Abstract

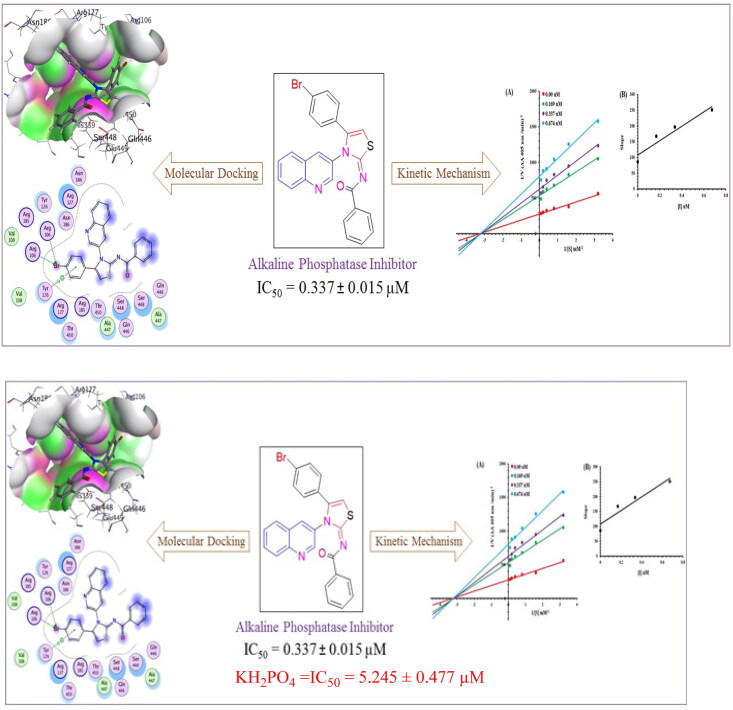

Deposition of hydroxyapatite (HA) or alkaline phosphate crystals on soft tissues causes the pathological calcification diseases comprising of end-stage osteoarthritis (OA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), medial artery calcification and tumour calcification. The pathological calcification is symbolised by increased concentration of tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP). An efficient therapeutic strategy to eradicate these diseases is required, and for this the alkaline phosphatase inhibitors can play a potential role. In this context a series of novel quinolinyl iminothiazolines was synthesised and evaluated for alkaline phosphatase inhibition potential. All the compounds were subjected to DFT studies where N-benzamide quinolinyl iminothiazoline (6g), N-dichlorobenzamide quinolinyl iminothiazoline (6i) and N-nitrobenzamide quinolinyl iminothiazoline (6j) were found as the most reactive compounds. Then during the in-vitro testing, the compound N-benzamide quinolinyl iminothiazoline (6g) exhibited the maximum alkaline phosphatase inhibitory effect (IC50 = 0.337 ± 0.015 µM) as compared to other analogues and standard KH2PO4 (IC50 = 5.245 ± 0.477 µM). The results were supported by the molecular docking studies, molecular dynamics simulations and kinetic analysis which also revealed the inhibitory potential of compound N-benzamide quinolinyl iminothiazoline (6g) against alkaline phosphatase. This compound can be act as lead molecule for the synthesis of more effective inhibitors and can be suggested to test at the molecular level.

Keywords: Alkaline phosphatase, synthesis, DFT, molecular docking, kinetic analysis

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Alkaline phosphatases (APs) are metalloenzymes that contain nucleotide metabolising enzymes1. These APs are abundantly found in nature, including humans and bacteria2. These enzymes play a crucial role in catalysing the hydrolytic dephosphorylation of nucleotides into nucleosides3. Moreover, they are significantly involved in various signalling pathways, including cell signalling via the production of nucleoside from adenine monophosphate (AMP)4, the maturation pathways of adipocytes and osteoblasts5, and purinergic cell signalling pathway6. These are important players in the adipogenesis process7. Tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) is one of four types of APs, and the other three are tissue-specific enzymes, including germ cell alkaline phosphatase (GCAP), placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), and intestinal alkaline phosphatase (IAP)8. The IAP is localised to the duodenum, a part of the gastrointestinal tract, and is an important drug target for inflammatory bowel disease and drug-associated diarrhea9. The overexpression of TNAP is associated with different diseases including various cancers and associated neurodegenerative diseases and complications10. Conclusively, aberrant expression of serum AP levels could result in severe malignancies and bone disorders. Furthermore, the enhanced concentration of alkaline phosphatase in tissues causes calcific diseases11 and these calcific diseases have effects on both skeletal (joints and bones) and non-skeletal tissues2. It also include ankylosing spondylitis (AS) in ligaments or tendons, pathological calcifications causing end-stage osteoarthritis (OA) in joint cartilage, medial artery calcification in the tunica media, or tumour calcification (i.e. in breast cancer)12. These diseases are relatively complex and multi-factorial as most of them are age associated diseases. Since most of these diseases promote inflammatory responses, the administration of anti-inflammatory drugs has been considered effective strategy to relieve pain in patients. The healthcare management has recommended anti-TNF drugs like adalimumab13, etanercept14 and infliximab15,16 for better quality of patients’ life. Although anti-inflammatory drugs are being used to reduce pain but these drugs do not cure and reduce calcification for patients. Now a days, attention has been dedicated to the development of drugs directly targeting the calcification process17,18. Calcification is accelerated by augmented expression of tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) in cells with mineral competency. While the TNAP inhibitors reduce the calcification process and hence diseases associated with calcification can be avoided17.

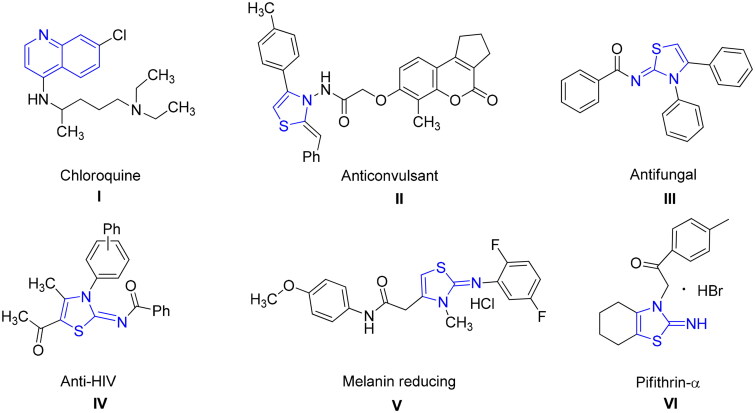

In the quest for safe drug therapy, researchers are striving for development of novel and specific medication for APs associated malignancies. Among various heterocyclic compounds, the quinolone and thiazolines possessed a wide range of biological and pharmacological activities including anti-cancer, anti-fungal, analgesic, antihypertensive and antibiotic activities. Specifically, quinoline has displayed an broad spectrum of biological applications such as anti-fungal, antimalarial, anticonvulsant, analgesic, anti-bacterial, cardiotonic anthelmintic, and anti-inflammatory activities19. Several pharmacologically active substances and natural products (Cinchona Alkaloids) possess quinoline nucleus20. The most famous quinoline based drug chloroquine I (Figure 1) resulted in eradication and control of malaria for the decades. This type of drugs influence parasite’s life cycle during blood stages21.

Figure 1.

Structures of biologically active quinoline and thiazolines.

