Abstract

Background

The prevalence of harassment and discrimination in medicine differs by race and gender. The current evidence is limited by a lack of intersectional analysis.

Objective

To evaluate the experiences and perceptions of harassment and discrimination in medicine across physicians stratified by self-identified race and gender identity.

Design

Quantitative and framework analysis of results from a cross-sectional survey study.

Participants

Practicing physicians in the province of Alberta, Canada (n=11,688).

Main Measures

Participants completed an instrument adapted from the Culture Conducive to Women’s Academic Success to capture the perceived culture toward self-identified racial minority physicians (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC)), indicated their perception of gender inequity in medicine using Likert responses to questions about common experiences, and were asked about experiences of reporting harassment or discrimination. Participants were also able to provide open text comments.

Key Results

Among the 1087 respondents (9.3% response rate), 73.5% reported experiencing workplace harassment or discrimination. These experiences were least common among White cisgender men and most common among BIPOC cisgender women (52.4% and 85.4% respectively, p<0.00001). Cisgender men perceived greater gender equity than cisgender women physicians, and White cisgender men physicians perceived greatest racial equity. Participant groups reporting the greatest prevalence of harassment and discrimination experiences were the least likely to know where to report harassment, and less than a quarter of physicians (23.8%) who had reported harassment or discrimination were satisfied with the outcome. Framework analysis of open text responses identified key types of barriers to addressing racism, including denial of racism and greater concern about other forms of discrimination and harassment.

Conclusions

Our results document the prevalence of harassment and discrimination by intersectional identities of race and gender. Incongruent perceptions and experiences may act as a barrier to preventing and addressing harassment and discrimination in the Canadian medical workplace.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-07734-8.

KEY WORDS: harassment and discrimination, equity, physician workforce, gender equity, racism

INTRODUCTION

Workplace racism1 and sexism2 are experienced by 20 to 70% of physicians.3–7 Despite this, denials of interpersonal8 and structural9 harassment and discrimination persist. Hesitation to properly name racism and sexism3 or lack of empathy for experiences of discrimination by those with privilege2 may contribute to this persistence.10 Furthermore, though influence of intersectional identities on the experiences of racism and sexism is well recognized,11 an intersectional lens has not been consistently used to examine harassment and discrimination among physicians.12

The aim of this cross-sectional survey study was to characterize the experiences of harassment and discrimination among physicians working in a single health system in the province of Alberta, Canada, using an intersectional lens. In this analysis, we compare experiences of harassment and discrimination among physicians from historically marginalized groups (e.g., racial and gender minority groups) with perceptions of these experiences by physicians with racial and gender privilege (e.g., White and cisgender men) who work within the same healthcare system.

METHODS

Study Design

This article describes a subset of results from a cross-sectional study of physicians in Alberta. Additional results from this study describing the diversity of the physician workforce13 and interpersonal anti-Indigenous bias of physicians14 are described elsewhere. This study was approved by the University of Calgary’s institutional ethics review board (REB20-1138) and is reported based on guidelines for self-administered surveys of physicians.15

Constructs and Context

Alberta is a province of 4.5 million people with about 12,000 practicing physicians in a single healthcare system. These physicians are 60% male, 39% female, and less than 3% are transgender, non-binary gender, gender diverse, or two-spirit.13 Based on demographic data collected by our team, about 50% of Alberta physicians are White, 15% of physicians are Asian, and less than 5% of Alberta physicians identified as each of Black, Indigenous, Latinx, or Middle Eastern.13 Nearly 20% of participants did not disclose their racial identity.

Race is a socially constructed identity based on skin pigmentation and cultural ancestry.16 Despite attempts to identify biologic or genetic definitions of race, there are no standard categories or definitions.17 In this study, racial identity is based on participant self-determination. We use the acronym BIPOC to refer to Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, a heterogenous group of people who experience racism, exclusion, and marginalization based on the color of their skin. We have combined this group to protect the anonymity of participants from smaller demographic categories; however, this is a group with diverse lived experiences.

Jones’ Levels of Racism framework describes institutional, interpersonal, and internalized racism as intentional or unintentional disadvantages conferred upon a racial group based on their perceived race.16 Racism is racial bias plus power (e.g., unearned privilege ascribed by society to individuals based on random attributes such as skin color18) to affect the outcomes or experiences of a group of people.19 Institutional racism is “codified in our institutions of custom, practice, and law”;16 for example, the epidemic of tuberculosis among Indigenous people in Canada originated in the overcrowding and lack of nutrition in residential schools and the imprisonment of Indigenous people suspected to have tuberculosis.20 Interpersonal racism refers to intentional or unintentional actions by a specific person, manifesting as “lack of respect, suspicion, devaluation, scapegoating, and dehumanization”;16 a contemporary example was documented by Joyce Echaquan, an Indigenous woman who died while being mocked by members of the healthcare team.21 Internalized racism refers to “acceptance” of their own lack of worth by members of racially marginalized groups.16

Interpersonal and institutional anti-Indigenous racism has been well-documented in Alberta in peer-reviewed literature22,23 and high-profile media cases.24,25 A recent investigation into anti-Black racism perpetrated by an Alberta surgeon toward a physician colleague has drawn additional attention to the culture of medicine in Alberta.8 Thus far, interpersonal bias has been studied from the perspective of racially marginalized patients and physicians rather than from the perspectives of those who hold these harmful biases. There is a need to investigate the drivers of structural and interpersonal discrimination among Alberta physicians, including an investigation of the explicit and implicit racist beliefs of physicians.

The systemic and interpersonal sex- and gender-based harassment and discrimination of women physicians in Alberta has been documented.2,26 Gender is the self-characterization as masculine, feminine, androgenous, or another expression based on societal norms, roles, and relationships.27 In Canadian cultural norms, femininity includes caregiving roles and communal personality traits and masculinity includes leadership roles and agentic personality traits.28 Sex refers to legal gender, documented on government identification.27 In Canada, there are three legal options for sex: female, male, and X.

