Abstract

Infant avoidance and aggression are promoted by activation of the Urocortin-3 expressing neurons of the perifornical area of hypothalamus (PeFAUcn3) in male and female mice. PeFAUcn3 neurons have been implicated in stress, and stress is known to reduce maternal behavior. We asked how chronic restraint stress (CRS) affects infant-directed behavior in virgin and lactating females and what role PeFAUcn3 neurons play in this process. Here we show that infant-directed behavior increases activity in the PeFAUcn3 neurons in virgin and lactating females. Chemogenetic inhibition of PeFAUcn3 neurons facilitates pup retrieval in virgin females. CRS reduces pup retrieval in virgin females and increases activity of PeFAUcn3 neurons, while CRS does not affect maternal behavior in lactating females. Inhibition of PeFAUcn3 neurons blocks stress-induced deficits in pup-directed behavior in virgin females. Together, these data illustrate the critical role for PeFAUcn3 neuronal activity in mediating the impact of chronic stress on female infant-directed behavior.

Introduction

Decades of research have focused on the neurobiology of maternal behavior, revealing common mechanisms and pathways involved in infant caregiving across a variety of species1, 2. Studies converged on the critical role of the medial preoptic area (MPOA) in orchestrating the behavioral responses of mothers to their young in frogs, fish, birds, and rodents3-6. Recently, it has been appreciated that these mechanisms may also be involved in paternal behaviors, suggesting existence of a core circuitry across sexes that promotes caregiving7-9. Moreover, it has been well-documented that neural plasticity underlies facilitation of infant caregiving, including alloparental care, particularly in females2.

In the absence of caregiving, it is possible to observe neglect or aggression toward infants by adults. Studies have identified circuit nodes in the brain, including the medial and posterior amygdala, the bed nucleus of stria terminalis, and the perifornical area of hypothalamus (PeFA), that modulate expression of infant-directed neglect and aggression10-13. We wondered if anti-parental circuitry may be active in neglectful animals including virgin or stressed females.

Clinical research shows that stress is a critical risk factor for postpartum mental illnesses including postpartum depression or anxiety which affect up to 25% of women and 10% of men annually in the U.S.14, 15. However, few preclinical studies examine the neurobiology underlying reduced parent-infant bonding in animals16-18. Pre- or postnatal maternal stress has been shown to have a profound impact on the behavioral, physiological, and neurobiological development of offspring19-25. During lactation, females are hyporesponsive to stress due to hormonal changes that impact the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis regulation26, 27. HPA axis hyporesponsivity is thought to protect caregiving and stress-coping in mothers28, 29. However, chronic stress has been documented to have a long-lasting impact on HPA axis regulation, leading to reduced parenting, though the underlying neurobiology remains poorly understood30-32.

Urocortin-3 (Ucn3) is a member of the corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) family of peptides and has the highest endogenous binding affinity for CRF receptor 2 (CRFR2). Overexpression of Ucn3 in the brain leads to increased anxiety- and depression-related behaviors and results in a blunted HPA response to stress33. Social discrimination is altered in a sex-specific manner in total Ucn3 knockout mice34. Furthermore, Ucn3 expression has site-specific behavioral functions such as aiding in recovery of acoustic trauma in the auditory brainstem35, increasing preference for novel conspecifics in the medial amygdala36, and enhancing anxiety-like behaviors in the PeFA37. Previous studies of PeFA Ucn3 (PeFAUcn3) neurons suggest that they are sensitive to stress and modulate vasopressin expression levels in the paraventricular hypothalamus (PVH)38, 39. Taken together, these studies suggest that PeFAUcn3 cells mediate stress-induced behavioral changes.

We recently discovered that PeFAUcn3 neurons govern infant neglect and infanticide in both sexes10. Thus, we hypothesized that chronic stress negatively affects infant-directed behavior in females and this disruption is dependent on activation of PeFAUcn3 neurons. We set out to determine if PeFAUcn3 neurons were more active in stressed females, and if we could recover parenting deficits by blocking activity in PeFAUcn3 cells. We find that enhanced parenting is accompanied by decreased activity in PeFAUcn3 neurons and inhibiting these cells enhances alloparenting in virgin females. Chronic stress reduces alloparenting and this stress-induced behavioral effect is blocked by inhibition of PeFAUcn3 cells. In stressed lactating females, parenting is preserved and PeFAUcn3 neurons are less active. Together, these data reveal a critical role for PeFAUcn3 neurons in the expression of alloparenting in female mice under normal and pathological conditions.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mice were maintained on a 12h:12h dark light cycle (10:30am-10:30 pm dark phase) with ad libitum food and water access. All experiments were performed following NIH and ARRIVE ethical guidelines and approved by Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 20180110; 20180111; 00001386). C57BL/6J virgin and pregnant female (E14) mice were ordered from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) aged 8-10 weeks. Female Ucn3::Cre BAC transgenic line (STOCK Tg(Ucn3-cre) KF43Gsat/Mmcd 032078-UCD; obtained from Catherine Dulac, Harvard University) were also used, aged 2-5 months. Experimental animals were randomly allocated to experimental groups. See Supplement for details.

Corticosterone Measurement

Trunk blood was collected during sacrifice and serum was isolated by centrifugation. A high-sensitivity corticosterone enzyme immunoassay (EIA) was conducted per manufacturer’s instructions (Immunodiagnostic Systems Ltd, Fountain Hills, AZ, USA) as previously described40. See Supplement for details.

Chronic restraint stress (CRS) model

Virgin females were stressed for 20 days and lactating females for 17 days (before pup weaning). Lactating females were restrained starting ~postpartum day 2 (PP2). All females (with their litters) were brought to a test room under dim red light during their dark cycle, weighed, and either placed back into their home cage (and reunited with their litters) or placed into a 50 mL conical tube containing holes for ventilation for 1 hour. Humidity and temperature in the room was recorded each day. On the last day of stress, females remained in the room for 1-2 hours before exposure to a foreign-born pup (see Parental Behavior). For the stressed virgin female group, mice were excluded from the stressed group (n=4) based on open field behavior. For the groups that received viral injections, females with inadequate recombination were excluded (n=2, Figure 2; n=0 Figure 6). See Supplement for details.

Intruder stress model

Lactating females were stressed starting ~PP2. All females were brought to a test room under dim red light during their dark cycle, weighed, and control females were placed back into their home cage while stressed females had an adult male intruder introduced into their home cage for 10 minutes as described previously in rat dams32, 41. See Supplement for details.

Chronic variable stress (CVS) model

Lactating females were stressed starting ~PP2. All mice were brought to a test room under dim red light during their dark cycle, weighed, and either placed back into their home cage or underwent stress. CVS was adapted from a previous study, for details see Supplement40. On the last day of stress, females remained in the test room for 1-2 hours before exposure to a foreign-born pup (see Parental Behavior).

Behavior assays

Mice were individually housed for at least 1 week before testing. Experiments were conducted during the dark phase under dim red light. Tests were recorded by Fly Capture cameras (Point Grey, Richmond, BC, Canada) and behaviors were scored by an observer blind to experimental conditions using Observer XT13 Software or Ethovision XT 13 (Noldus Information Technology, Leesburg, VA, USA). Animals underwent 1 behavioral test per session with at least 24 hours between sessions.

Parental behavior

Parental behavior tests were conducted in the mouse’s home cage as previously described9. Mice were habituated to the testing environment for 10 minutes. One to two C57BL6/J pups 1-4 days old were presented in the opposite corner to the nest and behavior was recorded for 10-15 minutes (see Supplement for details).

Open field

Mice were assessed for activity in a 45cm x 45 cm open field at 40 lux for 5 min as previously described40. Center was considered 15 cm x 15 cm and borders were 5 cm around the perimeter of the box. Time and frequency in center and border, distance, and velocity were calculated using Ethovision XT13.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

FISH was performed as recommended by ACD Bio (Newark, CA, USA) using V1 RNAscope reagents with Fos (Cat No. 316921), Ucn3 (Cat No. 464861), and Crh (Cat No. 316091) probes (see Supplement for details).

Single-cell RNAseq (scRNAseq)

Detailed methods including analysis were previously published42. Raw reads and output of the CellRanger pipeline are available on GEO (GSE113576). See Supplement for details.

Multiplexed Error-robust FISH (MERFISH)

A panel for MERFISH comprising 155 genes was chosen to discriminate major cell classes and mapscRNAseq clusters in tissue sections. Probes were generated as described previously43. MERFISH staining and analysis was performed as described previously42. See Supplement for details.

