Abstract

Many animal and plant pathogens use type III secretion systems to secrete key virulence factors, some directly into the host cell cytosol. However, the basis for such protein translocation has yet to be fully elucidated for any type III secretion system. We have previously shown that in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli the type III secreted protein EspA is assembled into a filamentous organelle that attaches the bacterium to the plasma membrane of the host cell. Formation of EspA filaments is dependent on expression of another type III secreted protein, EspD. The carboxy terminus of EspD, a protein involved in formation of the translocation pore in the host cell membrane, is predicted to adopt a coiled-coil conformation with 99% probability. Here, we demonstrate EspD-EspD protein interaction using the yeast two-hybrid system and column overlays. Nonconservative triple amino acid substitutions of specific EspD carboxy-terminal residues generated an enteropathogenic E. coli mutant that was attenuated in its ability to induce attaching and effacing lesions on HEp-2 cells. Although the mutation had no effect on EspA filament biosynthesis, it also resulted in reduced binding to and reduced hemolysis of red blood cells. These results segregate, for the first time, functional domains of EspD that control EspA filament length from EspD-mediated cell attachment and pore formation.

Subversion of host cell function is now recognized as a common theme in the pathogenesis of many bacterial infections (8). Such subversion can be displayed by bacterially induced cytoskeletal reorganization within target host cells, which is stimulated by bacterial activation of eukaryotic signal-transduction pathways. Particularly good examples of this phenomenon are the interactions of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) with mammalian intestinal epithelium. EPEC, an established etiological agent of human diarrhea, remains an important cause of mortality amongst young infants in developing countries, and EHEC is an emerging cause of acute gastroenteritis and hemorrhagic colitis, which are often associated with severe or fatal renal and neurological complications (32). Subversion of intestinal epithelial cell function by EPEC and EHEC leads to the formation of distinctive attaching and effacing (A/E) lesions, which are characterized by localized destruction (effacement) of brush border microvilli, intimate attachment of the bacillus to the host cell membrane, and formation of an underlying actin-rich pedestal-like structure in the host cell (31, 37). The genes involved in A/E lesion formation are mapped within a pathogenicity island known as the locus of enterocyte effacement, or the LEE region (26, 27, 34). These include the bacterial adhesion molecule intimin (18, 19), which mediates intimate bacterium-host cell interaction through binding to an intimin receptor (Tir), which is delivered by the LEE-encoded type III secretion system (16, 17) into the host cell plasma membrane (4, 20).

In addition to Tir, three other proteins, EspA (21), EspB (6), and EspD (24), which are integral to formation of A/E lesions, are known to be exported via the EPEC/EHEC type III secretion system. EspA is a structural protein and the major component of a large, transiently expressed, filamentous surface organelle termed the EspA filament (7, 23); EspA filaments form a direct link between the bacterium and the host cell and are required for protein translocation (23). Recently, multimeric EspA isoforms in EPEC culture supernatants and EspA-EspA protein interactions on solid phase have been demonstrated (5). The carboxy terminus of EspA comprises an alpha-helical region which demonstrates heptad periodicity whereby positions a and d in the heptad repeat unit abcdefg are occupied by hydrophobic residues, indicating a propensity for coiled-coil interactions. Nonconservative amino acid substitution of specific EspA heptad residues generated EPEC mutants defective in EspA filament assembly and A/E lesion formation (5), indicating that coiled-coil interactions are involved in assembly or stability of the EPEC EspA filament-associated type III translocon.

EspB secretion by EPEC in the absence of epithelial cells has been shown independently by several groups. However, this probably represents basal levels of secretion, since upon contact with host cells there is an immediate burst of EspB secretion and this secretion burst is strongly enhanced by intimate cell binding (40). Following bacterial attachment, EspB is translocated into the host cell, where it is localized to both membrane and cytosol cell fractions (36, 40). espB mutants are unable to translocate Tir (20), suggesting that functional EspB is also required for protein translocation. EspB is not thought to be a structural component of EspA filaments because EspB antibodies do not stain EspA filaments and, furthermore, intact EspA filaments can be observed on the surface of an EPEC espB mutant (12, 23). EspB exhibits weak homology with YopD (19% identity), and the structural organization of EspB is reminiscent of the YopD protein. Both proteins have only one putative transmembrane region and one predicted trimeric coiled-coil region (33). YopD, like EspB, is required for the translocation of effector proteins but is also itself translocated (9). The fact that EspA and EspB are required for translocation of Tir to the host cell membrane suggests that they may both be components of the translocation apparatus. Indeed, members of our group recently showed that EspB can bind and be copurified with EspA (12). However, formation of EspA filaments and binding of EspA filaments to the target host cell occurred even in the absence of EspB (12), suggesting that EspB modulates EspA filament activity and signals the transition from an adhesive to a translocation function. The mechanism by which EspB binds EspA and allows protein translocation is not known.

Previous studies have shown that proteins belonging to the EspD family (YopB from Yersinia and IpaB from Shigella) are part of the type III secretion apparatus involved in formation of a translocation pore in the host cell membrane (2). It was previously reported that, although EspD does not appear to be a structural component of the EspA filament, an espD EPEC mutant secretes only low levels of EspA and produces barely detectable EspA filaments (23). EspD is translocated into the host cell membrane and is required for cell attachment (38) and EPEC-induced hemolysis (39). In this report, we show EspD-EspD protein interaction and demonstrate that a radical mutation in the C-terminus coiled-coil domain of EspD affects EPEC-induced A/E lesion formation, EspA filament-mediated cell attachment, and EPEC-induced hemolysis without affecting EspA filament biosynthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth and maintenance of bacterial strains and plasmids.