The second class of compounds i.e. thiazoline moiety also possesses various pharmacological and therapeutic applications in the drug industries. These derivatives exhibit anti-allergic22, antibiotic23, anticonvulsant II24,25, antifungal III26, antihypertensive27, anti-HIV IV28, anti-inflammatory28, antimalarial, antipyretic, antirheumatic, antitumor29, analgesic30 and cytotoxic activities31. 3-Methylthiazolidine is appreciated for the inhibition of indole ethylamine N-methyltransferase (INMT)32 and beneficial for treatment of schizophrenia33. Bayer CropScience developed commercially available iminothiazoline insecticide Thiacloprid34. Moreover, 2-imino-3-(benzoylmethyl)thiazolidine is used to protect from γ-radiation35. Likewise, hydroxy thiazole carboxylate II was stated for the inhibition of HIF-α prolyl hydroxylase while PS-028 is selective GPIIb/IIIa antagonist36,37. Significantly, 2-Imino-1,3-thiazoline scaffolds V impede production of melanin in dose-dependent style, thus acting as whitening agent of skin38. Pifithrin-α VI is recognised iminothiazoline reversible inhibitor of p53-dependant gene transcription and p53-mediated apoptosis39. Thiazolines exhibit interesting applications such as insecticides, acaricides, and plant growth regulators in agriculture40. It also found in the natural products like mirabazoles, tantazoles and thiangazole, which show anti-HIV and anticancer activities41.

The compounds with iminothiazoline moiety also exhibited alkaline phosphatase inhibition activity41. In accordance with the significance of quinoline and iminothiazoline structural components, we have designed and synthesised quinoline based iminothiazoline with multiple point structural diversity to be evaluated reactive molecules with effective alkaline phosphatase inhibition potential which was supported by molecular docking and kinetic studies.

Experimental

General methodology

Utilising silica gel plates with pre-applied aluminium coatings, the compounds’ Rf-values were calculated. Using the open capillary method and the Gallenkamp melting point equipment, the melting points were calculated (MP-D). The IR analysis was carried out using the Bruker FT-IR Bio–Rad-Excalibur Series Mode No. FTS 300 MX spectrometer. When recording the 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra with a Bruker 300 MHz NMR spectrometer in deuterated DMSO and CDCl3 solutions, tetra-methyl silane (TMS) was employed as an internal reference. For HPLC-MS analysis, an Agilent 1200 series LC system was employed, and elemental analyses were conducted using an LECO-183 CHNS analyser.

General method for the synthesis of (E)-N-(4-(4-bromophenyl)-3-(quinolin-3-yl)thiazol-2(3H)-ylidene)alkyl/arylamide 6(a–j)

Potassium thiocyanate (1 mmol) was added in dry acetone (15 ml) in two necks round bottom flask fitted with reflux condenser and stirred for 5 min. The acetone solution of suitably substituted acid chlorides (1 mmol) was added dropwise to dissolve the potassium thiocyanate with stirring. The resulting mixture was heated to reflux the temperature for time of 3–4 h to afford the isothiocyanate. After cooling, an acetone solution of 3-aminoquinoline (1 mmol) was introduced dropwise and temperature of resulting solution was kept 60 °C for 12–14 h to afford the acyl thioureas on addition with ice cooled water. The resultant product was purified by recrystallization in acetone or ethanol.

In the round-bottom flask with 15 ml of dry dichloromethane and triethyl amine, acyl thioureas (1 mmol) was added (1 mmol). With an addition funnel, p-bromophenacyl bromide (1 mmol) solution in dichloromethane was dropped into this mixture over the course of 30 min. To produce the quinolinyl-iminothiazolines 6(a–j), the reaction mixture was heated to 50 °C for 24 h under a nitrogen environment. The solution was filtered, and solvent was extracted using a rotary evaporator when the reaction was completed. The completion of reaction was determined by thin layer chromatography (TLC). The solid products underwent recrystallization in ethanol for purification. The supplementary file contains the comprehensive characterisation information.

Density functional theory calculations (DFT)

The structural geometries of synthesised derivatives were optimised and frequency calculations42 were performed using Gaussian 09W program43. Initially, structures were prepared in required format of sybyl mol2 format using Chem 3D Pro44,45. The files were loaded into the system and calculations were performed using B3LYP functional correlation and STO-3G basis set46. STO-3G basis set belongs to slater and Gaussian type orbitals with enhanced number of functions which ensure rapid convergence and ensure reduced computational cost. These sets are often used to produce accurate assumptions on mono and diatomic systems47. It is single zeta type basis set48 which provide 1s function for first row elements, and two 2s and one p(px, py, pz) function for second and third row elements [2s1p]49–51. STO-3G basis set is widely used for many elements of periodic table with good precision. The analysed structures were evaluated for frontier molecular orbitals52, HOMO/LUMO energy gap, chemical hardness and softness of derivatives53. The optimised files were visualised using Gauss View 6.054.

Alkaline phosphatase inhibition assay and kinetic mechanism analysis

The inhibitory activity of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase was evaluated using spectrophotometric assay as previously reported in our studies55,56. In addition, Kinetic mechanism analysis was conducted to determine the mechanism of inhibition. The most potent molecule was selected on the basis of IC50 in order investigate the competitive or non-competitive enzyme inhibition by following our previously reported method57. The detailed procedure for alkaline phosphate inhibition assay and kinetic mechanism analysis is given in supplementary file.

Molecular docking

The molecular docking procedure was then carried out using the optimised structures derived from DFT investigations. For the purpose of predicting interactions of derivatives inside the protein’s active pocket, the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) 2015.10 was used58.

Initially, 3 dimensional crystallographic structure of alkaline phosphatase was retrieved form protein data bank (www.rcsb.com; PDB ID: 1alk). After retrieving 3D crystallographic structure of target, preparation of protein is important step to proceed for molecular docking. To begin, protein was dealt with the energy minimisation stage. Then, the atomic charges must always be adjusted, followed by the adaptation of the potential energy. Additionally, crucial characteristics were regulated using the MMFF94x force field including incorporation of polar hydrogens and removal of hetero atoms59. Second, the site finder was implemented to the protein structure, followed by the creation of spheres at selected residues of active pocket. Finally, the ligand library was exported in necessary format (MDB) and docked at selected residues. Total 100 poses were selected to represent the complex’s most stable configuration. To rank interaction efficiency, the scoring energy values were computed using the London dG scoring function, which was refined twice using triangular Matcher methods. Additionally, critical interaction data such as ligand receptor interactions and the amino-acid backbone involved, binding energy and kind of interaction were saved when the process was completed60. The docking protocol was validated by redocking co-crystal ligand and RMSD of produced pose was compared to native pose of the ligand. The RMSD value less than 2 angstroms validated the docking protocol. The visualisation of 3D and 2D poses of tope ranked conformation was retrieved form PyMOL61 and LigPlot plus62 respectively.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

Molecular dynamics simulation is inevitable to integrate the motion equation of atoms with respect to the reference frame63. Desmond software was used to simulate the protein–ligand complex for 100 ns in the TIP3P solvent model. The optimised potential for liquid simulations (OPLS3) forcefield64 was used to simulate the complex under PBC (periodic boundary conditions). The orthorhombic solvation box was used to solvate the system with TIP3P water molecules. The counter ions (NaCl) were incorporated at a concentration of 0.15 M for neutralisation purposes. The initial energy minimisation was carried out for 2000 steps using the steepest descent method to omit any steric clashes. At 300 K and 1.01 bar pressure, the system was adjusted in an isothermal and isobaric (NPT) ensemble. A cut-off distance of 10 angstroms was used to take into account short-range van der Waals interactions. A Martyna–Tobias–Klein barostat65 and Nose–Hoover thermostat were also utilised to keep the pressure steady and temperature during simulation66. The final production run was conducted for 100 ns, and trajectories were saved at every 100 ps. The time step of 2 fs was utilised to integrate the motion equations. The particle mesh Ewald method67 was employed for precise and reliable investigation of electrostatic interactions. The Desmond simulation interaction diagram protocol was used to analyse the simulated trajectories of protein–ligand complexes68.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

