Abstract

Background

Beyond guideline-directed treatments aimed at improving cardiac function and prognosis in heart failure (HF), patient-reported outcomes have gained attention.

Purpose

Using a cross-sectional approach, we assessed symptom burden, psychosocial distress, and potential palliative care (PC) needs in patients with advanced stages of HF.

Methods

At a large tertiary care center, we enrolled HF patients in an exploratory pilot study. Symptom burden and psychosocial distress were assessed using the MIDOS (Minimal Documentation System for Patients in PC) questionnaire and the Distress Thermometer (DT), respectively. The 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4) was used to screen for anxiety and depression. To assess PC needs, physicians used the “Palliative Care Screening Tool for HF Patients”.

Results

We included 259 patients, of whom 137 (53%) were enrolled at the Heart Failure Unit (HFU), and 122 (47%) at the outpatient clinic (OC). Mean age was 63 years, 72% were male. New York Heart Association class III or IV symptoms were present in 56%. With a mean 5-year survival 64% (HFU) vs. 69% (OC) calculated by the Seattle Heart Failure Model, estimated prognosis was comparatively good. Symptom burden (MIDOS score 8.0 vs. 5.4, max. 30 points, p < 0.001) and level of distress (DT score 6.0 vs. 4.8, max. 10 points, p < 0.001) were higher in hospitalised patients. Clinically relevant distress was detected in the majority of patients (HFU 76% vs. OC 57%, p = 0.001), and more than one third exhibited at least mild symptoms of depression or anxiety. Screening for PC needs revealed 82% of in- and 52% of outpatients fulfil criteria for specialized palliative support.

Conclusion

Despite a good prognosis, we found multiple undetected and unaddressed needs in an advanced HF cohort. This study’s tools and screening results may help to early explore these needs, to further improve integrated HF care.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Heart failure, Palliative care, Symptom burden, Psychosocial distress

Introduction

The worldwide disease burden of heart failure (HF), a “global pandemic” [1, 2], is enormous [3], and its prevalence, due to the growth and ageing of the population, is expected to further increase in the coming decades [4, 5]. Especially in elderly patients and advanced stages of HF, morbidity and disability are high [6, 7], as is the caregiver burden [8]. Comorbidities may further compromise quality of life (QoL), as every second HF patient suffers from more than 5 major comorbidities [9].

As the health-related QoL is of paramount importance for patients with advanced HF, many of whom would trade a longer life span for better quality [10, 11], and also affects prognosis [7], patient-reported outcomes (PRO) have gained attention as valuable instruments in guiding HF management [12]. HF specialists have been calling for a comprehensive, if required interdisciplinary care approach tailored to the individual’s needs [13].

These treatments and aid beyond evidence-based HF therapies have been referred to as “palliative care” (PC), as this approach is aimed at improving QoL of patients and their families facing “problems of physical, psychosocial or spiritual nature” [13, 14]. Instead of being tantamount to end-of-life care, a popular misconception, all patients with serious illnesses may benefit from PC also earlier than in the last year of life [15, 16]. The need for PC for chronic diseases may even be greater than for patients suffering from malignancies [15]. Many major cardiovascular society guidelines give recommendations for interdisciplinary PC in advanced HF [17–20]. Primary PC should be applied by treating HF specialists or cardiologists and includes, e.g., pain control, psychosocial care, advanced care planning, identification of goals of care or support for complex treatment and decision-making [21]. PC specialists should be involved in particularly severe or complex situations [21].

The evidence for PC in HF is still in its infancy and is largely drawn from observational studies carrying a risk for subjective and objective bias [21–23], although benefits of PC interventions in this context have recently been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials [24, 25]. As more data on symptom burden, psychosocial distress, and potential PC needs in advanced HF are required to improve this aspect of integrated HF care, we conducted this explorative pilot study using a cross-sectional approach.

Methods

Study cohort

The study population consisted of HF patients referred for further treatment evaluation (including implantation of left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) and heart transplantation) to our HF outpatient clinic (OC), and HF patients hospitalised for a worsening HF event at the HF unit (HFU), a specialised intermediate care ward at the University Heart and Vascular Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, a large tertiary care centre in Hamburg, Germany.

Enrollment started in September 2016 and ended in September 2019. All patients aged ≥ 18 years with sufficient cognitive function and adequate knowledge of the German language were considered eligible to participate. Patients on LVAD support and heart transplant recipients were not included. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. HF treatment was optimized according to current guideline recommendations. The local ethics committee of the General Medical Council of Hamburg, Germany, approved the study protocol (PV 5010).