The strains used in this study included EPEC strains E2348/69 (wild type), UMD872 (espA null mutant) (21) and UMD870 (espD null mutant) (24). The strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml) or kanamycin (50 μg/ml) as required. The plasmids used in the study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

List of plasmids

| Plasmid | Relevant features | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pLCL123 | pACYC184 containing espD gene in Sal1-Nru1 | 24 |

| pICC70 | pGAD424 expressing EspD | This study |

| pICC71 | pGBT9 expressing EspD | This study |

| pICC72 | pLCL123 expressing EspD with Ala340Arg substitution | This study |

| pICC73 | pLCL123 expressing EspD with Ala340Arg and Ala347Arg substitutions | This study |

| pICC74 | pLCL123 expressing EspD with Ala340Arg, Ala347Arg, and Gln354Arg substitutions | This study |

| pICC75 | pMALc-2 expressing MBP-N-EspD fusion protein | This study |

| pICC76 | pMALc-2 expressing MBP-C-EspD fusion protein | This study |

Yeast two-hybrid system.

espD was cloned following PCR amplification (30 cycles of 94°C for 60 s, 58°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 90 s) into the EcoRI/BamHI restriction sites of pGBT9 and pGAD424 (Clontech). pGBT9 is an ADH1-driven fusion vector containing the GAL4 binding domain, and pGAD424 contains the GAL4 activation domain. The primer combination 5′-AAGAATTCATGCTTAATGTAAATAACGATATCC-3′ and 5′-ATAGGATCCTTAGACCTGACCAACAATTTTAC-3′ was used with pLCL123 as template. The constructs were transformed into yeast strain PJ69-4A (MATa trp1-901 leu2-3, 112 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4D gal80D LYS2::GAL1-HIS3 GAL2-ADE1 met2::GAL7-lacZ) (15). They were initially selected for the plasmid-encoded TRP1 and LEU2 genes (11). The resulting transformants were then replica plated onto 3-aminotriazole-containing medium to select for the HIS3 reporter, and onto synthetic complete medium lacking Trp, Leu, and Ade to select for the ADE2 reporter. The function of the LacZ reporter was quantified in cell extracts by assaying for β-galactosidase activity using o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside as a substrate (11, 30). PJ69-4A, which was cotransformed with pGBT9-EspD and pGAD-EspB or pGBT9-EspB and pGAD-EspD and exhibited a negative yeast two-hybrid phenotype, served as negative controls (data not shown).

Sequence analysis and mutagenesis of heptad residues.

The EspD sequence was analyzed for the presence of predicted coiled-coil segments using the COILS algorithm described by Lupas (25) and available via the World Wide Web at http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/COILS_form.html. Predictions were weighted in favor of hydrophobic residues at positions a and d of the heptad repeat and were based on a window size of 28 residues.

Substitution of residues at positions Ala340, Ala347, and Gln354 with Arg was accomplished in a stepwise fashion using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) as described previously (5). Double-stranded pLCL123 or subsequently mutated plasmids were used as templates with complementary mutagenesis oligonucleotide pairs that incorporated single amino acid substitutions as follows: 5′-TTAAGTCAGAGTCGAAAGGCAGAGCTGG-3′/5′-CCAGCTCTGCCTTTCGACTCTGACTTAA-3′ (Ala340-Arg340), 5′-GAGCTGGAAAAACGAACTCTCGAGCTG - 3′ / 5′ - CAGCTCGAGAGTTCGTTTTTCCAGCTC-3′ (Ala47-Arg347), and 5′-GAGCTGCAAAACCGAGCGAATTATATAC-3′/5′-GTATATAATTCGCTCGGTTTTGCAGCTC-3′ (Gln354-Arg354).

Mutated plasmid was transformed to competent E. coli XLI-Blue cells following enzymatic selection of synthesized over parental DNA. Correct incorporation of the appropriate base changes was confirmed by sequencing of plasmid minipreps (ABI 377). Mutated plasmids were subsequently transformed into strain UMD870 (espD null mutant) for analysis of phenotypic effects.

HEp-2 cell adhesion.

Adhesion to HEp-2 cells was carried out according to the method of Cravioto et al. (3). Subconfluent HEp-2 cell cultures on glass coverslips were washed and incubated with bacteria (10 μl of bacterial broth culture/ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [DMEM] with 2% fetal calf serum) for 3 h at 37°C. After thorough washing to remove nonadhering bacteria, coverslips were fixed in 4% formalin. Adhesion was quantitatively assessed by counting 100 cells and determining the percentage of cells with adherent bacterial microcolonies; a minimum of five associated bacteria was considered to be a microcolony.

Hemolysis assay.

Hemolysis was assessed as previously described (35). Red blood cells (RBCs) were obtained from human type O blood by centrifugation and washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and a 3% suspension was added to polylysine-coated 30-mm-diameter tissue culture dishes for 20 min. Nonattached RBCs were removed by washing with PBS, and the resulting RBC monolayer was covered with 2 ml of HEPES-buffered DMEM without phenol red. Forty microliters of an overnight Luria-broth culture of EPEC was added to each RBC monolayer and the dishes were incubated for 4 h at 37°C, after which the culture medium was transferred to a microcentrifuge tube and bacteria were sedimented by centrifugation. Supernatant optical density was measured at 543 nm. Supernatants from uninfected RBC monolayers incubated under the same conditions were used to provide the baseline level of hemolysis (B); total hemolysis (T) was obtained from monolayers incubated with distilled water. Percent hemolysis (P) was calculated from the following equation: P = [(X − B)/(T − B)] × 100, where X is the optical density of the sample analyzed. Each result is the mean of three independent experiments.

Preparation of secreted proteins for Western blotting.

Preparation of EPEC secreted proteins for Western blotting with anti-EspA, -EspB, -EspD, and Tir antisera was performed as previously described (5).

Microscopy. (i) A/E lesion formation.

A/E lesion formation was assessed using the fluorescence actin staining (FAS) test (22). Fixed cell preparations were washed and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 4 min, and cytoskeletal actin was stained with a 5-μg/ml solution of fluorescein-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma) for 20 min. Coverslips were mounted and examined by incident light fluorescence and phase contrast; A/E lesion formation was indicated by intense actin fluorescence at the site of bacterial adhesion.

(ii) EspA and EspD immunofluorescence.

