Abstract

Ruthenium(II)-based coordination complexes have emerged as photosensitizers (PSs) for photodynamic therapy (PDT) in oncology as well as antimicrobial indications and have great potential. Their modular architectures that integrate multiple ligands can be exploited to tune cellular uptake and subcellular targeting, solubility, light absorption, and other photophysical properties. A wide range of Ru(II) containing compounds have been reported as PSs for PDT or as photochemotherapy (PCT) agents. Many studies employ a common scaffold that is subject to systematic variation in one or two ligands to elucidate the impact of these modifications on the photophysical and photobiological performance. Studies that probe the excited state energies and dynamics within these molecules are of fundamental interest and are used to design next-generation systems. However, a comparison of the PDT efficacy between Ru(II) containing PSs and 1st or 2nd generation PSs, already in clinical use or preclinical/clinical studies, is rare. Even comparisons between Ru(II) containing molecular structures are difficult, given the wide range of excitation wavelengths, power densities, and cell lines utilized. Despite this gap, PDT dose metrics quantifying a PS’s efficacy are available to perform qualitative comparisons. Such models are independent of excitation wavelength and are based on common outcome parameters, such as the photon density absorbed by the Ru(II) compound to cause 50% cell kill (LD50) based on the previously established threshold model.

In this focused photophysical review, we identified all published studies on Ru(II) containing PSs since 2005 that reported the required photophysical, light treatment, and in vitro outcome data to permit the application of the Photodynamic Threshold Model to quantify their potential efficacy. The resulting LD50 values range from less than 1013 to above 1020 [hν cm−3], indicating a wide range in PDT efficacy and required optical energy density for ultimate clinical translation.

INTRODUCTION

Considerable effort has been invested in developing Ru(II) containing photosensitizers (PSs) for phototherapy applications. However, only a handful have been tested in preclinical models, and of these, only one has advanced to human clinical trials [1–3]. The gap between fundamental studies of many new PSs and their translation is widened by the fact that the published reports often lack photophysical and efficacy details to enable quantitative comparison of these new PS to existing PSs. In this review, we propose a quantitative approach to compare the in vitro efficacies of PSs and highlight reporting improvements that could be implemented to facilitate better translational risk assessment by the pharmaceutical receptor industries.

Transition metal complexes have played an important historic role as medicinal agents[4], including in oncology[5–8], with cisplatin being arguably one of the more successful anticancer drugs. More recently, ruthenium coordination complexes have gained attention as potential chemotherapeutics with novel modes of action [9]. Four have been clinically investigated: three Ru(III) compounds that do not involve light activation (NAMI-A, KP1019, and IT-139)[10–12] and our own Ru(II) PDT agent (TLD1433)[1,2]. Of these, TLD1433 continues to advance and is in Phase 2 clinical studies, while IT-139 (also known as BOLD-100) has moved to a different Phase 1 study in combination with FOLFOX.

This article is focused on Ru(II) coordination complexes (Ru PSs) as anticancer agents, specifically for photodynamic therapy (PDT) in oncology. Based on our review of over 300 manuscripts and the therein reported information, we suggest best practices applicable in the reporting for light-responsive prodrugs in general and their phototherapeutic applications in particular. PDT and related branches of photomedicine are distinct from traditional chemotherapeutic approaches in that the light-molecule interaction effectively turns “on” the drug's activity. As such, the light parameters employed and their impact on PS activation are as crucial as the PS itself. The photophysical properties of the PS must be established and clearly reported so that the medical and laser physicists can determine the required photon density based on a tissue's responsivity to the anticipated cytotoxic load. Effective photoactivation across relevant tissue volumes will significantly influence clinical translation and must therefore be considered for novel PSs with regard to the specific oncological or other indication [13–15]. A necessary first step in assessing the potential of PSs (from the primary literature) for PDT is adopting a common approach for quantifying and reporting in vitro PDT efficacy.

Our longstanding interest in developing Ru PSs for PDT motivated us to systematically compare the in vitro efficacy of published compounds. To compare the PDT efficacy of a wide range of Ru PSs, the Photodynamic Threshold Model, developed in the early 1990th by Wilson, Patterson, and colleagues [16–19] initially for in vivo studies in the liver and brain, was employed. The threshold values are PS dependent and reflect the combined effect of PS accumulation within the target, subcellular PS localization to sensitive target structures, the quantum efficacy to generate cytotoxins, and the target’s ability to mitigate the induced cytotoxic stress. The threshold values can be experimentally established for various biological endpoints, such as induction of necrosis [17–19] or apoptosis [20]. The threshold values are given in units of [hν cm−3] and represent the number of photons absorbed by the PS per unit volume to cause a particular biological endpoint, here applied to the LD50 or the ED50 during in vitro studies.

Any attempt at formally comparing the PDT efficacy of different PSs using the threshold values must be based on a range of assumptions pertaining to the PS synthesis, quality, purification and storage, and the biological system preparation and evaluation. The subsequent analysis implicitly assumes that the reported Ru PS is 100% pure (which is likely not the case). No other cytotoxic fraction or impurities affecting light absorption or biological response are present. Additionally, the salt concentrations are also assumed to be minimized, thus not affecting the optical and biological co-localization and hence the survival data. While cell seeding density can affect the in vitro efficacy, the majority of the experiments were performed at high seeding density or cultures late in exponential growth. Hence, it is stipulated that the in vitro studies have been performed under optimal cell growth conditions. With these assumptions in mind, cell kill and, therefore, the reported LD50 or ED50 values are entirely attributed to the generation of cytotoxic entities following photon absorption.

METHOD

Search Strategy

A structured search was conducted between March 1st, 2020, and March 3rd, 2020; in Web of Science utilizing all databases covering the past 20 years and applying the search terms “Ruthenium,” “complex” “photosensitizer,” “PDT, or Photodynamic” and “in vitro” or “tissue culture.” The search was updated once on December 27th, 2020, and a second time on March 15th2021. Additional searches replacing “photochemotherapy, photoactivated chemotherapy or PACT” for “PDT” and “Photodynamic Compound” for “photosensitizer”’ were also performed.

Study Inclusion Criteria

Using the search terms stated above, 525 research publications were identified. Three hundred twenty-six research publications were identified after eliminating abstracts only, non-English publications, and those unavailable through the University of Toronto Library services. Only studies with the required photophysical and biological data were analyzed for their in vitro efficacy according to the threshold model

Data Extraction and Quantitative Synthesis to Extract Threshold Values

A wavelength-independent measure is needed to compare the quantum efficacy of different PSs. This is accomplished using the photodynamic threshold dose (DosePDT as defined in Eq 1). For single-wavelength PDT, the photodynamic threshold dose is determined by the radiant exposure, H [J cm−2], converted to [hν cm−2]; the concentration of PS to achieve 50% cell kill, [PS]LD50, in [μM]; and the molar extinction coefficient as a function of wavelength, ε(λ) [μM−1 cm−1], according to Eq. 1a and 1b when ε(λ) is derived based on absorbance

| (Eq 1a) |

| (Eq 1b) |

Conversion of H [J cm−2] to H [photon cm−2] is given by Eq. 2, whereby the energy units are photon energy in eV, h is Planck’s constant, and c the speed of light in a vacuum.

| (Eq 2) |

Hence the PDT threshold dose in units of photons absorbed by the photosensitizer per unit volume for 50% in vitro cell kill is given according to equation 1a, b by

| (Eq 3a) |

| (Eq 3b) |

with units of [photon cm−3]. In equation 3 it is assumed that the reported absorbance or optical density in spectra is given as log base 10. A low threshold value indicates a high quantum efficacy for inducing cell death by a Ru PS. Low threshold values can be achieved by a high singlet oxygen (1O2) quantum yield and/or the generation of reactive oxygen species at sensitive cellular targets. PSs with low threshold values are preferable for translation as a good photodynamic effect can be achieved at low PS concentration and/or low radiant exposure. Administration of low PS doses reduces the likelihood of nonspecific toxicity effects, and low radiant exposure or fluences reduce the time needed for light delivery. The latter is of particular interest if the photosensitizer remain active even at high irradiances or fluence rates [mW cm−2]

For this assessment, we looked for the following information in the articles or supplementary information either in the text, tables, or figures: (i) the LD50 or ED50 as a function of PS concentration or radiant exposure, whereby radiant exposure could be substituted by irradiance [mW cm−2] and exposure time [sec], and (ii) the molar extinction coefficient, stated either as a value or more commonly by an absorption spectrum given in OD or transmittance [%] across the PDT activation wavelength obtained for a known Ru PS concentration and cuvette pathlength. As these parameters are reported in various ways, the relevant data were extracted. In cases when survival was limited, not allowing to calculate the LD50, but the ED50, giving the half-maximal response, was available, was used in calculating the PDT threshold value. For cases when the absorption data was represented in graphical form, the free web tool developed by A. Rohatgil (https://apps.automeris.io/wpd/) was used to extract the numerical data for the corresponding absorption spectra. Molar extinction coefficients, ε(λ), were then calculated by Eq 4.

| (Eq 4) |

A(λ) represents the measured optical density (unitless), and l is the path length of the cuvette, set to 1 cm unless otherwise noted. Absorption spectra were reported in various organic and aqueous solvents and rarely in incomplete or complete media. Thus, values for ε(λ) are not representative of the cellular environment, altering the optical properties [21]. Even for cases where ε(λ) is given for media, it does not precisely recapitulate the microenvironment(s) in cells or the ε(λ) if binding to proteins, transporters, or the DNA occurs.

For manuscripts reporting PS activation with both broadband and monochromatic light [22], only the monochrome data was utilized to achieve a more reliable calculation of the threshold values. The following procedure was implemented in the cases where only broadband light sources were used. LEDs were considered monochromatic if the full-width half max (FWHM) was less than 40 nm. For LEDs with larger FWHM or broadband light sources (e.g., halogen lamps, quartz lamps, solar simulators, and other sources), the light source model and electrical power needed to be reported to allow for an independent search of the wavelength-dependent light emission of these emitters. Emission spectra, Iraw(λ), for the output from tungsten-, halogen-lamps, or solar simulators were obtained from the identified manufacturers as available. Wavelength restrictions due to listed cut-on or cut-off filters were considered a step function in the emission profile, as the make and model of optical filters are generally not reported. The wavelength restricted emission spectra were normalized and multiplied by the reported radiant exposure, H [J cm−2], and converted to [hν cm−2 nm−1] by applying Eq. 2. The result is a wavelength resolved, absolute emission spectrum Ihv(λ). Ihv(λ) was then convolved with ε (λ) and integrated over the relevant wavelength range, as shown in Eq 5.

| (Eq 5) |

The supplementary information provides an example spreadsheet to execute this calculation with detailed annotations.

To test the reproducibility of the value as the basis for an efficacy comparison, studies from different research groups using the same PS in similar cell lines were identified. The two PSs used in this comparison are 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA)-induced protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) and TLD1433. Additional information extracted from the manuscripts pertains to the cell lines used for in vitro studies and 1O2 quantum yields if reported.

