Abstract

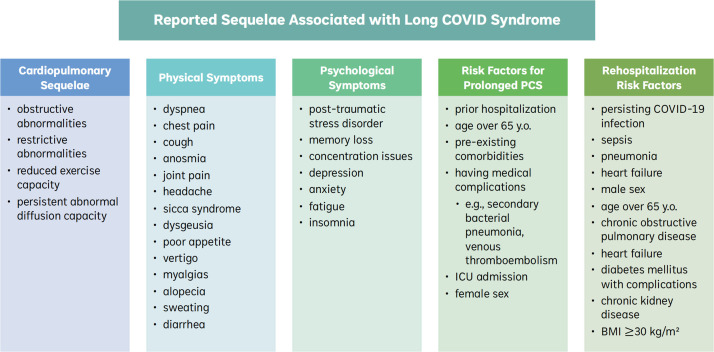

Long COVID, or post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, is characterized by multi-organ symptoms lasting 2+ months after initial COVID-19 virus infection. This review presents the current state of evidence for long COVID syndrome, including the global public health context, incidence, prevalence, cardiopulmonary sequelae, physical and mental symptoms, recovery time, prognosis, risk factors, rehospitalization rates, and the impact of vaccination on long COVID outcomes. Results are presented by clinically relevant subgroups. Overall, 10–35% of COVID survivors develop long COVID, with common symptoms including fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain, cough, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, memory loss, and difficulty concentrating. Delineating these issues will be crucial to inform appropriate post-pandemic health policy and protect the health of COVID-19 survivors, including potentially vulnerable or underrepresented groups. Directed to policymakers, health practitioners, and the general public, we provide recommendations and suggest avenues for future research with the larger goal of reducing harms associated with long COVID syndrome.

Keywords: Long COVID syndrome, Post-acute, Cardiovascular, Respiratory, COVID-19

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has seen a growing number of individuals recover from SARS-CoV-2 virus infection with long-term complications.1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), long COVID (or post-acute COVID-19 syndrome) is defined as a condition occurring in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually within 3 months from the onset of COVID-19 with persisting symptoms that cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis.2, 3, 4, 5 Given the vast emerging literature on this new public health concern, there is a need for an up-to-date review on long COVID syndrome. Here, we review the important epidemiological and clinical aspects of the disease. We provide an overview of the international public health context, cardiorespiratory sequelae, physical and mental health symptoms, re-hospitalization rates, risk factors, biomarkers, and the impact of vaccine status on long COVID outcomes. We also describe evidence of clinical disparities in relevant subgroups, such as differences in long COVID outcomes between male and female sex.

Efforts of international public health organizations to define long COVID syndrome

The widespread outbreak of multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants has brought long-term cardiorespiratory complications into the forefront of public concern, including the need to precisely quantify the exact prevalence of long COVID as variants develop. Originally coined in Spring 2020, “long COVID” was initially used to describe anecdotal observations of prolonged symptoms after COVID-19 infection.6 Despite the aforementioned attempts at delineating a practical definition of this disease, there remains variability in the consensus and rigor of a systematic definition of long COVID between health authorities and organizations.6

The WHO provided a clinical case definition for long COVID (mentioned earlier) using a Delphi consensus via an international working group in October 2021 involving patients, patient-researchers, external experts, and WHO staff, among others.2 The WHO has also created a Global COVID-19 Clinical Platform Case Report Form for clinicians and patients to contribute clinical data, with the aim of reporting medium and long-term consequences of long COVID.7 This self-report form can be used by clinicians and individuals to better quantify the extent and duration of long COVID syndrome. However, a major barrier to accurate assessments of long COVID in general is the biases in self-reporting or under-reporting of mild cases altogether.

The United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a guidance document in September 2021 that defined long COVID as “a wide range of new, returning, or ongoing health problems people can experience four or more weeks after first being infected with the virus that causes COVID-19”.8 In the same document, the CDC acknowledged the effects of long COVID on multi-organ systems, which can differ in rates of hospitalization for the elderly, children, and adolescents.8 At the same time, the US Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Justice released a guidance statement on "long COVID", classifying it as a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.9 This classification serves to recognize long COVID as a significant health issue with debilitating consequences that are protected under US federal laws which protect people with disabilities from discrimination.9

Incidence and prevalence of long COVID disease symptoms

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, approximately 423 million people with SARS-CoV-2 virus infections have been reported, with about 6.3 million deaths worldwide as of June 2022.10 Results from multiple studies suggest that up to 40% of initial COVID-19 survivors proceed to develop some symptoms of long COVID syndrome.11, 12, 13 However, the actual incidence is suspected to be higher due to the likelihood of unreported cases in conjunction with the non-specific and non-quantifiable nature of mild cases.1

Some aspects of long COVID recovery are similar to recovery patterns from other viral illnesses, critical illnesses, and sepsis, while other unexplained persisting trends are unique to the SARS-CoV-2 virus.1 Notably, the expected prognosis of long COVID remains to be elucidated, likely due to differences in incidence and severity between COVID-19 variants and the unclear impact of vaccination on the risk of long COVID. Studies between 2020 and 2021 reported by the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies reported that 25% of individuals experienced prolonged symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction, with 10% still experiencing symptoms after 3 months.14 As of June 2022, the incidence of long COVID is estimated to be 10–35% in the population who had COVID and up to 85% for hospitalized patients.12 Here, we provide a detailed synthesis of cardiopulmonary abnormalities and persistent symptoms associated with long COVID syndrome.

