Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared monkeypox a “public health emergency of international concern” on 23 June 2022. However, there is a lack of data on monkeypox perceptions among medical workers. The purposes of this study were to evaluate perceptions, worries about monkeypox, attitudes towards monkeypox vaccination and their correlates among medical workers in China.

Methods

Data were collected from medical practitioners using an online survey questionnaire between September 1 and September 30, 2022 in China. All the subjects completed an online questionnaire including general characteristics, perceptions/knowledge/worries about monkeypox, and attitudes towards monkeypox vaccination. Logistic regression was employed to examine the correlates of perceptions, worries about monkeypox, and attitudes toward monkeypox vaccination.

Results

In total, this study sample included 639 medical workers. The mean age was 37.9 ± 9.4 years old. Approximately 71.8% of individuals reported perceptions of monkeypox, 56.7% worried about monkeypox, and 64.9% supported the promotion of monkeypox vaccination. Medical workers who were older than 50 years (aOR 3.73, 95%CI 1.01–13.85), worked in the Infectious Diseases/Dermatology/Venereal Diseases departments (3.09, 1.61–5.91), and provided correct answer to monkeypox transmission route (10.19, 5.42–19.17) were more likely to know about monkeypox/monkeypox virus before investigation. 30.7% reported that they were more worried about monkeypox than the coronavirus (COVID-19). Participants reported that the key population most in need of monkeypox vaccination were health practitioners (78.2%) and people with immunodeficiency (74.3%), followed by children (65.4%) and older adults (63.2%).

Conclusion

Awareness of monkeypox was high and attitude towards the promotion of monkeypox vaccination was positive among medical staff in China. Further targeted dissemination of monkeypox common knowledge among health care providers might improve their precaution measures and improve the promotion of monkeypox vaccination among key populations.

Keywords: Monkeypox, Perceptions, Vaccination, Worries, Precaution

1. Introduction

Monkeypox virus (MPXV), first identified in humans in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire), is a zoonotic virus related to the virus that causes smallpox [1], [2]. From 1 January 2022–13 September 2022, 102 countries across all 6 WHO regions have reported 58285 laboratory-confirmed cases, including 22 deaths, to WHO [3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared monkeypox a “public health emergency of international concern” on 23 June 2022 [4], [5]. Human-to-human transmission can occur through close contact with skin lesions, respiratory secretions, or recently contaminated objects of an infected person [6] and literature reported [7] that monkeypox outbreaks predominantly affect men who have sex with men. On September 6, 2022, Hong Kong reported its first case of monkeypox in a 30-year-old man who arrived from the Philippines after traveling in the United States and Canada, and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region's government will raise the response level for the monkeypox outbreak to an “alert” level [8]. The first imported case of monkeypox in Hong Kong is also an alarm for mainland China. 10 days later, the first imported case of monkeypox in mainland China is reported by “China CDC Weekly” [9]. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the monkeypox epidemic and prevent its spread in China.

Previous studies have shown that the degree of concerns and worries about the evolved coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been reflected through the different variants (such as the Omicron and Delta) [10], [11]. The emergence of a new virus (MPXV) at this time may further complicate the level of public concern and the strain on healthcare systems. Smallpox virus is eradicated globally in 1980 through mass vaccination, and the partial loss of protective activity of the smallpox vaccination due to the cessation of mandatory vaccination may have led to an increase in cases of MPXV [12]. Currently, there are two possible vaccinations for MPXV infection [13], but it is unclear what attitudes people have regarding monkeypox vaccination promotion.

Medical workers’ knowledge of monkeypox precautions and early screening and detection of monkeypox patients are important for controlling transmission. A WHO report shows that one of the challenges in preventing monkeypox is the lack of knowledge about monkeypox. [14] It is critical to improve the perceptions of monkeypox among the public, especially among healthcare providers. The awareness and basic knowledge of monkeypox among medical staff can provide support for the detection of patients with monkeypox and improve their preventive measures. However, there is a lack of data on monkeypox perceptions among medical workers in China, and medical staff may be at risk of receiving patients with monkeypox and occupational exposure. The purposes of this study were to explore the perceptions, worries about monkeypox, attitudes towards monkeypox vaccination and their correlates among medical workers in China.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

This study was based on nationwide a cross-sectional survey using an online survey questionnaire between September 1 and September 30, 2022 in China. The subjects came from more than 80 cities/regions in China, and the research team members published and publicized them on their social media accounts (WeChat) online. WeChat is a multi-purpose social media and messaging platform in China with over 1 billion monthly active users. The participants’ inclusion criteria for the survey were 18 years or older, healthcare workers/medical practitioners, and voluntary participation. Participants read the overview of the study online, and clicked “agree” to participate in the questionnaire. In this study, medical workers included doctors, nurses and medical technicians from more than 30 departments in tertiary hospitals and secondary hospitals, as well as public health practitioners from public health service institutions and community health service centers. These healthcare workers are involved in the diagnosis, treatment, and direct management of suspected or confirmed monkeypox infected people and are at potential risk of contracting the monkeypox virus [15].

