Abstract

Around the world, tabloid newspapers are routinely surrounded by a moral and cultural panic. They are criticised for lowering standards of journalism and privileging sensation above substance, diverting readers from serious news to entertainment, or foregoing ethical principles. However, scholarship about tabloids have also highlighted the ways in which these papers are frequently better attuned to their readers’ everyday lived experience. In South Africa, tabloid newspapers have also received much criticism in the past for their perceived superficial treatment of important news. This article examines South African tabloid newspapers’ coverage of the Covid-19 pandemic, focussing specifically on a case study of the national newspaper the Daily Sun. The national Daily Sun newspaper boasts the country’s largest circulation figures. Through a quantitative content analysis of 1050 online news stories in the Daily Sun, we found that unlike mainstream front-page news reporting which was largely episodic, negative and alarmist, the majority of Daily Sun coverage was thematic and neutral. Daily Sun news coverage countered Covid-19 related misinformation and provided contextual coverage, with a large focus on the social impacts of Covid-19. The analysis concludes that despite the popular discourse of the reporting, Daily Sun reporting on Covid-19 provided readers with access to information and a focus on the micro aspects of the pandemic versus broader political issues and the views of political or scientific elites.

Keywords: content analysis, coronavirus, Covid-19, health reporting, South African media, tabloid newspapers

Introduction

Since the onset of the pandemic, a range of academic researchers have explored media coverage of Covid-19 around the world, including Africa (e.g. the special issues of Journal of African Media Studies devoted to African media coverage of the pandemic, Ndlela, 2021). Understanding media coverage of the pandemic is important because of the potential social impact of the media. The media can play a key role during such health pandemics as they serve as a key source of health information, as well as influencing the attitudes of the public (Sell et al., 2016). In the South African context, Wasserman et al. (2021) analysed mainstream news coverage of the initial stages of the pandemic, finding that most reporting on newspaper front pages was episodic, negative and alarmist; with almost half of the reports also using sensationalist language in their coverage. Moreover, this study found that in their front page reports, mainstream South African newspapers provided very little or no health information or debunking of myths, foregrounded elite sources, and framed the pandemic primarily as a government policy, health and security issue. The question arises: if mainstream newspapers, with their reputation for ‘quality’ news and their serious, ‘objective’ approach, was found to cover the pandemic in such a sensationalist or alarmist way, what would tabloid coverage – usually associated with exaggerated, dramatic and emotional approaches to news coverage – then look like?

Tabloids are often criticised for lowering standards of journalism and privileging sensation above substance, diverting readers from serious news to entertainment, or foregoing ethical principles (Sparks, 2000). While the term ‘tabloid’ originally referred to the physical size of the newspaper (from ‘tablet’, see Franklin et al., 2005), gradually these papers developed a distinctive genre of journalism, ‘the human- interest, graphically told story, heavy on pictures and short, pithy, highly stereotyped prose’ (Bird, 1992: 8). Later, this specific style of journalism became applied a genre or style of news, a ‘particular kind of formulaic, colorful narrative related to, but usually perceived as distinct from standard, “objective” styles of journalism’ which is usually seen as ‘inferior, appealing to base instincts and public demand for sensationalism’ (Bird, 2009: 40) with a detrimental influence on democracy (Sparks, 2000) and diverting their readers’ interest away from politics towards sports, scandal and entertainment (Curran, 2003: 92–93). This conflation between the format, style and notions of journalistic ‘quality’ which the term ‘tabloid’ and ‘tabloidization’ can be taken to refer to, has also led to a derogatory use of these terms to criticise what is seen from an elite perspective as a decline in standards (Örnebring and Jönsson, 2007: 283).

The Covid-19 pandemic again raised questions about how tabloid coverage of a major health crisis would differ from that of ‘quality’ news, especially given the former’s propensity for emotionality during a period where social anxieties were high (Eisele et al., 2022) and their tendency for exaggeration and scapegoating (Kleut and Sinkovic, 2020).