For microscopy, RBC monolayers were prepared on glass coverslips. Polyclonal antibody (23) was used to stain EspA filaments, and monoclonal antibody (7) was used to stain EspD. All antibody dilutions and immune reactions were carried out in PBS containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin (PBS-BSA). Formalin-fixed and washed HEp-2 cells or RBC monolayers were incubated with EspA or EspD antiserum (1:50 to 1:100) in PBS-BSA for 45 min at room temperature. After three 5-min washes in PBS, samples were stained with either fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Sigma) diluted 1:20 in PBS-BSA for 45 min; RBC preparations were simultaneously stained with wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to Texas red (Molecular Probes) in order to visualize the RBC membrane. Preparations were washed a further three times in PBS, mounted in glycerol-PBS, and examined by incident light fluorescence using either a Leitz Dialux or DMR microscope.

(iii) Electron microscopy of secreted EspD.

Infected HEp-2 cell or RBC monolayers were fixed in 0.1% glutaraldehyde for 15 min, washed in PBS-BSA, and incubated with EspD or EspA monoclonal antiserum (1:100) for 2 h. After three 5-min washes in PBS-BSA, cell monolayers were incubated with 10-nm-diameter gold bead-labeled goat anti-mouse serum (1:20) for 2 h. After further washing, cells were scraped from the plastic surface and centrifuged, and the cell pellets were fixed in 3% buffered glutaraldehyde. Samples were then processed for thin-section electron microscopy using standard procedures (23).

For electron microscopy of culture supernatants, overnight cultures of E2348/69 and UMD870 were used to seed fresh cultures at 1:50 dilutions in DMEM, which were then grown with shaking at 37°C. The cultures were grown until the optical density at 600 nm was ∼1.0 (4 h). The bacteria were then pelleted and the culture supernatant was filtered through 0.45-μm-diameter filters to remove any contaminating bacteria. The supernatants were then spun at 92,000 rpm in a TLA 100.3 ultracentrifuge rotor to pellet the secreted proteins. The pelleted proteins were then resuspended in 20 μl of PBS. For immunogold labeling, 4 μl of the secreted-protein preparation was applied to carbon-coated copper grids. The grids were then placed face down onto 50-μl drops of EspD monoclonal antiserum and incubated for 25 min. The grids were then washed on three consecutive drops of PBS and then applied to 50-μl drops of 10-nm gold-labeled goat anti-mouse serum (1:10 dilution) for 5 min. The grids were then washed three times in sterile distilled water, negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate, and viewed using a Philips CM100 microscope.

MBP-EspD affinity columns.

To determine possible homogeneous and heterogeneous protein interactions between EspD and secreted EPEC proteins, we constructed maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusions with the 177 amino-terminal amino acids (MBP-EspD-N) and the 130 carboxy-terminal amino acids (residues 250 to 380) (MBP-EspD-C) of EspD. The constructs were made by PCR from pLCL123. NdeI/BamHI-ended PCR products were obtained using the primer combinations 5′-AAGAATTCATGCTTAATGTAAATAACGATATCC-3′ and 5′-ATAGGATCCTTAAATTTTACTTTTTTGTGCTTTCTC-3′ for the N terminal and 5′-ATACATATGGGCGGGGTGTCTTCACTTAT-3′ and 5′-TTGGATCCTTAAACTCGACCGCTGACAATAC-3′ for the C terminal (1 cycle of 95°C for 5 min and then 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 58°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min). The PCR products were cloned into pMALC2 (New England Biolabs) generating plasmids pICC75 and pICC76, respectively. Column overlay experiments were carried out as described previously (11). Briefly, the recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli TG1 and log-phase cultures were induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside followed by incubation at 37°C for 3 h with shaking. For affinity columns, MBP or MBP-EspD-N or -C were bound to amylose resin according to the standard purification procedure (12). The columns were then overlaid with 25 ml of filtered culture supernatant from EPEC strain E2348/69 grown overnight in DMEM. Following washes with 10 volumes of column buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.4], 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA), MBP or MBP-EspD-N or -C and associated proteins were eluted with 10 mM maltose dissolved in column buffer. Fractions were collected in 1-ml volumes, and 15 μl of each fraction was subjected to Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with anti-MBP or anti-EspA, -EspB, -EspD and Tir antisera and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies.

RESULTS

EspD-EspD protein interaction using the yeast two-hybrid system.

In recent reports, we have demonstrated homogeneous and heterogeneous protein-protein interactions between different Esps, including EspA-EspA (5) and EspA-EspB (12). Considering that EspD is predicted to be a major component of a translocation pore in the host cell membrane, in this study we examined EspD-EspD interaction using the yeast two-hybrid system, which is designed to identify protein-protein interactions through the functional restoration of the yeast GAL4 transcriptional activator in vivo (15). DNA fragments encoding the EspD polypeptide were subcloned into pGAD424 to generate plasmid pICC70 and into the second yeast two-hybrid system vector, pGBT9 (generating plasmid pICC71) (Table 1). Plasmids pICC70 and pICC71 were cotransformed into yeast stain PJ69-4A. Replica plating of these colonies onto methianine uracil medium, which specifically selects for protein interaction, yielded vigorously growing colonies and hence a positive two-hybrid phenotype. No yeast colonies on methianine uracil medium were observed when using any of the single plasmid transformants (data not shown).

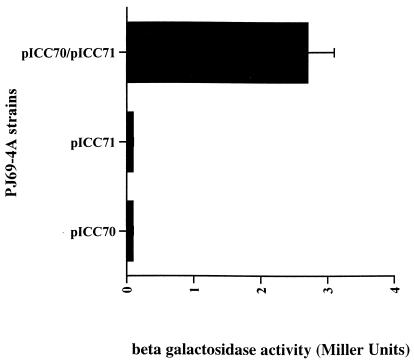

The function of the nonselective reporter, LacZ, was also assessed in these strains by measuring β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 1). The host (data not shown) or single plasmid-bearing strains exhibited low levels of β-galactosidase activity whereas, in the strain expressing EspD from both plasmids (PJ69-4A pICC70-pICC71), a 10-fold increase in the level of β-galactosidase Miller units was observed (Fig. 1). These results demonstrate EspD-EspD protein interaction.

