Abstract

The sfaI determinant encoding the S-fimbrial adhesin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains was found to be located on a pathogenicity island of uropathogenic E. coli strain 536. This pathogenicity island, designated PAI III536, is located at 5.6 min of the E. coli chromosome and covers a region of at least 37 kb between the tRNA locus thrW and yagU. As far as it has been determined, PAI III536 also contains genes which code for components of a putative enterochelin siderophore system of E. coli and Salmonella spp. as well as for colicin V immunity. Several intact or nonfunctional mobility genes of bacteriophages and insertion sequence elements such as transposases and integrases are present on PAI III536. The presence of known PAI III536 sequences has been investigated in several wild-type E. coli isolates. The results demonstrate that the determinants of the members of the S-family of fimbrial adhesins may be located on a common pathogenicity island which, in E. coli strain 536, replaces a 40-kb DNA region which represents an E. coli K-12-specific genomic island.

Extraintestinal Escherichia coli strains can be grouped into three different pathotypes: meningitis E. coli (MENEC) strains, which cause newborn meningitis; septicemia E. coli (SEPEC) strains, which cause septicemia infections; and uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) strains, which are the most frequently isolated causative agents of infections of the bladder and the kidney in humans (45, 57). They are characterized by the expression of certain virulence factors, including adhesins, which contribute to the establishment of the infection and distinguish them from nonpathogenic E. coli strains (39). Members of the S-fimbrial family of adhesins are frequently expressed in extraintestinal E. coli strains isolated from men. This adhesion family consists of S-fimbriae (Sfa), with its subtypes SfaI and SfaII; F1C-fimbriae (Foc); and S/F1C-related fimbriae (Sfr) (25, 46). The AC/I-fimbriae (Fac) which are expressed by avian-pathogenic E. coli strains also belong to the S-family of adhesins (5, 6). All members are highly similar in the organization of their determinants and the sequence identities of the encoded proteins (45–47, 54). However, they differ in their receptor and therefore in their tissue specificity. S-fimbrial adhesins recognize α-sialyl-2-3-β-lactose-containing receptors and are predominantly expressed by strains which cause sepsis and meningitis but also by urinary tract infection (UTI) isolates (32, 33), whereas F1C-fimbrial adhesins bind to β-GalNac-1,4-β-Gal-containing structures (30) and are preferentially expressed by UTI isolates.

The uropathogenic E. coli strain 536 (O6:K15:H31) has previously been shown to produce various types of fimbrial adhesins, including type 1, P-related, and S-fimbriae (26). The presence of four pathogenicity islands (PAIs I536 to IV536) has been described for E. coli strain 536 so far. All four PAIs have common characteristics which are typical of pathogenicity islands, i.e., association with a tRNA gene and the presence of often nonfunctional mobility genes (24). Earlier findings implied that the sfaI determinant is part of a pathogenicity island of strain 536 designated PAI III536 (23). Whereas the genetic organization of PAI I536, PAI II536, and PAI IV536 has already been published, little information is currently available about the structure of PAI III536. Therefore, one aim of this study was the structural characterization of pathogenicity island III536. In order to improve our knowledge of the evolution and distribution of the members of the S-family of adhesins as a part of pathogenicity islands in E. coli, the chromosomal localization as well as the sequence context of operons coding for members of this adhesin family were investigated in different E. coli strains and compared with that of the PAI III536-located sfaI determinant of UPEC strain 536.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

A collection of 84 wild-type E. coli isolates and 28 strains of the E. coli Collection of Reference (ECOR) strain collection were used in this study. E. coli strains 536, 2980, 764, J96, E-B35, E351, E642, AD110, BK658, W1825, 4405/1, 7521/94-1, F18, 86-24, E2348/69, EDL933, and the ECOR strains have been described elsewhere (11, 13, 16, 17, 19, 27, 34, 36, 42, 43, 48, 49). Eighteen UPEC strains have been chosen from a collection of uropathogenic isolates described before (64, 65). The MENEC strains IHE3034, IHE3036, IHE3080, RS176, RS218, and RS226 were described earlier (1, 32, 41). The SEPEC and MENEC isolates B616, B10363, B13155, Ve239, and Ve1140 were kindly provided by H. Schroten (Universitätsklinikum Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). In addition, we used SEPEC isolates 269/93, 1939/93, 2656/93, 4549/93, 10413/93, and 10209. The enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) strain DPA065, the UPEC strain CFT073, and the necrotoxic E. coli (NTEC) strain S5 were provided by A. Giammanco (Dipartimento di Igiene e Microbiologica, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy), by H. Mobley (University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Md.), and by E. Oswald (Ecole Nationale Veterinaire de Toulouse, Toulouse, France), respectively. The enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) strains 179/2, 156A, and 37-4, the enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) strains SF493/89, 3574/92, 2907/97, 5720/96, 3697/97, and ED142, the enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) strain 76-5, and the EAEC 5477/94, as well as the enterotoxigenic (ETEC) strain C9221a (O6:K15:H16) and the reference strain (O149:K88), have been described before (40). The following strains were isolated during a long-term study of women with chronic UTIs: 13A1, 19A1, 16A2U, 20A1, 20A1U, 22A2, 22B2U, 3D5, 2E1U, 2E2U, 1G1, 1G1U, 1H1, and 1H1U. The E. coli K-12 strains MG1655, K-12, W3110, P678-54, 5K, C600, and XL-1 Blue have been described before (7, 15). All strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (53).

DNA techniques.

Isolation of plasmid DNA and recombinant DNA was performed as previously published (53).

PCR.

A description of the primers used in this study is available as supplementary material (http://www.uni-wuerzburg.de/infektionsbiologie). The differentiation between subtypes of the S-fimbrial family of adhesins was performed by PCR using primers which are specific for the individual major fimbrial subunits. The sfaI-specific PCR product (161 bp) was obtained with the primers sfaAI.1 (5′-CGGGCATGCATCAATTATCTTTG-3′) and sfaAI.2 (5′-TGTGTAGATGCAGTCACTCCG-3′) using chromosomal DNA from E. coli 536 as a positive control. Detection of the sfaII determinant using primer pair sfaAII.1 (5′-ACGAAAAAGTTAGCTAATCTTGAT-3′) and sfaAII.2 (5′-TATACTGCGCTTTGATCCGAATT-3′) and chromosomal DNA of E. coli strain IHE3034 as a positive control resulted in a 251-bp PCR product. PCR with the primer pair focA.1 (5′-ATGGAGGAAACCCAAACGCCA-3′) and focA.2 (5′-GCTCACTGTAACCAACTTTTGTTG-3′) and chromosomal DNA of E. coli strain 2980 as a reference strain should result in a 274-bp PCR product. The sfr determinant can be detected using primer pair sfrA.1 (5′-CTAAAAGCCGACGGGGATAAAAGTGCTGCT-3′) and sfrA.2 (5′-ATAGCTAGCTGTTGGAGTATTTCCGTCGAAC-3′) and chromosomal DNA of strain BK658 as a control. The corresponding PCR product should be 241 bp long. DNA primers were purchased from MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany). The Taq DNA polymerase used for the detection of genes in different E. coli strains was purchased from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany).