In South Africa, tabloid newspapers have also received much criticism in the past, often framed in terms of what has been perceived as their potential to undermine democratic values and a perceived superficial treatment of important news. Tabloids’ emergence on the South African post-apartheid media landscape was a commercial response to the entry of Black South Africans to an upwardly mobile, consumerist class and their potential formation of a new reading public (Steenveld and Strelitz, 2010). The first of these tabloids, the Daily Sun, was launched in 2002, and created a mass readership of poor Black working class readers, giving voice to a large section of the population who had remained ‘on the margins of the post-apartheid mediated public sphere’ (Wasserman, 2008). In the wake of the Daily Sun’s commercial success, other tabloids were launched – the Kaapse Son and the Daily Voice. But despite creating more inclusivity in media access and use, tabloids were initially not welcomed by the journalistic fraternity. Because of this journalistic genre’s reputation for bypassing conventional journalistic norms such as objectivity, neutrality and truth-telling through their largely sensationalist, opinionated and seemingly far-fetched stories, tabloids were seen as a threat to journalistic standards and the occupation’s reputation (Wasserman, 2008: 789). When the tabloids were first launched in South Africa, the country’s professional journalist organisation, the South African National Editors’ Forum, media monitoring groups, academics and commentators criticised them for tarnishing the image of professional journalists (Wasserman, 2008: 789). The response of mainstream South African news organisations could be seen as a form of ‘paradigm repair’ following a series of ethical lapses, to reclaim their position as legitimate news platforms (Wasserman, 2006).

However, scholarship about tabloids have also highlighted the ways in with these papers are frequently better attuned to their readers’ everyday lived experience than elite publications, are more responsive to working class struggles, forge closer relationships with their readers and present political matters in ways that resonate with their readers’ concerns (Wasserman, 2010; Bird, 1992; Fiske, 1992). Cultural studies scholars have argued that tabloids express the everyday lived experience of marginalised publics, serving as a site of resistance against cultural hegemony and subvert the high culture/low culture social hierarchy (Bird, 1992; Fiske, 1992). As such, tabloid media can contribute to a sense of belonging among their audiences, based on shared identity, values and community (Gripsrud, 2008). In the case of South Africa in particular, tabloids present a view on news events that does not shy away from emotional responses to the violent and precarious lived experience of the poor in a highly unequal society. But tabloids often also do ‘serious’ journalism more thoroughly than their mainstream counterparts by virtue of them tending to be more closely connected to the communities they report on. Despite widespread critiques of tabloids, Hinkle and Elliott (1989) found that US supermarket tabloids of the 1980s were more likely to cover stories about medicine and health than mainstream papers, devoting many of their headlines to coverage of science. Although South African tabloids followed their counterparts in the Global North in terms of format and approach, their subject material was quite different and much more serious. Their focus on stories about the impact of crime, corruption and dysfunctional local government on poor and working class citizens, set them apart from the funny and joking tone that is usually associated with their Northern counterparts. This focus on serious news, albeit presented in an accessible and dramatic format, led Wasserman (2010) to characterise South African tabloid coverage as pertaining to the ‘politics of the everyday’. There has been little academic attention to tabloid news reporting of Covid-19 specifically. One exception was the work of Kleut and Sinkovic (2020), who look specifically at tabloid news framing of the pandemic in Serbia. They found that the most prominent frames were prevention and human-interest frames; with citizens who undermine state measures presented as villains, and China and Russia portrayed as the heroes in the fight against the virus.

Given this gap in research, and the potentially important role that tabloid newspapers could play in raising awareness about Covid-19 among their readers – who are under-served by other mainstream commercial newspapers – the question arises as to how South African tabloids covered the pandemic.

Methodology

Our analysis of tabloid news coverage of Covid-19 rests on a case study approach, focussing on the Daily Sun. This is the largest tabloid newspaper in South Africa with a readership of 3.8 million (PAMS, 2017). Using the keywords ‘Coronavirus’, ‘Covid-19’ and ‘vaccine’, a sample of 1050 stories was selected from the Daily Sun website during the period March 2020-August 2021. The dataset was cleaned and duplicates removed to create a final dataset of stories. While the Daily Sun is primarily a print publication, like many other news publications they seek to increase their reach via their website and social media accounts. Online journalism usually supplements print media, and most traditional print newspapers have online versions which replicate offline content online with little user interactivity (Bosch, 2010). In the case of the Daily Sun, print versions of stories are published on the website, and there is no opportunity for reader comments as this function is disabled.