FIG. 1.

Detection of EspD-EspD protein interaction using a yeast two-hybrid system. β-galactosidase assays showed a 10-fold increase in enzymatic activity in strains expressing EspD from the two yeast vectors compared with the single transformants. Error bar represents standard error from the mean of three independent experiments.

Mutagenesis of heptad repeat residues.

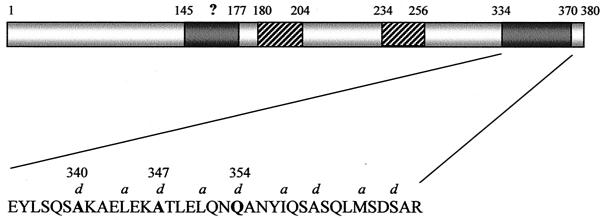

Analysis of the EspD sequence by the COILS algorithm identified a carboxy-terminal heptad repeat spanning residues 334 to 370 that was predicted to adopt a coiled-coil conformation with 99% probability (Fig. 2) (33, 38). By introducing hypothetical Arg substitutions in the sequence at various a and d heptad positions, it was possible to determine a combination of mutations which abolished the probability of coiled-coil formation. These predictions were subsequently used as the rational basis for the stepwise site-directed mutagenesis of plasmid pLCL123 (espD), creating pICC72 (Ala340Arg), pICC73 (Ala340Arg, Ala347Arg), and pICC74 (Ala340Arg, Ala347Arg, Gln354Arg) (Table 1). Following complementation of the espD null mutant strain UMD870 with pICC72, pICC73, and pICC74, the biological activity of the mutated EspD proteins was tested.

FIG. 2.

Structural organization of EspD from EPEC. The predicted carboxy-terminal coiled-coil segment (residues 334 to 370) is located downstream of a putative second coiled-coil region (145 to 177) and the two central transmembrane domain regions (180 to 204 and 234 to 256) (33, 38). The a and d position residues within the heptads are indicated, and residues targeted for mutagenesis are highlighted in bold.

Assessment of biological activity of coiled-coil EspD mutants.

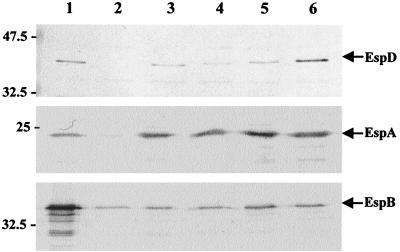

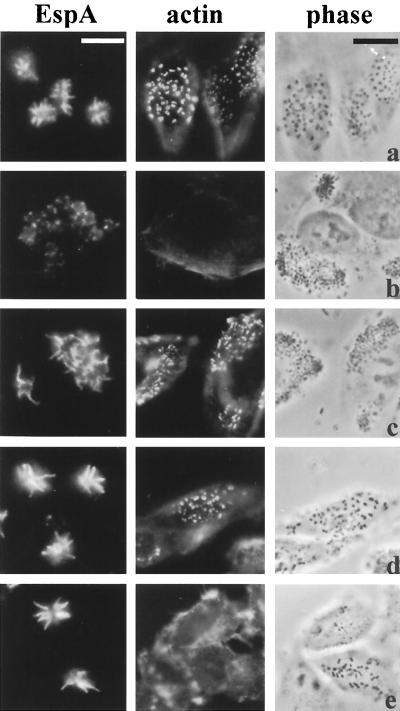

Analysis of supernatants for the presence of secreted EPEC proteins showed that the EspD coiled-coil mutations did not affect secretion of EspA (although, as previously reported in reference 23; low levels of EspA were secreted from the espD null mutant, strain UMD870) and EspB or that of the mutated EspD polypeptides (Fig. 3). EspD is essential for the elaboration of mature EspA filaments on the bacterial cell surface and for A/E lesion formation (Fig. 4). In order to identify the functional consequences of mutation at the carboxy terminal of EspD, the single, double, and triple mutant strains were assessed in the context of their ability to elaborate EspA filaments on the surface of the bacterium and induce A/E lesions on cultured HEp-2 cells. In contrast to an espD deletion mutation (UMD870), disruption of the coiled coil had no detectable effect on the biogenesis of EspA filaments in any of the strains (Fig. 4). A/E lesion formation by strains UMD870(pICC72) and UMD870(pICC73) was similarly unaffected (Fig. 4), whereas the coiled-coil mutation in strain UMD870(pICC74) resulted in attenuation of A/E lesion formation. The FAS reaction produced by strain UMD870(pICC74) was either very weak or negative, and quantitative adhesion assays showed that this strain displayed an ∼5-fold reduction in adherence compared to wild-type E2348/69 (Fig. 5). These results suggest that the mutations in the coiled-coil domain did not cause global structural disruption of EspD but rather had a local effect.

FIG. 3.

Detection of EspD, EspA, and EspB in EPEC supernatants. DMEM culture supernatants were analyzed by using Western blotting. Wild-type EPEC E2348/69 (lane 1), UMD870(pLCL123) (lane 3), UMD870(pICC72) (lane 4), UMD870(pICC73) (lane 5), and UMD870(pICC74) (lane 6) all demonstrated similar levels of the secreted proteins. EspD was absent from the supernatant of the espD deletion mutant strain UMD870 (lane 2), while UMD870 had reduced supernatant levels of EspA and normal levels of EspB.

FIG. 4.

EspA expression and A/E lesion formation on HEp-2 cells produced by EspD coiled-coil mutants. EspA fluorescence (column 1), FAS test actin fluorescence (column 2) and corresponding phase-contrast micrographs (column 3) of wild-type EPEC strain E2348/69 (a), espD deletion mutant strain UMD870 (b), cloned EspD strain UMD870(pLCL123) (c), double EspD coiled-coil mutant strain UMD870(pICC73) (d), and triple EspD coiled-coil mutant strain UMD870(pICC74) (e). The coiled-coil mutants expressed EspA filaments (d, e), but whereas the double mutant produced a positive FAS reaction (actin accumulation at sites of bacterial attachment) (d), the triple mutant produced a barely detectable FAS reaction (e). Note that the espD deletion mutant produced barely detectable EspA filaments (b) and that EspA filaments expressed from strains harboring plasmid pLCL123 (c to e) are of the same length. Bars, 5 μm (column 1) and 20 μm (columns 2 and 3).

