Abstract

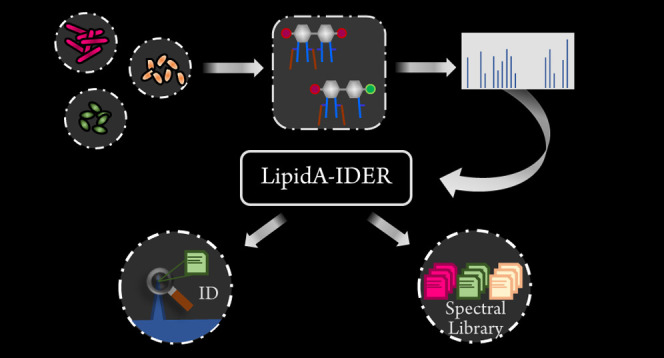

With the global emergence of drug-resistant bacteria causing difficult-to-treat infections, there is an urgent need for a tool to facilitate studies on key virulence and antimicrobial resistant factors. Mass spectrometry (MS) has contributed substantially to the elucidation of the structure-function relationships of lipid A, the endotoxic component of lipopolysaccharide which also serves as an important protective barrier against antimicrobials. Here, we present LipidA-IDER, an automated structure annotation tool for system-level scale identification of lipid A from high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (MS2) data. LipidA-IDER was validated against previously reported structures of lipid A in the reference bacteria, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Using MS2 data of variable quality, we demonstrated LipidA-IDER annotated lipid A with a performance of 71.2% specificity and 70.9% sensitivity, offering greater accuracy than existing lipidomics software. The organism-independent workflow was further applied to a panel of six bacterial species: E. coli and Gram-negative members of ESKAPE pathogens. A comprehensive atlas comprising 188 distinct lipid A species, including remodeling intermediates, was generated and can be integrated with software including MS-DIAL and Metabokit for identification and semiquantitation. Systematic comparison of a pair of polymyxin-sensitive and polymyxin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from a human patient unraveled multiple key lipid A structural features of polymyxin resistance within a single analysis. Probing the lipid A landscape of bacteria using LipidA-IDER thus holds immense potential for advancing our understanding of the vast diversity and structural complexity of a key lipid virulence and antimicrobial-resistant factor. LipidA-IDER is freely available at https://github.com/Systems-Biology-Of-Lipid-Metabolism-Lab/LipidA-IDER.

Gram-negative bacteria are protected from their environment by a unique and structurally complex dual bilayer membrane architecture. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS), the major component of the outer membrane, function as a permeability barrier against antimicrobials and are a key virulence factor.1−3 LPS comprise three distinct regions: a highly variable O-antigen domain, a glycan core, and a hydrophobic glycolipid, termed lipid A. Lipid A is further defined by its distinct diglucosamine backbone which can be substituted by fatty acyls (FAs) at four positions (2, 3, 2′, and 3′ carbons) and modified at two positions (1 and 4′ carbons) with headgroups, including phosphate, phosphoethanolamine (PEtN), hexosamine (HexN), and 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose (Ara4N).4,5 Less common variants, including the presence of unusual 2-amino-2-deoxy-gluconate and 2,3-diamino-2,3-dideoxyglucose moieties in the sugar backbone,6,7 exist. Structural variations of lipid A strongly influence its interactions with host receptors and consequently the potency of the immune response it elicits.8−10 Furthermore, lipid A remodeling is one of the key mechanisms of resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides, including polymyxins (PMXs).4 Development of antimicrobials that target this lipid A11−13 and the use of modified lipid A as potential vaccine adjuvants14,15 continue to be promising avenues for therapeutic interventions against Gram-negative bacterial infections. Comprehensive characterization of lipid A is hence critical for understanding its structure-function relationships in the context of virulence, antimicrobial resistance (AMR), and therapeutic designs.

With the development of data-dependent acquisition (DDA)16 and data-independent acquisition (DIA),17 comprehensive structural characterization of lipids, including lipid A, using tandem mass spectrometry (MS2) can be performed in a simultaneous fashion within a single analysis. Interpretation of tandem mass spectra is, however, a manual process which typically requires expert understanding of the fragmentation pathways. To keep up with the rapid data acquisition rates enabled by modern MS2 technologies, significant advances have been made in the development of computational tools for data deconvolution and MS2-based compound identifications.17−22 Automated lipid identification capitalizes on the predictable nature of fragmentations for similar molecules within each lipid subclass. Two common identification strategies used in lipidomics include (i) spectra matching against a database derived from experimental data and/or in silico computation,18,23−26 and (ii) decision tree based on fragmentation rules.19 However, existing lipid identification pipelines have limited utility for lipid A analyses, in part due to the lack of spectral databases. Moreover, analysis of lipid A is technically challenging due to its vast diversity and structural complexity.

Two lipid A-specific workflows for automation of lipid A structure identification, hierarchical tandem mass spectrometry (HiTMS)27 and UVliPiD,28 were designed for MSn data generated using linear ion-trap MS, with the latter employing ultraviolet photo- dissociation collision-induced dissociation (UVPDCID)29, a novel hybrid dissociation technique. These methods are extremely powerful for detailed structural assignments of lipid A, including localization of modifications. However, access to these technologies, particularly UVPD, is limited. Moreover, the algorithm for HiTMS is built on a bacterial species-specific signature ion database and will require further expansion to broaden its coverage.

To enable global profiling of lipid A from diverse biological origins, a structure identification workflow should be scalable, robust, and easily adopted by nonspecialists for spectral interpretations. Hence, LipidA-IDER was developed with a fragmentation-rule-based approach to assign lipid A identities for high-resolution MS2 data. Using LipidA-IDER, we characterized 218 potential lipid A species (188 distinct structures) across the model organism, E. coli, and the Gram-negative members of ESKAPE pathogens: Enterobacter species, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii.(28) This is the first systematic and comprehensive atlas detailing the lipid A landscape of ESKAPE-a group of nosocomial pathogens classified by the World Health Organization as priority pathogens due to their rapid emergence of AMR and associated mortality risks.30 In addition, multiple structural signatures of PMX-resistant A. baumannii were defined, corroborating observations from past genetics and biochemical studies.31−33 With LipidA-IDER, we further generated an experimentally derived reference spectral library that can be integrated with other common lipidomic pipelines, including MS-DIAL26 and MetaboKit,25 for spectral similarity-based identification and semiquantitative analyses of these characterized lipid A, which will facilitate future structure-function studies.

Experimental Section

Analytical Reagents and Lipid A Standards

Methanol (LC−MS grade) and chloroform (spectroscopy grade) were from Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Tedia, respectively. Ammonium hydroxide solution and mono- and diphosphorylated lipid A from E. coli F583 Rd mutant were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Bacterial Strains and Culture

Bacterial species and strains used in this study and their sources are summarized in the Supporting Information Methods. Cultures were grown overnight in lysogeny broth (LB) (Difco) at 37 °C with shaking at 150 rpm, and subsequently inoculated at a starting optical density (600 nm) of 0.05 in LB. Stationary phase bacteria were collected by centrifugation at 3000g at 4 °C for 10 min, followed by washing with phosphate-buffered saline. Samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Extraction of Lipopolysaccharides (LPS)

LPS were extracted by a modified Bligh and Dyer method.34 Briefly, chloroform/methanol (1/2, volume/volume (v/v)) was added to the bacterial pellet, followed by incubation for 4 hours at 4 °C, with shaking. Water and chloroform were added, and the samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 4 °C, 2000g. The upper aqueous layer was collected, re-extracted twice with chloroform, and dried.

Acid Hydrolysis of LPS and Extraction of Lipid A

A modified method described by Caroff et al was used.35 The dried aqueous phase fraction from LPS extraction was resuspended in 12.5 mM sodium acetate with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (pH 4.5) (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were sonicated for 10 min, followed by incubation at 100 °C for 40 min. After allowing the samples to cool, chloroform/methanol (1:1, v/v) was added, followed by centrifugation at 2000g for 15 min at 4 °C. The organic phase was collected and re-extracted with artificial upper phase (chloroform/methanol/water (2/2/1.8, v/v/v)). The organic fraction was dried under a stream of nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry (LC−MS) Analysis

Mass spectrometry (MS) and tandem MS (MS2) analyses of lipid A were performed using a SCIEX TripleTOF 6600 quadrupole time-of-flight (qToF) mass spectrometer in the negative electrospray ionization (ESI) mode. Lipid A were separated by liquid chromatography (Agilent 1290) using an Inertsil SIL column (3 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm, GL Sciences, Japan). The mobile phase A consisted of chloroform/methanol/ammonium hydroxide (80/19.5/0.5, v/v/v) and B consisted of chloroform/methanol/water/ammonium hydroxide (40/50/9.5/0.5, v/v/v/v). The gradient with a flow rate of 0.25 mL/min started with 5% mobile phase B held for 2 min. The composition of mobile phase B was then increased to 70% over 6 min and to 99% over 5 min. Mobile phase B was then held at 99% for 1 min, followed by re-equilibration. Automated MS2 analyses were performed in the information dependent acquisition (IDA) mode with the top 20 ions selected per scan for fragmentation and without exclusion time. MS2 was focused on [M − H]− ions to systematically characterize lipid A, considering most lipid A can form singly charged ions. Collision energy (CE) from 40 to 120 V, with steps of 10 V, was applied to generate the fragmentation profiles of lipid A for all samples (purified E. coli lipid A fractions and biological extracts). For all biological extracts, CE 40, 60, 90, and 110 V were used in the second analytical batch, and CE 90 and 110 V were used in the third analytical batch. Biological replicates were analyzed in the IDA mode (CE 110 V) and targeted product ion scans (with various CE) were performed for low abundant lipid A.

