Abstract

Health system reforms across Africa, Asia and Latin America in recent decades demonstrate the value of health policy and systems research (HPSR) in moving towards the goals of universal health coverage in different circumstances and by various means. The role of evidence in policy making is widely accepted; less well understood is the influence of the concrete conditions under which HPSR is carried out within the national context and which often determine policy outcomes. We investigated the varied experiences of HPSR in Mexico, Cambodia and Ghana (each selected purposively as a strong example reflecting important lessons under varying conditions) to illustrate the ways in which HPSR is used to influence health policy. We reviewed the academic and grey literature and policy documents, constructed three country case studies and interviewed two leading experts from each of Mexico and Cambodia and three from Ghana (using semi-structured interviews, anonymized to ensure objectivity). For the design of the study, design of the semi-structured topic guide and the analysis of results, we used a modified version of the context-based analytical framework developed by Dobrow et al. (Evidence-based health policy: context and utilisation. Social Science & Medicine 2004;58:207–17). The results demonstrate that HPSR plays a varied but essential role in effective health policy making and that the use, implementation and outcomes of research and research-based evidence occurs inevitably within a national context that is characterized by political circumstances, the infrastructure and capacity for research and the longer-term experience with HPSR processes. This analysis of national experiences demonstrates that embedding HPSR in the policy process is both possible and productive under varying economic and political circumstances. Supporting research structures with social development legislation, establishing relationships based on trust between researchers and policy makers and building a strong domestic capacity for health systems research all demonstrate means by which the value of HPSR can be materialized in strengthening health systems.

Keywords: Health policy and systems research, Mexico, Cambodia, Ghana

Key messages.

Health policy and systems research (HPSR) has emerged as a field that aims to generate and document contextually specific evidence regarding what policies (and policy content) are most appropriate and most effective in achieving health and health systems’ goals in a given setting.

-

HPSR, and specifically the use of evidence in policy formation, is influenced by contemporary yet historically determined factors that are both external (e.g. how the health system functions within a given economic and political context) and internal (e.g. the purpose of HPSR in a given setting as well as the process itself and the participants) to the policy development process.

Building HPSR capacity can improve a nation’s ability to: (1)

-

∘

develop sustained, integrated and context-based, national health-system responses to local health challenges, and cumulatively monitor and evaluate them; (2)

-

∘

support the implementation of interventions based on evidence obtained from abroad and locally, together with critical appraisal and appropriate adaptation to ensure their local suitability, feasibility and utility.

HPSR is crucial to policy development while recognizing that researchers and research institutes are one part of a larger process characterized by multiple stakeholders, all with particular interests. The role of HPSR in the policy process is most effective, and most efficient, where the research component is embedded within the wider health system.

Introduction

In recent decades, Health Policy and Systems Research (HPSR) has emerged as a field that generates effective policies and policy content for achieving health and health system goals (see Shroff et al., 2017). Health systems are influenced by local and international political, social and economic factors, and health policy must be based on evidence specific to the national context (Bennett et al., 2011; Norris et al., 2019). Local ownership and embedding of HPSR in health system processes are a catalyst for research uptake (Koon et al., 2013; Vanyoro et al., 2019). HPSR investigates both contextual variables and stakeholder interests (see Sheikh et al., 2014; Ghaffar et al., 2017), generates the data needed for effective interventions (see Dobrow et al., 2004; Sheikh et al., 2014; George et al., 2019; Schleiff et al., 2020) and encompasses a broad view of health and of the determinants of health, as recognized in the Sustainable Development Goals (Peters, 2018; Vanyoro et al., 2019).

Dobrow and colleagues suggest that context is a critical factor in evidence-based health policy and that it is more critical to understand how evidence is utilized than how it is defined (Dobrow et al., 2004). The purpose of the study was therefore to generate insights into the issues that affect the practice of HPSR through the analysis of three different, indicative country settings: Mexico, Cambodia and Ghana. The three countries were purposively selected (see Case selection below) as they illustrate conditions across three different continents, each operating under different economic and political conditions, each adopting HPSR in different ways and each with different levels of achievement.

Mexico is a democratic federal republic comprising 31 states and the Federal District. The health system was established with the provision of healthcare to workers at the time of industrialization, and public health initiatives emerged in the 1920s to address infectious diseases after the national revolution (Birn, 2006; González-Block et al., 2020a). Services are provided at national and state level through social health insurance for the formally employed, government-funded care for the uninsured and a growing private sector (Laurell, 2015a; Urquieta-Salomón and Villarreal, 2016; Parker et al., 2018; Reich, 2020; González-Block et al., 2020a). Mexico invested comparatively early in HPSR structures, fostered close relationships between researchers and government, and appointed researchers to senior policy positions. The governing 1983 General Health Law and subsequent legislation provided the foundation for the role of HPSR in health-policy making, within the context of frequently changing political circumstances and priorities.

Cambodia is a small, post-conflict, lower-middle-income country in Southeast Asia experiencing relative stability and strong economic growth since the 1990s. Cambodia faced the challenge of rebuilding its social and economic structures in the aftermath of its prolonged conflict (Mam and Key, 1995; Annear, 1998). Following the peace agreements of 1989, almost all funding for infrastructure and health-system initiatives came from donor-funded programmes, while the Ministry of Health (MoH) carried the responsibility for planning, staffing and service delivery (World Bank, 1994). Over time, the financial and human-resources capacity of the MoH has increased and the role of international partners has receded, although it remains strong. For 20 years from the mid-1990s, donors and government combined to pilot and evaluate ad hoc, experimental health system activities (Chhun et al., 2015), and the MoH looked for evidence to identify the most effective innovations (ERC1, expert respondent 1 from Cambodia) (Ministry of Health, 2008; Walls et al., 2017). Currently, Cambodia has a three-tiered (national, provincial, district), decentralized, government health service and a large but disparate private sector; the government funds ∼40% of total health expenditure (Annear et al., 2015). Cambodia’s health system and HPSR capacity grew organically in the post-conflict period from the early 1990s, based on a strong partnership between individuals in government, international donors and researchers.

Ghana is a lower-middle-income country in West Africa with a unitary constitutional democracy. In the 1970s and 1980s, Ghana experienced frequent military unrest and government changes affecting the economy and public services (Aikins, 2016; Aikins and Koram, 2017). With increasing stability, reforms began within the MoH in 1995 (Adua et al., 2017). Significant health and health-system gains were made from 2000 under the government’s Poverty Reduction Strategy, including the establishment of the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) in 2003 (Aikins and Koram, 2017; Micah et al., 2019; World Health Organization, 2019). Ghana faces new health challenges due to rising costs of healthcare, a multiple disease burden including increased incidence of non-communicable diseases, poverty and economic constraints (Aikins, 2016; Adua et al., 2017). Ghana embedded HPSR in routine government operations from the 1980s, enabling an accumulation of evidence that served to inform national and sub-national decision making; domestically generated research provides a strong local dimension alongside the activities of international development partners.

Methods

We drew on data from a review of the literature and semi-structured interviews in two rounds with strategically placed experts to construct three country case studies (see Scholz and Tietje, 2002). We made a cross-case comparison to identify similarities and differences and lessons learned. Central to our approach was iteration between the data generated from the literature and from the experts interviewed before synthesizing our findings. Where expert opinion appears in the text, we have cited this as ER (expert respondent) with M, C and G representing the three countries and a number according to respondent.

