Abstract

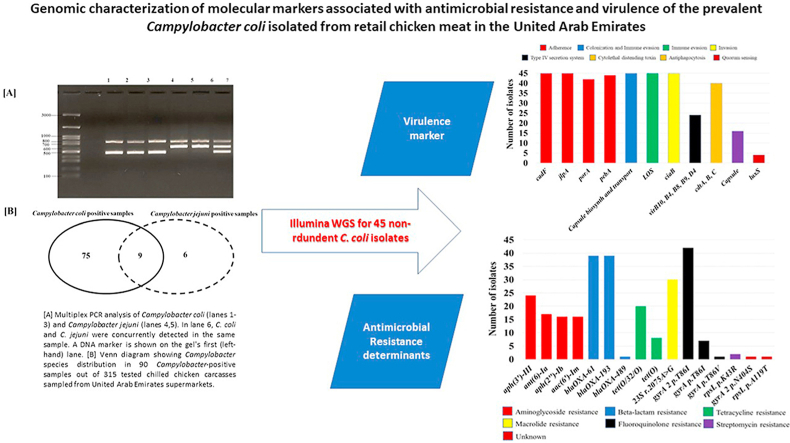

Campylobacter is a major cause of gastroenteritis worldwide, with broiler meat accounting for most illnesses. Antimicrobial intervention is recommended in severe cases of campylobacteriosis. The emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Campylobacter is a concerning food safety challenge, and monitoring the trends of AMR is vital for a better risk assessment. This study aimed to characterize the phenotypic profiles and molecular markers of AMR and virulence in the prevalent Campylobacter species contaminating chilled chicken carcasses sampled from supermarkets in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Campylobacter was detected in 90 (28.6%) out of 315 tested samples, and up to five isolates from each were confirmed using multiplex PCR. The species C. coli was detected in 83% (75/90) of the positive samples. Whole-genome sequencing was used to characterize the determinants of AMR and potential virulence genes in 45 non-redundant C. coli isolates. We identified nine resistance genes, including four associated with resistance to aminoglycoside (aph(3′)-III, ant(6)-Ia, aph(2″)-Ib, and aac(6′)-Im), and three associated with Beta-lactam resistance (blaOXA-61, blaOXA-193, and blaOXA-489), and two linked to tetracycline resistance (tet(O/32/O), and tet(O)), as well as point mutations in gyrA (fluoroquinolones resistance), 23S rRNA (macrolides resistance), and rpsL (streptomycin resistance) genes. A mutation in gyrA 2 p.T86I, conferring resistance to fluoroquinolones, was detected in 93% (42/45) of the isolates and showed a perfect match with the phenotype results. The simultaneous presence of blaOXA-61 and blaOXA-193 genes was identified in 86.6% (39/45) of the isolates. In silico analysis identified 7 to 11 virulence factors per each C. coli isolate. Some of these factors were prevalent in all examined strains and were associated with adherence (cadF, and jlpA), colonization and immune evasion (capsule biosynthesis and transport, lipooligosaccharide), and invasion (ciaB). This study provides the first published evidence from the UAE characterizing Campylobacter virulence, antimicrobial resistance genotype, and phenotype analysis from retail chicken. The prevalent C. coli in the UAE retail chicken carries multiple virulence genes and antimicrobial resistance markers and exhibits frequent phenotype resistance to macrolides, quinolones, and tetracyclines. The present investigation adds to the current knowledge on molecular epidemiology and AMR development in non-jejuni Campylobacter species in the Middle East and globally.

Keywords: Campylobacter spp, Poultry, Antibiotic resistance, Whole-genome sequencing, UAE

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Out of 315 broiler carcasses from retail in the U.A.E., Campylobacter coli was the dominant species in 83% of the +ve samples.

-

•

W.G.S. was utilized to determine antimicrobial resistance markers and virulence genes in 45 C. coli isolates.

-

•

Seven to 11 virulence factors per each C. coli isolate.

-

•

High frequency of quinolones (42/45) and macrolides (30/45) resistance among C. coli from the U.A.E. retail market.

1. Introduction

Campylobacter is among the key foodborne bacterial pathogens causing gastroenteritis worldwide, with about one hundred million cases of foodborne illness per year (Majowicz et al., 2020). The species Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli are commonly associated with human illnesses, with an estimated infectious dose of just a few hundred bacterial cells (Asuming-Bediako et al., 2019). Campylobacter colonizes the gut of broiler chicken and can be transferred to the carcass during slaughter processing and spread further to retail chicken meat. Cross-contamination arising from poor hygienic handling of raw chicken is considered the leading risk factor impacting human exposure to Campylobacter (Henry et al., 2011; Asuming-Bediako et al., 2019).