Immunostaining

To visualize c-Fos protein and DREADD, perfused tissue was sliced on a freezing microtome at 30 μm, and every third PeFA section was stained. Primary antibody chicken anti-mCherry (Millipore AB3566481) and rabbit anti c-Fos (Cell Signaling 2250S) diluted at 1:1000 and secondary anti-chicken-A594 (Sigma CF594) and anti-rabbit-A647 (Life Technologies A31573) diluted at 1:200 and 1:1000 respectively were used. For details, see Supplement.

Chemogenetics

Ucn3::Cre virgin female mice (or Cre− littermates as controls) 8-20 weeks old were used. We stereotaxically injected ~225 nL of conditional inhibitory designer receptor exclusively activated by designer drug (DREADD; AAV1-hSyn-DIO-hM4D(Gi)) virus bilaterally into the PeFA (AP −0.6mm, ML±0.3mm, DV −4.2mm).

Cre+ and Cre− females were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) either 1x PBS (vehicle) or 0.3mg/kg clozapine-n-oxide (CNO) and habituated to the testing environment for 2-3 hours. Females were presented 1-2 C57BL6/J pups in their home-cage and parental behaviors were recorded for 10-15 minutes.

Data analysis and Statistics

For colocalization, we used Fisher’s exact test and a two-tailed Welch’s t test. Pup retrieval percentages are analyzed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov (2 groups) or Friedman test (3 groups). For experiments with one manipulation (i.e. stress or neuronal inactivation), we used two-tailed t-test for normally distributed data and Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed data. One-way and two-way repeated measures ANOVA tests were used followed by post-hoc correction. Data were analyzed by Graphpad Prism 9.0 or Matlab scripts by an investigator blinded to condition. Sample sizes were based on previous experiments 8-10, 40. For complete details, see Supplement. P-values reported as follows: * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001, **** P<0.0001. All data are expressed as mean±SEM.

Image analysis

Images were exported from ZenBlue software and cells were manually counted by an observer blinded to condition using FIJI Cell Counter. Graphpad Prism 9 was used for statistics.

Fiber Photometry

Ucn3-Cre animals were injected with 150 nL of AAV1-syn-jGCaMP7f-WPRE and 225 nL of AAV1-hSyn-DIO-hM4D(Gi)-mCherry and implanted with a 200μm fiber optic cannula into PeFA (ML: 0.3mm; AP −0.6mm; DV 4.2mm). Animals recovered at least 3 weeks before behavioral experiments. Animals were brought up to the test room in dim red light and injected with either vehicle (session 1) or 0.3mg/kg CNO (session 2) i.p. Two hours later, mice were tethered to the fiber optic cable (Doric) and habituated 10 minutes before recording. Using a multi-channel photometry system (Neurophotometrics LTD), a 470nm LED and 415nm LED (isosbestic control) alternately illuminated at 60μW by a 20X objective and fluorescence emission was collected using a CMOS camera at 40 Hz. After 1-2 minutes of recording, animals underwent 6 tail suspensions (~5 seconds). Data were acquired by Bonsai. For analysis details, see Supplement.

Code availability

Custom Matlab code for analysis of photometry data is available at github.com/babdelme/Autrylab_photometry. MERFISH image analysis scripts are available at github.com/ZhuangLab/MERFISH-analysis.

Results

PeFAUcn3 neuronal activation after pup interaction depends on physiological context

To identify activation levels of rostral PeFAUcn3 neurons, we exposed virgin females and lactating females (postpartum day 2) to either a foreign pup (P0-P4) or ~25 mg of fresh bedding (control) in their homecage. Animals were sacrificed 30 minutes later (Figure 1A). To control for the number of pups and foreign pup discrimination44, 45, we utilized two groups of lactating females that either had their litter removed 10 minutes before pup introduction or kept their litter (Figure 1A). We observed an increased proportion of PeFAUcn3 neurons colocalized with Fos in virgin females exposed to a pup compared to controls (Figure 1B, C; Supplemental Figure 1A, D; see Supplemental Figure 1E for FISH validation). However, in lactating females, the proportion of PeFAUcn3 neurons colocalized with Fos with pup exposure decreases with litter removal (Figure 1B, D; Supplemental Figure 1B, D) but increases if the litter is present (Figure 1B, E; Supplemental Figure 1C, D). These results suggest that PeFAUcn3 cells respond to pups similarly in virgin females and lactating females with their litter, while we observe an opposite impact on PeFAUcn3 cell activity in lactating females with litter removal.

Figure 1. PeFA Urocortin-3 neuronal activation levels in response to foreign pups depends on physiological context.

(A) Schematic of behavioral paradigm. C57 virgin females were exposed to a newborn pup and sacrificed 30 minutes after pup exposure or addition of fresh bedding into home cage (control). Lactating females either had a litter removed or litter remained intact and exposed to a foreign-born pup or fresh bedding. (B) Rostral perifornical area cells containing Urocortin-3 and Fos RNA were counted for colocalization in each group (scale bar 100 μm; arrows for colocalization). (C) Quantification of percentage of Ucn3+ cells colocalized with Fos across groups. (Left) Welch’s t test on percentage of PeFAUcn3 cells co-expressing Fos over total Ucn3 reveals significant enhancement in pup exposed virgin females (Welch’s t test; Control n=5 mice; pup exposed n=8 mice; p=0.0024, df=8.041; represented in dots) and (right) fisher exact test on proportion of Ucn3+/Fos+ cells within group compared to Ucn3+/Fos− reveals significant increase (Control n=541 cells; pup exposed n=655 cells; p<0.0001; represented in bars) (D) Lactating females with litters removed had a significant reduction in the proportion of Ucn3+/Fos+ when exposed to a foreign pup (Fisher exact test: Control n=731 cells; pup exposed n=427 cells; p=0.0001; represented in bars) (E) Lactating females with litters undisturbed both has a significant increase in the percentage of Ucn3+/Fos+ neurons (Welch’s t test: Control n=6 mice; Pup exposed n=7 mice; p=0.0341, df=6.657 represented in dots) and a significant upregulation in the proportion of Ucn3+/Fos+ when exposed to a foreign pup (Fisher exact test: Control n=537 cells; pup exposed n=638 cells; p<0.0001; represented in bars). (F-I) Single cell transcriptomic analysis of rostral Ucn3 expressing cells. (F) Cartoon depicting the rostro-caudal extent of the dissection used to conduct single cell transcriptional profiling of the rostral hypothalamus. (G) Experimental scheme for single cell RNA sequencing and MERFISH based spatial transcriptomic profiling of the rostral hypothalamus. (H) t-SNE plot of single cell RNA sequencing clustering of excitatory neurons indicating Z-scored expression of Ucn3. Single cluster expressing Ucn3 expression is marked with a dotted gray circle. (I) MERFISH image of the cluster expressing Ucn3 showing localization to the PeFa (upper panel) and violin plot showing expression profile of important genes within the cluster (lower panel). *All figures generated from previously published data in Moffitt, Bambah-Mukku et al, 2018.

To determine if this activity difference is explained by multiple subsets of PeFAUcn3 neurons, we analyzed previously collected single-cell sequencing and spatial sequencing (MERFISH) data42. Cells were collected for both workstreams from the MPOA and rostral PeFA (Fig. 1F, G). After clustering the single cell dataset, Ucn3 gene expression is highest in one subset of neurons. This single subset of Ucn3 cells is localized in the rostral PeFA, the same region we examined for behavior (Fig. 1I). This unique population of cells is characterized by expression of thyrotropin-releasing hormone (Trh), vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vglut2; or Slc17a6), and several other markers, consistent with previous literature defining this rostral, excitatory population of PeFAUcn3 neurons10, 46, 47.

