Abstract

Background

Homeless and marginally housed (HAMH) individuals experience significant health disparities compared to housed counterparts, including higher hepatitis C virus (HCV) rates. New direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medications dramatically increased screening and treatment rates for HCV overall, but inequities persist for HAMH populations.

Objective

This study examines the range of policies, practices, adaptations, and innovations implemented by Veteran Affairs Medical Centers (VAMCs) in response to Veterans Health Administration (VHA)’s 2016 HCV funding allocation to expand provision of HCV care.

Design

Ethnographic site visits to six US VAMCs varying in size, location, and availability of Homeless Patient-Aligned Care Teams. Semi-structured qualitative interviews informed by the HCV care continuum were conducted with providers, staff, and HAMH patients to elicit experiences providing and receiving HCV care. Semi-structured field note templates captured clinical care observations. Interview and observation data were analyzed to identify cross-cutting themes and strategies supporting tailored HCV care for HAMH patients.

Participants

Fifty-six providers and staff working in HCV and/or homelessness care (e.g., infectious disease providers, primary care providers, social workers). Twenty-five patients with varying homeless experiences, including currently, formerly, or at risk of homelessness (n=20) and stably housed (n=5).

Key Results

All sites experienced challenges with continued engagement of HAMH individuals in HCV care, which led to the implementation of targeted care strategies to better meet their needs. Across sites, we identified 35 unique strategies used to find, engage, and retain HAMH individuals in HCV care.

Conclusions

Despite highly effective, widely available HCV treatments, HAMH individuals continue to experience challenges accessing HCV care. VHA’s 2016 HCV funding allocation resulted in rapid adoption of strategies to engage and retain vulnerable patients in HCV treatment. The strategies identified here can help healthcare institutions tailor and target approaches to provide sustainable, high-quality, equitable care to HAMH individuals living with HCV and other chronic illnesses.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-07708-w.

KEY WORDS: Homelessness, Vulnerable patients, Hepatitis C, Veterans, Quality improvement

BACKGROUND

Homeless and marginally housed (HAMH) individuals experience significant health disparities compared to non-homeless counterparts. These include higher rates of infectious disease, mental illness, substance use disorders (SUD), and chronic illness.1

One infectious disease disproportionately impacting this population is hepatitis C virus (HCV).2 While HCV’s prevalence in the general US population is ~1%, its prevalence among homeless individuals is 18–48%.3 When left untreated, HCV can progress to cirrhosis, chronic liver disease, liver failure, cancer, and death.4,5

Historically, HCV treatment involved intensive oral, subcutaneous, and intramuscular interferon-based medication regimens with severe side effects and low cures rates.6–8 The 2013 development of oral direct-acting antiviral medications (DAAs) transformed the landscape of HCV care—DAAs have minimal side effects and cure rates >90%.9–11 Following DAA introduction, rates of HCV screening and treatment skyrocketed nationwide.12

Despite these benefits, new DAA treatments are not without challenges. DAAs are expensive (up to $84,000 per course13) and have stringent adherence requirements that include 8–16 weeks of daily oral medications; frequent check-in appointments with specialty care providers; lab tests and liver scans before, during, and after treatment; and precautions to minimize potential drug-drug interactions.14–16 HAMH individuals and individuals living with mental illness or SUD, including those who use intravenous drugs and are thus at even greater risk of HCV infection,17 are most likely to remain untreated; many consider these groups unable to fulfill treatment requirements. This concern is not unfounded—HAMH individuals experience many well-documented barriers to HCV care completion, including competing priorities, limited social support, low HCV knowledge, communication and transportation challenges, limited access to food, and general instability of life circumstances.18–22 They may also avoid care due to perceived stigma associated with HCV, homelessness, and substance use.23–26 However, with proper supports, HAMH individuals are able to initiate and complete HCV treatment at rates comparable to housed populations.27–29

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system provides an ideal setting within which to study HCV care among HAMH individuals. The VA is the largest single provider of HCV care in the USA.12 HCV disproportionately affects veterans at a prevalence of ~6%.12 HAMH veterans are particularly impacted: one study found an HCV prevalence of 12.1% among homeless veterans, compared to 2.7% among non-homeless veterans.30 Though the VA is national in scope, each VA Medical Center (VAMC) faces unique contextual challenges driven by differences in size, resources, location, and patient population. For this reason, VAMCs have discretion in how they utilize available resources to meet care objectives, including allocation of budget, staff, and clinical initiatives.