Participants and Recruitment

A link to the survey was circulated to all practicing physicians in Alberta (n=11,688) via the newsletters of the Alberta Medical Associations, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta, and Alberta Health Services between September 1st to October 15th, 2020. Only a single notification was sent via each organization to reduce the number of e-mails that physicians were receiving during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reminders to complete the survey were posted on the social media accounts of these organizations without a link to the survey. Informed consent was obtained for all respondents. Participants were uncompensated.

Survey Measures and Development

This study was designed by a diverse team of researchers, students, and physicians, including First Nations, Métis, and racially marginalized people and cisgender men and women (Appendix 1). Development and pilot testing of the survey are described elsewhere.13 In brief, the 7 domains were selected based on previous literature and input of key stakeholders: demographics, workplace characteristics, leadership roles, gender-based workplace harassment and discrimination, and race-based workplace harassment and discrimination, explicit anti-Indigenous bias, and implicit anti-Indigenous bias. The survey was administered using Qualtrics (Provo, UT). The total number of questions varied based on previous responses (range 65–175). The survey was pilot tested by 20 physicians with diverse lived experience and expertise in survey methods.

Respondents were asked to indicate whether they thought women physicians experienced greater disadvantage, men physicians experienced greater disadvantage, or whether women and men equally experienced disadvantage for six themes of gender discrimination identified in a previous study.2 These six themes were workplace harassment and discrimination, compensation inequality, exclusion from work events, access to leadership opportunities, and support for parenthood for men and for women. Participants also rated their agreement with the statement “Gender equity issues are an important problem for physicians in Alberta” on a continuous slider from 0 (no agreement) to 100 (complete agreement).

Participants reported their perceptions of discrimination faced by BIPOC physicians using the domains of Leadership Support, Equal Access, and Freedom from Bias in the Culture Conducive to Women’s Academic Success (CCWAS) which were adapted to ask about the experiences of BIPOC physicians.29 The CCWAS measures the culture of an academic department toward women and has been used to understand the climate of gender equity for academic medical departments.2,29 Responses to 47 items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” with a neutral option. For community physicians, we removed 7 questions pertaining to research support. Adaptations were made through discussion with members of the respective groups, including community physicians, and underwent pilot testing. Lower scores indicate greater perceived racial discrimination. Six items measured experiences of workplace harassment or discrimination based on commonly reported experiences from the literature and from our stakeholder group. We used follow-up questions to characterize these experiences.

Analysis

Demographic groups with fewer than 50 participants are reported in aggregate to protect participants from identifiability. Subgroups were identified a priori, and included gender identity, race, and intersectional identities of gender identity and race (White cisgender men, White cisgender women, BIPOC cisgender men, and BIPOC cisgender women). Missing data and nonresponse were expected to be non-random, given the sensitive and potentially identifiable information collected in this survey. For this reason, we performed a sensitivity analysis for participants who were missing gender or racial identity data (eTables 1–2, eFigures 1–2) according to the methods outlined by Halbesleben and Whitman.30 Analysis of missingness and nonresponse bias has been reported for this study population by comparing the demographics of respondents to the known demographics of Alberta physicians.13 Early career physicians, physicians working in urban centers, and women physicians were overrepresented in this study.13 White physicians were underrepresented.13

Participants who answered “prefer not to answer” or “unsure” were combined with participants who selected “no” or “never” to avoid overestimating the prevalence of harassment and discrimination. Data was non-parametrically distributed and is reported using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Kruskal-Wallis and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare measures between the four and two categories of demographic groups, respectively. Data analysis was performed using Stata (College Station, TX).

Free text responses to the prompt “Please use this space to tell us anything you want us to know” were coded inductively using framework analysis31 by two study team members (S. M. R. and P. R.). They first familiarized themselves with free text comments then performed open coding. Codes were grouped and defined by P. R. to create an analytic framework which was reapplied to all comments independently and in parallel by S. M. R. and P. R. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Lastly, the data were charted into a matrix and analyzed for patterns, contrasts, and commonalities.32 P. R. is a non-physician researcher and feminist Métis cisgender woman with expertise in qualitative methods, Indigenous health research, and anti-racist health systems safety. S. M. R. is a White settler, cisgender woman feminist physician with expertise in qualitative research methods. Comments were de-identified and edited only for spelling and grammar.

RESULTS

There were 1087 participants (response rate 9.3%; Table 1): 363 cisgender men (33.4%), 509 cisgender women (46.8%), and fewer than 25 individuals who identified as transgender, non-binary gender, gender diverse, two-spirit, or a gender that was not listed (<3%). Most respondents were White (n=547, 50.3%), less than 5% identified as Indigenous, Hispanic, Latinx, or Southeast Asian, and less than 10% identified as Black, Middle Eastern, South Asian, or East Asian. Most participants were White cisgender women (39.2%, n=326). Notably, 24.0% preferred not to disclose their race and/or gender identity.

Table 1.