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

The sequence determination of the cosmid clones pANN1E6 and parts of pCos3grl3, which contain parts of PAI III536 of E. coli strain 536, was performed as follows. One small insert library (2 to 2.5 kb) was generated by mechanical shearing of the cosmid DNA (44). After end repair with T4 polymerase, the fragments were ligated into the prepared pTZ19R vector. Isolated plasmids were sequenced from both ends using dye terminator chemistry and analyzed on ABI377 machines (Applied Biosystems, Munich, Germany). In the case of pANN1E6, after the assembly of 495 sequences, the remaining gaps were closed by primer walking on the plasmid clones. The Phrap software implemented in the Staden software package was used for assembly and editing of the sequence data (56). The sequence of the PAI III536 fragment present on the cosmid 1E6 was submitted to the NCBI database.

Homology searches were performed with the BLASTN and BLASTX programs of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (3).

Southern hybridization.

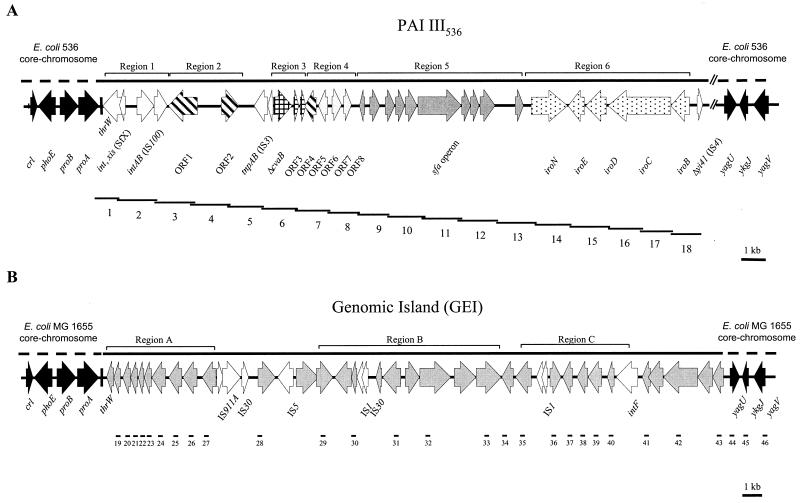

PCR results during the analysis of the chromosomal region downstream of thrW in different E. coli isolates were confirmed by Southern hybridization of EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNA of the investigated E. coli strains. After agarose gel electrophoresis, the EcoRI-digested E. coli genomic DNA was transferred to Biodyne B nylon membranes (PALL, Rossdorf, Germany). The PCR products of PCRs 19 to 46 (see also Fig. 1B) performed with chromosomal DNA of E. coli strain MG1655 as the template were used as probes for hybridization. Hybridization and detection were carried out using the ECL labeling and signal detection system (Amersham/Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of genetic organization of chromosomal downstream region of the tRNA gene thrW in E. coli strains 536 (A) and MG1655 (B): identification of different types of genomic islands. The structure of PAI III536 of E. coli strain 536 and that of the genomic island (GEI) of E. coli K-12 strain MG1655 is shown in its chromosomal sequence context. Numbered lines indicate regions of PAI III536 and of the GEI which have been detected by PCR. Solid arrows indicate ORFs representing the core chromosome, and open arrows indicate ORFs of mobile genetic elements. ORFs within regions without homology on the nucleotide level are indicated by hatched arrows.

RESULTS

Sequence analysis of left part of PAI III536.

The cosmid clone pANN1E6 was shown to contain the entire S-fimbrial determinant (sfaI) together with the flanking regions of UPEC strain 536. The sequence determination of the 38-kb DNA insert revealed that about 33 kb of this DNA fragment represented a part of a pathogenicity island which was designated PAI III536 previously (24). The right end of the cosmid insert of pANN1E6 and the left end of that of pCos3grl3 contain an overlapping region of about 4 kb covering a part of the iro determinant. The assembly of the sequences inserted into pANN1E6 and of the available sequences of pCos3grl3 resulted in a 37-kb DNA sequence which covers the left-hand part of PAI III536 (accession no. AF302690). It is estimated that the complete PAI III536 is about 70 kb in size. As can be seen from the sequence analysis, PAI III536 exhibits several features which are typical of pathogenicity islands. In addition to the sfaI determinant encoding the S-fimbrial adhesin, this fragment comprises the tRNA gene thrW, which serves as the chromosomal integration site of PAI III536, several genes of mobile genetic elements such as bacteriophage genes and insertion sequence (IS) elements, as well as unknown open reading frames (Fig. 1A, Table 1). One typical characteristic of pathogenicity islands is the presence of a bacteriophage integrase gene downstream of the tRNA gene which serves as the chromosomal integration site of the PAI.

TABLE 1.

ORFs and mobile genetic elements within PAI III536

| ORF, IS, or bacteriophage | Positiona | Similar sequencesb | % Nucleotide (protein) identity |

|---|---|---|---|

| int, xis (SfX) | 94–1478 | Integrase and excisionase of the O-antigen-converting bacteriophage X (S. flexneri) (BXU82084) | 98 (99) |

| IS100 | 2134–4011 | IS100 (Y. pestis plasmids pCD1 and pMT1) (AF074612) | 99 |

| ORF 1 | 4062–5813 | Hypothetical protein (T. maritima) (AE001775) | (23) |

| Hypothetical pifA gene product (E. coli) (X04968) | (36) | ||

| ORF 2 | 7334–8368 | DAHP-synthase (E. herbicola) (U93355) | (48) |

| IS3 | 9245–10458 | IS3 (SHI-2, S. flexneri) (AF141323) | 99 |

| ΔcvaB | 10491–11546 | E. coli mchE gene for the microcin H47 exporter component protein (AJ278866) | 97 |