Campylobacter harbors a sophisticated set of virulence and fitness determinants that facilitate host invasion and avoidance (adhesion, survival inside the epithelial cells of the human intestine, and invasion) (Bolton, 2015). Other factors include flagella, glycosylation of flagellins, capsular polysaccharide, lipooligosaccharide, and genotypic diversity owing to several phase-variable loci (Nauta et al., 2009). In severe cases of campylobacteriosis, ciprofloxacin (fluoroquinolone) and erythromycin (macrolide) are recommended as the first choice-antimicrobial treatment (Asuming-Bediako et al., 2019). However, there is a growing trend in many regions worldwide in Campylobacter resistance to antimicrobials, notably against fluoroquinolones in C. jejuni and erythromycin in C. coli (Asakura et al., 2019; Asuming-Bediako et al., 2022). The acquisition of various determinants mediates antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter, and genetic mechanisms is related to a mixture of inherent and acquired mechanisms, such as resistance genes, point mutations, and efflux pumps (Asakura et al., 2019).

In the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, 2–28% of human diarrheal cases are attributed to infection with Campylobacter (Kaakoush et al., 2015). Nevertheless, there is currently minimal surveillance data for Campylobacter at the human-food interface across the GCC nations. Worldwide, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a significant consumer of local and imported chicken meat, with ∼60 kg/capita a year (USDA, 2021). The broiler industry has been expanding in recent years in the UAE and is foreseen as a growing sector to aid with the food security gap in the country (USDA, 2021). However, currently, there is limited research in the UAE on the status of microbial contamination in chicken meat (Habib et al., 2021). No baseline studies in the UAE have investigated the extent of antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter in the broiler meat chain (Habib et al., 2021). Such baseline data are critical for establishing a national program to control the foodborne transmission of Campylobacter and are fundamental for surveillance AMR from a One Health perspective.

Because of the public health and food safety importance of Campylobacter, we aimed in this study to: (i) determine the prevalence of Campylobacter spp. (referring to the thermo-tolerant species C. jejuni and C. coli) in retail chilled whole chicken carcasses in the UAE; (ii) analyze the phenotypic resistance to clinically important antibiotics, and to characterize using whole-genome sequencing the determinants conferring AMR and virulence markers in a selection of the prevalent Campylobacter species presented in the UAE retail chicken meat.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sampling and survey

Between March to December 2021, a total of 315 whole chicken carcasses were purchased from the chilled display of various (n = 26) supermarkets in the UAE. The samples were obtained on two monthly occasions (15 per each). We targeted (after deliberation with national food control bodies) samples from seven different brands (denoted anonymously as A to G). These brands included major national processors (all from broiler flocks raised in the UAE), supplying more than 75% of the chilled chicken to the UAE retail. None of the seven processors produce organic chicken (all are from conventional production systems). All samples were collected from chilled supermarkets display, where all the carcasses were packed and labeled by brand. Samples were shipped for testing on the same day in chilled containers, and all microbiological testing was achieved within 6 h of collection.

2.2. Campylobacter isolation and species confirmation

Standard Campylobacter enumeration was carried out using a modification of the ISO 10272:2006 method (Habib et al., 2011). This study adopted the enumeration method to generate quantitative data to support future risk assessment for Campylobacter contamination in chicken meat in the UAE. For the tested whole carcasses, the sample was excised from the neck skin. Neck skin is one of the most positive carcass sites for detecting Campylobacter (Baré et al., 2013). A 10 g of neck skin was mixed with 90 ml (nine volumes) of 0.1% peptone water (Oxoid, Basingstoke, England) and homogenized for 1 min in a bag-mixer blender. From this sample homogenate (10− 1), a volume of 1 ml was spread plated (0.3, 0.3, 0.3, and 0.1 ml) over four modified charcoal cefoperazone deoxycholate agar plates (mCCDA) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, England). The enumeration procedures of Campylobacter using 1 ml of the initial homogenate over 3 or 4 plates has been utilized by several studies in order to improve the chance of Campylobacter enumeration, notably when the samples carry low loads (Habib et al., 2019). A further (10− 2) serial dilution was done in peptone water, of which 0.1 ml was spread over the surface of mCCDA. Plates were incubated micro-aerobically by introducing sachets of CampyGen (Oxoid) in a rectangular jar (2.5 L capacity). All plates were incubated at 41.5 °C and counted after 48 h.

Up to five presumptive colonies per sample were selected according to their colony morphology and stored at −80 °C for further confirmation. DNA extraction was achieved from an 18–24 h culture of the suspected colonies using a commercial kit (Wizard®, Promega, USA). A multiplex PCR assay amplifying 16S rRNA, mapA, and ceuE genes was used to confirm the genus as Campylobacter and distinguish between the thermo-tolerant species C. jejuni and C. coli. The PCR conditions and oligonucleotides were described previously by Denis et al. (1999).

