Abstract

Abnormal fetal growth increases risks of childhood health complications. Vitamin A supplementation (VAS) is highly accessible, but literature inconsistency regarding effects of maternal VAS on fetal and childhood growth outcomes exists, deterring pregnant women from VAS during pregnancy. This meta-analysis aimed to analyze effects of vitamin A only or vitamin A+co-intervention during pregnancy in healthy mothers (MH) or with complications (MC, night blindness and HIV positive) on perinatal growth outcomes, also assess VAS dose impacts. The Cochrane Library, PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Embase and Web of Science databases were searched from inception to July 15, 2021. We covered subgroup analyses, including VAS in MH or MC within randomized controlled trial (RCT) or observational studies (OS). Fifty-five studies were included in this meta-analysis (426,098 pregnancies).

Vitamin A decreased risk of preterm birth by 9% in MH-RCT (P<0.001), by 62% in MH-OS (P=0.029), by 10% in MC-RCT (P=0.089); decreased LBW by 24% in MC-RCT (P = 0.032); increased neonatal weight in MC-RCT (SMD 0.96; P=0.051). Besides, vitamin A + co-intervention decreased risks of preterm by 18% in MH-OS (P=0.021); LBW by 25% in MH-OS (P<0.001); by 32% in MC-RCT (P=0.006); decreased neonatal defects by 33% in MH-OS (P = 0.064); decreased anemia by 25% in MH-OS (P=0.0003); increased neonatal weight in MH-OS (SMD 0.51; P=0.014); and increased neonatal length in MH-OS (SMD 1.83; P=0.013).

Meta-regression of VAS dose with individual outcomes was not significant, and no side effects were observed for VAS doses up to 4000 mcg(RAE/d). Regardless of maternal health conditions, VAS during pregnancy can safely and effectively improve fetal development and neonatal health even in mothers without VAD.

Keywords: pregnancy, vitamin A deficiency, supplementation, fetal growth, birth outcomes, child health

1. Introduction

During pregnancy, fetuses have high demand of vitamin A for meeting developmental needs, which can be substantial, especially in the last trimester (Maia et al. 2019; Z. Zhang et al. 2018). As pregnant women in rural areas and developing countries have a limited access to foods with high bioavailability of vitamin A, addressing vitamin A deficiency (VAD) during pregnancy is a priority of World Health Organization (WHO) during past decades (McGuire 2012). According to WHO, approximate 19 million pregnant women are currently in high risks of VAD (‘The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Child Population by Age Group in the United States. Https://Datacenter.Kidscount.org/Data/Tables/101-Child-Population-by-Age-Group#detailed/1/Any/False/1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133/62,63. Accessed September 5,2021.’; ‘Children in the World. The Global Children’s Right Situation, by Country. Https://Www.Humanium.Org/En/Children-World/. Accessed August 27, 2021.’; Chagas et al. 2013; ‘World Health Organization. Adolescent Pregnancy. Https://Www.Who.Int/News-Room/Fact-Sheets/Detail/Adolescent-Pregnancy. Accessed September 4, 2021’; Stevens et al. 2015). VAD during pregnancy not only causes maternal ocular manifestation, anemia and sepsis, but also seriously impairs the development of fetal skeletal muscle, heart, respiratory and nerve systems, attributing to high risks of preterm birth (< 37 weeks), low birth weight (LBW; < 2500 g) and childhood defects (Radhika et al. 2002; Sommer 2008; Huerta et al. 2002; World Health Organization 2009). Besides being major causes of birth mortality (>35%) and morbidity (Walani 2020), preterm and LBW also cause health problems of children later in life. For example, accumulative evidences show that preterm and LBW increase risks of child obesity by > 1.5 times and cognitive deficits by > 20 times (Id, Basel, and Singh 2020; Y. Chen et al. 2021; ‘WHA Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Low Birth Weight Policy Brief. World Health Organization, 2014.’; UNICEF, WHO. Low Birth Weight: Country, Regional and Global Estimates. UNICEF, New York, 2004; Y.-T. Chen et al. 2021). Thus, ensuring adequate vitamin A intake during pregnancy is essential for improving fetal development and childhood health.

Vitamin A supplementation (VAS) is a common strategy to prevent VAD during pregnancy, which is also recommended by WHO (World Health Organization 2009). Recent multiple meta-analyses show that VAS during pregnancy can effectively reduce risks of maternal night blindness by 30%, anemia by 36%, clinical infections by 73%, and mortality by 40% (Maternal et al. 2020; Thorne-Lyman and Fawzi 2012; Radhika et al. 2002; Jr et al. 1999; Fawzi et al. 1998). Despite these positive reports, inevitable large variations within and among VAS clinical studies, such as underlying maternal health conditions, background level of VAD, co-interventions (smoking, alcohol drinking etc.), VAS dose and duration, substantially contribute to inconsistent results of maternal VAS in benefiting fetal growth and birth outcomes (Y. Zhang et al. 2020; J. Chen et al. 2021). The meta-analysis in 2012, that is the only available meta-analysis in recent years, failed to observe the effectiveness of VAS in reducing risks of preterm birth, small for gestational age, still birth and miscarriage (Thorne-Lyman and Fawzi 2012), which causes doubts, confusions and less incentives of maternal VAS in preventing VAD-induced adverse birth outcomes. However, this previous meta-analysis only included limited case studies, and did not consider the maternal health conditions and co-interventions as essential factors in altering VAS efficacy and neonatal outcomes (Thorne-Lyman and Fawzi 2012); these inadequacies in analysis might significantly increase variations which complicate data interpretation, likely attributing to the lack of VAS effectiveness in benefiting fetal growth and birth outcomes.

In order to alleviate public and healthcare confusions, and provide solid evidence for the effects of maternal VAS on fetal and childhood healthy growth, we included available studies during last decades and conducted a thorough meta-analysis and meta-regression. In addition, we accounted maternal health conditions by separating healthy mothers (MH) and those with complications (MC), also considered intervention methods by separating into vitamin A only and vitamin A + co-intervention. The objective of the current study was to analyze the efficacy of vitamin A or vitamin A + co-intervention, in both MH and MC, in improving perinatal growth outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

This meta-analysis was performed and analyzed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) instructions, and the checklist was reported in Supplementary Table S1 (Liberati et al. 2009). Meta-analysis protocol was approved through the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42021262432). PICOS guideline (Population; Intervention; Comparison; Outcome; Study design) directed the study eligibility criteria (Smith 2020; Screening and Aneuploidy 2015).

