Abstract

Sequential immunization with mycobacterial antigen Ag85B-expressing DNA and Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) was more effective than BCG immunization in protecting against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Depletion of the CD8+ T cells in the immunized mice impaired protection in their spleens, indicating that this improved efficacy was partially mediated by CD8+ T cells.

The incidence of tuberculosis (TB) is increasing due to the human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS pandemic and the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. There is a significant need for more effective vaccines to prevent the transmission of M. tuberculosis. The only vaccine presently available for human use against TB is Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG). Although the protective efficacy of BCG is variable in humans (2), it is effective at reducing the bacterial load in murine TB and serves as a benchmark for the evaluation of new TB vaccines in animal models. To date, the level of protection conferred by BCG vaccination has not been achieved by any other subunit vaccine, including DNA vaccines.

Although protective immunity against TB is essentially mediated by CD4+ T cells (1, 8), CD8+ T cells are also required for resistance against M. tuberculosis infection (17). It is plausible that immunization strategies stimulating both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells should lead to an improved protection against M. tuberculosis infection. In general, immunization with soluble proteins stimulates mostly CD4+ T-cell responses, whereas DNA or viral vaccines induce stronger CD8+ T-cell responses. Recently, a heterologous immunization strategy consisting of priming with plasmid DNA and boosting with recombinant vaccinia virus (VV) has been developed in order to enhance immune responses, particularly the CD8+ T-cell responses, against malaria, and infections caused by simian and human immunodeficiency viruses (7, 12, 13, 15). Further characterization of this heterologous immunization strategy has revealed that the type of immune response induced by a prime-boost strategy is dependent mainly on the nature of the boosting agent. For example, while boosting with proteins or peptides generally stimulates a Th2-driven humoral response, viral boosting enhances primarily a Th1-type cell-mediated immune response (11). We (6) and others (9) previously showed that immunization with a DNA vaccine expressing Ag85B, a major secreted mycobacterial protein, protected mice against M. tuberculosis infection. However, the reduction in bacterial load was lower than that conferred by BCG immunization. The present work was designed to develop an immunization strategy that is more effective than current vaccines, and we hypothesized that a DNA vaccine-based heterologous prime-boost immunization with a suitable boosting agent may enhance protection against M. tuberculosis infection.

To examine the influence of the boosting reagents on the outcome of the immune response, C57BL/6 female mice (ARC, Perth, Western Australia, Australia) were primed with an intramuscular injection of 100 μg of a DNA vaccine expressing Ag85B (DNA-85B) and then boosted with different agents. DNA-85B contained the gene encoding Ag85B, as amplified from M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic DNA (9). Boosts included intramuscular immunization with the same dose of DNA-85B, intravenous injection of 107 PFU of an Ag85B-expressing recombinant VV (VV-85B), subcutaneous inoculation of 10 μg of recombinant Ag85B protein (P-85B) in incomplete Freund's adjuvant, or 105 CFU of BCG (Table 1). BCG (Tokyo strain, ATCC 35737), recombinant P-85B, DNA-85B, control DNA (6), VV-85B, and control VV (16) were prepared as previously described. Mice were immunized twice at 6-week intervals. Six weeks after the last immunization, mice were exposed to M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) in a Middlebrook airborne infection apparatus (Glas-Col, Terre Haute, Ind.). Each mouse received approximately 102 viable bacilli per lung. Lungs, spleens, and blood were collected 4 weeks postinfection.

TABLE 1.

Sequential immunization with DNA-85B and BCG protects mice against aerosol M. tuberculosis infection