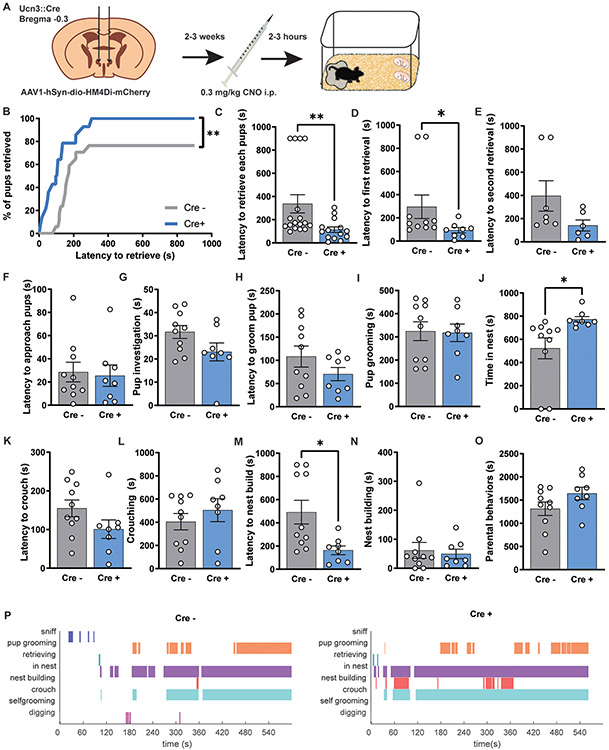

Chemogenetic inhibition of PeFAUcn3 neurons enhances alloparenting

Because virgin females are not as parental as lactating females48-51 and PeFAUcn3 neurons are activated by infanticide in females10, we wanted to test if suppression of PeFAUcn3 neuronal activity enhances alloparenting in virgin females. To accomplish this, we used a conditional viral strategy to express inhibitory DREADD in Ucn3::Cre+ and Cre− animals in the PeFA of virgin females naïve to pups. Two-three weeks after viral injection, both groups of animals were administered CNO (0.3 mg/kg intraperitoneally) and 2-3 hours later exposed to two pups for fifteen minutes in their homecages (Figure 2A; Supplemental Figure 2-1). We confirmed recombination for inclusion in subsequent analyses (Supplemental Figure 2A). Cre+ females retrieved more pups in a shorter amount of time relative to Cre− controls (Figure 2B-D), with no difference in latency to retrieve the 2nd pup (Figure 2E). Furthermore, Cre+ animals spent more time in the nest with pups and started nest-building earlier compared to controls (Figure 2G, I). While other measures of caregiving were not affected (Figure 2 F, H, J-K; Supplemental Figure 2B-E), suppression of PeFAUcn3 neurons improved certain aspects of alloparenting (Figure 2L-M), particularly pup retrieval and time spent in the nest.

Figure 2. Inhibition of PeFAUcn3 neurons enhances alloparental behavior in virgin female mice.

(A) Schematic of viral injection strategy and behavior timeline (n=10 Cre− females; n=8 Cre+ females). (B) Percentage of pups retrieved by Cre+ females is significantly increased compared to Cre− females (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test p=0.0048). (C) Latency to retrieve each of two pups presented during the trial is significantly faster in Cre+ females compared to Cre− females (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test; p=0.0033), as well as (D) latency to retrieve the first pup (Two-tailed Mann-Whiney test; p=0.0259), but there was no difference between groups in (E) latency to retrieve the second pup. (F) Time spent investigating pups trended lower in Cre+ animals (Unpaired t test; p=0.0854, df=16). (G) Time spent in nest with pups significantly increased in Cre+ animals (Unpaired t test; p=0.0289, df=16). (H) Time spent crouching did not yield any significant changes. (I-J) Latency to nest build was significantly faster in Cre+ animals (Two-tailed Mann-Whiney test; p=0.0152) but time spent nest building was not significantly different between groups. (K) Cumulative time spent parenting was unchanged between groups. (L-M) Representative behavior trace of a Cre− animal and a Cre+ animal during pup assay (time 0 is when pup was added to home cage).

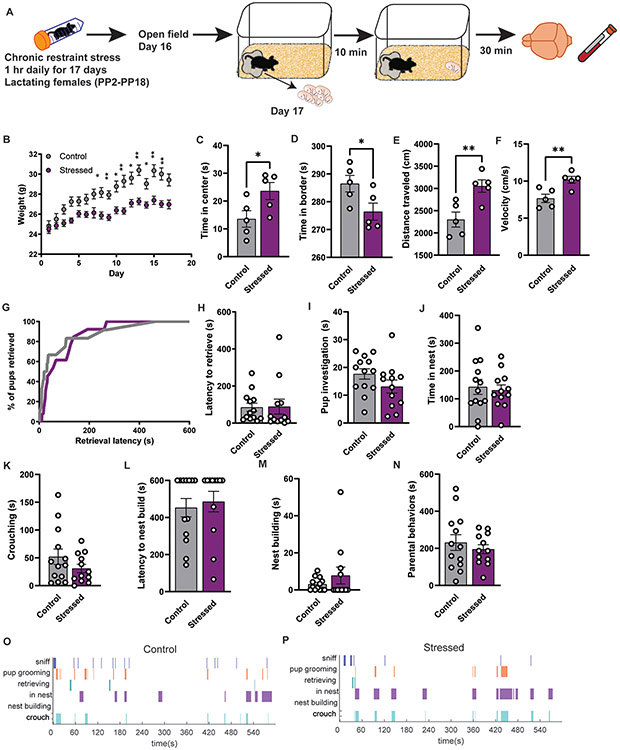

Chronic restraint stress differentially impacts virgin and lactating female parenting

To understand the impact of chronic stress on alloparenting in virgin females, we employed a chronic restraint stress (CRS) paradigm (Figure 3A). Stressed females weighed significantly less than controls (Figure 3B). On day 19, females were tested for exploratory behavior in the open field task (Figure 3C-F). Stressed females spent less time in the center of the field compared to controls (Figure 3C). On the last day of stress, females were exposed to a newborn pup (P0-4) for 15 minutes and their alloparental behavior was recorded and analyzed (Figure 3G-P). Only 2 out of 9, or 22%, of stressed females retrieved pups compared to controls (5 of 9, or 55%) (Figure 3G). Virgin stressed females did not show any significant changes in other quantitative measures of alloparenting (Figure 3H-N; Supplemental Figure 3). However, 2/9 of the stressed females aggressively handled the pups (data not shown) and some stressed virgin females showed less caregiving behaviors (Figure 3O, P). Altogether, we find that CRS significantly reduces pup retrieval in virgin females.

Figure 3. Chronic restraint stress dampens alloparental behavior in virgin female mice.

(A) Schematic of timeline using restraint stress paradigm and behavioral testing in virgin females (n=9 control; n=9 stress). (B) Weights taken from each group during the period of chronic restraint stress. Stressed females have a significant difference in weight compared to controls (Two-way repeated measures ANOVA; main effect of interaction of stress x time F(10,220)=22.92 p<0.0001; main effect of time F(10, 220) = 20.35; Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test) (C) Time spent in center of open field was significantly reduced for stressed females compared to controls (unpaired t test; p=0.0289, df=16) (D-F) but no other parameter in open field was changed. (G) Chronic restraint stress significantly decreased cumulative pup retrieval in females (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; p=0.0059) (H-N) Chronic restraint stress did not significantly change other parenting measures such as retrieval latency, pup investigation, time in nest, crouching, nest building, and total time spent parenting. (O-P) Representative behavior trace for a control female and stressed female during pup assay. (*p=0.05; **p=0.01; ***p=0.001; ****p=0.0001).

Next, to understand the impact of chronic stress on maternal behavior, we utilized CRS in lactating females from PP2-18 (Figure 4A). Like stressed virgin females, stressed lactating females weighed significantly less than controls (Figure 4B), indicating that CRS induced physiological changes. On day 16 of CRS, females were tested in the open field task (Figure 4C-F). Surprisingly, stressed females spent more time in the center and less time in the borders (Figure 4C, D). Stressed females also showed increased velocity and distance traveled relative to controls (Figure 4E, F). On the last day of stress, females had their litters removed and 10 minutes later we tested infant-directed behavior (Figure 4G-P). We observed no difference in number of pups retrieved or retrieval latency between groups (Figure 4G, H). Stressed lactating females showed similar levels of parenting toward pups as controls (Figure 4I-P; Supplemental Figure 4-1). We also implemented a chronic social stress paradigm that was reported to impact parenting in lactating rats32, and we did not observe any changes in weight or parental measures (Supplemental Figure 4-2).

Figure 4. Chronic restraint stress does not induce changes in parental behavior in lactating females.

(A) Schematic of timeline using restraint paradigm and behavioral testing in lactating females (Control n=12; Stressed n=13). (B) Weights taken from each group during the period of chronic restraint stress from postpartum day 2 to 18. Stressed females have a significant difference in weight compared to controls (Two-way repeated measures ANOVA; main effect of interaction of stress x time F(17,368)=8.286 p<0.0001; main effect of time F(7.579,174.3)=75.28 p<0.0001; Sidak’s multiple comparisons) (C) Time spent in center of open field was significantly increased for stressed females compared to controls (unpaired t test; p=0.0459, df=8) and (D) time spent in borders decreased (unpaired t test; p=0.0459, df=8) accompanied by (E) increased distance traveled (unpaired t test; p=0.0089, df=8) and (F) velocity (unpaired t test; p=0.0089, df=8) (G-N) Chronic restraint stress did not significantly change any parenting measures as retrieval, pup investigation, time in nest, crouching, and nest building compared to females that did not receive stress. (O-P) Representative behavior trace for a control female and stressed female during pup assay.