It was shown that Ru(II) coordination complexes demonstrate a high affinity to nitrogen and sulfur donors, as present in serum albumin and transferrin (Tf), thus exploiting efficient transport mechanisms in mammalian cell-based systems. The exploitation of the apo-Tf [8,23] is of interest as its receptor is increased several folds in malignant cells over normal host cells, increasing the drug’s selectivity towards malignancies [24]. To determine if the transferrin receptor (TfR or CD71) expression of the different cell lines affected the calculated , the cell lines were ranked based on the mean TfR reporter fluorescence index (MFI) from flow cytometric data [23,25] or western blot data on other known cell lines [25,26]. Fluorescein-labeled Tf or nanoparticle uptake levels were used to classify cell lines for TfR expression [23,27]. TfR expression ranking was completed before determining the threshold values to avoid subjective bias. Testing of the distributions in high versus low TfR expressing cell lines can shed light on the importance of Tf as a Ru PS transporter leading to improved PDT efficacy.

RESULTS

Of the 326 studies evaluated, 103 did not report in vitro efficacy. The remaining 222 studies supplied some form of in vitro cell survival data. Of these, only 41 studies could be included in this comparative efficacy analysis for Ru PSs since they were the only ones that provided all the required information related to the irradiation parameters and relevant ε(λ), both in absolute values either in the text or the supplementary documentation, to calculate the .

The majority of the 183 studies not considered in the efficacy analysis failed to supply absolute ε(λ) data or only relative absorbance data, at the PDT irradiation wavelength(s), either in text, table, or graphical form. Absorption spectra were labeled either in arbitrary absorption units or normalized; a common practice for compound comparisons or the PS concentration used for the absorption spectrum was not provided. A smaller number of publications failed to provide sufficient information related to the light source or, more often, irradiance or radiant exposure. The final 39 studies reported on 136 different Ru PSs and 13 nanoparticles (NPs), whereby the NP PSs were sometimes related to other reported Ru PSs. A total of 353 values were calculated for the various reported Ru PSs, representing PDT treatment condition variations including multiple cell lines, drug-to-light intervals (DLIs), radiant exposures, or Ru PS stock solvents used to determine, ε. For 66 of these conditions, only minimum values could be calculated as the dynamic range of the survival assays did not reach at least 50% cell kill, thus relying on the ED50. Only 9 out of the 136 reported studies were based on or contained established PSs; in particular, Foscan [28,29], hematoporphyrin [30] and phthalocyanine (Pc) [31,32].

The reproducibility of the as a quantitative value for an efficacy comparison was tested using ALA-induced PpIX [33,34] (Table 1A) and TLD1433 [15,21,35–37] (Table 1B). It is worth pointing out that the ε(660nm) of TLD1433 is less than 100 M−1 cm−1. Nevertheless, the red light is only 1–2 orders of magnitude higher than the green light used clinically, despite a much higher ε(525 nm), indicating an efficient energy transfer to maintain the high 1O2 quantum yield.

Table 1A.

Derived values for ALA-induced PpIX mediated PDT.

| Cell Line | λ [nm] |

LD50 [μM] ALA |

[hν cm−3] |

Ref | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa | 450 | 2.8 | 1.9 1016 | [38] |

|

| RPE-1 | 450 | 4.2 | 2.9 1016 | ||

| HeLa | 480 | 2.5 | 8.5 1015 | ||

| RPE-1 | 480 | 3.8 | 1.3 1016 | ||

| HeLa | 510 | 2.1 | 4. 6 1016 | ||

| RPE-1 | 510 | 3.1 | 6.7 1016 | ||

| HeLa | 540 | 2.1 | 7.8 1016 | ||

| RPE-1 | 540 | 3.3 | 1.2 1017 | ||

| HeLa | 600–700 | 3.1 | 1.2 1017 | [33] | |

| SiHa | 600–700 | 6.25 | 2.4 1017 | ||

| MDA-MB-23 1 | 600–700 | 3.5 | 1.3 10 17 | ||

| 2780AD | 600–700 | 4.8 | 1.8 1017 | ||

| A2780–9S | 600–700 | 3.5 | 1.3 1017 |

Table 1B.

Derived values for TLD1433 mediated PDT

| Cell LIne | λ [nm] |

LD50 [μM] |

[hν cm−3] |

Ref | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SKMEL28 | 625 | 2.29 | 8.7 1016 | [39] |

|

| HL-60 | 625 | 7.7 | 2.9 10 17 | ||

| CT26 | 525 | 0.021 | 9.8 1015 | [36] | |

| CT26.CL25 | 525 | 0.011 | 5.2 1015 | ||

| U87 | 525 | 0.051 | 2.4 1016 | ||

| F98 | 525 ± 25 | 2.81 | 1.3 1017 | ||

| T24 | 525 ± 25 | 0.0077 | 1.5 1015 | [3] | |

| AY27 | 525 ± 25 | 0.0039 | 7.7 1014 | ||

| AY27 | 625 | 9.9 | 3.4 1017 | [21] | |

| AY27 | 625a | 6.5 | 2.2 1017 | ||

| AY27 | 625a | 6.3 | 2.1 1017 | ||

| A549 | 532 | 0.099 | 1.6 1016 | [15] | |

| RG-2 | 530 | 0.0265 | 2.4 1016 | [35] |

Addition of 0, 5, and 10 μM apo-Tf prior to in vitro administration.

Table 2 presents the values under all of the treatment conditions that could be evaluated and the cell lines on which the studies were performed. Table 2 also lists the activation wavelengths and reported LD50 values for PpIX and TLD1433 from these studies. In some reports, cell kill was less than 50%, and the LD50 was not reached and hence the utilized are underestimated. Thus, the reported represent a minimum for these Ru PS and treatment conditions. To help the reader in identifying these underestimated numbers, the reported values are provided in red.

Table 2.

Summary of evaluated Ru PS, the cell lines employed, and the derived for in vitro PDT

| Ref | Identifier | Structural class | cell line | Cancer type | TfR Expression | λ[nm] | Threshold [hv cm−3] | Structure examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 42–44] | [Ru2(CO)4(OOCR1-H2)2(NC5H5)2] | Porphyrin derivatives complexes with pyridine | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 652 | 3.8E+20 |

|

| A549 | Lung | ++++ | 3.4E+20 | |||||

| Me300 | Melanoma | ?? | 1.1E+20 | |||||

| A2780 | Ovarian | + | 3.4E+20 | |||||

| [Ru2(CO)4(OOCR1-Zn)2(NC5H5)2] | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 8.3E+19 | ||||

| A549 | Lung | ++++ | 1.0E+20 | |||||

| Me300 | Melanoma | ?? | 4.3E+19 | |||||

| A2780 | Ovarian | + | 6.3E+19 | |||||

| [{Ru2(CO)4(NC5H5)2}2(OOCR2-H2COO)2] | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 3.8E+20 | ||||

| A549 | Lung | ++++ | 2.3E+20 | |||||

| Me300 | Melanoma | ?? | 9.6E+19 | |||||

| A2780 | Ovarian | + | 3.9E+20 | |||||

| [{Ru2(CO)4(NC5H5)2}2(OOCR2-ZnCOO)2] | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 3.9E+20 | ||||

| A549 | Lung | ++++ | 2.7E+20 | |||||

| Me300 | Melanoma | ?? | 7.3E+19 | |||||

| A2780 | Ovarian | + | 3.8E+20 | |||||

| [Ru2(CO)4(OOCR1-Zn)2(PPh3)2] | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 3.1E+20 | ||||

| A549 | Lung | ++++ | 2.6E+20 | |||||

| Me300 | Melanoma | ?? | 8.1E+19 | |||||

| A2780 | Ovarian | + | 1.5E+20 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 45] | RuL1 RuL2 RuL3 RuL4 |

Ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 450 | 8.7E+18 1.0E+19 1.1E+19 2.7E+18 |

|

|

| ||||||||

| [23, 41] | 1 | Ruthenium (II)-bicalutamide prodrugs | LNCaP | Prostate | ++++ | 465 660 465 660 465 660 |

4.2E+16 9.6E+17 6.6E+16 4.8E+17 1.2E+17 2.5E+17 |

|

| 2 | ||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [26, 46] | [Ru(Pc)] | Ruthenium phthalocyanine complexes | A375 | Melanoma | +++++ | 660@1Jcm−2 | 5.9E+16 |

|

| 660@2Jcm−2 | 1.7E+17 | |||||||

| 660@3Jcm−2 | 2.4E+17 | |||||||

| trans-[Ru(NO)(NO2)(Pc) | 660@1Jcm−2 | 7.4E+16 | ||||||

| 660@2Jcm−2 | 7.7E+16 | |||||||

| 660@3Jcm−2 | 1.0E+17 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 34, 47] | [Ru(terpy)(terpy- NMe2)]2+ | ruthenium terpyridine complexes | RPE-1 | Eye | ++ | 480 | 4.2E+18 |

|

| HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 3.7E+18 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| [38, 47] | Ru(II) polypyridine complex 3 | (2,2′-bpy-4,4′-dicarboxaldehyde)bis (1,10-phen) ruthenium(II) hexafluorophosphate |

HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 450 | 1.7E+19 |

|

| RPE-1 | Eye | ++ | 450 | 2.0E+19 | ||||

| HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 480 | 5.3E+18 | ||||

| RPE-1 | Eye | ++ | 480 | 6.3E+18 | ||||

| HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 510 | 3.1E+18 | ||||

| RPE-1 | Eye | ++ | 510 | 3.1E+18 | ||||

| HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 540 | 2.5E+18 | ||||

| RPE-1 | Eye | ++ | 540 | 2.5E+18 | ||||

| Ru(II) polypyridine complex 4 | (4,4′-Bis(N-Benzylimine)-2,2′-bpy)bis(1,10-phen)ruthenium(II) hexafluorophosphate | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 450 | 3.1E+18 | ||

| RPE-1 | Eye | ++ | 450 | 4.0E+18 | ||||

| HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 480 | 2.7E+17 | ||||

| RPE-1 | Eye | ++ | 480 | 4.0E+17 | ||||

| HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 510 | 1.6E+17 | ||||

| RPE-1 | Eye | ++ | 510 | 2.3E+17 | ||||

| HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 540 | 1.6E+17 | ||||

| RPE-1 | Eye | ++ | 540 | 1.9E+17 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 30, 83] | NPs-1 @ 4h | D,L-lactide, L-lactide and D-lactide linked to Ru(ipy)2-dppz-7-hydroxymethyl][PF6]2 | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 480 | 8.3E+18 |

|

| @ 24h | 5.6E+18 | |||||||

| @ 48h | 3.8E+18 | |||||||

| NPs-2 @ 4h | 1.0E+19 | |||||||

| @ 24h | 4.3E+18 | |||||||

| @ 48h | 7.0E+18 | |||||||

| NPs-3 @ 4h | 1.2E+19 | |||||||

| @ 24h | 2.8E+18 | |||||||

| @ 48h | 2.5E+18 | |||||||

| NPs-4 @ 4h | 5.0E+18 | |||||||

| @ 24h | 2.3E+18 | |||||||

| @ 48h | 1.3E+18 | |||||||

| (RuOH) - @ 4h | Ru(bpy)2-dppz-7-hydroxymethyl][PF6]2 | 3.5E+19 | ||||||

| @ 24h | 1.9E+19 | |||||||

| @ 48h | 6.9E+18 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 30, 44] | 1 | Ru8(η6-C6H5Me)8(tpp-H2)2(dhbq)4]8+ | HeLa A549 HeLa A549 |