| Colicin V secretion ATP-binding protein (pColV) (X57524) | (87–95) | ||

| ORF 3 | 11653–11874 | Microcin V immunity protein (P22521) | (23) |

| ORF 4 | 11871–12149 | Colicin V precursor (P22522) | (40) |

| ORF 5 | 12326–13012 | Hypothetical protein (S. marcescens) (AF027768) | (39) |

| YprB (E. coli) (P33774) | (40) | ||

| ORF 6 | 13107–13577 | ORF Z1633 of E. coli O157:H7 (AE005311) | 97 |

| ORF 7 | 14023–14535 | ORF Z1634 of E. coli O157:H7 (AE005311) | 86 |

| ORF 8 | 14987–15346 | Nucleotides 1–160 of ORF Z1635 of E. coli O157:H7 (AE005311) | 83 |

| sfaC | 15621–15842 | E. coli 536 sfaC gene of the S-fimbrial adhesin determinant sfa (AF301153) | 100 (56) |

| sfaB | 16261–16590 | E. coli 536 sfaB gene of the S-fimbrial adhesin determinant sfa (AF301153) | 100 |

| sfaA | 16964–17509 | E. coli 536 sfaA gene of the S-fimbrial adhesin determinant sfa (AF301153) | 100 |

| E. coli 536 SfaA fimbrial subunit precursor (P12730) | (99) | ||

| sfaD | 17580–18119 | E. coli 536 sfaD gene of the S-fimbrial adhesin determinant sfa (AF301153) | 100 |

| sfaE | 18160–18855 | E. coli 536 sfaE gene of the S-fimbrial adhesin determinant sfa (AF301153), | 100 |

| E. coli 536 sfa E fimbrial subunit (1713397D) | (99) | ||

| sfaF | 18926–21530 | E. coli 536 sfaF gene of the S-fimbrial adhesin determinant sfa (AF301153), | 100 |

| E. coli 536 Sfa F fimbrial subunit (1713397E) | (99) | ||

| sfaG | 21569–22096 | E. coli 536 sfaG gene of the S-fimbrial adhesin determinant sfa (AF301153), | 100 |

| E. coli 536 sfa G fimbrial subunit precursor (P13429) | (100) | ||

| sfaS | 22118–22609 | E. coli 536 sfaS gene of the S-fimbrial adhesin determinant sfa (AF301153) | 100 |

| sfaH | 22671–23570 | E. coli 536 sfaH gene of the S-fimbrial adhesin determinant sfa (AF301153) | 100 |

| E. coli 536 SfaH fimbrial subunit precursor(P13431) | (99) | ||

| sfaX (17 kDa) | 24811–25310 | E. coli prsX gene (X62158) | 96 |

| E. coli PrsX protein (P42192) | (98) | ||

| iroN | 25804–27981 | E. coli siderophore receptor IroN (AF135597) | 99 (99) |

| iroE | 28026–28982 | S. enterica IroE (U97227) | 73–76 |

| iroD | 29067–30296 | S. enterica ferric enterochelin esterase homolog IroD (U97227) | 72 (64) |

| iroC | 30400–34185 | Serovar Typhi ABC transport protein homolog IroC (T30293) | 73–79 (68) |

| iroB | 34199–35314 | Serovar Typhi glucosyltransferase (T30292) | 78 (80) |

| Δyi4I(IS4) | 36162–36521 | Plasmid pMM237, tnpA/IS4 right junction (MM7TN3IS4A) | 99 |

| Insertion element IS4 hypothetical 50.4-kDa protein, amino acids 316–442 (P03835) | (99) |

The location is given as nucleotide positions, numbering from the first nucleotide downstream of the tRNA gene thrW.

Homology based on BLASTN and BLASTX database searches.

In PAI III536, the tRNA gene thrW is followed by an integrase and excisionase gene of the O-antigen-modifying bacteriophage X of Shigella flexneri. PAI III536 contains a 5-kb DNA region without sequence homology to known DNA sequences which is flanked by an IS100 element frequently found on Yersinia pestis plasmids and a nonfunctional IS3 element found on the SHI-2 pathogenicity island of S. flexneri. Five suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) fragments (TspE4.K8, SauE15.C6, TspE4.B12, SauE15.G6, and SauE15.D4) obtained from a newborn meningitis (NBM)-causing E. coli isolate described by Bingen and coworkers (14) are homologous to this IS100-specific region. Two putative open reading frames, designated ORF 1 and ORF 2, can be determined in this region, which may represent so far unknown genes encoding a protein with homology to a hypothetical protein of Thermotoga maritima or a putative pifA gene product of E. coli and to a protein with homology to the 3-deoxy-d-arabinoheptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase (DAHP-synthase) of Erwinia herbicola, respectively. The fact that ORF 2 is preceded by a 150-bp DNA region that codes for a fragment similar to the transposase of the Erwinia amylovora-associated transposon Tn5393 implies that ORF 2 is a part of a former mobile genetic element. The IS3 element is followed by a 1.6-kb region which contains a fragment of the mhcE gene of E. coli strain H47, which encodes a component of the microcin H47 ABC transporter (4). About 1 kb of this DNA sequence is also homologous to an open reading frame which represents a truncated copy of the cvaB gene of plasmid pColV-K30, encoding a colicin V secretion protein. Another DNA region without any nucleotide sequence homology covers roughly 1.4 kb downstream of the cvaB fragment. This region seems to be linked with the cvaB gene, as it contains two small putative ORFs which code for peptides with homology to a microcin V immunity protein and the colicin V precursor, respectively. The gene product of another putative open reading frame (ORF 5) without any homology to known DNA sequences in this region exhibits similarity to a hypothetical protein of Serratia marcescens. This ORF is followed by a 2-kb DNA stretch containing ORFs 6 and 7. This part of PAI III536 is homologous to sequences found in the enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7 strain EDL933 in which the putative open reading frames Z1633 and Z1634 are located (50). Due to an internal stop codon, the putative gene product of Z1634 is 21 amino acids shorter in E. coli 536 than in strain EDL933. The 5′ part of the next ORF (ORF 8) is identical to that of E. coli O157:H7 ORF Z1635, but the promoter-distal region shows no homology to known nucleotide sequences. The SSH fragment TspE4.H10 isolated from an NBM E. coli isolate (14) represents a DNA stretch homologous to a part of sfaC.

