Abstract

The dimensionality and factorial invariance of scores on the Self-Objectification Beliefs and Behaviors Scale (SOBBS) were examined with a sample of 590 transgender and nonbinary participants. Results failed to disconfirm the two-factor model and provided adequate estimates of internal consistency reliability. Strong, strict, and structural invariance of scores were observed.

Keywords: transgender, confirmatory factor analysis, objectification theory, Self-Objectification Beliefs and Behaviors Scale (SOBBS), construct validity

Self-objectification refers to an internalization process by which people learn to “treat themselves as objects” (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997, p. 177). It is associated with maladaptive behaviors (e.g., disordered eating; Daniels et al., 2020) and other psychiatric syndromes (e.g., depression; Jones & Griffiths, 2015). Self-objectification is also a core theoretical construct in objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Traditional objectification research (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997) focuses on the experiences of cisgender women and girls (Daniels et al., 2020; Moradi & Huang, 2008). A smaller yet growing body of work examines the impact of objectification on cisgender men, specifically as it relates to eating disorders, the drive for muscularity, and body image issues (see Filice et al., 2020).

However, even though recent evidence suggests that objectification-based mechanisms drive deleterious outcomes among binary transgender and nonbinary adults (hereafter TGNB, or “TransGender and NonBinary”; Brewster et al., 2019; Comiskey et al., 2020), there is a wide gap in the self-objectification literature regarding the assessment of TGNB individuals’ experiences of self-objectification. Emerging research on objectification among TGNB adults tends to use instruments, such as the Self-Objectification Beliefs and Behaviors Scale (SOBBS; Lindner & Tantleff-Dunn, 2017), without establishing the psychometric properties of the scores on the instrument with this understudied population. Generally, self-objectification measures tend to be constructed and validated using scores from cisgender samples.

It is important to examine whether the major constructs comprising self-objectification and, consequently, the operationalization of the construct, are perceived similarly among TGNB adults. To advance the literature, we sought to validate scores on the SOBBS with a community-dwelling, non-clinical sample of TGNB adults. Validation of scores on such a measure could lead to greater understanding of how self-objectification manifests in the lives of TGNB adults, enhance clinical understanding of the construct, and promote social justice in research by ensuring that best practices in psychometrics extend to this understudied population.

Objectification Theory

In their seminal work, Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) developed objectification theory, which is based on the premise that “bodies exist within social and cultural contexts” (p. 174). From an objectification perspective, the social construction of the body is inherently tied to oppression and sexual violence, particularly among cisgender women (Moradi & Huang, 2008), and one of the mechanisms through which gender-based oppression operates is through the objectifying gaze (Daniels et al., 2020; Flores et al., 2018; Tebbe et al., 2018). Targets of the objectifying gaze tend towards internalization of this third-party perspective (i.e., self-objectification; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Yet, to date, relatively little is known about the ways in which the objectifying gaze becomes internalized among TGNB adults and how it also might function differently among binary transgender and nonbinary individuals. Based on findings among cisgender samples, individuals tend to self-objectify as they begin to view their bodies as something to be looked at and evaluated (Calogero, 2011; Chmielewski & Yost, 2013; Daniels et al., 2020). Although there are potential social benefits to self-objectification (desirability, popularity, power; Tebbe et al., 2018), there are many potential negative effects as well, including shame (Daniels et al., 2020; Moradi & Huang, 2008), anxiety (Chmielewski & Yost, 2013; Flores et al., 2018), depression (Jones & Griffiths, 2015; Moradi & Huang, 2008), and eating disorders (Daniels et al., 2020; Moradi & Huang, 2008). Furthermore, when individuals do not meet the internalized or sociocultural body ideals that they have been socialized to view as desirable, feelings of worthlessness (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), self-critical appraisals (McGuire et al., 2016), and a drive to “correct” one’s body occur (Chmielewski & Yost, 2013; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Despite nearly 25 years of theoretical development, empirical testing, and documentation of adverse outcomes, the literature base on objectification broadly and self-objectification in particular is sparse among TGNB adults.

Objectification Among TGNB Individuals

Preliminary evidence suggests that the objectification-based mechanisms driving adverse outcomes among cisgender people may manifest uniquely among TGNB adults. Some literature examines how sexual objectification operates within a dehumanizing and fetishizing framework (Anzani et al., 2021; Brewster et al., 2019; Flores et al., 2018; Gamarel et al., 2020; Tebbe et al., 2018) which, for TNGB adults, can engender feelings of disgust, fear, and victimization (Anzani et al., 2021; Flores et al., 2018). These reactions are similar to research with cisgender women (Daniels et al., 2020; Moradi & Huang, 2008). However, it is important to note the unique role that transgender discrimination and transgender congruence play in some of the core tenets of objectification theory (Brewster et al., 2019; Comiskey et al., 2020; Cusack & Galupo, 2021; Velez et al., 2016). For example, experiencing transgender discrimination can negatively impact body satisfaction and increase body surveillance (Velez et al., 2016). Transgender congruence (i.e., feeling like one’s body is congruent with one’s gender) has been shown to decrease body surveillance (Comiskey et al., 2020). Other evidence suggests that TGNB individuals may seek to meet sociocultural standards of beauty in an effort to feel congruent in their bodies and pass as cisgender (Brewster et al., 2019; Comiskey et al., 2020; McGuire et al., 2016). In other words, while TGNB individuals experience core aspects of objectification theory, such as body surveillance and body shame (Cusack & Galupo, 2021; Flores et al., 2018; McGuire et al., 2016), the context in which these occur could significantly differ from the experiences of cisgender women. For example, body checking is typically conceived as a behavioral manifestation of self-objectification among cisgender women (e.g., Moradi & Huang, 2008), but some evidence suggests that this body surveillance may function to minimize dysphoria among TGNB people and act as a safety mechanism in efforts to pass as cisgender (Anzani et al., 2021; Cusack & Galupo, 2021; Flores et al., 2018; Gamarel et al., 2020).

Given these recent findings, objectification-based mechanisms warrant greater examination among TGNB adults because (a) there is evidence of adverse outcomes, (b) objectification-based pathways identified among cisgender samples may function differently with TGNB samples, and (c) the unique context of transgender discrimination may influence the experience of self-objectification. Professional counselors need a tool with validated scores for appraising self-objectification among TGNB individuals. A self-objectification instrument whose scores are validated with a TGNB sample has potential to enable future investigations into how objectification-based mechanisms operate in this population. One instrument that effectively operationalizes self-objectification is the SOBBS.

Development and Utility of the SOBBS

Answering calls to test the validity of scores on self-objectification scales among gender-diverse groups (Daniels et al., 2020; Lindner & Tantleff-Dunn, 2017), we tested the internal structure of scores of the SOBBS with a sample of TGNB adults. Lindner and Tantleff-Dunn (2017) developed and conducted two studies to initially validate scores on the SOBBS. They generated items via focus groups and expert ratings, extracted factors with exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and established convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity of scores in the first study. In the second study, further evidence was provided for construct validity, as the two-factor model failed to be disconfirmed using scores from a separate, online sample of 175 young adult cisgender women (Lindner & Tantleff-Dunn, 2017). Subsequent empirical studies provided additional support for the psychometric properties of the SOBBS, primarily establishing reasonable estimates of convergent and concurrent validity (rs = .13–.70; see Calogero et al., 2020; Huellemann & Calogero, 2020; Maheux et al., 2021; Osa & Calogero, 2020; Terán et al., 2021). Estimates of internal consistency reliability of scores on the SOBBS ranged from α = .87 to α = .93.