Select Demographic Characteristics of Survey Participants

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Entire cohort | 1087 | - |

| Gender identity* | ||

| Cisgender men | 363 | 33.4 |

| Cisgender women | 509 | 46.8 |

| Transgender men | 1–25 | <3% |

| Transgender women | 1–25 | |

| Non-binary gender | 1–25 | |

| Gender diverse | 1–25 | |

| Two-spirited | 1–25 | |

| Self-described, unsure, or preferred not to answer | 48 | 18.5 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Member of the LGBTQI2S+ community | 25–50 | <5% |

| Heterosexual | > 1000 | >95% |

| Race or ethnicity* | ||

| Black | 50 | 4.6 |

| White | 547 | 50.3 |

| Indigenous | 1–25 | <3% |

| Hispanic† | 1–25 | <3% |

| Latinx† | 1–25 | <3% |

| Middle Eastern | 53 | 4.9 |

| South Asian | 82 | 7.5 |

| East Asian | 67 | 6.2 |

| Southeast Asian | 1–25 | <3% |

| Race not listed | 33 | 3.0 |

| Preferred not to answer | 188 | 17.3 |

| Discipline of practice | ||

| Family medicine | 291 | 33.4 |

| Medical specialty | 381 | 43.7 |

| Surgical specialty | 88 | 10.1 |

| Not listed | 96 | 11.1 |

| Preferred not to answer | 15 | 1.7 |

| Years in practice | ||

| 26–30 years | 23 | 2.5 |

| 31–35 years | 144 | 15.9 |

| 36–40 years | 144 | 15.9 |

| 41–45 years | 125 | 13.8 |

| 46–50 years | 127 | 14.1 |

| 51–55 years | 118 | 13.1 |

| 56–60 years | 81 | 9.0 |

| 61–65 years | 70 | 7.7 |

| Older than 65 years | 60 | 6.6 |

| Practice location* | ||

| Metropolitan center | 644 | 67.6 |

| Urban center | 105 | 11.0 |

| Large rural center | 44 | 4.6 |

| Rural area | 62 | 6.5 |

| Remove area | 21 | 2.2 |

| Not listed | 77 | 8.1 |

*Multiple responses permitted, percentages may exceed 100%

†Hispanic refers to people who speak or whose ancestry originates in Spanish-speaking countries. Latinx is the gender-inclusive term for people whose ancestry is from countries in Latin America. While many Hispanic people are also Latinx, not all Latinx people are Hispanic (e.g., someone from Brazil) and not all Hispanic people are Latinx (e.g., people from Spain)

Prevalence of Harassment, Discrimination, and Bias

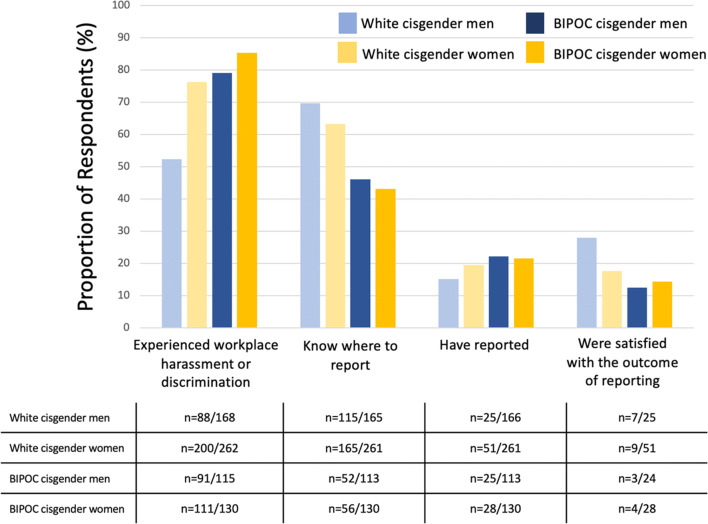

Workplace harassment and discrimination were least common among White cisgender men and most common among BIPOC cisgender women (Fig. 1; 52.4% and 85.4%, respectively, p<0.00001). Gender identity and skin color were the most common perceived reasons from a list of eight potential characteristics, including an open text field (60.3% and 24.9% of participants, respectively). Over a quarter of physicians had reported workplace harassment or discrimination (n=156) and less than a quarter of physicians who had reported were satisfied with the outcome (n=24, 23.8%). The patterns in these data were unchanged when the analysis was performed to account for missing data (eFigure 1).

Figure 1.

Experiences and reporting of discrimination, harassment, or bias at work by gender and racial identity. BIPOC = Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

