In this series, a clinician extemporaneously discusses the diagnostic approach (regular text) to sequentially presented clinical information (bold). Additional commentary on the diagnostic reasoning process (italics) is integrated throughout the discussion.

CASE ALIQUOTS

A 28-year-old woman presented after noticing a swelling on her neck while looking in the mirror 6 weeks prior to evaluation. She also reported intermittent fever, malaise, and a 10-pound unintentional weight loss. She had no preceding illness, sick contacts, night sweats, arthralgias, rashes, rhinorrhea, sore throat, or dyspnea. Medical history was notable only for a tonsillectomy due to recurrent tonsilloliths 9 months prior. She took no regular medications. She had lived all her life in the southeastern US and worked from home as an administrator. She had no recent travel. She lived with her husband who was her only sexual partner. She did not use tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drugs. She reported having no pets or regular exposure to animals. She had seen her regular physician a few weeks into her symptoms and had both a negative COVID PCR and monospot test. She was given a course of clarithromycin without improvement.

A young woman with a history of tonsillectomy 9 months prior is presenting with subacute, painless neck swelling, intermittent fevers, and unintentional weight loss. To formulate an approach, neck swelling can be framed as a neck mass while awaiting physical examination to shed light on which structures are involved. The presence of intermittent fevers and unintentional weight loss in a patient with a neck mass raises concern for a subacute systemic inflammatory process that prioritizes workup for infectious processes with secondary consideration given to malignancies, endocrinopathies, and rheumatologic diseases.

In regard to infections, lack of response to clarithromycin lowers concerns for atypical infections, while viral etiologies such as HIV or CMV, and indolent bacterial infections such as Mycobacterial species and fungi warrant consideration. The subacute time course makes pyogenic bacterial infections less likely. While in older adults a subacute painless neck mass would be highly suspicious for malignancy, this is less common in younger patients. However, it’s a category worth keeping in mind as lymphomas, specifically Hodgkins lymphoma, have a propensity for cervical lymph nodes in this age group. Long-term complications of tonsillectomy such as peritonsillar abscess are rare yet warrant consultation with an otolaryngologist.

The discussant begins by constructing an initial problem representation (PR), or streamlined summary statement that highlights the defining features of a case. It includes the who, when, and what of the patient’s presentation.1 A fundamental step in creating her PR involves abstracting patient-level data to something more useful to guide her clinical reasoning. For example, she translates neck swelling to “mass” and subjective fever to “inflammation.” This allows her to make some initial progress toward establishing a provisional diagnosis as she searches for other, more specific footholds to move the case forward.

On arrival, she had a temperature of 39.3 °C, heart rate of 123 beats per minute, blood pressure of 90/63 mmHg, respiratory rate of 14 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 97% on room air. She appeared in no distress. Her oropharynx was clear. Nontender lymphadenopathy was noted in the left posterior cervical, left submandibular, bilateral occipital, and left axillary areas, the largest node being ~2.5cm. Cardiopulmonary examination was normal except for tachycardia. Abdominal and dermatologic examinations were unremarkable.

This patient’s vital signs invoke urgent consideration of septic physiology and empiric treatment with antimicrobials. However, in a young woman with low BMI without symptoms of hypoperfusion, this blood pressure reading could represent her baseline. The fever and weight loss confirm the concern for a systemic inflammatory syndrome while the neck swelling is further classified as lymphadenopathy (LAD). As the systemic inflammatory syndrome is non-specific, placing more cognitive energy on LAD to start will likely allow for greater diagnostic progress.

The first step in evaluating a patient with LAD is to characterize it as localized or generalized. Localized LAD warrants focus on a specific region of the body based on lymphatic drainage patterns, whereas generalized lymphadenopathy reflects a systemic disease. The larger size (2.5 cm), time course of >6 weeks, and generalized distribution increase risk for a metastatic malignant process. Given her age, weight loss, and evidence of inflammation, liquid malignancies are favored. While concern for malignancy often takes center stage in evaluation of LAD, in a young woman with a subacute to chronic systemic inflammatory syndrome, ruling out infectious processes as mentioned previously and consideration of autoimmune etiologies, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), adult-onset Still’s disease, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and SLE-like Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KFD), is warranted.