Despite an accumulation of psychometric evidence, to our knowledge, Lindner and Tantleff-Dunn (2017) are the only investigators to demonstrate internal structure validity evidence of scores via a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with a sample of cisgender participants. The dearth of internal structure validity evidence of scores on the SOBBS among different populations is concerning, as internal structure validity evidence is a fundamental element of score validation in social sciences research (Kalkbrenner, 2021). Since self-objectification can confer risk for deleterious outcomes among TGNB adults (e.g., McGuire et al., 2016), their exclusion from these psychometric studies limits critical, necessary research on objectification-related mechanisms of mental health disparities observed in this vulnerable population.

Given the “inconsistencies in prior attempts to operationalize” the construct (Moradi, 2010, p. 145), Lindner and Tantleff-Dunn (2017) argued that the SOBBS was an advancement in the measurement of self-objectification. Thus, we chose to examine the internal structure of scores on the SOBBS instead of other self-objectification measures for several reasons. First, unlike the Objectified Body Consciousness Body Surveillance Scale (OBC-Surveillance; McKinley & Hyde, 1996), the SOBBS assesses (a) the internalization of an observer’s perspective and (b) the equating of the body as the self, the latter of which includes items that measure privileging physical characteristics over physical capability, cognition, and affect. Second, the SOBBS subsumes the same content domain as the Self-Objectification Questionnaire (SOQ; Noll & Fredrickson, 1998), but evinces stronger evidence for reliability and validity of scores (Lindner & Tantleff-Dunn, 2017). Indeed, in Calogero’s (2011) extensive review, significant concerns were raised about whether the SOQ sufficiently covers the domain of self-objectification among gender-diverse individuals. A final reason for examining the SOBBS is its usefulness as a complement to the OBC-Surveillance (Lindner & Tantleff-Dunn, 2017).

A simultaneous examination of self-objectification and body surveillance in future research may have unique theoretical importance among TGNB adults. If scores on the SOBBS were validated with TGNB adults, researchers would be better equipped to reveal which objectification constructs are salient for this population. For instance, while body surveillance is an important predictor of key objectification constructs, extant studies have focused on body surveillance as a behavioral manifestation of self-objectification (Velez et al., 2016) without attending to self-objectification directly. Preliminary evidence (Anzani et al., 2021; Comiskey et al., 2020; Cusack & Galupo, 2021; Flores et al., 2018; Gamarel et al., 2020; McGuire et al., 2016) suggests that self-objectification, as a distinct construct, warrants further examination with TGNB adults. Thus, validating scores on the SOBBS with TGNB adults would fill an important gap in objectification research.

Factorial Invariance Across Gender-Diverse Groups

The second purpose of this study was to evaluate the factorial invariance of scores on the SOBBS across gender-diverse groups. Factorial invariance determines whether a construct, such as self-objectification, has an equivalent meaning and measurement structure across groups (Dimitrov, 2010). According to Dimitrov, hierarchical measurement models within the framework of CFA establish factorial invariance via configural invariance, measurement invariance (i.e., extent to which the error variance is comparable between groups), and structural invariance (i.e., constant variability of factor variances and covariances). We examined metric (i.e., multigroup equivalence of factor loadings) and scalar (i.e., multigroup equivalence of item intercepts) invariance as these are the criteria for strong measurement invariance.

Testing for factorial invariance may reveal important between-group differences in the functionality and meaning of the SOBBS across binary transgender and nonbinary adults. Too often, binary transgender and nonbinary groups are lumped together even though evidence suggests that objectification-based mechanisms may manifest uniquely and mutate divergently (e.g., Comiskey et al., 2020; Cusack & Galupo, 2020; Flores et al., 2018). Since objectifying experiences may be perceived as gender affirming under certain contexts (Anzani et al., 2021; Flores et al., 2018), such as during different stages of binary transition, an emphasis on treating the body-as-self may emerge for binary transgender but not nonbinary adults. Additionally, transgender women’s eating concerns (Brewster et al., 2019) or transgender men’s compulsive exercise (Velez et al., 2016) both may be motivated by the internalization of an observer’s perspective, but in light of evidence that some nonbinary individuals resist sociocultural standards of attractiveness (Cusack & Galupo, 2021), their self-objectification may not result in equivalent pathological forms.

Factorial invariance of scores on the SOBBS was hypothesized for three reasons. First, according to objectification theory, “bodies exist within social and cultural contexts” (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997, p. 174). In the United States, TGNB adults are subjected to similar systemic influences on their bodies and identities, such as the devaluation of bodies that are not cisgender (Lennon & Mistler, 2014). This shared context may serve as a common etiological root of self-objectification. Second, TGNB adults are fetishized (Anzani et al., 2021) which, through the lens of objectification theory, aims a “sexually objectifying gaze” (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997, p. 176) at this community. Because sexualized gazing is a primary mechanism of sexual objectification, both groups are at risk for internalizing an observer’s perspective. Third, experiences of gender dysphoria might invite greater attention to the body which, in a cultural context that privileges cisgender bodies, might increase the risk of treating the body as the self. Nonetheless, since the perception of self-objectification cannot be assumed equivalent across TGNB groups, establishing factorial invariance of scores on the SOBBS is a necessary next step in objectification research with gender-diverse populations.

The Present Study

Extant literature has established a compelling connection between self-objectification and adverse mental health consequences in cisgender women (Calogero, 2011; Daniels et al., 2020). Although emerging evidence suggests similar deleterious pathways in TGNB adults (e.g., Brewster et al., 2019; Velez et al., 2016), objectification scholarship with this population is relatively nascent and, thus, would benefit from psychometric studies of key constructs. In particular, self-objectification has received little empirical attention in research with TGNB adults, likely due to the lack of instruments with validated scores. If scores are validated with TGNB adults, the SOBBS would have utility for enhancing sexual objectification scholarship because this measure, relative to other instruments, has improved the operationalization of self-objectification. Given the unknown internal structure of SOBBS scores and the potential for self-objectification to manifest uniquely for binary transgender versus nonbinary adults, the following research questions (RQs) guided this investigation. RQ1: Do scores on the SOBBS fail to disconfirm the two-factor structure with a sample of TGNB adults? RQ2: Do scores on the SOBBS maintain factorial invariance across binary transgender and nonbinary adults?

Method

Procedures and Participants

After receiving approval from the authors’ Institutional Review Board, an online survey was constructed in REDCap online survey platform. Survey links were posted to internet forums used by TGNB communities (e.g., Reddit, Tumblr), shared on listservs for gender-diverse scholars and communities, and distributed to trans-specific organizations. A non-probability sampling approach (i.e., convenience sampling) was selected because TGNB adults are a hard-to-reach population and, compared to probability samples (i.e., random sampling) of TGNB participants, are large enough to perform rigorous subgroup analyses (i.e., invariance testing; Henderson et al., 2019). Data collection lasted from June 2020 to February 2021. Participants provided informed consent, completed questionnaires, and were debriefed textually. Participants were invited to enter a raffle for a $25 Amazon gift card. Sixty gift cards were distributed. Data are available on the Open Science Framework. This study was not preregistered.