Analytical framework

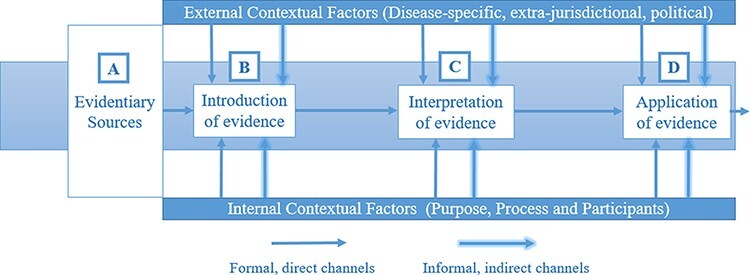

We adopt the concept of ‘evidence-informed policy’ with an understanding that health-systems are complex adaptive systems operating within a context that is marked by national needs and priorities. While the concept of ‘evidence-based policy’ may be appropriate for clear-cut clinical concerns, HPSR faces a more complex environment, one affected by constantly changing external and internal factors (see below), and requires a more holistic approach. The conceptual framework developed by Dobrow and colleagues was modified and used to guide our approach, data collection and analysis (Dobrow et al., 2004). As illustrated in Figure 1, this framework identifies four critical junctures in the use (or non-use) of evidence for decision making. It starts with sources used (A), before examining the process through which these sources of evidence are introduced (B), interpreted (C) and applied (D). Critically, it recognizes both external and internal contextual influences on the evidence cycle: ‘external contextual factors’ lie outside the influence of those directly involved in evidence-informed decision-making processes (e.g. national economic, structural and political processes); ‘internal contextual factors’ operate as a function of the parties directly involved (e.g. the individuals and institutions themselves, their purpose and approach).

Figure 1.

Analytical framework for context-based, evidence-based decision making (Dobrow et al., 2004)

Case selection

Mexico, Cambodia and Ghana were purposively selected as case studies because they have each been, in various ways, early adopters of HPSR and provide diverse examples of HPSR development and implementation. The three countries have unique and interesting characteristics that make them the primary subjects of the study. The policy process and HPSR in Mexico have been essentially top down, national in scale, supported by legislation and inevitably influenced by political decision making; the Seguro Popular reform of social health protection measures (now superseded) was supported by increased total health expenditure equal to 1% of gross domestic product (GDP). While published research on the Mexican reform process is extensive (see González-Block et al., 2020a, for a recent summary), much less is available on the influence of political decision making affecting the replacement of the Seguro Popular reform and the contested use of HPSR by different actors.

In Cambodia, the HPSR process has been essentially bottom-up and organic, relying mainly on the participation of international donors and researchers working in close collaboration with the MoH and its agencies. Significant HPSR activities were translated into policy through the strategic planning process, based on the close (informal) working relationships between researchers and policy makers (Ir et al., 2010; RDI Network, 2017). In tight economic and fiscal circumstances, targeted national funding for ongoing HPSR has not been available. More recently, less attention has been given in the published literature to understanding the development of Cambodia’s HPSR system.

In Ghana, HPSR was embedded into routine government operations as early as the 1980s, enabling managers of the health system to use an accumulating evidence base to direct and refine innovations in health-financing, maternal-health and human-resources policy. The Kintampo, Dodowa and Navrongo Health Research Centres have, with public funding and longstanding collaborations with foreign research institutes, produced evidence commonly discussed and utilized in Ghanaian health policy fora. Evidence generated in part from studies of community-based health insurance conducted by the Ghana Health Service (GHS)’s Dodowa Health Research Centre provided the foundation for establishment of Ghana’s NHIS (which emerged following political campaign promises) (Aikins and Koram, 2017). The domestic origins of this policy, combined with commentary regarding the enduring influence on health policy of foreign development partners over time, make Ghana a nuanced setting for the appraisal of HPSR (Aikins and Koram, 2017).

Please refer to the supplementary file for the approach taken to data collection and analysis.

Limitations

In implementing our study, we faced two main limitations. First, the topic of enquiry is large, contested and affected by context. Our expert respondents were used not to survey the field of practice in each country but rather to provide specialist insight on the findings from our literature reviews. While the number of expert respondents was limited, we targeted those best-placed to provide their intimate knowledge of the issues under consideration; this generated important points of agreement at country level and when analysing across settings. It also oriented our literature review towards their perspectives and experience, albeit through the authors’ interpretive lens rather than through a systematic approach. Secondly, under conditions created by a global pandemic, our research could not include extensive field work or consultation with a wide range of local officials and experts. In studies of this nature, local expertise is invaluable, and we made efforts to draw on those with longstanding experiential insights into the national context (including among the authors).

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Ethics Sub-Committee at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, Human Ethics Advisory Group at the University of Melbourne, Australia (Ethics ID: 2057979.1). This article is based on a more extensive research report delivered to the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization; the report may be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Results

Mexico

HPSR development in Mexico

Mexico has a long history of public health research, and since the 1980s has institutionalized HPSR training and capacity, following a largely Mexican-led research agenda. The School of Public Health of Mexico (ESPM), established in 1922, and the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) are the seminal teaching and research institutions, together with the Autonomous Metropolitan University (UAM), which has a social medicine postgraduate programme (ERM1). The National Institute of Public Health (INSP) was established in 1987 as a confederation of various research institutes and today houses the majority of HPSR researchers; ESPM merged with INSP in 1995 as part of a strategy to integrate quality academic training and research generation (González-Block, 2009).

Among the wider HPSR community, The Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS), the main social health insurer and significant health care provider, produces considerable health service delivery research, although not research on health system development or universal health coverage (ERM1). The public universities and some private universities and smaller foundations also produce HPSR (ERM1). A study examining HPSR publication trends from Latin America, including Mexico, indicated an average annual growth of 27.5% in HPSR papers between 2000–2018, where the global increase over the same period was 11.4% (González-Block et al., 2020b).

At the centre of this upsurge in HPSR publications was the assessment and promotion of the nationwide Seguro Popular national health insurance programme introduced in 2003, funded by an increase in the health budget equal to 1% of GDP. An extensive debate followed, much of it recorded in the pages of The Lancet (for example, see LANCET, 2006). On one side were the designers and promoters (Frenk, 2006), who documented the need for and the effectiveness of the scheme; on the other side were the critics (Laurell, 2007; 2015a), who emphasized the shortcomings of the programme, which did not achieve universal coverage. This rich discussion of policy options for improved health coverage paved the way first for the introduction of Seguro Popular and later for its replacement. A similar experience was evident in the introduction of the 2014 sugar-sweetened beverage tax. The literature underlying these policy discussions is further discussed below.

Significant events in the development of HPSR capacity

The appointment of Guillermo Soberón as Minister of Health during 1982–1988, a doctor and highly regarded academic from UNAM, saw health reform placed on the agenda and HPSR supported by decision makers. Research capacity then grew steadily, producing a close relationship between HPSR researchers and the Federal MoH (ERM1, ERM2) (González-Block, 2009). The inter-disciplinary range and balance of HPSR during this period expanded beyond the boundaries of public health, particularly incorporating health economics, psychology, sociology and anthropology (ERM1, ERM2).

