Abstract

Background

The prevention and treatment of eating disorders relies on an extensive body of research that includes various foci and methodologies. This scoping review identified relevant studies of eating disorders, body image, and disordered eating with New Zealand samples; charted the methodologies, sample characteristics, and findings reported; and identified several gaps that should be addressed by further research.

Methods

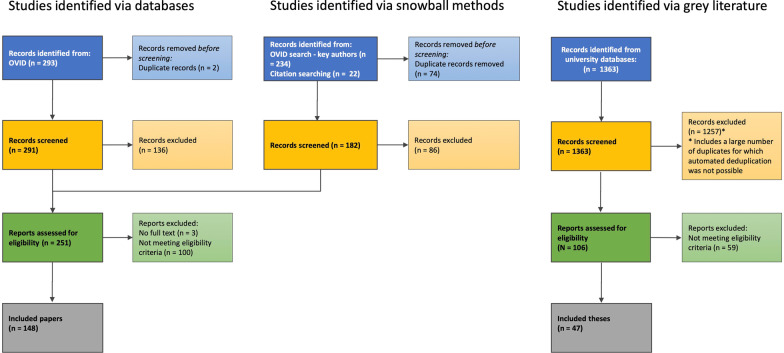

Using scoping review methodology, two databases were searched for studies examining eating disorders, disordered eating, or body image with New Zealand samples. Snowball methods were further used to identify additional relevant articles that did not appear in initial searches. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of 473 records. Full text assessment of the remaining 251 records resulted in 148 peer-reviewed articles being identified as eligible for the final review. A search of institutional databases yielded 106 Masters and Doctoral theses for assessment, with a total of 47 theses being identified as eligible for the final review. The included studies were classified by methodology, and the extracted information included the study foci, data collected, sample size, demographic information, and key findings.

Results

The eligible studies examined a variety of eating disorder categories including binge-eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia nervosa, in addition to disordered eating behaviours and body image in nonclinical or community samples. Methodologies included treatment trials, secondary analysis of existing datasets, non-treatment experimental interventions, cross-sectional observation, case-control studies, qualitative and mixed-methods studies, and case studies or series. Across all of the studies, questionnaire and interview data were most commonly utilised. A wide range of sample sizes were evident, and studies often reported all-female or mostly-female participants, with minimal inclusion of males and gender minorities. There was also an underrepresentation of minority ethnicities in many studies, highlighting the need for future research to increase diversity within samples.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive and detailed overview of research into eating disorders and body image in New Zealand, while highlighting important considerations for both local and international research.

Keywords: Eating disorders, Anorexia nervosa, Bulimia nervosa, Binge eating disorder, Scoping review, New Zealand

Plain English summary

Research into eating disorders should include different methods, and should be relevant to people of different ages, gender identities, and ethnicities. We completed a scoping review of research into eating disorders, disordered eating, and body image in New Zealand samples. We searched academic databases for relevant articles, and then screened the articles for eligibility. We then hand-searched key articles, and searched databases again using the names of key authors. A total of 148 peer reviewed articles and 47 theses were eligible for the review, and from these we extracted data on the study method, sample characteristics, and the focus and results. A wide range of methods and sample sizes were reported, and the studies explored several different eating disorders, as well as disordered eating and body image in nonclinical samples. However, the studies often involved all or mostly female samples, few to no gender minority participants, and an underrepresentation of minority ethnicities. Funders should provide adequate time and financial resources to fund recruitment from historically under-represented groups, emphasising their involvement as active researchers. In addition, funders should consider financing the use of novel or underutilised methods to advance knowledge in this field.

Introduction

Eating disorders such as binge-eating disorder (BED), bulimia nervosa (BN), and anorexia nervosa (AN) are complex and potentially life-threatening psychiatric illnesses. Research in the New Zealand population suggests a lifetime prevalence of 1.9% for BED, 1–1.3% for BN, and 0.6% for AN [1, 2]. These disorders create a significant burden upon the lives of those affected, with many individuals facing prolonged periods of inpatient treatment or multiple relapses. Although research into eating disorders has made substantial progress in recent years, the limited success of available treatments underscores the need for a more complete picture of how to best understand and approach this cluster of disorders.

In addition to the more commonly acknowledged eating disorders noted above, there is a growing awareness surrounding those whose symptoms fall within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) [3] other specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED) diagnostic category. These disorders include atypical or subthreshold forms of BN, AN, and purging disorder which previously were included in the DSM-IV eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) category, and the newly included night eating syndrome. Despite this group of disorders having been identified as being the most prevalent [4], research surrounding them is comparatively sparse.

At a sub-threshold level, eating disorder psychopathology is common in New Zealand, and has been reported in adolescents, university students, and middle-aged samples [5–7]. Disordered eating is often tightly intertwined with body dissatisfaction—a core symptom in the diagnostic criteria for AN and BN [3], which is also suggested to be relevant for BED [8]. Body dissatisfaction is regarded as a significant risk factor for the development of eating disorders [9, 10], with etiological models commonly citing the relationship between body dissatisfaction and subthreshold disordered eating. Body dissatisfaction can be seen as almost normative among young women and, increasingly, young men [11]. In light of this, our understanding of disordered eating can be supplemented by research into body dissatisfaction at both a clinical and subthreshold level.

Although many aspects of eating disorders, subthreshold disordered eating, and body dissatisfaction are studied extensively internationally, it is often unclear whether findings generalise to a New Zealand population. Moreover, even where such findings are applicable, there remains a need to understand these issues in a manner consistent with New Zealand’s unique sociocultural context [12, 13]. Achieving this requires a comprehensive body of research to be conducted within New Zealand, ideally with a range of study designs to ensure a detailed and broad understanding of these issues. Moreover, this research should adequately cover the range of issues pertaining to body image and eating disorders, and include samples that are representative of the population as a whole (such as Indigenous Māori and Pasifika populations). To this end, it is critical that local researchers are aware of what is available within the literature and what is lacking, thus informing the direction for future research and methodologies. However, we were unable to identify any comprehensive reviews of relevant studies involving New Zealand-based participants, thereby hindering progression of research into the issues at hand.

In an effort to bridge the gap between extant research and future projects, the present review scopes and synthesises the foci reported by studies examining eating disorders, disordered eating, and body image within studies that include New Zealand samples. This review was informed by scoping methodology outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) [14]. It involved: (a) the identification of relevant journal articles and theses; (b) charting the foci, methodologies, sample characteristics, and findings reported in the identified literature; and (c) a descriptive review of what was included, as well as gaps and areas which may be expanded upon.

Methods

Research question

The scoping review was informed by the research question: “To date, what are the methodologies and results reported by studies that have examined eating disorders, disordered eating, and body image in clinical and non-clinical samples in New Zealand?”.

Eligibility

Meeting initial eligibility criteria was dependent on (1) the full text being available, (2) some portion of the sample living in New Zealand during the research, (3) the article or thesis being available in English, (4) the record not being a duplicate, and (5) the topic or a part of the focus being within scope. The scope was informed by the overarching research question of this review, and research items needed to include an examination of eating disorders, disordered eating, or body image in New Zealand samples.

Included eating disorder diagnoses were BED, BN, and AN in addition to disorders in the Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder (OSFED) category (DSM-5) or the former Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS) category (DSM-IV-TR) [15]. Also included were studies where only symptoms of these disorders (e.g. binge eating, purging) were assessed. Not included were Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), pica and rumination disorder; categories shifted to the eating disorders section of DSM-5 from the DSM-IV-TR Feeding and Eating Disorders of Early Childhood Section [3, 15]. Body image in the context of this review included perceptions of one’s own body shape and size, but excluded research items that focused only on concerns such as perceived facial flaws [16], which are often a feature of body dysmorphic disorder. Lastly, research on samples of clinicians working in eating disorder treatment were included, given that this adds considerably to knowledge surrounding eating disorders and their treatment in New Zealand.

Both qualitative and quantitative studies were deemed in scope, as were case studies and case series. International studies that included original data from one or more New Zealand participants were included; however, meta analyses and systematic reviews were not, given that relevant data were likely already published elsewhere. It was decided that conference abstracts would be excluded, given that the findings were either published elsewhere, or the abstracts did not include sufficient information to meet basic eligibility criteria. Lastly, any trials that were in progress but unpublished were also excluded, as it would not be possible to chart the findings of those studies.

Initial database search

To locate references for journal articles from a wide range of sources, relevant search terms were entered into Ovid (EMBASE, psychINFO). The search terms “eating disorder*.kw”, “anorexia nervosa.kw”, “bulimia nervosa.kw”, “binge eating disorder.kw”, “disordered eating.kw”, and “body image.kw” were combined using the “OR” function. This result was then combined with “new zealand.af” using the AND function, and the results were deduplicated. No additional search limitations were used in Ovid. The cut-off date for this and subsequent searches was set to 20 May, 2021.

Snowball searches

During the initial screen of records returned in Ovid, seven authors known to publish research within this scope frequently appeared as first authors. Publications from these authors were further searched in Ovid by entering the search terms “jordan jennifer.au”, “carter frances a.au”, “gendall kelly a.au”, “mcintosh virginia v w or mcintosh virginia violet williams or mcintosh virginia vw).au”, “bulik cynthia m.au”, “wilksch simon m or wilksch sm.au”, “latner janet d or latner jd.au”. These searches were combined using the OR function, and the result was then combined with “new zealand.af” using the AND function. The results were deduplicated within Ovid before being merged with the initial OVID search records, and the combined results were again deduplicated.