Cervical Lung Cervical Lung |

+++++ ++++ +++++ ++++ |

652 | 6.9E+16 2.4E+17 5.9E+16 1.1E+17 |

|

| 2 | Ru8(η6-p-iPrC6H4Me) 8(tpp-H2)2(dhbq)4]8+ | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 48, 49] | (4) | [Ru(phen)2[2,3-h]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine]2 | HeLa CRL 5915 One58 Mutu-1 DG-75 |

Cervical Mesothelioma Mesothelioma Lymphoma Lymphoma |

+++++ ?? ?? ?? +++++ |

HgXe Lamp with sodium nitrite filter | 6.4E+19 5.9E+19 4.0E+19 6.4E+19 5.8E+19 |

|

| (5) | HeLa CRL 5915 One58 Mutu-1 DG-75 |

Cervical Mesothelioma Mesothelioma Lymphoma Lymphoma |

+++++ ?? ?? ?? +++++ |

5.9E+18 2.9E+19 2.6E+19 1.2E+19 2.9E+19 |

||||

| Ru(TAP)2pdppz]2+(pdppz = [2,3-h]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [50] | (Ph2phen)2RuCl2 | Ru-Polyazine Complex | F98 rat glioma | Glioma | ?? | 470 | 3.3E+19 |

|

| 625 | 3.2E+17 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [26, 51] | 1a | [Ru(phen)2(6-MP)]PF6 | MCF-7 | Mammary | +++++ | 465 | 1.3E+19 |

|

| 1b | 2.0E+19 | |||||||

| 1c | 8.0E+17 | |||||||

| 2 | [Ru(phen)2(PPh3)6-MP]PF6 | 1.7E+18 | ||||||

| 3 | 6.5E+17 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 44, 52–54] | 1 | [Ru(2,2′-bpy)2

(2,9-diphenyl- 1,10-phen)]-Cl2 |

A549 | Lung | ++++ | 460 | 1.6E+19 |

|

| B16 | Melanoma | ?? | 5.1E+18 | |||||

| Caco-2 | Colorectal | +++ | 9.3E+18 | |||||

| HT-29 | Colorectal | +++++ | 1.2E+19 | |||||

| MB-231 | Mammary | ++++ | 6.3E+18 | |||||

| 2 | A549 | Lung | ++++ | 6.3E+20 | ||||

| [Ru(2,2′-bpy)2(1,10-phen)]Cl2 | B16 | Melanoma | ?? | 6.3E+20 | ||||

| Caco-2 | Colorectal | +++ | 6.3E+20 | |||||

| HT-29 | Colorectal | +++++ | 6.3E+20 | |||||

| MB-231 | Mammary | ++++ | 6.3E+20 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| [25, 55] | Ru-BP | [Ru(bipy)2(dpphen)]- Cl2 |

K562 | Leukemia | ++++ | 632 | 2.3E+18 | See Figure 1A |

|

| ||||||||

| [56, 57] | 1 | Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes | SK-MEL-28 | Melanoma | ++? | 453 | 4.2E+19 |

|

| 2 | 9.9E+18 | |||||||

| 3 | 2.6E+19 | |||||||

| 4 | 7.5E+18 | |||||||

| 5 | 9.3E+19 | |||||||

| 6 | 6.7E+18 | |||||||

| 7 | 1.5E+18 | |||||||

| 1 | Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes | SK-MEL-28 | Melanoma | ++? | 523 | 1.3E+19 | ||

| 2 | 1.0E+19 | |||||||

| 3 | 1.4E+19 | |||||||

| 4 | 1.1E+19 | |||||||

| 5 | 1.4E+19 | |||||||

| 6 | 1.5E+18 | |||||||

| 7 | 1.1E+18 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 44, 58] | 1 | heterometallic Ru–Pt

metallacycle with Ru(II) ppy and tetramethylammonium-decorated Pt(II) |

A549 | Lung | ++++ | 450 | 2.7E+17 | See Figure 1B |

| A549R | ++++ | 4.6E+17 | ||||||

| HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 1.3E+18 | |||||

| KV | Oral | ?? | 2.4E+18 | |||||

| PC-3 | Prostate | ?? | 1.7E+18 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| [25, 56, 59] | 1 | [Ru 3,8-di (BTF)-1,10-phen (2,2-py)2](PF6)2 | SK MEL28 | Melanoma | ++? | 625 | 8.0E+18 |

|

| 2 | [Ru 3,8-di (BTF)-1,10-phen (1,10-phen)2](PF6)2 | 5.8E+18 | ||||||

| 3 | [Ru 3,8-di (BTF)-1,10-phen (1,4,8,9 tatp)2](PF6)2 | 1.4E+18 | ||||||

| 4 | [Ru 3,8-di (BTF)-1,10-phen (dppz)2](PF6)2 | 1.5E+18 | ||||||

| 5 | [Ru 3,8-di (BTF)-1,10-phen (dppn)2](PF6)2 | 9.5E+17 | ||||||

| 1 | HL60 | Leukemia | + | 8.8E+18 | ||||

| 2 | 8.6E+18 | |||||||

| 3 | 2.8E+18 | |||||||

| 4 | 4.0E+18 | |||||||

| 5 | 1.2E+19 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [25, 56, 60] | 4a | 2-Thionoester Pyrrolide Ru(II) Complexes | HL60 | Leukemia | + | 625 | 1.6E+17 |

|

| 4b | 6.5E+16 | |||||||

| 4c | 1.6E+17 | |||||||

| 4h | 4.6E+16 | |||||||

| 4j | 9.6E+16 | |||||||

| 4k | 2.3E+16 | |||||||

| 4a | SK MEL28 | Melanoma | ++? | 3.1E+16 | ||||

| 4b | 1.6E+16 | |||||||

| 4c | 6.3E+16 | |||||||

| 4h | 1.8E+16 | |||||||

| 4j | 9.5E+16 | |||||||

| 4k | 1.7E+16 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [44, 61] | 1 | Boron-Dipyrromethene and Biotin Ruthenium(II) Conjugates | A549 | Lung | ++++ | 400–700 | 1.0E+16 |

|

| 2 | 5.0E+14 | |||||||

| 3 | 4.1E+16 | |||||||

| 4 | 9.2E+12 | |||||||

| 5 | 6.8E+13 | |||||||

| 1 | HPL1D | Lung | ?? | 1.0E+16 | ||||

| 2 | 2.3E+15 | |||||||

| 3 | 1.6E+17 | |||||||

| 4 | 3.0E+13 | |||||||

| 5 | 3.0E+14 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [25, 52, 56] | TLD 1433 | [Ru(dmb)2(IP-TT)]2+ | skmel28 HL-60 |

Melanoma Leukemia |

++? + |

625 |

8.6E+16 2.9E+17 |

|

| TLD1633 | [Os(dmb)2(IP-TT)]2+ | skmel28 | Melanoma | ++? | 1.6E+17 | |||

| RU CL | skmel28 HL-60 |

Melanoma Leukemia |

++? + |

1.4E+17 1.2E+17 |

||||

|

| ||||||||

| [26, 44, 63–65] | 1 | [Ru(tpy)(dmb)( thioetherL)]2+ | A549 A431 MCF-7 MRC-5 |

Lung | ++++ | 628 | 2.2E+17 |

|

| Epidermoid | ++++ | 1.5E+17 | ||||||

| Mammary | +++++ | 3.1E+17 | ||||||

| Fibroblast | + | 6.4E+17 | ||||||

| 2 |

A549 A431 MCF-7 MRC-5 |

Lung Epidermoid Mammary Fibroblast |

++++ ++++ +++++ + |

8.1E+17 9.4E+17 8.1E+17 1.8E+18 |

||||

| [Ru(tpy)(biq)-( py)]2+ | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 47, 66] | Ru | [Ru(4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phen)2(4,4’-dmb-2,2’-bpy)]2+ | HeLa RPE-1 |

Cervical Eye |

+++++ ++ |

480 | 1.6E+15 7.9E+14 |

See Figure 1C |

| Ru-Pt | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 3.0E+14 | ||||

| RPE-1 | Eye | ++ | 5.9E+14 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 64, 67] | Ru-L | [(bpy)2-Ru]2+ | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | >500 | 1.6E+14 | See Figure 1D |

| MRC-5 | Fibroblast | + | 1.6E+14 | |||||

| CHL-RuL | CHL=Chlorambucil | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 8.1E+13 | |||

| MRC-5 | Fibroblast | + | 1.1E+14 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| [68] | [2]Cl4 | [{Ru(TAP2)}2(tpphz)]4+ | C8161 | Melanoma | ?? | 420 | 8.9E+19 |

|

|

| ||||||||

| [23, 27, 69] | 1 | [Ru(dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 470 | 4.6E+18 |

|

| 2 | [Ru(F-dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | 5.5E+18 | ||||||

| 3 | [Ru(F2-dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | 1.4E+18 | ||||||

| 4 | [Ru(CF3-dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | 4.5E+18 | ||||||

| 1 | [Ru(dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | SKOV3 | Ovarian | +++++ | 470 | 2.6E+18 | ||

| 2 | [Ru(F-dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | 1.6E+18 | ||||||

| 3 | [Ru(F2-dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | 1.4E+18 | ||||||

| 4 | [Ru(CF3-dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | 2.2E+18 | ||||||

| 1 | [Ru(dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | L-02 | Haptocyte | ?? | 470 | 5.9E+18 | ||

| 2 | [Ru(F-dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | 3.8E+18 | ||||||

| 3 | [Ru(F2-dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | 5.4E+18 | ||||||

| 4 | [Ru(CF3-dppz)(py)4]Cl2 | 5.2E+18 | ||||||

| [Ru(tpy)(N-N)(Cl)]Cl |

|

|||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [26, 44, 70] | [1 a]Cl | N-N = bpy | A549 | Lung | ++++ | 454 | 3.4E+18 | |

| [2 a]Cl | N-N = phen | 4.8E+18 | ||||||

| [3 a]Cl | N-N = dpq | 4.8E+18 | ||||||

| [4 a]Cl | N-N = dppz | 1.9E+18 | ||||||

| [5 a]Cl | N-N = dppn | 6.0E+17 | ||||||

| [6 a]Cl | N-N = pmip | 1.2E+18 | ||||||

| [7 a]Cl | N-N = pymi | 2.5E+18 | ||||||

| [8 a]Cl | N-N = azpy | 2.9E+18 | ||||||

| [Ru(tpy)(N-N)(R)](PF6)2 | ||||||||

| [1 b](PF6)2 | N-N = bpy | 5.1E+18 | ||||||

| [2 b](PF6)2 | N-N = phen | 4.5E+18 | ||||||

| [3 b](PF6)2 | N-N = dpq | 6.5E+18 | ||||||

| [4 b](PF6)2 | N-N = dppz | 2.5E+18 | ||||||

| [5 b](PF6)2 | N-N = dppn | 6.0E+16 | ||||||

| [6 b](PF6)2 | N-N = pmip | 7.6E+18 | ||||||

| [7 b](PF6)2 | N-N = pymi | 8.6E+18 | ||||||

| [8 b](PF6)2 | N-N = azpy | 2.0E+18 | ||||||

| [1 a]Cl | MCF-7 | Mammary | +++++ | 454 | 3.4E+18 | |||

| [2 a]Cl | 2.5E+18 | |||||||

| [3 a]Cl | 4.8E+18 | |||||||

| [4 a]Cl | 1.3E+18 | |||||||

| [5 a]Cl | 2.0E+17 | |||||||

| [6 a]Cl | 1.2E+18 | |||||||

| [7 a]Cl | 2.5E+18 | |||||||

| [8 a]Cl | 2.9E+18 | |||||||

| [1 b](PF6)2 | 5.1E+18 | |||||||

| [2 b](PF6)2 | 4.5E+18 | |||||||

| [3 b](PF6)2 | 6.5E+18 | |||||||

| [4 b](PF6)2 | 1.9E+18 | |||||||

| [5 b](PF6)2 | 7.2E+16 | |||||||

| [6 b](PF6)2 | 7.6E+18 | |||||||

| [7 b](PF6)2 | 8.6E+18 | |||||||

| [8 b](PF6)2 | 2.0E+18 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 71] | 1 2 3 4 5 |