The sfaI determinant coding for the S-fimbrial adhesin is followed by a 9.3-kb DNA region which represents the E. coli homologue of the iroBCDEN operon of Salmonella spp. The iroN gene encoding a catecholate siderophore receptor is followed by four putative ORFs with high homology to the iroED of Salmonella enterica and iroBC of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi The function of the irroE gene product is yet unknown. The gene products of iroD and iroC are homologues of a ferric enterochelin esterase of S. enterica and an ABC transport protein of serovar Typhi, respectively. The iroB-encoded protein is highly homologous to glucosyltransferases. The iroNE genes and an iroD fragment have recently been identified in another uropathogenic E. coli strain, CP9 (O4:K54:H5), closely linked to DNA sequences with homology to determinants of members of the S-adhesin family (52). One SSH fragment (TspE4.A8) obtained from an NMB-causing E. coli strain (14) is homologous to a region within iroN. The iro determinant is followed by an ORF which represents the second half of a gene encoding a hypothetical protein of 50.4 kDa in IS4.

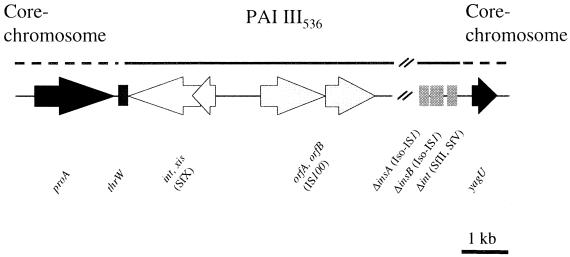

Identification of right junction site of PAI III536.

The right junction site of PAI III536 was determined by inverse PCR after ligation of EcoRV fragments of chromosomal DNA of E. coli strain 536, which contain the upstream region of yagU encoding a hypothetical protein. The sequence determination of the obtained DNA fragment (Fig. 2) revealed that 109 bp upstream of yagU, the E. coli MG1655-specific sequence representing the E. coli core chromosome is interrupted by sequences with homology to fragments of integrase genes of the S. flexneri bacteriophages SfII (AF021347) and SfV (SFU82619) as well as of the E. coli bacteriophage P22 (AF217253). This region is followed by DNA sequences with homology to fragments of the insB and insA genes of the Iso-IS1 element present in Shigella dysenteriae (AF153317) and the EPEC plasmid pB171 (AB024946). These results demonstrate that PAI III536 is flanked by sequences derived from Shigella bacteriophages, which integrate into highly homologous attP sites next to the tRNA gene thrW.

FIG. 2.

Junction sites between the E. coli core chromosome and PAI III536 in E. coli strain 536. Solid arrows represent ORFs located on the core chromosome. PAI III536 is flanked by the tRNA gene thrW and by yagU, representing the adjacent genes of the core chromosome. Both ends of PAI III536 show homology to sequences of Shigella O-antigen-modifying bacteriophages which integrate into the tRNA gene thrW. Solid arrows indicate ORFs representing the core chromosome, and open arrows indicate ORFs of mobile genetic elements.

Identification of different members of S-family of adhesins by PCR.

In order to be able to distinguish between the determinants that encode different subtypes of S-fimbriae (sfaI and sfaII), F1C-fimbriae (foc), and S-fimbria-related fimbriae (sfr), PCRs were established with primer pairs which are specific for sfaAI, sfaAII, focA, and sfrA. These primers can be used for specific amplification of the major subunit-encoding gene of the abovementioned members of the S-family of adhesins. E. coli strains 536, IHE3034, 2980, and BK658 were used as positive controls during the sfaAI-, sfaAII-, focA-, and sfrA-specific PCRs, respectively. According to the results of the PCRs, the strains used in this study were grouped as indicated in Table 2. Of the 66 E. coli strains expressing members of the S-family of adhesins (including strain 536), 13 strains were shown to be sfaI positive. In 12 E. coli strains, the sfaII determinant was detectable. E. coli strain AC/1 harbors the fac determinant, and 34 strains in this study contain the foc operon. With primers specific for conserved regions of the sfaI determinant, the presence of corresponding sequences was detectable in six E. coli strains. However, further identification using primer pairs specific for sfaAI, sfaAII, or focA was not possible. It has been reported that strain BK658 expresses an S-fimbria-related adhesin (Sfr) which is related but not identical to S- and F1C-fimbriae (49). In strains BK658 and 19A1, the sfrA-specific PCR was positive. The fimbrial determinants of the other four strains which could not be identified as sfaI, sfaII, foc, or sfr have been designated sfx, as they also seem to encode an unknown subtype of S-fimbrial adhesin. The corresponding strains do not agglutinate bovine erythrocytes but contain sequences homologous to sfa and foc which are detectable by Southern hybridization.

TABLE 2.

Presence of PAI III536-specific DNA regions in E. coli isolates expressing different types of S-fimbrial adhesina

| Adhesin type | No. of isolates | Region 1 (mobility) (PCRs 1 and 2) | Region 2 (unknown ORFs) (PCRs 3 and 4) | Region 3 (colicin) (PCR 6) | Region 4 (O157:H7 related) (PCRs 7 and 8) | Region 5 (S-adhesin) (PCRs 9–13) | Region 6 (iro) (PCRs 14–17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sfaI | 12 | − | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| sfaII | 12 | − | − | − | − | ++ | ++ |

| foc | 34 | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| fac | 1 | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| sfr | 2 | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| sfx | 4 | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ |

++, PAI III536-specific region detectable in 100% of E. coli strains expressing a certain type of S-adhesin; +, PAI III536-specific region detectable in less than 100% of the E. coli strains expressing a certain type of S-adhesin; −, PAI III536-specific region not detectable in E. coli strains expressing a certain type of S-adhesin.

Analysis of presence of PAI III536-like genetic elements in E. coli strains expressing members of S-family of fimbrial adhesins.