A quantitative and qualitative content analysis methodology was employed as ‘a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from data to their context’ (Krippendorff, 2018: 403) and to make inferences about media representation (Deacon, 2021). A coding schedule was based on the previous work of Wasserman et al. (2021), to allow for some comparison of media coverage between broadsheet mainstream newspapers and the Daily Sun tabloid’s online stories. One thousand fifty stories were found between March 2020 and August 2021 and these were coded manually. This timeframe was selected as it starts with the outbreak of the pandemic in South Africa and the first lockdown in March 2020 and concludes as the ‘third wave’ of the pandemic wound down in the third quarter of 2021. Although the sample excludes the ‘fourth wave’ which resulted from the highly infectious ‘Omicron’ variant detected towards the end of 2021, this sample spans three ‘waves’ of the pandemic in South Africa as well as various stages of lockdown declared in response to it. The quantitative content analysis was complemented by a qualitative content analysis and close reading of a smaller sample of 130 stories across this timeframe, selected via purposive sampling.

The online news stories were coded for 14 variables including: headline, date, narrative modes, type of reporting, frame of story, primary focus of story, use of language – emotional appeal, whether there was sensationalist language or misinformation, provision of health information, sources quoted, overall tone of article and whether Covid-19 or the vaccine was the main focus of the article.

Findings and discussion

Narrative modes of coverage

Coverage of Covid-19 in the Daily Sun was analysed to establish the extent to which it subscribed to three primary narrative modes as put forward by Ungar (2008): Sounding the alarm, mixed messages and hot crisis and containment. Sounding the alarm refers to the (usually early) stage of media coverage where fearful claims are most dominant, in an attempt to convince the public that the threat is real and critical; and focusing on the most fearful aspects of the crisis. The second phase, described by Ungar (2008) as ‘mixed messages’, involves a mode of coverage which includes continuation of the earlier narrative mode combined with efforts to reassure, including highlighting and discussing national plans and scientific information to counter the threat. This phase of coverage aims to mitigate the earlier ‘sounding the alarm’ phase by reassuring the public that the crisis is under control. The third narrative mode, the hot crisis and containment stage of media coverage refers to efforts to ‘undo’ the original fearful claims (Ungar, 2008).

With respect to the Daily Sun’s coverage of Covid-19, the majority (39.1%) of stories fell into the mixed messages category, 36.2% sounded the alarm and 24.7% were hot crisis and containment. This range of narrative modes is not surprising given that the dataset spans a range of the pandemic from the initial emergence of the virus through to the availability of the vaccine. However, given existing literature which highlights South African tabloid journalism’s tendency towards the use of a melodramatic aesthetic to attract audiences (Steenveld and Strelitz, 2010), it is surprising that such a small number of stories sounded the alarm. Tabloids are usually criticised for sensationalist coverage, defined as ‘a tendency to sensationalize news, in which tabloid news topics displace socially significant stories and flashy production styles overpower substantive information’ (Wang, 2012: 712). Sensationalism has been primarily conceived of in terms of story content, and ‘their potential to provoke more sensory and emotional reactions’ as well as to ‘startle and arouse public emotion’ (Wang, 2012: 713). In this instance, while we did not code specifically for sensationalist content, the ‘sounding the alarm’ mode would be closest in narrative form. While the qualitative analysis confirmed that there was no overt use of sensationalist language, it should be noted that reporting often relied on what Steenveld and Strelitz (2010) describe as shock aesthetics, that is, ‘the use of huge colourful headlines, exclamations, italics, capitalization, etc’ (p. 536). This is in line with the mode of reporting of tabloid newspapers.

The majority of stories fell into the mixed messages category, with elements of both fear but also reassurance, primarily highlighting the systems in place to cope with the pandemic, for example, ‘Ramaphosa confirms vaccine donations from US!’ (13/06/2021). Examples of stories sounding the alarm included phrases such as ‘Covid-19 and lockdown have knocked the economy hard and many people lost their jobs’ (32/2/2021); and ‘Bosses use Covid-19 to cut wages’ (25/02/2021).