2.2. General questions

The analysis variables of the general questionnaire included social demographic characteristics such as age, gender, marital status, educational level, and monthly income; health characteristics such as ever been diagnosed with chronic diseases, or depressive symptoms; and career information such as professional title, working years, type of medical institution and hospital department. We classified the age group as 18–30, 31–40, 41–50, and> 50 years old. Marital status was divided into married, and unmarried. Level of education was categorized into master degree or higher, undergraduate, junior college or lower. The professional title was categorized as junior title, intermediate title, and senior title. Working years were divided into 1–5, 5–10, and 10 above. Type of medical institution including tertiary hospitals, secondary hospitals, community health service centers, and public health institutions. Participants were asked to report whether they had ever been diagnosed with chronic diseases, including hypertension, chronic respiratory disease, chronic pain, hyperuricemia, hyperlipidemia, immunodeficiency disease, and cancer. The depressive symptom was assessed using Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2), including 2 items, the total scores ranged from 0 to 6, and depression was defined as a score≥ 3 [16].

2.3. Perceptions of monkeypox

In this study, the perceptions of monkeypox were measured by asking the question that “Did you know about monkeypox/MPXV before this survey.” Participants who answered “Yes, I have some knowledge about monkeypox/MPXV before investigating.” were considered to have perceptions of monkeypox. On the contrary, participants who answered “No, I do not know about monkeypox/MPXV before investigating.” were regarded to lack perceptions of monkeypox. For participants who with perceptions of monkeypox, we further asked participants how often they recently paid attention to information about the monkeypox epidemic (frequent attention, occasional attention, little attention, and never attention) and what kind of channel they paid attention to monkeypox.

2.4. Knowledge of monkeypox

Knowledge of monkeypox included source of monkeypox infection, monkeypox transmission route, and monkeypox common knowledge. The common knowledge of monkeypox included 7 items: (1) Monkeypox is a dangerous and rapidly spreading disease; (2) Monkeypox is a zoonotic disease; (3) Respiratory and contact prophylaxis should be used to prevent monkeypox; (4) Monkeypox can spread before symptoms appear, especially skin blisters; (5) The smallpox vaccination (given before 1980, also known as “cowpox”) is effective against monkeypox; (6) The varicella vaccination is effective against monkeypox; (7) There is a definite treatment or specific medicine for monkeypox. Participants were asked to judge whether each item was true/false/don't know. The answer “don't know” was considered an incorrect answer. A correct answer to 4 or more out of 7 questions was considered a high level of monkeypox common knowledge.

2.5. Attitudes toward monkeypox vaccination

“At this stage, do you support the promotion of monkeypox vaccination?” using a five-point Likert scale [17] ranging from 1 (strongly support) to 5 (strongly not support), were used to evaluate attitude towards monkeypox vaccination promotion. In this study, support for the promotion of the monkeypox vaccination was re-categorized as support (1−2) and nonsupport (3−5). Further, we asked participants which groups of people they thought needed to be vaccinated against monkeypox.

2.6. Worries about monkeypox

Worries about monkeypox were assessed through questions: “Are you worried about the monkeypox pandemic?” and “Are you more worried about monkeypox than COVID-19?” If answered yes, we further asked the reason why there was concern about the monkeypox pandemic. In addition, we asked the questions that “Do you think that monkeypox will be outbreaks in China?” and “What are the reasons that monkeypox will be outbreaks in China/will not be outbreaks in China?”.

2.7. Precaution of monkeypox

The precaution against monkeypox among medical workers was assessed by asking “How do you think you should avoid infection when you are receiving monkeypox patients?” Participants were considered to be aware of monkeypox precautions if they chose two or more of the answers to wear masks, wear gloves, disinfect their hands, or disinfect the environment. If participants selected “refused treatment monkeypox patient” in the response, they were further asked about the reason for the refusal.

2.8. Data analysis

Study population characteristics were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were used to describe continuous variables. Frequency and percentage were presented for categorical variables. The multivariate logistic regression model was run to analyze the correlates of perceptions, worries about monkeypox, and attitudes towards monkeypox vaccination among medical workers. Enter method was used to include all possible influencing factors as independent variables in the multivariate logistic regression analysis model. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. All analyses were conducted using the statistical analysis program SPSS version 26.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The statistical significance was set as P < 0.05.

3. Results

In total, this study sample included 639 medical workers. Characteristics of medical workers were presented in Table 1. The mean age was 37.9 ± 9.4 years, 208 (32.6%) were males and 431 (67.4%) were females. A large proportion of participants were married (70.3%) and educated in undergraduate or high (87.5%). Among the participants, 57.3% worked for more than 10 years, and nearly half (49%) of them came from tertiary hospitals. In addition, we recruited 113 medical workers from the Infectious Diseases/Dermatology/Venereal Diseases departments, who were most likely to be exposed to patients with monkeypox. Approximately 459 (71.8%) of individuals reported perceptions of monkeypox, 362 (56.7%) worried about monkeypox, and 415 (64.9%) supported the promotion of monkeypox vaccination.

Table 1.