Based on the DNA sequence representing the left-hand part of PAI III536, we selected DNA-primer combinations in order to detect the known PAI III536 fragment in 112 different E. coli strains, including many extraintestinal isolates which are known to frequently express fimbrial adhesins belonging to the S-family of E. coli adhesins. In 35 extraintestinal and fecal strains as well as in several isolates of different intestinal E. coli pathotypes, no PAI III536-specific sequences were detectable. Among them, the presence of the iro determinant without PAI III536-specific sequence context was demonstrated in 11 extraintestinal and fecal strains. As shown in Table 2, the entire E. coli 536-specific PAI III536 fragment was not detectable by PCR in 65 E. coli strains containing genes which encode S-family fimbrial adhesins. Interestingly, in eight E. coli strains harboring the sfaI determinant, almost the entire left-hand part of PAI III536 (covered by PCRs 3 to 18) was detectable. With primers generated from conserved regions of the E. coli 536-specific sfaI gene cluster (region 4), the different S-fimbria determinants, including fac of the avian-pathogenic strain AC/I, were completely detectable in all S-fimbria-positive E. coli strains used in this study. In all cases, the different determinants coding for members of the S-adhesin family are associated with the 3′-flanking region (region 5, iro gene cluster) of the E. coli 536-specific sfaI determinant (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Some differences can be detected with respect to the 3′ region of the iro determinant and the following sequence context (PCR 18). It is very likely that these differences are mainly due to the presence of additional IS4-related sequences located downstream of iro which are absent in E. coli strain 536. With the exception of the sfaII-positive E. coli strains, the 5′-flanking region 3 (E. coli O157:H7-related sequences) of the sfaI536 determinant was also detectable upstream of the corresponding determinants of all strains expressing an adhesin of the S-adhesin family (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Sequence determination of the upstream region of the E. coli J96 foc determinant confirmed these findings, as the obtained sequences were identical with 750 bp of the upstream region of the PAI III536-located sfaI operon (data not shown). Other parts of PAI III536 (regions 1 to 3) could not be amplified by PCR in E. coli isolates harboring other subtypes of S-fimbrial adhesin determinants (Fig. 1, Table 2). However, the IS3 transposase gene embedded in a PAI III536-specific sequence context (PCR 5) could be amplified in most of the S-fimbria-positive strains tested. These results demonstrate that the different determinants of the S-fimbrial adhesin family are located within a common DNA region. They are associated with the iro gene cluster and, except for the sfaII determinant, with sequences found within the genome of E. coli strain EDL933. This common sequence context may be part of a widespread pathogenicity island or may represent a part of a commonly transferable genetic element. The iro determinant was only detectable in extraintestinal and fecal E. coli isolates. In all E. coli isolates used in this study which represent different E. coli intestinal pathotypes, no PAI III536-specific sequences were detectable.

Analysis of thrW downstream region in different E. coli strains: identification of E. coli K-12-specific genomic island.

The PCR-based analysis of the thrW downstream region, covering the chromosomal region between yafW and yagU of E. coli strain MG1655 (Fig. 1B), revealed that this strain-specific DNA sequence is not present in this form in the following eight pathogenic E. coli isolates: 536 (UPEC), J96 (UPEC), IHE3034 (MENEC), C9221a (ETEC), E2348/69 (EPEC), EDL1284 (EIEC), DPA065 (EAEC), and EDL933 (EHEC). Although not every ORF or gene in this region has been analyzed by PCR (PCRs 19 to 46; see Fig. 1B), our results imply that this ∼40-kb fragment is almost completely missing in the different E. coli strains tested. ORFs located in regions A, B, and C as well as that amplified by PCR 40 are absent in all eight strains (Fig. 1B). ORFs ykfC (PCR 28), yagI (PCR 34), and yagM (PCR 39) as well as yagP, yagR, and yagT (PCRs 41 to 43) are present in some of these pathogenic E. coli strains. With the exception of the EIEC strain EDL1284, the ORFs yagU, ykgJ, and yagV (PCRs 44 to 46) are present in all other pathogenic isolates (Fig. 1B). The PCR results have been confirmed by Southern blot analysis, underlining that, with a few exceptions, the ORFs investigated are absent in the eight pathogenic E. coli isolates used in this study.

In order to find out whether the DNA region between thrW and yagU is specific for E. coli K-12 strains, we expanded our study and screened several E. coli K-12 strains, several strains representing different E. coli pathotypes, and members of every subgroup of the ECOR strain collection for the presence of five representative ORFs which are located in the DNA region between thrW and yagV. The results presented in Table 3 clearly demonstrate that in contrast to the analyzed E. coli K-12 strains, the ORFs located between thrW and yagU were not detectable in the different E. coli isolates and ECOR strains studied. On the basis of the PCR results presented in Table 3, it can be concluded that the DNA fragment covering a region of ∼40 kb downstream of the tRNA gene thrW in E. coli MG1655 represents in this form a genomic island specific for E. coli K-12 strains and is absent in all E. coli isolates investigated in this study.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of thrW downstream region in different E. coli strains

| E. coli strain (no. tested) | No. (%) of strains with E. coli K-12-specific ORFa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yafW (PCR 19) | ykfC (PCR 28) | yagF (PCR 32) | yagT (PCR 43) | ykgJ (PCR 45) | |

| K-12 (7) | 7 (100) | 7 (100) | 7 (100) | 7 (100) | 7 (100) |

| Fecal (19) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18 (95) |

| UPEC (19) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 19 (100) |

| NBM, sepsis (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (90) |

Values in parentheses indicate the percentage of strains with a positive PCR result within every subgroup analyzed in this study.

DISCUSSION

Fimbrial adhesins of the S-adhesin family are virulence factors frequently produced by most extraintestinal E. coli isolates that cause a variety of clinical symptoms in mammals and poultry. Although the genetic organization of their determinants and the sequences of many of their encoded gene products are highly homologous, their receptor specificities vary, thus changing the host and tissue specificity. Therefore, from an evolutionary point of view, the operons coding for the members of the S-adhesin family can serve as a model system to study combinatorial gene shuffling as an adaptive process in host-pathogen interactions. The frequent occurrence of S-fimbria-encoding operons in different extraintestinal E. coli strains implies that they are located on a pathogenicity island which may have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer. The localization of other fimbrial adhesin determinants on pathogenicity islands of extraintestinal E. coli, i.e., those coding for members of the P-adhesin family, has been shown before (12, 24, 58).