To control for habituation to homotypic stress, we employed a chronic variable stress (CVS) paradigm for 10 days from PP2-12 (Supplemental Figure 4-3). Lactating females subjected to CVS weighed significantly less than controls (Supplemental Figure 4-3B), but we did not observe any differences in the open field test (Supplemental Figure 4C-F). In parenting, most parameters were unchanged between groups (Supplemental Figure 4G-N; Q). However, latency to nest-build was reduced (Supplemental 4-3O) and time spent nest-building was increased (Supplemental 4-3P) in lactating females with CVS.

Chronic restraint stress differentially impacts molecular substrates in virgin and lactating females

Next, we investigated molecular and physiological impacts of CRS in virgin or lactating females. We observed a significant increase in the proportion of PeFAUcn3 neurons colocalized with Fos in stressed virgin females (Figure 5A, B; Supplemental Figure 5-1A, C). In control virgin females, the percentage of PeFAUcn3+/Fos+ colocalization was negatively correlated with time spent parenting, indicating that activity of PeFAUcn3 neurons may reduce alloparenting (Figure 5E). Because activation of CRF cells in the PVH (PVHCRF) is postulated to disrupt maternal behavior and is critical for physiological stress responses52, 53, we also quantified PVHCRF neurons colocalization with Fos (Figure 5A, C; Supplemental Figure 5-1 A, C). We found that the proportion of PVHCRF neurons colocalized with Fos was significantly reduced in stressed virgin females, and, like PeFAUcn3, PVHCRF neuronal activation is negatively correlated with parental behaviors in control virgin females (Figure 5F). CRS did not affect circulating corticosterone levels in virgin females (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Chronic restraint leads to contrasting molecular changes between virgin and lactating females in parenting.

(A) Rostral perifornical area cells containing Ucn3, CRF, and Fos RNA were counted for colocalization in each virgin female group (scale bar 100 μm). (B) Colocalization of Ucn3 and Fos in perifornical area reveals increased (right) proportion of PeFA Ucn3+/Fos+ neurons in stressed virgin females compared to control virgin females (Fisher exact test: Control n=490 cells; Stressed n=472 cells; p=0.038; represented in bars). (C) Colocalization of CRF and Fos in paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus reveals both decreased percentage of PVNCRF+ Fos neurons (Welch’s t test: Control n=9 mice; stressed n=9 mice; p=0.0087, df=8.481 represented in dots) and proportion of Ucn3+/Fos+ in stressed virgin females compared to control virgin females (Fisher exact test: Control n=1305 cells; Stressed n=1272 cells; p<0.0001; represented in bars). (D) Serum corticosterone levels were measured using ELISA in virgin females. Chronic restraint stress did not contribute to altered corticosterone in virgin females. (E) Plotting time spent parenting against PeFAUcn3 activation levels shows marked negative correlation between parenting and PeFAUcn3 neuron activation in controls but this relationship is abolished in stressed virgin females (Control R2=0.51 Stressed R2=0.13; difference in slope F= 10.73 DFn=1, DFd=14; p=0.0055). (F) PVHCRF activation levels in negatively correlated with time spent parenting in control virgin females but this relationship is indiscernible in stressed virgin females (Control R2=0.68 Stressed R2=0.01). (G) Rostral perifornical area cells containing Ucn3, CRF, and Fos RNA were counted for colocalization in each lactating female group (scale bar 100 μm). (H) Proportion of PeFA Ucn3+/Fos+ are reduced in stressed lactating females (Fisher exact test: Control n=338 cells; Stressed n=360 cells; p=0.0005; represented in bars). (I) Colocalization of CRF and Fos in paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus reveals both decreased percentage of PVNCRF+ Fos neurons (Welch’s t test: Control n=6 mice; stressed n=5 mice; p<0.0001, df=7.807) and proportion of Ucn3+/Fos+ in stressed lactating females (Fisher exact test: Control n=919 cells; Stressed n=2268 cells; p<0.0001). (J) Chronic restraint stress significantly reduced corticosterone in lactating females (unpaired t test; p=0.0198, df=22). (K) Linear regression analysis reveals a trend towards negative correlation between time spent parenting and PeFAUcn3 activation levels in control lactating females but not in the stressed group (Control R2=0.27 Stressed R2=0.01). (L) PVHCRF activation is positively correlated with time spent parenting (Control R2=0.45 Stressed R2=0.39).

In lactating females, CRS led to a decrease in the proportion of PeFAUcn3 neurons colocalized with Fos compared to control lactating females, opposite of virgin females (Figure 5G, H; Supplemental Figure 5-1 B, C). Like virgin females, however, PVHCRF cell activation was significantly decreased in chronically restraint stressed lactating females (Figure 5G, I; Supplemental Figure 5-1 B, C), consistent with previous literature54-56. We observed a similar negative trend for correlation of PeFAUcn3 neuronal activation and parental behaviors in control lactating females that we observed in virgin females, but the trend for PVHCRF cell activation is positively correlated in lactating females (Figure 5 K, L). We observed that corticosterone levels were significantly decreased in stressed lactating females (Figure 5J), suggesting adaptive habituation to repeated stress. In our intruder stress experiment, we did not observe molecular changes in PeFAUcn3 activation or circulating corticosterone levels, consistent with no changes in weight or parenting (Supplemental Figure 5-2). Altogether, CRS induces differential PeFAUcn3 activation patterns in response to pups in virgin and lactating females, while CRS reduces PVHCRF neuronal activation in both groups.

CVS increased the proportion of PeFAUcn3 neurons colocalized with Fos in stressed lactating females (Supplemental Figure 5-3B). We did not observe a difference in corticosterone levels between groups (Supplemental Figure 5-3C). When time spent parenting was plotted against the percentage of activated PeFAUcn3 cells, no significant correlation was observed in either condition (Supplemental Figure 5-3D). Latency to nest build was negatively correlated with PeFAUcn3 activation levels (Supplemental Figure 5-3E) while time spent nest building was positively correlated in stressed females (Supplemental Figure 5-3F). Thus, CVS leads to behavioral changes in indirect parenting measures that correlate with PeFAUcn3 cell activity in lactating females.

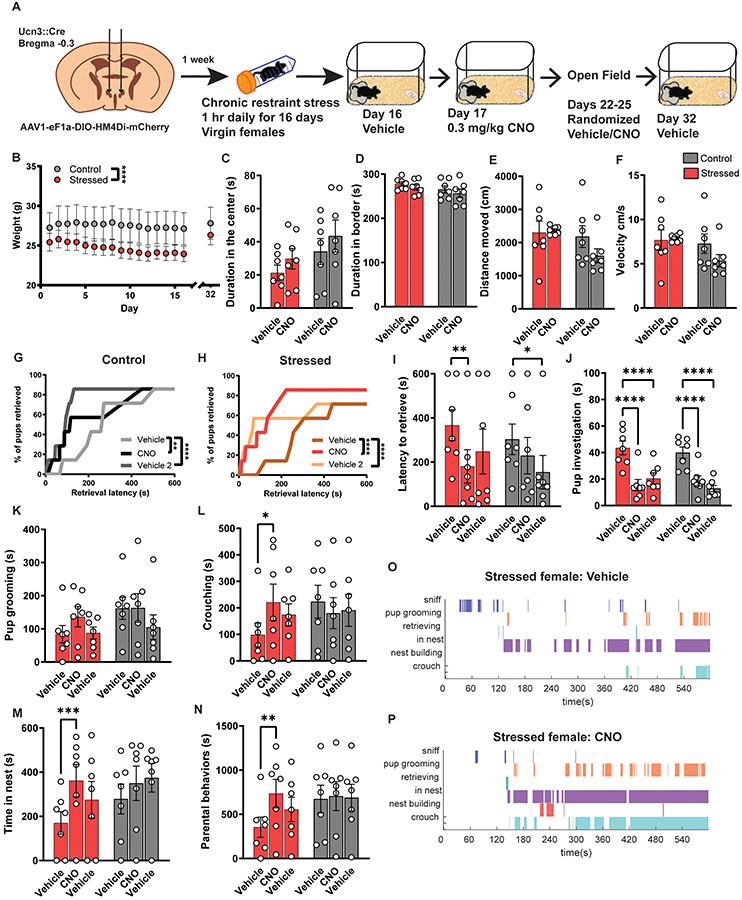

Inhibition of PeFAUcn3 neurons rescues stress-induced deficits in female alloparenting

To confirm that our inhibitory DREADD strategy blocks the activity of PeFAUcn3 neurons, we injected the PeFA of Ucn3::Cre+ females with conditional inhibitory DREADD virus (Supplemental Figure 6-1A). After three weeks, animals were injected intraperitoneally either with vehicle or CNO. CNO administration significantly reduced the proportion of DREADD+/c−Fos+ cells compared to animals injected with vehicle (Supplemental Figure 6B, C). To assess if PeFA neuronal activity is reduced in real time, we injected Ucn3::Cre+ females with conditional inhibitory DREADD with a non-conditional GCaMP, which colocalized in the PeFA (Supplemental Figure 6-1 D, F). Three weeks later, we treated animals with either vehicle or CNO and did 6 tail suspensions for 5 seconds each (Supplemental Figure 6-1 E). We found that CNO administration reduced PeFA GCaMP signal across trials (Supplemental Figure 6-1 G, H) and with a significantly reduced area under the curve and average percent change of fluorescence in tail suspension (Supplemental Figure 6-1 I, J).