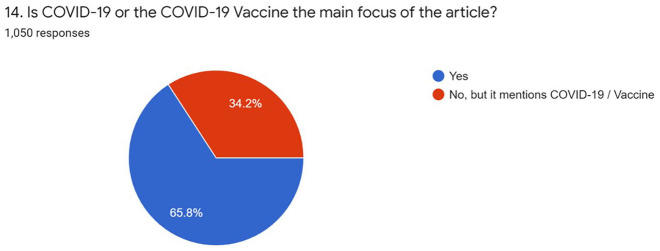

Not all Covid-19 related stories dealt specifically with the pandemic. For example, ‘Rage over Eskom hike’ (18/02/2021) says ‘Eskom will be putting salt on the wounds of South Africans who are struggling to make ends meet after they were left financially paralysed by the impact of the covid-19’. The pandemic was thus often used as a framing tool to highlight issues that were exacerbated by the Covid-19 context. Altogether 65.8% of stories had Covid-19 as the primary focus, while the remaining 34.2% mentioned either Covid-19 or the vaccine though this was not the main focus of the story. This mode of contextual reporting moved beyond focussing simply on the pandemic and the immediacy of the news; instead framing Covid-19 more contextually to increase its relevance for the newspaper’s readership. Unlike mainstream media coverage of the pandemic which was alarmist and sensationalist (Wasserman et al., 2021), the Daily Sun, surprisingly, provided much more contextual coverage, placing the pandemic into a frame of reference and focussing on its social impact, to increase relevance for its readership in their everyday lives. This aspect of relating news events to readers’ lived experience is typical of tabloids’ reporting style. However, similar to mainstream media reporting which provided little practical information on how to limit the spread of the virus (Wasserman et al., 2021), tabloid reporting also fell short in this regard.

Figure 1.

The main focus of the story

Types of reporting

The vast majority (90.5%) of news stories in the Daily Sun were thematic versus episodic. Thematic reporting refers to the fact that they provided background information to the pandemic, provided a wide-angle lens, synthesis and were overarching. Thematic reporting is usually more in-depth, places events into context and tends to analyse trends and focus on solutions. In contrast, episodic reporting provides a telephoto lens on an issue, typically focussing on single specific event-driven cases and sensational and emotional appeals (Iyengar, 1991). In their analysis of front page stories of mainstream South African newspaper coverage of Covid-19, Wasserman et al. (2021) showed that most publications reported in an episodic rather than a thematic manner.

Suprisingly, given the generally negative perception of tabloid reporting as focussing on sensational aspects of news events, only 9.5% of the stories analysed fell into this episodic category and most Daily Sun reporting of Covid-19 was thematic. Stories tended to give context and frame stories with backdated context and information on the pandemic.

Framing of stories

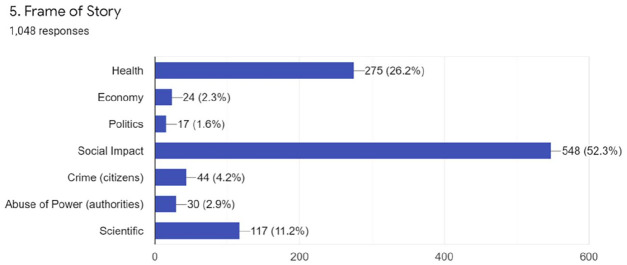

Reports on Covid-19 were framed as follows: health, the economy, politics, social impact, crime (by citizens), abuse of power (by authorities) and a scientific focus of the story. Of the 1050 stories coded, the social impact frame was the most prevalent with 52.3% (548 news stories). The political frame recorded the lowest number of stories at 1.6% (17 news stories). This is not surprising given the frequent criticism that tabloid newspapers divert their readers’ attention away from formal political content towards entertainment. However, in the context of South African tabloid news, ‘political’ reporting should also be understood as having a wider remit. Their close relationship to their audience enables South African tabloids to ‘articulate the politics of the everyday for those readers for whom formal politics are often far removed from their lived experience’ (Wasserman, 2008: 1).

