Abstract

Background

Cigarette price increases have been associated with increases in smoking cessation, but relatively little is known about this relationship at the level of individual smokers. To address this and to inform tax policy, the goal of this study was to apply a behavioural economic approach to the relationship between the price of cigarettes and the probability of attempting smoking cessation.

Methods

Adult daily smokers (n=1074; ie, 5+ cigarettes/day; 18+ years old; ≥8th grade education) completed in-person descriptive survey assessments. Assessments included estimated probability of making a smoking cessation attempt across a range of cigarette prices, demographics and nicotine dependence.

Results

As price increases, probability of making a smoking cessation attempt exhibited an orderly increase, with the form of the relationship being similar to an inverted demand curve. The largest effect size increases in motivation to make a quit attempt were in the form of ‘left-digit effects,’ (ie, maximal sensitivity across pack price whole-number changes; eg, US$5.80–6/pack).

Significant differences were also observed among the left-digit effects, suggesting the most substantial effects were for price changes that were most market relevant. Severity of nicotine dependence was significantly associated with price sensitivity, but not for all indices.

Conclusions

These data reveal the clear and robust relationship between the price of cigarettes and an individual’s motivation to attempt smoking cessation. Furthermore, the current study indicates the importance of left-digit price transitions in this relationship, suggesting policymakers should consider relative price positions in the context of tax changes.

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use remains a major cause of preventable morbidity and mortality worldwide,1 2 and increasing the number of individuals who successfully quit smoking remains a high priority for public health.3 One of the major factors in smoking cessation is the price of cigarettes.4 For example, tax increases have been shown to significantly increase quit attempts.5 6 To date, however, most of the studies on the relationship between cigarette price and smoking cessation are from the domain of applied microeconomics. These investigations typically examine direct or indirect indicators using natural experiments, such as comparisons across time in a catchment area that implements a tobacco tax increase. An obvious strength of these studies is that they map on to the manifest changes that take place. The studies also typically have large sample sizes, making them relatively representative. They are not without weaknesses, however. For example, the underlying relationship between price and cessation is typically estimated from only a small number of price changes, most often pretax/ post-tax increase. Further, the price changes are preordained by policy changes and cannot be experimentally manipulated, which prevents the examination of diverse possible price changes.

A number of these challenges can be addressed by applying behavioural economics, the integration of psychology and economics, to understand the relationship between cigarette price and quit likelihood. For smoking cessation, the most relevant domain of behavioural economic research is the study of tobacco demand (ie, the relationship between price and cigarette consumption). A number of human laboratory studies have systematically examined in vivo cigarette consumption under conditions of escalating cost,7-9 permitting comprehensive examination of cigarette demand under controlled conditions, and confirming the prototypic form of the cigarette demand curve. Similarly, Cigarette Purchase Tasks10 (CPT) that collect estimated cigarette consumption at escalating levels of price allow a full examination of an individual’s cigarette demand curve and the assessment of several indicators of demand. These indicators have been shown to be significantly positively associated with smoking rate, nicotine dependence and in vivo smoking topography.11-14 Most recently, a high resolution CPT was used to clarify the most sensitive portions of the demand curve to inform tax policy.15 This study indicated the substantial effects of price on cigarette consumption and the particularly potent ‘left-digit effects,’ or the largest proportionate decreases in cigarette consumption at the transitions from one whole-number pack price to the next (eg, US$4.80–5). Although the left-digit phenomenon has been identified in purchasing behaviour previously,16-19 this was the first study to identify its salience in cigarette consumption.