The citations within key papers were also hand-searched by two reviewers (HK and LC) for additional relevant publications within New Zealand. Key papers included relevant epidemiological studies and treatment trials known among New Zealand eating disorders researchers. Referenced papers were then located and screened using the same criteria and checklist. Furthermore, when papers reporting secondary analyses referred back to publications which described original study samples, those publications were identified and screened for inclusion.

Grey literature search

To locate Master’s and Doctoral theses, institutional research archives were searched for each of the University of Otago (OURArchive), University of Waikato (Research Commons), University of Canterbury (College of Science, College of Arts), Massey University (Massey Research Online), Auckland University of Technology (Open Repository), and Victoria University of Wellington (Open Access), and University of Auckland (ResearchSpace). A total of 29 potentially relevant theses, including 25 from the University of Auckland, were unavailable online or were only accessible only to staff and students at the relevant institutions. As such, full-text screening was unable to be completed for these records.

The terms “binge eating disorder”, “bulimia nervosa”, “anorexia nervosa”, and “body image” were entered into each university research archive and limited to thesis where possible. The terms “eating disorder” and “disordered eating” were also entered into the same archives. In some instances, these latter terms returned the same results as one of the initial four search terms, such as the results for “eating disorder” being the same as those for “binge eating disorder” in one database. In such cases, results were not added to the final number of records to be screened. In addition, when a very large number of unrelated results were returned for thesis search terms, the results for those terms were limited to “title contains”.

In some cases, the findings from grey literature had already been published in peer reviewed journals. To avoid overlap in these situations, the grey literature record was removed as a duplicate in favour of the published article. Further journal articles identified during this process were labelled as being found via snowball search.

Record screening and eligibility

Search results from OVID were exported into EndNote, and then entered into an Excel spreadsheet to be screened separately by two blind reviewers (HK and LC). The reviewers first pre-screened the titles and abstracts of each record for relevance. Journal articles that were eligible for full-text searching were then located where possible, and the reviewers filled out a checklist to determine whether predetermined eligibility criteria were met. Following blind review, authors HK and LC met to discuss a small number of cases where the decision to include or exclude a record was inconsistent. In these cases, the records were further assessed and a final decision was agreed upon for each, with a total of 10 papers being discussed and 7 of these being excluded from the review.

Data extraction and study classification

For each included research item, a range of data were extracted. The relevant population(s) or construct(s) of interest were identified, including any specific eating disorders being examined, disordered eating among nonclinical (NC) populations, or clinicians working within eating disorder treatment settings. The focus of each study was also briefly summarised, as were the key data collection instruments or measures. Gender and ages of participants were recorded as specified in the research article or thesis, however gender data were converted to percentages where applicable, and age ranges were favoured where available. Ethnicities were also recorded as specified, however for consistency, terms such as “Caucasian” and “New Zealand European” were recorded as “European” for the purposes of this review, and these data were also converted to percentages where applicable. The key findings were summarised based upon information within abstracts and full texts. Lastly, each study was categorised according to the primary methodology used, while those that analysed data from existing treatment trial and survey datasets were labelled as secondary analyses.

The scoping review has been registered on OSF (https://osf.io/c8jwn). No ethical approval was required for this review.

Results

Total records included

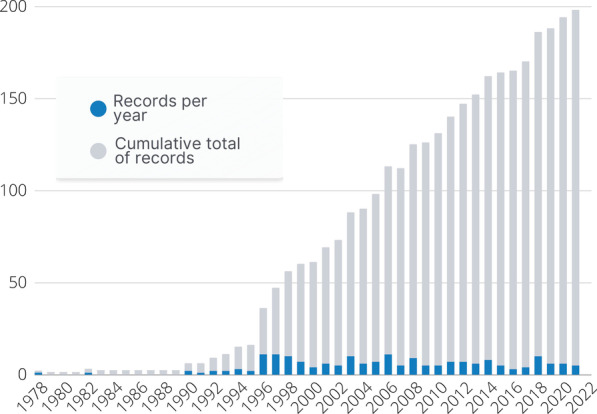

The total number of records identified and excluded at each step of the literature search are detailed in Fig. 1. A total of 195 records were included in the final review, with 148 journal articles and 47 theses (13 Doctoral, 34 Master’s) having met full eligibility criteria for the study. Journal articles were published between December 1978 and May 2021, while theses were completed between 1990 and 2021. The specific completion dates for two theses finalised in 2021 were unable to be verified, however the decision was made to include those in the review. The number of publications per year, in addition to the cumulative total of publications, is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart depicting record identification process and number of records included or removed at each stage

Fig. 2.

Number of included theses or journal articles published each year and cumulative totals

Study classifications

Study methodologies across the journal articles and theses fell into seven broad categories of treatment trials (18 records, Table 1), secondary analyses of existing datasets (50 records, Table 2), non-treatment experimental interventions (17 records, Table 3), cross-sectional research (63 records, Table 4), case control studies (9 records, Table 5), qualitative or mixed-methods (28 records, Table 6), or case studies and series (10 records, Table 7).

Table 1.

Treatment trials

| References | Population focus | Focus | Key data collected | Sample n | Gender | Age | Ethnicity | Summary findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babbott [59]* | Non-clinical (NC) | Non-concurrent multiple baseline: Trialling acceptance and commitment therapy for disordered eating | EAT-26, AAQ, SWLS, SA-45 | 17 | 12% M 88% F | 18–64 | 64.7% European, 5.9% Māori, 11.8% Indian, 11.8% Latin American, 5.9% South African | Significant decrease in eating pathology, but not general pathology |

| Bulik [18] | BN (BTS) | RCT: Results from end of RCT and follow-up at 6 and 12 months. Therapies were CBT + then randomisation to 1) exposure with response prevention to binges (B-ERP), 2) to purging (P-ERP) or 3) relaxation | Physiological, biological measures, self-report measures, SCID I and II, HDRS, GAF, EDI | 135 | F | 17–45 |

BTS sample 91% European 6% Maori, Pasifika, Asian |

All therapies were effective and did not differ on abstinence or binge purge frequency. B-ERP had advantage for other ED symptoms, and mood but this was not maintained over follow-up |

| Carter [60] | BN (BTS) | RCT: 3-year follow up of BTS | Structured interview of ED symptoms, EDI, HDRS, GAF | 135 (113 at follow up) | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | At the 3-year follow-up, 85% of the sample had no current diagnosis of bulimia nervosa. Failure to complete CBT was associated with inferior outcome. No differential effects were found for exposure versus nonexposure-based treatment |

| Carter [61] | AN (ATS) | RCT: long-term efficacy of three psychotherapies for AN (ATS) | SCID (DSM-IV). Global AN symptom status,, physical, cognitive and behavioural ED measures, EDE, EDI-2, GAF, HDRS | 43 | F | 17–40 |

ATS sample 100% European |

SSCM advantage over CBT and IPT during treatment was not sustained. All effective bus no significant differences among treatments at follow-up |

| Clyne [62] | BED | Single case design with multiple baseline evaluation: preliminary trial of a psychoeducational group programme of emotion regulation for treatment of BED | Daily Log of Eating and Emotions, BES, QEWP, DASS, PSS, The COPE, EIS, TAS-20, ATSS | 11 | F | 18–69 | 100% European | Reduced binge-eating, alexithymia, stress, and depression. Improvements in cognition. At 2/3 month follow up, all participants no longer met criteria for BED |

| Clyne [63] | BED | Non-randomised with waitlist control group: regulation of negative emotion as a possible BED treatment | QEWP, EDE, EDE-Q, BES, EES | 23 | F | 18–65 | 91.3% European, 4.3% Māori, 4.3% Other | Treatment outcomes comparable to existing therapies for BED |

| Davey [64]* | BN, AN, EDNOS, NC | Quasi-experimental (non-randomised) 2-group comparison: Efficacy of two pre-treatment interventions focused on motivation. Groups were motivation + education versus motivation alone | EDE-Q4, BDI-II, Dflex, MSOC, Change Continuum | 252 | 97% F, 3%M | 11–62 | 88.5% European, 4.8% Māori, 4.8% Asian, 0.8% Pasifika, 0.4% South American, 0.8% Middle Eastern | Improvements in motivational stage of change were observed in both groups, while improvements in patient readiness, confidence and importance to change as well as treatment attendance were identified in the pure Motivation Group |

| de Hoedt Norgrove [65]* | Emotional eaters | Multiple baseline design: Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for emotional eating using a multiple baseline | Feedback questionnaire, MEAQ, valuing questionnaire, AAO, CES, GHQ, journal entries (e.g. frequency of unhealthy eating) | 8 |

6 F 2 M |

18–52 | 75% European, 12.5% European/Māori, 12.5% Māori/ Pasifika | Reduction in binge eating, associated with decreased experiential avoidance and cognitive inflexibility |

| McIntosh [17] | AN (ATS) | RCT: comparing efficacy of CBT versus IPT versus a control therapy (nonspecific supportive clinical management | Global AN symptom status, SCID for DSM-IV, EDE, HDRS, GAF, EDI-2 | 56 | F | 17–40 |