Examples of stories framed by the lens of social impact include ‘KZN teachers will not return to school tomorrow’ (24/05/2020″ which highlighted the lack of PPE and safety plans in government schools; and ‘Government should do better’ (06/01/2021) to encourage the awarding of Covid-19 grants. The Daily Sun also covered stories about a gang ceasefire during Covid (20/04/2020) and a focus on celebrities’ responses to the pandemic. For example ‘Nyandoro auctions jerseys in fight against Coronavirus’ (21/04/2020) focused on how the former Mamelodi Sundowns soccer player was raising money to buy sanitiser and masks for vulnerable communities.

This is a clear reflection of how tabloid newspapers report on the ‘politics of the everyday’ (Wasserman, 2008, 1). The Daily Sun’s coverage of the pandemic was through the lens of popular culture – celebrities and sportspeople’s responses as opposed to privileging the voices of political elites. The story ‘Corona forces Phiri to postpone map games’ (16/04/2020) focuses on how a former Bafana Bafana midfielder was forced to postpone an annual event due to Covid-19 while also reflecting on his concerns that Alexandra residents were not adhering to the national lockdown. The story ‘Anthem to honour fallen loved ones’ (23/01/2021) describes a collaboration between two musicians to produce a single to commemorate those who died from Covid-19. Similarly the story ‘Big Zulu adds his voice’ (19/04/2020) focused on how the rapper Big Zulu had released a song titled ‘Lockdown’. This type of reporting also highlights the use of ‘personalization as a rhetorical device’ (Steenveld and Strelitz, 2010: 535) as well as the prevailing populist discourse of tabloid newspapers. This personalised approach creates an ‘intimate relationship between the paper and its readers’ (Steenveld and Strelitz, 2010: 542).

The other frames recorded were as follows: health 26.2% (275 news stories), science 11.2% (117 news stories), crime (by citizens) 4.2% (44 news stories), abuse of power (by authorities) 2.9% (30 news stories, and the economic frame was 2.3% (24 news stories). Given the nature of the pandemic, it is not surprising that the majority of stories on Covid-19 were framed as a health issue; and given the typical socio-economic demographic of tabloid readership, that only 2.3% of stories were framed through the lens of the economy. Given the focus on tabloid newspapers and the Daily Sun’s emphasis on the everyday, as highlighted above, it is surprising that there was not a larger focus on the abuse of power by authorities.

Figure 2.

How tabloid stories were framed

From the stories coded, 1.7% (18 news stories) fell into the category of highlighting causes of the pandemic, followed by predictions 2% (21 news stories), solutions 22.8% (238 news stories), responsibilities 12.9% (135 news stories). A focus on impacts of the pandemic recorded the highest number of stories at 60.5% (631 news stories). Examples of stories providing solutions to the pandemic included: ‘More mass screening’ (15/04/2020) which encouraged more people to screen and test for Covid-19; and ‘Why I wear Coronavirus mask’ (14/04/2020) which covers #Projectpenismask, a mask design with tiny phallic symbols, to remind strangers to keep their distance in public spaces. Stories which focused on impacts of Covid-19 on ordinary citizens included ‘Dr working in three hospitals tests positive for Corona virus’ (13/04/2020), ‘How I keep my 10 kids safe from Corona!’ (09/04/2020), and ‘The whole village calls us Corona’ (10/04/2020) about a family stigmatised due to illness.