Importantly, the preceding studies focused on the relationship between price and estimated consumption, but not price and motivation for a quit attempt. These are related concepts, both being forms of price sensitivity, but they reflect distinct behavioural processes. For the former, a person can reduce their smoking without necessarily planning on quitting; for the latter, the individual is identifying the prices at which point they would attempt to terminate smoking permanently. No previous studies have applied a behavioural economic approach to understanding the relationship between the price of cigarettes and smoking cessation motivation. This was the goal of the current study. Using an approach adapted from the CPT methodology, we systematicallyexamined the relationship between the price of cigarettes and the estimated likelihood of attempting to quit smoking. Based on the existing health economics literature, we predicted that cessation motivation would increase with increasing price. However, we predicted that the relationship would not be a consistent monotonic increase, but that there would be varying levels of price sensitivity across prices, akin to price effects on simple consumption.11-14 Additionally, we predicted that left-digit effects would also be present, reflected in disproportionately high price sensitivity across whole-dollar pack price changes. Finally, the study examined two individual-level variables, nicotine dependence and income, as predictors of price sensitivity.

METHOD

Participants

These data were collected as part of a project to inform tobacco tax policy using behavioural economics funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.20 A sample of 1124 daily smokers were enrolled from three sites: Athens, Georgia (84%), Providence, Rhode Island (11%) and Aiken, South Carolina (5%). Eligibility criteria were: (1) 18+ years old; (2) 5+ cigarettes/day; (3) ≥8th grade education. Of these, 4 participants were excluded for improper responding (ie, reporting greater than 100% probability), 3 for excessive missing data (ie, >10% of Probability of Smoking Cessation Measure (PSCM) items missing), and 46 for inconsistent/erratic responding (ie, >3 contradictions on the PSCM, reflecting random responding). The final sample (n=1074) was primarily white (67%) and African–American (25%), with small proportions of other racial backgrounds (Asian—3%; American Indian/Alaskan native—1%; other—1%; Pacific islander—0.1%; mixed race—3%), with a small percentage reported Hispanic ethnicity (2%). Participants were generally male (60%); in their early thirties (M=31.62, SD=12.66); and of low income (median=<US$15 000, IQR=<US$15 000 to US$30 000–45 000). Smoking characteristics are provided in table 1. Site-specific characteristics and comparisons between sites are provided in online supplementary materials. No significant site differences were present on any of the PSCM indices.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n=1074)

| Characteristic | %/Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| C/D | 16.31 (10.46) |

| FTND | 4.18 (2.49) |

| Price/pack | $4.58 ($0.93) ($0.23/cigarette) |

| Intensity | 11.39% (23.94) |

| Breakpoint | $0.85 (1.48) |

| P50 price | $0.50 (0.85) |

C/D, cigarettes/day; FTND, Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence; Price/pack, the participants’ self-reported typical price of a pack of cigarettes; $, US dollar.

Procedures

Participants completed a single 90 min in-person assessment in groups of ∼10 in a quiet conference room with adequate space and privacy. The protocol involved informed consent, assessment instructions, assessment completion and debriefing. All procedures were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards.

Assessments

The primary assessment was the PSCM, which was developed for this study and assessed the percent likelihood that an individual would attempt smoking cessation (eg, quit probability) at escalating cigarette prices. We considered assessing estimated likelihood of successfully quitting smoking, but this is a ‘double-barrelled’ question, including both the likelihood of attempting and, given an attempt, the estimated likelihood of success. Therefore, we focused on simply whether participants would attempt to quit smoking, irrespective of whether they thought they would be successful. The PSCM comprised 73 prices, starting at no cost (free) and increasing to US$10/cigarette (US$200/pack). Prices per cigarette increased in 1¢ increments from 0¢ to 50¢, 4¢ increments from 50¢ to 98¢, and US$1 increments from US$1 to US$10. Equivalent prices per pack were provided next to each individual price. Of note, although probabilities are formally presented in fractions, we used percent likelihood as a mathematically equivalent metric for participant responding to aid comprehension and responding (eg, a response of 5% rather than 0.05). The PSCM instructions and initial items are provided in the online supplementary materials. Additional assessments included demographics and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence21 (FTND), a validated assessment of nicotine dependence.