Clinical assessment

Clinical variables including age, sex, type of cardiomyopathy, non-cardiac comorbidities (namely arterial hypertension, diabetes, obesity, chronic renal failure, peripheral artery disease, malignancies, pulmonary diseases, neurologic comorbidities, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, psychiatric/psychological comorbidities, nicotine abuse, and alcohol abuse) and cardiac history, as well as clinical findings on presentation such as the New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, were assessed. For a better understanding of HF severity and the stage in the clinical course, we used the Seattle Heart Failure Model [26] (SHFM), a multivariate risk model including clinical status, pharmacological therapy, and device characteristics as well as laboratory parameters, to estimate mean 1-, 2- and 5-year survival in each group.

Patient-reported outcome measures

Assessments were performed by trained study personnel. Owing to the explorative approach, there were no pre-specified timepoints for study assessments.

The MIDOS survey [27] (Minimal Documentation System For Palliative Care) served as a self-assessment tool for the symptom burden. The questionnaire, originating from PC, measures the intensity of ten frequent symptoms: Pain, nausea, emesis, dyspnea, constipation, weakness, loss of appetite, fatigue, sadness, and anxiety. Each symptom is rated on a four-point scale from “0 = no” up to “3 = severe”, resulting in sum scores from 0 to 30 points (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of the MIDOS questionnaire

| Symptom, n (%) | HFU (n = 137) | OC (n = 122) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | 0.012 | ||

| None | 71 (51.8) | 83 (69.2) | |

| Mild | 48 (35.0) | 21 (17.5) | |

| Moderate | 13 (9.5) | 13 (10.8) | |

| Severe | 5 (3.6) | 3 (2.5) | |

| Nausea | 0.441 | ||

| None | 109 (79.6) | 105 (86.8) | |

| Mild | 24 (17.5) | 13 (10.7) | |

| Moderate | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Severe | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Vomiting | 0.012* | ||

| None | 123 (89.8) | 118 (99.2) | |

| Mild | 10 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Moderate | 3 (2.2) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Severe | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Dyspnea | 0.001* | ||

| None | 41 (29.9) | 47 (38.8) | |

| Mild | 22 (16.1) | 35 (28.9) | |

| Moderate | 41 (29.9) | 31 (25.6) | |

| Severe | 33 (24.1) | 8 (6.6) | |

| Obstipation | 0.001* | ||

| None | 80 (58.8) | 106 (86.9) | |

| Mild | 39 (28.7) | 10 (8.2) | |

| Moderate | 11 (8.1) | 4 (3.3) | |

| Severe | 6 (4.4) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Weakness | 0.001* | ||

| None | 22 (16.1) | 43 (35.2) | |

| Mild | 43 (31.4) | 38 (31.1) | |

| Moderate | 43 (31.4) | 30 (24.6) | |

| Severe | 29 (21.2) | 11 (9.0) | |

| Lack of appetite | 94 (77.0) | <0.001* | |

| None | 58 (42.3) | 14 (11.5) | |

| Mild | 42 (30.7) | 11 (9.0) | |

| Moderate | 24 (17.5) | 3 (2.5) | |

| Severe | 13 (9.5) | ||

| Fatigue | 29 (21.2) | 32 (26.4) | 0.043 |

| None | 40 (29.2) | 46 (38.0) | |

| Mild | 36 (26.3) | 30 (24.8) | |

| Moderate | 32 (23.4) | 13 (10.7) | |

| Severe | |||

| Depression | 0.778 | ||

| None | 101 (73.7) | 82 (68.3) | |

| Mild | 21 (15.3) | 24 (20.0) | |

| Moderate | 12 (8.8) | 11 (9.2) | |

| Severe | 3 (2.2) | 3 (2.5) | |

| Anxiety | 0.689 | ||

| None | 86 (62.8) | 82 (67.8) | |

| Mild | 35 (25.5) | 24 (19.8) | |

| Moderate | 13 (9.5) | 11 (9.1) | |

| Severe | 3 (2.2) | 4 (3.3) |

HFU heart failure unit, OC outpatient clinic

The MIDOS shows good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.723) [27]. In our study, Cronbach’s α was 0.803.

We used two psychometric scales to evaluate the psychological burden: The Distress Thermometer [28] (DT) and the 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4) [29]. The DT is an 11-point visual analogue scale ranging from “0 = no distress” up to “10 = extreme distress”, self-assessing patients’ level of distress over the past week. A cut-off ≥ 5 indicates clinically significant levels requiring additional assessment and treatment [28, 30]. To identify potential sources of distress, a supplemental list of 37 problems had to be attributed with “yes” or “no”.