Characteristics of medical workers (N = 639).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 37.91 (9.40) |

| Age group, years | |

| 18–30 | 168 (26.3) |

| 31–40 | 229 (35.8) |

| 41–50 | 172 (26.9) |

| > 50 | 70 (11.0) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 208 (32.6) |

| Female | 431(67.4) |

| Marital status | |

| Unmarried | 190 (29.7) |

| Married | 449 (70.3) |

| Educational level | |

| Master degree or higher | 220 (34.4) |

| Undergraduate | 339 (53.1) |

| Junior college or below | 80 (12.5) |

| Monthly income (RMB) | |

| <6000 | 207 (32.4) |

| 6000–9999 | 196 (30.7) |

| 10,000–19999 | 168 (26.3) |

| > 20,000 | 68 (10.6) |

| Chronic diseasesa | |

| No | 494 (77.3) |

| Yes | 145 (22.7) |

| Depression (PHQ-2) | |

| No | 571 (89.4) |

| Yes | 68 (10.6) |

| Professional title | |

| Junior title | 244 (38.2) |

| Intermediate title | 206 (32.2) |

| Senior title | 189 (29.6) |

| Working years | |

| 1–5 | 159 (24.9) |

| 5–10 | 114 (17.8) |

| > 10 | 366(57.3) |

| Type of medical institution | |

| Public health institutions | 150 (23.5) |

| Tertiary hospitals | 313 (49.0) |

| Secondary hospitals | 113 (17.7) |

| Community health service centers | 63 (9.9) |

| Hospital department | |

| Infectious Diseases/Dermatology/Venereal Diseases | 113 (17.7) |

| Other departments | 526 (83.3) |

| Awareness of monkeypox | |

| No | 180 (28.2) |

| Yes | 459 (71.8) |

| Worry about monkeypox | |

| No | 277 (43.3) |

| Yes | 362 (56.7) |

| Support monkeypox vaccination | |

| No | 224 (35.1) |

| Yes | 415 (64.9) |

PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Chronic diseases include hypertension, chronic respiratory disease, chronic pain, hyperuricemia, hyperlipidemia, immunodeficiency disease, and cancer.

Knowledge of monkeypox among medical workers with perceptions of monkeypox was presented in Table 2. Among medical workers with perceptions of monkeypox (n = 459), 91.1% had a high level of monkeypox common knowledge and 94.8% reported awareness of monkeypox precaution. The frequencies of concern about monkeypox were frequent attention (108/459), occasional attention (279/459), little attention (64/459), and never attention (8/459), respectively. In monkeypox precaution, 54 healthcare workers chose to "reject" patients with monkeypox, and the reasons included fear of infection/occupational exposure (42/54); ignorance of the MPXV and inability to help patients (37/54); people with monkeypox are promiscuous (17/54); and hospital rules not to admit patients with monkeypox (17/54).

Table 2.

Knowledge of monkeypox among medical workers with perceptions of monkeypox (N = 459).

| Monkeypox knowledge | Perceptions of monkeypox, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Source of monkeypox infectiona | |

| Wrong | 61 (13.3) |

| Correct | 398 (86.7) |

| Monkeypox transmission routeb | |

| Wrong | 18 (3.9) |

| Correct | 441 (96.1) |

| Monkeypox common knowledgec | |

| Low level | 41 (8.9) |

| High level | 418 (91.1) |

| Awareness of monkeypox precaution | |

| No | 24 (5.2) |

| Yes | 435 (94.8) |

Source of monkeypox infection include animals infected with monkeypox and people infected with monkeypox.

Monkeypox transmission route include droplet transmission, blood and body fluids transmission, and contact transmission.

A correct answer to 4 or more out of 7 questions was considered a high level of monkeypox knowledge.

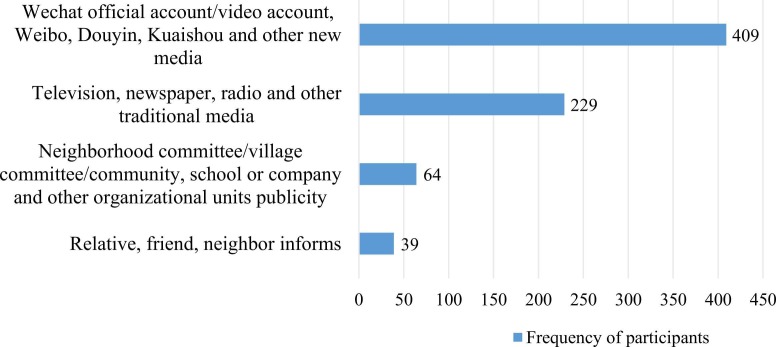

Fig. 1 showed the source of monkeypox information among medical workers who attention to monkeypox (n = 451). WeChat official account/video account, Weibo, Douyin, Kuaishou, and other new media were the main way for medical workers to get information about the monkeypox, followed by television, newspaper, radio, and other traditional media. Correlates of perceptions of monkeypox among medical workers were displayed in Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with perceptions of monkeypox. In social demographic and career information variables, age groups, type of medical institution, and hospital department were significantly associated with perceptions of monkeypox. Medical workers who were lder than 50 years (aOR = 3.73, 95%CI: 1.01–13.85), working in the Infectious Diseases/Dermatology/Venereal Diseases departments (3.09, 1.61–5.91) were more likely to know about monkeypox/MPXV before investigation. Compared with health service workers in public health institutions, medical workers in tertiary hospitals (0.27, 0.15–0.50) and secondary hospitals (0.27, 0.13–0.55) were negatively associated with perceptions of monkeypox. In monkeypox knowledge variables, provided the correct answer in the monkeypox transmission route was significantly associated with increased perceptions of monkeypox (10.19, 5.42–19.17).