After passing a CAPTCHA test, a total of 1,002 community-dwelling, non-clinical participants started a survey about TGNB mental health. However, 364 cases were removed for the following reasons: incomplete data (missing over 50% of their data; Scheffer, 2002; n = 205), failing an attention check (e.g., please select strongly disagree; n = 82), living outside the United States (n = 39), providing an inappropriate age (n = 17), identifying as cisgender (n = 9), failing to specify their sex assigned at birth (n = 7), entering duplicate emails (n = 3), or not providing consent (n = 2). SOBBS items were converted to standardized z-scores to check for univariate outliers (z > |3.29|); 24 were detected in the original dataset of 638 observations. Furthermore, Mahalanobis (D) distances were computed to identify multivariate outliers in the dataset. Specifically, the Mahalanobis distances were compared to a chi-square distribution with the same degrees of freedom. The probabilities were compared against the p < .001 threshold to identify multivariate outliers and revealed 24 multivariate outliers, which were removed from the data set. Mardia’s multivariate test for normality was computed and approximately half of the CRs were over 1.96. However, data sets large enough for SEM tend to fail Mardia’s test (Stevens, 2009). Thus, Mardia’s test is oftentimes interpreted with univariate kurtosis values, with values less than 3 indicating that the variable is consistent with a normal distribution (Westfall & Henning, 2013). In the current data set, all the kurtosis values were < 3. A robust sample of 590 TGNB participants remained following the deletion of univariate and multivariate outliers (49.8% nonbinary; Mage = 26.8, SD = 10.3). Among binary transgender participants, 77.4% (n = 229) were currently taking hormones, 61.5% (n = 182) reported a desire for top surgery in the future, and 39.5% (n = 117) stated they would like to have bottom surgery in the future. Among nonbinary participants, 48.3% (n = 142) were currently taking hormones, 50% (n = 147) reported a desire for top surgery in the future, and 15.3% (n = 45) indicated they would like to have bottom surgery in the future. For additional demographics, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Social Demographic Features of Participants

| Variable | Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transgender (n = 296) | Nonbinary (n = 294) | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Sex assigned at birth | ||||

| Female | 215 | 72.60 | 242 | 82.30 |

| Male | 81 | 27.40 | 52 | 17.70 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Bi/pansexual | 130 | 43.90 | 111 | 37.80 |

| Queer | 32 | 10.80 | 94 | 32.00 |

| Gay/lesbian | 74 | 25.00 | 37 | 12.60 |

| Other | 16 | 5.41 | 30 | 10.20 |

| Asexual | 12 | 4.05 | 19 | 6.46 |

| Heterosexual | 31 | 10.50 | 3 | 1.02 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| European American | 220 | 74.30 | 235 | 79.90 |

| Multiethnic | 34 | 11.50 | 36 | 12.20 |

| Latinx | 17 | 5.74 | 11 | 3.74 |

| Other | 8 | 2.70 | 5 | 1.70 |

| African / Caribbean American | 10 | 3.38 | 4 | 1.36 |

| Asian American | 7 | 2.36 | 2 | 0.68 |

| Arab American | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.34 |

| Education | ||||

| Some college | 102 | 34.50 | 118 | 40.10 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 58 | 19.60 | 61 | 20.70 |

| Some high school or diploma | 65 | 22.00 | 43 | 14.60 |

| Graduate school | 35 | 11.80 | 37 | 12.60 |

| Associate degree | 28 | 9.46 | 30 | 10.20 |

| Tradeperson certificate | 7 | 2.36 | 5 | 1.70 |

| Income | ||||

| Less than $20,000 | 149 | 50.30 | 196 | 66.70 |

| $20,000 - $44,999 | 84 | 28.40 | 62 | 21.10 |

| $45,000 - $139,999 | 48 | 16.20 | 29 | 9.86 |

| More than $140,000 | 11 | 3.72 | 4 | 1.36 |

| Region | ||||

| East Coast | 93 | 31.40 | 105 | 35.70 |

| Midwest | 75 | 25.30 | 60 | 20.40 |

| West Coast | 51 | 17.20 | 50 | 17.00 |

| Southwest | 30 | 10.10 | 35 | 11.90 |

| Rocky Mountains | 18 | 6.08 | 25 | 8.50 |

| Southeast | 25 | 8.45 | 18 | 6.12 |

| Alaska / Hawai’i | 3 | 1.01 | 0 | 0.00 |

Note. Participants who did not provide information for a demographic category are not reported.

Data Analytic Plan

Our data analytic strategy consisted of two psychometric analyses. First, we computed a single-order CFA to test the dimensionality of SOBBS scores with the total sample. All analyses were computed in IBM SPSS Amos version 25. The SOBBS items were entered into a CFA using a maximum likelihood estimation method because the data met normality assumptions, such as skewness and kurtosis values < |1| or skewness < |2| and kurtosis < |7|, the latter indicating extreme deviations from normality (Dimitrov, 2012; Mvududu & Sink, 2013). In the present data set, the majority of skewness and kurtosis values were < |1| and zero items exceeded a skewness or kurtosis value > |1.5|. We used the joint recommendations of Dimitrov (2012) and Schreiber et al. (2006) for interpreting model fit for CFA, including the comparative fit index (CFI, .90 to .95 = acceptable fit and > .95 = strong fit), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .08), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR < .08).

The factorial invariance of scores on instrumentation can vary between different subgroups of a larger sample (Dimitrov, 2012) and previous investigators found differences in self-objectification by gender identity (e.g., Anzani et al., 2021; Flores et al., 2018). To this end, a MCFA was computed to answer the second research question about the psychometric equivalence of scores on the SOBBS by gender identity. We referred to the following thresholds for investigating invariance: a non-significant Satorra and Bentler Chi-square difference test, < Δ 0.010 in CFI, < Δ 0.015 in RMSEA, and < Δ 0.030 in SRMR for metric invariance or < Δ 0.015 in SRMR for scalar invariance (Chen, 2007; Putnick & Bornstein, 2016). The configural invariance of scores was compared by testing if at least one factor loading in each group is equal (tb1 = bb2 = 1). The metric invariance model tested the invariance between the other factor loadings across both groups (tb2 = bb2, tb3 = bb3 … tb14 = bb14). In the scalar invariance model, both the factor loadings and the item intercepts were set equal (tbu1 = bbu1, tbu2 = tbu3 … tbu14 = bbu14). In residual invariance model, the factor loadings, item intercepts, and residual variances (tbe1 = bbe2 … tbe14 = bbe14) were set equal to one another. Finally, in the structural model factor loadings, item intercepts, residual variances, and factor variances (MV1 = FV1) were all set equal to one another.