Because our CRS paradigm dampened alloparenting in virgin females and increased PeFAUcn3 neuronal activation, we aimed to ameliorate behavior deficits by inhibiting PeFAUcn3 neurons. To accomplish this, we injected virgin Ucn3::Cre+ and Cre− females with inhibitiory DREADD virus and started CRS 1 week after recovery from surgery. After 16 days of CRS, we tested females with vehicle treatment to observe the impact of stress on pup-directed behavior. The following day we administered CNO to determine if blocking PeFAUcn3 neuron activity altered alloparenting. We then observed open field behavior using randomized CNO/Vehicle trials using a crossover design in which each animal received vehicle or CNO on the first day and the alternate drug in the next session. On day 32, we performed another pup exposure with vehicle treatment (Figure 6A). This trial structure was selected based on our previous observation that allowing a pro-parental interaction either through natural pup exposure or via inhibition of PeFAUcn3 neurons leads to lasting enhancements in infant-directed behavior10. Stressed females weighed significantly less than controls (Figure 6B). During open field, CNO administration did not alter exploratory behaviors in either group (Figure 6C-F). In the pup exposure assay, both stressed and control virgin females had improved cumulative retrieval with CNO treatment, which we did not observe in the Cre− group (Figure 6G, H; Supplemental Figure 6-2 A). Strikingly, stressed females given CNO displayed improved latency to retrieve, time spent crouching, time spent in nest and overall time spent parenting which did not occur in unstressed controls or Cre− controls, or in the final vehicle session (Figure 6I, L, M, N; Supplemental Figure 6-2). No significant changes were observed in pup grooming (Figure 6K). Interestingly, pup investigation was significantly decreased in both groups potentially due to familiarity (Figure 7J)57-59. CNO administration did not improve any parenting measures in stressed Cre− females (Supplemental Figure 6-2). Altogether, inhibition of PeFAUcn3 neuronal activity leads to enhanced alloparenting in stressed virgin females (Figure 6O, P).

Figure 6. PeFAUcn3 inhibition ameliorates parenting deficits in stressed virgin females.

(A) Schematic of viral injection strategy and behavior timeline (n=7 stressed Cre+ females; n=7 control Cre+ females). (B) Stressed females had a significant difference in weight compared to control females (2-way repeated measures ANOVA, main effect of stress x time F(16,192)=4.347 p<0.0001). (C-F) Open field results show no difference in time spent in center, border, distance moved, or velocity in control or stressed mice with or without CNO treatment. (G) Cumulative pup retrieval in control animals improves significantly with CNO injection (Friedman’s test; p<0.0001). (H) Cumulative pup retrieval in stressed animals improves with CNO administration (Friedman’s test; p<0.0001). (I) CNO treatment decreases latency to retrieve in stressed females but not in control animals (Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, main effect of drug treatment F(2,24)=8.978 p<0.01; Sidak’s multiple comparisons test post-hoc effect significant for Cre+ stressed group vehicle versus CNO p<0.0037 and for Cre+ control group vehicle versus vehicle p<0.0223). (J) Pup investigation dramatically reduces in both animal groups with CNO (Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, main effect of drug treatment F(2,24)=82.86 p<0.0001; Sidak’s multiple comparisons test post-hoc effect significant for both groups vehicle versus CNO p<0.0001 and vehicle versus vehicle p<0.0001). (K) Pup grooming is unchanged with CNO treatment. (L) Time spent crouching increases with CNO administration in stressed females (Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, main interaction effect of stress and drug F(2,24)=3.506 p<0.0462); Sidak’s multiple comparisons test post-hoc effect significant for Cre+ stressed group vehicle versus CNO p<0.0346). (M) Stressed females spent significantly more time in the nest with CNO administration (Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, main effect of drug treatment F(2,24)=9.399 p=0.001; Sidak’s multiple comparison’s test test post-hoc effect significant for Cre+ stressed group vehicle versus CNO p<0.0008). (N) Cumulative time spent parenting increases with CNO treatment in stressed females (Two-way ANOVA, main effect of drug treatment F(2,24)=3.942 p=0.0331; Sidak’s multiple comparisons post-hoc effect significant for Cre+ stressed group vehicle versus CNO p<0.0038). (O-P) Representative behavior traces showing induction of more parenting behaviors with CNO in stressed females. (Significant post-hoc comparisons noted as follows: *p=0.05; **p=0.01; ***p=0.001; ****p=0.0001).

Discussion

Previously, we observed that virgin females showing alloparental care toward pups have low-level of activation of PeFAUcn3 neurons while strongly activating these cells with chemogenetic or optogenetic methods leads to infant-directed neglect and aggression10. Here, we further explored the role of PeFAUcn3 neurons during female alloparental and maternal behavior. We find that around 20% of PeFAUcn3 neurons are active during alloparenting in virgin females, replicating our previous findings10. However, our data revealed that control bedding exposure and experimental pup exposure conditions impact PeFAUcn3 neural activity differentially in lactating females depending on whether her litter is present. Our results indicate that PeFAUcn3 neurons may be sensitive to specific social or physiological contexts; in the future, it will be important to tease apart whether this heightened baseline PeFAUcn3 neural activity after litter removal may be related to an aversive or stressed state, or possibly a social motivation set point that is altered postpartum. Indeed, previous studies have shown that maternal separation can impact both a mother and offspring’s behavior in measures related to anxiety, social behavior, and cognition60-62.

A related possibility is that virgin female mice find pup encounters aversive and this valence changes peripartum. Indeed, rat females avoid offspring before becoming pregnant63, 64. In laboratory conditions, virgin female mice show approach and interaction with pups8-10, 65, 66 and infant-directed behavior can be improved by guidance from lactating females48. This willingness to approach pups could be due to domestication, given that wild or outbred female mice show much higher rates of infanticide67-70. However, aggression does not necessarily indicate aversion toward a social cue, as aggression toward adult conspecifics can be appetitive71, 72. More research is necessary to specifically address whether adults across sexes and physiological states interpret pup cues as appetitive or aversive and the correspondence with infant-directed behavior.

One potential limitation of our study is that we did not assess estrous phase during behavior testing in virgin females. Studies examining open field behavior indicate that estrous phase does not significantly affect exploration73-75. Literature on the role of estrogen signaling in female infant-directed behavior in mice is controversial. For example, global knockout of estrogen receptor alpha (Esr1) increases infanticide in virgin female mice and knockdown of Esr1 in the MPOA reduces maternal behavior in lactating females76, 77. Conversely, estrogen supplementation of virgin female mice whether ovariectomized or not can uncover infanticide or inhibit pup retrieval78-80. Other studies show that infant-directed behavior is enhanced by experience, rather than hormones, in virgin and lactating female mice. For example, virgin females tested across estrous phases respond to natural pup calls at the same rate with similar levels caregiving behavior, on par with parturient mothers81, 82. Conflicting evidence on the role of circulating ovarian hormones on infant-directed behavior in females is likely due to differences in when estrogen signaling is manipulated, whether constitutively, at birth, or during adulthood, due to the different impacts of estrogen signaling on specific brain regions throughout development83, 84. Now that we have established that stress impacts alloparenting, it becomes critical to study how stress intersects with estrous phase in future research. Postpartum females undergo a brief period of fertility within 24 hours of parturition but afterward experience anestrus throughout lactation, so this limitation does not apply to our lactating female data85, 86.

Our data clearly demonstrate that the method for testing infant-directed behavior in lactating feamles impacts observations. In the literature, there are several approaches for studying infant-directed behavior in rodent mothers that are aligned with the parameter of interest87. For example, to study ultrasonic vocalizations, experimenters often use altered environmental conditions88, 89, litter separation90, 91, or pup handling92, 93 to elicit pup calls. In naturalistic studies, the litter may be removed with some or all pups returned to the homecage, or simply scattered to elicit pup retrieval94-96, or undisturbed homecage behavior may be monitored continuously over long periods of time97, 98. To study maternal motivation, an operationalized design may be used such as introducing a barrier to climb over or a lever to press to gain access to pups8, 99, 100. With increased interest in the neural circuits underpinning parenting, the field should move toward adopting standardized approaches (experimental design, reporting, and analysis) for studying infant-directed behaviors across sex and physiological states.