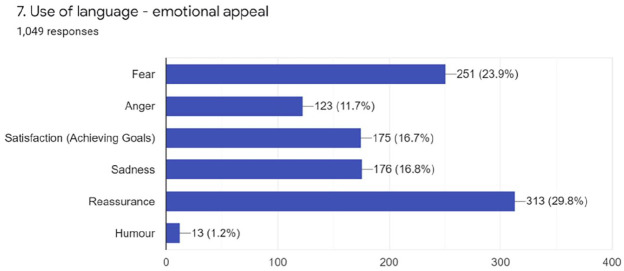

The use of language and emotional appeals

We found six emotional appeals present in the stories coded: fear, anger, satisfaction (achieving goals), sadness, reassurance and humour. Two hundred fifty-one (23.9%) news stories used fear as the emotional appeal, anger was found in 123 news stories (11.7%), satisfaction (achieving goals) in 175 news stories (16.7%), sadness in 176 news stories (16.8%), reassurance in 313 news stories (29.8%) and humour was found in only 13 news stories (1.2%). The stories which attempted to reassure readers included, ‘No shortage of hospital beds!’ (10/06/2021), ‘Criselda home and recovering well’ (07/06/2021) referring to the Covid recovery of media personality Criselda Kananda; and ‘No one is the master of Covid-19!’ (09/06/2021) in which readers were assured that vaccination would prevent death.

In mainstream media coverage of Covid-19, most South African newspapers used sensationalist language (Wasserman et al., 2021), in line with research that has shown that typically mainstream news organisations tend to contribute towards public fear and panic by focussing on coverage that emphasises risks and uncertainties (Kilgo et al., 2019). It is thus not surprising that the largest emotional appeal used in the tabloid coverage also relies on fear appeals.

Tabloids have long been associated with an emotional, melodramatic style of writing – often contrasted unfavourably with the more distanced, measured style of mainstream, ‘quality’ newspapers. Tabloid culture ‘prefers heightened emotionality’ and ‘resists “objectivity”, detachment, and critical distance’ (Glynn, 2000, p.7). While normative assessments of tabloids have often decried their deviance from the idealised Habermasian public sphere, cultural studies scholars have argued that the emotional approach may resonate more strongly with a view on the world as it is experienced by ‘ordinary people’ struggling to make sense of their unpredictable, precarious and often tragic circumstances than the cool, rational explanations offered by the traditional news narrative genre. (Van Zoonen, 2000, p.6). Despite the pejorative connotations attached to the melodramatic style of tabloids, ‘tabloid journalism has also been shown to provide an alternative public sphere for counterpublics where sensation and emotion can be read as a critique against economic and political elites (Ornebring and Jonsson, 2007, p.290).

Several stories deliberately debunked rumours and myths about the pandemic. For example, ‘Six interesting coronavirus conspiracy theories’ (18/07/2020) highlights common myths as ‘conspiracy theories’; while ‘Mkhize: Vaccine is not from the devil’ (11/02/2021) attempts to debunk rumours of the vaccine being dangerous. A story with the headline ‘You can’t get coronavirus from mosquitoes!’ (06/03/2020) similarly debunks several myths regarding transmission by mosquitoes, drinking bleach as a cure and goods being manufactured in China transmitting the virus, among others. However, while there was no overt misinformation, there was often coverage of stories containing myths. These types of stories were reported on neutrally, quoting others, without any claims as to whether their claims were true or false. For example, ‘Prophet: If we pray at 9pm, Corona will go away!’ (09/04/2020) describes this claim by a local ‘prophet’ without any endorsement or rejection of his claims.

The overall tone of the stories coded was mostly neutral (43.5%), with 29.4% of stories coded as positive and 27.1% coded as negative. Positive stories included those such as ‘Breakthrough in Covid-19 treatment promising-Mkhize’ (17/06/2020) and ‘Mzansi 1-million Covid-19 test milestone!’ (11/06/2020). Stories with a more negative frame included those such as ‘Virus destroyed our lives’ (14/08/2021), ‘Gogo (grandmother) cries for dead grandson!’ (02/08/2021) and ‘Covid 4th wave rearing its ugly head’ (07/08/2021).

Figure 3.