Gender-Based Harassment, Discrimination, and Bias

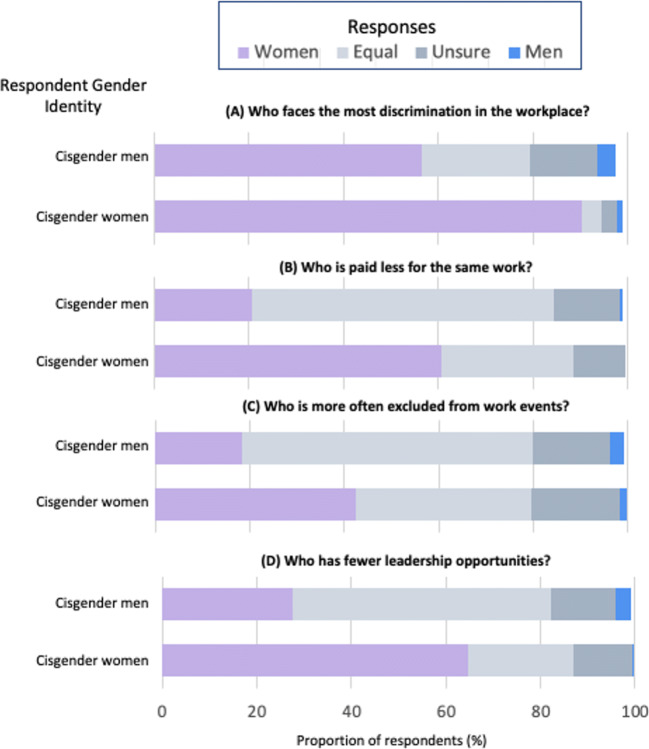

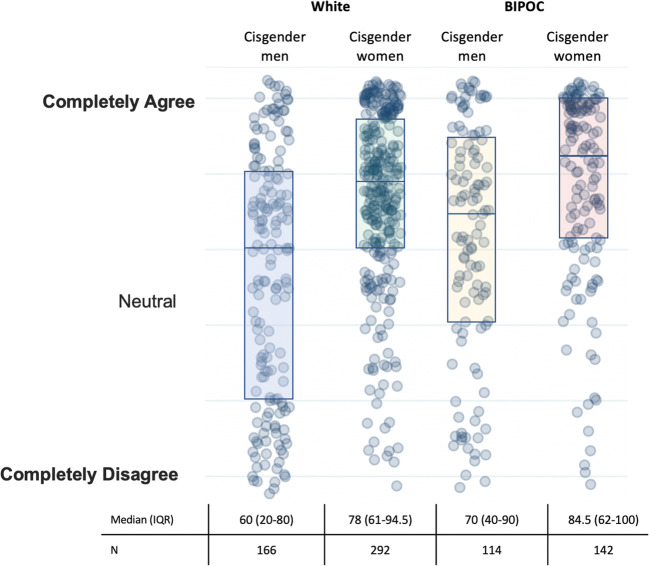

Cisgender women perceived greater inequity for women than cisgender men respondents in all domains (Fig. 2) and rated gender equity issues as more important than cisgender men (median 80 (IQR 61–99) and 63 (IQR 29–83), respectively, p<0.0001; Fig. 3). Participants who did not report a gender identity had a lower agreement that gender equity was a problem for Alberta physicians (eFigure 2).

Figure 2.

Perceptions of gender-based discrimination by respondent gender identity.

Figure 3.

Agreement with the statement “Gender equity issues are an important problem for physicians in Alberta.” Each circle represents a respondent’s answer. Medians and interquartile ranges are overlayed. BIPOC = Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

Race-Based Harassment, Discrimination, and Bias

Over 90% of BIPOC physician participants reported experiencing or witnessing workplace racial discrimination compared to 6.4% of White physicians. BIPOC cisgender women most commonly reported having to represent their entire race or ethnicity compared to BIPOC cisgender men physicians and White cisgender women physicians (70.2% compared with 64.0% and 34.2%, respectively; p<0.0001).

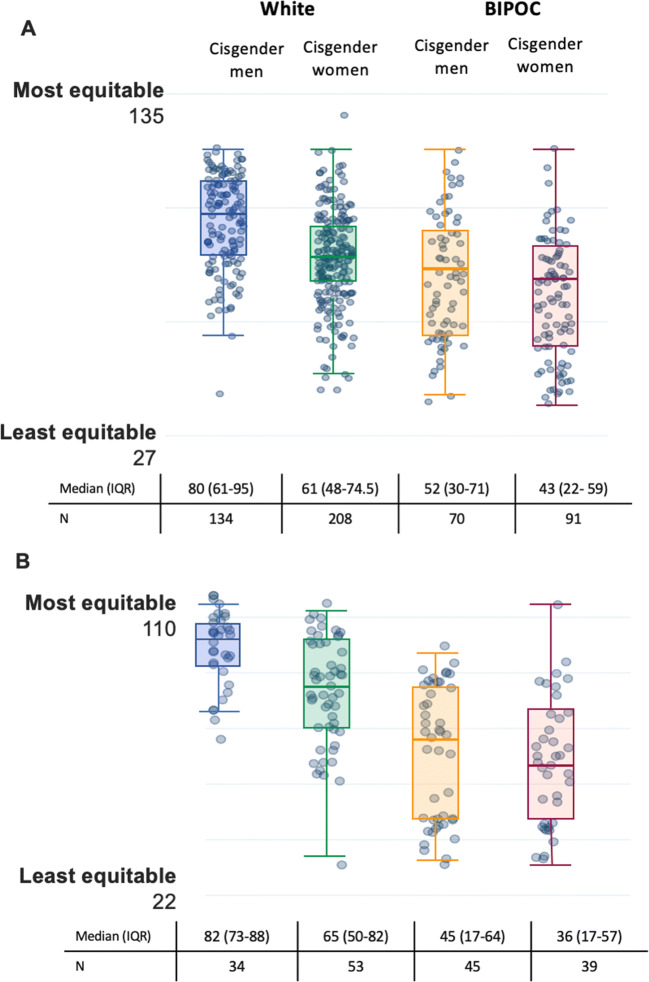

White participants rated the community and academic workplace culture as more racially equitable than BIPOC physicians (p<0.0001 for both; Fig. 4). Cisgender White men perceived the workplace as the most racially equitable and BIPOC cisgender women physicians the least equitable (p=0.0001; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Culture of the workplace for BIPOC physicians for A academic and B community physicians. Each circle represents a respondent’s answer. Medians and interquartile ranges are overlayed. BIPOC = Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

Framework Analysis

After removing generic comments (e.g., “thank you”; n=16), 240 participants contributed comments. Over half of BIPOC cisgender women commented (n=80, 53.0%) compared to less than 10% of White cisgender women. There were 45 comments (14.6%) from participants who did not provide their racial and/or gender identity and the majority of these described experiences of racism. We categorized responses into four themes: experiences of racism, reporting harassment, barriers to addressing racism, and other forms of discrimination and harassment (Table 2). Some comments were included in multiple themes.

Table 2.