| Immunizationa

|

Bacterial load (log10 CFU ± SEM [n = 5])b

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1

|

Expt 2

|

||||

| Prime | Boost | Lung | Spleen | Lung | Spleen |

| None | None | 6.30 ± 0.15 | 4.54 ± 0.21 | 6.49 ± 0.04 | 4.65 ± 0.29 |

| Control DNA | Control VV | ND | ND | 6.43 ± 0.05 | 4.99 ± 0.25 |

| DNA-85B | P-85B | 6.05 ± 0.07 | 3.92 ± 0.17 | ND | ND |

| DNA-85B | VV-85B | 6.10 ± 0.06 | 3.94 ± 0.23 | 5.77 ± 0.08∗∗ | 3.89 ± 0.32∗ |

| DNA-85B | DNA-85B | 5.87 ± 0.15∗ | 4.07 ± 0.14 | 5.97 ± 0.09∗∗ | 4.51 ± 0.18 |

| DNA-85B | BCG | 5.18 ± 0.09∗∗∗ | 2.64 ± 0.26∗∗∗ | 5.18 ± 0.22∗∗∗ | 2.60 ± 0.12∗∗∗ |

| BCG | None | 5.63 ± 0.13∗∗∗ | 3.88 ± 0.32∗ | 5.48 ± 0.07∗∗∗ | 3.78 ± 0.11∗∗ |

| BCG | BCG | 5.53 ± 0.09∗∗∗ | 3.25 ± 0.32∗∗ | ND | ND |

Mice were primed and boosted with the vaccines at 6-week intervals and challenged 6 weeks after the last injection with aerosol M. tuberculosis infection.

The differences in CFU between groups were assessed by analysis of variance. Differences between nonimmunized mice and each of the immunized groups are reported (∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.001; ∗∗∗, P < 0.0001). ND, not determined.

In agreement-with a previous study (6), immunization with two injections of DNA-85B conferred partial protection against M. tuberculosis challenge (Table 1). Although prime-boost with DNA-85B and VV-85B also conferred protection in one of two experiments, the protective efficacy of this strategy was lower than for BCG immunization alone, indicating that viral boosting may not be suitable for vaccination against TB. This finding was not surprising since the prime-boost immunization with DNA and viral vaccines was initially designed to protect against viral infection and the hepatic phase of malaria where CD8+ T cells are the predominant protective cells (11, 14). Interestingly, targeting CD4+ T cells alone may not be sufficient, since boosting with soluble Ag85B protein in adjuvant did not protect mice against TB. Mice which were sequentially immunized with DNA-85B and BCG had significantly lower CFU in their lungs than mice immunized with DNA-85B alone (Table 2). Most importantly; the protection conferred by this strategy was significantly greater than the immunization with one or two injections of BCG (Table 2). While immunization with DNA-85B vaccine was less effective at preventing dissemination of the bacilli to the spleens, immunization with BCG significantly reduced the M. tuberculosis load in the spleen compared to nonimmunized animals (Table 1). The combination of DNA-85B and BCG immunization further improved the protective efficacy of BCG vaccine, with an approximately 100-fold reduction in bacterial load in the spleens, compared to a 10-fold reduction in CFU conferred by immunization with BCG alone (Table 2). Immunization with control DNA or viral vaccines had no effect on the growth of M. tuberculosis in the organs of infected mice (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Sequential immunization with DNA-85B and BCG is superior to vaccination with BCG alone

| Groups (prime/boost) compareda |

P value for differences in b:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Lungs | Spleens | |

| DNA-85B/BCG and none/none | <0.0001∗∗∗ | <0.0001∗∗∗ |

| DNA-85B/BCG and DNA-85B/DNA-85B | 0.0003∗∗ | 0.0003∗∗ |

| DNA-85B/BCG and BCG/none | 0.0104∗ | 0.0011∗ |

| DNA-85B/BCG and BCG/BCG | 0.0389∗ | 0.0765NS |

| BCG/none and BCG/BCG | 0.5427NS | 0.0650NS |

Mice were primed and boosted at 6-week intervals as described for Table 1 and challenged 6 weeks after the last injection with aerosol M. tuberculosis infection.

Differences in CFU between groups as assessed by analysis of variance (NS, nonsignificant; ∗ P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.001; ∗∗∗, P < 0.0001).