Furthermore, our data reveal differences in the baseline activation of PeFAUcn3 neurons to pup exposure in early lactating females (Fig. 1) relative to late lactating females (Fig. 5), suggesting that there may be adaptive changes in PeFAUcn3 neuron activity corresponding to lactation phase. Previous research shows altered responsivity of PVH oxytocin-expressing neurons to alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone between non-pregnant and lactating rats101, suggesting that lactation influences neuronal responses in the hypothalamus. Additionally, lactation stage influences behavioral threat responses in rat dams102. Future study examining activity in relevant circuitry over time will be necessary to determine if molecular or behavioral changes occur over phases of lactation.

These changes could also be associated with dynamics of the PeFAUcn3 neuronal population. We showed using scRNAseq data and MERFISH spatial sequencing that these neurons comprise a single subset42. Previous research has established that PeFAUcn3 neurons consist of a rostral and caudal subdivision, with the rostral neurons co-expressing Trh10, 46, 47. Importantly, the scRNAseq and MERFISH datasets were generated using mice of both sexes. However, there could be shifts in the molecular signature of PeFAUcn3 neurons associated with mating status or physiological state such as pregnancy, lactation phase, or stress that these data do not account for. For example, our data reveal that many receptors sensitive to hormonal regulation and physiological state like pregnancy and lactation are expressed by PeFAUcn3 neurons, including Esr1, progesterone receptor (Pgr), and oxytocin receptor (Oxtr). Additionally, there are other definitions of cell type besides molecular expression, including morphology, physiology, or projection patterns103. We have previously shown that PeFAUcn3 neurons across the rostro-caudal axis bifurcate extensively, but further quantification of the projection pattern and examining the spontaneous and evoked firing properties of these neurons may reveal further insight into their function across physiological states.

Our data with CRS suggests that both virgin and lactating females show habituation based on reduced PVHCRF neuronal activity in line with previous research showing reduction in Fos colocalization and intrinsic excitability of PVHCRF neurons after CRS in rodents56, 104. However, this habituation to stress manifests differently in terms of impact on infant-directed behavior across physiological states in females, with virgin females showing reduced alloparenting, but lactating females showing preservation of parenting (Supplemental Figure 6-3). This result was surprising because we anticipated a similar behavioral impact on stressed virgins and mothers. However, previous studies show that lactating females display changes in HPA axis responsivity to stress53, 105, 106, which may account for the behavioral differences. In assessing several stressors in lactating females, we consistently observed a preservation of maternal behavior with different impacts on PeFAUcn3 neuronal activation. With CRS and intruder stress, we observed a decrease or trend toward decreased PeFAUcn3 neuronal activity which we interpret as a mechanism for preserving parenting. However, in CVS, we observed a positive correlation of PeFAUcn3 cell activation with nest-building behavior (Supplemental Figure 6-3). Taken altogether, we interpret that PeFAUcn3 neuronal activity may be reflective of stress coping behavior, as the alternative name for the gene, stresscopin107, implies. Indeed, previous studies have identified neural circuitry that is preferentially involved in active versus passive behavioral coping mechanisms108, 109. We plan to further dissect the relationship of the PeFAUcn3 circuitry to stress-coping and parenting in the future.

Conclusion

Overall, we find that PeFAUcn3 neuronal activity is higher in females showing less alloparenting. Chronic stress leads to reduced alloparenting accompanied by higher numbers of active PeFAUcn3 neurons in virgin females. Blocking activity in PeFAUcn3 neurons rescues infant-directed behavioral deficits in virgin females. Together with previous research10, our results suggest that the level of activity in PeFAUcn3 neurons determines the expression of pro- and anti-parental behavior (Supplemental Figure 6-3), and strengthens the idea that these neurons are critical mediators of stress responses in virgin female mice37-39. These results support the critical role for PeFAUcn3 neurons in the neural circuitry controlling female alloparenting and the sensitivity of this behavior to stress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements and funding