Fig. 1.

Source of monkeypox information among medical workers who attention about monkeypox (n = 451).

Table 3.

Correlates of perceptions, worries about monkeypox, attitudes towards monkeypox vaccination among medical workers.

| Variables | Awareness of monkeypox | P-value | Worries about monkeypox | P-value | Support the promotion of monkeypox vaccination |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Age | ||||||

| 18–30 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 31–40 | 1.78 (0.76,4.19) | 0.184 | 1.91 (0.44,1.90) | 0.800 | 1.42 (0.67,3.04) | 0.363 |

| 41–50 | 2.38 (0.81,7.02) | 0.117 | 0.63 (0.25,1.55) | 0.311 | 1.15 (0.46,2.89) | 0.761 |

| > 50 | 3.74 (1.01,13.85) | 0.049 | 1.63 (0.59,4.54) | 0.350 | 2.63 (0.90,7.62) | 0.076 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 0.97 (0.61,1.54) | 0.890 | 1.48 (1.02,2.05) | 0.038 | 1.28 (0.88,1.86) | 0.206 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Unmarried | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Married | 1.18 (0.67,2.07) | 0.569 | 1.94 (1.21,3.13) | 0.002 | 1.23 (0.77,1.99) | 0.388 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Master degree or higher | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Undergraduate | 0.56 (0.25,1.26) | 0.157 | 2.32 (1.13,4.75) | 0.022 | 4.06 (1.85,8.90) | < 0.001 |

| Junior college or below | 0.81 (0.46,1.41) | 0.453 | 1.41 (0.91,2.18) | 0.127 | 1.59 (1.02,2.47) | 0.042 |

| Monthly income (RMB) | ||||||

| <6000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 6000–9999 | 0.85 (0.50,1.44) | 0.552 | 0.61 (0.39,0.96) | 0.033 | 1.06 (0.66,1.68) | 0.821 |

| 10,000–19999 | 1.61 (0.85,3.03) | 0.143 | 0.48 (0.29,0.80) | 0.004 | 0.92 (0.55,1.51) | 0.729 |

| > 20,000 | 0.92 (0.39,2.16) | 0.842 | 0.48 (0.24,0.96) | 0.037 | 0.80 (0.40,1.57) | 0.513 |

| Chronic diseases | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.01 (0.59,1.75) | 0.957 | 0.92 (0.40,0.95) | 0.027 | 1.01 (0.65,1.56) | 0.982 |

| Depression (PHQ-2) | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.74 (0.38,1.42) | 0.361 | 0.91 (0.52,1.60) | 0.748 | 0.75 (0.43,1.32) | 0.316 |

| Professional title | ||||||

| Junior title | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Intermediate title | 1.46 (0.74,2.85) | 0.275 | 1.06 (0.58,1.91) | 0.858 | 0.73 (0.39,1.36) | 0.317 |

| Senior title | 1.80 (0.80,4.07) | 0.157 | 0.91 (0.44,1.85) | 0.790 | 0.78 (0.37,1.64) | 0.504 |

| Working years | ||||||

| 1–5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 5–10 | 1.49 (0.69,3.25) | 0.315 | 0.71 (0.36,1.42) | 0.337 | 1.04 (0.52,2.09) | 0.904 |

| > 10 | 1.10 (0.43,2.81) | 0.843 | 0.73 (0.32,1.67) | 0.469 | 0.72 (0.32,1.63) | 0.426 |

| Type of medical institution | ||||||

| Public health institutions | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Tertiary hospitals | 0.27 (0.15,0.50) | < 0.001 | 0.50 (0.32,0.80) | 0.003 | 0.90 (0.57,1.43) | 0.657 |

| Secondary hospitals | 0.27 (0.13,0.55) | < 0.001 | 0.92 (0.51,1.64) | 0.763 | 1.23 (0.68,2.24) | 0.493 |

| Community health service centers | 0.56 (0.24,1.30) | 0.176 | 0.73 (0.37,1.44) | 0.359 | 0.64 (0.33,1.26) | 0.156 |

| Hospital department | ||||||

| Other department | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Infectious Diseases/Dermatology/ Venereal Diseases | 3.09 (1.61,5.91) | 0.001 | 1.40 (0.87,2.25) | 0.168 | 1.09 (0.67,1.77) | 0.739 |

| Source of monkeypox infectiona | ||||||

| Wrong | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Correct | 1.13 (0.64,2.00) | 0.678 | 1.13 (0.71,1.82) | 0.604 | 1.43 (0.89,2.30) | 0.139 |

| Monkeypox transmission routeb | ||||||

| Wrong | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Correct | 10.19 (5.42,19.17) | < 0.001 | 1.02 (0.59,1.79) | 0.935 | 0.55 (0.30,0.99) | 0.049 |

| Monkeypox common knowledgec | ||||||

| Low level | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| High level | 1.64 (0.90,3.01) | 0.109 | 1.93 (1.13,3.30) | 0.016 | 1.89 (1.11,3.23) | 0.019 |

| Awareness of monkeypox precaution | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.15 (0.50,2.63) | 0.745 | 0.82 (0.41,1.65) | 0.577 | 1.76 (0.89,3.50) | 0.104 |

PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; OR, odd ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

The multivariate logistic regression model was run to analyze the correlates factors of cognition, worries about monkeypox, attitudes towards monkeypox vaccination among medical workers.

