a median follow-up of 14 week. FLT3 inhibitor-naïve patients had better outcomes than in those who progressed on prior FLT3-targetted treatment, suggesting that direct target FLT3 inhibition might play a role in crenolanib efficacy. Most patients discontinued crenolanib due to disease progression (66%) and lack of response (16%). The most common grade 3 or higher AEs reported were GI-related, mostly abdominal pain and nausea. Study concluded that crenolanib was safe and effective in heavily pre-treated R/R FLT3-mutated AML and hypothesized that combination chemotherapy could provide greater efficacy in both treatment naïve and previous FLT3-inhibitor treated patients [133]. The other phase 2 study evaluated crenolanib in R/R FLT3-mutated AML in three cohorts, divided between patients without any prior FLT3 TKI exposure (cohort A), those who have received prior FLT3 TKIs (cohort B), and those who acquired FLT3-mutated AML secondary to MDS, myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera, or systemic mastocytosis (cohort C). Those without prior FLT3 TKI exposure had better OS of 7–8 months compared to those with previous FLT3 TKI treatment of 3 months. Patients in cohort C showed a transient benefit from crenolanib with an OS of 2 months. The most common adverse effects reported were transaminitis, edema, and nausea/vomiting. Two patients discontinued crenolanib due to intolerable side effects. This study concluded that crenolanib demonstrated viable safety and efficacy as a single agent in R/R AML [134]. A phase 3 trial of crenolanib versus placebo in combination with salvage chemotherapy in R/R FLT3-mutated AML patients is currently ongoing (NCT03250338).

Crenolanib also demonstrated promising activity in combination therapy in newly diagnosed FLT3-mutated AML patients in a phase 2 trial. A CR of 85% was observed and 70% of patients remained disease free after a median follow up of 29 months [135]. Similarly, another phase 2 trial of crenolanib plus chemotherapy in older adults age 61–75 years also showed a high CR of 86% [136]. A phase 3 randomized study is currently recruiting patients to compare crenolanib versus midostaurin after induction and consolidation chemotherapy in newly diagnosed FLT3-mutated AML patients (NCT03258931). The two ongoing phase 3 studies will provide more insight into the role of crenolanib for the treatment of FLT3-mutated AML.

4. FLT3 Inhibitor Resistance

Treating FLT3-mutated AML with FLT3-targeted TKIs can be challenging due to the development of resistance. Several resistance mechanisms have been identified and can be classified as either primary or secondary. Primary resistance occurs during initial FLT3 TKI exposure under a FL-dependent and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2)-dependent cellular environment. Clonal selection and protection offered by stromal cell and the bone marrow microenvironment allowing alternative signaling pathways may all contribute to primary resistance. Secondary resistance involves acquired resistance that ultimately renders the FLT3 TKIs ineffective. This may occur through secondary mutations directly related to FLT3 or off-target mutations that create alternative signaling pathways [137].

4.1. Clonal Selection

As previously discussed, newly diagnosed AML is likely polyclonal, and may become oligoclonal at relapse. Most FLT3-mutated AML cells may also simultaneously express WT-FLT3. After initial treatment exposure to FLT3 TKIs and chemotherapy, FLT3-mutated clones that are sensitive to FLT3 inhibitors are mostly destroyed, and those with WT-FLT3 may survive with support of FL. This has been shown in both in vivo and in vitro studies, with lessened anti-leukemic effects seen in AML cells that express both mutated and wild-type FLT3 [138, 139]. Furthermore, previously survived subclones may be present in higher populations at relapse compared to initial diagnosis [14]. Additionally, the repeat use of FLT3 inhibitors for the treatment of R/R AML may be less effective depending on the FLT3 status, which is important to reassess as it may change from initial diagnosis. FLT3 mutations may also occur later in leukemogenesis as previously discussed [18, 23]. Therefore, certain more primitive leukemic clones may escape initial treatment with FLT3 inhibitors.