Framework Analysis and Exemplar Quotations About Racism in the Medical Workplace

| Theme/code | Exemplar quotation |

|---|---|

| Experiences/lack of racism |

“I am married to a (BIPOC) individual… some of my colleagues have directly demonstrated micro and macroaggressions towards (them) at informal gatherings (which shocked me to hear).” [P12, White cisgender woman, leader] “Academic racism is obvious and it is the elephant in the room that some want to ignore.” [P376, BIPOC cisgender man] “There was an incident when I was ‘taught a lesson’ but I was not targeted, rather it was said ‘may be its your CULTURE’. I would have appreciated reprimanding me rather than my culture. Maybe culture was used as a polite gesture, but it did hurt more. I still feel that pain. Had it been a white person, it would have been his fault and if it’s a (person of color) it’s his culture's fault. I have been very surprised to see that even highly educated, open-minded white people (not all) still think that way.” [P430, BIPOC cisgender woman] “A (family member) of a white physician needed surgery. The white (physician) insisted that a white anaesthesiologist do her anaesthesia… the (physician family member) insisted not to let any non-white health care provider touch (their family member). (This) cause(d) a lot of problems and delayed several patient(‘s) care. However, the hospital administrator accommodated (their) request, approving (their) conduct and compromised several patient(s) care (and) no action was taken against (them).” [P906, BIPOC cisgender man] “As (an) IMG, I have worked in several countries and I never seen the level of racism as (I have) in rural Alberta, and worse, they are supported by the (health system) and (regulatory body) administrations. I have seen first-hand… a physician who raised concerns about racism … and was harshly punished, humiliated and (their) career was destroyed. This why I stop(ped) doing locum(s) in rural Alberta and soon I will leave to a better place.” [P979, not provided] “Generally, Albertans do a good job in workplace to ensure equal opportunity for everyone despite race, sex etc.” [P295, BIPOC cisgender man] |

| Rationalizing racism | |

| Denial & uncertainty |

"More likely discrimination academically due to specialty of anesthesia for academic promotion compared with internal medicine rather than skin color" [P564, cisgender man] “From the point of view of a minority, I think this modern fashion of fixating on race, gender, sexuality is wrongheaded and regressive. I wish to make it clear that I feel fortunate to live in this country, and I have rarely ever felt discriminated against. As often, I think Canadians go out of their way to be inclusive, even if it equates to reverse discrimination. I truly hope that the medical profession resists the apparent urge to jump on the regressive and dangerous politically correct bandwagon.” [P389, BIPOC participant] “It is a dangerous mistake to filter all interactions through race. For example, if I don't get a promotion because another candidate is more qualified and I happen to be a minority if there is a lot of information (such as this survey) that implies that all interactions are racism, then I will be more likely to perceive it as so even if there is not racism in play. Some people are jerks to everyone. If they are a jerk to a white person, they are often just considered a jerk, but if they are a jerk to a non-white person, it is easily perceived as racism, even though the underlying problem is one of jerkiness, not necessarily racism.” [P522, White cisgender man] “Caucasians sometimes accuse other Caucasians of racism as a weapon when an act of racism has not occurred, and it is a difficult smear to get rid of.” [P902, White cisgender man] |

| Colorblindness |

“I feel the same about everyone." [P414, White cisgender woman] “I respond to the person, not their gender, race, religion, or orientation.” [P468, White cisgender man] |

| Whataboutism |

“Why did you not ask about sexuality, which is where my discrimination experience lies?” [P630, White cisgender man, leader] “I'm surprised and disappointed that there were (no) questions about age discrimination.” [P582, cisgender man] |

| Meritocracy |

“Exactly equal participation in the various aspects of medicine (clinical, leadership, etc.) is not the desired outcome. The fact that a physician chooses to spend more time with family vs. administration is not an indication of systemic bias, but of individual choices and values. Insisting on racial/gender/geographic equity in every aspect of medicine actually induces a negative bias of selecting individuals based on something other than suitability for the position.” [P488, White cisgender man, leader] “In Canada, at least as far as my experience in (specialty) goes, I cannot think of another profession that demonstrates equality better... we are treated as equals, regardless of gender, race or orientation, at least in private practice. You work hard, you do the job well, you treat people with respect... and you're paid exactly the same every Friday via fee-for-service. That's my experience; your study is very rigid and doesn't allow for variables.” [P435, White cisgender man] |

| Discomfort | |

| “Reverse racism” |

“I would be concerned about reverse discrimination of white Canadians.” [P278, White cisgender man] “In some environments there is racial discrimination against white skinned faculty.” [P455, White cisgender woman] “Your questions about race were designed in several cases in a way that asked if the minority group had as much opportunity as Caucasians. One possible scenario that was omitted is if the minority group had experienced more opportunity than Caucasians. While suspected to be less likely this may happen in some cases as well, such as in some medical school admissions processes.” [P469, White cisgender man] |

| Skepticism about change |

“Many organizations I work for only pay lip service to gender and diversity. I do not believe they are capable of the long-term work that needs to happen to address these issues. Diversity and inclusion is having its moment in the sun and will fade again… the rank and file physician and learners also know that this is all just a flash in the pan and true power structures and systems will not change. They just have to imitate the current mantra and will be given a pass and move on to hoard the powers they will amass.” [P63, BIPOC cisgender woman, leader] “Universities do nothing serious to address harassment. They talk the talk, not walk the walk.” [P279, White cisgender man] “Racism is a problem in medical field and cannot be fixed.” [P891, BIPOC participant] |

Experiences of Racism (n=57)

Examples of witnessed or experienced racism included “I did my rural rotation in [location]. There was a lovely and very good [BIPOC] doctor… many patients and even the nurses were so overtly discriminatory against (them) because (they were) from [Country],” (P26, White cisgender woman) and “I used to locum in small towns; I had to stop going to [location] and [location] because of racism,” (P1014, BIPOC cisgender woman). In contrast, some BIPOC participants experienced a lack of discrimination: “Living and working in Canada has been a very good experience so far at the workplace,” (P609, BIPOC cisgender man).

Reporting Harassment (n=14)

Twelve participants reported a lack of support from their leadership. Many respondents were unsatisfied because they perceived that “nothing came of (reporting),” that they were “dismissed,” and that reporting was “time-consuming.” Multiple participants described perceived retaliation, including more than one participant who reported that they were no longer offered work at a site where they had reported harassment, another who was subject to a counter-complaint after their report was released to their harasser, and several who reported worse behavior by the subject after reporting.