Source of monkeypox infection include animals infected with monkeypox and people infected with monkeypox.

Monkeypox transmission route include droplet transmission, blood and body fluids transmission, and contact transmission.

A correct answer to 4 or more out of 7 questions was considered a high level of monkeypox knowledge.

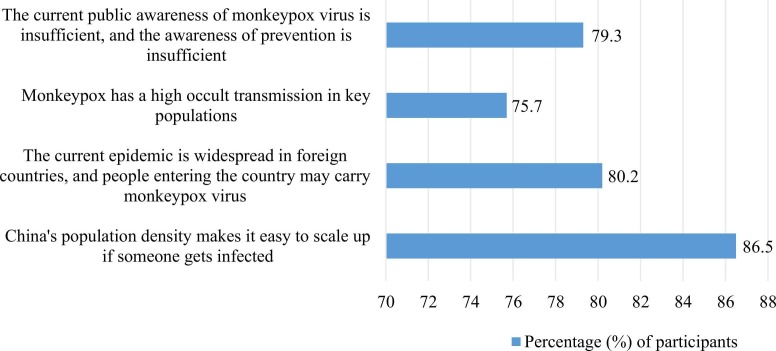

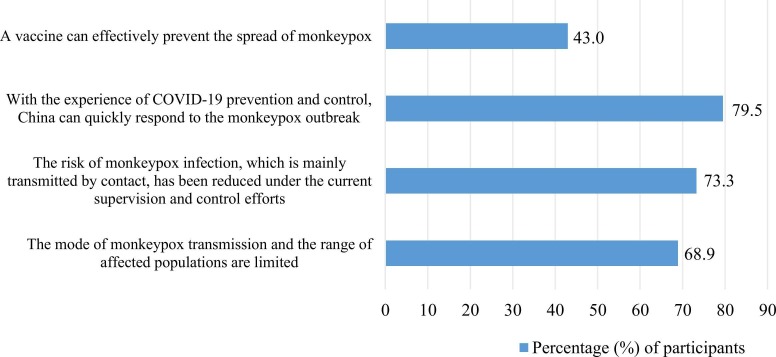

Among participants’ worries about monkeypox (n = 362), reasons for worries included “fear of me or my family members getting infected” (246/362), “fear of a worldwide pandemic” (314/362), “fear of an outbreak of monkeypox might lead to a nationwide quarantine” (292/362), and “fear of the suspension of international flights” (66/362). 30.7% of the subjects reported that they were more worried about monkeypox than COVID-19. Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 displayed the reasons for believing that monkeypox will be/will not be widespread in China among medical workers. And factors associated with worries about monkeypox were also shown in Table 3. Demographic variables such as gender, marital status, educational level, and monthly income were significantly associated with worries about monkeypox. Females (1.48, 1.02–2.05), married (1.94, 1.21–3.31) and undergraduate education (2.43, 1.13–4.75) were more likely to worry about the monkeypox pandemic. Compared with monthly income (RMB)< 6000, monthly income 6000–9999 (0.61, 0.39–0.96), monthly income 10,000–19,999 (0.48, 0.29–0.80), and monthly income> 20,000 (0.48, 0.24–0.96) were negatively associated with worries about monkeypox. Having a history of chronic diseases (0.92, 0.40–0.95) and working in a tertiary hospital (0.50, 0.32–0.80) were also negatively associated with monkeypox concern. A high level of monkeypox common knowledge was significantly associated with increased worries about monkeypox (1.93, 1.13–3.30).

Fig. 2.

Reasons why medical workers believe that monkeypox will be widespread in China (n = 111).

Fig. 3.

Reasons why medical workers believe that monkeypox will not be widespread in China (n = 528).

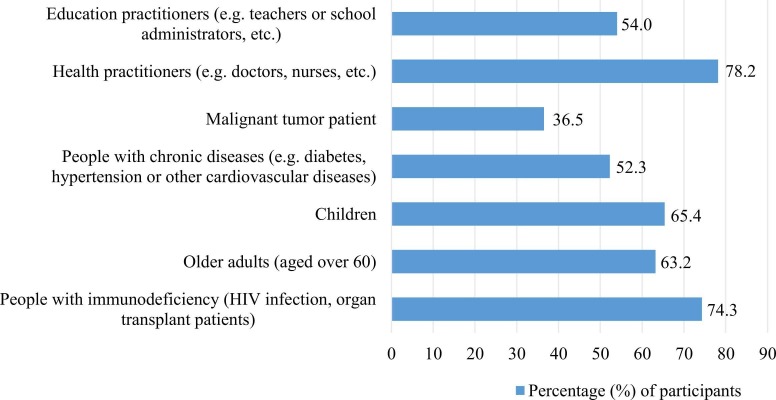

In terms of supporting the promotion of monkeypox vaccination (Table 3), educational level (Undergraduate: 4.06, 1.85–8.90; Junior college or below: 1.59, 1.02–2.47), the correct answer of monkeypox transmission route (0.55, 0.30–0.99), and high level of monkeypox common knowledge (1.89, 1.11–3.23) were significantly associated with supporting the promotion of monkeypox vaccination. Key populations who needed to be vaccinated against monkeypox were shown in Fig. 4. Participants reported that the groups most in need of monkeypox vaccination were health practitioners (78.2%) and people with immunodeficiency (74.3%), followed by children (65.4%) and older adults (63.2%).