2.1.1. Population

Women (>16 years) during pregnancy, who received placebo or VAS (multivitamin including vitamin A, food rich in vitamin A (vitamin A + co-intervention), or vitamin A only), were the interested population in the current meta-analysis. The included participants in the two comparable groups should be under similar situations. The two groups enrolled in analysis should be at similar age, gestation age, race, education achievement, marital status, parity, body mass index (BMI), energy intake, family income and health conditions. The included population did not receive extra vitamin A supplementation before enrolling in the study. Pregnant women of included studies were sub-grouped into MH (no reported underlying health issues) and MC (HIV positive and night blindness).

2.1.2. Intervention

Vitamin A intervention included various vitamin A only supplements (including retinol, β-carotene, preformed vitamin A, retinol equivalents), and vitamin A+ co-intervention (including multivitamins with vitamin A, VAS together with others, such as tobacco use, dietary pattern that is rich in vitamin A, and other possible ways) to increase vitamin A intake levels. In order to decrease the effect of confounders, and to discern “the major effect of vitamin A intervention”, we performed subgroup analysis including “maternal vitamin A only” and “maternal vitamin A + co-intervention” in both MH and MC groups, which were further separated by randomized controlled trials (RCT) or observational studies (OS).

2.1.3. Comparison

Quantified outcomes from VAS during pregnancy were compared with outcomes of placebo group with no or less VAS in various types, frequencies, enrolled time, and durations [e.g., β-carotene (type), 4.5 mg/d (frequency), from the 14 week of gestation (enrolled time), and 27 weeks of supplementation (duration)].

2.1.4. Outcomes

Maternal VAS outcomes included neonatal weight (< 2 months old), preterm (< 37 weeks of gestation), LBW (< 2500 g), mortality, neonatal defects, anemia, body mass, neonatal length, and adolescent body mass (1-12 years).

2.1.5. Study design

All randomized controlled and observational trials were included. Other studies (e.g., meta-analysis, reviews) were not included in this meta-analysis.

2.2. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two independent individuals (GL, YT) did data search through Cochrane Library, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Embase, and PubMed databases. Data search included interventional and observational human studies in English language. Keywords in searching were built with items related to vitamin A sources, pregnancy, and perinatal child growth outcomes with more details in Supplementary Table S2. Library search was from inception to July 15, 2021.

Two independent individuals screened title and abstracts followed by full text screening. Data extraction protocol is listed in Supplementary Table S3. When inconsistent evaluation existed between individuals during data extraction, the article was further sent to the Article Decision Committee (MD, MJ) for final decision. DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) was used to remove reference replicates before screening. Study inclusion was based on data completeness and enough sample size (n ≥ 2). Extracted data included first author, year, title, study design, country, sample size, basic health condition of participants, VAS dose, vitamin A type, preterm, LBW, mortality, total defects, anemia, child weight and others related to child growth and health. Librarians were contacted for article data completeness when necessary. Altogether, 8 articles were requested and fully offered by librarians.

Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) for interventional study (RCT) and the risk of bias in non-randomized studies – of interventions assessment tool (ROBINS-1) for observational study (OS) (McGuinness and Higgins 2020)(Supplementary Table S4) were used to judge data quality. In detail, interventional studies were mainly examined by the following criteria: a) randomization process; b) deviations from intended intervention; c) missing data; d) outcome measurements; e) selection of the reported result following blinded design and single outcome. Observational studies were mainly included criteria: a) confounding; b) participant selection; c) intervention classification; d) deviations from intended interventions; e) missing data; f) outcomes.

Two individuals (GL, YT) did the quality assessment of all included studies according to the requirement of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) for outcomes (Wells G et al. 2014). In detail, study quality assessment followed the following criteria: (a) study design (interventional or observational study; for acute vitamin A supplementation, all the non-randomized studies were combined as observational studies for GRADE assessment); (b) risk of bias; (c) inconsistency; (d) indirectness; (e) imprecision and other considerations. Data were collected in Excel (Excel, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted with R v.4.0.2 software (Team 2021) and the metafor package (Viechtbauer 2010). Random model was used in the meta-analysis [Equation 1]. Subgroup analysis was based on maternal health conditions (MH or MC), intervention (vitamin A only or vitamin A + co-intervention), as well as study design (RCT or OS). In detail, the subgroup analysis criteria were as follows: MH – vitamin A only – RCT/OS, MH- vitamin A + co-intervention – RCT/OS, MC – vitamin A only – RCT/OS, and MC – vitamin A + co-intervention – RCT/OS. Dichotomous variable (e.g., preterm) comparison was performed by ‘transf’ method based on effect size (ES) of risk ratio (RR) (Rücker et al. 2009; Y. Chen et al. 2021). Continuous variable (e.g., body weight) comparison was performed by ES of standard mean difference (SMD) [Equation 2] (Viechtbauer 2010; Crippa and Orsini 2016; G. Ma and Chen 2020; Guiling Ma, Chen, and Ndegwa 2022).

| (Equation 1) |

Where: yi = the vitamin A supplementation effects in offspring outcome of i-th study, θi = the true effect of i-th study, ei = the sample error (ei ~ N(0, vi), vi = the sample variance of i-th study, μ = true effects of mean (μi ~ N(0, τ2), and τ2 = the true effects variance).

| (Equation 2) |

Where: spi = the pooled SD of offspring outcomes in placebo and vitamin A groups of i-th study, mdpe = the offspring outcomes of vitamin A group, and mdps = the offspring outcome of placebo group.

| (Equation 3) |

Where: θk= the observed effect size of k-the study, βi = the coefficient (i = 1, 2 … 5), xk = predicator (vitamin A doses of the pregnant mothers) in k-th study, ϵk= the sample error of k-th study, ∁k= the between-study heterogeneity of k-th study.

| (Equation 4) |

| (Equation 5) |

Where: βi = the regression coefficient (i = 1, 2 … 5), SEβI = the standard error of the regression coefficients, = the estimated total heterogeneity based on the random model, and = the total heterogeneity based on the mixed model.

Restricted maximum-likelihood estimator (REML) (Langan et al. 2019)was applied in meta-analysis. Confidence interval was adjusted using the Knapp and Hartung method (Knapp and Hartung 2003). Heterogeneity was estimated by Q test of χ2 and I2 (Higgins and Thompson 2002; Knapp and Hartung 2003; Ioannidis, Patsopoulos, and Evangelou 2007). Range of I2 indicates low (<50%), medium (50-75%), and high (>75%) data heterogeneity (Higgins et al. 2003). In meta-regression, no-intercept regression of continuous/ dichotomous variables were analyzed with SMD / logRR using the random model (Guyatt et al. 2011). No-intercept was according to the assumption when no vitamin A supplementation SMD/log RR is zero (Harbord, Egger, and Sterne 2006). The dose-response correlation between offspring outcomes and maternal VAS were analyzed by the linear model with maximum likelihood estimator (Greenland and Longnecker 1992) [Equation 3]. The vitamin A dose was expressed as RAE/d according to USDA/NIH dietary supplement ingredient database (USDA 2017). Model significance test was conducted using t-test (Equation 4). Permutation test and R2 (Equation 5) were used to assess the robustness of meta-regression (Guiling Ma, Chen, and Ndegwa 2021; Phillip I. Good 1992).