Internal consistency reliability, Cronbach’s coefficient alpha (α) in particular, is the most reported reliability index in psychometric research across the social sciences (McNeish, 2018). Despite the utility of coefficient alpha, it can underestimate or overestimate the true reliability of scores when the data violate any one of alpha’s assumptions (McNeish, 2018). McDonald’s coefficient omega (ω) tends to be a more stable internal consistency reliability estimate in psychometric research because ω is robust to most of α’s assumptions. To these ends, we computed both alpha and omega internal consistency reliability estimates for scores on the SOBBS.

We ensured that the data set met the necessary requirements and assumptions for factor analytic testing. Our final sample size (N = 590) exceeded Kalkbrenner’s (2021) recommendations for minimum sample size in CFA (10 participants for each estimated parameter or 200 participants, whichever produces a larger sample). The sample also exceeded Meade and Kroustalis’s (2006) recommendation of at least 200 per group for invariance testing.

Instrumentation

Demographic Questionnaire

Participants responded to a demographic questionnaire and reported their age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender. Sex assigned at birth and current gender identity was used to assess gender. Participants provided information on their regional affinity, income level, educational attainment, hormone status, and top/bottom surgery status.

Self-Objectification Beliefs and Behaviors Scale

The SOBBS (Lindner & Tantleff-Dunn, 2017) is a 14-item, self-administered questionnaire assessing self-objectification as two factors: the Observer’s Perspective (e.g., “I often think about how my body must look to others”) and the Body as Self (e.g., “How I look is more important to me than how I think or feel”). The SOBBS generates two subscale scores and a total score. Response choices are semi-anchored on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate higher levels of self-objectification. No items are reverse scored. As mentioned previously, Lindner and Tantleff-Dunn (2017) established convergent, discriminant, construct, and incremental validity for the SOBBS as the two-factor model failed to be disconfirmed on a separate sample from the original construction and SOBBS scores were significantly correlated to similar measures, such as appearance anxiety, body consciousness, and interpersonal objectification. The test-retest reliability estimate of the SOBBS Total Score (r = .89) was excellent. During a CFA (Lindner & Tantleff-Dunn, 2017), Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for the Total Score (α = .92), Observer’s Perspectives (α = .91), and Body as Self (α = .92) scales were also excellent. Similarly, in the present study, satisfactory internal consistency reliability evidence emerged for the Total Score (α = .86, ωh = .74), scores on the Observer’s Perspectives (α = .85, ω = .85), and scores on the Body as Self (α = .84, ω = .84) subscales of the SOBBS.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

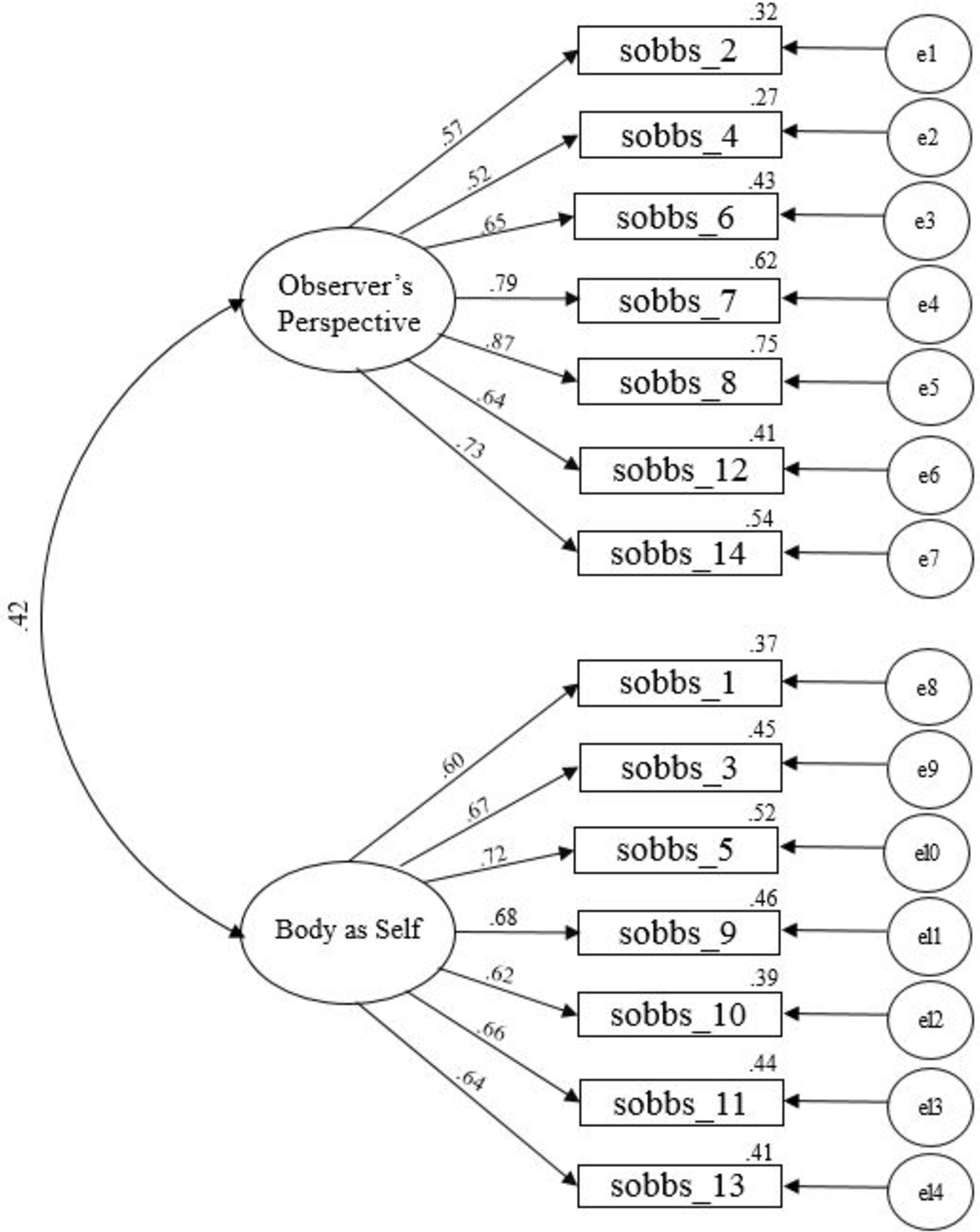

Item-level descriptive statistics are reported in Table 2. Collectively, the inter-item correlation matrix (see Table 3), the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO = .88), and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (B [91] = 3,247.42, p < .001) supported that the data were appropriate for factor analysis (Mvududu & Sink, 2013). The following descriptive statistics emerged for scores on the Body as Self scale (M = 2.24, SD = 0.77, skewness = 0.63, and kurtosis = 0.20) and the Observer’s Perspective scale (M = 4.10, SD = 0.67, skewness = −0.78, and kurtosis = 0.36). The SOBBS items were entered into a CFA based on structural equation modeling and the following results emerged: CFI = .92; RMSEA = .076, 90% CI [.067, .084]; and SRMR = .054. Taken together, the CFA findings supported adequate internal structure validity for scores on the SOBBS based on the recommendations of Dimitrov (2012) and Schreiber et al. (2006). We did not correlate any error terms or make any modifications to the CFA model (see Figure 1). Collectively, the CFA results revealed that the two-dimensional model failed to be disconfirmed with the total sample, so we proceeded with invariance testing.