To determine the reproducibility of LipidA-IDER, E. coli F583 Rd mutant monophosphorylated fraction was analyzed in four independent analytical batches, each with at least four technical replicates. For relative quantitation of lipid A, samples (two biological replicates, with three technical triplicates) were analyzed with two LC−MS technical replicates. Quality control (QC) samples comprising pooled samples were included.

LipidA-IDER Workflow and Availability

LipidA-IDER is freely available at https://github.com/Systems-Biology-Of-Lipid-Metabolism-Lab/LipidA-IDER. The workflow is coded using Python, and the fragmentation patterns were derived from data generated in this study and detailed literature review (Supporting Information Tables S2–S3). Raw .wiff files were converted to .ms2 format with ProteoWizard MSConvert,36 with TPP unchecked, and the CWT filters for peak picking. .ms2 files are directly imported into LipidA-IDER and analyzed using the default settings (Supporting Information Table S4). Additional details are described in the Supporting Information Methods.

Validation Analysis

The major lipid A from the reference bacterial species, E. coli and P. aeruginosa, were manually annotated and selected for subsequent analysis. These comprised mono- and diphosphorylated lipid A with four to six acyl chains for E. coli and mono- and diphosphorylated penta-acylated lipid A for P. aeruginosa to account for structural variation. To evaluate the effect of CE on fragmentation profiles, data acquired using CE ranging from 40 to 110 V were used. Acquisition was performed without exclusion time, and therefore for each ion, multiple MS2 can be acquired. The highest signal for each extracted ion is first evaluated to check for correctness of identification generated by LipidA-IDER, followed by randomizing the ion intensity with bootstrapping (n = 100) to generate a set of spectra with varying number of diagnostic peaks to test the accuracy of LipidA-IDER. The accuracy of the identity assignment was further assessed using all acquired MS2 data points which vary in quality, and the data are analyzed to determine an optimal score cutoff for subsequent analysis. A total of 27 data sets were used.

Analysis with MS-DIAL

The .wiff files were imported directly into MS-DIAL v4.80.26 For benchmarking of LipidA-IDER performance, the LipidBlast-neg library23 and spectral library generated using LipidA-IDER were used. For relative quantitation, lipid A were identified with LipidA-IDER-generated library, and LOWESS correction was applied (refer to Supporting Information Table S5 for MS-DIAL settings used).

Evaluation of LipidA-IDER-Annotated Lipid A from E. coli and ESKAPE Pathogens and Spectral Library Generation

MS2 data were analyzed independently for each strain with LipidA-IDER. In total, 298 data sets were analyzed. Identified features with output scores above the defined score threshold (35) with at least 3 occurrences across all acquisitions per organism were evaluated. When score distance between two hits is less than 15% difference, the data will be evaluated for the presence of coeluting isomers. For identified features with only one occurrence, it will only be accepted if it is acquired using the MS2 mode and manually reviewed. For identified features with scores above the threshold and lipid A with conflicting identified features, multiple spectra from different acquisitions were manually inspected to confirm the identification. The annotated features for each bacterial species were selected for generation of a spectral library in the .msp format (Supporting Information 2).

Hierarchical Clustering and Heatmap Visualization of Lipid A Features of E. coli and Gram-Negative ESKAPE Members

Identified lipid A in each strain were grouped by their structural characteristics. For each characteristic, total count of all lipid A identified that matched the characteristic was normalized to the total number of lipid A identified within each bacterial strain, with exception for the carbon number characteristic, which was normalized to the total number of FA chains present in all lipid A annotated. Hierarchical clustering with Euclidean distance and complete linkage was performed, and the data were visualized with a heatmap (pheatmap, R).

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the reproducibility of LipidA-IDER, coefficient of variance (CV) of the highest score for each technical replicate from four analytical batches was calculated.

To compare lipid A species/subclass levels between PMX-sensitive and PMX-resistant A. baumannii strains, two biological replicates were analyzed. Data presented are a representative set, within which three cultures were sampled per strain, and each lipid A extract was analyzed twice. The data were computed as follows:

Fold change of characteristic ratios between two strains were computed, and statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test. Data were considered significant if p-value is <0.05 and absolute fold change >1.5, and reproduced in the two independent data sets. Bubble plots were constructed with matplotlib in Python.

Results

Lipid A Structure, Fragmentation, and Proposed Nomenclature

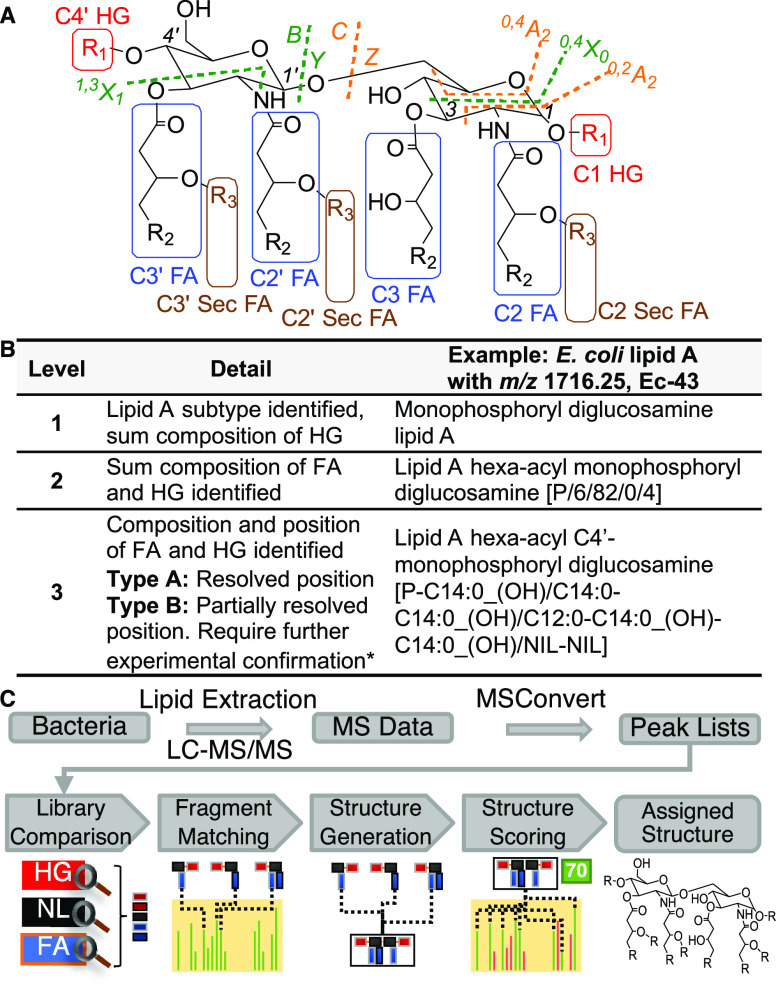

Numerous studies demonstrated the feasibility to determine the complex structure of lipid A using negative ESI-MS2 with collision-induced dissociation (CID)37−41 (for additional references, refer to Supporting information Tables S1 and S2). Figure 1A shows the general annotation of lipid A structure for simple and intuitive assignment of MS2 fragment ions generated in this work. The glycan-linked backbone fragment nomenclature was adopted from Domon and Costello.42

Figure 1.

General structure, fragmentation and nomenclature of lipid A, and workflow of LipidA-IDER. (A) Structure of lipid A. HG = headgroup, FA = fatty acyl, R1 = headgroup, R2 = alkyl chain, and R3 = H or acyl chain. Primary FAs (blue box) are linked to the diglucosamine moiety with an amide bond at C2′ and C2 or an ester bond at C3′ and C3. Secondary FAs (brown box) are linked to primary FAs through ester bonds. The C1 and C4′ positions can be modified with different HGs, i.e., different degrees of phosphorylation with addition of PEtN, hexosamines, and Ara4N (not exhaustive) (red box). Using negative ESI-MS2 with CID, fragmentation can occur at various positions on the diglucosamine backbone (orange and green dashed lines), HG, and FA (as a ketene or acid molecule). (B) Nomenclature of lipid A in this study. Lipid A is annotated with a three-level classification based on the degree of structural resolution. Positions that are not filled are marked with “NIL”. In cases where isomers are present confounding the annotation, subcategorization to type A and B will be applied. (C) Schematic of LipidA-IDER, an automated fragmentation-rule-based workflow.