2.3. Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis

A subset of 45 non-redundant C. coli isolates (one isolate per positive sample from unrelated batches) was characterized further at the genome level. WGS was carried out using short reads technology (Illumina, NovaSeq) through a commercial service (Novogene, the United Kingdom). De Novo assembly was carried out using SPADES (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SPAdes/) and assembled into contigs. The assembled contigs were uploaded to PathogenWatch (https://pathogen.watch) (accessed May 20, 2022) to confirm species identification. The genomes that passed the quality tests were used to predict resistance genes via NCBI Antimicrobial Resistance Gene Finder (AMRFinder; https://github.com/ncbi/amr), and virulence genes were detected via ABRicate (https://github.com/tseemann/abricate), and by using the REsfinder (https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/) and Virulence finder (https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/VirulenceFinder/) databases. Point mutations in specific genes conferring antimicrobial resistance were examined using SSI wrapper for calling and parsing the output of KMA (Kmer Aligner) for finding point mutations (https://github.com/ssi-dk/punktreskma). Hits were considered only for gene identities ≥60% and lengths ≥90% (Dahl et al., 2021).

All read data generated in this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive, and the whole-genome-sequenced Campylobacter coli can be accessed under BioProject number PRJNA897955 (accession numbers are in continuous serial between SAMN31596899 and SAMN31596941). Novel sequence types (STs) were registered and assigned identification numbers through the designated multilocus sequence types (MLST) database of Campylobacter (PubMLST; https://pubmlst.org/organisms/campylobacter-jejunicoli).

2.4. Antimicrobial resistance

For isolates characterized by WGS, antimicrobial resistance was evaluated using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) (EUCAMP2 plates; Thermo Scientific, USA). The following antibiotics (and dilution ranges) were evaluated in the panel: gentamicin (GEN; 0.12–16 mg/L), ciprofloxacin (CIP; 0.12–16 mg/L), nalidixic acid (NAL; 1–64 mg/L), tetracycline (TET; 0.5–64 mg/L), streptomycin (STR; 0.25–16 mg/L), and erythromycin (ERY; 1–128 mg/L). MIC classification was interpreted as wild-type (susceptible) or non-wild-type (resistant) using the epidemiological cutoff (ECOFF) defined by European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility (EUCAST) (EFSA et al., 2022). The relatedness between AMR genotypes and phenotypes was calculated by dividing the count of resistant isolates based on their genotype by the count of isolates that showed phenotypic resistance (Dahl et al., 2021).

3. Analysis of data

Campylobacter detection frequencies across the different retail brands were compared using descriptive analysis and logistic regression procedures. Differences with P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were done using the STATA software, version 16.0 (STATA Corporation. 2020).

4. Results and discussion

The study provides the first insight into the genomic characterization of antimicrobial resistance and virulence markers in Campylobacter isolated from retail chilled chicken carcasses from supermarkets in the UAE, a country among the biggest markets for per capita chicken meat consumption (USDA, 2021).

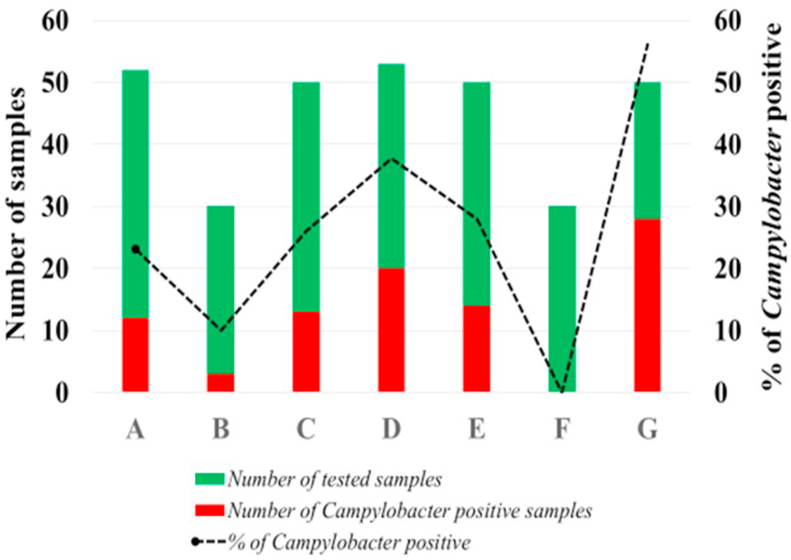

4.1. Overall campylobacter detection in chilled chicken carcasses

Campylobacter isolates were recovered from 90 of 315 chilled whole chicken carcasses. Results in Fig. 1 shows evident variation across the seven brands regarding the recovery of Campylobacter among their samples. Of note, all (n = 30) carcasses from Company F were Campylobacter-negative, while samples from company G (n = 30) showed a significantly higher rate (logistic-regression odds ratio [OR] = 11.4, p-value< 0.0001) of Campylobacter detection.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of Campylobacter in retail chilled carcasses representing seven brands (denoted A to G) for sale in the United Arab Emirates supermarkets.

Lower recovery (28.6%) of Campylobacter in chicken carcasses was observed in our study compared to other Gulf Cooperation Council countries in the region, such as Qatar (36.5%) and Saudi Arabia (52.2%) (Mohammed et al., 2015; Alarjani et al., 2021). The recovery of Campylobacter from supermarket broiler carcasses based on the direct plating methods has been hypothesized to be lower as the bacterial load fall below the limit of detection of the plate count method (below one log10 CFU/g) of such a method (Oyarzabal et al., 2007). To avoid potential underestimation in the prevalence estimate, a selective enrichment method for Campylobacter and direct plating for quantification should be considered fully determine baseline studies of Campylobacter in the UAE.

