Abstract

Background

End stage renal disease (ESRD) is a major health concern and a large drain on healthcare resources. A wide range of payment methods are used for management of ESRD. The main aim of this study is to identify current payment methods for dialysis and their effects.

Method

In this scoping review Pubmed, Scopus, and Google Scholar were searched from 2000 until 2021 using appropriate search strategies. Retrieved articles were screened according to predefined inclusion criteria. Data about the study characteristics and study results were extracted by a pre-structured data extraction form; and were analyzed by a thematic analysis approach.

Results

Fifty-nine articles were included, the majority of them were published after 2011 (66%); all of them were from high and upper middle-income countries, especially USA (64% of papers). Fee for services, global budget, capitation (bundled) payments, and pay for performance (P4P) were the main reimbursement methods for dialysis centers; and FFS, salary, and capitation were the main methods to reimburse the nephrologists. Countries have usually used a combination of methods depending on their situations; and their methods have been further developed over time specially from the retrospective payment systems (RPS) towards the prospective payment systems (PPS) and pay for performance methods. The main effects of the RPS were undertreatment of unpaid and inexpensive services, and over treatment of payable services. The main effects of the PPS were cost saving, shifting the service cost outside the bundle, change in quality of care, risk of provider, and modality choice.

Conclusion

This study provides useful insights about the current payment systems for dialysis and the effects of each payment system; that might be helpful for improving the quality and efficiency of healthcare.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-022-08974-4.

Keywords: Payment system, Reimbursement system, Dialysis, Efficiency, Healthcare

Introduction

When the chronic kidney diseases (CKD) progress to the end stages, usually a renal replacement therapy (RRT) is required to improve the survival and quality of life [1, 2]. Dialysis is the most prevalent RRT, that is provided in two ways including hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD) [3]. Dialysis is a relatively expensive procedure that cause significant costs to patients or healthcare systems [4, 5]. The cost of dialysis is expected to increase significantly in the future due to the rapid increase in the population age and rate of ESRD [6]. This might lead to major challenges for health systems to afford the cost of the dialysis; therefore it is very important to find and use more efficient payment systems.

Dialysis reimbursement system has important effects on different aspects of the care, including modality choice [7], quality of care [8], quantity of services [9, 10], costs [8, 9, 11, 12], obtained results, and value [13]. Reimbursement systems are classified as prospective and retrospective, based on the time the bills are calculated. In prospective payment systems (PPS) the bills are determined at the time of admission. In retrospective payment systems (RPS) the bills are calculated based on the claimed costs. It is argued that the prospective systems are better in controlling costs [14]; however, some countries use a mix of payment systems to reach better outcomes [15].

Current evidence shows that higher cost of the dialysis services does not necessarily lead to better outcomes; sometimes might even result in lower quality of care [16, 17]. Therefore several health systems have tried to make changes or reforms in the dialysis payment systems to improve the efficiency and quality of care. Wide range of payment systems including the value-based payment systems are used for reimbursement of dialysis [18–20]. Different methods have various strengths, weaknesses and effects; and usually a combination of methods are used in each country depending on the country context and situation.

Although effects of the payment systems are theoretically specified, but context specific variables can provide variation in the effects of each payment system. Additionally, the different implementation and administration ways induces different effects. Each country has its’ own payment system, which brings it many lessons and experiences. Studying such experiences will provide in-worth information for internal managers and planners also provide insights for other countries’ policymakers.

There are plenty of studies on the dialysis payment systems in different countries, each discussing the payment systems from a specific point of view, which is the starting point in the present scoping review. But no comprehensive study was found, which map the dialysis payment systems and related reforms around the world, assess their details, and especially their experienced effects.

The aim of this study is to identify the main methods that are currently used for reimbursement of dialysis in the world, and the reported effects of each method by a scoping review of the published studies. We present this article in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR reporting checklist [21].

Methods

A scoping review was performed to identify the payment systems for dialysis and their effects using the 5-step approach introduced by Arksey and O’Malley [22], as explained below.

Identifying the research question

Our objective is to answer these research questions:

What are the main dialysis payment systems used by different countries?

What studies have been undertaken on the effects of the dialysis payment systems and policies around the world?

What are the outcomes of the payment methods and policies?

Identifying the relevant studies

PubMed and Scopus databases were searched from 2000 until April 7, 2020, and google scholar search engine was searched in June 8, 2021. In setting the search strategy, relevant search terms and medical subject headings (MeSH) were identified through the National Library of Medicine Database and reviewing related papers. An appropriate search strategy was developed for each database using these key words: “end stage renal disease”, “end stage kidney disease”, ESRD, ESKD, dialysis, payment, reimbursement, financing, “pay for performance”. Search strategy for each database is available in the appendix (Table S1).

Study selection

Empirical studies that had English report and their full text were available were included. Review articles that provide extra information about the implementation of payment systems for dialysis including information about the policies or changes related to dialysis payment, and their effects were included. Observational studies that simulated or anticipated the “potential effects” rather than the “real or experienced effects” of the dialysis payment systems or policies were also included. We excluded studies which full text were not accessible, editorial and seminar articles, and non-English papers.

Charting the data

The reviewers extracted the data from studies into a form, including:

Authors, title, place, publication year, study subject, study outcomes, study design, main findings.

Collating, summarizing and reporting the findings

We tabulated the studies and identified the payment systems for dialysis in different countries, and the main effects of the payment systems or policies. Data were extracted using a data extraction form. The data was extracted by two independent persons and was checked by a third person. Finally, a qualitative thematic data synthesis approach was used to summarize the reported results.

Results

Search results

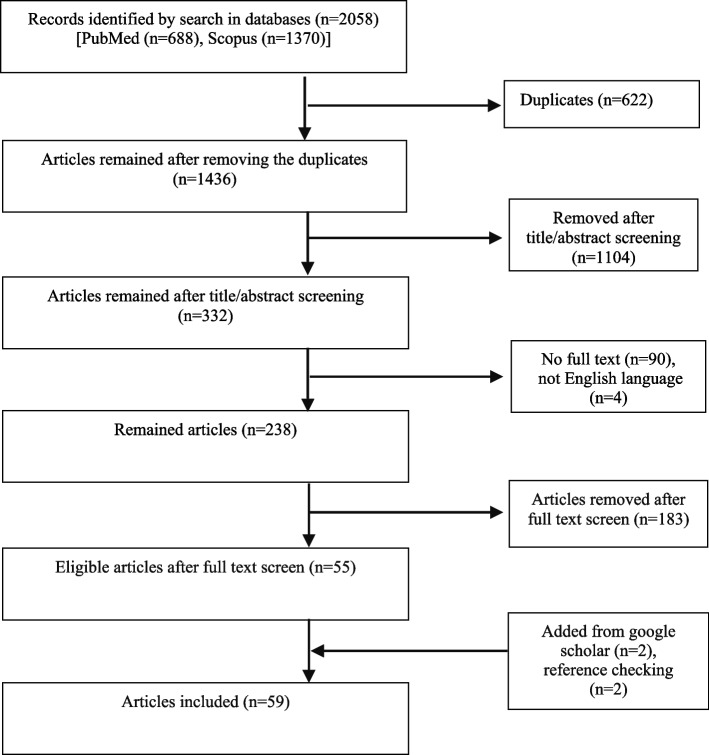

A Total of 2058 records were identified from the databases. Of the 2058 records, 238 were selected for full-text screening. One hundred eighty-three articles were excluded in full-text review, since they did not meet our inclusion criteria:

Fifty papers were editorial, commentary, seminar, news, letter, perspective. One hundred thirty-one articles were not focusing on the scope of the present review, of which 49 articles were about wide aspects of care (medication, predictors of modality selection, care quality, non-dialysis treatments), 26 articles were about cost/economic analysis, 18 articles were on the case-mix adjustments and risk analysis, 15 articles were on the quality metrics, 14 documents were on regulations, 9 articles explained a concept or history of policies. Two articles were duplicate. Finally, 59 articles were included (Fig. 1). A summary of the studies was provided in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Results of searches and study selection

Table 1.