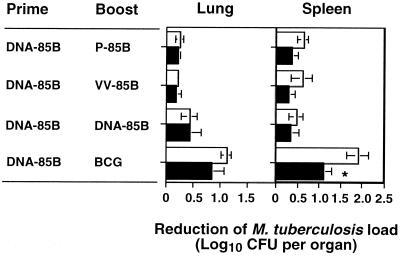

In an attempt to define the immune mechanism leading to this improved protection, CD8+ T cells of mice primed with DNA-85B and boosted with P-85B, VV-85B, DNA-85B, or BCG were depleted during M. tuberculosis infection. The time schedule for vaccination and immunization route were similar as to those in the experiment described above. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg of protein G-purified depleting anti-CD8+ T-cell monoclonal antibody (MAb) YTS169.4 at days -2, -1, 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28 (relative to challenge with M. tuberculosis on day 0). The bacterial loads of MAb-treated and untreated mice were compared at day 30 postinfection (Fig. 1). The MAb treatment significantly reduced the number of CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood, with 89% ± 0.64% reduction compared to immunized, infected animals not treated with MAb YTS169.4 (n = 3). The extent of reduction in peripheral CD8+ T cells was comparable to that in infected spleens (data not shown) (10). This reduction was associated with a significant increase in the CFU in the spleens of the treated mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1), showing that CD8+ T cells stimulated by DNA priming and BCG boosting immunization protected mice against M. tuberculosis infection. In contrast to peripheral blood and spleen, the depletion of CD8+ T cells was less efficient in the M. tuberculosis-infected lungs (75% ± 2.52% reduction; n = 3), and the bacterial loads in the lungs of MAb-treated and untreated mice were not significantly different. This could be a result of reduced efficiency in the depletion of CD8+ T cells in lungs or of the increased proliferation of CD8+ T cells at the site of infection. Alternatively, this may reflect the difference in the immune response between lungs and spleens (4, 5).

FIG. 1.

Improved protection against dissemination of M. tuberculosis to spleens is partially mediated by CD8+ T cells. Immunized mice were left untreated (□) or treated with anti-CD8+ T-cell MAb YTS169.4 (■) during the course of M. tuberculosis infection. Thirty days postinfection, the bacterial load in lungs and spleens was determined. Reduction of bacterial load was expressed as the mean log10 difference in CFU in the organs of immunized and nonimmunized mice (n = 5). The differences in CFU between untreated and anti-CD8+ T-cell MAb-treated animals were compared by Student's t test (∗, P < 0.05).

The success of the novel heterologous prime-boost immunization with DNA and BCG demonstrates that protective efficacy of the current BCG vaccine can be improved by use of a more effective immunization regimen. Several factors may account for this improved efficacy. First, priming with a DNA plasmid may focus the immune responses to one of the dominant mycobacterial antigens. Second, DNA vaccines may contribute to the improved protection against M. tuberculosis infection by priming both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. DNA immunization can stimulate both T-cell subsets (19) and is more potent than mycobacteria at priming naive CD8+ T cells (3, 20). Third, BCG immunization may effectively amplify mycobacterium-specific CD8+ T-cell responses primed by DNA immunization, as the requirements for activation of effector/memory T cells are less stringent than those for their naive counterparts (18). Finally, in contrast to viral boosting, boosting with BCG vaccine greatly enhances the Th1-type CD4+ T-cell response that is essential for immunity against M. tuberculosis.