2.4. VAD and VAS efficacy distribution map development

All map analysis was performed by QGIS 3.20 (2021) (‘QGIS Development Team (2021). QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. Http://Qgis.Osgeo.Org’). Basic layer was ‘world map’ with boundaries. Data Source Manager was used to include extra layers. The geometry coordinate reference system was performed under EPSG:4326 – WGS 84. Layer properties were built by Join feature and Symbology feature. Map was exported with New Print Layout feature.

3. Results

3.1. Data Search Results and Included Studies

Initial searching with no language restriction resulted in 141,486 references (Fig. 1). After English language limitation, abstract screening and duplicates exemption, 313 full texts were eligible for data extraction. After exclusion of reviews and studies with no eligible VAS interventions (Supplementary Table S5), 55 studies were included in this meta-analysis, covering 294,204 pregnancies with vitamin A interventions, and 131,894 pregnancies in placebo (Supplementary Table S6).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of included studies for meta-analysis

Populations of included studies were from Malawi, Italy, New Jersey, USA, South Africa, Nepal, Netherlands, India, Malawi, France, Iceland, Tanzania, Denmark, Zimbabwe, Quebec, New Zealand, Japan, Egypt, Bangladesh, United Kingdom, Spain, and China (Supplementary S6). Vitamin A types included β-carotene, preformed vitamin A, retinol equivalents, food sources rich in vitamin A (e.g., cod liver oil), retinyl palmitate, and retinoids. In those studies, VAS mainly started at the second trimester of gestation, and daily doses ranged from 100 to 7000 mcg RAE/d.

3.2. Study Quality, Bias, and Result Sensitivity

Because of variations and heterogeneity within and among studies, we used Rob2 and ROBINS tools to analyze publication bias and study quality (McGuinness and Higgins 2020), and GRADE to assess study quality and result sensitivity (Balshem et al. 2011). Studies included in this meta-analysis were in low risk (Supplementary Table S7). In evaluating result sensitivity, the major critical and important outcomes were under moderate to high certainty, and some outcomes were under low certainty, majorly due to inconsistency of included studies (Supplementary Table S8).

3.3. Meta-Analysis Outcomes

3.3.1. Preterm birth

Eighteen studies analyzed preterm birth RR in pregnancies with vitamin A interventions (n = 86,220 births), showing a decreased risk of preterm birth by 19% (RR, 0.81; 95% CI 0.73, 0.91; I2 = 90.6% CI 85.9%, 92%; P = 0.0004; Fig. 3). In subgroup analysis, vitamin A only (RCT) (n = 60,901; RR, 0.91; 95% CI 0.86, 0.95; I2 = 24.7% CI 5.1%,76.0%; P < 0.0001), vitamin A only (OS) (n = 9,774; RR, 0.38; 95% CI 0.16, 0.90; I2 = 82.0% CI 35.1%, 96.2%; P = 0.029) and vitamin A + co-interventions (OS) (n = 12,198; RR, 0.82; 95% CI 0.70, 0.97; I2 = 72.7% CI 68.8%, 90%; P = 0.021) in MH significantly decreased the risk of preterm birth (Fig. 2 and 3). Vitamin A only (RCT) (n = 2,193; RR, 0.90; 95% CI 0.80, 1.02; I2 = 0.05% CI 0.0%, 83.5%; P = 0.089) in MC tended to reduce the risk of preterm birth (Fig. 2 and 3). These data showed that maternal vitamin A supplementation can effectively decrease the risk of preterm birth.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot presenting influence of vitamin A only and vitamin A + co-intervention of pregnant healthy mothers (MH) or mothers with complications (MC) within randomized controlled trial (RCT) or observational studies (OS) on risk ratio (RR) of preterm birth. Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

Fig. 2.

Summary of forest plot showing effects of vitamin A only and vitamin A + co-intervention during pregnancy in healthy mothers (MH) or mothers with complications (MC), within randomized controlled trial (RCT) or observational studies (OS) in influencing neonatal weight (standard mean difference, SMD), risk ratio (RR) of preterm birth (<37 week of gestation), RR of low birth weight (< 2500 g), RR of mortality, RR of total defects, RR of anemia, neonatal length (SMD), and child body weight (SMD). The 95% confidence interval was included in the forest plot.

3.3.2. Low birth weight (LBW)

Fifteen studies (n = 76,997) reported LBW risk from pregnancies with vitamin A intervention, showing an overall reduced LBW risk (RR, 0.84; 95% CI 0.77, 0.92; I2 = 90.3% CI 89.2%, 90.9%; P = 0.0002; Fig. 4). In subgroup analyses, significant decrease of LBW risk was also observed in vitamin A + co-intervention in MH(OS) (n = 7,760; RR, 0.75; 95% CI 0.66, 0.86; I2 = 0.0% CI 0.0%, 79.2%; P < 0.0001; Fig. 2 and 4), vitamin A only in MC(RCT) (n = 3,327; RR, 0.76; 95% CI 0.60 0.98; I2 = 63.3% CI 59.2%, 91.2%; P = 0.032; Fig. 2 and 4), and vitamin A + co-intervention in MC (RCT) (n = 1,118; RR, 0.68; 95% CI 0.52 0.90; I2 = 0.0% CI 0.0%, 0.0%; P = 0.006; Fig. 2 and 4). LBW risk in vitamin A only in MH was not affected (Fig. 2 and 4). These data show that vitamin A intervention during pregnancy effectively decreases the risk of LBW, especially in MC.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot presenting influence of vitamin A only and vitamin A + co-intervention of pregnant healthy mothers (MH) or mothers with complications (MC) within randomized controlled trial (RCT) or observational studies (OS) on risk ratio (RR) of low birth weight. Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