Except for samples from one producer [F], our results indicate that all other retail brands were positive for Campylobacter (Fig. 1). These results reflect variation in prevalence, may be due to variations in flock prevalence and processing approaches to control carcass contamination. Several authors have reported that the load of bacteria contaminating the surface of broiler carcasses might be affected by practices occurring across the processing line, as well as by chicken rearing and preharvest management (Sampers et al., 2008; Stella et al., 2017). In subsequent work, it will be essential to investigate if and how certain processing practices could influence the Campylobacter contamination risk profile across the different producers in the UAE.

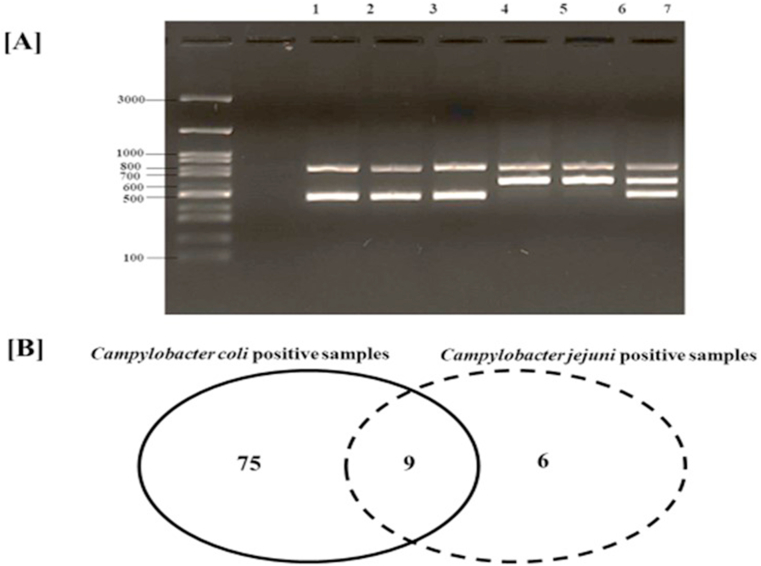

4.2. Campylobacter coli is dominant in retail chicken for sale in UAE supermarkets

Using multiplex PCR (Fig. 2. A), C. coli was confirmed as the dominant single species detected in 75 of 90 Campylobacter-positive samples (Fig. 2. B). In this study, the high representation of C. coli in broiler carcasses essentially contradicts other studies in various regions across the world, where typically C. jejuni is more common than C. coli. Nevertheless, in some survey studies, in Australia, Argentina, and China, C. coli was reported to be the prevalent species isolated from chicken meat and offal (Ma et al., 2014; Walker et al., 2019; Schreyer et al., 2022). Additionally, in reporting antimicrobial resistance in the European Union, some countries in central and south Europe have also reported C. coli as more prevalent than C. jejuni in broiler meat (EFSA et al., 2022). Previous research noted that the colonization of C. coli in the broiler gut seems to depend on the studies' geographical setting, the broiler's age at slaughter, and potential selection due to antibiotic usage (Henry et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016). The high occurrence of C. coli in the UAE retail chicken carcasses and its impact on public health warrants further investigation.

Fig. 2.

[A] Multiplex PCR analysis of Campylobacter coli (lanes 1–3) and Campylobacter jejuni (lanes 4,5). In lane 6, C. coli and C. jejuni were concurrently detected in the same sample. A 100 bp DNA marker is shown on the gel's first (left-hand) lane. [B] Venn diagram showing Campylobacter species distribution in 90 Campylobacter-positive samples out of 315 tested chilled chicken carcasses sampled from United Arab Emirates supermarkets.

4.3. Whole-genome-based characterization of a subset of C. coli

4.3.1. Clonality and population structure

All Campylobacter coli isolates were assembled to a near-complete form with an average genome size of 1,921,359 bp. The genomes were assembled at high continuity with an average N50 of 142,172 bp, the largest N50 achieved for a single isolate is around 248,261 bp. The complete list of the basic statistics of the assemblies of all isolates is given in Supplementary Table 1.

The 45 genomes identified previously described five multilocus sequence types (ST464, ST830, ST1628, ST2718, and ST12096), all belonging to one clonal complex (CC-828). As presented in Table 1, eight novel STs were identified for the first time among 21 of the sequenced C. coli isolated from retail chicken in the UAE. Five of the eight newly assigned STs belong to CC-828, and were detected across several brands (Table 1).

Table 1.