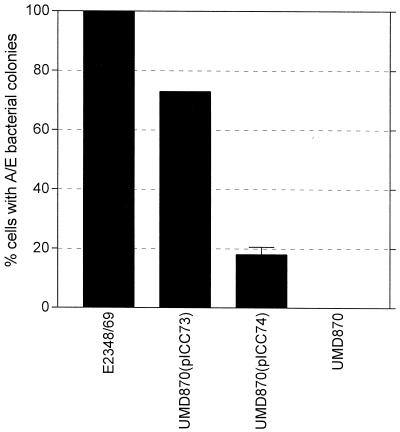

FIG. 5.

Adhesion of A/E bacteria to HEp-2 cells. Whereas all the strains adhered to HEp-2 cells, there were differences in their ability to produce A/E lesions. A/E adherence of the double coiled-coil mutant [UMD870(pICC73)] was comparable to that of wild-type E2348/69, whereas A/E adherence of the triple mutant [UMD870(pICC74)] was significantly attenuated. The EspD deletion mutant did not produce A/E lesions. Error bars represent standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Previous studies have shown that proteins belonging to the EspD family (YopB, IpaB) are part of the type III secretion apparatus and are involved in formation of a translocation pore in the host cell membrane (2). Recently, an EPEC infection model was developed using monolayers of RBCs, and it showed that EPEC-induced hemolysis is not contact mediated but is associated with EspA filament-mediated bacterial attachment and insertion of EspD into the RBC membrane (35). Accordingly, we tested the effect of the coiled-coil EspD mutations on the hemolytic activity of EPEC; whereas strains UMD870(pLCL123) and UMD870(pICC73) produced levels of hemolysis comparable to wild-type E2348/69, strain UMD870(pICC74) was ∼4-fold less hemolytic (Fig. 6). Immunofluorescent staining of EspA confirmed that wild-type E2348/69, cloned espD [strain UMD870(pLCL123)], and the coiled-coil mutant strains UMD870(pICC73) and UMD870(pICC74) expressed EspA filaments which promoted attachment of bacteria to the RBC membrane. However, as was the case with HEp-2 cells, the triple coiled-coil mutant strain UMD870(pICC74) was significantly less adherent than the other strains (Fig. 7). The espD deletion mutant strain UMD870, which produces vestigial EspA filaments, did not adhere to RBCs and was nonhemolytic (Fig. 5 and 6).

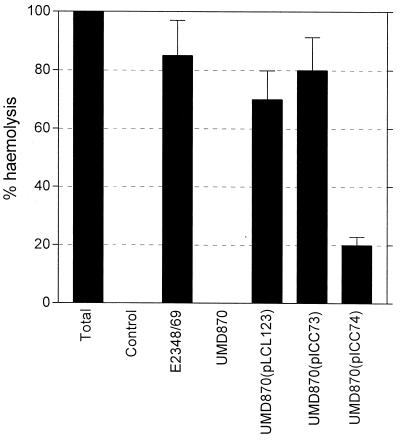

FIG. 6.

Hemolytic activity of the EspD coiled-coil mutants. Hemolytic activity of the double EspD coiled-coil mutant UMD870(pICC73) was comparable to that of wild-type E2348/69 and cloned EspD strain UMD870(pLCL123), but the triple mutant UMD870(pICC74) was significantly attenuated in hemolytic activity. The EspD deletion mutant was nonhemolytic. Error bars represent standard deviations of three independent experiments.

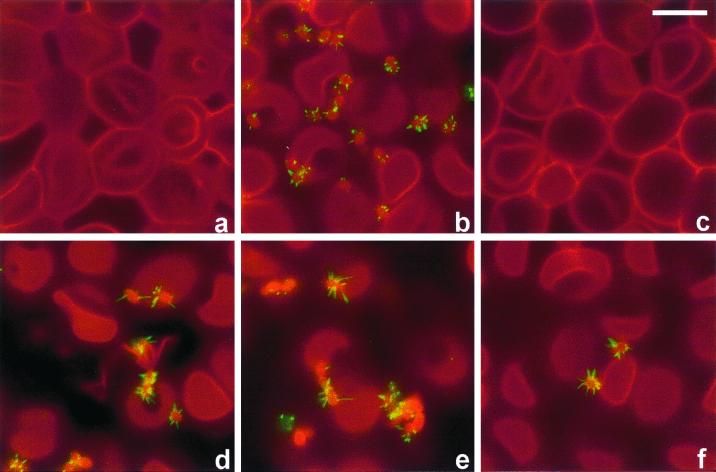

FIG. 7.

EspD coiled-coil mutant interaction with RBCs. Following infection, EspA filaments and the RBC membrane were visualized by fluorescence staining with EspA antiserum (green) and wheat germ agglutinin (red), respectively. Wild-type E2348/69 (b), cloned EspD strain UMD870(pLCL123) (d), and the double and triple coiled-coil mutant strains UMD870(pICC73) (e) and UMD870(pICC74) (f) produced EspA filaments which promoted binding of bacteria to the red cell membrane, although the level of binding of the triple mutant was significantly reduced (f). The EspD deletion mutant did not produce EspA filaments and was nonadherent (c). An uninfected RBC monolayer is shown in panel a. Bar, 5 μm.

Localization of EspD.

We used fluorescence and gold-labelling electron microscopy to try to localize EspD in the membrane of infected HEp-2 and RBCs by using monoclonal anti-EspD antibodies. Surprisingly, fluorescence staining of HEp-2 cells infected with E2348/69 revealed large EspD staining structures that were closely associated with microcolonies of cell-adherent bacteria, and these EspD aggregates generally appeared to have a filamentous structure (Fig. 8). No staining was observed with the EspD deletion mutant strain UMD870. The presence of such extracellular EspD aggregates made it impossible to define specific membrane-associated EspD.