ATS sample 96% European |

Nonspecific supportive clinical management (subsequently called SSCM) superior in completers and intention to treat analyses |

| McIntosh [66] | BN (BTS) | RCT: Long-term follow up of participants from RCT for BN | SCID, Structured interview of ED symptoms, EDI, HDRS, GAF | 135 (109 at follow up) | F | 14–45 | BTS sample | Those in in SSCM group more likely to have a good outcome post-treatment, but no differences between groups at long-term (5 year) follow-up |

| McIntosh [19] | BED, BN (BEP) | RCT: efficacy of three therapies for binge eating: Standard CBT versus CBT augmented with schema therapy versus CBT with a focus on appetite | SCID-I and II, EDE-12, EDI-2, SCL-90-R | 56 | F | 16–65 | BEP sample | All groups improved but no significant differences between therapies |

| Mercier [67]* | BN | RCT: Tested intervention aiming to alter coping behaviours and cognitive processes in those with BN versus directly targeting clinical features. Wait-list control and follow-up design | General information questionnaire, DSSI-R, The Bulimia Test, Affectometer 2, BDI, RSES, STAI, TAI | 24 | F | 19.3–41.1 | Not stated | Decreased BN behaviours and cognitions following alternative intervention, little difference between intervention groups by 3 years |

| Roberts [68] | BN, AN | Single arm design: Efficacy and feedback on group cognitive remediation therapy | Dflex, Autism Quotient, EDE-Q, DASS-21, BMI, qualitative questionnaire | 28 |

96% F 4% M |

M 25.07 (SD 8.25) | Not stated | Intervention was effective and had positive qualitative feedback |

| Then [69]* | AN | Single arm design: Efficacy of metacognitive therapy modified for the treatment of A | BMI, EDE-Q, MCQ-30, TCQ | 12 | Not stated | M 22.17 (SD 5.17) | 1 NZE, 2 Māori, 3 Samoan, 4 Cook island, 5 Tongan, 6 Niuean, 7 Chinese, 8 Indian, 9 other | Mixed results but there were reductions in patients positive beliefs about worry, depressive symptoms, worries and rumination levels following metacognitive therapy |

| Wallis [70]* | BED | Quasi-experimental (non-randomised intervention) with control: Teaching emotional discrimination and management in a group programme for those with BED | EDI-2, MHO, BDI, BAI, EES, COPE, GHQ | 6 (BED n = 3, NC n = 3) | F | 25–47 | 83% European, 17% Māori | EDI-2, EES, BDI, BAI, and COPE results indicated positive results following the programme |

| Wilksch [71] | NC (MS -T) | RCT: Trialling online programs for efficacy in reducing risk of disordered eating in an Australasian sample | EDE-Q | 575 | F | 18–25 | 82.2% European, 8.8% Asian, other not stated | Media Smart Targeted program reduction in DE |

| Wilksch [72] |

BED, BN, AN, OSFED, NC (MS—T) |

RCT: Programme seeking to reduce risk of eating disorder diagnosis in NZ and Australia | EDE-Q | 316 (MS-T n = 122 (baseline ED diagnosis n = 90): CT = 194 (baseline ED diagnosis n = 130)) | F |

M 20.8 (SD 2.26) |

MS-T sample | At 12-month follow up MS-T participants were 75% less likely than controls to meet ED criteria, this finding was also significant amongst both non-treatment seekers and treatment seekers |

| Wilksch [73] | NC | RCT: An online 9-module eating disorder risk reduction program (Media Smart—Targeted (MS-T)) and control condition (positive body-image tips) | DASS-21, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (dependence on alcohol, dependence on recreational drugs, high suicidality) | 316 | F | 18–25 | States most common is European and Asian | MS-T shows positive effect on eating disorder risk, as well as other mental health factors |

NC non-clinical, RCT randomised-controlled trial, EAT Eating Attitudes Questionnaire, AAQ Acceptance and Action Questionnaire, SWLS Satisfaction with Life Scale, SA-45 Symptom Assessment-45 Questionnaire, SCID Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders, HDRS Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, GAF Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, EDI Eating Disorders Inventory, EDE Eating Disorder Examination, BES Binge Eating Scale, QEWP Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns, COPE Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory, EI Emotional Intelligence, TAS-20 Toronto Alexithymia Scale, ATSS Activated Thoughts in Simulated Situations, EDE Eating Disorders Examination interview, EDE-Q Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, EES Emotional Empathy Scale, BDI Beck Depression Inventory, Dflex Detail and Flexibility Questionnaire, MSOC Motivational Stages of Change, MEAQ Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire, AAQ The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire, CES Compulsive Eating Scale, GHQ General Health Questionnaire, CSPRS-AN Collaborative Study Psychotherapy Rating Scale—Anorexia Nervosa, SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90-Revised, DSSI-R Delusions-Symptoms-State Inventory-Revised, RSES Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, STAI State Trait Anxiety Inventory, TAI Test Anxiety Inventory, DASS Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale, PSS Perceived Stress Scale, EIS Emotional Intelligence Scale, BMI body mass index, MCQ Metacognition Questionnaire, TCQ Thought Control Questionnaire, MHO Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire, COPE Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced

*Identifies that the record is a thesis

Table 2.

Secondary analyses

| References | Population focus | Focus | Key data collected | Sample n | Gender | Age | Ethnicity | Summary findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson [74] | BN (BTS) | Temperament and character ratings at the beginning of CBT intervention and one year later | TCI, HDRS, B-ERP, P-ERP | 135 (91 for this report) | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Decreases in harm avoidance temperament and increase in self-directedness |

| Bourke [75] | BN (BTS) | Neuropsychological function in BN with comorbid psychological conditions | Diagnostic interviews, neuropsychological testing | 41 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Borderline personality disorder and MD together associated with impaired cognitive function |

| Bulik [76] | BN (BTS) | Examined BN sample with and without personality disorders, and self-directedness in predicting presence of personality disorders | SCID for DSM-III-R, HDRS, custom structured interview of BN symptoms, GAF | 76 | F | > 16 | BTS sample | 63% had 1or more personality disorder diagnoses, which were associated with greater depressive symptoms, laxative use, greater body dissatisfaction, worse global functioning, and lower self-directedness |

| Bulik [77] | BN (BTS) | Examining histories of anxiety disorders in those with BN | SCID I (DSM-III-R), age onset, Self-report ED symptoms | 114 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Anxiety disorders onset earlier than BN |

| Bulik [78] | BN (BTS) | Salivary reactivity to palatable food before, during, and after treatment | SCID (DSM-III-R), HDRS, Physiological responses | 31 | F | 18–40 | BTS sample | After treatment, salivation increased significantly (p = .002) over baseline after presentation of the same foods |

| Bulik [79] | BN (BTS) | Comparing onset of binge eating, dieting and BN in relation to clinical characteristics and personality traits | SCID modified, SCID II, HDRS, TCI | 108 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Dieting preceded binge eating in the majority of women with BN. In the minority of women where binge eating precedes dieting, markedly higher novelty seeking and lower harm avoidance are displayed |

| Bulik [80] | BN (BTS) | Comparing BN participants with/without comorbid alcohol dependence | SCID (DSM-III-R), HDRS, GAFS, EDI-2, TCI, BIS, Défense Style Questionnaire | 114 | F | 17–45 | BTS Sample | Women with comorbid BN and alcohol dependence have increased psychopathology, impulsivity and novelty seeking |

| Bulik [81] | BN, AN, MD | Comparing prevalence and ago of onset of adult and childhood anxiety disorders relative to primary diagnosis of BN, AN, MD and NC controls | Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies, SCID for DSM-III-R | 68 (AN), 116 (BN), 56 (MD), 98 (NC) | F | AN: M 31.3, BN: 26.0, MD: M 30.6, NC: M 35.5 | Not stated | Certain anxiety disorders (specific phobia, overanxious disorder) were non-specific risk factors for later affective and eating disorders, while others more specific (e.g. AN and antecedent OCD) |

| Bulik [82] | BN (BTS) | Predictors of successful BN treatment | SCID and SCID-II HDRS, GAFS, EDI-2, Bulimia Cognitive Distortions Scale TCI | 98 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Baseline symptomatology and personality factors predicted rapid and sustained treatment response |

| Bulik [83] | BN, AN (BTS, Christchurch Outcome of Depression Study, Sullivan et al. [84] study) | Personality traits and history of suicidal behaviour in BN, AN and MD | TCI |