The PHQ-4 was used to screen for both anxiety and depressive disorders. Of its 4 items, 2 assess core depressive symptoms and two anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Items are scored on a four-point Likert scale from ‘0 = not at all’ to ‘3 = nearly every day’, thus PHQ-4 scores range from 0 to 12 [29]. Scores of 0 to 2 can be interpreted as ‘normal’, 3 to 5 as ‘mild’, 6 to 8 as ‘moderate’ (‘yellow flags’) and ≥ 9 as ‘severe’ symptoms of anxiety and depression (‘red flags’) [31]. With Cronbach’s α of 0.85, internal consistency of the PHQ-4 was high [29]. In our study, Cronbach’s α was 0.866.

Screening for PC needs

Patients consecutively underwent a physician-directed screening for PC needs. The “Palliative Care Screening Tool for HF Patients” [32] (PCST), a modified version of the “Five-Item Palliative Care Screening Tool” [33], is a 9-item questionnaire for treating cardiologists/HF specialists querying objective indicators of additional multi-disciplinary palliative support in addition to standard HF management, which also includes the caregiver’s perspective (Table 2). PC needs are indicated by scores ≥ 5 out of a maximum of 12 points [34], while this cut-off has yet to be validated for the modified version [32]. In a previous study with HF patients, the internal consistency of the PCST was reported by Cronbach’s α as 0.580 [32]. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was 0.601.

Table 2.

Results of the Palliative Care Screening Tool for HF Patients

| Screening item, n (%) | Points | HFU (n = 137) | OC (n = 122) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of chronic HF | 1 | 137 (100) | 122 (100) | |

| NYHA functional class | 1–4 | < 0.01* | ||

| I | 21 (15.3) | 16 (13.1) | ||

| II | 35 (25.5) | 42 (34.4) | ||

| III | 50 (36.5) | 55 (45.1) | ||

| IV | 31 (22.6) | 9 (7.4) | ||

| Serious complications of chronic heart failure (prognosis of < 12 months) | 1 | 80 (58.4) | 24 (19.7) | < 0.01* |

| Serious comorbidity associated with poor prognosis | 1 | 109 (79.6) | 52 (42.6) | < 0.01* |

| Uncontrolled symptoms despite cardiologic treatment | 1 | 59 (43.1) | 46 (37.7) | 0.380 |

| Moderate to severe distress in patient and/or family related to chronic heart failure diagnosis or therapy | 1 | 91 (66.4) | 13 (10.7) | < 0.01* |

| Patient and/or family concern about course of disease and decision making | 1 | 91 (66.4) | 23 (18.9) | < 0.01* |

| Patient and/or family request palliative care consultation | 1 | 7 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.011* |

| Cardiologic team needs assistance with complex decision making or determining goals of care | 1 | 7 (5.1) | 2 (1.6) | 0.128 |

| Screening sum score, M ± SD | 1–12 | 6.59 ± 2.2 | 4.81 ± 1.8 | < 0.01* |

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics including frequencies, means, and standard deviations were determined, as well as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for not normally distributed variables. Group differences were analyzed using T-tests and χ2-tests or Fisher’s exact tests, according to the metric of the dependent variable. All significance tests were two-tailed using a significance level of α < 0.05. Analyses and graphs were performed or created using SPSS statistics software version 24.0 (IBM, USA).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

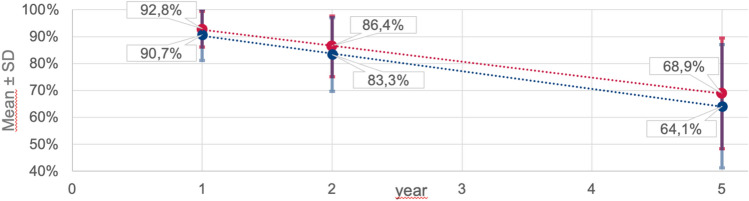

A total of 259 patients were studied, 137 (53%) as inpatients at the HF unit (HFU) and 122 (47%) as outpatients at the specialised outpatient clinic (OC). There was a predominance of men in both study groups (HFU 69%, OC 75%, p = 0.225). Hospitalised patients were older (mean age 67.0 ± 13.9 vs. 57.9 ± 13.8 years, p < 0.01) and less frequently suffered from ischaemic cardiomyopathy, while most of the cardiac and non-cardiac comorbidities were evenly distributed between the two study groups (Table 3). More than half of the patients exhibited NYHA class III or IV symptoms (HFU 59% vs. OC 53%). The mean projected survival was better in the outpatient group each at one (92.8 ± 6.6% vs. 90.7 ± 9.5%), two (86.4 ± 11.3% vs. 83.3 ± 13.7%), and five years (68.9 ± 20.6% vs. 64.1 ± 23.0%) (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics

| HFU (n = 137) | OC (n = 122) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical variables | |||

| Age, M ± SD (range) | 67.0 ± 13.9 (18–90) | 57.9 ± 13.8 (19–83) | < 0.01** |

| Male gender, n (%) | 94 (68.6) | 92 (75.4) | 0.225 |

| Aetiology of heart disease, n (%) | |||

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 52 (38.0) | 43 (35.2) | < 0.01** |

| Ischaemic cardiomyopathy | 11 (8.0) | 61 (50.0) | |

| Valvular cardiomyopathy | 40 (29.2) | 11 (9.0) | |

| Others/unknown | 34 (24.8) | 7 (5.7) | |

| History of comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 69 (50.4) | 61 (50.0) | 0.953 |

| Diabetes | 46 (33.6) | 28 (23.0) | 0.059 |

| Obesity | 20 (14.6) | 42 (34.4) | < 0.01** |

| Chronic renal failure | 52 (38.0) | 30 (24.6) | 0.021* |

| Peripheral artery disease | 46 (33.6) | 14 (11.5) | < 0.01** |

| Malignancy | 26 (19.0) | 16 (13.1) | 0.201 |

| Pulmonary disease | 33 (24.1) | 37 (30.3) | 0.259 |

| Neurologic comorbidity | 22 (16.1) | 24 (19.7) | 0.448 |

| Hypothyroidism | 13 (9.5) | 18 (14.8) | 0.193 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 8 (5.8) | 9 (7.4) | 0.618 |

| Psychiatric/psychological comorbidity | 13 (9.5) | 9 (7.4) | 0.543 |

| Nicotine abuse | 32 (23.4) | 43 (35.2) | 0.035* |

| Alcohol abuse | 7 (5.1) | 6 (4.9) | 0.944 |

| Cardiac history and presentation, n (%) | |||

| Pacemaker/intracardiac device | 23 (16.8) | 78 (63.9) | < 0.01** |

| Prior cardiac surgery | 35 (25.5) | 40 (32.8) | 0.200 |

| History of CPR | 6 (4.4) | 6 (4.9) | 0.837 |

| History of atrial fibrillation | 59 (43.1) | 46 (37.7) | 0.380 |

| Peripheral edema upon presentation | 50 (36.5) | 18 (14.8) | < 0.01** |

| NYHA I | 21 (15.3) | 16 (13.1) | < 0.01** |

| NYHA II | 35 (25.5) | 42 (34.4) | |

| NYHA III | 50 (36.5) | 55 (45.1) | |

| NYHA IV | 31 (22.6) | 9 (7.4) | |

| Eurotransplant waiting list status, n (%) | |||

| Listed “transplantable” (T-status) | 3 (2.2) | 9 (7.4) | 0.047* |

| Listed “high-urgency” (HU-status) | 4 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.057 |

HFU heart failure unit, OC outpatient clinic, M mean, SD standard deviation, NYHA New York heart association, CPR Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Fig. 1.

Projected survival in the Seattle Heart Failure Model. Abbreviations: HFU heart failure unit, OC outpatient clinic

Patient-reported outcome measures

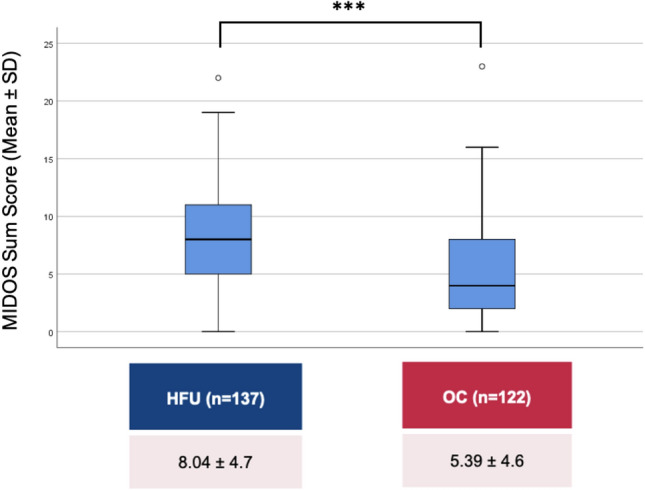

The MIDOS questionnaire revealed a more severe symptom burden among hospitalised patients, among whom mean MIDOS scores were 8.0 ± 4.7, compared to 5.4 ± 4.6 in HF outpatients (max. 30 points, p < 0.001, Table and Fig. 2). In both groups, dyspnea, fatigue and weakness were the 3 most frequent of at least “moderate” intensity, while dyspnea and fatigue were experienced more often by hospitalised patients.