The discussant further abstracts the “neck mass” to LAD as she attempts to more accurately define the clinical syndrome. She makes a point to distinguish generalized from localized LAD and to define the time course as “subacute to chronic.” In doing so, she adds further specificity to her PR. Utilization of this more abstract, paired/opposing descriptor, called a semantic qualifier, is an important clinical reasoning concept that helps to further hone one’s problem representation.2 While “localized LAD” is far more specific and constrained than “neck mass,” the number of diagnostic possibilities is numerous. A strategy she employs is to link localized LAD with inflammation in an attempt to triangulate between the various diagnostic footholds and ultimately make more nuanced diagnostic progress. The question will eventually become, however, whether she can find a more specific element to incorporate into her PR.

A complete blood count (CBC) with differential demonstrated a white blood cell count (WBC) of 1810 per cubic millimeter (normal 4000–11,000) with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 660 per cubic millimeter (normal 1500–7400), absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) of 990 per cubic millimeter (normal 1100–3900), hemoglobin of 11 g/dL (normal 12–15), and normal platelet count. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 765 U/L (normal 125–220), sedimentation rate (ESR) >130 mm/hr (normal 0–20), and C-reactive protein 5.3 mg/L (normal <5.0). Liver tests, basic metabolic panel, creatine kinase, and lactate were normal. Computed tomography of the neck with contrast was done and showed extensive cervical LAD (largest node measuring 21×17×42mm) and left axillary LAD. Chest X-ray showed no radiographic abnormalities. Blood cultures were collected and IV doxycycline was given.

Leukopenia can suggest an underlying congenital condition (e.g., benign familial leukopenia), HIV, medication side effect, or sepsis physiology. In absence of these, framing leukopenia as a feature of this patient’s inflammatory LAD will allow us to further the diagnostic process. That being said from a management standpoint, if the neutropenia persists, it could further predispose the patient to infection and require a change in antimicrobial strategy.

LAD in the presence of fever, weight loss, and elevated LDH is highly concerning for liquid malignancy. A timely biopsy and consultation with a hematologist is recommended. From a diagnostic reasoning perspective, the presence of leukopenia is intriguing. Liquid malignancies such as large granular lymphocyte (LGL) leukemia and CLL can present with leukopenia, yet her age makes these two entities less likely. While lymphopenia is often seen in a variety of lymphomas, leukopenia would be rare.

The challenge of this diagnostic scenario is to define whether this is an atypical presentation of a common disease or a typical presentation of a rare disease. For example, KFD, or histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, is a rare disease seen in young women presenting with fever and cervical LAD. Common lab abnormalities include leukopenia, anemia, and elevated ESR. A timely excisional lymph node biopsy is key to diagnosing KFD as its presentation can mimic other diseases including infections (e.g., TB lymphadenitis, cat scratch disease), lymphomas, and autoimmune diseases (e.g., Sweet’s syndrome, Still’s disease). Furthermore, KFD can be associated with SLE, so further serological workup for SLE is warranted.

Initial laboratory findings allow the clinician to begin listing diagnostic possibilities. In particular, she focuses on leukopenia, which she eagerly incorporates into her evolving diagnostic scaffolding. Whereas much has been written about the concept of the “pivot point” (a finding so specific, relevant, and abnormal in the context of the case that it alone can guide the differential diagnosis), she appears to be embracing various diagnostic footholds (e.g., localized LAD, inflammation, and now leukopenia), much as a rock climber cautiously tries out different perches before launching herself forward.3 Such “footholds” could be likened to the classic pivot point but, instead, can be used in conjunction with each other, rather than alone, to advance the diagnostic process. Our discussant is now narrowing in on a far more limited set of diagnostic possibilities as she feels more firmly supported by the foundations of her PR.