3.3.3. Neonatal body weight

Forty studies (n = 225,837 births) showed vitamin A interventions during pregnancy had no effects on neonatal weight (SMD, 0.25; 95% CI −0.07, 0.56; I2 = 99.9% CI 99.8%,99.9%; P = 0.120; Supplementary Fig S1). In subgroup analysis, vitamin A + co-interventions in MH(OS) (n = 142,369 births; SMD, 0.51; 95% CI 0.10, 0.91; I2 = 99.9% CI 99.1% 99.9%; P = 0.014) and vitamin A only in MC(RCT) (n = 4873 births; SMD, 0.96; 95% CI 0.0, 1.92; I2 = 99.6% CI 99.4%, 99.6%; P = 0.051) increased neonatal weight (Supplementary Fig S1 & Fig. 2). Vitamin A only in MH(RCT) (n = 73,269 births; SMD, 0.18; 95% CI −0.08, 0.43; I2 = 99.5% CI 99.5%, 99.6%; P = 0.177), MH(OS) (n = 2,587 births; SMD, −0.70; 95% CI −1.82, 0.42; I2 = 99.3% CI 96.3%, 99.6%; P = 0.219), and vitamin A + co-intervention in MH(RCT) (n = 310 births; SMD, 0.21; 95% CI −0.40, 0.81; I2 = 84.1% CI 34.6%, 96.1%; P = 0.503), MC(RCT) (n = 1,113 births; SMD, −1.07; 95% CI −3.70, 1.56; I2 = 99.7% CI 99.5%, 99.8%; P = 0.424), MC(OS)(n = 969 births; SMD, 1.72; 95% CI −1.58, 5.03; I2 = 99.7% CI 99.5%, 99.8%; P = 0.307) had no effects on neonatal weight (Supplementary Fig S1 & Fig. 2). Overall, these results show that VAS only increases neonatal weight in the vitamin A + co-intervention MH(OS) and vitamin A only MC(RCT) group.

3.3.4. Neonatal body length

Sixteen studies reported neonatal body length (n = 47,648) following vitamin A intervention during pregnancy, showing no significant increase of neonatal length (SMD 0.42, 95% CI −0.14,0.98; I2 = 99.8% CI 98.9%, 99.9%; P = 0.138; Fig. 5). In subgroup analysis, vitamin A + co-intervention in MH(OS) increased neonatal length (SMD 1.83; 95% CI 0.39, 3.26; I2 = 99.3% CI 98.3%, 99.9%; P = 0.013; Fig. 5), but vitamin A only in MH(RCT) (SMD −0.10; P = 0.297; Fig. 5) and MH(OS) (SMD −0.03; P = 0.728; Fig. 5) had no effects. Overall, these results show that VAS benefits neonatal body length in vitamin A + co-intervention MH (OS).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot presenting influence of vitamin A only and vitamin A + co-intervention of pregnant healthy mothers (MH) or mothers with complications (MC) within randomized controlled trial (RCT) or observational studies (OS) on standard mean difference (SMD) of neonatal length. Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

3.3.5. Neonatal mortality

Fifteen studies reported mortality risk following vitamin A interventions during pregnancy (n = 217,300), showing no notable decrease in overall neonatal mortality (RR, 0.97; 95% CI 0.92 1.03; I2 = 50.8% CI 41.5%, 76.6%; P = 0.299; Supplementary Fig. S2). In either MH(RCT) or MC(RCT) subgroups, vitamin A only and vitamin A + co-interventions had no significant effect on neonatal mortality risk (Supplementary Fig. S2).

3.3.6. Neonatal anemia

Four studies reported neonatal anemia risk from vitamin A interventions during pregnancy, showing a notable decrease in the risk of overall anemia risk (n = 2,061; RR 0.80; 95% CI 0.68, 0.94; I2 = 59.4% CI 47.9%, 65.5%; P = 0.009; Fig. 6). In subgroup analysis, vitamin A + co-intervention in MH(OS) also reduced the risk of neonatal anemia (n = 723; RR 0.75; 95% CI 0.64 0.88; I2 = 0.0% CI 0.0%, 89.6%; P = 0.0003; Fig. 2&6). Vitamin A only in MH(RCT) did not affect neonatal anemia risk (n = 641; P = 0.796; Fig. 2&6).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot presenting influence of vitamin A only and vitamin A + co-intervention of pregnant healthy mothers (MH) or maternal with complications (MC) within randomized controlled trial (RCT) or observational studies (OS) on risk ratio (RR) of neonatal anemia. Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