4.2. Stromal Protection

FLT3-mutated cells that are sensitive to FLT3 inhibitors may survive initial treatment under the protection of the bone marrow. Blasts with FLT3-ITD in the peripheral blood can be easily eliminated on contact with FLT3 TKIs, but it is more difficult to eliminate those in the bone marrow. Many FLT3 inhibitors are metabolized by CYP3A4 enzymes. Bone marrow stromal cells have a high concentration of CYP3A4, thus providing chemo-protection to FLT3-ITD mutated AML cells residing in the bone marrow [140]. Early FLT3 inhibitors, such as lestauritinib, could not reach FLT3-mutated blasts in the bone marrow [53, 84, 97]. The bone marrow also may not achieve the concentration of FLT3 inhibitors needed for therapeutic effects. Newer agents, such as quizartinib, are able to reach FLT3-mutated blasts in both the bone marrow and peripheral blood, but still cannot eliminate MRD [141]. Similarly, therapeutic activity of other FLT3 inhibitors including sorafenib and gilteritinib is shown to be affected by stromal cell CYP3A4-mediated mechanisms [142].

Additionally, the bone marrow stroma appears to protect blasts from FLT3 inhibitors through extracellular receptor kinase mediated signaling. The bone marrow has high levels of FL that promotes survival in leukemic blasts with both WT-FLT3 and FLT3-ITD, while reducing sensitivity to FLT3 inhibitors [139, 143]. Growth factors and cytokines within the bone marrow microenvironment may contribute to resistance by activating FLT3-independent pathways for cell survival and proliferation [144]. FGF2 is a growth factor that has been shown to contribute to quizartinib resistance. FGF2 activates fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) expressed on AML cells to promote downstream MAPK signaling independent of FLT3 [145]. In another instance, CXCR4 expressed on AML cells may bind to CXCL12 expressed by osteoblasts in the bone marrow. This leads to the activation of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, which also leads to cell survival and proliferation [137].

4.3. FLT3-associated Mutations

Mutations in the FLT3 TKI receptor binding sites have been identified [146]. FLT3 has an active and inactive conformation, depending on the organization of three amino acid residues in the activation loop (A-loop). As seen in figure 1, type I inhibitors (midostaurin, gilteritinib, crenolanib, lestauritinib) can bind to both the active and inactive conformation at the ATP binding domain. However, type II inhibitors (sorafenib, quizaritinib) bind to a site adjacent to the ATP binding domain and can only bind in the inactive conformation [2]. Resistance to an entire class of inhibitors has been demonstrated as mutations emerge. However, cross resistance to the other class of inhibitors has not been seen [147].

The most common mutation involves residue D835 of the TK domain (FLT3-TKD D835) which leads to lower binding affinity of type II inhibitors [148]. Type II inhibitors have no affinity for FLT3-TKD, and mutations in the TK domain can confer resistance by decreasing the binding affinity of type II inhibitors to the ATP binding site. In FLT3-ITD mutated AML patients who are refractory or relapse after treatment with type II inhibitors such as quizartinib, new FLT3-TKD mutations such as D835, Y842 among others have been reported [29]. Decreased therapeutic effects of quizartinib and sorafenib have been observed in in vitro studies in cells with both FLT3-ITD and TKD mutations [137]. Mutations in the “gate-keeper” residue F691 of the TK domain has also been shown to confer resistance to both type I and II inhibitors [29, 149]. Mutational resistance may also be polyclonal with different frequencies between multiple alleles [137].

4.4. Off-Target Mutations

Resistance also can occur from other pathways replacing FLT3-dependent signaling for blast survival. In a study with 69 patients with FLT3-mutated AML, two thirds progressed on FLT3 inhibitor therapy without any new FLT3 mutations found. This suggests the involvement of unrelated signaling pathways promoting leukemic survival, including those downstream of FLT3 such as RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR [143, 146]. Several pro-survival protein mutations within these pathways have been found to activate downstream signaling pathways independent of FLT3.