Summary of the studies included in the review

| ID (year) | Country | Study subject | Study outcomes | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang (2014) [23] | Taiwan | change from FFSa to ODBGb | outpatient visits, medication use, access to dialysis services, bundle of services doctors were providing |

“Access to dialysis services” and the number of “dialysis visits” was not affected. The bundle of services provided to dialysis patients during their dialysis visit was changed. The cost of antihypertensive drugs during the “dialysis visit” reduced, which increased “non-dialysis visits” with the prescription of antihypertensive drugs. |

| Trachtenberg (2020) [24] | Alberta (Canada) | increases in physician remuneration for PDc | PD use (90 days after dialysis initiation) | There was no statistical evidence of an increase in PD use. |

| Wang (2016) [25] | USA | the 2011 PPSd, and the FDA change in ESA labels | Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), hospitalized congestive heart failure (H-CHF), venous thromboembolism, transfusions | The risks of MACE and death did not change; the risk of stroke reduced, and the rate of transfusions increased. |

| Spoendlin (2018) [26] | USA | the 2011 PPS | IVe vitamin D use | totally implementation of PPS associated with reduction in IV vitamin D use |

| Hasegawa (2011) [27] | Japan | rHuEPO bundled reimbursement policy | Hgbf levels, rHuEPO use, IV iron use | This policy was associated with reduced rHuEPO doses, increased IV iron use, and stable Hgb levels. |

| Mentari (2005) [16] | USA | the 2004 reformg | Visits, HRQoLh, quality of care (Kt/Vi, albumin level, Hgb level, phosphorus level, calcium level, hemodialysis catheter use, ultrafiltration volume, shortened or skipped treatments, hospital admissions, hospitalization days) | Visits increased. There were no important changes in Kt/V, levels of albumin, Hgb, phosphorus, calcium, and HDj catheter use, ultrafiltration volume, shortened or skipped treatments, hospital admissions, hospitalization days, or HRQoL, including patient satisfaction. |

| Brunelli (2013) [28] | USA | the 2011 PPS | PD use, medication use, Hgb level, PTHk level, transfusion rates | Use of cinacalcet, phosphate binders, and oral vitamin D increased. IV vitamin D decreased. ESA use decreased. PTH levels increased. Hgb level decreased. PD increased. Transfusion increased. |

| Chang (2011) [29] | Taiwan | ODBG | outpatient/inpatient/emergency room utilization by the ESRD patients | outpatient utilization by the ESRD patients increased. No change in emergency room and inpatient utilization occurred. |

| Erickson (2016) [30] | USA | the 2004 reform | home dialysis | Home dialysis reduced, especially in larger dialysis facilities compared to smaller facilities. |

| Haarsager (2017) [31] | Queensland (Australia) | The Queensland’s incentive paymentsl | PD as first modality, AVF/AVGm rate at first HD | commencement of dialysis with PD or an AVF/AVG in 2011–12, when pay-for-performance applied, didn’t change. It improved in the subsequent 2 years, which may be due to a lag effect. |

| Erickson (2017) [32] | USA | the 2004 reform | hospitalizations, rehospitalizations | All-cause hospitalization or rehospitalization didn’t change, but slight reductions occurred in fluid overload hospitalization and rehospitalization. |

| Erickson (2014) [9] | USA | the 2004 reform | visit, mortality, transplant waiting list, costs | Dialysis visits and Medicare costs increased with no evidence of a benefit on survival or kidney transplant listing. |

| Zhang (2017) [33] | USA | the 2011 PPS | PD use | PD usage increased. Small dialysis organizations and nonprofit organizations appeared to increase use of PD faster compared to large dialysis organizations and for-profit units. |

| Hirth (2013) [12] | USA | the 2011 PPS | medication use, PD use, cost | Less expensive medications were substituted for more expensive types (e.g., vitamin D products, EPO use reduced, iron products increased). Drug spending overall decreased. PD usage increased. |

| Desai (2009) [34] | USA | the 2011 PPS | Perceived frequency and effect of cherry picking | Three-quarters of respondents reported that cherry picking occurred “sometimes” or “frequently.” All cherry-picking practices caused moderate to large effects on outcomes. |

| Wang (2018) [35] | USA | the 2011 PPS | facility provision of PD | PD provision increased. |

| Young (2019) [36] | USA | the 2011 PPS | discontinuation of PD, death | The risk of PD discontinuation fell. No adverse effect on mortality. |

| Sloan (2019) [37] | USA | the 2011 PPS | modality switches, PD use | PD usage increased. PD-to-HD switches decreased, HD-to-PD switches increased. |

| Norouzi (2020) [38] | USA | the 2011 PPS | dialysis facility closures | The PPS was not associated with increased closure of dialysis facilities. |

| Kleophas (2013) [39] | Germany | weekly flat rate payments and Quality Assurance (QA) system | four quality parameters (Treatment time, spKt/V, dialysis frequency, and Hgb) | Short treatment times (less than 4 h) and low Kt/V (below 1.2) reduced after implementation of QA. The frequency of prescribed HD sessions < 3 per week remained low. Hgb levels improved. |

| Spiegel (2010) [40] | USA | several recent eventsn | Hgb level | Hgb > 12 decreased and Hgb < 10 increased (mean Hgb level decreased), while target level is 10 < Hgb < 12 |

| Monda (2015) [41] | USA | the 2011 PPS | ESA use, medication use, laboratory parameters, hospitalization events, and mortality | EPO use and mean Hgb level reduced. |

| Swaminathan (2015) [10] | USA | the 2011 PPS | ESA use | Use of ESAs reduced in patients who may not benefit from these agents. |

| Wetmore (2016) [42] | USA | the 2011 PPS | RBC transfusions, Medicare-incurred costs, sites of anemia management | transfusion increased. Site of care for transfusions have shifted to emergency departments or during observation stays. EPO dose declined. IV iron use decreased. a partial shift occurred in the cost and site of care for anemia management from dialysis facilities to hospitals |