[Ru(bpy)2dppz]2+ | HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 420 | 8.9E+17 2.3E+18 2.3E+19 5.0E+19 6.6E+19 |

|

|

| ||||||||

| [26, 37, 65] | TLD1433 | [Ru(dmb)2(IP-TT)]2+ | CRMM1 CRMM2 CM2005.1 OMM1 OMM2.5 MEL270 A431 A375 |

Eye Eye Eye Eye Eye Melanoma Melanoma Melanoma |

?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ++++ +++++ |

520 | 1.4E+15 1.2E+15 1.4E+15 3.4E+15 3.1E+15 2.4E+15 1.2E+16 1.2E+16 |

|

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 47, 72, 73] | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

[Ru(phen)2(bpy)]2+ -Me2 -Br2 -Acetamide2 [Ru(dpphen)2(bpy)]2+-Me2 |

CT-26 | Colorectal | ?? | 480 | 4.3E+18 4.1E+18 6.6E+18 7.4E+18 8.2E+18 2.8E+16 1.5E+18 |

|

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

[Ru(phen)2(bpy)]2+ -Me2 -Br2 -Acetamide2 [Ru(dpphen)2(bpy)]2+-Me2 |

U87 | Glial | +++++ | 480 | 4.0E+18 3.2E+18 7.8E+18 1.0E+19 1.6E+19 9.8E+16 1.8E+18 |

||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

[Ru(phen)2(bpy)]2+ -Me2 -Br2 -Acetamide2 [Ru(dpphen)2(bpy)]2+-Me2 |

U373 | Glial | +++++ | 480 | 4.3E+18 4.5E+18 7.8E+18 1.0E+19 1.6E+19 2.8E+17 3.3E+18 |

||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

[Ru(phen)2(bpy)]2+ -Me2 -Br2 -Acetamide2 [Ru(dpphen)2(bpy)]2+-Me2 |

HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 480 | 4.3E+18 4.5E+18 7.8E+18 1.0E+19 1.6E+19 8.9E+16 3.4E+18 |

||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

[Ru(phen)2(bpy)]2+ -Me2 -Br2 -Acetamide2 [Ru(dpphen)2(bpy)]2+-Me2 |

RPE-1 | Eye | ++ | 480 | 4.3E+18 4.5E+18 7.8E+18 1.0E+19 1.6E+19 1.2E+17 2.0E+18 |

||

|

| ||||||||

| [23, 44, 74] | Ru0 Ru-PEG Ru-PEG-BP |

[Ru(dpphen)2(py-SO3)]+ | A549 | Lung | ++++ | 470 | 4.7E+18 4.4E+18 2.4E+18 |

|

| Ru0 Ru-PEG Ru-PEG-BP |

SKOV-3 | Ovarian | +++++ | 470 | 2.2E+18 1.9E+18 2.0E+18 |

|||

| Ru0 Ru-PEG Ru-PEG-BP |

Cis-A549 | Lung | ++++/?? | 470 | 4.1E+18 1.8E+18 2.1E+18 |

|||

|

| ||||||||

| [25, 56, 75] | 1 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-1T)PF6 | SK-MEL-28 | Melanoma | ++? | 625 | 1.1E+16 |

|

| 2 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-2T)PF6 | 1.1E+17 | ||||||

| 3 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-3T)PF6 | 1.9E+16 | ||||||

| 1 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-1T)PF6 | HL60 | Leukemia | + | 625 | 2.1E+15 | ||

| 2 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-2T)PF6 | 1.6E+17 | ||||||

| 3 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-3T)PF6 | 1.7E+16 | ||||||

| 1 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-1T)PF6 | SK-MEL-28 | Melanoma | ++? | 400–700 | 7.0E+17 | ||

| 2 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-2T)PF6 | 1.8E+18 | ||||||

| 3 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-3T)PF6 | 2.2E+17 | ||||||

| 1 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-1T)PF6 | HL60 | Leukemia | + | 400–700 | 3.6E+18 | ||

| 2 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-2T)PF6 | 5.7E+16 | ||||||

| 3 | Ru(bpy)2(phen-3T)PF6 | 1.2E+17 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [44, 76] | Ru1 Ru1@CD |

Ru((1-(2-pyridyl)-β-carboline))2(phen-COOH)]Cl2 | A549 | Lung | ++++ | 450 | 5.8E+19 4.9E+19 |

|

| Ru1 Ru1@CD |

LO2 | Hepatocyte | ?? | 450 | 8.2E+19 5.8E+19 |

|||

|

| ||||||||

| [23, 27, 44, 64, 77] | Ru1 | A549 | Lung | ++++ ++++ |

465 633 |

2.1E+18 |

|

|

| 5.9E+18 | ||||||||

| Hep-G2 | Liver | ++++ ++++ |

465 633 |

3.9E+18 | ||||

| 5.8E+18 | ||||||||

| HeLa | Cervical | +++++ +++++ |

465 633 |

2.0E+18 | ||||

| 5.4E+18 | ||||||||

| MRC-5 | Fibroblast | + + |

465 633 |

1.8E+19 6.5E+18 |

||||

|

| ||||||||

| [22, 25] | 5a | [Ru(X)(bpy)2]PF6 X= Styryl-1H-Pyr-c | HL60 | Leukemia | + | 625 | 7.9E+15 |

|

| 5b | X= Phenylene -(Pyr-c) | 4.1E+16 | ||||||

| 5c | X=Biphenyl- (Pyr-c) | 2.4E+16 | ||||||

| 5d | X=Naphthalene-(Pyr-c) | 2.5E+16 | ||||||

| 5e | X= Benzo-thiadiazole-(Pyr-c) | 2.2E+16 | ||||||

| 5f | X= Anthracene-(Pyr-c) | 4.5E+18 | ||||||

| 5g | X=Fluorene-(Pyr-c) | 1.7E+16 | ||||||

| 5h | X=Pyrene-(Pyr-c) | 1.7E+16 | ||||||

| 5i | X=Benzo-thiadiazole-(Pyr-c) | 4.3E+16 | ||||||

| 5j | X=Benzo-thiadiazole-(Pyr-c) | 4.9E+17 | ||||||

| 5k | X=Bis(ethylhexyl)-dioxo biindolinylidene]-(Pyr-c) | 5.6E+18 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 78] | Ru | Ru(Bis[p-methoxystyryl]- bpy)3[PF6]2 |

HeLa | Cervical | +++++ | 500 | 3.0E+18 |

|

| Ru1 | Pluronic/Poloxamer2.5:97.5 | 9.0E+19 | ||||||

| Ru2 | Pluronic/Poloxamer 5:95 | 1.0E+20 | ||||||

| Ru3 | Pluronic/Poloxamer 7.5:92.5 | 1.1E+20 | ||||||

| Ru4 | Pluronic/Poloxamer 10:90 | 2.5E+20 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [25, 52, 62] | 1 | [Ru(tpy)(pydppn)]2+ | MDA-MB-231 | Mammary | ++++ | 460–470 | 0.0E+00 |

|

| 8 | [Ru(tpy)(Ph2Me2dppn)(py)](PF6)2 | 3.0E+19 | ||||||

| 9 | [Ru(tpy)(Me2(Me2Ph2)dppn)(py)](PF6)2 | 3.8E+19 | ||||||

| 10 | [Ru(tpy)(Me2((MeO)2Ph2)dppn)(py)](PF6)2 | 6.5E+19 | ||||||

| 8 | [Ru(tpy)(Ph2Me2dppn)(py)](PF6)2 | DU-145 | Prostate | ++++ | 460–470 | 1.5E+19 | ||

| 9 | [Ru(tpy)(Me2(Me2Ph2)dppn)(py)](PF6)2 | 2.6E+19 | ||||||

| 10 | [Ru(tpy)(Me2((MeO)2Ph2)dppn)(py)](PF6)2 | 2.2E+19 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [15, 44] | TLD1433 | [Ru(dmb)2(IP-TT)]2+ | A549 | Lung | ++++ | 532 | 1.6E+16 | See Table 1 |

|

| ||||||||

| [36, 72] | TLD1433 | [Ru(dmb)2(IP-TT)]2+ | CT26 CT26.CL25 U87 F98 CT26 U87 F98 |

Colorectal Colorectal Glial Glial Colorectal Colorectal Glial |

?? ?? +++++ ?? ?? +++++ ?? |

525 | 9.9E+15 5.2E+15 2.4E+16 1.3E+17 2.7E+17 1.7E+17 2.6E+17 |

|

| TLD1411 | ||||||||

| [Ru(byp)2(IP-TT)]2+ | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [3] | TLD1433 | [Ru(dmb)2(IP-TT)]2+ | T24 | Bladder | ?? | 530 | 1.5E+15 | see Table 1 |

| AY27 | Bladder | ?? | 7.7E+14 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| [21] | TLD1433 | [Ru(dmb)2(IP-TT)]2+ | AY27 | Bladder | ?? | 625 | 3.4E+17 | see Table 1 |

| TLD1433+ 5uM Tf | 2.2E+17 | |||||||

| TLD1433+10uMTf | 2.1E+17 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [35] | TLD1433 | [Ru(dmb)2(IP-TT)]2+ | RG-2 | Glial | 530 | 2.4E+16 | See Table 1 | |

|

| ||||||||

| [44, 79] | 2 | Ru(bpy)2(mtmp)]2+ | A549 | Lung | ++++ | 455 | 2.0E+19 |

|

| 3 | Ru(Ph2phen)2(mtmp)]2+ | 2.3E+17 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| [27, 47, 80] | Ru65 | [Ru(bpy)2-dppz-7-methoxy][PF6]2 | HeLa U2OS CAL33 RPE-1 hTERT |

Cervical Osteosarcoma Tongue Eye |

+++++ ++++ ?? ++ |

350 350 350 350 |

1.8E+18 2.8E+18 1.6E+18 3.2E+18 |

|

|

| ||||||||

| [40] | ML19B01 | [Ru(tpbn)(dppn)(4-pp)]Cl2 | B16F10 | melanoma | ?? | 630 730 |

2.1E+18 1.5E+18 |

|

| ML19B02 | [Ru(tpbn)(dppn)(4-dmap)]Cl2 | 630 730 |

6.4E+18 3.2E+18 |

|||||

Threshold values in red indicate that the LD50 was not reached; hence, the numerical values represent only the minimum.