269 (AN 70; BN 152; MDD 59) |

F | 22–39 | Not stated for AN or MDD sample but BN sample was part of the BTS sample | Suicide attempts are equally common in women with eating disorders and women with depression, and were associated with the temperament dimension of high persistence and the character dimensions of low self-directedness and high self-transcendence |

| Carter [85] | BN (BTS) | Examining changes in information processing speed following CBT | Stroop test performance, self-reported recent binge, vomiting, and other purging | 98 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Information processing speed not associated with change across BN treatment |

| Carter [86] | BN (BTS) | How performance on cue reactivity test predicted outcome of psychotherapy for BN | Clinician interview, EDI, HDRS, GAF, blood pressure, heart rate, salivation | 135 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Abstention during pre-treatment cue reactivity task was associated with better outcome at 6-month follow-up |

| Carter [87] | BN (BTS) | How CBT for BN changed cue reactivity and associations with self-report measures | Clinician interview, EDI, HDRS, GAF, blood pressure, heart rate, salivation | 135 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Association between favourable treatment outcome and low cue reactivity on self-report measures at posttreatment |

| Carter [88] | BN (BTS) | Evaluating specific hypotheses on the relationship of cue reactivity and outcome in BN women | Structured interview, EDI, HDRS, Axis V of DSM-III-R, self-report, physiological measures | 135 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Pre-treatment cue reactivity could not predict most effective treatment modality |

| Carter [89] | BN (BTS) | Whether having a child after BN treatment puts women at increased risk for ED or depression | SCID (DSM-III-R), life charts (key life events, e.g. pregnancy), menstrual + weight history, pregnancy/childbirth | 135 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Childbirth was not specifically associated with symptomatology following treatment for bulimia nervosa |

| Carter [90] | BN (BTS) | Factors related to childbirth reported at BN treatment follow-up | SCID, EDI, HDRS, BMI, GAF, BDI, SCL | 125 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Demographic variables and poor functioning following treatment predictive of non-conception |

| Carter [91] | BN (BTS) | Influence of pre-treatment weight across treatment and five-year follow-up |

Pre-treatment BMI, BMI at follow-up |

134 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Participants who were overweight at baseline gained more weight than those in low and normal weight groups |

| Carter [92] | BN (BTS) | 5-year follow-up of those who participated in BTS RCT for BN | SCID (DSM-III-R), EDI, HDRS, GAF, BMI | 80 | F | 17–45 at treatment | ATS sample | Five years after treatment, approximately one half of the participants had changed substantially in weight. Patients who gained weight were more likely to have been heavier and more dissatisfied with their body |

| Carter [93] | BN (BTS) | Testing whether able to assess cue reactivity with a self-report questionnaire | Adapted Situational Appetite Measure (SAM) | 135 (complete data for 82) | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | A self-report questionnaire provided useful information regarding cue reactivity among women treated for bulimia nervosa. Greater improvements in cue reactivity associated with favourable treatment outcomes |

| Carter [94] | BN (BTS, Christchurch Outcome of Depression Study, postpartum study [95]) | Sex frequency, enjoyment, and issues in women with AN, MD, or in postpartum period | Social Adjustment Scale | 76 (10 AN) | F | AN: 28.4 (SD 6.1) | Various samples | AN and MD groups more likely to have had sex in prior two weeks, but also more likely to report sexual problems, than postpartum group |

| Carter [96] | BN (BTS) | Relationship between weight suppression prior to treatment and treatment outcomes | BMI | 132 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Found that weight suppression did not predict treatment outcome but did predict weight gain |

| Carter [97] | AN (ATS) | Whether severity of weight suppression predicted total rate and amount of weight gain during AN recovery | BMI | 56 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Weight suppression was positively associated with total weight gain and rate of weight gain over treatment |

| Falloon [98]* | BED, BN (BEP) | Focused on how closely therapists in the BEP RCT adhered to each of three psychotherapies for binge eating | Collaborative Study Psychotherapy Rating Scale-Binge Eating (CSPRS-BE) | 112 participants, 4 therapists | F | M 35.3 (SD 12.6) | 67% NZ European, 17% other European, 9.8% Māori, 3.6% Asian, 2.7% other | Therapy modalities were distinguishable by raters blind to treatment |

| Gendall [99] | BN (BTS) | Comparing nutrient intake of women with BN regarding recommended dietary allowances, and to population sample | Food diaries |

50 (BN) 468 (Population sample) |

F |

BN:17–45 Population: 19–44 |

BTS sample | Food eaten outside of binges episodes associated with low iron, calcium and zinc, and overall energy intake. Overcompensation for this during binge episodes |

| Gendall [100] | BN (BTS), MD (Christchurch Outcome of Depression study) | Comparison of visceral protein and haematological status between BN and depression controls | SCID, HDRS, structured interview of recent BN symptomatology Bloodwork (visceral protein and haematological status) |

152 (BN) 68 (MD) |

F |

BN: 17–45 MD: 18–46 |

BTS and MD samples | BN and MD groups did not differ on visceral protein or haematological measures. Low prealbumin and albumin levels were associated with more frequent vomiting. High frequency of vomiting and alcohol abuse/dependence, may increase the risk of subclinical malnutrition |

| Gendall [101] | BN (BTS) | Factors association with BMI and weight change in BN, before, during, and after CBT treatment | HDRS, GAFS, EDI, physical measurements | 94 | F | 17–45 | BTS Sample | CBT is not usually accompanied by substantial weight gain |

| Gendall [102] | BN (BTS) | Menstrual cycle and associated factors in BN patients. How this changed across and after CBT treatment | Blood sampling, self-reported food/drink intake, BMI, SCID, GAFS, HDRS | 82 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Association between menstrual irregularity and indices of nutritional restriction, not reflected by energy intake or body weight |

| Gendall [103] | BN (BTS) | Blood lipid and glucose changes during and after CBT for BN (BTS) | Blood tests, BMI, SCID, HDRS | 135 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | At 3-year follow up, plasma HDL-cholesterol increased and total cholesterol decreased significantly in the group as a whole |

| Gendall [104] | BN (BTS) | Thyroid hormone levels in women before and after CBT for BN | SCI for DSM-III-R, HDRS, BMI, blood samples (serum T4 and free T4) | 107 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Lower pre-treatment T4 associated with persisting ED at follow up |

| Gendall [105] | BN (BTS) | Childhood gastrointestinal (GI) issues and BN psychopathology | SCID, structured interview questions about childhood GI complaints | 135 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Individuals with childhood GI complaints and other risk factors for BN may be at greater risk of developing a more severe eating disorder at an earlier age |

| Gendall [106] | AN (ATS) | Factors associated with amenorrhea in AN | SCID (DSM-IV), HDRS, TCI, additional questions on eating/weight/treatment/menstrual status, food diary, physical measurements | 39 | F | 23.3 ± 6.2 | ATS sample | The use of exercise to control weight, low novelty seeking scores, and low systolic blood pressure were predictors of amenorrhea independent of body mass index |

| Jenkins [107]* | AN (ATS) | Whether motivation to recover is related to treatment outcome in those with anorexia nervosa | SCID for DSM-IV, Global AN status, motivation measures, including Motivational Interviewing Skills Code Version 2.0 Outcome Rating Scale | 53 | F | 18–45 | ATS sample | Higher levels of positive change talk (and lower levels of negative) did not associate with better treatment outcome. No significant difference in treatment outcome observed between participants with different positive/negative change talk ratios |

| Jordan [108] | AN (ATS) | Comparing history of anxiety and substance use disorders in those with AN and MDD | SCID for DSM-III-R |

90 (40 AN; 58 MDD) |

F | 18–40 |

AN: 98% European MDD: 93% European |

OCD elevated in AN compared to MDD sample |

| Jordan [109] |

AN (ATS) BN (BTS) |

Comparing lifetime comorbidities in participants with AN, BN, and major depressive disorder | SCID-P, SCID II, HDRS, GAF | 56 (AN), 132 (BN), 100 (MD) | F | 17–40 | AN: 96% European, BN 91% European, MD 94% European | AN had higher OCD, AN-BP and BN elevated Cluster B personality disorders; all samples elevated Cluster C personality disorders |

| Jordan [110] | AN (ATS) | Assessing the constructs measured by YBC-EDS | YBC-EDS, BMI, HDRS, EDE-12, EDI-2 | 56 | F | 17–40 | 100% European (96% NZ European, 4% European born outside NZ) | Measured severity, YBCEDS sensitive to change following treatment |

| Jordan [111] | AN (ATS) | Clinical characteristics of participants who prematurely terminate treatment | SCID, SCID II, TCI-293, GAF, HDRS, EDE-12, EDI-2 | 56 | F | 17–40 | Predominantly European | Lower self-transcendence scores associated with premature treatment termination |

| Jordan [112] | BN (BEP) | Comparing symptoms and comorbidities across BN-P, BN-NP, and BED groups | SCID for DSM-IV, MADRS, GAF, EDE, EDI-2 | 112 | F | > 16 | BEP sample | BN-NP sits between BN and BED but some distinct features |

| Jordan [113] | AN (ATS) | Process and other factors associated with treatment non-completion in AN | Treatment Credibility Scale, TCI, VTAS-R, VPPS, therapy alliance ratings | 56 | F | 17–40 | ATS sample | Predicted by treatment credibility, lower self-transcendence, and lower early therapy alliance |

| Lacey [114] | BN, AN, OSFED, EDNOS (PRIMHD) | Comparing clinical characteristics and health service use for EDs by Māori and non-Māori |