Fig. 4.

Key populations that need to be vaccinated against monkeypox (n = 639).

4. Discussion

Our study found that healthcare workers in China had high awareness of monkeypox and positive attitudes toward monkeypox vaccination, and were concerned about the monkeypox epidemic. The results demonstrated that healthcare workers aged more than 50 years, working in the Infectious Diseases/Dermatology/Venereal Diseases departments, and giving correct answers on monkeypox transmission route were more likely to know about monkeypox/MPXV before investigation. Those who had lower educational levels and higher levels of monkeypox common knowledge were more likely to support the promotion of monkeypox vaccination. Individuals who were female, married, with undergraduate education and a high level of monkeypox common knowledge were more likely to worry about the monkeypox pandemic.

Compared to a few previous studies, our findings showed a higher perceptions of monkeypox among medical workers. The awareness rate of the high level of monkeypox common knowledge was 85.9% in this study. Whereas, a survey of medical staff in Italy found that 50.3% of doctors provided low scores on 24 items of monkeypox knowledge [18]. Another study in Indonesia reported that among 432 general practitioners, about 10.0% knew more than 80% of monkeypox knowledge in 21 items [19]. A cross-sectional study of 389 practicing medical doctors all over Bangladesh reported that only 119 (30.59%) participants had good knowledge regarding monkeypox [20]. Researchers in Jordan found that only 4 out of 11 monkeypox knowledge items had correct 50% answers among 606 health workers (about two-thirds doctors or nurses) [21], and less than half of 651 medical college students were aware of the monkeypox outbreak [22]. The possible explanation for these differences might be due to the different items used to measure common knowledge of monkeypox. In addition, mainstream medias in China reported the first imported monkeypox cases in Hong Kong and Chongqing during the study, it might improve medical workers’ perceptions of monkeypox. Meanwhile, compared with the survey of monkeypox knowledge among general population, the medical staff in this study also had a higher levels of monkeypox knowledge [23], [24], [25]. As monkeypox cases have continued to rise around the world, the nosocomial transmission of MXPV can occur, potentially leading to the infection of medical workers [26], [27]. Medical workers in the Infectious Diseases/Dermatology/Venereal Diseases departments, who were most likely to contact with and treat patients infected with monkeypox, were three times more likely to know about monkeypox than those in other departments in this study.

More than half of the participants reported worries about monkeypox, and higher levels of knowledge about monkeypox were associated with increased worries about monkeypox. The reason for this positive association might be that medical staff with high levels of monkeypox common knowledge were more aware of the severity of monkeypox global outbreak. The same phenomenon has been found in studies of other diseases [28], [29]. A recent cross-sectional study of 1546 participants found that more than 60% of participants were more worried about COVID-19 than monkeypox [12], similar to our findings (69.3%). And during the first month of the WHO monkeypox alert, approximately half of the of participants among 1130 healthcare workers were more concerned about Monkeypox than COVID-19, particularly regarding its possible progression into a new pandemic [30]. Besides, we found that gender, married status, educational level, and monthly income were associated with worries about monkeypox, which were partially consistent with demographic factors associated with COVID-19 concerns [31], [32]. People with higher incomes and higher educational levels might have better access to health care and therefore not be worried about monkeypox compared to people with lower incomes and lower educational levels. Interestingly, this study found that medical staff working in tertiary hospitals had lower perceptions and worries about monkeypox than those working in public health institutions. Compared to clinical medical professionals, public health practitioners in the disease control and prevention system may have better awareness of and are more concerned about monkeypox because they are routinely involved in infectious disease control.

There are few studies on medical staff’s attitudes towards vaccination against MPXV. WHO has recommended monkeypox immunization for healthcare workers at risk of occupational exposure [26]. Compared with a recent study on the willingness to receive monkeypox vaccine, the proportion of medical workers to support the promotion/encouragement of monkeypox vaccination was different due to the different question setting about attitudes towards vaccination [33]. The results of this study showed that educational level, the correct answer of monkeypox transmission route, and high level of monkeypox common knowledge were significantly associated with supporting the promotion of monkeypox vaccination. Similar to previous studies, participants with higher levels of education were more likely to experience vaccination hesitancy [34], [35]; participants with the junior college or below and undergraduate education were more supportive of monkeypox vaccination promotion than participants with a master degree or above in our study. We found that among respondents who correctly answered the route of monkeypox infection, a higher proportion believed that “monkeypox is mainly transmitted in special groups, and the mode of transmission and the range of affected population is limited” (59.7% vs 38.8%, P < 0.001), which could partially explain the negative association between the correct answer of monkeypox transmission route and monkeypox vaccination promotion.