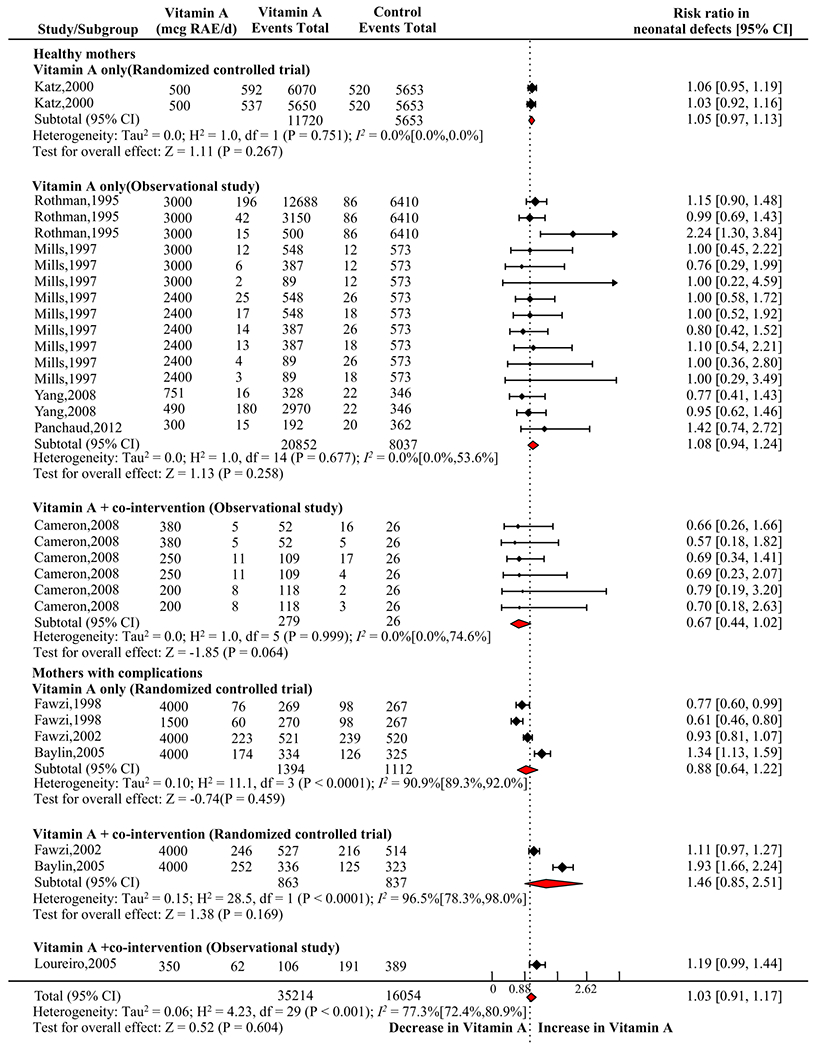

3.3.7. Neonatal defects

Ten studies reported neonatal defect risk following vitamin A interventions during pregnancy, showing no significant overall effects (n = 51,268; RR, 1.03; 95% CI 0.91, 1.17; I2 = 77.3% CI 72.4%, 80.9%; P = 0.604; Fig. 7). In subgroup analysis, a trend of reduction in total defect risk was observed in vitamin A + co-intervention in MH(OS) (n = 305; RR, 0.67; 95% CI 0.44, 1.02; I2 = 0.0% CI 0.0%, 74.6%; P = 0.064; Fig. 2&7). However, vitamin A only (RCT) (n = 17373; P = 0.267), vitamin A only (OS) (n = 28,889; P = 0.258) in MH, and vitamin A only (OS) (n =2,506; P = 0.459), vitamin A + co-interventions (RCT) (n =1,700; P = 0.169) in MC had no effects.

Fig. 7.

Forest plot presenting influence of vitamin A only and vitamin A + co-intervention of pregnant healthy mothers (MH) or mothers with complications (MC) within randomized controlled trial (RCT) or observational studies (OS) on risk ratio (RR) of neonatal total defects. Error bars show 95% confidence interval.

3.3.8. Children body weight

Only two studies included child (1 < age < 12 years) body weight (n = 2,075) following vitamin A intervention during pregnancy, showing no notable influence on overall body weight (SMD −0.67, 95% CI −1.65 0.31; I2 = 99.4% CI 98.9%, 99.7%; P = 0.182; Supplementary Fig. S3). In the subgroup analysis, vitamin A only in MH(RCT) (n = 1,189; P = 0.772), and vitamin A only in MC(RCT) (n = 432; P = 0.379), and vitamin A + co-intervention in MC(RCT) (n = 454; P = 0.268) did not alter child body weight.

3.4. Meta-regression outcomes and sensitivity analysis

Meta-regression was conducted to assess dose effects of VAS on fetal growth and childhood outcomes (Supplementary Table S9). All outcomes were not significantly altered by increased VAS dose during pregnancy, ranging from 200 to 7000 mcg RAE/d (P < 0.256) (Supplementary Table S9). We also conducted permutation test to assess the sensitivity of meta-regression, and the permutation test was well aligned with results of meta-regression (Supplementary Table S9), showing the reliability of meta-regression results.

3.5. Geological distribution of VAD risk and reported VAS efficacy

The prevalence of VAD areas involved in this study were mainly distributed in South Africa and South Asia (Fig. 8a). The areas with high (> 15%) and medium (10-15%) effectiveness of VAS during pregnancy in reducing preterm/LBW risks were not aligned with countries with high (> 20%), medium (2 – 20%) or low risks (< 2%) of VAD respectively (P = 0.296, supplementary Fig. S4), showing VAS during pregnancy could be an effective strategy to prevent preterm and LBW risks, regardless of VAD status (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

Geographic map shows the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency (VAD) (a), and efficacy of vitamin A supplementation during pregnancy on preterm and low birth weight outcomes by meta-analysis (b). VAD = vitamin A deficiency; NA = not available.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of evidence

Vitamin A plays an indispensable role in driving the development and functions of ocular, bone, mucosal, reproductive and immune tissues / organs, and adequate intake is required for both maternal and fetal health (Takahashi et al. 1975; Rees 1998; Matthews et al. 2004). However, in less developed areas or countries, a limited access to vitamin A rich foods can notably expose fetuses to VAD. VAD during pregnancy not only compromises fetal growth and birth outcomes, but also contributes to reshaping long-term health conditions of children, such as night blindness, obesity and type 2 diabetes (Lelièvre-Pégorier et al. 1998; Ralitza Gavrilova et al. 2009). Despite benefits of VAS during pregnancy in improving maternal health which have been well recorded in meta-analysis, meta-analyses on the effectiveness of VAS in fetal and child growth outcomes are largely missing. This meta-analysis of 55 relevant studies, including maternal VAS intervention (294,204) and placebo (131,894), showed that vitamin A only and vitamin A + co-intervention can effectively decrease the risks of preterm birth and LBW (Fig. 2), and VAS can also increase neonatal body weight and length. In both human and mouse studies, VAS promotes placental angiogenesis, oxygen and nutrient delivering to fetuses, which may improve fetal development and child health in early life (Wang et al. 2017; Thoene et al. 2020; Neves et al. 2020). When VAS dose was up to 4000 mcg RAE/d, meta-regression did not show any side effects on outcomes, revealing the safety and effectiveness of maternal VAS in improving fetal and neonatal health growth.

Globally, approximate 15 million births are preterm delivering, which substantially increases risks of neonatal and infant mortality and morbidly (Wen et al. 2004; Beck et al. 2010). Besides, preterm also increases risks of fetal health complications extending to childhood and adult life, including delayed locomotion skills, learning problems, respiratory issues, cardiovascular diseases and hypertension (Beck et al. 2010; Hoffman, Reynolds, and Hardy 2017). By compiling a large quantity of available data, this meta-analysis showed that VAS in MH decreases the risk of preterm birth by more than 9%, and VAS in MC reduces the risk of preterm birth by 10%, showing maternal VAS during pregnancy could effectively reduce the risk of preterm birth. Even the supplementation dose up to 4000 mcg RAE/d, it remains safe and effective with no reported complications, highly aligned with the 3000 mcg RAE/d upper level dose recommended by WHO for pregnant women (McGuire 2012).