A three-level classification, summarized in Figure 1B, is used to standardize the nomenclature of lipid A identified with MS2, in line with recommendations by the lipidomics community.43,44 Specifically, level 1 entails only the type of headgroup. Level 2 represents the sum composition of the FA and headgroup modifications, and level 3 identification provides higher structural resolution where the position of the fatty acids on the diglucosamine backbone and the chain compositions are defined.

LipidA-IDER Development and Workflow

We designed LipidA-IDER, an automated spectral annotation tool for comprehensive MS2-based identification of lipid A, in Python. LipidA-IDER can be utilized with a graphical user interface (GUI) or command lines, with user-editable options (available at: https://github.com/Systems-Biology-Of-Lipid-Metabolism-Lab/LipidA-IDER). The architecture of LipidA-IDER consists of two customizable in silico libraries and a comprehensive set of fragmentation rules to model the fragmentation of diverse lipid A structures. The building block library (BBLib) is a simple database of headgroups and FA-related ions, theoretically derived from their molecular formulae (Supporting Information Table S6). The theoretical backbone fragment library (TFLib) is a group of known fragment types associated with fragmentation of the diglucosamine backbone (Supporting Information Figure S1 and Table S7).

An extensive set of fragmentation rules for singly deprotonated ([M − H]−) lipid A was derived from a detailed literature review (Supporting Information Tables S1 and S2) and experimentally generated MS2 data from purified mono- and diphosphorylated lipid A fractions from E. coli F583 Rd mutant and biological extracts from E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Supporting Information Figures S2–S6). These two bacterial species served as a reference to overcome the limitations of the lack of lipid A standards considering their structures and biochemistry are well-established.5,45 Furthermore, the structural and biochemical differences between the lipid A from E. coli(37,46) and P. aeruginosa(47,48) provided a source of chemical diversity (Supporting information Figure S7) and enabled the derivation of organism-independent fragmentation rules.

The workflow of LipidA-IDER is summarized in Figure 1C. LipidA-IDER first scans each MS2 peak list for (i) neutral loss of FAs and headgroups and, (ii) headgroup anions by matching against BBLib (Supporting Information Table S6). Based on this output, a set of backbone fragments using TFLib is generated (Supporting Information Figure S1 and Table S7), which the MS2 peak list is matched against. Proposed lipid A structures are then constructed using the information inferred from the matched backbone fragments. Subsequently, for each structure, a set of theoretical fragments is generated with the encoded fragmentation rules. As a final step, the MS2 peak list is matched against each theoretical fragment set. A score is computed based on the sum intensities of matched fragments19,24 and weighed according to the total input signal and the nature of the fragment ions. LipidA-IDER also calculates the score differences between the top proposed structures as a measure of the confidence of identity matching18 and as a proxy to evaluate the presence of coeluting isomers.

Accurate identification is crucial for downstream pathway analyses involving specific enzymes5 (Supporting Information Figure S7). To improve the stringency of identification and to reduce artifacts, LipidA-IDER has additional filtering features as follows: (i) peak intensity cutoff to remove low abundant signals, (ii) minimal number of diagnostic peaks detected, and (iii) biochemical filter to remove structures that do not fit any known substrate constraints of the hydrocarbon rulers, LpxA and LpxD.49,50 The final output also includes matches to user-defined enzymes linked to the structures to facilitate a biochemistry-driven data review.

Overall, our stepwise, data-driven approach enabled fast and accurate lipid A identification, which took about 40 min to extract and analyze a typical DDA data file (with ∼2717 MS2-spectra) on a workstation (16GB RAM, 8 core processor) with multiprocessing.

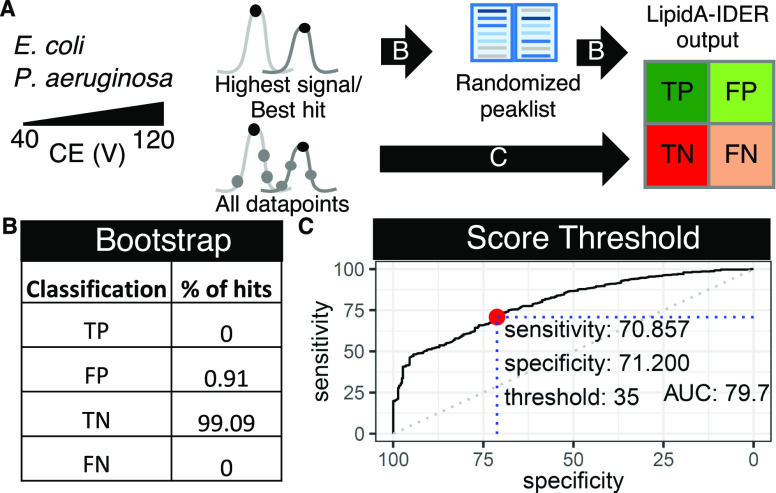

Systematic Evaluation and Validation of LipidA-IDER

Tandem-MS-based identification depends on multiple factors that influence spectral quality, including collision energy (CE) and signal abundance. To evaluate the effect of spectral quality on the accuracy of identification using LipidA-IDER, we analyzed a set of major lipid A species from E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Figure 2A). LipidA-IDER accurately identified these characterized lipid A over a range of CE when the most abundant signal for each lipid A was evaluated. The score output in general depends on the combination of spectral quality and the number of matched diagnostic ions (Supporting Information Figures S8A,B and S9A,B). To assess the effects of signal intensity of fragment ions and availability of diagnostic peaks on identification, the best hit for each major lipid A was selected for randomization of fragment intensity with bootstrapping (n = 100 for 10 features). Since LipidA-IDER requires data with sufficient diagnostics peaks and intensity for identification, we anticipated that no annotations will be generated when such criterion fail. Indeed, analysis of the signal-randomized data using LipidA-IDER resulted in a 0.91% false positive rate, with the majority of the data (99%) having no annotation (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Validation of LipidA-IDER for confident lipid A identification. (A) Schematics of data used for validation. MS2 data (multiple CE) of major lipid A from E. coliandP. aeruginosa were analyzed. The intensity of fragment ions for each of these lipids (arrow B) was randomized to test the performance of LipidA-IDER. All data points acquired in this data set were further analyzed to evaluate the performance of identification for data with mixed quality (arrow C). (B) False positive rate of identification using data with randomized signals (bootstrap n=100). (C) Receiver operator curve (ROC) for determination of the score threshold (in red) for accurate identification of mono- and diphosphorylated lipid A in biological extracts.

To further evaluate the performance of LipidA-IDER and to determine the score threshold for accurate identification of experimental data with mixed quality, all acquired MS2 features for ions with m/z corresponding to these characterized lipid A were analyzed. The output was assigned to a confusion matrix (Supporting Information Figure S10), and Figure 3C shows the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve derived using the final scores to establish a cutoff to balance between sensitivity and specificity of identification. Overall, at a score threshold of 35 (red dot and blue dotted lines), the sensitivity and specificity of LipidA-IDER are 70.9 and 71.2%, respectively (Figure 3C), and this cutoff was chosen for subsequent analysis. It was in general observed that misassignments are more common for low abundant species and peaks with coeluting isomers. Hence, a user-defined filter for peak intensity was incorporated. In addition, the score distance between the top hits can be used as a proxy for the existence of coeluting isomers for users to further evaluate the data.