Additional investigation was pursued. EBV viral capsid Ag (VCA) IgM and EBV EBNA-1 IgG were positive. EBV PCR was negative. CMV IgG was positive but CMV IgM was negative. HIV 1 and 2 Ag/Ab as well as PCR were non-reactive. Quantiferon TB was negative. She had negative toxoplasma IgM and IgG antibodies. Testing for gonorrhea, chlamydia, Rickettsia typhi, syphilis, and West Nile virus was negative. An ANA returned positive (titer 1:160, homogeneous pattern), but dsDNA antibody, SSA/SSB antibodies, and rheumatoid factor were negative. Review of her blood smear showed neutropenia with a few pseudo Pelger-Huet cells and mildly increased granulations as well as a few large granular lymphocytes (Fig. 1). Blood cultures showed no growth to date. After multidisciplinary discussion, antibiotics were held and the patient was trialed on symptom guided management.

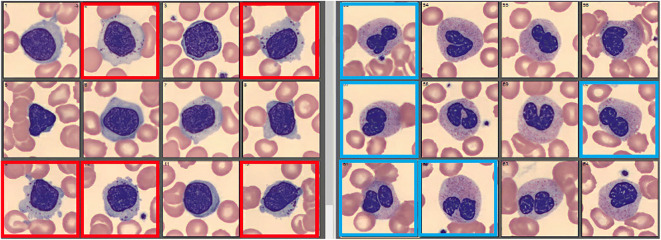

Figure 1.

Selection of white blood cells from peripheral blood smear. Squares outlined in red note large granular lymphocytes. Squares outlined in blue note pseudo Pelger-Huet cells (neutrophils).

Clinical context is key in interpreting EBV serologies. While a positive VCA IgM is often suggestive of acute EBV infection, other herpes viruses and any disease causing strong immune activation can lead to detectable VCA IgM levels. In the presence of EBNA-1 IgG and a negative EBV PCR, this serological profile most likely indicates a past EBV infection rather than an acute infectious mononucleosis. Negative HIV immunoassay and PCR testing in this patient with 6 weeks of symptoms argues against acute HIV. While the quantiferon is negative, tissue culture would be needed to rule out TB in this case. Lack of response to doxycycline lowers concern for cat scratch disease and other “doxy deficient” infections. Involving the infectious disease specialists would be paramount to confirm accuracy in interpretation of these studies as well as obtain guidance on any further testing.

A negative dsDNA in a patient with a positive ANA and moderate clinical suspicion lowers concern but does not eliminate the possibility of SLE. Pseudo Pelger-Huet anomaly is an acquired neutrophil dysplasia that can be seen in MDS, myeloproliferative disorders, with certain medications (e.g., immunosuppression, ibuprofen), and acute infection/inflammation (e.g., TB). LGL make up about 10–15% of peripheral lymphocytes. If LGL expansion is present, whether it is polyclonal or monoclonal would be informative. Polyclonal expansion can be seen in viral infections and autoimmune diseases while monoclonal expansion is concerning for leukemia.

Due to the stability of her diagnostic scaffolding, she is able to quickly and efficiently evaluate numerous laboratory results without expending too much cognitive energy. While she acknowledges their potential relevance to the case, she is able to reason that they are best viewed as negative or neutral findings that help strengthen the non-infectious considerations in her differential diagnosis. This successful streamlined review of complex laboratory data is predicated on the establishment of an effective problem representation.