Fig. 2.

Results of the MIDOS questionnaire. Abbreviations: HFU heart failure unit, OC outpatient clinic, MIDOS minimal documentation system for palliative care, M mean, SD standard deviation

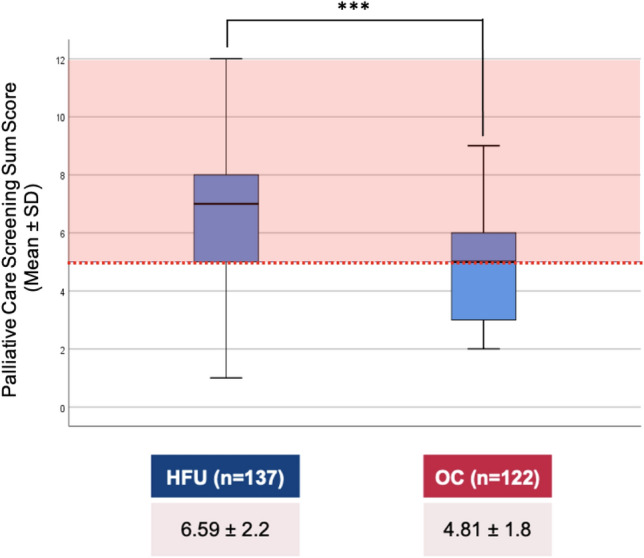

Mean Distress Thermometer (DT) scores were 6.0 ± 2.3 in inpatients vs. 4.8 ± 2.3 in outpatients (max. 10 points, p < 0.001, Fig. 3). 75.7% of HFU patients compared to 56.7% of OC patients (p = 0.001), experienced clinically relevant levels of distress (as indicated by DT scores ≥ 5). The three most frequently reported problems in both groups were fatigue, breathing, and sleeping problems. Emotional problems, family problems, and problems of practical nature, as well as spiritual concerns, were considered less relevant compared to physical complaints.

Fig. 3.

Results of the distress thermometer. Abbreviations: HFU heart failure unit, OC Outpatient clinic, M mean, SD standard deviation

The PHQ-4 screening did not show differences between in- and outpatients (mean PHQ-4 score 2.3 ± 2.5 in inpatients vs. 2.2 ± 2.5 in outpatients, p = 0.78). 40.9% of in- and 35.5% of outpatients reported mild symptoms of depression or anxiety (scores ≥ 3), and moderate or severe symptoms were detected in 13 HFU (9.5%) and 12 OC patients (9.8%, p = 0.275).

Screening for PC needs

The physician-directed screening for PC needs showed a higher mean score in the group of hospitalised patients (PCST mean score 6.6 ± 2.1 vs. 4.8 ± 1.8, p < 0.01, Table 2; Fig. 4). Assuming scores ≥ 5 to indicate a need for palliative support, four out of five inpatients (82.5%) and more than half of outpatients (52.5%) studied would require additional attention in this regard. Irrespective of this, the screening revealed that only seven hospitalised patients (5.1%) – and not a single patient in the outpatient group – had actively requested a PC consultation, and the cardiologic team rarely (in 3.4% of all patients) saw itself in need of specialist assistance, e.g., with complex decision making or determining the goals of care.

Fig. 4.

Results of the palliative care screening tool for HF patients. Abbreviations: HFU heart failure unit, OC outpatient clinic, M mean, SD standard deviation

Discussion

In a cohort of HF patients at a specialized service, a high symptom burden and level of psychosocial distress were detected using a novel cross-sectional approach. Many HF patients fulfil the criteria for “specialised PC”, which—given the relatively good life expectancy of these patients—may indicate a need for tailored comprehensive or holistic care, rather than PC in its traditional sense.

Design and broad inclusion criteria of this pilot study led to the creation of a heterogeneous sample of HF patients with a comparably young age and good survival prognosis. Compared to the PAL-HF population [24], patients in the study were younger, had fewer comorbidities and a lower NYHA functional class. This may represent the actual clinical situation in a specialized HF service better than a highly selected sample of the “sickest of the sick” patients with terminal HF or in “end-of-life situations”, who have traditionally been the target population for assessing PC needs. One may argue that “PC needs” in this “well-off” HF population rather represent “general needs for holistic care”, even though the PCST was adapted from an instrument used to screen for PC needs in advanced cancer patients [33] and the other patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) of this study are routinely used in PC assessments in Germany as well [35, 36]. It may be challenging to distinguish differential indications for PC from other person-centered modalities of care (e.g., psycho-cardiological treatment, psychosocial treatment, or collaborative care), especially given the relatively long projected survival in our cohort and the possible effects on cardiac outcomes of such interventions [37].