Late in fiscal year 2016, the VA received and invested $1.5 billion in funding to provide DAAs to all veterans living with HCV, divided among VAMCs with substantial numbers of HCV+ veterans.31,32 The relatively short timeframe for spending these funds presented each VAMC with a unique challenge: develop strategies to find, screen, treat, and cure as many HCV+ veterans as possible, including HAMH veterans and other groups previously considered ineligible for DAA-based HCV treatment. Thus, funding presented VAMCs with the opportunity to develop innovative approaches to treat HCV among HAMH populations. The purpose of this paper is to describe, catalog, and sort the innovative approaches in care provision for HAMH patients living with HCV that emerged from the massive effort to reach and treat nearly every veteran infected with HCV. Sharing these practices will provide healthcare organizations with novel strategies to adopt or expand in their own settings to better support and provide care for highly vulnerable and hard to reach populations, whether for HCV, other chronic conditions, or general health maintenance.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a qualitative study of a sample of US VAMCs. During ethnographic site visits, we interviewed HCV care providers, homelessness care providers, and patients. We also completed observations of clinical encounters, hospital layouts, and the availability of HCV and homelessness-related support programs and materials.

Recruitment: Sites

We utilized a two-step screening process for site selection that enhanced representation of sites with variety of characteristics (see below) while maintaining data collection feasibility.

First, we conducted a risk-adjusted analysis33,34 (detailed in our prior work35) categorizing 128 VAMCs nationwide by HCV+ patient population size (small/medium/large), geographic region (south/west/midwest/northeast), rurality (urban/rural), and on-site presence of Homeless Patient-Aligned Care Teams (HPACTs) (yes/no). VA’s HPACT clinics co-locate medical providers, social workers, mental health and substance use counseling, and homeless services to provide comprehensive care to HAMH patients. HPACT presence was included in site selection analysis metrics due to the specialized knowledge and experience of HPACT providers in providing care to HAMH individuals, and the potential to identify unique HCV care practices that grew from this knowledge. Following analysis, we identified a purposive sample of 21 facilities representing variation across these categories.

Second, we conducted brief structured phone screenings with HCV clinical leads at each of these facilities to better understand HCV care structures and strategies used to reach HAMH patients (see Appendix A). Our research team then convened together to review findings from these screening calls and identify six site visit locations. We chose sites we perceived to be utilizing unique approaches for treating HCV broadly, and/or were utilizing tailored approaches for treating HCV specifically among HAMH populations compared to sites that were not chosen, as researchers felt these sites would provide the largest breadth of innovative strategies that other clinics might be able to utilize. The final list of six sites preserved the variation in size, geographic location, rurality, and HPACT availability described above.

Recruitment: Providers and Patients

We identified provider participants through each site’s HCV clinical lead, staff directory, and/or recommendations from other participants. Eligible providers needed to be familiar with HCV and/or homelessness care at their VA. Provider types included doctors (MDs), registered nurses (RNs), physician assistants (PAs), nurse practitioners (NPs), clinical pharmacists, case managers, and social workers in Infectious Disease, Gastroenterology, and Primary Care departments, as well as in any on-site housing and substance use programs. The exact number, type, and location of available providers for recruitment varied due to site differences in size and organizational structures.

We identified patient participants through each site’s HCV clinical lead. From each site, we requested a list of patients receiving HCV care within 6–12 months of our visit. We asked sites to oversample HAMH patients and prioritized these patients for recruitment, but did not restrict recruitment to HAMH individuals to ensure we captured a range of HCV care experiences and reached an appropriate sample size. Prior to interviews, all participants were additionally asked two questions from VA’s Universal Screener to Identify Veterans Experiencing Homelessness36 to confirm their housing status: (1) “In the past two months, have you been living in stable housing that you own, rent, or stay in as part of a household?” (No indicates homelessness), and (2) “Are you worried or concerned that in the next two months you may NOT have stable housing that you own, rent, or stay in as part of a household?” (Yes indicates homelessness risk).