The sequence analysis of the cosmid clone pANN1E6 proved that the sfaI determinant of E. coli strain 536 is located on a pathogenicity island which has been designated PAI III536 before (23). Although PAI III536 has not been completely characterized, the known sequences exhibit several characteristics which are typical of pathogenicity islands. PAI III536 is integrated at the tRNA gene thrW into the bacterial chromosome. tRNA genes frequently serve as chromosomal integration sites for bacteriophages. From our point of view, the fact that PAIs may have originated from temperate bacteriophages which have been “immobilized” within the chromosome is also reflected by the presence of mobility genes coding for integrases or transposases of mobile genetic elements on these PAIs (23). In the case of PAI III536, the tRNA gene thrW is immediately followed by an attachment site for different bacteriophages, including P22 and DLP12, and the complete integrase and excisionase gene of the O-antigen-converting bacteriophage X of Shigella flexneri. The attP sites of S. flexneri bacteriophage X and other serotype-converting Shigella phages are identical to the core attP sequence of P22 and DLP12. Additionally, the proteins encoded by the integrase genes of the O-antigen-converting Shigella phages are very similar to the corresponding proteins of P22 and DLP12 (2). The presence of sequences at the right junction site of PAI III536 with homology to integrase gene fragments of the Shigella O-antigen-converting bacteriophages SfII and SfV or to that of P22 demonstrates that this pathogenicity island may originally have evolved from integrated Shigella bacteriophages. Additionally, three regions with homology to IS elements (IS100, I3S, IS4, and iso-IS1) are located on PAI III536, thereby increasing the number of mobility genes on this pathogenicity island. Whereas the sequence of the IS100 element found on PAI III536 is identical to those frequently found on Yersinia pestis and EPEC plasmids (37, 59) the IS3 element on PAI III536 is highly homologous to a nonfunctional IS3 element found on S. flexneri pathogenicity island SHI-2 (61). These data underline the frequent presence of horizontally acquired genetic elements within pathogenicity islands.

Another typical feature of PAIs is the presence of unidentified ORFs. On PAI III536, there are two regions which show no homology to known DNA sequences but which contain ORFs that, after translation, encode proteins with similarity to hypothetical proteins of other bacterial species or plasmid-encoded proteins. Whether these ORFs are actually functional will have to be investigated in the future. Determinants coding for siderophore systems are frequently located on pathogenicity islands (55, 61, 63). The iroBCDEN operon, which is homologous to the iro gene cluster of Salmonella species, has been detected downstream of the sfaI determinant on PAI III536. In E. coli, the siderophore which is recognized by IroN is unknown, as is the function of the other genes of this operon. iroN and parts of the accompanying iroE and iroD genes have recently been demonstrated to be induced in extraintestinal E. coli isolate CP9 upon incubation in urine. Interestingly, it has been shown that the iroN gene of strain CP9 is preceded by a fragment of an IS element and by DNA sequences with homology to the prs or foc gene cluster (52). These data support our findings that the iro genes are associated with determinants coding for members of the S-adhesin family of E. coli.

The comparison of the flanking regions of S-fimbrial gene clusters in several extraintestinal E. coli isolates shows that indeed a colocalization of the corresponding determinants and common flanking regions exists. Interestingly, differences between the upstream regions of the different fimbrial determinants can be seen. The upstream region of the sfaII determinant seems to be different from that of the other determinants coding for members of the S-family of adhesins. Our results demonstrate that all determinants coding for the different members of the S-adhesin family are associated with iro genes and, with the exception of the sfaII genes, are localized in a common sequence context. This may be indicative of their localization within a common pathogenicity island or of their former acquisition within a block of commonly transferable DNA. Our results contradict the recently published finding that the iroNE. coli sequences are not strictly associated with operons coding for adhesins of the S-family (28). Furthermore, the iro-encoded siderophore system seems to be characteristic of fecal and extraintestinal E. coli isolates.

Mobile genetic elements such as plasmids, bacteriophages, and pathogenicity islands belong to a group of genomic additions that contribute in particular to the evolution of bacterial pathogens and to the evolution of bacterial species in general (18). The increasing number of genetic elements with structural similarities to pathogenicity islands in nonpathogenic bacteria led to an extension of the pathogenicity island concept to the so-called concept of genomic islands (21, 22). In recent years, much attention has been paid to the detection and characterization of pathogenicity islands and other horizontally acquired DNA fragments that have been added to the former core chromosome and confer pathogenicity or fitness on certain bacterial strains (29, 35). Few examples of deletions of large DNA fragments from the chromosome have been reported with respect to their impact on virulence properties (20, 31, 38). In most cases, these unstable DNA fragments turned out to be pathogenicity islands. The comparison of the size of the completely sequenced chromosome of E. coli strain MG1655 (4,639 kb) (10) with estimates of the genome sizes of natural E. coli isolates (ranging from 4.5 to 5.52 kb) shows that substantial differences in genome size exist among various E. coli strains (8, 9). The analysis of type-specific genome size differences among different E. coli pathotypes and E. coli MG1655 by macrorestriction demonstrated that not only the addition of DNA fragments to but also the deletion of chromosomal regions from the chromosome contribute to different genome sizes in comparison to E. coli MG1655 and consequently to different phenotypes or pathotypes (51). We identified a region of the E. coli MG1655 chromosome which is specific for E. coli K-12 strains (Fig. 1B, Table 3). This DNA fragment covers approximately 40 kb downstream of the thrW tRNA gene in strain MG1655 and is not present in this form in several extraintestinal E. coli isolates as well as in representatives of all four subgroups of the ECOR strain collection, including the A subgroup, which also includes E. coli strain K-12.

This 40-kb E. coli K-12-specific DNA region downstream of the tRNA-encoding gene thrW (b0245 to b0286) exhibits a GC content of 54%, contains several repeat elements as well as IS elements or at least parts of them (IS911A, IS30, IS5, IS1, and IS30), and consists mainly of genes whose gene products are hypothetical proteins. The presence of many mobile genetic elements in this region could explain the loss of the 40-kb fragment in many E. coli strains due to high recombinational activity in this DNA region. The central part of this region contains the argF gene, flanked by IS1 elements. This structure, only present in E. coli K-12 strains, together with the high argF GC content (59%), argues for its acquisition by horizontal gene transfer (60, 62). Interestingly, a 53-kb deletion compared to E. coli MG1655 has been identified in uropathogenic E. coli strain J96 in the vicinity of the foc determinant (51). On the other hand, the fact that the presence of this region is restricted to E. coli K-12 strains and the occurrence of several mobility genes are features which are characteristic of genomic islands. Therefore, this E. coli K-12-specific DNA fragment could represent a genomic island. Our study presents for the first time in detail the occurrence of an E. coli K-12-specific DNA region and improves our knowledge on the genome variability of E. coli strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work of the Würzburg group was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Sonderforschungsbereich 479 and by the “Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.” The Würzburg group and the Tel Aviv group cooperated in a joint research project (contract no. I-502-171-01/96) supported by the German Israeli Foundation. The Göttingen Genomics Laboratory received support from “Forschungsmittel des Landes Niedersachsen.”