Barriers to Addressing Racism/Rationalizing Racism

There were 79 participant comments that denied the existence of racism. Analysis of these comments exemplified important barriers to addressing racism in medicine.

-

i.

Meritocracy (n=4)

Four White cisgender men participants felt merit was the most important criteria that determined the treatment of physicians, “Affability, merit, skills, and availability always trump discrimination in medicine,” (P40), or that racism was used as an excuse, “Some physicians who are lazy try to use the RACE card so that their inadequacies are not able to be used against them,” (P837).

-

ii.

Colorblindness (n=5)

Colorblind racism is an ideology of treating everyone “equally” while ignoring the documented influence of racism on racial minorities.33 Colorblindness was solely endorsed by White participants: “If we just consider one race, the human race, we’d all be better off,” (P393, cisgender man).

-

iii.

“Whataboutism” (n=10)

Ten participants, most of whom were White, felt that other issues facing physicians were more pressing (e.g., “whataboutism”). One White cisgender man commented “(There are) much bigger issues facing society and the profession than gender and race. How about access for patients to care, clinical competency and managing a pandemic?” (P938).

-

iv.

Discomfort (n=11)

Many White participants expressed discomfort discussing race/racism, stating that the questions asking about biases were “racist,” “inappropriate,” or “odd.” Some participants shared discomfort when working with patients: “I feel very ill at ease when (asking) Indigenous patients (about alcohol and drug consumption) as I fear they will assume that I am prejudiced,” (P11, White cisgender woman). This discomfort was recognized by BIPOC participants: “It is a taboo to talk about racism. Those who dared to raise a concern about racism got punished and labeled as disruptive,” (P546, cisgender man).

-

v.

Denial and uncertainty (n=14)

Denial of the existence of racism was common. One White cisgender man with a leadership role in medicine wrote “I do not see any discrimination. Everyone (is) basically equal,” (P826). Many BIPOC physicians shared that their colleagues did not believe that they had experienced racism; for example, “We have been subjected to biases which our white colleagues deny ever exist and shut us down if we try raising the issue” (P865).

Similarly, some White participants referred to need for evidence of discrimination: “Some (POC) claim that they have been discriminated (against), but we also have many (POC) in leadership duties, as heads of departments, and I myself haven't 'heard' of lack of promotion or hiring based on color,” (P464, White cisgender woman). These doubts were internalized by some BIPOC participants: “I tend to internalize comments that some may consider derogatory... I sometimes wonder if this is in my head/my own perception or real,” (P402, cisgender woman).

-

vi.

“Reverse racism” (n=32)

“Reverse racism” refers to the assumption that there is a “level playing field” between White and BIPOC people such that any attention to racism puts White people at a disadvantage. This ignores the ample evidence of systemic disadvantages faced by BIPOC individuals.

Concerns about reverse racism were among the most common rationalizations of racism among White participants (n=27); examples included “Current intense focus on gender, harassment, race issues may result in the alleged perpetrators becoming the recipients of the same perceived biases,” (P521, cisgender man) and “I am depressed that because I have white skin… I am to be punished by having less chance to get a leadership position, good job etc. because these positions are held for people of color…Where is fair competition here?” (P653, cisgender woman). Many participants used the terms “reverse racism” and “reverse discrimination” to describe perceived racial prejudice against White people.

DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional survey demonstrated a high prevalence of harassment and discrimination in the workplace for physicians working in a single universal healthcare system, particularly for women, BIPOC, and BIPOC cisgender women physicians. These data also suggest facilitators of ongoing harassment and discrimination, including a lack of safe and effective harassment reporting mechanisms. Framework analysis of text responses further characterizes workplace racism, including descriptions of important barriers to addressing systemic and interpersonal racism in our healthcare system: denial of racism, belief in the meritocracy, fears of “reverse racism,” and discomfort with discussing race and racism. Overall, these results demonstrate that experiences of racism, harassment, and discrimination are common in medicine, but prevalence differs across demographic groups. A lack of literacy in equity, diversity, and anti-racism among Albertan physicians are key barriers to addressing this racism.

Workplace harassment and discrimination have been clearly documented in the Canadian healthcare system. A survey of Black physicians in Ontario found that more than 70% had experienced racism at work.1 Harassment and discrimination were key themes in two qualitative studies of gender equity in academic departments in Alberta.2,34 A survey of Canadian medical students found that sexual harassment from patients, peers, and preceptors was normalized in the workplace culture but had important consequences for those who had experienced it.4 Along with our results, these data reinforce that harassment and discrimination are urgent problems in the medical workplace culture.

Nearly twice as many cisgender women and BIPOC participants had experienced harassment or discrimination at work compared to White cisgender men. This inequitable distribution of harassment and discrimination has been reported consistently35,36 in medical students,3 residents,6 and physicians5,37 in multiple countries.38–40 Physicians with intersectional identities more commonly reported harassment in our study and others,41 with the greatest proportion of BIPOC cisgender women reporting workplace harassment. Formal reporting of harassment and discrimination was uncommon and all groups were generally unsatisfied with this process. The reasons given for low rates of reporting and low satisfaction with reporting were consistent with previous literature,3,42 including experiences of retaliation, a sense of lack of effectiveness associated with reporting, and dismissal of complaints without investigation. This suggests that current harassment reporting mechanisms in Alberta are not meeting the needs of physicians,43 which disproportionately disadvantages BIPOC women physicians who experience the greatest rates of harassment and discrimination.