Data Collection

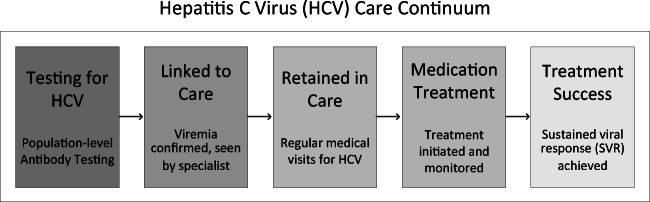

Experienced qualitative researchers performed semi-structured interviews with providers and patients from each site, in person or via phone. Interview guides were guided by the HCV care continuum, a well-studied population health model of HCV care (see Fig. 1).6,37 This continuum highlights the successive stages of HCV care that individuals must progress through in order to complete HCV treatment; utilizing it to guide interview questions ensured comprehensive exploration of strategies and experiences participants implemented or experienced across the full range of HCV care stages. Interview guides were also tailored to specific participant groups: provider-specific interview guides (including ones for specialty care HCV providers, clinical pharmacists, care coordinators, and primary care/HPACT providers) included questions exploring facilitators and barriers to care delivery, treatment eligibility requirements, and changes in HCV care for HAMH patients over time (see Appendix B), while the patient-specific guide included questions about perceptions of HCV treatment, quality of care received, and the influence of housing status on HCV care (see Appendix C). Patient interviews concluded a structured demographic questionnaire. Interviews were audio recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim.

Fig. 1.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) care continuum, adapted from Maier et al., 2016 and Yehia et al., 2014. Arrows illustrate standard progression through the continuum. Shading illustrates the observed drop in number of individuals who successfully progress through each stage.

Semi-structured field note templates captured direct and indirect observations of clinical care. Direct observations consisted of appointment shadows in which a researcher sat in and observed HCV care appointments with patient consent. Indirect observations consisted of descriptions of clinic layouts, notes from ad hoc conversations with clinic staff, and the visibility of HCV and/or homelessness-related materials or services on site.

Data Analysis

Demographic data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Transcripts and field notes were imported into NVivo software38 and analyzed using a framework approach.39 Four team members (SD, JC, ED, KM) first familiarized themselves with a subset of transcripts and field notes, and developed a thematic framework (i.e., a codebook) of a priori and emergent themes. Three coders (JC, SD, ED) then applied the codebook to the same subset of transcripts and modified codes based on their joint experiences, continuing the process with additional transcripts until consensus was reached (see Appendix D). Coders then independently coded remaining transcripts, meeting regularly to resolve issues and maintain consensus.

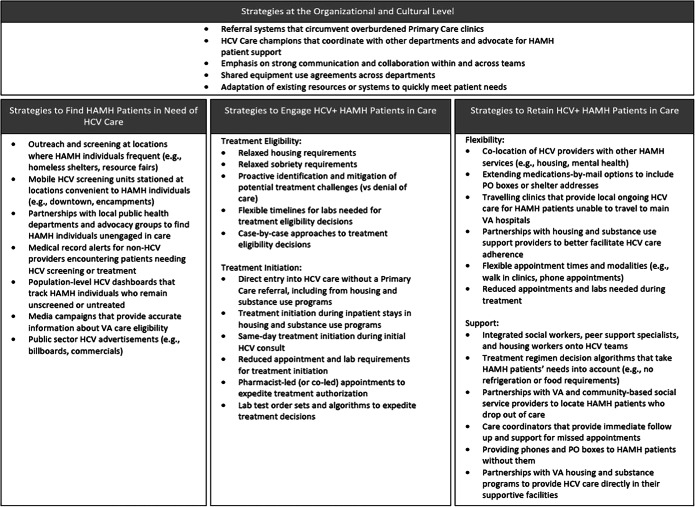

Following coding completion, coders performed systematic comparisons of text segments within key codes of interest to identify and chart salient themes by site. Coders created summary documents for each site that considered the following categories: care organization at that site, perceived facilitators and barriers to HCV and/or HAMH care, specific care strategies utilized for HCV+ HAMH patients, and recommendations for future HCV and/or HAMH care. Organizing the data first by site helped identify findings specific to particular site contexts. Coders then looked across sites to identify cross-cutting themes and key strategies for HAMH HCV+ care, situating them within an adapted HCV care continuum model that included simplified care categories and an additional organizational element (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Adapted Hepatitis C virus (HCV) care continuum for homeless and marginally housed (HAMH) individuals, adapted from Maier et al., 2016 and Yehia et al., 2014.