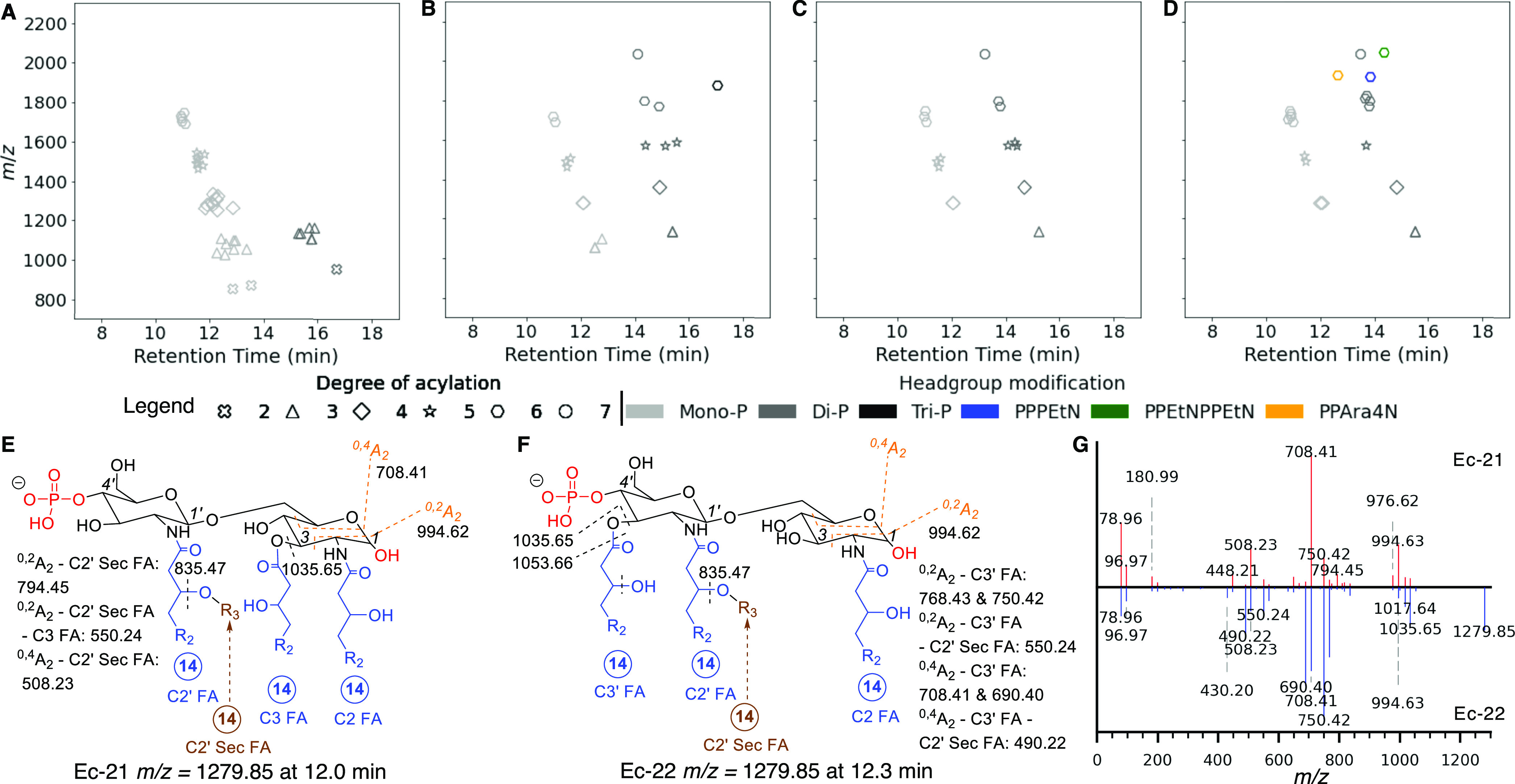

Figure 3.

Benchmarking performance of LipidA-IDER for comprehensive identification of E. coli lipid A. (A–D) Feature maps of lipid A in E. coli F583 Rd mutant monophosphorylated fraction, E. coli F583 Rd mutant diphosphorylated fraction, E. coli strain W3110, and E. coli strain EC958, respectively. Each point represents a unique lipid A structure, where the position represents the retention time and m/z; the color and shape represent the headgroup and degree of acylation, respectively. (E, F) Characterization of monophosphorylated tetra-acylated lipid A with C3′ deacylation (Ec-21, m/z = 1279.85 @ 12.0 min) and its isomer with C3 deacylation (Ec-22, m/z = 1279.85 @ 12.3 min). (G) MS2 spectra of Ec-21 (top) and Ec-22 (bottom). R2 = alkyl chain and R3 = FA chain. Circled number indicates the carbon number of the FA.

Next, to determine the effect of analytical variations, MS2 data from four independent LC−MS batches were analyzed. The score variations for the identification of five lipid A from E. coli F583 Rd mutant monophosphorylated fraction were low (<10%), confirming the reproducibility of the workflow (Table 1).

Table 1. Reproducibility of LipidA-IDER Generated Annotation of Lipid A across Four Technical Batches.

| Lipid A | m/z [M – H]− | CV (%) of score |

|---|---|---|

| P/3/40/0/2, Ec-6 | 1053.66 | 3.6 |

| P/4/54/0/3, Ec-22 | 1279.85 | 2.5 |

| P/5/68/0/3, Ec-31 | 1490.05 | 1.7 |

| P/5/68/0/4, Ec-32 | 1506.05 | 5.1 |

| P/6/82/0/4, Ec-43 | 1716.25 | 2.8 |

Coverage of Lipid A in the Model Organism, E. coli

To benchmark LipidA-IDER performance, we characterized lipid A in the model organism, E. coli. Feature maps of lipid A identified in E. coli F583 Rd mutant (mono- and diphosphorylated fractions), E. coli strain W3110, and E. coli pathogenic strain EC958 are presented in Figure 3A–D, respectively. In total, 55 potential lipid A species (assigned ID numbers Ec-1 to Ec-55 in Supporting Information Table S9) were resolved at level 3 identification, in contrast to 44 lipid A with a similar or higher level of structural resolution reported previously.28,37,40,46 Besides mono-, di-, and triphosphorylated lipid A, PEtN (Ec-52, Ec-55) and Ara4N (Ec-53) modifications were detected in E. coli strain EC958, a globally disseminated virulent and multidrug-resistant E. coli O 25b:H4-ST131 clone51 (Figure 3D).

Variations from the classical hydrophobic components were observed in minor lipid A forms, including (i) myristoylation at the C2 secondary position (Ec-40)37 and (ii) incorporation of an unsaturated C16:1 secondary FA chain at the C2′ position (Ec-26, Ec-35).40 LipidA-IDER also differentiated isomers with different acylation positions (Figure 3E,F) based on their distinct fragmentation patterns (Figure 3G). For instance, the remodeling lipid A forms, tetra-acylated lipid A deacylated at the C3′ position (Ec-21) and C3 position (Ec-22) were identified, and the structures were corroborated by Sandor and co-workers.37 In addition, four pairs of potential coeluting isomers were also found (Supporting Information Tables S8 and S9).

Using the data set generated, we next compared the coverage of LipidA-IDER with MS-DIAL26 using LipidBlast,23 focusing on diphosphorylated, hexa-acylated lipid A, the only forms in LipidBlast. Although the number of hits was comparable between LipidA-IDER and MS-DIAL/LipidBlast (Table 2), the FA composition of the top hits from the latter was misassigned (Supporting Information Figure S11A). Notably, the reference spectra from LipidBlast lacked diglucosamine backbone fragments (Supporting Information Figure S11B,C), which are critical for accurate assignment of lipid A.33,52 To improve the spectral similarity-based identification with MS-DIAL, a library was generated from LipidA-IDER-annotated experimental spectra (Supporting Information Figure S11D and Supporting Information 2). Overall, integration of a LipidA-IDER-annotated library resulted in an increase in the numbers, types, and accuracy of lipid A identified with MS-DIAL (Table 2).

Table 2. Number of Diphosphorylated (diP) Lipid A Species in E. coli Samples Identified Using LipidA-IDER and MS-DIAL.

| analysis pipeline | E. coli/lipid A type | F583 Rd mutant diP | W3110 | EC958 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LipidA-IDER | diP | 8 | 2 | 1 |

| hexa-acyl diP | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| MS-DIAL/LipidBlasta | hexa-acyl diP | 3b | 1b | 0 |

| MS-DIAL/LipidA-IDER library | diP | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| hexa-acyl diP | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Score cutoff of 75.

Identity of these features was misassigned.

Generation of Lipid A Atlas for Gram-Negative Members of ESKAPE Pathogens Using LipidA-IDER Revealed Species- and Strain-Dependent Structural Variants