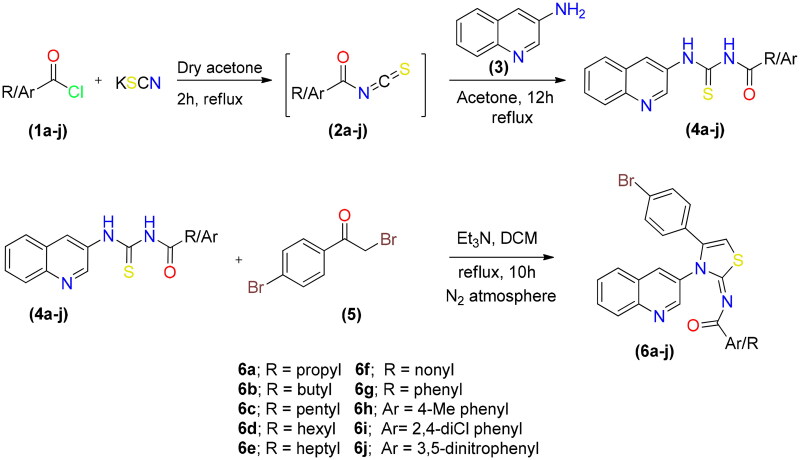

By reacting potassium thiocyanate with various acid chlorides in dry acetone, followed by the addition of 3-aminoquinoline to produce the appropriate acyl thioureas, a range of new quinolinyl iminothiazolines were synthesised. After purification, the acyl thioureas were reacted with p-bromophenacylbromide to obtain the (E)-N-(4-(4-bromophenyl)-3-(quinolin-3-yl)thiazol-2(3H)-ylidene)alkyl/aryl amides 6(a–j) as shown in Scheme 1. The reactions were carried out in dry solvents because intermediate 2 undergo hydrolysis in the presence of moisture. The last step was completed in inert atmosphere to avoid the formation of side products.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route for synthesis of quinolinyl iminothiazoline 6(a–j).

Spectroscopic characterisation

The newly developed scaffolds of quinolinyl iminothiazolines were characterised by NMR, HPLC-MS and FT-IR. FT-IR spectra of synthesised compounds demostrated the absorption band for C–H aromatic at 3059–3115 cm−1, C–H thiazoline at 2957–3062 cm−1 and C = O at 1679–1738 cm−1. The 1H NMR spectra of compound 6(a–j) contained three characteristic signals, aromatic protons of quinolinyl and phenyl ring appeared at δ 8.95–7.28 ppm, singlet of proton located at thiazoline ring observed at δ 6.39–6.53 ppm and alkyl protons give rise to signals at δ 2.37–0.86 ppm. In 13C NMR spectra signal for carbonyl carbon appeared at δ 171.2–173.6 ppm, signal for imine carbon of thiazoline ring observed at δ 168.9–171.3 ppm and carbon at 5-position of thiazoline ring give rise to signal at δ 103.6 − 106.2 ppm. Aromatic carbons of quinolinyl and phenyl moiety signals appeared at δ 149.4–126.4 ppm while aliphatic carbons were appeared at δ 30.5–13.5 ppm. These signals indicated the formation of desired analogue. HPLC plot of compound 6a contained the band with retention time of 8.7 min. DAD spectrum involved two main band and one shoulder band. Among the two main bands, the band appeared at 343 nm was due to the quinolinyl group while the band observed at 237 nm was due to styrenyl moiety. The one shoulder band appeared at 255 nm was due to iminothiazoline ring with less conjugation. The positive mode ESI/MS of compound 6a contained a peak at m/z = 453 assigned as molecular ion peak [M + H]+.

Density functional theory studies

The functional correlation DFT/B3LYP was used to optimise the structures and geometry with the basis set STO-3G. Optimisation was the arranging of atoms in a molecule with the goal of minimising energy consumption. Table 1 summarises the optimised geometry parameters, including optimisation energy, polarizability, and dipole moment.

Table 1.

Geometrical Parameters of selected compounds.

| Sr. no. | Compound code | Optimisation energy (hartree) | Polarizability (α) (a.u.) | Dipole moment (Debye) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01. | 6a | −4014.881 | 206.169 | 1.245 |

| 02. | 6b | −4053.730 | 212.856 | 1.251 |

| 03. | 6c | −4092.578 | 219.034 | 1.269 |

| 04. | 6d | −4131.426 | 225.013 | 1.251 |

| 05. | 6e | −4170.274 | 230.332 | 1.345 |

| 06. | 6f | −4247.970 | 242.821 | 1.249 |

| 07. | 6g | −4126.566 | 245.221 | 1.212 |

| 08. | 6h | −4165.418 | 246.059 | 1.159 |

| 09. | 6i | −5035.731 | 250.268 | 3.576 |

| 10. | 6j | −4529.915 | 265.240 | 4.745 |

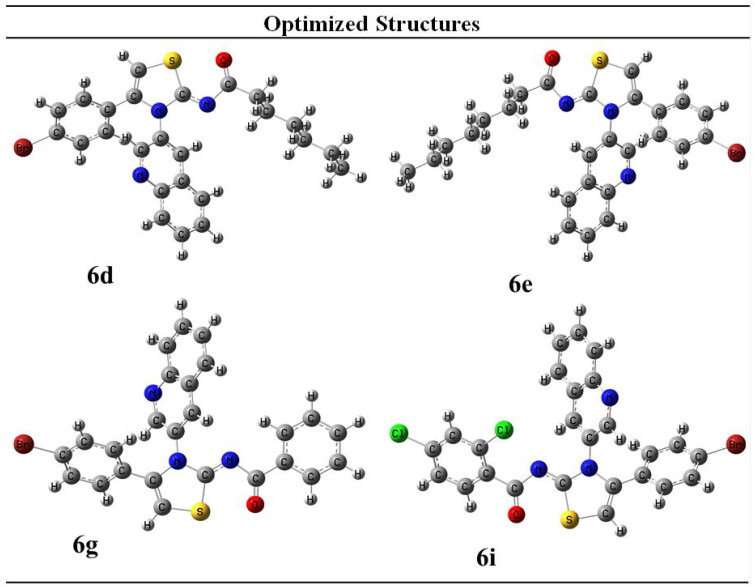

The synthesised derivatives’ obtained optimised geometries represented real local minima without the inclusion of imaginary frequencies. To achieve the sharpest energy gradient, these structural geometries were optimised. Figure 2 illustrates the optimised structures for several derivatives.

Figure 2.

Optimised structures of potent compounds (6d, 6e, 6g and 6i).

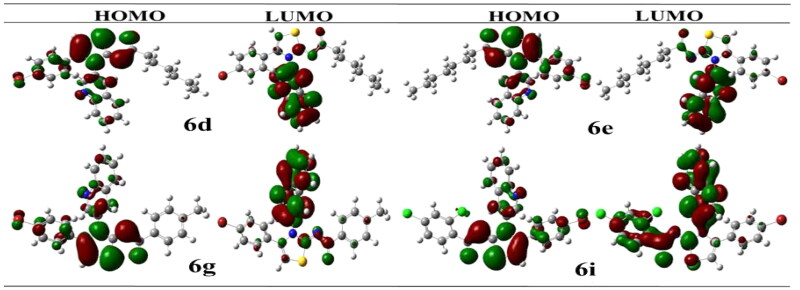

The highest occupied molecular orbital, HOMO, possesses a nucleophilic characteristic. The lowest unoccupied molecular orbital, LUMO, is having electrophilic characteristic. The LUMO HOMO energy gap is critical for anticipating a compound’s reactivity. The majority of electronic changes have occurred in the LUMO HOMO gap. Because it is the outermost orbital, HOMO tends to give an electron. Due to the fact that the innermost orbital contains open space, LUMO tends to take an electron (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

HOMO-LUMO structures of potent compounds (6d, 6e, 6g and 6i).