Which emotional appeals were used

A diverse range of sources were quoted though government officials made up the bulk of cited sources at 41.2%, followed by citizens (25.3%), politicians (9.7%), corporates (8.2%) experts (6.4%), law and security enforcement officials (4.9%). Given the personalisation of Covid news and focus on celebrity, it is surprising that government sources make up such a large percentage of news sources over citizens or even health agency officials. The focus of stories was usually on either citizens or popular celebrities, but they only made up 25.3% of cited sources. This prominence of government sources may be a result of the high reliance of news outlets on the regular communiques from government about lockdown levels, infection rates and number of deaths – this information was centrally collated and controlled, and government to some extent exercised a monopoly over that information. The prevalence of government sources is thus a result of convenience – this information is usually sent directly to media outlets – versus citizen sources which require greater on the ground resources for journalists to access communities physically, often difficult during the pandemic due to limitations on movement and the risks of transmission. President Cyril Ramaphosa gave regular televised addresses to the public (which later became known as ‘family meetings’, Feltham, 2021) mainly used to announce different lockdown levels based on infection rates. He also received criticism for its one-sidedness as these televised meetings did not allow for questions or interactions with journalists (Feltham, 2021). Nevertheless, the Daily Sun’s emphasis on government communication does not necessarily imply approval of or trust in the government’s handling in a pandemic. An online survey of South African social media users (Wasserman and Madrid-Morales, 2021) found that South Africans are more likely to trust scientific sources, such as doctors and the World Health Organisation, than their own government; and that most disapprove of the government’s handling of the pandemic.

Healthcare workers, civil society/NGOs and faith-based organisation sources each made up 3.7% of the total sources; while news organisations and journalists were only cited in 3.3% and health agency officials (World Health Organisation) in 1.2% of the stories coded.

Conclusion

Steenveld and Strelitz (2010) highlight that the key aspects of popular media like tabloid newspapers are their ‘appeal to a wide public that cuts across classes, and its consideration of traditionally defined “public” issues, but its treatment of these in a way that is not typically associated with the voice of “highbrow” journalism’ (534). Despite critiques of the quality of journalism, tabloids remain ‘part of a continuum of public communication that reflects ordinary people’s very different life worlds in contemporary South Africa’ (Steenveld and Strelitz, 2010: 543).

In its coverage of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Daily Sun reflected these characteristics. It highlighted the impact of the pandemic on ordinary people and articulated their everyday experiences of its effects. The Daily Sun reporting of Covid-19 during the height of the pandemic demonstrated what Steenveld and Strelitz (2010) refer to as service and campaign journalism, focussing on ‘news you can use’ and providing ‘guidance to improve daily life’ (p. 536). However, despite this focus on everyday lived experience of the pandemic, the Daily Sun’s narrative approach was not overly alarmist, as might have been expected from a news genre with an inclination towards sensation and melodrama. The overall tone of the stories were neutral, while much of its reporting remained factual, to the extent that it even favoured the official viewpoints of government over and above other sources.

Tabloid news coverage of Covid-19 was less driven by mainstream normative news values, with a higher value placed on personalization of news and everyday popular culture. While the style and mode of address targets a working-class community and conform to typical shock aesthetics, Daily Sun coverage played a key role in highlighting the social impact of the pandemic by providing contextual reporting and showing how ordinary citizens were being impacted. Its choice for thematic rather than episodic reporting further provided its readers with the opportunity to stay engaged with topical matters regarding the pandemic in a sustained way. In this regard, the tabloid’s reputation for making news relevant to the everyday lives of their readers was also upheld during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/ or publication of this article: National Research Foundation (NRF), South Africa.

ORCID iDs: Tanja Bosch  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8093-1969

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8093-1969

Herman Wasserman  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2553-1989

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2553-1989

Contributor Information

Tanja Bosch, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

Herman Wasserman, Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

References

- Bird E. (1992) For Enquiring Minds: A Cultural Study of Supermarket Tabloids. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bird SE. (2009) Tabloidization: What is it, and does it really matter? In: Zelizer B. (ed.) The Changing Faces of Journalism: Tabloidization, Technology and Truthiness. New York: Routledge, pp.40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch T. (2010) Digital journalism and online public spheres in South Africa. Communication: South African Journal for Communication Theory and Research 36(2): 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Curran J. (2003) The press in the age of Globalization. In: Curran J, Seaton J. (eds) Power Without Responsibility. London: Routledge, pp.67–105. [Google Scholar]

- Deacon D, Pickering M, Golding P, Murdock G. (2021) Researching Communications: A Practical Guide to Methods in Media and Cultural Analysis. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. [Google Scholar]