RESULTS

Participants

We conducted 6 site visits between March 2019 and August 2019. Across sites, we interviewed 56 providers and staff (e.g., MDs, PCPs, RNs, social workers) and 25 patients. Patients were classified as follows: (1) currently, formerly, or at risk of homelessness (n=20), or (2) stably housed/housing status unknown (n=5), as determined by responses to VA’s Universal Screener to Identify Veterans Experiencing Homelessness (see “Methods” section). One site (site 5) was unable to provide patient lists during the study period due to staffing issues. Additionally, we completed 16 patient appointment shadows (see Table 1 for a detailed overview).

Table 1.

Site and Participant Characteristics

| Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5‖ | Site 6 | 6 | |

| Facility size* | Medium | Medium | Large | Small | Small | Large | |

| Geographic region | South | West | Midwest | Midwest | West | West | |

| Urban/rural | Rural | Urban | Urban | Rural | Rural | Urban | |

| HPACT† | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Providers interviews‡ | 8 | 13 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 13 | 56 |

| Infectious disease MD, NP, PA | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | |||

| Gastroenterology MD, NP, PA | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | ||

| Hepatology MD, NP, PA | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| HPACT or recovery MD, NP | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Registered nurse | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Primary care MD, NP, PA | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| Pharmacist or pharmacy tech | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| Social worker | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 10 | |

| Other Clinical Worker (e.g., clinic manager | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||

| Other housing support worker | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Patient interviews | 10 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 25 |

| Unstably housed | 6 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 20 | |

| Housed or unknown | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| Patient clinical care encounters§ | 3 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 16 |

| Unstably housed | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Housed or unknown | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 11 | |

*Size determined by known 2012–2016 site HCV+ patient population (small <500, medium 500–999, large >1000)

†“HPACT” refers to Homeless Patient-Aligned Care Team

‡Providers and staff types dependent on types of position present at each site

§Encounters dependent on number of patients with appointments during site visits

‖Site 5 was unable to provide full patients lists during the interview period due to staffing shortages

Below we detail observed policies, practices, adaptations, and innovations at different stages of HCV care, organized by an adapted HCV care continuum model (see Fig. 2). This adapted model simplifies the original HCV care continuum “stages” to better reflect the broader care delivery needs and goals of providers caring for HAMH patients, while still preserving the unique nature of different care stages. Our adapted HCV care continuum model maps on to the traditional care continuum as follows:

Finding HAMH patients in need of HCV care (e.g., outreach, screening)

Engaging HAMH patients in care (e.g., linkage to care, treatment initiation)

Retaining HAMH patients in care (e.g., treatment support, completion)

Combating organizational challenges to care provision (an added element in our modified model that spans across all stages of care)

Given our focus on identifying care strategies, our results draw primarily on provider interviews and observational field notes. Patients provided more general perspectives on HCV and VA care experiences, including experiences with stigma (a known care barrier for HAMH populations).

Finding HAMH Patients in Need of HCV Care

During interviews, providers frequently described challenges finding HAMH populations with typical outreach and screening methods. They described these patients as “hard to reach,” “high hanging fruit,” or in need of unique strategies to find and connect them with care. As one provider noted, “…the biggest point is just some of these patients, we can’t even find them.” (Pharmacist, site 2)

Across sites, we identified seven unique strategies used to find HAMH veterans in need of HCV care (see Table 2 for complete list). These strategies often involved bringing information and screening tools directly to locations that HAMH patients frequent, such as homeless shelters, encampments, or resource fairs. At sites where HCV teams were spread thin, providers and staff enlisted the help of local public health and police departments to expand their reach by identifying and visiting locations where homeless individuals frequently congregated.

Table 2.

Strategies to Support Homeless and Marginally Housed (HAMH) Patients Through Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Care

To address the identified issue of HAMH patients believing they are ineligible for VA care, some efforts—including public sector HCV care advertisements through billboards and commercials—specifically targeted patients outside of VA. Some sites coupled these advertisements with education campaigns dispelling myths about care eligibility for veterans experiencing homelessness.

Finally, care teams often made use of relationships with providers in other departments to “catch” patients in need of HCV screening when they came in for routine care. As one provider described, “[If]I knew there was an appointment coming up, and this was a hard to reach or homeless vet, then I would contact the social worker and say… is there a way that you can contact this patient to let them know that [screening] needs to be done?” (Nurse Care Manager, site 6)

-

2.

Engaging HAMH Patients in HCV Care

Once HCV+ patients are found, they must be engaged in HCV care through treatment initiation. We identified 11 strategies sites used to increase the likelihood of HAMH care engagement (see Table 2). These strategies fell into the following categories: (1) expanding treatment eligibility criteria and (2) streamlining treatment initiation processes.