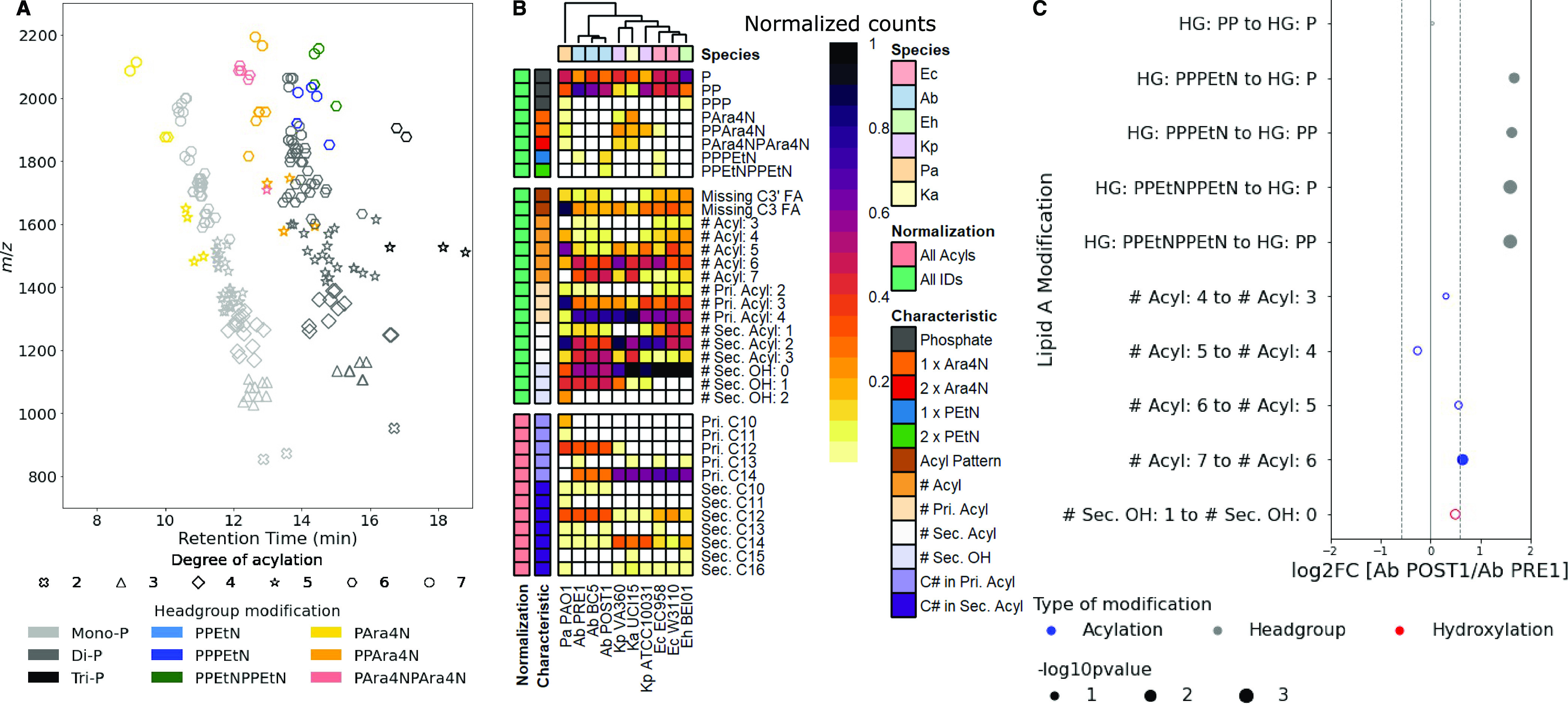

To demonstrate the general utility of LipidA-IDER for lipid A identification across diverse bacterial species, we analyzed lipid A of Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens—Enterobacter hormaechei (Enterobacter cloacae complex), K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, and P. aeruginosa. Klebsiella aerogenes, a nosocomial and pathogenic species, was included to determine species variations within Enterobacteriaceae. LipidA-IDER generated the most comprehensive high-resolution biochemical atlas of lipid A characterized in these medically relevant pathogens. Figure 4A shows the chemical space of lipid A from all six bacterial species. In total, 218 potential lipid A species with 188 distinct structures were annotated in this single study (Supporting Information Tables S8 and S9),with several structures corroborated by earlier studies.28,29,33,37,40,46−48,53−62

Figure 4.

Lipid A repertoire of E. coli and Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens. (A) Combined feature map for lipid A identified at level 3 for E. coli and Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens: E. coli (Ec) W3110 and EC958; E. hormaechei BEI01; K. pneumoniae ATCC10031 and VA360; K. aerogenes UCI15; A. baumannii BC5, PRE1, and POST1; and P. aeruginosa PAO1. Level 3 annotations of these lipid A can be found in Supporting Information Table S9. (B) Heatmap representing the structural characteristics of the identified lipid A in E. coli and Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens. (C) Bubble plot representing the relative changes in lipid A subtypes in A. baumannii POST1 compared to A. baumannii PRE1. The position and area of the bubbles represent the log2 fold change (log2FC) and p-values, respectively. Only characteristics with significant and reproducible changes are labeled.

Clear bacterial species and strain differences were observed when hierarchical clustering was performed on lipid A characteristics profiles (Figure 4B). The Enterobacteriaceae (E. coli, Klebsiella species, and E. hormaechei) shared greater similarity and separated from A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa. This distinction stemmed primarily from the frequency of hexa-acylated forms of lipid A, with C14:0 FA as the major hydrophobic component. A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa, on the other hand, formed distinct clusters, where the former was enriched in hepta-acylated lipid A with C14:0 and C12:0 as the major FA components, while the latter was enriched in penta-acylated lipid A with C12:0 and C10:0 as the major FA components.

Remarkable differences were also observed between different strains of the same bacterial species. For both E. coli and K. pneumoniae, a laboratory strain and a multidrug-resistant (MDR) human isolate were analyzed. Strikingly, in both organisms, modifications of the headgroups with PEtN (Ec-52 and -55) and Ara4N (Ec-53 and Kp-6, -8, -13, -14, -17, -18) were found in the MDR strains, E. coli EC958 and K. pneumoniae VA360, respectively. Yet, these strains do not carry any known resistance genes or plasmids for PMX.51,63 Similarly, the MDR K. aerogenes strain, UCI15, also possessed a significant number of Ara4N-modified lipid A (Ka-2, -3, -7, -9 -10, -14, -16 to -21), despite its colistin sensitivity (data not shown). Our data suggested that multiple lipid A structural features are potentially linked to PMX resistance. Indeed, it was previously shown that the attachment of Ara4N to lipid A and the subsequent resistance to PMX depend on the presence of the secondary linked myristoylation.64

To unravel the fine structural characteristics of PMX-resistant bacteria, we systematically compared the relative levels of lipid A of a pair of A. baumannii PMX-sensitive (Ab PRE1) and PMX-resistant (Ab POST1) clinical isolates derived from the same patient.65 As expected, PEtN-modified lipid A was detected in Ab POST1 (Figure 4B), which harbored mutations in pmrB,65 a two-component sensor kinase signal peptide involved in regulation of PEtN transferase.66 In addition, when comparing the relative levels of lipid A by structural characteristics, Ab POST1 showed an enriched proportion of lipid A with higher degree of acylation (Figure 4C). Collectively, our data demonstrated that the PMX-sensitive and PMX-resistant A. baumannii isolates were distinguished by a combination of the types and relative levels of distinct lipid A species, besides the PEtN-modification arising from known genetic mutations.

Discussion

We present LipidA-IDER, an automated identification tool for lipid A, a class of bacterial lipids which are functionally important for virulence and AMR. LipidA-IDER’s extensively curated fragmentation rules and building block libraries can be expanded by users to other lipid A types. In addition, several modifiable settings allow for extensive filtering at different levels of processing to remove redundant lipid identifications and spurious features. Finally, with the acquisition time of a typical LC–MS-DDA analysis of less than 25 min and processing of over 2000 extracted MS2 spectra within 40 min, LipidA-IDER offers a rapid approach for structural annotation of lipid A from multiple data sets.

LipidA-IDER enables the system-level scale analysis of lipid A in an organism-independent manner, as demonstrated by its application to probe the lipid A repertoire of E. coli and Gram-negative members of ESKAPE pathogens. While there is a lack of authenticated standards for lipid A, we harnessed the well-established structures of two bacterial species, E. coli and P. aeruginosa, to derive the fragmentation rules, which are supported by extensive literature review (Supporting Information Tables S1 and S2). Overall, this is by far the most comprehensive biochemical resource with detailed structural annotation of potential lipid A in these priority pathogens, resolved at the levels of their FA and headgroup composition and positions.

Nonetheless, several limitations of LipidA-IDER which influenced its accuracy exist. First, the lack of resolution of cofragmentation arising from coeluting isobaric lipid A generated mixed spectra which can lead to misidentification. Indeed, we tested LipidA-IDER using infusion-based data generated with both qToF and triple quadrupole MS, and the lack of isomer separation reduced the number of level 3 hits (data not shown). In addition, several lipid A structures can have a high degree of similarity in their fragment profiles, resulting in both false positive and false negative results. For instance, bis-phosphorylated and pyrophosphorylated lipid A can be differentiated by the presence of pyrophosphorylation in the cross-ring fragments in the latter form. However, these fragments tend to be low abundant as there is a tendency to lose one phosphate group, leading to misassignment or lack of assignment. Improved resolution of lipid A in complex mixtures can be achieved with chromatographic separation of isomers before MS2, multistage MS analysis27 as well as further analysis using doubly charged adducts or positive ionization.38 Computational approaches for data deconvolution for lipid A need to be developed, which is currently possible for structurally simpler phospholipids enabled by LipiDex.18 In the current version, LipidA-IDER will generate a flag for lipid A with headgroups which are prone to such misassignment to indicate that the identification is level 3 type B (Figure 1) to prompt users to conduct further verification. In addition, the score distance between top hits can be used as an indicator to screen for existence of coeluting isomers.

Another possible cause of false discovery is the availability of fragmentation rules for different types of lipid A, which can result in misassigned identification, evident from applying the LipidBlast library to our data sets. For the current work, the rule coverage included the [M − H]− ions for mono-, di-, and triphosphorylated, Ara4N- and PEtN- modified lipid A with diglucosamine backbone and will require further expansion of the fragmentation rules for other lipid A types6,7 as well as other adduct types. The current work had focused on singly charged [M − H]− adducts, which are most commonly reported by different studies33,37−39,41,67,68 and these studies served as a source of reference for the fragmentation rules as well as supporting evidence of the annotated structures. Nonetheless, we observed that for lipid A with multiple modifications, especially on both sugars, the propensity to form doubly charged ions is higher and warrants further work. The coverage of lipid A species identified also further depends on their natural abundance, as the spectral quality of low abundant lipids is insufficient for detailed annotation. Moreover, lipid A content is influenced by environmental conditions and sites of infection,69,70 and the span of lipid A will change when bacteria are exposed to different stimuli. Indeed, analytical methods, including extraction and LC–MS analysis, and biological variations are potential reasons for differences in coverage of lipid A reported. We also do not rule out that some of the lipid A identified can arise from in-source fragmentation during LC–MS analysis or break down during extraction due to the heating and hydrolysis steps.71 Despite these pitfalls, LipidA-IDER enabled a comprehensive and simple approach for lipid A analysis with data generated using common instrumentation. In addition, the output of the annotated lipid A can be integrated with software, including MS-DIAL and MetaboKit, for qualitative analysis and relative quantitation, facilitating studies of lipid A functions in bacterial physiology, virulence, and AMR.