In one study of patients who relapsed after gilteritinib, FLT3 mutations were not detected in 12.2% of gilteritinib-resistant patients. Instead, mutations in the RAS/MAPK pathway were present in all of the patients. 24.4% of patients were FLT3-mutated but had additional mutations in the RAS/MAPK pathway. Mutations identified in the RAS/MAPK pathway include NRAS, KRAS, PTPN11, CBL, and BRAF [150]. Additionally, in a small case series, patients who progressed on gilteritinib developed a BCR-ABL1 mutation. Being a targetable mutation, FLT3-inhibitor and BCR–ABL targeted therapy were utilized in combination treatment [151]. In one clonal evolution analysis of relapsed FLT3-ITD mutated patients treated with midostaurin in the RATIFY trial, 46% of patients became FLT3-ITD negative and acquired mutations in signaling pathways such as MAPK [87]. Activation of AXL-1, a RTK, may also activate the RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways, contributing to FLT3 TKI resistance [152, 153]. Upregulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in patients resistant to sorafenib has also been reported [154]. In patients with poor response to crenolanib, mutations in epigenetic regulators and granulocyte transcription factors such as NRAS, STAG2, CEBPA, ASXL1, and IDH2 have been noted in WT-FLT3 AML. In addition, mutations in TET2, IDH1, and TP53 has been identified in FLT3-mutated AML [155]. Compared to type II inhibitors, resistance to type I inhibitors are more associated with off-target mutations. Additional off-target mutations include Pim-1, a proto-oncogene, seen with lestaurtinib and sorafenib, and may contribute to increased anti-apoptotic protein expression [137, 156, 157].

Aside from mutations in bypass pathways, leukemic cells may also over-express P-glycoprotein (P-gp), an efflux pump. P-gp was found to decrease the sensitivity of FLT3-ITD mutated AML cells to FLT3 inhibitors [158].

5. Future Directions

Although long strides have been made towards understanding FLT3 mutations in AML with the advent of several FLT3 inhibitors, many challenges and unanswered questions remain. As previously discussed, many resistance mechanisms have been identified with FLT3 inhibitors but not all are fully elucidated. These resistance patterns render FLT3-targeted molecules ineffective in more ways than one, making them challenging to overcome. Strategies to retain the efficacy of FLT3 inhibitors despite resistance patterns are necessary to advance the use of FLT3 inhibitors. Furthermore, although several studies of FLT3 inhibitors included maintenance therapy, no definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding their role in this setting. In order to optimize the therapeutic potential of FLT3 inhibitor, understanding its use as maintenance therapy will be important.

5.1. Strategies to Overcome Resistance

With the identification of several mechanisms of resistance to FLT3 inhibitors, approaches to address these include the development of new agents and ongoing studies using current agents in combination regimens.

New FLT3 inhibitors are developed to be more specific with higher affinity, regardless of certain mutations [143]. Currently, type I inhibitors can inhibit FLT3-ITD in the presence of TKD while type II inhibitors cannot. But type II inhibitors are more selective compared to type I inhibitors. FF-10101 is a novel FLT3 inhibitor that covalently binds to the kinase at C695. This allows selective and irreversible inhibition of FLT3 in both the active and inactive conformation. FF-10101 is also unaffected by the F691L gate-keeper mutations that renders all other FLT3 inhibitors ineffective. FF-10101 demonstrated potent activity in preclinical studies in quizartinib-resistant AML cells with F691 mutations [159]. A phase 1/2 study is ongoing evaluating FF-10101 in R/R AML (NCT03194685). CG806 is another inhibitor being studied in a phase 1/2 study in R/R AML (NCT04477291) for its activity against wild type and mutated FLT3-ITD and TKD as well as Bruton’s tyrosine kinase [160]. Most recently, LT-171-861, a novel FLT3 inhibitor has been potent in vitro and in vivo activity [161]. Several other highly selective FLT3 inhibitors with activity against D835 and F691 mutations are also in development. These include TTT-3002 [162], G-749 [163], MZH-29 [164], and HM43239. There is currently a phase 1/2 study of HM43239 in R/R AML (NCT03850574). Combination therapy of a FLT3 inhibitor and another agent targeting a different pathway can also lead to blast elimination and prevention of resistance. Dual-inhibitors being evaluated to overcome resistance associated with FLT3 include PIM/FLT3 inhibitor SEL24 [165], MEK/FLT3 inhibitor E6201 [166], AKT/FLT3 inhibitor A674563 [167], and MERTK/FLT3 inhibitor MRX-2843 [168]. Existing FLT3 inhibitors are also being studied in a number of different combinations, as summarized in table 2.

5.2. FLT3 Inhibitors as Maintenance Therapy – Questions Left Unanswered

Several studies of FLT3 inhibitors thus far have included maintenance therapy either post-chemotherapy or post-HSCT, but its use in these settings remains controversial.