(2a) Expanding Treatment Eligibility Criteria

All participating sites described expanding their HCV care eligibility criteria to include HAMH patients and patients actively using drugs or alcohol, in contrast with prior policies that restricted treatment to stably housed and sober patients.40

Some sites complemented their expanded eligibility criteria with a shared commitment to proactive patient support via phone calls and support service connections. As one team lead described: “[B]efore the decision was, is this a candidate for therapy? Meaning does this patient fit into my treatment box… did [they] check off all the criteria. That’s kind of morphed into, okay we have lots of therapies and resources available, which therapies and resources does this patient need for us to support him or her through therapy?” (MD, site 6)

Other sites utilized approaches to eligibility that reconciled their desire to bring treatment to HAMH patients with the realities of patient challenges and limited site supports: “I try to be aggressive and start [HAMH patients] as much as possible, but definitely if they have a history in their chart of a lot of no-shows, or the patient just doesn’t seem very motivated in the interview… It’s kind of like an on-the-fly judgment call…. We try our best.” (PA, site 5)

Of note, a site’s expanded treatment eligibility did not preclude the occasional individual provider imposing subjective treatment requirements for HAMH patients. This included unofficial waiting periods for treatment initiation (e.g., waiting until someone is stably housed) and waiting to start treatment until a patient “proved” reliability.

(2b) Streamlining Care Processes

Streamlining care processes during the initiation stage helped minimize the burden of care engagement for HAMH patients and lowered the risk of losing them before treatment began. A key theme across these strategies was connecting patients to care as quickly as possible, including same day. At some sites, this meant limiting the lab and liver scan requirements needed for treatment starts, while at others it meant bypassing traditional referral and prescribing pathways from primary care clinics to expedite initiation. As one provider described, “I know it’s going to be done in a couple weeks, but the patient’s in front of me, so I’m going to start them on therapy while waiting for that imaging test.” (MD, site 6)

However, streamlining care processes was not without challenges. Rural sites with limited staff and technology, for example, described being dependent on outside hospitals for referrals and test results, which lengthened treatment initiation timelines. Similarly, sites with large patient queues described challenges balancing the need for timeliness with the realities of an overburdened, under-resourced system.

-

3.

Retaining HAMH Patients in Care

To reach the “cured” stage of the HCV care continuum, patients must complete a full course of medications and appointments over an 8- to 16-week period. We identified 12 strategies sites used to encourage retention in care (see Table 2). These strategies emphasized (1) providing flexible care options and (2) fostering supportive care environments.

(3a) Providing Flexible Care Options

Providers described care flexibility as critical for HAMH patients, as these patients frequently experience challenges with appointment attendance and competing life priorities. Specific strategies to enhance care flexibility often involved delivering care at locations more convenient for HAMH patients, and from providers they trusted. This was particularly valuable in smaller, more rural locations. As one rural provider described, “[I]f they're living at a shelter or if they have transportation issues, if they're living closer to the [local clinics] than they are to us, then we try to accommodate. Some of them… may have transportation issues, but they can get a ride to their local [VA clinic]. They can’t get a ride all the way two hours up here… [so the doctor] will send the medication by courier…” (Nurse, site 1)

Some sites even implemented walk-in and mobile HCV clinics to allow HAMH patients to drop in at times most convenient to them. Some of these clinics were located directly within housing and substance use treatment programs.

Interestingly, the availability of flexible care options at a site did not always mean those options were available to HAMH patients—provider preferences also played a role. For example, some providers specifically required HAMH patients to attend in-person appointments and pick up medications at their main VA hospital to ensure compliance, despite availability of telephone appointments, medications by mail, and local clinic alternatives.

(3b) Fostering Supportive Care Environments

Connecting HAMH patients to external support services was described as critical to their continued treatment engagement and cure. Strategies sites used to foster these environments frequently involved collaboration with individuals or teams with more specialized knowledge of HAMH patient needs. At some sites, teams had the capacity to integrate these individuals directly into their HCV care teams, while at others they collaborated with existing teams across department or community lines.