Cardiopulmonary sequelae

A variety of long-term cardiopulmonary complications have risen to greater clinical attention as a result of long COVID syndrome. After the acute phase of COVID-19, cardiopulmonary tests may be performed to monitor possible sequelae, such as complete lung function testing (e.g., spirometry, lung volumes, diffusing capacity, 6 minute walk test, cardiopulmonary exercise testing), chest computed tomography, electrocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, Holter monitoring, and stress tests.1 It is important to note that long-term pulmonary data regarding prevalence and severity are constantly evolving due to the changing COVID-19 environment (between virus variants, vaccination rates, and public health measures) and the lack of consistent guidelines in management and evaluation of cardiopulmonary sequelae for this syndrome.1 Nonetheless, there are some preliminary findings of how long COVID may affect the cardiopulmonary system.

Evidence from several U.S. and Chinese studies conducted between 2020 and 2021 suggests the presence of persistent abnormalities in pulmonary function such as a reduction in diffusion capacity, especially among individuals with initial severe lung involvement and pneumonia.15, 16, 17 A 2021 U.S. study re-assessed 102 critically ill patients admitted to the University of Virginia Medical Center intensive care unit (ICU) with COVID-19 approximately 6 weeks after discharge.15 It was reported that 15% had obstructive abnormalities, 19% had restrictive abnormalities, and 27% had reduced exercise capacity on the 6 min walk test.15 Another large-scale 2021 study of 1733 discharged patients 6 months post-infection follow up in Wuhan, China from Jin Yin-tan Hospital reported that 56% had persistent abnormal diffusion capacity at 6 months.16 Overall, the most common cardiopulmonary issues were reduced diffusion capacity ventilatory restrictive defects and persistent radiographic abnormalities on computed tomography (CT).16,18 The proportion of patients with diffusion impairment were 22% for severity scale 3 (not requiring supplemental oxygen), 29% for scale 4 (requiring supplemental oxygen), and 56% for scale 5–6 (requiring high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), non-invasive ventilation (NIV) or invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV)); median CT scores as defined by the study were 3.0 (interquartile range [IQR] 2.0–5.0) for severity scale 3, 4.0 (3.0–5.0) for scale 4, and 5.0 (4.0–6.0) for scale 5–6.16

Physical and mental symptoms

The most commonly reported complications of long COVID are persistent physical and mental symptoms. The majority of individuals with long COVID show microbiological, biochemical, and radiological recovery with negative PCR tests.13 However, clinical abnormalities persist (e.g., dyspnea at rest and exertion) despite normal physical or cardiopulmonary function tests.

An UpToDate literature review and compiled analysis of long COVID data stated that the most commonly reported physical symptoms were fatigue (13–87%), dyspnea (10–71%), chest pain/tightness (12–44%), and cough (17–34%).1 Less common symptoms include anosmia, joint pain, headache, sicca syndrome, dysgeusia, poor appetite, vertigo, myalgias, insomnia, alopecia, sweating, and diarrhea.1 Symptoms can be continuous or relapsing and remitting in nature, with the persistence of one or more acute COVID symptoms or reappearance of symptoms.13,19 A 2021 cohort study of 111 Swedish patients found that 10% of COVID-19 survivors discharged from the ICU developed polyneuropathy or myopathy versus 3.4% among other ICU patients.20 In a 2020 U.S. cohort study of 45 hospitalized patients 2 months after discharge, the most commonly reported symptoms included dyspnea with stair climbing (24%), shortness of breath/chest tightness (17%), cough (15%), and loss of taste or smell (13%).21 A 2020 Swiss study of 410 outpatients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 at the Geneva University Hospitals reported fatigue (21%), loss of taste or smell (17%), dyspnea (12%), and headache (10%) 7–9 months after initial COVID-19 diagnosis.22

Common psychological symptoms reported from a 2021 UK post-hospitalization study of 100 patients included post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (18%), memory loss (18%), and concentration difficulties (16%), with greater severity of mental illness symptoms among those who were admitted to the ICU.23 By comparison, the incidence of PTSD reported in non-COVID ICU patients can be 13–25%, with patients often experiencing mood issues, anxiety, or depression as a result of a traumatic ICU experience.24, 25, 26, 27, 28 A 2020 Canadian study of 78 outpatients reported that 22% of patients had depression or anxiety and 23% had persistent psychological issues at three months.29 Among those discharged from the ICU, 23% of 478 respondents in a 2021 France study reported anxiety, 18% reported depression, and 7% reported post-traumatic symptoms.30 In a 2021 Chinese study of 1733 hospitalized patients 6 months after discharge, commonly reported symptoms were fatigue or muscle weakness (63%), sleep difficulties (26%), dyspnea (26%), and anxiety or depression (23%).16 In a follow-up study 12 months after discharge, 20% of respondents reported fatigue/weakness, while the proportion of patients with dyspnea (30%) and anxiety (26%) had increased.31