Data analysis

A small number of data points were missing for FTND (n=4) and income (n=9); these values were not imputed and the associated participants were not included in analyses using these variables. Three dependent variables from the PSCM were adapted from the CPT methodology and were defined for each participant as: (1) intensity (ie, motivation at zero price); (2) P50, (ie, cigarette price corresponding to 50% quit probability, when orientation toward attempting to quit is at least equal to or greater than orientation toward not quitting) and (3) breakpoint (ie, cigarette price corresponding to 100% quit probability). Sensitivity to price effects between adjacent prices was defined as the ratio of the proportionate change in quit attempt probability divided by the proportionate change in price (%Δ quit attempt (QA)/%ΔP). An omnibus analysis of the effect of price on consumption was conducted using a one-way within-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA). Given the large number of potential comparisons, 95% CIs are provided instead of follow-up tests. For descriptive purposes, effect size differences between adjacent prices were calculated as Cohen’s d using the difference in values divided by the pooled SD. The presence of left-digit effects was statistically tested by generating a mean change across left-digit pack price transitions and non-left-digit transitions, and comparing the two using a within-subjects ANOVA. Additionally, a within-subjects ANOVA was conducted across left-digit transitions to determine whether systematic differences were present. These left-digit analyses were restricted to data ≤US$0.50/cigarette because, above that price, the inter-price increments were substantially larger, pack prices did not clearly map on to left-digit transitions, and proportions of participants at maximum PSCM response level were high, restricting range. Effect sizes were calculated as η2 in ANOVA-based analyses. Associations between PSCM indices, smoking variables and income were examined using Pearson’s r.

RESULTS

Relationship between price and motivation to attempt smoking cessation

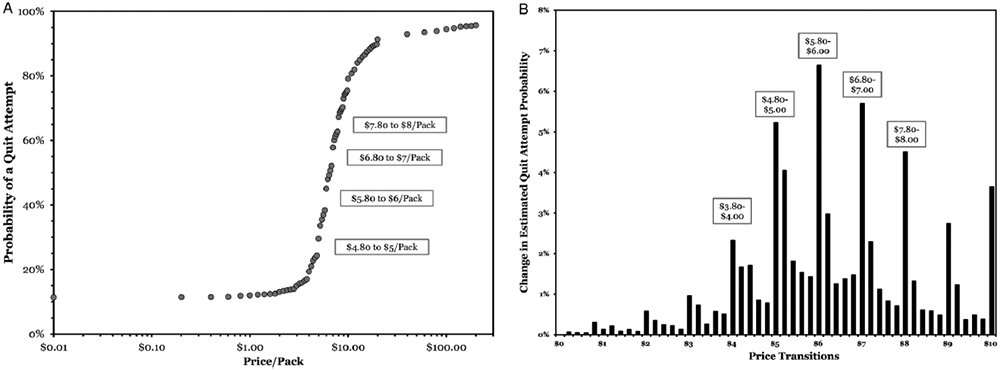

Descriptive statistics for the PSCM indices are given in table 1. Probability of attempting to make a smoking cessation attempt substantially increased as a function of increases in cigarette price (figure 1). Motivation was initially low (∼10%) and relatively insensitive from zero price to approximately 15¢/cigarette. It then increased steeply from 15¢ to US$1/cigarette, levelling off at ∼95%. The sigmoidal form of the overall curve effectively conformed to an inverted demand curve, with an inelastic initial period (US$0–15¢/cigarette) and a subsequently elastic period (15¢–US$1) until very high prices. The arithmetic aggregated elasticity (%ΔQA/%ΔP) across prices was 0.76.

Figure 1.

Relationship between the price of cigarettes and estimated likelihood of attempting smoking cessation from US$0 to US$10/cigarette. (A) Presents the overall curve reflecting the relationship between price/pack and estimated smoking cessation attempt likelihood. Prices per pack are presented on the x axis, with zero price replaced with $0.01 to permit logarithmic coordinates. (B) Presents changes in probability across prices. In both panels, text boxes illustrate ‘left-digit’ effects.