Compound with the smallest energy gap would be the reactive one among all. While the compound with the best kinetic stability is the compound showing great energy gap among all. The compound with the highest HOMO energy is the compound that would be the best electron donor. Whether the compound showing lowest LUMO value is the compound that would be the best electron acceptor. In current scenario, compound 6g would be the highly reactive with energy gap of 0.142 eV. The most kinetically stable compound is 6i with HOMO/LUMO energy gap of 0.147 eV. Compound 6e would be the best electron donor with the highest HOMO energy of −0.121. Compound 6i would be the best electron accepter with the lowest LUMO energy of 0.016. Energetic parameters are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Energetic parameters that predict reactivity of compounds.

| Compound | EHOMO (eV) | ELUMO (eV) | ΔEgap (eV) | Hardness (η) | Softness (S) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6a | −0.12215 | 0.02109 | 0.1432 | 0.072 | 6.98 |

| 6b | −0.12197 | 0.02102 | 0.1430 | 0.071 | 6.99 |

| 6c | −0.12197 | 0.02109 | 0.1431 | 0.072 | 6.99 |

| 6d | −0.12188 | 0.02107 | 0.1430 | 0.071 | 7.00 |

| 6e | −0.12190 | 0.02118 | 0.1431 | 0.072 | 6.99 |

| 6f | −0.12189 | 0.02108 | 0.1430 | 0.071 | 6.99 |

| 6g | −0.12368 | 0.01890 | 0.1426 | 0.071 | 7.01 |

| 6h | −0.12235 | 0.01975 | 0.1421 | 0.071 | 7.04 |

| 6i | −0.13031 | 0.01668 | 0.1470 | 0.073 | 6.80 |

| 6j | −0.13625 | 0.00330 | 0.1396 | 0.070 | 7.17 |

Alkaline phosphatase (ALPs) inhibition assay

The ten synthesised derivatives were subjected to evaluation for alkaline phosphatase inhibition. KH2PO4 was the reference substance used for screening, and Table 3 summarises the findings of evaluation as IC50. Interestingly, most of the synthesised compounds demonstrated promising inhibitory potential against alkaline ALPs. Moreover, most of the compounds showed better inhibition activity comparative to KH2PO4. Compound 6g was compared to other analogues in the series, and was found as series’ significant alkaline phosphatase inhibitor.

Table 3.

IC50 values of compounds 6(a–j) values of alkaline phosphatase inhibitory activity.

| Compound | Alkaline phosphatase | Compound | Alkaline phosphatase |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 ± SEM (µM) | IC50 ± SEM (µM) | ||

| 6a | 7.247 ± 0.435 | 6f | 8.681 ± 0.908 |

| 6b | 3.154 ± 0.251 | 6g | 0.337 ± 0.015 |

| 6c | 4.239 ± 0.241 | 6h | 6.304 ± 0.634 |

| 6d | 0.886 ± 0.074 | 6i | 0.957 ± 0.071 |

| 6e | 0.754 ± 0.055 | 6j | 0.509 ± 0.036 |

| KH2PO4 | 5.245 ± 0.477 | ||

Values are presented as Mean ± SEM (Standard error of mean).

Structure activity relationship (SAR)

In Scheme 1, total 10 derivatives of the (E)-N-(4-(4-bromophenyl)-3-(quinolin-3-yl)thiazol-2(3H)-ylidene)alkyl/aryl amides 6(a–j) were synthesised bearing various alkyl or aryl group substitution. The nature of functionalities substituted around iminothiazoline moiety influenced the alkaline phosphatase inhibition activity. Quinolinyl iminothiazoline moiety substituted with aromatic substituents (6g–6j) exhibit better inhibition activity comparative to aliphatic analogues (6a–6f). Among the analogues 6g–6j, the compound 6g having unsubstituted benzene ring proved as most potential inhibitor which might be due to less steric crowd. The compound 6g (IC50 = 0.337 ± 0.015 µM) containing benzoyl moiety around iminothiazoline component exhibited greater inhibition potential among all other equivalents. The analogue 6j (IC50 = 0.509 ± 0.036 µM) was retrieved as second best inhibitor due to the presence substituted aryl ring instead of long alkyl chain. However, the substitution on the aryl ring slightly reduced the inhibitory effect due to enhanced steric hindrance. The inhibitory activities of both phenyl bearing compounds against alkaline phosphatase was stronger than standard KH2PO4 (5.245 ± 0.477 µM). While in the aliphatic analogue (6a–6f), long alkyl chains, which are sterically hindered substituents, reduced the potential inhibitory effect. The compound 6f (IC50 = 8.681 ± 0.908 µM) showed relatively low inhibitory efficacy, perhaps as a result of its lengthy alkyl chain. However, compounds 6d and 6e possessing hexyl and heptyl substituents, respectively, exhibited a comparatively better inhibition profile than standard compounds. The inhibitory activities of compound 6d and 6e were 0.886 ± 0.074 and 0.754 ± 0.055 µM respectively. Table 3 is representing inhibition profile of all synthesised derivatives.

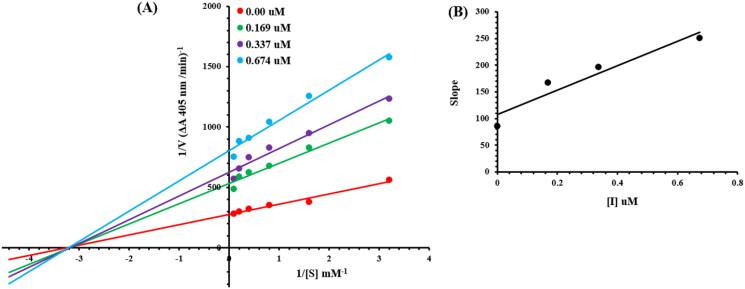

Kinetic mechanism for ALPs

The current most effective compound, 6g, has been investigated for its mechanism of alkaline phosphatase inhibition. According to the EI and ESI constants, respectively, it was determined if the compounds had the ability to inhibit the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex. Figure 4 illustrates a succession of straight lines obtained from the Lineweaver–Burk plot of the enzyme’s kinetic studies against the substrate para nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt at various inhibitor doses (A). Compounds 6g’s outcomes demonstrated that they intersected in the 2nd quadrant. The results exhibited that whereas Km remained constant, Vmax fell in response to new, increasing inhibitor doses. This behaviour suggests that compounds 6g produce an enzyme inhibitor complex by non-competitively inhibiting alkaline phosphatase. The secondary plot of slope vs inhibitor concentration shown in Figure 4 revealed the enzyme–inhibitor dissociation constant (Ki) (B). Table 4 displays the kinetic results (Kinetic parameter table).

Figure 4.

Alkaline phosphatase inhibition by compounds 6g as shown by Lineweaver-Burk plots (a). The plot of the slope vs inhibitor concentrations to get the inhibition constant is shown in the insets (b). Using the linear least squares fit, the lines were drawn.

Table 4.

Kinetic parameters of the alkaline phosphatase for para nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt activity in the presence of different concentrations of 6g.

| Concentration (µM) | Vmax (ΔA /Min) |

Km (mM) |

Inhibition type |

Ki (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.00354 | 0.31 | Non-Competitive | 0.47 |

| 0.169 | 0.00204 | 0.31 | ||

| 0.337 | 0.00175 | 0.31 | ||

| 0.674 | 0.00133 | 0.31 |

Ki = EI dissociation constant; Vmax = the reaction velocity; Km = Michaelis-Menten constant.