| Fuller (2016) [11] | USA | the 2011 PPS | ESA use, IV iron use, Hgb level | From 2010 to 2013, substantial declines in ESA use and Hgb levels occurred in the United States but not in other DOPPS countries. Iv iron doses in the United States remained fairly stable. |

| Pirkle (2014) [43] | USA | the 2011 PPS | Hgb level, compliance | Hgb levels were stable over the 5 quarters of the study. Patient compliance with attendance for all scheduled home training unit visits was 84% (high). |

| Lin (2017) [44] | USA | the 2011 PPS | home dialysis use | Home dialysis increased, in both Medicare and non-Medicare patients. The training add-on did not associate with increases in home dialysis use. |

| McFarlane (2010) [45] | 12 DOPPS countrieso | ESA and Hgb trends before 2007 CMS policy | Hgb level, ESA use | ESA usage rose except in Belgium. Hgb levels increased except in Sweden. These trends are independent of the reimbursement. But in the United States financial incentives increased use of these agents. |

| Thamer (2015) [46] | USA | the 2011 PPS | EPO use, hematocrit level | EPO usage, dosing and achieved hematocrit levels were declined after PPS. |

| Mendelssohn (2004) [47] | Ontario (Canada) | the capitation fee in 1998 | dialysis modality rates | PD use continued to decline for 2 years, and then began to increase. |

| Hornberger (2012) [48] | USA | the 2011 PPS | modality choice | It caused increased use of PD but continued to discourage use of home HD. |

| Pisoni (2014) [49] | USA | the 2011 PPS | vascular access use | AVF use increased, while catheter use declined (from 2010 to 2013) |

| Tentori (2014) [50] | USA | the 2011 PPS and recent guidelines | 1-serum PTH, total calcium, and phosphorus levels; 2-mineral and bone disorder (MBD) related treatments, including IV and oral vitamin D analogues, cinacalcet, and phosphate binders | Upper limits of targets for PTH and calcium levels increased, while phosphorus targets remained unchanged. No changes were in IV vitamin D or cinacalcet prescription. Many facilities switched IV vitamin D preparation from paricalcitol to Doxercalciferol during this period. Phosphate binder use increased. |

| Park (2015) [51] | USA | integration of Part D renal medications into the bundle | Oral phosphate binder medication budget impact | The phosphate binder costs increased. |

| Pisoni (2012) [52] | USA | from August 2010 to August 2011 | EPO use, Hgb levels, IV iron use, serum ferritin and PTH levels | epoetin dose and Hgb levels declined. IV iron use, serum ferritin levels, and PTH levels increased. |

| Vanholder (2012) [53] | Seven countriesp | dialysis reimbursement in 7 countries | NA | Bundle of services and incentive programs in dialysis payment system of each country were explained. |

| Ponce (2012) [54] | Portugal | Portuguese dialysis reimbursement | NA | transitioning from a FFS reimbursement to a capitation system with quality indicators (P4P) |

| Maddux (2012) [55] | USA | the 2011 PPS (first year) | patient care | The impact on clinical care and patients is substantial. |

| Robinson (2013) [56] | USA | the 2011 PPS, the DOPPS practice monitor | NA | the DOPPS practice monitor provides timely representative data to monitor effects of the expanded PPS on dialysis practice. |

| Golper (2011) [57] | USA | the 2011 PPS | Home dialysis | It may encourage home dialysis. |

| Wish (2009) [58] | USA | the 2011 PPS | EPO use, IV iron use, Hgb level | The reform’s relevance to anemia management is indisputable. |

| Naito (2006) [59] | Japan | Japanese dialysis reimbursement | Modality selection | HD replaced by more efficient treatment options. |

| Swaminathan (2012) [60] | USA | The U.S. dialysis reimbursement changes until 2011 | Cost | It is uncertain whether bundled payments can stem the increase in the total cost of dialysis. |

| Rivara (2015) [61] | USA | The U.S. recent dialysis payment reforms | Home dialysis use (PD and HHD) | The utilization of PD increased. Utilization of HHD has also grown, but the contribution of the expanded PPS to this growth is less certain. |

| Fuller (2013) [62] | USA | the 2011 PPS | Anemia Management | Overall, changes in anemia management were substantial in 2011 but relatively stable by mid to late 2012. |

| Piccoli (2019) [63] | NA | Dialysis Reimbursement models | Clinical choices | Each reimbursement model leads to especial outcomes. |

| Dor (2007) [15] | 12 DOPPS countries | dialysis reimbursement systems | NA | comparative review of 12 countries shows alternative models of incentives and benefits. |

| Durand-Zaleski (2007) [64] | France | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA |

pay for medical center: global in public hospital, FFS in private hospital (it is moving toward activity-based reimbursement) /pay for nephrologist: Salary (in public hospitals), FFS (in private clinics) |

| Pontoriero (2007) [65] | Italy | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA | pay for medical center: FFS (bundled fee), pay for nephrologist: salary |

| Nicholson (2007) [66] | England and Wales | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA | pay for medical center: global budget through prospective payments (service level agreements) or fee for service (per outpatient HD treatment), pay for nephrologist: FFS, salary |

| Luño (2007) [67] | Spain | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA | pay for medical center: FFS (bundled fee), pay for nephrologist: salary |

| Fukuhara (2007) [68] | Japan | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA | pay for medical center: FFS (bundled fee), pay for nephrologist: salary |

| Kleophas (2007) [69] | Germany | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA | pay for medical center: capitation, FFS (for individual providers), pay for nephrologist: FFS |

| Wikström (2007) [70] | Sweden | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA | pay for medical center: global budget, pay for nephrologist: salary |

| Ashton (2007) [71] | New Zealand | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA | pay for medical center: global budget, pay for nephrologist: salary |

| Manns (2007) [72] | Canada | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA | pay for medical center: global budget, pay for nephrologist: FFS |

| Hirth (2007) [73] | United States of America | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA | pay for medical center: capitation, pay for nephrologist: capitation, FFS (for separately billable services) |

| Van-Biesen (2007) [17] | Belgium | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA | pay for medical center: capitation, pay for nephrologist: FFS |

| Harris (2007) [74] | Australia | Dialysis Reimbursement | NA | pay for medical center: currently global annual budget (they are going to a move toward capitation payment for fixed costs and a case payment for variable costs (per dialysis episode)), pay for nephrologist: FFS |

a Fee for service

b Outpatient dialysis global budget (ODGB) payment

c Peritoneal dialysis

d The 2011 Prospective Payment System (PPS) reform. It introduced some core services as the expanded bundle, and case-mixed indicators for payment adjustments

e Intravenous

f Hemoglobin

g A reform in physician payment for in-center HD care from a capitated to a tiered fee-for-service approach, in which nephrologists are paid more for each additional face-to-face visit up to 4 visits per month

h Health related quality of life

i A number to quantify dialysis adequacy

j Hemodialysis

k Parathyroid hormone

l In 2011–12, Queensland Health made incentive payments to renal units for early referred patients who commenced PD, or HD with an AVF/AVG.

m arteriovenous fistula (AVF)/ arteriovenous graft (AVG)

n including new clinical study results, ESA product label revisions, and coverage and reimbursement policy changes

o The U.S., France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom, Australia, Belgium, Canada, New Zealand, and Sweden

p the U.S., Ontario, and five European countries (Belgium, France, Germany, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom

The studies introduced the payment systems (29%), or assessed their effects (71%). The majority of the papers were published after 2011 (66%), were related to PPS (42%), and were implemented in the U.S. (64%) (Table S2, in the appendix). All of the studies were from the high-income and upper middle-income countries according to the world bank 2021 classification. Different sources of data were used by the studies, including medical records, national data, questionnaire, specific renal reporting systems e.g., United States Renal Data System (USRDS), and surveys such as Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). DOPPS is a longitudinal, extensive study in 12 countries, which has collected data on patient and facility levels, and has reported trends of the clinical indicators, outcomes, medication usage, and some other details. 37% of included articles relied on the DOPPS data [15].

