Abstract

Background

Hereditary Spastic Paraparesis (HSP) are a group of genetically inherited disorders, clinically and genetically heterogenous and characterized by degeneration of corticospinal tracts, manifesting with progressive spasticity and lower limbs weakness. Most HSPs have an autosomal dominant inheritance. “Ear of the Lynx” sign describes the characteristic abnormality in the forceps minor region of the corpus callosum (CC) on MRI brain. These bear a striking resemblance to the ears of a lynx. This finding has previously been described with hereditary spastic paraparesis 11 and 15, both of which are autosomal recessive HSPs.

Cases

We describe this finding in two siblings with novel mutations causing HSP76, an extremely rare autosomal recessive HSP (less than 50 cases described worldwide), which has not been reported previously.

Conclusion

This sign suggests the presence of pathogenic genetic mutations and is likely indicative of autosomal recessive HSPs.

Keywords: HSP, HSP76, ear of the lynx, spastic paraplegia

Introduction

Hereditary Spastic Paraparesis (HSPs) are a group of inherited disorders, heterogeneous both clinically and genetically. 1 They are characterized by the degeneration of corticospinal tracts, manifesting with progressive spasticity and lower limbs weakness. 2 It affects approximately two in 100,000 people. Most (~70%) HSPs have an autosomal dominant inheritance. “Ear of the Lynx” sign describes the characteristic abnormality in the forceps minor region of the corpus callosum (CC) 3 , 4 on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. Genu fibers of the CC pass through this region and it appears hypointense on T1‐ and hyperintense on T2‐weighted MRI images (Figs. 1 and 2). These bear a striking resemblance to the ears of a lynx which have tufts of hair crowning their ear tips. 5 This finding has previously been described with HSP 11 and 15, both of which are autosomal recessive HSPs caused by pathogenic mutations of the spatacsin gene and spastizin gene, respectively. 5 We describe this previously undescribed finding in two siblings with novel mutations causing HSP 76, an extremely rare autosomal recessive HSP (less than 50 cases described worldwide). We also emphasize that the presence of these imaging findings may help classify variants of uncertain significance (VUS) as pathogenic. 5

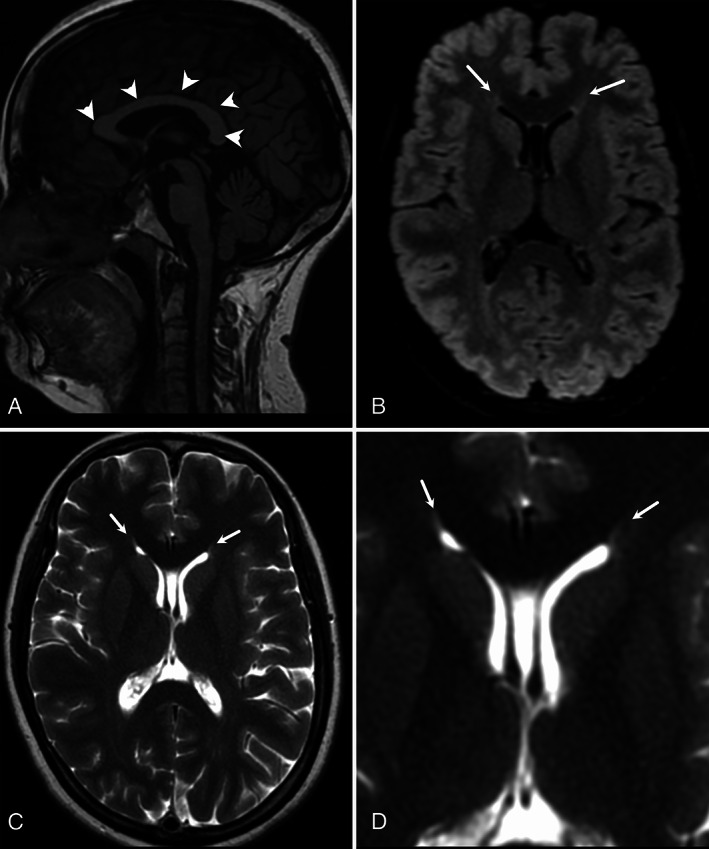

FIG 1.