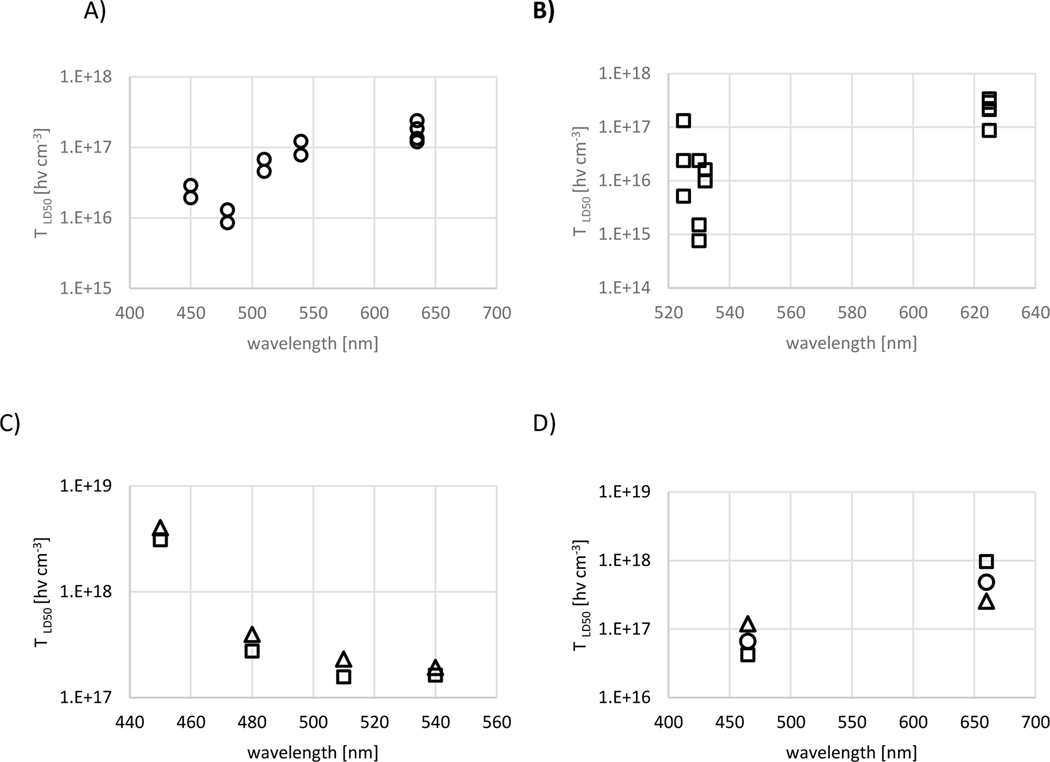

Figures 1A and B show the wavelength dependence for PpIX and TLD1433 mediated PDT, respectively, demonstrating a wavelength dependence of the after correction for ε(λ) and the photon's quantum energy. For TLD1433 mediated PDT, the wavelength-dependent gradient is positive and larger than for PpIX mediated PDT, at 2.1±0.4 1015 [hν cm−3 nm−1] and 8.3±1.3 1014 [hν cm−3 nm−1], respectively. The two R2 values for linear regression analysis are 0.71 and 0.78. A positive wavelength-dependent gradient indicates a reduced ΦΔ for photons with lower quantum energy. Conversely, a negative slope indicates an increased ΦΔ for lower photon energies. A positive gradient is common for first- and second-generation photosensitizers.

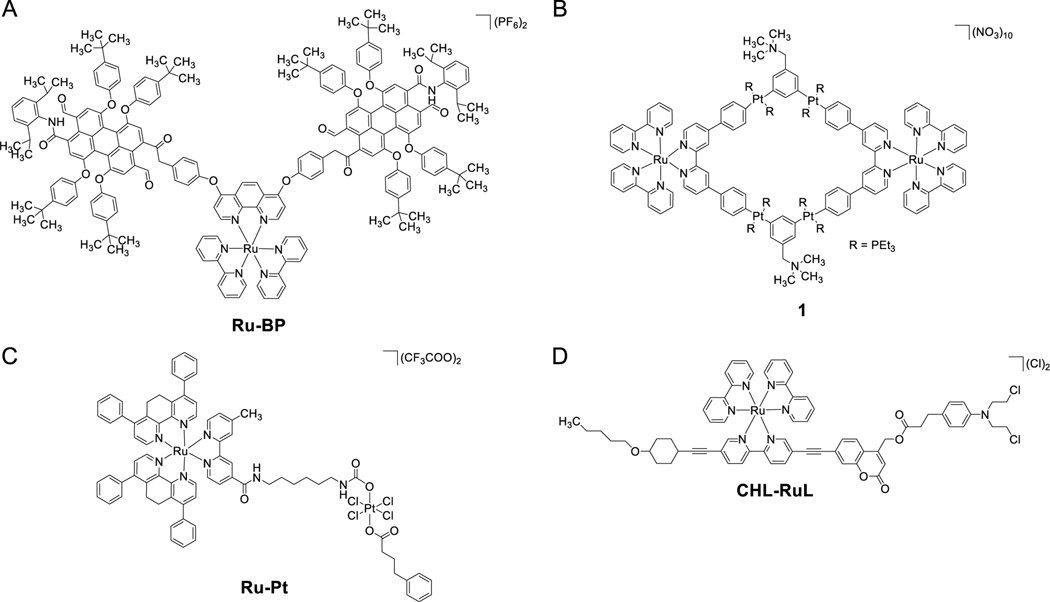

Figure 1.

Schematic of Ru-coordination coordinates according to A) [55] for Ru-BP, B) [58] for 1, C) [66] for Ru-Pt and C) [67] for CHL-RuL.

The wavelength dependence is available only for some Ru PSs. The Ru(II) polypyridine compound 4 by J. Karges et al. [38] in HeLa and RPE-1 cells, shown in Figure 2C, presented a negative gradient with decreasing for increasing wavelength from 450 to 540 nm. A negative gradient going from 630 to 730 nm is also seen for the two dppn-based complexes reported by Konda et al. [40]. While a 50% drop in the is not statistically significant, it echos the better quantum efficacy for longer excitation wavelength in some of these compounds. J. Zhoa et al. [41] evaluated 485 nm and 660 nm for PDT activation of three Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes in LnCaP cells (1–3), with either bipyridine, phenanthroline, or biquinoline ligands, all showing wavelength dependent gradients comparable to TLD1433 despite significant differences in photobleaching rates for complexes 2 and 3 relative to TLD1433.

Figure 2.

Wavelength dependent for (A) ALA-induced PpIX mediated PDT, (B) TLD1433 mediated PDT and (C) Ru(II) polypyridine compound 4 by J. Karges et al. [38]. All experiments were performed in HeLa cells (squares) and RPE-1 cells (triangles) (D) for Ru(II) complexes containing 2,2′-bipyridine, 1,10-phenanthroline, or 2,2′-biquinoline ligands reported by J Zhao et al. [41] were squares, circles, and triangles indicate the three complexes, respectively. Data for A, B, and C were executed in HeLa and RPE-1 cells. Experiments in D are shown for HeLa cells.

Negri et al. [46] and Zhang [77] quantified the LD50 of their Ru PSs for at least two radiant exposures. In the work of Negri et al., a six-fold increase in the radiant exposure increases the for the [Ru(Pc)] four-fold, whereby for trans-[Ru(NO)(NO2)(Pc), the increase was limited to 40%. These differences were attributed to reduced photobleaching for the latter compound. The data for the ppy complexes reported by Zhang et al. [41,77] are more difficult to compare as radiant exposure and wavelength were inconsistent. However, a doubling of the photon density [hν cm−2] increased the between 1.5- and 4-fold depending on the cell line, with the smallest increase observed with MRC-5 cells and the largest increase with HEP6 cells.

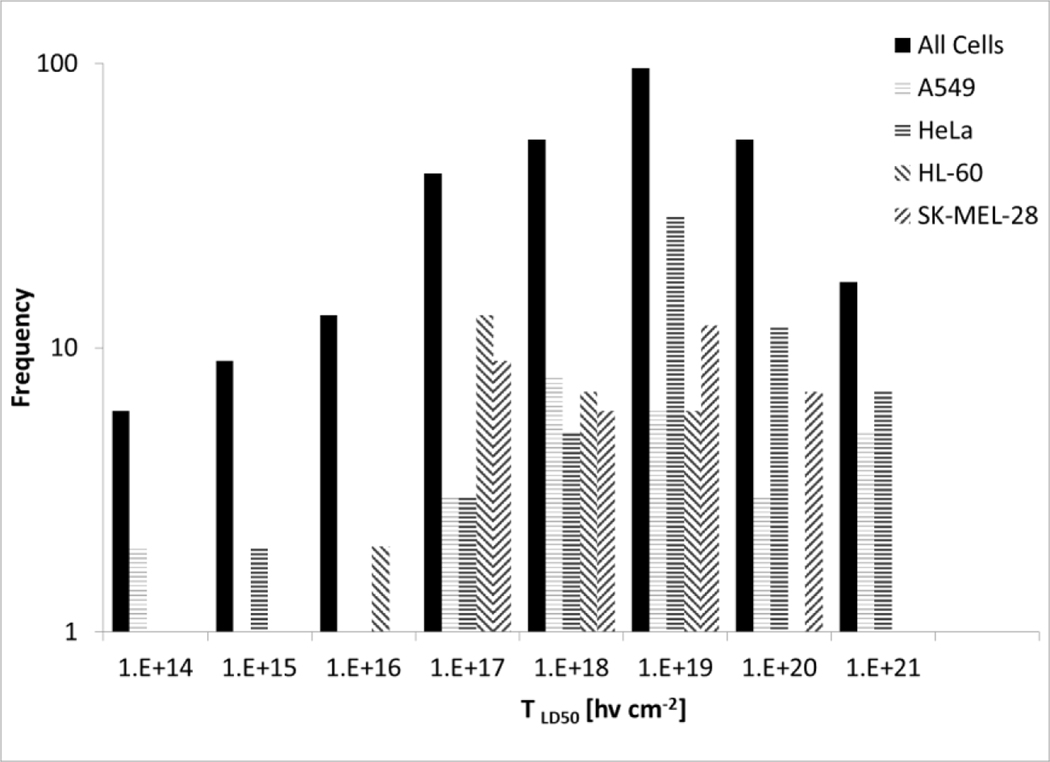

Because the vast majority of the studies utilized epithelial cell lines, a reasonable choice given that these are the cells that can transform into a malignancy, the effects of cell morphology on the are not clear. Only a few studies used fibroblast and lymphoblast cell lines. The data presented in Table 2 indicate little difference in the for epithelial or fibroblast cell lines with the same Ru PS. Figure 3 shows the frequency histogram for values derived for all cell lines compared to the most frequently used cell lines (A549, HeLa, HL-60, and SK-MEL-28 cells). While the distributions are somewhat broad, and the distribution is skewed toward higher values for HL-60 cells and lower values for HeLa cells. Cell line origins in terms of sex and organ do not affect the frequency histogram distribution or alter the median at p > 0.25.

Figure 3.

Frequency histogram (Log scale) of calculated values for all cells compared to A549, HeLa, HL-60, and SK-MEL-28 cells. The data is derived from all Ru PS and treatment conditions listed in Table 2.