5.2.1. Post-chemotherapy Maintenance

Midostaurin was evaluated as maintenance therapy in the RATIFY trial for up to one year post chemotherapy. Post-hoc analysis showed no benefit of midostaurin maintenance, but median duration of maintenance treatment was only three months as 59% of patients underwent HSCT [169, 170]. The AMLSG 16–10 phase 2 trial also gave Midostaurin maintenance for up to one year either after transplant (75 of 97) or after HDAC consolidation (22 of 97). Median duration of maintenance treatment was 10.5 months after HDAC. Sensitivity analysis for EFS censoring for patients proceeding to HSCT seems to show a benefit for Midostaurin. However, this was compared to historic controls [86]. No definitive conclusions can be drawn from either trial regarding midostaurin’s benefit as maintenance therapy after chemotherapy. The phase 3 HOVON 156 AML (NCT04027309) trial comparing midostaurin to gilteritinib will include maintenance therapy of up to two years. However, because this trial is not comparing the FLT3 inhibitors to placebo, it will be difficult to determine the true benefit of post-chemotherapy maintenance. On the other hand, the phase 3 QuANTUM-First (NCT02668653) study will evaluate quizartinib including up to 3 years of post-chemotherapy maintenance compared to placebo. The phase 2 study (NCT02927262) of gilteritinib as maintenance therapy after induction and consolidation therapy will also be compared to placebo. These ongoing studies may offer more insight into the benefit of FLT3 inhibitor maintenance therapy after chemotherapy and solve unanswered questions. Is there a benefit of post-chemotherapy FLT3 maintenance therapy? Can FLT3 inhibitor maintenance therapy replace transplant? What is the patient population to benefit the most from FLT3 inhibitor maintenance therapy and can measurable residual disease (MRD) status play a role in the clinical decision-making? Which FLT3 inhibitor is the best to use as post-chemotherapy maintenance therapy? How long should FLT3 inhibitor maintenance therapy be continued and how would duration be determined?

5.2.2. Post-transplant Maintenance

Sorafenib was found to have graft-versus-leukemia effects, leading to studies in the post-transplant setting for patients with FLT3-ITD mutated AML [30, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177]. Sorafenib was analyzed in one phase 3 study as maintenance therapy in FLT3-ITD mutated AML after allogeneic HSCT. 202 patients were randomized to sorafenib or placebo from day 30 to 180 post-HSCT. After a median follow-up of 21.3 months post-transplant, results showed improved relapse rate of 7% in the sorafenib group versus 24.5% in the control group (p=0.001). Most common grade 3 and 4 adverse events were comparable between the two groups and included infections and acute and/or chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD). Sorafenib had more grade 3 or 4 hematologic toxicities than the placebo group (15 vs 7%), but no treatment-related deaths were reported [175]. In a similar placebo-controlled phase 2 study (SORMAIN), sorafenib was given as maintenance therapy post allogeneic HSCT to 83 FLT3-ITD mutated patients for up to 24 months. After a median follow-up of 41.8 months, results showed improved RFS and OS compared to placebo, especially in those with undetectable MRD pre-HSCT and detectable MRD post-HSCT [30]. To note, the SORMAIN study was terminated early due to low accrual. Although the study was underpowered with only 83 patients out of 200 needed for 80% power, a significant improvement in EFS and OS were nevertheless observed, demonstrating profound efficacy as post-transplant maintenance therapy. Of interest, 4 of 10 RFS (8 relapses, 2 deaths) events in the sorafenib arm occurred after the end of treatment, suggesting that sorafenib is rather suppressing than eliminating a persistent leukemic clone [30, 144]. Nine patients in the sorafenib arm had been treated with midostaurin, and it is uncertain how this may affect the efficacy of sorafenib maintenance. Overall, sorafenib seems to be well tolerated and has shown benefit as post-transplant maintenance therapy.

In the AMLSG 16–10 phase 2 trial, midostaurin maintenance was given to 75 patients after HSCT for a median of 9 months, started at a median of 71 days after transplant. There seemed to be a survival benefit compared to historical controls, but adverse effects were reported more commonly compared to those who received maintenance therapy after HDAC [86]. The phase 2 RADIUS trial evaluated midostaurin maintenance in 60 patients with FLT3-ITD mutations after HSCT. Thirty completed all planned 12 cycles of maintenance therapy. 18-month RFS was improved in the midostaurin group (89 vs 76%), but this difference was not statistically significant [177]. Results of these studies should be interpreted with care, and the benefit of maintenance midostaurin remains inconclusive.