National health database PRIMHD data |

3,835 | F | 10+ | 7% Māori | Māori were under-represented in treatment services. Once in treatment, duration was comparable. Māori more likely to be treated for BED or EDNOS |

| McIntosh [115] | AN (ATS) | Relevance of BMI cut off in diagnosing AN | SCID for DSM-IV, EDE, HDRS, GAF, EDI-2, BIAQ, TFEQ, EAT, SCL-90, anthropometric and medical measures | 56 | F | 17–40 | ATS Sample | Little difference between strict versus lenient BMI groups |

| McIntosh [116] | AN (ATS) | Therapist adherence to three different psychotherapies in ATS RCT | CSPRS-AN |

56 (AN) 3 therapists |

FF therapists | AN: 17–40, not stated for therapists | ATS sample | Good adherence to therapy types, blind raters clearly distinguished therapies |

| McIntosh [117] | AN (ATS) | Assessing distinctiveness of three therapies and change over therapy in RCT for AN | CSPRS-AN (blind raters) | 53 | F | M 23.1 | ATS sample | Therapies distinguishable, subscale measures higher for corresponding therapies, both SSCM and CBT sessions rated significantly higher in the middle stage of therapy |

| Rowe [118] | BN (BTS) | Whether poorer treatment outcome for those with comorbid borderline personality disorder (BPD) and BN compared to other personality disorders (PD) or no personality disorder | SCID-I and II for DSM-III-R, CBSI, HDRS, GAF, EDI, TCI, EDI | 135 | F | 17–45 | 91% NZ European | Those with BN and BPD more impaired at pre-treatment for BN and comorbid BPD, but treatment outcome over 3 years of follow up was not poorer for this group |

| Rowe [119] | BN (BTS) | Impact of Avoidant personality disorder on BN treatment outcome over 3 years | SCID-I, SCID-II, CBSI, HDRS, GAF, self-report questionnaires including EDI | 134 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | No impact on eating disorder symptoms, but worse depressive and psychosocial functioning at pre and post treatment |

| Rowe [120] | BN (BTS) | PD severity/number of PDs as a predictor of BN treatment outcome | SCID (DSM-III-R), CBSI, HDRS, GAF, EDI | 134 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | More PDs did not impact outcome at 3 years |

| Rowe [121] | BN (BTS) | Personality dimensions as predictors of 5-year outcomes among BN women | SCID-I, SCID-II, GAF, EDI-2, TCI, personality reassessment, 12-month ED behaviours and mood disorders | 134 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | No single personality measure predicted 5-year outcome, and so comprehensive personality assessment is desirable |

| Sullivan [122] | BN, AN (BTS) | Differences between those with BN with/without AN history | SCID, HDRS, GAFS, EDI-2, TCI, Defence Style Questionnaire | 114 | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | Some differences between those with and without prior AN, but not distinct groups |

| Sullivan [123] | BN, MD (BTS) | Comparing total serum cholesterol in women with BN versus depression versus population norms | SCID, HDRS, GAFS, structured interview to assess last 14 days ED behaviour, blood samples | 126 (AN), 57 (MD) | F | 17–45 | BTS sample | BN women had markedly higher total cholesterol than depressed women, and population norms |

| Surgenor [124] | AN (ATS) | Association between sense of control and variability of AN | SCID-P (DSM-III-R (with psychotic screen), EDI, Shapiro Control Inventory, additional information on ED history including anthropometric measures, menstrual status, and chronicity | 51 | F | M 23.4 (SD 6.4) | ATS sample | Adverse overall sense of control (along with reliance on specific means of gaining control) associated with more severe eating disturbance. Greater use of a negative-assertive style of gaining control associated with a longer time since first diagnosis, desire for control significantly associated with menstrual status |

| Talwar [125]* | Community sample | Correlates of disordered eating behaviours in a community sample of women | EDI-2, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, BMI | 60 | F | 16–55 | 70.8% NZ European, 6.3% Māori | Dysfunctional eating attitudes and behaviours associated with higher perfectionism, lower self-esteem, and elevated body mass. Increased body dissatisfaction significantly predicted BN symptoms |

NC non-clinical, RCT randomised-controlled trial, MD major depression, TCI Temperament and Character Inventory, HDRS Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, B-ERP Binge—exposure to response prevention to binges, P-ERP Purge—exposure with response prevention to purging, SCID Structured Clinical Interview for DSM, GAF Global Assessment of Functioning, EDI Eating Disorder Inventory, BIS Behavioural Inhibition System, BCDS Bulimia Cognitive Distortions Scale, BMI body mass index, SAM Situational Appetite Measure, CSPRS-BE Collaborative Study Psychotherapy Rating Scale—Binge Eating, YBC-EDS Yale Brown Cornell Eating Disorders Scale, EDE Eating Disorders Examination, MADRS Montgomery and Asperg Depression Rating Scale, VTAS-R Revised Vanderbilt Therapeutic Alliance Scale, VPPS Vanderbilt Psychotherapy Process Scale, PRIMHD Programme for the Integration of Mental Health Data, BIAQ Body Image Avoidance Questionnaire, TFEQ Three Factor Eating Questionnaire, EAT Eating Attitudes Test, SCL Symptom Checklist, CSPRS-AN Collaborative Study Psychotherapy Rating Scale—Anorexia Nervosa, CBSI Comprehensive Bulimia Severity Index, SCID-P structured clinical interview for DSM with psychotic screen

*Identifies that the record is a thesis

Table 3.

Non-treatment experimental interventions

| References | Population focus | Focus | Key data collected | Sample n | Gender | Age | Ethnicity | Summary findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyce [126] | NC | Whether media body ideal exposure alters mood and weight satisfaction among restrained eaters, and whether changes in either direction encourage intake of food | RS-CD, DIS, BMI, single-item weight satisfaction scale (10-point), single item hunger scale (7-point), computer task to assess implicit mood, food intake | 107 | F | 18–37 | 66% NZ European, 8% Chinese, 4% NZ European/Māori, 1% Māori, 21% other ethnicities | For restrained eaters, exposure to media images was associated with decreases in self-reported weight satisfaction and negative mood, but did not alter food intake |

| Boyce [127] | NC | Impact of advertent or inadvertent exposure to media or control images (four conditions) and subsequent weight satisfaction and eating among restrained eaters | RS-CD, DIS, single item weight satisfaction scale (10-point), visual analogue scale of hunger, food intake | 174 | F | M 20.43 (SD 6.29) | 79% NZ European, 5% Chinese, 5% NZ European/Māori, 2% Indian, 9% other ethnicities | Advertent (but not inadvertent) exposure to body ideal images triggered eating by restrained eaters. Neither media exposure condition impacted their weight satisfaction |

| Bulik [24] | BN, NC | Whether alcohol consumption differed between food deprivation and no food deprivation conditions | Behavioural | 5 | F | M 25.6 ± 5.6 | Not stated | More alcohol consumed in non-deprived condition |

| Bulik [128] | BN | Examining the reinforcing value of cigarettes and food after food deprivation in female smokers with and without BN | Behavioural | 10 (4 BN) | F | 18–33 | Not stated | Increase in reinforcing value of food, and time spent working for cigarettes after deprivation in control but not BN women |

| Bulik [129] | BN, NC | Effect of coffee in BN and controls during food deprivation and no deprivation | Likert scale ratings, game responses to earn coffee | 10 | F | BN: 32.0 ± 6.1, NC: 21.7 ± 3.8 | Not stated | Those with BN consumed more coffee in deprivation condition versus control group |

| Bulik [130] | BN (BTS) | Salivation at presentation of food in BN sample, restrained eaters, and unrestrained eaters | SCID for DSM-III-R | 57 (19 BN) | F | BN: 27·7 ± 5·8 | Part of BTS sample | BN woman displayed significantly lower salivary reactivity than restrained or unrestrained eaters |

| Carter [131] | BN | Examining cue reactivity methodology | SCID, self-report on urge to binge/purge, assessor evaluated urge to restrict, heart rate, blood pressure |

7 (BN) 13 (Control) |

F | BN: M 26, NCM 28 | Not stated | Recommendations for cue reactivity assessment procedure are given, emphasising standardisation of measures, and participant-specific cues |

| Carter [132] | BN | Evaluated body image assessment and cue reactivity in women with BN in response to a range of cues | Silhouette method for assessing body image, BDI, EDI, self-report |

7 (BN) 8 (NC) |

F | 18–40 | Not stated | BN women rated bodies as larger, and had lower body image satisfaction versus NC women. Body satisfaction ratings were not affected by cue presentation. High-risk food cues were sufficient to elicit urges to binge in BN women |

| Carter [133] | BN | Information processing speed and cue reactivity in BN woman in response to cues | Stroop colour-naming tasks, BDI, DRS, EDI, Self-report measures on low mood, urge to eat/binge, confidence to resist this | 13 (6 BN) | F | 18–40 | Not stated | Specific cue types, as well as the way they were presented affected speed of information processing suggesting a more complex relationship than was anticipated |

| Gendall [134] | Cravers | Effect of meal macronutrient composition on subsequent behaviour and mood | Appetite and mood ratings (60 mm VAS) pre and post-test meals | 9 | F | 38–46 | Not stated | Consumption of protein-rich meals increases susceptibility to craving sweet-tasting foods in vulnerable women |

| Gendall [135] | Cravers | Meal induced change in tryptophan in relation to craving and binge eating | Blood sample assays | 9 | F | 34.9–50.4 | Not stated | Reduced plasma tryp:LNAA ratio (induced via high protein meal) reduced urge to binge |

| Hickford [136] | NC | Comparing restrained and unrestrained eaters' cognitions | BDI, Restraint scale (short), SCID for ED modules of DSM-III-R | 10 | F | 18–40 | Not stated | No difference in frequency of food cognitions between groups |

| Latner [137] | BED, BN | Comparing food intake between those ingesting high-carbohydrate or high-protein supplements | EDE, BDI-II, PRIME-MD | 18 | F | 34.78 ± 9.80 | Not stated | Protein supplement led to less binge-eating |

| Latner [138] | BED, NC | Whether energy density of meals affects intake in BED and NC | Behavioural data, EDE, EAT, DASS, BMI |