As health minister, Soberón secured the social right to health care through constitutional amendment, passed the General Health Law, instigated development of HPSR institutions and championed evidence-informed health reforms In 1984, the Centre for Public Health Research (CISP) was established within the MoH with Julio Frenk (who was later to become Minster for Health during 2000–2006) as founding director, with funding largely from foundations and international organizations (Frenk et al., 1986; Bobadilla et al., 1989; ESPM, 2009). CISP was then incorporated into INSP in 1987. In 1985, the Mexican Health Foundation (FUNSALUD) was established as a private, not-for-profit, evidence-based policy think-tank funded largely by transnational corporations. FUNSALUD established a strong relationship with INSP and mobilizes the private sector (González-Block et al., 2020a).

In 1996, the Centre for Health Systems Research (CISS) was established within INSP, and by the early 2000s the national infrastructure to produce, fund and regulate HPSR, with close institutional relationships, was in place (González-Block, 2009; Oxman et al., 2010; Martínez-Martínez et al., 2012). Under the 2002 Law for Science and Technology, a number of public health insurance institutes were established along with the National Council for Science and Technology (CONACYT), an organization that regulates trust funds in specific areas including health research (Martínez-Martínez et al., 2012). Public entities, primarily federal and state ministries of health, contribute to these pooled funds (González-Block et al., 2020a). The evaluation of social development policies (including health) was mandated by the 2004 General Social Development Law, which established the autonomous National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL) (Oxman et al., 2010; Valle, 2016).

Political will and contextual influences on HPSR

The political environment has had a major (although inconsistent) impact on health and health-research policies in Mexico, characterized by an often close relationship between research and decision makers (ERM1, ERM2). During Frenk’s tenure as Minister, the institutional structures supporting HPSR played a major role in developing and monitoring a programme of health system reforms headlined by the 2003 creation of the Seguro Popular, designed to provide coverage to those previously excluded from health insurance (Frenk, 2006). Demonstrating international recognition of these achievements, the reforms were promoted in a Lancet series, with key contributions authored by the leading individuals in this network of institutions (LANCET, 2006).

Domestically, however, the close network of relationships between stakeholders in government, the research community and private industry that produced this research evidence have been the subject of scrutiny and criticism. The independence of the research agenda, the evidence generated and its interpretation have all been questioned (Lakin, 2010) and at times critiqued as one part of a neo-liberal enterprise spanning three decades (Laurell, 2007; 2015a; 2015b; Homedes and Ugalde, 2009). Critics have, for instance, noted the influence of industry in blocking a larger-scale and more progressive reform than the Seguro Popular that had aimed to create a universal health insurance system (ERM1).

In following years, under a new government, relationships between different parts of the health research community were strained, particularly as tensions rose between industry-based research interests and the HPSR and public-health institutions. For example, close relations between INSP and FUNSALUD were strained when FUNSALUD was seen to have supported contradictory evidence related to non-communicable diseases and the obesity epidemic (ERM1) (Barquera et al., 2013; Turnbull et al., 2019; Barquera and Rivera, 2020). Tensions reached a peak over enactment of the 2014 sugar-sweetened beverage tax after a long period of contestation pitting the beverage industry against the public-health and HSPR communities (Fuster et al., 2020). In the debate over policy, both industry and health researchers engaged in evidence production and interpretation (Gómez, 2019; Carriedo et al., 2020; James et al., 2020; Ojeda et al., 2020).

The current centre-left government has restructured and reduced the volume of research funding, and some of the trust funds have been disbanded. In 2020, it replaced Seguro Popular (calling it a foreign, neo-liberal initiative) with a return to a centralized health system with public financing and service delivery and reduced private participation, justified as a move towards universal health care (Argen, 2020). Reich (2020) interprets this as a pro-statist and anti-market bias, in contradiction to current global health system trends. Widespread recognition of the persistent inequities in health care and health financing under Seguro Popular were also evident. According to one view, evidence is often used in support of political decisions based on values rather than science, just as true for the introduction of Seguro Popular (under Frenk) as for its recent disbanding; this was not seen simply as an ideological issue, as all policy making is inherently political (ERM2).

Cambodia

Organic development of HPSR

The development of HPSR capacity has largely been informal and organic, in step with the experimentation occurring within the public health system. Two major interventions that received considerable attention were health equity funds for the poor and the contracting of government health services (see Annear, 2010; Khim et al., 2017; Annear et al., 2019). In general, much of this activity was carried out by international and local researchers (non-government organizations, donor partners, research institutes) working in close partnership with the MoH and its newly-founded National Institute of Public Health (NIPH). Externally initiated research is welcomed by government when it focuses on established health priorities (ERC1).

This work was accompanied by a growing body of published literature on health systems, health care and the evidence-to-policy process (see Ir et al., 2010; Goyet et al., 2015; RDI Network, 2017; Liverani et al., 2018; Witter et al., 2019). Research carried out by and with local institutions, supported by international agencies, played a major role in informing MoH and government decision making, including the adoption of the health equity fund model, abandonment of official community-based health insurance and modifications to the contracting model (see e.g. Ir et al., 2010; RDI Network, 2017). This process has also contributed significantly to the formation of a new generation of qualified Cambodian researchers, although in limited numbers. Research capacity has grown through the NIPH, the University of Health Sciences and some non-government research organizations (such as the Cambodian Development Resource Institute, the Reproductive Health Association of Cambodia; see e.g. NIPH, 2015). Nonetheless, following the period of experimentation, the number of HPSR activities has fallen, and the challenge of institutionalizing HPSR remains; often, policy development moves ahead more quickly than does the capacity to generate evidence (ERC1).

Officials in the MoH and the NIPH are conscious of the need to build permanent in-house research capacity, although funding and human resources are especially constrained (ERC1). An informal health system researchers’ forum was convened in 2015 (NIPH, 2015), and in 2018 the NIPH and MoH initiated thinking (in collaboration with international research partners) about a national agenda for heath-systems research at an inaugural workshop (NIPH, 2018) (ERC1). Research personnel with the expertise, time and resources are needed, although Treasury has yet to commit the targeted funding required (ERC1). The challenge of putting HPSR at the centre of the national health agenda and budget remains (Goyet et al., 2015; Liverani et al., 2018).

Significant events in the development of Cambodian HPSR capacity

In an environment rich with donor activities and health system experimentation, HPSR emerged largely as a partnership activity between the MoH, local researchers and international agencies, in which the results of evaluation and research provided input to the national health planning process, characterized by the MoH’s successive national health strategic plans. The policy outcomes often followed vigorous debate among partners on the meaning and significance of research outcomes. The most conspicuous reforms to travel this path were the health equity funds (HEF) and contracting of government health service delivery. HEFs emerged from 2000 as district-level donor-non-governmental organisation (NGO) projects to fund user-fees for the poor, accompanied by a growing body of research (for a summary, see Annear, 2010; Annear et al., 2019). The evidence was influential (ERC1); the HEF was scaled-up to national population coverage of the poor and became a central part of the Government’s National Social Protection Policy Framework 2016–2025 (see Chhun et al., 2015).

Contracting of government district-health service delivery to NGOs was first piloted by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in five selected districts in 1997, and internal ADB research suggested it improved elements of service delivery (despite limitations in the research design) (see Bloom et al., 2006; Lagarde and Palmer, 2009). At the same time, traditional methods of NGO support for MoH district health services achieved (in some cases) equally good results. Because the MoH took responsibility for service delivery, it was reluctant to hand over domestic and donor funding to NGOs. The contracting model evolved over three phases (Khim et al., 2017): (1) 1997–2002, the ADB pilot study; (2) 2003–2009, a ‘hybrid’ model; and (3) from 2009, an ‘internal’ contracting model in which higher levels of the MoH structure ‘contracted’ service delivery to lower levels as one part of a government-wide administrative reform known as Special Operating Agencies. In this case, national imperatives related to the affordability of contracting, and MoH concern that donor funding it expected to receive for service delivery may be allocated instead to NGOs, prevailed. The internal contracting model is being gradually scaled up.