In conclusion, sequential immunization with DNA-85B and BCG was superior to immunization with either DNA or BCG vaccine alone in this C57BL/6 murine model of tuberculosis. Improved protection was partially dependent on CD8+ T cells, and further reduction of bacterial load may be achieved by incorporating immune adjuvants such as interleukin-12 and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (5) into BCG boosting. Importantly, these findings suggest that a combination of immunizations with DNA vaccines and BCG may be more effective than BCG in the control of TB in humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. The support of the NSW Health Department through its research and development infrastructure grants program is gratefully acknowledged. C.G.F. and U.P. are recipients of Australian Postgraduate Awards.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caruso A M, Serbina N, Klein E, Triebold K, Bloom B R, Flynn J L. Mice deficient in CD4 T cells have only transiently diminished levels of IFN-γ, yet succumb to tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1999;162:5407–5416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colditz G A, Brewer T F, Berkey C S, Wilson M E, Burdick E, Fineberg H V, Mosteller F. Efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Meta-analysis of the published literature. JAMA. 1994;271:698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denis O, Tanghe A, Palfliet K, Jurion F, van den Berg T P, Vanonckelen A, Ooms J, Saman E, Ulmer J B, Content J, Huygen K. Vaccination with plasmid DNA encoding mycobacterial antigen 85A stimulates a CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell epitopic repertoire broader than that stimulated by Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1527–1533. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1527-1533.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng C G, Britton W J. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells mediate adoptive immunity to aerosol infection of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1846–1849. doi: 10.1086/315466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freidag B L, Melton G B, Collins F, Klinman D M, Cheever A, Stobie L, Suen W, Seder R A. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and interleukin-12 improve the efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination in mice challenged with M. tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2948–2953. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2948-2953.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamath A T, Feng C G, Macdonald M, Briscoe H, Britton W J. Differential protective efficacy of DNA vaccines expressing secreted proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1702–1707. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1702-1707.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kent S J, Zhao A, Best S J, Chandler J D, Boyle D B, Ramshaw I A. Enhanced T-cell immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine regimen consisting of consecutive priming with DNA and boosting with recombinant fowlpox virus. J Virol. 1998;72:10180–10188. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.10180-10188.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ladel C H, Daugelat S, Kaufmann S H. Immune response to Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette Guerin infection in major histocompatibility complex class I- and II-deficient knock-out mice: contribution of CD4 and CD8 T cells to acquired resistance. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:377–384. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lozes E, Huygen K, Content J, Denis O, Montgomery D L, Yawman A M, Vandenbussche P, Van Vooren J P, Drowart A, Ulmer J B, Liu M A. Immunogenicity and efficacy of a tuberculosis DNA vaccine encoding the components of the secreted antigen 85 complex. Vaccine. 1997;15:830–833. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muller I, Cobbold S P, Waldmann H, Kaufmann S H. Impaired resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection after selective in vivo depletion of L3T4+ and Lyt-2+ T cells. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2037–2041. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2037-2041.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsay A J, Kent S J, Strugnell R A, Suhrbier A, Thomson S A, Ramshaw J A. Genetic vaccination strategies for enhanced cellular, humoral and mucosal immunity. Immunol Rev. 1999;171:27–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson H L, Montefiori D C, Johnson R P, Manson K H, Kalish M L, Lifson J D, Rizvi T A, Lu S, Hu S L, Mazzara G P, Panicali D L, Herndon J G, Glickman R, Candido M A, Lydy S L, Wyand M S, McClure H M. Neutralizing antibody-independent containment of immunodeficiency virus challenges by DNA priming and recombinant pox virus booster immunizations. Nat Med. 1999;5:526–534. doi: 10.1038/8406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider J, Gilbert S C, Blanchard T J, Hanke T, Robson K J, Hannan C M, Becker M, Sinden R, Smith G L, Hill A V. Enhanced immunogenicity for CD8+ T cell induction and complete protective efficacy of malaria DNA vaccination by boosting with modified vaccinia virus Ankara. Nat Med. 1998;4:397–402. doi: 10.1038/nm0498-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider J, Gilbert S C, Hannan C M, Degano P, Prieur E, Sheu E G, Plebanski M, Hill A V. Induction of CD8+ T cells using heterologous prime-boost immunization strategies. Immunol Rev. 1999;170:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sedegah M, Jones T R, Kaur M, Hedstrom R, Hobart P, Tine J A, Hoffman S L. Boosting with recombinant vaccinia increases immunogenicity and protective efficacy of malaria DNA vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7648–7653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith S M, Malin A S, Lukey P T, Atkinson S E, Content J, Huygen K, Dockrell H M. Characterization of human Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin-reactive CD8+ T cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5223–5230. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5223-5230.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sousa A O, Mazzaccaro R J, Russell R G, Lee F K, Turner O C, Hong S, Van Kaer L, Bloom B R. Relative contributions of distinct MHC class I-dependent cell populations in protection to tuberculosis infection in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4204–4208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swain S L, Croft M, Dubey C, Haynes L, Rogers P, Zhang X, Bradley L M. From naive to memory T cells. Immunol Rev. 1996;150:143–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1996.tb00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tighe H, Corr M, Roman M, Raz E. Gene vaccination: plasmid DNA is more than just a blueprint. Immunol Today. 1998;19:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu X, Stauss H J, Ivanyi J, Vordermeier H M. Specificity of CD8+ T cells from subunit-vaccinated and infected H-2b mice recognizing the 38 kDa antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1669–1676. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.11.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]