Besides preterm birth, LBW is another major public concern which is associated with high incidences of neonatal and child mortality and morbidity (Blencowe et al. 2019; He et al. 2018), accounting for more than 19% of live births in less developed counties (Ratnasiri et al. 2018). LBW babies can also have high risks of health complications in later life, including cardiovascular diseases, bone malfunctions, hypertension and T2D (Ratnasiri et al. 2018), thus it is critical to reduce risks of LBW. This meta-analysis showed that maternal VAS during pregnancy effectively decreases the risk of LBW by over 16%. Considering disproportional distribution of VAD to low incoming families and areas, this meta-analysis also showed that the major VAD areas are concentrated in South African and South Asia. However, the reported effectiveness is not correlated with the degree of VAD. For instances, reported data suggested the high effectiveness of VAS in improving neonatal outcomes in England, France and Japan, where no VAD exists. These data show that the effectiveness of VAS is not only limited to alleviating risks of preterm and LBW in areas with endemic VAD, but can improve neonatal outcomes regardless of vitamin A status, underscoring the importance of vitamin A intake during pregnancy in improving fetal growth and birth outcomes.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of maternal vitamin A intervention, including vitamin A only and vitamin A + co-intervention, in MH and MC on fetal growth and birth outcomes. This analysis compiled available data from interventional and observational trials in recent decades to increase the power of conclusions. Publication bias was estimated by Rob2 and ROBINS. GRADE method was used to analyze result sensitivity, showing a high data reliability. However, a limitation of this meta-analysis is an existence of heterogeneity in VAS intervention among studies, such as varied vitamin A type, intervention intensity and duration. The findings of this work indicate high levels of heterogeneity and results should be treated with caution. Similarly, because of the small number of studies obtained, the subgroup analysis results should be treated with caution. The data on the programming effects of maternal VAS on childhood outcomes are extremely rare, limiting the ability to fully assess long-term benefits. Other co-mingled factors during interventions, such as smoking, alcohol drinking and other life behaviors, might contribute to data variations.

4.3. Future Directions

Due to limited data in investigating long-term effects of maternal VAS on childhood health outcomes, more follow-up studies are urgently required to narrow this knowledge gap. Besides, the dose range of VAS was narrow among and within studies, which prevents meta-regression to reveal an optimal VAS dose in benefiting neonatal and childhood outcomes, thus an increased dose range during VAS intervention may be recommended.

5. Conclusions

This meta-analysis shows that VAS during pregnancy effectively decreases the risks of abnormal fetal growth and birth outcomes, including the risks of preterm birth (overall decrease by 19%), LBW (overall decrease by 16%), and anemia (overall decrease by 20%), and increases neonatal body weight and length. Maternal VAS did not affect neonatal mortality, total defects, and child body weight. VAS dose up to 4000 mcg RAE/d, no negative effects was observed. Overall, our data show that maternal VAS during pregnancy is a safe and effective intervention to reduce adverse fetal growth and birth outcomes, even in mothers with no VAD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to Gengping Zhu (Department of Entomology, Washington State University), who helped us in the QGIS map development.

The authors’ responsibilities were as below: MD designed the research, contributed greatly to data interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. GLM and YTC conducted the research, screened the references, extracted the data, analyzed the data, wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and revised the final manuscript. XDL extracted the data, helped in data interpretation, and played critical role in revising the final manuscript. YG, JMD and MJZ contributed greatly to analyze data and revise the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding:

This study was funded by NIH R01 HD067449.

Sources of support for the work

No supporting source involvement or restrictions regarding publication.

List of abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- ES

Effect size

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- LBW

Low birth weight

- MH

Maternal healthy mothers

- MC

Mothers with complications

- OS

Observational studies

- PROSPERO

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- PICOS

Population; Intervention; Comparison; Outcome; Study design

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- RR

Risk ratio

- RAE

Retinol Activity Equivalents

- RoB 2

Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials

- ROBINS-I

The risk of bias in non-randomized studies – of interventions assessment tool

- SMD

Standard mean difference

- USDA

U.S. Department of Agriculture

- VAS

Vitamin A supplementation

- VAD

Vitamin A deficiency

- WHO

World health organization

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to this meta-analysis.

Data Share Statement: Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application and approval.

References

- Balshem Howard, Helfand Mark, Schünemann Holger J., Oxman Andrew D., Kunz Regina, Brozek Jan, Vist Gunn E., et al. 2011. ‘GRADE Guidelines: 3. Rating the Quality of Evidence’. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64 (4): 401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck Stacy, Wojdyla Daniel, Say Lale, Betran Ana Pilar, Merialdi Mario, Requejo Jennifer Harris, Rubens Craig, Menon Ramkumar, and Van Look Paul F.A.. 2010. ‘The Worldwide Incidence of Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review of Maternal Mortality and Morbidity’. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 88 (1): 31–38. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.062554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe Hannah, Krasevec Julia, de Onis Mercedes, Black Robert E., An Xiaoyi, Stevens Gretchen A., Borghi Elaine, et al. 2019. ‘National, Regional, and Worldwide Estimates of Low Birthweight in 2015, with Trends from 2000: A Systematic Analysis’. The Lancet Global Health 7 (7). UNICEF and World Health Organization. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license: e849–e860. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30565-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagas Cristiane Barbosa, Saunders Cláudia, Pereira Silvia, Silva Jacqueline, Saboya Carlos, and Ramalho Andréa. 2013. ‘Vitamin A Deficiency in Pregnancy: Perspectives after BARIATRIC SURGERY’. Obesity Surgery 23 (2): 249–254. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0822-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Jun, Chen Jiaming, Zhang Yinzhi, Lv Yantao, Qiao Hanzhen, Tian Min, Cheng Lin, Chen Fang, Zhang Shihai, and Guan Wutai. 2021. ‘Effects of Maternal Supplementation with Fully Oxidised β-Carotene on the Reproductive Performance and Immune Response of Sows, as Well as the Growth Performance of Nursing Piglets’. British Journal of Nutrition 125 (1): 62–70. doi: 10.1017/S0007114520002652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Yan-Ting, Yang Qi-Yuan, Hu Yun, Liu Xiang-Dong, De Avila Jeanene M., Zhu Mei-Jun, Nathanielsz Peter W., and Du Min. 2021. ‘Imprinted IncRNA Dio3os Preprograms Intergenerational Brown Fat Development and Obesity Resistance’. Nature Communications 12 (6845). Springer US: 1–19. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Yanting, Ma Guiling, Hu Yun, Yang Qiyuan, Deavila Jeanene M., Zhu Mei Jun, and Du Min. 2021. ‘Effects of Maternal Exercise During Pregnancy on Perinatal Growth and Childhood Obesity Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression’. Sports Medicine June (18). Springer International Publishing: 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s40279-021-01499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ‘Children in the World. The Global Children’s Right Situation, by Country. Https://Www.Humanium.Org/En/Children-World/. Accessed August 27, 2021.’