There is also limited evidence of quizartinib as maintenance therapy. One phase 1 dose-escalation study gave quizartinib to 13 FLT3-ITD mutated AML patients as maintenance therapy after allogeneic HSCT. This study showed an acceptable safety profile and evidence of reduced relapse in the post-transplant setting compared to historical cohorts [179]. Further studies would be needed to confirm these findings.

Several ongoing studies are evaluating other FLT3 inhibitors as post-transplant maintenance therapy. One phase 3 study is comparing midostaurin to crenolanib as post-HSCT maintenance therapy (NCT03258931). The phase 3 MORPHO study (BMT CTN 1506) is comparing gilteritinib to standard of care as post-HSCT maintenance therapy (NCT02997202). In contrast to the SORMAIN study, the MORPHO study will include many patients with prior FLT3 inhibitor exposure. These studies may help answer similar questions raised in the post-chemotherapy maintenance setting. In addition, it would be interesting to know if FLT3 inhibitors would be appropriate as bridge therapy to transplant.

5.3. Venetoclax-Based Combination Therapies

With the approval of venetoclax-based combinations for older (>75 years) patients and those unfit for intensive chemotherapy, a new therapeutic option has become available. In subgroup analyses of the VIALE-A trial, patients with FLT3 mutations also experienced a statistically significant higher response rate although no OS benefit [180]. While the statistical power of such subgroup analyses is limited, the role of azacitidine/venetoclax in patients with FLT3 mutations is evolving. Based on preclinical suggesting synergy between FLT3 inhibitors and venetoclax [181], such combination therapies are being increasingly studied. Ongoing trial of triplet therapies of hypomethylating agents with venetoclax and FLT3 inhibitors have demonstrated safety and high response rates [114, 127] but randomized trials with longer follow up are necessary.

6. Conclusion

Significant advancements in treatment have been made since understanding the role of FLT3 mutations in AML. First and second generation FLT3 inhibitors provide treatment options in both the first line and relapse and refractory setting. However, as resistance arises, focus needs to be placed on studying novel mechanisms of treatment to achieve cure. Furthermore, the benefit of FLT3 inhibitors as maintenance therapy in AML remains unknown as we await the results of several ongoing trials.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

FLT3 inhibitors have become major therapeutic integrations in the treatment of FLT3-mutated AML. First generation FLT3 inhibitors have off-target activity and are theorized to be more efficacious in newly diagnosed AML patients with clonally heterogenous disease. While the more targeted second generation FLT3 inhibitors are theorized to be more efficacious in the R/R AML setting with likely monoclonal disease. First generation FLT3 inhibitors are impeded by off-target adverse effects, poor tolerability, lack of clinical benefit as monotherapy, and suboptimal potency. Therefore, second generation FLT3 inhibitors were developed with increased potency and specificity.

Resistance to FLT3 inhibitors may develop via several different mechanisms. These include clonal selection and survival with FLT3 ligand, stromal protection of cells within the bone marrow, FLT3 receptor on-target mutations, and off-target mutations with bypass pathways. Novel FLT3-targeted agents such as FF-10101 has demonstrated promising preclinical efficacy against cells with F691L gate-keeper mutations that renders all other FLT3 inhibitors ineffective. Dual-inhibitors and combination regimens are evaluated for synergistic effects. These include FLT3 with PIM, MEK, AKT, or MERTK inhibition.

The use of FLT3 inhibitors as maintenance therapy in FLT3-mutated patients with AML after transplant is supported by several published studies. The European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation recommends FLT3 inhibitor maintenance therapy after transplant for those with FLT3-ITD mutations, especially those with positive minimal residual disease prior to transplant. Sorafenib is preferred, and maintenance studies of other FLT3 inhibitors as possible alternatives are ongoing. Midostaurin is currently approved in Europe as post chemotherapy maintenance. Additional studies may also reveal key information regarding other FLT3 inhibitors for post-chemotherapy maintenance.

Practice Points

It is important to re-analyze FLT3 mutations for refractory disease or at disease relapse, as the status of FLT3 mutation and the degree of mutational burden (if applicable) may evolve.