Of the 154 proposed PDT-active compounds, nine are Ru(II) compounds covalently bound to 1st or 2nd generation PSs that act as the principal PS. The calculated values cover the entire range from 1016 to 1020 [hν cm−3]. The values determined for the Ru PS-Foscan conjugate with HeLa, A549, Me300, and A2780 cells ranged from ~8×1019 to ~3×1020 [hν cm−3] [43], which compared unfavorably to Foscan alone with a reported of 3.4×1018 [hν cm−3] in 14C cells [29], 5.9×1017 in HeLa cells, 1.2×1018 [hν cm−3] in A431 cells,[81] and 2.6×1014 [hν cm−3] in LLC1 cells [82].

NPs or nanocarriers yielded values from 1018 to 1020 [hν cm−3]. The values are larger than those for ALA-induced PpIX listed in Table 1, and hence these constructs are less favorable for translation. Various modifications of the NPs or nanocarriers have been proposed. For example, Wang et al. [74] demonstrated a 40–50% reduction in the when [Ru(dpphen)2(py-SO3)]+ is modified by poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and associated with 1,3-phenylenebis(pyren-1-ylmethanone) as an absorber. In work by Karges et al. [78] encapsulating a lipophilic polypyridine containing Ru PS with Pluronic F-127, the efficacy of the resulting NPs decreased monotonously with increasing particle diameter, raising the from 3×1018 [hν cm−3] for the parent compound to 9×1019 [hν cm−3] for the smallest to 2.5×1020 [hν cm−3] for the largest NP. The reason for these higher values for the formulated counterparts are unclear but could result from failure to localize at the most sensitive cellular compartments or high absorption of the cytotoxic radicals by the NP or nanocarrier structures themselves. Only the study by Soliman et al. [83] allowed determining the as a function of DLI for 4 NPs and the Ru PS parent compound. The calculated values for all NPs were lower than the parent compound at 4 hrs DLI, so a 48 hrs DLI reduced the for the 4 NPs to less than the parent compound, with factors between 1.5 to 4.9 versus > 5.1, respectively.

The calculated TLD50 of the small number of bi or multi-metal compounds varied wide from the high end of ~10 20 [hν cm−3] for the seahorse type di ruthenium tetracarbonyl porphyrin systems by Johnpeter et al. [43] to the heterometallic Ru–Pt metallacycle proposed by Zhou et al. [58] resulting midrange TLD50 10 18 [hν cm−3] and the Ru-Pt complex presented by Karges et al. [66] exploiting the chemotherapeutic cytotoxicity of Pt compounds targeting the nucleus and the Golgi resulted in the lowest 10% of calculated TLD50. The very low TLD50 values seen for the Ru-Pt complexes combining PDT with classical chemotherapy are comparable to approaches combining 1st and 2nd generation PSs with standard chemotherapy, reviewed by Lou et al. [84]. Here, the chemo and PDT compounds are delivered simultaneously, as nanocarrier [58] but opposed to a sequential delivery [62], resulting in similarly high efficacy and, hence, low TLD50 values.

The situation is different for Ru compounds appended to phthalocyanine reported by Negri et al. in the treatment of A375 cells, resulting in a range of ~0.6 to 2.4 1017 [hν cm−3] compared to desulphonated Chloro-aluminum phthalocyanine PDT in G361 human melanoma cells having a range of 2.1 to 8.2×1018 [hν cm−3] [85] and in MCF-7 cells up to 1.9×1019 [hν cm−3] [86].

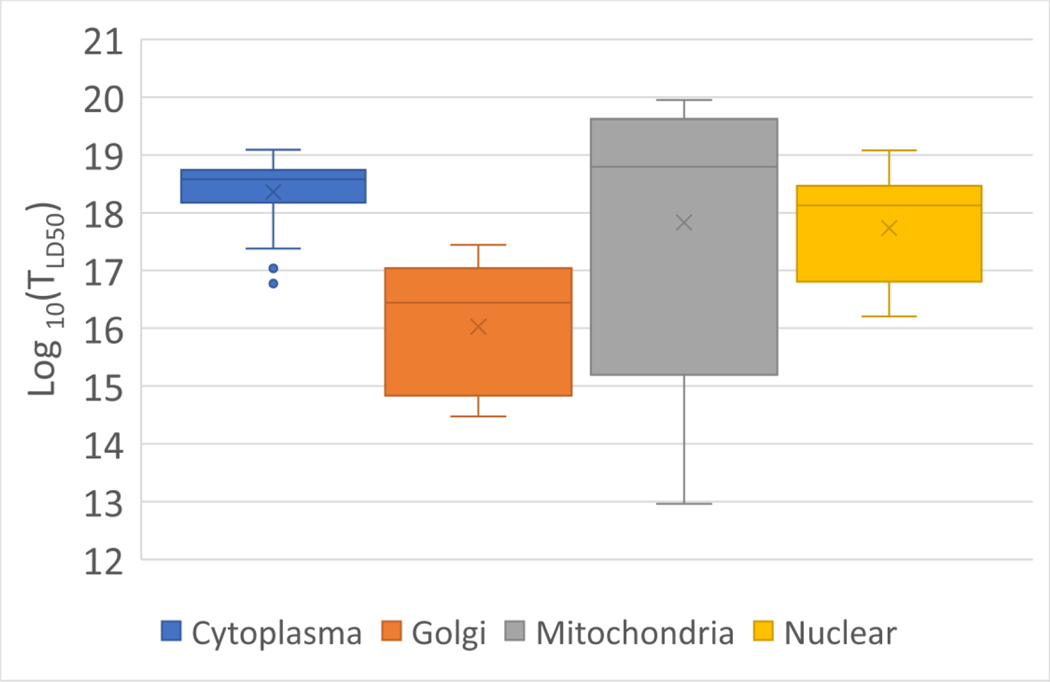

Most evaluated reports present results pertaining to subcellular localization prior to light exposure. The majority of the Ru compounds showed subcellular colocalization with mitochondrial biomarkers and trackers or peri-nuclear fluorescence signatures (Figure 4). Mitochondrial co-localization was demonstrated for N=15 compounds in n=38 experimental conditions, resulting in values of 2.1×1019 ± 2.7×1019 [hν cm−3]. Those demonstrating or suggesting nuclear localization represent N=21 compounds under n=30 experimental conditions and values of 2.3×1018 ± 3.2×1019 [hν cm−3]. While DNA localization provides a high-value target and should translate to a low LD50 photodynamic threshold dose, it is reflected in the calculated threshold values according to Table 1. While DNA cleavage or damage visualized by Comet assay [87] or γH2AX repair foci [88] have been reported [89,90], only a small number of studies suggest co-localization studies placing the Ru PS in the nucleus. If DNA fragmentation was reported, it was delayed, possibly as part of an apoptotic cell death pathway [49]. Co-localization is reported with biomarkers for the mitochondrial [91], cytoplasmic organelles, perinuclear zone, or other high-value targets for the PDT-generated cytotoxins. The work by Paul et al. [61] demonstrated that some [RuCl(LL′)(LL′′)]Cl compounds containing (OCH2CH2)3OCH3 and BOPIDY moieties localize in the mitochondria and result in values as low as 1013 [hν cm−3]. The authors attributed the high efficacy to the ability of the compound to cleave nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. The N=10 Ru PSs for n=30 conditions showing diffuse localization throughout the cytoplasm resulted in values in the 3.9×1018 ± 3.0×1019 [hν cm−3] range.

Figure 4:

Box and whisker plots of the Log 10(TLD50) from Ru PS with subcellular co-localization information for cytoplasm, Golgi, Mitochondria, and nuclear accumulation. The x represents the median value and the whiskers 2 standard deviations, indicating a non-gaussian distribution.

This reflects a tendency to invoke multiple mechanisms. One approach target known survival receptors enriched in tumors, as in work by Zhao et al. in prostate cancer [41]. Here the delivery of cytotoxic Ru(II) and androgen receptor inhibiting bicalutamide by blue light dissociation of the cage chemotherapeutic. In the approach by Negri et al. [46], the PDT photoactivation was combined with 850 nm light to initiate photobiomodulation [92] shown to have potential in cancerous cell lines[93] Both approaches resulted in TLD50 < 5* 10 17 [hν cm−3] equivalent to the lower third calculated values.

Quantum efficacy can be increased by various means, including replacing C–H bonds with heavier C–F bonds to diminish vibrational quenching of the excited 3MLCT state and prolonging its lifetime, thus increasing the probability of energy transfer to ground state 3O2, assuming that equally reactive ROS are generated. However, the efficacy of this approach attempted for TLD1433 showed no noticeable improvements. It was demonstrated that ILCT states based on oligothiophenes show higher reactivity than IL states based on dppn, even for almost identical ε(λ) and for ΦΔ. The ligands’ length can increase the number of inter-ligand transfer states but increasing lengths will ultimately limit the available quantum energy for 1O2 generation [61, 62, 94].

It was shown that the advantage of Ru(II) complexes to act as chemotherapeutic agents is often retrained when photoactivated ligand disassociation [95] is present, as demonstrated for Ru-Pt complexes, resulting in low overall survival [66]. Indeed, several Ru PS showed high efficacy while proving negligible 1O2 generation [63,69,70]. This plurality of cytotoxic mechanisms can be highly beneficial if they are all initiated by photon absorption. However, if chemotherapeutic effects given by DNA binding or ligand dissociation are independent, the overall phototherapeutic index for the compound drops due to increased dark toxicity [66].

A caveat of reporting subcellular localization at a particular time point post-Ru PS administration is that re-localization is possible, mainly post photoactivation. Hence, the registered association of the PS with specific structures has to be interpreted cautiously. In addition, various Ru PS can also rely on photoactivated uptake [96]. When uptake is facilitated in the absence of light, it has been reported to be accompanied by higher dark cytotoxicity [97].

Transferrin receptor (TfR), also known as CD71, is a cell surface receptor with two identical glycosylated subunits linked by disulfide bonds. Tf, a glycosylated protein responsible for the regulation and distribution of iron in the body, binds to TfR. Similar to iron, Ru compounds can bind Tf in a non-competitive form. Tf-bound cargo will be internalized into the cells expressing TfR by endocytosis [98] but can lead to retention of the Ru PS in the endosomes. TfR expression is strongly correlated with an increased cellular proliferation requirement associated with some cell types and most cancers. Various Ru PSs have been shown to exploit receptor-mediated uptake by cancer cells for drug delivery. Here we probed whether TfR expression in the cell lines used for in-vitro PDT efficacy studies correlated with the calculated values. By comparing the available data, no correlation was observed in studies using the same PS on cell lines expressing different TfR levels. Data from Cloonan et al.[49] included in Table 2 lists the in vitro efficacy for five Ru PSs in cell lines (HeLa, A549, and A2780) that are classified into +++++, ++++ and + TfR expression, respectively. We found that the values are not significantly different. The TfR expression in these three cell lines did not show the anticipated inverse relationship with the calculated values for their tetracarbonyl compounds. Similarly, Table 2 entries [25, 54, 56, 58, 65, 66, 67, 73, 74, 75] investigating more than one cell line, show no correlation between the values and TfR expression. Only two entries (6 and 8) in Table 2 showed an inverse correlation between the value and TfR expression. In work by Karges et al. [34,38], both Ru PSs tested show in the 1016 [hν cm−3] range for HeLa cells and 1017 [hν cm−3] for A549 cells. While the reduced for high TfR expressing HeLa (+++++) cells compared for the weaker TfR expressing RPE-1 (++) cells is consistent with TfR as cell uptake mechanism, the difference is negligible at a factor of 0.2 to 2.