Institutional and structural developments conducive to HPSR include an improved health information system, increased availability of surveys and research products, the existence of participatory mechanisms in which evidence can be presented to local and international stakeholders and improved channels for the circulation of evidence across the MoH (Liverani et al., 2018). Regular Technical Working Group for Health meetings have brought together MoH and donor officials, although, at times, policy discussions have been constrained (Wilkinson, 2012). Established in 1997, the NIPH has, alongside its principal laboratory functions, developed public-health and health-systems research and teaching functions funded through the health budget together with donor support. Periodic demographic and health surveys have been carried out since 2000, providing data on population health, health status and health-seeking behaviours, referred to in some cases as the most important evidence for health policy (Liverani et al., 2018).

HPSR activities have progressed mainly through the building of relationships between the main actors in the MoH and government services and those from international agencies and research institutes. With the focus shifting more recently to scaling up of proven interventions, research activities have somewhat receded and domestic HPSR capacity and career opportunities remain modest (ERC1).

Political will and contextual influences on HPSR in Cambodia

Consistent economic growth, an expanding health budget and an ongoing process of government administrative reform all create the context in which various arms of government (Cabinet, Health, Finance) have both willingly moved to adopt policies confirmed by evidence (such as HEF) and made political decisions to modify the implementation of certain interventions in line with perceived national needs (as in the case of contracting). The imperative to reduce national poverty played a large role in generating political support for HEF expansion; a sentiment in favour of reinforcing government service delivery contributed to the move to internal contracting. The interpretation and application of research evidence has, in various ways, reflected prevailing conditions related to the role of donors, the perceived needs of the Cambodian government and the relationships developed between local and foreign stakeholders. More recently, the policy-making process has increasingly been characterized by the broader process of government administrative reform, the role of the Council of Ministers (national cabinet) in health policy-making and the increasing experience and capacity of the MoH. However, as health officials point out (ERC1), guidelines about the way in which evidence should be appraised and used in the policy process are lacking and the use of evidence varies depending on political will and the skills of individual managers.

Ghana

HPSR development in Ghana

The development of HPSR capacity in Ghana has run in parallel with structural reforms The 1990s were marked by key health reforms, including the 1997 launch of the rolling Five Year Program of Work that guides strategy and policy with regard to health service delivery and inauguration of the government’s development programme, Ghana: Vision 2020, which aspired to move the country to middle-income country status (attained in 2010) (Dovlo, 1998; Aikins, 2016; Aikins and Koram, 2017). These reforms created a platform for sustained progress in the generation and use of evidence for policymaking, including HPSR (Aikins and Koram, 2017).

Significant events in the development of Ghanaian HPSR capacity

Central to the development of HPSR capacity has been the establishment of training and evidence-generating institutions and their close relationship with stakeholders, including the MoH. Building on earlier initiatives in which district medical officers were sent overseas to gain a degree in public health (beginning in 1994, particularly to the UK), the School of Public Health at the University of Ghana has produced Masters of Public Health (MPH) graduates and continues to conduct collaborative research and academic teaching of HPSR for cadres in the MoH and its agencies, including the National Health Insurance Authority (Agyepong et al., 2015). An MPH from the School of Public Health was seen as critical for career progression within the MoH (ERG3). Other academic institutions—such as the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (founded 1959), the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration (founded 1961; university status 2004) and the University of Health and Allied Sciences (founded 2011)—have all contributed to HPSR capacity through practical training in evidence gathering and interpretation (ERG2, ERG3).

A strong foundation for domestic HPSR was built by the 1996 formation of the GHS in collaboration with the World Health Organization. The GHS was established as an autonomous agency under the MoH to deliver government health services while the MoH focused on policy-related endeavours. The GHS produces the bulk of domestic evidence related to health system development and has established three health research centres in different parts of the country at Dodowa, Kintampo and Navrongo (Aikins, 2016). These centres, which carry out operational research and track health system performance (ERG2), have had an enduring influence.

Significant research findings from many of these institutions in the 1990s paved the way for the foundation of Ghana’s NHIS, including analyses of national health financing, cost-recovery initiatives, user fees and health seeking behaviours (Asenso-Okyere, 1995: Asenso-Okyere et al., 1998; Nyonator and Kutzin, 1999). The 2001 NHIS bill was based largely on evidence of community-based health insurance (CBHI) implementation in one district produced by the Dodowa Research Centre (Agyepong and Adjei, 2008). HPSR has been embedded in the NHIS to track its progress and support corrective actions (National Health Insurance Authority, 2013). The NHIS has an expert technical committee, led by a health economist, that collects and synthesizes evidence from various sources. For example, the delayed reimbursement of expenditures to health facilities necessitated out-of-pocket payments from clients and, reportedly, poorer quality of care, leading the committee to examine health sector expenditure review data and suggest a monthly payment schedule to facilities (National Health Insurance Authority, 2013; Dalinjong et al., 2017).

Strengthening the NHIS in terms of coverage, uptake and quality has been attributed, at least in part, to the perspectives, insights and contributions of a diverse range of researchers and research groups (Seddoh and Akor, 2012; Aryeetey et al., 2016; Alhassan et al., 2016a; 2016b; Aikins and Koram, 2017; Okoroh et al., 2018; Agbanyo, 2020). Academics, think tanks, professional associations, academic institutions and civil society organizations were reportedly engaged in the 2012 revision of the NHIS act, which drew on evidence related to improving NHIS financing mechanisms (Seddoh and Akor, 2012).

Another example is the 1999 Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) initiative, based on a Navrongo health research centre pilot study of community-level health service provision (ERG3) (Binka et al., 2007; Bawah et al., 2019; Kweku et al., 2020). The CHPS was ostensibly a national programme for universal access based on a ‘best practice model’ of community engagement and empowerment with task shifting to community health workers (CHWs). Even so, in common with other CHW strategies in Sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere, scale-up has been difficult (Perry et al., 2014; GHS, 2017). Health-systems challenges—including supply bottlenecks and issues of CHW support and performance specific to the operational setting—are central to the difficulties, causing a drift away from the intended community-based primary health care model (ERG3) (Bawah et al., 2019, Kweku et al., 2020). Consequently, the 2010 Ghana Essential Health Intervention Program (GEHIP) was launched to generate evidence (using an implementation science approach) for designing strategies to address the scale-up and sustainability of the CHPS (Awoonor‐Williams et al., 2016, Bawah et al., 2019; Kanmiki et al., 2019). The reported result was 100% CHPS population coverage achieved in target districts compared to ∼50% in non-GEHIP comparison districts (Awoonor‐Williams et al., 2016).

The revised Ghana National Health Policy, launched in 2020, emphasizes the need for strengthening research capacity, aiming, for example, to identify the key barriers to enrolment in the NHIS and to support evidence-oriented policy decision-making (Ministry of Health, 2020).