New multilocus sequence types (STs) identified in this study and their assigned clonal complexes (CC).

| Sequence Type (ST) | Clonal Complex (CC) | aspA | glnA | gltA | glyA | pgm | tkt | uncA | Number of C. coli isolates | Source/brand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12243 | CC-828 | 33 | 39 | 103 | 140 | 104 | 206 | 17 | 1 | D |

| 12244 | CC-828 | 33 | 66 | 30 | 79 | 104 | 35 | 17 | 1 | C |

| 12245 | CC-828 | 33 | 39 | 30 | 140 | 483 | 47 | 17 | 2 | B, G |

| 12246 | NAa | 33 | 38 | 30 | 79 | 189 | 206 | 17 | 1 | G |

| 12247 | CC-828 | 33 | 39 | 30 | 79 | 483 | 47 | 17 | 6 | C (4), D (1), E (1) |

| 12248 | NA | 33 | 38 | 30 | 79 | 189 | 47 | 17 | 1 | B |

| 12249 | NA | 33 | 66 | 30 | 79 | 189 | 206 | 17 | 2 | G |

| 12250 | CC-828 | 33 | 38 | 30 | 140 | 104 | 206 | 17 | 7 | G (3), C (1), D (1), E (1) |

NA, not assigned to a known clonal complex.

The predominance of the CC-828 was expected since several studies demonstrated its global spread in both human and chicken C. coli populations (Hull et al., 2021; Tedersoo et al., 2022). The prevalent clonal complex we have found in the UAE retail chicken is concordant with the worldwide dynamics of the C. coli population (Kaakoush et al., 2015). Keeping track of molecular epidemiology in the local setting adds to the universal picture of the movement of dominant Campylobacter strains and subtypes.

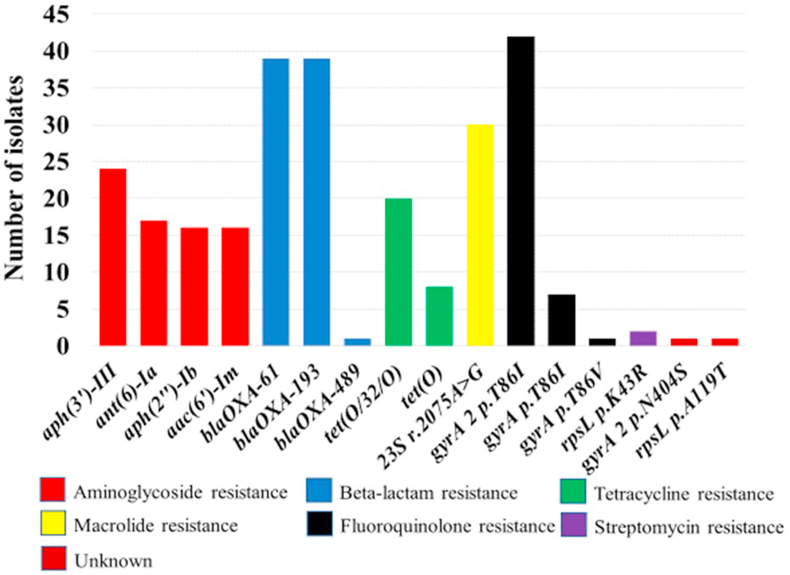

4.3.2. Genotypic determinants of antimicrobial resistance

Fig. 3 provides an overview of the detected AMR genes and resistance-associated point mutations. The most frequently encountered point mutation was the gyrA 2 p.T86I (nucleotide change, ACT –> ATT) conferring resistance to quinolones, which was detected in 42/45 (93.3%) of the sequenced C. coli isolates in this study (Fig. 3). The T86I mutation in the gyrA gene has been reported as the most prevalent AMR mechanism in Campylobacter from animal and human sources (Zhang et al., 2003). In addition to the gyrA mutation, an RNA mutation 23S r.2075 conferring macrolide-resistance (nucleotide change, A - > G) was present among 30/45 (66.6%) of the characterized C. coli (Fig. 3). This point mutation is the most prevalent genetic determinant conferring high levels of erythromycin resistance in Campylobacter (Vinueza-Burgos et al., 2017).

Fig. 3.

Frequency of genetic determinants associated with resistance genes and point mutations on genomes of 45 Campylobacter coli isolated from chilled chicken carcasses sampled from United Arab Emirates supermarkets.

Three types of β-lactam (blaOXA) genes were detected based on WGS analysis; blaOXA-61 and blaOXA-193 were concurrently present in 39/45 (86.6%). β-lactams are not typically prescribed for treating campylobacteriosis, and most of the panels used for routine AMR monitoring for Campylobacter spp. currently do not include this class of antimicrobials (Ocejo et al., 2021). Four genes associated with aminoglycoside resistance (aph(3′)-III, ant(6)-Ia, aph(2″)-Ib, and aac(6′)-Im), and two linked to tetracycline resistance (tet(O/32/O) in 20 C. coli, and tet(O)) in eight isolates were also identified (Fig. 3). This study elaborates further the added value of WGS in the hazard characterization of foodborne pathogens, such as C. coli, providing genomic insight into determinants of AMR.