Mobility limitations have also been noted. A 2020 retrospective study of 1300 U.S. hospitalized patients reported that 60% of survivors were unable to independently perform all activities of daily living after one month, even with in-home assistance.32 In another 2021 study of 238 hospitalized patients in Italy, 53% reported functional impairment after 4 months, as measured by the Short Physical Performance Battery score and two-minute walk test.17 Notably, it remains to be discerned whether these symptoms and findings are due to long COVID itself, pre-existing conditions, or prolonged hospitalization with enforced bedrest as a result of ICU stay.

Finally, although data in children are scarce, evidence from the first study of long COVID diagnosed in 129 children between March and November 2020 at the Gemelli University Hospital in Italy suggest that more than half of children aged 6 to 16 years who contracted the virus had at least one symptom lasting more than 4 months, with 43% impaired by these symptoms during daily activities.33 A 2021 Swiss study in 1355 children and adolescents (median age 11 years) reported that 4% of experienced at least one symptom lasting over 3 months, with the most frequently reported symptoms being tiredness (3%) and poor concentration (2%).34

Recovery time and prognosis

Existing long COVID studies also suggest a variability in disease progression. The expected recovery time and prognosis of long COVID appear to depend on pre-existing risk factors and acute COVID-19 infection severity. A 2021 Swedish study of over 2000 participants revealed a short recovery period (of up to 2 weeks) among those with mild infections and a longer recovery (over 2–3 months) among those with severe infections (with the severity defined based on patient-reported grading of ‘mild’ or ‘severe’).35 In addition, a 2021 Swedish study of 111 patients reported 33% of outpatients had persistent symptoms and 19% had new or worsening symptoms 2 months after discharge.20

Consensus from multiple studies conducted in the early phase of the pandemic indicate that fatigue, dyspnea, chest tightness, cognitive impairments, and psychological issues may last up to a year.36, 37, 38, 39, 40 Persistent cough usually resolves within 3 months.31,41 Chest pain persists 2–3 months after recovery following acute virus infection.31,36,38 Concentration and memory difficulties typically last up to 2 months after infection.23 Finally, psychological disorders (anxiety, depression, PTSD) are more common in those who had acute COVID-19 infection than other viral infections and persist for more than 6 months.23,31,32,36,42 Notably, some of these symptoms could be due to the uncertainty of the pandemic itself and pandemic stressors such as social isolation.

Risk factors and re-hospitalization rates

Studies have also attempted to identify risk factors for long COVID and related rehospitalizations. Evidence from multiple studies conducted between 2020 and 2021 indicate risk factors for a longer recovery course include being hospitalized, older age with pre-existing comorbidities, having medical complications (e.g., secondary bacterial pneumonia, venous thromboembolism), and having a prolonged ICU admission.23,38,43,44 In a 2020 Italian study with over 100 participants, people aged 50+ years who were hospitalized in an ICU were more likely (47%) to experience residual symptoms than younger people aged between 18 and 35 years (26%).41 Young, otherwise healthy patients with mild disease also recovered more rapidly than older patients or those with multiple co-morbidities, although 26% of those aged 18–35 years still experienced prolonged symptoms.41 In the UK, it was noted that there was a higher risk of developing respiratory disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease among long COVID patients than among patients discharged with non-COVID issues.45

During early studies of the pandemic in mid-2020, an estimated 10–20% of individuals hospitalized with COVID-19 in the U.S. required rehospitalization within 2–3 months.20,32,45, 46, 47 In a later 2021 U.K. study, approximately 1.6% of individuals faced multiple rehospitalizations, with the median time to readmission being 6 days.46 The commonly reported reasons for rehospitalization were persistent COVID-19 infection (30%), sepsis (8.5%), pneumonia (3.1%) and heart failure (3.1%).48 Notably, most of these metrics were taken before widespread vaccination and use of anti-inflammatory medications to treat COVID-19. Risk for rehospitalization was reportedly higher for males, those aged over 65 years, and for individuals discharged to skilled nursing facilities or home health services.46 Further risk factors for rehospitalization include the presence of co-morbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, diabetes mellitus with complications, chronic kidney disease, and a body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m².46

Impact of vaccination status on long COVID severity

It is well established that being vaccinated with two or more doses reduces the likelihood and severity of acute COVID-19 infection. However, the literature on the impact of vaccination on the subsequent development of long COVID syndrome is not as well characterized. A community-based, nested, case-control UK study using self-reported data from 1.2 million people reported that double vaccination reduces the risk of developing long COVID by half.49