Comparing results of the current study with previously published studies from our tertiary care centre may help put the findings into perspective. PROMs employed in this study were previously applied in advanced HF patients on LVAD support and heart transplant recipients [38] and, naturally, terminal cancer inpatients [39]. While heart transplant recipients have the lowest MIDOS score [38], which can be expected and attributed to the nature of the received treatment, the MIDOS score of terminal cancer patients exceeds those of HF patients [39], even of those hospitalized. However, before prematurely concluding that the symptom burden in terminal cancer may ultimately be higher than in advanced HF, it should be taken into consideration that the MIDOS questionnaire may not ideally portray HF symptomatology. According to previous studies on HF-specific PROMs, HF patients mostly exhibit three “hallmark symptoms”—dyspnea, fatigue, and weakness [40, 41]—which was also observed in the presented study. In contrast, cancer patients, as the “original” target population of the MIDOS questionnaire, usually suffer from a larger variety of symptoms, thus resulting in higher MIDOS scores. Especially gastrointestinal symptoms, which play a subordinate role in HF, seem to be over-represented in the MIDOS, which may consequently be a less favourable instrument for assessing symptom burden in HF than widely established and evidence-based disease-specific PROMs as the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) or the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ).

The psychosocial burden and psychological co-morbidities in advanced HF may frequently be underestimated or even neglected [42, 43]. Many PRO instruments lack psychometric properties, and the KCCQ and MLHFQ have limited focus on emotional and relationship problems [12]. Comparing levels of distress, hospitalized HF patients in the study had DT scores almost equivalent to those of patients with terminal cancer [39]. Besides, independent of this treatment setting, a high prevalence of clinically relevant distress in HF was detected, and correspondingly a high number of patients exhibited mild symptoms of depression and anxiety. Depression and anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric comorbidities in HF with a prevalence of up to 30% [44], and have been shown to inversely affect prognosis [44, 45]. In the study, the prevalence of “yellow” and “red flags” in the PHQ-4 screening (moderate or severe symptoms) was much lower, so depression and anxiety may predominantly be limited to a “sub-syndromal” level.

The PCST showed that many HF patients fulfil criteria for “specialised PC”. Across different HF cohorts, LVAD patients, together with hospitalized HF patients, may have the greatest need for additional supportive treatment [38]. While benefits of PC interventions in HF have recently been demonstrated, evidence that patients judged as “being in need of PC” by the PCST profit from such care is so far lacking. First, the patient’s and caregiver’s perspective on such treatment should be obtained, and a specialist consultation to ascertain the indication for PC be arranged.

Apart from the MIDOS, the tools used in this study’s cross-sectional approach could be a valuable addition to the assessment of PROMs in HF. They moreover proved easy and self-explanatory in use, allowing for assessments to be smoothly integrated into clinical routine in the setting of specialist HF care, which is in line with previous studies [32, 38].