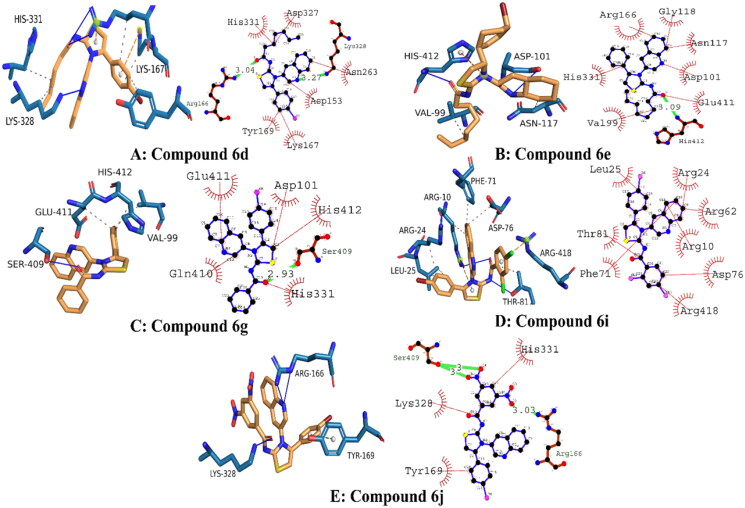

Molecular docking

The Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) program was used to determine the most likely molecular interactions between ligands and targeted protein. The synthesised derivatives demonstrated potential in-vitro activities were selected for evaluation of binding mode inside active pocket of protein. The amino acid residues engaged in the molecular interactions were as follows; His331, Asp327, Asn263, Lys328, Asp153, Lys167, Tyr169, Arg166, Gly118, Asn117, Asp101, Glu411, His412, Val99, Arg24, Arg62, Arg10, Asp76, Arg418, Phe71, Thr81, Leu25, Ser409, Gln410, Ser409, Lys328, Tyr169, and Arg166. The docking score of compound 6d, 6e, 6g, 6i and 6j were tabulated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Binding energies of the potent inhibitors of alkaline phosphatase.

| Compound | Binding energies (kJ/mol) | Hydrogen bonding residues | Bond length (angstroms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6d | −26.75 | Lys328, Arg166 | 3.27, 3.04 |

| 6e | −25.94 | His412 | 3.09 |

| 6g | −28.86 | Ser409 | 2.93 |

| 6i | −25.10 | – | – |

| 6j | −28.45 | Ser409, Ser409, Arg166 | 3.0, 3.0, 3.03 |

The docked conformation analysis for compound 6d exhibited strong molecular interactions. Conclusively, two hydrogen bonds were observed with the targeted protein. The first hydrogen bond was present between the electronegative oxygen atom and Arg166 with a bond length of 3.04 angstroms. A second hydrogen bond was observed between N3 of compound 6 and Asn263, with a bond length of 3.27 angstroms. In addition, hydrophobic interactions were engaging His 331, Asp327, Asn263, Lys167, Tyr169, and Asp153. These interactions were collectively stabilising the protein–ligand complex with a docking score of −26.75 kJ/mol.

The binding orientation of compound 6e exhibited potential molecular interactions with the targeted protein. It was observed that compound 6e was involved in single hydrogen bonding between electronegative oxygen and His412 residue. The bond length of hydrogen bonding was 3.09 angstroms, indicating its good strength. The docking score of conformation was −25.96 kJ/mol, which is slightly lower than compound 6d. It was expected because compound 6D formed strong hydrogen bonds. In addition, the following amino acid residues were involved in hydrophobic interactions with compound 6e: Arg166, Gly118, Asn117, Asp101, Glu411, His412, and Val99.

The analysis of the binding orientation of compound 6g demonstrated significant molecular interactions and exhibited the highest docking score. Interestingly, compound 6G demonstrated potential in vitro activity against alkaline phosphatase, which is further supported by in silico findings. Critical analysis revealed that compound 6G involved important amino residues at the active site with strong molecular interactions. A single hydrogen bond was observed between electronegative oxygen and Ser409 with a strong bond length of 2.93 angstroms. Furthermore, hydrophobic interactions involved His331, Gln410, Glu411, Asp101, and His412 amino acid residues with strong strength. The docking score of the protein-6g conformation was −28.86 kJ/mol.

In terms of molecular interactions, compounds 6i and 6j exhibited strong chemical bonding with targeted proteins. However, the chemical bonding strength of compound 6j was stronger than compound 6i. Briefly, it was observed that compound 6i was engaging Arg24, Arg62, Arg10, Asp76, Arg418; Phe71; Thr81; and Leu25 amino acid residues in important molecular interactions, and the docking score of conformation was observed to be −25.10 kJ/mol. Whereas, compound 6j demonstrated equipotent activity with compound 6g with a docking score of −28.45 kJ/mol. It was observed that a total of three hydrogen bonds were produced by compound 6j. Electronegative oxygen atoms O4 and O5 were engaging Ser409 in hydrogen bonding with bond lengths of 3 and 3 angstroms, respectively. Another hydrogen bond was observed between O2 of compound 6j and Arg166 of the targeted protein. These hydrophilic interactions stabilised the protein–ligand complex. In addition, His331, Lys328, and Tyr169 were engaged in hydrophobic interactions, including alkyl, pi-alkyl, and aromatic interactions, respectively. The presumed 3D and 2D interactions of top-ranked compounds 6d, 6e, 6g, 6i, and 6j are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Illustrating the 3D and 2D binding interactions of potent compounds (6d, 6e, 6g, 6i and 6j).

Molecular Dynamics simulation studies

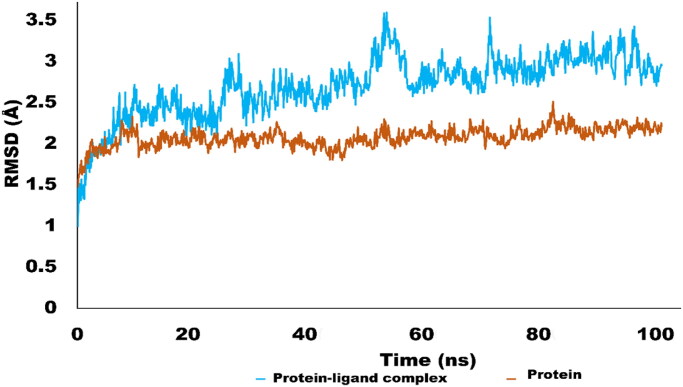

The Molecular dynamics simulations are used to estimate the thermodynamic parameters of living systems under physiological conditions. The best docked conformation was subjected to MD simulations studies using Desmond program. The simulation studies for 100 ns provided significant insight into stability of protein ligand complex. MD simulation trajectories were used to derive various analytic matrices including RMSD, RMSF, contact profile and ligand interaction profile. The RMSD plot for protein(C alpha) and protein–ligand complex is represented in Figure 6. The RMSD pattern for C alpha atoms of protein exhibited significant stability. It was revealed that initially RMSD fluctuate around 2 Å which rose up to 2.4 Å. The amino acid residues Thr17, Gly14, Asn15, Gln13, Gly27 and Thr1 exhibited variations up to 2.4 Å. However, the average RMSD for protein C alpha atom was 2.01 Å which is perfectly in acceptable limit. In terms of complex RMSD, it was slightly higher than c-alpha atoms of protein. Initially complex fluctuated around 2–2.5 Å which jumped to 3.5 Å after 50 ns of simulation. Interestingly, after rising to 3.5 Å, RMSD again dropped to 2.5 Å and get stable and equilibrated throughout the trajectory. The higher fluctuations of complex were due to structural changes of ligand inside active pocket. After 50 ns, ligand established new and stronger interactions which stabilised the trajectory during the simulated time. The average RMSD of the complex was found to be 2.69 Å which is acceptable69. The Figure 6 is illustrating the RMSD pattern for protein and protein–ligand complex.

Figure 6.

RMSD trajectory analysis for protein (brown coloured trajectory), protein ligand complex (blue coloured trajectory).