The overall within-subjects ANOVA revealed a statistically significant, very large magnitude effect of price, F(72, 77 184)=2719.93, p<0.00001, η2=0.72. Complete means, 95% CIs, and effect sizes for adjacent price changes are provided in online supplementary materials. Effect size differences across price changes were highly variable (ds=0.06–0.44) and the largest increases in probability of a quit attempt between adjacent prices were observed as pack prices increased from one whole-dollar amount to the next whole-dollar amount (eg, US$4.80–5), reflecting pack price left-digit effects. The ANOVA of changes at left-digit transitions to non-left-digit transitions revealed a significant large magnitude difference, F(1, 1073)=455.71, p<0.00001, η2=0.30, with left-digit transitions associated with an average increase of 3.25% (SEM=0.10) and non-left-digit transitions associated with an average of 0.88% (SEM=0.03), an almost fourfold difference. Illustrative price changes prior to and across left-digit transitions are provided in table 2. Across the left digit transitions, proportionate price effects on motivation to quit (%ΔQA/%ΔP) were typically fivefold larger compared with the preceding price change of similar proportionate magnitude.

Table 2.

Illustrative effects of price increases on probability of a smoking cessation attempt across left-digit transitions

| Unit prices |

Pack prices | QA means (%) |

Absolute increase |

Cohen’s d |

% QA increase |

% P increase |

%ΔQA/%ΔP | Medians | % P50 | % BP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18¢–19¢ | $3.60–$3.80 | 16.52–17.03 | 0.51 | 0.11 | 3.05 | 5.56 | 0.55 | 0–0 | 17.50–17.97 | 4.19–4.38 |

| 19¢–20¢ | $3.80–$4.00 | 17.03–19.35 | 2.32 | 0.26 | 13.67 | 5.26 | 2.6 | 0–0 | 17.97–21.32 | 4.38–4.84 |

| 23¢–24¢ | $4.60–$4.80 | 23.58–24.36 | 0.78 | 0.19 | 3.3 | 4.35 | 0.76 | 10–10 | 26.33–27.00 | 5.49–5.77 |

| 24¢–25¢ | $4.80–$5.00 | 24.36–29.58 | 5.22 | 0.34 | 21.44 | 4.17 | 5.15 | 10–20 | 27.00–34.17 | 5.77–8.47 |

| 28¢–29¢ | $5.60–$5.80 | 36.96–38.39 | 1.43 | 0.22 | 3.86 | 3.57 | 1.08 | 30–30 | 42.09–43.58 | 12.85–13.51 |

| 29¢–30¢ | $5.80–$6.00 | 38.39–45.03 | 6.64 | 0.44 | 17.29 | 3.45 | 5.01 | 30–50 | 43.58–51.02 | 13.51–18.62 |

| 33¢–34¢ | $6.60–$6.80 | 50.62–52.10 | 1.48 | 0.22 | 2.91 | 3.03 | 0.96 | 50–50 | 57.73–58.85 | 21.97–23.21 |

| 34¢–35¢ | $6.80–$7.00 | 52.10–57.79 | 5.69 | 0.43 | 10.94 | 2.94 | 3.72 | 50–51 | 58.85–64.90 | 23.21–29.24 |

| 38¢–39¢ | $7.60–$7.80 | 62.03–62.74 | 0.71 | 0.2 | 1.15 | 2.63 | 0.44 | 70–70 | 69.55–70.11 | 33.71–34.36 |

| 39¢–40¢ | $7.80–$8.00 | 62.74–67.24 | 4.5 | 0.41 | 7.17 | 2.56 | 2.8 | 70–75 | 70.11–74.49 | 34.36–40.32 |

| 43¢–44¢ | $8.60–$8.80 | 69.77–70.25 | 0.48 | 0.21 | 0.68 | 2.33 | 0.29 | 80–85 | 76.44–76.63 | 42.74–43.11 |

| 44¢–45¢ | $8.80–$9.00 | 70.25–72.99 | 2.74 | 0.36 | 3.9 | 2.27 | 1.72 | 85–90 | 76.63–79.70 | 43.11–47.39 |

| 48¢–49¢ | $9.60–$9.80 | 75.06–75.44 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.5 | 2.08 | 0.24 | 99–100 | 81.84–82.31 | 49.81–50.09 |

| 49¢–50¢ | $9.80–$10.00 | 75.44–79.08 | 3.64 | 0.36 | 4.83 | 2.04 | 2.37 | 100–100 | 82.31–85.85 | 50.09–55.96 |