- Crippa Alessio, and Orsini Nicola. 2016. ‘Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Differences in Means’. BMC Medical Research Methodology 16 (1). BMC Medical Research Methodology: 91–100. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0189-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawzi Wafaie W., Msamanga Gernard I., Spiegelman Donna, Urassa Ernest J.N., McGrath Nuala, Mwakagile Davis, Antelman Gretchen, et al. 1998. ‘Randomised Trial of Effects of Vitamin Supplements on Pregnancy Outcomes and T Cell Counts in HIV-1-Infected Women in Tanzania’. Lancet 351 (9114): 1477–1482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04197-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland Sander, and Longnecker Matthew P.. 1992. ‘Methods for Trend Estimation from Summarized Dose-Response Data, with Applications to Meta-Analysis.’ American Journal of Epidemiology 135: 1301–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt Gordon H, Oxman Andrew D, Vist Gunn, Kunz Regina, Brozek Jan, Alonso-coello Pablo, Montori Victor, et al. 2011. ‘GRADE Guidelines: 4. Rating the Quality of Evidenced Study Limitations (Risk of Bias)’. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64: 407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbord Roger M., Egger Matthias, and Sterne Jonathan A. C.. 2006. ‘A Modified Test for Small-Study Effects in Meta-Analyses of Controlled Trials with Binary Endpoints’. Statistics in Medicine 25 (December): 3443–3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Zhifei, Bishwajit Ghose, Yaya Sanni, Cheng Zhaohui, Zou Dongsheng, and Zhou Yan. 2018. ‘Prevalence of Low Birth Weight and Its Association with Maternal Body Weight Status in Selected Countries in Africa: A Cross-Sectional Study’. BMJ Open 8 (8): 1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins Julian P. T., and Thompson Simon G.. 2002. ‘Quantifying Heterogeneity in a Meta-Analysis’. Statistics in Medicine 21 (11): 1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins Julian P T, Thompson Simon G, Deeks Jonathan J, and Altman Douglas G. 2003. ‘Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses.’ BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 327 (7414). BMJ Publishing Group: 557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman Daniel J., Reynolds Rebecca M., and Hardy Daniel B.. 2017. ‘Developmental Origins of Health and Disease: Current Knowledge and Potential Mechanisms’. Nutrition Reviews 75 (12): 951–970. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nux053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta Sergio, Rogers Lisa M., Li Zhaoping, Heber David, Liu Carson, and Livingston Edward H.. 2002. ‘Vitamin a Deficiency in a Newborn Resulting from Maternal Hypovitaminosis A after Biliopancreatic Diversion for the Treatment of Morbid Obesity’. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 76 (2): 426–429. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Id Anil K C, Basel Prem Lal, and Singh Sarswoti. 2020. ‘Low Birth Weight and Its Associated Risk Factors: Health Facility-Based Case-Control Study’. Plos One 15 (6): 1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis John P.A., Patsopoulos Nikolaos A., and Evangelou Evangelos. 2007. ‘Uncertainty in Heterogeneity Estimates in Meta-Analyses’. British Medical Journal 335 (7626): 914–916. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39343.408449.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West Keith P, Katz Joanne, Khatry Subarna K, Leclerq Steven C, Pradhan Elizabeth K, Sharada R, Connor Paul B, et al. 1999. ‘Double Blind, Cluster Randomised Trial of Low Dose Supplementation with Vitamin A or β Carotene on Mortality Related to Pregnancy in Nepal’. BMJ 318 (February): 570–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp Guido, and Hartung Joachim. 2003. ‘Improved Tests for a Random Effects Meta-Regression with a Single Covariate’. Statistics in Medicine 22 (17): 2693–2710. doi: 10.1002/sim.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langan Dean, Higgins Julian P.T., Jackson Dan, Bowden Jack, Veroniki Areti Angeliki, Kontopantelis Evangelos, Viechtbauer Wolfgang, and Simmonds Mark. 2019. ‘A Comparison of Heterogeneity Variance Estimators in Simulated Random-Effects Meta-Analyses’. Research Synthesis Methods 10 (1): 83–98. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelièvre-Pégorier Martine, Vilar José, Ferrier Marie Laure, Moreau Evelyne, Freund Nicole, Gilbert Thierry, and Merlet-Bénichou Claudie. 1998. ‘Mild Vitamin A Deficiency Leads to Inborn Nephron Deficit in the Rat’. Kidney International 54 (5): 1455–1462. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati Alessandro, Altman Douglas G., Tetzlaff Jennifer, Mulrow Cynthia, Gøtzsche Peter C., Ioannidis John P.A., Clarke Mike, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen Jos, and Moher David. 2009. ‘The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration’. Ann Intern Med 151 (4): w-65–w-94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G, and Chen Y. 2020. ‘Polyphenol Supplementation Benefits Human Health via Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review via Meta-Analysis’. Journal of Functional Foods 66. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.103829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Guiling, Chen Yanting, and Ndegwa Pius. 2021. ‘Association between Methane Yield and Microbiota Abundance in the Anaerobic Digestion Process: A Meta-Regression’. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 135 (March 2020): 110212. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2020.110212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Guiling, Chen Yanting, and Ndegwa Pius. 2022. ‘Anaerobic Digestion Process Deactivates Major Pathogens in Biowaste: A Meta-Analysis’. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 153 (September 2021). Elsevier Ltd: 111752. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.111752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maia Sabina Bastos, Souza Alex Sandro Rolland, De Fátima Costa Caminha Maria, da Silva Suzana Lins, de Sá Barreto Luna Callou Cruz Rachel, Dos Santos Camila Carvalho, and Filho Malaquias Batista. 2019. ‘Vitamin a and Pregnancy: A Narrative Review’. Nutrients 11 (3): 1–18. doi: 10.3390/nu11030681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maternal, Pregnancy, Child Health, Oh Christina, and Keats Emily C. 2020. ‘Vitamin and Mineral Supplementation During Pregnancy on Maternal, Birth, Child Health and Development Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’. Nutrients 12 (2): 491–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews Kimberly A., Rhoten William B., Driscoll Henry K., and Chertow Bruce S.. 2004. ‘Vitamin A Deficiency Impairs Fetal Islet Development and Causes Subsequent Glucose Intolerance in Adult Rats’. Journal of Nutrition 134 (8): 1958–1963. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.8.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness LA, and Higgins JPT. 2020. ‘Risk-of-Bias VISualization (Robvis): An R Package and Shiny Web App for Visualizing Risk-of-Bias Assessments’. Res Syn Meth 4 (1): 1–7. 10.1002/jrsm.1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire Shelley. 2012. ‘WHO Guideline: Vitamin A Supplementation in Pregnant Women. Geneva: WHO, 2011; WHO Guideline: Vitamin A Supplementation in Postpartum Women. Geneva: WHO, 2011’. Advances in Nutrition 3 (2): 215–216. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves Paulo A R, Castro Marcia C, Oliveira Clariana V R, and Lourenço Bárbara H. 2020. ‘Effect of Vitamin A Status during Pregnancy on Maternal Anemia and Newborn Birth Weight: Results from a Cohort Study in the Western Brazilian Amazon’. European Journal of Nutrition 59 (1). Springer Berlin Heidelberg: 45–56. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good Phillip I.. 1992. ‘Permutation Tests : A Practical Guide to Resampling Methods for Testing Hypotheses. New York: : Springer-Verlag’, g. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ‘QGIS Development Team (2021). QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. Http://Qgis.Osgeo.Org’. [Google Scholar]