Midostaurin is currently approved by the FDA and EMA for newly diagnosed FLT3 mutated AML with cytarabine and anthracycline induction and consolidation. It is also approved by the EMA as maintenance therapy post chemotherapy for those in remission after consolidation. It is not currently approved by the FDA as maintenance therapy.

Gilteritinib is approved as monotherapy for relapsed or refractory patients with FLT3 mutated AML.

Sorafenib is recommended by the EBMT as post-transplant maintenance therapy for those with FLT3 mutated AML, especially those with positive MRD prior to transplant.

Research Agenda

FLT3 as a passenger or a driver mutation remains controversial and further understanding of this would provide a better grasp on the impact of FLT3 inhibitors treatment.

Although several resistance mechanisms to FLT3 inhibitors have been identified, not all are fully elucidated. Further understanding of resistance patterns will provide guidance towards strategies to overcome them.

Sorafenib as post-transplant maintenance is supported by several studies. Trials evaluating other FLT3 inhibitors, including crenolanib, gilteritinib, and quizartinib, as post-transplant and post-chemotherapy maintenance therapy are ongoing.

Acknowledgements

AMZ is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar in Clinical Research and is also supported by a NCI’s Cancer Clinical Investigator Team Leadership Award (CCITLA). This research was partly funded by the Dennis Cooper Hematology Young Investigator Award (AMZ) and was in part supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30 CA016359. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Eli Lilly and Company. The initial draft of this manuscript was written while employed at Yale New Haven Hospital

Disclosure of interest

A.M.Z. received research funding (institutional) from Celgene/BMS, Abbvie, Astex, Pfizer, Medimmune/AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Trovagene, Incyte, Takeda, Novartis, Aprea, and ADC Therapeutics. A.M.Z participated in advisory boards, and/or had a consultancy with and received honoraria from AbbVie, Otsuka, Pfizer, Celgene/BMS, Jazz, Incyte, Agios, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novartis, Acceleron, Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo, Cardinal Health, Taiho, Seattle Genetics, BeyondSpring, Trovagene, Takeda, Ionis, Amgen, Janssen, Epizyme, Syndax, and Tyme. A.M.Z received travel support for meetings from Pfizer, Novartis, and Trovagene.

J.Z. is an employee at Eli Lilly and Company. None of these relationships were related to the development of this manuscript. The conceptualization and initial versions of this manuscript were drafted while J.Z. was an employee of Yale New Haven Hospital