In each case, the left-digit price transition and the prior price transition are reported. P, price; QA, estimated probability of making a quit attempt; % BP, percent of sample at breakpoint (ie, reporting 100% probability of making a quit attempt); % P50, percent of sample at ≥50% probability of making a quit attempt; %ΔQA/%ΔP reflects proportionate price sensitivity; ¢, US cent; $, US dollar.

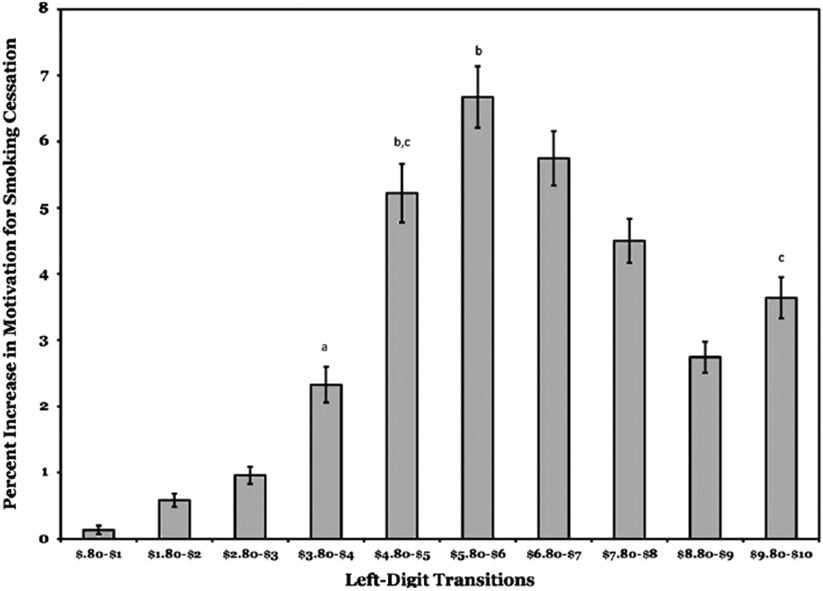

The ANOVA of the individual left-digit effects also revealed a significant effect, F(9, 9657)=55.08, p<0.00001, η2=0.05, indicating significant differences across the transitions. Mean changes are presented in figure 2. Follow-up contrasts revealed significant differences between almost all the changes ( ps<0.05– 0.00001), with a small number of exceptions (figure 2). At low prices, left-digit effects were largely absent, but as prices approached participants’ average actual price for cigarettes, changes at left-digit price transitions increased in magnitude. As price became larger still, and moved further away from participants’ typical price, the magnitude of the left-digit change notably dropped. Median values and proportions of participants at P50 and breakpoint similarly revealed the disproportionate salience of left-digit price transitions (table 2 and see online supplementary materials).

Figure 2.

Differences in magnitudes of left-digit effects across ten price transitions. Significant differences (ps<0.05–0.00001) are present between all changes, with exceptions denoted as follows: a = no significant difference relative to US$8.80–9 price change; b = no significant difference relative to the US$6.80–7 price change; and c = no significant difference relative to US$7.80–8 price change.