4.3.3. Concordance between phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial resistance

As shown in Table 2, for the six antimicrobials included in the MIC test panel, there was an agreement ranging from 94 to 100% between MICs above the ECOFF breakpoint and the predicted resistance genes or mutations. Our results indicate a 100% concordance between genotype and phenotype for (fluoro)quinolones (nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin) and erythromycin. Previous studies reported a similar perfect correlation level for Campylobacter in different populations, including human, poultry, and ruminants sourced isolates (Dahl et al., 2021; Ocejo et al., 2021). Hence, adopting outcomes based on WGS to identify the genetic markers conferring the phenotypic resistance against clinically significant antimicrobials should be considered much more broadly in national and regional antimicrobial monitoring programs for Campylobacter.

Table 2.

Concordance between resistance genotype and phenotype for 45 Campylobacter coli isolated from chilled chicken carcasses sampled from United Arab Emirates supermarkets.

| Classes of antimicrobials | Antimicrobialsa | ECOFFb | No. of phenotypically resistant isolates c | AMR genes and mutations | Concordance between genotype and phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Fluoro)quinolone | NAL (but not CIP.) | >16 μg/ml | 1 | gyrA 2 p.T86I (n = 1) | |

| CIP (but not NAL.) | >0.5 μg/ml | 1 | gyrA 2 p.T86I + gyrA p.T86V (n = 1) | 100% (42/42) c | |

| CIP + NAL | 40 | gyrA 2 p.T86I (n = 33); gyrA 2 p.T86I + gyrA p.T86I (n = 7) | |||

| Macrolide | ERY | >8 μg/ml | 30 | 23S r.2075A > G (n = 30) | 100% (30/30) |

| Aminoglycoside | GEN | >2 μg/ml | 17 | aph(2″)-Ib + aph(3′)-III, + aac(6′)-Im (n = 9); aph(3′)-III (n = 7) | 94.1% (16/17) |

| Aminoglycoside | STR | >4 μg/ml | 18 | ant(6)-Ia (n = 5); ant(6)-Ia + rpsL p.K43R (n = 2); ant(6)-Ia + aph(3′)-III (n = 3); aph(2″)-Ib + aph(3′)-III + aac(6′)-Im + ant(6)-Ia (n = 7) | 94.4% (17/18) |

| Tetracycline | TET | >2 μg/ml | 29 |

tet(O) (n = 8) tet(O/32/O) (n = 20) |

96.5% (28/29) |

CIP, Ciprofloxacin; ERY, erythromycin; GEN, Gentamicin; NAL, Nalidixic; STR, Streptomycin; TET, Tetracycline.

EUCAST epidemiological cut-off values (ECOFF) for Campylobacter coli; resistant phenotype = non-wild-type.

Overall concordance for the (fluoro)quinolone group.

Although most campylobacteriosis cases are self-limiting, ciprofloxacin and erythromycin are recommended as empirical therapy to treat severe cases (Bolton, 2015). Our results from the UAE retail chicken align with other reports from different countries, raising the alarm about the emergence of AMR in thermophilic Campylobacter, mainly against fluoroquinolones in C. jejuni and notably against erythromycin in C. coli (Kaakoush et al., 2015; Asuming-Bediako et al., 2019). The high resistance rates for fluoroquinolones and erythromycin in the present study might be attributed to the common use of these antibiotics in UAE poultry farms. Stewardship programs to optimize the use of antibiotics in poultry production are essential for the future of animal and public health (Pinto Ferreira et al., 2022).

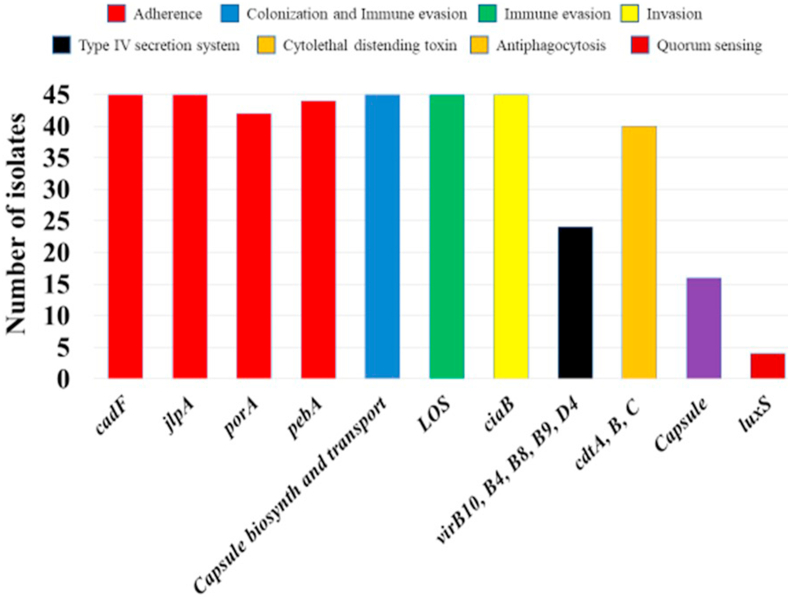

4.3.4. Virulence markers in C. coli from retail chicken

The prevalence of virulence genes detected among genomes of the 45 C. coli are presented in Fig. 4. In silico analyses revealed a range of seven to 11 virulence factors per each C. coli isolate. Some of these factors were prevalent in all (n = 45) of the isolates, and these were associated with adherence (cadF and jlpA), colonization and immune evasion (capsule biosynthesis and transport and lipooligosaccharides (LOS)), and invasion (ciaB). The results observed for the former genes are aligned with findings reported by several studies that such genes were detected in most of the strains associated with clinical cases (Zhang et al., 2003; Tedersoo et al., 2022).