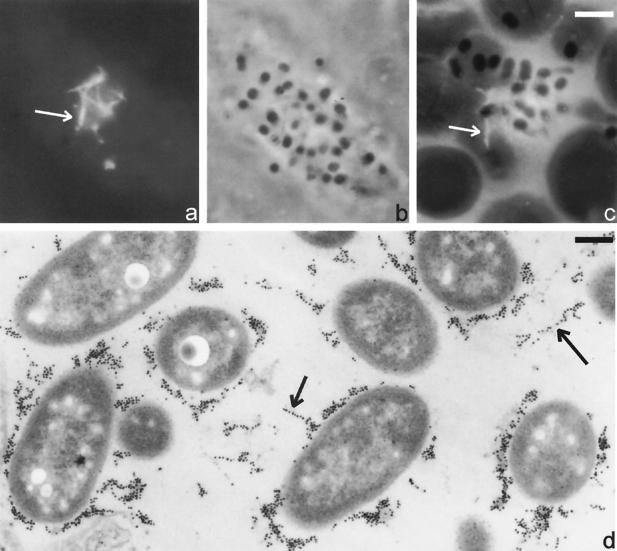

FIG. 8.

Localization of EspD, as shown by Immunofluorescence (a), a corresponding phase-contrast micrograph (b), and a combined fluorescence and phase micrograph (c) showing EspD localization in HEp-2 cells (a and c) and red blood cells (d) infected with wild-type E2348/69. The EspD antibody stained large protein aggregates (a and c, arrows) that were closely associated with adherent bacteria (b and c). A fibrillar arrangement of secreted EspD was indicated both by immunofluorescence (a and c) and immunogold EspD staining (d). Bars, 5 μm (a to c) and 0.2 μm (d).

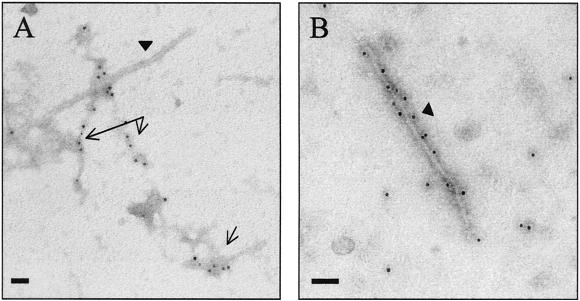

In Yersinia, YopB has been reported to form large aggregates in culture supernatants (29). Due to its similarity to YopB (21% identity) and to the presence of large EspD aggregates on the surface of infected cells, we investigated if EspD formed similar structures in culture supernatants. Filtered EPEC culture supernatants, grown under conditions that favored Esp protein secretion, were subjected to high-speed centrifugation and the pellets were examined by immunogold-labeling electron microscopy and negative staining. These experiments showed that monoclonal EspD antibodies stained large protein aggregates (Fig. 9A). Occasionally, EspA filaments were seen in the vicinity of the EspD aggregates (Fig. 9A and B). No EspD structures were observed in supernatants of the EPEC espD null mutant strain UMD870, but they were detected in supernatants of the EPEC espA null mutant strain UMD872 (data not shown).

FIG. 9.

(A) Immunogold labeling of negatively stained EPEC culture supernatants, revealing the presence of EspD aggregates (arrows). (B) Occasionally, the EspD aggregates were seen in the vicinity of EspA filaments, which were stained in independent experiments with anti-EspA monoclonal antibodies (arrowhead). Bar, 50 nm.

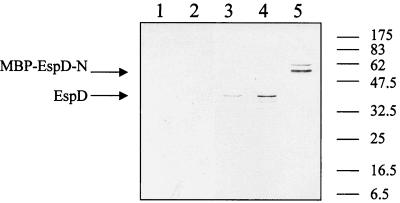

Soluble EspD binds MBP-EspD columns.

Prompted by the presence of EspD-associated protein aggregates in culture supernatants, we investigated the ability of EspD to bind other secreted proteins. Initial attempts to express whole EspD using a number of expression vectors together with ion-exchange or affinity chromatography were largely unsuccessful; EspD repeatedly localized to the insoluble fraction (data not shown). We hypothesized that whole EspD polypeptide forms insoluble inclusion bodies due to its two putative centrally located, hydrophobic, membrane-spanning domains (Fig. 2). Taking this into account, we produced two separate MBP fusion proteins comprising the N-terminal (amino acids 1 to 177) (generating plasmid pICC76) and C-terminal (amino acids 250 to 380) (generating plasmid pICC77) portions of EspD and, in contrast to full-length EspD, both MBP-EspD-N and MBP-EspD-C were soluble. Columns containing MPB-EspD-N, MBP-EspD-C, or MBP were overlaid with 25 ml of filtered culture supernatants derived from EPEC E2348/69 grown in DMEM. Following elution with 10 mM maltose, 1-ml fractions were collected and subjected to Western blotting with antibodies to MBP, EspA, EspB, EspD, and Tir. Of the different EPEC secreted proteins, only EspD coeluted with MBP-EspD-C (Fig. 10); no Esps were eluted with MBP-EspD-N or MBP (data not shown), a result which suggests that the carboxy-terminal region of the polypeptide is involved in EspD-EspD protein interaction.

FIG. 10.

Detection of coelution of MBP-EspD-C and secreted EspD by immunoblotting with anti-EspD antiserum. Lane 1, MBP plus supernatant (first eluted fraction); lane 2, MBP plus supernatant (second eluted fraction); lane 3, MBP-EspD-C plus supernatant (fraction 1); lane 4, MBP-EspD-C plus supernatant (fraction 2); lane 5, MBP-EspD-N plus supernatant (fraction 2). The monoclonal EspD antibodies, which were reactive with an amino-terminal EspD epitope, detected coelution of EspD with MBP-EspD-C and the MBP-EspD-N fusion protein.