Despite aggressive supportive care with IV fluids and anti-inflammatories, she continued to have febrile episodes (up to 39°C) and developed worsening fatigue and malaise. Repeat labs showed CBC with differential with WBC 2300 per cubic millimeter with ANC 1000 per cubic millimeter and ALC 600 per cubic millimeter, hemoglobin 8.7 g/dL, normal platelet count, LDH 888 U/L, C-reactive protein 11.3 mg/L, and hepatic panel with ALT 201 U/L (normal 10–50), AST 182 U/L (normal 10–50), and normal bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase. Blood cultures continued to show no growth. Acute viral hepatitis panel was negative. CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast showed no hepatosplenomegaly or other beds of LAD outside the neck.

This is a young woman who presented with prolonged fevers, painless neck swelling, and weight loss who is found to have an inflammatory cervical LAD syndrome with leukopenia without improvement on antibiotics with largely negative workup for infectious and autoimmune etiologies.

The duration of symptoms and negative workup so far makes infectious etiologies less likely with the exception of TB and fungal pathogens. Further evaluation for leukemia with flow cytometry, in the setting of an abnormal blood smear, is warranted. Although lymphomas often present with splenomegaly, normal spleen size does not lower concern for lymphoma. Her worsening hepatocellular pattern of liver injury most likely reflects parenchymal pathology that can accompany liquid malignancies and can also be seen in KFD.

The patient remains symptomatic with this febrile cervical LAD syndrome, yet the lack of progression of the disease itself (e.g., extension of LAD) and lack of complications (e.g., other vital signs abnormalities, tumor lysis syndrome) are noteworthy and can be seen in both Hodgkin’s lymphoma and KFD. At this time, excisional biopsy of one of the affected lymph nodes would be the most informative to distinguish between these entities.

The discussant updates her problem representation. In particular, she adds time course and lack of response to antimicrobials to leukopenia, cervical LAD, and systemic inflammation, allowing her to elaborate her diagnostic scaffolding without having to rebuild it. This leads her to prioritize malignant and autoimmune processes as well as decipher the liver tests abnormalities as likely noise.

Excisional biopsy of a left cervical lymph node was performed. Lymphoma FISH panel as well as flow cytometry were normal. Pathology showed extensive areas of necrosis containing karyorrhectic debris without inflammatory cells and an infiltrate of histiocytes in addition to variably sized lymphoid cells surrounding the necrosis (Fig. 2). Microbial staining and cultures were negative.

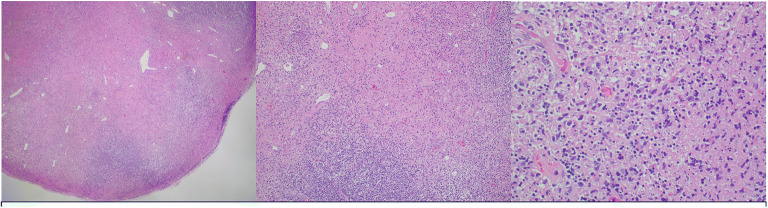

Figure 2.

Hemotoxylin and eosin stained slides show extensive areas of necrosis containing karyorrhectic debris without inflammatory cells. Surrounding these areas of necrosis there is an infiltrate of histiocytes with variably sized lymphoid cells. From left to right, magnification is 40×, 200×, 400×.

The presence of necrosis with histiocytes as the major cell type and lack of infiltration by inflammatory cells point to the diagnosis of KFD. The lack of neutrophilic infiltrate during the necrotizing phase of the disease is helpful in distinguishing it from other causes of lymphadenitis. Immunohistochemical staining can further confirm the diagnosis.

The discussant began the case by translating non-specific subjective concerns (neck swelling, fever, weight loss) into recognizable conditions for which diagnostic schema could be activated (inflammatory syndrome with localized lymphadenopathy). From here, she was able to reason through a significant number of objective data points and changes in clinical status to pick sound footholds and ultimately develop unwavering stability on the diagnostic scaffold. With this strong platform, she was able to translate the final aliquot with ease into a final diagnosis.

These findings were consistent with KFD. She was discharged with supportive care and on follow-up 6 weeks later, she was feeling improved and her labs were largely back to baseline.