This study has several limitations. First, our study was a cross-sectional survey, causality cannot be determined. Second, this study adopted convenience sampling, we might lose the information from participants who did not want to complete the questionnaire or did not know about monkeypox, and the popularization was limited. Finally, with the development of monkeypox epidemic, the perceptions and worries about monkeypox may change. Fourth, we did not assess the attitudes of medical staff towards monkeypox patients. Future studies should consider measures to raise awareness and reduce concerns about monkeypox among medical workers.

5. Conclusion

The perceptions of monkeypox was high and the attitude toward the promotion of monkeypox vaccination was positive among medical workers in China. Further targeted dissemination of monkeypox common knowledge among health care providers might improve their precaution measures and increase the promotion of monkeypox vaccination among the key population. At the same time, prompt psychological interventions are needed to reduce worries about monkeypox among healthcare workers.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration. Online informed consent will be obtained from all participants before any procedure of this Study. The Study (including online informed consent) was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health (Shenzhen), Sun Yat-sen University (approval number SYSU-PHS[2022]051).

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China International/Regional Research Collaboration Project (72061137001), Natural Science Foundation of China Excellent Young Scientists Fund (82022064), Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2020-JKCS-030), Natural Science Foundation of China Young Scientist Fund (81703278), the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (2018ZX10721102), the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (SZSM201811071), the High Level Project of Medicine in Longhua, Shenzhen (HLPM201907020105), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFC0840900), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission Basic Research Program (JCYJ20190807155409373), Special Support Plan for High-Level Talents of Guangdong Province (2019TQ05Y230), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (58000-31620005). All funding parties did not have any role in the study design or data explanation.

Authors’ contributions

HZ conceived the study. XP and BW conducted this study. XP, BW, and YL drafted the manuscript. YC, XW, LF, SY, QL, YL, BL, YF, and HZ revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank our partners, including Wuxi CDC and Chongqing CDC, Guangdong Provincial STD and AIDS Prevention Association, and Guangdong Youth Sexual Health Union. We thank the organizations and individuals who helped us recruit participants. We thank all participants who made this research possible.

Data Availability

The data collected in this study will not be publicly available. However, the corresponding author can be contacted for de-identified data upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Ladnyj I.D., Ziegler P., Kima E. A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu Territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;46(5):593–597. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinchliff S., Gott M. Challenging social myths and stereotypes of women and aging: Heterosexual women talk about sex. J Women Aging. 2008;20(1–2):65–81. doi: 10.1300/j074v20n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.2022 Monkeypox Outbreak: Global Trends. 〈https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/〉; 2022 [accesed 2022/9/26].

- 4.Multi-country monkeypox outbreak: Situation update. 〈https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON396〉; 2022 [Accesed 2022/9/26].

- 5.Multi-country monkeypox outbreak: Situation update. 〈https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON393〉; 2022 [Accesed 2022/9/26].

- 6.Monkeypox. 〈https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox〉; 2022 [Accesed 2022/9/26].

- 7.Inigo M.J., Gil M.E., Jimenez B.S., Martin M.F., Nieto J.A., Sanchez D.J., et al. Monkeypox outbreak predominantly affecting men who have sex with men, Madrid, Spain, 26 April to 16 June 2022. Eur Surveill. 2022;27(27) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.27.2200471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong Kong discovers first case of monkeypox | Article | China Daily. 〈https://www.chinadailyasia.com/article/289055〉; 2022 [Accesed 2022/9/26].

- 9.The First Imported Case of Monkeypox in the Mainland of China - Chongqing Municipality, China, September 16, 2022. 〈https://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/doi/10.46234/ccdcw2022.175〉; 2022 [Accesed 2022/9/26]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Aljamaan F., Alhaboob A., Saddik B., Bassrawi R., Assiri R., Saeed E., et al. In-Person schooling amidst children's COVID-19 vaccination: exploring parental perceptions just after omicron variant announcement. Vaccin (Basel) 2022;10(5) doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Koritala T., Alhumaid S., Barry M., Alshukairi A.N., Temsah M.H., et al. Implication of the emergence of the delta (B.1.617.2) variants on vaccine effectiveness. Infection. 2022;50(3):583–596. doi: 10.1007/s15010-022-01759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temsah M.H., Aljamaan F., Alenezi S., Alhasan K., Saddik B., Al-Barag A., et al. Monkeypox caused less worry than COVID-19 among the general population during the first month of the WHO Monkeypox alert: Experience from Saudi Arabia. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022;49 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costello V., Sowash M., Gaur A., Cardis M., Pasieka H., Wortmann G., et al. Imported Monkeypox from International Traveler, Maryland, USA, 2021. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28(5):1002–1005. doi: 10.3201/eid2805.220292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monkeypox - United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. 〈https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON381〉; 2022 [Accesed 2022/9/26].