Payment methods

FFS, global, capitation, and pay for performance were the main payment systems to reimburse the dialysis centers (Table 2). FFS, salary, and capitation payment systems were the main payment systems to reimburse the nephrologists. In each country a method might be used dominantly; but most of the countries usually use a combination of methods.

Table 2.

dialysis payment systems according to the studies

| Country name | Payment system for medical centers | Payment system for nephrologist |

|---|---|---|

| Italy | FFS (Bundled FFS) | Salary |

| Spain | FFS (Bundled FFS) | Salary |

| Japan | FFS (Bundled FFS) | Salary |

| England | Global, FFS, Pay for performance | Salary, FFS |

| France | Global, FFS, Pay for performance | Salary, FFS |

| Germany | Capitation, FFS, Pay for performance | FFS |

| United States | Capitation, FFS, Pay for performance | Capitation |

| New-Zealand | Global | Salary |

| Canada | Global | FFS |

| Belgium | Capitation | FFS |

| Sweden | Global | Salary |

| Australia | Global | FFS |

| Portugal | Capitation, Pay for performance | – |

| Taiwan | Global | – |

| Queensland | Pay for performance | – |

Adopted from Dor et al. [15]

“Bundled FFS” method, is widely used in Italy, Spain and Japan. In this method the “dialysis bundle” is usually considered as one component, and is paid along with other ancillary services. This method is also called “per treatment payment system” in some countries; since each individual session is reimbursed by FFS [15, 65, 67, 68]. Bundled FFS for dialysis is more toward the PPS than FFS. In England, France, Germany, and the U.S. only ancillary services are paid by FFS system [64, 66, 69, 73].

Capitation method that is also called bundled payment; is a fixed payment system per patient or per episode of care that has been widely used in Portugal, Belgium, Germany, and the U.S. [17, 54, 69, 73]. Portugal seems to be the first European country that implemented dialysis capitation payment system with quality incentives. Capitation payments for dialysis is paid either per patient per treatment, e.g. the U.S. [75], or per patient per week e.g. in Germany, Belgium, and Portugal [17, 54, 69].

The global budget payment method has been used in Canada and New Zealand where an overall budget is allocated to different activities by a regional/local authority [71, 72]. France, England and Australia use a mix method and add some incentives beside the global payment [64, 66, 74].

Pay for performance system has been used more frequently in Queensland, Portugal and the U.S. where some quality indicators are used for payment [31, 54, 73].

In prospective systems “reimbursement” is usually a fixed amount for specific services. For dialysis prospective payments, a package is usually defined. This package in some countries is comprised of only dialysis [65, 67, 68]; whereas in other countries nephrologist’s visit, some dialysis related medications, routine laboratory tests, and imaging, are also included [53, 54, 73].

Studies show that the dialysis services often were paid by FFS at the beginning e.g. Germany [39], Taiwan [23], Portugal [54], France [64], U.S. [73], then they have experienced reforms, aiming at clinical outcome improvement and efficiency increase. For example, the U.S. bundled payment (the 2011 prospective payment system reform) [73], the Portugal 2008 bundled payment system [54]. Papers assessed the effects of various payment systems, reforms and policies. The considered indicators and aspects are provided in Table S3, in the Appendix.

Effects of the payment systems

The majority of studies assessed effects of the payment system on the “service usage” (52%). “Modality related indicators” and “serum related indicators” were also evaluated in many studies (36 and 34% respectively) (Table S3).

Payment systems affect the providers’ behavior. Services which are better paid are used more. In the RPS risk of cost is on the payer side. Whereas in the PPS a fixed fee is usually paid to the provider. The risk of cost is on the provider’s side. Therefore, providers prefer to spend less money. The experienced effects of the dialysis payments according to the studies were classified in some themes in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

effects of the retrospective payment systems for dialysis services based on the studies

| effects | description | Examples from the studies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Under treatment | Avoiding to provide unpaid and inexpensive services |

discourage “intellectual services” e.g. preventive strategies, consultations, counseling (Belgium, FFS b) [17]a, Reduce services with no payment coverage (e.g. paramedical care like psychological care) (Belgium, FFS) [17]a discourage the use of home-based therapies (Belgium, FFS [17]a; USA, 2004 reform) [30] late referral to the nephrology unit (Belgium, FFS) [17]a Replacing more expensive modalities with less expensive ones e.g. home-based therapies (Belgium, FFS) [17]a |

| 2 | over treatment and increasing cost | A shift to provide services which are better paid |

technical services are heavily overpaid (Belgium, FFS) [17]a providing unnecessary services where a referral could be a better choice (Belgium, FFS) [17]a Number of visits and Medicare costs increased in tiered FFS (USA, 2004 reform) [9, 16] |

a Unproven claimed effect

bFee for service

Table 4.

effects of the prospective payment systems and value-based payment systems for dialysis services based on the studies

| Effects | Description | Examples from the studies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | cost saving (efficiency improvement) | reducing unnecessary services |

Use of ESAs reduced in patients who may not benefit from them (USA, 2011 PPS b) [10], Reduce EPO dosage to the lower margin in guidelines (France, global budget) [64]a |

| reducing services in the bundle |

substituting expensive drugs with their less expensive alternatives (for example ESAs were substituted by iron products, less expensive vitamin D products were substituted by more expensive types) (USA, 2011 PPS) [12], Encourage to use less expensive options to control anemia e.g. reduction in EPO dose and increase in patients receiving IV c iron) (Japan, bundled FFS) [27, 68], The cost of antihypertensive drugs during the “dialysis visit” reduced (Taiwan, global budget) [23], EPO use reduced (USA, 2011 PPS [11, 12, 28, 41, 46], (Italy, bundled FFS d) [65]a, (Japan, bundled FFS) [27, 68] IV iron use reduced (USA, 2011 PPS) [11] IV vitamin D use reduced (USA, 2011 PPS) [26] dialysis time shortened (Italy, bundled FFS) [65]a, The nursing staff employment reduced (Belgium, capitation)a [17] |

||

| 2 | Shift in service cost | increasing services outside the bundle |

“Non-dialysis visits” with the prescription of antihypertensive drugs increased (Taiwan, global budget) [23], transfusion rate increased (USA, 2011 PPS) [11, 25, 28], IV iron use increased (Japan, bundling) [27, 68], iron products often therapeutic substitutes for ESA, increased (USA, 2011 PPS) [12] |