Case 1—sagittal T1‐WI (A) shows normal corpus callosum (arrowheads) without any atrophy. Axial FLAIR (B) and T2‐WI (C) show flame‐shaped hyperintensity at the tips of the frontal horns of lateral ventricles. These findings are better appreciated in zoomed axial T2‐WI (D).

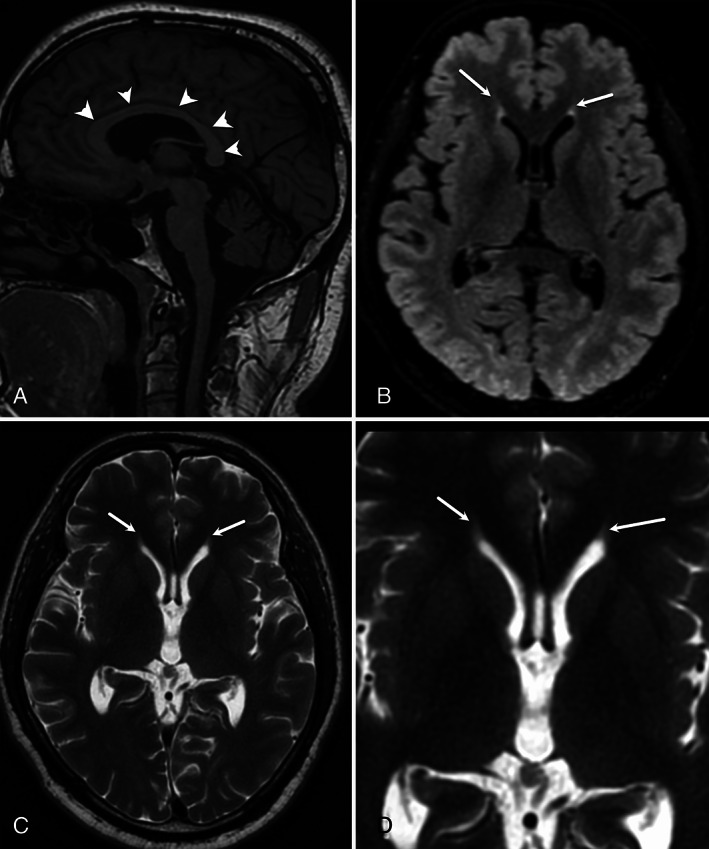

FIG 2.

Case 2—sagittal T1‐WI (A) shows normal corpus callosum (arrowheads) without any atrophy. Axial FLAIR (B) and T2‐WI (C) show flame‐shaped hyperintensity at the tips of the frontal horns of lateral ventricles. These findings are better appreciated in zoomed axial T2‐WI (D).

Case Series

Case 1

A 40‐year‐old gentleman, born out of non‐consanguineous marriage, presented with insidious onset, gradually progressive unsteadiness of gait since 27 years of age. It started with stiffness of legs and criss‐crossing while walking. A few years later, it was complicated by imbalance, swaying to either side, urinary urgency, and incontinence. His speech also became slurred with an explosive quality. He did not have weakness or sensory loss of any limb, tremors, or postural symptoms. He required the help of a walker approximately eight years after symptom onset. He had four siblings, with a younger sister (case 2) having similar symptoms (supplementary Fig. S1). No other relative in the previous two generations had similar complaints.

Examination revealed slowed vertical and horizontal saccades, lower limb predominant spasticity, and hyperreflexia with normal power. He also had cerebellar dysarthria, dysmetria, and dysdiadochokinesia. Gait could not be assessed because of loss of independent ambulation. Cognition and sensory function were unremarkable.