Table 2.

Item-Level Descriptive Statistics (N = 590)

| Items | Factor | M | SD | Skew | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Looking attractive to others is more important to me than being happy with who I am on the inside. | Observer’s Perspective | 2.15 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.11 |

| 2. I try to imagine what my body looks like to others (i.e., like I am looking at myself from the outside). | Body as Self | 4.03 | 0.98 | −1.18 | 1.22 |

| 3. How I look is more important to me than how I think or feel. | Observer’s Perspective | 2.35 | 1.02 | 0.59 | −0.21 |

| 4. I choose specific clothing or accessories based on how they make my body appear to others. | Body as Self | 3.91 | 0.99 | −0.92 | 0.47 |

| 5. My physical appearance is more important than my personality. | Observer’s Perspective | 2.08 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 0.29 |

| 6. When I look in the mirror, I notice areas of my appearance that I think others will view critically. | Body as Self | 4.34 | 0.79 | −1.21 | 1.10 |

| 7. I consider how my body will look to others in the clothing I am wearing. | Body as Self | 4.33 | 0.72 | −1.09 | 1.50 |

| 8. I often think about how my body must look to others. | Body as Self | 4.13 | 0.92 | −1.11 | 0.91 |

| 9. My physical appearance says more about who I am than my intellect. | Observer’s Perspective | 2.05 | 1.05 | 0.87 | 0.07 |

| 10. How sexually attractive others find me says something about who I am as a person | Observer’s Perspective | 2.39 | 1.17 | 0.41 | −0.89 |

| 11. My physical appearance is more important than my physical abilities. | Observer’s Perspective | 2.45 | 1.10 | 0.50 | −0.54 |

| 12. I try to anticipate others’ reactions to my physical appearance. | Body as Self | 3.91 | 0.97 | −1.01 | 0.81 |

| 13. My body is what gives me value to other people | Observer’s Perspective | 2.23 | 1.16 | 0.62 | −0.46 |

| 14. I have thoughts about how my body looks to others even when I am alone. | Body as Self | 4.09 | 1.04 | −1.33 | 1.39 |

Note. SEKurtosis = 0.20, SESkewness = 0.10.

Table 3.

Inter-Item Correlation Matrix of the Self-Objectification Beliefs and Behaviors Scale (N = 590)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | — | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | .21 | — | |||||||||||

| 1 | 3 | .53 | .21 | — | ||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | .18 | .30 | .32 | — | |||||||||

| 1 | 5 | .41 | .08* | .55 | .27 | — | ||||||||

| 2 | 6 | .17 | .39 | .20 | .32 | .14 | — | |||||||

| 2 | 7 | .13 | .40 | .20 | .49 | .17 | .53 | — | ||||||

| 2 | 8 | .17 | .49 | .29 | .40 | .20 | .55 | .71 | — | |||||

| 1 | 9 | .33 | .10* | .41 | .25 | .57 | .16 | .18 | .19 | — | ||||

| 1 | 10 | .44 | .23 | .34 | .24 | .40 | .21 | .23 | .22 | .39 | — | |||

| 1 | 11 | .38 | .14 | .41 | .30 | .45 | .21 | .28 | .27 | .50 | .42 | — | ||

| 2 | 12 | .16 | .42 | .22 | .34 | .17 | .39 | .50 | .54 | .17 | .26 | .25 | — | |

| 1 | 13 | .35 | .13* | .37 | .23 | .43 | .17 | .18 | .25 | .45 | .50 | .43 | .29 | — |

| 2 | 14 | .15 | .43 | .26 | .34 | .18 | .51 | .52 | .66 | .14 | .21 | .25 | .49 | .28 |

Note. Factor 1 = Observer’s Perspective. Factor 2 = Body as Self. All correlations significant at the .001 level except those marked with a single asterisk (*), indicating significance at the .05 level.

Figure 1. CFA Path Model with Standardized Loadings.

Note. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the SOBBS. Each item has a corresponding error term. For wording of the individual items, see Table 2. The standardized factor loading for the Body as Self factor ranged from .60 to .72. The standardized loadings for the Observer’s Perspective factor ranged from .52 to .87. The covariance between the factors was .42.

Factorial Invariance Testing

An MCFA was computed (see Table 4) to answer the second research question about the psychometric equivalence of scores on the SOBBS by gender identity (binary transgender, n = 296; nonbinary, n = 294). The Δ in CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR all revealed strong measurement invariance across models from the configural to metric model (ΔCFI = 0.002, ΔRMSEA = 0.001, ΔSRMR = 0.0015) and from the metric to scalar model (metric (ΔCFI = 0.003, ΔRMSEA = 0.001, ΔSRMR < 0.0001) for scores on the SOBBS. Results also yielded support for strict invariance (residual) as well as structural invariance of scores (ΔCFI = 0.008, ΔRMSEA = 0.001, ΔSRMR = 0.0048). We ran a test of structured mean differences and the model was not identified. This indicates that comparing the constrained means between one group to the structural means of the other group did not yield a sufficient number of constraints to produce an identifiable model. However, even without the test of structured mean differences, the collective results (strong, strict, and structural invariance) still make a compelling case for the invariance of SOBBS scores with our sample of transgender and nonbinary participants.

Table 4.

Multiple-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Measurement Invariance of the Self-Objectification Beliefs and Behaviors Scale

| Invariance Forms | CFI | ΔCFI | RMSEA | ΔRMSEA | RMSEA CIs | SRMR | ΔSRMR | Model Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Identity: Transgender vs. Nonbinary | ||||||||

| Configural | .923 | .052 | .046; .059 | .0599 | ||||

| Metric | .921 | .002 | .051 | .001 | .045; .057 | .0614 | .0015 | Configural |

| Scalar | .918 | .003 | .050 | .001 | .044; .056 | .0614 | <.0001 | Metric |

| Residual | .910 | .008 | .051 | .001 | .045; .056 | .0662 | .0048 | Scalar |

| Structural | .910 | <.001 | .050 | .001 | .045; .056 | .0663 | .0001 | Residual |

Note. Interpretation of model fit for CFA used the following thresholds (Dimitrov, 2012; Schreiber et al., 2006) including the χ2comparative fit index (CFI, .90 to .95 = acceptable fit and > 0.95 = strong fit), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR < 0.08). Interpretation of invariance used the following thresholds (Chen, 2007; Putnick & Bornstein, 2016): < Δ 0.010 in CFI, < Δ 0.015 in RMSEA, and < Δ 0.030 in SRMR for metric invariance or < Δ 0.015 in SRMR for scalar invariance; df = degrees of freedom. All deltas (Δ) are absolute values.