Relationship between nicotine dependence and cessation motivation

The FTND was significantly correlated with intensity (r=−0.08; p<0.01) and P50 (r=0.10; p<0.01), but not breakpoint (r=−0.02; p=0.59). That is, individuals with greater nicotine dependence exhibited lower baseline quit motivation and were willing to tolerate higher prices before their motivation to quit was more favourable than not. Income was not correlated with intensity (r=−0.004; p=0.89), P50 (r=−0.003; p=0.93), or breakpoint (r=0.02; p=0.44). Associations among the PSCM indices are provided in online supplementary materials.

DISCUSSION

The goal of the current study was to apply a behavioural economic approach to understanding the relationship between the price of cigarettes and an individual’s probability of making a quit attempt. Consistent with the health economics studies,5 6 we found a clear and robust relationship between price and cessation motivation. Moreover, this study extended the literature with several new findings. To start with, the relationship between price and cessation motivation was revealed to not be monotonic and linear, but exhibited initial price insensitivity that was followed by substantial sensitivity. Furthermore, within the relatively elastic portion of the curve, pack price left-digit effects, or transitions from one whole-number price to the next (eg, US$4.80–5), significantly disproportionately increased cessation motivation. Changes at these interfaces were approximately three times larger than the changes in motivation at other price increases. This converges with previous evidence of left-digit effects in terms of cigarette consumption15 and extends it to motivation for cessation.

Interestingly, significant variability was also observed among the left-digit transitions. When these price changes were examined closely, it was evident that at very low prices, left-digit transitions had very little impact, but that as the prices became increasingly relevant to the participants, they became highly potent. Subsequently, the magnitude of effects decreased as price again became less market-relevant. As illustrated in figure 2, leftdigit effects were most pronounced within a window of prices that were most relevant to the participants. A second nuance that emerges in examining the left-digit transitions pertains to thetransition from US$9.80–10/pack. This price change would be predicted to be particularly robust because it represents a further perceptual change from a 1-dollar digit to 2-dollar digits and the current data support this, albeit obliquely. After the US$5.80–6 transition, the impact of left-digit transitions significantly decreases for three successive transitions (figure 2), but this is reversed for the US$9.80–10 transition, which significantly rebounds.

These findings have a number of potentially important implications. Evidence of left-digit effects suggests that policy makers and tobacco control professionals should be aware that not all price changes are ‘created equal’. The same 20-cent pack price increase, for example, could have dramatically different effects depending on where it falls relative to a left-digit transition. In the current study, the effects of four 20-cent/pack price increases from US$4 to US$4.80 had virtually the same effect as the single 20-cent increase from US$4.80 to US$5. For tobacco tax policy, what this means is that the anticipated effects of price changes should be considered from an absolute standpoint (ie, the amount of the tax increase), and also in terms of the relative position to whole-dollar price changes. A small tax increase may be particularly potent if it pushes the average prices into the next higher price bracket, whereas other larger increases may be less potent because they do not have the salience of a left-digit change. More generally, quantitative models of the elasticity of tobacco demand and motivation to quit would should increasingly integrate the non-linear effects of left-digit transitions.

A second implication of these findings is the use of minimum pack pricing as a novel public health strategy. Minimum pricing laws have historically existed to protect tobacco retailers from predatory business practices,22 but an alternative perspective is to use them to create price ‘floors’ that would prevent pricing or marketing strategies that would maintain prices in the face of tax increases. This, in turn, raises the question of how aware the tobacco industry is of left-digit effects, and whether it intentionally acts to mitigate these effects. For example, in a catchment area where an impending tax increase would push the average pack price into a new whole-dollar amount, it may be that the industry would pass on less of the tax to smokers in order to prevent the disproportionate effect of this price transition. Although there are no studies on this question to date, it is an important future direction. Evidence that the tobacco industry does intentionally seek to offset left-digit price transitions would further support the need for minimum pricing laws to ensure the intended price changes are achieved in the marketplace.