DISCUSSION

Histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, also known as KFD, is a rare, idiopathic, largely self-limited disorder that typically presents with cervical lymphadenopathy and fever.1,2,4,5 Since it was first described in 1972, only a few thousand cases have been reported.2 Based on clinical reviews, KFD appears to affect patients worldwide, has a slight female predominance, and most commonly affects adults in their third decade of life. Although the exact pathoetiology remains unclear, KFD is thought to be an autoimmune process triggered by one or more unrecognized agents. In particular, the role of certain viruses, such as EBV herpesvirus, parvovirus B19, and cytomegalovirus, has been considered; however, definitive evidence is lacking.1,2,5

As seen in this case, the prevailing features of KFD include cervical lymphadenopathy, with posterior cervical node involvement being most common, fever, night sweats, and other non-specific symptoms such as malaise, fatigue, nausea, and headache. Laboratory features include leukopenia and elevated inflammatory markers, though these are non-specific. Although cytology from fine needle aspiration can be suggestive, excisional lymph node biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis.1,2,4,5

Management is centered on supportive or symptom-driven care, including analgesics and antipyretics, as symptoms typically self-resolve within 1 to 6 months. Corticosteroids may benefit patients with severe symptoms unresponsive to supportive care though data is largely anecdotal.1,2,5 Awareness of KFD is of important clinical significance as it may help to streamline workup, minimize exposure to high-risk empiric therapies, and lead to early excisional lymph node biopsy. Not only does this confirm the diagnosis but it also serves as an effective way to distinguish KFD from other diagnostic considerations including lymphoma, tuberculosis, and other indolent infections.

The diagnostic reasoning process is complex. When faced with atypia or information overload, having a sound approach to depend on can help simplify the exercise. In this report, we highlight the concept of diagnostic footholds. These are features of the case that the clinician grips on to and subsequently builds diagnostic possibilities from.

Previously discussed in this journal platform is the concept of a pivot point, representing the prototypical example of an objective clinical finding around which to frame one’s differential diagnosis. From these pivot points, a cluster of alternative but related diagnoses can be generated.3 While a pivot point can be likened to a foothold, it is slightly less dynamic in that while the cluster around a pivot point is singular diagnoses, the diagnostic considerations around a foothold can be a framework (e.g., I-MADE mnemonic for systemic inflammation, which stands for infection, malignancy, autoimmune, drugs, endocrinopathy), individual diagnoses, or somewhere in between depending on how deep into the reasoning exercise the clinician is. Additionally, if the chosen foothold is felt to be incorrect at some point in the reasoning process, it can be abandoned without having invested significant cognitive energy into individual diagnoses which, theoretically, could help to limit bias.

Clinical Teaching Points

• KFD is an autoimmune condition that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a young patient with cervical lymphadenopathy and persistent fever.

• Laboratory studies tend to show nonspecific findings and excisional lymph node biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis.

• Treatment of KFD is mainly supportive as it is a self-limited disease. The role of steroids in the setting of persistent symptoms remains uncertain.

• Reasoning through a patient encounter is an interative process, whether in an artificial exercise or at the bedside. Each time new information becomes available, revisting the problem list and recognizing clinical syndromes, all in the background of the time course, is cruicual to make efficient progress toward an accurate diagnosis.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Problem Representation Overview. sgim.org,www.sgim.org/web-only/clinical-reasoning-exercises/problem-representation-overview. Accessed 31 Jan 2022.

- 2.Nendaz MR, Bordage G. Promoting diagnostic problem representation. Med Educ. 2002;36(8):760–766. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.May JE, Blackburn RJ, Centor R M, Dhaliwal G. Pivot and cluster: an exercise in clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):226–230. 10.1007/s11606-017-4216-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Bosch X, Guilabert A. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:18. 10.1186/1750-1172-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Deaver D, Horna P, Cualing H, Sokol L. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Cancer Control. 2014;313–321. 10.1177/107327481402100407. [DOI] [PubMed]