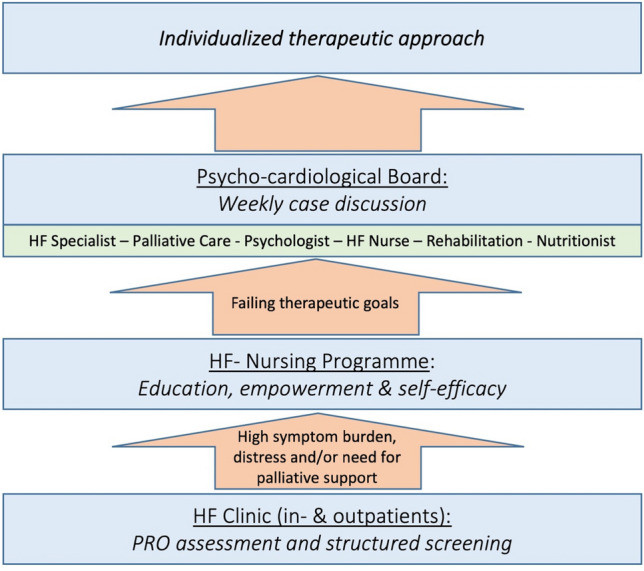

As a consequence of this study’s observations, a multi-disciplinary stepwise approach to improve holistic HF care was implemented at our institution, which is based on the structured application of the PCST, DT, and a set of validated PROMs recommended by the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) in HF patients: The KCCQ-12, PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System), and PHQ-2 [46]. Patients with a high symptom burden, high level of distress or suspected needs for PC are taken up into a nurse-led HF education and counseling programme, focusing on strengthening patient resources, knowledge building, and self-efficacy. If ongoing distress is observed and treatment goals are not met, patients’ cases are discussed in an interdisciplinary psycho-cardiological board deciding on an individualized therapeutic approach. Also, a direct, low-barrier PC specialist consultation for patients with a positive screening for PC needs can be initiated (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Proposal of a stepwise approach to holistic HF care

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. While this analysis used patients prospectively enrolled at a large tertiary HF centre, the single-centre nature of the data and the small sample size are limitations that hamper generalizability of the presented findings. There are moreover methodological limitations owing to the explorative, pilot character of this observational study and the used assessment instruments.

The study design can only insufficiently capture the characteristic symptom trajectory of HF. Especially patients’ long-term needs may be inadequately examined, as symptom burden, psychosocial distress, and PC needs usually improve after discharge. Instead, longitudinal data from a “staged” design with assessments during both hospitalization and after discharge could be a preferable approach.

Concerning the PROMs used in the study, the MIDOS questionnaire may not be suitable to properly portray the symptom burden in HF, and thus be inferior to other well-established HF-specific PROMs in this respect. Further limitations concern the internal consistency of the PCST. Cronbach’s α was 0.601, a value lower than considered to be adequate (α ≥ 0.70). This could be due to the low number of items, poor item inter-relatedness or heterogenous constructs, and warrants further research to assess the dimensionality and underlying structure of the PCST. As the study’s PROMs are not well established in HF, assessment of a disease-specific QoL questionnaire as a comparator would have been of added value.

Finally, conclusions established from pooled data from in- and outpatients should be regarded as hypothesis-generating and call for independent validation to mitigate these limitations. A randomized-controlled follow-up trial investigating the benefit of structural screening for PC needs using well-chosen PROMs and tailored multi-professional PC interventions could validate this study’s finding and further underline the paramount importance of holistic care in HF.

Conclusion

Patients with advanced HF, even though with relatively good prognosis, have multiple needs that are often not detected and addressed before “truly palliative” treatment situations are reached. Next to improving prognosis, patients’ well-being should be accepted as a primary goal of care, as many patients prefer a better QoL to prolongation of life [10, 11].

The tools in this study seem useful to explore unmet needs, and the screening results may help to improve integrated HF care through a nurse-led HF education and counseling programme. Longitudinal studies in larger well-defined cohorts are required to investigate whether these effects can really be achieved using such interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients, study personnel and physicians involved.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