The current study also revealed a number of interesting collateral findings. For example, the form of the smoking cessation motivation curve was virtually a mirror image of a prototypic economic demand curve. This empirically illustrates how treatment motivation has similar curvilinear dynamics to cigarette demand, with negligible price effects at low prices (inelasticity), substantial effects at higher prices (elasticity), and then an asymptotic period above a certain price at which point individuals either reach or approach the maximum. Additionally, this was the first study to directly examine nicotine dependence and income in the context of cigarette prices and smoking cessation motivation. Higher levels of nicotine dependence were significantly associated with intensity (negatively) and P50 ( positively), but not breakpoint. As intensity measured motivation independent of price, this suggests that nicotine dependence was primarily related to motivation to quit in terms of when participants met the putative tipping-point of 50%, but not the more definitive scale maximum, which was somewhat surprising. Of note, for the significant correlations, the magnitudes were relatively small, suggesting that nicotine dependence is not a prepotent factor in the relationship between price and motivation to quit smoking. Also somewhat surprisingly, there was no relationship between income and price sensitivity. Although intuitively one might predict that lower-income individuals would be more motivated to quit with escalating prices, the current data do not support that hypothesis.

Importantly, there are several reasons for caution in interpreting and applying these findings. To start with, the PSCM used estimated likelihood of making a smoking cessation attempt and the extent to which that maps on to actual behaviour is not clear. The behavioural economic literature supports a robust correspondence between performance for hypothetical and actual contingencies,10 23 but not in the area of treatment motivation, leaving the level of correspondence an open question. A related issue is that the assessment context may have permitted a potentially artificially clear focus on the relationship between price and motivation to quit. By contrast, decisions about making an attempt to quit smoking in the natural environment would be unlikely to be framed with the same sort of clarity. Another assumption was that tax increases would be fully passed through to the consumer. This is often the case, but sub-proportionate or supra-proportionate tax pass-throughs have also been reported.24 25 20 Similarly, price increases in this study were treated as aggregated values and we did not make a distinction between state and federal taxes. In terms of the sample, it is worth noting that it was primarily comprised of low-income smokers, creating a somewhat restricted range and potentially contributing to the absence of associations between income and the PSCM indices.

Finally, there is the issue of generalisability. We expect that the relationships between price and motivation to quit would be broadly applicable to smokers, but the pack-level left-digit effects would be expected to be most generalisable to highincome countries where the market conditions are similar to the USA. That is not to say that left-digit effects would not generalise, but, in the context of differences in currency denomination scaling, it is likely that non-linearities would be present at different price transition points. For example, the left-digit transitions of greatest relevance might be an order of magnitude higher in Thailand or India, or even several orders of magnitude higher in Vietnam. These are, of course, empirical questions, and some worth pursuing in future studies. More broadly, however, we would predict that similar left-digit non-linearities will be present between cigarette prices and motivation for smoking cessation, but the specific prices involved will be scaled within a given currency.

A critical final point is that the current study assessed whether a person estimated that they would try to stop smoking at a given level of price, which may or may not translate into successful quitting. Even if cigarette prices motivate smokers to attempt smoking cessation, an ideal tobacco control environment would also provide low-cost, easy-access, evidence-based treatment to optimise their success. A push-and-pull dynamic is necessary, with prices ‘pushing’ smokers to try to quit and high-quality treatment ‘pulling’ individuals to successfully do so. Although increasing the price of tobacco via taxation is a powerful tool, it is not a panacea and is but one element of a coordinated tobacco control strategy.

In sum, using behavioural economics to examine the relationship between the price of cigarettes and an individual’s estimated probability of attempting to quit smoking, the current study revealed a number of important findings. Consistent with previous studies, we found evidence of a very robust relationship between price and quit motivation. Moreover, we found evidence of potent pack price left-digit effects, particularly at the most relevant pack prices, and these non-linear price effects on motivation have direct implications for tax policy. More generally, this study provides further support for using behavioural economics to enhance the tobacco control enterprise.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Lauren R Few, MS; John Acker, MS; Cara Murphy, MS; Monika Stojek, MS; Lauren M Wier, MPH; and the research assistants at the University of Georgia and the University of South Carolina Aiken for their contributions to data collection.