Evidence suggests that vaccinating individuals who have long COVID syndrome can prevent persistent symptoms from worsening. In some cases, vaccination may also improve symptoms altogether, with a possible rationale due to the protective effect of multiple vaccinations at preventing recurrent virus infections.49 For example, in a 2021 study of 55 Dutch healthcare workers, T cell and IgG responses against SARS-CoV-2 were detected in mRNA vaccinated individuals one year after COVID-19 infection.50 A U.K. case-control study with over 4000 participants found that two vaccine doses reduced the prevalence and severity of long COVID symptoms compared to no vaccine, with vaccinated individuals more likely to be asymptomatic.51

Another retrospective cohort study using over 81 million U.S. TriNetX electronic health records examined outcomes for long COVID-19 sequelae 6 months after a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, and associations between the number of vaccine doses (1 vs. 2) and age (< 60 vs. ≥ 60 years) were assessed. Receiving one dose was associated with lower subsequent risk of respiratory failure, ICU admission, intubation or ventilation, hypoxaemia, oxygen requirement, hypercoagulopathy, venous thromboembolism, seizures, psychotic disorder, and hair loss, while two doses was associated with even lower risks for most outcomes.52 The mechanism is likely due to lowering the risk or severity of developing a second COVID-19 infection. In another study with 910 patients in France who already had long COVID syndrome, the COVID-19 vaccine reduced the severity of long COVID, improved quality of life 2 months after vaccination, and doubled the remission rate of long COVID symptoms.53 However, studies on the impact of vaccination on long COVID are currently scarce and heterogeneous.

Sex and gender considerations

An important topic is the effect of sex and gender on long COVID and its outcomes. A 2021 prospective cohort study of 377 participants found that female sex was independently associated with an increased risk of long COVID syndrome.54 A postulated reason for this increased risk is that SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers persistent autoimmune responses, and autoimmunity is substantially more likely to occur in women than men, with 80% of all autoimmune disorders occurring in women.55,56 It is hypothesized that chronic long COVID symptoms are due to immune responses affecting multiple organs and tissues, where women have higher innate immune responses.56 Another hypothesis is that, compared to men, women are more socially inclined to disclose pain and distress and to visit family physicians, resulting in increased reporting.55,56

In addition, there is interesting but potentially conflicting data on the disparity of long COVID between sexes. For example, after one month, some studies report higher rehospitalization rates for male patients (HR, 1.45, 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.03), while other studies report no difference between sexes (p<0.001).32,57 Female sex and age less than 50 years are considered risk factors for long COVID incidence. Meanwhile, predictors of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection (older age, male sex, co-existing morbidities) fail to predict the future occurrence of long COVID. Other trends indicate acute symptoms are more common in men, while chronic symptoms are more common in women, especially for those living in social deprivation and with pre-existing conditions.58,59 A 2021 UK study found that those of female sex are more likely to have fatigue and depression as symptoms of long COVID (without adjustment of previous mental illness history).60

Gender disparities of long COVID have scarcely been reported or assessed in clinical or epidemiological studies to date. However, it was noted that the severity and duration of long COVID symptoms may impede individual's ability to return to work.61 This may affect perimenopausal and menopausal women who already experience inequality in the workplace, as the COVID-19 pandemic can cause additional informal caregiving burdens.61 In addition, many symptoms of long COVID (fatigue, muscle aches, palpitations, cognitive impairment, etc.) overlap with perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms, which creates diagnostic uncertainty in this population.61

Knowledge gaps between clinical subgroups

While the need for analyzing long COVID literature is well-acknowledged, there is greater ambiguity in whether differences exist in the incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of long COVID syndrome between clinically relevant subgroups. For example, some studies report that symptoms did not appear to be related to the severity of the acute illness or to the presence of pre-existing medical conditions, while other studies report a higher incidence of long COVID among those who experienced severe acute COVID-19 infection.1,62 Furthermore, a systematic review has shown that Black and Hispanic populations experience disproportionately higher rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19–related mortality.63 It is suspected that the same racial and ethnic trends would translate to long COVID outcomes, although there currently lacks data stratified by these demographics. Further evidence is needed to identify important demographic trends and clarify potential conflicts in the long COVID literature.

Future directions

The knowledge gap regarding the cardiorespiratory sequelae and other long COVID-related epidemiological disparities has been highlighted as being of critical importance by the WHO and infectious disease scientists around the world. However, the scope of long COVID knowledge is limited by several factors. Many long COVID studies, albeit with large sample size, lack appropriate baseline or comparison groups such as an uninfected reference groups or individuals with other non-COVID viral infections. Studies also often do not provide a clear definition of long COVID based on measurable clinical parameters, instead using non-specific or self-reported symptoms that may be hard to quantify. There is a pressing need to consolidate discrepancies in existing literature and establish quantifiable parameters with universal definitions regarding the incidence, prevalence, and duration of long COVID in high quality studies.

Furthermore, it is unclear if COVID-19 variants may have differing impacts on the duration and intensity of long COVID. The predominant COVID-19 variant can only be inferred based on geographical location and time of the original study. For this review, most of the available data were limited to early phases of the pandemic, while differences in long COVID prevalence for those fully vaccinated or infected with later variants (e.g., delta and omicron) remain to be discerned globally. Thus, the effects of later variants on long COVID outcome remain a key knowledge gap for future investigations into long-term complications of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Summary of Clinical Sequelae Associated with Long COVID Syndrome. Abbreviations: y.o.: years old; ICU: intensive-care unit; COVID-19: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2); BMI: body mass index.