Consistent with other literature,2 we found that participants with racial and gender privilege (e.g., cisgender White men18) perceived a more equitable workplace than participants from other groups. For example, despite finding that 85% of cisgender women had experienced harassment or discrimination at work compared to 45% of cisgender men, about 20% of cisgender men were either unsure or felt that men physicians experience more discrimination than women. Similarly, White cisgender men perceived the greatest amount of racial equity in the workplace. This reinforces the need for diverse, representative leadership that may more effectively recognize and act on harassment and discrimination.44

Our results highlight potential barriers to addressing harassment and discrimination in the medical workplace. First, our data suggest that physicians without lived experience are generally less aware of the prevalence and impacts of harassment and discrimination on their colleagues. Collection and transparent reporting of these data may raise awareness of these issues among leadership and the general workforce.45 Second, the common patterns of rationalization of racism, harassment, and discrimination should be directly addressed through longitudinal, targeted education;46 these include denial of racism,19 “whataboutism,” and belief in the meritocracy.44 The selection process for leadership positions should aim to identify individuals with harmful beliefs to prevent role modelling a culture of racism in medicine. Strategies to identify these beliefs could include interview questions about racism,14 simulations or scenarios that require a leader to demonstrate skills in anti-racism, or review of previous concerns or reports. Third, support for physicians from equity-deserving groups who experience harassment or discrimination is clearly needed. These interventions must prioritize groups who suffer a disproportionate amount of discrimination. Skills for bystanders to intervene when they witness harassment and discrimination are likely to be helpful, as are policies for staff in how to approach these intances.47 Lastly, our data emphasize the need for evidence-informed harassment reporting mechanisms that are accessible, effective, and safe for physicians.43

The low response rate in our survey is likely multifactorial. The study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic at a time when hospitalizations were peaking locally. The sensitive nature of the study questions may have restricted participation. The typical response rate among physicians in Canada is about 30%,48,49 though our response rate is comparable to other surveys of physicians in Alberta.50 This low response rate contributes to the innate risk of response and recall bias given the retrospective and sensitive nature of the study questions.51 Participants with outlier positive or negative experiences may have been more motivated to respond. A comparison of the demographics of the study population with Alberta physicians suggests that White physicians, cisgender men, rural, and academic physicians were less represented in our sample;13 the effect of this nonresponse on our data and conclusions is not known but the prevalence of harassment and discrimination should be interpreted with this in mind. Furthermore, many participants did not provide their demographic data, limiting our ability to compare experiences between demographic groups. Despite these limitations, we were able to corroborate trends reported in other settings. Our study was undertaken in a single province in Canada and the results may not be transferable to other settings. Similarly, there may be subcultures across Alberta where experiences or perceptions of harassment and discrimination may differ or where structural barriers for specific groups may limit where certain participants practice. Lastly, though our results describe the higher prevalence of harassment experienced by participants with intersectional identities of race and gender, our results do not describe the unique experience of harassment by intersecting identities (e.g., misogynoir, the specific anti-Black sexism experienced by Black women52,53), which deserves dedicated study.

Evidence-informed solutions to address harassment and discrimination in the medical workplace are urgently needed. This cross-sectional study of experiences and perceptions of harassment and discrimination among physicians in a single but large health system provides insights into demographic differences that may contribute to different perceptions of the urgency of sexism and racism in medicine. Furthermore, framework analysis provides an exploratory description of potential barriers to addressing racism among physicians. These results can guide further study and inform interventions to target drivers of bias in medicine.14,46

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 285 kb)

Acknowledgements

Contributors: Angela Unsworth, Mona Sikal, Marni Panas, Jamie Rice, Lisa Beesley, and Debrah Wirtzfeld from Alberta Health Services; Stephanie Usher from the Alberta Medical Association; and Melissa Campbell and Nicole Kain from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta for their assistance with development and distribution of the survey.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the study questions and potential for participant identification. Aggregate, de-identified data are available from the corresponding author by reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior presentations: None.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mpalirwa J, Lofters A, Nnorom O, Hanson MD. Patients, Pride, and Prejudice: Exploring Black Ontarian Physicians' Experiences of Racism and Discrimination. Acad Med. 2020;95 (11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Research in Medical Education Presentations):S51-S7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Ruzycki SM, Freeman GF, Bharwani A, Brown A. Association of physician characteristics with perceptions and experiences of gender equity in an Academic Internal Medicine Department. JAMA Netw Open. 2019a;2(11):e1915165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine. Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies; 2018. [PubMed]

- 4.Phillips SP, Webber, J., Imbeau, S., Quaife, T., Hagan, D., Maar, M., et al. Sexual harassment of Canadian Medical Sudents: a national survey. Lancet. 2019;7:15-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, Perumalswami CR, Ubel P, Stewart A. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Hu YY, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, Yang AD, Cheung EO, Moskowitz JT, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1903759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Expert Advisory Group on discrimination bash. Report on Discrimination, Bullying, and Sexual Harassment. Royal Australasian College of Surgeons; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Russell J, Rusnell C. Grande Prairie surgeon who taped noose to operating room door guilty of unprofessional conduct. CBC News. 2021;Sect. Edmonton.

- 9.Lee BY. JAMA Editor resigns, here is the latest fallout from podcast questioning structural racism. Forbes. 2021.

- 10.Stewart-Hess CH, Green TH. Account of 1,000 consecutive deliveries in a general practice based on a type of maternity unit. Br Med J. 1962;2(5312):1115-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Jain-Link P, Bourgeois R, Taylor Kennedy J. Ending harassment at work requires an intersectional approach. Harvard Business Review. 2019.

- 12.Golden SH. The perils of intersectionality: racial and sexual harassment in medicine. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(9):3465-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Ruzycki SM, Roach P, Ahmed S, Barnabe C, Holroyd-Leduc J. Diversity of physicians in leadership andn academic position in Alberta: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Leader. 2021a;in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Roach P, Ruzycki SM, Hernandez S, Charbertt A, Holroyd-Leduc J, Ahmed S, et al. Explicit and implicit anti-Indigenous bias among Albertan physicians: a cross-sectional study. Submitted. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME, Meade MO, Adhikari NK, Sinuff T, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ. 2008;179(3):245-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretical framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1212-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, et al. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0138511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nixon SA. The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: implications for health. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1637. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7884-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eddo-Lodge R. Why I’m no longer talking to white people about race: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2017. 289 p.