Political will and contextual influences on HPSR development and utility in Ghana

The GHS and the MoH both play an active role in promoting HPSR through the policy-making process in collaboration with major stakeholders. Personal contact between specialists at the GHS health research centres, MoH officials and the public health research institutions—such as the School of Public Health at the University of Ghana, the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration, the University of Health and Allied Sciences—remains the main means for processing research activities (ERG1, ERG2). Formally, evidence is channelled to the Policy, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation division of the GHS and to the Policy, Planning, Budgeting, Monitoring and Evaluation unit at the MoH. The GHS policy division operates as a conduit for the use of this evidence in the MoH’s decision making process. The MoH policy division gathers relevant evidence from routine health-services data, ad hoc evaluation reports and policy reviews.

The MoH leads the technical synthesis of existing evidence in collaboration with its local and international partners. As one part of this process, the MoH hosts annual 3-day summits with a topical theme where researchers convene with the MoH, NGOs, international development partners and other stakeholders to review the year past and plan for the year to come (Ministry of Health, 2021). The MoH also convenes technical working groups with invited specialists and health stakeholders that focus on speciality areas, such as health financing. The technical working groups introduce evidence to decision makers through formal and informal communication platforms, including the annual MoH summit.

As they provide significant financial and technical support for the delivery of various health services, international donor organizations continue to have a powerful influence on the strategic direction of the health system and the policy process, playing a key role in the annual health summit and the technical working groups. While local officials often see this simply as a funding-based reality (ERG1, ERG2, ERG3), there is also a feeling that priorities may sometimes be at odds with national needs. One example may be the perceived disproportionate investment in communicable disease control despite rising incidence of chronic and non-communicable diseases (ERG3).

Discussion

The various experiences of Mexico, Cambodia and Ghana demonstrate the value and the complexity of developing HPSR capacity and the use of evidence in policy-making. HPSR provides the foundation for sustained, integrated and context-based national health-system responses to local health challenges. Nonetheless, because health is a social and governmental issue, decision making about health policy generally takes place within an environment characterized by national needs, national objectives and political imperatives. The process of introducing, interpreting and applying evidence takes place within this context, characterized also by the activities of stakeholders and participants (Dobrow et al., 2004).

The conceptual framework developed by Dobrow and colleagues proved to be a useful tool for the analysis of the complex, contextually dependent story of HPSR in each of the case-study countries. The framework provided our starting point; in the process of synthesizing the lessons from each country, we used this foundation to move beyond the confines of the framework to identify the main themes arising from the data collected, including the critical influence of development partners and other international players in Ghana and Cambodia, and the level of maturity of the Mexican health research system. The framework itself is built on the understanding that there cannot be a linear progression across the domains, and these sorts of issues overlay the four domains (the source, introduction, interpretation and application of HPSR). Maintaining HPSR is a function not only of the initial investment in capacity but also of ongoing experience associated with policy-making influence. Our work demonstrates that the HPSR system is one element of broader policy networks, not a set of actors or activities external to them.

Introducing and using evidence in the policy development process

The case study results confirm that the pathways of evidence into policy making are influenced by both the production and the consumption functions of research evidence (Peterson, 2018). In general, the use of HPSR in policy development appears to be more likely where a trust-based relationship exists between policy makers and researchers. At the same time, health policy, which is itself a political issue, is often the product of national imperatives or changes in political leadership, as in Cambodia or Mexico.

In Mexico, the appointment of Guillermo Soberón and subsequently further academics as Minister of Health, established a clear role for the consumption of HPSR in policy making. This was reinforced through legislative pathways and investment in HPSR research capacity, based in decentralized institutions. Even so, political decision making resulting from changes in government has at times taken precedence over the evidence-to-policy transition.

In Cambodia, the process evolved informally. The early activities of donor partners and international NGOs experimenting with various health-system interventions during reconstruction initiated a process of piloting, research and evaluation. Much of this activity was carried out with MoH approval and participation and was supported by the then nascent NIPH. More widely, both international agencies and government leaders demanded evidence of effectiveness before adopting pilot programmes into national strategy. This organic process both fostered and relied on close and respectful working relationships between researchers and policy makers at the local and the international level.

In Ghana, the MoH’s annual summit of health officials, donors and researchers is an important conduit for interpreting and moving evidence into policy. A steady stream of MPH graduates from the University of Ghana have become increasingly influential in evidence-to-policy processes. In Cambodia, the MoH’s periodic national health strategic plan is the most common vehicle through which proven initiatives enter national policy, and intermittent national health policy forums act to assemble and reflect on evidence to support policy development (ERC1). Both Ghana and Cambodia have technical working groups for health led by the MoH and comprising government and development partners to interpret evidence and consider policy. Both countries have MoH policy and planning departments that draw, wherever possible, on research-based evidence. These examples have in common a relationship-based progression through the introduction, interpretation and application of evidence.

The Dobrow et al. (2004) approach focuses attention on the influence of external (health, economic, political) and internal (purpose, process, participants) factors that influence the introduction, interpretation and application of evidence.

External factors and politics

Health is a national issue, and health systems function within a given economic, structural and political context (Dobrow et al., 2004). Commercial interests, the political climate, prevailing legislation and many other external factors have influenced the development and implementation of the health system policies explored in these case studies. In Ghana and Cambodia, HPSR has evolved alongside the earlier stages of health-system structural development. In Mexico, HPSR had initially to find a role within a more established national structure, where economic and political interest groups were well entrenched.

It is evident that, within a context of changing external conditions, maintaining an independent HPSR structure to produce evidence in a timely fashion opens the path to necessary policy reform when political conditions allow. In Mexico, where the integrity and weight of evidence used in policy development have been shaped by intermittent power shifts between social-reform and conservative political parties, the decision-making pathway nonetheless remained open to ongoing research inputs. The design and introduction of the Seguro Popular—which was based on extra-jurisdictional evidence of universal coverage processes globally and extensive national research—was cited to be determined politically by the neo-liberal approach of the newly elected centre-right National Action Party. On the other hand, as the circumstances surrounding the introduction of the sugar-sweetened-beverage tax demonstrate, the use of evidence can provide the leverage needed to achieve a public good while steering away from undue commercial interests. In Cambodia and Ghana, research-based evidence of the impact of certain interventions (such as revisions made to the contracting model in Cambodia) has at times been weighed and assessed against broader national considerations that the government (or MoH) deems necessary to meet its own objectives.

Internal factors and the HPSR community

The purpose of HPSR, the process of research and the actors who participate in the evidence-to-policy continuum comprise the internal factors that influence policy outcomes. Within complex adaptive systems, like healthcare, policy outcomes are the product of the contest between the independent activities of each stakeholder, from researcher to policymaker, to healthcare provider or representative of an interest group. As Sheikh et al. (2014) say, understanding policy making from the perspectives of the people working within the system is a HPSR task. Our case studies demonstrate the crucial role of HPSR in policy formulation and evaluation, especially in creating locally generated evidence, even where policy choices are contested. Building an evidence-informed policy culture and embedding it within the health system is recognized as the means to maintain HPSR under changing objective conditions (Koon et al., 2013; Barasa et al., 2017).

The process is often strengthened, as in Ghana, where the evidence-informed policy culture includes regional as well as national agencies. In the more long-standing Mexican HPSR environment, the value of institutionalizing HPSR through legislation (and building permanent HPSR institutions) provided the foundation and the resources for health system researchers to continue producing objective evidence despite swings in the political leadership. In Cambodia and Ghana, the challenge has often been to manage the influence of international development partners.