With LipidA-IDER, we revealed both the similarities and differences in the lipid A landscape of E. coli and Gram-negative members of ESKAPE pathogens. Our data on the complex lipid A repertoire reinforce the known biochemistry of lipid A, including the strict substrate specificity of the hydrocarbon rulers LpxA and LpxD49,50 (Supporting Information Figure S7), which limit the range of FA incorporated into lipid A. In addition, we uncovered several lipid A features that suggested the presence of previously uncharacterized enzymatic activities for lipid A biosynthesis and remodeling. These included (a) myristoylation at sites of palmitoylation and (b) presence of C3-deacylated lipid A in A. baumannii and the Enterobacteriaceae species, suggesting a PagL-like enzyme activity remained to be discovered in these bacteria.72 The panel of bacterial species and strains analyzed in this study is part of a reference panel we defined, with genome sequences available.63,73,74 The lipid A atlas generated can thus be integrated with genomics, genetics, and biochemical studies to unravel novel enzymes involved in lipid A metabolism.

Indeed, the detection and characterization of diverse lipid A in this work highlight the natural diversity and complexity of lipid A in biological systems. This is exemplified by our findings on the incorporation of Ara4N and PEtN in bacterial species and strains which are sensitive to PMX. No doubt numerous studies had proven the link between the addition of polar groups to lipid A with PMX resistance at the genetic and biochemical levels.75 We do not rule out the involvement of transcriptional or post-translational events linked to the presence of modified lipid A in the PMX-sensitive strains. In addition, we demonstrated using a pair of PMX-sensitive and PMX-resistant A. baumannii isolates that the latter displayed multiple modifications in lipid A. Specifically, the major modifications of lipid A related to PMX resistance, including addition of PEtN,33 increased acylation,59 and hydroxylation of secondary FA,31 were identified in a single experiment using LipidA-IDER.

In summary, we propose LipidA-IDER as a useful tool for comprehensive lipid A analysis across diverse bacterial species. Moreover, circulating strains have evolved and displayed different lipid A on their outer membranes to adapt to varying environments and we demonstrated the application of LipidA-IDER for comparative lipidomics of MDR and PMX-resistant bacterial strains. A tool that is easily accessible is also of important consideration. Hence, LipidA-IDER was established to interpret MS2 data generated by common ESI instruments with CID and its output can be integrated with other lipidomics software for downstream data processing. We hope that LipidA-IDER and the lipid A atlas generated will be a useful resource for future studies to uncover novel insights in lipid A metabolism and functions in diverse Gram-negative bacteria.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Nanyang Assistant Professorship from Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University (NTU), and the Ministry of Education (MOE) Tier 2 grant (MOE2017-T2-1-042), awarded to X.L.G. The authors thank Asst. Prof. Marie Loh (NTU) for helpful discussions on statistical validation; Assoc. Prof. Hyung Won Choi and Dr. Guoshou Teo (National University of Singapore, NUS) for their support on MetaboKit; and Assoc. Prof. Shu-Sin Chng (NUS), Asst. Prof. Chris Sham (NUS), and Prof. Howard Riezman (University of Geneva) for their feedback on the manuscript. The following were obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: K. pneumoniae, strain VA360, NR-48977; A. baumannii, strain BC5, NR-17783; E. hormaechei, strain BEI01, NR-50391; and K. aerogenes, strain UCI15, NR-48555.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.1c03566.

Supporting Information 1: Supplementary methods; general structure of the backbone generated from fragmentation of the diglucosamine moiety used to build the TFLib (Figure S1); characterization of mono-, di-, and triphosphorylated lipid A in E. coli F583 Rd mutant, Ara4N-modified lipid A found in P. aeruginosa PAO1, and PEtN-modified lipid A in E. coli EC958 (Figures S2–S6); lipid A biosynthesis (Raetz pathway) and modifications found in Gram-negative bacteria (Figure S7); identification of major E. coli and P. aeruginosa mono- and diphosphorylated lipid A using different collision energy (Figures S8 and S9); classification of lipid A identification output (with a score cutoff of 35) for major mono- and diphosphorylated lipid A from E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Figure S10); lipid A identification using MS-DIAL (Figure S11); characterization of the structure of lipid A with mass spectrometry in the literature (Table S1); fragment types observed in negative mode CID for various types of lipid A (Table S2); terminology used in LipidA-IDER fragmentation rules (Table S3); settings used in LipidA-IDER and MS-DIAL (Tables S4 and S5); default FA and headgroup BBLib (Table S6); components of the TFLib (Table S7); total number of annotated lipid A (Table S8); and potential lipid A in various bacterial species annotated by LipidA-IDER (Table S9) (PDF)