- 20.Hick S. The enduring plague: how tuberculosis in Canadian indigenous communities is emblematic of a greater failure in healthcare equality. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2019;9(2):89–92. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.190314.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banerjee S. 'I know I was mean and I apologize,' Quebec nurse tells inquiry into death of Joyce Echaquan. CTV News. 2021; 2021.

- 22.McLane P, Barnabe C, Mackey L, Bill L, Rittenbach K, Holroyd BR, et al. First Nations status and emergency department triage scores in Alberta: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2022;194(2):E37-E45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.McLane P, Bill L, Barnabe C. First Nations members’ emergency department experiences in Alberta: a qualitative study. Can J Emerg Med. 2021;23:63-74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Pimentel T. Investigation underway into how Ojibway woman died while in care of Alberta hospital. Aboriginal Peoples Television Network. 2021; 2021.

- 25.Geary A. Ignored to death: Brian Sinclair's death caused by racism, inquest inadequate, group says. CBC. 2017.

- 26.Services AH. Female Physician Leaders in Alberta Health Services. 2018.

- 27.Pilote L, Raparelli V, Norris C. Meet the methods series: methods for prospectively and retrospectively incorporating gender-related variables in clinical research 2021 Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/52608.html.

- 28.Koenig AM. Comparing prescriptive and descriptive gender stereotypes about children, adults, and the elderly. Front Psychol. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Westring AF, Speck RM, Sammel MD, Scott P, Tuton LW, Grisso JA, et al. A culture conducive to women's academic success: development of a measure. Acad Med. 2012;87(11):1622–31. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826dbfd1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halbesleben JR, Whitman MV. Evaluating survey quality in health services research: a decision framework for assessing nonresponse bias. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(3):913–30. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 4th Edition ed. College) DSG, editor. London, England: SAGE; 2018.

- 32.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(117). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Bonilla-Silva E. The structure of racism in color-bind, “post-racial” America. Am Behav Sci. 2015;59(11).

- 34.Ruzycki SM, McFadden C, Jenkins J, Kuriachan V, Keir M. Experiences and impacts of harassment and discrimination among women in cardiac medicine and surgery: a single-centre qualitative study. Can J Cardiol Open. 2022a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Cook DJ, Griffith LE, Cohen M, Guyatt GH, O'Brien B. Discrimination and abuse experienced by general internists in Canada. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):565–72. doi: 10.1007/BF02640367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lenhart SA, Klein F, Falcao P, Phelan E, Smith K. Gender bias against and sexual harassment of AMWA members in Massachusetts. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). 1991;46(4):121-5. [PubMed]

- 37.Jagsi R, Spector ND. Leading by design: lessons for the future from 25 years of the Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine (ELAM) program for women. Acad Med. 2020;95(10):1479–82. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Susan P Phillps JW, Stephan Imbeau, Tanis Quaife, Deanna Hagan, Marion Maar. Sexual harassment of Canadian Medical Students: a national survey. Lancet. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Chrysafi P, Simou E, Makris M, Malietzis G, Makris GC. Bullying and sexual discrimination in the Greek Health Care System. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(4):690–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yasukawa K, Nomura K. The perception and experience of gender-based discrimination related to professional advancement among Japanese physicians. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2014;232(1):35–42. doi: 10.1620/tjem.232.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mocanu V, Kuper TM, Marini W, Assane C, DeGirolamo KM, Fathimani K, et al. Intersectionality of gender and visible minority status among general surgery residents in CAnada. JAMA Surg. 2020;1(155):e202828. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wear D, Aultman J. Sexual Harassment in Academic Medicine: Persistence, Non-Reporting, and Institutional Response. Med Educ Online. 2005;10(1):4377. doi: 10.3402/meo.v10i.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martel K, Smyth P, Dhillon M, Rabi DM, Wirtzfeld D, Ruzycki SM. Harassment reporting mechanisms for physicians and medical trainees in Alberta: an environmental scan. Can Health Policy J. 2021 (July 2021).

- 44.Ruzycki SM, Franceschet S, Brown A. Making medical leadership more diverse. BMJ. 2021;373:n945. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Professionalism Oo. Office of Professionalism Annual Report. University of Alberta Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry; 2021.

- 46.Ruzycki SM, Holroyd-Leduc J, Brown A. EDI Moments to build knowledge of EDI in medical leadership. Submitted to a peer reviewed journal. 2022b.

- 47.Warsame RM, Hayes SN. Mayo Clinic’s 5-step policy for responding to bias incidents. AMA J Ethics. 2019;21(6):E521-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Davis PJ, Spady D, Forgie SE. A survey of Alberta physicians' use of and attitudes toward face masks and face shields in the operating room setting. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(7):455-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Grava-Gubins I, Scott S. Effects of various methodologic strategies: Survey response rates among Canadian physicians and physicians-in-training. Can Fam Phys. 2008;54(10):1424-30. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Gagnon MP, Duplantie J, Fortin JP. A survey in Alberta and Quebec of the telehealth applications that physicians need. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13(7). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Murdoch M, Simon AB, Polusny MA, Bangerter AK, Grill JP, Noorbaloochi S, et al. Impact of different privacy conditions and incentives on survey response rate, participant representativeness, and disclosure of sensitive information: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carbado DW, Gulati M. The Fifth Black Woman. J Contemp Legal Issues. 2001:701-29.

- 53.Manne K. Down girl: the logic of misogyny. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 285 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the study questions and potential for participant identification. Aggregate, de-identified data are available from the corresponding author by reasonable request.