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2059–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiyoi H, Kawashima N, Ishikawa Y. FLT3 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: Therapeutic paradigm beyond inhibitor development. Cancer Science. 2020;111(2):312–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazarbachi A, Bug G, Baron F, et al. Clinical practice recommendation on hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia patients with FLT3-internal tandem duplication: a position statement from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2020;105(6):1507–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlenk RF, Dohner K, Krauter J, et al. Mutations and treatment outcome in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1909–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hannum C, Culpepper J, Campbell D, et al. Ligand for FLT3/FLK2 receptor tyrosine kinase regulates growth of haematopoietic stem cells and is encoded by variant RNAs. Nature. 1994;368:643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antar AI, Otrock ZK, Jabbour E, Mohty M, Bazarbachi A. FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia: ten frequently asked questions. Leukemia. 2020;34(3):682–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterlin P, Chevallier P, Knapper S, Collin M. FLT3 ligand in acute myeloid leukemia: a simple test with deep implications. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2020;62(2):264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakao M, Yokota S, Iwai T, et al. Internal tandem duplication of the flt3 gene found in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 1996;10:1911–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto Y, Kiyoi H, Nakano Y, et al. Activating mutation of D835 within the activation loop of FLT3 in human hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2001;97:2434–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janke H, Pastore F, Schumacher D, et al. Activating FLT3 mutants show distinct gain-of-function phenotypes in vitro and a characteristic signaling pathway profile associated with prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e89560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choudhary C, Schwäble J, Brandts C, et al. AML-associated Flt3 kinase domain mutations show signal transduction differences compared with Flt3 ITD mutations. Blood. 2005;106(1):265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sperling AS, Gibson CJ, Ebert BL. The genetics of myelodysplastic syndrome: from clonal haematopoiesis to secondary leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:5–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malcovati L, Galli A, Travaglino E, et al. Clinical significance of somatic mutation in unexplained blood cytopenia. Blood. 2017;129:3371–3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding L, Ley TJ, Larson DE, et al. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2012;481(7382):506–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, Ley TJ, Miller C, et al. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2059–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welch JS, Ley TJ, Link DC, et al. The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. 2012;150:264–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunet S, Labopin M, Esteve J, et al. Impact of FLT3 internal tandem duplication on the outcome of related and unrelated hematopoietic transplantation for adult acute myeloid leukemia in first remission: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bullinger L, Döhner K, Döhner H. Genomics of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Diagnosis and Pathways. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:934–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daver N, Schlenk RF, Russell NH, Levis MJ. Targeting FLT3 mutations in AML: review of current knowledge and evidence. Leukemia. 2019;33(2):299–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kottaridis PD, Gale RE, Langabeer SE, et al. Studies of FLT3 mutations in paired presentation and relapse samples from patients with acute myeloid leukemia: implications for the role of FLT3 mutations in leukemogenesis, minimal residual disease detection, and possible therapy with FLT3 inhibitors. Blood. 2002;100(7):2393–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi K, Jabbour E, Wang X, et al. Dynamic acquisition of FLT3 or RAS alterations drive a subset of patients with lower risk MDS to secondary AML. Leukemia. 2013;27:2081–2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bewersdorf JP, Ardasheva A, Podoltsev NA, et al. From clonal hematopoiesis to myeloid leukemia and what happens in between: Will improved understanding lead to new therapeutic and preventive opportunities? Blood Rev. 2019;37:100587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014. 371:2488–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knapper S, Russell N, Gilkes A, et al. A randomized assessment of adding the kinase inhibitor lestaurtinib to first-line chemotherapy for FLT3-mutated AML. Blood. 2017;129:1143–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone RM, Fischer T, Paquette R Phase IB study of the FLT3 kinase inhibitor midostaurin with chemotherapy in younger newly diagnosed adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2012; 26: 2061–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee BH, Williams IR, Anastasiadou E, et al. FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations induce myeloproliferative or lymphoid disease in a transgenic mouse model. Oncogene. 2005;24:7882–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic Classification and Prognosis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2209–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith CC, Wang Q, Chin CS, et al. Validation of ITD mutations in FLT3 as a therapeutic target in human acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2012;485:260–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burchert A, Bug G, Fritz LV, et al. Sorafenib Maintenance After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Acute Myeloid Leukemia With FLT3-Internal Tandem Duplication Mutation (SORMAIN). J Clin Oncol. 2020;10;38(26):2993–3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly LM, Kutok JL, Williams IR, et al. PML/RARalpha and FLT3-ITD induce an APL-like disease in a mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8283–8288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer SE, Qin T, Muench DE, et al. DNMT3A Haploinsufficiency transforms FLT3ITD myeloproliferative disease into a rapid, spontaneous, and fully penetrant acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:501–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yilmaz M, Daver N, Borthakur G, et al. FLT3 inhibitor based induction and allogeneic stem cell transplant in complete remission 1 improve outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia with very low FLT3 allelic burden. Am J Hematol. 2021. Aug 1;96(8):E275–E279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollyea DA, Bixby D, Perl A, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Version 2.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(1):16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlenk RF, Kayser S, Bullinger L, et al. Differential impact of allelic ratio and insertion site in FLT3-ITD-positive AML with respect to allogeneic transplantation. Blood. 2014;124:3441–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiede C, Steudel C, Mohr B, et al. Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in 979 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: association with FAB subtypes and identification of subgroups with poor prognosis. Blood. 2002;99:4326–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linch DC, Hills RK, Burnett AK, Khwaja A, Gale RE. Impact of FLT3(ITD) mutant allele level on relapse risk in intermediate-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2014;124:273–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnittger S, Bacher U, Kern W, et al. Prognostic impact of FLT3-ITD load in NPM1 mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:1297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakaguchi M, Yamaguchi H, Najima Y, et al. Prognostic impact of low allelic ratio FLT3-ITD and NPM1 mutation in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2018;2:2744–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abu-Duhier FM, Goodeve AC, Wilson GA, et al. Identification of novel FLT-3 Asp835 mutations in adult acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2001;113(4):983–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]