Supporting Information 2: Experimentally derived lipid A MS2 spectral library for all organisms analyzed in this study, generated by LipidA-IDER, in the .msp format (ZIP)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, optimization of extraction and LC–MS analysis, data analysis and interpretations, writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript, funding acquisition: X.L.G.; coding and validation, data analysis and interpretations, and writing and reviewing of the manuscript: J.Y.-X.L. and B.T.K.L. Microbiology, lipid extraction and LC–MS, and literature and manuscript review: M.L. Microbiology and initial manuscript review: S.C.M.C. Pilot coding, preliminary analysis, and initial literature and manuscript review: J.M.C.K. Clinical microbiology of A. baumannii isolates and manuscript review: L.H., T.P.L., and T.H.K. All authors have given approval to the final version of the article.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- May K. L.; Grabowicz M. The bacterial outer membrane is an evolving antibiotic barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018, 115, 8852–8854. 10.1073/pnas.1812779115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medearis D. N.; Camitta B. M.; Heath E. C. Cell wall composition and virulence in Escherichia coli. J. Exp. Med. 1968, 128, 399–414. 10.1084/jem.128.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raetz C. R. H.; Whitfield C. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002, 71, 635–700. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham B. D.; Trent M. S. Fortifying the barrier: The impact of lipid A remodelling on bacterial pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 467–481. 10.1038/nrmicro3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raetz C. R. H.; Reynolds C. M.; Trent M. S.; Bishop R. E. Lipid A Modification Systems in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007, 76, 295–329. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que-Gewirth N. L.; Lin S.; Cotter R. J.; Raetz C. R. An outer membrane enzyme that generates the 2-amino-2-deoxy-gluconate moiety of Rhizobium leguminosarum lipid A. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 12109–12119. 10.1074/jbc.M300378200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamlynska K.; Komaniecka I.; Zebracki K.; Mazur A.; Sroka-Bartnicka A.; Choma A. Studies on lipid A isolated from Phyllobacterium trifolii PETP02(T) lipopolysaccharide. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2017, 110, 1413–1433. 10.1007/s10482-017-0872-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham B. D.; Carroll S. M.; Giles D. K.; Georgiou G.; Whiteley M.; Trent M. S. Modulating the innate immune response by combinatorial engineering of endotoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 1464–1469. 10.1073/pnas.1218080110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park B. S.; Song D. H.; Kim H. M.; Choi B. S.; Lee H.; Lee J. O. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex. Nature 2009, 458, 1191–1195. 10.1038/nature07830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X.; Sankaranarayanan K.; Khosla C. Biosynthesis and structure–activity relationships of the lipid A family of glycolipids. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 40, 127–137. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop R. E. How lipopolysaccharide strikes a balance. Nature 2020, 584, 348–349. 10.1038/d41586-020-02256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi H. R.; Pelak B. A.; Gerckens L. S.; Silver L. L.; Kahan F. M.; Chen M. H.; Patchett A. A.; Galloway S. M.; Hyland S. A.; Anderson M. S.; Raetz C. R. H. Antibacterial agents that inhibit lipid A biosynthesis. Science 1996, 274, 980–982. 10.1126/science.274.5289.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff T. J. O.; Raetz C. R. H.; Jackman J. E. Antibacterial and anti-inflammatory agents that target endotoxin. Trends Microbiol. 1998, 6, 154–159. 10.1016/S0966-842X(98)01230-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod M. K. L.; McKee A. S.; David A.; Wang J.; Mason R.; Kappler J. W.; Marrack P. Vaccine adjuvants aluminum and monophosphoryl lipid A provide distinct signals to generate protective cytotoxic memory CD8 T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 7914–7919. 10.1073/pnas.1104588108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata-Haro V. V.; Cekic C.; Martin M.; Chilton P. M.; Casella C. R.; Mitchell T. C. The vaccine adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A as a TRIF-biased agonist of TLR4. Science 2007, 316, 1628–1632. 10.1126/science.1138963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelmel J. P.; Kroeger N. M.; Gill E. L.; Ulmer C. Z.; Bowden J. A.; Patterson R. E.; Yost R. A.; Garrett T. J. Expanding Lipidome Coverage Using LC-MS/MS Data-Dependent Acquisition with Automated Exclusion List Generation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2017, 28, 908–917. 10.1007/s13361-017-1608-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsugawa H.; Cajka T.; Kind T.; Ma Y.; Higgins B.; Ikeda K.; Kanazawa M.; VanderGheynst J.; Fiehn O.; Arita M. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. 10.1038/nmeth.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins P. D.; Russell J. D.; Coon J. J. LipiDex: An Integrated Software Package for High-Confidence Lipid Identification. Cell Syst. 2018, 6, 621–625. 10.1016/j.cels.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelmel J. P.; Kroeger N. M.; Ulmer C. Z.; Bowden J. A.; Patterson R. E.; Cochran J. A.; Beecher C. W. W.; Garrett T. J.; Yost R. A. LipidMatch: An automated workflow for rule-based lipid identification using untargeted high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry data. BMC Bioinf. 2017, 18, 1–11. 10.1186/s12859-017-1744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng B.; Kopczynski D.; Pratt B. S.; Ejsing C. S.; Burla B.; Hermansson M.; Benke P. I.; Tan S. H.; Chan M. Y.; Torta F.; Schwudke D.; Meckelmann S. W.; Coman C.; Schmitz O. J.; MacLean B.; Manke M. C.; Borst O.; Wenk M. R.; Hoffmann N.; Ahrends R. LipidCreator workbench to probe the lipidomic landscape. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2057 10.1038/s41467-020-15960-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsugawa H.; Kind T.; Nakabayashi R.; Yukihira D.; Tanaka W.; Cajka T.; Saito K.; Fiehn O.; Arita M. Hydrogen Rearrangement Rules: Computational MS/MS Fragmentation and Structure Elucidation Using MS-FINDER Software. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 7946–7958. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartler J.; Triebl A.; Ziegl A.; Trötzmüller M.; Rechberger G. N.; Zeleznik O. A.; Zierler K. A.; Torta F.; Cazenave-Gassiot A.; Wenk M. R.; Fauland A.; Wheelock C. E.; Armando A. M.; Quehenberger O.; Zhang Q.; Wakelam M. J. O.; Haemmerle G.; Spener F.; Köfeler H. C.; Thallinger G. G. Deciphering lipid structures based on platform-independent decision rules. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 1171–1174. 10.1038/nmeth.4470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind T.; Liu K. H.; Lee D. Y.; Defelice B.; Meissen J. K.; Fiehn O. LipidBlast in silico tandem mass spectrometry database for lipid identification. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 755–758. 10.1038/nmeth.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochen M. A.; Chambers M. C.; Holman J. D.; Nesvizhskii A. I.; Weintraub S. T.; Belisle J. T.; Islam M. N.; Griss J.; Tabb D. L. Greazy: Open-Source Software for Automated Phospholipid Tandem Mass Spectrometry Identification. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 5733–5741. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanaswamy P.; Teo G.; Ow J. R.; Lau A.; Kaldis P.; Tate S.; Choi H. MetaboKit: a comprehensive data extraction tool for untargeted metabolomics. Mol. Omics 2020, 16, 436–447. 10.1039/D0MO00030B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsugawa H.; Ikeda K.; Takahashi M.; Satoh A.; Mori Y.; Uchino H.; Okahashi N.; Yamada Y.; Tada I.; Bonini P.; Higashi Y.; Okazaki Y.; Zhou Z.; Zhu Z. J.; Koelmel J.; Cajka T.; Fiehn O.; Saito K.; Arita M.; Arita M. A lipidome atlas in MS-DIAL 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1159–1163. 10.1038/s41587-020-0531-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting Y. S.; Shaffer S. A.; Jones J. W.; Ng W. V.; Ernst R. K.; Goodlett D. R. Automated lipid A structure assignment from hierarchical tandem mass spectrometry data. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 22, 856–866. 10.1007/s13361-010-0055-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison L. J.; Parker W. R.; Holden D. D.; Henderson J. C.; Boll J. M.; Trent M. S.; Brodbelt J. S. UVliPiD: A UVPD-Based Hierarchical Approach for de Novo Characterization of Lipid A Structures. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 1812–1820. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien J. P.; Needham B. D.; Henderson J. C.; Nowicki E. M.; Trent M. S.; Brodbelt J. S. 193 Nm Ultraviolet Photodissociation Mass Spectrometry for the Structural Elucidation of Lipid A Compounds in Complex Mixtures. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 2138–2145. 10.1021/ac403796n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacconelli E.; Carrara E.; Savoldi A.; Harbarth S.; Mendelson M.; Monnet D. L.; Pulcini C.; Kahlmeter G.; Kluytmans J.; Carmeli Y.; Ouellette M.; Outterson K.; Patel J.; Cavaleri M.; Cox E. M.; Houchens C. R.; Grayson M. L.; Hansen P.; Singh N.; Theuretzbacher U.; Magrini N.; Group W. P. P. L. W.; et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew T. L.; Kidd T. J.; Sá Pessoa J.; Conde Álvarez R.; Bengoechea J. A. 2-Hydroxylation of Acinetobacter baumannii Lipid A Contributes to Virulence. Infect. Immun. 2019, 87, e00066-19. 10.1128/IAI.00066-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beceiro A.; Llobet E.; Aranda J.; Bengoechea J. A.; Doumith M.; Hornsey M.; Dhanji H.; Chart H.; Bou G.; Livermore D. M.; Woodford N. Phosphoethanolamine modification of lipid A in colistin-resistant variants of Acinetobacter baumannii mediated by the pmrAB two-component regulatory system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 3370–3379. 10.1128/AAC.00079-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier M. R.; Casella L. G.; Jones J. W.; Adams M. D.; Zurawski D. V.; Hazlett K. R. O.; Doi Y.; Ernst R. K. Unique Structural Modifications Are Present in the Lipopolysaccharide from Colistin-Resistant Strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 4831–4840. 10.1128/AAC.00865-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligh E. G.; Dyer W. J. A Rapid Method of Total Lipid Extraction and Purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. 10.1139/y59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroff M.; Tacken A.; Szabó L. Detergent-accelerated hydrolysis of bacterial endotoxins and determination of the anomeric configuration of the glycosyl phosphate present in the ″Isolated lipid A″ fragment of the Bordetella pertussis endotoxin. Carbohydr. Res. 1988, 175, 273–282. 10.1016/0008-6215(88)84149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers M. C.; MacLean B.; Burke R.; Amodei D.; Ruderman D. L.; Neumann S.; Gatto L.; Fischer B.; Pratt B.; Egertson J.; Hoff K.; Kessner D.; Tasman N.; Shulman N.; Frewen B.; Baker T. A.; Brusniak M. Y.; Paulse C.; Creasy D.; Flashner L.; Kani K.; Moulding C.; Seymour S. L.; Nuwaysir L. M.; Lefebvre B.; Kuhlmann F.; Roark J.; Rainer P.; Detlev S.; Hemenway T.; Huhmer A.; Langridge J.; Connolly B.; Chadick T.; Holly K.; Eckels J.; Deutsch E. W.; Moritz R. L.; Katz J. E.; Agus D. B.; MacCoss M.; Tabb D. L.; Mallick P. A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 918–920. 10.1038/nbt.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sándor V.; Dörnyei Á.; Makszin L.; Kilár F.; Péterfi Z.; Kocsis B.; Kilár A. Characterization of complex, heterogeneous lipid A samples using HPLC–MS/MS technique I. Overall analysis with respect to acylation, phosphorylation and isobaric distribution. J. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 51, 1043–1063. 