Factorial invariance testing was also computed for each subscale, including Observer’s Perspective (see Table 5) and Body as Self (see Table 6). In terms of the Observer’s Perspective, the Δ in CFI and RMSEA revealed strong measurement invariance from the configural to the metric model (ΔCFI = 0.006, ΔRMSEA < 0.001) and from the metric to the scalar model (ΔCFI = 0.001, ΔRMSEA = 0.003) and provided evidence for structural invariance. However, the Δ in CFI was slightly beyond the threshold for strict invariance from the scalar to the residual model (ΔCFI = 0.011), although the Δ in RMSEA was acceptable (ΔRMSEA = 0.003). In terms of the Body as Self, the Δ in CFI and RMSEA revealed strong measurement invariance from the configural to the metric model (ΔCFI = 0.001, ΔRMSEA = 0.005) and from the metric to the scalar model (ΔCFI =0.007, ΔRMSEA = 0.004) and provided evidence for strict invariance from the scalar to the residual model (ΔCFI =0.004 , ΔRMSEA = 0.004) as well as structural invariance of scores. A review of the path model coefficient between factors (see Figure 1) and a Pearson product moment correlation (r = .40) were in the moderate range, indicating that factors were measuring separate dimensions of a related construct.

Table 5.

Multiple-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Measurement Invariance of the Observer’s Perspective Scale of the SOBBS

| Invariance Forms | CFI | ΔCFI | RMSEA | ΔRMSEA | RMSEA CIs | Model Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural | .968 | .055 | .041; .069 | |||

| Metric | .962 | .006 | .055 | <.001 | .043; .069 | Configural |

| Scalar | .961 | .001 | .052 | .003 | .040; .065 | Metric |

| Residual | .950 | .011 | .055 | .003 | .044; .064 | Scalar |

| Structural | .951 | .001 | .054 | .001 | .043; .065 | Residual |

Note. Interpretation of model fit for CFA used the following thresholds (Dimitrov, 2012; Schreiber et al., 2006): χ2 comparative fit index (CFI, .90 to .95 = acceptable fit and > 0.95 = strong fit), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08). Interpretation of invariance used the following thresholds (Chen, 2007; Putnick & Bornstein, 2016): < Δ 0.010 in CFI and < Δ 0.015 in RMSEA for measurement invariance; df = degrees of freedom. All deltas (Δ) are absolute values.

Table 6.

Multiple-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Measurement Invariance of the Body as Self Scale of the SOBBS

| Invariance Forms | CFI | ΔCFI | RMSEA | ΔRMSEA | RMSEA CIs | Model Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural | .915 | .083 | .070; .096 | |||

| Metric | .916 | .001 | .076 | .007 | .064; .089 | Configural |

| Scalar | .911 | .005 | .072 | .004 | .061; .084 | Metric |

| Residual | .907 | .004 | .068 | .004 | .058; .079 | Scalar |

| Structural | .907 | <.001 | .067 | .001 | .057; .078 | Residual |

Note. Interpretation of model fit for CFA used the following thresholds (Dimitrov, 2012; Schreiber et al., 2006): comparative fit index (CFI, .90 to .95 = acceptable fit and > 0.95 = strong fit), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08). Interpretation of invariance used the following thresholds (Chen, 2007; Putnick & Bornstein, 2016): < Δ 0.010 in CFI and < Δ 0.015 in RMSEA for measurement invariance; df = degrees of freedom. All deltas (Δ) are absolute values.

Discussion

Self-objectification, a process which springs from sexual objectification (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), is an important construct for researchers and clinicians to measure, especially among understudied populations, such as TGNB adults. Using scores from 590 TGNB participants, we tested whether the two-factor structure of the SOBBS failed to be disconfirmed and determined whether factorial invariance was present for this population. Factor analytic results supported the internal structure of scores, yielded good estimates of internal consistency for each subscale, and failed to disconfirm the two-dimensional model reported in the original test construction study (Lindner & Tantleff-Dunn, 2017). Strong, strict, and structural invariance of scores were observed, indicating that the SOBBS reflects the construct of self-objectification similarly among binary transgender and nonbinary communities. Our findings provide insight into the validity and reliability of scores on the SOBBS in research with TGNB individuals and are important because few instruments have psychometric properties established with this population. Researchers now have a modern self-objectification instrument for use with TGNB adults to expand objectification research and to integrate self-objectification into other programs of research, such as investigating how self-objectification influences general psychological processes (e.g., development).

CFA results supported the two-factor structure of SOBBS scores in the total sample, thereby shedding light on the construct of self-objectification. Scores on both subscales failed to be disconfirmed, suggesting that internalizing an observer’s perspective and treating the body-as-self are theoretically important constructs to investigate with TGNB adults. As core factors in objectification theory (Lindner & Tantleff-Dunn, 2017), each subscale warrants additional exploration to advance our understanding of how self-objectification contributes to adverse consequences for this understudied population. Research with cisgender women has found robust evidence that self-objectification is widespread, has many sources (e.g., parents, media), and enflames health risk disparities (e.g., disordered eating, reduced flow; Daniels et al., 2020; Moradi & Huang, 2008), but it remains less clear how gender-diverse groups respond to and internalize sexual objectification.

While basic tenets of objectification theory are beginning to be confirmed among TGNB adults (e.g., Comiskey et al., 2020; Velez et al., 2016), most of these studies focus on body dissatisfaction, body shame, and body monitoring. Completing these investigations with a focus on self-objectification is important because the central tenet of objectification theory is that, within a culture that systemically objectifies the gendered body, an individual learns to see the body from a third-person perspective and value the body’s appearance over its agency (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Moradi, 2010). The present study extends the extant literature, as results supported the internal structure and internal consistency reliability of scores on the SOBBS for use with TGNB individuals. Future research might explore how androgynous body ideals shape self-objectification, investigate the development of self-objectification within the context of transphobic minority stress, or document the translation of self-objectification into body monitoring while distinguishing the process from gender dysphoria.

This study provided evidence for strong, strict, and structural measurement invariance of scores on the SOBBS across binary transgender and nonbinary groups. Since the latent factors did not differ significantly across gender groups, researchers are able to make valid comparisons of self-objectification between binary transgender and nonbinary participants. It is important to note that invariance was demonstrated via one study with a self-selected sample, so more research is necessary. Nonetheless, the present findings provide initial evidence of factorial invariance, which is an important advance in the study of gender differences because, while the research base on gender differences between cisgender men and women is robust, studies examining the differences between binary transgender and nonbinary people are noticeably scarce (Jones et al., 2019), especially in the area of objectification. Viewing the body-as-self may be gender affirming for some binary transgender adults (Flores et al., 2018; Sevelius, 2013) and androgynous body ideals may be a group-specific protective factor for some TGNB adults (Galupo et al., 2021) which, in turn, may reduce the adverse consequences of self-objectification if the observer’s perspective is rejected in favor of achieving authenticity. Of course, self-objectification also is associated with adverse outcomes (e.g., Daniels et al., 2020; Jones & Griffiths, 2015). Thus, given that self-objectification may function uniquely among TGNB adults, having a measure that enables group comparisons may delineate when and for whom self-objectification is problematic.

Presently, there are few studies examining differences in body-oriented clinical outcomes among TGNB adults even though certain outcomes, such as eating disorders, may be 2 to 4 times higher among this population (Gordon et al., 2021). Given that self-objectification is a driver of musculature concerns, body dissatisfaction, and maladaptive weight management behaviors (Filice et al., 2020; Noll & Fredrickson, 1998; Velez et al., 2016), results from this study enable future researchers to characterize the role of self-objectification as a potential mechanism explaining the disparities in objectification correlates.