Funding

This project was partially supported by grants from the Substance Abuse Policy Research Program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ( JM) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (K23 AA016936—JM; K23 DA020482—MJC).

Footnotes

Competing interests All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest. Dr MacKillop currently receives grant funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Institute for Research on Pathological Gambling, and serves as a consultant to NIH grants. Drs Murphy and Carpenter currently receive grant funding from NIH and serve as a consultant to NIH grants. Dr Chaloupka currently receives grant funding from NIH, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the YMCA of the USA, the US Department of Agriculture, Canadian Institute of Health Research, the National Institutes on Cancer (Canada), and the American Legacy Foundation.

Ethics approval IRBs at Brown University, University of Georgia, University of South Carolina—Aiken.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses–United States, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57:1226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2004;291:1238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2011: warning about the dangers of tobacco. Washington, DC: World Health Organization Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME. Working Group, International Agency for Research on Cancer. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob Control 2011;20:235–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed MB, Anderson CM, Vaughn JW, et al. The effect of cigarette price increases on smoking cessation in California. Prevention Sci 2008;9:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacFarlane K, Paynter J, Arroll B, et al. Tax as a motivating factor to make a quit attempt from smoking: a study before and after the April 2010 tax increase. J Prim Heal Care 2011;3:283–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson MW, Bickel WK. The behavioral economics of cigarette smoking: the concurrent presence of a substitute and an independent reinforcer. Behav Pharmacol 2003;14:137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson MW, Bickel WK, Kirshenbaum AP. Substitutes for tobacco smoking: a behavioral economic analysis of nicotine gum, denicotinized cigarettes, and nicotine-containing cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend 2004;74:253–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Replacing relative reinforcing efficacy with behavioral economic demand curves. J Exp Anal Behav 2006;85:73–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amlung MT, Acker J, Stojek MK, et al. Is talk “cheap”? An initial investigation of the equivalence of alcohol purchase task performance for hypothetical and actual rewards. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2012;36:716–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Ray LA, et al. Further validation of a cigarette purchase task for assessing the relative reinforcing efficacy of nicotine in college smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharm 2008;16:57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacKillop J, Tidey JW. Cigarette demand and delayed reward discounting in nicotine-dependent individuals with schizophrenia and controls: an initial study. Psychopharmacol 2011;216:91–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy JG, Mackillop J, Tidey JW, et al. Validity of a demand curve measure of nicotine reinforcement with adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend 2011;113:207–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Few LR, Acker J, Murphy C, et al. Temporal stability of a cigarette purchase task. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nic Tob Res 2012;14:761–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacKillop J, Few LR, Murphy JG, et al. High-resolution behavioral economic analysis of cigarette demand to inform tax policy. Addiction 2012;107:2191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basu K Why are so many goods priced to end in nine? And why this practice hurts producers? Econ Let 1997;53:41–4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basu K Consumer cognition and pricing in the nines in oligopolistic markets. J Econ Man Strat 2006;15:125–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacetera N, Pope D, Sydnor J. Heuristic thinking and limited attention in the car market. Amer Econ Rev 2012;102:2206–36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas M, Morwitz V. Penny wise and pound foolish: the left-digit effect in price cognition. J Cons Res 2005;32:52–64. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keeler TE, Hu TW, Barnett PG, et al. Do cigarette producers price-discriminate by state? An empirical analysis of local cigarette pricing and taxation. J Heal Econ 1996;15:499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict 1991;86:1119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State cigarette minimum price laws— United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010;59:389–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madden GJ, Begotka AM, Raiff BR, et al. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;11:139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harding M, Leibtag E, Lovenheim MF. The heterogeneous geographic and socioeconomic incidence of cigarette taxes: evidence from Nielsen homescan data. Am Econ J 2012;4:169–98. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanson A, Sullivan R. The incidence of tobacco taxation: evidence from geographic micro-level data. Natl Tax J 2009;62:677–98. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.