Conclusion

Overall, 10–35% of initial COVID survivors develop long COVID syndrome, with common symptoms being fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain, cough, depression, anxiety, PTSD, memory loss, and concentration difficulties. Mild initial infections point to shorter durations of long COVID syndrome, although the severity or duration of long COVID increasingly worsens with risk factors such as hospitalization for initial infection, presence of co-existing morbidities, older age, and female sex. Finally, there remains a need for further high-quality research on the incidence, prevalence, and duration of long COVID with universally defined clinical parameters.

Sources of Funding and Support

Dr. Filion is supported by a Senior salary support award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – santé (Quebec Foundation for Research – health) and a William Dawson Scholar award from McGill University. There is no other funding to disclose.

Authors' Contributions

All authors had access to the data and a role in writing the manuscript.

Katherine Huerne was responsible for substantial contributions to conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work. All authors were responsible for drafting of the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors were responsible for final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Clinical significance

-

•

Findings suggest that 10–40% of initial COVID survivors develop long COVID, with common physical symptoms being fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain and cough.

-

•

Common psychological symptoms include depressed mood, anxiety, memory loss, and difficulty concentrating.

-

•

Mild initial viral infections may be associated with shorter durations and lower incidence rates of long COVID.

-

•

Evidence suggests that risk factors for long COVID include hospitalization, presence of pre-existing morbidities, older age, and female sex.

Appendix

Supplemental methods

We narratively reviewed the available published literature on long COVID syndrome. Peer-reviewed databases (PubMed, Scopus) and grey literature (Google Scholar) were from inception through January 13th, 2022. Articles were retrieved using search terms and medical subject heading terms (when available) related to: (1) long COVID syndrome, (2) incidence and prevalence of long COVID symptoms, (3) cardiorespiratory sequelae, (4) physical symptoms, (5) mental symptoms, (6) recovery time and prognosis, (7) risk factors, (8) re-hospitalization rates, (9) impact of vaccine status on long COVID severity, and (10) sex and gender considerations in long COVID syndrome.

Observational studies and review articles discussing the pathophysiology, epidemiology, and treatment considerations of long COVID were considered relevant. Titles and abstracts were screened, and citations considered potentially eligible were retrieved for full-text review. References of included articles were also searched for relevance, as were articles of major peer-reviewed journals that were not yet indexed. The grey literature was searched for relevant clinical and epidemiologic information via major public health websites including the World Health Organization, the Canadian, and American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Extracted epidemiologic data included: study design, study population, clinical outcomes, year, and type of COVID-19 variant. Abstracts, editorials, and conference proceedings were excluded. Only articles published in English were included.

Summary of search process

Searches were performed according to the table of search strings listed below (see Table 1). The titles and abstracts of all articles (if less than 300 hits) or the first 300 hits per search were screening according to the following eligibility criteria:

-

(1)

If the article was an epidemiological study, the study must have reported on at least one aspect of long COVID syndrome (e.g., cardiorespiratory, physical symptoms, mental symptoms, biomarkers, vaccination, risk factors, hospitalization). The study design must be a cross-sectional, correlational, cohort, case-control, field trial, clinical trials, or in vitro study (taken from human samples with long COVID). The sample population is humans only, and the comparator group may have a control or no control. The date of publication is from Nov 2020 onwards to correspond to the first onset of COVID-19 discovery.

-

(2)

If the article was a review, the document must be a comprehensive overview of some aspect of long COVID syndrome (e.g., cardiorespiratory, physical symptoms, mental symptoms, biomarkers, vaccination, risk factors, hospitalization). The types of accepted reviews are systematic reviews, medical report provided by health organizations, public health press releases, or guidance documents. The sample population is humans only and the date of publication is from Nov 2020 onwards.

Table 1.

Search summary.

| Databases | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Google Scholar | long COVID syndrome Filter: results since 2020 |

| long covid syndrome cardiorespiratory outcomes chronic fatigue muscle pain | |

| Filter: Results since 2021 | |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((long OR post-acute) AND (COVID AND syndrome)) |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY (long AND term AND post AND covid-19 AND syndrome AND (cardio OR respiratory)) | |

| Filter: Results since 2021 | |

| Filter: Results since 2022 | |

| PubMed | ("post-acute COVID-19 syndrome" [Supplementary Concept]) AND ("Cardiovascular Diseases"[Mesh] OR "Signs and Symptoms"[Mesh] OR "Mental Health"[Mesh] OR "Risk Factors"[Mesh] OR "Hospitalization"[Mesh] OR "Vaccines"[Mesh] OR "Sex"[Mesh] OR "Gender Identity"[Mesh]) |