- Eisele O, Litvyak O, Brändle VK, et al. (2022) An emotional Rally: Exploring Commenters’ responses to online news coverage of the COVID-19 crisis in Austria. Digital Journalism 10: 952–975. [Google Scholar]

- Feltham L. (2021) Pure politics: ‘Family meetings’ underline uncomfortable press relationship. Mail & Guardian, 29 August. Available at: https://mg.co.za/politics/2021-08-29-pure-politics-family-meetings-underline-uncomfortable-press-relationship/ (Accessed 23 March 2022)

- Fiske J. (1992) Popularity and the Politics of Information in P. Dahlgren and C. Sparks Journalism and Popular Culture. London: SAGE, pp.45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin B, Hamer M, Hanna M, et al. (2005) Key Concepts in Journalism Studies. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn K. (2000) Tabloid Culture: Trash Taste, Popular Power and the Transformation of American Television. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gripsrud J. (2008) Tabloidization, popular journalism, and democracy. In: Biressi A, Nunn H. (eds) The Tabloid Culture Reader. Maidenhead: Open University Press, pp.34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle G, Elliott WR. (1989) Science coverage in three newspapers and three supermarket tabloids. Journalism Quarterly 66(2): 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S. (1991) American Politics and Political Economy Series. Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kilgo DK., Yoo J, Johnson TJ. (2019) Spreading Ebola panic: Newspaper and social media coverage of the 2014 Ebola health crisis. Health Communication 34(8): 811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleut J, Sinkovic N. (2020) “Is it possible that people are so irresponsible?”: Tabloid news framing of the COVID-19 pandemic in Serbia. Sociologija 62(4): 503–523. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K. (2018) Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. London: SAGE publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ndlela MN. (2021) The coronavirus pandemic in Africa: Crisis communication challenges. Journal of African Media Studies 13(2): 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Örnebring H, Jönsson AM. (2007) Tabloid journalism and the public sphere: A historical perspective on tabloid journalism. Journalism Studies 5(3): 283–295. [Google Scholar]

- PAMS (2017) Publisher Audience Measurement Survey. Technical Report. April 2018. Available at https://www.bbrief.co.za/content/uploads/2018/04/PAMS-2017-Technical-Report.pdf (Accessed 4 July 2021).

- Sell TK, Boddie C, McGinty EE, et al. (2016) News media coverage of US Ebola policies: Implications for communication during future infectious disease threats. Preventive Medicine 93: 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks C. (2000) Introduction: The panic over Tabloid news. In: Sparks C, Tulloch J. (eds) Tabloid Tales—Global Debates Over Media Standards. Lanham, MD: Roman and Littlefield, pp.1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Steenveld L, Strelitz L. (2010) Trash or popular journalism? The case of South Africa’s Daily Sun. Journalism 11(5): 531–547. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar S. (2008) Global bird flu communication: Hot crisis and media reassurance. Science Communication 29(4): 472–497. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zoonen L. (2000) Popular culture as political communication an introduction. Javnost-The Public 7(2): 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang T. (2012) Presentation and impact of market-driven journalism on sensationalism in global TV news. International Communication Gazette 74(8): 711–727 DOI: 10.1177/1748048512459143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman H, Chuma W, Bosch T, Uzuegbunam CE, Flynn R. (2021) South African newspaper coverage of COVID-19: A content analysis. Journal of African Media Studies 13(3): 333–350. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman H. (2006) Tackles and sidesteps: normative maintenance and paradigm repair inmainstream media reactions to tabloid journalism. Communicare 25(1): 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman H. (2008) Attack of the killer newspapers! The ‘tabloid revolution’ and the future of newspapers in South Africa. Journalism Studies 9(5): 786–797. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman H. (2010) Tabloid Journalism in South Africa: True Story! Bloomington: Indiana University Press [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman H, Madrid-Morales D. (2021) What motivates the sharing of misinformation about China and Covid-19? A study of social media users in Kenya and South Africa. Available online at http://disinfoafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/What-Motivates-The-Sharing-of-Misinformation-about-China-and-COVID-19.pdf