Fig. 4.

Frequency of the in silico predicted virulence factors on genomes of 45 Campylobacter coli isolated from chilled chicken carcasses sampled from United Arab Emirates supermarkets.

The cytolethal-distending toxins (CDT), encoded by the cdtABC operon, was present in 88.8% (40/45) of the isolates. Previous studies have indicated a similarly high prevalence of CDT in Campylobacter recovered from patients with life-threatening diarrhea (Tegtmeyer et al., 2021). Additionally, about half (53.3% (24/45)) of the characterized C. coli isolates carried type 4 secretion system (T4SS) genes: virB4, virB8, virB9, virB10, and virD4. T4SS is encoded by genes present on the pVir plasmid, known for its potential role in intestinal epithelial adhesion and invasion. Plasmid pVir has also been hypothesized to facilitate the events of horizontal gene transferability that could add to increased virulence and fitness of some campylobacters (Mihaljevic et al., 2007). It is important to note that yet the role of many of the genes linked to the virulence potential of Campylobacter are not fully understood in the development of gastroenteritis (Bolton, 2015).

5. Conclusion

Campylobacter coli was found to be the most common species detected in retail broiler chicken carcasses in the UAE. Genomic data provided further insight on virulence and resistance profiles in a representative subset of C. coli for the first time in the UAE, a country among the leading markets for the per capita consumption of broiler meat. Our study reveals a disturbing pattern of AMR to quinolones and macrolides among C. coli, and we report a high resistance rate to tetracycline and aminoglycosides. The insight obtained from the present study provided a piece of evidence that help with filling the gap in the epidemiology of AMR in Campylobacter in the UAE. The use of WGS adds value to the surveillance of Campylobacter and can be considered a tool to support future One Health AMR surveillance from farm to fork.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ihab Habib: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Mohamed-Yousif Ibrahim Mohamed: Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration. Akela Ghazawi: Formal analysis, Software, Visualization. Glindya Bhagya Lakshmi: Investigation, Project administration. Mushtaq Khan: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Dan Li: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Shafi Sahibzada: Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The work was funded by the United Arab Emirates University (UAEU)-Asian University Alliance (AUA) grant number 12R009. The grant was facilitated through the UAEU-Zayed Center for Health Sciences. The funders had no role in the study design, data analysis, publishing decisions, or manuscript preparation.