| Filter: Results since 2020 | |

| Filter: Results since 2021 | |

| ("post-acute COVID-19 syndrome" [Supplementary Concept]) AND ("Cardiovascular Diseases"[Mesh]) Filter: Results since 2020 | |

| ("post-acute COVID-19 syndrome" [Supplementary Concept]) AND ("Signs and Symptoms"[Mesh]) Filter: Results since 2020 | |

| ("post-acute COVID-19 syndrome" [Supplementary Concept]) AND ("Mental Health"[Mesh]) Filter: Results since 2020 | |

| ("post-acute COVID-19 syndrome" [Supplementary Concept]) AND ("Risk Factors"[Mesh]) Filter: Results since 2020 | |

| ("post-acute COVID-19 syndrome" [Supplementary Concept]) AND ("Hospitalization"[Mesh]) Filter: Results since 2020 | |

| ("post-acute COVID-19 syndrome" [Supplementary Concept]) AND ("Hospitalization"[Mesh]) Filter: Results since 2020 | |

| ("post-acute COVID-19 syndrome" [Supplementary Concept]) AND ("Vaccines"[Mesh]) Filter: Results since 2020 |

Date Search Performed: January 13, 2022.

The full text was read for eligibility studies. Pertinent data related to long COVID syndrome from selected texts were read, extracted, and summarized (see Table 2 for summary of selected texts). References were screened to identify additionally relevant articles in a snowball manner.

Table 2.

Summary of select studies examining long COVID syndrome symptoms.

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Sample Size (+ context) |

Metrics | Outcome | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augustin et al. (2021) | longitudinal prospective cohort study | 958 Patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection | anosmia, ageusia, fatigue or shortness of breath as most common, persisting symptoms at month 4 and 7 and summarized presence of such long-term health consequences as post-COVID syndrome (PCS) | Four months post SARS-CoV-2 infection:

|

The on-going presence of either shortness of breath, anosmia, ageusia or fatigue as long-lasting symptoms even in non-hospitalized patients was observed at four- and seven-months post-infection and summarized as post-COVID syndrome (PCS). |

| Munblit et al. (2021) | long-term follow-up study questionnaire | 2,649 of 4755 (56%) discharged patients | severity, fatigue, respiratory issues, sex analysis, asthma and chronic pulmonary disease, mental health symptoms |

|

Almost half of adults admitted to hospital due to COVID-19 reported persistent symptoms 6 to 8 months after discharge. Fatigue and respiratory symptoms were most common, and female sex was associated with persistent symptoms. |

| Hossain et al. (2021) | prospective inception cohort study | 14,392 participants were recruited from 24 testing facilities across Bangladesh between June and November 2020 | Cardiorespiratory parameters measured at rest (heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation levels, maximal oxygen consumption, inspiratory and expiratory lung volume) |

|

In this cohort, at 31 weeks post diagnosis, the prevalence of long COVID symptoms was 16.1%. |

| Buttery et al. (2021) | survey | 3290 respondents, 78% female, 92.1% white ethnicity and median age range 45-54 years; 12.7% had been hospitalized. 494 (16.5%) | measured patient symptoms and their interactions with healthcare. |

|

Symptoms did not appear to be related to the severity of the acute illness or to the presence of pre-existing medical conditions. Analysis of free-text responses revealed three main themes: (1) experience of living with COVID-19: physical and psychological symptoms that fluctuate unpredictably; (2) interactions with healthcare that were unsatisfactory; (3) implications for the future: their own condition, society and the healthcare system, and the need for research |

| Philip et al. (2022) | mixed methods analysis from a UK wide survey | 4500 people with asthma (median age 50–59 years, 81% female), conducted in October 2020 | inhaler use, sex/gender analysis, breathing, metrics related to asthma |

|

Analysis of free text survey responses identified three key themes: (1) variable COVID-19 severity, duration and recovery; (2) symptom overlap and interaction between COVID-19 and asthma; (3) barriers to accessing healthcare. |

| Ayoubkhani et al. (2021) | retrospective cohort study | 47,780 individuals (mean age 65, 55% men) in hospital with covid-19 and discharged alive by 31 August 2020 | Rates of hospital readmission (or any admission for controls), all cause mortality, and diagnoses of respiratory, cardiovascular, metabolic, kidney, and liver diseases until 30 September 2020. Variations in rate ratios by age, sex, and ethnicity. |

|

Individuals discharged from hospital after covid-19 had increased rates of multiorgan dysfunction compared with the expected risk in the general population. The increase in risk was not confined to the elderly and was not uniform across ethnicities. |

| Jafri et al. (2022) | cross sectional study | 70 responders who suffered from COVID-19. | impact of event scale (IES-R), patient health questionnaire-9(PHQ-9) and corona anxiety scale (CAS) |

|

High level of post-traumatic stress was seen among participants who recovered from COVID-19, especially those patients who were symptomatic. Mild depression and anxiety were also noted among them. |

| Tleyjeh et al, (2022) | cohort study | 375 patients were contacted and 153 failed to respond | The medical research council (MRC) dyspnea scale, metabolic equivalent of task (MET) score for exercise tolerance, chronic fatigability syndrome (CFS) scale and World Health Organization-five well-being index (WHO-5) for mental health were used to evaluate symptoms at follow-up. |