DISCUSSION

Although the structural basis for protein translocation has yet to be fully elucidated for any type III secretion system, integrating data from studies of different type III secretion systems suggests the presence of channel-forming proteins of bacterial origin in both the bacterial outer membrane and in the plasma membrane of the infected host cells and a filamentous or needle structure connecting bacterial and host cell membranes. Interactions between various type III secreted proteins (e.g., EspA-EspA, EspA-EspB, YopB-YopD, YopN-TyeA, and IpaB-IpaC) have been described (5, 10, 12, 14, 28). In this study, we investigated EspD-EspD protein interactions using both the yeast two-hybrid system and column overlays. A strong EspD-EspD protein interaction was detected in the yeast two-hybrid system, but attempts to confirm this observation using purified, recombinant, EspD polypeptides were unsuccessful because they resulted in an insoluble protein. Consequently, we expressed and purified MBP fusions of truncated EspD fragments corresponding to the amino and carboxy termini and examined their ability to bind native secreted proteins; EspD copurified only with MBP-EspD-C, indicating that the specific EspD-EspD protein interaction is mediated by the carboxy-terminal region of the polypeptide. Additionally, Western blots developed with monoclonal antibodies against EspB, Tir, and EspA indicated that neither the N-terminal nor C-terminal regions of EspD interact with these other EPEC secreted proteins in this system.

Coiled-coil domains are found in high frequency amongst structural and effector proteins of type III secretion systems (33). For example, when we searched all the proteins encoded within the Yersinia pestis genome, only 1.8% of the open reading frames were found to contain a strongly predicted coiled-coil motif compared with ∼20% within the type III secretion system proteins, an observation which suggests that coiled-coil interactions play an important role in assembly of the type III protein translocation apparatus. Within EPEC type III secreted proteins, it was recently demonstrated that EspA-EspA interaction, leading to EspA filament assembly, involved interaction between the polypeptide coiled-coil domains (5). Yersinia YopN-TyeA secreted protein interaction was also recently reported to involve coiled-coil interactions (14).

In common with a number of other type III secreted proteins, analysis of the carboxy-terminal region of EspD revealed the presence of a characteristic coiled-coil motif (33, 38). In order to investigate any contribution of the EspD coiled-coil domain to the biological activity of the polypeptide, we introduced consecutive nonconservative substitutions into the cloned espD gene at positions predicted to be important for the coiled-coil conformation and examined the consequence of mutagenesis on the ability of the strain to elaborate EspA filaments and induce A/E lesions. Whereas no detectable effect of single or double amino acid substitutions was observed, changing three amino acids in the coiled-coil region resulted in attenuation of A/E lesion formation, despite the fact that the strain produced EspA filaments indistinguishable from the parent wild-type strain. Thus, it would appear that the carboxy-terminal coiled-coil region of EspD is not involved in EspD-EspA interaction and biogenesis of EspA filaments.

Similar to Yersinia YopB (29), EspD was observed to form large protein aggregates in culture supernatants and within bacterial microcolonies on infecting HEp-2 cells. Such aggregates were not present in secreted proteins of strain UMD870 but were still observed in the absence of EspA (strain UMD872). The molecular basis for the formation of EspD aggregate structures most likely reflects intermolecular interactions between EspD polypeptides or is due to the hydrophobic nature of the predicated membrane-spanning domains of the polypeptide (33, 38); the fibrillar appearance observed by fluorescence and gold-label electron microscopy suggests a possible linear or helical arrangement of EspD molecules in the aggregates.

EspD is homologous to YopB (33), which, together with YopD, is thought to form a pore in the host cell membrane (2). If EspD has a similar function, it is likely that EspD-EspD interactions would be required for pore formation in the plasma membrane of infected cells, either alone or possibly in cooperation with EspB; in this respect, the insoluble EspD aggregates detected in culture supernatants and in infected cells may represent a nonphysiological consequence of EspD secretion without insertion into the host cell membrane.

Pore formation in host cells by Yersinia and Shigella species has been correlated with their ability to cause contact-dependent hemolysis of RBCs (1, 10). A recent report showed that EPEC can also induce contact-dependent hemolysis (39), although it has now been shown (35) that centrifugation of bacteria and RBCs, a step designed to reduce the distance between bacterial and red cell membranes below a critical threshold, is not required in the case of EPEC-induced hemolysis because long EspA filaments connect bacteria to the host cell during protein translocation (23). Our laboratory has also examined which EPEC proteins became associated with the RBC membrane during hemolysis and showed that EspD was the only bacterial protein associated with membranes following infection with wild-type strains, a result which suggests that EspD plays a dominant role in pore formation (35). In this study, we investigated this issue using coiled-coil espD mutants. In correlation with a positive FAS test on HEp-2 cells, we found that single and double amino acid substitutions had no effect on EPEC-induced hemolysis, whereas the triple amino acid substitution resulted in a strain significantly attenuated in A/E lesion formation, in binding to RBC monolayers, and in hemolytic activity. To date, either by immunofluorescence microscopy or immunoprecipitation of EspA filaments, EspD has not been found to be directly associated with EspA filaments. Nevertheless, based on our observations and despite the fact that no physical association has been detected thus far between EspA and EspD, we speculate that EspD could be a minor component of the EspA filament. This is not without precedent, as EspD appears to be intimately involved in EspA filament stability and/or elongation, which in the flagella system is a function of the filament capping protein (13). In summary, we have demonstrated that EspD has multiple functions; it influences the length of the EspA filament, it is involved in adhesion during the early stages of the infection, and it is involved in the formation of the translocation pore once cell contact has been established. The triple coiled-coil mutation separates, for the first time, the length-controlling function of EspD from its binding and translocation activities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S. J. Daniell and R. M. Delahay contributed equally to this paper.

We thank Ian Connerton from the University of Nottingham for his help with the yeast two-hybrid system and Michael Donnenberg for bacterial strains and plasmids.