As with other steps along the continuum, sites made use of “captive audiences” living within housing and substance use programs affiliated with their clinics. This provided HAMH patients with built-in support staff and reduced the need to prioritize basic needs over treatment. Acknowledgment of these needs was also sometimes built directly into prescribing algorithms: “I’m committed to like, rescheduling them when there's no-shows …Try[ing] to use regimens that are shorter rather than longer… Try[ing] to integrate other care into their Hep C care.” (ID MD, site 2)

Provider and staff attempts to create supportive environments were reflected in patient experiences of care. HAMH patients frequently described HCV care teams as attentive, flexible, and non-stigmatizing, which at times contrasted with their opinions of other care they were receiving.

“In the [HCV] clinic, no I did not feel like I was unwelcome. In the VA, yes… I still have a problem with my primary. Like, I don’t like her at all. She's very judgmental, and she says all my problems have to do with my drug addiction, even though I’m clean now. And when I was homeless, she was even worse about it… in the actual like clinic, the hep C clinic and all that, they were really, they were just good to me all around. They were great people. They didn’t look at me… or judge me for that.” (Veteran, site 2)

-

4.

Combating Organizational Challenges to Care Provision

Successful care for HAMH populations depends not just on care strategies, but also on organizational structures and environments within which they operate. All sites experienced challenges that threatened their ability to provide the necessary care for HAMH patients to achieve HCV treatment success, including restricted staffing, resources, and referral systems, as well as barriers to collaboration with other departments or hospital leadership.

To adapt to these challenges, sites adopted a mix of official (e.g., policy) and unofficial (e.g., shared values) strategies (see Table 2 for complete list). For example, some sites adopted shared equipment purchase and use agreements with other departments that allowed them to provide services quickly and without navigating administrative “red tape.” Others utilized unofficial HCV care champions on their team to coordinate services and/or advocate for their HAMH patients: “…I think that’s one of the major perks … just have people who are just you know excited about treating Hep C...” (PA, site 3)

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study represents the first detailed inquiry, in the DAA era, of HCV care practices for vulnerable populations in a large integrated healthcare system. The 2016 congressional funding for HCV care within VA, and the time pressure to quickly utilize the funds, provided a unique opportunity to observe what rapid innovation looks like across a sample of VA healthcare facilities. Through the exploration of care practices in six facilities, we identified 35 unique strategies used to provide HCV care tailored to HAMH individuals, including seven strategies to find HAMH individuals in need of HCV, 11 to engage them in care, 12 to retain them in care, and five to address organizational care provision challenges. While many of these individual practices may already be in use in healthcare organizations in various ways, to our knowledge the full breadth of strategies has not be cataloged and summarized in one place.

We anticipate that providers and staff will be able to use our tabular presentation of care strategies, organized by stages of our modified HCV care continuum, to identify promising options for potential adoption at their own clinics. When doing so, it is important to consider the geographic and organizational context where the innovation would be implemented. For example, deploying mobile HCV testing units or offering HCV walk in clinics may work well at larger sites with significant clinical resources. However, smaller sites may benefit more from strategies that utilize existing or limited resources in new ways, such as pharmacist-led appointments and sharing of clinical staff or equipment across departments. Rural sites with limited homelessness services may benefit from public sector collaborations and media campaigns, while sites with robust homelessness services available on site or nearby are likely positioned well to offer HCV care in conjunction with these services. Finally, some approaches to care we anticipate will benefit a wide variety of facilities because they relate to broad policies and approaches to HAMH care, including care flexibility (e.g., available in multiple locations or timeframes), simplicity (e.g., limited required lab tests and appointments to streamline care), and enhanced support (e.g., collaborating social workers to better address HAMH patient needs). Care teams ultimately know the strengths, weaknesses, and available resources of their clinics best, and should evaluate the potential effectiveness of strategies presented here in relation their individual contexts.

While our major lessons are focused on care provision from providers, staff, and managers, it was encouraging to observe that patient participants did not feel stigmatized when receiving care from their HCV team. This contrasts both with their experiences in other clinics and with existing literature reports of the stigma experiences of homeless individuals41–43 and individuals living with HCV.44,45 Given that facility providers and staff rarely brought up stigma and did not identify stigma reduction as a key goal of HAMH-focused care strategies, it is possible that patients’ perceived lack of stigma is a result of staff’s understanding and willingness to tailor care services to better meet HAMH patient needs, contributing to a more welcoming environment for all patients.

Caring for HAMH patients requires an intentional, tailored approach,46 and our findings contribute action-oriented steps towards providing this kind of care across a variety of organizational contexts. Given that factors necessary for HCV care success (e.g., medication adherence, continued engagement, consistent communication) also apply to other chronic illnesses, the strategies documented above are relevant to a variety of conditions impacting HAMH populations. Our study’s emphasis on HAHM individuals was motivated by the knowledge that this population may be overlooked in large-scale health campaigns. When most of an affected population has been reached, there is a risk that resources will be shifted to other priorities before strategies have been implemented to reach homeless and other marginalized populations.