30 (15 BED, 15 NC) |

F | M 27.0 (SD 8.25) | 63.3% European, 10% Māori, 6.7% Pasifika, 6.7% Asian, 6.7% Indian, 6.7% other | Energy intake significantly lower in the low-ED condition than high-ED condition. BED participants report lower satiation. Decreasing energy density of food consumed may help satiation disturbances |

| Latner [139]* | BED, NC | Effects of two different food volumes (same total calories) on subsequent appetite and intake | Ratings (VAS, 5-point scale) for appetite and eating, food diary, food intake | 30 (15 BED, 15 NC) | F | M 27.07 (SD 8.24) | Not stated | Decreases in hunger, desire to eat, and loss of control were observed following higher volume food preloads. BED participants displayed greater desire and excitement to eat than controls |

| Stock [140] | NC | Body image relationship with body functionality versus body control | Big Five Inventory, Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Scale (INCOM), VAS for body image measures, self-objectification questionnaire (SOQ), RSES, food choice questionnaire, VAS for mood | 131 | F | 18–35 | Not stated | No increase in body satisfaction, but and lower self-objectification over time in body functionality group. Higher neuroticism associated with lower body satisfaction. Body image group participants reported lower self-esteem |

| Walsh [141]* | BN, NC | Examining neuroendocrine and neuropsychological functioning in individuals with eating disorders | BDI, EAT, blood testing, subjective ratings of physical symptoms | Study 1: 15 (NC), Study 2: 12 (NC), Study 3: 20 (12 NC, 8 recovered BN) | F | 19–37 | Not stated | Trytophan-free amino acid drink administration did not impact mood or food intake. Moderate dieting associated with alterations in brain serotonin function in women |

NC non-clinical, RS-CD Restraint Scale—Concern for dieting subscale, DIS Dietary Intent Scale, BMI body mass index, SCID Structured Clinical Interview for DSM, DRS Disability Rating Scale, EDI Eating Disorder Inventory, VAS Visual Analogue Scale, BDI Beck Depression Inventory, EDE Eating Disorder Examination, EAT Eating Attitudes Test, DASS Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale, SOQ Self-Objectification Questionnaire, RSES Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale

*Identifies that the record is a thesis

Table 4.

Cross-sectional research

| References | Population focus | Focus | Data collected | Sample n | Gender | Age | Ethnicity | Summary findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baxter [142] | BN, AN (TRH) | Mental health conditions among Māori participants in Te Rau Hinengaro | CIDI for DSM-IV | 2595 |

60% F 40% M |

16+ | 100% Māori (only Māori participants from TRH) | ED lifetime prevalence of 0.7% AN and 2.4% BN |

| Bensley [143]* | NC (OSSLS2) | Body image among adolescents and association with different lifestyle behaviours | Otago Students Secondary School Lifestyle Survey (OSSLS2): Subscales from the Food, Feelings, Behaviours, and Body Image Questionnaire (FFBBQ), BMI, DQI | 681 |

56% F 44% M |

15–18 | 74% NZ European, 9% Māori, 1% Pasifika, 7% Asian, 8% other | Females had higher scores on all subscales (figure dissatisfaction, fear of weight gain, dietary restraint, and concern about eating and weight), as did those who were overweight and obese. High levels of body dissatisfaction not limited to those who were overweight and obese) |

| Blackmore [144]* | NC | Explored self-induced vomiting after drinking alcohol in relation to eating disorder pathology among university students | EAT-26, MAST, Drinking Habits Questionnaire, BULIT-R, CES-D, AUDIT | 261 |

59% F 38% M |

17–35 | Predominantly European | For females, alcohol-related self-induced vomiting was associated with eating disorder pathology |

| Boyes [145] | NC | Healthy and unhealthy dieting behaviours in university couples | Perceived Relationship Quality Components Scale, RSES, BDI-II, WCBS, additional Likert scales | 114 |

50% F 50% M |

15–57 | Predominantly European | More body satisfaction among F with higher SE and lower depressive symptoms. More depressive symptoms and relationship dissatisfaction for men associated with more dieting and BD in F partners. M dieted more when F partners higher SE and fewer depressive symptoms |

| Brewis [146] | NC | Body image in Samoan participants living in Samoa and New Zealand | BMI, custom questionnaires | 226 |

55% F 45% M |

25–55 | 100% Samoan | Body dissatisfaction and slim ideals common, weight loss attempts and body perceptions not different between those above versus below BMI of 27 |

| Bushnell (1990) [147] | Population sample (CPES) | Bulimia prevalence in Christchurch population sample, oversampled for younger women | Diagnostic Interview Schedule | 1498 |

66% F 34% M |

18–64 | 93% European | Widespread disordered eating behaviours/attitudes, cohort effect for younger women |

| Chan [148] | NC | Relationship between perfectionism and ED symptoms in Chinese immigrants, and the role of ethnic identity | EDI, PANAS, MEIM, MCSDS | 301 |

59% F 41% M |

M 22.37 | 100% reported Chinese ancestry | Relationship between ED symptomatology and perfectionism mediated by cultural identity. Strong sense of belonging and attachment to Chinese culture appears to be protective |

| Dameh [149]* | AN | Evaluating insight, as well as factors that may affect this, in participants meeting DSM-IV criteria for anorexia nervosa | Markova and Berrios Insight Scale (MBIS), SAI, EAT-26 | 18 | F | 17–43 | Not stated | Impaired insight in those with AN was associated with features of illness, ED/behaviours and history of abuse |

| Durso [150] | NC | Testing weight bias scale and associations between self-directed weight bias and other factors | Weight Bias Internalisation Scale | 198 (1 NZ participant) | Not specified for NZ | Not stated for NZ | Not stated for NZ | Scale had good internal consistency and linked to other factors related to body image and ED |

| Fear [151] | NC | Self-reported disordered eating/attitudes in female secondary school students | BMI, EDE-2, BMI | 363 | F |

M 14.9 (SD 0.4) |

77% European, 16% Māori, 3% Samoan, 4% other | Most students wished to be smaller size, high prevalence of ED behaviours |

| Foliaki [152] | Population sample | Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Pasifika in New Zealand | CIDI | 2374 | 52% F, 48% M | 16 + | 100% Pasifika | 12-month prevalence 1.5%; lifetime ED prevalence 4.4% |

| Gendall [153] | NC | Exploring food cravings in young women within the community | DIGS, custom food craving questionnaire | 101 | F | 18–45 | 98% European | History of cravings common (58%) within this sample. Narrowing definition meant that fewer (28%) met criteria. Multiple core features more common for those with strong cravings |

| Gendall [154] | NC | Characteristics of individuals who reported cravings for food | DIGS, TCI, EDI | 101 | F | 23–46 | Not stated | Food cravings associated with alcohol abuse/dependence and also novelty seeking, high rates of ED symptoms |

| Gendall [155] | AN | Food cravings and intensity of craving in those with past history of AN and NC | DIGS, TFEQ, TCI | 101 | F | 35 ± 6 | Not stated | Greater proportion of those with previous AN reported strong and more intense cravings |

| Gendall [156] | NC | Can aspects of restrained eating be predicted using the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) | DIGS, TCI, TFEQ | 101 | F | 18–45 | Not stated | Low self-directedness related to higher TFEQ score, disinhibition, and hunger susceptibility. High self-transcendence related to higher TFEQ score and cognitive restraint |

| Gendall [157] | NC | Comparing those who crave food and binge eat versus those who crave and do not subsequently binge | Food | 223 | F | 18–46 | Not stated | Cravers who binged tended to have higher BMI, higher frequency of diagnosed BN, elevated dietary restraint, and lower self-directedness |

| Gibson [42] | NC | Body image scores for rugby union players | Body composition, custom version of Low Energy Availability Amongst New Zealand Athletes, EDI-3 | 26 | M | 19–28 | Not stated | High prevalence of disordered eating behaviours, disturbances in body image |

| Griffiths [28] | NC | Anabolic androgenic steroid use/contemplation and associations with factors including body dissatisfaction and ED symptoms in sexual minority men | Online survey: Self-report weight/height, sexuality, anabolic steroid use/consideration, MBAS-R, EDE-QS, BBQ |