Handling Editor: Siyun Wang

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2023.100434.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Alarjani K.M., Elkhadragy M.F., Al-Masoud A.H., Yehia H.M. Detection of Campylobacter jejuni and Salmonella typhimurium in chicken using PCR for virulence factor hipO and invA genes (Saudi Arabia) Biosci. Rep. 2021;41 doi: 10.1042/BSR20211790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura H., Sakata J., Nakamura H., Yamamoto S., Murakami S. Phylogenetic diversity and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter coli from humans and animals in Japan. Microb. Environ. 2019;34:146–154. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME18115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asuming-Bediako N., Kunadu A.P., Jordan D., Abraham S., Habib I. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Campylobacter jejuni in raw retail chicken meat in Metropolitan Accra, Ghana. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022;376 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2022.109760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asuming-Bediako N., Parry-Hanson Kunadu A., Abraham S., Habib I. Campylobacter at the human-food interface: the African perspective. Pathogens. 2019;8 doi: 10.3390/pathogens8020087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baré J., Uyttendaele M., Habib I., Depraetere O., Houf K., De Zutter L. Variation in Campylobacter distribution on different sites of broiler carcasses. Food Control. 2013;32:279–282. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton D.J. Campylobacter virulence and survival factors. Food Microbiol. 2015;48:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl L.G., Joensen K.G., Osterlund M.T., Kiil K., Nielsen E.M. Prediction of antimicrobial resistance in clinical Campylobacter jejuni isolates from whole-genome sequencing data. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021;40:673–682. doi: 10.1007/s10096-020-04043-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis M., Soumet C., Rivoal K., Ermel G., Blivet D., Salvat G., Colin P. Development of a m-PCR assay for simultaneous identification of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1999;29:406–410. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1999.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety) A., European Centre for Disease P., Control The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2019-2020. EFSA J. 2022;20 doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2022.7209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib I., Mohamed M.I., Khan M. Current state of Salmonella, Campylobacter and Listeria in the food chain across the Arab countries: a descriptive review. Foods. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/foods10102369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib I., Coles J., Fallows M., Goodchild S. A baseline quantitative survey of Campylobacter spp. on retail chicken portions and carcasses in metropolitan Perth, Western Australia. Foodb. Pathog. Dis. 2019;16:180–186. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2018.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib I., Uyttendaele M., De Zutter L. Evaluation of ISO 10272:2006 standard versus alternative enrichment and plating combinations for enumeration and detection of Campylobacter in chicken meat. Food Microbiol. 2011;28:1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry I., Reichardt J., Denis M., Cardinale E. Prevalence and risk factors for Campylobacter spp. in chicken broiler flocks in Reunion Island (Indian Ocean) Prev. Vet. Med. 2011;100:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull D.M., Harrell E., van Vliet A.H.M., Correa M., Thakur S. Antimicrobial resistance and interspecies gene transfer in Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni isolated from food animals, poultry processing, and retail meat in North Carolina, 2018-2019. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaakoush N.O., Castano-Rodriguez N., Mitchell H.M., Man S.M. Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015;28:687–720. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Wang Y., Shen J., Zhang Q., Wu C. Tracking Campylobacter contamination along a broiler chicken production chain from the farm level to retail in China. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014;181:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majowicz S.E., Panagiotoglou D., Taylor M., Gohari M.R., Kaplan G.G., Chaurasia A., Leatherdale S.T., Cook R.J., Patrick D.M., Ethelberg S., Galanis E. Determining the long-term health burden and risk of sequelae for 14 foodborne infections in British Columbia, Canada: protocol for a retrospective population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaljevic R.R., Sikic M., Klancnik A., Brumini G., Mozina S.S., Abram M. Environmental stress factors affecting survival and virulence of Campylobacter jejuni. Microb. Pathog. 2007;43:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed H.O., Stipetic K., Salem A., McDonough P., Chang Y.F., Sultan A. Risk of Escherichia coli O157:H7, non-O157 shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, and Campylobacter spp. in food animals and their products in Qatar. J. Food Protect. 2015;78:1812–1818. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauta M., Hill A., Rosenquist H., Brynestad S., Fetsch A., van der Logt P., Fazil A., Christensen B., Katsma E., Borck B., Havelaar A. A comparison of risk assessments on Campylobacter in broiler meat. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009;129:107–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocejo M., Oporto B., Lavin J.L., Hurtado A. Whole genome-based characterisation of antimicrobial resistance and genetic diversity in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli from ruminants. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:8998. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88318-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyarzabal O.A., Backert S., Nagaraj M., Miller R.S., Hussain S.K., Oyarzabal E.A. Efficacy of supplemented buffered peptone water for the isolation of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli from broiler retail products. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2007;69:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto Ferreira J., Battaglia D., Dorado Garcia A., Tempelman K., Bullon C., Motriuc N., Caudell M., Cahill S., Song J., LeJeune J. Achieving antimicrobial stewardship on the global scale: challenges and opportunities. Microorganisms. 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10081599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampers I., Habib I., Berkvens D., Dumoulin A., Zutter L.D., Uyttendaele M. Processing practices contributing to Campylobacter contamination in Belgian chicken meat preparations. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008;128:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreyer M.E., Olivero C.R., Rossler E., Soto L.P., Frizzo L.S., Zimmermann J.A., Signorini M.L., Virginia Z.M. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli identified in a slaughterhouse in Argentina. Curr Res Food Sci. 2022;5:590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.crfs.2022.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella S., Soncini G., Ziino G., Panebianco A., Pedonese F., Nuvoloni R., Di Giannatale E., Colavita G., Alberghini L., Giaccone V. Prevalence and quantification of thermophilic Campylobacter spp. in Italian retail poultry meat: analysis of influencing factors. Food Microbiol. 2017;62:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedersoo T., Roasto M., Maesaar M., Kisand V., Ivanova M., Meremae K. The prevalence, counts, and MLST genotypes of Campylobacter in poultry meat and genomic comparison with clinical isolates. Poultry Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.101703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegtmeyer N., Sharafutdinov I., Harrer A., Soltan Esmaeili D., Linz B., Backert S. Campylobacter virulence factors and molecular host-pathogen interactions. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2021;431:169–202. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-65481-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) 2021. Poultry and Products Annual.https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/united-arab-emirates-poultry-and-products-annual-2 Available via. [Google Scholar]

- Vinueza-Burgos C., Wautier M., Martiny D., Cisneros M., Van Damme I., De Zutter L. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance and genetic diversity of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni in Ecuadorian broilers at slaughter age. Poultry Sci. 2017;96:2366–2374. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker L.J., Wallace R.L., Smith J.J., Graham T., Saputra T., Symes S., Stylianopoulos A., Polkinghorne B.G., Kirk M.D., Glass K. Prevalence of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni in retail chicken, beef, lamb, and pork products in three Australian states. J. Food Protect. 2019;82:2126–2134. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-19-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Dong Y., Deng F., Liu D., Yao H., Zhang Q., Shen J., Liu Z., Gao Y., Wu C., Shen Z. Species shift and multidrug resistance of Campylobacter from chicken and swine, China, 2008-14. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71:666–669. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Lin J., Pereira S. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter in animal reservoirs: dynamics of development, resistance mechanisms and ecological fitness. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2003;4:63–71. doi: 10.1079/ahr200356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.