- Radhika MS, Bhaskaram P, Balakrishna N, Ramalakshmi BA, Devi Savitha, and Siva Kumar B. 2002. ‘Effects of Vitamin A Deficiency during Pregnancy on Maternal and Child Health’. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 109 (6): 689–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilova Ralitza, Babovic Nikola, Lteif Aida, Eidem Benjamin, Kirmani Salman, Olson Timothy, and Babovic-Vuksanovic Dusica. 2009. ‘Vitamin A Deficiency in an Infant with PAGOD Syndrome’. Am J Med Genet Part A 149A (10): 2241–2247. doi: 10.1016/j.clnme.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnasiri Anura W. G., Parry Steven S., Arief Vivi N., DeLacy Ian H., Halliday Laura A., DiLibero Ralph J., and Basford Kaye E.. 2018. ‘Recent Trends, Risk Factors, and Disparities in Low Birth Weight in California, 2005–2014: A Retrospective Study’. Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology 4 (1). Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology: 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40748-018-0084-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees WD 1998. ‘Effects of Maternal Vitamin A Status on Fetal Heart and Lung: Changes in Expression of Key Developmental Genes’. American Journal of Physiology 275 (6 PART 1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rücker Gerta, Schwarzer Guido, Carpenter James, and Olkin Ingram. 2009. ‘Why Add Anything to Nothing ? The Arcsine Difference as a Measure of Treatment Effect in Meta-Analysis with Zero Cells’. Statistics in Medicine 28 (October): 721–738. doi: 10.1002/sim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Screening, Cell-free D N A, and Fetal Aneuploidy. 2015. ‘ACOG Committee Opinion No. 650: Physical Activity and Exercise during Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period.’ The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 126 (640): 691–692. doi: 10.1016/j.yqres.2004.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Mark F. 2020. ‘Systematic Review Research Strategy’. Research Methods in Sport 0 (version 1.0): 43–62. doi: 10.4135/9781526433992.n3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer Alfred. 2008. ‘Vitamin A Deficiency and Clinical Disease: An Historical Overview’. Journal of Nutrition 138 (10): 1835–1839. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.10.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens Gretchen A., Bennett James E., Hennocq Quentin, Lu Yuan, Luz Maria De-Regil Lisa Rogers, Danaei Goodarz, et al. 2015. ‘Trends and Mortality Effects of Vitamin A Deficiency in Children in 138 Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries between 1991 and 2013: A Pooled Analysis of Population-Based Surveys’. The Lancet Global Health 3 (9): e528–e536. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00039-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi YI, Smith JE, Winick M, and Goodman DS. 1975. ‘Vitamin A Deficiency and Fetal Growth and Development in the Rat’. Journal of Nutrition 105 (10): 1299–1310. doi: 10.1093/jn/105.10.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team, R Core. 2021. ‘R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.’ https://www.r-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- ‘The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Child Population by Age Group in the United States. Https://Datacenter.Kidscount.Org/Data/Tables/101-Child-Population-by-Age-Group#detailed/1/Any/False/1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133/62,63. Accessed September 5,2021.’

- Thoene Melissa, Haskett Haley, Furtado Jeremy, Thompson Maranda, Van Ormer Matthew, Hanson Corrine, and Anderson-berry Ann. 2020. ‘Effect of Maternal Retinol Status at Time of Term Delivery on Retinol Placental Concentration, Intrauterine Transfer Rate, and Newborn Retinol Status’. Biomedicines 8 (9): 321–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne-Lyman Andrew L., and Fawzi Wafaie W.. 2012. ‘Vitamin A and Carotenoids during Pregnancy and Maternal, Neonatal and Infant Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 26 (SUPPL. 1): 36–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF, WHO. Low Birth Weight: Country, Regional and Global Estimates. UNICEF, New York, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- USDA. 2017. Dietary Supplement Ingredient Database, August 14. [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer Wolfgang. 2010. ‘Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the Metafor Package’. Journal of Statistical Software 36 (3): 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v036.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walani Salimah R. 2020. ‘Global Burden of Preterm Birth’. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 150 (1): 31–33. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Bo, Fu Xing, Liang Xingwei, Wang Zhixiu, Yang Qiyuan, Zou Tiande, Nie Wei, et al. 2017. ‘EBioMedicine Maternal Retinoids Increase PDGFR α + Progenitor Population and Beige Adipogenesis in Progeny by Stimulating Vascular Development’. EBioMedicine 18. The Authors: 288–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, and et al. Losos M. 2014. Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale Cohort Studies. doi: 10.2307/632432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Shi Wu, Smith Graeme, Yang Qiuying, and Walker Mark. 2004. ‘Epidemiology of Preterm Birth and Neonatal Outcome’. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 9 (6): 429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ‘WHA Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Low Birth Weight Policy Brief. World Health Organization, 2014.’ [Google Scholar]

- ‘World Health Organization. Adolescent Pregnancy. Https://Www.Who.Int/News-Room/Fact-Sheets/Detail/Adolescent-Pregnancy. Accessed September 4, 2021’.

- World Health Organization. 2009. ‘Global Prevalence of Vitamin A Deficiency in Populations at Risk 1995–2005: WHO Global Database on Vitamin A Deficiency. Availanle Online: Https://Www.Google.Com/Url?Sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwi5i-VQ68ryAhU6FjQIHVAQB0IQFnoECAIQAQ&url=‘. http://apps.who.int//iris/handle/10665/44110.

- Zhang Yanqi, Crowe-White Kristi M., Kong Lingyan, and Tan Libo. 2020. ‘Vitamin a Status and Deposition in Neonatal and Weanling Rats Reared by Mothers Consuming Normal and High-Fat Diets with Adequate or Supplemented Vitamin A’. Nutrients 12 (5): 1–14. doi: 10.3390/nu12051460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Zhiying, Tran Nga T., Nguyen Tu S., Nguyen Lam T., Berde Yatin, Tey Siew Ling, Low Yen Ling, and Huynh Dieu T.T.. 2018. ‘Impact of Maternal Nutritional Supplementation in Conjunction with a Breastfeeding Support Program during the Last Trimester to 12 Weeks Postpartum on Breastfeeding Practices and Child Development at 30 Months Old’. PLoS ONE 13 (7): 1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.