| 3 | quality of care | quality reduction through the cost reduction incentive |

Hgb e level reduced (USA, 2011 PPS) [11, 28, 40, 41], PTH level increased (USA, 2011 PPS) [28, 50], physicians may reduce EPO use and their attempt to reach Hgb targets (Italy, bundled FFS) [65]a, Cause a short dialysis time (Italy, bundled FFS) [65]a, It constrains the quality of ESRD care (Spain, bundled FFS) [67]a, Low incentive for quality attentions may affect quality of care: no incentive to improve quality by more sophisticated and more expensive techniques, like the use of biocompatible or high flux membranes, or the use of hemodiafiltration, or for the duration of the session (Belgium, capitation) [17]a, Use low-cost dialysis membrane (France, global budget) [64]a |

| quality improvement through the quality indicators |

fistula use increased (USA, 2011 PPS) [49], short treatment times (less than 4 h) reduced, Kt/V improved, Hgb levels improved (Germany, quality assurance system) [39] fistula use increased (Queensland, quality assurance system) [31] |

||

| 4 | risk of provider | adverse selection | cherry picking occurred “sometimes” or “frequently” (USA, 2011 PPS) [34] |

| Decreasing the profit | longer dialysis without additional reimbursement, may lead to higher costs (Belgium, capitation) [17]a, | ||

| 5 | modality choice | change in use of peritoneal dialysis (PD) or home hemodialysis (HD) |

PD use increased (USA, 2011 PPS) [12, 28, 33, 35–37, 48], home dialysis use increased (USA, 2011 PPS) [44] (PD use increased, Queensland incentive payments) [31], HD increased (Germany, capitation) [69]a, the rate of PD is low, since it is less profitable (Italy, bundled fee) [65]a |

a Unproven claimed effect

b Prospective payment systems

c Intravenous

d Fee for service

d Hemoglobin

Discussion

This review provided an overview of dialysis payment systems and their effects in different countries. Fifty-nine papers were included. The main payment systems for dialysis and related services were FFS, capitation, P4P and global budget. The majority of studies were from high-income countries specially from the USA. The effects of the payment systems, were classified in seven themes including two themes about the RPS, and five themes about the PPS and pay for performance systems.

Payment methods

We found that countries usually use a combination of payment systems. In addition, different payment systems might be used in different levels of the countries. A global budget might be allocated to each geographical area e.g. Australia, France; this budget then might be allocated to each dialysis center by capitation or per treatment method e.g. Belgium, USA; and then in each center the payment to the nephrologists might be salary or FFS method e.g. England, France [15].

Each country might use a combination of payment methods depending on the country situations; as each method might have its strengths and weaknesses; so a method might be appropriate for a country, but not necessarily for another country. Pontoriero et al. found that in Italy the effects of the dialysis FFS (bundled FFS) payment is similar to the PPS. Since the dialysis bundle includes not only the direct care (dialysis), but also the ancillary services (drugs i.e., EPO, and tests required during dialysis session) [65]. Dor et al. compared the global budget in France with the UK. The amount of the global budget in French hospitals did not change according to the changes in the volume and case mix of the population, or technologies. It leads the hospitals to limit the average cost when disease severity or volume increases. While in the UK some additional payment is paid, if the volume is increased [15, 64, 66].

Some of the health systems have revised and improved their dialysis payment systems throughout the time. They usually changed from the FFS to more sophisticated payment methods such as the pay for performance models. For example, the U.S. has adopted different policies and experienced different reforms in changing from the FFS toward the expanded bundled payment in more than a decade [60]. Other example is Portugal, which replaced dialysis FFS with bundled payment [54]. Later, both systems added incentive payment models and improved it throughout the time. Such trends are available for Germany, France, and etc. [15, 64, 69]. Their intention is to encourage the providers to provide services in a more efficient manner, with no harm to the quality of care.

Effects of the payment systems and policies

Dialysis payment reforms show a trend from RPS toward PPS and incentive payments. Studies that have assessed the effects of these dialysis reforms and policies have shown that “dialysis RPS” may be associated with overtreatment of profitable services, and undertreatment of unprofitable services. In the case of Belgium, the high payment for dialysis and no (or low) payment for intellectual activities (prevention, counseling) reduced the nephrologist incentive to prevent the CKD progress. Moreover, patient referral to the nephrology units and the home-based therapies are limited, since they are not profitable for physicians [17]. In the U.S. visit rate increased after the tiered FFS reform in 2004 (incremental payments for each additional nephrologist/patient visits up to four or more visits monthly), which didn’t lead to quality improvement [9, 16].

In the PPS, providers try to keep their profit by cost saving. But sometimes it leads to effectiveness reduction. This study shows that in prospective dialysis payment systems, cost saving might happen through reducing unnecessary services, or reducing services in the bundle. The first one always brings positive results, while the other’s effect is controversial. Swaminathan et al. showed that bundled payment in the U.S. was successful in reducing the ESA usage in patients that may not benefit from them [10].

Reducing services in the dialysis bundle might cause trouble for patients. For instance in Belgium, reduction in dialysis duration and nursing staff employment occurred, following the introduction of bundled services [17, 65]. Andrawis et al. called this issue as “race to the bottom” [76].

Reducing services in the bundle might be through substituting high-cost services by less costly ones. Hirth et al. reported that after the 2011 PPS dialysis bundle in the U.S., ESAs were substituted by iron products, and less expensive vitamin D products were substituted by more expensive types [12]. Moreover, Kuwabara and Fushimi showed new PPS in Japan for breast cancer, led to decrease in medication costs, due to increased use of generic medication in surgical cases [77].

Reducing services in dialysis bundle, sometimes is associated with increasing services out of the bundle. For example, after the U.S. 2011 PPS bundle, in some facilities EPO and iron products reduced, and substituted by blood transfusion [11]. Establishment of dialysis global budget payment in Taiwan reduced the cost of antihypertensive drugs during the “dialysis visit”, which increased “non-dialysis visits” with the prescription of antihypertensive drugs [23]. Such experiences also happened in other prospective payment contexts like DRG-based hospital payments. Shifts from inpatient to outpatient or day-case settings were reported, because of its’ cost minimization incentive [78]. In these cases, a shift in the cost or site of care is occurred. Overall, from the policy-makers perspective, these are advantageous, if they lead to total cost reduction without quality harm. If not, they could lead to undertreatment or patient harm.

Our study shows that; although the dialysis PPS potentially saves cost, it might harm quality. In this regard, the Belgian capitation payment provides low incentive to use high quality, more expensive techniques e.g., biocompatible or high flux membranes, or hemodiafiltration [17]. In Italy the bundled FFS brought a short dialysis time [65] Health systems resolved this challenge by defining quality assessment programs, and incentive payments. Studies show the successful experiences of the dialysis incentive payment systems in Germany [39] and Queensland; Australia [31].