- 15.Manirambona E., Felicilda L.J., Nduwimana C., Okesanya O.J., Mbonimpaye R., Musa S.S., et al. Healthcare workers and monkeypox: The case for risk mitigation. Int J Surg Open. 2023;50 doi: 10.1016/j.ijso.2022.100584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuler M., Strohmayer M., Muhlig S., Schwaighofer B., Wittmann M., Faller H., et al. Assessment of depression before and after inpatient rehabilitation in COPD patients: Psychometric properties of the German version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9/PHQ-2) J Affect Disord. 2018;232:268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humer E., Jesser A., Plener P.L., Probst T., Pieh C. Education level and COVID-19 vaccination willingness in adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01878-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricco M., Ferraro P., Camisa V., Satta E., Zaniboni A., Ranzieri S., et al. When a neglected tropical disease goes global: Knowledge, attitudes and practices of italian physicians towards monkeypox, preliminary results. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7(7) doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed7070135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harapan H., Setiawan A.M., Yufika A., Anwar S., Wahyuni S., Asrizal F.W., et al. Confidence in managing human monkeypox cases in Asia: a cross-sectional survey among general practitioners in Indonesia. Acta Trop. 2020;206 doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasan M., Hossain M.A., Chowdhury S., Das P., Jahan I., Rahman M.F., et al. Human monkeypox and preparedness of Bangladesh: A knowledge and attitude assessment study among medical doctors. J Infect Public Health. 2023;16(1):90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sallam M., Al-Mahzoum K., Al-Tammemi A.B., Alkurtas M., Mirzaei F., Kareem N., et al. Assessing healthcare workers' knowledge and their confidence in the diagnosis and management of human monkeypox: a Cross-Sectional study in a middle eastern country. Healthcare. 2022;10(9) doi: 10.3390/healthcare10091722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sallam M., Al-Mahzoum K., Dardas L.A., Al-Tammemi A.B., Al-Majali L., Al-Naimat H., et al. Knowledge of human monkeypox and its relation to conspiracy beliefs among students in jordanian health schools: filling the knowledge gap on emerging zoonotic viruses. Medicina. 2022;58(7) doi: 10.3390/medicina58070924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang B., Peng X., Li Y., Fu L., Tian T., Liang B., et al. Perceptions, precautions, and vaccine acceptance related to monkeypox in the public in China: a cross-sectional survey. J Infect Public Health. 2022;16(2):163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong C., Yu Z., Zhao Y., Ma X. Knowledge and vaccination intention of monkeypox in China's general population: a cross-sectional online survey. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022;52 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alshahrani N.Z., Alzahrani F., Alarifi A.M., Algethami M.R., Alhumam M.N., Ayied H., et al. Assessment of knowledge of monkeypox viral infection among the general population in saudi arabia. Pathogens. 2022;11(8) doi: 10.3390/pathogens11080904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gagneux-Brunon A., Dauby N., Launay O., Botelho-Nevers E. Attitudes toward Monkeypox vaccination among healthcare workers in France and Belgium: a part of complacency? J Hosp Infect. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2022.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sah R., Mohanty A., Singh P., Abdelaal A., Padhi B.K. Monkeypox and occupational exposure: Potential risk toward healthcare workers and recommended actions. Front Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1023789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joo S.H., Jo I.S., Kim H.J., Lee C.U. Factors associated with dementia knowledge and dementia worry in the south korean elderly population. Psychiatry Invest. 2021;18(12):1198–1204. doi: 10.30773/pi.2021.0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meltzer G.Y., Chang V.W., Lieff S.A., Grivel M.M., Yang L.H., Des Jarlais D.C. Behavioral correlates of COVID-19 worry: Stigma, knowledge, and news source. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21) doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ajman F., Alenezi S., Alhasan K., Saddik B., Alhaboob A., Altawil E.S., et al. Healthcare workers' worries and monkeypox vaccine advocacy during the first month of the WHO monkeypox alert: Cross-Sectional survey in saudi arabia. Vaccin. 2022;10(9) doi: 10.3390/vaccines10091408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou M., Guo W. Social factors and worry associated with COVID-19: evidence from a large survey in China. Soc Sci Med. 2021;277 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y., Li Q., Tarimo C.S., Wu C., Miao Y., Wu J. Prevalence and risk factors of worry among teachers during the COVID-19 epidemic in Henan, China: a cross-sectional survey. Bmj Open. 2021;11(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong J., Pan B., Jiang H.J., Zhang Q.M., Xu X.W., Jiang H., et al. The willingness of Chinese healthcare workers to receive monkeypox vaccine and its independent predictors: a cross-sectional survey. J Med Virol. 2022 doi: 10.1002/jmv.28294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cata-Preta B.O., Wehrmeister F.C., Santos T.M., Barros A., Victora C.G. Patterns in wealth-related inequalities in 86 low- and middle-income countries: global evidence on the emergence of vaccine hesitancy. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(1 Suppl 1):S24–S33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moola S., Gudi N., Nambiar D., Dumka N., Ahmed T., Sonawane I.R., et al. A rapid review of evidence on the determinants of and strategies for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in low- and middle-income countries. J Glob Health. 2021;11:5027. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.05027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected in this study will not be publicly available. However, the corresponding author can be contacted for de-identified data upon reasonable request.