We thank H. Karch (Würzburg, Germany) and H. Schroten (Düsseldorf, Germany) for the gift of several MENEC and SEPEC strains used in this study. We are grateful to A. Giammanco (Palermo, Italy) and E. Oswald (Toulouse, France) for providing the EAEC strain DPA065 and the NTEC strain S5, respectively. We thank A. Sauer (Würzburg) for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman M, Mercer A, Kusecek B, Pohl A, Heuzenroeder M, Aaronson W, Sutton A, Silver R P. Six widespread bacterial clones among Escherichia coli K1 isolates. Infect Immun. 1983;39:315–335. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.315-335.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison G E, Verma N K. Serotype-converting bacteriophages and O-antigen modification in Shigella flexneri. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01646-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azpiroz M F, Rodriguez E, Lavina M. Structure, function, and origin of the Microcin H47 ATP-binding cassette exporter are similar to those of colicin V. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:969–972. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.969-972.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babai R, Blum-Oehler G, Stern B E, Hacker J, Ron E Z. Virulence patterns from septicemic Escherichia coli O78 strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;149:99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babai R, Stern B E, Hacker J, Ron E Z. A new fimbrial gene cluster of the S-fimbrial adhesin family. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5901–5907. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5901-5907.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachmann B J. Derivatives and genotypes of some mutant derivatives of Escherichia coli K-12. In: Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. 1st ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1987. pp. 1190–1219. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergthorsson U, Ochman H. Distribution of chromosomal length variations in natural isolates of Escherichia coli. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:6–16. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergthorsson U, Ochman H. Heterogeneity of genome sizes among natural isolates of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5784–5789. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5784-5789.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blattner F R, Plunkett III G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Villes J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blum G, Ott M, Cross A, Hacker J. Virulence determinants of Escherichia coli O6 extraintestinal isolates analysed by Southern hybridizations and DNA long range mapping techniques. Microb Pathog. 1991;10:127–136. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90073-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blum G, Ott M, Lischewski A, Ritter A, Imrich H, Tschäpe H, Hacker J. Excision of large DNA regions termed pathogenicity islands from tRNA-specific loci in the chromosome of an Escherichia coli wild-type pathogen. Infect Immun. 1994;62:606–614. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.606-614.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blum G, Heesemann J, Kranzfelder D, Scheutz F, Hacker J. Abortion by a woman carrying a pathogenic Escherichia coli of serotype O12:K1:H7. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;16:153–155. doi: 10.1007/BF01709475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonacorsi S P, Clermont O, Tinsley C, Le Gall I, Beaudoin J C, Elion J, Nassif X, Bingen E. Identification of regions of the Escherichia coli chromosome specific for neonatal meningitis-associated strains. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2096–2101. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2096-2101.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd E F, Hartl D L. Chromosomal regions specific to pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli have a phylogenetically clustered distribution. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1159–1165. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1159-1165.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burghoff R, Pallesen L, Krogfelt K A, Newman J V, Richardson M, Bliss J L, Laux D C, Cohen P S. Utilization of the mouse large intestine to select an Escherichia coli F-18 DNA sequence that enhances colonizing ability and stimulates synthesis of type 1 fimbriae. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1293–1300. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1293-1300.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caprioli A, Falbo V, Ruggeri F M, Minelli F, O/rskov I, Donelli G. Relationship between cytotoxic necrotizing factor production and serotype in hemolytic Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:758–761. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.758-761.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobrindt U, Hacker J. Plasmids, phages and pathogenicity islands: lessons on the evolution of bacterial toxins. In: Allouf J E, Freer J, editors. The comprehensive sourcebook of bacterial protein toxins. London, England: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donnenberg M S, Tzipori S, McKee M L, O'Brien A D, Alroy J, Kaper J B. The role of the eae gene of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in intimate attachment in vitro and in a porcine model. J Clin Investig. 1993;3:1418–1424. doi: 10.1172/JCI116718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fetherston J D, Schuetze P, Perry R D. Loss of the pigmentation phenotype in Yersinia pestis is due to the spontaneous deletions of 102 kb of chromosomal DNA, which is flanked by a repetitive element. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2693–2704. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hacker J, Kaper J B. The concept of pathogenicity islands. In: Kaper J B, Hacker J, editors. Pathogenicity islands and other mobile virulence elements. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hacker J, Kaper J B. Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of microbes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:641–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Janke B, Nagy G, Goebel W. Pathogenicity islands of extraintestinal Escherichia coli. In: Kaper J B, Hacker J, editors. Pathogenicity islands and other mobile virulence elements. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Mühldorfer I, Tschäpe H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1089–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hacker J, Kestler H, Hoschützky H, Jann K, Lottspeich F, Korhonen T K. Cloning and characterization of the S fimbrial adhesin II complex of an Escherichia coli O18:K1 meningitis isolate. Infect Immun. 1993;61:544–550. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.544-550.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hacker J, Bender L, Ott M, Wingender J, Lund B, Marre R, Goebel W. Deletions of chromosomal regions coding for fimbriae and hemolysins occur in vitro and in vivo in various extraintestinal Escherichia coli isolates. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:213–225. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90048-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hull R A, Gill E R, Hsu P, Minshew B H, Falkow S. Construction and expression of recombinant plasmids encoding type 1 or d-mannose-resistant pili from a urinary tract infection Escherichia coli isolate. Infect Immun. 1981;33:933–938. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.3.933-938.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson J R, Russo T A, Tarr P I, Carlino U, Bilge S S, Vary J C, Jr, Stell A L. Molecular epidemiological and phylogenetic associations of two novel putative virulence genes, iha and iroNE. coli, among Escherichia coli isolates from patients with urosepsis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3040–3047. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.3040-3047.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaper J B, Hacker J, editors. Pathogenicity islands and other mobile virulence elements. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan A S, Kniep B, Ölschläger T A, van Die I, Korhonen T K, Hacker J. Receptor structure for F1C fimbriae of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3541–3547. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3541-3547.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knapp S, Hacker J, Jarchau T, Goebel W. Large, unstable inserts in the chromosome affect the virulence properties of uropathogenic Escherichia coli O6 strain 536. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:22–30. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.1.22-30.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korhonen T K, Valtonen M V, Parkkinen J, Väisänen-Rhen V, Finne J, O/rskov I, O/rskov F, Svenson S B, Mäkelä P H. Serotype, hemolysin production, and receptor recognition of Escherichia coli strains associated with neonatal sepsis and meningitis. Infect Immun. 1985;48:486–491. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.486-491.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korhonen T K, Väisänen-Rhen V, Rhen M, Pere A, Parkkinen J, Finne J. Escherichia coli recognizing sialyl galactosides. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:762–766. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.2.762-766.