We found that payment systems and related policies e.g., tariff (pricing) policies are used by policy-makers to promote an especial dialysis modality. For example, in Germany, the compensation for PD was defined higher than HD to increase the PD rate [79]. In the U.S. after approval of the separate payment policy for home dialysis training, the rate of home dialysis increased [44]. Haarsager et al. showed an increase in the PD use, after the incentive payments for PD in Queensland [31]. Pontoriero et al., showed negative effect of the bundled FFS payment on the PD rate [65]. In this subject, an example is available from other health conditions. Davis et al. assessed the impact of the 2018 and 2020 change in the Comprehensive Joint Replacement (CJR) reimbursement, which included the outpatient procedures in addition to inpatient procedures in the “CJR episode of care”. It led to increase in outpatient procedures, while reduce in inpatient ones [80].

Decreasing the profit is a provider’s concern, which was noted in this study. A study in Belgium indicated that in PPS, longer dialysis without additional reimbursement, may lead to higher costs [17]. In the 2011 reform of the U.S. Cherry picking possibly occurred to avoid losses [34]. In the other programs of the medical bundles, risk of choosing healthier patients by provider is reported. But there is no empirical evidence in some programs e.g. bundled payment for diabetes care in the Netherlands [81]. Moreover, inconsistent evidence are available about risk selection in Hip and Knee Replacement bundled program [82].

The dialysis providers’ attempt is to mitigate their financial risks and increase their profit. The dialysis PPS programs focus more on cost saving and quality improvement. It is argued that the “cherry-picking” by dialysis providers decrease the cost, and also improve the quality. But it deprives some of the patients in need [83]. Risk of the dialysis providers can be resolved with case-mix adjustments. It was later implemented in some dialysis payment systems such as the U.S. and Germany [75, 79, 84]. Moreover, it was implemented in some other bundled programs e.g. acute myocardial infarction and coronary artery bypass graft [85].

Limitations and research recommendations

Although, we selected the studies based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as the search strategy, we also complemented the search recruiting strategies like forward and backward tracing, but still there might be studies which have ESRD payment components which could not be retrieved by above mentioned strategies. To reduce this limitation, we contacted related researchers and asked them to introduce any relevant studies. This process provided some studies which were not relevant so we did not include them in the study.

Cost controls and quality improvements are more essential in low- and middle-income countries. However, we found no study focusing on the introduction, or assessment of the dialysis payment systems there, which is a gap. So, they are suggested to pay more attentions to ESRD payment systems.

Most of the studies were about the USA and some developed countries. After 2007 the case studies of countries on the dialysis payment systems were limited, which seems to require updates.

Conclusion

This study showed that only the high-income and upper middle-income countries considered their dialysis payment systems to promote quality and efficiency. Different revisions in payment systems were applied to reach this goal through modifying the providers’ behavior. These reforms and policies followed a trend from the FFS toward PPS and pay for performance models, which continues to improve. Each of them had some opportunities and threats. Its’ worthy to pay way toward reducing the threats and strengthening the opportunities to improve the health system.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Database Search Strategies. Table S2. Articles description. Table S3. Indicators classifications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- IV

Intravenous

- Hgb

Hemoglobin

- PD

Peritoneal dialysis

- HD

Hemodialysis

- HHD

Home hemodialysis

- PPS

Prospective payment system

- RPS

Retrospective payment system

- EPO

Erythropoietin

- ESA

Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents

- DOPPS

Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study

- ISHCOF

International Study of Health Care Organization and Financing

- USRDS

The United States Renal Data System

- RBC

Red blood cell

- U.S.

United States

- FFS

Fee-for-service

- P4P

Pay-for-performance

- PTH

Parathyroid hormone

- HRQoL

Health Related Quality of Life

- QA

Quality assurance

- ODGB

Outpatient dialysis global budget payment

Authors’ contributions

All authors conceptualized the scoping review. ZE, RD and MA identified, selected, and extracted data. All authors contributed in writing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This was part of a PhD thesis; that was supported by school of public health, Tehran university of medical sciences.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset (list of included articles) supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the tables in this article and in the supplementary files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zahra Emrani, Email: Z.emrani71@gmail.com.

Mohammadreza Amiresmaili, Email: Mohammadreza.amiresmaili@gmail.com.

Rajabali Daroudi, Email: rdaroudi@yahoo.com.

Mohammad Taghi Najafi, Email: Motanjf@gmail.com.

Ali Akbari Sari, Email: akbarisari@tums.ac.ir.

References

- 1.van der Tol A, Lameire N, Morton RL, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R. An international analysis of dialysis services reimbursement. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(1):84–93. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08150718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong G, Howard K, Chapman JR, Chadban S, Cross N, Tong A, Webster AC, Craig JC. Comparative survival and economic benefits of deceased donor kidney transplantation and dialysis in people with varying ages and co-morbidities. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanholder R, Annemans L, Brown E, Gansevoort R, Gout-Zwart JJ, Lameire N, Morton RL, Oberbauer R, Postma MJ, Tonelli M. Reducing the costs of chronic kidney disease while delivering quality health care: a call to action. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(7):393–409. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen N, van de Craen D, Stamenovic A, Lagor C, Monitoring PH. The importance of home and community-based settings in population health management. Phillips Healthcare. 2013:1–11. https://leadingage.org/wp-content/uploads/drupal/The_importance_of_home_and_community_March_2013_1.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022.

- 5.Ghods AJ, Savaj S. Iranian model of paid and regulated living-unrelated kidney donation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1136–1145. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moradpour A, Hadian M, Tavakkoli M. Economic evaluation of end stage renal disease treatments in Iran. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;8(1):199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2019.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Just PM, De Charro FT, Tschosik EA, Noe LL, Bhattacharyya SK, Riella MC. Reimbursement and economic factors influencing dialysis modality choice around the world. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(7):2365–2373. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin M-Y, Cheng L-J, Chiu Y-W, Hsieh H-M, Wu P-H, Lin Y-T, Wang S-L, Jian F-X, Hsu CC, Yang S-A. Effect of national pre-ESRD care program on expenditures and mortality in incident dialysis patients: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Medicare reimbursement reform for provider visits and health outcomes in patients on hemodialysis. Forum Health Econ Policy. 2014;17(1):53–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Swaminathan S, Mor V, Mehrotra R, Trivedi AN. Effect of Medicare dialysis payment reform on use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(3):790–808. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller DS, Bieber BA, Pisoni RL, Li Y, Morgenstern H, Akizawa T, Jacobson SH, Locatelli F, Port FK, Robinson BM. International comparisons to assess effects of payment and regulatory changes in the United States on anemia practice in patients on hemodialysis: the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(7):2205–2215. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015060673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirth RA, Turenne MN, Wheeler JR, Nahra TA, Sleeman KK, Zhang W, Messana JA. The initial impact of Medicare's new prospective payment system for kidney dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(4):662–669. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busink E, Canaud B, Schröder-Bäck P, Paulus AT, Evers SM, Apel C, Bowry SK, Stopper A. Chronic kidney disease: exploring value-based healthcare as a potential viable solution. Blood Purif. 2019;47(1–3):156–165. doi: 10.1159/000496681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prospective Payment Systems - General Information [https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ProspMedicareFeeSvcPmtGen]. Accessed 14 June 2022.