|

Several risk factors were associated with an increased risk of PACS. Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who are at risk for PACS may benefit from a targeted pre-emptive follow-up and rehabilitation programs. |

| Islam et al. (2021) | interview | 327 patients | prevalence of dyspnea, observe co‐variables, and find predictors of dyspnea after 2 months of recovery from COVID‐19 |

|

In addition to that, patient smoking history (P = .012) and comorbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (P = .021) were found to be statistically significant among groups |

| Khodeir et al. (2021) |

online-based cross-sectional survey | 979 patients recovered from COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia | symptoms |

|

Long-term symptoms after recovery from COVID-19 warrant patient follow-up |

Conflicts of interest

We, the undersigned, state there are no conflicts of interest for our manuscript titled “Epidemiological and Clinical Perspectives of Long COVID

Syndrome”

Syndrome” .

.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajmo.2023.100033.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Mikkelsen, M.E. & Abramoff, B. Upto Date. COVID-19: evaluation and management of adults following acute viral illness (2022).

- 2.World Health Organization. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/345824/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post-COVID-19-condition-Clinical-case-definition-2021.1-eng.pdf (2021).

- 3.Organization World Health. World Health Organization; 2021. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Post COVID-19 condition.https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-post-covid-19-condition [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID). https://www.who.int/srilanka/news/detail/16-10-2021-post-covid-19-condition (2021).

- 5.Delgado, C. WHO releases first official long COVID Definition. verywellHealth https://www.verywellhealth.com/who-long-covid-definition-5207010#citation-3 (2021).

- 6.Alwan N.A., Johnson L. Defining long COVID: Going back to the start. Med (N.Y.) 2021;2:501–504. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2021.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global COVID-19 Clinical Platform Case Report Form (CRF) for post COVID condition (Post COVID-19 CRF).

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Post-COVID Conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Flong-term-effects.html (2021).

- 9.Office for Civil Rights (OCR). Guidance on “Long COVID” as a Disability under the ADA, Section 504, and Section 1557. HHS.gov (2021).

- 10.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.

- 11.Domingo, F.R. Waddell, L.A., Cheung, A.M., et al. Prevalence of long-term effects in individuals diagnosed with COVID-19: an updated living systematic review. http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2021.06.03.21258317 (2021) doi:10.1101/2021.06.03.21258317.

- 12.Pavli A., Theodoridou M., Maltezou H.C. Post-COVID syndrome: incidence, clinical spectrum, and challenges for primary healthcare professionals. Arch Med Res. 2021;52:575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raveendran A.V., Jayadevan R., Sashidharan S. Long COVID: an overview. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15:869–875. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajan, S., Khunti, K., Alwan, N., et al. In the wake of the pandemic: preparing for long COVID. [PubMed]