Whatever the circumstances, the use of HPSR to initiate, monitor and evaluate the implementation of policies in a cumulative way provides timely data for appropriate reforms when the opportunity arises. With economic growth and rising fiscal strength, Cambodia has been able to direct increasing health resources into proven programmes to expand service coverage and financial protection, especially for poorer communities. In Ghana, domestically generated evidence has been used to influence debates around reform of the NHIS. In Mexico, where the politics of health policy formation can dominate the narrative, an embedded HPSR community continues to monitor and track health system performance and policy development.

Conclusion

Mexico, Cambodia and Ghana have each been early adopters of HPSR, with differing starting points. Their contrasting pathways demonstrate the pre-requisites for the growth and influence of HPSR within the national context. Each country must determine its own path while making best use of international experience and lessons learned. The experiences of these three diverse countries illustrate how HPSR is of most value when it is embedded as a routine part of the health system, and not a parallel or ad hoc activity, as the emergence of social-protection mechanisms in Cambodia, or evaluation of national insurance structures in Ghana, demonstrate. Mexico—as an example of a more mature, long-standing HPSR structure—may be seen as demonstrating the natural tension between a predominantly technical approach to HPSR and health reform and an approach that is influenced by wider political and values-based commitments.

Both historical and contemporary contexts influence health-system development and the HPSR agenda. These factors also influence the formation and sustainability of policy networks, including the agency and symbolic capital of their main players, the generation of evidence and its influences on policy. The resilience of evidence-informed policy making in the face of changing economic and political circumstances is made stronger with the development of independent HPSR structures embedded within the wider health system and with the capacity to shepherd the consistent use of evidence through the policy process, as the case of Mexico demonstrates most clearly.

Recommendations for countries developing evidence-informed health-systems policy processes include the following.

Build HPSR capacity and practice as an integral part of the health system, not parallel to it; support the HPSR function with social development legislation; HPSR requires a variety and number of individual researchers and institutions (both national and international); building long-term relationships between the main players is essential.

Implement HPSR with a commitment to reflecting and accounting for the national context within which health policy is determined; an understanding of the sources, introduction, interpretation and application of evidence is the foundation for the wider analysis of policy directions.

Maintain the independence of HPSR institutions to guarantee the objectivity of evidence created; ensure sustainable career paths for HPSR researchers equal to other career options; recognize and manage the influence of external and internal forces on the research process.

The role of HPSR in shaping health systems, health, and, ultimately, development outcomes—which is one part of the Sustainable Development Goals—is analogous to the concept of ‘emergence’ as coined by complexity theorists (Barasa et al., 2017; Kitson et al., 2018). Emergence describes the interaction of constituent parts of a system producing organized or patterned outcomes that are not conscious or planned by the constituent parts. While investment in HPSR is a conscious and planned activity, researchers and research institutes operate as only one part of the larger whole characterized by multiple stakeholders, all with particular interests. As our case studies demonstrate, the role of HPSR in the policy process is most effective, and most efficient, where the research component is embedded within the wider health system.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Daniel Llywelyn Strachan, The Nossal Institute for Global Health, The University of Melbourne, 333 Exhibition Street, Melbourne, VIC 3004, Australia.

Kirsty Teague, The Nossal Institute for Global Health, The University of Melbourne, 333 Exhibition Street, Melbourne, VIC 3004, Australia.

Anteneh Asefa, The Nossal Institute for Global Health, The University of Melbourne, 333 Exhibition Street, Melbourne, VIC 3004, Australia; Institute of Tropical Medicine, Kronenburgstraat 43, Antwerp (ITM) 2000, Belgium.

Peter Leslie Annear, The Nossal Institute for Global Health, The University of Melbourne, 333 Exhibition Street, Melbourne, VIC 3004, Australia.

Abdul Ghaffar, The Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO, 20 Avenue Appia, Geneva 1211, Switzerland.

Zubin Cyrus Shroff, The Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO, 20 Avenue Appia, Geneva 1211, Switzerland.

Barbara McPake, The Nossal Institute for Global Health, The University of Melbourne, 333 Exhibition Street, Melbourne, VIC 3004, Australia.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at Health Policy and Planning Journal online.

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the need to maintain the privacy of individuals that participated in the study in accordance with the conditions for ethical approval. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

This work was supported by the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization. The Alliance is supported through both core funding as well as project-specific designated funds. The full list of Alliance donors is available at: https://ahpsr.who.int/about-us/funders.

Author contributions

B.McP., A.G. and Z.C.S. conceived and B.McP., D.L.S. and P.A. designed the study. D.L.S., K.T., A.A.B. and P.L.A. collected and analysed the data and, with B.McP., interpreted it. D.L.S., K.T. and P.L.A. drafted the article and critically revised it with contributions from A.A.B. and B.McP. and critical feedback from A.G. and Z.C.S. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Reflexivity statement

The authors include two females and five males and span multiple levels of seniority. All authors have engaged for several years in research activities with a health policy and systems focus with three authors having done so for more than 30 years. Collectively, the authors have applied research experience in Mexico, Cambodia and Ghana. The authors’ academic training is diverse with two being health economists, two with first degrees in medicine, one a social psychologist, one originally trained in occupational therapy and one in nursing. All authors have several years’ experience conducting qualitative research and literature reviews.

Authorship

The team of authors conducted the study of experiences in three disparate countries as an objective, outside view supported by anonymous contribution from in-country experts. While the focus of the article is the experience of health policy and systems research in Mexico, Cambodia and Ghana, and expert respondents with significant experience at national level were recruited as key informants to the study, these individuals are not named as authors. This decision was taken for two reasons. First, to enable separation of expert national respondent testimony from the analysis and interpretation of it. Second, in accordance with the ethical approval granted for the study based on the preservation of anonymity of expert national respondents.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was received from the Human Ethics Sub-Committee at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, Human Ethics Advisory Group at the University of Melbourne, Australia (Ethics ID: 2057979.1).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- Adua E, Frimpong K, Li X, wang W. 2017. Emerging issues in public health: a perspective on Ghana’s healthcare expenditure, policies and outcomes. EPMA Journal 8: 197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbanyo R. 2020. Ghana’s national health insurance, free maternal healthcare and facility-based delivery services. African Development Review 32: 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Agyepong IA, Adjei S. 2008. Public social policy development and implementation: a case study of the Ghana National Health Insurance scheme. Health Policy & Planning 23: 150–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agyepong IA, Anniah K, Aikins M. et al. 2015. Health policy, health systems research and analysis capacity assessment of the School of Public Health, University of Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal 49: 200–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikins ADEG. 2016. Health policy and systems research in Ghana: a preliminary review of the evidence. In: Aryeety, E. B-D, Sackey B, Arfranie S (eds). Contemporary Social Policy Issues in Ghana. Chap. 9. Accra, Ghana: Sub Saharan Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Aikins ADEG, Koram K. 2017. Health and Healthcare in Ghana, 1957–2017. In: Aryeetey E, Kanbur R (eds). The Economy of Ghana Sixty Years after Independence. Chap. 22. UK: Oxford University Press, 365–84. [Google Scholar]

- Alhassan RK, Nketiah-amponsah E, Arhinful DK, Coles JA. 2016a. A review of the national health insurance scheme in ghana: what are the sustainability threats and prospects? PLoS One 11: e0165151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhassan RK, Nketiah-Amponsah E, Spieker N, Arhinful DK, Rinke de Wit TF. 2016b. Perspectives of frontline health workers on Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme before and after community engagement interventions. BMC Health Services Research 16: 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annear P. 1998. Health and development in Cambodia. Asian Studies Review 22: 193–221. [Google Scholar]