Limitations

Few healthcare facilities will experience the same financial advantages that VA HCV care teams did in 2016; thus, our findings may not apply to other hospitals or healthcare systems. Similarly, other aspects of the VA healthcare system not present elsewhere (e.g., national performance measures, unified electronic medical record systems, a veteran population, etc.) may have contributed to our findings. The organizational variation that was a key strength in identifying a wide variety of care strategies also posed a challenge for study recruitment: some facilities had complex research approval requirements that delayed patient recruitment. This resulted in two sites having few patient participants. The impact of this limited recruitment is likely minimal given that most findings stemmed from provider interviews.

Additionally, as a qualitative study, it is unknown if sites that implemented the strategies described here achieved higher rates of treatment of HAHM patients than sites that did not. Many of the strategies described here have demonstrated success in HCV and homeless populations,29,47 and with other health conditions like HIV48 and mental health disorders.28 The present study adds value to literature in aggregating and disseminating a number of empirically tested strategies for engaging HAMH individuals in care that can be further tailored and tested by healthcare institutions in their own settings.

Conclusion

The sharing of innovative practices can benefit hospital, department, and clinic leaders and frontline staff by helping them overcome the siloed information and experiences common in many healthcare organizations. Our findings give leaders, providers, and clinical staff an opportunity to review a wide range of strategies that address the needs of HAMH patients and adopt the ones that best fit their resources and organization of care. Use of these strategies has the potential to increase equitable access to care for individuals who are homeless or unstably housed, resulting in healthier communities.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 24 kb)

(DOCX 28 kb)

(DOCX 23 kb)

(DOCX 20 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank VA HSR&D Centralized Transcription Services in Salt Lake City, Utah for providing us with our interview transcriptions. We would also like to thank the veteran participants who shared their experiences navigating care with us.

Funding

Funding provided by the Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D), IIR 14-322 (PI McInnes).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approval

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Bedford VA IRB, located in Bedford, Massachusetts.