- 15.Ramani C., Davis E.M., Kim J.S., et al. Post-ICU COVID-19 outcomes. Chest. 2021;159:215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang C., Huang L., Wang Y., et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellan M., Soddu D., Balbo P.E., et al. Respiratory and psychophysical sequelae among patients with COVID-19 four months after hospital discharge. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.You J., Zhang L., Ni-Jia-Ti M.-Y.-L., et al. Anormal pulmonary function and residual CT abnormalities in rehabilitating COVID-19 patients after discharge. J Infect. 2020;81:e150–e152. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nabavi N. Long Covid: how to define it and how to manage it. BMJ m3489. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frithiof R., Rostami E., Kumlien E., et al. Critical illness polyneuropathy, myopathy and neuronal biomarkers in COVID-19 patients: a prospective study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2021;132:1733–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2021.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martillo M.A., Dangayach N.S., Tabacof L., et al. Postintensive care syndrome in survivors of critical illness related to coronavirus disease 2019: cohort study from a New York city critical care recovery clinic. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:1427–1438. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nehme M., Braillard O., Chappuis F., et al. Prevalence of symptoms more than seven months after diagnosis of symptomatic COVID-19 in an outpatient setting. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1252–1260. doi: 10.7326/M21-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halpin S.J., McIvor C., Whyatt G., et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1013–1022. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myhren H., Tøien K., Ekeberg O., et al. Patients’ memory and psychological distress after ICU stay compared with expectations of the relatives. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:2078–2086. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1614-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Askari Hosseini S.M, Arab M., Karzari Z., et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors and its relation to memories of ICU. Nurs Crit Care. 2021;26:102–108. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker A.M., Sricharoenchai T., Raparla S., et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1121–1129. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scragg P., Jones A., Fauvel N. Psychological problems following ICU treatment*: psychological problems following ICU treatment. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:9–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olafson K., Marrie R.A., Bolton J.M., et al. The 5-year pre- and post-hospitalization treated prevalence of mental disorders and psychotropic medication use in critically ill patients: a Canadian population-based study. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:1450–1461. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06513-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong A.W., Shah A.S., Johnston J.C., et al. Patient-reported outcome measures after COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020;56 doi: 10.1183/13993003.03276-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Writing committee for the COMEBAC study group et al. four-month clinical status of a cohort of patients after hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325:1525–1534. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang L., Yao Q., Gu X., et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:747–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowles K.H., McDonald M., Barrón Y., et al. Surviving COVID-19 after hospital discharge: symptom, functional, and adverse outcomes of home health recipients. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:316–325. doi: 10.7326/M20-5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buonsenso, D., Munblit, D., De Rose, C., et al. Preliminary evidence on long COVID in children. http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2021.01.23.21250375 (2021) doi:10.1101/2021.01.23.21250375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Radtke T., Ulyte A., Puhan M.A., et al. Long-term symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Havervall S., Rosell A., Phillipson M., et al. Symptoms and functional impairment assessed 8 months after mild COVID-19 among health care workers. JAMA. 2021;325:2015–2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiong Q., Xu M., Li J., et al. Clinical sequelae of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China: a single-centre longitudinal study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goërtz Y.M.J., Van Herck M., Delbressine J.M., et al. Persistent symptoms 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 infection: the post-COVID-19 syndrome? ERJ Open Res. 2020;6:00542–02020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00542-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carfì A., Bernabei R., Landi F., et al. Against COVID-19 post-acute care study group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:603–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hopkins C., Surda P., Whitehead E., et al. Early recovery following new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic - an observational cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49:26. doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-00423-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kosugi E.M., Lavinsky J., Romano F.R., et al. Incomplete and late recovery of sudden olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;86:490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tenforde M.W., Kim S.S., Lindsell C.J., et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network - United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:993–998. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1. March-June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heesakkers H., van der Hoeven J.G., Corsten S., et al. Clinical outcomes among patients with 1-year survival following intensive care unit treatment for COVID-19. JAMA. 2022;327:559–565. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barman M.P., Rahman T., Bora K., et al. COVID-19 pandemic and its recovery time of patients in India: a pilot study. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:1205–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCue C., Cowan R., Quasim T., et al. Long term outcomes of critically ill COVID-19 pneumonia patients: early learning. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:240–241. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06313-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayoubkhani D., Khunti K., Nafilyan V., et al. Post-covid syndrome in individuals admitted to hospital with covid-19: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021;372:n693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taquet M., Geddes J.R., Husain M., et al. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:416–427. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lavery A.M., Preston L.E., Ko J.Y., et al. Characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 patients discharged and experiencing same-hospital readmission - United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1695–1699. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6945e2. March-August 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anesi G.L., Jablonski J., Harhay M.O., et al. Characteristics, outcomes, and trends of patients with COVID-19-related critical illness at a learning health system in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:613–621. doi: 10.7326/M20-5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ledford H. Do vaccines protect against long COVID? What the data say. Nature. 2021;599:546–548. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mak W.A., Koeleman J.G.M., van der Vliet M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody and T cell responses one year after COVID-19 and the booster effect of vaccination: a prospective cohort study. J Infect. 2022;84:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antonelli M., Penfold R.S., Merino J., et al. Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: a prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:43–55. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00460-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taquet, M., Dercon, Q. & Harrison, P.J. Six-month sequelae of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection: a retrospective cohort study of 10,024 breakthrough infections. http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2021.10.26.21265508 (2021) doi:10.1101/2021.10.26.21265508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Tran, V.-T., Perrodeau, E., Saldanha, J., et al. Efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination on the symptoms of patients with long COVID: a target trial emulation using data from the ComPaRe e-cohort in France. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-1350429/v1 (2022) doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1350429/v1.

- 54.Bai F., Tomasoni D., Falcinella C., et al. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.11.002. S1198-743X(21)00629–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Why is long COVID-19 reported more often among women than men?

- 56.Ortona E., Malorni W. Long COVID: to investigate immunological mechanisms and sex/gender related aspects as fundamental steps for tailored therapy. Eur Respir J. 2022;59 doi: 10.1183/13993003.02245-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sotoodeh Ghorbani S., Taherpour N., Bayat S., et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of cases with reinfection, recurrence, and hospital readmission due to COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2022;94:44–53. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gebhard, C.E., Sütsch, C., Bengs, S. et al. Sex- and gender-specific risk factors of post-COVID-19 syndrome: a population-based cohort study in Switzerland. http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2021.06.30.21259757 (2021) doi:10.1101/2021.06.30.21259757.

- 59.Maxwell E. Unpacking post-covid symptoms. BMJ. 2021;n1173 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Townsend L., Dyer A.H., Jones K., et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PLoS ONE. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stewart S., Newson L., Briggs T.A., et al. Long COVID risk - a signal to address sex hormones and women's health. Lancet Reg Health - Europe. 2021;11 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buttery S., Philip K.E.J., Williams P., et al. Patient symptoms and experience following COVID-19: results from a UK-wide survey. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2021;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2021-001075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mackey K., Ayers C.K., Kondo K.K., et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19–related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:362–373. doi: 10.7326/M20-6306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.