E.L.H. is the recipient of a Royal Society/NHMRC Howard Florey Fellowship. This work was supported by grants from the Wellcome and Leverhulme Trusts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blocker A, Gounon P, Larquet E, Niebuhr K, Cabiaux V, Parsot C, Sansonetti P. The tripartite type III secreton of Shigella flexneri inserts IpaB and IpaC into host membranes. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:683–693. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornelis G, Van Gijsegem F. Assembly and function of type III secretory systems. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:735–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cravioto A, Gross R J, Scotland S M, Rowe B. An adhesive factor found in strains of Escherichia coli belonging to the traditional infantile enteropathogenic serogroups. Curr Microbiol. 1979;3:95–99. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deibel C, Kramer S, Chakraborty T, Ebel F. EspE, a novel secreted protein of attaching and effacing bacteria, is directly translocated into infected host cells, where it appears as a tyrosine-phosphorylated 90 kDa protein. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:463–474. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delahay R M, Knutton S, Shaw R K, Hartland E L, Pallen M J, Frankel G. The coiled-coil domain of EspA is essential for the assembly of the type III secretion translocon on the surface of enteropathogenic E. coli. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35969–35974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnenberg M S, Yu J, Kaper J B. A second chromosomal gene necessary for intimate attachment of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4670–4680. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4670-4680.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebel F, Podzadel T, Rohde M, Kresse A U, Kramer S, Deibel C, Guzman C A, Chakraborty T. Initial binding of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli to host cells and subsequent induction of actin rearrangements depend on filamentous EspA-containing surface appendages. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:147–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finlay B B, Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:136–169. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.136-169.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francis M S, Wolf-Watz H. YopD of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is translocated into the cytosol of HeLa epithelial cells: evidence of a structural domain necessary for translocation. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:799–813. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakansson S, Bergman T, Vanooteghem J C, Cornelis G, Wolf-Watz H. YopB and YopD constitute a novel class of Yersinia Yop proteins. Infect Immun. 1993;61:71–80. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.71-80.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartland E L, Batchelor M, Delahay R M, Hale C, Matthews S, Dougan G, Knutton S, Connerton I, Frankel G. Binding of intimin from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to Tir and to host cells. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:151–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartland E L, Daniell S J, Delahay R M, Neves B C, Wallis T, Shaw R K, Hale C, Knutton S, Frankel G. The type III protein translocation system of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli involves EspA-EspB protein interactions. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1483–1492. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeda T, Asakura S, Kamiya R. “Cap” on the tip of Salmonella flagella. J Mol Biol. 1985;184:735–737. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iriarte M, Sory M P, Boland A, Boyd A P, Mills S D, Lambermont I, Cornelis G R. TyeA, a protein involved in control of Yop release and in translocation of Yersinia Yop effectors. EMBO J. 1998;17:1907–1918. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James P, Halladay J, Craig E A. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 1996;144:1425–1436. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarvis K G, Giron J A, Jerse A E, McDaniel T K, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli contains a putative type III secretion system necessary for the export of proteins involved in attaching and effacing lesion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7996–8000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarvis K G, Kaper J B. Secretion of extracellular proteins by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli via a putative type III secretion system. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4826–4829. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4826-4829.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jerse A E, Yu J, Tall B D, Kaper J B. A genetic locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli necessary for the production of attaching and effacing lesions on tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7839–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly G, Prasannan S, Daniell S, Fleming K, Frankel G, Dougan G, Connerton I, Matthews S. Structure of the cell-adhesion fragment of intimin from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:313–318. doi: 10.1038/7545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenny B, DeVinney R, Stein M, Reinscheid D J, Frey E A, Finlay B B. Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell. 1997;91:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenny B, Lai L C, Finlay B B, Donnenberg M S. EspA, a protein secreted by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, is required to induce signals in epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knutton S, Baldwin T, Williams P H, McNeish A S. Actin accumulation at sites of bacterial adhesion to tissue culture cells: basis of a new diagnostic test for enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1290–1298. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1290-1298.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knutton S, Rosenshine I, Pallen M J, Nisan I, Neves B C, Bain C, Wolff C, Dougan G, Frankel G. A novel EspA-associated surface organelle of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli involved in protein translocation into epithelial cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:2166–2176. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai L C, Wainwright L A, Stone K D, Donnenberg M S. A third secreted protein that is encoded by the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli pathogenicity island is required for transduction of signals and for attaching and effacing activities in host cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2211–2217. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2211-2217.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lupas A. Coiled coils: new structures and new functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:375–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDaniel T K, Kaper J B. A cloned pathogenicity island from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli confers the attaching and effacing phenotype on E. coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:399–407. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2311591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menard R, Prevost M C, Gounon P, Sansonetti P, Dehio C. The secreted Ipa complex of Shigella flexneri promotes entry into mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1254–1258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michiels T, Wattiau P, Brasseur R, Ruysschaert J M, Cornelis G. Secretion of Yop proteins by Yersiniae. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2840–2849. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.2840-2849.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moon H W, Whipp S C, Argenzio R A, Levine M M, Giannella R A. Attaching and effacing activities of rabbit and human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pig and rabbit intestines. Infect Immun. 1983;41:1340–1351. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.1340-1351.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nataro J P, Kaper J B. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pallen M J, Dougan G, Frankel G. Coiled-coil domains in proteins secreted by type III secretion systems. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:423–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4901850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perna N T, Mayhew G F, Posfai G, Elliott S, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B, Blattner F R. Molecular evolution of a pathogenicity island from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3810–3817. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3810-3817.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaw R K, Daniell S, Ebel F, Frankel G, Knutton S. EspA filament-mediated protein translocation into red blood cells. Cell Microbiol. 2001;4:213–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor K A, Luther P W, Donnenberg M S. Expression of the EspB protein of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli within HeLa cells affects stress fibers and cellular morphology. Infect Immun. 1999;67:120–125. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.120-125.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ulshen M H, Rollo J L. Pathogenesis of Escherichia coli gastroenteritis in man—another mechanism. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:99–101. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198001103020207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wachter C, Beinke C, Mattes M, Schmidt M A. Insertion of EspD into epithelial target cell membranes by infecting enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1695–1707. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warawa J, Finlay B B, Kenny B. Type III secretion-dependent hemolytic activity of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5538–5540. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5538-5540.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolff C, Nisan I, Hanski E, Frankel G, Rosenshine I. Protein translocation into HeLa cells by infecting enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:143–155. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]