DISCUSSION

This review focused entirely on the number of photons absorbed by the Ru PS per volume to cause cell death, whereby it is assumed that the total volume of the cells is minimal compared to the volume of the Ru PS loaded medium and an equilibrium exists within the cells and the media during incubation. We acknowledge that this is only one of the photophysical parameters deciding translational suitability toward the clinic. The tissue optical properties determine the probability of photons reaching the target tissue at a distance d from the photon emitter for a given excitation wavelength. However, for triplet states with equal quantum yields for the formation and photosensitizing capacities, the molar extinction coefficient of the Ru PS at the excitation wavelength (relative to the absorbance by other competing chromophores) sets a fundamental limit for the overall efficacy of a Ru PS and, hence, its potential for translation into the clinic.

General observations

One key PDT efficacy parameter is the singlet oxygen quantum yield, ΦΔ. The range reported for the compounds covers close to the physically possible range for various solvents and activation wavelengths. Classical 1st and 2nd generation PSs have ΦΔ typically higher than 0.5 such as Talaporfin sodium, a chlorin e6 derivative, at ΦΔ = 0.77 [99], PpIX between 0.56 [100] and 0.77 [101,102], Photofrin (0.89), benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring-A (0.84), zinc protoporphyrin IX at (0.91) [100] and mesotetra-(4-sulfonato-phenyl) porphine or Foscan (0.61). Aluminum tetra sulfonate phthalocyanines are exceptions, with ΦΔ as low as 0.38. [Ru (bpy)2(dpb)]2+ shows a long-wavelength 1MLCT maximum (551 nm), but a moderate singlet-oxygen quantum yield (ΦΔ) (0.22), whereas [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ shows a high ΦΔ singlet-oxygen quantum yield (0.79) but requires short-wavelength 1MLCT maximum (442 nm). Nevertheless, high ΦΔ for long-wavelength excitation is feasible as shown by Lifshits et al. [103,104] for dppn ligand due to its exceptionally low-energy 3IL state, estimated at 1.33 eV excitable with 733 nm photons. The singlet quantum yield cannot explain the 7 orders of magnitude seen in the calculated here.

As shown in Figure 2, the number of photons required to generate the cytotoxic load to achieve the LD50 increases at longer wavelengths for the Ru PSs and ALA-induced PpIX, except for complex 4 by J. Karges et al. [38]. Hence, the shorter, more energetic wavelengths are either more efficient at producing the lowest triplet state for ROS production or populate higher-lying states that result in other radicals and possibly alternate mechanisms. The larger values for the shorter excitation wavelengths for complex 4 in Figure 2C could point to much higher photobleaching rates with higher excitation energies. The publication reports theoretical transitions for the short-wavelength excitation, which were also experimentally tested, but none at the longer wavelengths potentially responsible for the increased efficacy.

Subcellular localization is often credited for PDT efficacy [105–107]. As indicated above, photochemically targeting the mitochondria [108] or the nucleus could provide a highly effective avenue for Ru PSs. However, demonstration of nuclear localization is not presented as often [80], and demonstration of direct Ru PS mediated PDT induced DNA cleavage in vitro by comet assays [91,109,110] or γH2AX DNA repair foci [80,89,111] is also less frequent. In particular, DNA cleavage at short time intervals following light activation to demonstrate direct PDT activation of Ru PS at the DNA is extremely rare. In vivo DNA cleavage data does not appear to be currently available. As the lifetime of the ROS is in the 10s or nsec resulting in diffusion distances of ~ 100 nm, targeting sensitive cellular compartments or critical structures, such as the lipid rafts on the plasma membrane reduced the number of ROS generated per cell to cause their destruction.

The analyzed compounds comprises both hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds, whereas the latter can internalize into cells easier than the former thus generating the cytotoxic dose in proximity to critical structures. It should be noted that the Threshold values intrinsically considers internalization and subsequent localization. Localization imaging and reporting are generally provided pre-PDT exposure, and re-localization or redistribution of the PS during photoirradiation or by photochemical internalization are both possible [112,113]. While the number of compounds for which subcellular localization was reported is limited to 60, the majority, N=50, are said to colocalize with biomarkers for either the nucleus, the mitochondria, and the Golgi, or are shown to be diffuse throughout the cytoplasm, shown in Figure 4. Subcellular distribution of Ru(II) coordination complexes shows patterns from diffuse accumulation throughout the cytoplasm [110], or colocalization with trackers for the mitochondria [90,108,114–116], lysosomes[76,117–119], less specific perinuclear regions [21,76,119,120] or nucleus [49]. Some Ru PSs did not show preferential localization to one compartment. Instead, they spread in several cellular compartments simultaneously, as noted by Pierroz et al. [80] for [Ru(bpy)2-dppz-7-methoxy][PF6]2, which was partitioned in the mitochondria, nucleus, and throughout the cytoplasm. Only one of the reviewed manuscripts reported Mander’s M1 co-localization values of Ru PSs with endoplasmic reticulum reporter molecules. However, similar co-localization values were also shown for Golgi [66] and lysosomes reporter proteins [73]. In work by Negri et al. [46], redistribution following light irradiation to less sensitive cellular compartments could explain the reduced PDT efficacy as indicated by the increased for higher radiant exposure.

While higher for diffuse cytosolic localizing Ru PSs over those proving nuclear localization is anticipated, the median gain is only about an order of magnitude. More surprising, however, are the very low values for the four Ru PSs shown to co-localize with biomarkers for the Golgi [121], providing an exciting avenue for further studies. Considering the efficacy of 1st and 2nd generation PSs localizing at the inner mitochondrial membrane, the range of calculated values for mitochondrial co-localized Ru PSs, covering more than five orders of magnitude, is surprising [108]. This cannot be explained only by differences in ROS quantum yield, and one needs to consider localization at the outer, less critical mitochondrial membrane. An observation by Lameijer et al. [63] regarding the nuclear and mitochondrial localization of the DNA light-switch dppz compounds raises the possibility of targeting the mitochondria via the lipid oxidation of its inner membrane [122] as well as the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) [123] Unlike nuclear DNA, mtDNA lacks protective histones and is more susceptible to DNA damage from free radicals [123] similar to solution-based DNA plasmids. This approach could be interesting for the recently identified subclass of glioma fueled by hyperactive mitochondria [124], as their destruction should lead to the cessation of tumor growth. However, not all dppz compounds may be equally effective, and this dual targeting still needs to be also demonstrated in vivo. In general, the cell compartment targeting in one cell line can not automatically be transferred to other cell lines.

Lastly, imaging subcellular colocalization using confocal laser scanning microscopes will induce ROS, and changes in the localization can often be observed during prolonged imaging studies.

Possible limitations of the derived threshold values

The reported ε(λ) are in aqueous or organic solvents and do not necessarily represent the absorption probability in biological media, particularly cells and tissue. The microenvironment affects the ε(λ) of a PS at a given wavelength and shifts in the various electronic transitions have already been demonstrated (e.g., Temoporfin marketed under Foscan in Europe) [125]. The ε(λ) of TLD1433 was significantly modified when this Ru PS was dissolved in incomplete and complete media versus water and after mixing with apo-Tf to obtain Rutherrin [21]. These changes in ε(λ) amount to less than a factor of 5, and while purity is never 100%, its impact on the Ru PS's efficacy amount to only a few %. Hence, these a priori assumptions are not the driver in the extensive range of calculated here.

Limitations in reporting for a complete comparison of all studies

Currently, approved PSs are porphyrins, phthalocyanines, or chlorins [29,32,126], generally resulting in vascular and cellular PDT [126]. In particular, coordination complexes based on transition metals and, particularly Ru(II), continue to gain attention as they provide the ability to design systems whereby solubility, subcellular targeting, and photon absorption can be modulated independently [2,127,128]. However, almost 80% of the reviewed reports lack detailed information on the light parameters and absolute molar extinction coefficients. Without this information, the potential receptor industry cannot evaluate the potential clinical impact of these novel Ru PSs. Reports must provide the molar extinction coefficient ε(λ), or absorption spectra with the PS concentration, across the experimental wavelength range. Spectral information should be included in text, table, or graphical form in the main manuscript or the supplementary data.

Reporting details of the light source is often insufficient, particular when using broadband light sources such as LEDs, quartz lamps, or slide projectors. While LED sources are more common now than quartz or tungsten lamps, particular model numbers and bandwidth are seldom reported. Most problematic are white LEDs, as their emission spectrum between warm and bright or cool white differ significantly [129]. Hence, the wavelength-dependent absorption is difficult to approximate. Spectroscopic quantification of the source's emission in mW nm−1 is required, whereby the spectrophotometer wavelength-dependent responsivity must be considered. Most spectrophotometers are corrected for the wavelength-dependent responsivity, but it is always recommended to use a quartz halogen lamp with known filament temperature acting as black body emitter to validate the accurate response correcting.

Another important detail missing is the power meter used (Model, Manufacturer, and most recent NIST or DIN traceable calibration). The American Association of Medical Physicists Task group 140 report should be consulted [130]. This is of greater importance for broadband light sources due to the wavelength dependence of certain power meter styles, particularly those based on the photoelectric effect. The availability of inexpensive lasers and LEDs with narrow bandwidths is reducing the frequency of broadband light usage, allowing better quantification of the .

Photostability or its inverse (photobleaching rates) should be reported at the PDT activation wavelengths. From the point of translation, only permanent photobleaching caused by low fluence rates (<200 mW cm−2) needs to be reported, given this generally accepted maximum irradiance to avoid hyperthermia clinically. The photobleaching rates are typically quantified via the emission intensity , as the sum of multiple exponentials depending on time [131], so a loss in absorption can also be used if the RuPS is non-emissive.

| (Eq 6) |

with kn representing the bleaching rates [s−1] due to loss of an electronic transition, n, with An representing the Absorbance contribution of transition, n, to the Ru PS absorption and generation of ROS. However, from a translational aspect, it could be more advantageous to provide the photobleaching rates as a function of the radiant exposure, H. Hence Eq 5 becomes

| (Eq 7) |

and with kn taking on units of [cm2 mJ s−1]. If the PSs are formulated, the effects of photobleaching should be considered. The impact of liposomes, micelles, and PLGA nanocarriers on the photobleaching rates of porphyrins has been well documented [132]; however, less is reported for the Ru PSs. For Ru PSs with low photobleaching rates, particularly for the transitions excited by the PDT treatment wavelength, high PS concentrations can be replaced with low-cost photons, thus increasing the PI. Hence, small PIs reported for some of the compounds should not be limiting translation if the required photon density can be delivered in clinically acceptable time intervals.

Effect of transferrin as a transporter

Formulation with Tf improved TLD1433 accumulation in brain and glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) tumors in vivo [21]. Premixing of Ru(II) coordination complexes with Tf had only a small effect on the as seen in Table 1B [21], which is similar to reports for mTHPC [133]. However, this does not reflect the potential benefits in vivo when transport across biological barriers and across cells is considered. The benefit of Tf- or ferritin-associated drug distributions is well established [134–136].