- Annear P. 2010. Health Equity Funds in Cambodia: a comprehensive review of the literature and annotated bibliography. Health Policy and Health Financing Knowledge Hub Working Paper. Number 9, November 2010. Melbourne: Nossal Institute for Global Health. [Google Scholar]

- Annear PL, Grundy J, Ir P. et al. 2015. The Kingdom of Cambodia health system review. In: Annear PL (ed). Health Systems in Transition, Vol. 5. Manila: World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific. [Google Scholar]

- Annear PL, Lee JT, Khim KV. et al. 2019. Protecting the poor? Impact of the national health equity fund on utilization of government health services in Cambodia, 2006-2013. BMJ Global Health 4: e001679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argen D. 2020. Farewell seguro popular. The Lancet 395: 549–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryeetey GC, Nonvignon J, Amissah C, Buckle G, Aikins M. 2016. The effect of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) on health service delivery in mission facilities in Ghana: a retrospective study. Globalization and Health 12: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asenso-Okyere WK. 1995. Financing health care in Ghana. World health forum 16: 86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asenso-Okyere WK, Anum A, Osei-Akoto I, Adukonu A. 1998. Cost recovery in Ghana: are there any changes in health care seeking behaviour?. Health Policy and Planning 13: 181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awoonor‐Williams JK, Phillips JF, Bawah AA. 2016. Catalyzing the scale‐up of community‐based primary healthcare in a rural impoverished region of northern Ghana. International Journal of Health Planning and Management 31: e273–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barasa EW, Cloete K, Gilson LJ. 2017. From bouncing back, to nurturing emergence: reframing the concept of resilience in health systems strengthening. Health Policy & Planning 32: iii91–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barquera S, Campos I, Rivera JA. 2013. Mexico attempts to tackle obesity: the process, results, push backs and future challenges. Obesity Reviews 14: 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barquera S, Rivera JA. 2020. Obesity in Mexico: rapid epidemiological transition and food industry interference in health policies. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 8: 746–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawah AA, Awoonor-Williams JK, Asuming PO. et al. 2019. The child survival impact of the Ghana Essential Health Interventions Program: a health systems strengthening initiative in a rural region of Northern Ghana. PLoS One 14: e0218025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, Agyepong IA, Sheikh K. et al. 2011. Building the field of health policy and systems research: an agenda for action. PLoS Medicine 8: e1001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binka FN, Bawah AA, Phillips JF. et al. 2007. Rapid achievement of the child survival millennium development goal: evidence from the Navrongo experiment in Northern Ghana. Tropical Medicine & International Health 12: 578–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birn A-E. 2006. Marriage of Convenience: Rockefeller Internationl Health and Revolutionary Mexico. Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press (Boydell & Brewer). [Google Scholar]

- Bloom E, Bhushan I, Clingingsmith D. et al. 2006. Contracting for Health: Evidence from Cambodia. Asian Development Bank, World Bank. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/20060720cambodia.pdf, accessed 12 July 2022.

- Bobadilla JL, Infante C, Langer A, Lozano R, Frenk Mora J. 1989. Advances in public health investigation. 5 years’ work of the Center for Research in Public Health, 1984-1989. Salud Publica Mexico 31: 550–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriedo A, Lock K, Hawkins B. 2020. Policy process and Non-State Actors’ Influence on the 2014 Mexican Soda Tax. Health Policy & Planning 35: 941–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhun C, Kimsun T, Yu G, Ensor T, Mcpake B. 2015. Impact of health financing policies on household spending: evidence from Cambodia Socio-Economic Surveys 2004 and 2009. ReBUILD Consortium. CDRI Working Paper Series No.106. Cambodia Development Resource Institute, Phnom Penh. [Google Scholar]

- Dalinjong PA, Wang AY, Homer CSE. 2017. The operations of the free maternal care policy and out of pocket payments during childbirth in rural Northern Ghana. Health Economics Review 7: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrow MJ, Goel V, Upshur RE. 2004. Evidence-based health policy: context and utilisation. Social Science & Medicine 58: 207–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovlo D. 1998. Health sector reform and deployment, training and motivation of human resources towards equity in health care: issues and concerns in Ghana. Division of Human Resources. Acra: Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- ESPM . 2009. Centro de Investigación en Salud Poblacional. Primera edición/septiembre 2009© Instituto Nacional de Salud PúblicaAv. Universidad 655, colonia Santa María Ahuacatitlán 62100 Cuernavaca, Morelos, México. https://www.insp.mx/centros/salud-poblacional.html, accessed 12 July 2022.

- Frenk J. 2006. Bridging the divide: global lessons from evidence-based health policy in Mexico. The Lancet 368: 954–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk J, Bobadilla JL, Sepúlveda J. et al. 1986. An innovative approach to public health research: the case of a new center in Mexico. Journal of Health Administration Education 4: 467–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster M, Burrowes S, Cuadrado C. et al. 2020. Understanding policy change for obesity prevention: learning from sugar-sweetened beverages taxes in Mexico and Chile. Health Promotion International 36: 155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A, Olivier J, Glandon D, Kapilashrami A, Gilson L. 2019. Health systems for all in the SDG era: key reflections based on the Liverpool statement for the fifth global symposium on health systems research. Health Policy & Planning 34: ii135–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffar A, Tran N, Langlois E, Shroff Z, Javadi D. 2017. Alliance for health policy and systems research: aims, achievements and ambitions. Public Health Research & Practice 27: 2711703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHS . 2017. Policy, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation Division. Accra: Ghana Health Service. https://www.ghanahealthservice.org/ghs-division.php?ghs&ghsdid=9, accessed 15 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez EJ. 2019. Coca-Cola’s political and policy influence in Mexico: understanding the role of institutions, interests and divided society. Health Policy & Planning 34: 520–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Block MÁ. 2009. Leadership, institution building and pay-back of health systems research in Mexico. Health Research Policy & Systems 7: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Block MÁ, Arroyo Laguna J, Cetrángolo O. et al. 2020b. Health policy and systems research publications in Latin America warrant the launching of a new specialised regional journal. Health Research Policy & Systems 18: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Block MÁ, Reyes Morales H, Cahuana Hurtado L. et al. 2020a. Mexico: Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition, Vol. 22 No. 2. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/334334, accessed 12 July 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyet S, Touch S, Ir P. et al. 2015. Gaps between research and public health priorities in low income countries: evidence from a systematic literature review focused on Cambodia. Implementation Science 10: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homedes N, Ugalde A. 2009. Twenty-five years of convoluted health reforms in Mexico. PLoS Medicine 6: e1000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ir P, Bigdeli M, Meessen B, Van Damme W. 2010. Translating knowledge into policy and action to promote health equity: a case study of health equity funds to improve access to health services for the poor in Cambodia. Health Policy 96: 200–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James E, Lajous M, Reich MR. 2020. The politics of taxes for health: an analysis of the passage of the sugar-sweetened beverage tax in Mexico. Health Systems & Reform 6: e1669122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanmiki EW, Akazili J, Bawah AA. et al. 2019. Cost of implementing a community-based primary health care strengthening program: the case of the ghana essential health interventions program in northern Ghana. PLoS One 14: e0211956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khim KV, Ir P, Annear PL. 2017. Factors driving changes in the design, implementation and scaling-up of the contracting of health services in rural Cambodia, 1997–2015. Health Systems & Reform 3: 105–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitson A, Brook A, Harvey G. et al. 2018. Using complexity and network concepts to inform healthcare knowledge translation. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 7: 231–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koon AD, Rao KD, Tran NT, Ghaffar A. 2013. Embedding health policy and systems research into decision-making processes in low- and middle-income countries. Health Research Policy and Systems 11: 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kweku M, Amu H, Awolu A. et al. 2020. Community-based health planning and services plus programme in Ghana: a qualitative study with stakeholders in two Systems Learning Districts on improving the implementation of primary health care. PLoS One 15: e0226808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde M, Palmer N. 2009. The impact of contracting out on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews CD008133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakin J. 2010. The end of insurance? Mexico’s Seguro Popular, 2001-2007. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 35: 313–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANCET . 2006. Mexico: Health System Reform [Series form the Lancet journals]. www.thelancet.com/series/health-system-reform-in-mexico, accessed 12 July 2022.