- 15.Dor A, Pauly MV, Eichleay MA, Held PJ. End-stage renal disease and economic incentives: the international study of health care organization and financing (ISHCOF) Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(2):73–111. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mentari EK, DeOreo PB, O’Connor AS, Love TE, Ricanati ES, Sehgal AR. Changes in Medicare reimbursement and patient-nephrologist visits, quality of care, and health-related quality of life. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(4):621–627. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Biesen W, Lameire N, Peeters P, Vanholder R. Belgium’s mixed private/public health care system and its impact on the cost of end-stage renal disease. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(2):133–148. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9013-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shifting the paradigm of Diaverum Portugal’s renal care services Towards integrated dialysis care. [https://global.diaverum.com/globalassets/why-diaverum/value-based-renal-care/lse-final-version-29-june-2020.pdf]. Accessed 14 June 2022.

- 19.Hippen BE, Maddux FW. Integrating kidney transplantation into value-based care for people with renal failure. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(1):43–52. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussey PS, Ridgely MS, Rosenthal MB. The PROMETHEUS bundled payment experiment: slow start shows problems in implementing new payment models. Health Aff. 2011;30(11):2116–2124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MD, Horsley T, Weeks L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang R-E, Tsai Y-H, Myrtle RC. Assessing the impact of budget controls on the prescribing behaviours of physicians treating dialysis-dependent patients. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(9):1142–1151. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trachtenberg AJ, Quinn AE, Ma Z, Klarenbach S, Hemmelgarn B, Tonelli M, Faris P, Weaver R, Au F, Zhang J. Association between change in physician remuneration and use of peritoneal dialysis: a population-based cohort analysis. Can Med Assoc Open Access J. 2020;8(1):E96–E104. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20190132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang C, Kane R, Levenson M, Kelman J, Wernecke M, Lee J-Y, Kozlowski S, Dekmezian C, Zhang Z, Thompson A. Association between changes in CMS reimbursement policy and drug labels for erythrocyte-stimulating agents with outcomes for older patients undergoing hemodialysis covered by fee-for-service Medicare. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1818–1825. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spoendlin J, Schneeweiss S, Tsacogianis T, Paik JM, Fischer MA, Kim SC, Desai RJ. Association of Medicare's bundled payment reform with changes in use of vitamin D among patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis: an interrupted time-series analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(2):178–187. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasegawa T, Bragg-Gresham JL, Pisoni RL, Robinson BM, Fukuhara S, Akiba T, Saito A, Kurokawa K, Akizawa T. Changes in anemia management and hemoglobin levels following revision of a bundling policy to incorporate recombinant human erythropoietin. Kidney Int. 2011;79(3):340–346. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunelli SM, Monda KL, Burkart JM, Gitlin M, Neumann PJ, Park GS, Symonian-Silver M, Yue S, Bradbury BD, Rubin RJ. Early trends from the study to evaluate the prospective payment system impact on small dialysis organizations (STEPPS) Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(6):947–956. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang R-E, Hsieh C-J, Myrtle RC. The effect of outpatient dialysis global budget cap on healthcare utilization by end-stage renal disease patients. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(1):153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Effects of physician payment reform on provision of home dialysis. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(6):e215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haarsager J, Krishnasamy R, Gray NA. Impact of pay for performance on access at first dialysis in Queensland. Nephrology. 2018;23(5):469–475. doi: 10.1111/nep.13037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Hemodialysis hospitalizations and readmissions: the effects of payment reform. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(2):237–246. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Q, Thamer M, Kshirsagar O, Zhang Y. Impact of the end stage renal disease prospective payment system on the use of peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2(3):350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desai AA, Bolus R, Nissenson A, Chertow GM, Bolus S, Solomon MD, Khawar OS, Talley J, Spiegel BM. Is there “cherry picking” in the ESRD program? Perceptions from a Dialysis provider survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(4):772–777. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05661108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang V, Coffman CJ, Sanders LL. Lee S-YD, Hirth RA, Maciejewski ML: Medicare’s new prospective payment system on facility provision of peritoneal dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(12):1833–1841. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05680518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young EW, Kapke A, Ding Z, Baker R, Pearson J, Cogan C, Mukhopadhyay P, Turenne MN. Peritoneal dialysis patient outcomes under the medicare expanded dialysis prospective payment system. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(10):1466–1474. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01610219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sloan CE, Coffman CJ, Sanders LL, Maciejewski ML, Lee S-YD, Hirth RA, Wang V. Trends in peritoneal dialysis use in the United States after Medicare payment reform. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(12):1763–1772. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05910519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norouzi S, Zhao B, Awan A, Winkelmayer WC, Ho V, Erickson KF. Bundled payment reform and dialysis facility closures in ESKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(3):579–590. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019060575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kleophas W, Karaboyas A, Li Y, Bommer J, Reichel H, Walter A, Icks A, Rump LC, Pisoni RL, Robinson BM. Changes in dialysis treatment modalities during institution of flat rate reimbursement and quality assurance programs. Kidney Int. 2013;84(3):578–584. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spiegel DM, Khan I, Krishnan M, Mayne TJ. Changes in hemoglobin level distribution in US dialysis patients from June 2006 to November 2008. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(1):113–120. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monda KL, Joseph PN, Neumann PJ, Bradbury BD, Rubin RJ. Comparative changes in treatment practices and clinical outcomes following implementation of a prospective payment system: the STEPPS study. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0059-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wetmore JB, Tzivelekis S, Collins AJ, Solid CA. Effects of the prospective payment system on anemia management in maintenance dialysis patients: implications for cost and site of care. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0267-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pirkle JL, Jr, Paoli CJ, Russell G, Petersen J, Burkart J. Hemoglobin stability and patient compliance with darbepoetin alfa in peritoneal dialysis patients after the implementation of the prospective payment system. Clin Ther. 2014;36(11):1665–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin E, Cheng XS, Chin K-K, Zubair T, Chertow GM, Bendavid E, Bhattacharya J. Home dialysis in the prospective payment system era. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(10):2993–3004. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017010041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McFarlane PA, Pisoni RL, Eichleay MA, Wald R, Port FK, Mendelssohn D. International trends in erythropoietin use and hemoglobin levels in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2010;78(2):215–223. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thamer M, Zhang Y, Kaufman J, Kshirsagar O, Cotter D, Hernán MA. Major declines in epoetin dosing after prospective payment system based on dialysis facility organizational status. Am J Nephrol. 2014;40(6):554–560. doi: 10.1159/000370334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mendelssohn DC, Langlois N, Blake PG. Peritoneal dialysis in Ontario: a natural experiment in physician reimbursement methodology. Perit Dial Int. 2004;24(6):531–537. doi: 10.1177/089686080402400611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hornberger J, Hirth RA. Financial implications of choice of dialysis type of the revised Medicare payment system: an economic analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(2):280–287. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pisoni RL, Zepel L, Port FK, Robinson BM. Trends in US vascular access use, patient preferences, and related practices: an update from the US DOPPS practice monitor with international comparisons. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(6):905–915. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tentori F, Fuller DS, Port FK, Bieber BA, Robinson BM, Pisoni RL. The DOPPS practice monitor for US dialysis care: potential impact of recent guidelines and regulatory changes on management of mineral and bone disorder among US hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(5):851–854. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park H, Rascati KL, Keith MS. Managing oral phosphate binder medication expenditures within the Medicare bundled end-stage renal disease prospective payment system: economic implications for large US dialysis organizations. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(6):507–514. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.6.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pisoni RL, Fuller DS, Bieber BA, Gillespie BW, Robinson BM. The DOPPS practice monitor for US dialysis care: trends through august 2011. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(1):160–165. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vanholder R, Davenport A, Hannedouche T, Kooman J, Kribben A, Lameire N, Lonnemann G, Magner P, Mendelssohn D, Saggi SJ. Reimbursement of dialysis: a comparison of seven countries. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(8):1291–1298. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011111094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ponce P, Marcelli D, Guerreiro A, Grassmann A, Gonçalves C, Scatizzi L, Bayh I, Stopper A, Da Silva R. Converting to a capitation system for dialysis payment–the Portuguese experience. Blood Purif. 2012;34(3–4):313–324. doi: 10.1159/000343128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maddux FW. Impact of the bundled end-stage renal disease payment system on patient care. Blood Purif. 2012;33(1–3):107–111. doi: 10.1159/000334164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robinson B, Fuller D, Zinsser D, Albert J, Gillespie B, Tentori F, Turenne M, Port F, Pisoni R. The Dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS) practice monitor: rationale and methods for an initiative to monitor the new US bundled dialysis payment system. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(6):822–831. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Golper TA, Guest S, Glickman JD, Turk J, Pulliam JP. Home dialysis in the new USA bundled payment plan: implications and impact. Perit Dial Int. 2011;31(1):12–16. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2010.00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wish JB. Past, present, and future of chronic kidney disease anemia management in the United States. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2009;16(2):101–108. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naito H. The Japanese health-care system and reimbursement for dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2006;26(2):155–161. doi: 10.1177/089686080602600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Swaminathan S, Mor V, Mehrotra R, Trivedi A. Medicare’s payment strategy for end-stage renal disease now embraces bundled payment and pay-for-performance to cut costs. Health Aff. 2012;31(9):2051–2058. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rivara MB, Mehrotra R. The changing landscape of home dialysis in the United States. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23(6):586. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fuller DS, Pisoni RL, Bieber BA, Port FK, Robinson BM. The DOPPS practice monitor for US dialysis care: update on trends in anemia management 2 years into the bundle. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(6):1213–1216. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Piccoli GB, Cabiddu G, Breuer C, Jadeau C, Testa A, Brunori G. Dialysis reimbursement: what impact do different models have on clinical choices? J Clin Med. 2019;8(2):276. doi: 10.3390/jcm8020276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Durand-Zaleski I, Combe C, Lang P. International study of health care organization and financing for end-stage renal disease in France. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(2):171–183. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pontoriero G, Pozzoni P, Vecchio LD, Locatelli F. International study of health care organization and financing for renal replacement therapy in Italy: an evolving reality. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(2):201–215. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nicholson T, Roderick P. International study of health care organization and financing of renal services in England and Wales. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(4):283–299. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luño J. The organization and financing of end-stage renal disease in Spain. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(4):253–267. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9021-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fukuhara S, Yamazaki C, Hayashino Y, Higashi T, Eichleay MA, Akiba T, Akizawa T, Saito A, Port FK, Kurokawa K. The organization and financing of end-stage renal disease treatment in Japan. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(2):217–231. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kleophas W, Reichel H. International study of health care organization and financing: development of renal replacement therapy in Germany. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(2):185–200. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wikström B, Fored M, Eichleay MA, Jacobson SH. The financing and organization of medical care for patients with end-stage renal disease in Sweden. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(4):269–281. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9014-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ashton T, Marshall MR. The organization and financing of dialysis and kidney transplantation services in New Zealand. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(4):233–252. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Manns BJ, Mendelssohn DC, Taub KJ. The economics of end-stage renal disease care in Canada: incentives and impact on delivery of care. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(2):149–169. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9022-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hirth RA. The organization and financing of kidney dialysis and transplant care in the United States of America. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(4):301–318. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harris A. The organization and funding of the treatment of end-stage renal disease in Australia. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7(2):113–132. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hirth R, Wheeler J, Messana J, Turenne M, Tedeschi P, Sleeman K, Pearson J, Pan Q, Chuang C-C, Turner J. End stage renal disease payment system: results of research on case-mix adjustment for an expanded bundle. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Kidney Epidemiology and Cost Center; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Andrawis JP, Koenig KM, Bozic KJ. Bundled payment care initiative: How this all started. Semin Arthroplast. 2016;27(3):188–92.