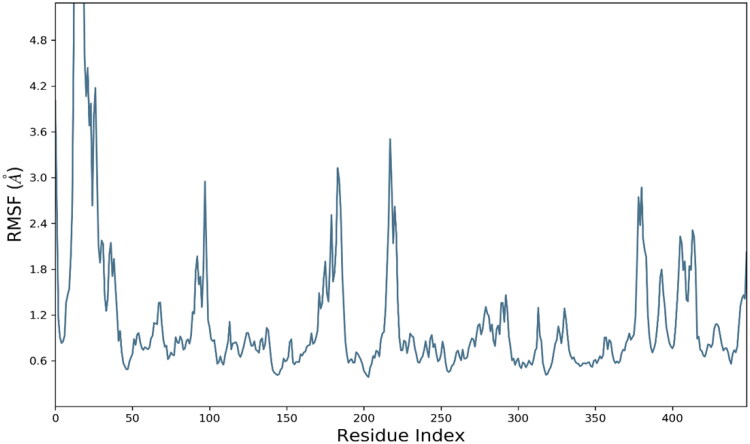

The analysis of root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) is crucial analytical metric in characterising the local structural changes in the protein. In current study, residue wise RMSF was generated for each residue. RMSF exhibited optimal fluctuations for majority of residues but residues Thr1, Asn15, Ile16, THr17, Ala18, Pro19, Gly20, Gly21, Ala22, and Arg23 exhibited substantial structural variations up to 8 Å. These residues were belongs to C and N terminal which are comparatively less compact than backbone and alpha strands residues. The average RMSF value for whole protein was calculated as 1.14 Å which is quite acceptable. The RMSF evolution is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Evolution of RMSF for amino acid residues of targeted protein.

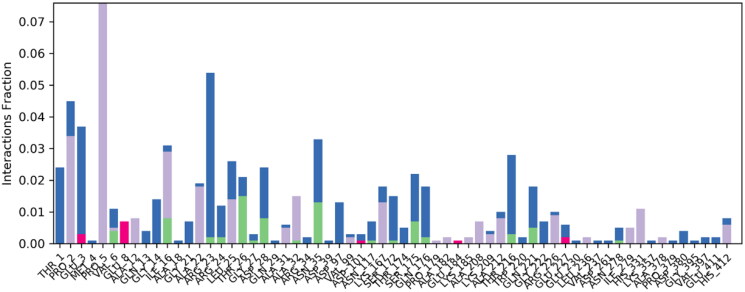

The contact linkages play important role in establishing the significant contacts between ligand and protein. Type and interaction time determine the stability of complex. In present complex, hydrogen bonding, water bridges and hydrophobic interactions were observed between protein and ligand. Important hydrogen bonding was observed between ligand and Asn35 and Thr26 of targeted protein. Hydrogen bonding was established for more than 15% of simulation time. In terms of hydrophobic interactions, Pro1 and Pro5 established significant hydrophobic contacts for 30% and 80% of simulation time respectively. These interactions were contributing substantially in stabilising the protein ligand complex. Figure 8 is representing the contact profile for simulated complex.

Figure 8.

Contact profile for protein-ligand complex. Green coloured peaks are representing hydrogen bonding while purple peaks are representing hydrophobic interactions. Blue coloured histograms are water bridges.

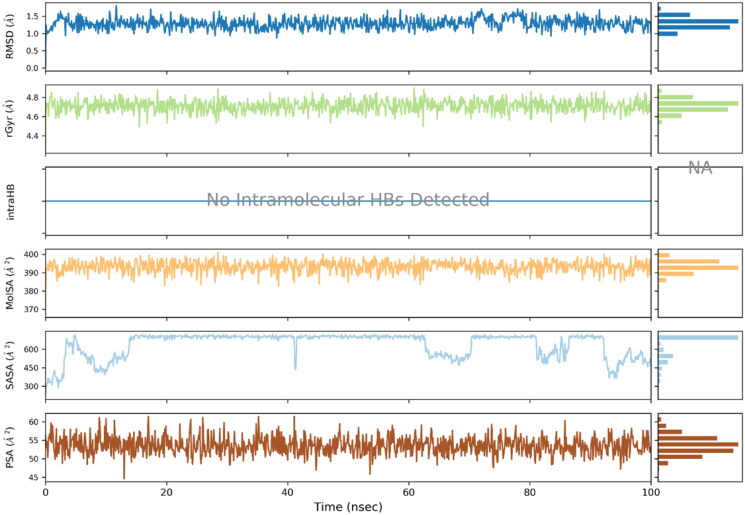

Ligand properties were also evaluated to determine its stability and variation profile. Atomic fluctuations, solvent accessibility and compactness of ligand remained in the acceptable limit. The ligand properties are illustrated in the Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Ligand properties analysed using various analytical metrics.

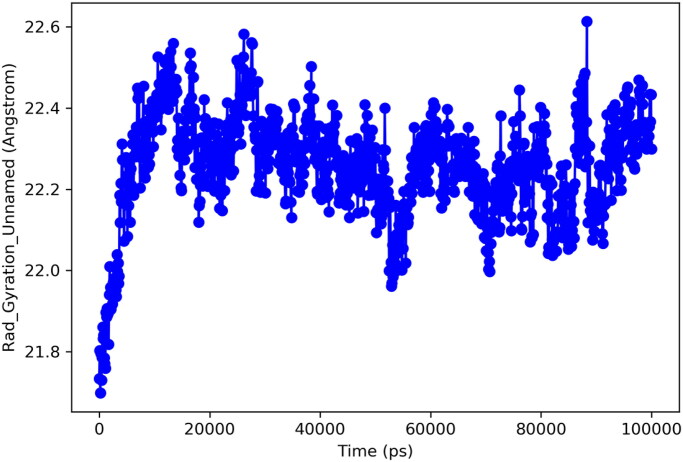

Radius of gyration (Rg) is important analytic metrics for determination of centre of mass and compactness of protein. A low value for Rg depicts the high compactness and low structural variations of the protein. Whereas, high Rg is predictive of poor stability and more structural changes of a particular protein. In current study, protein exhibited optimal structural changes with Rg ranges for 21.8–22.6 Å. These findings predict that mass of protein was equally distributed around single point and remained well compact through simulated trajectory. Figure 10 is illustrating the Rg for targeted protein.

Figure 10.

Radius of gyration.

Conclusions

The quinolinyl based iminothiazoline analogues 6(a–j) containing alkyl and aryl groups were prepared and characterised by FT-IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR and HPLC-MS. All the analogues were evaluated for alkaline phosphatase inhibition potential. The compound (E)-N-(4-(4-bromophenyl)-3-(quinolin-3-yl)thiazol-2(3H)-ylidene)benzamide 6g exhibited the maximum alkaline phosphatase inhibitory effect (IC50 = 0.337 ± 0.015 µM comparative to other synthesised derivatives and reference compound KH2PO4 (IC50 = 5.245 ± 0.477 µM). DFT studies were performed and compounds 6j, 6g and 6h were found to be the reactive ones among all compounds. Kinetic analysis exhibited that the analogue (6g) was non-competitive inhibitor of alkaline phosphatase with Ki value of 0.47 µM. The molecular docking displayed that the compounds 6d, 6e, 6g and 6i possesses efficient binding affinity but we considered 6g because the result of docking is proved confirmatory for kinetic analysis as well that our 6g compound is a good inhibitor of the targeted protein alkaline phosphatase. Comprehensive MD investigations were carried out in an effort to further evaluate the validity of docking data, further validating the inhibitory capability of 6g. The quinolinyl and aryl or alkyl moiety in iminothiazolines play significant role in alkaline phosphatase inhibition potential. The derivative 6g may be considered to design more potent drug for the alkaline phosphatase inhibition.

Supplementary Material

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Researcher Supporting Project Number (RSP-2021/259) King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia.