Implications for Counseling Practice

Self-objectification and its dimensions (i.e., internalizing an observer’s perspective, treating the body-as-self) may be useful constructs to assess when working with TGNB clients who present with body dysmorphia, body shame, body surveillance, body image issues, and related clinical correlates (e.g., eating concerns; Brewster et al., 2019). While core tenets of self-objectification show up for TGNB clients, there are nuances that engender a unique experience of self-objectification among this population (Anzani et al., 2021; Brewster et al., 2019; Comiskey et al., 2020; Cusack & Galupo, 2021; Flores et al., 2018; Gamarel et al., 2020; McGuire et al., 2016; Velez et al., 2016). Elucidating these nuances with validated and reliable scores on measures, such as the SOBBS, may inform clinical interventions and increase multicultural competence. Specifically, understanding the process of internalizing an observer’s perspective could play a role in gender-affirming care. For example, with the additional research on self-objectification enabled by psychometric studies such as the present investigation, clinicians might help clients distinguish self-objectification from behaviors related to (a) achieving identity congruence or (b) seeking interpersonal safety by passing (i.e., attempting to be perceived as a cisgender man or woman by others). It could be beneficial for clinicians to explore the relationship between identity congruence and gender expression with regard to body surveillance and how internalizing an observer’s perspective can be adaptive for navigating cultural gender norms around behavior and appearance—especially for individuals who desire to pass as cisgender. When working with nonbinary individuals, clinicians could discuss the potential negative impacts that an internalized observer’s perspective has it relates to appearance congruence (i.e., the congruence between one’s gender identity and one’s gender expression). Nonbinary individuals may not want to pass as cisgender and, thus, internalizing an observer’s perspective might be maladaptive given that the observer’s perspective is largely tied to cultural norms around the gender binary and appearance. Clinicians could explicitly explore who this internalized observer is—what identities they hold and how they view the individual’s body and gender expression. Finally, given that self-objectification impairs flow and increases body shame (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), clinicians might consider reducing self-objectification with TGNB clients through mindfulness-based, compassion-focused interventions.

Importantly, there are reliability limitations to the SOBBS. For the SOBBS total score and each subscale, Cronbach’s coefficient alpha was below the .90 threshold for clinical decisions (Salkind, 2010) and the literature is lacking a clinical decision-making threshold for McDonald’s coefficient omega. Instead of making important clinical decisions with the SOBBS, clinicians might consider the SOBBS as a screener for self-objectification while forming theoretical conceptualizations of their TGNB clients.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite the strengths of this study (i.e., a large geographically diverse sample size, the use of common statistical methods to facilitate interpretation), several limitations warrant consideration while interpreting these results. Four limitations relate to the sample. First, this sample trended towards younger TGNB adults (i.e., majority under 30 years old) and mostly identified as non-Hispanic European American. Over 70% of the sample was assigned female at birth and over half earned less than $20,000 annually. Additionally, this sample had access to the internet and an interest in participating in survey research. Thus, these findings may not generalize to older, ethnically diverse TGNB adults who were assigned male at birth, have higher incomes, or lack internet access. Relatedly, data were collected via a non-probability sampling technique, which was drawn from a non-clinical population, so the SOBBS may not generalize across clinical status. Second, the sample did not include cisgender participants and factorial invariance of scores on the SOBBS was established for TGNB adults only. Future researchers might test measurement invariance among TGNB adults and cisgender men and women. Third, although we followed sample size recommendations for multigroup CFA (e.g., Kalkbrenner, 2021), a formal power analysis was not conducted, so estimates may be the result of low power. Lastly, the sample was predominantly bi/pansexual (n = 241) and differences in SOBBS scores among sexual orientation were not examined in this study. Given the sociocultural nature of self-objectification, including social and relational benefits such as passing as cisgender and desirability (Brewster et al., 2018; Comiskey et al., 2020; Tebbe et al., 2018), future research might also take into consideration the interaction between gender identity and sexual orientation or other demographic variables in SOBBS scores.

Although the results of the present study revealed strong support for the internal structure validity of scores on the SOBBS with a sample of TGNB adults, we did not examine other forms of validity evidence. Future investigators can extend this line of research on the psychometric properties of the SOBBS through testing criterion and convergent validity of TGNB adults’ scores. Criterion validity determines whether an instrument is useful in estimating a related non-test criterion measured simultaneously or in the future. Given that body-based clinical outcomes (e.g., restrictive eating, compulsive exercise; Comiskey et al., 2020; Velez et al., 2016) may encourage some TGNB adults to seek treatment, understanding the predictive utility of self-objectification warrants greater examination. Convergent validity is another type of validity evidence, which can extend construct validity by determining if scores on the SOBBS correlate with similar measures in the expected directions. For example, it would have been useful to examine body surveillance given that the construct is distinct from, but highly related to, self-objectification (Lindner & Tantleff-Dunn, 2017; Moradi & Huang, 2008). Future research should use an extensive set of measures to characterize the validity of scores on the SOBBS among TGNB adults more fully.

A final methodological limitation is related to the construction of the SOBBS. Even though an instrument works well among TGNB adults, this does not necessarily mean it is an ideal measure for this population (Cusack & Galupo, 2021). Although results indicated that the dimensions of the SOBBS were validated using TGNB adults’ scores, the present study might have benefitted from qualitative techniques to determine the ways in which items on the SOBBS might inadequately cover the domain of self-objectification for TGNB adults. Given that binary transgender individuals may experience body-specific gender dysphoria (Pulice-Farrow et al., 2020), for example, it is unclear how items such as “When I look in the mirror, I notice areas of my appearance that I think others will view critically” might be observed indicators of gender incongruence rather than internalizing an observer’s perspective. Similarly, in an American context in which rates of violence against TGNB adults remain alarmingly high (Human Rights Campaign, 2020), among binary transgender people for whom passing is motivated by safety concerns, items like “I consider how my body will look to others in the clothing I am wearing” may be indicators that overlap with community-specific interpersonal processes and dimensions of self-objectification. Future research could address these possible limitations of item content.

Conclusion

Collectively, our findings revealed evidence for the two-factor dimensionality, reliability, and measurement invariance of scores on the SOBBS between binary transgender and nonbinary adults. The findings suggested that the SOBBS adequately reflects the domains of internalizing an observer’s perspective and treating the body-as-self for TGNB adults. By using the SOBBS with TGNB adults to advance objectification research, professional counselors can use their findings to develop interventions aimed at reducing self-objectification and its deleterious correlates in this understudied population.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their constructive feedback. Cory Cascalheira is supported as a RISE Fellow by the National Institutes of Health (R25GM061222).

Funding

This project was supported by the Mamie Phipps Clark Diversity Research Grant, in the amount of $1,500, awarded by Psi Chi to Cory J. Cascalheira.