1797 from Aus 514 from NZ |

99.1% M, 0.4% other (same sample in refs 24–26) |

18–78 years | Reported as Aus NZ and Non-Aus NZ | ED symptoms and dissatisfaction with muscularity and height more prevalent among those who use AAS, while dissatisfaction with body fat less common in this group |

| Griffiths [27] | NC (Griffiths et al. [28]sample) | Pornography use and body image, associated behaviours, and quality of life in sexual minority men | Online survey: self-reported weight and height, sexuality, MBAS-R, EDE-QS |

1797 from Aus 514 from NZ |

99.1% M, 0.4% other | 18–78 | Not stated for NZ | Increased pornography use was weakly associated with more body dissatisfaction and thoughts of anabolic steroids use |

| Griffiths [29] | NC (Griffiths et al. (2017) sample) [28] | Social media use and body image, ED symptoms, and steroid use contemplation in sexual minority men | Online survey: self-reported social media/dating use, height/weight, sexuality, use/thoughts of anabolic steroids, MBAS-R, EDE-QS |

1797 from Aus 514 from NZ |

99.1% M, 0.4% other | 18–78 | Not stated for NZ | Social media use positively associated with body dissatisfaction, ED symptoms, and thoughts of anabolic steroid use. Some associations strongest for image-centric platforms |

| Hechler [158] | Clinicians | Assess clinicians understanding of role of physical activity in AN—and describe assessment and management strategies | EDSCS (Eating disorder specialist/clinician survey) | 33 | Not stated | Not stated | Reported as Aus/NZ | The majority of specialists consider physical activity to be important in EDs, however those from an Asian background considered it to be minor in comparison to other nationalities |

| Hickman [159]* | BN, NC | Looking at relationships and associated attachments in those with and without BN, within a sample of university students | EDI, Close Relationship Scale, TFEQ, Relationship Satisfaction Scale | 123 (unclear how many with BN symptoms) | F | 18–40 | Not stated | More anxious attachment and dieting in participants with bulimia |

| Hudson [160]* | NC | Body dissatisfaction, BMI, esteem, eating attitudes | EDE, BSQ, RSES, BMI | 36 | F | 17–55 |

67% NZ European, 8% Māori, 25% Other |

Elevated BMI linked to higher body dissatisfaction |

| Jenkins [161]* | NC | Eating disorder symptomatology among females in NZ of Chinese and other ethnicities | EAT-40, Eating Disorder Belief Questionnaire, additional custom questions, Perceived Sociocultural Pressure Scale, SEED, ratings of body image figures | 116 | F | 18–47 | 34% Chinese, 5% Taiwan, 49% NZ European, 8% NZ Māori, 1% Pasifika, 3% Other Ethnicities | More body image dissatisfaction and fear of weight gain in Chinese group. Similar pressure to be thin between groups |

| Jospe [162] | NC (SWIFT) | Whether association between weight/diet monitoring influenced eating disorder symptoms | EDE-Q, self-reports of ED behaviours | 250 | 62% F, 68% M | < 18 | 176 European, 18 Māori, 7 Pasifika, 5 Asian | Self-monitoring did not increase ED symptoms |

| Kessler [1] | TRH (BED data not previously reported) | Assessing prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | 24124 (7312 NZ) | Not specified for NZ | > 18 | Not stated | Lifetime prevalence estimates of BED are higher than BN, fewer than half of lifetime BN or BED cases receive treatment |

| Kessler [26] | BED, BN (TRH) | Compared impairment and role attainment (e.g. employment) between BED and BN | CIDI, WHO-DAS | 7312 from NZ (not included in occupation and earnings assessment) | Not specified for NZ | 18–98 | Not stated | Effects on role attainments similar for BN and BED. F less likely to be currently married, M less likely to be currently employed. Both more higher odds of work disability and more days of work impairment |

| Kokaua [163]* | BN, AN | Includes prediction of eating disorder prevalence among Cook Islanders in New Zealand | NZMHS, MHINZ | How to report? | How to report? | 16+ | Cook Island | Any eating disorder 1.4% 12 months prevalence (unadjusted) or 1.1% adjusted. Ethnic differences in eating disorders even after adjustment |

| Latner [164] | BED, BN, AN | Comparing quality of life ratings in those with subjective versus objective binge eating | EDE-Q, SF-36, BDI-II | 53 | F | M 26.30 (SD 8.98) | 94% European, 2% Asian, 2% Māori, 2% Pasifika | Impaired quality of life for subjective binge episodes and compensatory behaviours. Also accounted for 27% of physical QoL variance |

| Latner [165] | NC | Associations between body checking/avoidance, quality of life (QoL) and disordered eating | BCQ, BIAQ, BMI, SF-36, EDE-Q, BDI-II | 214 | F |

M 26.3 (SD 8.98) |

86% European, 8% Asian, 52% Māori | Both body checking and avoidance associated with lower QoL and higher ED symptoms |

| Latner [166] | BED, BN, AN, EDNOS | QoL impairment due to features of EDs (e.g. eating concern, restraint, vomiting, excessive weight concerns) | EDE-Q, The Medical Outcomes Short-form Health Survey (SF-36), BDI-II |

53 ED 212 NC |

F | 17–65 | 88% European, 7% Asian, 5% Māori | More EDE-Q features, particularly shape/weight concerns, were predictive of poorer QoL |

| Lau [167]* | NC (SuNDiAL) | Desire to lose weight and methods of losing weight, including unhealthy weight loss methods, among adolescents | Weight attitudes and motivations for food choice questionnaire, custom questions about body image and weight loss intentions and methods | 370 | 66% F, 34%M | 15–18 | 72% European, 14% Māori, 13% Asian, 2% Pasifika | High prevalence of weight loss intentions. Weight loss methods more common in females |

| Leydon [168] | NC | Eating habits among jockeys | EAT, food diaries, menstrual status, DEXA scan, body composition, anthropometry | 20 |

70% F 30% M |

Not stated | Not stated | Osteopenia and weight control efforts common among sample of jockeys |

| Linardon [169] | NC, BED, BN | Participant views of digital interventions for treatment and prevention of eating disorders | Custom questionnaires | 722 (133 from Aus/NZ) |

95% F 5% M |

M 30.25 (SD 8.29) | 77.1% European, 0.4%% African American, 8.6% Hispanic, 10.4% Asian, 0.6% Pasifika Island, 2.9% other | Pros and cons identified, cons included concerns about privacy and accuracy of data |

| Lucassen [170] | NC (YHS) | Comparing body size, weight, nutrition, and activities in sexual and gender minorities (SGM to controls | Custom survey re weight control behaviours, BMI | 7769 |

56% F (incl. 312 S/GM females) 45% M (incl. 150 S/GM males) |

13–18 | 49% European, 20% Māori, 13% Pasifika, 12% Asian, 6% other | More issues with nutrition, unhealthy weight control, and inactivity among sexual and gender minorities |

| Madden [7] | NC | Association between intuitive eating and BMI, and eating behaviours among less intuitive eaters | Intuitive Eating Scale, BMI (self-reported weight/height), Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity, additional selected questions of menopausal status, binge-eating, food intake, and rate of eating | 2500 | F | 40–50 | 83% European, 11.4% Māori, 3.0% Pasifika, 85% Asian | Intuitive eating inversely associated with BMI. Partial mediation by binge-eating |

| Maguire [171] | AN | Ability to predict length of inpatient treatment Australasian clinical data | Clinical data | 154 | 98% F |

M 21.2 (SD 7.2) |

Not stated | Difficulty in predicting length of stay, with only two factors (length of stay, 2–3 previous admissions) independently contributing to this |

| McCabe [172] | NC | Three studies comparing body image of those within five different countries and cultures (Fijian, Indo-Fijian, Tongans living Tonga, New Zealand Tongan, European Australians) | Interviews and questionnaires about eating behaviours and physical activity, perceptual distortion task | Study 1: 240; Study 2: 3000; Study 3: 300 | 50% F, 50% M | 12–18 |

Study 1: 48 from each cultural group, Study 2: 600 from each cultural group, Study 3:100 from each Fijian cultural group and European Australians |

Body image, eating, and physical activity influenced by socio-cultural environment |

| McCabe [173] | NC (Pacific OPIC Project) | Environmental influences on body change strategies within different cultural groups | Body Image and Body Change Questionnaire | 4904 (461 NZ) | 48% F, 52% M (NZ 62% F, 38% M) | 12–18 | Tongan | Differing messages across and within cultural groups |

| Miller [174] | NC | Body perception in relation to media consumption and societal ideals | The Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire, FRS, Media Time Use, INCOM | 181 |

66% F 34% M |

17–30 | 84% European, 7% Māori, 3% Asian, 2% other | Greater discrepancy between ideal and perceived current body figures for women. Greater thin ideal internalisation for women. Awareness and internalisation of thinness norms predicted body perceptions for women but not men |

| Moss [175]* | AN, EDNOS | Body dissatisfaction and associated factors in adolescents with eating disorders | EDI-3, CAPS, PSPS, DASS-21 |