Author contributions

A.S. devised and supervised the study for M.N.M. Experimental work has been carried out by M.N.M., S.A.E., M.A., and P.A.C. M.A. has carried out the molecular docking investigations. The DFT studies were performed by M.A., H.E.S, M.Z.A. and H.R. The simulation and kinetics studies were performed by M.S. The manuscript write up was carried out by S. A. E, M. A. and M.N.M. The S.J.K, A.H., H.Y.A, F.A.A, and M.S took part in revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript for publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All research data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Straus DS, Glass CK.. Anti-inflammatory actions of PPAR ligands: new insights on cellular and molecular mechanisms. Trends Immunol. 2007;28(12):551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang TC, Wang JK, Hung MW, Chiao CH, Tsai LC, Chang GG.. Regulation of the expression of alkaline phosphatase in a human breast-cancer cell line. Biochem J. 1994;303(1):199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.al‐Rashida M, Iqbal J.. Therapeutic potentials of ecto‐nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase, ecto‐nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase, ecto‐5′‐nucleotidase, and alkaline phosphatase inhibitors. Med Res Rev. 2014;34(4):703–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali AT, Penny CB, Paiker JE, Psaras G, Ikram F, Crowther NJ.. The effect of alkaline phosphatase inhibitors on intracellular lipid accumulation in preadipocytes isolated from human mammary tissue. Ann Clin Biochem. 2006;43(Pt 3):207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llinas P, Stura EA, Ménez A, Kiss Z, Stigbrand T, Millán JL, Le Du MH.. Structural studies of human placental alkaline phosphatase in complex with functional ligands. J Mol Biol. 2005;350(3):441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sundström B, Johansson B, Hietala SO, Stigbrand T.. Radio-immunolocalization in nude mice using anticytokeratin monoclonal antibodies. Tumour Biol. 1990;11(3):158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orsaria M, Londero AP, Marzinotto S, Di Loreto C, Marchesoni D, Mariuzzi L.. Placental type alkaline phosphatase tissue expression in ovarian serous carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2016;17(4):479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanschkow M, Boulet N, Kempf E, Bouloumié A, Kiess W, Stein R, Körner A, Landgraf K.. Expression of the adipocyte progenitor markers MSCA1 and CD36 is associated with adipose tissue function in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(2):e836–e851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuin A, Poelstra K, de Jager-Krikken A, Bok L, Raaben W, Velders MP, Dijkstra G.. Role of alkaline phosphatase in colitis in man and rats. Gut. 2009;58(3):379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su F, Brands R, Wang Z, Verdant C, Bruhn A, Cai Y, Raaben W, Wulferink M, Vincent JL.. Beneficial effects of alkaline phosphatase in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2182–2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alam SN, Yammine H, Moaven O, Ahmed R, Moss AK, Biswas B, Muhammad N, Biswas R, Raychowdhury A, Kaliannan K, et al. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase prevents antibiotic-induced susceptibility to enteric pathogens. Ann Surg. 2014;259(4):715–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson HC. The role of matrix vesicles in physiological and pathological calcification. Curr Opin Orthop. 2007;18(5):428–433. [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Heijde D, Kivitz A, Schiff MH, Sieper J, Dijkmans BAC, Braun J, Dougados M, Reveille JD, Wong RL, Kupper H, ATLAS Study Group, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(7):2136–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandt J, Khariouzov A, Listing J, Haibel H, Sörensen H, Grassnickel L, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J, Braun J.. Six‐month results of a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of etanercept treatment in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(6):1667–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, Sieper J, DeWoody K, Williamson P, Braun J, Ankylosing Spondylitis Study for the Evaluation of Recombinant Infliximab Therapy Study Group. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(2):582–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antoni C, Krueger GG, de Vlam K, Birbara C, Beutler A, Guzzo C, Zhou B, Dooley LT, Kavanaugh A, IMPACT 2 Trial Investigators . Infliximab improves signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: results of the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(8):1150–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Chang L, Pellet-Rostaing S, Liger F, Lemaire M, Buchet R, Wu Y.. Synthesis and evaluation of benzo [b] thiophene derivatives as inhibitors of alkaline phosphatases. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17(20):7290–7300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narisawa S, Harmey D, Yadav MC, O'Neill WC, Hoylaerts MF, Millán JL.. Novel inhibitors of alkaline phosphatase suppress vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(11):1700–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maslat AO, Abussaud M, Tashtoush H, Al-Talib M.. Synthesis, antibacterial, antifungal and genotoxic activity of bis-1, 3, 4-oxadiazole derivatives. Pol J Pharmacol. 2002;54(1):55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barsu N, Sen M, Premkumar JR, Sundararaju B.. Cobalt (iii) catalyzed C–8 selective C–H and C–O coupling of quinoline N-oxide with internal alkynes via C–H activation and oxygen atom transfer. Chem Commun (Camb)). 2016;52(7):1338–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baird JK, Rieckmann KH.. Can primaquine therapy for vivax malaria be improved? Trends Parasitol. 2003;19(3):115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hargrave KD, Hess FK, Oliver JT.. N-(4-Substituted-thiazolyl) oxamic acid derivatives, new series of potent, orally active antiallergy agents. J Med Chem. 1983;26(8):1158–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher RS, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, Elger C, Genton P, Lee P, Engel J.. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia. 2005;46(4):470–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Ansary SL, Hassan GS, Abdel Rahman DE, Farag NA, Hamed MI, Baset MA.. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of some new succinimide, 2-iminothiazoline and oxazine derivatives based benzopyrone as anticonvulsant agents. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;8(4):222–228. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larik FA, Saeed A, Faisal M, Hamdani S, Jabeen F, Channar PA, Mumtaz A, Khan I, Kazi MA, Abbas Q, et al. Synthesis, inhibition studies against AChE and BChE, drug-like profiling, kinetic analysis and molecular docking studies of N-(4-phenyl-3-aroyl-2 (3H)-ylidene) substituted acetamides. J Mol Struct. 2020;1203:127459. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma PK, Sawhney SN, Gupta A, Singh GB, Bani S.. Synthesis and antiinflammatory activity of some 3-(2-thiazolyl)-1, 2-benzisothiazoles. Indian J Chem B. 1998;37:376–381. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saeed A, Al-Masoudi NA, Pannecouque C.. In-vitro anti-HIV activity of new thiazol-2-ylidene substituted benzamide analogues. Der Pharma Chem. 2012;4(1):106–115. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sondhi SM, Singh N, Lahoti AM, Bajaj K, Kumar A, Lozach O, Meijer L.. Synthesis of acridinyl-thiazolino derivatives and their evaluation for anti-inflammatory, analgesic and kinase inhibition activities. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13(13):4291–4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuji K, Ishikawa H.. Synthesis and anti-pseudomonal activity of new 2-isocephems with a dihydroxypyridone moiety at C-7. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1994;4(13):1601–1606. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saeed S, Hussain R, Ali M.. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of N‐[(2 Z)‐3‐(4, 6‐Substitutedpyrimidin‐2‐yl)‐4‐phenyl‐1, 3‐thiazol‐2 (3 H)‐ylidene]‐3, 5‐dinitrobenzamide Analogues. J Heterocyclic Chem. 2013;50(2):237–243. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rokach J, Girard Y, Hamel P, Reader G, Rooney CS, Mandel LR, Cragoe EJ, Zacchei AG.. Inhibitors of indoleethylamine N-methyltransferase. Derivatives of 3-methyl-2-thiazolidinimine. In vitro, in vivo, and metabolic studies. J Med Chem. 1980;23(7):773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saeed A, Rafique H.. Synthesis of new N-[3-(Benzo [d] thiazol-2-yl)-4-methylthiazol-2 (3H)-ylidene] substituted benzamides. Turk J Chem. 2013;37(6):909–916. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomizawa M, Cowan A, Casida JE.. Analgesic and toxic effects of neonicotinoid insecticides in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001;177(1):77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hosseinimehr SJ, Shafiee A, Mozdarani H, Akhlagpour S.. Radioprotective effects of 2-iminothiazolidine derivatives against lethal doses of gamma radiation in mice. J Radiat Res. 2001;42(4):401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chowdhury R, Candela-Lena JI, Chan MC, Greenald DJ, Yeoh KK, Tian YM, McDonough MA, Tumber A, Rose NR, Conejo-Garcia A, et al. Selective small molecule probes for the hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) prolyl hydroxylases. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8(7):1488–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manaka A, Ishii T, Takahashi K, Sato M.. 2-Acylimino-3-alkyl-3H-thiazoline derivatives: one-pot, three-component condensation synthesis of novel β-turn mimics. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46(3):419–422. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim DS, Jeong YM, Park IK, Hahn HG, Lee HK, Kwon SB, Jeong JH, Yang SJ, Sohn UD, Park KC, et al. A new 2-imino-1, 3-thiazoline derivative, KHG22394, inhibits melanin synthesis in mouse B16 melanoma cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30(1):180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pietrancosta N, Moumen A, Dono R, Lingor P, Planchamp V, Lamballe F, Bähr M, Kraus JL, Maina F.. Imino-tetrahydro-benzothiazole derivatives as p53 inhibitors: discovery of a highly potent in vivo inhibitor and its action mechanism. J Med Chem. 2006;49(12):3645–3652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heravi MM, Moghimi S.. An efficient synthesis of thiazol-2-imine derivatives via a one-pot, three-component reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53(4):392–394. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Assis DB, Aragão Neto HC, da Fonsêca DV, de Andrade HHN, Braga RM, Badr N, Maia MDS, Castro RD, Scotti L, Scotti MT, et al. Antinociceptive activity of chemical components of essential oils that involves docking studies: a review. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang L, Duy DL, Mébarek S, Popowycz F, Pellet-Rostaing S, Lemaire M, Buchet R.. Synthesis and evaluation of thiophenyl derivatives as inhibitors of alkaline phosphatase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21(8):2297–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azarakhshi F, Khaleghian M, Farhadyar N.. DFT study and NBO analysis of conformational properties of 2-substituted 2-Oxo-1, 3, 2-dioxaphosphorinanes and their dithia and diselena analogs. Lett Org Chem. 2015;12(7):516–522. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frisch M, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, et al. Gaussian 09, Revision B. 01. Wallingford (CT): Gaussian, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Rashida M, Iqbal J.. Inhibition of alkaline phosphatase: an emerging new drug target. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2015;15(1):41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Channar SA, Channar PA, Saeed A, Alsfouk AA, Ejaz SA, Ujan R, Noor R, Bilal MS, Abbas Q, Hussain Z, et al. Exploring thiazole-linked thioureas using alkaline phosphatase assay, biochemical evaluation, computational analysis and structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies. Med Chem Res. 2022;31(10):1792–1802. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bauernschmitt R, Häser M, Treutler O, Ahlrichs R.. Calculation of excitation energies within time-dependent density functional theory using auxiliary basis set expansions. Chem Phys Lett. 1997;264(6):573–578. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calais JL. Orthonormalization and symmetry adaptation of crystal orbitals. Int J Quantum Chem. 2009;28(S19):655–667. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weigend F, Ahlrichs R.. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2005;7(18):3297–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hossen J, Ali MA, Reza S.. Theoretical investigations on the antioxidant potential of a non-phenolic compound thymoquinone: a DFT approach. J Mol Model. 2021;27(6):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parr RG, Yang W.. Density functional theory of atoms and molecules. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 1989: p. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schäfer A, Huber C, Ahlrichs R.. Fully optimized contracted Gaussian basis sets of triple zeta valence quality for atoms Li to Kr. J Chem Phys. 1994;100(8):5829–5835. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bartolotti LJ, Flurchick K.. An introduction to density functional theory. Rev Comput Chem. 1996;7:187–260. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thanikaivelan P, Subramanian V, Raghava Rao J, Unni Nair B.. Application of quantum chemical descriptor in quantitative structure activity and structure property relationship. Chem Phys Lett. 2000;323(1–2):59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dennington R, Keith T, Millam J, Eppinnett K, Hovell WL, Gilliland R.. GaussView v.5.0.9 visualizer and builder. Wallingford (CT): Gaussian Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iqbal Z, Ashraf Z, Hassan M, Abbas Q, Jabeen E.. Substituted phenyl [(5-benzyl-1, 3, 4-oxadiazol-2-yl) sulfanyl] acetates/acetamides as alkaline phosphatase inhibitors: synthesis, computational studies, enzyme inhibitory kinetics and DNA binding studies. Bioorg Chem. 2019;90:103108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saeed A, Saddique G, Ali Channar P, Ali Larik F, Abbas Q, Hassan M, Raza H, Fattah TA, Seo SY.. Synthesis of sulfadiazinyl acyl/aryl thiourea derivatives as calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase inhibitors, pharmacokinetic properties, lead optimization, Lineweaver-Burk plot evaluation and binding analysis. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018;26(12):3707–3715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abbasi MA, Nazir M, Ur-Rehman A, Siddiqui SZ, Hassan M, Raza H, Shah SAA, Shahid M, Seo SY.. Bi‐heterocyclic benzamides as alkaline phosphatase inhibitors: mechanistic comprehensions through kinetics and computational approaches. Arch Pharm. 2019;352(3):1800278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Molecular Operating Environment (MOE). Montreal (QC): Chem Comput Group Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heinzerling L, Klein R, Rarey M.. Fast force field‐based optimization of protein–ligand complexes with graphics processor. J Comput Chem. 2012;33(32):2554–2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Al‐Hazmi GAA, Abou‐Melha KS, El‐Metwaly NM, Althagafi I, Shaaban F, Zaky R.. Green synthesis approach for Fe (III), Cu (II), Zn (II) and Ni (II)‐Schiff base complexes, spectral, conformational, MOE‐docking and biological studies. Appl Organomet Chem. 2020;34(3):e5403. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuan S, Chan HS, Hu Z.. Using PyMOL as a platform for computational drug design. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Mol Sci. 2017;7(2):e1298. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laskowski RA, Swindells MB.. LigPlot+: multiple ligand–protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51(10):2778–2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang Y, Zhang TJ, Tu S, Zhang ZH, Meng FH.. Identification of novel Src inhibitors: pharmacophore-based virtual screening, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations. Molecules. 2020;25(18):4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shivakumar D, Williams J, Wu Y, Damm W, Shelley J, Sherman W.. Prediction of absolute solvation free energies using molecular dynamics free energy perturbation and the OPLS force field. J Chem Theory Comput. 2010;6(5):1509–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martyna GJ, Tobias DJ, Klein ML.. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J Chem Phys. 1994;101(5):4177–4189. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bowers KJ, Chow E, Xu H, Dror RO, Eastwood MP, Gregersen BA, Klepeis JL, Kolossvary I, Moraes MA, Sacerdoti FD, et al. Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters. Paper presented at: SC'06. Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing. Tampa (FL): IEEE; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luty BA, Davis ME, Tironi IG, Van Gunsteren WF.. A comparison of particle-particle, particle-mesh and Ewald methods for calculating electrostatic interactions in periodic molecular systems. Mol Simul. 1994;14(1):11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hospital A, Goñi JR, Orozco M, Gelpí JL.. Molecular dynamics simulations: advances and applications. Adv Appl Bioinform Chem. 2015;8:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choudhary MI, Shaikh M, Tul-Wahab A, Ur-Rahman A.. In silico identification of potential inhibitors of key SARS-CoV-2 3CL hydrolase (Mpro) via molecular docking, MMGBSA predictive binding energy calculations, and molecular dynamics simulation. PLos One. 2020;15(7):e0235030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All research data will be made available on request.