References

- Anzani A, Lindley L, Tognasso G, Galupo MP, & Prunas A (2021). “Being talked to like I was a sex toy, like being transgender was simply for the enjoyment of someone else”: Fetishization and sexualization of transgender and nonbinary individuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50, 897–911. 10.1007/s10508-021-01935-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster ME, Velez BL, Breslow AS, & Geiger EF (2019). Unpacking body image concerns and disordered eating for transgender women: The roles of sexual objectification and minority stress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(2), 131–142. 10.1037/cou0000333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calogero RM (2011). Operationalizing self-objectification: Assessment and related methodological issues. In Calogero RM, Tantleff-Dunn S, & Thompson JK (Eds.), Self-objectification in women: Causes, consequences, and counteractions. (pp. 23–49). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/12304-002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calogero RM, Tylka TL, Siegel JA, Pina A, & Roberts T-A (2020). Smile pretty and watch your back: Personal safety anxiety and vigilance in objectification theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 10.1037/pspi0000344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FF (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. 10.1080/10705510701301834 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski JF, & Yost MR (2013). Psychosocial influences on bisexual women’s body image: Negotiating gender and sexuality. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(2), 224–241. 10.1177/0361684311426126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comiskey A, Parent MC, & Tebbe EA (2020). An inhospitable world: Exploring a model of objectification theory with trans women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44(1), 105–116. 10.1177/0361684319889595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack CE, & Galupo MP (2021). Body checking behaviors and eating disorder pathology among nonbinary individuals with androgynous appearance ideals. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 26, 1915–1925. 10.1007/s40519-020-01040-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels EA, Zurbriggen EL, & Ward LM (2020). Becoming an object: A review of self-objectification in girls. Body Image, 33, 278–299. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov DM (2010). Testing for factorial invariance in the context of construct validation. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 43(2), 121–149. 10.1177/0748175610373459 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov DM (2012). Statistical methods for validation of assessment scale data in counseling and related fields. American Counseling Association. [Google Scholar]

- Filice E, Raffoul A, Meyer S, & Neiterman E (2020). The impact of social media on body image perceptions and bodily practices among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: A critical review of the literature and extension of theory. Sex Roles, 82. 10.1007/s11199-019-01063-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flores MJ, Watson LB, Allen LR, Ford M, Serpe CR, Choo PY, & Farrell M (2018). Transgender people of color’s experiences of sexual objectification: Locating sexual objectification within a matrix of domination. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(3), 308–323. 10.1037/cou0000279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, & Roberts T (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galupo MP, Cusack CE, & Morris ER (2021). “Having a non-normative body for me is about survival”: Androgynous body ideal among trans and nonbinary individuals. Body Image, 39, 68–76. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, Jadwin-Cakmak L, King WM, Lacombe-Duncan A, Trammell R, Reyes LA, Burks C, Rivera B, Arnold E, & Harper GW (2020). Stigma experienced by transgender women of color in their dating and romantic relationships: Implications for gender-based violence prevention programs. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–29. 10.1177/0886260520976186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AR, Moore LB, & Guss C (2021). Eating disorders among transgender and gender non-binary people. In Nagata JM, Brown TA, Murray SB, & Lavender JM (Eds.), Eating disorders in boys and men (pp. 265–281). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-030-67127-3_18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson ER, Blosnich JR, Herman JL, & Meyer IH (2019). Considerations on sampling in transgender health disparities research. LGBT Health, 6(6), 267–270. 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huellemann KL, & Calogero RM (2020). Self-compassion and body checking among women: The mediating role of stigmatizing self-perceptions. Mindfulness, 11(9), 2121–2130. 10.1007/s12671-020-01420-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Campaign. (2020). Violence against the transgender and gender non-conforming community in 2020. https://www.hrc.org/resources/violence-against-the-trans-and-gender-non-conforming-community-in-2020

- Jones BA, & Griffiths KM (2015). Self-objectification and depression: An integrative systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 171, 22–32. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BA, Pierre Bouman W, Haycraft E, & Arcelus J (2019). Mental health and quality of life in non-binary transgender adults: A case control study. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2–3), 251–262. 10.1080/15532739.2019.1630346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkbrenner MT (2021). Enhancing assessment literacy in professional counseling: A practical overview of factor analysis. The Professional Counselor, 11(3), 267–284. 10.15241/mtk.11.3.267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon E, & Mistler BJ (2014). Cisgenderism. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1(1–2), 63–64. 10.1215/23289252-2399623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner D, & Tantleff-Dunn S (2017). The development and psychometric evaluation of the Self-Objectification Beliefs and Behaviors Scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41(2), 254–272. 10.1177/0361684317692109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maheux AJ, Roberts SR, Evans R, Widman L, & Choukas-Bradley S (2021). Associations between adolescents’ pornography consumption and self-objectification, body comparison, and body shame. Body Image, 37, 89–93. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JK, Doty JL, Catalpa JM, & Ola C (2016). Body image in transgender young people: Findings from a qualitative, community based study. Body Image, 18, 96–107. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley NM, & Hyde JS (1996). The Objectified Body Consciousness Scale: Development and validation. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20(2), 181–215. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00467.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNeish D (2018). Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods, 23(3), 412–433. 10.1080/10705510701301834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade AW, & Kroustalis CM (2006). Problems with item parceling for confirmatory factor analytic tests of measurement invariance. Organizational Research Methods, 9(3), 369–403. 10.1177/1094428105283384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B (2010). Addressing gender and cultural diversity in body image: Objectification theory as a framework for integrating theories and grounding research. Sex Roles, 63, 138–148. 10.1007/s11199-010-9824-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, & Huang Y-P (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4), 377–398. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noll SM, & Fredrickson BL (1998). A mediational model linking self-objectification, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22(4), 623–636. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00181.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osa ML, & Calogero RM (2020). Orthorexic eating in women who are physically active in sport: A test of an objectification theory model. Body Image, 35, 154–160. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulice-Farrow L, Cusack M, & Galupo MP (2020). “Certain parts of my body don’t belong to me”: Trans individuals’ descriptions of body-specific gender dysphoria. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 17, 654–667. 10.1007/s13178-019-00423-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnick DL, & Bornstein MH (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. 10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkind N (2010). Encyclopedia of research design (Vol. 1–0). 10.4135/9781412961288.n53 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, & King J (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338. 10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelius JM (2013). Gender affirmation: A framework for conceptualizing risk behavior among transgender women of color. Sex Roles, 68, 675–689. 10.1007/s11199-012-0216-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebbe EA, Moradi B, Connelly K, Lenzen A, & Flores M (2018). “I don’t care about you as a person”: Sexual minority women objectified. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(1), 1–16. 10.1037/cou0000255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terán L, Jiao J, & Aubrey JS (2021). The relational burden of objectification: Exploring how past experiences of interpersonal sexual objectification are related to relationship competencies. Sex Roles, 84(9), 610–625. 10.1007/s11199-020-01188-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velez BL, Breslow AS, Brewster ME, Cox R Jr., & Foster AB (2016). Building a pantheoretical model of dehumanization with transgender men: Integrating objectification and minority stress theories. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(5), 497–508. 10.1037/cou0000136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall PH, & Henning KSS (2013). Texts in statistical science: Understanding advanced statistical methods. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]