Routine investigations were normal. Serum testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human T‐lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV‐1), vitamin B12, and vasculitic panel were negative. MRI brain showed T2/ FLAIR hyperintensities at the tips of frontal horns of lateral ventricles (Fig. 1), while MRI spine was unremarkable (not shown). A note was made of the presence of cavum septum pellucidum and cavum vergae. In this clinic‐radiological background, a diagnosis of HSP was considered. The patient was initially tested for the common HSP mutations ie, SPG4, SPG7, SPG11, and SPG15, which were found to be negative. Since the diagnostic consideration of HSP was strong, whole exome sequencing was done, which revealed compound heterozygous mutations on the CAPN1 gene (variant‐1: A novel splice site variant, NM_001198868.2; c.1730‐1_1732del at intron16‐exon17 junction involving the canonical splice site and thus is a pathogenic variant as per the ACMG criteria; variant‐2: A novel missense variation: c.1535G > A with a resultant change at protein level, p.Arg512His on exon 12).

Case 2

A 35‐year‐old lady, sibling of case 1, presented with similar complaints from 22 years of age without slurring of speech. Her physical examination revealed slowed saccades, lower limb predominant spasticity, hyperreflexia, and cerebellar signs. Her MRI brain also showed similar findings (Fig. 2). Genetic analysis revealed the same mutations as case 1.

The splice site variation is a novel variant, while the R512H has allele frequency in South Asian population gnomAD of one heterozygous allele (1/248538; 0.00000402). We found one case report describing an alternate mutation arginine➔cysteine at the same position (Arg512Cys). 6 The Insilco prediction of R512H is damaging through multiple tools (Polyphen, Mutation Taster and CADD score of 28.7). Thus, based on the phenotype matching, segregation of variations in sibling and with the available annotation features, both variations were considered to be pathogenic/ likely‐pathogenic as per ACMG guidelines (using varsome tool, https://varsome.com/). These variations were technically validated by Sanger sequencing. Parental samples were not available for confirmation of compound heterozygosity.

Discussion

HSP 76 is an extremely rare form of HSP caused by mutations in the CAPN1 gene. 7 It is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, and 25 families (~27 mutations) with less than 50 cases having been described worldwide. 7 Its presentation varies from a pure to complicated HSP phenotype (with prominent ataxia). Our patients presented with the complicated phenotype with ataxia and slow saccades being additional features over and above the corticospinal tract involvement.

To date, all cases of HSP 76 have described normal MRI brain imaging. 7 , 8 However, we found the “ear of the lynx” sign in both cases. This has previously been reported predominantly in HSP 11 and HSP 15 types. 3 , 4 It has also been described in two patients (in a series of five) with HSP 78, another autosomal recessive HSP. 9 A study revealed that this finding was very sensitive (78%–97%) and specific (90.9%–100%) for HSP and was not found in healthy controls or patients with multiple sclerosis. 5 Rattay et al demonstrated its presence in unaffected family members of an HSP 11 patient who were heterozygous SPG11 mutation carriers, 10 raising the possibility of this sign either detecting prodromal cases or being indicative of a pathogenic mutation, but not necessarily symptomatic disease. 10 A potential mimic of this sign could be a gliotic area at the calloso‐caudal angle of the frontal horn of lateral ventricles. However, those usually have rounded capping 11 instead of a flaming shape, described with the “ear of the lynx.”

Most autosomal recessive HSPs (SPG11 and 15 being most common) present with a complicated phenotype. Most HSP 76 cases, including ours, follow that pattern. However, the peripheral neuropathy present in most SPG11 cases seems absent in HSP 76. 12

This radiological finding of “Ears of the Lynx” may suggest a genetic disorder in a patient presenting with an apparent sporadic paraparesis or intellectual impairment. 5 Therefore, thorough genetic testing should be conducted in patients with this MRI feature. Our patient was initially tested for the four most common mutations causing HSP (SPG4, SPG7, SPG11 and SPG15), which were negative. Following this, detailed genetic analysis was done given the strong clinic‐radiological suspicion of an inherited disorder, which clinched the diagnosis. Also, this radiological finding might help reclassify VUS found on genetic testing as pathogenic/ likely pathogenic, leading to more robust genetic databases.