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krallmann-Wenzel U, Ott M, Hacker J, Schmidt G. Chromosomal mapping of genes encoding mannose-sensitive (type I) and mannose-resistant F (P) fimbriae of Escherichia coli O18:K5:H5. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;49:315–321. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(89)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawrence J G, Ochman H. Molecular archaeology of the Escherichia coli genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9413–9417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine M M, Bergquist E J, Nalin D R, Waterman D A, Hornick R B, Young C R, Scotman S, Row B. Escherichia coli strains that cause diarrhea but do not produce heat labile or heat stabile enterotoxins und are not invasive. Lancet. 1978;i:1119–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindler L E, Plano G V, Burland V, Mayhew G F, Blattner F R. Complete DNA sequence and detailed analysis of the Yersinia pestis KIM5 plasmid encoding murine toxin and capsular antigen. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5731–5742. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5731-5742.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maurelli A T, Fernandez R E, Bloch C A, Rode C K, Fasano A. Black holes and bacterial pathogenicity: a large genomic deletion that enhances the virulence of Shigella spp. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3943–3949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mühldorfer I, Hacker J. Genetic aspects of Escherichia coli virulence. Microb Pathog. 1994;16:171–181. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagy G, Dobrindt U, Kupfer M, Emödy L, Karch H, Hacker J. Expression of hemin receptor molecule ChuA is influenced by RfaH in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain 536. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1924–1928. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1924-1928.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nowicki B, Vuopio-Varkila J, Viljanen P, Korhonen T K, Mäkelä P H. Fimbrial phase variation and systemic Escherichia coli infection studied in the mouse peritonitis model. Microb Pathog. 1986;1:335–347. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(86)90066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Brien A D, Lively T A, Chang T W, Gorbach S L. Purification of Shigella dysenteriae 1 (Shiga)-like toxin from Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain associated with haemorrhagic colitis. Lancet. 1983;ii:573. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ochman H, Selander R K. Standard reference strains of Escherichia coli from natural populations. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:690–693. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.2.690-693.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oefner P, Hunicke-Smith S P, Chiang L, Dietrich F, Mulligan J, Davis R W. Efficient random subcloning of DNA sheared in a recirculating point-sink flow system. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3879–3886. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.20.3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O/rskov I, O/rskov F. Escherichia coli in extraintestinal infections. J Hyg. 1985;95:551–575. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400060678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ott M, Hoschützky H, Jann K, van Die I, Hacker J. Gene clusters for S fimbrial adhesin (sfa) and F1C fimbriae (foc) of Escherichia coli: comparative aspects of structure and function. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3983–3990. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.3983-3990.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ott M, Hacker J, Schmoll T, Jarchau T, Korhonen T K, Goebel W. Analysis of the genetic determinants coding for the S-fimbrial adhesin (sfa) in different Escherichia coli strains causing meningitis or urinary tract infections. Infect Immun. 1986;54:646–653. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.646-653.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ott M, Bender L, Blum G, Schmittroth M, Achtman M, Tschäpe H, Hacker J. Virulence patterns and long-range genetic mapping of extraintestinal Escherichia coli K1, K5, and K100 isolates: use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2664–2672. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2664-2672.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pawelzik M, Heesemann J, Hacker J, Opferkuch W. Cloning and characterization of a new type of fimbriae (S/FlC related fimbria) expressed by an Escherichia coli O75:K1:H7 blood culture isolate. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2918–2924. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.11.2918-2924.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perna N T, Plunkett III G, Burland V, Mau B, Glasner J D, Rose D J, Mayhew G F, Evans P S, Gregor J, Kirkpatrick H A, Pósfai G, Hackett J, Klink S, Boutin A, Shao Y, Miller L, Grotbeck E J, Davis N W, Lim A, Dimalanta E T, Potamousis K D, Apodaca J, Anantharaman T S, Lin J, Yen G, Schwartz D C, Welch R A, Blattner F R. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature. 2001;409:529–533. doi: 10.1038/35054089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rode C K, Melkerson-Watson L J, Johnson A T, Bloch C A. Type-specific contributions to chromosome size differences in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1999;19:230–236. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.230-236.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Russo T A, Carlino U B, Mong A, Jodush S T. Identification of genes in an extraintestinal isolate of Escherichia coli with increased expression after exposure to human urine. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5306–5314. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5306-5314.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmoll T, Hoschützky H, Morschhäuser J, Lottspeich F, Jann K, Hacker J. Analysis of genes coding for the sialic acid-binding adhesin and two other minor fimbrial subunits of the S-fimbrial adhesin determinant of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1735–1744. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schubert S, Rakin A, Karch H, Carniel E, Heesemann J. Prevalence of the “high-pathogenicity island” of Yersinia species among Escherichia coli strains that are pathogenic to humans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:480–485. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.480-485.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Staden R, Beal K F, Bonfield J K. The Staden package 1998. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:115–130. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sussman M. Escherichia coli and human disease. In: Sussman M, editor. Escherichia coli: mechanisms of virulence. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 3–48. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swenson D L, Bukanov N O, Berg D E, Welch R A. Two pathogenicity islands in uropathogenic Escherichia coli J96: cosmid cloning and sample sequencing. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3736–3743. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3736-3743.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tobe T, Hayashi T, Han C G, Schoolnik G K, Ohtsubo E, Sasakawa C. Complete DNA sequence and structural analysis of the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adherence factor plasmid. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5455–5462. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5455-5462.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Vliet F, Boyen A, Glansdorff N. On interspecies gene transfer: the case of the argF gene of Escherichia coli. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1988;139:493–496. doi: 10.1016/0769-2609(88)90111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vokes S A, Reeves S A, Torres A G, Payne S M. The aerobactin iron transport system genes in Shigella flexneri are present within a pathogenicity island. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:63–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.York H K, Stodolsky M. Characterization of P1argF derivatives from Escherichia coli K12 transduction. I. IS1 elements flank the argF gene segment. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;181:230–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00268431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou D, Hardt W-D, Galán J. Salmonella typhimurium encodes a putative iron transport system within the centisome 63 pathogenicity island. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1974–1981. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1974-1981.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zingler G, Ott M, Blum G, Falkenhagen U, Naumann G, Sokolowska-Köhler W, Hacker J. Clonal analysis of Escherichia coli serotype O6 strains from urinary tract infections. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:299–310. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90048-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zingler G, Blum G, Falkenhagen U, O/rskov I, O/rskov F, Hacker J, Ott M. Clonal differentiation of uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates of serotype O6:K5 by fimbrial antigen typing and DNA long-range mapping techniques. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1993;182:13–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00195947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]