- Laurell AC. 2007. Health system reform in Mexico: a critical review. International Journal of Health Services 37: 515–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurell AC. 2015a. The Mexican popular health insurance: myths and realities. International Journal of Health Services 45: 105–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurell AC. 2015b. Three decades of neoliberalism in Mexico: the destruction of society. International Journal of Health Services 45: 246–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liverani M, Chheng K, Parkhurst J. 2018. The making of evidence-informed health policy in Cambodia: knowledge, institutions and processes. BMJ Global Health 3: e000652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mam BH, Key PJ. 1995. Cambodian health in transition. British Medical Journal (International Edition) 311: 435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Martínez E, Zaragoza ML, Solano E. et al. 2012. Health research funding in Mexico: the need for a long-term agenda. PLoS One 7: e51195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micah AE, Chen CS, Zlavog BS. et al. 2019. Trends and drivers of government health spending in sub-Saharan Africa, 1995-2015. BMJ Global Health 4: e001159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . 2008. Health Strategic Plan 2008-2015: Accountability, Efficiency, Quality, Equity. Phnom Penh, Cambodia. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/36645842/health-strategic-plan-2008-2015-ministry-of-health, accessed 12 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . 2020. National Health Policy: ensuring healthy lives for all. Accra, Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . 2021. Strengthening the Resilience of Ghana’s Health System to Better Respond to Emergencies. Acra, Ghana. https://2021.healthsummitgh.org, accessed 12 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Insurance Authority . 2013. 2013 annual report. Accra, Ghana: National Health Insurance Authority. [Google Scholar]

- NIPH . 2015. Mapping and Planning Health Systems Research in Cambodia: Building the Evidence base for Policy and Practice. Report of the Cambodia Health Researchers’ Forum. https://www.gov.uk/research-for-development-outputs/mapping-and-planning-health-systems-research-in-cambodia-building-the-evidence-base-for-policy-and-practice-report-of-the-cambodia-health-researchers-forum, accessed 12 July 2022.

- NIPH . 2018. First consultative workshop on developing a National Agenda for health systems research. 17August. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: (available from the authors). [Google Scholar]

- Norris SL, Rehfuess EA, Smith H. et al. 2019. Complex health interventions in complex systems: improving the process and methods for evidence-informed health decisions. BMJ Global Health 4: e000963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyonator F, Kutzin J. 1999. Health for some? The effects of user fees in the Volta Region of Ghana. Health Policy and Planning 14: 329–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda E, Torres C, Carriedo Á. et al. 2020. The influence of the sugar-sweetened beverage industry on public policies in Mexico. International Journal of Public Health 65: 1037–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoroh J, Essoun S, Seddoh A. et al. 2018. Evaluating the impact of the national health insurance scheme of Ghana on out of pocket expenditures: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research 18: 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxman AD, Bjørndal A, Becerra-Posada F. et al. 2010. A framework for mandatory impact evaluation to ensure well informed public policy decisions. The Lancet 375: 427–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SW, Saenz J, Wong R. 2018. Health insurance and the aging: evidence from the seguro popular program in Mexico. Demography 55: 361–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry H, Crigler L, Hodgins SL (eds.) 2014. Developing and Strengthening Community Health Worker Programs at Scale: A Reference Guide for Program Managers and Policy Makers. USAID. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pa00jxwd.pdf, accessed 12 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peters DH. 2018. Health policy and systems research: the future of the field. Health Research Policy and Systems 16: 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson MA. 2018. In the shadow of politics: the pathways of research evidence to health policy-making. Journal of Health Politics, Policy & Law 43: 341–76. [Google Scholar]

- RDI Network . 2017. From Evidence to Impact: Development contribution of Australian Aid funded research–A study based on research undertaken through the Australian Development Research Awards Scheme 2007–2016. Authored by Debbie Muirhead with Juliet Willetts, Joanne Crawford, Jane Hutchison and Philippa Smales. https://rdinetwork.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/From-Evidence-to-Impact-Full-Report.pdf, accessed 12 July 2022.

- Reich MR. 2020. Restructuring health reform, mexican style. Health Systems & Reform 6: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleiff MJ, Kuan A, Ghaffar A. 2020. Comparative analysis of country-level enablers, barriers and recommendations to strengthen institutional capacity for evidence uptake in decision-making. Journal of Health Research Policy and Systems 18: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz RW, Tietje O. 2002. Embedded Case Study Methods: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Knowledge. USA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Seddoh A, Akor SA. 2012. Policy initiation and political levers in health policy: lessons from Ghana’s health insurance. BMC Public Health 12: S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh K, George A, Gilson L. 2014. People-centred science: strengthening the practice of health policy and systems research. Journal of Health Research Policy and Systems 12: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shroff ZC, Javadi D, Gilson L, Kang R, Ghaffar A. 2017. Institutional capacity to generate and use evidence in LMICs: current state and opportunities for HPSR. Journal of Health Research Policy and Systems 15: 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull B, Gordon SF, Martínez-Andrade GO, González-Unzaga M. 2019. Childhood obesity in Mexico: a critical analysis of the environmental factors, behaviours and discourses contributing to the epidemic. Health Psychology Open 6: 2055102919849406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquieta-Salomón JE, Villarreal HJ. 2016. Evolution of health coverage in Mexico: evidence of progress and challenges in the Mexican health system. Health Policy & Planning 31: 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle AM. 2016. The Mexican experience in monitoring and evaluation of public policies addressing social determinants of health. Global Health Action 9: 29030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyoro KP, Hawkins K, Greenall M. et al. 2019. Local ownership of health policy and systems research in low-income and middle-income countries: a missing element in the uptake debate. BMJ Global Health 4: e001523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls H, Liverani M, Chheng K, Parkhurst J. 2017. The many meanings of evidence: a comparative analysis of the forms and roles of evidence within three health policy processes in Cambodia. Journal of Health Research Policy and Systems 15: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson D. 2012. Review of the functioning of the Technical Working Group for Health. Report prepared for the TWGH Secretariat. Phnom Penh. (Available from the authors.)

- Witter S, Anderson I, Annear P. et al. 2019. What, why and how do health systems learn from one another? Insights from eight low-and-middle-income country case studies. BMC Health Research Policy and Systems 17: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 1994. Cambodia: From Rehabilitation to Reconstruction. East Asia and Pacific Region, Country Department 1, Phnom Penh. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/408971468743782412/cambodia-from-rehabilitation-to-reconstruction-an-economic-report, accessed 12 July 2022.

- World Health Organization . 2019. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000 to 2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/327596, accessed 12 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the need to maintain the privacy of individuals that participated in the study in accordance with the conditions for ethical approval. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.