40 (13 AN, 7 EDNOS) 20 NC |

F | M 15.75 (SD 1.52) |

ED: 80% European 10% Māori, 10% other CT: 90% European, 10% Māori, 0% other |

Higher maladaptive perfectionism and anxiety linked to BD, but didn’t interact as predictors of BD in ED group |

| Muir [176]* | AN, NC | Whether women with AN differed from low weight women without AN in recognising emotions | Performance on facial emotion recognition test (reaction speed and accuracy) | 33 | F | 18–55 | AN: 41.7% NZE, 8% Maori, 4 “other”. NC: 90.5% NZE, 2 British, 1 Russian | Shorter response time for AN group, no difference in accuracy measures |

| Mulgrew [177] | NC | Weight control behaviours and associated factors in young people | BAQ, MBAS-R, PHQ, modified WCBS, BMI, weight management questions | 1082 |

75% F 25% M |

18–30 | 79% NZEO | More weight control behaviours among females. Feelings of fatness a key predictor of weight control |

| Ngamanu [178]* | NC | Compared levels of body image dissatisfaction and eating pathology in Māori and Pakeha women, also examining whether the ethnic attachment of participants was associated with the body image | BMI, MEIM, FRS, EAT-26 | 100 | F | 18–50 + | 34% Pakeha, 66% Māori | Body image dissatisfaction and eating pathology did not differ between groups. Level of ethnic attachment also did not impact body image satisfaction |

| Browne [179] | BN, AN (TRH) | Lifetime prevalence/risk of psychiatric disorders in the New Zealand population | Survey | 12, 992 |

57% F 43% M |

16+ | 20% Māori, 17% Pasifika, 63% Other (Part 1), 22% Māori, 18% Pasifika, 60% Other (long-form sample) |

Any ED 1.7%CI 1.5, 2.1) LT prevalence AN 0.6 (CI 0.4,0.8): BN 1.3 (1.1,1.5): Females: 2.9 (CI 2.3,3.5); Males 0.5 (CI 0.3, 0.9) |

| O'Brien [6] | NC | Body image and self-esteem in physical education (PE) university students | Demographic questionnaires, self-reported BMI, BES, EAT-26, global self-esteem scale from the SDQIII | 228 | F |

PE 18: 34 ± 0.64, Psychology 18: 46 ± 0.78, Year 3 PE 21:.0 ± 1.18, Year 3 Psychology20: 9 ± 1.06 |

Not stated | Year 3 PE students had lower self-esteem and more disordered eating |

| O'Brien [180] | NC | Psychosocial characteristics among those in a weight loss programme | Custom questions on reasons, MBSRQ, single item self-esteem scale | 106 |

86% F 14% M |

M 41.9 (SD 10.8) |

Not stated | Key reasons for wanting to lose weight were mood, appearance, and health. Poorer self-image/self-esteem for those citing mood reasons |

| Overton [181] | Clinical | Comparing emotional experience of women with EDs to NC controls | EDI-2, YSQ-SI, DES-IV | 130 (30 ED) | F |

Cases: M 28.1 NC M 23.8 |

Not stated | Use of disordered eating behaviours to manipulate both positive and negative emotional states, should be recognised as an important maintenance factor |

| Reynolds [182] | Clinicians | Whether health professionals felt orthorexia should be recognised as an eating disorder | Custom online survey and qualitative text boxes | 52 |

96% F 4% M |

41.2 ± 11.9 | Not stated | Most clinicians (71%) felt that orthorexia should be recognised as a distinct ED |

| Robertson [183]* | NC | Associations between body image, self-esteem, and peer and romantic relationships | Body Image and Body Change Questionnaire, Physical Attractiveness Scale, Body Image Behaviour Scale, Social Physique Anxiety Scale, Physical Appearance Comparison Scale, RSES, Self-Description Questionnaire III, Perceived Relationship Quality Components Scale | 91 | 80% F, 20% M | 17–69 | Not stated | Positive relationship between body-image and self-esteem, and between body image and quality of romantic relationships. Positive relationship between self-esteem and relationships (peer and romantic). Body image predicted self-esteem and quality of peer-relationships Self-esteem predicted romantic relationship quality |

| Rodino [184] | Clinicians | Fertility specialists' knowledge and practices relating to eating disorder | Adapted online questionnaire | 106 | 51% F, 49% M | 25 + | Not stated | Knowledge around relevant symptoms of eating disorders, but uncertainty around ED detection. Many not satisfied with training in this area, or not confident in ability to recognise symptoms. Large majority indicated need for further education/guidelines |

| Rosewall [185] | NC | Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in girls | NZSEI, EAT-26, Stunkard Body Figure Drawings, EDI, CAPS, RSES, Sociocultural Influences on Body Image and Body Change Questionnaire (Perceived Pressure to Lose Weight subscale), PANAS, POTS | 231 | F | 14–18 | 73.7% NZ European, 10.3% Māori, 5.6% Asian, 2.6% Pasifika and 3% Other | Risk factors for higher levels of body dissatisfaction were perfectionism, perceived media pressure, and low self-esteem |

| Rosewall [186] | NC | Exploring moderations of association between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviours | NZSEI, ChEAT, Collins Body Figure Perceptions, EDI, CAPS, RSE, PANAS-C, Sociocultural Influences and Body Change Questionnaire, POTS (weight-based teasing subscale) | 169 | F | 10–12 | 84.0% NZ European, 11% Māori, 6% Asian, 2% Pasifika, 1% Other | Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating association were moderated by personal (e.g. perfectionism, self-esteem) and environmental factors (e.g. teasing, perceived media pressure) |

| Rosewall [187] | NC | Psychopathology factors related to links between BMI and body dissatisfaction, and between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating | BMI, BSQ, BIA, BES, EAT-26, PAI | 186 | F | 18–40 | 78.9% NZ European, 13.3% Asian/part Asian, 3.0% Māori, 1.2% Pasifika Island 3.6% other | Reporting lower BD (than would be predicted by BMI), and less disordered eating (than would be predicted by BD) was linked to lower levels of anxiety/depression and higher mood stability |

| Shephard [188]* | NC | Influence of family experiences related to food and self-compassion on the association between appearance ideals and body dissatisfaction | SATAQ (Revised—Female Version), BSQ, family Experiences Related to Food Questionnaire (FERFQ), self-compassion scale (SCS) | 106 | F | 18–48 | 85.8% NZ European, 4.6% NZ European and 'another ethnicity', 3.8% Chinese, 1.9% Māori, 3.8% another ethnicity | Family food related experiences and self-compassion appear to be protective, moderating relationship between body dissatisfaction and thin ideal internalisation |

| Slater [189]* | NC | Energy intake, activity, and disordered eating behaviours in recreational athletes | EDI-3, LEAFQ | 170 |

64% F 36% M |

18–56 | Not stated | Low energy availability (LEA) common but no risk of ED for most of those with LEA |

| Strang [190]* | Restrained eaters | Responses to Stroop test words about food, weight, and shape by restrained eaters versus unrestrained eaters | Stroop test, RS, STAI, BDI | 55 (21 restrained eaters) | Only F after initial phase | Restrained: 24.33 (9.80), unrestrained: 21.85 (5.64) | Not stated | No group differences, but may have been due to minimal symptomatology in restrained eating group versus comparison groups |

| Talwar [12] | NC | Body image and body dissatisfaction among Māori and non-Māori participants | Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure, BIA-G, BES | 45 | F |

Māori: M 19.8 (SD 1.2), European: M 19.0 (SD 1.2) |

50% Māori 50% European |

Lower concern about weight among Māori. Stronger Māori ethnic identity was associated with lower weight concern |

| Utter [5] | NC | Identifying 'red flag' behaviours for unhealthy weight loss | Youth'07 survey | 9107 |

46% F 56% M |

13–18 | Māori, European, Pasifika, Asian (% not stated in this paper) | Meal skipping and fasting are 'red flag' behaviours associated with poor mental wellbeing |

| Vallance [191] | NC | ED symptoms and health related quality of life | SF-36, EDE-Q, EDI-2, BSQ, BCQ, BIAQ, BDI-II, BSI | 214 | F | 17–65 | 85% European, 7.5% Asian, 6.1% Māori | DE and BD linked to lower quality of life |

| Vaňousová [192] | NC | Evaluating validity of the Eating Concerns (EAT) scale from the MPPI-3 | MPPI-3 (specifically EAT scale), EPSI, EDE-Q, EDDS, BES, BI_AAQ | 396 |

79% F 21% M |

17–51 | 91% European, 12% Maori, 8% Chinese, 4% Indian, 2% Pasifika (some participants more than one) | Scores from new MPPI-3 EAT scale seem promising as a screening measure for eating pathology |

| Wells [20] | BN, AN (TRH) | Prevalence and severity of different disorders, including eating disorders, within NZ. Oversampled for Māori and Pasifika | CIDI | Short form: 12, 992, long form: 7435 | 57% F, 43% M | 16+ | 20% Māori, 17% Pasifika, 63% Other (Part 1), 22% Māori, 18% Pasifika, 60% Other (long-form sample) | Any eating disorder 1.7% lifetime prevalence, 0.5% 12-month prevalence |

| Wells [193] | BN, AN (TRH) | Severity and interference with life for mental health conditions among NZ sample | CIDI, Sheehan Disability Scale | Part 1: 12,992, part 2: 7435 | 57% F, 43% M | 16+ | 20% Māori, 17% Pasifika, 63% Other (Part 1), 22% Māori, 18% Pasifika, 60% Other (long-form sample) | Prevalence for EDs 0.5% in last 12 months |