Disclaimer

The views in this paper are the views of the authors and do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1529–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beijer U, Wolf A, Fazel S. Prevalence of tuberculosis, hepatitis C virus, and HIV in homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(11):859–70. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70177-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strehlow AJ, et al. Hepatitis C among clients of health care for the homeless primary care clinics. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(2):811–33. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1118–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balakrishnan M, Kanwal F. The HCV treatment cascade: race is a factor to consider. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):1949–1951. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04962-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yehia BR, et al. The treatment cascade for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman K, Nathanson J. Interferon-based hepatitis C treatment in patients with pre-existing severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2009;7(3):363–76. doi: 10.1586/eri.09.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poynard T, et al. Viral hepatitis C. Lancet. 2003;362(9401):2095–100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gifford AL. Sutton's law, substance use disorder, and treatment of hepatitis C in the era of direct-acting antivirals. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(4):988–989. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05654-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawitz E, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1878–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gane EJ, et al. Efficacy of nucleotide polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir plus the NS5A inhibitor ledipasvir or the NS5B non-nucleoside inhibitor GS-9669 against HCV genotype 1 infection. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(3):736–743 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belperio PS, Fox RK, Backus LI. The State of Hepatitis C Care in the VA. Fed Pract. 2015;32(Suppl 2):20S–24S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill A, et al. Minimum costs for producing hepatitis C direct-acting antivirals for use in large-scale treatment access programs in developing countries. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(7):928–36. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spengler U. Direct antiviral agents (DAAs) - a new age in the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Pharmacol Therap. 2018;183:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandmann L, et al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C: efficacy, side effects and complications. Visc Med. 2019;35(3):161–170. doi: 10.1159/000500963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geddawy A, et al. Direct acting anti-hepatitis C virus drugs: clinical pharmacology and future direction. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5(1):8–17. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2017-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zibbell JE, et al. Increases in acute hepatitis C virus infection related to a growing opioid epidemic and associated injection drug use, United States, 2004 to 2014. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):175–181. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crowley D, et al. Competing priorities and second chances - a qualitative exploration of prisoners' journeys through the hepatitis C continuum of care. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherbuk JE, et al. Disparities in hepatitis C linkage to care in the direct acting antiviral era: findings from a referral clinic with an embedded nurse navigator model. Front Public Health. 2019;7:362. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falade-Nwulia O, et al. Public health clinic-based hepatitis C testing and linkage to care in Baltimore. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23(5):366–74. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edlin BR, et al. Is it justifiable to withhold treatment for hepatitis C from illicit-drug users? N Engl J Med. 2001;345(3):211–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107193450311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fokuo JK, et al. Recommendations for implementing hepatitis C virus care in homeless shelters: the stakeholder perspective. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4(5):646–656. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dever JB, et al. Engagement in care of high-risk hepatitis C patients with interferon-free direct-acting antiviral therapies. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(6):1472–1479. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang G, et al. Provider perceptions of hepatitis C treatment adherence and initiation. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(5):1324–1333. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05877-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogal SS, et al. Primary care and hepatology provider-perceived barriers to and facilitators of hepatitis C treatment candidacy and adherence. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(8):1933–1943. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4608-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adekunle RO, DeSilva K, and Cartwright EJ. Hepatitis C care continuum in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive cohort: data from the HIV Atlanta Veterans Affairs Cohort Study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020; 7(4): p. ofaa085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Noska AJ, et al. Engagement in the hepatitis C care cascade among homeless veterans, 2015. Public Health Rep. 2017;132(2):136–139. doi: 10.1177/0033354916689610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Travaglini LE, et al. Access to direct-acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C virus among veterans with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(2):192–195. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barocas JA, et al. Experience and outcomes of hepatitis C treatment in a cohort of homeless and marginally housed adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):880–882. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noska AJ, et al. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus among homeless and nonhomeless United States veterans. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(2):252–258. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belperio PS, et al. Curing Hepatitis C virus infection: best practices from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(7):499–504. doi: 10.7326/M17-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graham J. VA extends new hepatitis C drugs to all veterans in its health system. JAMA. 2016;316(9):913–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shwartz M, et al. A probability metric for identifying high-performing facilities: an application for pay-for-performance programs. Med Care. 2014;52(12):1030–6. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Juhnke C, Bethge S, Muhlbacher AC. A review on methods of risk adjustment and their use in integrated healthcare systems. Int J Integr Care. 2016;16(4):4. doi: 10.5334/ijic.2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Byrne T, et al. A novel measure to assess variation in hepatitis C prevalence among homeless and unstably housed veterans, 2011-2016. Public Health Rep. 2019;134(2):126–131. doi: 10.1177/0033354918821071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montgomery AE, et al. Universal screening for homelessness and risk for homelessness in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S210–1. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maier MM, et al. Cascade of care for hepatitis C virus infection within the US Veterans Health Administration. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):353–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.NVivo qualitative data analysis software. Version 12, 2018 ed: QSR International Pty Ltd.; 2018.

- 39.Ritchie J and Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research, in Analyzing qualitative data, A. Bryman and R. Burgess, Editors. 1994, Routledge: London. p. 173-194.

- 40.AASLD-IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2018 Update: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis, 2018. 67(10): p. 1477-1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Nueces D. Stigma and prejudice against individuals experiencing homelessness. 2016; p. 85-101.

- 42.Wen CK, Hudak PL, Hwang SW. Homeless people's perceptions of welcomeness and unwelcomeness in healthcare encounters. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):1011–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0183-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Toole TP, et al. Needing primary care but not getting it: the role of trust, stigma and organizational obstacles reported by homeless veterans. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(3):1019–31. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Northrop JM. A dirty little secret: stigma, shame and hepatitis C in the health setting. Medical Humanities. 2017;43(4):218. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2016-011099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dowsett LE, et al. Living with hepatitis C virus: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of qualitative literature. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:3268650. doi: 10.1155/2017/3268650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koh HK, O’Connell JJ. Improving health care for homeless people. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2586–2587. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.18760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coyle C, et al. The hepatitis C virus care continuum: linkage to hepatitis C virus care and treatment among patients at an urban health network, Philadelphia, PA. Hepatology. 2019;70(2):476–486. doi: 10.1002/hep.30501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rajabiun S, et al. The influence of housing status on the HIV continuum of care: results from a multisite study of patient navigation models to build a medical home for people living with HIV experiencing homelessness. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(S7):S539–S545. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 24 kb)

(DOCX 28 kb)

(DOCX 23 kb)

(DOCX 20 kb)