References

- 1.Ponikowski P, Anker SD, AlHabib KF, et al. Heart failure: preventing disease and death worldwide. ESC Heart Fail. 2014;1(1):4–25. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savarese G, Lund LH. Global public health burden of heart failure. Card Fail Rev. 2017;3(1):7–11. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2016:25:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States. Circul Heart Failure. 2013;6(3):606–619. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2018 doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazzarini V, Mentz RJ, Fiuzat M, Metra M, O'Connor CM. Heart failure in elderly patients: distinctive features and unresolved issues. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(7):717–723. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansson I, Joseph P, Balasubramanian K, et al. Health-related quality of life and mortality in heart failure: The global congestive heart failure study of 23 000 patients from 40 countries. Circulation. 2021;143(22):2129–2142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durante A, Greco A, Annoni AM, Steca P, Alvaro R, Vellone E. Determinants of caregiver burden in heart failure: does caregiver contribution to heart failure patient self-care increase caregiver burden? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;18(8):691–699. doi: 10.1177/1474515119863173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conrad N, Judge A, Tran J, et al. Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence: a population-based study of 4 million individuals. Lancet. 2018;391(10120):572–580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis EF, Johnson PA, Johnson W, Collins C, Griffin L, Stevenson LW. Preferences for quality of life or survival expressed by patients with heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20(9):1016–1024. doi: 10.1016/S1053-2498(01)00298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiuzat M, Lowy N, Stockbridge N, et al. Endpoints in Heart Failure Drug Development: History and future. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(6):429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelkar AA, Spertus J, Pang P, et al. Utility of patient-reported outcome instruments in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4(3):165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodlin SJ. Palliative care in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(5):386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization definition of palliative care . World Health Organization. Geneva: Switzerland; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connor S, Bermedo M. Global atlas of palliative care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrell BR, Twaddle ML, Melnick A, Meier DE. National consensus project clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care guidelines, 4th Edition. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(12):1684–1689. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(36):3599–3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman D, Pamboukian SV, Teuteberg JJ, et al. The 2013 international society for heart and lung transplantation guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(2):157–187. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollenberg SM, Stevenson LW, Ahmad T, et al. 2019 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on risk assessment, management, and clinical trajectory of patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(15):1966–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ezekowitz JA, O'Meara E, McDonald MA, et al. 2017 Comprehensive update of the canadian cardiovascular society guidelines for the management of heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(11):1342–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kavalieratos D, Gelfman LP, Tycon LE, et al. Palliative care in heart failure: rationale, evidence, and future priorities. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(15):1919–1930. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2104–2114. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiskar K, Toma M, Rush B. Palliative care in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28(7):445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, et al. Palliative care in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(3):331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sidebottom AC, Jorgenson A, Richards H, Kirven J, Sillah A. Inpatient palliative care for patients with acute heart failure: outcomes from a randomized trial. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(2):134–142. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, et al. The seattle heart failure model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113(11):1424–1433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stiel S, Matthes ME, Bertram L, Ostgathe C, Elsner F, Radbruch L. Validierung der neuen Fassung des Minimalen Dokumentationssystems (MIDOS2) für Patienten in der Palliativmedizin. Der Schmerz. 2010;24(6):596–604. doi: 10.1007/s00482-010-0972-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehnert A, Müller D, Lehmann C, Koch U. Die deutsche version des NCCN distress-thermometers. Z Psychiatr Psychol Psychother. 2006;54(3):213–223. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, Peabody E, Scher HI, Holland JC. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer. 1998;82(10):1904–1908. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowe B, Wahl I, Rose M, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1–2):86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oechsle K, Ehlert J, Kodolitsch YV, Ullrich A, Bokemeyer C, Rybczynski M (2017) Self-assessment and screening for palliative care need in patients with chronic heart failure. J Palliat Care Med 7

- 33.Glare PA, Semple D, Stabler SM, Saltz LB. Palliative care in the outpatient oncology setting: evaluation of a practical set of referral criteria. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(6):366–370. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glare PA, Chow K. Validation of a simple screening tool for identifying unmet palliative care needs in patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(1):e81–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roch C, Heckel M, van Oorschot B, Alt-Epping B, Tewes M (2021) Screening for palliative care needs: pilot data from german comprehensive cancer centers. JCO Oncol Pract [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Graham-Wisener L, Dempster M, Sadler A, McCann L, McCorry NK. Validation of the distress thermometer in patients with advanced cancer receiving specialist palliative care in a hospice setting. Palliat Med. 2021;35(1):120–129. doi: 10.1177/0269216320954339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albus C, Waller C, Fritzsche K, et al. Significance of psychosocial factors in cardiology: update 2018. Clin Res Cardiol. 2019;108(11):1175–1196. doi: 10.1007/s00392-019-01488-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strangl F, Ullrich A, Oechsle K, et al. Assessing palliative care need in left ventricular assist device patients and heart transplant recipients. Interact Cardio Vascular Thoracic Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivaa211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coym A, Ullrich A, Hackspiel LK, Ahrenholz M, Bokemeyer C, Oechsle K. Systematic symptom and problem assessment at admission to the palliative care ward – perspectives and prognostic impacts. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00576-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell RT, Petrie MC, Jackson CE, et al. Which patients with heart failure should receive specialist palliative care? Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(9):1338–1347. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koshy AO, Gallivan ER, McGinlay M, et al. Prioritizing symptom management in the treatment of chronic heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7(5):2193–2207. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McHorney CA, Mansukhani SG, Anatchkova M, et al. The impact of heart failure on patients and caregivers: A qualitative study. Plos One. 2021;16(3):e0248240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Testa M, Cappuccio A, Latella M, et al. The emotional and social burden of heart failure: integrating physicians’, patients’, and caregivers’ perspectives through narrative medicine. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20(1):522. doi: 10.1186/s12872-020-01809-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(8):1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Celano CM, Villegas AC, Albanese AM, Gaggin HK, Huffman JC. Depression and anxiety in heart failure: a review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2018;26(4):175–184. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burns DJP, Arora J, Okunade O, et al. International consortium for health outcomes measurement (ICHOM): standardized patient-centered outcomes measurement set for heart failure patients. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(3):212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]