- 77.Kuwabara H, Fushimi K. The impact of a new payment system with case-mix measurement on hospital practices for breast cancer patients in Japan. Health Policy. 2009;92(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Busse R, Geissler A, Aaviksoo A, Cots F, Häkkinen U, Kobel C, et al. Diagnosis related groups in Europe: moving towards transparency, efficiency, and quality in hospitals? BMJ. 2013;1–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Mettang T. Changes in dialysis reimbursement regulations in Germany. Perit Dial Int. 2004;24(6):526–527. doi: 10.1177/089686080402400609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Davis CM, III, Swenson ER, Lehman TM, Haas DA. Economic impact of outpatient Medicare total knee arthroplasty at a tertiary care academic medical center. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(6):S37–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Bakker DH, Struijs JN, Baan CA, Raams J, de Wildt J-E, Vrijhoef HJ, Schut FT. Early results from adoption of bundled payment for diabetes care in the Netherlands show improvement in care coordination. Health Aff. 2012;31(2):426–433. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Humbyrd CJ, Wu SS, Trujillo AJ, Socal MP, Anderson GF. Patient selection after mandatory bundled payments for hip and knee replacement: limited evidence of lemon-dropping or cherry-picking. JBJS. 2020;102(4):325–331. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.00756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McLawhorn AS, Buller LT. Bundled payments in total joint replacement: keeping our care affordable and high in quality. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10(3):370–377. doi: 10.1007/s12178-017-9423-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hollenbeak CS, Rubin RJ, Tzivelekis S, Stephens JM. Trends in prevalence of patient case-mix adjusters used in the Medicare dialysis payment system. Nephrol News Issues. 2015;29(6):24–27, 31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Markovitz AA, Ellimoottil C, Sukul D, Mullangi S, Chen LM, Nallamothu BK, Ryan AM. Risk adjustment may lessen penalties on hospitals treating complex cardiac patients under Medicare’s bundled payments. Health Aff. 2017;36(12):2165–2174. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Database Search Strategies. Table S2. Articles description. Table S3. Indicators classifications.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset (list of included articles) supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the tables in this article and in the supplementary files.