Finally, our patients were diagnosed with HSP 76, an autosomal recessive HSP. The previously described associations of the “ear of the lynx” sign are autosomal recessive HSPs: HSP 11, HSP15 and HSP 78. This radiological entity might suggest autosomal recessive HSPs rather than specific HSP types.

Conclusion

“The ear of the lynx” sign might suggest the presence of pathogenic/ likely pathogenic genetic mutations of autosomal recessive HSPs. Detailed genetic testing should be undertaken in patients with this finding, even in the absence of a positive family history. Its presence in an individual with a VUS mutation could help reclassify it as pathogenic. 5

Author Roles

(1) Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization and C. Execution. (2) Statistical analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique. (3) Manuscript: A. Writing the first draft, B. Review and Critique.

AA: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B.

AG: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B.

AKS: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B.

RO: 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B.

VG: 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B.

MF: 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B.

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: The authors confirm that the approval of an institutional review board was not required for this work. Written informed consent was obtained from both patients. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflict of Interest: There is no funding information or conflict of interest for any author on the manuscript.

Financial Disclosures for the previous 12 months: There are no relevant financial disclosures in the past 12 months.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Pedigree chart.

References

- 1. Finsterer J, Loscher W, Quasthoff S, Wanschitz J, Auer‐Grumbach M, Stevanin G. Hereditary spastic paraplegias with autosomal dominant, recessive, X‐linked, or maternal trait of inheritance. J Neurol Sci 2012;318(1–2):1–18. 10.1016/j.jns.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blackstone C. Hereditary spastic paraplegia. Handb Clin Neurol 2018;148:633–652. 10.1016/B978-0-444-64076-5.00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kraus MF, Susmaras T, Caughlin BP, Walker CJ, Sweeney JA, Little DM. White matter integrity and cognition in chronic traumatic brain injury: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Brain 2007;130(Pt 10):2508–2519. 10.1093/brain/awm216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mori S, Wakana S, van Zijl PC, et al. MRI Atlas of Human White Matter. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2005. see: https://www.elsevier.com/books/mri-atlas-of-human-white-matter/mori/978-0-444-51741-8. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pascual B, de Bot ST, Daniels MR, et al. “Ears of the lynx” MRI sign is associated with SPG11 and SPG15 hereditary spastic paraplegia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2019;40(1):199–203. 10.3174/ajnr.A5935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lambe J, Monaghan B, Munteanu T, Redmond J. CAPN1 mutations broadening the hereditary spastic paraplegia/spinocerebellar ataxia phenotype. Pract Neurol 2018;18(5):369–372. 10.1136/practneurol-2017-001842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bidgoli MMR, Javanparast L, Rohani M, Najmabadi H, Zamani B, Alavi A. CAPN1 and hereditary spastic paraplegia: A novel variant in an Iranian family and overview of the genotype‐phenotype correlation. Int J Neurosci 2021;131(10):962–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garcia‐Berlanga JE, Moscovich M, Palacios IJ, Banegas‐Lagos A, Rojas‐Martinez A, Martinez‐Ramirez D. CAPN1 variants as cause of hereditary spastic paraplegia type 76. Case Rep Neurol Med 2019;2019:7615605. 10.1155/2019/7615605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Estrada‐Cuzcano A, Martin S, Chamova T, et al. Loss‐of‐function mutations in the ATP13A2/ PARK9 gene cause complicated hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG78). Brain 2017;140:287–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rattay TW, Schöls L, Zeltner L, Rohrschneider WK, Ernemann U, Lindig T. “Ear of the lynx” sign and thin corpus callosum on MRI in heterozygous SPG11 mutation carriers. J Neurol. 2022;269(11):6148‐6151. 10.1007/s00415-022-11198-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sze G, de Armond SJ, Brant‐Zawadzki M, et al. Foci of MRI signal (pseudo lesions) anterior to the frontal horns: Histologic correlations of a normal finding. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986;147:331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stevanin G, Azzedine H, Denora P, et al. Mutations in SPG11 are frequent in autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia with thin corpus callosum, cognitive decline and lower motor neuron degeneration. Brain 2008;131:772–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Pedigree chart.