10.1002/jms.3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sándor V.; Kilár A.; Kilár F.; Kocsis B.; Dörnyei Á. Characterization of complex, heterogeneous lipid A samples using HPLC-MS/MS technique III. Positive-ion mode tandem mass spectrometry to reveal phosphorylation and acylation patterns of lipid A. J. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 53, 146–161. 10.1002/jms.4046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sándor V.; Kilár A.; Kilár F.; Kocsis B.; Dörnyei Á. Characterization of complex, heterogeneous lipid A samples using HPLC–MS/MS technique II. Structural elucidation of non-phosphorylated lipid A by negative-ion mode tandem mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 51, 615–628. 10.1002/jms.3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okahashi N.; Ueda M.; Matsuda F.; Arita M. Analyses of Lipid A Diversity in Gram-Negative Intestinal Bacteria Using Liquid Chromatography–Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Metabolites 2021, 11, 197. 10.3390/metabo11040197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. W.; Cohen I. E.; Tureĉek F.; Goodlett D. R.; Ernst R. K. Comprehensive structure characterization of lipid A extracted from Yersinia pestis for determination of its phosphorylation configuration. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 21, 785–799. 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domon B.; Costello C. E. A systematic nomenclature for carbohydrate fragmentations in FAB-MS/MS spectra of glycoconjugates. Glycoconjugate J. 1988, 5, 397–409. 10.1007/BF01049915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liebisch G.; Vizcaíno J. A.; Köfeler H.; Trötzmüller M.; Griffiths W. J.; Schmitz G.; Spener F.; Wakelam M. J. O. Shorthand notation for lipid structures derived from mass spectrometry. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 1523–1530. 10.1194/jlr.M033506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauling J. K.; Hermansson M.; Hartler J.; Christiansen K.; Gallego S. F.; Peng B.; Ahrends R.; Ejsing C. S. Proposal for a common nomenclature for fragment ions in mass spectra of lipids. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0188394. 10.1371/journal.pone.0188394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J. D.; Kocíncová D.; Westman E. L.; Lam J. S. Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Innate Immun. 2009, 15, 261–312. 10.1177/1753425909106436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froning M.; Helmer P. O.; Hayen H. Identification and structural characterization of lipid A from Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas taiwanensis using liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 34, e8897. 10.1002/rcm.8897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedoux G.; Vallée-Réhel K.; Kooistra O.; Zähringer U.; Haras D. Lipid A components from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (serotype O5) and mutant strains investigated by electrospray ionization ion-trap mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 39, 505–513. 10.1002/jms.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buré C.; Le Sénéchal C.; Macias L.; Tokarski C.; Vilain S.; Brodbelt J. S. Characterization of Isomers of Lipid A from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 by Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry with Higher-Energy Collisional Dissociation and Ultraviolet Photodissociation. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 4255–4262. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c05069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartling C. M.; Raetz C. R. H. Crystal structure and acyl chain selectivity of Escherichia coli LpxD, the N-acyltransferase of lipid A biosynthesis. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 8672–8683. 10.1021/bi901025v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. H.; Raetz C. R. H. Structural basis for the acyl chain selectivity and mechanism of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine acyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104, 13543–13550. 10.1073/pnas.0705833104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totsika M.; Beatson S. A.; Sarkar S.; Phan M. D.; Petty N. K.; Bachmann N.; Szubert M.; Sidjabat H. E.; Paterson D. L.; Upton M.; Schembri M. A. Insights into a multidrug resistant Escherichia coli pathogen of the globally disseminated ST131 lineage: Genome analysis and virulence mechanisms. PLoS One 2011, 6, e26578 10.1371/journal.pone.0026578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kussak A.; Weintraub A. Quadrupole ion-trap mass spectrometry to locate fatty acids on lipid A from Gram-negative bacteria. Anal. Biochem. 2002, 307, 131–137. 10.1016/S0003-2697(02)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madalinski G.; Fournier F.; Wind F. L.; Afonso C.; Tabet J. C. Gram-negative bacterial lipid A analysis by negative electrospray ion trap mass spectrometry: Stepwise dissociations of deprotonated species under low energy CID conditions. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 249-250, 77–92. 10.1016/j.ijms.2005.12.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden C. M.; Akin L. D.; Morrison L. J.; Trent M. S.; Brodbelt J. S. Characterization of Lipid A Variants by Energy-Resolved Mass Spectrometry: Impact of Acyl Chains. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2017, 28, 1118–1126. 10.1007/s13361-016-1542-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S. H.; Park H. G.; Song W. S.; Kim S. M.; Kim E. J.; Yang Y. H.; Kim J. S.; Kim B. G.; Kim Y. G. Structural characterization of phosphoethanolamine-modified lipid A from probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 19762–19771. 10.1039/C9RA02375E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J. C.; O’Brien J. P.; Brodbelt J. S.; Trent M. S. Isolation and Chemical Characterization of Lipid A from Gram-negative Bacteria. J. Visualized Exp. 2013, e50623 10.3791/50623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D. R.; Powers M. J.; Trent M. S.; Brodbelt J. S. Top-Down Characterization of Lipooligosaccharides from Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 9608–9615. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b00940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K. N.; Klein D. R.; Kazi M. I.; Guérin F.; Cattoir V.; Brodbelt J. S.; Boll J. M. Colistin heteroresistance in Enterobacter cloacae is regulated by PhoPQ-dependent 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose addition to lipid A. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 111, 1604–1616. 10.1111/mmi.14240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boll J. M.; Tucker A. T.; Klein D. R.; Beltran A. M.; Brodbelt J. S.; Davies B. W.; Trent M. S. Reinforcing Lipid A Acylation on the Cell Surface of Acinetobacter baumannii Promotes Cationic Antimicrobial Peptide Resistance and Desiccation Survival. mBio 2015, 6, 1–11. 10.1128/mBio.00478-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.-S.; Kim Y.-G.; Joo H.-S.; Kim B.-G. Structural analysis of lipid A from Escherichia coli O157:H7:K– using thin-layer chromatography and ion-trap mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 39, 514–525. 10.1002/jms.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Yoon S. H.; Wang X.; Ernst R. K.; Goodlett D. R. Structural derivation of lipid A from Cronobacter sakazakii using tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 30, 2265–2270. 10.1002/rcm.7712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden C. M.; Herrera C. M.; Williams P. E.; Ricci D. P.; Swem L. R.; Trent M. S.; Brodbelt J. S. Mapping phosphate modifications of substituted lipid A: Via a targeted MS3 CID/UVPD strategy. Analyst 2018, 143, 3091–3099. 10.1039/C8AN00561C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie G.; Ramirez M. S.; Marshall S. H.; Hujer K. M.; Lo C.-C.; Johnson S.; Li P.-E.; Davenport K.; Endimiani A.; Bonomo R. A.; Tolmasky M. E.; Chain P. S. G. Genome Sequences of Two Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates from Different Geographical Regions, Argentina (Strain JHCK1) and the United States (Strain VA360). Genome Announce. 2013, 1, e00168. 10.1128/genomeA.00168-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran A. X.; Lester M. E.; Stead C. M.; Raetz C. R. H.; Maskell D. J.; McGrath S. C.; Cotter R. J.; Trent M. S. Resistance to the Antimicrobial Peptide Polymyxin Requires Myristoylation of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium Lipid A. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 28186–28194. 10.1074/jbc.M505020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim T.-P.; Tan T.-Y.; Lee W.; Sasikala S.; Tan T.-T.; Hsu L.-Y.; Kwa A. L. In-Vitro Activity of Polymyxin B, Rifampicin, Tigecycline Alone and in Combination against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Singapore. PLoS One 2011, 6, e18485 10.1371/journal.pone.0018485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M. D.; Nickel G. C.; Bajaksouzian S.; Lavender H.; Murthy A. R.; Jacobs M. R.; Bonomo R. A. Resistance to Colistin in Acinetobacter baumannii Associated with Mutations in the PmrAB Two-Component System. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3628–3634. 10.1128/AAC.00284-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. W.; Shaffer S. A.; Ernst R. K.; Goodlett D. R.; Tureček F. Determination of pyrophosphorylated forms of lipid A in Gram-negative bacteria using a multivaried mass spectrometric approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 12742–12747. 10.1073/pnas.0800445105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki E. M.; O’Brien J. P.; Brodbelt J. S.; Trent M. S. Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa LpxT reveals dual positional lipid A kinase activity and co-ordinated control of outer membrane modification. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 94, 728–741. 10.1111/mmi.12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst R. K.; Moskowitz S. M.; Emerson J. C.; Kraig G. M.; Adams K. N.; Harvey M. D.; Ramsey B.; Speert D. P.; Burns J. L.; Miller S. I. Unique lipid A modifications in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from the airways of patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, 1088–1092. 10.1086/521367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llobet E.; Martínez-Moliner V.; Moranta D.; Dahlström K. M.; Regueiro V.; Tomás A.; Cano V.; Pérez-Gutiérrez C.; Frank C. G.; Fernández-Carrasco H.; Insua J. L.; Salminen T. A.; Garmendia J.; Bengoechea J. A. Deciphering tissue-induced Klebsiella pneumoniae lipid A structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 112, E6369–E6378. 10.1073/pnas.1508820112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilár A.; Dörnyei Á.; Kocsis B. Structural characterization of bacterial lipopolysaccharides with mass spectrometry and on- and off-line separation techniques. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2013, 32, 90–117. 10.1002/mas.21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurtsen J.; Steeghs L.; Hove J. T.; van der Ley P.; Tommassen J. Dissemination of Lipid A Deacylases (PagL) among Gram-negative Bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 8248–8259. 10.1074/jbc.M414235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde B. M.; Ben Zakour N. L.; Stanton-Cook M.; Phan M.-D.; Totsika M.; Peters K. M.; Chan K. G.; Schembri M. A.; Upton M.; Beatson S. A. The Complete Genome Sequence of Escherichia coli EC958: A High Quality Reference Sequence for the Globally Disseminated Multidrug Resistant E. coli O25b:H4-ST131 Clone. PLoS One 2014, 9, e104400 10.1371/journal.pone.0104400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee S. K.; Chan S. C. M.; Guan X. L.; Yap E. P. H. Draft Genome Sequence of Enterobacter hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii Strain BEI01. Microbiol. Resour. Announce. 2021, 10, e00406. 10.1128/MRA.00406-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Srinivas S.; Xu Y.; Wei W.; Feng Y. Genetic and Biochemical Mechanisms for Bacterial Lipid A Modifiers Associated with Polymyxin Resistance. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2019, 44, 973–988. 10.1016/j.tibs.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.