A.E.A. was supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award and a Pathway to Independence Award (NIH R00HD085188). B.A. was supported by a diversity supplement to A.E.A.’s NIH award (R00HD085188-S1) and a Tishman Scholarship. D. B.-M. was supported by a Pathway to Independence Award (NIH R00HD092542). We thank Catherine Dulac for intellectual input and project support at Harvard University. We thank Stacey Sullivan for assistance with the transfer of data and mice from Harvard University to Albert Einstein College of Medicine. We thank Krysten Garcia for histology assistance. We thank Giovanni Podda for guidance on the photometry analysis. We thank Kostantin Dobrenis, Vladimir Mudragel, and Mariah Marrero for guidance on Axioscan usage. We thank Kevin Fisher for assistance with image export and analysis. We thank all the members of the Autry lab for input on manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Numan M The parental brain : mechanisms, development, and evolution. Oxford University Press: New York, 2020, pages cmpp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Numan M, Insel TR. The neurobiology of parental behavior. Springer-Verlag: New York, 2003, ix, 418 p.pp. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer EK, Roland AB, Moskowitz NA, Tapia EE, Summers K, Coloma LA et al. The neural basis of tadpole transport in poison frogs. Proc Biol Sci 2019; 286(1907): 20191084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Numan M Medial preoptic area and maternal behavior in the female rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol 1974; 87(4): 746–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slawski BA, Buntin JD. Preoptic area lesions disrupt prolactin-induced parental feeding behavior in ring doves. Horm Behav 1995; 29(2): 248–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maruska KP, Butler JM, Field KE, Forester C, Augustus A. Neural Activation Patterns Associated with Maternal Mouthbrooding and Energetic State in an African Cichlid Fish. Neuroscience 2020; 446: 199–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Connell LA, Matthews BJ, Hofmann HA. Isotocin regulates paternal care in a monogamous cichlid fish. Horm Behav 2012; 61(5): 725–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kohl J, Babayan BM, Rubinstein ND, Autry AE, Marin-Rodriguez B, Kapoor V et al. Functional circuit architecture underlying parental behaviour. Nature 2018; 556(7701): 326–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Z, Autry AE, Bergan JF, Watabe-Uchida M, Dulac CG. Galanin neurons in the medial preoptic area govern parental behaviour. Nature 2014; 509(7500): 325–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Autry AE, Wu Z, Kapoor V, Kohl J, Bambah-Mukku D, Rubinstein ND et al. Urocortin-3 neurons in the mouse perifornical area promote infant-directed neglect and aggression. Elife 2021; 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen PB, Hu RK, Wu YE, Pan L, Huang S, Micevych PE et al. Sexually Dimorphic Control of Parenting Behavior by the Medial Amygdala. Cell 2019; 176(5): 1206–1221 e1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuneoka Y, Tokita K, Yoshihara C, Amano T, Esposito G, Huang AJ et al. Distinct preoptic-BST nuclei dissociate paternal and infanticidal behavior in mice. EMBO J 2015; 34(21): 2652–2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato K, Hamasaki Y, Fukui K, Ito K, Miyamichi K, Minami M et al. Amygdalohippocampal Area Neurons That Project to the Preoptic Area Mediate Infant-Directed Attack in Male Mice. J Neurosci 2020; 40(20): 3981–3994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paulson JF, Bazemore SD. Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2010; 303(19): 1961–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wisner KL, Sit DK, McShea MC, Rizzo DM, Zoretich RA, Hughes CL et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70(5): 490–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zoubovsky SP, Hoseus S, Tumukuntala S, Schulkin JO, Williams MT, Vorhees CV et al. Chronic psychosocial stress during pregnancy affects maternal behavior and neuroendocrine function and modulates hypothalamic CRH and nuclear steroid receptor expression. Transl Psychiatry 2020; 10(1): 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosinger ZJ, Mayer HS, Geyfen JI, Orser MK, Stolzenberg DS. Ethologically relevant repeated acute social stress induces maternal neglect in the lactating female mouse. Dev Psychobiol 2021; 63(7): e22173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nephew BC, Bridges RS. Effects of chronic social stress during lactation on maternal behavior and growth in rats. Stress 2011; 14(6): 677–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang XD, Rammes G, Kraev I, Wolf M, Liebl C, Scharf SH et al. Forebrain CRF(1) modulates early-life stress-programmed cognitive deficits. J Neurosci 2011; 31(38): 13625–13634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh-Taylor A, Korosi A, Molet J, Gunn BG, Baram TZ. Synaptic rewiring of stress-sensitive neurons by early-life experience: a mechanism for resilience? Neurobiol Stress 2015; 1: 109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rincon-Cortes M, Grace AA. Postpartum scarcity-adversity disrupts maternal behavior and induces a hypodopaminergic state in the rat dam and adult female offspring. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kronman H, Torres-Berrio A, Sidoli S, Issler O, Godino A, Ramakrishnan A et al. Long-term behavioral and cell-type-specific molecular effects of early life stress are mediated by H3K79me2 dynamics in medium spiny neurons. Nat Neurosci 2021; 24(5): 667–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feifel AJ, Shair HN, Schmauss C. Lasting effects of early life stress in mice: interaction of maternal environment and infant genes. Genes Brain Behav 2017; 16(8): 768–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delpech JC, Wei L, Hao J, Yu X, Madore C, Butovsky O et al. Early life stress perturbs the maturation of microglia in the developing hippocampus. Brain Behav Immun 2016; 57: 79–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cameron NM, Champagne FA, Parent C, Fish EW, Ozaki-Kuroda K, Meaney MJ. The programming of individual differences in defensive responses and reproductive strategies in the rat through variations in maternal care. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2005; 29(4–5): 843–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunton PJ, Russell JA, Douglas AJ. Adaptive responses of the maternal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during pregnancy and lactation. J Neuroendocrinol 2008; 20(6): 764–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker CD, Tilders FJ, Burlet A. Increased colocalization of corticotropin-releasing factor and arginine vasopressin in paraventricular neurones of the hypothalamus in lactating rats: evidence from immunotargeted lesions and immunohistochemistry. J Neuroendocrinol 2001; 13(1): 74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medina J, De Guzman RM, Workman JL. Lactation is not required for maintaining maternal care and active coping responses in chronically stressed postpartum rats: Interactions between nursing demand and chronic variable stress. Horm Behav 2021; 136: 105035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller SM, Piasecki CC, Lonstein JS. Use of the light-dark box to compare the anxiety-related behavior of virgin and postpartum female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2011; 100(1): 130–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murgatroyd CA, Pena CJ, Podda G, Nestler EJ, Nephew BC. Early life social stress induced changes in depression and anxiety associated neural pathways which are correlated with impaired maternal care. Neuropeptides 2015; 52: 103–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murgatroyd CA, Nephew BC. Effects of early life social stress on maternal behavior and neuroendocrinology. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013; 38(2): 219–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carini LM, Murgatroyd CA, Nephew BC. Using chronic social stress to model postpartum depression in lactating rodents. J Vis Exp 2013; (76): e50324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neufeld-Cohen A, Kelly PA, Paul ED, Carter RN, Skinner E, Olverman HJ et al. Chronic activation of corticotropin-releasing factor type 2 receptors reveals a key role for 5-HT1A receptor responsiveness in mediating behavioral and serotonergic responses to stressful challenge. Biol Psychiatry 2012; 72(6): 437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deussing JM, Breu J, Kuhne C, Kallnik M, Bunck M, Glasl L et al. Urocortin 3 modulates social discrimination abilities via corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor type 2. J Neurosci 2010; 30(27): 9103–9116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischl MJ, Ueberfuhr MA, Drexl M, Pagella S, Sinclair JL, Alexandrova O et al. Urocortin 3 signalling in the auditory brainstem aids recovery of hearing after reversible noise-induced threshold shift. J Physiol 2019; 597(16): 4341–4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shemesh Y, Forkosh O, Mahn M, Anpilov S, Sztainberg Y, Manashirov S et al. Ucn3 and CRF-R2 in the medial amygdala regulate complex social dynamics. Nat Neurosci 2016; 19(11): 1489–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuperman Y, Issler O, Regev L, Musseri I, Navon I, Neufeld-Cohen A et al. Perifornical Urocortin-3 mediates the link between stress-induced anxiety and energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107(18): 8393–8398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jamieson PM, Li C, Kukura C, Vaughan J, Vale W. Urocortin 3 modulates the neuroendocrine stress response and is regulated in rat amygdala and hypothalamus by stress and glucocorticoids. Endocrinology 2006; 147(10): 4578–4588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venihaki M, Sakihara S, Subramanian S, Dikkes P, Weninger SC, Liapakis G et al. Urocortin III, a brain neuropeptide of the corticotropin-releasing hormone family: modulation by stress and attenuation of some anxiety-like behaviours. J Neuroendocrinol 2004; 16(5): 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Autry AE, Adachi M, Cheng P, Monteggia LM. Gender-specific impact of brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling on stress-induced depression-like behavior. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 66(1): 84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murgatroyd CA, Hicks-Nelson A, Fink A, Beamer G, Gurel K, Elnady F et al. Effects of Chronic Social Stress and Maternal Intranasal Oxytocin and Vasopressin on Offspring Interferon-gamma and Behavior. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2016; 7: 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moffitt JR, Bambah-Mukku D, Eichhorn SW, Vaughn E, Shekhar K, Perez JD et al. Molecular, spatial, and functional single-cell profiling of the hypothalamic preoptic region. Science 2018; 362(6416). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen KH, Boettiger AN, Moffitt JR, Wang S, Zhuang X. RNA imaging. Spatially resolved, highly multiplexed RNA profiling in single cells. Science 2015; 348(6233): aaa6090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ostermeyer MC, Elwood RW. Pup recognition in Mus musculus: parental discrimination between their own and alien young. Dev Psychobiol 1983; 16(2): 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mogi K, Takakuda A, Tsukamoto C, Ooyama R, Okabe S, Koshida N et al. Mutual mother-infant recognition in mice: The role of pup ultrasonic vocalizations. Behav Brain Res 2017; 325(Pt B): 138–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wittmann G, Fuzesi T, Liposits Z, Lechan RM, Fekete C. Distribution and axonal projections of neurons coexpressing thyrotropin-releasing hormone and urocortin 3 in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 2009; 517(6): 825–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen P, Lin D, Giesler J, Li C. Identification of urocortin 3 afferent projection to the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus in rat brain. J Comp Neurol 2011; 519(10): 2023–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carcea I, Caraballo NL, Marlin BJ, Ooyama R, Riceberg JS, Mendoza Navarro JM et al. Oxytocin neurons enable social transmission of maternal behaviour. Nature 2021; 596(7873): 553–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marlin BJ, Mitre M, D'Amour JA, Chao MV, Froemke RC. Oxytocin enables maternal behaviour by balancing cortical inhibition. Nature 2015; 520(7548): 499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lonstein JS, De Vries GJ. Sex differences in the parental behavior of rodents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2000; 24(6): 669–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuroda KO, Tachikawa K, Yoshida S, Tsuneoka Y, Numan M. Neuromolecular basis of parental behavior in laboratory mice and rats: with special emphasis on technical issues of using mouse genetics. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2011; 35(5): 1205–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herman JP, Tasker JG. Paraventricular Hypothalamic Mechanisms of Chronic Stress Adaptation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2016; 7: 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klampfl SM, Bosch OJ. Mom doesn't care: When increased brain CRF system activity leads to maternal neglect in rodents. Front Neuroendocrinol 2019; 53: 100735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Radley JJ, Sawchenko PE. Evidence for involvement of a limbic paraventricular hypothalamic inhibitory network in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis adaptations to repeated stress. J Comp Neurol 2015; 523(18): 2769–2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Girotti M, Pace TW, Gaylord RI, Rubin BA, Herman JP, Spencer RL. Habituation to repeated restraint stress is associated with lack of stress-induced c-fos expression in primary sensory processing areas of the rat brain. Neuroscience 2006; 138(4): 1067–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matovic S, Ichiyama A, Igarashi H, Salter EW, Sunstrum JK, Wang XF et al. Neuronal hypertrophy dampens neuronal intrinsic excitability and stress responsiveness during chronic stress. J Physiol 2020; 598(13): 2757–2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Nonneman RJ, Segall SK, Andrade GM et al. Social approach and repetitive behavior in eleven inbred mouse strains. Behav Brain Res 2008; 191(1): 118–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bielsky IF, Hu SB, Ren X, Terwilliger EF, Young LJ. The V1a vasopressin receptor is necessary and sufficient for normal social recognition: a gene replacement study. Neuron 2005; 47(4): 503–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Richter K, Wolf G, Engelmann M. Social recognition memory requires two stages of protein synthesis in mice. Learn Mem 2005; 12(4): 407–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chapillon P, Patin V, Roy V, Vincent A, Caston J. Effects of pre- and postnatal stimulation on developmental, emotional, and cognitive aspects in rodents: a review. Dev Psychobiol 2002; 41(4): 373–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lemaire V, Koehl M, Le Moal M, Abrous DN. Prenatal stress produces learning deficits associated with an inhibition of neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000; 97(20): 11032–11037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weinstock M Alterations induced by gestational stress in brain morphology and behaviour of the offspring. Prog Neurobiol 2001; 65(5): 427–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Numan M, Sheehan TP. Neuroanatomical circuitry for mammalian maternal behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997; 807: 101–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fleming AS, Vaccarino F, Luebke C. Amygdaloid inhibition of maternal behavior in the nulliparous female rat. Physiol Behav 1980; 25(5): 731–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fang YY, Yamaguchi T, Song SC, Tritsch NX, Lin D. A Hypothalamic Midbrain Pathway Essential for Driving Maternal Behaviors. Neuron 2018; 98(1): 192–207 e110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin-Sanchez A, Valera-Marin G, Hernandez-Martinez A, Lanuza E, Martinez-Garcia F, Agustin-Pavon C. Wired for motherhood: induction of maternal care but not maternal aggression in virgin female CD1 mice. Front Behav Neurosci 2015; 9: 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chalfin L, Dayan M, Levy DR, Austad SN, Miller RA, Iraqi FA et al. Mapping ecologically relevant social behaviours by gene knockout in wild mice. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McCarthy MM, Bare JE, vom Saal FS. Infanticide and parental behavior in wild female house mice: effects of ovariectomy, adrenalectomy and administration of oxytocin and prostaglandin F2 alpha. Physiol Behav 1986; 36(1): 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Konig B Fitness Effects of Communal Rearing in-House Mice - the Role of Relatedness Versus Familiarity. Anim Behav 1994; 48(6): 1449–1457. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ferrari M, Lindholm AK, Konig B. A reduced propensity to cooperate under enhanced exploitation risk in a social mammal. Proc Biol Sci 2016; 283(1830). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Falkner AL, Grosenick L, Davidson TJ, Deisseroth K, Lin D. Hypothalamic control of male aggression-seeking behavior. Nat Neurosci 2016; 19(4): 596–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Golden SA, Heshmati M, Flanigan M, Christoffel DJ, Guise K, Pfau ML et al. Basal forebrain projections to the lateral habenula modulate aggression reward. Nature 2016; 534(7609): 688–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gray P, Cooney J. Stress-induced responses and open-field behavior in estrous and nonestrous mice. Physiol Behav 1982; 29(2): 287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meziane H, Ouagazzal AM, Aubert L, Wietrzych M, Krezel W. Estrous cycle effects on behavior of C57BL/6J and BALB/cByJ female mice: implications for phenotyping strategies. Genes Brain Behav 2007; 6(2): 192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lovick TA, Zangrossi H Jr. Effect of Estrous Cycle on Behavior of Females in Rodent Tests of Anxiety. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12: 711065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ogawa S, Eng V, Taylor J, Lubahn DB, Korach KS, Pfaff DW. Roles of estrogen receptor-alpha gene expression in reproduction-related behaviors in female mice. Endocrinology 1998; 139(12): 5070–5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ribeiro AC, Musatov S, Shteyler A, Simanduyev S, Arrieta-Cruz I, Ogawa S et al. siRNA silencing of estrogen receptor-alpha expression specifically in medial preoptic area neurons abolishes maternal care in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109(40): 16324–16329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mann MA, Kinsley C, Broida J, Svare B. Infanticide exhibited by female mice: genetic, developmental and hormonal influences. Physiol Behav 1983; 30(5): 697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gandelman R Maternal behavior in the mouse: effect of estrogen and progesterone. Physiol Behav 1973; 10(1): 153–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Murakami G Distinct Effects of Estrogen on Mouse Maternal Behavior: The Contribution of Estrogen Synthesis in the Brain. PLoS One 2016; 11(3): e0150728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ehret G, Schmid C. Reproductive cycle-dependent plasticity of perception of acoustic meaning in mice. Physiol Behav 2009; 96(3): 428–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ehret G, Bernecker C. Low-Frequency Sound Communication by Mouse Pups (Mus-Musculus) - Wriggling Calls Release Maternal-Behavior. Anim Behav 1986; 34: 821–830. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Catanese MC, Vandenberg LN. Developmental estrogen exposures and disruptions to maternal behavior and brain: Effects of ethinyl estradiol, a common positive control. Horm Behav 2018; 101: 113–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Woolley CS. Acute effects of estrogen on neuronal physiology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2007; 47: 657–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Croy A The guide to investigation of mouse pregnancy. Academic Press: London ; Waltham, Massachusetts ; San Diego, California, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hedrich HJ, ScienceDirect. The laboratory mouse. 2nd edn. Academic Press Elsevier: London Amsterdam, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hahn ME, Lavooy MJ. A review of the methods of studies on infant ultrasound production and maternal retrieval in small rodents. Behav Genet 2005; 35(1): 31–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Allin JT, Banks EM. Functional aspects of ultrasound production by infant albino rats (Rattus norvegicus). Anim Behav 1972; 20(1): 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Verhaeghe A, Noirot E. Ultrasound by mouse pups from deaf and hearing strains. Dev Psychobiol 1978; 11(2): 117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barron S, Segar TM, Yahr JS, Baseheart BJ, Willford JA. The effects of neonatal ethanol and/or cocaine exposure on isolation-induced ultrasonic vocalizations. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2000; 67(1): 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brunelli SA, Vinocur DD, Soo-Hoo D, Hofer MA. Five generations of selective breeding for ultrasonic vocalization (USV) responses in N:NIH strain rats. Dev Psychobiol 1997; 31(4): 255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Branchi I, Santucci D, Vitale A, Alleva E. Ultrasonic vocalizations by infant laboratory mice: a preliminary spectrographic characterization under different conditions. Dev Psychobiol 1998; 33(3): 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hahn ME, Schanz N. The effects of cold, rotation, and genotype on the production of ultrasonic calls in infant mice. Behav Genet 2002; 32(4): 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brown RE, Mathieson WB, Stapleton J, Neumann PE. Maternal behavior in female C57BL/6J and DBA/2J inbred mice. Physiol Behav 1999; 67(4): 599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hennessy MB, Li J, Lowe EL, Levine S. Maternal behavior, pup vocalizations, and pup temperature changes following handling in mice of 2 inbred strains. Dev Psychobiol 1980; 13(6): 573–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kimchi T, Xu J, Dulac C. A functional circuit underlying male sexual behaviour in the female mouse brain. Nature 2007; 448(7157): 1009–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Molet J, Heins K, Zhuo X, Mei YT, Regev L, Baram TZ et al. Fragmentation and high entropy of neonatal experience predict adolescent emotional outcome. Transl Psychiatry 2016; 6: e702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bendesky A, Kwon YM, Lassance JM, Lewarch CL, Yao S, Peterson BK et al. The genetic basis of parental care evolution in monogamous mice. Nature 2017; 544(7651): 434–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Deviterne D, Desor D, Krafft B. Maternal behavior variations and adaptations, and pup development within litters of various sizes in Wistar rat. Dev Psychobiol 1990; 23(4): 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee A, Clancy S, Fleming AS. Mother rats bar-press for pups: effects of lesions of the mpoa and limbic sites on maternal behavior and operant responding for pup-reinforcement. Behav Brain Res 2000; 108(2): 215–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Perkinson MR, Kirchner MK, Zhang M, Augustine RA, Stern JE, Brown CH. alpha-Melanocyte-stimulating hormone inhibition of oxytocin neurons switches to excitation in late pregnancy and lactation. Physiol Rep 2022; 10(6): e15226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rickenbacher E, Perry RE, Sullivan RM, Moita MA. Freezing suppression by oxytocin in central amygdala allows alternate defensive behaviours and mother-pup interactions. Elife 2017; 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zeng H, Sanes JR. Neuronal cell-type classification: challenges, opportunities and the path forward. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017; 18(9): 530–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bonaz B, Rivest S. Effect of a chronic stress on CRF neuronal activity and expression of its type 1 receptor in the rat brain. Am J Physiol 1998; 275(5): R1438–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Johnstone HA, Wigger A, Douglas AJ, Neumann ID, Landgraf R, Seckl JR et al. Attenuation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis stress responses in late pregnancy: changes in feedforward and feedback mechanisms. J Neuroendocrinol 2000; 12(8): 811–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Douglas AJ, Brunton PJ, Bosch OJ, Russell JA, Neumann ID. Neuroendocrine responses to stress in mice: hyporesponsiveness in pregnancy and parturition. Endocrinology 2003; 144(12): 5268–5276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hsu SY, Hsueh AJ. Human stresscopin and stresscopin-related peptide are selective ligands for the type 2 corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Nat Med 2001; 7(5): 605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Johnson SB, Emmons EB, Lingg RT, Anderson RM, Romig-Martin SA, LaLumiere RT et al. Prefrontal-Bed Nucleus Circuit Modulation of a Passive Coping Response Set. J Neurosci 2019; 39(8): 1405–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Radley J, Morilak D, Viau V, Campeau S. Chronic stress and brain plasticity: Mechanisms underlying adaptive and maladaptive changes and implications for stress-related CNS disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015; 58: 79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.