Though the majority of the studies do not suggest a correlation between the threshold values with TfR expression, two studies show the expected inverse correlation between the TfR expression and value. Additionally, data related to entry [21] Table 2 shows that the addition of an increasing quantity of exogenous Tf to the assay medium resulted in a trend towards reduced values. One anticipates more correlations with TfR expression and threshold values if other studies use exogenous Tf in their assay medium. This could facilitate receptor-mediated uptake of some Ru PSs, particularly for short DLIs. Based on the available literature on Ru PSs, binding to exogenous Tf will mediate active receptor-driven uptake in in-vivo models [98]. Furthermore, it is reasonable to anticipate additional benefits of Tf binding during in vivo studies due to the potentially prolonged circulation times and the ability to cross organ barriers in addition to the high TfR expression in proliferating malignant cells. The smaller reduction of values for TfR-mediated endocytosis when delivering the Ru PS as NPs results from the NP disrupting the binding between Tf and its receptor.

The anticipated correlations between the cellular TfR expression and lower threshold values for in vitro studies using exogenous Tf in their cell growth medium [98] could not be tested, given the long DLIs employed. This will augment the receptor-mediated uptake of Ru PS, particularly for short in vivo DLIs. Based on the available literature, binding to exogenous Tf by Ru PSs should mediate active receptor-driven uptake in in-vivo.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The ability to excite Ru PSs at longer wavelengths may be paramount for their clinical translation for specific applications that require tissue penetration. For the majority of tissues, shifting the PDT activation wavelength from the 450 nm to the 550 nm or 650 nm range reduces the scattering coefficient, μs’, on average by ~25% or 45%, respectively [137], and the oxy and de-oxyhemoglobin absorption coefficients, μa, by 32% or 99.5% and 49% or 92%, for the two hemoglobin proteins respectively [138]. Assuming a 5% blood content and equal hemoglobin contribution will increase the 1/e light penetration depth from ~<200 μm to ~300 μm and ~2–4 mm for 450 nm, 550 and 650 nm, respectively. Given clinical reality, an effective PDT treatment depth will be limited to roughly penetration depth. Hence, the increase in the at longer wavelength seen for some PSs, reducing the quantum efficacy towards cell kill needs to be weighed against the ability to treat larger target volumes.

Independent of the limited number of publications permitting to calculate the in vitro Photodynamic Threshold Values for their published Ru PSs or NPs, the available data points to potentially highly effective PDT agents. Their hidden potential is tremendous and ready to be uncovered in the next generation of PSs. This is given by their resistance to photobleaching, ease of tunability to modulate the light absorption and a combination of photon-activated chemotherapeutic strategies.

To better compare the PDT efficacy between the various Ru PSs and 1st and 2nd generation PSs the community should consider more standardized in vitro culture systems based on commonly available cell lines from the ATCC catalog, including growth conditions and seeding density.

Despite the plethora of reported Ru PS constructs for PDT, in vivo data remains limited, including the ability to initiate a PDT-mediated anticancer immune response. As Clark [4] noted, simple Ru PSs can inhibit T-cell proliferation and thus suppress an immune response, which is not desirable in oncology. T-cells' enrichment activity can be accomplished by combining PSs with checkpoint inhibitors and other therapies [139,140]. Immune responses and anticancer vaccination have been demonstrated for classical 1st and 2ndgeneration of PSs [141] and reported only for three Ru PSs [142,143]. Similar to the concept of immunization boosters, repeat or continuous treatment is actively evaluated in the PDT community. The former is already completed clinically, as needed [144,145] and the latter is in the form of metronomic PDT or mPDT [146–149]. While both approaches are implementable in pre-clinical studies, pharmacokinetics and toxicology for repeat administration of the Ru PS needs to be completed. One opportunity for accelerated entry into in vivo work involves the Chicken Egg Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) model [150]. Only small amounts of PS are required in this model, and many cell lines can be tested. Another major advantage is the direct visualization of the tumor models to image PS accumulation and tissue response [151].

CONCLUSION

While the synthesis and structural characterization steps are paramount to introducing new PSs for PDT, detailed photophysical and PDT irradiation information can aid other researchers in reproducing the results and allow for efficacy comparisons. Manuscripts or the supplementary information should provide the molar extinction coefficient at the PDT excitation wavelength, the irradiance and irradiation time, or the radiant exposure, including the method used to measure power or energy density. The light source characteristics such as wavelength and emission bandwidth and the DLI should be provided and detailed information on the power meter used.

While activation of TLD1433 with green light is advantageous in the bladder providing a thin target depth, Ru(II) coordination complexes for indications in solid tumors may not develop their full potential until the excitation wavelengths can be shifted into the 630 to 800 nm range with high extinction coefficients to compete with photon background absorption in target tissue.

The development of Ru PSs with a high Goeppert-Mayer cross-section could be advantageous for surface proximal PDT indications, as in the eye [152], and basal cell carcinoma or similar skin lesions [188,189], albeit their utility will be limited for solid tumors which do not provide direct access to a scanning femtosecond laser beam.

This review focused only on converting photon energy to cytotoxic activity. The ability to translate Ru PSs into clinical use in oncology and antimicrobial applications also depends on other photophysical and pharmacokinetic factors. Clinical translation of compounds presenting with low TLD50 values and having shown low dark toxicity and some efficacy in small animal pre-clinical studies should be brought to the pharmaceutical industry's attention. Subsequent steps will require the production of larger quantities of the Ru PSs compounds for toxicology and pharmacokinetic studies in larger animals and the first-in-human studies. Identifying partners for this translation might be key, albeit there are resources available such as the International Photodynamic Association or the translational and therapeutic working group of the Optical Society of America.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

Dr. Lilge acknowledges financial support from the Ontario Ministry of economic development and trade through the Ontario Research Fund 2008-023. Dr. McFarland thanks the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Award R01CA222227) for support. The content in this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- 1O2

Singlet Oxygen

- ALA

5-Aminolevulinic Acid

- DLI

Drug Light Interval

- ED50

Half of the maximum attainable PDT mediated cell kill

- ILCT

Intraligand charge transfer

- LD50

PDT dose to achieve 50% cell kill

- LMCT

Ligand-to-metal charge transfer

- MC

Metal centered

- MLCT

Metal-to-ligand charge transfer

- MMCT

Metal-to-metal charge transfer

- NP

nanoparticle

- Pc

Phthalocyanine

- PI

phototherapeutic index

- PpIX

Protoporphyrin IX

- PS

Photosensitizer

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- Ru(II)PS

Ruthenium(II) containing photosensitizer

- ID

Identification number identifying data rows in Table 2.

- Tf

Transferrin

- TfR

Transferrin receptor

- 4-dmap

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- 4-pp

4-phenylpyridine

- azpy

(2-(phenylazo)pyridine)

- biq

2,2′-biquinoline

- BODIPY

4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene (boron-dipyrromethene)

- BP

1,3-phenylenebis(pyren-1-ylmethanone)

- bpy

2,2′-bipyridine

- BTF

benzothiazolylfluorenyl substituted phenanthroline ligand

- dmb

4,4′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine

- dpphen

4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline

- dppn

benzo[i]dipyrido- [3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine

- dppz

dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine

- dpq

dipyrido-[3,2-d:2′,3′-f]-quinoxaline

- IP-TT

2-(2′,2′′:5′′,2′′′-terthiophene)-imidazo[4,5-f][1,10]phenanthroline

- nT

thiophene (n=1), bithiophene (n=2) and terthiophene (n=3)

- pdppz

[2,3-h]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- phen

1,10-phenanthroline

- pmip

(2-(4-methylphenyl)-1H-imidazo[4,5-f][1,10]phenanthroline)

- ppy

2-phenylpyridine)

- py

pyridine

- pymi

((E)-N-phenyl-1-(pyridin-2-yl)methanimine)

- Pyr-c

diylbis(ethene-diyl))bis(pyrrole-carbaldehyde)

- py-SO3

pyridine-2-sulfonate

- TAP

1,4,5,8-tetraazaphenanthrene

- tatp

1,4,8,9-tetraazatriphenylene

- tpphz

tetrapyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c:3′ ′,2′ ′-h:2′ ′′-3′ ″-j]phenazine

- tpy

2,2′;6′,2″-terpyridine

Photons absorbed to kill 50% of cells [hν cm−3]

- c

Light speed in vacuum 2.998 108 [m sec−1]

- H

Radiant exposure [J cm−2] or [hν cm−2]

- h

Planck’s constant 6.626 10−34 [m2 kg s−1] or [J s]

- ε

micromolar extinction coefficient [μM−1 cm−1]

- ΦΔ

singlet-oxygen quantum yield

References:

- [1].Monro S, Colón KL, Yin H, Roque J, Konda P, Gujar S, Thummel RP, Lilge L, Cameron CG, McFarland SA, Transition Metal Complexes and Photodynamic Therapy from a Tumor-Centered Approach: Challenges, Opportunities, and Highlights from the Development of TLD1433, Chemical Reviews. 119 (2019) 797–828. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McFarland SA, Mandel A, Dumoulin-White R, Gasser G, Metal-based photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy: the future of multimodal oncology? Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 56 (2020). 10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lilge L, Roufaiel M, Lazic S, Kaspler P, Munegowda MA, Nitz M, Bassan J, Mandel A, Evaluation of a Ruthenium coordination complex as photosensitizer for PDT of bladder cancer: Cellular response, tissue selectivity and in vivo response, Translational Biophotonics. 2 (2020). 10.1002/tbio.201900032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Clarke MJ, Ruthenium metallopharmaceuticals, Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 236 (2003) 209–233. 10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00312-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cassells I, Stringer T, Hutton AT, Prince S, Smith GS, Impact of various lipophilic substituents on ruthenium(II), rhodium(III) and iridium(III) salicylaldimine-based complexes: synthesis, in vitro cytotoxicity studies and DNA interactions, JBIC Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 23 (2018). 10.1007/s00775-018-1567-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chen W, Luo G, Zhang X, Recent Advances in Subcellular Targeted Cancer Therapy Based on Functional Materials, Advanced Materials. 31 (2019). 10.1002/adma.201802725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gasser G, Ott I, Metzler-Nolte N, Organometallic Anticancer Compounds, Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 54 (2011). 10.1021/jm100020w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Antonarakis ES, Emadi A, Ruthenium-based chemotherapeutics: are they ready for prime time?, Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 66 (2010). 10.1007/s00280-010-1293-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kostova I, Ruthenium Complexes as Anticancer Agents, Current Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (2006). 10.2174/092986706776360941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alessio E, Thirty Years of the Drug Candidate NAMI‐A and the Myths in the Field of Ruthenium Anticancer Compounds: A Personal Perspective, European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2017 (2017) 1549–1560. 10.1002/ejic.201600986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Alessio E, Messori L, NAMI-A and KP1019/1339, Two Iconic Ruthenium Anticancer Drug Candidates Face-to-Face: A Case Story in Medicinal Inorganic Chemistry, Molecules. 24 (2019) 1995. 10.3390/molecules24101995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Trondl R, Heffeter P, Kowol CR, Jakupec MA, Berger W, Keppler BK, NKP-1339, the first ruthenium-based anticancer drug on the edge to clinical application, Chem. Sci. 5 (2014) 2925–2932. 10.1039/C3SC53243G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lilge L, Wu J, Xu Y, Manalac A, Molehuis D, Schwiegelshohn F, Vesselov L, Embree W, Nesbit M, Betz V, Mandel A, Jewett MAS, Kulkarni GS, Minimal required PDT light dosimetry for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer, Journal of Biomedical Optics. 25 (2020). 10.1117/1.JBO.25.6.068001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]